Abstract

Many planning and health collaborations name the built environment as an “upstream” factor for health disparities. Though some give mention to the structural dimensions of inequality (e.g., unequal distribution of income, discriminatory policies and practices), these are rarely the focus of planning–health study. Though this narrower approach is pragmatic, it restricts the policymaking discourse to potential built environment solutions that tend not to affect structural inequalities. I argue that equity planning can help focus research and practice on the root causes of unhealthy urban forms and unequal opportunities and engage directly with the challenging redistributional questions they require.

The Built Environment Is Not an Upstream Factor

In the last 2 decades, the phrase social determinants of health has become common parlance among academics, professionals, and politicians. The concept acknowledges that the roots of health gradients or disparities emanate from an unequal distribution of the resources that allow individuals to live without the burden of disease (Marmot, Citation2003). For good reasons, the social determinants concept has been embraced by those working at the intersections of urban planning and public health, who recognize the undeniable associations between unequal places and unequal health outcomes. The structural factors that drive unequal resource distribution, including educational disparities, low wages, and discrimination, are familiar to practitioners who must often respond to their consequences.

At the same time, public health frameworks like socioecological models of health behavior and the health impact pyramid highlighted the built environment as a locus of intervention for alleviating health disparities and explicitly called planners into collaboration (Frieden, Citation2010; Sallis et al., Citation2015). These models frequently invoked the metaphor of a river to emphasize how health outcomes are the downstream manifestation of intersecting upstream factors, like tributaries converging to form a channel. By creating healthier built environments upstream, practitioners might interrupt the development of downstream disease.

Treating the built environment as an upstream determinant of health allows planners to stay in more comfortable paradigms of research and practice. In research, correlations and coefficients are used to explain the health impacts of a new supermarket or park, while models control for underlying socioeconomic factors rather than investigate them directly. In practice, tools like planning processes, zoning, or development incentives offer familiar resources for modifying the built environment in tactical ways (Webb, Citation2018). Yet, by calling the built environment an upstream factor, planning–health collaborators set aside the structural factors that explain how it came to be: overcrowded housing, segregated neighborhoods, and poor access to healthy foods are symptoms of deeper problems.

Here I argue that equity planning offers an urgently needed lens for planning–health collaborations to achieve greater impact. I briefly summarize the problems caused by giving only tacit acknowledgment to the social determinants of health, drawing upon theories from political science and planning to show how this prevents deeper investigations into how unhealthy built environments persist. I provide two case studies of planning and public health collaboration that reveal some of the perils of working without equity at the center, namely, the tendency to focus research and practice on narrow built environment outcomes rather than the underlying structural causes of those conditions. Finally, with equity planning in mind, I highlight opportunities to break from these past tendencies. By being “activist, risk-taking in style, and redistributive in objective,” to borrow Norman Krumholz’s (Citation1982, p. 172) description of the equity planner, planners might refocus research and practice on the causes of unhealthy and unequal built environments, not just their well-documented consequences.

The Risks of Downstream Research and Policy

Theorists have offered perspectives on how setting aside the structural causes of health inequities may be pragmatic and even politically advantageous, though ultimately unhelpful in improving health outcomes. Political scientist Julia Lynch (Citation2017, Citation2020) has argued that the health inequalities concept has been a useful rhetorical tool to signal awareness and concern while avoiding contentious conversations about root causes. Lynch drew upon the experiences of European nations to investigate how the “health inequalities problem frame” emerged and has been used in public policy (Lynch, Citation2017, p. 653). She suggested that the Overton window—a concept describing the bounds of what is politically acceptable and feasible—has shifted to avoid taking action on the structures that underlie inequalities and has adopted a heavily medicalized focus on behavior. Governments benefit from an opportunity-focused language of social determinants without mentioning the riskier proposition of resource redistribution, and borrow from existing policy toolkits rather than explore new ones. Lynch concluded that this framing makes it even more difficult to make progress on either health or social inequalities (Lynch, Citation2020).

Planning scholars have voiced similar concerns. Laura Wolf-Powers (Citation2014) has suggested that community development projects can be oriented toward any of three theories of action: norms, markets, or justice. Norms-based interventions address individual or group behaviors that are seen as problematic, whereas market-oriented projects seek to correct market failures and create opportunities for private investment in underresourced communities. Efforts to reverse injustice are often the result of concerted activism and organizing and seek to redistribute power and resources or establish new rights or protections for vulnerable populations. Like Lynch, Wolf-Powers showed how certain kinds of approaches fail to address root causes of inequalities. Whereas planning theorists have long described notions of justice-oriented community development that are rhetorically powerful (i.e., equity planning, equity mapping, the just city, the right to the city; see Fainstein, Citation2014; Krumholz, Citation1986; Marcuse, Citation2009; Marcuse et al., Citation2009; Talen, Citation1998), Wolf-Powers noted that planning practice tends to be most comfortable operating in norms- and markets-oriented paradigms.

As Lynch (Citation2017, Citation2020) identified with health inequalities, these community development debates are notable for what they treat as taboo. When justice theories of action are de-emphasized, tensions go unexamined: “It is often simplest for practitioners—and for the funders and government agencies that support them—to rationalize away conflict between competing theories of action, preserving community development as a big tent capable of accommodating a variety of actors with distinct motives” (Wolf-Powers, Citation2014, p. 214). Where theories come into conflict, justice can be marginalized with “damaging consequences” (Wolf-Powers, Citation2014, p. 214). In the case of many planning and public health collaborations, focusing on the built environment as a locus of intervention often leads to solutions that are oriented toward markets (e.g., development incentives) or norms (e.g., incentives to change individuals’ behavior).

Case Studies

To illustrate how a built environment focus allowed structural inequalities to remain unaddressed in research and policy, I describe two collaborations between urban planning and public health, one early in the professions’ histories and the other more recent. I contend these are not unfortunate errors but rather part of a larger pattern to planning–health collaborations, some of which has been described by Jason Corburn (Citation2004, Citation2007), like the use of scientific rationalization to achieve built environment objectives.

Before turning to these examples, I clarify several normative positions. First, I take seriously the claims by practitioners and researchers that they were interested in understanding linkages between the built environment and health and hoped to alleviate health disparities; I do not doubt their motives and recognize that numerous motivations underlie policy debates, only some of which are stated explicitly. Related, I acknowledge the influence of racism, including inaccurate claims by medical and social science communities about racial differences (Roberts, Citation2009) and the use of planning tools to achieve segregationist aims (Ross & Leigh, Citation2000; von Hoffman, Citation2000). By accepting an interest in health disparities, I do not mean to obscure this broader context but instead hope to show how avoiding discussions of root causes presented opportunities for both implicit and explicit forms of bias to influence thinking about place and health.

Case 1: Early Collaboration—Improving Housing for Health

Modern scholars have often used the example of urban renewal to urge planning–public health collaborators to remember harms wrought by earlier partnerships (Corburn, Citation2004, Citation2007; Lopez, Citation2009). The upheavals caused by urban renewal policies were rationalized, in part, by a collaborative innovation to assess the healthfulness of housing and built environments on a neighborhood scale. Inspired successes of urban sanitary reforms, which reduced the prevalence of communicable diseases that had ravaged cities, and from major regulatory achievements on public water supplies and food retail, early 20th-century planners and public health officials looked for new ways to eradicate unhealthy living conditions (American Public Health Association [APHA], 1945). This was emphasized by leaders of the APHA: “The slum of today is no longer a hot-bed of cholera and typhus fever as it was seventy-five years ago. It remains, however, one of the major obstacles to that physical and emotional and social vigor and efficiency and satisfaction which we conceive as the health objective of the future” (APHA, Citation1945, p. 9).

Slum upgrading and clearance programs provided one avenue for eradicating “unhealthy” buildings and urban forms. However, city redevelopment officials were challenged by the prospect of assessing entire neighborhoods at once, rather than the piecemeal practice of responding to individual violations or deficiencies. In response, APHA, in partnership with city planners and local housing authorities, published in 1945 what today might be called a data-driven or evidence-based approach to measuring housing quality, with the goal of identifying neighborhoods for repair or demolition. In documentation explaining the “APHA technique,” its developers emphasized the multisectoral nature of the problem and potential collaboration across “health departments, housing authorities and local planning bodies” and reported findings from pilot testing in New Haven (CT; APHA, Citation1945, p. 10).

The technique centered on a field assessment tool to be administered by trained staff that included “objective measurable” items related to deficiencies in building facilities, maintenance, and occupancy (APHA, Citation1945, p. 18). Each of these deficiencies was thought to influence some aspect of human health, like exposure to sunlight and fresh air, cleanliness, or lack of crowding. The tool was also a statement on the insufficiency of the 1901 Tenement House Act to provide and maintain healthy urban housing; only two of the nine deficiencies measured by the technique were covered by the Act. Beyond housing, the technique also assessed the neighborhood environment, noting detrimental qualities like the presence of mixed residential, industrial, and business land uses; street traffic and railroads; or the lack of parks or playgrounds. Notably, the technique’s designers found these characteristics harder to integrate into the overall scoring for housing, though they still emphasized their contextual importance in deciding the fate of various neighborhoods.

The technique’s designers also recognized the risk that housing improvements could drive up rents to unaffordable levels. Rather than address this problem directly, it was used to justify demolition and redevelopment over “modernizing” substandard housing: “In theory, some such buildings can be modernized. Experience is that few of them will be, and that if they are the rents will rise beyond the reach of those now living in them” (APHA, Citation1945, p. 36). The designers also wrote of the unequal treatment of African Americans by landlords across the United States, noting the extortionate rents charged as a factor of the limits placed on Black buyers and renters by racist policies and practices and unscrupulous landlords seeking to profit from this discrimination (APHA, Citation1945). Yet this recognition did little to prevent further harms to African American communities through urban renewal and slum clearance (Fullilove, Citation2001, Citation2004; Hyra, Citation2012). As with gentrification concerns, the observation of overt and structural racism, though essential to the problem of unequal housing and unequal health, was not deeply explored by the technique’s creators.

This collaboration reveals the risks of ignoring root causes, even within a detailed, evidence-informed assessment. In several instances, structural issues were identified but left unaddressed. The Overton window for the APHA technique was firmly fixed on physical housing. Problems of unaffordability (owing to poverty and wages), lackluster enforcement of tenant protections, and racist lending and renting practices were acknowledged as influential but fell outside the window. The omission of these upstream structural issues is consequential: The analyses that used the APHA technique could only illuminate downstream issues.

Case 2: Recent Initiatives—Improving Food Environments for Health

In the early 2000s, planning and public health researchers began discussing food deserts, or communities without access to full-service supermarkets, picking up a thread of urban research from the United Kingdom (Wrigley, Citation2002) and responding, in part, to the work of Pothukuchi and Kaufman (Citation2000), who urged planners to pay greater attention to their role in food systems. Many studies documented associations between physical proximity to supermarkets and health disparities, including diet quality and the prevalence of diet-related diseases. Tools were developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to locate food deserts, enabling federal, state, and local officials to quantify the problem and consider spatial policies to attract new retailers.Footnote1 Though much was made of food access as an upstream determinant of health, the policy discourse was firmly fixed at a relatively narrow set of familiar solutions: tax credits and development incentives, usually with a firm insistence that these financial supports should be temporary (Chrisinger, Citation2016).

To the discipline’s credit, planning scholars and practitioners were quick to question the food desert concept. Raja and colleagues (2008) challenged the term’s deficit orientation and claimed it obfuscated historical legacies (such as redlining), focused on a particular solution (the suburban-style supermarket), and gave no attention to grassroots efforts or alternative forms of community development. Raja also called for planners to abandon the food desert label entirely and replace it with more accurate terms, like food apartheid, coined by activist and urban farmer Karen Washington, that reflect the exclusionary structures that create unhealthy food environments (Brones, Citation2018). Wolf-Powers (Citation2015) also urged attention to root causes, asking whether food deserts were perhaps more accurately wage deserts, where persistent poverty and inequality shaped and limited the landscape of economic opportunity, including retail businesses like supermarkets. Others pointed to the fraught and sometimes paternalistic narratives that food access measures seemed to imply (Hillier & Chrisinger, Citation2016; Rosenberg & Cohen, Citation2017; Usher, Citation2015).

With an Overton window fixed on supermarkets, the food desert metaphor largely sidestepped broader debates about poverty and inequality and issues regarding food justice (Raja et al., Citation2008). Questions of long-term sustainability and community engagement were not commonly emphasized beyond the initial development of new stores (Brinkley et al., Citation2019). As in the case of the APHA technique, healthy food financing solutions gave only passing acknowledgment to the risks of gentrification (Anguelovski, Citation2015). Still, as Wolf-Powers (Citation2017) noted, the power of the food desert metaphor is unmistakable because it mobilized an array of community development initiatives. Existing community development tools were repackaged to achieve supermarket-oriented aims in communities that lacked these amenities. Nevertheless, few projects improved community health, and among those that did, gains were very modest (Abeykoon et al., Citation2017).

Shifting the Window Toward Equity

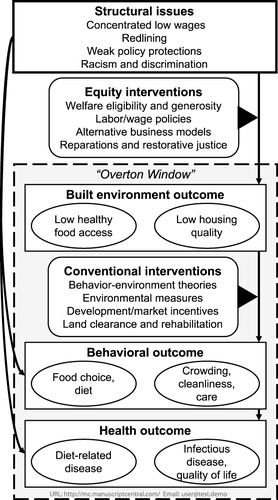

Despite substantial inertia, it is possible to shift the window of policy options toward more equity-oriented ends. For example, Cohen and Ilieva (Citation2021) described New York City’s efforts to promote healthy food access and showed that discourses can be reframed from downstream disparities to upstream root causes, like housing, labor, and education, as well as the foundational role of welfare programs to the goal of food justice and healthy food environments. The concerted efforts of activists, researchers, and practitioners dedicated to addressing upstream factors have, over time, broadened the policy discourse far beyond distances to supermarkets. New York City is perhaps the largest example of successes in upstream reframing, but it is hardly alone. Raja and colleagues have also described equity-oriented food systems advances in Buffalo (NY) and other U.S. cities through their Growing Food Connections project (Clark et al., Citation2017; Raja et al., Citation2014). imagines other equity-focused opportunities outside the traditional Overton window and illustrates how these might interrupt the development of unequal and unhealthy built environments.

Figure 1. Conventional and equity-focused interventions to improve the built environment and health.

Public participation may also have a role to play in shifting the window toward structural determinants. In both the case of urban renewal and healthy food financing, when and where public participation happened, better community outcomes could occur (Brinkley et al., Citation2019; Wilson, Citation1963). Although engaging communities in the development of potential equity-focused solutions is certainly best practice, this may force researchers and practitioners to rethink their outcomes of interest, expand the scope of their inquiries, or de-emphasize or discard preconceived health metrics. Still, greater participation does not guarantee equity; indeed, Sherry Arnstein’s seminal ladder of citizen participation was, in part, a critical response to the weak public engagement efforts of urban renewal (Arnstein, Citation1969).

Lessons for Planners

How, then, should planners act? To deliberately focus attention on root causes, planners might consider a variety of existing frameworks for thinking about and operationalizing equity. Planning history—both domestically and internationally—offers a rich theoretical literature on how equity might be centered in practice (i.e., equity planning, the just city, the right to the city; see Fainstein, Citation2014; Krumholz, Citation1986; Marcuse, Citation2009). Equity planners are “redistributive in objective” (Krumholz, Citation1982, p. 172) and use “research, analytical, and organizing skills to influence opinion, mobilize underrepresented constituencies, and advance and perhaps implement policies and programs” that achieve equity aims (Metzger, Citation1996, p. 112). Armed with the practical planning toolkit—comprehensive and capital plans, equity mapping (Talen, Citation1998), exactions, proffers, zoning codes, and building ordinances (Lucy, Citation1981, Citation1994)—coupled with the municipal policy levers of real property taxation and eminent domain, practitioners have powerful distributional options.

Taking up these tools can be challenging to the generally “cautious and conservative” planning profession (Krumholz, Citation1982, p. 172), but simply because upstream interventions are viewed as politically unpalatable does not mean they should not be examined. As Fainstein (Citation2009) noted, utopian planning concepts, though unattainable, can be useful models to push planners and policymakers. The recent example of food access in New York City showed how concerted attention to the root causes of unhealthy built environments can refocus policy agendas. Importantly, by keeping analyses centered on upstream inequities that cause downstream health disparities, the built environment can be rightly considered a piece of a broader puzzle rather than a main determinant of poor health. As Lynch (Citation2017, Citation2020) argued, this truth-telling is valuable because it forces difficult conversations about redistribution that must happen if health inequities are ever to be addressed. The lens of equity planning requires that planning–health collaborations directly engage with these challenging factors and guard against a drift toward comfortable, narrow analyses of the built environment.

Earlier equity planning movements have provided inspiration on how to identify, plan, and advocate for intervention on upstream factors via redistributive means, and previous planning–public health collaborations offer insights into the risks of narrowly focusing analyses and interventions on the built environment. Thus, a new generation of equity planners (including students, practitioners, educators, and researchers) might bring several unique perspectives to future planning–health endeavors:

Participation and engagement. How are measures developed to define a problem, and do they imply certain solutions? The tendency toward quantification and scientific rationalization has been a theme of planning–health collaborations (Corburn, Citation2007), including urban renewal and healthy food financing, where measures reinforced environmental solutions like slum clearance or supermarket development. Attention must be paid to this impulse. With experience in authentic forms of participation and engagement (e.g., neighborhood planning processes), planners might help counteract this pattern and elicit root causes and community priorities.

Local needs, conditions, and histories. Which kinds of evidence matter, how should they be collected, and how will they be prioritized in decision making? How do power and marginalization factor into our understanding of what is possible? Planners play a role in shaping the Overton windows for policymaking, and different values and frames will yield different problem definitions, solution sets, and decision-making processes. Planners have a unique perspective on local needs and conditions, including those already established by local advocates and activists, as well as problematic development and policy histories like redlining and restrictive covenants that may warrant redress.

Government and policy. How might policies that are fundamentally more redistributive affect built environment and health outcomes? Is there a role for advocacy efforts toward policy changes required to address root causes of inequality? Planners have a unique view on the varieties of local government that might affect structural factors, as well as the departments and agencies that are implicated in possible interventions. Planners should remember Krumholz’s (Citation1982) suggestion to look beyond the planning commission to achieve equity objectives. Even when planners cannot unilaterally implement reforms, they help ensure that policy dialogues stay focused on upstream factors through research and advocacy.

Conclusion

History has shown that social upheavals have been key catalysts for discussions about equity and advocacy planning and redistributive policy agendas (Metzger, Citation1996). As planners face inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and those brought to broader public consciousness following the summer of racial reckoning in 2020, an ambitious planning and public health agenda targeting structural factors is desperately needed. In this context, equity planning may have new opportunities. By remembering the risks of collaboration between the planning and public health fields, researchers and practitioners might reorient future interdisciplinary endeavors toward more effective and lasting change. In the words of Krumholz (Citation1982): “We will never know how much more we can do until we try” (p. 173).

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the thoughtful comments and suggestions from three anonymous reviewers, Special Issue Guest Editor Nisha Botchwey, and Editor Ann Forsyth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin W. Chrisinger

BENJAMIN W. CHRISINGER ([email protected]) is an associate professor in the Department of Social Policy and Intervention at the University of Oxford.

Notes

1 Notably, the U.S. Department of Agriculture stopped promoting the food desert label (instead providing access measures based on transportation, income, and physical proximity to supermarkets), though these measures were instrumental in defining both the problem and solution regarding supermarket retail.

References

- Abeykoon, A. H., Engler-Stringer, R., & Muhajarine, N. (2017). Health-related outcomes of new grocery store interventions: A systematic review. Public Health Nutrition, 20(12), 2236–2248. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000933

- American Public Health Association (APHA). (1945). An appraisal method for measuring the quality of housing: A yardstick for health officers, housing officials and planners…. Committee on the Hygiene of Housing. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000225282

- Anguelovski, I. (2015). Healthy food stores, greenlining and food gentrification: Contesting new forms of privilege, displacement and locally unwanted land uses in racially mixed neighborhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1209–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12299

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Brinkley, C., Glennie, C., Chrisinger, B., & Flores, J. (2019). If you build it with them, they will come”: What makes a supermarket intervention successful in a food desert? Journal of Public Affairs, 19(3), e1863. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1863

- Brones, A. (2018, May 7). Karen Washington: It’s not a food desert, it’s food apartheid. Guernica. https://www.guernicamag.com/karen-washington-its-not-a-food-desert-its-food-apartheid/

- Chrisinger, B. W. (2016). Taking stock of new supermarkets in food deserts: Patterns in development, financing, and health promotion (Working Paper No. 04; p. 16). Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Community Development Investment Center.

- Clark, J. K., Freedgood, J., Irish, A., Hodgson, K., & Raja, S. (2017). Fail to include, plan to exclude: Reflections on local governments’ readiness for building equitable community food systems. Built Environment, 43(3), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.43.3.315/

- Cohen, N., & Ilieva, R. T. (2021). Expanding the boundaries of food policy: The turn to equity in New York City. Food Policy, 103, 102012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.102012

- Corburn, J. (2004). Confronting the challenges in reconnecting urban planning and public health. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 541–546. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.4.541

- Corburn, J. (2007). Reconnecting with our roots: American urban planning and public health in the twenty-first century. Urban Affairs Review, 42(5), 688–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087406296390

- Fainstein, S. S. (2009). Spatial justice and planning. Justice Spatiale/Spatial Justice, 1, 1–13.

- Fainstein, S. S. (2014). The just city. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 18(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2013.834643

- Frieden, T. R. (2010). A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 590–595. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652

- Fullilove, M. T. (2001). Root shock: The consequences of African American dispossession. Journal of Urban Health, 78(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.1.72

- Fullilove, M. T. (2004). Root shock: How tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America, and what we can do about it. One World/Ballantine Books.

- Hillier, A., & Chrisinger, B. W. (2016). The reality of urban “food deserts” and what low-income food shoppers really need. In J. L. Jackson Jr. (Ed.), Top ten social justice & policy issues for the 2016 presidential election. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hyra, D. S. (2012). Conceptualizing the new urban renewal: Comparing the past to the present. Urban Affairs Review, 48(4), 498–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411434905

- Krumholz, N. (1982). A retrospective view of equity planning Cleveland 1969–1979. Journal of the American Planning Association, 48(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944368208976535

- Krumholz, N. (1986). City planning for greater equity. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 3(4), 327–337.

- Lopez, R. P. (2009). Public health, the APHA, and urban renewal. American Journal of Public Health, 99(9), 1603–1611. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.150136

- Lucy, W. (1981). Equity and planning For local services. Journal of the American Planning Association, 47(4), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944368108976526

- Lucy, W. (1994). If planning includes too much, maybe it should include more. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369408975589

- Lynch, J. (2017). Reframing inequality? The health inequalities turn as a dangerous frame shift. Journal of Public Health, 39(4), 653–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw140

- Lynch, J. (2020). Regimes of inequality: The political economy of health and wealth. Cambridge University Press.

- Marcuse, P. (2009). From critical urban theory to the right to the city. City, 13(2–3), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810902982177

- Marcuse, P., Connolly, J., Novy, J., Olivo, I., Potter, C., & Steil, J. (2009). Searching for the just city: Debates in urban theory and practice. Routledge.

- Marmot, M. G. (2003). Understanding social inequalities in health. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3 Suppl), S9–S23. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2003.0070

- Metzger, J. T. (1996). The theory and practice of equity planning: An annotated bibliography. Journal of Planning Literature, 11(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/088541229601100106

- Pothukuchi, K., & Kaufman, J. L. (2000). The food system. Journal of the American Planning Association, 66(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360008976093

- Raja, S., Ma, C., & Yadav, P. (2008). Beyond food deserts: Measuring and mapping racial disparities in neighborhood food environments. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 27(4), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08317461

- Raja, S., Picard, D., Baek, S., & Delgado, C. (2014). Rustbelt radicalism: A decade of food systems planning practice in Buffalo, New York (USA). Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 4(4), 1–189. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2014.044.015

- Roberts, S. (2009). Infectious fear: Politics, disease, and the health effects of segregation. University of North Carolina Press.

- Rosenberg, N. A., & Cohen, N. (2017). Let them eat kale: The misplaced narrative of food access colloquium. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 45(4), 1091–1120. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2742&context=ulj

- Ross, C. L., & Leigh, N. G. (2000). Planning, urban revitalization, and the inner city: An exploration of structural racism. Journal of Planning Literature, 14(3), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854120022092719

- Sallis, J. F., Owen, N., & Fisher, E. (2015). Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5, 43–64.

- Talen, E. (1998). Visualizing fairness: Equity maps for planners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 64(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369808975954

- Usher, K. M. (2015). Valuing all knowledges through an expanded definition of access. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 5(4), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.018

- von Hoffman, A. (2000). A study in contradictions: The origins and legacy of the Housing Act of 1949. Housing Policy Debate, 11(2), 299–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2000.9521370

- Webb, D. (2018). Tactical urbanism: Delineating a critical praxis. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1406130

- Wilson, J. Q. (1963). Planning and politics: Citizen participation in urban renewal. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 29(4), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366308978073

- Wolf-Powers, L. (2014). Understanding community development in a “theory of action” framework: Norms, markets, justice. Planning Theory & Practice, 15(2), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2014.905621

- Wolf-Powers, L. (2015). Food deserts and wage deserts: The importance of metaphor in policy and activism. Metropolitics. http://www.metropolitiques.eu/Food-Deserts-and-Wage-Deserts-The.html

- Wolf‐Powers, L. (2017). Food deserts and real-estate-led social policy. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(3), 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12515

- Wrigley, N. (2002). Food deserts” in British cities: Policy context and research priorities. Urban Studies, 39(11), 2029–2040. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098022000011344