ABSTRACT

In this editorial, we address the concepts of diversity, multiculturalism, equity, racial equity, racism, anti-racism, and intersectionality in urban planning. Despite their significance, these concepts have not received sufficient attention in the mainstream planning discourse. We argue that prioritizing anti-racism is essential for fostering effective anti-racist praxis in planning, leading to institutional and structural change. The special issue introduces key terms and papers, highlighting the importance of context, intersectionality, and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC)/community-led initiatives. In addition, we emphasize the need for reparative planning practices to address historical injustices and disrupt structural racism in the planning field. We call on urban planners to integrate anti-racism as a core principle in their praxis. By dismantling entrenched systems of racism and embracing intersectional approaches, the field of urban planning can contribute significantly to the pursuit of equitable and inclusive urban environments for all. Prioritizing anti-racism, embracing intersectionality, and incorporating reparative planning practices are crucial steps for urban planners to create institutional and structural changes in the planning field. Integrating anti-racism as a core principle can lead to more equitable and inclusive urban environments, addressing historical injustices and promoting positive transformations.

This special issue is dedicated to understanding and exploring how urban planning can respond to ongoing calls of social movements associated with anti-racism, such as the Movement for Black Lives, Stop Asian American and Pacific Islander Hate, Trans Lives Matter, and Undocumented and Unafraid, among others. The issue also acknowledges and responds to appeals to embed diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in urban planning practices and expand them to include anti-racism. Some of the questions raised in this special issue include: How can planners reorient toward an anti-racist praxis to disrupt racist and colonial planning practices within the academy and on the ground in communities? How can community organizations and municipalities work toward implementing and institutionalizing racial equity and reparative planning practices? These questions are addressed through case studies from across the United States.

We decided to pursue this special issue shortly after the nationwide anti-racism protests of spring/summer 2020, when George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Rayshard Brooks, among others, died in police custody. At the time, we found ourselves at a crucial juncture in history, marked by heightened public awareness during a period of racial reckoning. We believe it is imperative to document the response of state, regional, or municipal planning and higher education to the changing landscape centering racial justice in the planning field. Now, in 2023, we are again at a critical juncture where there is a strong right-wing backlash to social movements focused on Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, Two-Spirit (LGBTQIA2S+) populations with anti-Black, anti-LGBTQ, and anti-DEI legislation being passed in states such as Florida, Texas, and Iowa, among others. As this hostile legislation sweeps across the United States, the work on anti-racism and decolonial planning practices is needed to challenge and dismantle the systemic barriers and inequalities that perpetuate injustice in society. Our aim is thus to offer practitioners tangible strategies for implementing anti-racist and decolonized planning practices that are adaptable and responsive rather than fixed or everlasting.

Transforming the culture of White privilege in workplaces, professional and institutional practices, and education remains one of planning’s most significant challenges (Lee & Arroyo, Citation2022; Solis, Citation2020). Planning institutions have played a vital role in enshrining White supremacy in the built environment (R. Williams, Citation2020). Today, planners still uphold White supremacy through land use decisions and exclusionary zoning, among other mechanisms (Harwood, Citation2005; Yerena, Citation2020). Despite some hopeful and inspiring examples in past decades, planning policies have largely failed to rectify systemic racism (Goetz et al., Citation2020; Solis, Citation2020; Yerena & Casas, Citation2021).

Similarly, planning education too often falls short. Several scholars have argued that promoting equity and social justice remains a goal of planning practice, although a gap remains between how institutions train planners to work in diverse communities and the knowledge, awareness, and skills required to become culturally aware, humble, and competent practitioners (Agyeman & Erickson, Citation2012; Lung-Amam et al., Citation2015; Sweet, Citation2018). These observations are affirmed by students and practitioners, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds, who recognize gaps between values, teaching, and practice (García et al., Citation2021; Greenlee et al., Citation2018; Jackson et al., Citation2020). Entrenched legacies of White supremacy, especially tied up in property ownership and rights, limit the organizational and procedural opportunities many practicing planners can imagine to pursue meaningful change toward more equitable and socially just planning policies and practices (Goetz et al., Citation2020; Lee & Arroyo, Citation2022; Solis, Citation2020).

Although the field of planning is increasingly proactive in promoting equity and centering racial justice, there is much work to be done to redress harm caused by urban planning policies and plans. There is clearly a desire to discuss and share anti-racist work in planning, as evidenced by the response to the call for submissions to this special issue; we received 87 abstracts and invited 42 to submit full papers. The 12 articles in this special issue push planning scholars, educators, and practitioners to contend with the racist origins of the field and profession, disrupt racial inequality, and dismantle current racist, colonial, and discriminatory planning policies and practices to redress harm experienced by communities of color and move toward reconciliation.

In this editorial, we untangle the concepts of diversity, multiculturalism, equity, racial equity, racism, anti-racism, and intersectionality, among other key discourses including race, a socially constructed identity category (Omi & Winant, 1986). Although most of these concepts have been discussed in planning, they have largely remained outside the mainstream. Furthermore, anti-racism in planning has yet to be pushed forward by the field in the concerted manner needed to bring about any institutional or structural systems change. We see defining anti-racism as the first step to creating an effective anti-racist praxis for urban planning. We argue that anti-racism must be prioritized to advance a field that actively disrupts structural racism.

In addition, we define terms to orient readers to the special issue. We first summarize diversity and multiculturalism. Next, we present a working definition of equity, racial equity, racism, anti-racism, decolonization, and reparative planning. We then outline the papers published in the special issue based on our taxonomy, which includes a wide range of topics that contribute to building planning’s anti-racist praxis on racial equity, anti-racism, and reparative planning. Finally, we posit that anti-racist praxis must be contextual and intersectional. Planners must avoid universalized, race-neutral, or one-size-fits-all orientations in favor of BIPOC/community-led comprehensive approaches to anti-racist work. We also argue that the planning field must push for reparative planning practices that aim to redress harm and are movement led.

Diversity and Multiculturalism

Many demographers have documented how immigration has been a significant driver of cultural diversity—language, nationality, religion, ethnicity, race, and so on (Hallocket al., Citation2018; Lopez et al., Citation2018). However, for a long time, planners, especially in the communicative planning tradition of Habermas (Citation1991), have assumed a homogeneous public with a single public interest (Mattila, Citation2016). Postmodern scholars in the tradition of Foucault (Citation1980) and Lyotard and Jameson (Citation1984) changed this notion. As a result, planning organizations following a more modern tradition have been forced to deal with the housing, transportation, and economic development needs of diverse groups (Blancero et al., Citation2018; Chattaraman et al., Citation2009). Because of this profound and undeniable need to serve multicultural communities, planning organizations have sought to hire employees from diverse backgrounds (Greenlee et al., Citation2015, Citation2022).

In turn, several planning schools have strengthened their curriculum in engaging with diverse communities (Greenlee et al., Citation2022; Hibbard et al., Citation2011; Jackson, García-Zambrana, et al., Citation2018; Jackson, Parker, et al., Citation2018; Lung-Amam et al., Citation2015; Manning Thomas, Citation2019; Sen, Citation2005). Planning organizations today are more likely than in the past to hire a diverse workforce (Cuyjet et al., Citation2016; García et al., Citation2021; Gibson & Fernandez, Citation2018). Still, the same planning organizations continue to struggle to foster an inclusive climate or to provide this diverse workforce—in particular, African American, Black, and Latine planners—with wages comparable with those of Whites and individuals from some Asian groups for doing the same job (APA, Citation2018; Patten, Citation2016). To be sure, merely diversifying the workforce does not guarantee the bias and discrimination experienced by people of color will be eradicated (Jackson et al., Citation2020). These shortcomings, in addition to status-based hiring (Lee, Citation2022), have limited the extent to which planners can embrace diversity and multiculturalism.

To operationalize multiculturalism, UNESCO has identified three pillars: 1) a change in demographics due to globalization; 2) a principle upholding equal rights or access to political, economic, and other societal opportunities; and 3) a government strategy to include marginalized groups in the democratic process (Inglis, Citation2007). By joining these three pillars, a coherent picture emerges of how planners can embrace multiculturalism. Many planners—especially those working from advocacy, equity planning, and community organizing frameworks—stand for the right of individuals and communities to plan with and for people from distinct identities, languages, values, and traditions (Burayidi, Citation2003; Harwood, Citation2007; Qadeer, Citation1997; Sandercock, Citation2000).

Because we live in a multicultural world and the identity of people and communities is very complex, some planning academic programs and organizations have started implementing cultural competency or humility training for planners (Jackson et al., Citation2018). To do their jobs effectively, planners need to learn and develop multicultural communication skills (García et al., Citation2019; Zapata, Citation2009). Cultural competency and humility help planners to work collaboratively with culturally diverse communities and create more inclusive places (Agyeman & Erickson, Citation2012; García, Citation2018; Meléndez, Citation2018; Sweet, Citation2018). Scholars of this special issue argue that understanding the role of planning in people’s everyday lives and negotiating differences arising from social and cultural diversity is key to building equitable communities. We next examine the term equity.

Equity

Equity is often defined in contrast to equality; both are important to planning practice. Equity entails people getting what they need, whereas equality refers to equal treatment before the law, which is necessary for justice. The movement of equity planning, initially championed in 1982 by Krumholz and revisited in 2015 by Zapata and Bates (Citation2015), and other planning scholars, asks planners to center their efforts on redistribution, channeling resources toward those who need it the most. These aims can be at odds with a generally “cautious and conservative” planning practice (Krumholz, 1982, p. 172), which tends to prefer less contentious or redistributional paths. Still, others have argued that an equity lens is essential to address the root causes of planning problems, like unhealthy housing and built environments (Chrisinger, Citation2023).

Equality also strongly resonates in planning; for example, Lung-Amam (Citation2015) pointed out that planners need to understand that zoning laws are applied the same to all, but these laws and ordinances can have disparate impacts for BIPOC individuals. Lung-Amam also showed that some cultural groups need multilingual signage or the ability to incorporate completely different facades than other parts of the city (e.g., Chinatowns). In this case, we might argue that equity is needed as a framework of urban governance in the legislative process to later administer laws and regulations with equality.

In both instances, the state has the institutional power to influence people’s choices. Some of these arguments are posed in the just city and right to the city debates (Fainstein, Citation2011; Harvey, Citation2012; Marcuse, Citation2009; Mitchell, Citation2003). In the just city, it is the responsibility of the state, through its technocratic power, to ensure that people’s rights are protected. In contrast, the right to the city is more skeptical of the ability of a state that has historically undermined people’s rights to effectively pursue ambitious urban reform agendas. However, both camps agree on the need to move from the theoretical realm to a practical approach to solve the disparate impact of policies on people of color (Marcuse et al., Citation2011).

Moreover, the concept of anti-racism raises important tensions within equity and equality. Equality, in terms of race relations, assumes a society in which race does not affect the distribution of resources (e.g., material goods), access to decision-making procedures (e.g., power), and opportunity (e.g., choice) to begin with. On the other hand, equity often pertains to achieving equal outcomes, which can inadvertently reinforce cultural imperialism by imposing a single oppressive standard on the diverse public (Sanyal & Bishwapriya, 2005). This approach may not align with equal opportunity, where different groups have the freedom to pursue their unique paths to success. Both notions oversimplify the complexities of these issues.

The goal of equality is to advocate for social justice, as clearly stated by Iris Marion Young (Citation2011): “When people say a rule or practice or cultural meaning is wrong and should be changed, they are usually making a claim of social justice” (p. 9). Still, there is no agreement among contemporary social movements on the parameters of this form of justice (e.g., are reparations needed to compensate for past oppression, and if so, how might they be implemented?). As seen in the recent Supreme Court actions of 2023 (National Public Radio, Citation2023), concepts such as affirmative action in workplaces and quotas in higher education are still highly contested.

Nonetheless, as described by the APA’s Code of Ethics (American Institute of Certified Planners, Citation2005), planners serve diverse publics and should drive social change that increases equity in our communities. To do that effectively, planners must advance “social justice” and learn to listen to communities that have been “disadvantaged” (e.g., in health outcomes) and “lack influence” (e.g., power and decision-making capacity; APA, 2016). Expanding planning as a profession further into the realm of issues facing people of color requires an understanding of how race relates to inequity in the first place. Therefore, we now turn to understanding racial equity.

Racial Equity

Race Forward and its core program, the Government Alliance on Race and Equity, defines racial equity as an outcome and a process (Race Forward, 2017). Racial equity is a process of eliminating racial disparities and improving outcomes for everyone. It is the intentional and continual practice of changing policies, practices, systems, and structures by prioritizing measurable change in the lives of people of color (Race Forward, 2017). Racial equity as a process means that people of color are leaders in creating and implementing plans, policies, programs, and practices that affect their lives. It also means that White people are confronting racism within themselves and the structural conditions that marginalize people of color. Racial equity as an outcome reflects the idea that racial identity alone should not dictate a person’s life outcomes or access to housing, transportation, health care, education, or employment, among others. Although equity and racial equity have a long-established history in the field (Arroyo & Sandoval, 2023; Bates, 2019; Davidoff, 1965; Krumholtz, 1986; Solis, Citation2020) questions remain about how planners actually walk the walk and move past merely talking the talk, especially because prevailing practices involve much of the action of creating more equitable programs and initiatives being left to grassroots organizations rather than being embedded in government agencies. Furthermore, though racial equity is included in the updated 2021 APA Code of Ethics, Part A, it is not included in Part B, which focuses on the enforceable component of racial integration in the context of achieving social justice (American Institute of Certified Planners, Citation2005). Brand (2015) and Arroyo and Sandoval (2023) have further argued that planning lacks an operationalized concept of racial equity and how planners can embed this in plans and policies.

Though the APA Code of Ethics does not include racial equity, many organizations across the United States are establishing and operationalizing racial equity and working with city agencies to embed practices within plans and policies. For instance, in 2004, the City of Seattle (WA) implemented a citywide racial and social justice initiative that brought race and racial equity to the forefront, with the goal to end institutionalized racism and race-based disparities in city government (City of Seattle, Citation2004). The racial and social justice initiative has provided racial equity support to city departments through training, technical assistance, hands-on facilitation, and community engagement. Also, in 2015, the City of Portland (OR) and its Parks Department implemented a 5-year racial equity plan to guide citywide and specific parks and recreation policies (Portland Parks and Recreation, Citation2017). The equity plan’s aspiration was that race would have no detrimental effect on people of color, refugee, or immigrant communities in accessing parks and natural areas. More recently, in 2021, the City of Chicago (IL) embarked on two significant racial equity efforts. The first was a racial equity impact assessment that established racial equity metrics and tools to allocate low-income housing tax credits for affordable housing (Chicago Department of Housing, Citation2021). The second was an unprecedented community development initiative that aims to reverse decades of disinvestment on Chicago’s South and West Sides through allocation of public, private, and philanthropic investment to support amenities, small businesses, public spaces, and housing (Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Citation2019). Other cities such as Minneapolis (MN), Madison (WI), Tacoma (WA), and San Francisco (CA) have also embarked on substantive racial equity planning initiatives.

Redressing racism in institutional programs, policies, and plans is necessary to reverse institutional disinvestment and discrimination in U.S. cities. Although racial equity is part of the general planning field, it was not until recently that there was an increase in city agencies working toward operationalizing racial equity into plans in efforts to redress harm from ongoing racist planning practices that continue to marginalize communities of color. Advancing racial equity planning across the United States is a first step toward achieving racial justice, which will be addressed further in our discussion of reparative planning.

Racism

Now we focus on the definition of racism. This term is usually used to describe the deeply entrenched and widely prevailing belief of superiority and inferiority of one race over another (e.g., White people being superior to Black people, which leads to racism; Kendi, Citation2019). Racism in practice is manifested in myriad ways, from overt acts of oppression and violence to arguably more subtle ways such as differential access to material goods, power, and decision-making capacity. Racism is a system that exists without the intentional beliefs or actions of individuals: It privileges White people at the expense, marginalization, and exploitation of people from other races.

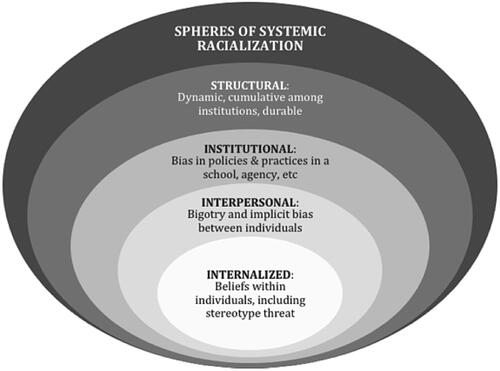

We further categorize racism into four levels: 1) internalized racism, 2) interpersonal racism, 3) institutional racism, and 4) structural racism. Internalized racism manifests itself when individuals from marginalized races adopt an ideology that sustains White privilege by believing, and thus perpetuating, disempowering racist stereotypes, narratives, values, and ideologies about one’s racial group (Pyke, Citation2010). Interpersonal racism is often identifiable in planning workplaces and institutions of higher learning in the form of prejudice, bias, and discrimination (García et al., Citation2021; Jackson et al., Citation2020). These acts can be overt (e.g., calling the police on an unknown but fellow Black worker) or subtle (e.g., microaggressions; García et al., Citation2021; Harwood et al., Citation2015). Institutional racism includes systemic decisions and policies that distribute resources, power, and opportunity within institutions and systems of power to benefit White people and harm people of all other races (J. Williams, Citation1985). Structural racism, also called systemic racism, refers to the structures or processes created and maintained by groups with power working among institutions such as governments, businesses, or schools and across society (Ahmed, Citation2012; Whittemore, Citation2017). Institutional racism upholds public policies, institutional practices, and cultural representations that reinforce racial inequality (Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change, Citation2004). This form of racism is embedded in laws and regulations that create and sustain racial inequities, which include internalized, interpersonal, and institutional racism. These forms of racism overlap and further reinforce and amplify already existing inequality. To understand racism, we must define and understand the broader systems and institutions that perpetuate racism and how people and individuals experience racism ().

Although racism is commonly understood as the belief in the superiority or inferiority of one race over another, planners primarily focus on institutional or structural racism. This means that planners’ attention is directed toward the systemic and institutionalized forms of racism that are embedded within policies, practices, and structures, rather than solely on individual beliefs or attitudes. By addressing institutional and structural racism, planners aim to dismantle the barriers and inequalities that disproportionately affect marginalized communities and work toward creating more equitable and just urban environments. For example, by removing exclusionary zoning, which is often characterized by not allowing integrated land uses, including multifamily housing in neighborhoods of opportunity, planners have affected the housing, employment, transportation, and educational opportunities of people of color (Goetz, Citation2013, Citation2021; Whittemore, Citation2021).

A separate, yet related concept, White supremacy, can be defined as the construction of superiority based on race, where the economic and political system benefits Whites (Goetz, Citation2021; Sweet & Etienne, Citation2011). Whereas White privilege is much less about the societal position of any given White person (e.g., one must recognize that many Whites are also deprived of goods, services, and power) and more about emphasizing how oppression and domination through the enslavement of Blacks and the colonization of Indigenous people have shaped racial injustice against these groups in many policies, laws, and practices in the United States. This oppression and domination have led to historical injustices including exploitation, discrimination, marginalization, bias, and stereotyping, among other aspects of our societal and political arrangement (Young, Citation2011). White privilege persists because it racializes other groups to uphold White supremacy (Lee et al., Citation2021).

Looking to the future, planners have the tools to create conduits to better support people of color, both spatially and socially, while embracing sociocultural differences. Planners can use these tools to help identify the economic, transportation, housing, health, and placemaking needs of communities of color, especially those historically underserved and disadvantaged, and take affirmative action to further the goals of equity and social justice without imposing their preconceived notions. Embracing ethnoracial diversity supports the vibrancy of cities and improves the quality of life for all: This is foundational in the pursuit of anti-racism. We next delve deeper into the concept of anti-racism.

Anti-Racism (Including Intersectionality)

Anti-racism is becoming a more common term in planning-related scholarship and documents (Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning, Citation2020; Hoover & Lim, Citation2021; Knapp, Citation2022; Zoll, Citation2021) but with little clarification on its definition in theory or practice. Bonnett (Citation2000) was one of the earliest scholars to use and define the term. Bonnett defined anti-racism as “forms of thought and/or practice that seek to confront, eradicate and/or ameliorate racism” (2000, p. 4; see also Dei, Citation1997; Gilborn, Citation1995). Paradies (Citation2016) summarized the different forms of anti-racism, ranging from internal and interpersonal practices that seek to reduce prejudice and discrimination (Aquino, Citation2016; Beelmann & Heinemann, Citation2014; Nelson et al., Citation2011; Paluck & Green, Citation2009) to organizational change that assesses existing policies, diversity, and leadership (Curtis & Dreachslin, Citation2008; Welton et al., Citation2018) and ways to incorporate anti-racism in the classroom (Alderman et al., Citation2021; Knapp, Citation2022). Anti-racism also includes organized and everyday acts that challenge racism (Nash, Citation2003), particularly by those who are the targets of racism (Itaoui et al., Citation2021).

Hage (Citation2016) further detailed six functions of anti-racism:

Reducing the incidence of racist practices (in everyday and structural racism).

Fostering a non-racist culture.

Supporting victims of racism.

Empowering racialized subjects to fight racism in the long-term.

Transforming racist relations into better, alternative relations.

Fostering an a-racist culture in which racial identification is no longer a relevant or salient form of identification.

Despite the recognition of systemic inequities and the importance of addressing racial disparities, there remains a significant gap in actively incorporating anti-racist practices into planning processes. This acknowledgment highlights the urgent need for planners, policymakers, and institutions to prioritize anti-racism efforts, challenge discriminatory practices, and center equity and justice in all aspects of urban planning. Furthermore, as Crenshaw (Citation1991) noted, anti-racism work must also be intersectional and address other forms of oppression or power; otherwise, anti-racism will reproduce the subordination of other identities, such as women, individuals with disabilities, or transfolx.

Decolonization

Settler colonialism is not a moment in history that we have surpassed; indeed, it is still pervasive in legal and economic systems—effectively a hegemonic bloc—whereas decolonization operates against the grain of settler colonial systems (Alexander, 1994; Cortés-Ramírez, Citation2015; Cox, 2002; Hall, 1986). Settler colonialism operates at the expense of Indigenous polities and epistemologies worldwide; for example, Lorenzo Veracini (Citation2010) differentiated between colonialism and settler colonialism: Settlers intend to stay and install a political regime. In the present-day United States, establishing a new ruling authority involves the assimilation of the existing indigenous populations, forcibly displaced African communities, and subsequent migrants. This assimilation process lies at the heart of ongoing efforts by settler states to undermine the sovereignty of indigenous nations, thus impeding their self-determination and ability to shape social and power dynamics that sustain their communities.

If settler colonialism erases peoples and their polities and epistemologies, then decolonization breathes life back into the ways of being in the world that settlers and their forms of governance attempted to erase. Within the United States, this was attempted through the theft of native nations’ land and Black people’s bodies and labor: slavery. Decolonization holds possibilities of a form of freedom from settler violence. It can mean that planning solutions originate within the community and do not need permission or clearance: It is a form of self-determining freedom that operates within the community (Harjo, Citation2019). A concrete example of this concept is the reclamation of public spaces, repurposing them as platforms for actively embracing local knowledge praxis and decolonized relationality. An illustrative case shared by Harjo (Citation2019) is that of a Mvskoke teacher who created such a space in a predominantly White junior high school for Mvskoke students. In other cases, it can present itself as Black and Indigenous farmers suing the U.S. Department of Agriculture for blocking them from obtaining federal farm loans; in the Keeps Eagle and Pickford cases, the farmers were aiming for justice within settler structures (Copeland, Citation2015). Either way, each of these moves sought to enact decolonial practices that uphold the steadfast values of Indigenous communities.

Furthermore, Indigenous research methods can be drawn upon to carry out planning practices: methodologies that engender relationality, reciprocity, and recognizing the lifeforce of human and more-than-human kin (Harjo, Citation2019; Todd, 2017; White, Citation2018). This positions planning as a more encompassing venture: What does it mean to center planning around a fish, or bison, or another form of more-than-human kin that is central to the societies of the first peoples of the land? Practices of decolonization shift and complicate community planning.

Reparative Planning

There have been renewed calls to action by the Movement for Black Lives and several city agencies in the United States for reparations to redress past and ongoing harms against African Americans (M4BL, 2016, 2020). Calls for reparations for African descendants of slaves have included forms of restitution such as land transfers or direct payments. Though reparative planning remains a relatively new facet to urban planning, calls for reparations are not new. The reparative planning turn builds on traditions of advocacy planning (Davidoff, 1965) and moves beyond equity and racial equity planning, aiming to disrupt and dismantle racist systems, institutions, and practices by redressing harm through planning policies.

R. Williams (Citation2020) has conceptualized reparative planning as a) linkage between material and symbolic demands for corrective justice, b) redressing harm, c) confronting White supremacy with reparative justice goals, and d) led by African American communities. In this issue, Song and Mizrahi build on this conceptualization to examine infrastructural systems as a major area of racial harm through the Alliance for Community Transit–Los Angeles (ACT-LA) Reimaging Safety initiative. In this case, reparative planning takes the form of redressing harm and redistribution of resources and is movement led by activists on the ground. Williams extends his conceptualization of reparative planning to identify five principles for reparative planning to include creating spaces for Black joy, material redistribution, intersectionality, building new democratic institutions of non-elites, and constructing environmentally just futures. The reparative turn in planning is still evolving, including social and institutional efforts to move toward accountability and reconciliation for past and ongoing harms to the Black community.

There are several recent efforts to address the impacts of structural racism by instituting reparations. The city council in Asheville (NC) has approved a reparation initiative that will create funded programs to increase homeownership and business development opportunities for Black residents (Vigdor et al., Citation2002). In 2019, the City of Evanston (IL) became the first city to make reparations available for Black residents for past housing discrimination and the continued impacts of the legacy of slavery (Associated Press, Citation2021). Black residents who have lived in or are direct descendants of a Black person who lived in Evanston between 1919 and 1969 are eligible for $25,000 toward home repairs or down payment on property. Money is drawn from a startup fund of $400,000 from recreational marijuana revenue sales, which includes a pledge from the City to allocate $10 million over 10 years toward reparations. Collectively, these strategies can work toward closing the inequality gap caused by structural racism. More recently, the California Reparations Task Force has completed a report and recommendations for compensation to eligible African descendants of slaves for the harms of slavery (NBC News, Citation2023).

Outline of Article Contributions

Following Kendi’s (Citation2019) proposition, we, the editors of this special issue, propose that anti-racism is a commitment to not only the recognition of race relations but its transformation. It is essential in the form of an idea and an active approach to fighting racism and its effects. Anti-racism facilitates the deconstruction of racist institutions; it also creates an environment that allows people to pursue their own interests and goals. Planners must recognize differences as opposed to suppressing them. The various authors in the issue propose that anti-racist praxis can be best achieved through understanding systems of oppression and domination among different groups and working toward emancipation and reconciliation. Next, we present an outline of the articles included in this special issue organized by four taxonomies: equity and racial equity, anti-racism, and reparative planning.

Equity and Racial Equity

In their contribution to this issue, Meléndez and Hoff investigate the impacts of including members of the public in collaborative governing bodies (e.g., committees, boards, planning commissions) among first- and second-generation immigrants as a practice of urban governance. Their work informs planners about the qualities of the culture of a governing body, including its members and staff, that affect their ability to successfully welcome racially diverse individuals in their work. Related, Arroyo et al. define racial equity planning as planning that aims to ameliorate historically racist policies, programs, and actions through redistribution of resources and ethnic and racial representation in processes and outcomes. Their piece offers progressive planners alternative policies, strategies, and programs to use across diverse communities. As an example of racial equity planning, Walker and Derrickson investigate how data on racial covenants influenced planning practice in the Twin Cities (MN). Their study uncovers whether and how engagement with data on structural racism might meaningfully advance anti-racist planning outcomes that enhance the self-development and self-determination of racially marginalized communities. Similarly, Besser et al. evaluate the inclusion of racial/ethnic equity considerations in health impact assessment reports for planning-related projects involving parks and greenspaces in the United States as a way for urban planners, health impact assessment practitioners, decision makers, and communities of color to work together to combat racist planning practices through the shared goals of addressing health disparities and build equity.

Anti-Racism

Articles in this special issue include examples of anti-racism in the planning profession by re-examining land use, planning tools, and planning history. For example, D. A. Williams et al. use land use cases in six cities to illustrate how White supremacy was historically codified into land use and how planners can advance anti-racism in the future by reconsidering the ways that zoning, borders, and laws have perpetuated racism. Oberly and Reece similarly review planning history but instead through a narrative that centers Black experiences to then help empower this racialized group, which has been excluded, devalued, and oppressed by the planning profession. Through this reimagined history of the field, the authors argue that the profession can empower Black communities in the United States by acknowledging their ongoing fight against racism and to move planning curriculum away from only memorializing and praising White planners. Garboden’s Viewpoint introduces the “rents of Whiteness” and how planners extract profits from legal and social exclusion, with considerations for how the profession can support victims of racism through mechanisms such as scoring systems that measure exclusion and just redistribution of land. Kenyatta conducted a meta-analysis of Black urbanism literature and encourages researchers to avoid race-neutral language and calls for more research on devalued socio-spatial practices in the profession.

Also in this issue, Lin and Patraporn highlight how a cross-racial intersectional coalition in Long Beach worked to broaden the power and representation of Black, Latinx, and Asian American youth through multipronged community engagement strategies that worked to reduce racist practices and foster collective care.

Reparative Planning

We close this special issue with several articles that make the case for a reparative turn in the planning field. Sweet and Harper draw from two case studies in Richmond (VA) and Norristown (PA) to illustrate ways to support healing justice through community accountability. This framework acknowledges the past and current harm caused by planners and the aim to ground work in spatial imaginaries that reflect the values, needs, and cultures of the communities planners serve. Next, Song and Mizrahi extend this framework to highlight the case study of ACT-LA, which explores infrastructural systems as a major area of racial harm through ACT-LA’s Reimaging Safety initiative. This initiative shows ways that activists and planners can replace existing racialized policing practices with public investments in community-based systems of safety to redress harm through reparative planning. And last, Rashad Williams builds on the reparative turn in planning to further identify the dimensions for reparative planning by centering anti-Black racism. This article integrates Black radical thought and debates in political philosophy and planning theory to put forth a framework of reparative planning exploring three case studies.

Anti-Racist Futures

We contend that simply learning about past harms through limited planning history modules does not adequately equip planners with frameworks and tools required to build a more equitable future. An anti-racist praxis is iterative and vital to confront the history of urban planning’s exclusionary practices rooted in a legacy of systems of oppression through historical perspectives (e.g., reckoning) insofar as they point toward future outcomes planners can work toward (e.g., acknowledgment, reconciliation, healing). This issue examines the underrepresentation and persistent discrimination of BIPOC and historically marginalized populations to provide recommendations for anti-racist, just, and inclusive environments.

All authors in this issue shed light on indirect anti-racism and direct anti-racism. However, these authors emphasize the importance of approaching anti-racism as a continual and ongoing process. They are not offering unified and universal solutions, and this issue does not make any claims to be the definitive reading on how to be anti-racist or how to achieve an anti-racist future. Some of the ideas offered by authors have not been tried yet in the planning field and await others to implement transformative practices. Their work still gives us all greater depth on implementable actions that planners and others can use to envision an anti-racist future and keep working at it incrementally, even when we need transformation now!

Furthermore, many of the questions we raised in our initial call for papers still await a response. For example, how can we explore movements to decolonize curricula and expertise in the planning academy and profession and establish long-term commitments to anti-racist initiatives or DEI within institutions and the Planning Accreditation Board? Many of these articles raise even more questions, such as how to assess the success of racially diverse boards and commissions in shifting the culture of their city or the need for reviews of planning history discourse beyond U.S. settings to generate transnational themes of oppression and resistance across the African diaspora. Notably, in an increasing number of U.S. states, these nascent efforts now face state-sanctioned limits on how topics of racism, colonialism, and inequality can be taught in higher education. Further research is desperately needed.

As authors in this issue have noted, the planning field has started to document grassroots and community efforts confronting racism and integrate this work within local, county, and regional agency plans and policies. However, scholars must keep documenting ongoing and current plans and policies that address racist, race-neutral, or anti-racist policies. Through this approach, the authors and editors of this special issue encourage the planning profession to take bold steps toward building an anti-racist practice by identifying, eliminating, and transforming practices and beliefs that enable racism. We want to take you to a space of possibility: Planning does not have to be this way. Let us explore together our unrealized possibilities.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

April Jackson

APRIL JACKSON ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban Planning and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is an expert in implementation of racial equity and inclusion in mixed-income communities, institutions, and workplaces, as well as community engagement and planning with communities of color. Her work also examines how institutions and workplaces promote diversity, equity and inclusion.

Anaid Yerena

ANAID YERENA ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor in the School of Urban Studies at the University of Washington Tacoma. Her scholarly contributions to urban and regional planning are related to housing and community development in the U.S. and Mexico, the work of advocacy organizations, social inequality, and urban governance. Her work investigates the factors influencing local affordable housing policies and practices with a special interest in the impact of community organizations on public decision-making processes.

C. Aujean Lee

C. AUJEAN LEE ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor in City & Metropolitan Planning at the University of Utah. Her research examines residential segregation and impacts on housing, community institutions, and wealth particularly for communities of color and immigrant populations. Her work also assesses government rhetoric and comprehensive plans to understand how or when planners are planning for racial equity or color-evasiveness.

Ivis Garcia-Zambrana

IVIS GARCIA-ZAMBRANA ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning at University of Texas A & M. Her philosophy, methodology and ethos revolves around conducting research and plans in partnership with stakeholders, being from the grassroots or from institutionalized forms of government. Dr. Garcia is an urban planner with research interests in the areas of community development, housing, and identity politics.

Ben Chrisinger

BEN CHRISINGER ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor in the Department of Community Health at Tufts University. He conducts interdisciplinary research on the relationships between place and health, especially health disparities, and the role that place-based policies can improve health equity. He is also engaged with using new technologies and community-engaged methods in research.

Laura Harjo

LAURA HARJO ([email protected]) is a Mvskoke scholar and an Associate Professor teaching Indigenous Planning, Community Development, and Indigenous Feminisms. Her scholarly inquiry is at the intersection of geography and critical ethnic studies with “community” as an analytic focus. Harjo’s research and teaching centers on three areas: imbuing complexity to Indigenous space, and place; Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Relatives and anti-violence; and community-based knowledge production.

Stacy Harwood

Stacy HARWOOD ([email protected]) is Chair and Professor in the City & Metropolitan Planning Department at the University of Utah. She is an urban planning scholar and educator on immigration, community development, racial justice and local public policy. She has also established a long-standing track record in providing technical assistance to community organizations and developing innovative approaches to teaching in the classroom.

References

- Agyeman, J., & Erickson, J. S. (2012). Culture, recognition, and the negotiation of difference: Some thoughts on cultural competency in planning education. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 32(3), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X12441213

- Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press Books.

- Alderman, D., Narro Perez, R., Eaves, L. E., Klein, P., & Munoz, S. (2021). Reflections on operationalizing an anti-racism pedagogy: Teaching as regional storytelling. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 45(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2019.1661367

- American Institute of Certified Planners. (2005, revised 2021). AICP code of ethics and professional conduct. https://www.planning.org/ethics/ethicscode/

- American Planning Association (APA). (2018). APA planners salary survey summary. https://www.planning.org/salary/summary/

- Aquino, K. (2016). Anti-racism “from below”: Exploring repertoires of everyday anti-racism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(1), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096408

- Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change. (2004). Structural racism and community building. Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/files/content/docs/rcc/aspen_structural_racism2.pdf

- Associated Press (2021). Illinois city 1st in US to offer Black residents reparations. https://apnews.com/article/reparations-evanston-illinois-black-residents-752a6fe83c560117523d7f8abba1bfb8

- Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning. (2020). Anti-racism within ACSP. https://www.acsp.org/page/ACSPStatement

- Beelmann, A., & Heinemann, K. S. (2014). Preventing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent training programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.11.002

- Betancur, J. J. (1996). The settlement experience of Latinos in Chicago: Segregation, speculation, and the ecology model. Social Forces, 74(4), 1299–1324. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/74.4.1299

- Blancero, D. M., Mouriño-Ruiz, E., & Padilla, A. M. (2018). Latino millennials – The new diverse workforce: Challenges and opportunities. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 40(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986317754080

- Bonnett, A. (2000). Anti-racism. Routledge.

- Burayidi, M. A. (2003). The multicultural city as planners’ enigma. Planning Theory & Practice, 4(3), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000118634

- Chan, W. F. (2004). Finding Chinatown: Ethnocentrism and urban planning. In D. Bell and M. Jayne (Eds.), City of quarters (pp. 173–190). Ashgate Publishing. https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/1358/

- Chattaraman, V., Rudd, N. A., & Lennon, S. J. (2009). The malleable bicultural consumer: Effects of cultural contexts on aesthetic judgments. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.290

- Chicago Department of Housing. (2021). Racial equity impact assessment, qualified allocation plan. https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/depts/doh/qap/qap_2021/2021_REIA_QAP.pdf

- Chicago Department of Planning and Development. (2019). Invest South/West. https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/sites/invest_sw/home.html

- Chrisinger, B. W. (2023). Getting to root causes: Why equity must be at the center of planning and public health collaboration. Journal of the American Planning Association, 89(2), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2041466

- City of Seattle. (2004). Race and social justice initiative. https://www.seattle.gov/rsji/about

- Copeland, R. W. (2015). Post-Pigford remedies for African-American farmers may include promissory and equitable estoppel. Western Journal of Black Studies, 39, 209.

- Cortés-Ramírez, E. E. (2015). Cultural hegemony today: From cultural studies to critical pedagogy. Postcolonial Directions in Education, 4(2), 116–139.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity, politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Curtis, E. F., & Dreachslin, J. L. (2008). Integrative literature review: Diversity management interventions and organizational performance: A synthesis of current literature. Human Resource Development Review, 7(1), 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484307311700

- Cuyjet, M. J., Linder, C., Howard-Hamilton, M. F., & Cooper, D. L., (Eds.). (2016). Multiculturalism on campus: Theory, models, and practices for understanding diversity and creating inclusion (2nd ed.). Stylus Publishing.

- Dei, G. J. S. (1997). Anti-racism education: Theory and practice. Fernwood Publishing.

- Fainstein, S. S. (2011). The just city, 1st ed. Cornell University Press.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977. C. Gordon (Ed.), 1st ed. Vintage.

- García, I. (2017). Paseo Boricua: Identity, symbols, and ownership. América Crítica, 1(2), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.13125/américacrítica/3014

- García, I. (2018). Adaptive leadership and social innovation: Overcoming critical theory, positivism, and postmodernism in planning education. Journal of Public Affairs. http://www.ejournalofpublicaffairs.org/adaptive-leadership-and-social-innovation-overcoming-critical-theory-positivism-and-postmodernism-in-planning-education/

- García, I., Garfinkel-Castro, A., & Pfeiffer, D. (2019). Planning with diverse communities. Planning Advisory Service (PAS) Report 593. American Planning Association. https://www.planning.org/publications/report/9165143/

- García, I., Jackson, A., Greenlee, A. J., Yerena, A., Chrisinger, B., & Lee, C. A. (2021). Feeling like an “Odd Duck”: The experiences of African American/Black and Hispanic/Latin/o/a/x planning practitioners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(3), 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1858936

- García, I., Jackson, A., Harwood, S. A., Greenlee, A. J., Lee, C. A., & Chrisinger, B. (2021). “Like a fish out of water”: The experience of African Americans and Latinx in U.S. planning programs. Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(1), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1777184

- Garcia-Hallett, J., Like, T., Torres, T., & Irazábal, C. (2020). Latinxs in the Kansas City Metro Area: Policing and criminalization in ethnic enclaves. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 40(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19882749

- Gibson, S., & Fernandez, J. (2018). Gender diversity and non-binary inclusion in the workplace: The essential guide for employers. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Gilborn, D. (1995). Racism and antiracism in real schools. Open University Press.

- Giusti, C., Olivares, M., & Olivares, M. (2012, June 25). Latinos and incremental construction: A case study of Texas Colonias. Diálogos: Placemaking in Latino Communities. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203123676-16

- Goetz, E. G. (2013). New Deal ruins: Race, economic justice, and public housing policy. First paperback printing edition. Cornell University Press.

- Goetz, E. G. (2021). Democracy, exclusion, and white supremacy: How should we think about exclusionary zoning? Urban Affairs Review, 57(1), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419886040

- Goetz, E. G., Williams, R. A., & Damiano, A. (2020). Whiteness and urban planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(2), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1693907

- Greenlee, A. J., Edwards, M., & Anthony, J. (2015). Planning skills: An examination of supply and local government demand. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(2), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15570321

- Greenlee, A. J., Jackson, A., Garcia-Zambrana, I., Lee, C. A., & Chrisinger, B. (2022). Where are we going? Where have we been? The climate for diversity within urban planning educational programs. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(3), 331–349. December. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18815740

- Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (6th printing edition). The MIT Press.

- Hage, G. (2016). Recalling anti-racism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(1), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096412

- Hallock, J., Zong, J., Batalova, J. (2018, February 2). Frequently requested statistics on immigrants and immigration in the United States. Migrationpolicy.org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states

- Harjo, L. (2019). Spiral to the stars: Mvskoke tools of futurity. University of Arizona Press.

- Harvey, D. (2012). Rebel cities: From the right to the city to the urban revolution. Verso Books.

- Harwood, S. A. (2005). Struggling to embrace difference in land-use decision making in multicultural communities. Planning Practice and Research, 20(4), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450600766746

- Harwood, S. A. (2007). Geographies of opportunity for whom? Neighborhood improvement programs as regulators of neighborhood activism. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 26(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X06298088

- Harwood, S. A., Choi, S., Orozco Villicaña, M., Huntt, R., & Mendenhall, R. (2015). Racial microaggressions at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Voices of students of color in the classroom. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Hibbard, M., Irazábal, C., Thomas, J. M., Umemoto, K., Wubneh, M. (2011). Recruitment and retention of underrepresented faculty of color in ACSP member programs: Status and recommendations. Diversity Task Force Report. https://cdn.ymaws.com/acsp.site-ym.com/resource/resmgr/files/CoD/ACSP_Diversity_Task_Force_Re.pdf

- Hoover, F.-A., & Lim, T. C. (2021). Examining privilege and power in US urban parks and open space during the double crises of antiblack racism and COVID-19. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 3(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00070-3

- Inglis, C. (2007). Policy Paper No. 4 – Multiculturalism: New policy responses to diversity. http://digital-library.unesco.org/shs/most/gsdl/cgi-bin/library?e=d-000-00–-0most–00-0-0–0prompt-10–-4–––0-1l–1-en-50–-20-about–-00031-001-1-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=most&cl=CL4.1&d=HASH01642e20b5302ceb94565abc

- Itaoui, R., Dufty-Jones, R., & Dunn, K. M. (2021). Anti–racism Muslim mobilities in the San Francisco Bay Area. Mobilities, 16(6), 888–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2021.1920339

- Jackson, A., Garcia, I., Chrisinger, B., Greenlee, A. J., Lee, C. A., Yerena, A. (2020). Diversity climate survey – Moving from aspiration to action: Reorienting planners values towards equity, diversity, and inclusion. American Planning Association and Planners of Color Interest Group. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34937.292891548207

- Jackson, A., Garcia-Zambrana, I., Greenlee, A. J., Lee, C. A., & Chrisinger, B. (2018). All talk no walk: Student perceptions on integration of diversity and practice in planning programs. Planning Practice & Research, 33(5), 574–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2018.1548207

- Jackson, A., Parker, M., DeVera, L. T., Garcia Zambrana, I., Holmes, T., Shiau, E., & Medina, C. (2018). Moving the needle: Early findings on faculty approaches to integrate culturally competent pedagogy into educational spaces. eJournal of Public Affairs, 7(2), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.21768/ejopa.v7i2.212

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. Random House Publishing Group.

- Knapp, C. E. (2022). Integrating critical autobiography to foster anti-racism learning in the urban studies classroom: Interpreting the “race and place” stories of undergraduate students. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(3), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18817822

- Lee, C. A. (2022). Who gets hired from the top? The academic case system theory in the planning academy. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2022, 0739456X2211216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X221121611

- Lee, C. A., & Arroyo, J. (2022). A typology of local and state government responses to racism: A case of anti-Asian hate in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2022, 0739456X2210845. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X221084592

- Lee, C. A., Flores, N. M., & Hom, L. D. (2021). Learning from Asian Americans: Implications for planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2021, 0739456X2110067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X211006768

- Lopez, G., Bialik, K., Radford, J. (2018, November 30). Key findings about U.S. immigrants. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/11/30/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/

- Lung-Amam, W. (2015). Malls of meaning: Building Asian America in Silicon Valley suburbia. Journal of American Ethnic History, 34(2), 18–53. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerethnhist.34.2.0018

- Lung-Amam, W., Harwood, S. A., Sandoval, G. F., & Sen, S. (2015). Teaching equity and advocacy planning in a multicultural “post-racial” world. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15580025

- Lyotard, J.-F., & Jameson, F. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. Trans by G. Bennington and B. Massumi, 1st ed. University Of Minnesota Press.

- Manning Thomas, J. (2019). Socially responsible practice: The battle to reshape the American Institute of Planners. Journal of Planning History, 18(4), 258–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513218786007

- Marcuse, P. (2009). From critical urban theory to the right to the city. City, 13(2–3), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810902982177

- Marcuse, P., Connolly, J., Johannes, N., Ingrid, O., Cuz, P., & Justin S., eds. (2011). Searching for the just city: Debates in urban theory and practice (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Mattila, H. (2016). Can collaborative planning go beyond locally focused notions of the “public interest”? The potential of Habermas’ concept of “generalizable interest” in pluralist and trans-scalar planning discourses. Planning Theory, 15(4), 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095216640568

- Meléndez, J. W. (2018). Aligning our pedagogy and practices with our cultural competency goals: Clarifying the learning continuum author note. eJournal of Public Affairs, 7(2), 222–240.

- Mitchell, D. (2003). The right to the city: Social justice and the fight for public space (1st ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Nash, C. (2003). Cultural geography: Anti-racist geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 27(5), 637–648. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph454pr

- National Public Radio. (2023, June 29). Supreme Court guts affirmative action, effectively ending race-conscious admissions. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/29/1181138066/affirmative-action-supreme-court-decision.

- NBC News. (2023). Everything you need to know about California’s reparations report. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/california-black-reparations-report-what-know-eligible-pay-rcna87811.

- Nelson, J. K., Dunn, K. M., & Paradies, Y. (2011). Bystander anti-racism: A review of the literature. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 11(1), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2011.01274.x

- Paluck, E. L., & Green, D. P. (2009). Prejudice reduction: What works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 339–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607

- Paradies, Y. (2016). Whither anti-racism? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096410

- Patten, E. (2016, July 1). Racial, gender wage gaps persist in U.S. despite some progress. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/01/racial-gender-wage-gaps-persist-in-u-s-despite-some-progress/

- Portland Parks and Recreation. (2017). Five-year racial equity plan: Furthering citywide racial equity goals and strategies. Portland Parks and Recreation.

- Pyke, K. D. (2010). What is internalized racial oppression and why don’t we study it? Acknowledging racism’s hidden injuries. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2010.53.4.551

- Qadeer, M. A. (1997). Pluralistic planning for multicultural cities: The Canadian practice. Journal of the American Planning Association, 63(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369708975941

- Sandercock, L. (1997). Towards Cosmopolis: Planning for multicultural cities. Academy Press.

- Sandercock, L. (2000). When strangers become neighbours: Managing cities of difference. Planning Theory & Practice, 1(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350050135176

- Sandoval, G. F. (2021). Planning the Barrio: Ethnic identity and struggles over transit-oriented, development-induced gentrification. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 41(4), 410–424. August. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18793714

- Sen, S. (2005). Diversity and North American Planning Curricula: The need for reform. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 14(1), 121–144.

- Solis, M. (2020). Racial equity in planning organizations. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(3), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1742189

- Sweet, E. L. (2018). Cultural humility: An open door for planners to locate themselves and decolonize planning theory, education, and practice. Journal of the American Planning Association, 7(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1742189

- Sweet, E. L., & Etienne, H. F. (2011). Commentary: Diversity in urban planning education and practice. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31(3), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X11414715

- Veracini, L. (2010). Settler colonialism: A theoretical overview. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230299191

- Vigdor, J. L., Massey, D. S., & Rivlin, A. M. (2002). Does gentrification harm the poor? [with comments]. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs, 2002(1), 133–182. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067387 https://doi.org/10.1353/urb.2002.0012

- Welton, A. D., Owens, D. R., & Zamani-Gallaher, E. M. (2018). Anti-racist change: A conceptual framework for educational institutions to take systemic action. Teachers College Record, 120(14), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811812001402

- White, H. (2018). Indigenous peoples, the international trend toward legal personhood for nature, and the United States. American Indian Law Review, 43(1), 129–165.

- Whittemore, A. H. (2017). Racial and class bias in zoning: Rezonings involving heavy commercial and industrial land use in Durham (NC), 1945–2014. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2017.1320949

- Whittemore, A. H. (2021). Exclusionary zoning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1828146

- Williams, J. (1985). Redefining institutional racism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 8(3), 323–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1985.9993490

- Williams, R. (2020). From racial to reparative planning: Confronting the white side of planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2020, 0739456X2094641. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20946416

- Yerena, A. (2020). Not a matter of choice: Eliminating single-family zoning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(1), 122–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1689014

- Yerena, A., & Casas, R. (2021). A place for life: Striving towards accessible and equitable public spaces for times of crisis and beyond. In R. van Melik & P. Filion (Eds.), Volume 3: Public space and mobility. Bristol University Press.

- Young, I. M. (2011). Justice and the politics of difference. With a new foreword by D. Allen. Princeton University Press.

- Zapata, M. A. (2009). Deliberating across differences: Planning futures in cross-cultural spaces. Policy and Society, 28(3), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2009.08.002

- Zapata, M. A., & Bates, L. K. (2015). Equity planning revisited. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 245–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15589967

- Zoll, D. (2021). We can’t address what we don’t acknowledge: Confronting racism in adaptation plans. In B. Petersen & H. B. Ducros (Eds.), Justice in climate action planning (pp. 3–23). Springer International Publishing.