André Lévy passed away in Bordeaux, France, on October 3 2017 at the age of 91 (). Perhaps best known for his full translation of Jin Ping Mei into French (Gallimard, 1985), he was a pioneering Sinologist in many respects. He published extensively on traditional Chinese literature, in particular pre-modern vernacular literature. His ground-breaking studies in this field include Études sur le conte et le roman chinois (École Francaise d’Extreme-Orient, 1971) and Le conte en langue vulgaire du XVIIe siècle (College de France, 1981). His research also appeared in English as Chinese Literature, Ancient and Classical (translated by William H. Nienhauser, Jr., Indiana University Press, 2000).

Lévy was born in Tianjin, China. His family returned to France when the Sino-Japanese war broke out in 1937. He retained an interest in Chinese language and culture throughout his life. Told that there was no future in studying Chinese, he initially studied Sanskrit at the Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales (National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations), where he met his future wife, Anne-Marie, from Norway. Sent in the late 1950s to Hanoi, Vietnam, he discovered traditional vernacular literature through booksellers who sold books in Chinese.Footnote1 He wrote his thesis on the rise of vernacular short stories in seventeenth-century Chinese literature (1971), followed by several major studies and translations (1972, 1974, 1981). The chair of his jury, René Etiemble (1909–2002), asked him to translate Jin Ping Mei for Gallimard. In Lévy's words:

He thought he had found at long last a fellow who could give him a more complete translation of Jin Ping Mei than those then available in French … .First Etiemble asked me if I could read German. Somewhat taken aback, I said yes. Then, later, he introduced me to the aging head of the Gallimard family and mentioned acquiring the rights to translate into French the brothers Kibat's German version. It was a complete translation of the at that time [1920s] current edition of Jin Ping Mei established at the end of the seventeenth century by Zhang Zhupo 張竹坡. In fact, it was not yet entirely published at the time, but was in production by the Swiss firm Die Waage in Zürich. The fifth and last volume was to appear in 1982. The first was published in 1967, and was in fact a reissue of the ones burned in Hitler's Germany when I was about ten years old, in the thirties. I had to object that precisely in the thirties, a different, more ancient edition had been discovered in China, and that besides I was the lucky owner of a Photostat of a slightly better copy of the same rare edition, this time found in Japan. Third, I pointed out that this cihua edition was likely to be closer to the original manuscript and was not yet translated the world over, but only in Japan were the objectionable portions were left in the original Chinese.

Had I to add that I felt more at ease with Chinese than with German? The arguments hit their target. That is how I was drawn into battling with the not always easy Chinese of the Jin Ping Mei cihua for the next seven years, pretty long ago.Footnote2

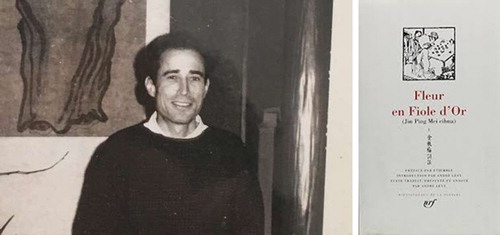

This was the first complete translation of this important novel into a Western language. See for a photo of the cover of the translation and one of Lévy as a young man.

As early as the 1970s and 1980s, Lévy's research was imbued with an attitude of respect and admiration for Chinese professional storytellers that was not en vogue at the time. In Études sur le conte et le roman chinois and Le conte en langue vulgaire du XVIIe siècle he took up with special emphasis the oral sources and the striving for a new writing style, “une écriture vulgarisante.” This was at a time that most Western scholarship was working to show the literary nature of the “storyteller’s manner” in vernacular fiction, arguing against the view put forward by Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881–1936) and others that the novels and short stories were essentially based on real scripts for performance by storytellers. In one of his last publications, Lévy renewed his challenge to the field: “The art of storytelling in China early reached a maturity which calls for a more positive assessment. Its shortcomings may be argued as its strengths … . Its import in Chinese fiction needs more investigation … . An immense field is to be prospected.”Footnote3

Among Lévy's many contributions, he devoted time to making the “extraordinary masterworks” of vernacular Chinese literature accessible for Western readers in elegant and learned editions. His research emphasized the importance of oral storytelling to vernacular fiction early on, opening a rich field.

Selected Books by André Lévy

1970

Ling Mong-tch‘ou: L‘Amour de la renarde, Marchands et lettrés de la vieille Chine. Douze contes du XVIIe siècle. Paris: Gallimard.

1971

Études sur le conte et le roman chinois. Paris, École française d‘Extrême-Orient (Publications de l‘École française d‘Extrême-Orient, vol. 82).

1972

L‘Antre aux fantômes des collines de l‘Ouest, sept contes chinois anciens, XIIe-XIVe siècles. Trad., intro., notes, et commentaires. Paris, Gallimard (Connaissance de l‘Orient, 38).

1978

Inventaire analytique et critique du conte chinois en langue vulgaire. Paris, Collège de France/ Institut des hautes études chinoises (Mémoire de l‘Institut des hautes études chinoise, 8–1).

1981

Sept victimes pour un oiseau, précédé d‘une introduction sur le conte policier ou judiciaire chinois. Neuf pièces traduites, annotées et commentées. Paris, Flammarion.

1981

Le conte en langue vulgaire du XVIIe siècle (vogue et déclin d‘un genre narratif de la littérature chinoise). Paris, Institut des hautes études chinoises.

1985

Jin Ping Mei, Fleur en Fiole d‘Or. Introduction par André Lévy, texte traduit, présenté et annoté par Andreé Lévy, preface par Étiemble. Paris, Gallimard (La Pléiade).

1986

Nouvelles lettres édifiantes et curieuses d‘Extrême-Occident par des voyageurs lettres chinois. Paris, Seghers.

1991

La pérégrination vers l‘ouest. Trad., annotée, et critique du Xiyou Ji. Paris, Gallimard (La Pléiade).

1991

La littérature chinoise ancienne et classique. Paris, Presses universitaires de France. English translation published in 2000.

1992

Histoires d‘amour et de mort de la Chine ancienne. Paris: Aubier.

1993

Histoires extraordinaires et récits fantastiques de la Chine ancienne. Paris: Aubier.

1996

Pu Songling, chroniques de l‘étrange. Arles, Philippe Picquier.

1997

Amour et rancune: récits érotiques, Arles, Paul Picquier.

1997

Les spectacles curieux du plaisir: récits érotiques Arles, Paul Picquier.

1998

Histoires extraordinaires et récits fantastiques de la Chine ancienne. Paris: Flammarion.

1998

Tang Xianzu: Le pavillon aux pivoines. Paris, Musica Falsa.

1999

Les miroirs du désir: récits érotiques. Arles, Paul Picquier.

2000

Chinese Literature, Ancient and Classical. Translated by William H. Nienhauser, Jr. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

2000

Dictionnaire de littérature chinoise. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

2000/2004

Le Sublime Discours de la fille candide. Manuel d‘érotologie chinoise. Arles, Paul Picquier.

2007

Tang Xianzu: L‘Oreillier magique. Paris, MF Collection Friction.

Notes

1 See his obituary, “Mort du sinologue et traducteur André Lévy,” Le Monde, October 4 2017.

2 André Lévy, “Jin Ping Mei and the Art of Storytelling,” in The Interplay of the Oral and the Written in Chinese Popular Literature, eds. Vibeke Børdahl and Margaret Wan (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2010), p. 14.

3 Ibid., pp. 26–29.