Abstract

Aim

To investigate strategies used by professionals in pediatric rehabilitation to engage children in every step of the intervention process, including assessment, goal setting, planning and implementation of the intervention, and results evaluation.

Methods

A scoping literature review was conducted, and seven databases were searched, including CINAHL and MEDLINE, ProQuest Central, PsycINFO, Social Science Premium Collection, PubMed, and Web of Science. A citation search of included articles was completed. Predetermined criteria, quality standards, and PIO framework guided the selection process. Results were presented in relation to Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the contextual model of therapeutic change.

Results

In total, 20 studies were included in the review. Pediatric professionals reported that therapeutic use of self and their own engagement in the intervention facilitated the establishment of a supportive relationship. Providing clear explanations about their role and therapy rationale developed positive expectations. By making the child feel successful within-session and outside-session activities, professionals enhanced child mastery. Professionals’ strategies were abstractly described.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to investigate strategies that are effective in the different steps of the intervention. More observational, longitudinal studies are required to capture fluctuations in in-session engagement.

Child engagement in the intervention process is gaining more and more momentum in the literature, as important for the outcome of pediatric rehabilitation and healthcare (D’Arrigo et al., Citation2017; Melvin et al., Citation2020). In the pediatric rehabilitation literature, engagement is defined as “a multifaceted state of motivational commitment or investment in the client role over the treatment process” (King et al., Citation2014, p. 4). The term “client,” according to King et al.’s definition, refers to parents or caregivers and children.

Engagement fosters optimal therapeutic outcomes and enhances children’s autonomy and self-reliance (Bright et al., Citation2015; D’Arrigo et al., Citation2017). Scientific evidence has suggested that the adoption of engagement-promoting strategies might increase adherence to the intervention (Bolster et al., Citation2021; Elbers et al., Citation2021). A recent study that involved speech and language pathologists concluded that open communication enhanced family engagement in the intervention (Melvin et al., Citation2021b). Nevertheless, professionals’ strategies aimed to develop such a relationship and to build skills in children in each step of the intervention have not been sufficiently described.

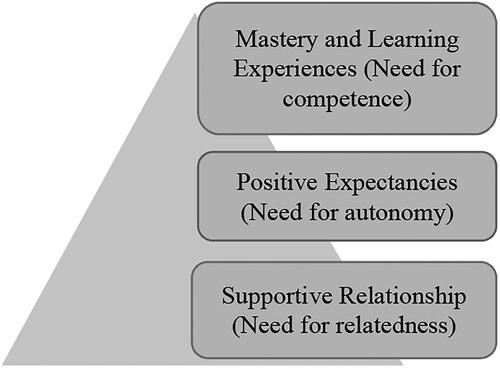

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, Citation2002) in combination with the contextual model of therapeutic change (King, Citation2017) may provide a structure for studying professionals’ child engagement strategies. According to SDT, strategies for satisfying psychological needs for relatedness (connection to others), autonomy (sense of control), and competence (self-efficacy) can increase engagement in therapy (Deci & Ryan, Citation2002). According to the contextual model of therapeutic change (King, Citation2017), engagement can be enhanced by a supportive relationship. Positive expectancies in therapy are generated by such a relationship, creating an impetus for change. Providing opportunities and skills might lead to mastery and learning experiences (King, Citation2017). was created, based on those two models, to illustrate the relationship between the concepts.

Figure 1. A representation of the relationship between self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the contextual model of therapeutic change. Note. The Need for relatedness, the Need for autonomy and the Need for competence belong to SDT. Supportive Relationship, Positive Expectancies and Mastery and Learning Experiences belong to the contextual model of therapeutic change.

A supportive relationship within pediatric rehabilitation is defined as a collaborative partnership that motivates and engages the client (Wampold, Citation2001). Strategies reported in the literature to enhance a supportive relationship usually include empathizing, encouraging, and guiding (Dunst, Citation2002; Rodger, Citation2002). Therapy expectations are defined as “anticipatory beliefs that clients bring to treatment” (Nock & Kazdin, Citation2001, p. 155). According to a literature review, conducted by Smart et al. (Citation2017), professionals can generate positive expectations in therapy by assessing and validating clients’ expectations, explaining therapy rationale and problem, negotiating, and collaborating with clients. Finally, mastery is used to describe self-efficacy which can be achieved through exposure to new learning when engaging in therapeutic tasks (King, Citation2017).

The initial steps of the intervention, as defined by Björck-Åkesson et al. (Citation2000), include assessment which involves the identification of challenges/problems, finding explanations for these problems, as well as goal setting which refers to problem prioritization based on child preferences and the articulation of realistic goals. Explanations and conclusions drawn by assessment and goal setting are used to plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention (Björck-Åkesson et al., Citation2000). Children and professionals collaborate to design an effective intervention that provides solutions. During implementation, they simultaneously evaluate its effectiveness and make the necessary adaptations when needed (King et al., Citation2020).

Children’s most important environment is family and parents’ support might enhance children’s autonomy. Thus, in family-centered care core aspects are professional-family collaboration to promote child engagement in the intervention (An et al., Citation2016). The child, other family members, and professionals contribute equally to the intervention, with child engagement as a core component (Coyne et al., Citation2016). In family-centered approaches, capacity-building strategies could be applied by professionals through their help-giving behaviors and routines, and they can assist family members and the child in becoming autonomous problem solvers (Trivette et al., Citation2010).

When it comes to clinical practice children and their families sometimes appear unaware of the assessment that occurred or how the assessment is related to the intervention chosen (King et al., Citation2020). Because of this unawareness, the process is deprived of its educational value for children and their families (King et al., Citation2020). Child engagement in pediatric rehabilitation has been taken for granted and therefore, it is not adequately researched (Melvin et al., Citation2021a). The role of professionals in engaging the child requires further investigation by providing explicit descriptions of strategies used in everyday practice (Wright et al., Citation2014).

The aim of this scoping review was to identify strategies used by pediatric rehabilitation professionals, for example, physical and occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, nurses, and psychologists, to engage the child in a learning process in all steps of the intervention. The scoping review was guided by the following research questions:

What strategies do professionals in pediatric rehabilitation use to engage children in the assessment process and goal setting?

What strategies do professionals in pediatric rehabilitation use to engage children in planning and implementation of the intervention and results evaluation?

Methods

The scoping review was undertaken based on the methodological recommendations proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). The further refinement of these recommendations proposed by Levac et al. (Citation2010) was also considered.

Selection Criteria

Predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria guided the selection of articles. The selection criteria were formed based on a Participant, Intervention, Outcome (PIO) framework (see ). Considering that pediatric rehabilitation services are provided to children, adolescents, youth, and sometimes young adults, articles focusing on engagement strategies in the age range (1–21) were included. The term “children” was used to describe the population of interest, which was children, adolescents, and youth with various disabilities, who receive pediatric rehabilitation services. Studies including interventions provided to infants (<1 year old) were excluded, because professionals tend to primarily rely on parents when implementing such interventions. Articles that explicitly investigated child “participation,” “involvement,” or “engagement” in the intervention were included in the review. According to the Family of Participation-Related Constructs (fPRC) framework (Imms et al., Citation2017) the term “participation” was used as a superordinate construct for the dimensions of attendance (being there) and involvement (being engaged while attending). Primarily studies that focused on engagement or involvement while attending the intervention process were included in the review.

Table 1. PIO framework applied to aim and research questions.

Search Strategy

The process of searching was performed twice, the first search on February 3–28, 2022, and the second search on November 5–26, 2022. The procedure to identify articles for inclusion was conducted systematically by using seven databases. CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest Central, PsycINFO, Social Science Premium Collection, PubMed, and Web of Science databases were searched for relevant articles. Search strings included free-text keywords. Identical keywords were used in every database at both times, and they were organized in blocks, the combination of which formed the final search strings. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were utilized for combining the search strings and structuring the delimitation in each database. Three filters were applied to obtain the desirable results, (1) language (English), (2) publication date (2012–2022), (3) peer-reviewed. Only articles published in the previous decade were included to provide the latest information considering the topic under investigation. Reference lists of articles included were scrutinized to ensure that all relevant literature was examined.

The search terms have been informed by the current literature (Curtis et al., Citation2022) and the search strategy was tested five times by the first two authors before implementing it. In both searches, these keywords were used in every database: (“health and care professionals” OR “therapists” OR “rehabilitation professionals” OR “pediatric professionals”) AND (“intervention process” OR “assessment process” OR “goal setting” OR “results evaluation”) AND (“children” OR “adolescents” OR “teenagers”). In the second search, the combination of keywords was partly changed to verify that the first search identified every relevant article. Thus, in the second search, the search strings did not include the terms “children” OR “adolescents” OR “teenagers,” as pediatric rehabilitation services are sometimes provided to young adults. In addition, in the second search, the terms “participation” OR “engagement” OR “involvement,” were added to ensure the inclusion of articles that explicitly described engagement in the intervention. These terms were aligned with King et al.’s engagement definition (King et al., Citation2014) and the definition of the participation dimension involvement provided in the fPRC framework (Imms et al., Citation2017).

Selection Process and Quality Assessment

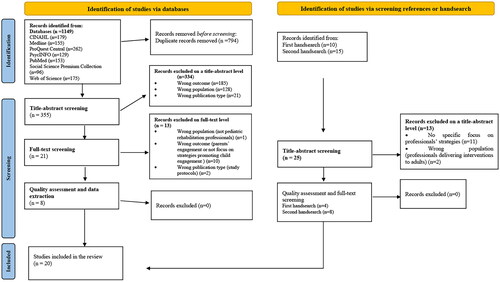

The total number of articles retrieved from the seven databases, after having completed the two searches, and through handsearching, performed after the first and second search, was 1174, which were imported to EndNote. via this process, 794 duplicates were identified. The remaining articles (380) were screened using Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). The first two authors conducted the processes of screening and selection of studies. Disagreements between the reviewers regarding the inclusion of the studies were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus. The screening process was conducted in two stages for each search. First, the articles were screened on a title and abstract level and second, a full-text screening procedure was implemented. The exclusion criteria were wrong publication type (literature reviews or reports), outcome (not focusing on the child engagement in the intervention), or population (not focusing on pediatric rehabilitation professionals). In total, of the 380 articles, 347 were excluded based on the title abstract. Of 33 remaining studies, 13 were excluded based on full-text screening, resulting in 20 articles. The selection process is presented in .

The quality of the 20 articles was assessed by the first author using two assessments. Studies with qualitative research designs were assessed by the COREQ-32 checklist (Tong et al., Citation2007) and studies with mixed methods designs were assessed by the STROBE checklist (Von Elm et al., Citation2007) for cross-sectional studies. Four of the 20 studies were low-quality (D’Arrigo et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Schwellnus et al., Citation2020; Zeng et al., Citation2021). Considering that less emphasis is given to quality assessment in scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005) and that a limited number of studies were identified via the databases and handsearch, low-quality studies were included in the review. However, these studies were not used in the discussion, their results mirrored other included studies with higher quality.

Data Extraction

An extraction process of the 20 final studies was performed by the first author. A data extraction protocol in Excel format was created based on the aim and the research questions. Authors’ names, publication dates, articles’ titles, journals, and countries were included in the protocol. The study aims, research design, sampling strategy, and data collection were also extracted. In addition, the strategies used by professionals to engage children in the different steps of the intervention process were extracted.

Data Analysis

A deductive approach was used to analyze the results. Child engagement strategies identified in the text were first categorized into the steps of the intervention process (assessment, goal setting, planning and implementation of the intervention, and results evaluation). As a second step, they were linked to the tenets of SDT and the contextual model of therapeutic change. Therefore, professionals’ strategies were divided into those promoting a supportive relationship (need for relatedness), positive expectancies (need for autonomy), and mastery and learning experiences (need for competence). The process of data analysis was conducted by the first and the second author, while the third author verified the data analysis and provided feedback, which was incorporated into the process. All strategies reported in the studies could be linked to the frameworks used.

Results

Characteristics of Included Articles

The publication date of the articles selected ranged between 2017 and 2022. The citation process was simplified by assigning an identification number (IN) to each article. Characteristics of the articles included are presented in . Out of 20 studies, eight were conducted in Canada (5,6,7,8,9,14,15,16), three in Australia (2,3,4), three in Sweden (11,17,19), two in Ireland (12,13), one in Austria (1), one in China (20), one in Finland (10) and one in the Netherlands (18).

Table 2. Overview of general characteristics of included articles.

Regarding the design adopted in each study, 16 out of 20 studies were qualitative (2,3,4,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20) and four had a mixed method design (1,5,7,8). Qualitative studies applied various data collection methods, including semi-structured individual interviews with rehabilitation professionals (2,3,4,13,15) and interviews with parents/caregivers (11). Ten out of 16 qualitative studies included individual or focus group interviews with children and/or youth (2,6,9,10,12,14,16,17,18,19). One article included in-session observations of children, professionals, and caregivers (3), one of youth and professionals (16), and one of children and professionals (18).

Children who received therapeutic interventions had various diagnoses and differed in age. Children were diagnosed with intellectual disabilities (11,17), physical disabilities (10,9,11,16,17), learning difficulties (10), Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (3,5,9,17,20), Cerebral Palsy (CP) (5,6,7,8,9,14), developmental coordination disorder (DCD) (13), attention deficit disorder (ADHD) (3), acquired brain injuries (ABI) (3,4), speech disorder (3,5,7,9) not specified diagnosis (1,2,12,15,18,19). Four studies referred to interventions delivered to preschool children (3,5,9,20), 14 studies to school-aged children (1,3,5,6,7,9,10,11,12,14,17,18,19,20), nine studies to youth (6,7,8,9,11,16,17,18,19), one study to young people (19), and four studies did not specify the ages of the children (2,4,13,15).

Child Engagement Strategies Used by Professionals

The types of strategies used are presented in relation to the step of the intervention process and the frameworks in . In addition, Appendix A was created that lists professionals’ strategies, by providing point form descriptions. Strategies categorized as belonging to the first two steps of the intervention, assessment, and goal setting, and the last two steps of the process, implementation of the intervention and results evaluation, are further analyzed in the two sections below.

Table 3. Overview of the results.

Assessment Process and Goal Setting

Supportive Relationship (Need for Relatedness)

Professionals collaborated with caregivers and other professionals to collect information, adapt assessment, and goal setting based on children’s needs (4,12,13,14). Professionals invested time to empathically listen to children (3,9,10,19) and understand what is important to them (6,7,9,15,16). Afterward, professionals responded either verbally by using simple vocabulary (4,19) and repetition (20) by fluctuating simultaneously the tone, the pace, and the volume of voice (2,3) or physically by “being on the child’s level” (17), or by utilizing the appropriate body posture such as crouching or gestures, smile or high five (3). This reciprocal interaction was described as a prolonged “dance” (2,3).

The importance of adopting an encouraging attitude was highlighted (2,10,11,18,19,20). For encouraging the child to speak about their needs, therapists sat against a visually calm background, while the child sat directly across them (18). Play and selection of appealing and enjoyable activities encouraged child engagement in assessment and goal setting (2,3,5,7,13). Professionals’ high engagement in the process enhanced children’s engagement in therapy, as well (2,5,6,8,12,16). Professionals made the child feel comfortable by sharing their individual experiences, or by letting them explore the therapeutic environment, by touching therapists’ things, such as professionals’ pens or pockets (5,6,8).

Children were provided with adequate time to articulate goals (4,19). The role of the therapist was described as “mediator,” “orchestrator” and “resource person” (5,8,11,12,15). The need for parents’ involvement was more intense in younger children and/or in children with cognitive impairments (4).

Positive Expectancies (Need for Autonomy)

Professionals reported the significance of discovering children’s and parents’ expectations regarding therapy (5). Professionals used skillful questioning to reveal therapeutic expectations and to help the child feel in control (3).

Giving explanations about the professionals’ role, the nature, and the purpose of the intervention goals, built clear expectations (2,5,7,12,14,19). When therapeutic goals were connected to children’s future, engagement was promoted (5,6,7,8,11). Professionals initiated a conversation with the child regarding the identification of problems to work with during therapy (18). Professionals mentioned that they “interviewed” the child about their daily performance in important activities.

Several self-assessment and goal-setting tools were used by professionals to ensure collaboration with the child, such as the Perceived Self-Efficacy and Goal Setting System (PEGS) or the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) (1,4,12,14,18). Professionals introduced the instruments by providing verbal or visual explanations to the child (12,18).

Alternative communication was used to facilitate engagement in assessment and goal setting, such as pictures and drawings (1,4,17), or technology such as iPad (7) and walkie-talkie (19). Children participated in designing personas for a game aimed to enhance their engagement in the intervention (17).

Mastery and learning experiences (need for competence)

Focusing on a maximum of five goals each time assisted the child in feeling competent (4,5,6,13,14,19). The importance of “rest breaks,” “baby steps” and “celebrating the small winnings” were stressed (7,9,16).

Planning and Implementation of the Intervention and Results Evaluation

Supportive Relationship (Need for Relatedness)

Session activities were chosen based on child interests, including music, games, challenge, discovery, or exploration, aimed to build rapport (2,3).

Therapists provided positive feedback and they stressed children’s strengths when implementing the intervention (3,10). Through body language or verbal communication, the child felt encouraged to perform tasks (2,3).

Positive Expectancies (Need for Autonomy)

Professionals informed children about the anticipated in-session activities and the reason they were performed. They used verbal explanations and visual schedules (2,3). They also offered choices to children to provide input on session agendas and to determine therapeutic activities that increased their sense of control (7). Professionals let the child guide the activity (3). Professionals also presented a predetermined group of activities to children who were allowed to choose which one to perform (12).

Mastery and Learning Experiences (Need for Competence)

Therapists made physical and cognitive adjustments when needed to facilitate engagement in therapeutic tasks and prevent failure (3,7). Sometimes, professionals performed the activity in cooperation with the child (3). The order of the tasks was changed, and rest breaks were provided to children when performing a series of re-assessment of physical activity to enhance mastery (7). By suggesting and planning real-life activities, such as riding a bike (5), or downhill skiing (10), and by organizing group projects, like leading a trip to the subway (16), professionals coached children to train skills outside the sessions.

Discussion

According to the results of the review, professionals’ therapeutic use of self and their engagement in the intervention created a supportive relationship. Clear explanations considering therapy generated expectations. Professionals enhanced mastery in children by completing both in-session and outside-session activities.

The findings of the review could benefit both experienced and novice pediatric professionals. Experienced professionals tend to use engagement strategies without being consciously aware of them (Kinsella, Citation2018). Conscious awareness may increase the use of the most effective engagement strategies even further. By providing a theoretical tool, experienced professionals may become more efficient in their everyday practice. Explicit descriptions of engagement principles may assist novice professionals in building skills in children and in understanding the relational aspects of the intervention (Klatte et al., Citation2019). The discussion section is structured according to the tenets of SDT and the contextual model of therapeutic change (see ).

Supportive Relationship for Meeting the Need for Relatedness

The results of the present review confirmed previous literature findings that professionals can create a safe environment for the child by deliberately using interpersonal skills. This process has been defined in the literature as “therapeutic use of self’ and it has been used to describe therapists” conscious efforts to facilitate interpersonal interactions with clients (Cole & McLean, Citation2003; Punwar & Peloquin, Citation2000). The intentional relationship model (IRM), developed by Taylor (Citation2008), addressed six interpersonal skills therapists use as strategies including advocating, collaborating, empathizing, encouraging, instructing, and problem-solving (Taylor, Citation2008). The use of similar strategies was described in the articles included in this review, especially during the initial steps of the intervention (see ).

The results of the present review were in line with previous findings and indicated that child engagement in therapy is dependent on professionals’ own level of engagement. According to the findings of a recent critical review, mutual engagement was considered a prerequisite for developing a supportive relationship in therapy (King, Citation2021). Professionals’ engagement in communication with clients connotes an appreciation and interest in them, facilitating their optimal interaction (McKenna et al., Citation2020).

Despite acknowledging the value of a supportive relationship, the implementation of relational strategies is abstractly described in the current literature. In previous studies, professionals characterized interactions in therapy as interpersonally challenging and therapeutic use of self as an elusive term (Solman & Clouston, Citation2016). In pediatric rehabilitation, the establishment of a meaningful relationship is more complex, as both parents and caregivers are also active participants in therapy (King et al., Citation2017). The findings of this scoping review indicate that professionals use relational strategies mainly at the initial steps of the intervention. More concrete descriptions of relational strategies are needed, involving all steps of the intervention process.

Positive Expectancies for Meeting the Need for Autonomy

Positive expectancies in therapy might be generated by a supportive relationship, leading to increased autonomy and engagement (King, Citation2017). Validating children’s initial expectations, explaining treatment rationales, and sharing control of treatment role decisions, might enhance affective, cognitive, and behavioral components of child engagement (King et al., Citation2014).

Creating positive expectancies in therapy is considered of pivotal importance when delivering therapeutic interventions (Smart et al., Citation2019). This is in line with the findings of this review, indicating that professionals used a wide range of strategies aimed to facilitate child autonomy, including explaining the therapy rationale. Negotiating with children and their families about expected therapy processes and outcomes enhances families’ sense of control, according to Smart et al. (Citation2019). It also ensures that families’ expectations are congruent with professionals’ orientations of the intervention (Frankl et al., Citation2014).

Nevertheless, the articles included in the review described the use of expectations strategies mostly in the goal-setting part of the processes (see ). Only one article included in this review explicitly described how the therapist supported the child in identifying what problem to work with at the beginning of the assessment (Verkerk et al., Citation2023). When children are unaware of the problem and the therapy rationale, they appear less engaged and the possibilities of following the intervention plan are reduced (Coyne et al., Citation2016).

For increasing child autonomy, the results of the studies reviewed indicate the importance of assistive technology and standardized tools. Alternative and augmentative communication were used to engage children in the process. COPM (Law et al., Citation1990) and PEGS (Missiuna & Pollock, Citation2000) were used, aimed to engage the child in the assessment and goal setting. However, older and extrovert children are more capable of using self-reported tools than younger, introverted ones in goal-setting processes (Greco et al., Citation2017). Children of younger age and lower cognitive levels were mostly dependent on their parents’ assistance for expressing their needs, according to a recent study (Pritchard-Wiart & Phelan, Citation2018). This is consistent with the findings of the present review.

Finally, child engagement and therapeutic expectancies are constructs changing over time. Professionals need to evaluate child expectancies when children appear either less engaged or highly engaged to ensure that therapy remains meaningful (Smart et al., Citation2019). Further research is required regarding professionals’ strategies to generate positive expectancies and autonomy in different steps of the intervention and children of younger ages.

Mastery and Learning Experiences for Meeting the Need for Competence

Experiencing mastery or competence when performing a therapeutic task can increase child engagement in therapy (Poulsen et al., Citation2006). Similar to previous studies, this review identified strategies used by professionals to enhance child engagement in goal setting. Child-driven goal setting could inspire engagement and create a sense of ownership of the process of learning (Cermak & Bissell, Citation2014; McBryde & Ziviani, Citation2019). Children are required to complete therapeutic activities that include the “just right challenge” to master new skills. Involvement in challenging tasks in therapy leads to optimal therapeutic outcomes (Miller et al., Citation2015).

Despite the significance of the use of competence-supportive strategies within the entire intervention process (Trivette et al., Citation2010), capacity-building or competence strategies have mostly been linked to goal-setting processes (Curtis et al., Citation2022). This is in line with the findings of this review (see ). Out of the 20 studies reviewed, only one case study reported a strategy used by a physiotherapist to promote competence in assessment and re-assessment (King et al., Citation2022). According to King et al. (Citation2020), when an opportunity is provided to children to critically reflect on their everyday problems and abilities, which usually takes place during assessment and re-assessment, self-efficacy is enhanced.

Learning experiences in therapy might lead to skills generalization (Graham et al., Citation2013). Outside-of-session successes are considered crucial regarding client change (Armitage et al., Citation2017). According to previous findings, to enhance client change, pediatric professionals coach children and their families to self-regulate their goals, plan, and implement a therapeutic plan based on their needs. Coaching has been perceived as a promising intervention and it has received a “yellow light” designation, which means that it can be effective, but more research is required (Kessler & Graham, Citation2015; Novak & Honan, Citation2019). The results of the present review indicate that professionals use several real-world activities aimed at achieving client change. However, strategies used for outside-of-therapy activities were seldom described. Further research is required about competence strategies, especially in outside-of-session activities when the therapist is not present.

Limitations

Several methodological limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. Two existing tools (COREQ-32 and STROBE checklist) were used to assess the quality of the studies included, increasing the reliability of the results. Quality assessment was conducted by one researcher. Although several studies were not of high quality, they were included in the review. Predefined quality inclusion and exclusion criteria might have led to the exclusion of valuable studies. Only eight out of 20 studies were found via searching through the databases by using keywords, although the search strategy had been tested. This may indicate that strategies used by professionals are abstractly described in the literature. For analyzing the results, SDT and the contextual model of therapeutic change were used. Those theories focus on professionals’ role in enhancing child engagement, without considering intervention characteristics. Future studies should focus on how intervention characteristics (e.g. therapeutic context) influence professionals’ strategies.

The studies included did not differentiate professionals’ strategies in accordance with the child’s age, type of disability, or step of intervention. Although different strategies are required when planning and implementing interventions and evaluating the results, the articles included did not allow this classification. No information was provided about the conditions of therapy, including the frequency and duration of the meetings with the professionals. Almost half of the studies referred to strategies used by professionals to engage the child in goal setting (see ). Only three studies used in-session observations as a method of data collection and only three articles involved preschool children in data collection (see ). The present scoping review, despite the limitations, may assist in ensuring consistent support regarding child engagement across the service delivery continuum.

Conclusion

The results of this scoping review identified professionals’ strategies to engage the child in the intervention based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the contextual model of therapeutic change. The studies included in this review indicated that professionals created a supportive relationship by using relational strategies, mainly in the initial steps of the intervention process. Children’s autonomy was enhanced by building positive expectations in therapy, which was primarily achieved in goal setting. Professionals enhanced mastery in children by completing both in-session and outside-session activities when implementing the method. More studies that focus on examining the use of relational, autonomy, and competence-building strategies in every step of the intervention process are needed. Further research is required regarding enhancing children’s competence in the assessment process and when implementing interventions to reach the goal when professionals are not present. To understand how children’s engagement in the intervention can be enhanced, interactions between professionals, parents, and children in different age groups, in several types of therapy, and in various therapy contexts should be observed.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marianna Antoniadou

Marianna Antoniadou is an occupational therapist with a master’s degree in health science, who currently is a doctoral student at the department of Medicine, Health, and Caring Sciences at Linköping University, in Sweden. Her research focuses on motivation and engagement strategies.

Mats Granlund

Mats Granlund is a professor of Disability Research and Psychology. He has long research experience in the field of participation and pediatric rehabilitation interventions.

Anna Karin Andersson

Anna Karin Andersson is a physical therapist with a PhD in Care Sciences at the School of Health and Welfare at Mälardalen University, Sweden. Her research focuses on children with disabilities, participation, and physical activity.

References

- An, M., Palisano, R. J., Dunst, C. J., Chiarello, L. A., Yi, C. H., & Gracely, E. J. (2016). Strategies to promote family–professional collaboration: Two case reports. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(18), 1844–1858. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1107763

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Armitage, S., Swallo, V., & Kolehmainen, N. (2017). Ingredients and change processes in occupational therapy for children: A grounded theory study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24(3), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2016.1201141

- Björck-Åkesson, E., Granlund, M., & Simeonsson, R. (2000). Assessment philosophies and practices in Sweden. In Interdisciplinary clinical assessment of young children with developmental disabilities. Paul H. Brookes.

- Bolster, E. A. M., Gessel, C. v., Welten, M., Hermsen, S., Lugt, R. v d., Kotte, E., Essen, A. v., & Bloemen, M. A. T. (2021). Using a co-design approach to create tools to facilitate physical activity in children with physical disabilities. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 2, 707612. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2021.707612

- Bright, F. A. S., Kayes, N. M., Worrall, L., & McPherson, K. M. (2015). A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(8), 643–654. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.933899

- Cermak, S. A., & Bissell, J. (2014). Content and construct validity of here’s how I write (HHIW): A child’s self-assessment and goal setting tool. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(3), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.010637

- Cole, M. B., & McLean, V. (2003). Therapeutic relationships re-defined. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 19(2), 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1300/J004v19n02_03

- Costa, U. M., Brauchle, G., & Kennedy-Behr, A. (2017). Collaborative goal setting with and for children as part of therapeutic intervention. Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(16), 1589–1600. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1202334

- Coyne, I., Hallström, I., & Söderbäck, M. (2016). Reframing the focus from a family-centred to a child-centred care approach for children’s healthcare. Journal of Child Health Care, 20(4), 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493516642744

- Curtis, D. J., Weber, L., Smidt, K. B., & Nørgaard, B. (2022). Do we listen to children’s voices in physical and occupational therapy? A scoping review. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 42(3), 275–296. In Taylor and Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2021.2009616

- D’Arrigo, R. G., Copley, J. A., Poulsen, A. A., & Ziviani, J. (2020a). The engaged child in occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 87(2), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417420905708

- D’Arrigo, R. G., Copley, J. A., Poulsen, A. A., & Ziviani, J. (2020b). Strategies occupational therapists use to engage children and parents in therapy sessions. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(6), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12670

- D’Arrigo, R., Ziviani, J., Poulsen, A. A., Copley, J., & King, G. (2017). Child and parent engagement in therapy: What is the key? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(4), 340–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12279

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self determination theory. University of Rochester Press.

- Dunst, C. J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. The Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669020360030401

- Elbers, S., Gessel, C. v., Renes, R. J., Lugt, R. v d., Wittink, H., & Hermsen, S. (2021). Innovation in pain rehabilitation using co-design methods during the development of a relapse prevention intervention: Case study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e18462. https://doi.org/10.2196/18462

- Frankl, M., Philips, B., & Wennberg, P. (2014). Psychotherapy role expectations and experiences - Discrepancy and therapeutic alliance among patients with substance use disorders. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 87(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12021

- Graham, S., Harris., & K. R., McKeown. (2013). The writing of students with learning disabilities, meta-analysis of self-regulated strategy development writing intervention studies, and future directions. In Handbook of learning disabilities (pp. 405–438). Guilford Press.

- Greco, V., Lambert, H. C., & Park, M. (2017). Being visible: PhotoVoice as assessment for children in a school-based psychiatric setting. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24(3), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2016.1234642

- Imms, C., Granlund, M., Wilson, P. H., Steenbergen, B., Rosenbaum, P. L., & Gordon, A. M. (2017). Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 59(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13237

- Jenkin, T., Anderson, V., D'Cruz, K., Collins, A., Muscara, F., Scheinberg, A., & Knight, S. (2022). Engaging children and adolescents with acquired brain injury and their families in goal setting: The clinician perspective. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(1), 104–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1801470

- Kessler, D., & Graham, F. (2015). The use of coaching in occupational therapy: An integrative review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(3), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12175

- King, G. (2017). The role of the therapist in therapeutic change: How knowledge from mental health can inform pediatric rehabilitation. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 37(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2016.1185508

- King, G. (2021). Central yet overlooked: Engaged and person-centred listening in rehabilitation and healthcare conversations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(24), 7664–7676. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1982026

- King, G., Chiarello, L. A., Ideishi, R., D'Arrigo, R., Smart, E., Ziviani, J., & Pinto, M. (2020). The nature, value, and experience of engagement in pediatric rehabilitation: Perspectives of youth, caregivers, and service providers. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 23(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518423.2019.1604580

- King, G., Chiarello, L. A., Ideishi, R., Ziviani, J., Phoenix, M., McLarnon, M. J. W., Pinto, M., Thompson, L., & Smart, E. (2021). The complexities and synergies of engagement: An ethnographic study of engagement in outpatient pediatric rehabilitation sessions. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(16), 2353–2365. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1700562

- King, G., Chiarello, L. A., Phoenix, M., D'Arrigo, R., & Pinto, M. (2022). Co-constructing engagement in pediatric rehabilitation: A multiple case study approach. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(16), 4429–4440. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1910353

- King, G., Chiarello, L. A., Thompson, L., McLarnon, M. J. W., Smart, E., Ziviani, J., & Pinto, M. (2017). Development of an observational measure of therapy engagement for pediatric rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1375031

- King, G., Currie, M., & Petersen, P. (2014). Review: Child and parent engagement in the mental health intervention process: A motivational framework. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19(1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12015

- King, G., Granlund, M., & Imms, C. (2020). Measuring participation as a means: Participation as a transactional system and a process. In C. Imms & D. Green (Eds.), Participation: Optimizing outcomes in childhood-onset neurodisability (pp. 143–160). Mac Keith Press. www.who.int/icf

- King, G., Schwellnus, H., Keenan, S., & Chiarello, L. A. (2018). Youth engagement in pediatric rehabilitation: Service providers’ perceptions in a real-time study of solution-focused coaching for participation goals. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 38(5), 527–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2017.1405864

- King, G., Schwellnus, H., Servais, M., & Baldwin, P. (2019). Solution-focused coaching in pediatric rehabilitation: Investigating transformative experiences and outcomes for families. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 39(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2017.1379457

- Kinnunen, A., Jeglinsky, I., Vänskä, N., Lehtonen, K., & Sipari, S. (2021). The importance of collaboration in pediatric rehabilitation for the construction of participation: The views of parents and professionals. Disabilities, 1(4), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1040032

- Kinsella, E. A. (2018). Embodied reasoning in professional practice. In Clinical and professional reasoning in occupational therapy (pp. 105–124). Wotlers Kluwer.

- Klatte, I. S., Harding, S., & Roulstone, S. (2019). Speech and language therapists’ views on parents’ engagement in Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT). International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(4), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12459

- Kronsell, L., Svedberg, P., Nygren, J., & Larsson, I. (2021). Parents’ perceptions of the value of children’s participation in pediatric rehabilitation services: A phenomenographic study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10948. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010948

- Law, M., Baptiste, S., McColl, M., Opzoomer, A., Polatajko, H., & Pollock, N. (1990). Canadian occupational performance measure: An outcome measure for occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 57(2), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749005700207

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS, 5(1), 69. http://www.cihr-irsc.ca https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- McBryde, C., & Ziviani, J. (2019). Special issue: Optimizing children’s participation for health and wellbeing II: Barriers and facilitators. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(4), 201–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619891867

- McKenna, L., Brown, T., & Oliaro, L. (2020). Listening in healthcare. In The handbook of listening (pp. 373–383). John Wiley & Sons.

- Melvin, K., Meyer, C., & Scarinci, N. (2020). What does “engagement” mean in early speech pathology intervention? A qualitative systematised review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(18), 2665–2678. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1563640

- Melvin, K., Meyer, C., & Scarinci, N. (2021a). Exploring the complexity of how families are engaged in early speech–language pathology intervention using video-reflexive ethnography. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 56(2), 360–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12609

- Melvin, K., Meyer, C., & Scarinci, N. (2021b). What does a family who is “engaged” in early intervention look like? Perspectives of Australian speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(3), 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1784279

- Miller, L., Ziviani, J., Ware, R. S., & Boyd, R. N. (2015). Mastery motivation: A way of understanding therapy outcomes for children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(16), 1439–1445. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.964375

- Missiuna, C., & Pollock, N. (2000). Perceived efficacy and goal setting in young children. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 67(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740006700303

- Nock, M. K., & Kazdin, A. E. (2001). Parent expectancies for child therapy: Assessment and relation to participation in treatment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 10(2), 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016699424731

- Novak, I., & Honan, I. (2019). Effectiveness of paediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: A systematic review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 66(3), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12573

- O’Connor, D., Lynch, H., & Boyle, B. (2021). A qualitative study of child participation in decision-making: Exploring rights-based approaches in pediatric occupational therapy. PLoS One, 16(12), e0260975. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260975

- O’Dea, Á. E., Coote, S., & Robinson, K. (2021). Occupational therapy practice with children with developmental coordination disorder: An online qualitative vignette survey. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(5), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022620944100

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan-A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Poulsen, A. A., Rodger, S., & Ziviani, J. M. (2006). Understanding children’s motivation from a self-determination theoretical perspective: Implications for practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 53(2), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00569.x

- Pritchard-Wiart, L., & Phelan, S. K. (2018). Goal setting in paediatric rehabilitation for children with motor disabilities: A scoping review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 32(7), 954–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518758484

- Pritchard, L., Phelan, S., McKillop, A., & Andersen, J. (2020). Child, parent, and clinician experiences with a child-driven goal setting approach in paediatric rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(7), 1042–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1788178

- Punwar, J., & Peloquin, M. (2000). Occupational therapy: Principles and practice. Lippincott.

- Rodger, S. ( 2002). Towards family-centred practice in paediatricoccupational therapy: A review of the literature on parent-therapistcollaboration. Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0045-0766.2001.00273.x

- Schwellnus, H., Seko, Y., King, G., Baldwin, P., & Servais, M. (2020). Solution-focused coaching in pediatric rehabilitation: Perceived therapist impact. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 40(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2019.1675846

- Smart, E., Aulakh, A., McDougall, C., Rigby, P., & King, G. (2017). Optimizing engagement in goal pursuit with youth with physical disabilities attending life skills and transition programs: An exploratory study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(20), 2029–2038. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1215558

- Smart, E., Nalder, E., Rigby, P., & King, G. (2019). Generating expectations: What pediatric rehabilitation can learn from mental health literature. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 39(2), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2018.1432007

- Solman, B., & Clouston, T. (2016). Occupational therapy and the therapeutic use of self. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(8), 514–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022616638675

- Taylor, R. R. (2008). The intentional relationship: Occupational therapy and use of self. F.A. Davis Co.

- Teleman, B., Svedberg, P., Larsson, I., Karlsson, C., & Nygren, J. M. (2022). A norm-creative method for co-constructing personas with children with disabilities: Multiphase design study. Journal of Participatory Medicine, 14(1), e29743. https://doi.org/10.2196/29743

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Trivette, C. M., Dunst, C. J., & Hamby, D. W. (2010). Influences of family-systems intervention practices on parent-child interactions and child development. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 30(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121410364250

- Verkerk, G., van der Molen-Meulmeester, L., van Hartingsveldt, M., & Alsem, M. (2023). Instructions for administering the Canadian occupational performance measure with children themselves. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 43(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2022.2079392

- Vinblad, E., Larsson, I., Lönn, M., Olsson, E., Nygren, J. M., & Svedberg, P. (2019). Development of a digital decision support tool to aid participation of children with disabilities in pediatric rehabilitation services: Explorative qualitative study. JMIR Formative Research, 3(4), e14493. https://doi.org/10.2196/14493

- Von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology, 18(6), 800–804. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654

- Wampold, B. E. (2001). The great psychotherapy debate models, methods, and findings. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wright, B. J., Galtieri, N. J., & Fell, M. (2014). Non-adherence to prescribed home rehabilitation exercises for musculoskeletal injuries: The role of the patient-practitioner relationship. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 46(2), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1241

- Zeng, X., Ma, B., Li, C., Zhang, L., Li, C., & Li, H. (2021). Therapists’ expressions of agreement in therapeutic conversations with Chinese children with ASD: Strategies, sequential positions and functions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 792167. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.792167

Appendix A: Strategies of Professionals in Relation to SDT and the Contextual Model of Therapeutic Change