Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

Protracted political conflicts disrupt people's lives, including their ability to feed themselves. Urban planning, operating within the ambit of the state, impacts food systems in conflict cities. We examine the confluence of planning and political misgovernance on food sovereignty in conflict cities. We do so by documenting the experiences of urban growers who cultivate, eat, and distribute indigenous greens (haakh) in the city of Srinagar in the Himalayan belt of Jammu and Kashmir, the site of a protracted conflict. Experiences of growers were analyzed within the context of the city's complex urban planning landscape. Empirical methods included qualitative interviews of urban growers (n = 40) and review of land use plans and policies. We found that haakh production ensured access to affordable, nutritious, and culturally celebrated greens for haakh growing households. That said, intersecting burdens from undemocratic governance and militarism (from India), weak forms of local planning (within Srinagar), and climate change threaten urban growers' work, and imperils food sovereignty. Completing a study in a conflict region was extraordinarily challenging. The study's generalizability is limited by its short duration and small sample size—the inductive findings set the stage for future research.

Takeaway for practice

Conflict cities are a reminder that urban planning is anything but technical. Planning curricula must prepare future planners for the politics of planning. Planners in conflict cities are in liminal positions—between the state and the public. To the best of their ability, planners in conflict cities such as Srinagar have to protect smallholder growers' control of their food system, especially over land and water. The monitoring, recording, and suspension of contested or undemocratic land conversions, land grabs, or land transfers without full consent of indigenous and local peoples ought to be a local and international policy priority.

Political conflict disrupts people’s lives and livelihoods, including their ability to feed themselves. In 2020, 155 million people in 55 countries/territories lived in conflict settings, which, among other things, also affected the magnitude and severity of global food crises (Food Security Information Network & Global Network Against Food Crises, Citation2021). Conflict undermines food security and food sovereignty. Food insecurity is the chronic lack of access to affordable, healthful, and culturally meaningful foods. A more expansive idea, food sovereignty is “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems” (Nyéléni Village, Citation2007). Food sovereignty demands peasants’ control of the food system rather than simply for a right to food (Patel, Citation2009; Vía La Campesina, Citation2003). As a profession that shapes land use and development, planning affects the underlying resources, such as land and water, that affect food sovereignty.

The record of state action on food sovereignty—especially in conflict settings—has been less than favorable. For example, state action has dispossessed indigenous peoples from food-related resources, including lands, forests, and waters (Desmarais et al., Citation2015). Planning decisions, as practiced under the ambit of the state, can protect (or undermine) food system resources such as land and water and ultimately threaten food security and food sovereignty in cities in crises. Planners need better theories and empirical precision to trace the pathways between planning and food sovereignty.

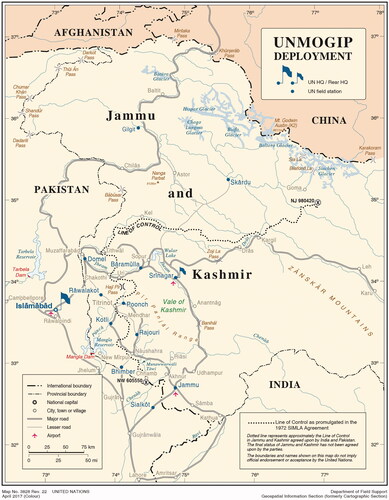

We trace how planning interfaces with broader political factors to influence food sovereignty in conflict cities. We focus on the case of Srinagar in Jammu and Kashmir (). Home to 1.3 million residents (Government of India, Citation2011), Srinagar is the capital of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), a Himalayan regionFootnote1 in the grips of a protracted state-enabled crisis.Footnote2 Curfews, arbitrary lockdowns, and checkpoints disrupt the functioning of the food system and interrupt people’s access to food markets for days and months at a time. Examining food systems in cities facing protracted crises reveals fundamental truths about the limits of planning, including in seemingly stable cities where hidden crises envelop particular neighborhoods or people.

We first situate this study within the literature, distilling critical conversations about and gaps in planning and food sovereignty in state-sanctioned conflict regions. We then discuss data and methods for our empirical analysis, which involved in-depth qualitative interviews of farmers interlaced with an analysis of plans and other policies used in governing our case context, Srinagar. We follow this section with our results, first providing an overview of the historically contingent nature and genesis of the protracted crisis in the J&K region, where Srinagar is the capital city. We later describe the experiences of urban farmers who grow an indigenous green, haakh (hāk), and how farming buffers growers and the city against food insecurity. Centering growers’ experiences, we analyze the impacts of planning (in Srinagar) and broader political governance (imposed from outside of J&K) on food sovereignty. We conclude with cautionary lessons for planners who wish to strengthen food systems and an urgent call for global attention to cities experiencing protracted crises.

Food Sovereignty in Cities Experiencing Protracted Crises: An Unaddressed Issue in Planning

A landmark article refocused planners’ attention on food systems (Pothukuchi & Kaufman, Citation2000), followed by a growth in scholarship illustrating the possibilities and limits of planning for food systems (Anguelovski, Citation2015; Cabannes & Marocchino, Citation2018; Pothukuchi, Citation2015, Citation2018; Raja et al., Citation2014, Citation2018; Raja & Whittaker, Citation2018). Increasingly, planning literature has called for centering equity and justice in food systems reform (Horst, Citation2017; Mui et al., Citation2021). Some scholars have critiqued technocratic planning as undermining cities’ food infrastructure, including subverting informal foodscapes through mallification and supermarket expansion in Global South contexts (Battersby, Citation2017). Others have drawn attention to the complicated role of dual land governance on urban agriculture in postcolonial cities (Frimpong Boamah et al., Citation2020).

Despite the growth of the food systems planning literature, discussions about the interplay between planning and food sovereignty remain limited. However, a larger body of literature outside of planning has critiqued the state’s role in food sovereignty. For instance, scholars have critiqued the aggressive commoditization of land, water, and other natural resources by the global capitalist food system and extractive practices of settler-colonial states, partly driven by international investors’ large-scale farmland acquisitions (Borras et al., Citation2011; Desmarais et al., Citation2015; Oliveira et al., Citation2021). Governments’ deregulatory policies, such as legislation welcoming development and speculation on agricultural land previously only available to local residents, have hastened land acquisition by outsiders (Desmarais et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, in the Global South, efforts to push for modern, commercial forms of agriculture in the guise of development have made smallholder farming precarious (Shrestha, Citation2008). Neoliberal policies have pushed for commercial farming over farming for self-reliance. Scholars have noted that institutionalizing food sovereignty through policy is challenging (Sharma & Daugbjerg, Citation2020).

On their part, communities have resisted the impact of power imbalances and failed governance systems on food sovereignty (Morrison, Citation2011). For example, indigenous peoples have restored relationships with the environment, transmitted ecological knowledge intergenerationally, and resisted colonial heteropatriarchal norms (Coté, Citation2016; Daigle, Citation2019; DiPrete Brown et al., Citation2020; Grey & Patel, Citation2015; Kepkiewicz & Dale, Citation2019; MacNeill, Citation2020; Manson, Citation2015; Morrison, Citation2011). Scholars have documented how the New Agriculture Movement in Bangladesh has encouraged communal sharing of knowledge and resources to cultivate health, countering the industrialized global food system (Mazhar et al., Citation2007).

Explicit discussions about the role of planning on food sovereignty in cities in crisis, such as J&K, are limited. Drèze (Citation2017) reported higher levels of food security in J&K than in other areas of the Indian subcontinent, a contradictory this outcome for a region in the grips of a conflict. Drèze attributed this outcome to local egalitarianism, mutual aid, and historic land reforms. Studies focused on J&K have also focused on the public distribution system (Dar, Citation2015), which imports food grains and therefore dampens local agricultural markets (Pelliciardi, Citation2013).

Scholars have critiqued the Indian government’s extractionist development policies for land (Peer Ghulam & Jingzhong, Citation2015), water, and energy in J&K, all of which affect food sovereignty. Development projects in J&K such as hydropower projects that export power have been reported to be a mechanism for coercion of the Kashmiri people (Bhan, Citation2014). Scholars have also written about how the Indian military occupation has adversely affected natural resources (Kanth & Ghosh, Citation2015). For example, Kanth and Ghosh (Citation2015) reported that “a military cantonment area occupies 1458 acres (including a civilian area of 313 acres) of predominantly hilly, forested lands in Srinagar city” (p. 3). Militarization of land combined with rapid urbanization, land use change (Badar et al., Citation2013), and climate change (Romshoo et al., Citation2020) suggests a bleak outlook for urban smallholder farming in J&K and, ultimately, food sovereignty.

In summary, existing literature has suggested that actions by nation-states, guided by neoliberal ambitions, undermine food sovereignty by dismantling food systems resources. The scholarship on local planning in this process remains sparse, especially for cities in crisis. We attempt to close this gap by unpacking the interplay between political misgovernance at higher levels of governance, local planning, and food sovereignty in Srinagar, J&K.

Research Design and Data Collection and Analysis

We centered the empirical analysis on the experiences of urban residents—smallholder urban farmers, to be precise—who experienced the downstream effects of planning and governance. We focused on growers because of their dual experience as eaters and growers. We purposefully focused on growers who grow indigenous haakh (hāk); in addition to being nutritious, haakh is grown mainly for consumption by Kashmiris and is therefore crucial to the exploration of Kashmiri food sovereignty.

Data Collection

We obtained qualitative data through open-ended interviews with growers. Researchers used snowball sampling. Initially, local partners identified growers, including by visiting major markets to ask vendors where they sourced their haakh. Researchers then visited and recruited growers who recommended additional growers. Farmers at 41 farms agreed to be interviewed. One could not finish the interview because of poor weather. Ultimately, we report here on interviews with farmers from 40 farms (). All respondents self-identified as farmers and ethnic Kashmiris.

Table 1 Respondent characteristics.

A semistructured questionnaire, previously piloted in other Global South cities (Raja et al., Citation2021), was modified for Srinagar. The questionnaire included closed-ended questions (e.g., demographics, farm and land area) and open-ended questions about growers’ daily living practices, including growing, harvesting, transporting, selling, and consuming haakh. We probed respondents about the links between daily living practices and land use change, climate change, conflict, and public policy. The study protocols were approved by the principal investigator’s institutional review board.

Interviews were conducted at farms with a representative of the farming family in their language (Kashmiri). Interviews were conducted between 2017 and 2020, with each interview lasting 45 min on average. A major political shift occurred in this period. In August 2019, the Government of India (GOI) unilaterally decided to abrogate J&K’s semi-autonomous status. As a result, we discuss growers’ concerns before and after the governance shift.

contains summary information about the sample.Footnote3 Some of the quantitative data in are missing because respondents did not always provide numeric information. Occasionally, they provided ranges (e.g., age), in which case we report an average.

Data Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded with respondents’ permission. Interviews were translated and transcribed by two researchers from Kashmiri into English and spot-checked for accuracy by two lead authors (all bilingual). The lead author read, coded, and extracted major themes inductively, and co-authors corroborated the themes. We interpreted the interviews against the landscape of planning documents, including Srinagar’s latest master plan, a sustainable development report, and relevant historical land policies. Analysis traced the pathways between governance, planning/development, and food sovereignty.

Conducting research in a crisis setting poses limitations. Trust among people is frayed, and fear of reprisal may dissuade people from being candid. Several respondents asked whether our team members represented the government. Upon learning that we were researchers, some urged us to draw attention to farmers’ plight. Knowing that researchers were Kashmiri likely facilitated trust. Only one respondent (out of 40) was initially reluctant to comment on government policy (but during the interview proceeded to detail policy impacts). When we asked for growers’ permission to audio record, one respondent noted, “You are entirely welcome to record. We [Kashmiris] are used to protesting for our freedom on the streets; talking about haakh is no big deal.” This willingness is noteworthy because there is a severe curb on freedom of expression in J&K (Drèze, Citation2017). On balance, we assessed the data to be an accurate, if muted, representation of farmers’ challenges. We experienced other challenges as well. Team members traveled during curfews, shutdowns, strikes, and protests to collect data at risk to themselves. Spread across cities, our team could not communicate due to extended telecommunication lockdowns.

Findings From a Case Study of Srinagar, a City in Protracted Crisis

Regional History

After the British East India Company sold J&K to their feudatory collaborators, the Dogras, in 1846, decades of unjust rule (Rai, Citation2019; Thorp, Citation1868) led to the brutal suppression of people’s rights (Bhan et al., Citation2018). With Britain’s retreat from the Indian subcontinent (Zamindar, Citation2013), the political fate of several princely states like J&K was undecided. Faced with an uprising for democracy, the ruler of J&K sought military aid from the newly formed GOI and, in exchange, signed the Instrument of Accession in 1947, which marked J&K’s provisional accession to India (Bhan et al., Citation2018; Snedden, Citation2015). As part of the agreement, and per United Nations (UN) resolutions 47, 48, and 91, the GOI promised Kashmiris a plebiscite to determine their political future, but this promise has remained unfulfilled (Bhan et al., Citation2018; Snedden, Citation2015).

Several provisions of the Indian constitution, such as Article 370, acknowledged J&K’s provisional access to India and its internationally recognized disputed status (e.g., India’s control in J&K was limited to defense, communication, and foreign affairs). Notably, Article 35A ensured that the J&K legislature alone could legislate with regard to land, employment, and settlement and define permanent residency. J&K’s unique political status in India allowed its semi-autonomous state legislature to enact various land protections.Footnote4 At a time when many nations (including India) were marching toward a Green Revolution (Holt Giménez & Shattuck, Citation2011), J&K’s Big Landed Estate Abolition Act (1950) set an upper limit of 22.5 acres on land ownership for equitable distribution (Jammu and Kashmir State Legislature, Citation1950). The J&K government acquired excess land and redistributed it to land tillers. Subsequently, the Agrarian Reform Act (1976) further shrank the ceiling on landholdings to 12.5 acres to prevent absentee land ownership and encourage working farmscapes. The J&K government enacted the J&K Utilization of Land Act (Citation1953) and the J&K Prohibition on Conversion of Land and Alienation of Orchards Act (Citation1975), which prohibited land use conversions, especially fruit orchards, without scrutiny. At the same time, nonresidents (anyone from India or elsewhere) were prohibited from purchasing/owning land in J&K (Constituent Assembly of India, Citation1949; Government of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, Citation1954).

Despite these protections, the GOI continually diminished J&K’s autonomy through a series of executive, legislative, and juridical changes (Duschinski & Bhan, Citation2022; Duschinski & Ghosh, Citation2017). Those at the helm of the J&K legislature operated as client regimes acting on India’s behalf rather than as representatives of Kashmiris’ political aspirations. Nepotism and rampant corruption within J&K fueled discontent. Following rigged elections in the mid-1980s, an armed insurgency by Kashmiris erupted against Indian control in the early 1990s, a period of intense turmoil. Indeed, the conflict in J&K ought to be understood not only as a result of the departure of a Western colonizing force (Great Britain) but as the continual aftermath of expansionist (spatial) and extractive (material) ambitions of a postcolonial India (Junaid, Citation2013; Osuri, Citation2017).

A final blow to J&K’s diminished autonomy came on August 5, 2019. The GOI unilaterally dissolved the J&K legislature and reorganized the erstwhile state’s boundaries into two union territories directly under the GOI’s control. Simultaneously, the GOI abrogated Kashmiri land and property laws, opening the region to non-Kashmiri speculators (Ministry of Law and Justice, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). In particular, the GOI amended the Jammu Kashmir Development Act of 1970 to remove protections for Kashmiri permanent residents of the erstwhile state to purchase and own land. Simultaneously, the definition of who constituted a permanent resident of Kashmir was expanded. These changes have already intensified land and resource dispossessions in J&K and fueled concerns over settler-colonial ambitions of India in the region.

A City Besieged by Protracted Crisis

Srinagar is nestled in a valley among mountain peaks. Compact neighborhoods are interlaced with rivers and canals connected to the picturesque Dal Lake. Winding lanes connect a vibrant mix of houses, greengrocers, and bakers. Newer neighborhoods sprawl away from the urban core. Kitchen gardens and urban farms, or vaaeri (wə̄r), are interspersed throughout the city. About 2% (15 km2) of the 766 km2 area of Srinagar district is for vegetable farming (Town Planning Organization Kashmir, Citation2019).

Markers of hypermilitarization punctuate the urban fabric. Security checkpoints and concertina wires on roads are ubiquitous. Indian armed forces occupy public spaces, including parks, community centers, and commercial and residential buildings (Kanth & Ghosh, Citation2015). The master plan indicated that more land is restricted for armed forces than is in use for public infrastructure.

Militarization affects the Kashmiri food system. The army occupies farmlands and orchards (Dar, Citation2015). Transportation of produce from source to market is interrupted during shutdowns. Foodservice workers’ commutes are hazardous (e.g., a baker traveling to her bakery was shot dead by Indian troops in 2020). Food demand and prices are volatile. During government-imposed curfews and protest strikes, markets and grocery stores remained shut, particularly during intense and extended unrest periods. Troops prohibited Kashmiri civilians during curfews from leaving their private spaces outside specified hours. Armed forces harassed, beat, or shot people who violated curfews. As a result, people’s ability to travel to markets to purchase food has been significantly interrupted (Hussain, Citation2019).

Malnutrition is significant in the district of Srinagar (which includes municipal limits and adjacent areas). Data suggest that 26.9% of children under the age of 5 have experienced stunted growth; 48.8% of women of reproductive age have anemia, and chronic disease is on the rise (George et al., Citation2017). Curiously, nutrition outcomes in Srinagar have been better than those reported for districts in India (compared with 599 districts of India, Srinagar ranked 63rd [George et al., Citation2017], a contradiction we address later).

A City Nourished by Haakh

In a militarized landscape, growers raise haakh, an indigenous, nutritious green from the Brassica oleracea species. A 45-year-old farmer noted, “Haakh Che Saen Pehchan” (“Haakh is our identity”), adding that he would continue to grow it as long as his body allowed him to labor on the farm. Multiple interviewees signaled haakh’s cultural importance by referencing the Kashmiri expression, “haakha-batte chu challan,” which loosely translates to “All is well because haakh (and rice) is available to me” (Interviews, June 1, 2017, and March 6, 2022). Another signaled its affordability, noting, “Haakh is for the rich and the poor” (Interview, March 3, 2020).

Farmers described haakh’s microspatial neighborhood terroir. Farmers identified haakh by the specific neighborhood where it is grown: Kawduor haakh in the Kawdoar neighborhood; Khanyaer haakh in Khanyar; and haenz haakh on floating gardens on the Dal Lake.Footnote5

Most farms operated on small lots, likely an outcome of the 1950s J&K land reforms. Land is held in private ownership (milkiet) or shared as commons (shamilat) or as state-held land (khalsa). Farmers reported owning an average of about 0.5 acre of private land, mostly inherited from their elders, and some reported using commons and state-held land for animal grazing. Farmers used traditional practices, though change was also evident. A significant majority saved, shared, and traded haakh seeds. Multiple farmers reported their mistrust of seeds available from the state-run agriculture department and commercial nurseries based on experiences of crop failures.

Growers reported a high frequency of haakh consumption in their households. On average, growers and their families ate haakh four times a week. Notably, none reported hunger within their families. Many also reported growing other vegetables (including cucumbers, eggplant, and peppers; a few reported growing rice and fruits and raising animals), which likely contributed to their dietary diversity. All 40 farmers hailed the nutritional value of haakh. About a dozen referenced its “medicinal” “and healing” properties and shared that local physicians “prescribe” haakh as both “prevention” and “treatment” for many ailments. One noted, “If we eat meat for three to four days, we must have haakh the following day.… Haakh is salubrious.” Signaling shifts globally, some farmers—more women than men—reported that the younger generations’ food preferences were shifting away from haakh to other foods.

In addition to eating it themselves, growers distributed haakh throughout the city. They sold to neighborhood stores (some owned small stores), mobile vendors, wholesale markets, or neighbors and passersby at their farms. The geographic spread of haakh plots throughout the city was especially crucial during curfews. One respondent, interviewed after 2019, noted,

[When] curfew was put in place, people came looking for me; I did not have to take the haakh to the market; everyone came here (to the farm).… There has been no shortage, neither has there been any competition. At least haakh is our own; we collect seeds and prepare seedlings at home. (Interview, March 3, 2020)

For the most part, farmers viewed their work as ordinary. One farmer hinted at the public benefit of farming: “May God forgive me for saying so…after God, the universe depends on farmers. Only when a farmer works hard…will they grow vegetables, rice, beans…only then can people eat.… [F]arming is essential” (Interview, March 6, 2020). Indeed, collectively, Srinagar’s haakh growers have been providing the “essential” service of growing and nourishing Srinagar for an average of 30 years (), including in the city’s most turbulent times.

Growers Faced Intersecting Burdens

Urban farmers voiced three intersecting challenges repeatedly: economic precarity, climate change, and conflict. Farming enabled farmers to barely subsist. Some reported having sold portions of land to meet unexpected or significant expenditures (including home repairs, weddings, health-related expenditures, or children’s education), and the remainder were readying themselves for the prospect of selling land. Most (24 of 40) reported that their families depended on other income sources (see ).

Farmers reported flooding, the early arrival of (new) pests, and heat-related losses of crops as threatening their livelihood. Multiple growers recalled the impacts of flooding events (e.g., in 2014) on their harvest.Footnote6 Farmers pointed to increased impervious surfaces through various land developments as partly the cause of flood events. Farmers also attributed flooding problems to the governments’ mismanagement of spillover canals and floodgates; scholars have reported military influence in flood management (Kanth & Ghosh, Citation2015).

Finally, growers reported kharaab halaat, or “bad circumstances,” a Kashmiri euphemism for political turmoil, as a challenge, especially during harvest season. Ideally, haakh is transported to wholesale or retail customers the day it is harvested. Some growers transport it to aggregation hubs (mandis) or neighborhood stores. Others sell to contractors and vendors who collect haakh at farms for transport and resell elsewhere in the city. Frequent general strikes, lockdowns, and harsh curfews hindered transportation. Farmers and aggregators repeatedly altered routes and travel times to circumvent these hindrances. Growers and aggregators were also unable to communicate during telecommunications lockdown, which hindered coordination of delivery/pickup. A significant majority of farmers reported having lost their harvest due to the turmoil. Farmers also mentioned price volatility, especially when produce from outside the city of Srinagar flooded local markets. One farmer reported selling haakh for as little as Rs. 2/kg ($0.067/kg) compared with its regular price of Rs. 50/kg ($0.67/kg).

Growers likened their work to “gambling,” signaling the uncertainty from extreme weather layered with the political conflict.

Planning Engagement in Food Systems: Interrupted, Coerced, Complicit, and Impotent

The pathway between local planning and food sovereignty in cities in crisis is complicated. At a minimum, formal long-term planning processes are interrupted as political and civil upheaval overtakes urban life. Long-term protection of food-related resources such as land and water takes backstage. A nuanced view suggests that local planning is coerced by higher levels of authority and is complicit in undermining food sovereignty through ongoing decisions. Unfettered military power in J&K, for example, allowed for occupation of agricultural lands in violation of local planning and zoning mandates. At the same time, local planning institutions are complicit in undermining food sovereignty and selective rule implementation on land development. Under the best of circumstances, planning is rendered ineffective, or impotent, as the magnitude of political misgovernance by higher levels of authorities dwarfs efforts by local planners to protect cities and their food systems.

INTERRUPTED

The city of Srinagar has experienced the preparation of three statutory master plans under the auspices of the erstwhile J&K StateFootnote7 since the 1960s: 1971 to 1991, 2000 to 2021, and 2021 to 2035. Formal planning was interrupted between 1991 and 2000 due to the increased intensity of the turmoil (an armed insurgency broke out in 1989). The current plan was adopted in 2019, when J&K’s semi-autonomous state was dissolved (Town Planning Organization Kashmir, Citation2019). The current master planning document painted a contradictory picture. The opening framework was visionary but was not upheld by the resulting land use mandates. With a projected 3 million residents in 2035, the plan’s opening called for the “preservation of ecological resources, protection of agriculturally productive areas and leveraging targeted productive urban lands” (Town Planning Organization Kashmir, Citation2019, p. 32). The plan invoked assets (e.g., the city’s heritage, natural resources, and local knowledge) and recognized many, if not all, challenges (e.g., rapid urbanization and extreme weather events). The plan explicitly advocated protecting the local agriculture industry and promoting food security (though not food sovereignty). In other ways, the plan fell short. The plan claimed extensive public participation with no explicit mention of engaging with urban farmers. Indeed, all of our respondents noted their limited engagement with government entities. The plan’s strategies for the food system were counterproductive for haakh growers’ food security. The plan called for more industrialized forms of (commercial) agriculture with no protection for indigenous practices, potentially placing smallholders at risk (Shrestha, Citation2008). Notably, the proposed land use resulting from the master plan contradicted the opening policy framework. The internal contradiction may have resulted from the change in planning department leadership during the plan-making process; such interrupted leadership is a commonplace characteristic of planning in crisis cities.

COERCED

Military power coerces planning decisions and institutions to undermine food sovereignty. The current plan noted, “The indiscriminate dispersal of defense establishments in every nook and corner of the city including the civilian areas is construed as a major impediment in city development” (Town Planning Organization Kashmir, Citation2019, p. 69). Yet, the military continued to occupy farmlands (and other spaces) due to unbounded powers conferred by the GOI. As noted earlier, Kanth and Ghosh (Citation2015) reported that the armed forces influenced the work of local authorities (and that dissent was dangerous), leading to the coercion of planning actors and institutions.

Conditions after 2019 worsened. Haakh farmers interviewed after 2019 shared nuanced reactions about the future. Some were defiant (toward speculators), though most were anxious or resigned to their fate. One noted that they would not part with their privately owned land “as long as they were alive” (Interview, March 6, 2020). But they also recognized the dangers. One farmer estimated that about 5% to 30% of the farmland in their area was khalsa land. He added that “farmers fear that the government might snatch that [khalsa land] back” (Interview, March 6, 2020). With the repeal of J&K laws, there is no protector for lands in commons (shamilat) or those held by the state (khalsa), both of which are essential for agriculture. The farmer described the 2019 shifts as “zulm,” or cruel and unjust punishment (interview).

COMPLICIT

Local planning institutions are complicit in undermining food sovereignty. The current plan acknowledged that in its 45 years of statutory history, planning in J&K has missed its mark through “administrative inertia and lack of a strong political will” (Town Planning Organization Kashmir, Citation2019, p. 9). The plan noted, “Building permission process is so protracted…[that it becomes]…an alibi for violations (Town Planning Organization Kashmir, Citation2019, p. 68). As mentioned earlier, selective enforcement of zoning and land development rules against smallholder farmers who had limited reach within local bureaucracies diminished their ability to grow haakh. A farmer who wished to quit farming could not do so because they could not sell their land, which was classified as protected. This selective classification and enforcement of these so-called protected farmlands deprived farmers of their land while granting the military and speculators de facto access to these same lands.

IMPOTENT

The current master plan was adopted in February 2019, just months before the GOI unilaterally decommissioned J&K into a Union Territory of India in August 2019. The passage of the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Order in October Citation2020 (the Act was established in 2019) dissolved or amended laws of the erstwhile state of J&K, including its progressive land reforms (Ministry of Home Affairs [Department of Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh Affairs], Citation2020). Pre-2019 prohibitions on transfer of nonmovable property to nonpermanent residents of J&K were omitted through amendments. In addition, the J&K Development Act was modified: Kashmiris were no longer the only people who could own, inherit/transfer, or acquire land, setting the stage for settler-colonialism. Moreover, the Indian military could now declare any land—including farmland—in Kashmir a strategic area, wresting control of land away from locals.

While working his lands, a farmer dismally observed that there was no guarantee that “this land” would be available for farming in urban areas such as Srinagar a few years into the future. The farmer noted that the constitutional changes of 2019 made the agricultural land even more vulnerable to nonagricultural land use. If farmers were “offered land prices way beyond their land’s (agricultural) value, how can they resist?” the farmer asked (Interview, March 10, 2020). Moreover, he argued that the decision by one or two farmers to sell a chunk of farmland would have a ripple effect on the city’s food infrastructure.

The GOI’s newly appointed government of the Union Territory of J&K invoked the rhetoric of development to broker real estate deals with non-Kashmiris. For example, the governor of the new Union Territory of J&K convened a “Real Estate Development Summit 2021” and signed deals worth Rs. 18,300 crores ($10 million) for real estate development (Masood, Citation2021). Sixty proposed projects included residential (39), commercial (8), hospitality (4), infrastructure (4), finance (2), and film and entertainment (3) sector projects. Mirroring extractive development fantasies (or nightmares) in other Global South cities (Watson, Citation2014), in Srinagar, a Dubai-based investor is proposing a 500,000-ft2 mall, touted as the first foreign investment of its kind (Press Trust of India, Citation2022). Such neoliberal projects will disrupt land markets, further erode J&K’s egalitarian land distribution, and, ultimately, dispossess haakh farmers. In all likelihood, the current plan will serve as a roadmap for speculators to wrest lands away from Kashmiri growers. The powerful political shifts of 2019 have rendered planning impotent.

In summary, in conflict regions such as the J&K, food sovereignty is undermined by interruptions to and coercion of planning by armed forces and complicity and impotence of planning amid misgovernance and larger political upheavals. In a brazen contradiction, a 2020 development report by the newly formed Union Territory called for zero hunger as part of UN Sustainable Development Goals (Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir, Citation2020). Notably, the development report did not call for farmland protection for Kashmiris. While contemporaneously dismantling the Kashmiri food system through the dissolution of land laws, this contradictory policy position sets the stage for Kashmir’s food dependence.

Discussion

Haakh is the quintessential good food: affordable, healthful, and culturally celebrated. Kashmiri farmers’ restorative practices coupled with historic land reforms likely explain food security today. With diminishing Kashmiri autonomy, farmers adapted and resisted through their daily lived practices by growing, selling, preparing, eating, and sharing haakh, echoing practices by communities elsewhere (Mazhar et al., Citation2007; Morrison, Citation2011). Stoic as they are, urban farmers bear the burden of failed governance and planning. A significant majority noted that all levels of government have had a long history of apathy toward growers. For example, farmers who lost their crops to the 2014 floods reported receiving little to no recovery support from the government. Farmers with lands in low-lying areas reported that local government officials regulated floodgates in ways that flood farms. Some noted that the government enforced development regulations selectively (the master plan concurred that there were violations), making local planning practices complicit in undermining food sovereignty. As scholars have noted, the state places itself outside the laws to exceptionalize particular activities (Boamah & Amoako, Citation2020). In effect, like other parts of the Global South, the state exercises an approach of convenient absence (i.e., no flood risk management) to leverage this problem later to enforce a brutal presence (i.e., unfair land use implementation; Amoako, Citation2016). Contemporary discourse on planning for food systems—which still calls for local planners’ greater engagement in food systems (Cabannes & Marocchino, Citation2018)—needs to shift dramatically to critically address the more pernicious role of planning in undermining food systems in conflict cities.

Following governance shifts in 2019, unfettered capital buttressed by the military has accelerated extractive development projects in Kashmir. Scholars have argued that “infrastructures of occupation” dispossess people by undermining their access to farmland, highland pastures, glaciers, and forests (Bhan, Citation2020, p. 73). Military urbanism and extreme gentrification dispossess people of the means to produce their food (Desmarais et al., Citation2015). Echoing similar discourse on settler colonialism and indigenous food sovereignty (Kepkiewicz & Dale, Citation2019), Srinagar has increasingly manifested as a site of embodied state-sanctioned violence by the settler-colonial GOI, with significant impacts on urban haakh farmers and the urban foodscapes.

Though the link between food sovereignty and neoliberalism has been well considered in the literature (Holt Giménez & Shattuck, Citation2011), we offer a situated understanding of this link. In particular, we reveal planning as a deeply embedded neoliberal place-making effort leveraged to reproduce state-sanctioned erasure and dispossession of indigenous food voices and practices. This revelation has been increasingly clarified and reinforced within state-sanctioned conflict regions, where the assumed neutral and technicist position of planning is subsumed within the war machine of a settler-colonial state. In violence and conflict we see clearly the deeply problematic, co-opted, and complicit role of planning within the broader discourse on neoliberalism and food sovereignty.

Elsewhere we have written that people must drive and design food policy (Raja et al., Citation2018, 2020). This principle holds true to a certain degree in cities in protracted crises. Haakh farms are a community development infrastructure for a city in crisis. Networks of haakh growers are the de facto food system planners of Srinagar. People-led community development and community infrastructures offer protection against food insecurity for sure. But their ability to ensure food sovereignty without broader governance and policy shifts is limited. Regrettably, the space—political and literal—for Kashmiris to imagine and control their food system is disappearing. Public dissent against government policies in J&K comes with severe penalties enabled by increasingly draconian “security” laws by India (e.g., the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act; Press Trust of India, Citation2021). Silencing dissenting voices makes public engagement in food systems planning, community development, or any public decision making impossible or farcical.

Takeaways

Intersecting burdens from undemocratic governance and militarism (from India), weak planning (J&K and Srinagar), and climate change (global to local) are implicated in haakh growers’ dismal present and bleak future. Interruptions in local planning, coercion by the military of local plans, complicity of local bureaucracy in selective rule enforcement, and local planning impotence in the face of fantastical neoliberal development projects (Watson, Citation2014) undermine food sovereignty. Romanticizing urban farmers’ resilience misdirects attention away from the structural origins of their burdens. Ambiguous interpretation and enforcement of land rules, development schemes that convert agricultural land to nonagricultural purposes, and militarized urbanism threaten urban growers in cities in protracted crisis. In such contexts of protracted crisis, planning risks conflating public with state (Purcell, Citation2016).

Srinagar’s experience offers several takeaways for planning (). First, cities in protracted crises are a stark reminder that urban planning (at the local level) is anything but technical (Bollens, Citation2012, Citation2020). Therefore, planning curricula have to prepare students (future planners) for the politics of planning. When decoupled from political processes at multiple scales of governance, routine planning exercises risk being complicit, co-opted, or coerced to make way for speculator-settlers. Under the ambit of a failed state, formal (local) planning dispossesses people with differential access to power. In such conditions, planners must understand how to occupy and navigate liminal spaces between the public and the state. Yet planning education—especially models exported from the Global North—reinforces apolitical planning. Our insight about reform of planning education is hardly new but regrettably bears repeating in the context of cities experiencing protracted crises.

Table 2 Possibilities for planning in conflict cities.

As we noted earlier, planning literature has been limited in its understanding of the role of planning on urban food systems in cities in crises. Future research is needed to better understand how communities’ food systems can better serve cities in crisis (research on building food sovereignty is distinct from the abundant literature on external food aid during disasters and crises).

Planning must reimagine how to build safe and healthy foodscapes in cities in crisis beyond the context of national security and neoliberal imperatives. Planners have to align their work (including planning) with aspirations of smallholder growers and with calls for food sovereignty. To the best of their ability, local planners in cities such as Srinagar have to privilege and protect urban smallholder growers’ control of their food system, including growers’ control over land and water. Such protections are crucial for both food security and food sovereignty of cities in crisis.

Finally, the monitoring, recording, and suspension of contested, illegal, or undemocratic land conversions, land grabs, or land transfers (without full consent of indigenous and local peoples) ought to be a local and international policy priority. In particular, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Secretary General can call for restricting land grabs and land transfers in cities experiencing protracted crises across the globe. Failure to act is, in fact, a de facto plan for future food insecurity in cities experiencing protracted crises. Urban farmers are growing their freedom, but planning and development, enacted by a settler-colonial state, will make them unfree. Prospects for food sovereignty in Srinagar are dismal. The time to interject in cities experiencing protracted crises around the globe is now.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this article to the haakh growers who nourish the city of Srinagar and Pandit Rughonath Vaishnavi, who advocated for equitable land policies on behalf of Kashmiris. We are grateful to the Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab team for their extensive support of this project. Thank you to doctoral students and faculty colleagues at the University at Kashmir for their support and to the editor and anonymous reviewers for insightful comments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samina Raja

SAMINA RAJA ([email protected]) is a professor at the University of Buffalo.

Athar Parvaiz

ATHAR PARVAIZ ([email protected]) is an independent researcher in Jammu and Kashmir.

Lanika Sanders

LANIKA SANDERS ([email protected]) is a research affiliate at the University of Buffalo.

Alexandra Judelsohn

ALEXANDRA JUDELSOHN ([email protected]) is a doctoral student at the University of Michigan.

Shireen Guru

SHIREEN GURU ([email protected]) is a research affiliate at the University of Buffalo.

Mona Bhan

MONA BHAN ([email protected]) is an associate professor at Syracuse University.

Goldie Osuri

GOLDIE OSURI ([email protected]) is a professor at the University of Warwick.

Mehroosh Tak

MEHROOSH TAK ([email protected]) is an assistant professor at The Royal Veterinary College, University of London.

Yeeli Mui

YEELI MUI ([email protected]) is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University.

Emmanuel Frimpong Boamah

EMMANUEL FRIMPONG BOAMAH ([email protected]) is an associate professor at the University of Buffalo.

Notes

1 History has forced varied jurisdictional titles on the Jammu and Kashmir region, including principality, state, and now union territory. Its borders, too, are contested. The varied jurisdictional and governance arrangements are vital to the story we tell, and therefore, for clarity, we call it a region of the Himalayan belt.

2 We use the phrase protracted crisis to draw attention to the duration of the political conflict, the power asymmetry between state and civilian actors, the weakened institutions, and adverse health outcomes in the study setting.

3 Spouses of 27 respondents joined the conversation (we report the presence of both women and men on urban farms because patriarchal norms in research and policy diminish female farmers).

4 A group of Kashmiris committed to the politics of equity proposed the Naya Kashmir (New Kashmir) policy manifesto in 1944 that was progressive for its time: it called for redistribution of land to tillers, time for rest for workers, and universal healthcare (Kaul, in press). Early land reforms in J&K drew on these ideas.

5 Floating gardens are flotillas of congealed weeds and other organic materials that serve as (a temporary) growing medium for vegetables on Dal Lake.

6 The 2014 floods inundated 42.5 km2 and affected 2.2 million people (Ahmad, Pandey, & Kumar, Citation2020).

7 Beginning in 1947, J&K state legislature provided the enabling authority for district- (and city-) level town planning. Policy mandates were established at higher levels of government, and local authorities prepared plans to execute them.

REFERENCES

- Ahmad, T., Pandey, A. C., & Kumar, A. (2020). Impact of 2014 Kashmir flood on land use/land cover transformation in Dal lake and its surroundings, Kashmir valley. SN Applied Sciences, 2(4), 681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2434-8

- Amoako, C. (2016). Brutal presence or convenient absence: The role of the state in the politics of flooding in informal Accra, Ghana. Geoforum, 77, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.10.003

- Anguelovski, I. (2015). Healthy food stores, greenlining and food gentrification: Contesting new forms of privilege, displacement and locally unwanted land uses in racially mixed neighborhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1209–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12299

- Badar, B., Romshoo, S. A., & Khan, M. A. (2013). Integrating biophysical and socioeconomic information for prioritizing watersheds in a Kashmir Himalayan lake: A remote sensing and GIS approach. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 185(8), 6419–6445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-012-3035-9

- Battersby, J. (2017). Food system transformation in the absence of food system planning: The case of supermarket and shopping mall retail expansion in Cape Town, South Africa. Built Environment, 43(3), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.43.3.417

- Bhan, M. (2014). Morality and martyrdom: Dams, “dharma,” and the cultural politics of work in Indian-occupied Kashmir. Biography, 37(1), 191–224. https://doi.org/10.1353/bio.2014.0012

- Bhan, M. (2020). Infrastructures of occupation: Mobility, immobility, and the politics of integration in Kashmir. In S. Bose & A. Jalal (Eds.), Kashmir and the future of South Asia (pp. 71–90). Routledge.

- Bhan, M., Duchinski, H., & Zia, A. (2018). “Rebels of the streets”: Violence, protest, and freedom in Kashmir. In H. Duschinski, M. Bhan, A. Zia, & C. Mahmood (Eds.), Resisting occupation in Kashmir (pp. 1–41). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Boamah, E. F., & Amoako, C. (2020). Planning by (mis)rule of laws: The idiom and dilemma of planning within Ghana’s dual legal land systems. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419855400

- Bollens, S. A. (2012). City and soul in divided societies. Routledge.

- Bollens, S. A. (2020). National policy agendas encounter the city: Complexities of political-spatial implementation. Urban Affairs Review, 56(5), 1357–1387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087418811676

- Borras, S. M., Hall, R., Scoones, I., White, B., & Wolford, W. (2011). Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: An editorial introduction. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.559005

- Cabannes, Y., & Marocchino, C. (Eds.). (2018). Integrating food into urban planning. University College London Press.

- Constituent Assembly of India. (1949). Constitution of India. https://www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/coi_part_full.pdf

- Coté, C. (2016). “Indigenizing” food sovereignty: Revitalizing indigenous food practices and ecological knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanities, 5(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030057

- Daigle, M. (2019). Tracing the terrain of indigenous food sovereignties. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(2), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1324423

- Dar, T. (2015). Food security in Kashmir: Food production and the universal public distribution system. Social Change, 45(3), 400–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049085715589461

- Desmarais, A. A., Qualman, D., Magnan, A., & Wiebe, N. (2015). Land grabbing and land concentration: Mapping changing patterns of farmland ownership in three rural municipalities in Saskatchewan, Canada. Canadian Food Studies / La Revue Canadienne Des Études Sur L’alimentation, 2(1), 16–47. https://doi.org/10.15353/cfs-rcea.v2i1.52

- DiPrete Brown, L., Atapattu, S., Stull, V. J., Calderón, C. I., Huambachano, M., Houénou, M. J. P., Snider, A., & Monzón, A. (2020). From a three-legged stool to a three-dimensional world: Integrating rights, gender and indigenous knowledge into sustainability practice and law. Sustainability, 12(22), 9521. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229521

- Drèze, J. (2017). Sense and solidarity: Jholawala economics for everyone. Oxford University Press.

- Duschinski, H., & Bhan, M. (2022). Third world imperialism and Kashmir’s sovereignty trap. In M. Bhan, H. Duschinski, & D. Misri (Eds.), The handbook of critical Kashmir studies (pp. 323–340). Routledge.

- Duschinski, H., & Ghosh, S. N. (2017). Constituting the occupation: Preventive detention and permanent emergency in Kashmir. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 49(3), 314–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2017.1347850

- Food Security Information Network and Global Network Against Food Crises. (2021). Global report on food crises 2021. http://https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/GRFC2021.pdf

- Frimpong Boamah, E., Sumberg, J., & Raja, S. (2020). Farming within a dual legal land system: An argument for emancipatory food systems planning in Accra, Ghana. Land Use Policy, 92, 104391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104391

- George, N. R., Vaid, A., Nguyen, P. H., Avula, R., & Menon, P. (2017). Jammu and Kashmir district nutrition profile: Srinagar. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll2/id/132182

- Government of India. (2011). Census of India. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner; Ministry of Home Affairs. https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-common/censusdata2011.html

- Government of the State of Jammu and Kashmir. (1954). Constitution (application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order. http://jklaw.nic.in/constitution_jk.pdf

- Grey, S., & Patel, R. (2015). Food sovereignty as decolonization: Some contributions from indigenous movements to food system and development politics. Agriculture and Human Values, 32(3), 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9548-9

- Holt Giménez, E., & Shattuck, A. (2011). Food crises, food regimes and food movements: Rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(1), 109–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.538578

- Horst, M. (2017). Food justice and municipal government in the USA. Planning Theory & Practice, 18(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2016.1270351

- Hussain, A. (2019, August 9). Pre-dawn food run then rush home: Kashmir under curfew. Associated Press News. https://apnews.com/article/ap-top-news-religion-kashmir-india-international-news-98112a6077444fb3a0bec8f0c43cf687

- Jammu and Kashmir Agrarian Reforms Act. XVII of 1976 C.F.R. (1976).

- Jammu and Kashmir Prohibition on Conversion of Land and Alienation of Orchards Act. (1975).

- Jammu and Kashmir State Legislature (1950). Big landed estates abolition act. https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_states/jammu-and-kashmir/1950/1950J&K17.pdf

- Jammu and Kashmir Utilization of Land Act. (1953). https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_states/jammu-and-kashmir/1953/1953J&K9.pdf

- Junaid, M. (2013). Death and life under occupation: Space, violence, and memory in Kashmir. In V. Kamala (Ed.), Everyday occupations: Experiencing militarism in South Asia and the Middle East (pp. 158–190). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Kanth, M. F., & Ghosh, S. N. (2015). Landscapes of an occupation. Himal Southasian.

- Kepkiewicz, L., & Dale, B. (2019). Keeping “our” land: Property, agriculture and tensions between indigenous and settler visions of food sovereignty in Canada. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(5), 983–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1439929

- MacNeill, T. (2020). Indigenous food sovereignty in a captured state: The Garifuna in Honduras. Third World Quarterly, 41(9), 1537–1555. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1768840

- Manson, J. (2015). Relational nations: Trading and sharing ethos for indigenous food sovereignty on Vancouver Island. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/24/items/1.0223167

- Masood, B. (2021, December 28). Day after realty summit, Kashmir parties slam attempt to “change” demography. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/kashmir-realty-summit-7695174/

- Mazhar, F., Majahāra, P., Foundation, A., Buckles, D., Centre, I. D. R., & Satheesh, P. V. (2007). Food sovereignty and uncultivated biodiversity in South Asia: Essays on the poverty of food policy and the wealth of the social landscape. Academic Foundation.

- Ministry of Home Affairs (Department of Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh Affairs). (2020). Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir reorganisation (adaptation of central laws) third order.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. (2019a). Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act. http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/210407.pdf

- Ministry of Law and Justice. (2019b). Presidential Order C.O. 273. http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/210243.pdf

- Morrison, D. (2011). Indigenous food sovereignty: A model for social learning. In H. Wittman, A. A. Desmarais, & N. Wiebe (Eds.), Food sovereignty in Canada: Creating just and sustainable food systems (pp. 97–113). Fernwood Publishing.

- Mui, Y., Khojasteh, M., Judelsohn, A., Sirwatka, A., Kelly, S., Gooch, P., & Raja, S. (2021). Planning for regional food equity. Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(3), 354–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1845781

- Nyéléni Village. (2007, February 27). Declaration of Nyéléni. Sélingué, Mali. https://nyeleni.org/IMG/pdf/DeclNyeleni-en.pdf

- Oliveira, G. d L. T., McKay, B. M., & Liu, J. (2021). Beyond land grabs: New insights on land struggles and global agrarian change. Globalizations, 18(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1843842

- Osuri, G. (2017). Imperialism, colonialism and sovereignty in the (post)colony: India and Kashmir. Third World Quarterly, 38(11), 2428–2443. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1354695

- Patel, R. (2009). Food sovereignty. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(3), 663–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150903143079

- Peer Ghulam, N., & Jingzhong, Y. E. (2015). Of militarisation, counter-insurgency and land grabs in Kashmir. Economic and Political Weekly, 50(46/47), 58–64. https://www.epw.in/journal/2015/46-47/special-articles/militarisation-counter-insurgency-and-land-grabs-kashmir.html

- Pelliciardi, V. (2013). From self-sufficiency to dependence on imported food-grain in Leh District (Ladakh, Indian Trans-Himalaya). European Journal of Sustainable Development, 2(3), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2013.v2n3p109

- Pothukuchi, K. (2015). Five decades of community food planning in Detroit: City and grassroots, growth and equity. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(4), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15586630

- Pothukuchi, K. (2018). Vacant land disposition for agriculture in Cleveland, Ohio: Is community development a mixed blessing? Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(5), 657–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1403855

- Pothukuchi, K., & Kaufman, J. L. (2000). The food system. Journal of the American Planning Association, 66(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360008976093

- Press Trust of India. (2021, June 15). Man jailed for “No expectations from outsiders” remark. Kashmir Observer. https://kashmirobserver.net/2021/06/15/political-activist-arrested-for-making-comments-that-upset-dc-ganderbal/

- Press Trust of India. (2022, January 4). Dubai’s Emaar group to develop 500,000 sq ft shopping mall in Srinagar. Business Standard. https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/dubai-s-emaar-group-to-develop-500-000-sq-ft-shopping-mall-in-srinagar-122010300886_1.html

- Purcell, M. (2016). For democracy: Planning and publics without the state. Planning Theory, 15(4), 386–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095215620827

- Rai, M. (2019). Hindu rulers, Muslim subjects: Islam, rights, and the history of Kashmir (Ebook ed.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 2004)

- Raja, S., Picard, D., Baek, S., & Delgado, C. (2014). Rustbelt radicalism: A decade of food systems planning practice in Buffalo, New York (USA). Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 4(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2014.044.015

- Raja, S., Sweeney, E., Mui, Y., & Frimpong Boamah, E. (Eds.). (2021). Local government planning for community food systems: Opportunity, innovation and equity in low- and middle-income countries. United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization.

- Raja, S., & Whittaker, J. (2018). Community food infrastructure: A vital consideration for planning healthy communities. In T. Beatley, C. Jones, & R. Rainey (Eds.), Healthy environments, healing spaces: Current practice and future directions in health and design (pp. 207–230). University of Virginia Press.

- Raja, S., Whittaker, J., Hall, E., Hodgson, K., & Leccese, J. (2018). Growing food connections through planning: Lessons from the United States. In Y. Cabannes & C. Marocchino (Eds.), Integrating food into urban planning (pp. 134–153). University College London Press. https://www.uclpress.co.uk/products/111613

- Romshoo, S. A., Bashir, J., & Rashid, I. (2020). Twenty-first century-end climate scenario of Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya, India, using ensemble climate models. Climatic Change, 162(3), 1473–1491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02787-2

- Sharma, P., & Daugbjerg, C. (2020). The troubled path to food sovereignty in Nepal: Ambiguities in agricultural policy reform. Agriculture and Human Values, 37(2), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09988-1

- Shrestha, N. R. (2008). “Misery is my company now”: Nepal’s peasantry in the face of failed development. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 35(3), 452–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150802340438

- Snedden, C. (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Hurst.

- Thorp, R. (1868). Cashmere misgovernment. Wyman Brothers.

- Town Planning Organization Kashmir. (2019). Planning for sustainable growth and change: Master plan 2035 Srinagar metropolitan region. Town Planning Organization Kashmir.

- Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. (2020). Sustainable development goals (SDG): Progress report 2020. Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir.

- Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation. (2020). (Adaptation of Central Laws) Third Order, 2020, 11012/21/2020 C.F.R.

- Vía La Campesina. (2003). Food sovereignty. https://viacampesina.org/en/food-sovereignty/

- Watson, V. (2014). African urban fantasies: Dreams or nightmares? Environment and Urbanization, 26(1), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813513705

- Zamindar, V. (2013). India–Pakistan partition 1947 and forced migration. In I. Ness & P. Bellwood (Eds.), The encyclopedia of global human migration (pp. 1736–1739). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444351071.wbeghm285