Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

Debates about race in the United States are front and center in the 21st century. From the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement to the caging of indigenous migrant children from Mexico and Central America to rising Asian American and Pacific Islander discrimination during COVID-19, the urgency for an explicit definition of racial equity planning and examples of how the ethic evolved could not be more pressing. Historically, social justice–oriented planners focused efforts on racial equity despite a lack of a collective understanding of the topic. By demonstrating diverse, applied approaches through an analysis of 17 municipal and community-led plans at various scales, we traced the primacy of race in equity planning through four key eras: civil rights, Model Cities and successive programs, HOPE VI and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Sustainable Cities Regional Planning Grants, and contemporary. How and why has racial equity planning evolved in the academic planning literature and representative racial equity plans in the last 60 years? Racial equity planning has always been a cornerstone of the field, and lessons from the literature and relevant plans merit deeper attention, especially as White supremacy gains stronger ground.

Takeaway for practice

Planners should affirm a unified definition of racial equity planning informed by relevant scholarship and operationalize its tenets in their work. Recognizing key milestones where racial equity has successfully informed contemporary urban policies offers progressive planners a rich set of alternative policies, strategies, and programs to use across diverse communities.

The rise of contemporary social movements ranging from Stop Asian American/Pacific Islander Hate to Black Lives Matter (BLM) has influenced cities and state governments grappling with increased racial tensions and income inequality. On the one hand, these social movements are testaments to the pre-existing networks and organizational capacities of the not-for-profit organizations and ad hoc grassroots advocacy groups they are built upon. On the other, increased activist movements illuminate the flaws of race-neutral planning and the central role race must sustain in planning practice.

Increased attention to race highlights the need for a re-emergence of race-specific equity-based planning. However, it is difficult to operationalize racial equity planning goals without a clear definition of racial equity planning. Equity planning and social justice are not new to urban planning (Bates & Green, Citation2018; Davidoff, Citation1965; Fainstein, Citation2010; Krumholz, Citation1986; Reece, Citation2018; Song, Citation2014; Thomas, Citation2012). Progressive planning scholars Friedmann (Citation1993) and Kennedy (Citation1996) described plans as transactive and transformational instead of using the term racial equity planning (REP). Other scholars described variations of insurgency in plans and cities to articulate revolutionary attempts toward racial equity (Holston, Citation2008; Hou, Citation2010; Miraftab, Citation2009; Sandercock, Citation1999; Shrestha & Aranya, Citation2015).

Unfortunately, REP is not part of planning literature’s lexicon, and a failure to lead with race decreases the visibility of anti-racism plans and initiatives within the field. We define REP as planning that aims to ameliorate historically racist policies, programs, and actions through prioritizing public resource redistribution, ethnic and racial representation, and participatory procedural design. For this review, we analyzed REP’s transformation via four planning eras and foci: the civil rights era (1961–1968), with a focus on social justice; the Model Cities and successive programs era (1969–1991), with a focus on citizen participation; the HOPE VI and Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Sustainable Cities Regional Planning Grants era (1992–2015), with a focus on equitable housing; and the contemporary era (2015–2021), with a focus on local-level community stability and grassroots-based partnerships and reparations. We traced the history of REP by asking how and why REP evolved in planning scholarship and municipal and community-approved urban plans. As of this writing, cities have been highly racialized and planners need an understanding of diverse approaches to REP. At a minimum, planning practitioners need exposure to the racist planning history that contributed to segregated cities and must learn about diverse REP approaches.

The updated (as of 2021) AICP Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct (Section A: Principles to Which We Aspire, Part III) emphasizes racial justice as a primary planning goal, stating that “people who participate in the planning process shall work to achieve economic, social and racial equity” (AICP, Citation2005, revised 2021, p. 3). The Code also states planners should “seek social justice by identifying and working to expand choice and opportunity for all persons, emphasizing our special responsibility to plan with those who have been marginalized or disadvantaged and to promote racial and economic equity” (AICP, Citation2005, revised 2021, p. 3). A notable omission, however, is the lack of addressing REP in the enforceable (Part B) section of the AICP Code of Conduct. Planning practitioners, nevertheless, have engaged in racial equity efforts since the civil rights movement (Thomas, Citation2012, Citation2019). Admittedly, planning scholarship often bundles racial equity within a general equity planning framing, an action that perpetuates scant awareness of racial equity and the difficulties planners face in application.

The absence of overt attention to race in the last 60 years has set the stage for daylighting and eventual recentering of race in equity planning. Social movements like BLM have created opportunities for urban planners to re-engage in equitable initiatives for displaced urban African American and Black communities, as well as dispossessed Native American communities. Movements have also exposed the racialization tied to authorized immigration for recent waves of Latino/a/x immigrant communities and new streams of Asian migrants and Asian Americans facing rising bias and discrimination during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (C. A. Lee et al., Citation2021; C. A. Lee & Arroyo, Citation2022; Zapata & Bates, Citation2017). Despite the increased attention to race, planners and planning institutions have struggled with equity’s definition and how to operationalize it (Brand, Citation2015). They also often fail to recognize the major strides equity planning has already made in research and practice.

Our REP definition builds upon the ideas of social justice philosophers Iris Marion Young and Nancy Fraser. I. M. Young (Citation2011) viewed social equity as an institutional effort to address historical forms of oppression. Fraser (Citation1999) argued that social justice is a form of redistribution and recognition. Her redistribution paradigm focused on socioeconomic injustices rooted in the economic structure of society: The remedy for injustice is economic restructuring. Furthermore, Fraser’s recognition paradigm targeted injustices understood as cultural based on social patterns of representation, interpretation, and communication: The remedy for injustice is cultural or symbolic change. For example, anti-discrimination efforts to protect same-sex marriage for the LGBTQIA + community fall within the recognition paradigm. In addition, procedural equity, advanced by urban resilience planning scholars, has added a process dimension to Young and Fraser’s concepts. Meerow et al. (Citation2019) stated:

Equitable participation in decision-making processes includes public participation in the development of the plan, efforts to increase ongoing public participation in city governance, and specific outreach to marginalized groups that often are underrepresented in traditional public engagement processes. [p. 798]

REP encompasses three elements of justice: redistributional, recognitional, and procedural. It leads to more material resources for people of color and increased cultural recognition, and empowers the voices of people of color. Redressing racism in cities, suburbs, and towns becomes the goal of REP, as the process demands a shift from a culture rooted in White supremacy to one that respects and learns from diverse cultural and ethnic differences. At the core of understanding race in the United States is Whiteness, the customs, culture, and beliefs of White people to which all other racial groups are compared (Fields, Citation2001; Goetz et al., Citation2020; Hartigan, Citation1997; A. Keating, Citation1995; Painter, Citation2015). Whiteness inherently normalizes the prominence of White racial identity in the United States and creates an environment that makes non-White individuals inferior (Doane, Citation2013; Garner, Citation2007). Based on our definition of REP and the increasing role of Whiteness, we analyzed racial equity plans to showcase diverse approaches to help racial equity planners implement goals that align with their planning agency’s mission. Advancing REP will ultimately expand the goals outlined in the AICP Code: “economic, social and racial equity” (AICP, 2005, revised 2021, p. 3).

Methods

The basis of our review was a chronological literature review contextualized by a series of plans across four key eras. We identified 17 geographically dispersed plans (see the Technical Appendix for more details) focused on various strategies for addressing racial equity that spanned 60 years (1961–2021). Several plans are well known in the field (e.g., The Cleveland [OH] Policy Planning Report, 1975 [Cleveland City Planning Commission, Citation1975]), whereas others are more recent and novel (e.g., City of Evanston, Citation2021). We limited the study to the known availability of relevant plans or their coverage in scholarly literature. Although some plans featured Latino/a/x, Asian American and Pacific Islander, and Native American groups, most analyzed plans focused on affected African American and Black groups. Additional research is required to investigate whether non–African American and Black groups are becoming integrated into REP.

We employed a four-phase collection strategy to identify and locate formal (sanctioned by planners at public agencies) and community-driven (not-for-profit organization or grassroots advocacy-led civil rights groups, trade unions, and faith-based organizations) plans published during our 60-year time frame. The initial collection phase was inductive and bounded scholarly planning eras with representative plans created concomitantly or catalyzed by major events during that period (e.g., the civil rights movement) or directly referenced in planning scholarship and practice.

The second phase was deductive and identified plans in cities (multiple scales) that matched the eras identified in Phase 1. Leading planning scholars directed the publication of several plans (e.g. Cleveland City Planning Commission [Krumholz, Citation1975; Thabit, Citation1961]), and popular equity-oriented theories influenced or aided others (e.g., Birmingham Black Civic Associations). We derived another batch from reviewing plans from public agencies, community-based organizations, or locales with pre-existing racial equity commitments from previous strategies (plans or programs).

A third phase relied on examining the prevalence of REP as determined by annual national awards given by the American Planning Association Board of Directors, the official professional organization for the field in the United States. We reviewed all award winners of the APA National Planning Excellence Awards over the last decade (since 2012; American Planning Association, Citationn.d.). Plans spanned the United States from Puget Sound (WA) to Birmingham (AL) to New York (NY) and featured housing, transportation, urban design, economic development, and cultural heritage/historic preservation.

Finally, we searched the archives of the Progressive Planning Magazine (known as Planners Network Newsletter before the 2000s), a newsletter reaching equity planners in the United States and Canada (Planners Network, Citationn.d.). Analysis of content in this publication between 1997 and 2016 uncovered details about more radical and rogue forms of equity planning.

We relied on content analysis to analyze the plans while simultaneously developing the literature review to identify the most significant and often lesser-known and undercelebrated racial equity–oriented plans. We thoroughly examined the plans, and we recorded data in terms of year of publication; plan type (e.g., neighborhood plan, urban renewal plan, comprehensive or general plan, redevelopment plan or thematic plan specific to housing, transportation, disaster recovery, or immigrant integration); location (city and region in the United States); funding source; and key partnerships and alliances in the development and execution of the plan (e.g., municipal, interagency, not-for-profit, and community-based organizations). The results were organized in several ways: chronologically by year published, geographically by connection to the broader four areas delineated here, and by associated planning scholars.

We analyzed these data alongside key textual components and descriptions referring to racial equity using Microsoft Excel. We developed a codebook of keyword searches with terms that frame REP (e.g., equity, race, social equity, reparative planning, representative planning, civil rights planning, and advocacy planning). Two coders coded each plan to maintain rigor and measure intercoder reliability. We also reviewed racial and environmental justice literature that highlighted the use of diverse strategies, including lawsuits, legislative initiatives, grassroots activism, community organizing, and development to inform the historical analysis (Archer, Citation2020; Bullard, Citation2001; Crump, Citation2002; Golub, Citation2013; Weintraub, Citation1994; Welton & Freelon, Citation2018).

Racial Equity Planning Literature and Representative Plans: Key Eras (1961–2021)

Our review of the canon of REP literature led to four key eras identified by primary themes ().

Table 1 Racial equity planning: Four key eras.

REP has strong roots in the urban renewal strategies that cleared predominantly African American, Black, and Latino/a/x downtown areas in major urban centers in the mid-20th century. President Lyndon B. Johnson created the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 1965, continuing President John F. Kennedy’s initial vision as part of federal efforts to reduce the national poverty rate (Khadduri, Citation2015). Federal funds that mandated a particular approach through shorter-lived federal initiatives, such as Model Cities, and enduring ones like HUD’s Community Development Block Grant Program, catalyzed REP.

REP was influenced by civil rights era struggles that were ideologically Marxist and anti-capitalist through rent strikes and the formation of planner advocacy and citizen equity groups such as Planners for Equal Opportunity (PEO) in New York City (Thabit, Citation1999). More recently, there has been a heightened awareness of the BLM movement as well as increased visibility of police killings of people of color, resulting in massive civil unrest. This climate promoted demands for racially based housing and local capital reparations, primarily—but not only—for African American and Black communities and recentered REP.

Civil Rights Era: Social Justice (1961–1968)

We identified social justice as the primary theme in the literature review connected to planning during the 1960s. During this time, racial discrimination and its economically and socially disabling consequences became issues of national concern because of the systematic de jure and de facto denial of equal opportunity for African American and Black individuals (Rabin, Citation1970). In 1965, Paul Davidoff proposed a theory of advocacy planning to align the value of equity in planning (Checkoway, Citation1994; Reardon & Forester, Citation2019; Solis, Citation2020; Zapata & Bates, Citation2015). According to Davidoff, the advocacy planner must ensure that citizens become well informed about the motivations for planning proposals and versed in the technical language of professional planners. Although Davidoff’s language is more about advocacy and not equity, this term and ideology created the foundation for equity planning in today’s theory and practice. In this section, we trace the evolution from advocacy to equity.

Advocacy planning gained popularity in professional schools during the 1970s (Klemek, Citation2009), and some planners who pursued social equity and redistribution sought to implement this vision within the local government (Krumholz & Clavel, Citation1994). Norman Krumholz, a former student of Davidoff’s, developed the term equity planning while overseeing the creation of the Cleveland Policy Planning Report (Krumholz & Forester, Citation1990). Krumholz defined equity planning as expanding the range of choices for those who traditionally have had the fewest and who are “less favored by present conditions” (City of Cleveland, Citation1975, p. 10 as cited in Brand, Citation2015, p. 250). Though many ideas were not original or unique to the plan, they diverged significantly from the downtown-oriented land use planning tradition prevalent in most U.S. cities during this time (Keating & Krumholz, Citation1991).

The primary definitions of advocacy (Davidoff, Citation1965) and equity planning (Krumholz et al., Citation1975) did not mention race and thus obscure the historical primacy of race as an equity concern for planners. However, Davidoff, Krumholz, and other planners and scholars were aware of and concerned with issues of race and racism. Reardon and Raciti (Citation2019) commented that “Davidoff’s advocacy planning ideas and methods never achieved dominance” (p. 607) in planning, but they improved living conditions for some marginalized groups and provided a foundation for further centering equity. By 1964, PEO formed as a group of planning, housing, and social work professionals concerned with racial equity in planning, related to housing and federal housing programs and especially race-based rent discrimination (Cornell University Library, Citationn.d.; Thabit, Citation1999).Footnote1 PEO played a prominent role in advancing racial equity and collaborated with the American Institute of Planners (AIP). However, the exclusion of the group’s rhetoric about race and racial discrimination in the advocacy planning or equity planning definitions of the 1960s and 1970s and in some equity planning scholarship (Metzger, Citation1996; Reece, Citation2018) overlooked PEO’s role during this time.

In the 1970s, scholars explored how advocacy flourished in city and government planning and how equity planning emerged. Needleman and Needleman’s (Citation1974) Guerillas in the Bureaucracy: A Community Planning Experiment illustrated how planners assumed positions as administrative guerillas, becoming clandestine advocates within city bureaucracies while preserving their cover as disinterested technical experts (Thomas & Ritzdorf, Citation1997). Needleman and Needleman reinforced the notion that “equity planning developed as a government response to community organizing” (Krumholz & Clavel, Citation1994, p. 11). For Brand (Citation2015), Davidoff’s theory “rejects the concept that planners act as neutral technicians and argues for planners to take up the political and social values embedded in the practice of planning” (p. 250). The critical transformation planning had undergone during and after the civil rights era would echo the goals of federal urban renewal projects and legislation.

Davidoff’s theory of advocacy planning also responded to U.S. cities’ decisions to hire planners to create racial zoning plans before and during the civil rights movement (Silver, Citation1997). As Silver (Citation1997) explained, racial zoning continued to operate while remaining compliant with the law during urban renewal after the landmark Buchanan v. Warley case in 1917. The U.S. Supreme Court declared racially biased zoning unconstitutional through a victory in the Buchanan decision, but it focused only on upholding property rights, not affirming equal protection for individuals of different racial identities under the law (The Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, Citationn.d.). As a result, exclusionary zoning (Bigham & Bostick, Citation1972; Davidoff & Gold, Citation1970a; Whittemore, Citation2017, Citation2021; Wilson, Citation2018) continued in novel forms (Mangin, Citation2014). Scholars have studied the impact of exclusionary zoning in the suburbs (Danielson, Citation1976; Davidoff & Davidoff, Citation1970; Davidoff & Gold, Citation1970b), and Davidoff and Gold (Citation1970a, Citation1970b) worked with Suburban Action to support policy and legal actions to increase equity in the suburbs and support affordable housing. The tenets of Davidoff’s advocacy planning became the first formal attempt to transform the planning profession from an arm of tacit, and even insidious, government intervention that perpetuated a racially bifurcated society to one that combatted and ruptured systematic racism.

RACIAL EQUITY PLANS

Social justice was a key focus of implemented plans during the civil rights era (1961–1968) because this was a time of great tumult and progress in American democracy (). Long-standing legalized racial discrimination, segregation, and wanton barriers for African Americans, Blacks, and other pioneering activists in the Native American, Latino/a/x, and Asian American and Pacific Islander communities spurred a grassroots national movement resulting in direct actions for legislative gains, protections, and resources: a comprehensive new vision for human rights across the country (Morris, Citation1986). These changes led to attempts to rectify racist aspects of planning and urban development primarily evident in housing and civil society through the landmark legacy of the Housing Act of 1949, the Civil Rights Act (1968), and the Fair Housing Act (Titles VIII and IX of the Civil Rights Act).Footnote2

Table 2 Civil rights era literature and relevant racial equity plans (1961–1968).

The goal of the Truman administration’s Housing Act of 1949 was to address the decline of urban housing and counter the rapid development of suburbs by reducing housing costs, raising housing standards, expanding mortgage options, and enabling the clearance of urban slums through an emphasis on new construction (Lang & Sohmer, Citation2000; Martinez, Citation2000; von Hoffman, Citation2000). Lessons learned from 1949 paved the way for how community groups would respond to housing issues during the civil rights era. Two representative plans resulting from grassroots advocacy during the civil rights era include the Alternate Plan for Cooper Square (Angotti, Citation1997, Citation2008; Angotti & Jagu, Citation2007; Thabit, Citation1961) and a series of municipal-level plans that recognized and placed planning decisions in the hands of African American and Black civic associations in Birmingham.

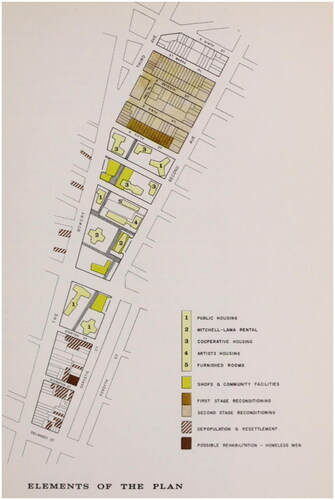

The Alternate Plan for Cooper Square (New York City) was the first known plan that advocated for the anti-displacement of African American, Black, and Latino/a/x tenants and business owners and homeless individuals in the area (Thabit, Citation1961). The plan was developed by Walter Thabit, an activist and member of PEO, and the Cooper Square Community Development Committee and Businessmen’s Association. Thabit (Citation1961) argued that the Cooper Square plan was a response to New York City’s Committee on Slum Clearance’s official—though grossly inaccurate—strategy to displace hundreds of tenants, furnished room occupants, homeless men, and businesses for the construction of middle-income cooperative housing in the Lower East Side.

Angotti and Jagu (Citation2007) highlighted the Cooper Square Plan’s ability to increase community-controlled land via community organization and city support. The plan drew on 100 meetings to propose 10 guiding principles that positioned individuals most affected by displacement as the central beneficiaries of any new development-based investment. According to the plan:

The Cooper Square resident agrees that the area needs renewal, he believes that he should benefit from the improvement, not be the one to suffer from it. If new housing is going to be constructed on the Cooper Square site, he wants one of those apartments for himself. (Thabit, Citation1961, p. 4)

Figure 1. Elements of the 1961 Alternate Plan for Cooper Square including public housing, artist housing, furnished rooms, depopulation and resettlement, and possible rehabilitation of homeless men. Source: Thabit, Citation1961.

Figure 2. Community photos from Cleveland Policy Planning Report in Citation1975. Source: Cleveland City Planning Commission, Citation1975.

At the same time, a series of municipal-level plans that recognized the power of placing planning decisions in the hands of Black civic associations sprouted in Birmingham, a city once dubbed America’s Johannesburg, a loose apartheid reference to the city’s legacy of race-connected practices (Connerly, Citation2005). This was a key strategy after years of planning abuses maintained the racial status quo in America’s most segregated city, including the Supreme Court’s unconstitutional declaration of “the South’s longest-standing racial zoning law” in 1951 (Connerly, Citation2005, p. 3).

Years after the Civil Rights Act of 1968, predominantly Black areas of Birmingham remained excluded from citywide interventions for neighborhood improvement and purposefully segregated. Challenges culminated when advocacy planners worked with hyperlocal African American and Black-led civic leagues and the federal government to formalize a direct relationship with the city’s predominantly White Community Development Department (Connerly, Citation2005). Equity planning examples in Birmingham conform to Krumholz and Clavel’s (Citation1994) understanding of the evolution of equity planning and the community planning profession as a government response to community organizing. Whereas grassroots advocacy informed planning elements of housing and infrastructure before the 1970s, gains during the later period legitimized the role of racial communities within an equity-based planning system.

Both Needleman and Needleman (Citation1974) and Krumholz and Clavel (Citation1994) have argued that advocacy planning presented an opportunity for the potential radical transformation of the planning profession from neutral technician to passionate, or potentially even guerilla, advocate (Needleman & Needleman, Citation1974). In The Alternate Plan for Cooper Square, Thabit (Citation1961) developed one of the first large-scale anti-displacement plans to protect African American, Black, and Latino/a/x tenants and businesses at the heels of the civil rights era. In Birmingham, White advocacy planners recognized the important role African American and Black-led community groups played in dismantling the legacy of residential segregation in the city, a direct result of passing the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Connerly, Citation2005).

Model Cities and Successive Programs Era: Citizen Participation (1969–1991)

Moving into the Model Cities era, citizen participation in planning grew as equity planning advanced on an institutional level between 1967 and 1974. Model Cities provided block grants to cities for social, economic, and physical programs, under the guidance of the newly created HUD. The program funded neighborhood-based agencies, but the government controlled input and participation (Frieden & Kaplan, Citation1975). There were more than 150 5-year Model City projects (Weber & Wallace, Citation2012). Implementation began in 1969, but by this time political goals had shifted from supporting minority political leadership to increasing housing and building projects through citizen participation (Weber & Wallace, Citation2012).

The Model Cities program suffered from a lack of funding and was deemed a failed experiment by studies that focused on the program’s financing (Weber & Wallace, Citation2012). However, it increased African American and Black community activism and civic engagement across the country by encouraging citizen participation (Thomas, Citation1997), despite this not being the program’s main goal (Aleshire, Citation1972; Strange, Citation1972). It also created other tangible benefits, such as improved health care, legal representation, and services for youth and seniors in some cities (Weber & Wallace, Citation2012).

Mittenthal and Spiegel (Citation1970) commented on the value of citizen participation when structured equitably, avoiding top-down government mechanisms. However, this was a challenge for Model Cities. According to Thomas (Citation1997), the program was a “corrective antidote to the oppressive side of urban renewal that was designed to appeal to the urban Black constituency, by encouraging residents to participate in defining and supervising neighborhood improvement…” (p. 144). Thomas has argued that planning must facilitate the fair (re)distribution of public goods and services to marginalized populations. Thomas emphasized the disproportionate amount of social and economic struggles marginalized, impoverished communities of color endure. Weber and Wallace (Citation2012) drew on their nearly 30-year literature review to emphasize the political training, heightened participation, and successful public office elections of minority leaders, particularly in Black communities, that resulted from the program. Many African Americans and Blacks (and some Latino/a/xs) were elected to public office for the first time.

RACIAL EQUITY PLANS

In the next 20 years, wide-sweeping federal programs and policies from HUD (initially Model Cities, followed by Community Development Block Grant Program, Empowerment Zones, the Sustainable Communities Regional Planning Grant [SCRPG], and the Sustainable Cities Initiative [SCI]) generated federal funds that mandated key facets of equity planning, primarily citizen participation (). These mandates influenced three representative plans in Cleveland (1975), New York (1994), and Puget Sound (2013) that incorporated citizen participation.

Table 3 Model cities era literature and relevant racial equity plans (1969–1991).

Under Norman Krumholz’s direction, the Cleveland Planning Department was the first known municipality to center social and racial equity as a key goal in the Cleveland Policy Planning Report (Cleveland City Planning Commission, Citation1975). The plan focused on income and community development and housing and transportation objectives. Like the Alternate Plan for Cooper Square, the Cleveland City Planning Commission (Citation1975) emphasized that “equity requires that locally-responsible government institutions give priority attention to the goal of promoting a wider range of choices for those Cleveland residents who have few, if any, choices” (p. 9). A unique element of the plan was its deference to federal strategies (over local ones) to improve existing housing stock and mobility among non-transit-dependent individuals. According to the plan, “Until an adequate housing allowance program is operational, the Commission supports the reinstatement of Federal programs to subsidize rehabilitation, leasing, and construction of low-income housing” (Cleveland City Planning Commission, Citation1975, p. 16; ).

The plan was an “equity-oriented planning experiment,” implemented across years of diverse political leadership, and focused on redistribution at the neighborhood level (Chakalis et al., Citation2002, p. 88). It did contribute to equitable solutions, but Krumholz (Citation1982) admitted at the time that “it is not surprising that the Cleveland model has little known application by practicing planning professionals” (p. 173), although it highlighted the future potential for this work to grow.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the evolution of REP expanded from local (neighborhood and citywide efforts) to coordinated national efforts. Federal programs and policies from HUD, beginning with Model Cities, aimed to satisfy racial equity mandates (Thomas & Ritzdorf, Citation1997; Weber & Wallace, Citation2012). Krumholz’s Cleveland Policy Planning Report (Cleveland City Planning Commission, Citation1975) guided how to defer to federal strategies for citywide improvement for a racial equity agenda. Later, the Chicago Works Together: Chicago 1984 Development Plan would spotlight the need for increased attention among African American, Black, and Latino/a/x communities through “rigorous goal-setting, measurable targets, and an emphasis on citizen participation” (City of Chicago, Citation1984, p. 21). As momentum to support minoritized racial communities increased, so did scholars intending to prioritize and innovate equity planning initiatives through subsequent programs (Arias et al., Citation2017; Zapata & Bates, Citation2017).

HOPE VI and HUD’s SCRPG Era: Equitable Housing (1992–2015)

Following the defunding of the Model Cities program in the 1970s, HOPE VI and the SCRPG started in 1992 with a focus on fair housing. Funding from HUD, in response to the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Fair Housing Act), Housing and Urban Redevelopment Act of 1970, and Housing and Urban–Rural Recovery Act of 1983, resulted in programs that focused on housing improvements during this time.Footnote3 HUD chartered HOPE VI in 1991 (with formal recognition in 1998) because of recommendations by the National Commission on Severely Distressed Public Housing’s National Action Plan to eradicate severely distressed public housing across the United States (Moschetti, Citation2003).

The goal of these pre-1990s policies was to deconcentrate poverty and racial segregation with mixed-income housing projects and market-rate single-family homes (Popkin, Citation2004; Smith et al., Citation2002). Government-subsidized housing developments were linked to community resources, such as community youth centers, parks, and outreach locations of public services agencies. At times, empowerment zones buoyed HOPE VI investments in areas of high poverty and unemployment given the program’s promise for urban and racial justice (Thomas, Citation1997).Footnote4

Although HOPE VI intended to increase fair housing and improve lives, program implementation failed across the board (Cisneros et al., Citation2009; Popkin, Citation2004; Popkin et al., Citation2004). Vale et al. (Citation2018) described the misaligned accountability mechanisms, prioritizing goals of political officials versus the community, and defined HUD’s practices as “selective memory planning” as planners disregarded original program plans to implement more feasible ones. The program displaced community residents and destroyed older stock housing to build new mixed-income communities. The impacts of relocation and the resulting gentrification have been explored by several scholars (Bennett, Citation2009; Clampet-Lundquist, Citation2004; Goetz, Citation2010, Citation2013; Kleit, Citation2005; Kleit & Manzo, Citation2006; Smith et al., Citation2002; Steil et al., Citation2021; Wyly & Hammel, Citation1999). Fraser et al. (Citation2013) described HOPE VI as “a colonial project” (p. 525) given the displacement of public housing residents and the growing body of research that has shown mixed-income housing can marginalize lower-income residents (Gebhardt, Citation2009; Joseph et al., Citation2007; Schwartz & Tajbakhsh, Citation1997).

However, there have been calls for increased inclusion, equity, and accountability in the revisioning of mixed-income communities (Jackson, Citation2020; Khare & Joseph, Citation2020). The legacy of HOPE VI gave way to the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative in 2010 and the Rental Assistance Demonstration in 2012 as new strategies to improve public housing through tenant relocation with additional services and new access to reinvest in public housing with stricter tenant protections, respectively (Bulger et al., Citation2021; Popkin et al., Citation2020).

Launched in 2010, the SCRPG program encouraged equity-oriented planning at the regional and municipal levels. Federal funding also extended to planning scholars (Arias et al., Citation2017; Bates and Zapata, Citation2013; Frick et al., Citation2015; Zapata & Bates, Citation2017) to examine equity planning within the program. According to an external evaluation by Wilder Research, “The grant explicitly charged the recipients to include the meaningful engagement of historically underrepresented communities as one of the strategies toward this goal of change in the public planning process” (Steel et al., Citation2014, p. 2).

The implementation and reporting from SCRPG-funded regions reoriented planning scholars to the reemergence of REP that had not occurred substantially since Krumholz (Citation1986; Krumholz et al., Citation1975). Bates and Zapata (Citation2013) and Zapata and Bates (Citation2017) found that most regions applying for SCRPG did not use Krumholz’s (Citation1986) equity planning language or goal setting. Krumholz et al. (Citation1975) defined equity as “providing a wider range of alternatives and opportunities while leaving individuals free to define their own needs and priorities” (p. 299). HUD’s definition of equity (in the context of the SCI) was “fair and equal access to livelihood, education and resources, full participation in the political and cultural life of the community, and self-determination in meeting fundamental needs” (HUD, Citationn.d., p. 13).

Arias et al. (Citation2017) complemented the conclusions of Zapata and Bates (Citation2017) and found that three different SCRPG receiving regions (Puget Sound [WA], the Bay Area [CA], and the Twin Cities [MN]) struggled to arrive at a shared understanding of equity. In the Bay Area, planners did not arrive at a shared definition of equity that included race, in contrast to the other two regions. As a result, conversations about residential displacement and low-wage work exposed a critical weakness that did not explicitly address race. Similarly, Brand (Citation2015) found inconsistencies in equity interpretations in planning recovery efforts in post–Hurricane Katrina New Orleans (LA).Footnote5

The discrepancies that Brand (Citation2015) identified were based on different political and social ideologies about urban revitalization and disaster recovery. Two definitions of equity emerged among residents of the Lower Ninth Ward, an understanding rooted in Krumholz’s focus on redistribution of resources, and a newer, neoliberal definition. For Brand (Citation2015), in neoliberalism, individuals “whose developmental and economic interests align with core neoliberal tenets…rationalize their support of various distributional decisions” regardless of the actual impact, sometimes detrimental, on disadvantaged groups (p. 252). In essence, post-Katrina planning “highlighted the tensions of advocacy planning to promote equity within a neoliberal state” (Brand, Citation2015, p. 254). This was in notable contrast to community-led efforts based on direct community feedback, such as The Peoples Plan for Overcoming the Hurricane Katrina Blues: A Comprehensive Strategy for Building a More Vibrant, Sustainable, and Equitable 9th Ward. According to the plan, survey results indicated that residents “placed a high priority on the need for schools, medical facilities, public transportation, community and recreational facilities, parks and playgrounds, affordable housing and grocery stores” (ACORN Housing/University Consortium, Citation2007, p. 5).

RACIAL EQUITY PLANS

Our analysis of representative racial equity plans during this time revealed community efforts to ensure equitable housing for marginalized populations (). The Nos Quedamos Aquí Plan for Melrose Commons (The Bronx, NY) followed the legacy of the Cooper Square and Cleveland plans to oppose the Bronx Center project and secure benefits for the most vulnerable residents in the area (Stand et al., Citation1996). Working with Magnusson Architects, New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, and the Environmental Defense Fund, Yolanda Garcia, founder and inaugural executive director of We Stay/Nos Quedamos, Inc., led an anti-displacement plan geared toward racial equity. The plan valued community needs over corporate or government interests and delineated recommendations for tenants and home and business owners. We Stay/Nos Quedamos Aquí stated:

Table 4 HOPE VI and HUD’s sustainable cities regional planning grant program (1992–2015).

The Urban Renewal Plan removed us from prosperity and made way for new residents who would reap the rewards of our sacrifices. The idea that prosperity meant our community residents had to be sacrificed was inconceivable. We had to be a part of the prosperity. [Stand et al., Citation1996, para.10]

In 2011, the City of Dayton (Human Relations Council) launched Welcome Dayton—Immigrant Friendly City, a citywide initiative to support the livelihood and prosperity of immigrants, refugees, asylee residents, and businesses. The resolution was the product of a coalition of local organizations that worked with city agencies for 6 years on topics ranging from economic development to housing (Homeless Solutions, Citation2006). A key goal from Welcome Dayton recommended that language interpreter access would lead to increased immigrant participation, trust, and communication between government and law enforcement (City of Dayton, Citation2011). The plan is a successful model for regional and national support to bridge newcomers and extant populations and a cornerstone of Welcoming America’s Welcoming Cities Network.

Later, national efforts funded plans such as the Growing Transit Communities plan for Puget Sound, which centered its racial equity framework around HUD’s Partnership for Sustainable Communities Livability Principles (Puget Sound Regional Council, Citation2013). Funded by the SCRPG, the plan addressed the six required livability principles, including “Principle 2: Promote equitable, affordable housing. Expand location- and energy-efficient housing choices for people of all ages, incomes, races, and ethnicities to increase mobility and lower the combined cost of housing and transportation” (Puget Sound Regional Council, Citation2013, p. 5).Footnote6 The result led to the establishment of the Regional Fair Housing Group, which broadened the enforcement of federal racial equity mandates at a regional level.

The rise and continued emphasis of racial advocacy planning from the 1990s and throughout the early 2000s institutionalized the value of progressive community organizing to support housing provision within federal and local planning agencies. Programs such as HOPE VI, SCRPG, and the SCI found value in a regional public housing approach to catalyze reciprocal involvement in racial equity from the onset of major infrastructural change. Building a bridge between advocacy and community planning—in what Krumholz and Clavel (Citation1994) described as radical community planning—enhanced these new federal programs.

Contemporary Era: Local-Level Community Stability and Grassroots-Based Partnerships (2015–2021)

The literature on contemporary (2015–2021) REP and policy debates has focused on local-level community and grassroots-based partnerships. These partnerships are based on increasing community stability and preventing or slowing the gentrification of racially and ethnically mixed neighborhoods (Anguelovski et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Bates, Citation2013, Citation2018; Chapple & Zuk, Citation2016; Freeman, Citation2005, Citation2011; Freeman & Braconi, Citation2004; Lees, Citation2000; Pearsall & Anguelovski, Citation2016; Redfern, Citation2003; Zuk et al., Citation2018). Some literature has also highlighted partnerships and coalitions that are implementing reparations for African Americans, Blacks, and others (Goetz et al., Citation2020; Williams, Citation2020).

Gentrification studies provide insight into opportunities to create more equitable communities. More recently, REP scholarship on displacement and dispossession has considered the legacy of consequences that affect the present day in the same way PEO showed advocacy planning was and is mainly concerned with racial justice and federal programs that engender civic leadership among racialized groups.

Chapple and Zuk (Citation2016) suggested that cities can use patterns of gentrification from the 1980s and previously identified indicators to predict changes and create more equitable change in the future. Freeman and Braconi (Citation2004) studied gentrification in New York City in the 1990s and found that rather than rapid displacement, gentrification was associated with slower residential turnover among lower income households. Bates (Citation2018) examined gentrification and displacement in Albina, North Portland’s (OR) historically African American and Black community. According to Bates, focusing on gentrification and planning for housing affordability is “a moment of opportunity for planners to genuinely address an equity challenge with the traditional tools of planning policy” (Bates, Citation2018, p. 29). Redfern (Citation2003) focused on class distinctions that drive gentrification, whereas Lees (Citation2000) encouraged broadening the analyses of gentrification to the global city, urban policy, and African American, Black, and ethnic minority gentrification.

Racial reparations for African Americans and Blacks in the United States (Chapman, Citation2022; Coates, Citation2015) as well as Native Americans, Asian Americans, and other people of color have been emerging in the literature as well (Chapman, Citation2022). Reparations is a system of redress for egregious injustices. For example, some Native Americans who were forcibly exiled from their land received reparations in the form of returned land and funds (Ray & Perry, Citation2020). Japanese Americans interned during World War II received $1.5 billion in reparations, and the Marshall Plan offered Jews reparations for the Holocaust (Ray & Perry, Citation2020). Despite these examples, the United States has missed opportunities to expand reparations for all affected groups.

Recent scholarship has focused on opportunities to support African American and Black communities with reparations to atone for slavery during the Civil War, Reconstruction, and later during the Black freedom struggle of the 20th century (Burton, Citation2021; Chapman, Citation2022). As of 2021, several cities in the United States included reparations in community planning. For example, a reparations pilot program for African Americans and Blacks in St. Paul (MN) established via the St. Paul Recovery Act has been taking shape (Kiene, Citation2021). Evanston and Asheville (NC) have been raising funds to pay reparations to African Americans and Blacks and invest in minority home- and business ownership, as well as health care, education, and criminal justice system reform (Chapman, Citation2022). In Evanston, “The Restorative Housing Program (‘The Program’), the first program of the Evanston Local Reparations Fund, acknowledges the harm caused to Black/African-American Evanston residents due to discriminatory housing policies and practices and inaction on the City’s part” (City of Evanston, Citation2021, p. 3).

Reparation-based planning gained traction as racial equity planners advocated for making amends for planning’s historical sins by explicitly highlighting Whiteness as a tool of oppression (Goetz et al., Citation2020; Williams, Citation2020). Williams (Citation2020) argued that reparative planning centers corrective/reparative/transitional justice: “The rejection and dismantling of White supremacy such that life chances become independent of one’s ascribed social location” (p. 8). Further, Williams drew on Coleman (Citation1983) and Thompson (Citation2002) to explain that reparative planning, like reparative justice, concerns itself with “the annulment of both wrongful gains and losses,” including “distribution of holdings (or entitlements)” (Coleman, Citation1983, p. 6), and with “what ought to be done in reparation for injustice and the obligation of wrongdoers, or their descendants or successors, for making this repair” (Thompson, Citation2002, p. xi). Williams’s use of “distribution” tenets is consistent with both Krumholz et al. (Citation1975) and Thomas and Ritzdorf’s (Citation1997) definitions of equity planning.

For Goetz et al. (Citation2020), planning would benefit from examining the role of Whiteness and White supremacy in “shaping and perpetuating regional and racial injustices in the American city” (p. 142). Goetz et al. proved how the “focus of planners, scholars, and public discourse on the ‘dysfunctions’ of communities of color, notably poverty, high levels of segregation, and isolation, diverts attention from the structural systems” of White supremacy and racial capitalism that “produce and reproduce the advantages of affluent and White neighborhoods” (Goetz et al., Citation2020, p. 142).

Reparational planning, however, is also inadvertently positioned in a White–Black racial binary and a domestic U.S. context that does not account for the potential reparative status of Native American and other communities of color. Among Asian scholars, REP has sought to combat racial stereotypes and the xenophobia of Asians in the United States that stemmed from the Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese American incarceration during World War II, and other exclusionary federal policies (C. A. Lee et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; E. Lee, Citation2002, Citation2019, Citation2020; Loh, Citation2021). Indigenous planning has elevated issues such as sovereignty, land dispossession, and communal forms of public engagement, which also transcend the traditional White–Black binary and require closer attention in planning (Dalla Costa, Citation2020; Dorries & Harjo, Citation2020; Hibbard, Citation2022; Jojola, Citation1998, Citation2008; Jolly & Thompson-Fawcett, Citation2021; Kumasaka et al., Citation2022; Lane & Hibbard, Citation2005).

Contemporary Latino/a/x immigration scholars such as Arroyo (Citation2021), García (Citation2018), Huerta (Citation2013, Citation2019), Sarmiento and Sims (Citation2015), Sims & Sarmiento (Citation2019), Sandoval (Citation2017, Citation2021), and Irazábal (Citation2021) have contributed to debates on immigrant integration and unauthorized immigrants. Garcia-Hallett et al. (Citation2020) examined REP through the lens of increasing police and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement surveillance in Latino/a/x ethnic enclaves in Kansas City (MO). Latino/a/x scholars have also illuminated the role ethnic identity plays in resisting gentrification, including in transit-oriented projects in California (Sandoval, Citation2017) and the equitable provision of and federal investment in affordable housing without substantive community participation (Sarmiento & Sims, Citation2015).

RACIAL EQUITY PLANS

Racial equity plans during the contemporary era included those proposed, funded, and led by not-for-profit organizations and ad hoc grassroots organizations and have started to include plans that are implementing reparations for some communities (). This was a new direction for advocacy groups to develop substitute or alternative plans as formal, community-led responses to official plans created by public institutions. These plans are emblematic of neighborhood, citywide, or regional planning issues often missing from the respective city’s general or comprehensive plan.

Table 5 Contemporary planning and relevant racial equity plans (2015–2021).

Local-level community stability and grassroots-based partnerships

The Owe'neh Bupingeh Preservation Plan (New Mexico) was the first plan developed to ensure the self-determination of a tribal community in the United States (Atkin Olshin Schade Architects, Citation2010; Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative, Citation2013). The Ohkay Owingeh (“Place of the Strong People”) is one of 19 federally recognized pueblos in New Mexico whose spiritual center (Owe’neh Bupingeh) generated a tribal-led process guided by the tribe’s cultural values. Although most of the tribe’s ceremonial village is intact, changing residential and work patterns—as well as a 1970 plan from HUD to build new homes on the periphery of the town center—led to a decline in building maintenance and preservation, especially among traditional housing stock (HUD Office of Policy Development and Research, Citation2013).

Thirty-five years later, the Ohkay Owingeh Housing Authority and Tribal Council developed a plan to improve housing in a culturally sensitive manner. Local preservationists worked with tribal youth on a twofold mission: 1) to use geographic information systems to document and inventory existing buildings and 2) to employ tribal elders to teach traditional cultural heritage techniques to youth (Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative, Citation2013). The locations of 90 original dwellings were documented and 60 were prioritized for restoration (HUD Office of Policy Development and Research, Citation2013). The Cha Piyeh, a community development financial institution, helped earn the plan a 2013 APA National Planning Excellence Award (American Planning Association Opportunity and Empowerment, Citation2013). Ohkay Owingeh’s Plan was a departure from typical plans because

The rehabilitation principles that evolved are sometimes in conflict with federal preservation standards. However, these principles are based on Ohkay Owingeh community and cultural values and are being implemented by construction crew members and homeowners from the tribe who, through learning traditional methods of construction, ensure that the project is culturally appropriate. [Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative, Citation2013, p. 2]

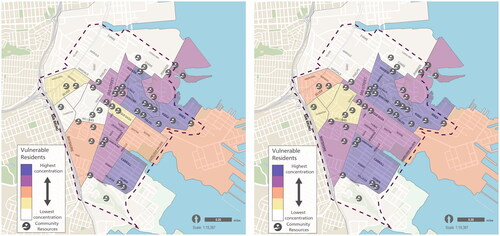

Prioritizing a grassroots model as well, the 2020 Bayview Community Based Transportation Plan (San Francisco [CA]), recipient of the 2021 National APA Award for Advancing Diversity & Social Change, identified transportation barriers faced by one of San Francisco’s longtime African American, Asian American, low-income, and immigrant neighborhoods: Bayview–Hunters Point (San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency [SFMTA], Citation2020a). The 2-year open-ended planning process allowed the SFMTA to partner with nearly 4,000 residents and multiple community groups in southeastern San Francisco. The goal was to achieve “a more collaborative and responsive relationship with the residents of Bayview–Hunters Point” (SFMTA, Citation2020a, p. 7). At more than 56 meetings planners heard concerns ranging from “No more studies!” to “I may be displaced before I can benefit from your plan” (SFMTA, Citation2020b, p. 8).

Figure 3. Project-defined equity index map (left) and community-defined equity index map (right) from 2020 Bayview Community Based Transportation Plan. Source: SFMTA, Citation2020a.

More than $3.63 million was committed to projects to address the needs and desires of residents, with an additional $600,000 grant to allocate via participatory budgeting through the Bayview CBTP Community Steering Committee, a 12-person group of representatives from multiple racial and ethnic-oriented organizations (SFMTA, Citation2020a). Desired projects included crosswalk improvements, bus shelters, youth programs, and funding for new transit assistants. A novel element of the plan was a geographic information system–based equity index tool to identify transit challenges faced by the most vulnerable residents (SFMTA, Citation2020a). SFMTA engaged community leaders, elders, and key organizations to identify the groups facing the greatest transportation challenges through a “recalibrated scoring of data, leading to a new Equity Index Map” (SFMTA, Citation2020a, p. 53; ).

Demand for racially based reparation

BLM’s call to center Black lives in the reparative urban planning field has only increased due to the high-profile police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. In 2018, Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives (PCRI) developed the Pathway 1000 Implementation Housing Plan to raise and invest $300 million over 10 years to construct 1,000 rental and owned homes in the predominantly African American and Black communities of north and northeast Portland and to develop small, independent businesses and create jobs in areas with a history of displacement (PCRI, Citation2018). The plan is an attempt to remedy the residential displacement caused by gentrification in the region in the past 20 years. There is a unique focus on rectifying previous harm and displacement of the city’s African American and Black populations through funding that is not reliant on public support (Berger et al., Citation2016). According to Maxine Fitzpatrick, executive director of PCRI, “We cannot undo the harms done, but rather must focus on restoring housing justice for those who were harmed” (PCRI, Citation2018, p. 6).

Three years later, the City of Evanston drafted the Reparational Restorative Housing Program (City of Evanston, Citation2021). Though not necessarily a plan, the program focused on African American and Black Evanston residents or their ancestors harmed by housing discrimination from 1919 to 1969. The plan offered “restorative housing payments” that can be “layered with other City or externally funded programs,” including Community Development Block Grant housing rehabilitation and other improvements, down payment and closing costs for home purchase (Illinois Housing Development Authority), or mortgage assistance (City of Evanston, Citation2021, p. 8). Recently, the City of Evanston’s Reparations Committee approved 122 applicants qualifying as “ancestors” for the City’s Local Reparations Restorative Housing Program (City of Evanston, Citation2022). They selected 16 for a maximum amount of $25,000 (out of a $400,000 allocation; City of Evanston, Citation2022).

In New Mexico, the Ohkay Owingeh tribe sustained their grassroots and intergenerational leadership to protect their ceremonial village while simultaneously addressing the acute housing needs of current and future generations (Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative, Citation2013). PCRI’s Portland Pathway 1000 (Citation2018) and the City of Evanston’s Reparational Restorative Housing Program (Citation2021) focused on a hyperlocal implementation of reparations. The last 60 years have proved planning has been more in tune with the zeitgeist purchase of racial equity than is commonly known or credited.

Maintaining Planning's Relevance in a Race-Forward Field

Racial equity has been a central—albeit implicit—element of advocacy and equity planning since the mid-1960s. Though there are mentions of reparations planning and racial planning, there is no explicit reference to REP in the field’s canon. Rather, concerns and orientations about racial justice, civil rights, gentrification and displacement, redistributionist policies, and reparations fall under a broader equity planning discourse.

The failure to frame equity planning through race further contributes to White supremacy, Whiteness, and the invisibility of people of color. Because planning practitioners are educated with influential equity planning writings, the lack of centering REP within that body of scholarly work serves as a form of erasure that perpetuates White supremacy in the field. Advocacy and equity planning have always been about REP at their core, even if this was not fully realized and directly articulated and defined as such.

In this review, we have presented an evolution of REP that amends past racist policies and plans via procedural struggles over redistribution and recognition. Our analysis of this evolution supports the notion that REP is a participatory process that leads to the redivision of material resources, recognition of diverse cultures, and empowerment of racialized groups. Our goal of contextualizing the evolution of racial equity in the last 60 years revealed thematic trends, debates, and underappreciated and/or misunderstood contributions in planning scholarship and practice.

We demonstrated diverse approaches to racial equity in planning scholarship in four eras: civil rights era, Model Cities era, HOPE VI and the SCRPG era, and a contemporary era. We illustrated how REP manifested through iterations in equity planning, and we highlighted examples of specific plans that can help planners better understand how to incorporate REP into plans. For example, planners working on racial housing inequality can study the 1961 Alternative Plan for Cooper Square or the 1994 Nos Quedamos Aquí Plan for Melrose Commons. These plans provide planning practitioners with specific initiatives, strategies, and programs relevant to racial equity housing struggles in the 21st century.

Though Davidoff’s (Citation1965) scholarly work on advocacy planning endures, its generalist approach bypassed an explicit focus on race. The scholarly foundations of advocacy planning set the stage for a deeper commitment to the community and the policies that affect them. Planning scholars have often associated with radical community-based strategies, and their relevancy is inextricably tied to the grassroots advocates that founded and supported equitable movements for change across the country (Alinsky, Citation1971). However, credit is seldom given to the weight that race played in groups like the PEO and the bonds that formed across ethnic and racial communities during the 1960s and endure to the present day.

Planners are not new to racial equity work, nor are we behind other professional and scholarly fields. However, contemporary planning overall remains reticent to engage directly with race, thus making the profession ill prepared for one of the most significant barriers to a just future. To move forward, the planning profession must look backward at its past to acknowledge its long-standing contributions to racial equity. Future anti-racist planning strategies may come from what we have already gleaned through previous answers and efforts.

Research Support

This research was supported by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (Just Futures Initiative) grant to the University of Oregon (2021) for the Pacific Northwest Just Futures Institute for Racial and Climate Justice.

Technical Appendix

Download PDF (142.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Iliana Lang Lundgren, a graduate of the Master of Nonprofit Management Program at the University of Oregon and a research assistant for the Pacific Northwest Just Futures Institute for Racial and Climate Justice, for supporting the final editorial phases of the article. We thank Katrina Maggiulli, a doctoral candidate in Environmental Sciences, Studies, and Policy and English at the University of Oregon and a research assistant for the Pacific Northwest Just Futures Institute for Racial and Climate Justice, for copyediting support. We also thank Alayne Switzer for administrative grant support of the University of Oregon’s Just Futures Initiative grant.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2132986.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John C. Arroyo

JOHN C. ARROYO ([email protected]) is an assistant professor in the School of Planning, Public Policy and Management at the University of Oregon.

Gerard F. Sandoval

GERARD F. SANDOVAL ([email protected]) is a professor in the School of Planning, Public Policy and Management at the University of Oregon.

Joanna Bernstein

JOANNA BERNSTEIN ([email protected]) completed doctoral coursework in planning and public affairs at the University of Oregon.

Notes

1 PEO was formed during a spring 1964 Metropolitan Committee on Planning Meeting about rent strikes from African Americans, Blacks, and Puerto Ricans on the Lower East Side and Harlem. The group originally began as City Planners for Civil Rights and then changed to PEO during their formal launch later that summer at the AIP convention in Newark (NJ). The group was the precursor to the Planner’s Network.

2 The Fair Housing Act of the Civil Rights Act was vehemently opposed by senators and the National Association of Real Estate Boards. The passage of a previous iteration of the Civil Rights Act (1966) failed due to the fair housing elements featured in the bill.

3 The Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Fair Housing Act) built on its predecessor (the Civil Rights Act of 1964) to allow federal enforcement of housing discrimination concerning the sale, financing, and rental of housing based on protected classes (race, religion, and national origin). “Sex” was added in a 1974 amendment. The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1970 (commonly known as the New Communities Assistance Program) established financing mechanisms to both public and private developers and expanded the definition of blight to other inappropriately used land uses. The act built on its predecessor (Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968), which was the result of major race-related riots after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The Housing and Urban–Rural Recovery Act of 1983 amended the previous Housing and Community Act of 1974 with major provisions to HUD’s Community Development Block Grant program, which supports infrastructure, economic development, public facilities construction and maintenance, community centers, housing rehabilitation, homeowner assistance, and other local-level commitments.

4 An empowerment zone is an economically distressed area in the United States eligible to receive tax incentives, bonds, and grants from the U.S. federal government, based on the provisions of the Empowerment Zones and Enterprise Communities Act of 1993.

5 Even though New Orleans was not an SCI- or SCRPG-funded region, REP for the area occurred while SCI and SCRPG gained momentum in other places.

6 The six Federal Partnership for Sustainable Communities Livability Principles are 1) provide more transportation choices; 2) promote equitable, affordable housing; 3) enhance economic competitiveness; 4) support existing communities; 5) coordinate policies and leverage investment; and 6) value communities and neighborhoods.

References

- ACORN Housing/University Consortium. (2007). The peoples plan for overcoming the Hurricane Katrina blues: A comprehensive strategy for building a more vibrant, sustainable, and equitable 9th Ward. Cornell University, Department of City and Regional Planning.

- Aleshire, R. A. (1972). Power to the people: An assessment of the community action and model cities experience. Public Administration Review, 32, 428–443. https://doi.org/10.2307/975013

- Alinsky, S. (1971). Rules for radicals: A pragmatic primer. Random House.

- American Institute of Certified Planners. (2005, revised 2021)). AICP code of ethics and professional conduct. https://www.planning.org/ethics/ethicscode/

- American Planning Association. (n.d). Award recipients: National planning excellence awards. https://www.planning.org/awards/recipients/

- American Planning Association Opportunity and Empowerment. (2013). HUD’s secretary opportunity & empowerment award: Owe’neh Bupingeh preservation plan. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/about/OppEmpowerAward_2013_1.html

- Angotti, T. (1997). New York City’s “197-a” community planning experience: Power to the people or less work for planners? Planning Practice & Research, 12(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459716716

- Angotti, T. (2008). New York for sale: Community planning confronts global real estate. MIT Press.

- Angotti, T., & Jagu, C. (2007). Community land trusts and low-income multifamily rental housing: The case of Cooper Square, New York City. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J., Masip, L., & Pearsall, H. (2018). Assessing green gentrification in historically disenfranchised neighborhoods: A longitudinal and spatial analysis of Barcelona. Urban Geography, 39(3), 458–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1349987

- Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J. T., Pearsall, H., Shokry, G., Checker, M., Maantay, J., Gould, K., Lewis, T., Maroko, A., & Roberts, J. T. (2019). Opinion: Why green “climate gentrification” threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(52), 26139–26143. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920490117

- Archer, D. N. (2020). White men’s roads through Black men’s homes”: Advancing racial equity through highway reconstruction. Vanderbilt Law Review, 73(5), 1259–1330. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol73/iss5/1

- Arias, J. S., Draper-Zivetz, S., & Martin, A. (2017). The impacts of the sustainable communities initiative regional planning grants on planning and equity in three metropolitan regions. Cityscape, 19(3), 93–114.

- Arroyo, J. (2021). Facades of fear: Anti-immigrant housing ordinances and Mexican rental housing preference in the suburban new Latinx South. Cityscape, 23(2), 181–206. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27039957

- Atkin Olshin Schade Architects. (2010). Owe’neh Bupingeh preservation project. https://www.aosarchitects.com/case-study/oweneh-bupingeh-preservation-project

- Bates, L. K. (2013). Gentrification and displacement study: Implementing an equitable inclusive development strategy in the context of gentrification. Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. https://doi.org/10.15760/report-01

- Bates, L. K. (2018). 1. Growth without displacement: A test for equity planning in Portland. In N. Krumholz & K. W. Hexter (Eds.), Advancing equity planning now (pp. 21–43). Cornell University Press.

- Bates, L. K., & Green, R. A. (2018). Housing recovery in the Ninth Ward: Disparities in policy, process, and prospects. In R. D. Bullard & B. Wright (Eds.), Race, place, and environmental justice after Hurricane Katrina (pp. 229–245). Routledge.

- Bates, L. K., & Zapata, M. (2013). Revisiting equity: The HUD sustainable communities initiative. Progressive Planning. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1083&context=usp_fac

- Bennett, S. (2009). Constructing the social impact statement to measure the full cost to public housing tenants of urban renewal. In N. M. Davidson & R. P. Malloy (Eds.), Affordable housing and public-private partnerships (pp. 129–168). Routledge.

- Berger, K., Dearman, A., Gilden, B., Guillén-Chapman, K., & Rucker, J. (2016). Pathway 1000 community housing plan. http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_murp/133

- Bigham, W. H., & Bostick, C. D. (1972). Exclusionary zoning practices: An examination of the current controversy. Vanderbilt Law Review, 25, 1111. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol25/iss6/1

- Brand, A. L. (2015). The politics of defining and building equity in the twenty-first century. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15585001

- Building Bridges Across the River. (2015). 11th Street Bridge Park’s equitable development plan. https://bbardc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Equitable-Development-Plan_09.04.18.pdf

- Bulger, M., Joseph, M., McKinney, S., & Bilimoria, D. (2021). Social inclusion through mixed-income development: Design and practice in the choice neighborhoods initiative. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1898283/

- Bullard, R. D. (2001). Environmental justice in the 21st century: Race still matters. Phylon, 49(3/4), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/3132626

- Burton, E. M. (2021). Tulsa wealth disparity: The political legacy of the 1921 race massacre. Political Science Honors Projects, 91. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/poli_honors/91

- Chakalis, A., Keating, D., Krumholz, N., & Wieland, A. M. (2002). A century of planning in Cleveland. Journal of Planning History, 1(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/153851320200100105

- Chapman, A. R. (2022). Rethinking the issue of reparations for Black Americans. Bioethics, 36(3), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12954

- Chapple, K., & Zuk, M. (2016). Forewarned: The use of neighborhood early warning systems for gentrification and displacement. Cityscape, 18(3), 109–130. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26328275

- Checkoway, B. (1994). Paul Davidoff and advocacy planning in retrospect. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(2), 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369408975562

- Cisneros, H. G., Engdahl, L., & Schmoke, K. L. (2009). From despair to hope: HOPE VI and the new promise of public housing in America’s cities. Brookings Institution Press.

- City of Chicago. (1984). “Chicago works together”:1984 Chicago development plan. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/40517/CWT-1984.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- City of Dayton. (2011). Welcome Dayton plan: Immigrant friendly city. http://www.welcomedayton.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Welcome-Dayton-immigrant-friendly-report-final.pdf

- City of Evanston. (2021). Local reparations: Restorative housing program. Official program guidelines. https://www.cityofevanston.org/home/showpublisheddocument/66184/637677439011570000

- City of Evanston. (2022). Evanston local reparations. https://www.cityofevanston.org/government/city-council/reparations

- Clampet‐Lundquist, S. (2004). HOPE VI relocation: Moving to new neighborhoods and building new ties. Housing Policy Debate, 15(2), 415–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2004.9521507

- Cleveland City Planning Commission. (1975). Cleveland policy planning report. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/40857

- Coates, T. N. (2015). The case for reparations. Columbia University Press.

- Coleman, J. L. (1983). Moral theories of torts: Their scope and limits, part II. Law and Philosophy, 2(1), 5–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00145311

- Connerly, C. E. (2005). The most segregated city in America”: City planning and civil rights in Birmingham, 1920-1980. University of Virginia Press.

- Cornell University Library. (n.d). Planners for equal opportunities records, 1964–1978. Collection Number 3943. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections. https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/RMM03943.html

- Crump, J. (2002). Deconcentration by demolition: Public housing, poverty, and urban policy. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 20(5), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1068/d306

- Dalla Costa, W. (2020). Indigenous futurity and architecture: Rewriting the urban narrative. Architecture Australia, 109(2), 56–58. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.987497282121750

- Danielson, M. N. (1976). The politics of exclusionary zoning in suburbia. Political Science Quarterly, 91(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/2149156

- Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978187

- Davidoff, P., & Davidoff, L. (1970). Opening the suburbs: Toward inclusionary land use controls. Syracuse Law Review, 22, 509. https://pauldavidoff.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Opening_the_Suburbs.pdf

- Davidoff, P., & Gold, N. N. (1970a). Exclusionary zoning. Yale Review of Law & Social Action, 1, 56. https://pauldavidoff.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Article-Exclusionary-Zoning_.pdf

- Davidoff, L., & Gold, N. N. (1970b). Suburban action: Advocate planning for an open society. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 36(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944367008977275

- Doane, A. W. (2013). Rethinking Whiteness studies. In A. W. Doane & E. Bonilla-Silva (Eds.), White out: The continuing significance of racism (pp. 3–19). Taylor and Francis.

- Dorries, H., & Harjo, L. (2020). Beyond safety: Refusing colonial violence through indigenous feminist planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 40(2), 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19894382

- The Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston. (n.d). 1917: Buchanan v. Warley. Historical Shift from Explicit to Implicit Policies Affecting Housing Segregation in Eastern Massachusetts. https://www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1917-Buchanan-v.Warley.html

- Fainstein, S. (2010). The just city. Cornell University Press.

- Fields, B. J. (2001). Whiteness, racism, and identity. International Labor and Working-Class History, 60(60), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547901004410

- Fraser, J. C., Burns, A. B., Bazuin, J. T., & Oakley, D. Á. (2013). HOPE VI, colonization, and the production of difference. Urban Affairs Review, 49(4), 525–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087412465582

- Fraser, N. (1999). Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition, and participation. In L. Ray & A. Sayer (Eds.). Culture and economy after the cultural turn (pp. 25–52). Sage.

- Freeman, L. (2005). Displacement or succession? Residential mobility in gentrifying neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review, 40(4), 463–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087404273341

- Freeman, L. (2011). There goes the hood: Views of gentrification from the ground up. Temple University Press.

- Freeman, L., & Braconi, F. (2004). Gentrification and displacement New York City in the 1990s. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360408976337

- Frick, K. T., Chapple, K., Mattiuzzi, E., & Zuk, M. (2015). Collaboration and equity in regional sustainability planning in California: Challenges in implementation. California Journal of Politics and Policy, 7(4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5070/P2CJPP7428924

- Frieden, B. J., & Kaplan, M. (1975). The politics of neglect: Urban aid from model cities to revenue sharing. MIT Press.

- Friedmann, J. (1993). Toward a non-Euclidian mode of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 59(4), 482–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369308975902

- García, I. (2018). Community participation as a tool for conservation planning and historic preservation: The case of “Community as a Campus” (CAAC). Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 33(3), 519–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9615-4