Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

Shelter is a necessity, yet approximately 17 out of every 10,000 people in the United States are unhoused. Public attention to homelessness has centered on individuals sitting and sleeping in public spaces. However, as many as 50% of the unsheltered live in vehicles. For people sleeping in vehicles, finding a safe place to park is an ongoing challenge, further complicated by the growing number of ordinances restricting vehicular dwelling. We drew on point-in-time count data from the Los Angeles (CA) Homeless Services Authority to examine spatial patterns of vehicular homelessness in Los Angeles from 2016 to 2020. We tested the relationship between the presence of vehicle regulations and the number of people sleeping in vehicles. Although the data likely underestimated vehicular homelessness, we found that ordinances directly reduced the number of people living in vehicles in particular census tracts. On average, cities with citywide and overnight bans had greater impacts on people sleeping in vehicles than cities with less restrictive ordinances. However, the indirect effects in neighboring tracts were stronger and demonstrate the role of these ordinances in simply shifting the vehicular homeless between areas.

Takeaway for practice

Given the slow pace of delivering permanent housing for people experiencing homelessness, cities should reduce the harm and precariousness of living in vehicles. Strategies to do this include the reform of punitive vehicle towing and vehicle dwelling regulations. Safe parking programs can provide individuals with a safe place to park their vehicles at night, offer ancillary services, and deter harassment from neighborhood residents and the police. Longer term, transformative change will require additional policies and programs to place people into permanently affordable housing.

The right to shelter is a fundamental human right, yet approximately 17 out of every 10,000 people in the United States are houseless (National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2021). This figure has increased substantially in recent years, in parallel with the growing affordable housing crisis, rising unemployment and poverty rates, and the lack of needed services to address mental illness and substance abuse (Flaming et al., Citation2021; National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2021; National Homelessness Law Center, Citation2021; Padgett et al., Citation2016). Much of the public attention to homelessness has centered on unhoused individuals in public spaces and parks and the development of large homeless encampments (DeVerteuil et al., Citation2009; Herring, Citation2014; Herring & Lutz, Citation2015; Mitchell, Citation2003; N. Smith, Citation1996; Sparks, Citation2017). Resistance to this highly visible and growing population group has engendered numerous spatial and property rights–oriented conflicts (Blomley, Citation2011; Loukaitou-Sideris & Ehrenfeucht, Citation2009; Mitchell & Staeheli, Citation2006).

There has been far less attention to the high percentage of unsheltered individuals living in vehicles: cars, vans, and recreational vehicles (Moody, Citation2020; Pollard, Citation2018). From reported estimates in West Coast cities, the percentage of the unsheltered population living in vehicles has ranged from 25% in Seattle (WA; Quinn, Citation2018) to almost 50% in Los Angeles (CA; Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority [LAHSA], Citation2020). In response to the increase in vehicular homelessness, a growing number of cities have adopted municipal ordinances restricting vehicular dwellings. The National Homelessness Law Center has tracked the increase in municipal laws criminalizing the homeless in 187 cities (Bauman, Rosen et al., Citation2019). From 2006 to 2019, 64 cities in their sample enacted new laws restricting vehicle dwelling, a 213% increase; by 2019, half of all cities in their sample had one or more of such laws (Bauman, Bal et al., Citation2019). The presence and enforcement of these restrictions potentially influence where the vehicular homeless population lives and their movement across neighborhoods in search of safe places to park.

In this study, we explored the spatial impacts of vehicular dwelling restrictions by asking two questions. First, how do cities regulate vehicular homelessness? Second, what is the relationship between vehicular dwelling restrictions and the presence of people sleeping in their vehicles? To answer the first question, we conducted a content analysis of 85 cities’ municipal ordinances to characterize the regulatory environment that, we hypothesized, affects vehicular homelessness. To answer the second question, we used data from the region’s annual point-in-time (PIT) count and examined the spatial patterns of vehicular homelessness. We then tested whether vehicular restrictions were effective in their unstated goal of reducing and potentially eliminating vehicular homelessness. The findings have implications for efforts to regulate and otherwise address the needs of those living in vehicles.

First, we review the literature on vehicular homelessness: its growth, geographic location, and regulation. Second, we describe our data and methods. Third, we present our findings in two sections: one on vehicle ordinances and the second on the relationship between vehicle ordinances and the number of people sleeping in vehicles. Fourth, we conclude with policy recommendations to reduce the harm and precariousness of living in vehicles while recognizing the need for policies and services to enable successful transitions to permanent housing.

Vehicular Homelessness: Growth and Regulation

As of January 2020, more than a half a million people (580,466) in the United States were homeless (National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2021). Of this group, almost 40% (226,080) were unsheltered individuals and families sleeping in locations such as sidewalks, vehicles, and parks not intended for this purpose. In recent years, this population has grown—a 29% increase since 2014—in parallel with the growing affordable housing crisis, rising unemployment and poverty rates, the lack of dependable mental and physical health services, and governance decisions to prioritize shelters over permanent housing (Chrystal et al., Citation2015; Flaming et al., Citation2021; Hanratty, Citation2017; Herring, Citation2021).

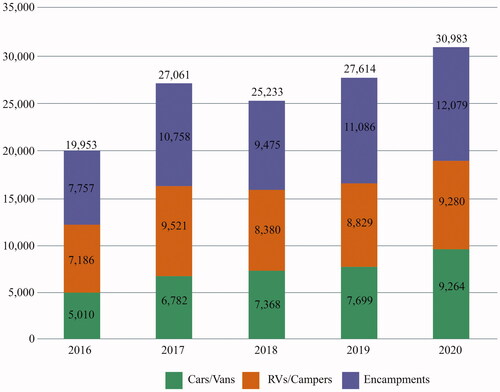

A high and growing percentage of unsheltered individuals live in cars, vans, or recreational vehicles, both nationally and in Los Angeles (LA). In the Los Angeles Continuum of Care (a service provider geography that includes 85 of the 88 cities in Los Angeles County), the number of persons living in recreational vehicles (RVs)/campers, vans, and cars increased 55% from 2016 to 2020, from 12,200 to 18,900 (; LAHSA, Citation2020). Data have shown that lower income individuals, single women, and families with children represented a large portion of the homeless population living in vehicles in LA (Flaming et al., Citation2018).

There are very few studies on vehicular homelessness. However, existing research has suggested that vehicles provide some benefits relative to the alternatives: sleeping in public spaces (sidewalks, parks) or reliance on temporary shelters. Compared with sleeping in public spaces, vehicles provide safer, more stable, and secure shelter (Lyons-Warren & Lowery, Citation2020; Pollard, Citation2018; Quinn, Citation2018). Vehicles also afford a secure place to store one’s belongings. These advantages are particularly important to the growing numbers of unhoused women and children, some of whom have experienced homelessness due to domestic violence (Baker et al., Citation2010; Bassuk et al., Citation2001). Further, ethnographies have highlighted the role of vehicles in enabling the homeless to avoid street violence, policing, and criminalization (Craft, Citation2020; Wakin, Citation2014), some of which are associated with increased regulations against sleeping in public spaces (Bauman, Rosen et al., Citation2019; Darrah-Okike et al., Citation2018; Dozier, Citation2019; Herring et al., Citation2019; Wakin, Citation2008).

Unhoused people have described how living in vehicles is a rational and more appealing choice than the shelter system because of its strict rules and curfews or residents with other problematic behavior (Wakin, Citation2014; Wasserman, Citation2014). The organization Invisible People educates the public about homelessness through storytelling. Recently, it reported the story of one vehicle dweller who stated, “We went down to a shelter in downtown, but it was bad—heroin, crack, smells. [My son] looked at me and said, ‘Dad, get me out of here. It’s spooky’” (Invisible People, Citation2018). Further, a study of homeless people’s resistance to shelters in Florida found that the location of facilities—near the central business district—raised significant safety concerns, including crime both on the streets and in the shelters (Donley & Wright, Citation2012). The preference for vehicle dwelling appears to have grown in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic because vehicles provide social distancing that reduces the likelihood of contracting the virus compared with sleeping in overcrowded homeless shelters (Moody, Citation2020).

Finally, assuming they are operational, vehicles enhance people’s access to jobs, schools, services, and shopping (Shen, Citation2001). Outside of the densest urban neighborhoods where transit service levels are high, cars provide greater access to destinations within a reasonable travel time compared with other transportation modes (Blumenberg & Ong, Citation2001). In many neighborhoods outside of central business districts, services for the homeless and other low-income families are limited (Allard, Citation2004; Allard & Roth, Citation2010; Wolch et al., Citation1993). The access benefits of cars, vans, RVs, and campers provide yet another reason for unhoused people to hold on to their vehicles.

Despite these relative advantages, vehicle living can be difficult. Vehicular dwellings have cramped conditions without access to running water, electricity, or restrooms (Wakin, Citation2005, Citation2014). In addition, their presence has incited neighborhood opposition, hostility among local residents and businesses concerned about problems with trash and dumping human waste, the use of scarce parking spaces, and increasing crime (Dear & Gleeson, Citation1991; Fuller et al., Citation2019). Neighborhood complaints have motivated the growth in ordinances criminalizing those sleeping in their vehicles (Pruss & Cheng, Citation2020). These ordinances have made it increasingly difficult for those living in their vehicles to locate safe places to park, elevating fears of being towed, ticketed, or interacting with the police (Lyons-Warren & Lowery, Citation2020; McElwain et al., Citation2021; Pruss & Cheng, Citation2020; Wakin, Citation2014).

The relationship between antivehicular dwelling ordinances and the spatial location of people living in vehicles has not been investigated. Qualitative research has suggested that these ordinances contribute to the dispersal of vehicular homelessness (Cerveny & Baur, Citation2020; Pruss, Citation2012, Citation2019; So et al., Citation2016). Although restrictions on where and when people can sleep may not result in citations, their increased enforcement has pushed people into a life of constant movement in search of safe spaces to park (Pruss & Cheng, Citation2020; Wakin, Citation2014). Finally, to avoid detection, vehicular dwellers have parked in specific places: under highways, in industrial zones, and adjacent to large parks and campsites (Pruss, Citation2012; So et al., Citation2016; Wakin, Citation2014).

Analyzing the Spatial Dimensions of Vehicular Homelessness

We asked two primary research questions: First, how do cities regulate vehicular homelessness? Second, what is the relationship between vehicular ordinances and people living in vehicles, controlling for other factors predicted to influence this relationship (e.g., population density, income, land use, the presence of freeway overpasses)?

Our geographic scope was the Los Angeles Continuum of Care (Los Angeles CoC). The CoC has the largest unsheltered population in the country and includes 85 of the 88 cities in Los Angeles County as well as the unincorporated areas. The cities of Glendale, Long Beach, and Pasadena are their own CoCs and were excluded from our analysis. To answer the two research questions, we drew from four data types: descriptions of vehicle dwelling ordinances (American Legal Publishing, Citation2022; Code Publishing Co., Citation2022; General Code, Citation2022; Municode, Citation2022; Quality Code Publishing, Citation2022), data from the annual PIT homeless count (LAHSA, Citation2020), neighborhood built environment characteristics (City of Los Angeles, Citation2020; Los Angeles County, Citation2021), and population characteristics (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2021).

We categorized the municipal codes into citywide bans on sleeping in a vehicle, overnight parking restrictions, and permit zones, following the guidance of the National Law Center on Homelessness and Policy’s “No Safe Place” report (Bauman, Rosen et al., Citation2019). Based on the ordinances in LA cities, we added two additional categories: time restrictions and zoning ordinances. Cities often had multiple ordinances targeting RVs, bans on certain streets, and 3-day time restrictions. If a city had adopted multiple ordinances, we assigned the most restrictive ordinance to that city. For example, the city of Inglewood targets all vehicles with a 72-hour restriction (time), but it also bans RV dwellings citywide (citywide). Therefore, we categorized census tracts within Inglewood with a citywide ban.

We developed a spatial regression model to test the relationship between the presence (or absence) of vehicular ordinances by type and the number of people sleeping in vehicles by census tract. The models controlled for regulation type and land use (parks per square mile; industrial square footage; presence of a freeway; the number of safe parking program [SPP] lots; the number of churches, services, and shelters per census tract; socioeconomic and population characteristics such as median household income and population per square mile; unsheltered nonvehicular homeless population density per square mile; and census tract size in square miles).

We used an inverse distance spatial weighting matrix to define the spatial relationships across tracts. This matrix assumed that census tracts close to one another have more influence on the number of people sleeping in a vehicle than those further away. The spatial regression included a dependent spatial lag variable to capture a spatial relationship that people living in vehicles in one tract were influenced by surrounding tracts. The model output produced average direct and indirect impact estimates that allowed us to understand the relative strength of these two predictions.

There are a few important limitations to our analysis. First, the PIT counts of people experiencing homelessness, especially for people living in vehicles, undercounted this population (C. Smith & Castañeda-Tinoco, Citation2019). PIT counts, in general, have underestimated homelessness by relying on volunteers with good intentions but limited expertise, applying a narrow definition of homelessness predicated on visual evidence, which is especially difficult for people who live in vehicles who try to hide in plain sight (National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty, Citation2017). If the undercount is evenly distributed across census tracts, it would not affect our analysis; unfortunately, there are no existing data on the spatial dimensions of the undercount.

Second, it was difficult to categorize cities by their vehicle dwelling ordinances. For example, multiple, more limited ordinances may, in combination, be as restrictive as an outright ban. We assumed, however, that the adoption of a vehicular dwelling ban (of any type) reflected a city’s intensity of purpose and therefore was a more significant deterrent to vehicular homelessness.

Third, zonal regulations typically restrict vehicle dwelling on a street-by-street basis. Our unit of analysis was the census tract, which does not account for smaller scale regulations and effectively may overestimate the restrictions on a particular tract. For example, the City of Los Angeles amended Ordinance 85.02 to zone particular streets where overnight dwelling is banned next to streets where it is permitted. We assigned all census tracts within the city of Los Angeles with a “zone” restriction when certain tracts may in fact allow vehicular dwelling.

Finally, one further limitation is that we did not account for differences in enforcement that likely vary between or across neighborhoods within cities. For example, two cities may have similar ordinances, but if one jurisdiction is more actively enforcing their ordinance, we would expect to see greater compliance. To analyze enforcement, future studies could interview people who have experienced enforcement of vehicular restrictions and those who carry out enforcement. Understanding the role of enforcement is important but outside the scope of this study.

Regulation of Vehicular Homelessness in Los Angeles

In California, three state codes influenced the adoption and implementation of ordinances restricting sleeping in vehicles in California cities. The California Vehicle Code (CVC) 22507.5 (a) (Citation1959) permits cities to ban overnight commercial vehicles in residential zones from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. In addition, CVC 10.64.010 pursuant to Section 22660 states that any accumulation of “abandoned, wrecked, dismantled or inoperative vehicles or parts thereof” can be removed by the police or an authorized person. Last, CVC 22651(k) (Citation1959) mandates that a peace officer “…may remove a vehicle located within the territorial limits in which the officer or employee may act, under the following circumstances: (k) if a vehicle is parked or left standing upon a highway for 72 or more consecutive hours in violation of a local ordinance authorizing removal.”

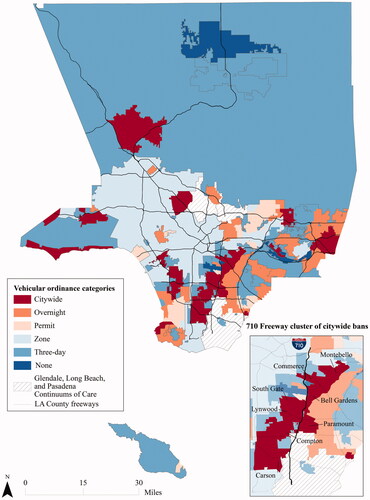

Cities within the Los Angeles CoC implemented additional regulations to restrict and criminalize sleeping in cars, vans, and RVs/campers. As shows, all but four cities in the Los Angeles CoC (81 of the 85 cities) adopted some type of restriction of vehicular dwellings.Footnote1 Bell, Huntington Park, Industry, and Lancaster were the four cities in the region without any restrictions on sleeping in a vehicle. These cities had a smaller share of vehicular homelessness compared with their overall unsheltered population.

Table 1 Vehicular homelessness, population, and land use variables in 85 cities by ordinance type (from most to least restrictive).

Cities regulated vehicular homelessness in five ways: citywide bans, overnight restrictions, permit parking, zone restrictions, and time-limited parking. We discuss each of these types below and, in Technical Appendix A, provide a list of cities in the Los Angeles CoC with the title, type, date, and code language of their vehicular ordinance.

Citywide and overnight bans on vehicle dwelling were the most restrictive and widespread. More than a quarter of all cities instituted citywide bans. Citywide bans prohibit dwelling in a vehicle at all times of the day on all streets of the city. Twenty-two cities possessed comprehensive bans. For example, in Azusa (Citation2010), a mid-sized suburban city in the eastern San Gabriel Valley, Section 74-439.1 of their ban read:

It shall be unlawful for any person to lodge or sleep, on or about any automobile, truck, trailer, camper, recreational vehicle or similar vehicle in or on any public street, public park areas, right-of-way, or public or private parking lot or other public property within the City’s jurisdictional boundaries.

Anyone found in violation of this ordinance was subjected to a $100 fine, with a second offense being $250 and subsequent citations worth $500.

Twenty-six cities (31%) codified overnight restrictions. Fifteen of these regulations explicitly targeted oversize vehicles such as campers and RVs (∼20%), whereas the remainder targeted sleeping in all types of vehicles. Overnight bans targeted nighttime dwelling (e.g., 2:00 a.m. to 6:00 a.m.) and typically targeted oversize vehicles like campers and RVs. The city of La Cañada Flintridge, a small, hilly town just 15 miles north of downtown LA, implemented section 8.07.010 in Citation2000, which stated:

Between the hours of two a.m. and six a.m., it shall be unlawful for any person to park any motor vehicle on any alley, street, public right-of-way, publicly owned and/or operated parking lot, other publicly owned property including, but not limited to, parks, school grounds or open space, or to park on any private parking lot without the expressed permission of the private property owner, for the purpose of sleeping in the motor vehicle. (Ord. 304 Sec. 1, 2000)

The penalty for violating this overnight restriction was $50, $100 for a second infraction, and finally $250 for each additional violation.

Permit parking does not explicitly ban vehicular dwelling but requires documentation proving residency, which likely makes it difficult for the unhoused living in vehicles. Twelve cities adopted this ordinance type. For example, Santa Monica’s overnight parking permit ordinance (3.12.900, Section b, Subsection 1) required, “The name, residence, address, and telephone number of the applicant” (Citation2018).

Zone bans restrict vehicle dwellings in residential areas (e.g., Agoura Hills), on particular streets (e.g., Rosemead), and/or overnight in specific business zones (e.g., Monterey Park). Nine cities had this type of ordinance. LA, the city with the largest proportion of people sleeping in vehicles, was one of the nine and had the most complex zonal ordinance. Called the “Safe Streets” initiative (formerly Ordinance 85.02), the city bans vehicular dwelling on specific streets, in some cases restricting dwelling at night and others restricting vehicle dwelling at all times. Vehicular dwelling is banned on approximately 39% of all city streets and nearly half of city streets (49%) overnight.

Three-day ordinances were the least restrictive. They required individuals to move their vehicles from a specific parking space every 3 days to avoid tickets or towing. Following the adoption of a similar statewide law, 12 cities enacted time-limited parking ordinances. For example, the city of El Segundo’s Code 8-5-6 (Citation2017) stated, “Except as otherwise provided in this chapter, no person who owns or has possession, custody or control of any vehicle may park the vehicle upon any street or alley for more than a consecutive period of seventy-two (72) hours.”

It was difficult to determine why cities adopted these policies and the factors that explained the type of policy they adopted. To explore adoption patterns, we first investigated whether there was an association between the recent uptick in vehicular homelessness and the adoption of vehicle ordinances by type. The evidence was mixed. Most of the ordinances (62%) were enacted prior to 2016. However, some cities recently updated their ordinances, adopting more restrictive regulations. For example, eight cities passed citywide bans after 2016: Calabasas (2017), Carson and Inglewood (2018), Compton (2019), Commerce and Lynwood (2020), and Lawndale and Paramount (2021).

The demographic characteristics of cities likely influenced the adoption of vehicular dwelling ordinances. As shows, cities with more restrictive ordinances had higher average median household incomes, older residents, a larger percentage of single-family detached housing units, and less industrial land use. These data suggested that policymakers may be influenced by the advocacy of higher income homeowners concerned about the effect of homelessness on their quality of life and property values. Referring to the city of Los Angeles, a 2019 editorial in the Los Angeles Times highlighted this motivation: “These parking bans are granted by the City Council at the request of individual council members to placate upset property owners” (“Unless Homeless People in Cars and RVs Have Places to Park, They’ll End Up Sleeping on Sidewalks,” Citation2019).

shows a concentration of citywide bans in smaller municipalities located along the 710 Freeway corridor. Compared with other cities with citywide bans, this group of cities had relatively low household incomes but slightly higher industrial land use as well as the freeway itself. These data suggested a role for built environment characteristics that may be specific to vehicular dwelling. Policies may reinforce this. For example, the City of Los Angeles’s 2017 ordinance specifically banned people from sleeping in their vehicles in residential neighborhoods (and near parks, schools, and daycare centers) and affirmatively allowed car-dwelling in commercial and industrial areas. The clustering of cities with bans could also suggest policy transfers between adjacent and similar communities.

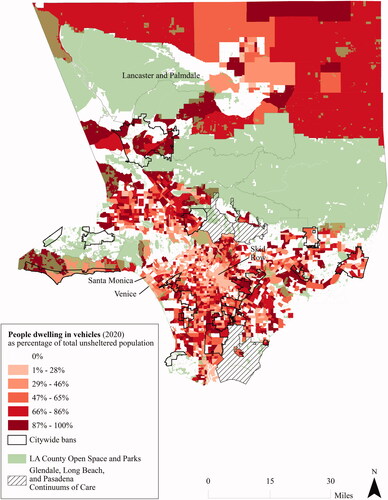

The Spatial Location of Vehicular Homelessness

From 2016 to 2020, vehicular homelessness became more dispersed. shows vehicular homelessness as a percentage of the total unsheltered homeless population by tract. The map did not suggest a clear spatial pattern of vehicular homelessness. People sleeping in vehicles were not concentrated in locations such as Skid Row, where homeless services tend to cluster, or in beach neighborhoods (Santa Monica and Venice) in proximity to public facilities (e.g., bathrooms, showers). The map also shows a lack of concentration in outlying suburban areas in north Los Angeles County (cities of Palmdale and Lancaster).

Figure 3. Vehicular homelessness by census tract (2020) as a percentage of total unsheltered population.

Spatial statistics supported the random spatial distribution of vehicular homelessness. We calculated Moran’s I statistics for 2016 and 2020 to assess the level and changes in the concentration of people sleeping in vehicles by census tract. The test produced an index from −1 (no clustering) to 1 (total clustering). In 2016 the index was 0.02, whereas in 2020 the index was 0.05. The measures indicated a random distribution of vehicular homelessness. However, in 2016, approximately half of all census tracts in the Los Angeles CoC had people sleeping in vehicles; by 2020, this number had increased to two-thirds of all census tracts. Over time, therefore, vehicular homelessness has become more widespread in parallel with the growth in total unsheltered homelessness.

As we noted previously, vehicular restrictions were widespread. As of 2020, 95% (14,972 people) of people living in vehicles were in census tracts with some type of restriction on vehicular dwelling. However, although vehicle dwellings were present in tracts with overnight and citywide bans, the data showed fewer vehicular homeless in tracts with overnight bans.

includes the model results, predicting the spatial association between regulatory type and the number of people sleeping in vehicles. The model did not have strong explanatory power (R2 = 0.074), likely reflecting the difficulty of both counting and predicting the location of vehicular homelessness. Nonetheless, several significant relationships emerged.

Table 2 Average direct, indirect, and total impacts of factors on vehicular homelessness, 2020.

The data showed some co-location across different homeless population groups. We found a positive association between the number of people living in tents and the number of people living in vehicles; however, the relationship was not strong. The correlation coefficient between these two variables for 2020 was 0.33.

Moreover, the greater the census tract area size and industrial land use, the higher the number of people sleeping in vehicles. In contrast, higher population density and median household income were associated with less vehicular homelessness. This relationship may have reflected neighborhoods in which residents were able to lobby for permit parking or overnight dwelling bans. The model also showed that a higher number of services and shelters were associated with a smaller number of people sleeping in vehicles. This relationship may be due to the greater availability of homeless housing or, perhaps, to the difficulty of parking vehicles in downtown areas where tents, homeless shelters, and services concentrate.

The direct effects of vehicular restrictions were negative. In other words, census tracts with the most restrictions on vehicle dwelling contained fewer people sleeping in vehicles than other tracts with fewer or no restrictions. In contrast, the indirect effects were stronger and positive. If a particular census tract had a citywide or overnight ban, neighboring census tracts had more people sleeping in their vehicle than other tracts. Therefore, the total effect of regulations across all census tracts (combining direct and indirect effects) was positively associated with the number of people sleeping in vehicles. We replicated the same model using data for previous years (2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019) with largely consistent findings.

The model, however, did not pick up an effect for permit requirements and zone ordinances. This finding is likely due, in part, to our coarse measurement of these regulations. We assume that citywide and overnight bans may serve as deterrents. Unhoused individuals may avoid cities with citywide bans to avoid tickets and towing. Avoiding cities with comprehensive bans may be relatively easy, because only 22 (26%) cities, representing only 6% of the total land area in the Los Angeles CoC, have banned vehicular dwelling outright. Nevertheless, enforcement of ordinances likely necessitates movement and instability to other streets. Forced relocation can be hard on families, disrupting access to employment, schools, social networks, and/or services. As we noted above, although bans may have deterred dwelling in any particular location, their total effect (direct + indirect) is positive.

Finally, the number of people living in vehicles has continued to increase, even in cities with citywide bans. shows the trends in vehicular homelessness for cities that passed citywide bans after 2016. Though the sample is small, six out of eight cities experienced an increase in people sleeping in their vehicles after the implementation of a citywide ban.

Table 3 Trends in the number of people sleeping in vehicles for cities that passed a citywide ban after 2016.

Regulation and Vehicular Homelessness

In sum, what did we find? Vehicle dwelling restrictions in LA were widespread. With the increase in vehicular homelessness, cities appeared to be adopting increasingly restrictive regulations, as evidenced by the eight cities in the region that recently implemented citywide vehicular dwelling bans. It is difficult to explain why cities adopted these policies and why they chose a particular regulatory mechanism. However, the data suggest that these decisions were influenced by the growth in vehicular homelessness as well as other city characteristics (e.g., the presence of lower income, less politically influential residents; industrial land use; and the presence of freeways).

The relationship between vehicle dwelling restrictions and the spatial location of the vehicular homeless was complex. Neighborhoods with restrictive vehicle dwelling ordinances had slightly lower populations of people living in vehicles than other neighborhoods. However, these ordinances did not eliminate vehicular homelessness entirely; moreover, they appeared to simply shift vehicle dwellers to adjacent communities. Therefore, although vehicle dwelling bans potentially reduced the population of vehicular homelessness in any one area, they did not address the underlying problem: the lack of safe shelter and long-term housing for those in need.

Reducing Criminalization and Expanding Options for the Vehicular Homeless Population

Scholars have long argued that homelessness is a housing problem (Wright & Rubin, Citation1991). Although the passage of two measures in the city and county of Los Angeles (Measures H and HHH) contributed to this goal by generating increased funding for homeless services and permanent housing,Footnote2 the pace of these efforts has not matched the scale of the problem. Local neighborhood opposition to shelters and affordable housing construction has remained a significant deterrent to these policies and programs (Herring, Citation2019; Reese et al., Citation2010; Vitale, Citation2010).

Given the slow pace of delivering permanent housing for people experiencing homelessness, we recommend that cities proactively reduce the harm and precariousness of living in vehicles. Cities should reject policies that may actively harm people experiencing homelessness, including the enforcement of municipal ordinances restricting vehicular dwelling and other forms of public dwelling, often resulting in the dispossession of property and displacement (Hennigan & Speer, Citation2019; Murphy, Citation2019; Tinoco, Citation2019). Changes in municipal towing policy would also benefit the vehicular homeless population. In the city of Los Angeles, government agencies towed almost 10,000 vehicles in a month largely due to unpaid parking tickets, lapsed vehicle registrations, and enforcement of the 72-hour rule (Western Center on Law & Poverty, Citation2019). Many individuals living in their vehicles have lost them due to debt collection and registration tows, ultimately finding themselves on the street (Flaming et al., Citation2018). As of early February 2022, the City of Los Angeles had temporarily halted the towing of vehicles with more than five unpaid tickets (Uranga, Citation2022). The City of San Francisco adopted a different approach, implementing towing discounts and no-fee payment plans (Lyons-Warren & Lowery, Citation2020). Accommodating vehicular dwellings may help improve the use of streets and parking infrastructure for alternative uses. Benefits of on-street parking include reduced vehicular speeds, fewer fatal pedestrian collisions, and a more enjoyable public realm (Marshall et al., Citation2008).

A growing number of cities have adopted SPPs as another approach to harm reduction. Programs like SPPs (i.e., homeless housing) in LA County that offer safe, secure shelter and services for the unhoused have reduced unsheltered homelessness and crime while increasing adjacent property values (Cohen, Citation2019). Often organized in partnership with local community organizations such as churches, SPPs provide people living in vehicles with a legal place to sleep overnight, an interim solution until they can transition into permanent housing. A recent nationwide review of SPPs found these programs are a “stabilizing force” in the lives of people who live in their vehicles, as well as in the communities where they reside (McElwain et al., Citation2021, p. 1).

Santa Barbara’s New Beginnings serves as a national example of a successful SPP (Wakin, Citation2014). New Beginnings primarily relies on partnerships with organizations that are willing to transform their parking lots into quasi–trailer park communities. Recently expanding from the city to the county, New Beginnings has trained prospective partners in best practices to maintain safe lots, which has resulted in no incidents or damage to lots and neighborhoods. This program also provides food and services to unhoused individuals and has transitioned approximately 1,000 people into permanent housing through rapid rehousing (New Beginnings, Citation2021).

The City of Los Angeles adopted an SPP in 2016 in collaboration with churches and other social service and nonprofit organizations. Parking sites are monitored to ensure safety, providing a safe space that allows those experiencing vehicular homelessness to comply with street parking regulations without fear of ticketing and to have access to hygiene and sanitation facilities. LA’s SPP also connects people to life-sustaining services. In addition to a designated parking space, program participants can participate in a Coordinated Entry System assessment, receive referrals to community resources, and gain access to an outreach worker and financial assistance (LAHSA, Citation2021). As of 2021, safe parking expanded to Los Angeles County; there are currently 17 sites with 439 spaces available that can serve approximately 508 people (McElwain et al., Citation2021). This number is 10,000 spaces short of accommodating the 11,124 vehicles counted as part of the 2020 PIT count.

SPPs present opportunities to implement planning interventions that convert widespread parking infrastructure into alternative housing options (Barter, Citation2010; Chester et al., Citation2015). In Los Angeles County, 14% of land is dedicated to parking infrastructure (Chester et al., Citation2015). Converting underused, off-street surface lots into alternative housing can provide people with a safer place to sleep, receive services, and access opportunities for housing. The City of Los Angeles owns 11,831 total public parking spaces (City of Los Angeles, Citation2020). If just 13% of these spaces were converted to safe parking, it could accommodate about a quarter of the vehicular homeless in the city (SafeParkingLA, Citation2021). As of 2010, there were approximately 18.6 million parking spaces in Los Angeles County (Chester et al., Citation2015). Therefore, the County would need to use just 9,511 spaces (or 0.05% of total supply) to serve the remaining population of vehicle dwellers.

However, the adoption of SPPs can be difficult and, unless cities are careful, lead to unintended consequences. Much like other concentrations of homelessness (e.g., encampments, temporary shelters), SPPs have provoked neighborhood opposition (Vera, Citation2021; Welsh, Citation2021). They also have been used to justify increased enforcement of vehicle dwelling ordinances. For example, in LA, city councilmembers and neighborhood councils have justified increased enforcement of vehicle dwelling regulations to encourage people to use these lots (Blumenfeld & Bonin, Citation2018; Englander & Rodriguez, Citation2017; Fight Back, Venice, Citation2018).

Even with an increase in safe parking spaces, it is likely that additional outreach is required to ensure that people living in vehicles have a path toward permanent housing. Given this reality, we recommend city staff and service providers work together to conduct outreach to people living in vehicles. These efforts can target streets or neighborhoods with high concentrations of vehicle dwellers, establish relationships, and connect people living in cars with housing and related services that can put them on a path to permanent housing, like those services offered at SPP sites.

Policies to mitigate the challenges associated with vehicular dwelling will not address the deeper structural issues that produce homelessness, such as wealth inequality, racial disparities, and unaffordable housing. However, these programs—if carefully implemented—can help address the short-term needs of those living in vehicles. In addition, SPPs can provide the necessary contacts and services to enable successful transitions to permanent housing. Cities ought to use their transportation policies and assets to provide stability and safety on the road to a better future for people experiencing homelessness.

RESEARCH SUPPORT

Research presented in this paper was made possible through funding received by the University of California Institute of Transportation Studies (UC ITS) from the State of California through the Public Transportation Account and the Road Repair and Accountability Act of 2017 (Senate Bill 1). The UC ITS is a network of faculty, research and administrative staff, and students dedicated to advancing the state of the art in transportation engineering, planning, and policy for the people of California. Established by the Legislature in 1947, the UC ITS has branches at UC Berkeley, UC Davis, UC Irvine, and UCLA.

Technical Appendix

Download PDF (131.8 KB)SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental data for this article can be found on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christopher Giamarino

CHRISTOPHER GIAMARINO ([email protected]) is a doctoral student in urban planning at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA).

Madeline Brozen

MADELINE BROZEN ([email protected]) is deputy director of the Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies at UCLA.

Evelyn Blumenberg

EVELYN BLUMENBERG ([email protected]) is a professor of urban planning at UCLA.

Notes

1 Although the LA CoC contains unincorporated areas that follow a 3-day restriction from CVC 22651(k), they were not included in this content analysis. In 2020, there were 3,512 people living in vehicles in unincorporated areas.

2 Passed in 2016, HHH was a bond measure to fund the development of supportive housing in the city of Los Angeles. In 2017, LA County voters passed Measure H, a quarter-cent sales tax that funds supportive services throughout LA County, including efforts to prevent homelessness, to coordinate entry systems and outreach services, and to subsidize supportive and affordable housing initiatives.

References

- Allard, S. W. (2004). Access to social services: The changing urban geography of poverty and service provision. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/access-to-social-services-the-changing-urban-geography-of-poverty-and-service-provision/

- Allard, S. W., & Roth, B. (2010). Strained suburbs: The social service challenges of rising suburban poverty. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1007_suburban_poverty_allard_roth.pdf

- American Legal Publishing. (2022). Home. https://www.amlegal.com/

- Azusa, California Code of Ordinances, Ord. No. 10-O8, § 1 (2010).

- Baker, C. K., Billhardt, K. A., Warren, J., Rollins, C., & Glass, N. E. (2010). Domestic violence, housing instability, and homelessness: A review of housing policies and program practices for meeting the needs of survivors. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(6), 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2010.07.005

- Barter, P. A. (2010). Off-street parking policy without parking requirements: A need for market fostering and regulation. Transport Reviews, 30(5), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640903216958

- Bassuk, E. L., Perloff, J. N., & Dawson, R. (2001). Multiply homeless families: The insidious impact of violence. Housing Policy Debate, 12(2), 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2001.9521407

- Bauman, T., Bal, R., Barr, K., Foscarinis, M., Ryan, B., & Tars, E. (2019). Housing not handcuffs 2019: Ending the criminalization of homelessness in U.S. cities. National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty.

- Bauman, T., Rosen, J., Tars, E., Foscarinis, M., Fernandez, J., Robin, C., Sowa, E., Maskin, M., Cortemeglia, C., & Nicholes, H. (2019). No safe place: The criminalization of homelessness in U.S. cities. National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. https://nlchp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/No_Safe_Place.pdf

- Blomley, N. (2011). Rights of passage: Sidewalks and the regulation of public flow. Routledge.

- Blumenberg, E., & Ong, P. (2001). Cars, buses, and jobs: Welfare participants and employment access in Los Angeles. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1756(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.3141/1756-03

- California Vehicle Code, 9 § 22507.5(a) (1959).

- California Vehicle Code, 10 § 22651 (k) (1959).

- Cerveny, L. K., & Baur, J. W. R. (2020). Homelessness and nonrecreational camping on national forests and grasslands in the United States: Law enforcement perspectives and regional trends. Journal of Forestry, 118(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1093/jofore/fvz065

- Chester, M., Fraser, A., Matute, J., Flower, C., & Pendyala, R. (2015). Parking infrastructure: A constraint on or opportunity for urban redevelopment? A study of Los Angeles County parking supply and growth. Journal of the American Planning Association, 81(4), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2015.1092879

- Chrystal, J. G., Glover, D. L., Young, A. S., Whelan, F., Austin, E. L., Johnson, N. K., Pollio, D. E., Holt, C. L., Stringfellow, E., Gordon, A. J., Kim, T. A., Daigle, S. G., Steward, J. L., & Kertesz, S. G. (2015). Experience of primary care among homeless individuals with mental health conditions. PLOS One, 10(2), e0117395 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117395

- City of Los Angeles. (2020). City of Los Angeles hub. http://geohub.lacity.org/

- Code Publishing Co. (2022). Code publishing company. https://www.codebook.com/

- Cohen, E. (2019). The effects of designated homeless housing sites on local communities: Evidence from Los Angeles County (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3513625). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3513625

- Craft, R. (2020). Home: A vehicle for resistance? Exploring emancipatory entanglements of “vehicle dwelling” in a changing policy context. Journal of Law and Society, 47(S2)S321–S338. https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12270

- Darrah-Okike, J., Soakai, S., Nakaoka, S., Dunson-Strane, T., & Umemoto, K. (2018). It was like I lost everything”: The harmful impacts of homeless-targeted policies. Housing Policy Debate, 28(4), 635–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1424723

- Dear, M., & Gleeson, B. (1991). Community attitudes toward the homeless. Urban Geography, 12(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.12.2.155

- DeVerteuil, G., May, J., & von Mahs, J. (2009). Complexity not collapse: Recasting the geographies of homelessness in a “punitive” age. Progress in Human Geography, 33(5), 646–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508104995

- Donley, A. M., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Safer outside: A qualitative exploration of homeless people’s resistance to homeless shelters. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 12(4), 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228932.2012.695645

- Dozier, D. (2019). Contested development: Homeless property, police reform, and resistance in Skid Row, LA. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(1), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12724

- El Segundo, CA Code of Ordinances, Ord. 1523 (2017).

- Fight Back, Venice. (2018). Homeless and poverty committee agenda 5-22-18:“Safe parking” LAMC 85.02.

- Flaming, D., Burns, P., & Carlen, J. (2018). Escape routes: Meta-analysis of homelessness in Los Angeles County. Economic Roundtable.

- Flaming, D., Orlando, A. W., Burns, P., Pickens, S. (2021). Locked out: Unemployment and homelessness in the Covid economy. Economic Roundtable. https://economicrt.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Locked-Out.pdf

- Fuller, T., Arango, T., Keene, L. (2019). As homelessness surges in California, so does a backlash. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/21/us/california-homeless-backlash.html

- General Code. (2022). General code: Forward-thinking digital codification solutions. https://www.generalcode.com/

- Hanratty, M. (2017). Do local economic conditions affect homelessness? Impact of area housing market factors, unemployment, and poverty on community homeless rates. Housing Policy Debate, 27(4), 640–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2017.1282885

- Hennigan, B., & Speer, J. (2019). Compassionate revanchism: The blurry geography of homelessness in the USA. Urban Studies, 56(5), 906–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018762012

- Herring, C. (2014). The new logics of homeless seclusion: Homeless encampments in America’s. City & Community, 13(4), 285–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12086

- Herring, C. (2019). Between street and shelter: Seclusion, exclusion, and the neutralization of poverty. In J. Flint & R. Powell (Eds.), Class, ethnicity and state in the polarized metropolis: Putting Wacquant to work. (pp. 281–305). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Herring, C. (2021). Complaint-oriented “services”: Shelters as tools for criminalizing homelessness. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 693(1), 264–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716221996703

- Herring, C., & Lutz, M. (2015). The roots and implications of the USA’s homeless tent cities. City, 19(5), 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1071114

- Herring, C., Yarbrough, D., & Alatorre, L. M. (2019). Pervasive penality: How the criminalization of poverty perpetuates homelessness. Social Problems, 67, 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spz004

- Invisible People. (2018). What people say about living in a car. https://invisiblepeople.tv/what-people-say-about-living-in-a-car/

- La Cañada Flintridge Municipal Code, Ord. 304 § 1 (2000).

- Los Angeles County. (2021). LAC open data. https://data.lacounty.gov/

- Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA). (2020). 2020 homeless count by service planning area. https://www.lahsa.org/data?id=40-2019-homeless-count-by-service-planning-area

- Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA). (2021). Safe parking program flyer. https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=4371-safe-parking-program-flyer.pdf

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., & Ehrenfeucht, R. (2009). Sidewalks: Conflict and negotiation over public space. MIT Press.

- Lyons-Warren, M., Lowery, L. (2020). Vehicular homelessness and the road to housing during and after COVID-19. National League of Cities. https://www.nlc.org/article/2020/05/28/vehicular-homelessness-and-the-road-to-housing-during-and-after-covid-19/

- Marshall, W. E., Garrick, N. W., & Hansen, G. (2008). Reassessing on-street parking. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2046(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.3141/2046-06

- McElwain, L., Schiele, D., Waheed, L. (2021). Smart practices for safe parking: A nationwide review of safe parking programs for people sheltering in vehicles. Report for the Center for Homeless Inquiries. https://priceschool.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Smart-Practices-for-Safe-Parking-USC-2021.pdf

- Mitchell, D. (2003). The right to the city: Social justice and the fight for public space. The Guilford Press.

- Mitchell, D., & Staeheli, L. A. (2006). Clean and safe? Property redevelopment, public space, and homelessness in downtown San Diego. In S. Low & N. Smith (Eds.), The politics of public space. (pp. 143–175). Routledge.

- Moody, C. (2020). Living in your car as a pandemic consumes your city: A “safe parking lot” in San Diego is a haven and a holding pattern during the coronavirus lockdown and an ongoing housing crisis. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/157314/living-car-pandemic-consumes-city

- Motion. (2017). Testimony of Mitchell Englander & Monica Rodriguez.

- Motion. (2018). Testimony of Bob Blumenfield and Mike Bonin.

- Municode. (2022). Home page. https://www.municode.com/home

- Murphy, E. (2019). Transportation and homelessness: A systematic review. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 28(2), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2019.1582202

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2021). State of homelessness: 2021 edition. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-2021/

- National Homelessness Law Center. (2021). Housing not handcuffs 2021: State law supplement. https://homelesslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-HNH-State-Crim-Supplement.pdf

- National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. (2017). Don’t count on it: How the HUD point-in-time count underestimates the homelessness crisis in America. https://homelesslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/HUD-PIT-report2017.pdf

- New Beginnings. (2021). Safe parking shelter and rapid rehousing program. https://sbnbcc.org/safe-parking/

- Padgett, D. K., Henwood, B. F., & Tsemberis, S. J. (2016). Housing first: Ending homelessness, transforming systems, and changing lives. Oxford University Press.

- Pollard, A. (2018). Living behind the wheel: More Americans are sleeping in their cars than ever before. Should cities make space for them? Slate. https://slate.com/business/2018/08/vehicular-homelessness-is-on-the-rise-should-cities-help-people-sleep-in-their-cars.html

- Pruss, G. (2012). Seattle vehicular residency research project: 2012 advisory report. Seattle University.

- Pruss, G. (2019). A home without a home: Vehicle residency and settled bias [PhD dissertation]. University of Washington. https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/44706

- Pruss, G., & Cheng, K. (2020). The “punitive push” on mobile homes. Cityscape, 22(2), 87–94. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/cityscpe/vol22num2/article6.html

- Quality Code Publishing. (2022). Quality code publishing. https://www.qcode.us/

- Quinn, M. (2018). “It’s the new form of affordable housing”: More people are living in their cars. Governing. https://www.governing.com/archive/gov-homeless-shelter-car.html

- Reese, E., DeVerteuil, G., & Thach, L. (2010). "Weak-Center" Gentrification and the Contradictions of Containment: deconcentrating poverty in downtown Los Angeles. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(2), 310–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00900.x

- SafeParkingLA. (2021). Safe Parking L.A. https://www.safeparkingla.org

- Santa Monica Municipal Code, Ord. No. 2587CCS § 1 (2018).

- Shen, Q. (2001). A spatial analysis of job openings and access in a U.S. metropolitan area. Journal of the American Planning Association, 67(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360108976355

- Smith, C., & Castañeda-Tinoco, E. (2019). Improving homeless point-in-time counts: Uncovering the marginally housed. Social Currents, 6(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329496518812451

- Smith, N. (1996). The new urban frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city. Routledge.

- So, J., MacDonald, S., Olson, J., Mansell, R. (2016). Living at the intersection: Laws and vehicle residency (No. 5). Homeless Rights Advocacy Project. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=hrap

- Sparks, T. (2017). Citizens without property: Informality and political agency in a Seattle, Washington homeless encampment. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16665360

- Tinoco, M. (2019). LA will spend $30M this year on homeless sweeps. Do they even work? LAist. https://laist.com/2019/04/10/homeless_sweeps_los_angeles_public_health.php

- Unless homeless people in cars and RVs have places to park, they’ll end up sleeping on sidewalks. (2019, August 5). Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-08-05/homeless-parking-problems

- Uranga, R. (2022, February 8). L.A. temporarily halts impounding of vehicles with 5 or more unpaid tickets. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-02-08/los-angeles-stops-impounding-cars-for-unpaid-tickets

- U.S. Census Bureau (2021). Explore census data. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/

- Vera, V. (2021). Neighbors decry safe parking site for San Jose homeless. San Jose Spotlight. https://sanjosespotlight.com/neighbors-decry-safe-parking-site-for-san-jose-homeless/

- Vitale, A. S. (2010). The Safer Cities Initiative and the removal of homeless: Reducing crime or promoting gentrification on Los Angeles’ Skid Row? Criminology & Public Policy, 9(4), 867–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2010.00677.x

- Wakin, M. (2005). Not sheltered, not homeless: RVs as makeshifts. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(8), 1013–1032. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764204274197

- Wakin, M. (2008). Using vehicles to challenge antisleeping ordinances. City & Community, 7(4), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2008.00269.x

- Wakin, M. (2014). Otherwise homeless: Vehicle living and the culture of homelessness. FirstForum Press.

- Wasserman, J. A. (2014). Stress among the homeless. In The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of health, illness, behavior, and society. (pp. 2295–2298). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118410868.wbehibs327

- Welsh, N. (2021, March 9). Santa Barbara’s safe parking program to expand as more lose housing amid pandemic. Santa Barbara Independent. https://www.independent.com/2021/03/09/santa-barbaras-safe-parking-program-to-expand-as-more-lose-housing-amid-pandemic/

- Western Center on Law & Poverty. (2019). Towed into debt: How towing practices in California punish poor people. https://wclp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/TowedIntoDebt.Report.pdf

- Wolch, J. R., Rahimian, A., & Koegel, P. (1993). Daily and periodic mobility patterns of the urban homeless*. The Professional Geographer, 45(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1993.00159.x

- Wright, J. S., & Rubin, B. A. (1991). Is homelessness a housing problem? Housing Policy Debate, 2(3), 937–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1991.9521078