ABSTRACT

Although the varied benefits of purpose are increasingly recognized, there is more to learn about the how and why of purpose in later life. Forty older adults (aged 68–96 years) living within the South Australian community participated in a face-to-face interview to further existing understanding of purpose in older age. Conversations with older adults suggest that the majority continues to value and pursue purpose in their lives. Amongst older adults interviewed there was no single perception, definition or experience of purpose. However, through thematic analysis four categories of purpose emerged. Purpose was fulfilled through a drive for life; roles and responsibilities; routine, activity and independence; and faith and spirituality. The outcomes of this study build upon the limited body of evidence defining “purpose” from the perspective of older adults themselves which may in turn help inform future conceptualizations and measurements of purpose, as well as enable the design of interventions intended to promote, sustain or re-introduce purpose across the life span.

Introduction

Underpinned by the theoretical work of Victor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, purpose in life represents the extent to which adults maintain goals in life, a sense of directedness, feel there is meaning to present and past life, and possess aims and objectives for living (Ryff, Citation1989, Citation1995). Frankl argued that all individuals are capable of finding and maintaining purpose in their lives, even in the midst of seemingly meaningless situations and following negative events (Bronk, Citation2014).

Whilst subjective and overlapping, quality of life from the perspective of older adults may be represented by good health, autonomy and independence, meaningful roles and activity, high quality relationships, a positive attitude toward life, emotional comfort, spirituality, and environmental and financial security (van Leeuwen et al., Citation2019). Wellbeing in later life is also supported by conditions that enable older people to do what they value, to retain the ability to make decisions, and to preserve their purpose, identity and independence (WHO, Citation2020). Maintaining a consistent sense of purpose may support quality of life in later life: a time that can be associated with loss of social roles (such as employee or spouse) and change in physical or cognitive function (Pinquart, Citation2002).

Continued interest in purpose in life as a construct is underpinned by increasing evidence pointing to its potential to support, predict and promote better psychological and physical health in older age (E. S. Kim et al., Citation2013). Across the life span, higher levels of purpose may influence desirable mental, emotional and physical health outcomes (Pfund & Lewis, Citation2020) and support flourishing in life (Chen et al., Citation2022). A life with purpose may contribute to the ability to age “well” (Robertson, Citation2020) or age “successfully” (Knight & Ricciardelli, Citation2003; McCann Mortimer, Citation2010). As such many models of successful aging encompass purpose as a primary psychosocial domain (Reker, Citation2001; Troutman, Nies, & Bentley, Citation2010; Troutman, Nies, & Seo, Citation2010).

Greater purpose has been associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, incident death (Alimujiang et al., Citation2019; Boyle et al., Citation2009; Hill & Turiano, Citation2014; Zaslavsky et al., Citation2014) and increased survival probability (Windsor et al., Citation2015). Other studies have demonstrated similar associations between higher purpose and reduced risk for cardiovascular specific mortality (Alimujiang et al., Citation2019), myocardial infarction (E. S. Kim et al., Citation2013), cerebral infarcts (Yu et al., Citation2015), likelihood of stroke (E. S. Kim et al., Citation2013), prevalence of mobility disability and disease (Zaslavsky et al., Citation2014), and reduced health condition symptom severity (Haugan, Citation2014). Studies exploring the relationship of purpose with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) for older adults suggest greater purpose to be associated with a reduced risk of AD (Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, et al., Citation2010) and fewer proxy reported behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (Sutin et al., Citation2021).

Contemporary research has also suggested that a sense of purpose may contribute to cognitive reserve and abilities (Boyle et al., Citation2012; Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, et al., Citation2010; Lewis et al., Citation2017), slow down trajectories of cognitive decline over time (G. Kim et al., Citation2019) and influence higher scores for memory, executive functioning, perceptual speed and/or overall cognition (Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, et al., Citation2010; Lewis et al., Citation2017). Other dimensions of wellbeing associated with purpose include optimism, positive affect (Holahan & Suzuki, Citation2006; E. S. Kim et al., Citation2013; Pinquart, Citation2002), coping, personal growth, life satisfaction (Flood, Citation2007; Prairie et al., Citation2011; Sougleris & Ranzijn, Citation2011), emotional health, social connectedness (Chen et al., Citation2022), subjective wellbeing (Ardelt, Citation2003; Pfund et al., Citation2022; Yeung et al., Citation2019), self-esteem and psychological wellbeing (Bigler et al., Citation2001; Hedberg et al., Citation2010; Missler et al., Citation2011) and regulation of emotions in anxiety-inducing situations (Pfund et al., Citation2023). Greater purpose in life has also been correlated with health promoting behaviors amongst older adults such as exercise, physical recreation, relaxation, and regular checkups (Holahan & Suzuki, Citation2006).

The literature specific to purpose in later life continues to evolve. Although the benefits of purpose for a range of outcomes are increasingly recognized, there is more to learn about the “how and why” of purpose in later life (Pfund & Lewis, Citation2020). The objective of this study was to further contemporary understanding of how purpose is experienced by older adults. The baseline concept of purpose was informed by the three elements Bronk (Citation2014) considers essential components: commitment, goal directedness and personal meaningfulness (Bronk, Citation2014). In this context, purposeful activity is considered that which provides meaning to the older adult through pursuit of goals, completion of concrete tasks, realization of self-identity or roles, maintenance of independence, engagement with some aspect of the broader community, or participation in activity that aligns with past or present interests.

Materials and method

The present study was enacted through the qualitative methodology, phenomenography. Phenomenography is the empirical research approach intended to describe the different ways a group of people understand a particular phenomenon (Marton, Citation1988). Applying a phenomenographical approach, the researcher studies how people experience a given phenomenon rather than the phenomenon itself. Further to this the principles of phenomenography are sympathetic to the challenges of defining complex psychological constructs, such as purpose, through a quantitative approach alone. This methodology applies a second-order perspective in which the world is described as it is understood, meaning that phenomenon and person are not separate and independent of each other (Ornkek, Citation2008).

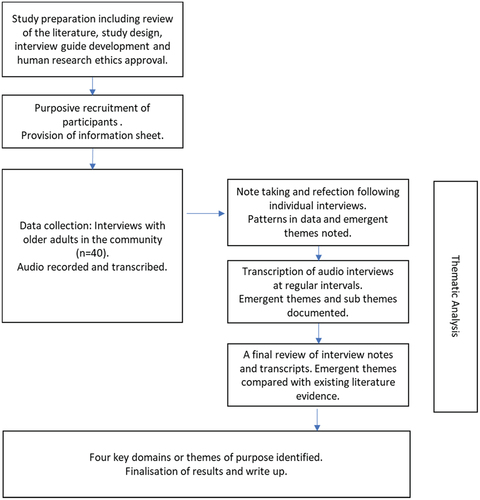

All interviews were conducted face-to-face by the author, a gerontologist and experienced qualitative researcher, and ranged from 25 to 90 minutes in length. Participants were provided with an information sheet outlining the purposes of the study at least one week prior to the interview. Written consent was obtained before interview commencement. A semi-structured interview guide underpinned the conduct of the interviews. The interview questions were informed by the relevant literature and Freund and Baltes’ (Citation2002) SOC Questionnaire: A self-report quantitative measure of selective optimization and compensatory behaviors (Freund & Baltes, Citation2002). Handwritten notes were captured during these conversations, and all interviews were audio recorded with permission. presents an overview of the research and analysis process.

To identify patterns in the data and inform the development of categories or domains of purpose, thematic analysis was undertaken across three phases of the project. Immediately following individual interviews, key themes or observations were noted by the researcher. At regular intervals during data collection, audio interviews were transcribed, considered in conjunction with accompanying handwritten notes, and emergent themes and sub-themes were documented (inductive analysis). At conclusion of the data collection stage, the researcher undertook an additional review of interview notes and transcripts and compared summary themes with that identified through the literature. Trustworthiness of findings was supported by purposive sampling, consistency in the interview process, prolonged interaction with the data, audit trail of potential codes/themes, transcription and organized storage of participant data, and consideration of interview findings against independent research. The study was granted ethics approval from the Flinders University Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee (Project Number: 8093).

Study participants and recruitment

Purposive sampling was applied. Forty older adults living within the community were recruited through community organization and council newsletters and notice boards and events (such as health classes and social lunches). Women formed 70% of the group and men 30%. Participants ranged in age from 68–96 years (M = 79.4, SD = 7.7). Over half of interviewees were married/in a relationship (23 adults or 57.5%), with the remainder widowed/divorced/separated or single (17 adults or 42.5%). A summary of participant characteristics is provided in Appendix A ().

Results

Amongst older adults interviewed there was no single understanding, definition or experience of purpose. Purpose was described as helping others, being with family and friends, a commitment to spiritual or religious practice and activities, or maintaining one’s independence and autonomy. Some considered purpose with respect to tangible activities of contribution such as employment, volunteering or care of grandchildren or through the lens of spirituality, such as purpose imbued by participation in church activities. For others purpose represented being “busy” or socially engaged with family, friends and the broader community.

There’s not enough days in the week. I get so concerned with some of my friends who phone and say “I’ve got nothing to do.” I can’t understand why there’s not some motivation at this stage in our lives. It’s all we’ve got left so why not make the most of your time? (P5, Female, 85)

The degree to which purpose was valued also differed between interviewees as did conscious thought about purpose more generally.

I’ve never really thought about it [purpose]. Life is there to be lived. It is a recognition of a desire to do things. It’s probably being critical of people who don’t do things … who just seem to veg … There’s no shortage of purpose in my life. (P39, Male, 69)

An onus on the individual to seek and maintain purpose in later life was expressed by interviewees. As was the need to create reasons to rise out of bed each day. In this sense there was a personal responsibility to ensure one’s life retained activity and meaning.

I think I’ve got a big life and I think I’ve got a lot of purpose … I’ve definitely got reasons to get up in the morning, they are not all reasons I would choose, but I’m motivated by I suppose a sense of responsibility for others, but also myself I guess. (P27, Female, 68)

You’ve got to make things to look forward to … To get out of bed you need something you’ve either got to do, or you look forward to or you create. Even if you have to create a reason for living, it is up to the individual. (P8, Female, 79)

Conversely, not all older adults felt a need for purpose as such. For this smaller group purpose was considered of importance for others, but less so for themselves.

I admire it [purpose] in others but I have sort of bowed out of thinking I need a sense of purpose. I don’t need a purpose very much anymore. I can sit back. I’ve retired. I have not retired from life exactly but I don’t feel I need to achieve anything more in my life except to stay upright and look after [husband]. (P29, Female, 83)

A sense of purpose was met through one or more dominant aspects of life, such as caregiving or faith, or a culmination of multiple drivers. Based on thematic analysis of interview findings, four categories of purpose were determined. These categories or domains are not necessarily disparate in that some adults reported the fulfillment of purpose across more than one. presents an overview of these domains, explored in detail in the subsequent text.

Table 1. Domains of Purpose and Illustrative Quote.

Drive for life

For some, purpose represented identity of self, personal values, and the embodiment of lifelong personality characteristics or behavioral traits. Some adults rose each day propelled by the sense they ought to. To remain in bed and not engage with daily life was to go against their longstanding attitude toward living.

I have always liked tasks having been a working person most of my life. That shapes you. I have always been a busy person. (P25, Female, 84)

Necessity gets you out of bed each day. You could just say oh well I’ll stay in bed today. but you don’t because nobody is going to get my breakfast, feed the cat. Nobody’s going to sweep up the leaves, do my washing and put out the rubbish bin. You’ve got to do these things. Often in the afternoons … unless I’ve got something to motivate me, you’re inclined to sit down and nap off. But if you’ve got something to do, you go do it. (P18, Female, 90)

A general love of life, curiosity and gratefulness for each day provided purpose for many.

There are things to do. You’ve got to get on with life. Just get up and get on. What gets me up every morning? Life. It’s interesting, it’s challenging, its new, anything can happen. Keeping on fostering that curiosity I suppose. (P5, Female, 85)

Others experienced purpose through pursuit of goals, stimulation and challenges.

Using my brain … to me that is important … I’m coming up to 70 in a year and there’s another 20 years perhaps. If I look after myself now then the really negative things that happen when you get old … perhaps I can defer those things … I can put those off. That’s important. (P39, Male, 69)

A small number of older adults were participating in formal education such as tertiary study. Others engaged in opportunities for learning and education such as courses or events offered by local council and community services or adult community education organizations. Many older adults continued to feel defined by their former professional or community roles and undertook activities influenced by their prior work and that which contributed to their ongoing sense of purpose.

Roles and responsibilities

Purpose was also imbued through roles and responsibilities. For some this was a role such as grandparent, parent, caregiver, committee member, employee or volunteer. Socializing with family and friends provided a source of purpose and fulfillment of a valued social role. Remaining healthy, active and in good mental health was important for older adults in order they be available for their family, and to minimize any sense of burden or worry experienced by those close to them. The desire to remain “useful” appeared quite profound for some adults.

I think of it [purpose] in terms of enjoyment … in terms of doing what you can. To make your life, not just your life but the life of others, happy. To be of use I guess. I think it is very important as we get older to still feel useful … to ask “what can I do?” (P23, Female, 78)

To get up in the morning … I’ve so many things I have to do. I have to do them. I have to care for a house, family. I have to take care of myself … I get up because I always have something to do … Sometimes absolutely no choice, you either do it or you give up. (P8, Female, 79)

Some older adults provided informal care to an adult child, spouse or parent on an ongoing basis. Caregiving in itself provided some adults with a sense of purpose and impeded the ability of others to take part in activity traditionally a source of purpose. Furthermore, changes in the health of their spouse had required adjustment in their traditional roles within the home. For example, assuming a greater share of housework or home or garden maintenance activities (such as mowing the lawn or pruning trees), formerly the responsibility of their spouse. For others, pets represented both a source of pleasure and companionship as well as an obligation for care that needed to be met each day.

A small number of older adults interviewed continued to work full time or part time, whilst others spoke of their involvement in local or broader organizations. Some provided free mentoring, justice of the peace services, drove community buses or vans, volunteered in local opportunity/thrift shops and libraries, facilitated library-based activities, cultural festivals, provided advocacy and information services and supported community lunches.

I’ve got to keep making sure that I feel worthwhile and that I’m not here on this earth not doing anything for anybody … I don’t ever lie in bed and think “what is life worth?” It just doesn’t happen … I’m not here to just fill up space. (P15, Female, 85)

Several older adults described a strong sense of civic duty and would undertake short term roles such as national census data collection and election staffing.

The motivation of my life is [party] politics and I’m still motivated by it now. Some people they haven’t got an interest that lasts all their life. They work and that is their main interest but when they give up work they can’t find anything else that is stimulating or that motivates them to keep going. (P18, Female, 90)

One interviewee continued to publish books and contribute to blogs specific to environmental and social activism.

Getting involved in environment activism … I go to rallies … do writing … That’s what drives me. I don’t want to leave the world in a bad place for my grandchildren. I worry about them. I worry about them all the time. What sort of world will they come into? That’s my driver. (P37, Male, 77)

Routine, activity, and independence

Although intensity and adherence varied between older adults interviewed, almost all described routine that guided daily activity. This could include the time they went to bed, arose in the morning or how they structured their day: individual behaviors based on lifelong patterns, habits, preferences and choice. Interestingly, whilst many suggested routine imbued a sense of meaning, stability and function to their day, the ability to disrupt this routine was important. For routine to be positive it must be within their ability to adjust or ignore at will. Maintaining control over what one did and when they did it provided a sense of both empowerment and comfort.

I like a routine because if I don’t do a routine I get a bit anxious … I have to do it to the best of my abilities. Get up- that is the first difficulty. Often I don’t want to get up … But I give myself permission not to bother with the shower at all some days because I like the variety. I like to feel I’ve got autonomy over it all. (P25, Female, 84)

Group activities, such as exercise classes, provided further motivation to participate based on a sense of commitment to their fellow group members.

I like group activities because there is a set structure and schedule … it is a reason to get out of bed. I like being part of a group because it motivates me to go. (P3, Female, 73)

Conversely, some older adults embraced the lack of rigid structure in their lives and experienced purpose through emancipation from former obligations or responsibility associated with work or family. Following years of regimented work and activities, they felt liberated by the ability to follow their own pace in life. There was a sense of this being “their time” and they were able to focus on their own happiness and prioritize what and who was important to them.

I’m at the stage of my life that I’m here to enjoy every day and by God I do. I can’t remember the last time I went to bed and thought I haven’t had a good day. That’s what I’m here for—to enjoy myself. I’ve done my bit. I’ve done my bit. (P38, Male, 83)

For others, maintaining independence, including health and wellbeing and an organized home environment, provided ongoing purpose.

My sense of purpose is keeping the house nice, keeping the garden nice, doing any repairs that need doing, helping anybody else … Generally, from day to day just keeping the machine going, keeping everything nice and neat. (P28, Male, 93)

Some adults considered themselves to be fiercely independent and were reluctant to seek help with any aspect of their lives. Others recognized the need to seek a degree of formal or informal support to maintain activities of daily living, home maintenance and assistance to attend events or activities outside of the home.

I don’t like to ask for help no. I made up my mind that if I have to ask my family to come and do for me then I’ll move out. I don’t want to, not that they wouldn’t do it, I don’t want to be an obligation. I don’t want them to worry about me. I can look after myself. (P19, Female, 88)

Faith and spirituality

A small group of interviewees described a keen sense of purpose imbued by faith and spirituality. This was particularly salient for those holding long-term affiliations with a religious denomination or congregation.

Probably my belief in God … That is my purpose, to learn to love God more. It’s not like a person without faith, a secular person, would see purpose. It’s not that. I have the joy and grace of not having to achieve anything in particular and God will still love me extraordinarily. That is the most freeing and wonderful thing. (P25, Female, 84)

For those who had held a professional or formal role within a religious organization, such as a minister or missionary, the drive to continue this work, albeit in a reduced role, was fundamental to their sense of purpose. Participation in faith-based activities also provided a source of social interaction and an opportunity to take part in activities they felt were valuable and contributed to the wellbeing of others.

Discussion

Research evidence continues to demonstrate a relationship between purpose and a range of physical, mental, social, economic and cognitive outcomes for older adults. Available evidence also suggests that purpose tends to decline with age (Boyle et al., Citation2009; Boyle, Buchman, & Bennett, Citation2010; Cohen-Louck & Aviad, Citation2020; Hill & Weston, Citation2019; Hill et al., Citation2015; Irving et al., Citation2017; Nakamura et al., Citation2022; Pinquart, Citation2002; Windsor et al., Citation2015). The aim of the present study was to better understand purpose from the perspective of older adults. The experience of purpose differed amongst older adults interviewed. Not all were able to define what purpose meant to them or how it was fulfilled in their day to day lives. Moreover, a small number of interviewees were quick to dismiss its relevance at their stage of life. However, across the group four themes specific to the fulfillment of purpose emerged. These included: a drive for life; roles and responsibilities; routine, activity and independence; and faith and spirituality.

A drive for life amongst community based older adults encompassed a love for life more generally and representation of lifelong personality or behavioral characteristics. Often describing themselves as “busy” people, this group spoke of current or former commitments and social roles contributing to their sense of purpose. The act of engaging with life each day through the pursuit of activities of daily living was a way of maintaining independence, mental health, wellbeing, and purpose. Others felt driven by the desire for challenge including education, work, travel, writing or volunteering. Former professional or community roles influenced the choice of activities with which some would engage and how they continued to define themselves and maintain their sense of purpose. Further to this, many adults continued to seek achievement of personal goals. Indeed, an “achievement motive” can positively impact purpose in later life, as can a sense of self-mastery often associated with such achievement (Sano & Kyougoku, Citation2016).

Amongst older adults living in the community purpose was also imbued through roles and responsibilities. Adults described activities that contributed to lives of other people and their involvement in local or broader organizations as volunteers or, to a lesser extent, as paid employees. For some, their purpose was an expression of civic duty or the wish to contribute to a “greater good” through advocacy, campaigning, or writing. Volunteer and charity activities can enhance quality of life, and provide meaningful opportunities for developing new social roles, thereby promoting a sense of reciprocation and purpose of life (Lee, Citation2023). Older adults may derive purpose by helping others through four processes: having something to do, maintaining relationships, owning a stake in the future and experiencing a sense of continuity. Connectedness to others through social or altruistic relationships provides a means to engage with life in meaningful, positive and purposeful ways (Register & Scharer, Citation2010). Studies have suggested that not only is personally valued and meaningful activity, such as volunteering or paid work, associated with greater purpose in life for older adults but in itself forms a component of such purpose (Eakman et al., Citation2010).

For some a sense of purpose is closely tied to major life roles. Older adults described the occupation of key social roles such as spouse, parent, grandparent, friend or carer: many of which have been associated with a range of positive health and wellbeing outcomes in later life (Heaven et al., Citation2013). Role identities provide purpose in life as well as a form of behavioral guidance (Thoits, Citation2003). The more important a role identity is to an individual the greater its continuation will contribute to a purposeful life (Thoits, Citation2012). If a sense of purpose is closely tied to major life roles, threats to continuation of these roles as a result of declining health, widowhood, changes in social structure, or retirement can indirectly impact such purpose and the type of goals an individual pursues (Lewis & Hill, Citation2020).

A small number of older adults interviewed continued to work full time, part time or through adhoc projects such as consulting, contract work or tutoring. Both paid work and/or volunteering have been associated with greater purpose in later life to varying degrees in the literature (Greenfield & Marks, Citation2004; Nakamura et al., Citation2022; Yeung et al., Citation2019). Hao (Citation2008) suggests that concurrent participation in paid work and volunteering can help protect older adult mental health. The authors suggest this supports a “role accumulation perspective” through which participants can benefit from occupying the role itself (volunteer or worker) rather than from the extent of their actual involvement (Hao, Citation2008).

Participation in paid work can form an important component of individual purpose and contribute to a sense of value from fulfillment of a working role. As such cessation of employment, whether voluntary or involuntary, will lead to disruptions in associated purpose if individuals are unable to compensate for the loss of work-related roles or identify new purposeful aims to pursue (Lewis & Hill, Citation2020). Indeed, relative to working older adults, retired participants may report less purposefulness in later life, as well as an incremental decline in sense of purpose following retirement (Hill et al., Citation2022; Lewis & Hill, Citation2020).

The sense of being “useful” formed an important component of purpose for many older adults in this study. Further to this, it has been suggested that if one’s activities and goals are imbued with a sense of usefulness and value to others, this will in turn contribute to mental and physical wellbeing in later life more generally. Available evidence indicates an association between feelings of usefulness, self-rated health, psychological wellbeing, life satisfaction, self-efficacy, mastery disability, social integration, health behaviors or mortality risk (Gruenewald et al., Citation2007; Okamoto & Tanaka, Citation2004). Activities deemed to be socially “productive” have also been linked to good health and wellbeing amongst older adults, including higher quality of life and life satisfaction (McMunn et al., Citation2009).

The act of caregiving contributed to a sense of purpose for some whilst reducing opportunity to pursue purposeful activity for others. The complex interaction between caregiving and purpose has been explored to some degree in the literature. Caregiving responsibilities can hamper the ability to take part in purposeful activity for older adults (Lewis et al., Citation2020). Indeed, some study participants who had or continued to provide informal care to a spouse described restrictions on choice, location and frequency of activities they were able to pursue both individually and as a couple. Conversely, it has also been proposed that caregiving may actually promote the development of a purpose through acts of care itself, a redirection of life goals and the need to reflect on the role and relationship with the care recipient (Hill et al., Citation2020). Caregiving can constitute purposeful activity for an individual and continued engagement with purposeful aims (Hill et al., Citation2020; Lang & Fowers, Citation2019). Purpose for caregivers may also be protective by which caregivers’ sense of purpose can act as a “psychological resource” and help offset caregiver burden (Polenick et al., Citation2019).

Pets provided a source of purpose for a number of older adults interviewed as well as a conduit to increased social interaction with other pet owners. Pet-related activities such as exercising a dog, resulted in the growth of socialization and the establishment of behavioral patterns through which pet owners met up routinely at a set time each week. Studies suggest that the pet ownership can provide comfort and safety, social inclusion and participation, a meaningful role, and purpose through routine and structure (Hui Gan et al., Citation2020). The care of a pet also requires responsibility, organization and competence. Pets may play an important role in promoting purpose through productivity, sense of value and as something to look forward to each day (Hui Gan et al., Citation2020).

Routine, daily activity, self-sufficiency and engagement with valued activities can support quality of life and preserve a sense of purpose into older adulthood (Hupkens et al., Citation2021; Pfund & Lewis, Citation2020; Richard et al., Citation2005). Participation in personally meaningful activity may be particularly important for older adults to supplant sense of purpose formerly fulfilled by social or work-related roles. Taking part in regular general and leisure activities such as sport, community events, hobbies or employment is also associated with greater purpose (Chun et al., Citation2016; Yeung et al., Citation2019). Through the present study many older adults suggested that maintenance of routine, activity and independence provided them with ongoing purpose. This may include keeping a tidy home, producing nutritious meals each day, paying bills and sustaining the upkeep of the home and garden more generally. Group-based physical activity can contribute to feelings of both purpose and of being needed, through meeting one’s responsibility to others in the group to attend, and establishment of a weekly or daily routine and structure (Morgan et al., Citation2019; Zemancová et al., Citation2023). The pursuit of purpose itself can act as a motivator for participation in group activities, beyond social interaction alone (Walker et al., Citation2023).

Taking on “tasks” can increase social contact and physical activity and, in turn, influence better health and wellbeing (Heaven et al., Citation2013). Productive activities such as housework, gardening or volunteering have also been linked with happiness, wellbeing and other domains of successful aging such as slower functional decline and reduced mortality risk (Menec, Citation2003). Although intensity or rigor varied between older adults interviewed, almost all described routines that guided and provided structure to their daily patterns of behavior. Critical to their sense of purpose and autonomy was the ability to exercise control over their schedules and how they chose to spend their time. Whilst the volume and type varied between older adults in the community, each would prioritize activities based on time, energy, health, interest, enjoyment, value, accessibility and available resources.

The maintenance of independence in later life has been described in terms of preserving physical and mental capacities and developing strategies to accommodate progressive disability or illness as needed to remain living within the community (Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Citation2014). Greater dependency can negatively influence self-reported quality of life amongst older people living in the community (Munawar et al., Citation2023). In the present study, purpose, as represented by the protection of such independence, included a focus on promotion of one’s health and wellbeing. Many adults described conscious effort expended to sustain function and mobility through exercise, diet, cognitive stimulation and general self-care. Independence also extended to maintenance of the home and living environment to the best of their ability. Further to this is the importance of “doing things alone” which in itself can support one’s personhood and self-identity in later life (Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Citation2014).

As an important component of self-identity, help-seeking behaviors may be associated with dependency and incapability by some older adults (Goll et al., Citation2015). Indeed, a small number of interviewees articulated a strong resistance to seeking formal or informal assistance in any form. Conversely, others interviewed expressed a sense of empowerment from accepting support to remain in their home. Having sufficient resources to adapt their home, use devices and equipment to support aging in place, and engage formal service providers may further facilitate a sense of independence for older adults through exercising choice and control over how their lives function and are organized (Black & Dobbs, Citation2015; Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Citation2014; Rozario et al., Citation2011).

A smaller group of interviewees described a strong sense of purpose imbued by faith and spirituality. Purpose fulfilled through faith represented the continuation of lifelong practices or a more recent pursuit for older adults. Activities associated with faith in themselves provided a source of community, belonging and friendship delivered through a shared focus and experience with others. Spirituality and faith in God can provide a sense of meaning and purpose across the life span (Moore et al., Citation2006). Spiritual wellbeing can also provide an avenue for continued growth and development in later life (Black & Dobbs, Citation2015). In itself spiritual and religious affiliations and activity participation may be protective of existential elements of wellbeing, including purpose in life (Chun et al., Citation2016; McCann Mortimer, Citation2010). Within the literature, sense of purpose has been correlated with intrinsic religiosity (Francis et al., Citation2010), shared spiritual activities, and frequency of prayer (Ardelt & Koenig, Citation2006). Religious faith as a source of purpose has also been positively associated with mental wellbeing for adults aged 60 years and older (Rainville & Mehegan, Citation2019).

Fundamental to one’s sense of purpose is the value ascribed to such purpose and its potential for fulfillment and realization. If considering the concept of successful aging from the perspective of the older person, it can be reasonable to expect that the role of purpose as a measure of successful aging will be dependent on the value ascribed by the individual. One may consider themselves to be successfully aging without a salient sense of purpose (Lewis et al., Citation2020). Indeed, a small number of adults within this study expressed the belief that having a sense of purpose was not necessary in later life. This may suggest that amongst dominant priorities in life, maintaining purpose may be less important for some. However, it may also be influenced by individual and societal expectations regarding the preservation of purpose across the life span, accompanied by declining opportunities for older people to take part in personally meaningful and purposeful activity. Furthermore, attitudes regarding what is “appropriate” or relevant in “older age” may guide the selection of purposeful pursuits that align with these attitudes.

Study limitations

Whilst the outcomes of this study contribute to the body of current evidence pertaining to purpose in later life, there are several limitations that must be acknowledged. As with many exploratory studies, the sample size, location (predominantly metropolitan and country South Australia) and method of data collection (qualitative interviews) do not enable extrapolation of findings to a broader population of older adults. The method of data collection chosen required the ability for an interviewee to understand and respond to questions regarding sense of purpose amongst other aspects of their lives. Therefore, the findings reflect those without moderate to advanced cognitive impairment or dementia. It is recognized that the experiences of this group are therefore not captured in this study. Through non-probability purposive sampling, older adults across the study volunteered to participate. This will likely represent a bias in the characteristics of the sample in that those more motivated to contribute to this research may have an existing interest in the subject matter or represent those with personality traits more likely to be associated with greater purpose. Results are also skewed toward that derived from female participants and as such future research could seek to provide a more balanced representation. A final point is specific to the word “purpose” itself. Purpose can be interpreted differently and whilst some adults appeared comfortable contemplating what purpose represented at that point in time, others appeared at a loss. This speaks to the complexity of defining and measuring purpose as a psychological construct.

Study implications

Increasingly, researchers support the concept that whilst purpose is considered a reasonably stable trait, it is in itself potentially modifiable and can therefore be enhanced at all stages of life, including older age (Bonnewyn et al., Citation2014; Boyle et al., Citation2009; Yu et al., Citation2015). Even small behavioral strategies and modifications may generate an increased sense of intentionality, usefulness and relevance for older adults (Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, et al., Citation2010). Although there are promising outcomes demonstrated by interventions related to aspects of wellbeing such as meaning in life (Chippendale & Boltz, Citation2015), sense of belonging (Steffens et al., Citation2016), social role development (Heaven et al., Citation2013), positive affect and identity awareness (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2006) the evidence regarding initiatives specific to the promotion, enhancement or development of purpose in later life is less established. Existing conceptualizations of purpose as a psychometric construct have also been more recently questioned with respect to their relevance to older adults specifically (Anderson et al., Citation2022; Shaffer, Citation2021). Therefore, the outcomes of this study may help develop future such measures better reflective of purpose in later life. They can also be applied to the formation of activities or programs designed to promote, support and maintain purpose amongst older people.

Conclusion

Conversations with older adults suggest that the majority continue to value, experience and pursue purpose in their lives. This can be through activities, roles or commitments, or that represented by the preservation of independence, autonomy and sense of self. Perhaps most striking of the outcomes of this study is the diversity of purpose experienced amongst the group. Whilst patterns within discussions were identified, so too was the individualized nature of purpose, both in description and fulfillment. Maintaining purposeful activity has tangible benefits for individuals and society both. An understanding of what purpose represents at different life stages can help inform the design and evaluation of varied initiatives intended to sustain, increase or even re-introduce purpose amongst older adults. Future research efforts may also contribute to a greater understanding of individual, interpersonal, and societal factors that can enable or impede the continued pursuit of purpose in later life.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the men and women who so kindly offered their time and willingness to share their experience of purpose.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Alimujiang, A., Wiensch, A., Boss, J., Fleischer, N. L., Mondul, A. M., McLean, K., Mukherjee, B., & Pearce, C. L. (2019). Association between life purpose and mortality among US adults older than 50 years. JAMA Network Open, 2(5), e194270–e194270. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4270

- Anderson, K. A., Fields, N. L., Cassidy, J., & Peters-Beumer, L. (2022). Purpose in Life: A Reconceptualization for Very Late Life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(5), 2337–2348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00512-7

- Ardelt, M. (2003). Effects of religion and purpose in life on elders’ subjective well-being and attitudes toward death. Journal of Religious Gerontology, 14(4), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1300/J078v14n04_04

- Ardelt, M., & Koenig, C. S. (2006). The role of religion for hospice patients and relatively healthy older adults. Research on Aging, 28(2), 184–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505284165

- Bigler, M., Neimeyer, G. J., & Brown, E. (2001). The divided self revisited: Effects of self-concept clarity and self-concept differentiation on psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20(3), 396–415. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.20.3.396.22302

- Black, K., & Dobbs, D. (2015). Community-Dwelling Older Adults’ perspectives on what matters most: Findings from an exploratory inquiry. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 39(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2015.1025674

- Bonnewyn, A., Shah, A., Bruffaerts, R., & Demyttenaere, K. (2014). Are gender and life attitudes associated with the wish to die in older psychiatric and somatic inpatients? An explorative study. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(10), 1693–1702. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214000957

- Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(5), 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0

- Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Barnes, L. L., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(3), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208

- Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(12), 1093–1102. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6c259

- Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Wilson, R. S., Yu, L., Schneider, J. A., & Bennett, D. A. (2012). Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(5), 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1487

- Bronk, K. C. (2014). Purpose in life. A critical component of optimal youth development. Springer.

- Chen, Y., Weziak-Bialowolska, D., Lee, M. T., Bialowolski, P., McNeely, E., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2022). Longitudinal associations between domains of flourishing. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 2740. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06626-5

- Chippendale, T., & Boltz, M. (2015). Living legends: Effectiveness of a program to enhance sense of purpose and meaning in life among community-dwelling older adults. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(4), p69042700101–p690427001011. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.014894

- Chun, S., Heo, J., Lee, S., & Kim, J. (2016). Leisure-related predictors on a sense of purpose in life among older adults with cancer. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 40(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2016.1199517

- Cohen-Louck, K., & Aviad, Y. (2020). Suicidal tendencies, meaning in life, family support, and social engagement of the elderly residing in the community and in institutional settings. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 57(1), 13–22. www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/suicidal-tendencies-meaning-life-family-support/docview/2546196884/se-2

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Parpura-Gill, A., & Golander, H. (2006). Utilization of self-identity roles for designing interventions for persons with dementia. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(4), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.4.P202

- Eakman, A. M., Carlson, M. E., & Clark, F. A. (2010). The meaningful activity participation assessment: A measure of engagement in personally valued activities. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 70(4), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.70.4.b

- Flood, M. (2007). Exploring the relationships between creativity, depression, and successful aging. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 31(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1300/J016v31n01_04

- Francis, L. J., Jewell, A., & Robbins, M. (2010). The relationship between religious orientation, personality, and purpose in life among an older Methodist sample. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 13(7–8), 777–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670802360907

- Freund, A. M., & Baltes, P. B. (2002). Life-management strategies of selection, optimization, and compensation: Measurement by self-report and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(4), 642–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.642

- Goll, J. C., Charlesworth, G., Scior, K., Stott, J., & Dorner, T. E. (2015). Barriers to social participation among lonely older adults: The influence of social fears and identity. Public Library of Science ONE, 10(2), e0116664–e0116664. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116664

- Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2004). Formal volunteering as a protective factor for older adults’ psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(5), S258–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.5.S258

- Gruenewald, T. L., Karlamangla, A. S., Greendale, G. A., Singer, B. H., & Seeman, T. E. (2007). Feelings of usefulness to others, disability, and mortality in older adults: The MacArthur study of successful aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 62(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.1.P28

- Hao, Y. (2008). Productive activities and psychological wellbeing among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 63(2), S64–S72. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.2.S64

- Haugan, G. (2014). Meaning-in-life in nursing-home patients: A correlate with physical and emotional symptoms. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(7–8), 1030–1043. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12282

- Heaven, B. E. N., Brown, L. J. E., White, M., Errington, L., Mathers, J. C., & Moffatt, S. (2013). Supporting well-being in retirement through meaningful social roles: Systematic review of intervention studies. The Milbank Quarterly, 91(2), 222–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/milq.12013

- Hedberg, P., Gustafson, Y., & Brulin, C. (2010). Purpose in life among men and women aged 85 years and older. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 70(3), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.70.3.c

- Hill, P. L., Best, R. D., Pfund, G. N., Cardador, M. T., & Strecher, V. J. (2022). Older adults place greater importance than younger adults on a purposeful retirement. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 96(2), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914150221106093

- Hillcoat-Nallétamby, S. (2014). The meaning of “independence” for older people in different residential settings. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 69(3), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu008

- Hill, P. L., & Turiano, N. A. (2014). Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychological Science, 25(7), 1482–1486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614531799

- Hill, P. L., Turiano, N. A., Spiro, A., & Mroczek, D. K. (2015). Understanding inter-individual variability in purpose: Longitudinal findings from the VA normative aging study. Psychology & Aging, 30(3), 529–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000020

- Hill, P. L., & Weston, S. J. (2019). Evaluating eight-year trajectories for sense of purpose in the health and retirement study. Aging & Mental Health, 23(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1399344

- Hill, P. L., Wynn, M. J., & Carpenter, B. D. (2020). Purposeful engagement as a motivation for dementia caregiving: Comment on Lang and Fowers (2019). American Psychologist Journal, 75(1), 113–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000511

- Holahan, C. K., & Suzuki, R. (2006). Motivational factors in health promoting behavior in later aging. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 30(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1300/J016v30n01_03

- Hui Gan, G. Z., Hill, A.-M., Yeung, P., Keesing, S., & Netto, J. A. (2020). Pet ownership and its influence on mental health in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 24(10), 1605–1612. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1633620

- Hupkens, S., Goumans, M., Derkx, P., & Machielse, A. (2021). ‘Meaning in life? Make it as bearable, enjoyable and good as possible!’: A qualitative study among community-dwelling aged adults who receive home nursing in the Netherlands. Health & Social Care in the Community, 29(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13071

- Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging With Purpose. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85(4), 403–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415017702908

- Kim, G., Shin, S. H., Scicolone, M. A., & Parmelee, P. (2019). Purpose in life protects against cognitive decline among older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(6), 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.010

- Kim, E. S., Sun, J. K., Park, N., Kubzansky, L. D., & Peterson, C. (2013). Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older U.S. adults with coronary heart disease: A two-year follow-up. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-012-9406-4

- Knight, T., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2003). Successful aging: Perceptions of Adults Aged between 70 and 101 years. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56(3), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.2190/cg1a-4y73-wew8-44qy

- Lang, S. F., & Fowers, B. J. (2019). An expanded theory of Alzheimer’s caregiving. American Psychologist, 74(2), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000323

- Lee, S. (2023). Loneliness, volunteering, and quality of life in European older adults. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 47(2), 250–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2148408

- Lewis, N. A., & Hill, P. L. (2020). Does being active mean being purposeful in older adulthood? Examining the moderating role of retirement. Psychology and Aging, 35(7), 1050–1057. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000568

- Lewis, N. A., Reesor, N., & Hill, P. L. (2020). Perceived barriers and contributors to sense of purpose in life in retirement community residents. Ageing and Society, 42(6), 1448–1464. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001749

- Lewis, N. A., Turiano, N. A., Payne, B. R., & Hill, P. L. (2017). Purpose in life and cognitive functioning in adulthood. Aging, Neuropsychology & Cognition, 24(6), 662–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2016.1251549

- Marton, F. (1988). Phenomenography: A research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. In R. R. Sherman & W. B. Webb (Eds.), Qualitative research in education: Focus and methods (pp. 141–161). Falmer Press.

- McCann Mortimer, P. (2010). Successful ageing: By whose definition?. University of Adelaide].

- McMunn, A., Nazroo, J., Wahrendorf, M., Breeze, E., & Zaninotto, P. (2009). Participation in socially-productive activities, reciprocity and wellbeing in later life: Baseline results in England. Ageing and Society, 29(5), 765–782. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08008350

- Menec, V. H. (2003). The relation between everyday activities and successful aging: A 6-year longitudinal study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 58(2), S74–S82. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.2.S74

- Missler, M., Stroebe, M., Geurtsen, L., Mastenbroek, M., Chmoun, S., & van der Houwen, K. (2011). Exploring death anxiety among elderly people: A literature review and empirical investigation. Omega (Westport), 64(4), 357–379. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.64.4.e

- Moore, S. L., Metcalf, B., & Schow, E. (2006). The quest for meaning in aging. Geriatric Nursing, 27(5), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.08.012

- Morgan, G. S., Willmott, M., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Haase, A. M., & Campbell, R. M. (2019). A life fulfilled: Positively influencing physical activity in older adults – a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6624-5

- Munawar, K., Fadzil, Z., Choudhry, F. R., & Kausar, R. (2023). Cognitive functioning, dependency, and quality of life among older adults. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2023.2193786

- Nakamura, J. S., Chen, Y., VanderWeele, T. J., & Kim, E. S. (2022). What makes life purposeful? Identifying the antecedents of a sense of purpose in life using a lagged exposure-wide approach. SSM - Population Health, 19, 101235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101235

- Okamoto, K., & Tanaka, Y. (2004). Subjective usefulness and 6-year mortality risks among elderly persons in Japan. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 59(5), 246–P249. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.5.P246

- Ornkek, F. (2008). An overview of a theoretical framework of phenomenography in qualitative education research: An example from physics education research. Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, 9(2), 1–14.

- Pfund, G. N., & Lewis, N. A. (2020). Aging with purpose: Developmental changes and benefits of purpose in life throughout the lifespan. In P. L. Hill & M. Allemand (Eds.), Personality and healthy aging in adulthood: New directions and techniques (pp. 27–42). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32053-9_3

- Pfund, G. N., Ratner, K., Allemand, M., Burrow, A. L., & Hill, P. L. (2022). When the end feels near: Sense of purpose predicts well-being as a function of future time perspective. Aging & Mental Health, 26(6), 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1891203

- Pfund, G. N., Strecher, V., Kross, E., & Hill, P. L. (2023). Sense of purpose and strategies for coping with anxiety across adulthood. Geropsych-The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000324

- Pinquart, M. (2002). Creating and maintaining purpose in life in old age: A meta-analysis. Ageing International, 27(2), 90–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-002-1004-2

- Polenick, C. A., Sherman, C. W., Birditt, K. S., Zarit, S. H., & Kales, H. C. (2019). Purpose in life among family care partners managing dementia: Links to caregiving gains. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e424–e432. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny063

- Prairie, B. A., Scheier, M. F., Matthews, K. A., Chang, C.-C. H., & Hess, R. (2011). A higher sense of purpose in life is associated with sexual enjoyment in midlife women. Menopause, 18(8), 839–844. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31820befca

- Rainville, G., & Mehegan, L. (2019). God, purpose in life, and mental well-being among older adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 58(1), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12565

- Register, M. E., & Scharer, K. M. (2010). Connectedness in community-dwelling older adults. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32(4), 462–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945909355997

- Reker, G. T. (2001). Prospective predictors of successful aging in community-residing and institutionalized Canadian elderly. Ageing International, 27(1), 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-001-1015-4

- Richard, L., Laforest, S., Dufresne, F., & Sapinski, J. P. (2005). The quality of life of older adults living in an urban environment: Professional and lay perspectives. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 24(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/cja.2005.0011

- Robertson, K. (2020). Ageing well in a changing world. A report prepared by the commissioner for senior Victorians. Victorian State Government.

- Rozario, P. A., Kidahashi, M., & DeRienzis, D. R. (2011). Selection, optimization, and compensation: Strategies to maintain, maximize, and generate resources in later life in the face of chronic illnesses. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 54(2), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2010.539589

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(4), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395

- Sano, N., & Kyougoku, M. (2016). An analysis of structural relationship among achievement motive on social participation, purpose in life, and role expectations among community dwelling elderly attending day services. PeerJ, 4, 4. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1655

- Shaffer, J. (2021). Centenarians, Supercentenarians: We must develop new measurements suitable for our oldest old [opinion]. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655497

- Sougleris, C., & Ranzijn, R. (2011). Proactive coping in community-dwelling older Australians. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 72(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.72.2.d

- Steffens, N. K., Cruwys, T., Haslam, C., Jetten, J., & Haslam, S. A. (2016). Social group memberships in retirement are associated with reduced risk of premature death: Evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open, 6(2), e010164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010164

- Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Stephan, Y., & Terracciano, A. (2021). Self-reported sense of purpose in life and proxy-reported behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in the last year of life. Aging & Mental Health, 26(8), 1693–1698. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1937055

- Thoits, P. A. (2003). Personal agency in the accumulation of multiple role-identities. In P. J. Burke, T. J. Owens, R. T. Serpe, & P. A. Thoits (Eds.), Advances in identity theory and research (pp. 179–194). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9188-1_13

- Thoits, P. A. (2012). Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75(4), 360–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272512459662

- Troutman, M., Nies, M. A., & Bentley, M. (2010). Measuring successful aging in Southern black older adults. Educational Gerontology, 37(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2010.500587

- Troutman, M., Nies, M. A., & Seo, D. (2010). Successful aging: Selected indicators in a Southern sample. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 22(2), 111–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822309343945

- van Leeuwen, K. M., van Loon, M. S., van Nes, F. A., Bosmans, J. E., de Vet, H. C. W., Ket, J. C. F., Widdershoven, G. A. M., Ostelo, R. W. J. G., & Ginsberg, S. D. (2019). What does quality of life mean to older adults? A thematic synthesis. Public Library of Science ONE, 14(3), e0213263–e0213263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213263

- Walker, R., Belperio, I., Scott, J., Luszcz, M., Mazzucchelli, T., Evans, T., & Windsor, T. D. (2023). Older adults’ views on characteristics of groups to support engagement. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2023.2249722

- WHO. (2020). Decade of healthy ageing 2020-2030. Demographic Change and Healthy Ageing, World Health Organization. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/decade-of-healthy-ageing/final-decade-proposal/decade-proposal-final-apr2020-en.pdf?sfvrsn=b4b75ebc_25&download=true

- Windsor, T. D., Curtis, R. G., & Luszcz, M. A. (2015). Sense of purpose as a psychological resource for aging well. Developmental Psychology, 51(7), 975–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000023

- Yeung, P., Allen, J., Godfrey, H. K., Alpass, F., & Stephens, C. (2019). Risk and protective factors for wellbeing in older veterans in New Zealand. Aging & Mental Health, 23(8), 992–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1471584

- Yu, L., Boyle, P. A., Wilson, R. S., Levine, S. R., Schneider, J. A., & Bennett, D. A. (2015). Purpose in life and cerebral infarcts in community-dwelling older people. Stroke, 46(4), 1071–1076. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008010

- Zaslavsky, O., Rillamas-Sun, E., Woods, N. F., Cochrane, B. B., Stefanick, M. L., Tindle, H., Tinker, L. F., & LaCroix, A. Z. (2014). Association of the selected dimensions of eudaimonic well-being with healthy survival to 85 years of age in older women. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(Special Issue 12), 2081–2091. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214001768

- Zemancová, Z., Dubovská, E., & Tavel, P. (2023). Older adults’ motivation to exercise: Qualitative insights from Czech Republic. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2151807

Appendix

Table A1. Participant Demographic Details.