Abstract

Urban planning for health equity should be guided by an intersectional approach. Intersectionality is an essential framework for understanding the multiple overlapping factors, such as social and economic inequalities, that produce health disparities. We offer four strategies that planning researchers and practitioners can use to develop and integrate an intersectional approach into planning for health equity: challenging implicit and explicit assumptions, building cross-sectoral coalitions united by a shared vision for social and environmental justice, applying transdisciplinary and co-designing approaches throughout the planning process, and using existing tools to evaluate the impact of programs and policies on advancing health equity.

An individual’s physical and social environments are integral determinants of health. Harmful exposures in one’s living and working conditions can create vulnerabilities that accumulate throughout the lifetime and across generations (Braveman, Citation2014). However, current planning efforts to improve public health mainly consider how social and environmental factors directly affect the health of populations as opposed to evaluating how these decisions alleviate or exacerbate existing inequalities within populations. This impairs our understanding of how planning produces health inequities and how planners can build health equity.

Health equity is “the assurance of the condition of optimal health for all people” and requires “(1) valuing all individuals and populations equally—that is, there are no invisible, undervalued, or disposable people; (2) recognizing and rectifying historical injustices; and (3) providing resources according to need” (National Academies of Sciences et al., 2019). Accordingly, it is imperative that planners seeking to improve health focus their efforts on addressing and eliminating disparities in outcomes, not just improving overall outcomes. Health disparities are “health differences that adversely affect defined disadvantaged populations based on one or more health outcomes” (Duran & Pérez-Stable, Citation2019, p. S10).

Structural racism is a major driver of health inequities. Throughout America’s history, racism has created and sustained discriminatory laws and policies that have been upheld by the judicial system and enforced by social and financial institutions (Williams & Collins, Citation2001). This amounts to a system that systematically perpetuates social, environmental, economic, and health inequities between different social groups by exploitation and subjugation through institutions, processes, and embedded systems (Bailey et al., Citation2017; Goetz et al., Citation2020; Williams, Citation2020). These relationships of exploitation are based in systems of White supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy. The intertwined and interlocking characteristics of these systems of domination make it difficult to separate race, gender, social class, sexuality, and ability because they are experienced simultaneously (Bonilla-Silva, Citation1997; Goetz et al., Citation2020; Harris, Citation1993; Pulido, Citation2017; The Combahee River Collective, Citation1977). Therefore, we encourage planners to use the intersectionality framework as a tool to understand how structural racism is an obstacle to health, and how a person or group’s position along social hierarchies, including but not limited to race, gender, and/or ability, shapes their opportunities to live a healthy life.

In the next section, we introduce intersectionality in more detail, discuss its utility for understanding where health inequities come from and how they persist, and consider its relevance for planning for health equity. Then we offer four strategies that planning researchers and/or practitioners can use to integrate intersectionality into efforts to understand and address urban health inequities.

Intersectionality: A Key Tool for Understanding Health Inequities and How They Persist

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that illustrates how intersecting social identities at the individual level reflect structural patterns of privilege and oppression along different axes, such as race, gender, social class, sexuality, and ability (Bowleg, Citation2012). Building on Black feminist scholarship (Davis, Citation1981; Lorde, Citation1984; The Combahee River Collective, Citation1977), Crenshaw (Citation1989, Citation1991) coined the term intersectionality to describe how systems and discourses marginalize the perspectives and lived experiences of Black women in ways that intersect and compound disadvantage. These systems of power (e.g., White supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy) are intertwined and interlocking, producing what Collins (Citation2000) called the matrix of domination, a concept that describes how domination and subjugation are encapsulated within intersecting oppressions across diverse context-specific realities. Explicitly acknowledging how structures of advantage and disadvantage create compounding burdens for individuals with multiple and intersecting marginalized identities (e.g., Black women with disabilities) is necessary for understanding and alleviating corresponding social and economic inequalities and corresponding health inequities (Bowleg, Citation2012; Crenshaw, Citation1989, Citation1991).

In planning history, there were periods of de jure (i.e., government sanctioned) and de facto (i.e., actions by private and public entities not sanctioned by law) segregation that led to racial zoning, racially restrictive covenants and deeds, redlining, blockbusting, racial steering, urban renewal, and the intentional siting of interstate and highway systems and public housing in Black neighborhoods to create racial boundaries (Harris, Citation1993; Rothstein, Citation2017). As a result, the social and economic inequalities produced along the axes of race, gender, motherhood, and social class have taken the form of relegating women of color, specifically Black women, to inner-city neighborhoods with poor access to social and municipal services and limited prospects for jobs in the labor market. Further, their children have been enrolled in poorly funded and racially segregated public schools (Collins, Citation2000). If any of their children have qualified for special education due to a disability, their school likely has not had the capacity to provide the necessary social and educational services. These students have also been more likely to experience repeated disciplinary action and increased exposure to the juvenile justice and criminal justice system (National Council on Disability, Citation2015). According to the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (Citation2014), 27% of Black boys and 19% of Black girls with disabilities received at least one out-of-school suspension in 2011–2012. Although the perpetuation of systemic inequality is fundamental to the functioning of the U.S. economy, intersectionality illuminates how different people experience and embody different inequalities.

An intersectional lens illuminates the differences and commonalities in the values and struggles of different social groups. Contrary to criticisms of intersectionality as being divisive, employing an intersectional framework has the potential to create solidarity and cohesion (Roberts & Jesudason, Citation2013). As Roberts and Jesudason (Citation2013) noted, engaging with people with different identities by exploring and establishing commonalities is “one of intersectionality’s most important methodologies” (p. 316) because it underscores the dynamics and the interactions that produce social and health inequities (Crenshaw, Citation1989). Intersectionality applies to everyone. Every individual lives within structures of multiple intersecting forms of privilege and oppression (e.g., race, gender, social class, sexuality, and ability) that either directly or indirectly affect their daily lives (Roberts & Jesudason, Citation2013).

However, commonality does not translate to sameness in histories and lived experiences. Intersecting, socially hierarchical systems affect individuals and groups of people differently (e.g., Black women vs. White women) due to their specific context and social position within society. Applying an intersectional framework to urban planning practice equips planners with a critical analytic tool to understand the underlying dynamics of social and economic inequalities that undergird health inequities, as well as generating solutions that effectively ameliorate these inequities and more equitably distribute power and resources in society and across space.

Intersectionality is not new to planning. The framework has been discussed in various domains including climate adaptation (Osborne, Citation2015), feminist and queer planning (Frisch, Citation2015; Rodó-de-Zárate, Citation2014), and access to amenities like parks (Powers et al., Citation2020). Intersectionality also aligns with planning theories such as advocacy and communicative planning (Davidoff, Citation1965; Innes & Booher, Citation2010), as well as approaches to addressing social and health inequities in cities such as antiracist planning (Thomas, Citation1997; Williams, Citation2020), antisubordination planning (Steil, Citation2022), reparative planning (Williams, Citation2020), and the “relational, health equity-oriented approach to planning” (Corburn et al., Citation2015, p. 267). An intersectional approach allows planners to examine the ways urban planning practice and policies have failed to respond to the diversity of cities within planning codes, legislation, processes, and urban design practices, which reflect the dominant values and assumptions of White men (Collins, Citation2000; Fincher & Jacobs, Citation1998; Sandercock, Citation1998, Citation2000; Williams, Citation2020).

Planners may follow the lead of public health scholars and practitioners who have demonstrated how useful an intersectional lens can be for understanding and addressing complex social and economic crises like the COVID-19 pandemic because it affords both a more precise understanding of health inequalities and insight on more effective strategies to address these inequities (Bowleg, Citation2021; Kapilashrami & Hankivsky, Citation2018; Poteat, Citation2021). These scholars have highlighted the utility of the framework for developing an integrated understanding of both micro-level (i.e., individual) experience and macro-level (i.e., structural and institutional) systems of oppression. They have identified strategies for overcoming key methodological challenges that planners may also face, like distinguishing between social positions and social processes (Bauer, Citation2014; Bowleg, Citation2012; Lapalme et al., Citation2020). At the same time, they have cautioned against narrowing the concept as it moves into the mainstream, insisting on the importance of centering power inequalities, not just intertwined identities, in efforts to build an intersectional public health praxis (Aguayo-Romero, Citation2021; Bowleg, Citation2021).

Strategies for Applying Intersectionality to Achieve Health Equity

Achieving health equity is an ongoing process that will require institutional adaptability and shifts in planning practice, including “continued institutional attention, public engagement, and accountability” (Corburn et al., Citation2015, p. 278). We present four strategies that, when integrated, would enable planners to successfully adopt an intersectional approach to planning for health equity.

Strategy 1: Challenge Implicit and Explicit Assumptions With Respect to Social Identity Categories and Social Problems as Well as Place Them Within the Context of Power Structures

The intersectionality framework requires planners to first acknowledge and confront how systems of power (i.e., matrix of domination) have influenced the problem of interest and the lived experiences of different populations and sub-populations. Urban planning is at the nexus of many systems, such as housing, transportation, environmental justice, economic development, and health. To build healthy communities, planners must understand who experiences the benefits and harms of planning decisions and how the distribution of these outcomes empowers or disempowers different groups, because these power relationships shape health inequities (Lapalme et al., Citation2020).

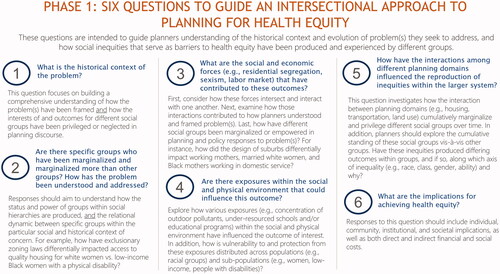

To help foster such an understanding, we provide a series of guiding questions planners should ask to understand inequities () and their role in addressing them () via an intersectional approach. To answer these questions, planners will need to examine the academic and policy literature as well as archival materials relevant to the issues at hand with a keen eye for how impacts of urban plans and policies compound for different groups according to their position within the matrix of domination. Planners should do so in conversation with key stakeholders, together exploring the social and distributional context and consequences of the problem in a reciprocal environment where authentic dialogue and thorough self-reflection can occur (Hankivsky et al., Citation2014; Innes & Booher, Citation2010). Using an intersectional approach provides a means for dialogue between planners and key stakeholders that is focused on exploring and interrogating how these systems of power are connected and experienced by different people. In turn, this can transform assumptions, beliefs, and goals by shifting away from conventional forms of thinking and practice to creative and innovative problem solving as well as a more equitable allocation of resources.

Figure 2. Four questions for evaluating planners’ roles in intersectional approaches to planning for health equity. Image of Black woman by Volha (Image #22430257 at VectorStock.com).

Strategy 2: Build Coalitions Within Communities and Across Organizations, Sectors, and Disciplines United by a Shared Vision for Social and Environmental Justice

An intersectional approach to urban health equity requires directly engaging with the power relations that drive social and economic inequities. Political neutrality is antithetical to the work of building a more equal society and only amounts to upholding the unjust status quo (Davidoff, Citation1965; Peattie, Citation1978). Therefore, planners need to enhance efforts to foster and build coalitions for health equity across different institutions, sectors, and social groups, using intersectionality as the “basis for unifying activity” (Crenshaw, Citation1989, p. 167; Zapata & Bates, Citation2015).

A fundamental element of developing a coalition that can effectively address health inequities is establishing a shared vision for justice. This, in turn, requires a shared understanding of the complex relationships among the systems (e.g., social, political, economic) that produced the inequities being addressed. This is where intersectionality is useful. For example, examining how different domains of planning (e.g., housing, transportation, land use) work within systems of power that produce different experiences for people shifts the focus from individual identities to systems of power that make “specific intersections of multiple oppressions affect each and everyone of us” (Roberts & Jesudason, Citation2013, p. 316). The goal is not to focus solely on one form of oppression at a time (e.g., White supremacy), but to “address a whole range of oppressions” (e.g., White supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy) because they are experienced simultaneously (The Combahee River Collective, Citation1977, p. 5).

Coalition building requires developing trust through repeated contact, conversation, and collective action. Throughout the coalition building process, the goal is to integrate perspectives from contextually relevant stakeholders to iteratively define the structure of the problem and co-design and identify opportunities to intervene, as well as learn and adapt actions as unanticipated issues arise (Brown & Wyatt, Citation2010). As ideas are generated with individuals and communities who are affected by urban planning decisions, an intersectional approach can help to both elevate their experiential knowledge and acknowledge their collective differences. Fostering mutual appreciation of what distinguishes their perspectives helps illuminate how structures of oppression are linked, in turn creating opportunities to identify shared areas of interest. Although all participants may not always agree on strategies and approaches, their strength is their diversity in knowledge and experiences. It then enables them to direct their efforts toward expanding their collective capacity as a system for social action that co-evolves and adapts as new challenges emerge.

Planning for health equity will require coalitions that center and build community power. Implementing a community power building approach to planning practice strengthens the collective capacity of stakeholders to address social, environmental, economic, and health inequities (American Planning Association, Citation2017; Corburn, Citation2009). We envision and hope that the enhanced consciousness about the uneven impacts of health challenges due to social and economic inequities in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the adaptive intersectoral responses that emerged (Abrams, Citation2020; Larson, Citation2021), along with similar urgency for intersectoral approaches to climate adaptation (Shi & Moser, Citation2021), serves as fuel for a renewed push for coalition building and collaboration across traditional planning domains, institutions, and actors. It is important for planners to evaluate these coalition actions, processes, and group dynamics to build a stronger evidence base about the most effective intersectoral strategies for health equity (Ndumbe-Eyoh & Moffatt, Citation2013).

Strategy 3: Apply Transdisciplinary and Co-Designing Approaches Throughout the Process to Generate Innovative and Creative Solutions That Will Mitigate Health Inequities

Urban planning governs processes that intertwine to shape the social determinants of health such as inequalities in housing and employment opportunities, proximity to social and health services, and the condition of the physical environment (Corburn, Citation2009). Planning for health equity will require systemic change, which in turn requires planners’ openness to paradigm shifts and new ways of understanding the problems before them. Existing tools from the public health field may be useful in this regard. One example of a framework that planners can use to design and guide collaborative approaches to addressing health inequities is the Culture of Health Action Framework (Chandra et al., Citation2017). The framework was designed to foster collaboration across traditionally health-focused sectors (e.g., healthcare and social services) and non-health-focused sectors (e.g., housing, education, transportation) in service of population health and health equity, and identifies four action areas: “(1) making health a shared value; (2) fostering cross-sector collaboration to improve well-being; (3) creating healthier, more equitable communities; and (4) strengthening integration of health services and systems” (Chandra et al., Citation2017, p. 2). Planners have important skills to bring to such efforts, such as community engagement, as well as discipline-specific knowledge about how structural inequalities are reproduced spatially, as in racial residential segregation.

Collaboration focused on achieving health equity requires an intersectional approach in three areas. First, planners within non-health-focused sectors need to recognize and understand the role their decisions play in producing upstream social and environmental stressors (e.g., housing precarity, environmental pollutants) that influence health outcomes in different ways for different people according to their positionality within the matrix of domination (Bullard, Citation1993; Gee & Payne-Sturges, Citation2004). Second, acknowledging the roles implicit and explicit biases, discrimination, and structural and institutional racism have explicitly played in the production of health inequities within and across sectors, policies, and practices is imperative (Bailey et al., Citation2017). Third, planners within non-health- and health-focused sectors should commit to an intersectional approach in all systems, laws, policies, practices, and procedures. Each sector can enact their commitment to achieving health equity by distributing resources through decision-making structures that are based on inclusionary co-design processes that include myriad perspectives and stakeholders. They can generate dialogue and ideas that may appear conflictual, but which enhance mutual understanding and reciprocity, and develop adaptive solutions and strategies from a people-centered approach that builds capacity and empathy by deeply understanding the community’s needs as opposed to only viewing things from a singular worldview (Innes & Booher, Citation2010).

Strategy 4: Use Existing Tools to Evaluate the Impact of a Program, Policy, or Initiative on Advancing Equity

An intersectional approach to planning for health equity is aligned with the American Planning Association’s (2019) policy guide Planning for Equity, which recommended adopting an “equity in all policies” approach to planning practice (p. 6). An equity-in-all-policies approach confronts planning practices and policies that differentially affect populations and subpopulations across a range of issues within planning, such as gentrification, environmental justice, climate change, and housing (American Planning Association, Citation2019). However, applying an intersectional approach takes the “equity in all policies” approach one step further by illuminating how structures of disadvantage create compounding burdens for individuals with multiple and intersecting marginalized identities. Employing this step is crucial for producing equitable actions that will address interlocked social, economic, and environmental inequalities, and corresponding health inequities.

Within the field of urban planning, there are many tools used to critically assess the future outcomes of present-day decisions, such as scenario planning (Chakraborty & McMillan, Citation2015), environmental impact assessments (Canter, Citation1996), and health impact assessments (Lock, Citation2000). However, equity is not intrinsic to any of these tools. Explicitly integrating equity into planning’s existing tools using an intersectional approach is a necessary strategy for addressing the complex structural factors that influence health equity. For example, the purpose of the Equity-focused Health Impact Assessment (EHIA or HEIA) is to reduce the potential of decisions and interventions from exacerbating health disparities and inequities by determining how institutions, sectors, and policies are connected to the changes being assessed (Branka, Citation2019; Mahoney et al., Citation2004). Intersectionality is a useful complement to such tools because it helps shed light on who is most vulnerable to the changes being assessed and why. EHIA frameworks have five main objectives: 1) center “equity and the reduction of inequities in health on the planning and policy agenda” (Mahoney et al., Citation2004, p. 3); 2) routinely identify unintended (positive and negative) healthy equity impacts of decision-making on different populations (Sohn et al., Citation2018); 3) support equity-based improvements in policy, planning, or programs; 4) embed equity within institutional decision-making processes; and 5) improve awareness and capacity efforts to address health equity at all levels within the institution. Planners may also look to frameworks from public health like the Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Framework for guidance on operationalizing intersectionality theory in practice (Hankivsky et al., Citation2014).

We recommend planners make similar efforts to integrate equity into the existing assessment and evaluation tools that are applied to policies, practices, and procedures throughout the planning process. From an intersectional perspective, doing so can help planners illuminate and interrogate the ways that planning processes and outcomes reinforce or alleviate intersecting oppressions. Planners then need to identify steps that must be taken to address the social inequities that impede developing healthier cities. A crucial dimension of such questions is who is empowered—and who is disempowered—by urban plans and policies, and we recommend that planners focus their actions on addressing the power imbalances illuminated via the application of these tools.

Conclusion

Intersectionality is a necessary ingredient in planning for health equity. We have provided four strategies that planners can use to develop an intersectional approach to planning for health equity. Merely focusing on improving overall health outcomes overlooks critical imbalances in resources and power within urban populations, which risks perpetuating the social and economic inequities that impede better population health. Instead, planners need to understand how different social categories and hierarchies intersect to shape how the social and environmental determinants of health differentially affect groups in distinctive ways. Furthermore, planners must intervene with an explicit focus on alleviating disparities and inequities between groups. An intersectional approach is an essential and effective strategy for achieving these two goals.

RESEARCH SUPPORT

This work was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholars Program under grant no. 73911. This work was also funded, in part, by the Intramural Program at the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Z1AES103325 to C.L.J.] and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers and editor for their feedback, which greatly improved this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Patrice C. Williams

PATRICE C. WILLIAMS ([email protected]) is a research scientist in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and formerly an intramural postdoctoral fellow in the Epidemiology Branch (EB) at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) with research interests in how physical and social environments contribute to health inequities.

Andrew Binet

ANDREW BINET ([email protected]) is a postdoctoral fellow in DUSP at MIT with research interests at the intersection of urban planning and community health.

Dana M. Alhasan

DANA M. ALHASAN ([email protected]) is an intramural postdoctoral fellow in EB at NIEHS and investigates how the physical and social environment influences health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease and dementia.

Nyree M. Riley

NYREE M. RILEY ([email protected]) is an intramural post-baccalaureate fellow in EB at NIEHS with research interests in how the physical and social environment contributes to access to resources needed to provide and maintain a healthy life.

Chandra L. Jackson

CHANDRA L. JACKSON ([email protected]) is an Earl Stadtman Investigator in EB at NIEHS with an affiliation at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities with research interests in how the physical and social environments influence racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in cardiometabolic dysfunction.

References

- Abrams, A. (2020, November 6). Health care and community development partnerships in the time of COVID-19. Shelterforce. https://shelterforce.org/2020/11/06/health-care-and-community-development-partnerships-in-the-time-of-covid-19/

- Aguayo-Romero, R. A. (2021). (Re)centering black feminism into intersectionality research. American Journal of Public Health, 111(1), 101–103. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306005

- American Planning Association. (2017). Healthy communities policy guide. https://planning-org-uploaded-media.s3.amazonaws.com/document/Healthy-Communities-Policy-Guide.pdf

- American Planning Association. (2019). Planning for equity policy guide. https://planning-org-uploaded-media.s3.amazonaws.com/publication/download_pdf/Planning-for-Equity-Policy-Guide-rev.pdf

- Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

- Bauer, G. R. (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62(3), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657316

- Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality–an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750

- Bowleg, L. (2021). Evolving intersectionality within public health: From analysis to action. American Journal of Public Health, 111(1), 88–90. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306031

- Branka, A. (2019). Promising practices in equity in mental healthcare: Health equity impact assessment. HealthcarePapers, 18(2), 42–47. https://www.longwoods.com/product/25921

- Braveman, P. (2014). What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Reports, 129 (Suppl 2), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S203

- Brown, T., & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Development Outreach, 12(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29

- Bullard, R. D. (1993). Race and environmental justice in the United States. Yale Journal of International Law, 18(1), 319–335. https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjil/vol18/iss1/12

- Canter, L. W. (1996). Environmental impact assessment. McGraw-Hill.

- Chakraborty, A., & McMillan, A. (2015). Scenario planning for urban planners: Toward a practitioner’s guide. Journal of the American Planning Association, 81(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2015.1038576

- Chandra, A., Acosta, J., Carman, K. G., Dubowitz, T., Leviton, L., Martin, L. T., Miller, C., Nelson, C., Orleans, T., Tait, M., Trujillo, M., Towe, V., Yeung, D., & Plough, A. L. (2017). Building a national culture of health: Background, action framework, measures, and next steps. Rand Health Quarterly, 6(2), 3–3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5568157/

- Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

- The Combahee River Collective. (1977). A black feminist statement: The Combahee River Collective.

- Corburn, J. (2009). Toward the healthy city: People, places, and the politics of urban planning. MIT Press.

- Corburn, J., Curl, S., Arredondo, G., & Malagon, J. (2015). Making health equity planning work: A relational approach in Richmond. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15580023

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 8. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978187

- Davis, A. (1981). Women, race & class. Random House.

- Duran, D. G., & Pérez-Stable, E. J. (2019). Novel approaches to advance minority health and health disparities research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S8–S10. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304931

- Fincher, R., & Jacobs, J. (Eds.). (1998). Cities of difference. The Guilford Press.

- Frisch, M. (2015). Finding transformative planning practice in the spaces of intersectionality. In P. Doan (Ed.), Planning and LGBTQ communities: The need for inclusive queer spaces (pp. 12–146). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Gee, G. C., & Payne-Sturges, D. C. (2004). Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environmental Health Perspectives, 112(17), 1645–1653. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7074

- Goetz, E. G., Williams, R. A., & Damiano, A. (2020). Whiteness and urban planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(2), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1693907

- Hankivsky, O., Grace, D., Hunting, G., Giesbrecht, M., Fridkin, A., Rudrum, S., Ferlatte, O., & Clark, N. (2014). An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: Critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-014-0119-x

- Harris, C. I. (1993). Whiteness as property. Harvard Law Review, 106(8), 1707–1791. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341787

- Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2010). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Routledge.

- Kapilashrami, A., & Hankivsky, O. (2018). Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. The Lancet, 391(10140), 2589–2591. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31431-4

- Lapalme, J., Haines-Saah, R., & Frohlich, K. L. (2020). More than a buzzword: How intersectionality can advance social inequalities in health research. Critical Public Health, 30(4), 494–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1584271

- Larson, S. (2021, September 3). Housing organizations pivot to provide COVID testing and vaccinations. Shelterforce. https://shelterforce.org/2021/09/03/housing-organizations-pivot-to-providing-covid-testing-and-vaccination/

- Lock, K. (2000). Health impact assessment. BMJ, 320(7246), 1395–1398. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7246.1395

- Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outside: Essays and speeches. Crossing Press.

- Mahoney, M., Simpson, S., Harris, E., Aldrich, R., & Stewart Williams, J. (2004). Equity-focused health impact assessment framework. ACHEIA.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Forum for Children’s Well-Being: Promoting Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health for Children and Youth; Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity; Tracey, S. M., Kellogg, E., Sanchez, C. E., & Keenan, W., Rapporteurs. (2019). Introduction to health equity and social determinants of health. In W. Keenan, C. E. Sanchez, E. Kellogg, & S. M. Tracey (Eds.), Achieving behavioral health equity for children, families, and communities: Proceedings of a workshop. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25347

- National Council on Disability. (2015). Breaking the school-to-prison pipeline for students with disabilities. https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/NCD_School-to-PrisonReport_508-PDF.pdf

- Ndumbe-Eyoh, S., & Moffatt, H. (2013). Intersectoral action for health equity: A rapid systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1056. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1056

- Osborne, N. (2015). Intersectionality and kyriarchy: A framework for approaching power and social justice in planning and climate change adaptation. Planning Theory, 14(2), 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095213516443

- Peattie, L. R. (1978). Politics, planning, and categories: Bridging the gap. In R. W. Burchell & G. Sternlieb (Eds.), Planning theory in the 1980s: A search for future directions (pp. 83–93). Center for Urban Policy Research, Rutgers University.

- Poteat, T. (2021). Navigating the storm: How to apply intersectionality to public health in times of crisis. American Journal of Public Health, 111(1), 91–92. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305944

- Powers, S. L., Lee, K. J., Pitas, N. A., Graefe, A. R., & Mowen, A. J. (2020). Understanding access and use of municipal parks and recreation through an intersectionality perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 51(4), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2019.1701965

- Pulido, L. (2017). Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence. Progress in Human Geography, 41(4), 524–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516646495

- Roberts, D., & Jesudason, S. (2013). Movement intersectionality: The case of race, gender, disability, and genetic technologies. Du Bois Review, 10(2), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X13000210

- Rodó-de-Zárate, M. (2014). Developing geographies of intersectionality with relief maps: Reflections from youth research in Manresa, Catalonia. Gender, Place & Culture, 21(8), 925–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.817974

- Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: The forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing Corporation.

- Sandercock, L. (1998). Towards cosmopolis: Planning for multicultural cities. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Sandercock, L. (2000). When strangers become neighbours: Managing cities of difference. Planning Theory & Practice, 1(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350050135176

- Shi, L., & Moser, S. (2021). Transformative climate adaptation in the United States: Trends and prospects. Science, 372(6549), eabc8054. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc8054

- Sohn, E. K., Stein, L. J., Wolpoff, A., Lindberg, R., Baum, A., McInnis-Simoncelli, A., & Pollack, K. M. (2018). Avenues of influence: The relationship between health impact assessment and determinants of health and health equity. Journal of Urban Health, 95(5), 754–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0263-5

- Steil, J. (2022). Antisubordination planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18815739

- Thomas, J. M. (1997). Redevelopment and race: Planning a finer city in postwar Detroit. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2014). Civil rights data collection: Data snapshot (school discipline). https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-discipline-snapshot.pdf

- Williams, D. R., & Collins, C. (2001). Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports, 116(5), 404–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7

- Williams, R. A. (2020). From racial to reparative planning: Confronting the white side of planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2020, 0739456X2094641. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20946416

- Zapata, M. A., & Bates, L. K. (2015). Equity planning revisited. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 245–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15589967