Abstract

Aims

Performing the Perceive, Recall, Plan and Perform (PRPP)-Assessment, using video material of everyday life, seems sensible to lower the patient burden, enhance ecological validity, and provide care at a distance. However, receipt of adequate video material is not self-evident and assessing videos can be challenging. Therefore, this study aims to optimize the process of gaining video material and to optimize the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos.

Methods

An action design research method was used, focusing on implementation of the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos within the care of children with a mitochondrial disorder or similar symptoms.

Results

Five cycles were conducted. To receive input, the cycles used videos of nine children performing activities, written feedback, and semi-structured interviews and focus groups comprising parents (n = 13), a teacher (n = 1), occupational therapists (n = 16), and other professionals (n = 2) . This led to successful implementation of the PRPP-Assessment. General lessons were learned on (1) instructing parents; (2) handling video material; (3) PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos; and (4) PRPP-Assessment of children (with limited functional abilities).

Conclusions

Lessons learned should be implemented in practice and are incorporated into a manual to guide the implementation of video-based observations with PRPP-Assessment in practice.

Many healthcare professionals are interested in the natural course of disorders and therefore conduct various measurements, the ecological validity of which (i.e., correspondence to performance in daily life) can be discussed (Schmuckler, Citation2001). Information collected on the everyday lives of patients can be used to enhance ecological validity. Data collection in a home environment is now a point of interest as COVID-19 has created a need for care at a distance. Moreover, home treatment is an increasing method of treatment which has the advantage of treating children and their parents in their own context.

Occupational therapists (OTs) are familiar with the use of video material of patients to get insight on everyday functioning. One could argue that video observations have limitations compared to real life: the presence of a camera can result in deviating behavior, and a camera lens cannot take in all aspects of an event (Sparrman, Citation2005). However, there is profound evidence that using video observations for assessments results in valid outcomes and can be beneficial for the children and parents as it has a low burden (Boonzaaijer et al., Citation2017; Curby et al., Citation2016; Houwink et al., Citation2013). A way of analyzing video observations to gain insight into everyday functioning is to use the Perceive, Recall, Plan and Perform System of Task Analysis (PRPP-Assessment). This is an observation-based criterion-referenced measure which was developed to assess the occupational performance of people with information-processing difficulties (Chapparo & Ranka, Citation1996, Citation1997). It can be administered based on live observations or video material (Chapparo, Citation2017).

With the PRPP-Assessment, the OT uses task analysis to examine mastery of an activity and the effectiveness of cognitive information processing. An example of an observed task with the PRPP-Assessment is given in . The psychometric properties of the PRPP-Assessment in children with and without disabilities have shown sufficient to good reliability and validity (Lowe, Citation2010; Mills et al., Citation2016; Nott et al., Citation2006, Citation2009; Stewart, Citation2010). Criterion-based assessment are encouraged to use as they are client-centered and thus applicable in atypical functioning children (Bailey & Simeonsson, Citation1988; Keller et al., Citation2005; Linton, Citation1998; McLaren & Rodger, Citation2003; Simeonsson et al., Citation1982). As the task performance and cognitive strategies in the PRPP-Assessment are criterion-referenced, it provides a focus for person-centered intervention and outcome measures (Chapparo, Citation2017).

Table 1. Example of the PRPP-Assessment on a selected task with the criterion and the scoring of the observed performance for stage 1 and an example of a PRPP-Assessment item for each quadrant.

In the past few years, we have explored the benefits of using parent-provided videos with the PRPP-Assessment instead of observation in the hospital in the care of children with mitochondrial disorder, a rare disease that affects energy metabolism. This disorder causes a large range of symptoms and impairments associated with mitochondrial disorder, varying from motor impairments (such as muscle weakness or balance problems) to cognitive impairments (such as concentration problems and intellectual disability), that have a tremendous impact on daily functioning and participation (Dassler & Allen, Citation2014; Koene et al., Citation2013). For this target group, the use of videos is extremely relevant as they do not have to spend energy on hospital visits and it can prevent long travel times. Also, video material provides an opportunity to gather information at multiple points in time, allowing a representative overview of the fluctuating functioning of this target group (Dassler & Allen, Citation2014). Hence, administering the PRPP-Assessment using video material strengthens the ecological validity (Bouwens, Citation2009; Schmuckler, Citation2001) as it gives a more representative insight into the actual, fluctuating performance of daily activities.

Parents were asked to deliver videos of their child with a mitochondrial disorder performing everyday activities before the first appointment with the OT in the hospital. In practice, receiving adequate video material was not self-evident and OTs faced several challenges in assessing the video material (Lindenschot et al., Citation2021). Hence, the current study focused on optimization of the process of assessing children with the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos. A cyclical process of implementation and evaluation has been used in an action design research (ADR). This ADR should lead to optimizing the PRPP-Assessment in a specific target group within the University Hospital, and the distant outcome on generalizing the lessons learned and summarizing these in a manual for the implementation of video-based PRPP-Assessment in daily practice.

Therefore, we defined two aims to overcome implementation challenges: firstly, we sought to refine the process of gaining video material to yield feasible material for assessing the everyday functioning of children with mitochondrial disorder; and secondly, we aimed to ensure that PRPP-Assessment based on video material is adequately applied by OTs.

Methods

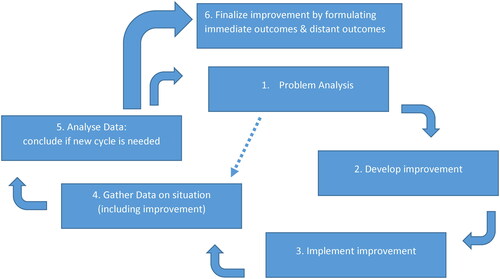

To overcome implementation challenges with the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos of their children, an ADR method (Collatto et al., Citation2018; De Villiers, Citation2005) was used. presents an overview of the iterative action design cycle, showing that repetition of the cycle leads to a solution to an identified problem and general design principles.

Figure 1. Overview of the iterative action design cycle (adapted from De Villiers, Citation2005) used in this research.

Context of Study

This study was performed in the Radboud University Hospital in Nijmegen in the Netherlands, where parents of children aged between two and 18 years with a genetically confirmed mitochondrial disorder received written instructions to make video material of three daily activities before coming to their appointments in the hospital. These children were periodically evaluated by a multidisciplinary, medical, and allied health care team at Radboud Center for Mitochondrial Medicine (RCMM).

Action Design Research (ADR) Process

Each cycle followed the same steps (): (1) problem analysis; (2) develop improvement; (3) implement improvement; (4) gather data on situation; and (5) analyze data. After these five steps, a new cycle was started or, when no new questions were raised, the study was finalized. Using this method, we report on the start of the study (the first cycle), as subsequent cycles were based on the results of each previous cycle. During each cycle, a log was kept by the researcher and frequently discussed with the research team to monitor progress.

To start the first cycle of ADR, previous research (Lindenschot et al., Citation2021) indicated that the current problem was that the instructions to parents of children with a mitochondrial disorder did not lead to adequate video material, and OTs experienced challenges when using the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos. For example, completion of the criterion was not captured on the video (e.g., wanting ‘to score in soccer’ and captured on video is the child but not the goal), making it impossible to score the task and cognitive strategies criterion-referenced. Therefore, the objective of the first cycle was to improve the instructions to parents, resulting in adequate videos, solving the challenges experienced by the OTs.

Step 1: Problem Analysis

The previous study (Lindenschot et al., Citation2021) gave enough directions to develop improved instructions which could be implemented in daily care.

Step 2: Develop Improvement

It was recognized that it was necessary to give more information on the choice of activity (e.g., it should fit with weather conditions and should be challenging enough for the child); the content of the video (e.g., completion of the criterion should be captured on video and the video should start before giving instructions to the child); and the way the video should be made (e.g., choose a device that influences the child’s behavior the least). Therefore, these topics were described in more detail in the written instructions. A short questionnaire was developed to gather the information needed by OTs to adequately perform the PRPP-Assessment based on the video material.

Step 3: Implement Improvement

The written instructions and questionnaire were sent by email to four parents from different backgrounds (level of education, socio-economic status, and age varied) and four professionals (two occupational therapists, a physiotherapist, and a physician).

Step 4: Gather Data on Situation

The parents and professionals were asked if the text was relevant, comprehensive, and comprehensible, based on the aspects of content validity (Mokkink et al., Citation2009). Parents and professionals were asked to give written feedback on the instructions and questionnaire.

Step 5: Analyze Data

The feedback was reviewed and discussed with the research team. The outcome is reported in the results.

Fitting with ADR, only the methods of the first cycle of ADR were known prior to the study as the data collection method was adapted to the problem analysis. It was planned to use a combination of qualitative methods (semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups) with a variety of participants—parents and OTs. For the analysis, content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) was chosen as an overall suitable method.

Ethical Considerations

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (World Medical Association, Citation2013). The ethical board of the regional research committee provided its consent (ethical board approval number 2018-4169). All parents and professionals signed informed consent. Where indicated, the children also signed the informed consent to recognize their volition/agency (Stafford et al., Citation2003).

Results

To reach the aims, three cycles have been conducted for the first aim of improving the process of gaining video material suitable for scoring with the PRPP-Assessment, and two cycles for the second aim of optimizing the application of the PRPP-Assessment by OTs based on parent-provided videos. The cycles will be summarized in chronological order, organized according to the steps of ADR () and elaborated in . For specific results by cycle, we refer to the supplementary data in Appendix 1. Following this, the overall distant outcomes will be discussed briefly.

Table 2. Overview of the action design research (ADR)-cycles and steps.

Overall, the ADR process was spread over 27 months, in which the first four cycles covered 13 months. Throughout the process, 13 parents, one teacher and 25 healthcare professionals participated in data-collection. gives an overview of all cycles.

Summary of ADR Cycles

Aim 1: Optimize the Process of Gaining Video Material for Assessing Everyday Functioning of Children with Mitochondrial Disorder

Cycle 1: Improving Instructions to Parents in Order to Collect Adequate Video Material

Existing instructions for parents to provide video material on their children’s activities were improved by adding information and were accompanied by a short questionnaire (see Methods).

The eight respondents (see Methods) provided written feedback on content validity, which was mainly on the level of formulating sentences. Improvements were implemented by rephrasing and shortening the text and adding examples from practice. Respondents stated that the process of transferring video material seemed time-consuming and professionals worried about the ethical considerations. Therefore, the next cycle focused on the feasibility of the process of gaining video material according to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Cycle 2: Improving the Feasibility of the Process of Gaining Video Material in Line with GDPR

Based on the written feedback of cycle 1, the instructions were further clarified and made more concise. The transfer method needed to be digitally safe and in line with GDPR, informing other persons that were captured on the video material. Therefore, consent form for people who were captured on the video but were not the subject of study was added to the instructions.

To achieve feasibility, the parent should be able to videotape, store, and transfer the video, and the OT should then be able to watch this video in a safe surrounding. The arQive medium showed most potential, as parents were able to upload media files (videos, photos, and/or text) and professionals could be assigned to specific videos and was added to the instructions.

Two weeks before the OT appointment in the hospital parents received an e-mail with the invitation, the instructions, the questionnaire, and the form to inform other people. Videos were uploaded by parents on arQive.

Parents were interviewed after the appointment using a semi-structured interview, which was analyzed by content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Topics were the instructions and questionnaire, the feasibility of making videos, choices of activity, and the ecological validity of the filmed activities.

After three interviews, two with parents successful in uploading videos and one parent who was not, enough information was collected to start a new cycle with improvements.

Analysis resulted in three themes: the process of gaining video material, the content of video material, and the added value of video material. Appendix 1 gives an in-depth report on the results. In summary, all parents acknowledged the importance of the video material to get a good understanding of everyday life, and were motivated. One parent stated that it was not clear to her how to transfer the videos. Parents stated that the instructions were long, and it was not clear what was necessary for care or for research. Also, parents experienced problems with storage capacity. Therefore, another cycle was started to improve the process.

Cycle 3: Further Improve the Feasibility of the Process of Gaining Video Material

Based on the outcomes of cycle 2, the forms were made more concise, and the process was split into an instruction for the usual care and an invitation for participation in research. The invitation to take part on the research was given during the visit to the hospital. In the meanwhile, arQive invented an app to directly film from the phone or tablet, which made storage capacity on a tablet or phone and transferring files redundant.

Because of a low referral rate of patients with mitochondrial disease in the hospital during the inclusion period, a nearby rehabilitation center linked to special education responded positively to the request to collaborate to reach more children. The instructions were further refined by the OT working in this center and experienced in adapting texts to all levels of education. Children without mitochondrial disorder, but with motor and cognitive disabilities and known to have fluctuations in functioning were recruited by the OT and the teacher.

Five semi-structured interviews were conducted—four with parents and one with a teacher—with the topic list from cycle 2. All participants were successful in making and uploading the video material. Interviews were analyzed by content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005), resulting in three themes: the process of gaining video material, the content of video material, and the added value of video material (see Appendix 1 for in-depth results). We confirmed the instructions were clear and resulted in adequate video material. Remaining questions could not be covered in a general instruction and we proceeded to the second aim.

Aim 2: Adequate Appliance of the PRPP-Assessment by OTs Based on Video Material

Cycle 4: Identify Challenges When Using the PRPP-Assessment Based on Parent-Provided Videos of Children

As previous cycles did not incorporate the OT perspective, it was unknown if and what challenges OTs experienced when using PRPP-Assessment based on the parent-provided videos. Therefore, seven pediatric OTs certified in PRPP-Assessment scored six parent-provided videos of children performing an everyday activity. Next, a three-hour focus group was conducted by two moderators (ML and LT) to discuss the scores and experiences of the PRPP-Assessment. Notes were taken and, after each discussed case, summarized and checked by participants. Four cases were discussed, which led to saturation of data.

Although several challenges were uncovered (see Appendix 1), the major insight was that the OTs struggled with reasoning from a criterion-referenced perspective instead of their usual reasoning from a norm-referenced perspective. This reasoning based on developmental age led to inadequate results. Remarkably, the insights mostly focused on principles of the PRPP-Assessment applied to children in general. This conclusion gave input for the next cycle in which we aimed to implement training to overcome the identified challenges and then gather data on remaining challenges.

Cycle 5: Identify and Overcome Remaining Challenges after Training Based on Cycle 4

Three experts designed refresher training for pediatric OTs, which was implemented within psychometric study of the PRPP-Assessment of children with mitochondrial disorder (Lindenschot et al., Citation2022). The course consisted of a four-hour session with homework (score video material of a child). During the training, video material was discussed, and theory was refreshed based on the points of interest arising from cycle four. The refresher training was followed by 13 OTs: two OTs declined further participation due to personal circumstances which limited their available time.

In the psychometric study (Lindenschot et al., Citation2022), 65 activities were videotaped. The videos were randomly assigned to the 11 OTs in such a way that each OT scored five or six children with an average of 14 activities in total. These OTs participated in semi-structured interviews (n = 7) to identify challenges in PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos, and a focus group interview (n = 5) on ways to overcome these challenges. Three OTs participated in both. Two of the 11 OTs did not participate in the interviews due to limited time. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all interviews were conducted online. Data were transcribed and analyzed by inductive coding.

The results could be divided into three themes related to challenges on the level of: (1) assessing children with mitochondrial disorders; (2) assessing with the PRPP-Assessment based on video material; and (3) assessing children with the PRPP-Assessment in general. Most profound was the importance of clarity of the criterion on the part of parents and/or teachers and the difficulty of assessing children with very limited functional abilities, both leading to difficulties in conducting the task analysis as part of the PRPP-Assessment. Also, formulating steps in the task analysis when tasks are short or parents (undesirably) intervening in task performance can be challenging. An extensive report on Dutch results can be found in Drueten et al. (Citation2021) and upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. As an outcome of the focus group, several recommendations could be made for training OTs and, in the manual, for applying the PRPP-Assessment. This led to the conclusion that the second aim was reached. Based on the results, the PRPP-Assessment on parent-provided videos of children with mitochondrial disorder is feasible and applicable for use in a hospital or research.

Overall Distant Outcomes

During the optimization, several lessons were learned, fitting with the two aims and the distant outcomes that are a feature of development research (De Villiers, Citation2005). The lessons learned can be divided into four areas: (1) instructing parents; (2) handling video material as part of the process of gaining video material; (3) PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos; and (4) PRPP-Assessment of children (with very limited functional abilities) as part of adequately assessing the video material. Next, we will elaborate on these four areas. In , a concise overview of the lessons learned is presented. Overall, the lessons learned can support OTs with implementation of the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos or other video-based observation instruments in practice.

Table 3. Overall lessons learned.

Instructing Parents

Balancing Information

On the one hand, it is important not to give parents too much information so that they do not want to read or cannot remember the instructions; on the other hand, it needs to be enough to make sure they know what is expected. Some information on the PRPP-Assessment helps parents understand why it is important to capture the child and the context on video. Parents should be instructed to intervene only when it is necessary to reduce frustration or to keep the activity going. Knowledge of the aim and content of the PRPP-Assessment can support this behavior.

Choice of Activity

All everyday activities can be observed, but activities should fit with the conditions—for instance, the weather conditions. Video material suitable for scoring with the PRPP-Assessment requires activities that are sufficiently challenging, allow room for improvement, and are complex enough so that task analysis results in more than two steps. Also, parents should preferably choose activities in different occupational areas to get an insight into the whole scope of everyday life.

Method of Filming

It is important to use a device that is the least conspicuous for filming actual performance and child behavior. The whole body of the child should be visible, along with the objects or people the child interacts with. Filming the whole task is important—before the child starts, searching information, and when the child is completely ready—no matter the duration of the activity. Also, given instructions and the (non-)verbal reactions of the child should be captured.

Privacy Legislation and Ethical Considerations

Considering the GPDR, everyone filmed needs to give informed consent. When impossible, an alternative is to blur people or cut the video before transferring the video to others. Parents should be aware of this before making the video and use the informed consent for others.

Even when using a safe transferring method, digital safety is never guaranteed. Therefore, parents should not film their children in a vulnerable situation. For example, when showering is an activity, the child could wear a swimming suit.

Handling Video Material

Capacity for Storage

The storage capacity can influence the choice of device used to make the video material. The capacity should be enough to capture the whole activity. Each videotaped activity uses 5–700 MB, with an average of 200 MB.

Transferring Method

There should be an easy way of transferring the video material that is understandable for all parents. Preferably, this is a non-time-consuming method.

Privacy Legislation

For both storage and transferring method, privacy legislation should be adhered to. The process needs to be ethically approved and digitally safe. Ways to achieve this are mentioned in the manual, but are dependent on local legislation.

PRPP-Assessment Based on Parent-Provided Videos

Additional Information Needed from Parents

Additional information can be captured by providing a questionnaire, asking for additional information within the transferring method, or in a telephone call. Additional information on the activities should give knowledge on the familiarity of the activity, the (usual) context, and the assignment and criterion of each filmed activity. Preferably, additional information will be given on the child, the overall functioning, and the areas of concern.

Scoring What You See in Relation to the Criterion

OTs can only score behavior that they see on the video material, and they should only score behavior that impacts the criterion—for instance, they should only score additional behavior if it impacts the task or criterion. If a child does irrelevant things that do not impact the criterion, it should not be scored in the PRPP-Assessment. When parents intervene too quickly according to OTs, it may be helpful to check whether the cognitive strategy used by a parent is adequately applied in other steps. Alternatively, it can be noted with the results.

PRPP-Assessment of Children with Very Limited Functional Abilities

Knowledge of Child Development

OTs were tempted to use knowledge of child development or the child’s disabilities to score phase 2 of the PRPP-Assessment. For instance, they would score inadequate behavior correct with the argument that ‘it is not expected at this age’ or ‘the child cannot do better due to their condition’. However, if it impacts the criterion set by child and parents, inadequate behavior should be scored as ineffective strategy use. It was found to be helpful to use adults as a frame of reference in scoring the PRPP-Assessment (e.g., think ‘What if an adult did this? How would I score it?’).

Knowledge of Interventions

Knowledge on possible interventions should not influence scoring of the PRPP-Assessment. For instance, some OTs felt that children could be better organized and therefore scored the descriptor ‘organizes’ as ineffective strategy use, while the organization did not impact the criterion. The rule of thumb is that you only score what impacts the task and criterion. It is important to be aware of the connection between phase 1 and phase 2: if the score in phase 1 is 100 percent, the score in phase 2 is also 100 percent, as there are no errors in phase 1 that need to be explained in phase 2.

Behavior versus Activity

In the Netherlands, OTs are not familiar with use of the PRPP-Assessment for children with very limited functional abilities. They found it difficult when a parent or caregiver provided a lot of support during the activity and the criterion focused on the behavior of the child—for example, cooperating when getting dressed. It can be helpful when scoring children that have lower abilities on a behavioral criterion to perform a task analysis of behavior in phase 1 instead of the activity—for instance ‘allows mother to lift arm’, ‘sits quietly’, ‘looks at mother’s gestures’, ‘allows mother to straighten shirt’.

Discussion

This study aimed to overcome implementation challenges by studying the process of gaining video material and the way OTs assessed children with the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos. Two important stages in the process were uncovered and optimized. Firstly, the process of gaining video material was optimized, which involved optimizing data collection by parents through improving instructions to parents and making the process feasible and ethically approved. Secondly, use of the PRPP-Assessment by OTs based on video material was improved. Overall, the large amount of data and experiences led to the development of a Dutch manual that can be used by OTs when implementing the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos. Subsequently, the manual could be transferred to other assessments that use video-based observations, as it provides an overview of all the lessons learned and gives directions, forms, guidelines, and examples for the overall process of collecting and assessing the information.

This study is the first study to discuss lessons learned for PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos. Guidelines for the PRPP-Assessment exist, and training OTs in the PRPP-Assessment is done using video material. However, the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos did not receive attention prior to the current study. Even though the lessons learned concerning the use of the PRPP-Assessment based on video material might not be new for PRPP-trained OTs, they deserve more attention when using parent-provided videos compared to live observation. In addition, we found that one of the most important determinants of successful PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos was the clarity of the criterion and the adherence of OTs to criterion-referenced thinking.

Our findings are in line with recent research on the clinical utility of the PRPP-Assessment that found that it can be difficult for OTs to consciously free their thinking from biomedical influences and focus on the occupational performance criterion (Burrows et al., Citation2021). However, to our knowledge, there is no literature on standardization or directions on how to formulate the criterion, let alone how to formulate this when using video material without direct contact with the client. Therefore, it could be beneficial not only to study further the concurrent validity between live and video observations using PRPP-Assessment, but also to focus on directions for formulating the criterion when using parent-provided videos.

A strength of this study was the use of the ADR, combining action research (Baskerville, Citation1999; De Villiers, Citation2005; DePoy & Gitlin, Citation2019; Dick, Citation2000) with features of feasibility research (Bowen et al., Citation2009; Orsmond & Cohn, Citation2015) and development research (Reeves, Citation2000; van den Akker, Citation1999, Citation2002). This led to the combination of practical and scientific contributions while using a methodically sound approach. Using the ADR (Collatto et al., Citation2018) enabled focusing on implementation in the real context, alongside focusing on generalizable lessons. Using ADR led to a large amount of qualitative data that were collected through five cycles, and incorporated lessons learned through the psychometric studies (Lindenschot et al., Citation2022) that were simultaneously conducted.

Another strength was that the kept log enabled the right timing of cycles, which turned out to be crucial. Not only was the log necessary to monitor saturation to move on to the next cycle, but it was used to monitor if enough experience was gained to start data collection.

A last strength was that different methods to collect data and several stakeholders—parents, OTs, and other professionals—were involved in the data collection. Although it was planned to involve the multidisciplinary team for children with mitochondrial disorders (physician, physical therapist, psychologist, etc.) in the value of the PRPP-Assessment for interdisciplinary care, the experience of PRPP-Assessment within this team was too little to perform in-depth data collection and analysis. However, other disciplines were interested in the videos and the outcome of the PRPP-Assessment as it informed them in terms of therapy goals—for example, the video on playing soccer informed the physical therapist, and the video on eating soup was helpful for the dietitian and speech therapists. Therefore, this study can be seen as a first step in promoting interdisciplinary goal-setting based on home observation of children with mitochondrial disorder. This could be addressed in future research.

A limitation was the difficult inclusion of children with a mitochondrial disorder. Due to the low prevalence of the disease, data were also collected in a rehabilitation center with children with the same symptoms for the cycles in which this was possible. In these cycles, the focus was more on the overall parent experience than the experience within the specific target group. This led to more transferrable results, and the results of this study could be seen as representative of the target group with mitochondrial disorder, but also transferrable to the target group of parents of children with a disability.

There are several implications for practice and education. Firstly, the developed manual gives directions for implementation of the PRPP-Assessment based on parent-provided videos in OT practice, especially for implementing it in interprofessional settings. This manual could be transferred to other assessments that use video-based observations or other target groups. It is recommended that in each setting were this manual is used, a new cycle of the ADR is conducted with a focus on evaluating the manual in that specific context. Secondly, the lessons learned should be implemented in PRPP courses and/or refresher training for PRPP-certified OTs who work with children. Lastly, breaking down the tasks on the level of behavior (stage 1) with respect to the criterion needs more attention in the Netherlands, and possibly worldwide. This is not only relevant for children, but other target groups where the focus is on behavior could benefit from the lessons learned—for instance, when assessing the behavior of people with chronic pain or chronic fatigue. Experience in task analysis of behavior with the PRPP-Assessment could increase the applicability of the PRPP-Assessment.

In conclusion, this ADR process led to several learned lessons that can be used to implement video-based observations and analysis, which can be of benefit for care at distance.

In Memoriam

Researcher Esther Steultjens contributed extensively during this action design research, but was no longer with us during writing down the report. Her input during the research was extremely valuable. There is nothing that disappears forever, if one keeps the memory.

Appendix_1.docx

Download MS Word (35.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the children, parents and professional that participated in this study. Also, we are grateful for the support given by the BScOT-students (Manon van Drueten, Sofie Eijkelkamp and Peter van Grinsven) who collected and analyzed data of the fifth cycle. Special thanks goes to Lieke Timmermans, who shared her expertise on the PRPP-Assessment during this research.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. It should be noted that all qualitative data are in Dutch.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marieke Lindenschot

Marieke Lindenschot currently works as head of the Occupational Therapy Bachelor of Science education and is obtaining a doctorate. She has worked as an occupational therapist with children and adults and has developed expertise on the impact of fatigue and cognitive impairments on everyday live.

Imelda J.M.de Groot

Imelda de Groot worked as a rehabilitation physician in several university hospitals. She is specialized in pediatric metabolic and neuromuscular disorders. She was leader of the pediatric neuromuscular center in Radboudumc and her research aims at improving care for rare diseases.

Maria W.G. Nijhuis-van der Sanden

Maria Nijhuis-van der Sanden worked as pediatric physical therapist during 40 years and became professor in allied health sciences in 2009. She published about 200 articles on personalized (pediatric) physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy.

Esther M.J. Steultjens

Esther Steultjens worked as an occupational therapist and researcher. She had a strong background in neuropsychology and was involved in occupational therapy and occupational science research and research considering the impact of cognitive impairments on daily life. She was an Associate Lector at the Research Group Neurorehabilitation and involved in Bachelor and Master education. She passed away in October 2021.

Maud J.L. Graff

Maud Graff is Professor in Occupational Therapy. She worked both as an occupational therapist and researcher with a background in health sciences in clinical practice of frail people with a combination of cognitive, and/or physical, sensory and social problems and their caregivers. Her research expertise is on developing, evaluating and implementing methodologically sound interventions for these frail people and their caregivers, to promote their self-direction, daily functioning and participation in meaningful activities and society.

Saskia Koene

Saskia Koene is a clinical geneticist in training at the Leiden University Medical Center. She received her PhD on a project entitled “Towards harmonization of outcome measures in children with mitochondrial disorders” at the Radboudumc in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

References

- Bailey, D. B., & Simeonsson, R. J. (1988). Investigation of use of goal attainment scaling to evaluate individual progress of clients with severe and profound mental retardation. Mental Retardation, 26(5), 289–295.

- Baskerville, R. L. (1999). Investigating information systems with action research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 2(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00219

- Boonzaaijer, M., van Dam, E., van Haastert, I. C., & Nuysink, J. (2017). Concurrent validity between live and home video observations using the Alberta Infant Motor Scale. Pediatric Physical Therapy: The Official Publication of the Section on Pediatrics of the American Physical Therapy Association, 29(2), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000363

- Bouwens, S. F. M. (2009). Ecological aspects of cognitive assessment. NeuroPsych Publishers. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20090429sb

- Bowen, D. J., Kreuter, M., Spring, B., Cofta-Woerpel, L., Linnan, L., Weiner, D., Bakken, S., Kaplan, C. P., Squiers, L., Fabrizio, C., & Fernandez, M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

- Burrows, W., Hocking, C., & Chapparo, C. (2021). Learning, translating, and applying the perceive, recall, plan, perform system of task analysis assessment to practice: Occupational therapists’ experiences. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 030802262110422. https://doi.org/10.1177/03080226211042264

- Chapparo, C. (2017). Perceive, recall, plan and perform (PRPP): Occupation-centred task analysis and intervention system. In S. Rodger & A. Kennedy-Behr (Eds.), Occupation-centred practice with children: A practical guide for occupational therapists. (pp. 189–208). John Wiley & Sons.

- Chapparo, C., & Ranka, J. (1996). The perceive, recall, plan, perform (PRPP) system of task analysis. The PRPP Research Training Manual. 2nd ed. (pp. 1–11). University of Sydney.

- Chapparo, C., & Ranka, J. (1997). The perceive, recall, plan and perform system of task analysis. In C. Chapparo & J. Ranka (Eds.), Occupational performance model (Australia): Monograph 1. (pp. 189–198). Total Print Control.

- Collatto, D. C., Dresch, A., Lacerda, D. P., & Bentz, I. G. (2018). Is action design research indeed necessary? Analysis and synergies between action research and design science research. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 31(3), 239–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-017-9424-9

- Curby, T. W., Johnson, P., Mashburn, A. J., & Carlis, L. (2016). Live versus video observations: Comparing the reliability and validity of two methods of assessing classroom quality. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(8), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282915627115

- Dassler, A., & Allen, P. J. (2014). Mitochondrial disease in children and adolescents. Pediatric Nursing, 40(3), 150–154.

- De Villiers, M. (2005). Three approaches as pillars for interpretive information systems research: Development research, action research and grounded theory. Proceedings of the 2005 Annual Research Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists (SAICSIT '05) on IT Research in Developing Countries (pp. 142–151). South African Institute for Computer Scientists and Information Technologists.

- DePoy, E., & Gitlin, L. N. (2019). Introduction to research e-book: Understanding and applying multiple strategies. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Dick, B. (2000). A beginner’s guide to action research. https://www.studymode.com/essays/a-Beginner%27s-Guide-To-Action-Research-883429.html

- Drueten, M. V., Eijkelkamp, S., & Grinsven, P. V. (2021). PRPP challenge accepted. HAN University of Applied Sciences.

- Houwink, A., Geerdink, Y. A., Steenbergen, B., Geurts, A. C., & Aarts, P. B. (2013). Assessment of upper‐limb capacity, performance, and developmental disregard in children with cerebral palsy: Validity and reliability of the revised Video‐Observation Aarts and Aarts module: Determine Developmental Disregard (VOAA‐DDD‐R). Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55(1), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04442.x

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Keller, J., Kafkes, A., & Kielhofner, G. (2005). Psychometric characteristics of the Child Occupational Self Assessment (COSA), part one: An initial examination of psychometric properties. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12(3), 118–127.

- Koene, S., Wortmann, S. B., de Vries, M. C., Jonckheere, A. I., Morava, E., de Groot, I. J. M., & Smeitink, J. A. M. (2013). Developing outcome measures for pediatric mitochondrial disorders: Which complaints and limitations are most burdensome to patients and their parents? Mitochondrion, 13(1), 15–24. https:// https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2012.11.002

- Lindenschot, M., de Groot, I. J. M., Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M. W. G., Steultjens, E. M. J., Koene, S., & Graff, M. J. L. (2021). Insight into performance of daily activities in real life of a child with limited physical, cognitive and communication abilities: A case report. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2021.1941495

- Lindenschot, M., Koene, S., Nott, M. T., Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden, M. W., de Groot, I. J., Steultjens, E. M., & Graff, M. J. (2022). The reliability and validity of the perceive, recall, plan and perform assessment in children with a mitochondrial disorder.

- Linton, S. (1998). Disability studies/not disability studies. In Claiming disability. (pp. 132–156). New York University Press.

- Lowe, S. (2010). [ Cognitive strategies and school participation for students with learning difficulties. Doctoral ]. [Thesis]. University of Sydney.

- McLaren, C., & Rodger, S. (2003). Goal attainment scaling: Clinical implications for paediatric occupational therapy practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 50(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.2003.00379.x

- Mills, C., Chapparo, C., & Hinitt, J. (2016). The impact of an in-class sensory activity schedule on task performance of children with autism and intellectual disability: A pilot study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(9), 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022616639989

- Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Stratford, P. W., Knol, D. L., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. W. (2009). COSMIN checklist manual. https://faculty.ksu.edu.sa/sites/default/files/cosmin_checklist_manual_v9.pdf

- Nott, M. T., Chapparo, C., & Heard, R. (2009). Reliability of the perceive, recall, plan and perform system of task analysis: A criterion-referenced assessment. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56(5), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2008.00763.x

- Nott, M. T., Hons, B. O., Chapparo, C., & Nott, M. (2006). Measuring task embedded information processing capacity during occupational performance: An application of Rasch measurement. In Proceedings of the Australian Consortium for Social and Political Research, Social Science Methodology Conference. University of Sydney.

- Orsmond, G. I., & Cohn, E. S. (2015). The distinctive features of a feasibility study: Objectives and guiding questions. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 35(3), 169–177.

- Reeves, T. C. (2000). Socially responsible educational technology research. Educational Technology, 40(6), 19–28.

- Schmuckler, M. A. (2001). What is ecological validity? A dimensional analysis. Infancy: The Official Journal of the International Society on Infant Studies, 2(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327078IN0204_02

- Simeonsson, R. J., Huntington, G. S., & Short, R. J. (1982). Individual differences and goals: An approach to the evaluation of child progress. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 1(4), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112148200100411

- Sparrman, A. (2005). Video recording as interaction: Participant observation of children's everyday life. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(3), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088705qp041oa

- Stafford, A., Laybourn, A., Hill, M., & Walker, M. (2003). ‘ Having a say’: Children and young people talk about consultation. Children & Society, 17(5), 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/chi.758

- Stewart, K. S. (2010). [Information processing strategy application: A longitudinal study of typically developing preschool and school aged children]. [Doctoral Thesis]. University of Sydney.

- van den Akker, J. (1999). Principles and methods of development research. In Design approaches and tools in education and training. (pp. 1–14). Springer.

- van den Akker, J. (2002). The added value of development research for educational development in developing countries. In K. Osaki, W. Ottevanger, C. Uiso, & J. J. H. van den Akker (Eds.), Science education research and teacher education in Tanzania. (pp. 51–67). Vrije Universiteit.

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053