Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

In the Pacific Northwest, immigration has brought about unprecedented demographic changes. In this study we investigated the urban governance practice of including members of the public on collaborative governing bodies (e.g., committees, boards, planning commissions) among first- and second-generation immigrants in Oregon. We conducted 46 semistructured interviews with immigrant members of collaborative governing bodies throughout Oregon and found that the culture of a body has multiple impacts on a participant’s satisfaction and productivity. Evidence of the mitigating role culture plays (related to an individual’s sense of accomplishment and positive association) centered on participants’ reported influence on the body itself and on the practices and policies of the community at large during their service. The findings also suggest that informal activities before, in between, or after official business were equally as important to building a culture of productivity as any formal training that members received.

Takeaway for practice

Planners must encourage body members and others in leadership roles to develop a core belief that nurturing the culture of the body is key to enhancing members’ feelings of influence. This approach should include an investment of resources in hosting extensive orientations that acquaint new members with the technical components of the work and with meeting procedures, and existing members with the value of storytelling during deliberation. The results of this study can inform future planners about the intricate qualities that make or break the culture of a governing body, including its members and staff.

We investigated the participation of first- and second-generation immigrants in collaborative governing bodies (e.g., advisory committees, boards, planning commissions) in Oregon. Our research addressed the following questions: What variables do immigrant participants identify as shaping the culture of their respective collaborative governing bodies? How do these variables relate to participants’ reported level of engagement and influence? What factors do participants identify as challenges to service? This cross-sectional study (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017) included inventories of boards and individuals, participant interviews, online research, and quantitative and qualitative analyses, building on previous efforts to document membership on bodies, such as planning commissions. Across 10 topical areas, we documented challenges faced by immigrants sitting on collaborative governing bodies in 21 counties in Oregon, each of which had an immigrant population of at least 4%.

In the United States, diversification has been most pronounced in communities that until the 21st century had been predominantly White (García et al., Citation2019). This includes Oregon (American Immigration Council, Citation2020), which, between 1844 and 1857, passed several exclusionary laws against African Americans (Tichenor, Citation2021). Since then, Oregon, like much of the Northwest, has remained largely White, but in the past 20 years, the state and the region, which are primarily rural with more permanent migrant workers (Arcury & Quandt, Citation2011; Lichter et al., Citation2018), have slowly diversified. This growth in racial diversity has been driven primarily by immigrants. In 2020, 10% of Oregon’s population identified as immigrants, with 11% of native-born residents having at least one immigrant parent (American Immigration Council, Citation2020).

We begin with a review of the literature on participatory planning and urban governance, identifying a lack of research on collaborative governing bodies and the role of group culture in these bodies. We then describe the semistructured interviews we conducted between November 2019 and March 2020, in which immigrant participants discussed their experiences on collaborative governing bodies. The interviews captured a range of perspectives on structural and personal challenges and opportunities, offering insights into key factors that expanded or restricted members’ service and sense of influence.

In the findings section, we describe how the culture of a body affected participants’ experiences. We present evidence of the effect of culture on members’ productivity and perceived influence (or lack thereof) during their service: influence on the body itself and on the practices and policies of the community at large. We also highlight the ways in which staff influenced body culture and participants’ sense of influence. We discuss the multiple factors that positively influenced immigrant participants in their respective bodies when their perspectives were centered. These factors included perceived psychological safety, the willingness of the group to make proceedings less formal as needed, and the application of an equity lens. We show how providing informal time in between the business of collaborative governing bodies yielded multiple benefits, including relationship building, which was linked to how the culture felt to participants, how they reported influence, and participants’ expansion of networks. Networks also influenced the recruitment of new participants and, by default, how participants reported their own recruitment to their positions. We conclude with a set of heuristics that planning practitioners and other staff can follow to ensure that the governing bodies they oversee are equally welcoming, inclusive, and productive, reflecting an anti-racist equity approach.

Engaging the Public: Participatory Planning Versus Urban Governance

Prior research has highlighted the multiple ways public involvement has been used in planning and policy processes (Laurian & Shaw, Citation2009). The planning literature has focused heavily on broad public participation in developing plans; equally important, however, is deliberation on planning projects, often through boards and commissions. Gastil (Citation2000) framed deliberation as “discussion that involves judicious argument, critical listening, and earnest decision making” (p. 22), though Mansbridge et al. (Citation2006) contended that deliberation can include both binding decisions as well as advisement, the latter being the case for many of the deliberative bodies in our study. For this study, we distinguish between two buckets of public engagement research—participatory planning and urban governance—which typically use deliberative methods for engaging the public.

PARTICIPATORY PLANNING

Many studies have examined participatory planning processes related to public outreach or community engagement (García et al., Citation2019; Rosen & Painter, Citation2019). They have centered predominantly on gathering input (Meléndez & Martinez-Cosio, Citation2019, Citation2021) or the inclusiveness phase of public involvement (Smith, Citation2009). This matters for outcomes, because Loh and Kim (Citation2021) found that local government comprehensive plans involving “multiple modes of gathering public input…were significantly more equity-focused” (p. 191).

Participatory processes require considerable resources, especially if they include underrepresented voices in this phase of planning (C. A. Lee, Citation2019), where power differentials manifest. Indeed, participatory processes represent invited spaces (often local) with many forms of power at work, some visible (e.g., observable decision making), some hidden (e.g., political agenda setting), others invisible (e.g., the shaping of meaning and what is acceptable; Gaventa, Citation2005). According to Gaventa (Citation2005), individuals are invited into such spaces by government or other powerholders in one-time or ongoing efforts to expand participation in what previously had been closed spaces. However, because these spaces have historically been accessible primarily to White privileged males, the values and outcomes of decisions in these spaces have become normalized, largely benefiting their interests.

In participatory planning spaces, language is at the heart of communicative engagement (Habermas, 1962/Citation1991; Young, Citation1996). Through spoken and written language, interests, visions, and concerns are communicated and incorporated (or not) in planning and policy outcomes and resource allocations (Briggs, Citation1998; Meléndez & Parker, Citation2019). This is the essence of communicative rationality (Williams, Citation2020), planning that focuses on argumentation and the rational/deliberative elements of that discourse to convince others of objective evidence to make decisions. However, prior research has shown how limiting these processes/spaces become due to the uneven allocation of resources to underrepresented communities (Meléndez, Citation2021; Zapata & Bates, Citation2015).

Many jurisdictions have tried to increase immigrant diversity in public participation by conducting outreach in multiple languages and attending to cultural nuances, for instance (García et al., Citation2019; Rojas, Citation2014). Most of these efforts have concentrated on the input phase of engagement. Yet, decades of planning practice have shown that diversity solely at the input phase tends to benefit those who are already privileged and who are most likely to control the decision-making phase, thus maintaining White-centered approaches to planning (Goetz et al., Citation2020).Footnote1

URBAN GOVERNANCE

Avis (Citation2016) defined urban governance as “the process by which governments…and stakeholders collectively decide how to plan, finance and manage urban areas” (p. 1). It is part of a larger “move from government to governance” (Taylor et al., Citation2010, p. 145), a shift toward greater citizen control (Arnstein, Citation1969) and public engagement in planning and other spheres of government (Bickerstaff & Walker, Citation2005; Brody et al., Citation2003; Margerum, Citation1999, Citation2002), both core values in planning (Beard & Sarmiento, Citation2014).

However, very little planning research has examined the inner workings of collaborative governing bodies (Innes & Booher, Citation2004). The few exceptions have found that certain occupations were overrepresented in planning commission membership and that racialized minorities were underrepresented (Maclaren et al., Citation2017; Mitchell, Citation1997; Sanders & Getzels, Citation1950). Though dated, one of these studies (Sanders & Getzels, Citation1950) investigated the landscape of planning commission demographics but did not address the structures that limit representative participation.

The few insights into collaborative governing bodies have centered largely on administrative and legal requirements and practices, like running meetings, gathering public input, and increasing transparency (Adams, Citation2004; Innes & Booher, Citation2004). In our literature review, we found little documentation of the intricacies of board makeup and conduct (including efforts to diversify participation) that increase or limit socioeconomic diversity during the decision-making phase(s) of planning processes. This includes a research gap in how culture affects the sustained engagement of underrepresented groups in urban governance.

The Impact of Board Culture

In this study, we expanded notions of when and where deliberation begins to include the culture that group members create. Culture comprises traditions and habits that guide behavior (Fine, Citation2012). In the context of our research, this includes board norms: procedures for engagement and the kinds of arguments valued within a body. Such norms encompass the visible and invisible ways members relate to one another and create a group atmosphere—often referred to as satisfaction—and how they progress toward their goals (i.e., productivity; Mansbridge et al., Citation2006).

Because public deliberation is an idealized category within the broader concept of discursive participation (Carpini et al., Citation2004), we focused on descriptors that participants attached to group relationships, feelings, and impact. In talking with other board members, individuals get to know one another, learn why members serve, discover others’ values and passions, and highlight shared concerns or viewpoints. Although the literature has tended to describe deliberation as a formal process, some see it as gradual, occurring in informal ways and places (Carpini et al., Citation2004), that combines cognition (reasoning) with culture (meaning making) and “looks more like storytelling than argumentation” (Ryfe, Citation2005, p. 58). Many studies have found a close connection, in small groups, between productivity and positive atmosphere, “such as mutual trust, respect, and norms of open discussion” (Mansbridge et al., Citation2006, p. 17; see also Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014; Jehn & Mannix, Citation2001). Echoing Solis’s (Citation2020) call for racial equity in planning organizations, we believe that studying cultural norms is critical to understanding how they may prevent or limit authentic participation, namely by immigrant members, within a collaborative governing body. Moreover, by applying an anti-racist lens (E. Lee, Citation1998), practitioners can center racial and ethnic identities that have historically been excluded or given substandard access to resources in planning practices and policy outcomes.

The relationship between a group’s culture and who comprises that group is indisputable (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Planning researchers have noted that the membership of collaborative governing bodies is often self-selecting, with existing structures favoring traditionally privileged people over historically marginalized communities (Innes & Booher, Citation2004; Knaap et al., Citation1998). In addition, studies of nonprofit boards have shown that the ability of diverse members to positively affect a board is enhanced by a culture that fosters inclusive behaviors (Buse et al., Citation2016). To achieve these behaviors, a board culture must have in place “accompanying diversity policies and practices” (Buse et al., Citation2016, p. 188), without which diversity may in fact be counterproductive to members’ sense of satisfaction and productivity.

How immigrants perceive their influence on collaborative governing bodies is especially important because immigrants often lack meaningful representation at all levels of government (Nishishiba, Citation2012; Riccucci & Van Ryzin, Citation2017). Research has suggested that the practice of appointing immigrants to local boards and commissions increases their influence on policymaking and can encourage them to seek higher office (Hafer & Ran, Citation2016; Quick & Feldman, Citation2011; Ramakrishnan & Lewis, Citation2005). However, without actual changes in body practices related to culture, the diversity celebrated by much planning literature will remain stuck at the input phase of participatory processes, thereby limiting who participates in the decision-making phase. This will perpetuate White planning interests and virtually guarantee that progressive equity goals remain elusive given the lack of a racial focus on differences that matter in deliberative bodies (Goetz et al., Citation2020; Williams, Citation2020).

Methodology

Research Design

We investigated the engagement of first- and second-generation immigrants on collaborative governing bodies in a state facing significant demographic shifts. Our study was part of a larger cross-sectional study (Meléndez et al., Citation2021) integrating mixed methods data collection and analysis (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017). The research was conducted in two phases. In Phase 1, we identified collaborative governing bodies across various categories and jurisdictions in Oregon and created an inventory of first- and second-generation immigrants represented on those bodies. In Phase 2, we conducted 46 interviews with immigrant members identified in Phase 1.

PHASE 1: INVENTORIES

Phase 1 began in the fall of 2019 with an assessment of immigrant engagement in collaborative governing bodies, which yielded two inventories. Using data from online searches of jurisdictions across Oregon, we created a statewide board inventory consisting of information related to geography, type of jurisdiction, topical focus, availability of board roster information, number of immigrants on the board, and the decision-making authority of each body.

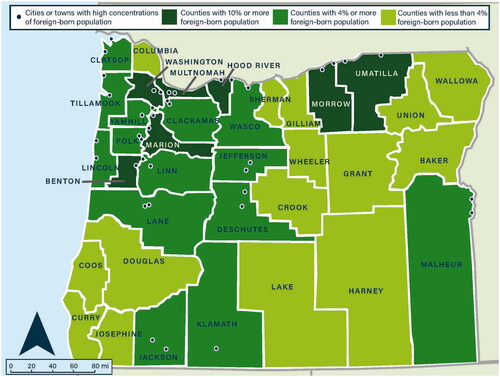

The board inventory focused on the 21 Oregon counties (out of a total of 36) where foreign-born individuals represented at least 4% of the total population (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2018). The 4% baseline allowed us to identify a cross-section of Oregon counties as well as cities with large immigrant populations, for a total of 54 geographies ().

Figure 1. Percentage of foreign-born individuals across Oregon by county. Source: Reprinted with permission from Meléndez et al., Citation2021.

The board inventory yielded a total of 504 bodies, comprising 10 board categories, all focusing on basic needs (e.g., housing and public health; Meléndez et al., Citation2021). The bodies varied by type and authority; some had decision-making power, whereas others were tasked with making recommendations to other decision makers (Technical Appendix A).

We also gathered demographic data for an inventory of individuals who identified as first- or second-generation immigrants serving on collaborative governing bodies. Once an individual was verified as being an immigrant—through either self-identification via their online public profile or our follow-up with their board’s key contact—we added them to the member inventory (Meléndez et al., Citation2021).Footnote2 summarizes the immigrant representation within the categories of bodies we investigated.Footnote3

Table 1 Category data and immigrant representation findings.

It is important that we acknowledge our inclusion of both first- and second-generation immigrants in our inventory. Though second-generation immigrants are native born, naming conventions are layered and complex, raising questions, for instance, about whether second-generation immigrants should be considered hyphenated Americans or just Americans. Nevertheless, as noted by Bourdieu (Citation1991), through his focus on language and naming practices, and Butler (Citation1999), examining the role of performativity, what one is called is political. It “highlight[s] the contestation around meanings and how naming practices provide an arena for different actors to compete over the drawing of the symbolic borders of social inclusion/exclusion” (Antonsich, Citation2022, p. 1081). The demographic naming convention of second-generation carries sociological power because it implies access to full participation in the society to which one’s parents decided to immigrate (Schneider, Citation2016). Yet, such access is an ideal that can be limited by discrimination, marginalization, and/or social isolation (Antonsich, Citation2022). Native-born individuals may indeed identify as second-generation immigrants to claim the immigrant experience, not as a problem of integration but as a point of pride associated with their parents’ immigration experience and to challenge nativist efforts to erase such cultural pride.Footnote4

PHASE 2: INTERVIEWS

In Phase 2, we conducted 46 semistructured interviews with immigrant members serving on collaborative governing bodies. Because the public’s perspective has been understudied in public engagement research (Hafer & Ran, Citation2016), we reasoned that immigrant members, rather than staff, would be better suited to speak to immigrant experiences on collaborative governing bodies. Of the 46 interviewees, 34 identified as first-generation immigrants and 12 identified as second-generation.

For the analysis of interviews, the research team created a coding guide using inductive reasoning based on the interview questions and anticipated themes and research outcomes (Miles et al., Citation2014). This guide outlined different concepts, their definitions, and examples of their operationalization within interview transcripts. For example, interviewees who commented that their body’s meetings were “formal” were coded as “process: meetings” if the comment described standards and norms or as “culture” if the comment also included talk related to feelings and values that affected board meetings and work. Coding was conducted using NVivo software (QSR International, Citation2020). Following the first round of coding, the team revised the initial guide based on data from the transcripts, memos, and concept mapping (Saldaña & Omasta, Citation2017). All transcripts were then coded by two different members of the team, and intercoder reliability was performed within NVivo, whereas transcripts with kappa scores <0.75 were reconciled through intercoder discussion and reviewed against the definitions outlined in the coding guide (McHugh, Citation2012).

Analyzing Culture and Influence Within Collaborative Governing Bodies

A third round of coding focused on how interviewees reported the impact of their governing body’s culture and the extent of their influence. This focus was crucial given the push to diversify bodies in once-homogenous jurisdictions, like Oregon, that are experiencing unprecedented demographic shifts. We first reviewed the interview transcripts in NVivo for key codes from the first two rounds of coding (see Technical Appendix B for interview details). Two related codes emerged: “culture” and “influence.” We then looked more granularly at these two codes, examining other applied codes within them (Technical Appendix B).Footnote5 Each team member took notes on their respective codes in the first round, identifying interviewees who discussed culture as supporting influence and those who did not. In the second round of coding, the coauthors identified themes and discussed key elements from each theme (Mansbridge et al., Citation2006). In so doing, we arrived at more specific themes that allowed us to address our research questions.

LIMITATIONS

Although our inventories are arguably the most comprehensive of their kind for Oregon, they are by no means complete because we did not receive responses from multiple jurisdictions. And though the study’s findings are limited by the sample size, they nevertheless illuminate challenges and opportunities that other planners would likely uncover if they asked similar questions.

FINDINGS

The findings discussed in this section relate to experiences described by immigrant members of collaborative governing bodies in Oregon. present examples of interview excerpts that highlight the codes and categories of findings relevant to our analysis.

Table 2 Examples of coded interview excerpts: Culture.

Table 3 Examples of coded interview excerpts: Influence.

Table 4 Examples of coded interview excerpts: Other challenges.

CULTURE

Culture had a critical impact on immigrants’ experiences on collaborative governing bodies, particularly in relation to perceived levels of satisfaction and productivity. Body members indicated satisfaction through discussion about group atmosphere and about their ability to relate to fellow members. Productivity was manifested in comments about mutual trust and open dialogue between and among members and about the ability to meet the body’s goals, which were often achieved by applying an equity lens. An equity lens encourages individuals to take on others’ perspectives, especially those most affected by the work of the body, namely, historically marginalized individuals and communities. In the context of a body’s culture, interviewees’ levels of satisfaction and productivity appeared to affect their perceived level of influence (both internally and externally) in indirect and positive ways.

Culture and Satisfaction

Interviewees discussed the atmosphere of their governing body and how (or whether) they were able to relate to other members. When a body created informal spaces for members to interact and learn more about each other, interviewees indicated that this reinforced relationships and led to a more fulfilling experience. For example, one member of a race, equity, and human rights body commented that this informality infused the culture, encouraging members to share experiences and knowledge relevant to the body’s activities. For this member, the body’s inclusive environment was directly connected to becoming more familiar with one another outside formal proceedings. This is important because immigrants on these bodies are often the only individuals in the group to hold that identity. Having the ability to bring their full selves to their role was a validating experience that helped members relate to each other but presented a struggle to others who felt they could not. Likewise, another member of a budget body suggested that knowing the other board members made them feel more comfortable being themselves.

An often-cited obstacle to immigrant members’ satisfaction was the use of Robert’s Rules of Order (RRO). Fourteen of the 46 interviewees indicated that they used RRO in their collaborative governing bodies; another 13, though they did not name RRO explicitly, referred to a formal way of conducting business that shared elements commonly associated with RRO.Footnote6 Eight of the 27 participants who used RRO or a similar meeting protocol described it as intimidating and constraining to their participation. As one transportation body member commented, “It just seems like a very White set of rules…it just is culturally,…so I just wonder if [RRO] is the best way to engage if you want a more culturally diverse board.”

However, we found that the intimidating effect of parliamentary procedures was counteracted when the culture of a collaborative governing body included informal elements. Of those who used RRO but did not name it as a barrier, 59% cited some level of informality in their board’s culture. For example, one budget body member indicated that, because they were not as familiar with RRO, they no longer adhered to its formality as they had before. A shift to less procedural rigidity, even while still using RRO, allowed members to get to know one another outside of formal business. Our findings suggested that what happens before, between, or after formal meetings supports the productivity of sessions because members can enjoy the people they serve with while also attending to business. As the previous examples highlight, when informality and space for social connections are infused within existing parliamentary procedures, the intimidating and constraining effects of these procedures can be mitigated.

Culture and Productivity

We investigated the specific cultural components affecting immigrant members’ reported productivity, which we defined as their ability to meet stated goals. In this sense, culture is linked to group norms of mutual trust, respect, and open discussion. Interviewees identified annual celebrations and opportunities to recognize each other’s commitment to their community as cultural components that amplified norms of mutual respect. For instance, one planning and zoning body member connected productivity with both the interactions between members and the feeling of getting things done (cultural productivity).

Interviewees also noted they were permitted or encouraged to use an equity lens in their service work, which increased mutual trust and open discussion. When non-White immigrants brought different perspectives to objective and rational discourse, an equity lens helped validate their expertise and ways of communicating. Informal discussions of equity made such conversations easier in formal environments, furthering body members’ values as they shared their experiences.

One Middle Eastern/North African member of an education body described the utility of an equity lens: “Fortunately, I’m not the only one who is bringing that lens. Even my fellow White board members mention that and focus on that as well.” Similarly, a White member of a budget body commented that the “verbal jujitsu” of discourse was eased for non-White members when the entire body used an equity lens.

Nine participants indicated they used an equity lens in their work, but we found that only one of the nine (11%) served on a planning board. One Latino parks and recreation body member noted that the ability of members to call for differentiated resource allocation or a new policy focus was often a reason why members decided to join their respective bodies. Such findings suggest that a culture of satisfaction and productivity alleviated discomfort for members, who have taken the time to develop a sense of shared purpose. The informality and equity focus of many body cultures increased members’ abilities to relate to others (satisfaction) and create mutual trust (productivity). These factors also helped increase members’ sense of influence.

INFLUENCE

Our analysis revealed that the components that made a body’s culture satisfying and productive for immigrants also amplified their perceived influence. Interviewees referenced two forms of influence: internal influence, whereby members affected the inner workings of the body or other members; and external influence, whereby members felt they helped achieve the body’s overall goals and affect the broader public.

The role of staff within a body’s culture was a crucial component that either limited or amplified immigrant members’ influence on collaborative governing bodies. Seven of the 18 interviewees who felt they had internal or external influence named specific staff practices that allowed them to exert that influence over the body’s activities. These practices included providing orientations, facilitating opportunities for mapping expectations and priorities for the body, and acting as connective tissue between the body and other relevant agencies or elected officials. Interviewees who coordinated with staff to create opportunities for the broader public to engage with the deliberation process also reported feeling higher levels of influence.

Internal Influence

We defined internal influence as the influence body members had on other members or on the deliberative process within the body. Interviewees emphasized the importance of receiving regularly occurring (e.g., annual, quarterly, etc.) opportunities to review relevant technical knowledge, programs, board procedures, expectations, or meeting activities. For instance, one budget body member commented that these opportunities for review and reflection influenced what materials were available for meetings. In their telling of the improvements made from year to year, what might be considered a small change—a one-pager—better prepared board members to critically engage with agency heads, as opposed to only receiving an overview of the previous year’s activities.

Conversely, the lack of opportunities to review relevant technical knowledge, programs, and expectations for dialogue or meeting activities left members feeling they were not influencing the internal work of the body. As one member of a transportation body suggested, this can constrain members’ capacity to engage in dialogue. This participant linked both their unfamiliarity with the body’s topic and the lack of space for setting expectations for internal communication with the absence of any regularly occurring review of the body’s internal activities. In turn, this limited members’ abilities to influence the internal workings of their body or to even participate in the body at all. As the two quotations from different budget board members exemplify, the right setup (e.g., orientation) or small tweaks (e.g., a one-pager) can have a considerable impact on internal influence.

External Influence

We defined external influence as influence affecting the community at large or the target audience of a body’s work; that is, the subject of the influence is public-facing activities, not fellow members or body procedures. Thus, members who discussed their impact on a new piece of legislation or their support for the community they represented were categorized under external influence.

Interviewees discussed the limitations of external influence when the body’s members were discouraged by staff from interacting with the public or other agencies relevant to their work. Not surprising, when members felt they lacked internal influence (e.g., not being able to determine the focus of a body), their sense of external influence was diminished or nonexistent.

Conversely, many interviewees noted that clear lines of communication among the body, relevant agencies, and elected officials helped increase their external influence. One race, equity, and human rights body member described the value of having ample opportunities to interact with agencies and public officials: “So, she’s a clear liaison between us and the city and the mayor.… In terms of this current homelessness situation, the sit-lie ordinance, we are working on coming up with ways to remove barriers for homelessness.” The ability of members to establish and cultivate relationships with outside power brokers was central to their perceived external influence. Interviewees noted that the freedom to take on priorities that were important to themselves, their community, and/or others on the board was critical to increasing their sense of influence. As one statewide housing body member explained, their personal experiences and identities drove their topical focus and helped them feel heard and validated.

Notably, even the mere presence of racial diversity on the body, accompanied by small procedural/behavioral changes, led to further external influence. One audit committee member highlighted the influence that welcoming marginalized communities into collaborative governing bodies had on the work. This interviewee, a Hispanic woman, reflected that her service, along with that of another female board member, externally influenced the Latino community’s perception of what leadership could look like, given the homogeneity of all other elected leadership positions in their city.

PERSONAL BARRIERS AND OTHER CHALLENGES TO SERVING

Interviewees also identified barriers to their overall participation on their respective bodies. These perceived barriers comprised two main categories: communication barriers and barriers related to imposter syndrome, or the self-perception that one does not hold the right credentials (e.g., education, background, experience, etc.) to participate in the deliberation process and therefore does not belong (see and ). We identified imposter syndrome as a theme that emerged from our coding of expressions of not belonging.

Table 5 Examples of barriers to serving.

As an Asian member of a health and human services body described, the feeling of not possessing the knowledge, expertise, or credentials for membership was intimidating and constraining. This imposter syndrome made some interviewees feel “small,” especially when participating in bodies lacking racial and cultural diversity. Many non-White interviewees noted that when they were the lone representative of their community on a body, they felt pressure to conform to existing modes of communication rather than preferred cultural ones. An education body member described a similar experience, evidencing the pressure that non-White members felt to silence their traditional ways of sharing knowledge in favor of the dominant methods employed historically in these bodies.

Discussion

The 504 collaborative governing bodies inventoried in our research made clear the extent to which this urban governance practice is used across jurisdictions in Oregon. Because bureaucratic diversity is rare in the state (Nishishiba, Citation2012), membership on these bodies was generally a meaningful experience for immigrants, given the potential to be represented in work affecting them and to influence policy (Meléndez et al., Citation2021). However, this kind of instrumental influence is difficult to achieve unless a body’s culture is both satisfying and productive. For participants in our study, the ability to achieve satisfaction and productivity aligned with how much internal and external influence they reported. As such, we believe the key components identified in our findings will help guide planners and key staff who are motivated to create and manage governance processes that are inclusive and influential.

The Role of Relationship Building in Mitigating Power Differentials

Despite their potential, urban governance processes often do not achieve collaborative participation for underrepresented individuals, especially during deliberation, because there are rarely structures in place to mitigate power differentials among participants (Fung, Citation2003; Quick & Feldman, Citation2011; Smith, Citation2009). As our findings suggest, one way to reduce these power differentials is to focus on the body’s culture. All of the bodies in our study would be classified as invited spaces within Gaventa’s (Citation2005) power cube, where invisible power is manifested through culture. Indeed, in this study, satisfaction and productivity were related to the perceived psychological safety (Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014) of immigrants who could be their full selves in making connections with other members. Without space for fostering genial relationships, whether before or after official business was conducted, the satisfaction and productivity reported by individuals were limited because they were unable to draw from their motivations for joining the body and they were uncertain how they fit in with their colleagues.

Researchers and practitioners must expand current notions about where the deliberative process begins. The goal of meeting communicative ideals while accounting for differences that matter during deliberation is difficult to achieve (Innes & Booher, Citation2004; Mansbridge et al., Citation2006; Young, Citation1996) if members do not take the time to learn about those differences informally, in spaces where they can share their values, motivations, fears, and backgrounds and publicly recognize others’ contributions to the body (Carpini et al., Citation2004). Multiple interviewees highlighted the importance of establishing strong relationships with fellow body members, which, among other outcomes, helped mitigate the intimidating aspects of RRO and other formal procedures. Planners and other staff who take the time to establish an inclusive culture that centers member satisfaction and productivity represent a step toward mediating more visible power structures, such as rules for engagement and agenda setting (Gaventa, Citation2005), as underrepresented members engage in the official business of their service.

The Complexity of Perceiving a Sense of Influence

Findings related to participants’ perceived influence also connect to the importance of establishing relationships with staff, other board members, and/or outside powerbrokers; of possessing basic knowledge about the purpose of the body; and the ability to revisit goals in a timely manner. We maintain that any changes in practice related to how members interact with one another and achieve outcomes will necessitate changes to normative practices that foreground White planning interests in collaborative governance processes. Adding underrepresented members without considering new modes of equitable practice will ultimately maintain the status quo.

The findings also illuminate factors that negatively affected influence. As one interviewee put it succinctly, “It[’s] been predominantly heteronormative, White, and male. There’s a lot of fragility, a lot of lack of understanding that impedes that conversation.” White fragility about equity issues, barriers preventing members from connecting with community, a lack of diversity in leadership positions, and a lack of orientation—all of these limitations help co-construct or maintain a “White space [that] is often understood by its inhabitants as neutral space that ‘naturalizes’ exclusion and privilege” (Goetz et al., Citation2020, p. 146). Many participants struggled to understand technical material and felt that the process represented a “baptism by fire,” as one housing body member put it. Therefore, we recommend that planners and staff invest resources in extensive orientations that acquaint new members with the technical components of the work and meeting procedures, including RRO. This will also allow new members to provide valuable input on the body’s activities and their own needs and priorities for participation. Trainings should also foreground how storytelling is a credible way to present evidence and contextualize arguments (Ryfe, Citation2005). At the very least, these trainings should offer stipends and childcare for participants (Meléndez et al., Citation2021).

In addition, planners and staff should not ignore that the informality that occurs before, in between, or after business is just as important as any formal training for members. As Buse et al. (Citation2016) noted, without accompanying practices to support the workings of a diverse board, members may experience a devaluing of their authentic selves or feel unproductive and therefore not influential. This reinforces Williams’s (Citation2020) notion of racial planning, or planning by state inaction, characterized by an inability to imagine conducting government business outside norms practiced since inception.

Yet, the conducive aspects of influence are significant, with multiple variables playing a role when members of underrepresented communities are centered in their respective governing bodies. These variables include applying an equity lens to organize priorities and communicate past accomplishments, connecting personal experiences and identities with official goals, and valuing the power of diverse representation. In fact, non-planning body members indicated productivity, influence, and the development of dialogic skills for valuing others’ perspectives related to an equity lens at a disproportionately higher rate than planning body members. Unsurprising, these are key skills supported by those who advocate for more equitable collaborative governance (Innes & Booher, Citation2004; Maclaren et al., Citation2017; Zapata & Bates, Citation2015).

An immigrant member’s positive participation on a collaborative governing body could represent a step in a longer civic engagement journey leading to higher office (Ramakrishnan & Lewis, Citation2005). Indeed, Meléndez et al. (Citation2021) argued that service boards represent a bridge between acts of local/cultural civic engagement and those associated with electoral politics, potentially awakening immigrants’ political imaginaries (Meléndez, Citation2021). Whether an immigrant member crosses this bridge may depend on them overcoming their initial imposter syndrome and gaining greater confidence in the value of their work, as reinforced by the culture of the body they serve on and their sense of influence.

The planning field’s inability (or reluctance) to imagine non-normative practices represents a significant challenge. We advocate for changes in practice that respond to the increased diversification of states and regions that, until recently, have historically been predominantly White. However, regardless of whether a place has become more diverse, most of the spaces where decisions are made remain White-centric, as they have been for centuries (Goetz et al., Citation2020; Williams, Citation2020).

REFLECTING ON WHAT MATTERS FOR PLANNERS

Based on our findings, we offer the following recommendations for planners and staff managing collaborative governing bodies:

Deliberately encourage historically marginalized racial communities to participate, because the presence of racial diversity coupled with inclusive practices can produce benefits.

Create an initial orientation for participants, using it as space to share and review basic technical knowledge as well as the mission and goals of the body. Give participants the opportunity to identify goals for participation and integrate these into the group’s work plan or agendas.

Create and allow for informal spaces (outside of formal proceedings) where participants can get to know one another professionally and personally. Host an annual retreat if possible.

Bring an explicitly equity lens to support participants in taking on others’ perspectives. Use this as an opportunity to encourage participants to share lived experiences.

Ensure that participants know staff can serve as connective tissue between the group and elected officials, stakeholders, and the general public. Encourage opportunities for connecting the group to these relevant partners and create clear lines of communication.

Modify RRO as needed so it acts as a tool for engagement that is accessible to all participants. Staff should ensure that an RRO (or any other parliamentary procedure used) tutorial is part of the formal orientation.

Implement ongoing celebrations to recognize the work of participants at regular intervals (when milestones are hit or at least annually).

Schedule regular (e.g., quarterly, biannually) check-ins with participants to revisit orientation materials or technical knowledge. Use this as an opportunity to check in with participants about needs. (This can be part of the focus of an annual retreat.)

Planners and other staff might view these takeaways for practice as standard recommendations for running effective and supportive working groups. However, it should be noted that many participants in our study indicated that multiple items in the preceding list were missing from their service experience. Thus, the creation of a body’s inclusive and productive culture should be approached as a learning environment that needs to be intentionally designed to achieve the desired outcomes (Meléndez & Parker, Citation2019).

As the planning field evolves, we hope it adopts an anti-racist lens focusing on the role of power in excluding, including, and meditating action not only in the moment but also historically and politically (E. Lee, Citation1998). Moreover, this anti-racist lens must be widened beyond general planning, zoning, transportation, housing, and parks to include other focal areas centering underrepresented communities, as called for by many researchers (Davidoff, Citation1965; Mitchell, Citation1997; Sanders & Getzels, Citation1950; Zapata & Bates, Citation2015). We believe this push to expand planners’ disciplinary focus relates to how they are trained, as evidenced by the growing emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion in planning programs. As a teaching tool, our study can be used to educate future planners about the intricate qualities that can make or break a group’s culture.

Yet, even if planners do not take the lead in non-planning domains, planners and the staff charged with assisting other types of non-planning-focused bodies should engage in frank anti-racist discussions about how the practices of each body support or inhibit the meaningful participation of immigrant members, particularly immigrants from non-White backgrounds. Although our research was limited by the number of interviewees across bodies, the recurrence of certain barriers was significant. Future studies could use a methodology like ours to investigate immigrant experiences on collaborative governing bodies in other states, coupled with staff interviews.

Although more expansive forms of urban governance are on the rise, the agreements reached through collaborative planning processes that lack representative or decision-making authority often end up in more formal authoritative or representative bodies, such as planning or land use commissions (Margerum, Citation1999, Citation2002). Thus, the success often touted by outreach efforts and other forms of community engagement during the input phase of participatory planning can still yield results that are business as usual. Without changing how these bodies are run in practice, White interests will remain the status quo, no matter what equity lens or language is applied.

RESEARCH SUPPORT

This research was made possible by the following University of Oregon resources: UMRP’s 2019–2020 grant supporting Engaging Diverse Communities, the 2020 College of Design Board Faculty Fellowship and Student Assistant Award, and the DEI 2022 Summer Writing Support Grant.

Technical Appendix

Download PDF (137.2 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank additional research team members Melissa Graciosa, Isabella Rivera Kjaer, Avalon Mason, Leah Rausch, and Alex Renirie. We also thank the editor, special issue guest editors, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive yet critical feedback. Last, our deepest gratitude goes to the interview participants who took the time to share their perspectives with us.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants in this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2121309.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

José W. Meléndez

JOSÉ W. MELÉNDEZ ([email protected]) is an assistant professor in the School of Planning, Public Policy, and Management at the University of Oregon.

Calvin G. Hoff

CALVIN G. HOFF ([email protected]) is a community and regional planning graduate student in the School of Planning, Public Policy, and Management at the University of Oregon.

Notes

1 Any in-depth literature review in transportation, housing, and land use–related planning efforts will highlight that when underrepresented communities voice concerns or offer suggestions in participatory processes, they are often ignored, to the detriment of those communities (e.g., Briggs, Citation1998; Goetz et al., Citation2020; Krumholz, Citation1982; Steil, Citation2022).

2 In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit as we were finishing our inventory of counties and special districts. Not surprising, once a statewide shutdown was ordered, much of our follow-up with staff went unanswered. Thus, we stopped Phase 1 of the research and moved on to Phase 2 out of consideration for the new reality that staff (and the wider public) were dealing with at the time. As with much research conducted during the pandemic, our research team had to grapple with whether we had enough data to analyze and report, which we felt we did.

3 See Meléndez et al. (Citation2021) for additional findings from Phase 1.

4 The interview participants were free to decline our request to be included in our designated categories and therefore to be interviewed. All of the second-generation participants talked about their connection to the immigrant community and the role their participation played in representing those communities.

5 Within “culture,” we examined “barriers,” “values,” “process,” and “process: meetings”; within “influence,” we examined “barriers,” “learning,” and “staff support.”

6 We posit that these individuals did not know the exact name and instead described RRO’s components.

References

- Adams, B. (2004). Public meetings and the democratic process. Public Administration Review, 64(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00345.x

- American Immigration Council. (2020). Immigrants in Oregon. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/immigrants_in_oregon.pdf

- Antonsich, M. (2022). What’s in a name? Children of migrants, national belonging and the politics of naming. Social & Cultural Geography, 23(8), 1078–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2021.1896026

- Arcury, T. A., & Quandt, S. A. (2011). Living and working safely: Challenges for migrant and seasonal farmworkers. North Carolina Medical Journal, 72(6), 466–470. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.72.6.466

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Avis, W. R. (2016). Urban governance [Topic guide]. University of Birmingham.

- Beard, V. A., & Sarmiento, C. S. (2014). Planning, public participation, and money politics in Santa Ana (CA). Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(2), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2014.953002

- Bickerstaff, K., & Walker, G. (2005). Shared visions, unholy alliances: Power, governance and deliberative processes in local transport planning. Urban Studies, 42(12), 2123–2144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500332098

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Polity Press.

- Briggs, X. (1998). Doing democracy up-close: Culture, power, and communication in community building. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456x9801800101

- Brody, S. D., Godschalk, D. R., & Burby, R. J. (2003). Mandating citizen participation in plan making: Six strategic planning choices. Journal of the American Planning Association, 69(3), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360308978018

- Buse, K., Bernstein, R. S., & Bilimoria, D. (2016). The influence of board diversity, board diversity policies and practices, and board inclusion behaviors on nonprofit governance practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(1), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2352-z

- Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Carpini, M. X., Cook, F. L., & Jacobs, L. R. (2004). Public deliberation, discursive participation, and citizen engagement: A review of the empirical literature. Annual Review of Political Science, 7(1), 315–344. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.121003.091630

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978187

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Fine, G. A. (2012). Tiny publics: A theory of group action and culture. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Fung, A. (2003). Survey article: Recipes for public spheres: Eight institutional design choices and their consequences. Journal of Political Philosophy, 11(3), 338–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00181

- García, I., Garfinkel-Castro, A., & Pfeiffer, D. (2019). Planning with diverse communities. American Planning Association.

- Gastil, J. (2000). By popular demand: Revitalizing representative democracy through deliberative elections. University of California Press.

- Gaventa, J. (2005). Reflections on the uses of the “power cube” approach for analyzing the spaces, places, and dynamics of civil participation and engagement. https://www.participatorymethods.org/sites/participatorymethods.org/files/reflections_on_uses_powercube.pdf

- Goetz, E. G., Williams, R. A., & Damiano, A. (2020). Whiteness and urban planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(2), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1693907

- Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger, Trans.). MIT Press. (Original work published 1962)

- Hafer, J. A., & Ran, B. (2016). Developing a citizen perspective of public participation: Identity construction as citizen motivation to participate. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 38(3), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2016.1202080

- Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2004). Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Planning Theory & Practice, 5(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935042000293170

- Jehn, K. A., & Mannix, E. A. (2001). The dynamic nature of conflict: A longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069453

- Knaap, G. J., Matier, D., & Olshansky, R. (1998). Citizen advisory groups in remedial action planning: Paper tiger or key to success? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 41(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640569811623

- Krumholz, N. (1982). A retrospective view of equity planning: Cleveland 1969–1979. Journal of the American Planning Association, 48(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944368208976535

- Laurian, L., & Shaw, M. M. (2009). Evaluation of public participation: The practices of certified planners. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 28(3), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08326532

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, C. A. (2019). Engaging non-citizens in an age of uncertainty. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1616318

- Lee, E. (1998). Looking through an anti-racist lens. In E. Lee, D. Menkart, & M. Okazawa-Rey (Eds.), Beyond heroes and holidays: A practical guide to K-12 anti-racist, multicultural education and staff development (pp. 402–404). Teaching for Change.

- Lichter, D. T., Parisi, D., & Taquino, M. C. (2018). White integration or segregation? The racial and ethnic transformation of rural and small town America. City & Community, 17(3), 702–719. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12314

- Loh, C. G., & Kim, R. (2021). Are we planning for equity? Equity goals and recommendations in local comprehensive plans. Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1829498

- Maclaren, V., Morris, A., & Labatt, S. (2017). Engaging local communities in environmental protection with competitiveness: Community advisory panels in Canada and the United States. In J. J. Kirton & P. I. Hajnal (Eds.), Sustainability, civil society and international governance (pp. 31–39). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351148283-2

- Mansbridge, J., Hartz-Karp, J., Gastil, J., & Amengual, M. (2006). Norms of deliberation: An inductive study. Journal of Public Deliberation, 2(1), 14–40. https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.35

- Margerum, R. D. (1999). Getting past yes: From capital creation to action. Journal of the American Planning Association, 65(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369908976046

- Margerum, R. D. (2002). Evaluating collaborative planning: Implications from an empirical analysis of growth management. Journal of the American Planning Association, 68(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360208976264

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031

- Meléndez, J. W. (2021). Latino immigrants in civil society: Addressing the double-bind of participation for expansive learning in participatory budgeting. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 30(1), 76–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2020.1807349

- Meléndez, J. W., Hoff, C. G., Rausch, L., Graciosa, M. K., & Renirie, A. (2021). The landscape of civic participation among immigrants: Documenting service on decision-making bodies as a third type of civic engagement activities. In R. Bussel (Ed.), “A state of immigrants”: A new look at the immigrant experience in Oregon. Labor Education Research Center, University of Oregon.

- Meléndez, J. W., & Martinez-Cosio, M. (2019). Designing for equitable civic engagement: Participatory design and discourse in contested spaces. Journal of Civil Society, 15(1), 18–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2018.1559471

- Meléndez, J. W., & Martinez-Cosio, M. (2021). Differentiating participation: Identifying and defining civic capacities used by Latino immigrants in participatory budgeting. City & Community, 20(3), 212–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1535684121993473

- Meléndez, J. W., & Parker, B. (2019). Learning in participatory planning processes: Taking advantage of concepts and theories across disciplines. Planning Theory & Practice, 20(1), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1558748

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Sage Publications.

- Mitchell, J. (1997). Representation in government boards and commissions. Public Administration Review, 57(2), 160–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/977064

- Nishishiba, M. (2012). Local government diversity initiatives in Oregon: An exploratory study. State and Local Government Review, 44(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X12439475

- QSR International. (2020). NVivo (Release 1.0) [Computer software]. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Quick, K. S., & Feldman, M. S. (2011). Distinguishing participation and inclusion. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31(3), 272–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X11410979

- Ramakrishnan, S. K., & Lewis, P. G. (2005). Immigrants and local governance: The view from city hall. Public Policy Institute of California.

- Riccucci, N. M., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2017). Representative bureaucracy: A lever to enhance social equity, coproduction, and democracy. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12649

- Rojas, J. (2014). Latino placemaking: How the civil rights movement reshaped East LA. Project for Public Spaces. https://www.pps.org/article/latino-placemaking-how-the-civil-rights-movement-reshaped-east-la

- Rosen, J., & Painter, G. (2019). From citizen control to co-production. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1618727

- Ryfe, D. M. (2005). Does deliberative democracy work? Annual Review of Political Science, 8(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.8.032904.154633

- Saldaña, J., & Omasta, M. (2017). Qualitative research: Analyzing life. Sage Publications.

- Sanders, W., Getzels, J. (1950). The planning commission—its composition and function (PAS Report 19). American Society of Planning Officials. https://planning-org-uploaded-media.s3.amazonaws.com/legacy_resources/pas/at60/pdf/report19.pdf

- Schneider, J. (2016). First/second generation immigrants (NESET II ad hoc question no. 4/2016). http://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/NESET2_AHQ4.pdf

- Smith, G. (2009). Democratic innovations: Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Solis, M. (2020). Racial equity in planning organizations. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(3), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1742189

- Steil, J. (2022). Antisubordination planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18815739

- Taylor, M., Howard, J., & Lever, J. (2010). Citizen participation and civic activism in comparative perspective. Journal of Civil Society, 6(2), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2010.506377

- Tichenor, D. J. (2021). The politics of immigration in Oregon. In R. Bussel (Ed.), “A state of immigrants”: A new look at the immigrant experience in Oregon (pp. 59–76). Labor Education Research Center, University of Oregon.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2017/5-year.html

- Williams, R. A. (2020). From racial to reparative planning: Confronting the White side of planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20946416

- Young, I. M. (1996). Communication and the other: Beyond deliberative democracy. In S. Benhabib (Ed.), Democracy and difference (pp. 120–136). Princeton University Press.

- Zapata, M. A., & Bates, L. K. (2015). Equity planning revisited. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 245–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15589967