ABSTRACT

Librarian-created course guides were created at The Ohio State University using the LibGuides system, with 460 courses being connected to undergraduate courses in six departments. The process of identifying content, creating guide templates and courses, and working with staff members doing remote work projects is covered. A special subset of the guides involves a more intense examination of courses’ content and the collaboration of the campus’s Mathematics and Statistics Learning Center. Guide use in the first semester and future directions are discussed.

Introduction

During Spring-Summer 2020, when The Ohio State University sent home many employees to work remotely, an opportunity rose so that a long-term vision could be implemented. I had long desired to relay library ebooks and journals to undergraduate courses in the departments I serve. Previously, spreadsheets of content have been shared with instructors in the departments, with course-level content. The opportunity for creating a LibGuide for each of these courses thus became possible with remote projects. Previously seen as just a dream due to the large amount of data entry needed, the ability for staff needing remote work led to this work to finally be implemented. The work done to create these course guides was an effort to not only share potential sources of information for use by students in the linked courses, but also to reinforce to instructors the course content options in the hopes of garnering interest in more affordable alternatives to standard student-purchased textbooks.

Literature review

LibGuides is a proprietary platform for which libraries can share content of a variety of formats and purposes. Many libraries offer general, subject-based, and course-specific guides. Dougherty (Citation2013) examined LibGuides targeting geology and found common content across the guides. Many guides had librarian (guide author) profiles. In terms of format of the specific items shared, the most common formats were (in order): books/ebooks, websites, articles, and databases. Other information included societies, maps, media, theses, etc.

Chiware (Citation2014) also created course-specific guides connected to their learning management system at University of Cape Town. In this case, it was for economics courses. An interesting feature of these guides is their connection to essay writing. The librarian met with their School of Economics’ Writing Coordinator in order to include information on the guides related to essay writing within the guide. Perhaps even more significant was the author worked to get detailed feedback from students about the guide in order to improve them.

Bowen (Citation2012) and Stone, Lowe, and Maxson (Citation2018) also focused on a small-scale course-specific projects that had guides tied to courses. Assignments were connected to the guides and student feedback was sought on the guides. One particular interesting tidbit of information Bowen (Citation2012) gathered was whether the students used content outside of the guide (e.g., Google and Google Scholar). Such details of evaluations allow for improvements and potential additions to the guides. However, scaling to larger course guide projects could be challenging.

In terms of usage rates of such guides, McMullin and Hutton (Citation2010) examined August-November 2009 use of subject guides for English, social work, and theater and found that all had under 500 uses per month, with their maxima occurring in one of the middle months (October and November) of the period studies.

In terms of course guides being connected to courses, Adebonojo (Citation2010) was able to get some instructors to connect guides in their course via the learning management system. These guides got higher use than others due to this connection and promotion.

In summary, previous ventures into course- or subject-specific guides has found value in their creation. Guides were usually created in consultation with course instructors and often had assignment connections. Those examining guides with similar topics from multiple institutions have found similar content. While all of these studies involved examining use of library-provided guides, and most in particular course-specific guides, none of these projects covered cases in which a large number of course-specific guides were created such as the one for this project. While there may be common elements to consider, the proactive large-scale creation and connection of course guides is a bit more unique of a project than many others are doing.

Background

The Ohio State University Libraries has long had the ability of creating course-specific guides (using the LibGuides system, previously using a locally developed system). Librarians are able to connect guides to a specific course via a system referred to as Carmen Library Links. The University’s Learning Management System, CANVAS, is branded at the university as Carmen. A Library Link appears in all courses in Carmen at Ohio State via the method outlined in . Unlike Adebonojo (Citation2010), a LibGuide can be connected to courses without the need to go through the instructor or another unit.

For the departments to which I am a liaison, most courses went to a department/program-level subject guide. The subject guides in these cases are also displayed on the public list of subject guides, but not within the list of course guides. A small selection of courses in these departments/programs went to a course-specific guide, which appeared in the public list of course guides. Most courses thus went to the subject guides, but I wished to provide more targeted content to courses.

I had previously created spreadsheets for these departments that contained suggested library-accessed ebooks and videos for most of their undergraduate courses. Selected ebooks and streaming videos were selected based upon the course descriptions provided by the university’s course catalog. The spreadsheets (combined into one workbook with a course number index page), with accompanying affordability information, were distributed to instructors to encourage them to consider library-provided sources as potential course content – and/or to start a conversation about affordable course content. This information was based solely upon course descriptions provided by the Course Catalog (the university’s listing of courses with descriptions).

The provided material would also be good content for course-specific guides. However, due to the number of departments and courses involved, creating this many LibGuides is a large undertaking.

I am a liaison to several departments:

Civil, Environmental and Geodetic Engineering

Includes separately listed courses for Environmental Engineering

Computer Science & Engineering

Earth Sciences (School of)

Includes separately listed courses for Geodetic Science

Geography

Includes separately listed courses for Atmospheric Science

Mathematics

Statistics

This means hundreds of courses exist that could have their own course guide. For some time, creating course-level guides for the undergraduate courses was a dream made unobtainable due to the sheer volume of data entry in the LibGuides system (much more complicated than an Excel workbook).

Creating the GUIDES

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Libraries employees were sent home to work remotely. Projects that could be worked on remotely were solicited to give meaningful work to those employees whose positions were heavily tied to physical collections or facilities. Working on course guides could thus potentially be distributed across multiple people rather than all of it falling just on myself.

Around the same time, Ohio State’s Mathematics and Statistics Learning Center (MSLC) approached me to ask about making materials at the time shared in a single subject LibGuide for both the Mathematics and Statistics Departments (assigned as the default Library link for the departments’ courses in Carmen Library Link) more discoverable. This seemed like a more detailed subgroup of guides for the project already in mind. The courses the MSLC works with could thus see more in-depth search for applicable information sources, using syllabi and topic/content lists. Working with the MSLC was similar to Chiware (Citation2014) working with the School of Economics. outlines the content of a course guide created during this project.

The department/program common content (the left side of the figure) would be common to each course guide in the department/program. The content was usually copied from an existing subject guide for the applicable area. This content was consistent across all newly created course guides for the department/program, allowing for some consistency, continuity, and scalability for most of the content.

The content that did change involved two boxes on each guide. Blank content boxes for recommended ebooks and streaming videos were inserted as holding places. The guide was then replicated multiple times and each guide given the name, and a short URL, using the course number.

Then for each guide, the ebook and video content was added as outlined in .

For the courses discussed with MSLC, a much deeper level of search and examination for ebooks and videos was conducted than was previously done for the spreadsheets. Topic lists provided by the MSLC, plus syllabi and course descriptions, led to a much deeper list of items and the videos for many courses were divided up into multiple topical boxes rather than a single box. outlines this process.

In terms of the telework component, four staff members were part of this project. Their work is outlined in .

Note that the mathematics and statistics course guides created with input from the MSLC had more overall content, so mathematics and statistics tended to have some additional videos for those courses that would otherwise not have been there.

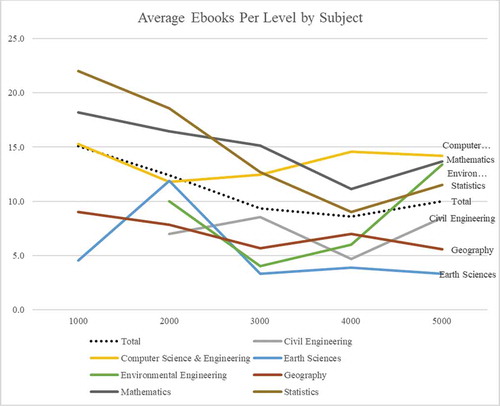

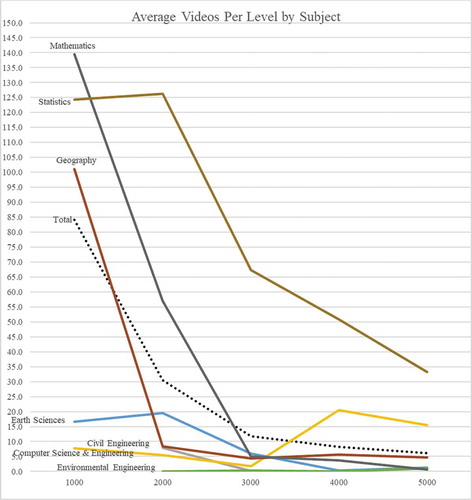

In all a total of 460 courses were created with 4,851 ebooks and 8,453 (these numbers include replications in multiple guides). shares the number of items of each type per course level for each course subject area.

Table 1. Ebook and Video Counts Per Guide*

Average number of ebook titles

Note that in this section, Atmospheric Science and Geodetic Science were removed from analysis due to the low number of courses.

On average, the number of ebooks per course was highest for 1000 level courses and decreased, but then saw an uptick at the 5000 level. Environmental Engineering (starting at 2000 level instead of 1000), Mathematics and Statistics aligned to this pattern. Geography (note Geography only had one 1000 level course guide created). And Earth Sciences saw a decline and then increase at the 4000 level before dropping again at the 5000 level. Civil Engineering’s (also starting at the 2000 level) pattern was the most diverse between levels. See for an overview of these averages. Note that Atmospheric Science and Geodetic Science not shown due to low number of courses

Average number of video titles

Statistics had the highest average, except for the 1000 level, than the other subjects. This is likely due to the heavily interdisciplinary nature of statistics as it is used in many areas of the sciences and social sciences. One of the major sources for statistics videos, Sage Research Methods, heavily targets the social sciences, for example. Statistics had a total average of over 75 videos per course – nearly twice as much as the next highest subject, mathematics.

Geodetic Science, Environmental Engineering, and Civil Engineering tended to have few videos on average, with only Civil Engineering averaging more than one video per course guide. See for an overview of these averages.

In general, the pattern was for there to be more videos for lower-level courses than upper-level courses. Some exceptions include:

Computer Science & Engineering having more videos at the upper levels. This is heavily due to videos within the O’Reilly (formerly Safari) platform.

Earth Sciences and Statistics saw a bit more videos, on average, for 2000 level courses than 1000 level courses.

Note again that Atmospheric Science and Geodetic Science were not graphed due to low number of courses

My assessment of coverage

This section gives an idea of how well content aligned to courses so when others are examining library collections for content, they will have a general sense of how much of different formats to expect for different course types and/or levels.

In general, my assessment is that courses covering topics of broader interest, or that are used in multiple disciplines, tended to have more content matching than those of more niche interest. In terms of broader interest, introductory content for Earth Sciences was plentiful as topics like earthquakes and volcanoes are available from a wide range of sources.

Statistics topics are a prime example of interest across multiple disciplines as many disciplines, especially in the sciences and social sciences, make use of statistical methods. Several subject areas are of much more niche interest, especially as the course level increased. Hence, fewer videos and often fewer ebooks.

Note again that the guides created with input from the MSLC had more overall content, so mathematics and statistics tended to have some additional videos for those courses that would otherwise not have been there.

See for an overview of coverage assessment. This includes all of the discplines involved and for both ebooks and streaming videos.

Table 2. Gives a more specific outline for the assessment for these subjects for both formats

Guide use

For Fall 2020 semester, the 460 newly created guides had a total of 5,102 views. indicates the number of guides, views, and views per guide for each area for which guides were created. The department with the highest views per guide was CSE, followed by MATH and STAT. All other areas were below the average of 11.1 views per guide. Of the 460 guides, 258 guides (56.1%) had less than 5 uses. A good number of these low-use guides are aligned to courses not offered in Fall 2020, the period examined and the first full semester for which they were available.

Table 3. Guides by Area

shares the ten most used guides, which accounted for 36.4% of the total guide use. Note that all of the courses listed for MATH and STAT are courses that the MSLC regularly works with. The MSLC connection likely increased the usage of these guides.

Table 4. Guide Views Fall Semester – Top 10 Course Guides from Project

EARTHSC 1105 was previously attached to a related subject guide (and the course guide was based on this more advanced guide, an exception to the usual process). EARTHSC 1100 was one in which I was working with the instructor to increase free/library course content.

The most surprising courses in the top ten most used guides were the CSE courses. Other than communicating to instructors the existence of these guides (communicated on 08/17/20 and 10/29/20). There was no additional connection with course instructors or any tutoring program, similar to the others. Thus, these guides’ use is very likely due solely to instructor promotion due to those communications.

A guide not included in this study was an established guide for a course I regularly visits. I visited in the Fall 2020 semester and the guide was used as a basis for a presentation and for students to use to complete an assignment. This guide was used 332 times, putting it behind two guides for which there was no librarian presence in the courses. While most of these top-used guides were used less, they were used without specific librarian involvement in the course or known alignment to specific assignments. The use is thus far satisfactory, but I hope to see increased use as instructors are reminded of their availability.

Note: Screenshots of two of these course guides () can be found in Appendix A.

Considerations for the future

The spreadsheets on which the guides were based were updated over the summer to add new content. Updating the 460 guides mean a lot of work. Therefore, represents a potential workflow for these course guides in the future.

Additionally, over summer, it would make sense to see if new courses have been created and to create guides for those courses. The previous guide creation workflows would be used except that they would not be based upon previously gathered Excel worksheet content.

Conclusion & future directions

The work done to create these course guides was an effort to not only share potential sources of information for use by students in the linked courses, but also to reinforce to instructors the course content options in the hopes of garnering interest in more affordable alternatives to standard student-purchased textbooks.

In terms of the students, the hope is students will see specific items relevant to their course and explore more. They will use the ebooks and/or videos to better understand concepts and to explore search tools to go beyond these sources.

In terms of instructors, the hope is that seeing library resources related to their course will encourage them to think beyond standard textbooks that require student purchase. If the items are not ideal, they can request assistance with find other affordable content. Perhaps students will even bring up these sources with their instructor.

The more in-depth guides created in consultation with the MSLC additionally serve as options for students needing additional resources for further instructional assistance on specific concepts identified by the MSLC and/or syllabi.

Videos in particular were important inclusions for these guides as this format is an increasing demand by instructors. It is important to note that Dougherty (Citation2013) mentioned media not being in the most common formats found on geology guides. However, note the year of the study was at a time when streaming media was not as heavily prevalent in some libraries. Ohio State had a much more limited selection of streaming videos in 2013. Most of the videos on the guides created for this project were not available at Ohio State in 2013.

Chiware (Citation2014) received valuable information from users about the guides. It would be potentially useful to do the same for the guides created in this project, although the focus might be better done on a subset, such as the MSLC-related guides.

Relating back to McMullin and Hutton (2010), which saw increased use in the middle of the period examined, it might be interesting to see if any guide shows an extreme uptick in use in a short period of time. This would point to the possibility of a guide being used for an assignment without the librarian being informed of such use by the instructor. This opens up the possibility of an opportunity for some deeper collaboration.

Bowen (Citation2012) and Stone, Lowe, and Maxson (Citation2018) involved feedback in their guide project, but it would be much more challenging to provide opportunities for feedback on 460 guides. A feedback form may provide for some simple feedback for those that visit the guide, but something more systematic would take a lot of logistics due to scale.

The COVID-19 pandemic set up a situation in which remote work was needed and data entry in the LibGuides system fit this bill. This was a valuable opportunity for meaningful work and to complete a large-scale project. The methodology of completing the project could be transferrable to others, such as using student workers for data entry. Those wishing to complete such a project may consider scaling such a project to fewer courses, especially if they do not already have a source list readily available such as the Excel workbooks this project used as a base. Remote work, an essential part of this project, does not need to be a pandemic-only situation. Perhaps student workers could complete the data entry remotely, without needing to be in a library location.

The biggest future direction is the long-term management of these guides. All 460 of these guides are not likely to see extensive use. In the end, it is likely to see the sunsetting of many of these guides (especially those for rarely-taught courses), continue promotion of lower use (but still used) guides, and continuing improvement and potential in-depth relationship with instructors of high-use guides.

References

- Adebonojo, L. G. 2010. LibGuides: Customizing subject guides for individual courses. College & Undergraduate Libraries 17 (4):398–412. doi:10.1080/10691316.2010.525426.

- Bowen, A. 2012. A libguides presence in a blackboard environment. Reference Services Review 40 (3):449–68. doi:10.1108/00907321211254698.

- Chiware, M. 2014. The efficacy of course-specific library guides to support essay writing at the University of Cape Town. South African Journal of Libraries & Information Science 80 (2):27–35. doi:10.7553/80-2-1522.

- Dotson, D. 2020a. CSE 2111. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://guides.osu.edu/cse2111

- Dotson, D. 2020b. STAT 1430. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://guides.osu.edu/stat1430

- Dougherty, K. 2013. Getting to the core of geology libguides. Science & Technology Libraries 32 (2):145–59. doi:10.1080/0194262X.2013.777233.

- McMullin, R. and J. Hutton. 2010. Web subject guides: Virtual connections across the university community. Journal of Library Administration 50 (7–8):789–97. doi:10.1080/01930826.2010.488972

- Stone, S. M., M. S. Lowe, and B. K. Maxson. 2018. Does course guide design impact student learning? College & Undergraduate Libraries 25 (3):280–96. doi:10.1080/10691316.2018.1482808.

Appendix A.

Example from a CSE course guide (CSE 2111) (Dotson Citation2020a):

Figure A1. CSE 2111 Guide

Example from a STAT course guide (STAT 1430) (Dotson Citation2020b):