Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

Historically, urban climate action plans have not focused on residents who are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change: neighborhoods of people of color and low-income communities, also known as frontline communities. I examined the climate action planning process for five U.S. cities that have recently updated their climate action plans to focus on equity: Austin (TX), Baltimore (MD), Cleveland (OH), Portland (OR), and Providence (RI). The goal of the analysis was to identify how planners and policymakers are making the climate action planning process more inclusive of marginalized groups and incorporating equity into the plan’s goals. I examined three aspects of climate equity: procedural, distributional, and recognition. Using content analysis of the plans and interviews with past and current sustainability directors in each of the cities and a small number of participants, I provide context for how the updated plans addressed the three aspects of equity. Further, I call into question how academics have defined procedural equity. The experiences of these five cities revealed that three actions essential to achieving authentic participation are antiracism training, comprehensive efforts to bring underrepresented groups to the table, and creating a planning process in which participants are valued. The bottom line in all three is that procedural equity is a trust-building process. Participants in these planning processes viewed acknowledging previous rounds of harm committed in frontline communities as a first step in prioritizing equity. Although distributional equity is defined through implementation, the plans of these five cities, to varying degrees, attempted to stipulate how equitable implementation of goals will be measured.

Takeaway for practice

Developing climate plans that emphasize equity requires a considerable upfront commitment to building authentic participation from frontline communities and ensuring that it is measured in implementation.

For the most part, equity has not been a priority of urban climate action planning in the United States. There are no clear guidelines as to what constitutes an equitable approach to urban climate action. Existing scholarship that has examined equity in planning has mostly focused on adaptation planning. This literature has identified necessary elements of achieving justice/equity in planning: participation (procedural equity); redistribution (distributional equity); and recognition. A smaller literature has examined equity in urban climate mitigation and mostly focuses on mentions of equity in climate action plans.

In this article I build on the literature on equity in urban climate action by examining the extent to which and how each of the three elements of justice was incorporated by cities that have recently updated their climate action plans with the intent of placing equity at the forefront. The cities are Austin (TX), Cleveland (OH), Portland (OR), and Providence (RI). Examining cities that claim to emphasize equity can offer insights for other cities. This analysis makes three contributions to the literature. First, it illustrates how each of the three elements of equity are incorporated into climate action planning processes and into the goals of the resulting plans. Second, it offers insights into how distributional equity can be measured in implementation of climate mitigation action steps. Third, it builds on the discussion in the literature on recognition justice, pointing out that its meaning is unclear.

I begin with a literature review that examines the three elements of climate equity. The methodology section details a mixed-methods approach for examining the three elements in the planning process in the five cities. A short background section follows, relating how each city came to the decision to reorient its climate action on equity. Next, I present the findings on the integration of equity into the plans and the three elements of equity. A concluding discussion follows, which returns to assertions and accepted positions in the literature review and identifies challenges that lie ahead for achieving climate equity in implementation. Equity will be in competition with other goals and tradeoffs will have to be negotiated.

Literature Review: The Elements of Climate Equity

Urban climate action plans provide a framework for measuring greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and related climatic impacts, set goals for reducing emissions, and outline actions to achieve the goals (mitigation). In addition, many cities have separate plans for reducing the vulnerability of human and natural systems to the effects of climate change (adaptation). Although there is a literature about the extent to which equity is integrated into both types of plans, my analysis here focuses on the former.

How do planners determine when a climate action plan has adequately incorporated equity? A simple way is to use content analysis to identify how often and how well equity concerns are integrated in a climate action plan. A small literature on this approach has emerged. Schrock, Bassett, and Green (Citation2015) counted mentions of equity in climate action plans of 28 cities; distinguished whether it was identified as a problem, goal, or action item; and assigned plans a score based on the quantity and quality of the equity concerns and actions. They concluded that equity was a relatively low priority of the 28 U.S. cities they examined. Building on this analysis, Waud (Citation2018) examined whether social justice was identified as a problem, goal, or action in the climate action plans of 19 Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance member cities. She differentiated three categories of inclusion: absent, isolated, or integrated. Isolated refers to plans in which equity considerations are in a separate section rather than integrated throughout the plan’s sections. Integrated plans have equity as a key principle discussed in all sections.

Two more recent studies have larger samples. According to the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (2021), only 24 of 75 major U.S. cities address equity outcomes in energy and climate action planning. An examination of equity in 173 city and county climate action plans revealed that although 68% of plans produced between 2013 and 2016 had equity language, it was not well defined in action (Angelo, MacFarlane, & Sirigotis, Citation2020).

Only one study focused on whether climate action plans include metrics on achieving equity in implementation. York and Jarrah (Citation2020) examined the climate action plans of 66 cities internationally and identified only two, Chicago and New York, that specified a metric for progress toward energy equity: reducing energy burden for low-income residents. Only eight of the cities actively measured equity as it relates to energy and transportation implementation.

Clearly, the field needs more precise measures to assess how well equity is integrated and evaluated in climate action plans. To provide this clarity, it is useful to consider the three types of equity discussed in the literature: procedural, distributional, and recognitional. This distinction among different aspects of equity adds additional refinement to evaluating a plan and its implementation. I consider each separately below.

Procedural Equity

Public participation is a well-developed focus of analysis in urban planning. Arnstein’s (Citation1969) ladder of participation has been the standard for measuring how power in urban planning can be redistributed from the “haves” to the “have-nots.” The ladder advanced from nonparticipation to degrees of tokenism to citizen power (Tritter & McCallum, Citation2006). Although the ladder has been adapted over the years, the focus on meaningful engagement from disenfranchised groups has remained a concern of the planning profession (Slotterback & Lauria, Citation2019).

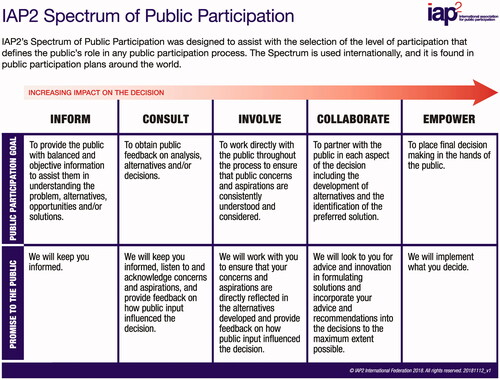

Another framework that analyzed power redistribution, developed by the International Association of Public Participation, built on Arnstein’s ladder (). It identified five levels of shared decision-making authority, starting with inform, then consult, involve, and collaborate, with the highest being empowerment, which gives final decision-making power to residents and commits to implementing their decisions.

Figure 1. Spectrum of public participation. © International Association for Public Participation (www.iap2.org). Reprinted with permission.

Its focus on direct democracy as the goal of participation has been questioned (see Grcheva & Vehbi, Citation2021; Ross, Baldwin, & Carter, Citation2016; Nabatchi, Citation2012). In fact, the framework identified direct democracy as a possibility, not the ultimate goal. What differentiates it from Arnstein’s ladder is that it identified the promise to the public at each level, recognizing that that promise is not always empowerment. Thus, what becomes important in assessing a city’s commitment to shared decision making is whether it delivers on its promise to the public, not whether it achieves the highest level of participation. In this sense, authenticity of participation is key.

The American Planning Association has defined authentic participation as including input “from all segments of the community in analyzing issues, generating visions, developing plans, and monitoring outcomes” (Godschalk & Rouse, Citation2015, p. 3). Many have argued that most participation in urban climate adaptation planning is not authentic (see Aldunce et al., Citation2015; Anguelovski et al., Citation2016; Archer & Dudman, Citation2015; Schlosberg, 2012, Citation2017; Shi et al, Citation2016). A common way that participation loses its authenticity is when city government officials go to the same established community groups rather than reaching out to a broader—and harder to solicit—set of groups or individuals (Godschalk & Rouse, Citation2015; Karner et al., Citation2019; Laskey & Nichols, Citation2019).

There has been much discussion of the need for more collaboration between vulnerable populations, planners, and other stakeholders in identifying and evaluating adaptation goals and strategies (see Chu et al., Citation2016; Cornell et al., Citation2013; Holland, Citation2017; Kirchhoff et al., Citation2013; Rosenzweig et al., Citation2011). But even with high levels of participation, the process is often designed in a way that creates disempowering environments, something that planners must be sensitive to given the high level of distrust of city government that exists in frontline communities (Clark, Citation2021; Fung, Citation2003). Thus, establishing trust needs to be incorporated into the participation agenda.

Another concern is maintaining participation during implementation (see Burton & Mustelin, Citation2013; Malloy & Ashcroft, Citation2020; Mees, Driessen, & Runhaar, Citation2015). Rosen and Painter (Citation2019) argued for a coproduction: an iterative process in which strategies are reoriented as needed during implementation based on input from residents. That this literature is not well developed suggests that the planning profession needs to focus more on participation during implementation as well as in the planning process.

Distributional Equity

Distributional equity refers to how benefits and burdens of climate action are allocated among different groups or neighborhoods. Much of this literature has discussed that climate change affects the most vulnerable people in developing countries and obligates developed nations responsible for the problem to fund and implement solutions (see Markandya, Citation2011; Mendelsohn, Dinar, & Williams, Citation2006). A literature focused on cities is emergent.

At the municipal level, several critics have argued that climate action advances the neoliberal agenda rather than seeking to redistribute assets, ameliorate inequality, or address previous harms (see Aldunce et al., Citation2015; Fainstein, Citation2010, Citation2018; Friend & Moench, Citation2013, Citation2015). Although cities do not have much power to address structural inequality, they can provide more equitable distribution of the goods of climate-related programs, land uses, and infrastructure (Meerow, Pajouhesh, & Miller, Citation2019). On the adaptation side, that means fair access to resilience infrastructure (Fainstein, Citation2018; Meerow & Newell, Citation2017). And urban climate action can focus on undoing previous harms and prioritizing frontline neighborhoods (see Fainstein, Citation2014). In both mitigation and adaptation, distributional equity means prioritizing resources to communities that have experienced disproportionate exposure to pollution, the effects of climate change, and inequities overall (Yuen et al., Citation2017).

On the mitigation side, distributional equity can be realized by addressing racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in access to energy-efficient residential technology (Carley & Konisky, Citation2020; Lukanov & Krieger, Citation2019; Reames et al., Citation2018). Focusing energy retrofits on low-income communities addresses energy poverty, a condition defined by paying a disproportionately higher percentage of one’s income (defined as exceeding 6% of income)Footnote1 on energy. Sovacool et al. (Citation2016) treated energy poverty as a distributive justice issue.

Typically, programs to expand renewable energy adoption cater to homeowners who can pay the upfront costs needed to take advantage of subsidies (Fitzgerald, Citation2010, Citation2020; Stephens, Citation2019). Policies such as feed-in tariffs, which seek to create a stable investment environment for renewable energy, raise electricity prices; although the amount is small for many residents, for energy-burdened households it can be significant (see Zachmann, Fredriksson, & Claeys, Citation2018).

Distributional equity also comes to play in the electrification of transportation. Individuals must be relatively wealthy to take advantage of subsidies to purchase electric vehicles. As cities transition to electric buses, distributional equity would call for first deployment in the most polluted frontline neighborhoods.

The policies and programs of a climate plan focused on distributional equity prioritize frontline communities across all aspects of the plan. A climate action plan focused on distributional equity should specify the recipients of each of the plan’s actions, what is being distributed, and the principles used to make that decision (see Bell, Citation2004).

Recognition

The concept of recognition is not as clearly defined as procedural and distributional equity. Some scholars have only acknowledged procedural and distributional equity (see Ivanova et al. Citation2020; Preston et al., Citation2014). Others have considered recognition a third aspect of climate equity that addresses who is included and respected in determining goals and outcomes and ensuring that all a city’s demographics are represented (Blue, Rosol, & Fast, Citation2019; Fraser, Citation2009; Schlosberg, Citation2007). Recognitional justice requires that planners identify which groups have been ignored and increase the diversity (race, gender, age, socioeconomic status, etc.) of participants in developing plans and policy (Gillard et al., Citation2017; Jenkins et al., Citation2016) The goal is to “prevent domination, nonrecognition, misrecognition, devaluation, and disrespect” (Blue, Rosol, & Fast, Citation2019, p. 368).

A closely related concept is contextual equity. McDermott and Schreckenberg (Citation2013, p. 420) defined contextual equity as acknowledging “the uneven playing field created by the pre-existing political, economic and social conditions under which people engage in and benefit from resource distributions—and which limit or enable their capacity to do both.” In this sense, contextual equity defines how access to both procedural and distributional equity is constrained or facilitated.

In contrast, Sovacool et al. (Citation2016) incorporated the question of who decides and whose interests are recognized in decision making under procedural equity. They viewed procedural justice as incorporating who is recognized, who gets to participate, and how power is distributed in decision-making forums (Sovacool et al., Citation2016, p. 2).

Still others have defined recognition more as acknowledgement, an “understanding of historic and ongoing inequalities and efforts to address them” (Carley & Konisky, Citation2020, p. 10). A similar phrasing, “Justice as recognition recognizes the historical context that created inequalities in the first place and contribute to unequal distributions,” also emphasizes acknowledgment (Hughes & Hoffman, Citation2020, p. 3). Schlosberg et al. (Citation2017) argued that recognition of existing injustices and conditions is an essential step in developing community‐based adaptation strategies. In From Here to Equality, Darity and Mullen (Citation2020) emphasized the need for acknowledgment, which they defined as the admission of wrong and the declaration of responsibility for restitution by the culpable party, as a precondition for reparations.

In conclusion, recognition has been defined in several distinct ways. Further, the interconnections among distributional, procedural, and contextual equity have not been well defined. As noted by McDermott, Mahanty, and Schreckenberg (Citation2013, p. 421), “Distributional, procedural and contextual equity should be seen as interdependent aspects of a multidimensional, multiscalar phenomenon whose interrelationships are currently poorly understood.” Not relying on the scholarly literature, practitioners may have different meanings for all three.

In my analysis I attempt to contribute to this theoretical discussion by examining the interrelationships among the three types of equity in the development of climate action plans. Although identifying how often equity and related terms are mentioned in plans is an important first step, planners need to expand the analysis to assess how the different aspects of equity are integrated into the planning process.

Methodology

The literature leads to four sets of questions, which I examined through case studies of five cities. I used multiple methods to explore the complexity of the planning process to gain an in-depth understanding of how equity is prioritized in the planning process and plans (see Creswell, Citation2008; Simons, Citation2009; Yin, Citation2014). The case studies were based on content analysis of the plans and interviews with sustainability directors and participants engaged in the planning process.

The content analysis provided an assessment of how well equity is integrated into the plans, the extent to which distributional equity is addressed, and how recognition is discussed. Following Guyadeen and Seasons (Citation2015, p. 100), the content analysis included plan evaluation, which assessed the plan against identified criteria identified in questions 1 through 3 below. This plan and planning evaluation is distinct from formative and summative evaluations of the implementation process (Patton, Citation2002).

The interviews provided insights into what those involved in the planning process sought to achieve. I conducted interviews with the current and past directors of sustainability in charge of the planning process. There was a total of 19 interviews with 13 individuals, which I conducted in May and June of 2020, with 5 follow-up interviews in September.Footnote2 In addition, I conducted interviews with seven participants from frontline communities in Providence and Austin in February and March of 2021. Because these were the most recently completed plans, the possibility of locating participants was more feasible. To obtain a convenience sample, I contacted participants in both cities and asked for contact information for individuals who were highly engaged in the planning process.

The sample size for the interviews was small. I intentionally only included current and past sustainability directors to understand their motivations and strategies for placing equity at the forefront of the climate action plans. A representative sample of community participants was beyond the scope of this study. Small, purposive samples in mixed-methods studies are widely used to provide richly textured information from participants (see Palinkas et al., Citation2015; Vasileiou et al., Citation2018).

The interviews were semistructured, following the research questions detailed below. To analyze the transcripts, I used a combination of thematic and narrative analysis to identify, organize, describe, and analyze key themes related to the research questions (See Nowell, Norris, & White, Citation2017).

The first questions relied on content analysis to compare how equity was treated in the previous and updated plans:

1. To what degree is equity integrated into all aspects of the updated plan? Does the plan include a method for analyzing how equity is incorporated into each goal? Does the plan identify metrics for determining the extent to which equity goals are achieved during implementation?

For this part of the content analysis, a research assistant and I independently reviewed the plans to count mentions of equity and environmental justice. Because most of the earlier plans did not emphasize equity, we also searched for low-income, minority, and race/racial. We then added an “evaluated” category to assess whether the plans included a strategy for measuring progress toward equity goals during implementation. We did not expect to find differences in mentions of equity but corroborated each other’s assessment of integration. Next, I reviewed each section of the plan to determine if and how equity was incorporated.

Much of the literature focuses on procedural equity, so I focused on it more than the other two aspects in this second set of questions:

2. What was the extent of participation in developing the plan’s goals by residents of vulnerable communities? How was participation solicited? How was resident input incorporated into the plan? How did the participants from frontline communities perceive their participation?

This analysis of procedural equity used the framework developed by the International Association of Public Participation, discussed above.Footnote3 It is widely used and adapted by governments and organizations (Nabatchi, Citation2012).Footnote4 The key factor of importance here is whether the city delivered on its promise of engagement, not whether the city achieved the highest level of decision authority. The city’s level of shared decision authority was determined by content analysis of the plans (what they said they did) and interviews (what they intended to do).

The third set of questions examined the extent to which the plan included a strategy for providing an equitable distribution of its actions:

3. How does the plan address distributional equity? Does it prioritize or at least equalize implementation in frontline communities? Does the updated plan detail a strategy for periodically evaluting progress toward achieving distributional equity?

Given the multiple interpretations of recognition, my goal in the fourth question was to get a sense of what the term means to practitioners and others involved in the planning process:

4. How do those involved in the planning process perceive recognition equity?

Based on my field-based knowledge of U.S. urban climate action plans and interviews with heads of leading urban networks and three foundation officers or staff of the Funders’ Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities, I identified the five cities.

Background: Why Equity, Why Now?

In all five cities, the decision to focus the plan updates on equity emerged out of a realization that the previous plan did not adequately address or even worsened conditions in frontline communities. Each sustainability director told a slightly different version of the same story.

Portland and Austin cited their participation in the Urban Sustainability Directors’ Network equity working group as the impetus for reviewing their previous plans from an equity lens. As one planner in the Portland Bureau of Sustainability noted, “We realized that it was people of color and low-income residents that were experiencing the brunt of climate change effects and that they had to be the focus of our work.” Austin sustainability staff mentioned awareness of a long-term history of environmental racism stemming from the city’s 1928 master plan that zoned industrial uses almost exclusively in Black and Latino neighborhoods (see Zehr, Citation2020). From there, they collectively decided that it was time for planning to rectify past injustices. Likewise, Baltimore’s director of sustainability related how the planning process for the updated plan was rooted in recognition of previous omissions. In contrast, Cleveland’s sustainability staff thought they had addressed equity in the previous plan, but realized it was short on community input. In Providence, several environmental justice organizers were eager to work with the new director of sustainability to update the city’s former plan.

Findings

Equity Focus

As expected, the updated plans mentioned equity considerably more frequently. The plans are organized differently, but all integrated equity extensively in each section, achieving the rating of “integrated.” The plans all discussed evaluation, but to varying degrees. ().

Table 1 Equity assessment of climate action plans.

The five plans discussed the equity impacts of all goals and how well implementation would advance social and racial equity. They provided detailed accounting of disparities by zip code. For Cleveland, equity was “the main thread that ties this plan together” (City of Cleveland, Citation2019, p. 11), whereas Austin’s plan stated what is at the essence of all five plans: “If we’re not addressing equity, we’re perpetuating injustice” (Austin Office of Sustainability, Citation2020, p. 9). The Providence Climate Justice Plan committed to prioritizing action in the most affected communities and identified two green justice zones (City of Providence, Citation2019, p. 13).

Procedural Equity

Each of the sustainability directors spoke of the importance of creating an authentic participation process and identified several ways they attempted to achieve it. The first step in all cities was for sustainability staff to undergo antiracism training that would guide how they engaged with residents of frontline communities. In three cities, Austin, Cleveland, and Providence, members of the advisory committees also completed antiracism training with city staff before the planning process started.

The second step was recruitment. The directors and their staff commented that they realized they had to spend more time on recruiting community participation if it was to be representative of the city’s residents, particularly residents from low-income communities and communities of color. In Portland’s case, there was not a base of community and environmental justice organizations on which to draw. The former director of sustainability noted that at the time an environmental justice community did not exist. Community organizations focused on underserved populations were not targeting climate change as an issue. After months of effort, six organizations provided representatives to an 18-member Equity Working Group, which comprised the city’s environmental, community, and industry groups; youth; public health organizations; and several communities (Black, Asian American, Native American).

Austin hired a community engagement specialist familiar with the city’s landscape of community organizations to organize the participation process. A key difference in the planning process for the updated plan, the climate program manager noted, was that the search for community members willing to participate lasted only 2 weeks during the previous planning process, whereas this time it took 3 months to recruit a larger and more diverse group.

The cities organized the participation process in slightly different ways. All but Baltimore had advisory committees that met for varying lengths of time to develop the plan, and Cleveland and Austin also solicited participation from residents who were not involved in the planning process.

Cleveland created a Climate Action Advisory Committee with 90 members from 50 community and advocacy organizations.Footnote5 The committee used a Racial Equity Tool, adapted from Portland, to ensure that equity was integrated throughout the plan.Footnote6 To inform the planning process, the committee held workshops in 12 environmental justice neighborhoods over 6 months, with about 300 people in attendance, representing all the city’s demographic groups.

Baltimore Sustainability staff worked with their department’s Equity in Planning Committee to explore strategies for reaching enough people to gain perspectives that would reflect the demographics of the city. The committee developed an outreach strategy to disseminate information in multiple languages and used multiple survey methods (e.g., in person, phone, and online) to obtain resident input.

To conduct outreach, the team appointed more than 125 sustainability ambassadors, almost 70% Black, to interview residents about their needs and ideas. The strategy for obtaining a diversity of views was to go to the people—conducting interviews at bus stops, in grocery stores, schools, churches, and doorsteps—rather than holding workshops that might attract only the most dedicated. This input was used in developing the updated plan.

Providence’s sustainability director obtained planning grants from private foundations, then partnered her team with several environmental justice organizations to facilitate a new kind of planning process in which the Office of Sustainability would be an equal among partners. Five members representing city departments and frontline communities formed a Racial and Environmental Justice Committee to explore ways to integrate racial equity into the plan.

The committee released its Equity in Sustainability Report in June 2016.Footnote7 It listed 12 priorities that emerged from the planning process, including cleaner streets, eliminating industrial hazards, improving safety, access to public transit, and addressing gentrification. A second year of foundation funding supported development of the updated plan. The sustainability director explained, “Our intent was to shift the decision-making power to frontline communities, whose residents really led the development of this work.”

Austin’s extended outreach effort achieved the city’s goal of having people of color comprise more than half of the residents participating in the planning process. The effort succeeded in recruiting 140 people in five advisory groups. Each member committed to attending two 2-hour planning meetings per month for 6 months. A separate group of 12 climate ambassadors gathered feedback from residents on changes they wanted to see in their neighborhoods.

A third aspect of making participation authentic is ensuring that it is sustained. Two strategies mentioned were organizing meetings so everyone’s opinions were valued and paying participants for their time. The first was mentioned by Portland’s sustainability director, who emphasized that it took a while to develop an approach to the meetings that did not leave community representatives feeling that the power dynamic was unbalanced. Although time spent on process put the schedule behind, working group members agreed that getting the process right was more important than deadlines. To focus the meetings, the cities used some adaptation of an equity assessment tool to examine policies, plans, programs, and budgets to eliminate individual, institutional, and structural racism.

The sustainability directors noted that paying participants for their time sent an important message of how much their input was valued. In Austin, 10 ambassadors were paid $1,500 each for their work, and two organizations that served as ambassadors received $3,000 each. In Providence, community representatives attended about 10 hours of meetings per month for which they received a $1,300 stipend. Two cities, Portland and Providence, had support from private foundations to pay stipends.

Although a small sample, the seven community participants I interviewed spoke to the inclusivity of the participation process. One participant from a frontline community commented, “We thought of everyone—people from each marginalized community, indigenous, queer—I was part of youth base.” Another elaborated, “The planners are all White. The Undoing Racism training helped us all to trust each other and work together.” A third community participant noted that the city demonstrated that it was serious about obtaining representation: “After the first meeting, when they saw that some groups weren’t represented, they went out and recruited more people.” All seven agreed that their input helped to shape the plan’s goals, though three said they are waiting to see what happens in implementation before concluding that the city government is addressing their needs.

As to the promise the city gives to the public, three of the cities promised to incorporate the advice and recommendations from their public advisory committees into the plans and delivered in creating a collaborative planning process. In contrast, Baltimore’s commitment was only to involve residents in expressing concerns and aspirations, which was achieved through the surveys of residents.

Providence was the only city that promised participants that their views would prevail and be implemented. The sustainability office’s governance model built on the International Association of Public Participation framework. The levels of participation are ignore (marginalization), inform (placation), consult (tokenization), involve (voice), collaborate (delegated power), and defer to (community ownership). The intent to defer to the community in implementation is underway.

Distributional Equity

There are two elements to addressing distributional equity. The first is establishing metrics for equity outcomes. The second is the actual distribution of climate action benefits, which should either prioritize frontline communities as a way of redressing past environmental harms or provide fair access to low-income communities that were unable to take advantage of previous rounds of climate action (e.g., solar panels, green space). Because this was an analysis of the planning process and implementation is just beginning, I focused only on the first aspect.

All five cities used some version of an equity lens tool to examine the distributional aspects of each element of the updated plan. The tool facilitates rating each goal for its feasibility, impact, and equity to guide the city in making decisions that have the most potential to reduce existing disparities as well as provide benefits to frontline communities. The plans varied, however, in their specificity on how equity would be measured in implementation.

Baltimore’s Commission on Sustainability and the Office of Sustainability produced an annual report assessing equity efforts based on indicators such as the reduction of the number of vacant buildings in a neighborhood or an increase in available job opportunities for residents. These indicators, however, did not align with the goals of the climate plan. Austin simply mentioned that “We will continue to build authentic, inclusive relationships with community members and involve them in the decision-making process when designing projects and programs that address climate change.” (City of Austin Office of Sustainability, Citation2020, p. 100).

Cleveland’s discussion of equity metrics was somewhat vague in the updated plan, mentioning only holding annual summits as the mechanism for the public to discuss, celebrate, and evaluate progress toward all sustainability goals, including equity. However, Cleveland planners intended to develop specific equity strategies and identified how they would be implemented in more detailed roadmaps; they have completed the first one.

Once the updated plan was released, Mayor Jackson announced that the city would transition to 100% clean energy by 2050. With grant funding from several local foundations, the city engaged community residents and other stakeholders in a planning process for achieving that goal equitably. The resulting action plan, Clean and Equitable Energy Future, was released in April 2021. The metrics against which implementation will be evaluated included equitable access to clean energy, energy cost savings (reducing energy burden), and clean energy job creation. The plan also discussed workforce development and job training, noting, “It is imperative that any workforce development efforts place an intentional focus on ensuring that historical and contemporary inequity, disparity, and racism are accounted for and addressed” (City of Cleveland, Citation2021, p. 59). The action plan ensured that the benefits of the renewable transition would be fairly distributed to low-income communities and communities of color.

A Portland city staffer gave an example of how the equity toolkit shifted how goals were established: Whereas the old plan identified a goal of increasing transit ridership, the new plan first asked how frontline communities were able to participate in achieving that goal. Community feedback revealed that concerns about transit safety and affordability prevented people from riding. In response, the planner noted, “We had to change the question that drives policy from, ‘How do we get more people on the bus?’ to ‘Who can’t ride the bus safely and conveniently?’” She continued, “We had to examine why people weren’t riding the bus instead of assuming that more transit means more riders.” This shift in focus, she continued, influenced future transit planning.

Recognition

There are several definitions of recognitional equity in the literature, yet when I asked city staff and community participants which aspects of recognition resonated with them, all responded that it meant acknowledgment of past harm. This was expressed in multiple ways. A sustainability director in Austin used the analogy of indigenous land acknowledgement statements with which he and his colleagues start presentations and meetings. “It raises awareness of our history and our role in it,” he noted, “and may be a small step, but it is a first step in creating change.” He continued that it is in this spirit that the Climate Equity Plan begins with a land acknowledgement that also acknowledges historic racial inequality:

Climate change is inextricably linked to humanity’s long history of inequality and injustice perpetuated by legacies of colonialism and slavery, based on the exploitation of people, land, and nature. Today, the ongoing displacement of Black, Indigenous, and communities of color on Austin’s East Side is connected to legacies of extraction of labor, theft of land, transformation of landscapes, and loss of cultures. In pursuit of resources, countries destroyed many of the ecosystems, traditional human knowledge, and interactions necessary for preventing climate change. Therefore, we need to be intentional about how we build respect for The Land and her Indigenous Peoples.

Likewise, Providence’s director noted the importance of recognizing past harms as a starting point to addressing them. The Climate Justice Plan begins with an acknowledgement that

In Providence and around the world, people of color have contributed the least to the climate crisis, yet they are disproportionately burdened by the polluting industries that are causing climate change and other environmental degradation. They are also most exposed to the impacts of climate change, like extreme heat and flooding. In Providence, there are many examples of these environmental injustices, or what is also known as environmental racism.” (emphasis in original; City of Providence, Citation2019, p. 13)

The importance of acknowledgement also was expressed by the participants from frontline communities. One expressed a view repeated by several others: “My family has lived here for 12 generations. We were here on this land before any of you were here. The statement is an acknowledgment for people who were guilty. We know. How did you not know? It has to be the starting point.” Another participant commented, “Acknowledgement of past harm is something this country doesn’t do well. Having it [the statement] there makes me feel that the city is taking us seriously.” Yet another said, “Recognition absolutely had to be an acknowledgement of communities that were redlined and all that has happened since then. Forward movement requires honesty before remedy.”

Discussion

Equity was integrated into all the updated plans and, to some degree, all plans discussed how it would be measured in implementation. Three steps seem essential to building authentic participation: antiracism training, a concerted effort to bring underrepresented groups to the table, and ensuring that all feel valued in the planning process, both in terms of the way meetings are structured and literally in paying participants for their time.

The International Association of Public Participation framework proved to be a useful tool for determining whether a city delivered on its promise for shared decision making. Baltimore promised involvement and delivered. Cleveland, Austin, and Portland promised an inclusive and collaborative goal-setting process and delivered. Providence took the framework one step further to deliver a plan that deferred to the community.

The takeaway for other cities wishing to prioritize equity in climate action planning is that authentic participation is a trust-building process. In Portland, a first mover on climate equity, a base of environmental justice organizations did not exist at the time. The city had to build capacity as well as trust. The directors and staff of most urban sustainability offices are White. Historically, the urban planning profession has disenfranchised many communities of color and low-income neighborhoods. Members of frontline communities often are mistrustful of planners asking for their input. The antiracism training was a first step in trust building. Paying frontline community participants for their time was another aspect of expressing value.

The findings on participatory equity are not disconnected from those on recognition. What is sometimes referred to as recognitional justice—increasing the diversity of participants involved in developing plans and policy and preventing domination or disrespect in the planning process—was baked into the approach to promoting authentic participation in the five cities. These findings concur with Sovacool et al. (Citation2016) in that who decides and whose interests are represented is a core aspect of procedural equity.

As to distributive justice, the intent of these plans was to ensure that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color receive their fair share of climate benefits (e.g., accessible transit, bike lanes, energy retrofits, solar energy, green space). To varying degrees, the plans identified metrics for equitable distribution of the plans’ goods and services and committed to reporting. The extent to which this happens during implementation needs to be monitored. Cleveland’s Clean and Equitable Energy Future work plan provided an example of inequality, and racism can be accounted for and addressed in implementation.

My limited interviews suggested that neither the sustainability planners nor the frontline community participants were naive about potential conflicts in implementation. Achieving a rapid transition to renewable energy, for example, may mean installing solar panels on as many roofs as possible. To the extent that existing programs that subsidize homeowners to install them is the fastest way to expand solar, more equitable solutions could slow progress. Similar arguments can be made for electric vehicles. This is not to say that more equitable solutions cannot be developed, just that there could be initial resistance.

Cities also have limited powers that can be slowed by state authority. A Providence participant living in one of the green zones created by the plan referenced the October 2018 regulatory approval of a $180 million National Grid liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility on the industrial waterfront. Opponents pointed out that it would increase the state’s dependence on dirty shale gas obtained by hydraulic fracturing and lock in carbon emissions for the life of the facility. The Rhode Island Department of Health and several environmental and community organizations criticized the proposal, but Governor Gina Raimundo fought having their concerns included in the proposal that went to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for approval. So even though procedural justice was exemplary in the Providence Climate Equity Plan, delivery of many environmental justice promises will meet with opposition. As Campbell (Citation1996) pointed out in his classic article on the contradictions of sustainable development, city (and state) officials will almost always choose economic concerns over environmental or equity ones. That is the challenge of climate equity/justice planning.

Acknowledgments

I thank the anonymous reviewers for their enormously helpful comments. Cassandra Valcourt provided valuable research assistance. Many thanks to the sustainability directors, staff, and community participants who took the time to be interviewed.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joan Fitzgerald

JOAN FITZGERALD ([email protected]) is a professor in the School of Public Policy & Urban Affairs at Northeastern University.

Notes

1 Defined by Fisher, Sheehan, and Colton (2021).

2 A draft of the paper was distributed to all five sustainability directors. Four responded that it was accurate.

3 The use of this framework was mentioned by members of the Urban Sustainability Directors’ Network in interviews I periodically conduct with the organization’s staff and sustainability directors for my research.

4 See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2017) and Stuart (2017).

5 The list of individuals and their affiliation can be found at https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/sustainablecleveland/pages/56/attachments/original/1531232689/CAAC_LIST.pdf?1531232689.

6 Race Forward partners with community and other organizations to take action toward racial justice (https://www.raceforward.org). It is the home of Government Alliance on Race and Equity, a national network focused on advancing racial equity (https://www.racialequityalliance.org).

7 The Equity and Sustainability report is available at https://www.providenceri.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Equity-and-Sustainability-SummaryReport-2-20-reduced.pdf.

References

- Aldunce, P., Beilin, R., Howden, M., & Handemer, J. (2015). Resilience for disaster risk management in a changing climate: Practitioners’ frames and practices. Global Environmental Change, 30, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.010

- Angelo, H., Macfarlane, K., & Sirigotis, J. (2020). The challenge of equity in California's municipal climate action plans. UC Santa Cruz Institute for Social Transformation. https://transform.ucsc.edu/challenge-of-equity/

- Archer, D., & Dodman, D. (2015). Making capacity building critical: Power and justice in building urban climate resilience in Indonesia and Thailand. Urban Climate, 14(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.06.007

- Austin Office of Sustainability. (2020). Austin climate equity plan 2020.

- Anguelovski I., Shi, L., Chu E., Gallagher, D., Goh, K., Lamb, Z., Reeve, K., & Teicher, H. (2016). Equity impacts of urban land use planning for climate adaptation. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 36(3), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16645166

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Baker, T., Abderhalden, F. P., Alward, L. M., & Bedard, L. E. (2019). Exploring the association between procedural justice in jails and incarcerated people’s commitment to institutional rules. Corrections, 6(3), 2377–4657. https://doi.org/10.1080/23774657.2019.1618224

- Baltimore Office of Sustainability. (2013). Baltimore climate action plan. https://www.baltimoresustainability.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/BaltimoreClimateActionPlan.pdf

- Baltimore Office of Sustainability. (2019). The 2019 Baltimore sustainability plan. https://www.baltimoresustainability.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Sustainability-Plan_01-30-19-compressed-1.pdf

- Bell, D. (2004). Environmental justice and Rawls’ difference principle. Environmental Ethics, 26(3), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics200426317

- Blue, G., Rosol, M., & V. Fast. (2019). Justice as parity of participation: Enhancing Arnstein’s ladder through Fraser’s justice framework. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1619476

- Botchwey, N. D., Johnson, N., O’Connell, L. K., & Kim, A. J. (2019). Including youth in the ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1616319

- Brown, S. (2020, May 6). How COVID-19 is affecting Black and Latino families’ employment and financial well-being. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-covid-19-affecting-black-and-latino-families-employment-and-financial-well-being

- Bulkeley, H., Edwards, G.A.S., & Fuller, S. (2014). Contesting climate justice in the city: Examining politics and practice in urban climate change experiments. Global Environmental Change, 25, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.01.009

- Bulkely, H., Carmin, J., Castán Broto, V., & Edwards, G. A. S. (2013). Climate justice and global cities: Mapping the emerging discourses. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 914–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.010

- Burton, P., & Mustelin, J. (2013). Planning for climate change: Is greater public participation the key to success? Urban Policy and Research, 31(4), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2013.778196

- Campbell, S. (1996). Green cities, growing cities, just cities? Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369608975696

- Carini, F. (2018, February 9). Environmental racism puts South Side’s health at risk. ecoRI News. https://www.ecori.org/social-justice-archive/2018/2/8/environmental-racism-live-and-well-on-the-south-side

- Carley, S., & Konisky, D.M. (2020). The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nature Energy, 5, 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0641-6

- Carson, L. (2008). The IAP2 spectrum: Larry Susskind, in conversation with IAP2 members. International Journal of Public Participation, 2(2), 67–84. http://www.activedemocracy.net/articles/Journal_08December_Carson.pdf

- Cassie, R. (2019). Hell and high water. Baltimore Magazine. https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/section/historypolitics/climate-change-wreaking-havoc-baltimore-infrastructure-public-health/

- Chen, J. T., & Krieger, N. (2021). Revealing the unequal burden of COVID-19 by income, race/ethnicity, and household crowding: US county vs ZIP code analyses. Journal of Public Health Management Policy, 27(Supp C), S43–S56. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001263

- Chin, T., Kahn, R., Li, R., Chen, J. T., Krieger, N., Buckee, C. O., Balsari, S., & Kiang, M. V. (2020). US-county level variation in intersecting individual, household, and community characteristics relevant to COVID-19 and planning an equitable response: A cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.08.20058248

- Chu, E., Anguelovski, I., & Carmin, J. (2016.) Inclusive approaches to urban climate adaptation planning and implementation in the Global South. Climate Policy, 16(3), 372–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1019822

- City of Austin Office of Sustainability. (2020). 2020 Austin climate equity plan. http://www.austintexas.gov/edims/document.cfm?id=347852

- City of Cleveland. (2019). Cleveland climate action plan update. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Z3234sMp7S7MjaXvMgcZtcAaYs4x2oHE/view

- City of Cleveland. (2021). Cleveland’s clean and equitable energy future. https://clecityhall.files.wordpress.com/2021/04/greenlink_clevelandreport_040921_final_single_page1-1.pdf

- City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. (2009). Climate action plan 2009. City of Portland and Multnomah County. https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2019-08/cap_may_2010_web_0.pdf

- City of Portland and Multnomah County. (2015). Climate action plan 2015—Local strategies to address climate change. https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2019-07/cap-2015_june30-2015_web_0.pdf

- City of Providence. (2019). The city of Providence’s climate justice plan—Creating an equitable, low-carbon, and climate resilient future. https://www.providenceri.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Climate-Justice-Plan-Report-FINAL-English.pdf

- Clapp, E., & McGrath, M. M. (2011). Built environment atlas: Active living, healthy eating, Multnomah County, Oregon. Multnomah County Health Department, Office of Health & Social Justice.

- Clark, J. K. (2021). Public values and public participation: A case of collaborative governance of a planning process. The American Review of Public Administration, 51(3), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020956397

- Contreras, S. (2019). Using Arnstein’s ladder as an evaluative framework for the assessment of participatory work in postdisaster Haiti. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1618728

- Cornell, S., Berhkout, F., Tuinstra, W., Tàbara, J.D., Jäger, J., Chabay, I., de Wit, B., Langlais, R., Mills, D., Moll, P., Otto, I. M., Petersen, A., Pohl, C., & van Kerkhoff, L. (2013). Opening up knowledge systems for better responses to global environmental change. Environmental Science & Policy, 28, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.008

- Creswell, J., & Poth, C. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

- Creswell, J. (2008). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Darity, W. A. Jr., & Mullen, A. K. (2020). From here to equality. University of North Carolina Press.

- Exner, R. (2019, September 26). Poverty in Cleveland and Cuyahoga suburbs remains above pre-recession levels, new census estimates say. Cleveland.com. https://www.cleveland.com/datacentral/2019/09/poverty-in-cleveland-and-cuyahoga-suburbs-remains-above-pre-recession-levels-new-census-estimates-say.html

- Fainstein, S. (2010). The Just City. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press.

- Fainstein, S. S. (2018). Resilience and justice: Planning For New York City. Urban Geography, 39(8), 1268–1275. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1448571

- Fainstein, S. S. (2014). The just city. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 18(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2013.834643

- Finn, D., & McCormick, L. (2011). Urban climate change plans: How holistic? Local Environment, 16(4), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.579091

- Fisher, Sheehan, & Colton. (2021). Home energy affordability gap. http://www.homeenergyaffordabilitygap.com/01_whatIsHEAG2.html

- Fitzgerald, J. (2010). Emerald cities: Urban sustainability and economic development. Oxford University Press.

- Fitzgerald, J. (2020). Greenovation: Urban leadership on climate change. Oxford University Press.

- Fitzgibbons, J., & Mitchell, C. L. (2019). Just urban futures? Exploring equity in “100 resilient cities.” World Development, 122, 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.021

- Fung, A. (2003). Survey article: Recipes for public spheres: Eight institutional design choices and their consequences. Journal of Political Philosophy, 11(3), 338–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00181

- Fraser, N. (2009). Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Columbia University Press.

- Friend, R., & Moench, M. (2015). Rights to urban climate resilience: Moving beyond poverty and vulnerability. WIREs Climate Change, 6(6), 643–651. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.364

- Friend, R., & Moench, M. (2013). What is the purpose of urban climate resilience? Implications for addressing poverty and vulnerability. Urban Climate, 6, 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2013.09.002

- Fung, A. (2015). Putting the public back into governance: The challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Administration Review, 75(4), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12361

- Fung, A. (2006). Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Administration Review, 66, 66–75. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4096571 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

- Gaber, J. (2019). Building “a ladder of citizen participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 188–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1612267

- Gillard, R., Snell, C., & Bevan, M. (2017). Advancing an energy justice perspective of fuel poverty: Household vulnerability and domestic retrofit policy in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 29, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.012

- Glucker, A. N., Driessen, P. P., Kolhoff, A., & Runhaar, H. A. (2013). Public participation in environmental impact assessment: Why, who and how? Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 43, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2013.06.003

- Godschalk, D. R., & Rouse, D. C. (2015). Sustaining places: Best practices for comprehensive plans. American Planning Association. http://doebay.net/sunshine/SustainingPlaces-bestpracticesforCPbook.pdf

- Gough, M. Z. (2015). Reconciling livability and sustainability: Conceptual and practical implications for planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15570320

- Gould, E., & Shierholz, H. (2020, March 19). Not everybody can work from home: Black and Hispanic workers are much less likely to be able to telework. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/black-and-hispanic-workers-are-much-less-likely-to-be-able-to-work-from-home/

- Grcheva, O., and Vehbi, B. O. (2021). From public participation to co-creation in the cultural heritage management decision-making process. Sustainability, 13(16), 9321. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169321

- Guyadeen, D., & Seasons, M. (2015). Plan evaluation: Challenges and directions for future research. Planning Practice and Research, 31(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2015.1081335

- Harris, L. M., Chu, E. K., & Ziervogel, G. (2018). Negotiated resilience. Resilience, 6(3), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2017.1353196

- Haughton, G., & McManus, P. (2019). Participation in postpolitical times. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1613922

- Holland, B. (2017). Procedural justice in local climate adaptation: Political capabilities and transformational change. Environmental Politics, 26(3), 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1287625

- Hughes, S., & Hoffman, M. (2020). Just urban transitions: Toward a research agenda. WIREs Climate Change, 11(3), E640. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.640

- Hughes, S. (2015). A meta-analysis of urban climate change adaptation planning in the U.S. Urban Climate, 14(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.06.003

- International Association of Public Participation. (2017, February 14). What is the spectrum of public participation? Sustaining Community. https://sustainingcommunity.wordpress.com/2017/02/14/spectrum-of-public-participation/

- Ivanova, D., Barrett, J., Wiedenhofer, D., Macura, B., Callaghan, M., & Creutzig, F. (2020). Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Environmental Research Letters, 15(9), 093001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab8589

- Ivanova, A., Zia, A., Ahmad, P., & Bastos-Lima, M. (2020). Climate mitigation policies and actions: Access and allocation issues. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20, 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09483-7

- Jenkins, K., McCauley, D., Heffron, R., Stephan, H., & Rehner, R. (2016). Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.10.004

- Karner, A., Brown, K. B., Marcantonio, R., & Alcorn, L. G. (2019). The view from the top of Arnstein’s ladder. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1617767

- Kinder, M., & Ross, M. (2020, June 23). Reopening America: Low-wage workers have suffered badly from COVID-19 so policymakers should focus on equity. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/reopening-america-low-wage-workers-have-suffered-badly-from-covid-19-so-policymakers-should-focus-on-equity/

- Kirchhoff, C. J., Lemos, M. C., & Engle, N. L. (2013). What influences climate information use in water management? The role of boundary organizations and governance regimes in Brazil and the U.S. Environmental Science & Policy, 26, 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.07.001

- Kovach, T. (2019, January 31). Cleveland’s environmental justice hotspots. Belt Magazine. https://beltmag.com/cleveland-environmental-justice-hotspots-map/

- Krieger, N., Waterman, P. D, & Chen, J. T. (2020). COVID-19 and overall mortality inequities in the surge in death rates by ZIP code characteristics: Massachusetts, January 1 to May 19, 2020. American Journal of Public Health. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305913

- Laskey, A. B., & Nicholls, W. (2019). Jumping off the ladder. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1618729

- Laurian, L., & Shaw, M. M. (2009). Evaluation of public participation: The practices of certified planners. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 28(3), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08326532

- Lukanov, B. R., & Krieger, E.M. (2019). Distributed solar and environmental justice: Exploring the demographic and socio-economic trends of residential PV adoption in California. Energy Policy, Elsevier, V. 134 (C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110935

- Malloy, J. T., & Ashcraft, C. M. (2020). A framework for implementing socially just climate adaptation. Climatic Change, 160, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02705-6

- Markandya, A. (2011). Equity and distributional implications of climate change. World Development, 39(6), 1051–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.01.005

- Matin, N., Forrester, J., & Ensor, J. (2018). What is equitable resilience? World Development, 109, 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.04.020

- McAlevey, J. (2016). No shortcuts: Organizing for power in the new gilded age. Oxford University Press.

- McCormick, K. (2020). Planning for social equity: How Baltimore and Dallas are connecting segregated neighborhoods to opportunity. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/planning-social-equity

- McDermott, M., & Schreckenberg, K. (2013). Examining equity: A multidimensional framework for assessing equity in payments for ecosystem services. Environmental Science & Policy, 33, 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.10.006

- McGlinchy, A. (2017, June 17). Residents of East Austin, once a bustling Black enclave, make a suburban exodus. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/07/12/536478223/once-a-bustling-black-enclave-east-austin-residents-make-a-suburban-exodus

- Meerow, S. Pajouhesh, P., & Miller, T. R. (2019). Social equity in urban resilience planning. Local Environment, 24(9), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1645103

- Meerow, S., & Mitchell, C.L. (2017). Weathering the storm: The politics of urban climate change adaptation planning. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(11), 2619–2627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17735225

- Meerow, S., & Newell, J. P. (2016). Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geography, 40, 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1206395

- Meerow, S., & Newell, J. P. (2017). Spatial planning for multifunctional green infrastructure: Growing resilience in Detroit. Landscape and Urban Planning, 159, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.005

- Mees, H. (2017). Local governments in the driving seat? A comparative analysis of public and private responsibilities for adaptation to climate change in European and North American cities. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(4), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1223540

- Mees, H. L. P., Driessen, P. P. J., & Runhaar, H. A. C. (2015). “Cool” governance of a “hot” climate issue: Public and private responsibilities for the protection of vulnerable citizens against extreme heat. Regional Environmental Change, 15, 1065–1079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0681-1

- Mendelsohn, R., Dinar, A., & Williams, L. (2006). The distrbutional impact of climate change on rich and poor countries. Environment and Development Economics, 11(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X05002755

- Meschkat, E. (2018). Racial equity tool: Cleveland climate action plan. Sustainability: The Journal of Record, 11(6), 280–283. https://doi.org/10.1089/sus.2018.29149.toolkit

- Nabatchi, T. (2012) Putting the public back in public values research: Designing participation to identify and respond to values. Public Administration Review, 72(5), 699–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02544.x

- Nowell, L.S., Norris, J.M., & White, D.E. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Office of Sustainability Environmental Sustainability Task Force. (2014). Sustainable Providence. https://www.providenceri.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Sustainability-Providence.pdf

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., & Duan, N. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Utilization-focused evaluation checklist. https://wmich.edu/sites/default/files/attachments/u350/2014/UFE_checklist_2013.pdf

- Pendall, R., with Hedman, C. (2015). Worlds apart: Inequality between America’s most and least affluent neighborhoods. Urban Institute. www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/2000288-Worlds-Apart-Inequality-between-Americas-Most-and-Least-Affluent-Neighborhoods.pdf

- Preston, I., Banks, N., Hargreaves, K., Kazmierczak, A., Lucas, K., Mayne, R., et al. (2014). Climate change and social justice: An evidence review. JRF Joseph Rowntree Foundation. https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/climate-change-social-justice-full.pdf

- Quick, K. S., & Feldman, M. S. (2011). Distinguishing participation and inclusion. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31(3), 272–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X11410979

- Reames, T.G., Reiner, M.A., & Stacey, M.B. (2018). An incandescent truth: Disparities in energy efficient lighting availability and prices in an urban U.S. county. Applied Energy. V. 218, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.02.143

- Rhode Island Department of Health. (2018). Asthma in Rhode Island: Greater Providence area. Division of Community Health & Equity. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/546d61b5e4b049f0b10b95c5/t/5c65f25353450a82b2e0a4e9/1550185066098/Community+asthma+presentation+-+Greater+Providence+Area.pdf

- Rosen, J., & Painter, G. (2019). From citizen control to co-poduction. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1618727

- Rosenzweig, C., Solecki, W. D., Hammer, S. A., & Mehrotra, S. (2011). Climate change and cities: First assessment report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press.

- Rosenzweig, C., Solecki, W., Romero-Lankao, P., Mehrotra, S., Dhakah, S., & Ibrahim, S. A. (2018). Climate change and cities: Second assessment report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press.

- Ross, H., Baldwin, C., & Carter, R. W. (2016). Subtle implications: Public participation versus community engagement in environmental decision-making. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 23(2), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2016.1194588

- Russo, C., & Pattison, A. (2016). Climate action planning (CAP): An intersectional approach to the urban equity dilemma. In P. Godrey & D. Torres (Eds.), Systemic crises of global climate change: Intersections of race, class and gender (pp. 250–262). Routledge.

- Schively Slotterback, C., & Lauria, M. (2019). Building a foundation for public engagement in planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1616985

- Schlosberg, D., Collins L. B., & Niemeyer, S. (2017). Adaptation policy and community discourse: Risk, vulnerability, and just transformation. Environmental Politics, 26, 413–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1287628

- Schlosberg, D., & Collins, L. B. (2014). From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. WIREs Climate Change, 5(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.275

- Schlosberg, D. (2013). Theorising environmental justice: The expanding sphere of a discourse. Environmental Politics, 22, 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755387

- Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford University Press.

- Schrock, G., Basset, E. M., & Green, J. (2015). Pursuing equity and justice in a changing climate: Assessing equity in local climate and sustainability plans in US cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15580022

- Shandas, V., & Messer, W. B. (2008). Fostering green communities through civic engagement: Community-based environmental stewardship in the Portland area. Journal of the American Planning Association, 74(4), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360802291265

- Sheppard, S. R., Shaw, A., Flanders, D., Burch, S., Wiek, A., Carmichael, J., Robinson, J., & Cohen, S. (2011). Future visioning of local climate change: A framework for community engagement and planning with scenarios and visualization. Futures, 43(4), 400–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2011.01.009

- Shi, L., Chu, E., Anguelovski, I., Aylett, A., Debats, J., Goh, K., Schenk, T., Seto, K. C., Dodman, D., Roberts, D., Roberts, J. T., & VanDeveer, S. D. (2016). Roadmap towards justice in urban climate adaptation research. Nature Climate Change, 6, 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2841

- Simons, H. (2009). Case study research in practice. Sage.

- Smock, K Consulting. (2014). Poverty in Multnomah County. Multnomah County Department of County Human Services.

- Sovacool, B., Heffron, R., McCauley, D., & Goldthau, A. (2016). Energy decisions reframed as justice and ethical concerns. Nature Energy, 1, 16024. https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.24

- Stephens, J. C. (2019) Energy democracy: Redistributing power to the people through renewable transformation. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 61(2), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2019.1564212

- Stuart, G. (2017, February 14). What is the spectrum of public participation? Sustaining Community. https://sustainingcommunity.wordpress.com/2017/02/14/spectrum-of-public-participation/

- Sustainable Cleveland. (2013). Cleveland climate action plan—Building thriving and healthy heighborhoods. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/sustainablecleveland/pages/149/attachments/original/1461798511/Cleveland_Climate_Action_Plan.pdf?1461798511

- Sustainable Cleveland. (2018). Cleveland climate action plan 2018 update—Building thriving and resilient neighborhoods for all. https://www.sustainablecleveland.org/climate_action

- Szulecki, K., & Overland, I. (2020). Energy democracy as a process, an outcome, and a goal: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 69, 101768. https://www.cssn.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/1-s2.0-S2214629620303431-main.pdf https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101768

- Texas Office of Sustainability. (2015). Austin community climate plan. http://austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Sustainability/OOS_AustinClimatePlan_032915_SinglePages.pdf

- Tol, R. S. J., Downing, T. E., Kuik, O. J., & Smith, J. B. (2004). Distributional aspects of climate change impacts. Global Environmental Change, 14(3), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.04.007

- Tritter, J. Q., & McCallum, A. (2006). The snakes and ladders of user involvement: Moving beyond Arnstein. Health Policy, 76(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.05.008

- Uittenbroek, C. J., Mees, H. L., Hegger, D. L., & Drissen, P. P. (2019). The design of public participation: Who participates, when and how? Insights in climate adaptation planning from the Netherlands. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(14), 2529–2547. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1569503

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2017). Public participation guide: Selecting the right level of public participation. https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/public-participation-guide-selecting-right-level-public-participation

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & T. Young. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Waud, A. (2018, April 3). The urban heart of a just transition: How cities plan for social justice in climate action. Metropolitics. https://metropolitics.org/The-Urban-Heart-of-a-Just-Transition-How-Cities-Plan-for-Social-Justice-in.html

- Williams-Rajee, D. & Evans, T. (2016). The integration of equity in the Portland/Multnomah County 2015 climate action plan. Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability and Multnomah County.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and method (5th ed.). Sage.

- York, D., & Jarrah, A. (2020). Community resilience planning and clean energy initiatives: A review of city-led efforts for energy efficiency and renewable energy. American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

- Yuen, T., Yurkovich, E., Grabowski, L., & Altshuler, B. (2017). Guide to equitable, community-driven climate preparedness planning. Urban Sustainability Directors Network. https://www.usdn.org/uploads/cms/documents/usdn_guide_to_equitable_community-driven_climate_preparedness-_high_res.pdf

- Zachmann, G., Fredriksson, G., & Claeys, G. (2018). the distributional effects of climate policies. Bruegel. https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Bruegel_Blueprint_28_final1.pdf

- Zehr, D. (2020). Inheriting inequality. Austin American-Statesman. https://projects.statesman.com/news/economic-mobility/