Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings: Gentrification is often described as affluent White populations revitalizing deteriorating neighborhoods and displacing lower-income ethnic/racial residents. However, there is limited research on gentrification led by middle- and upper-class ethnic/racial minorities, which I propose calling gentrification of color. I reviewed 46 qualitative and quantitative studies on gentrification of color in U.S. cities from 1960 to 2021 and found a range of phenomena in terms of ethnicity/race, profiles, locations, preceding policies, and consequences of gentrification of color. These studies highlighted both solidarity and tensions within the same ethnic/racial groups as a result of gentrification. Gentrification of color presents both challenges and opportunities for minorities’ cultural inclusion. In addition, my study emphasized the role of policies enabling gentrification of color and the lack of affordable housing policies to address its consequences. The findings can encourage urban planners, policymakers, and scholars to adopt a policy approach that acknowledges the complex intersectionality of race/ethnicity and class.

Takeaway for practice: I urge urban planners and policymakers to incorporate the intersectionality of race/ethnicity and class into their approach to gentrification. On one hand, it is important for urban planners to collaborate with gentrifiers of color to foster culturally inclusive urban development. However, it is equally crucial for urban planners to acknowledge that issues such as displacement of lower-income individuals, intra-ethnic class disparities, and conflicting interests may be concealed under the notion of ethnic solidarity. Therefore, urban planning experts and policymakers should prioritize policies that support economically disadvantaged residents, such as affordable housing, while actively seeking their input and perspectives in municipal decision-making processes.

In this study, I present a comprehensive review and analysis of a distinct and relatively unexplored form of gentrification I refer to as gentrification of color. Scholars have commonly defined this phenomenon as the participation of people of color in investing in and revitalizing urban areas, often resulting in the displacement of lower-income residents. This occurrence is observed in various cities and ethnic/racial communities across the United States. The findings of this research have the potential to inspire urban planners and policymakers to foster culturally inclusive urban development, celebrate the cultural identity of the affected spaces, leverage the historical and cultural assets of ethnic communities, and address the need for affordable housing.

The dominant literature on gentrification has emphasized how class and race/ethnicity are intersecting dimensions that together constitute spatial marginalization. Gentrification studies have been largely preoccupied with the phenomenon of middle-class White families moving into disadvantaged areas and displacing working-class Black or ethnic minority communities (Kent-Stoll, Citation2020; Mele, Citation2017; Smith, Citation1979; Sutton, Citation2020). As research on gentrification has evolved, scholarship has moved toward making race and racialization central objects of study.

In segregated U.S. cities, gentrification has been attributed to racial capitalism (Melamed, Citation2015; Robinson, Citation2000), resulting in the displacement of people of color and the Whitening of predominantly Black and Latino urban neighborhoods (Arena, Citation2012; Huante, Citation2021; Hwang & Sampson, Citation2014; Kent-Stoll, Citation2020; Kipfer & Petrunia, Citation2009; Mele, Citation2017; Mumm & Sternberg, Citation2022; Rucks-Ahidiana, Citation2022; Sutton, Citation2020). Scholars have explored race not merely as an isolated variable, factor, or outcome in the process of gentrification but as a reflection of worth or value. The absence of such worth drives the real estate improvements that gentrifiers gain advantages from. In other words, gentrification relies on the social construction of race to generate land value and is facilitated by the displacement of people of color and the reinforcement of Whiteness to guarantee profitability (Hwang & Sampson, Citation2014; Mumm & Sternberg, Citation2022).

Though these studies have contributed to the understanding of the role of race in gentrification, people of color play multiple and complex roles in gentrification processes. They can be both displaced populations and gentrifiers who benefit from gentrification; in some cases, they contribute to the displacement of lower-income residents, whereas in others, they actively fight against it. Although the complex intersection between class and race/ethnicity in gentrification of color may lead to the mistaken notion that it is solely an intra-ethnic class matter, I contend that this phenomenon is connected to structural and policy processes.

In a similar vein, Mary Pattillo (Citation2007) has discussed the issue of intra-class conflict over public housing in North Kenwood–Oakland, Chicago (IL):

Even though the debates over public housing have seemed to be more about class than race, this is only true because of the genius of systemic racism. Past racism has so distorted the functioning of institutions and markets—here the housing market—that overt racism is no longer even necessary to ensure inequality, and the discriminatory racial history is no longer visible.… To the contrary, I argue that, appearances aside, the relevant framework for analyzing the case against public housing…is historical, structural, and interracial, rather than intraracial. [p. 182]

The emergence of a growing body of research focusing on diverse case studies of gentrification of color presents an opportunity to map, analyze, and conceptualize this phenomenon, its actors, the policies that are linked to its occurrence, and its consequences in a thorough and comprehensive manner.

Analyzing case studies of gentrification of color contributes to the knowledge and decision-making processes of urban planners, policymakers, and scholars in several significant ways. First, it emphasizes the possibility that gentrification may confer benefits to the gentrifying ethnic group and thus suggests a form of gentrification that is culturally inclusive. Moreover, understanding the motivations and solidarities of ethnic gentrifiers, which often extend beyond economic factors, enables urban planners to engage and collaborate with them on community projects (Boyd, Citation2005, Citation2008; Crisman, Citation2021; Moore, Citation2009; Sandoval, Citation2021; M. M. Taylor, Citation2002). For instance, urban planners can form partnerships with artists and cultural gentrifiers to empower the cultural identity of the area (Sandoval, Citation2021).

Simultaneously, my analysis has revealed that ethnic gentrifiers do not necessarily uphold the interests of their lower-class counterparts. It underscores the importance for urban planners to be mindful of the displacement of lower-income residents in these neighborhoods, because intra-ethnic tensions, hierarchies, and inequalities can be masked under the guise of ethnic unity. Therefore, it is crucial for urban planning experts and policymakers to give priority to policies that support economically disadvantaged residents and actively seek their perspectives when making municipal decisions.

Finally, my findings have revealed that although urban redevelopment policies are connected to gentrification of color, only a few studies analyzed here addressed policy efforts to deal with their social consequences. This review provides potential explanations for this gap and calls upon scholars to adopt a nuanced race–class intersectional perspective when studying gentrification of color. Such a perspective should not only consider the complex intersection between class and race/ethnicity in the gentrification process but also critically assess the role of planning and policy in both facilitating and mitigating the consequences of this phenomenon.

These findings and arguments are based on a comprehensive pioneering review of 46 quantitative and qualitative research papers on the phenomenon of gentrification of color. The research encompasses the initial years of gentrification studies up until those published by December 30, 2021. I aimed to address the following key questions:

What were the extent, localities, time periods, and profiles of gentrification of color in U.S. cities, as identified in the reviewed literature?

What were the policies that preceded the appearance of gentrification of color in the reviewed literature?

What were the social implications of gentrification of color (relationships between different classes within the same community and displacement) and the efforts made to deal with its consequences, as described in the reviewed literature?

I begin by describing the data and methods for this literature review and analysis. I then present my findings in six sections: 1) the frequency and research interest in gentrification of color; 2) analysis of gentrification of color: population, location, and period of time; 3) the profiles of gentrifiers of color: commercial, artist, developer, residential, and institutional; 4) the varying contexts of gentrification of color; 5) an analysis of the urban redevelopment policies that preceded or accompanied gentrification of color; and 6) the implication of gentrification of color and efforts made to deal with its consequences. In conclusion, I recommend that urban planners, policymakers, and scholars adopt an approach that acknowledges the complex intersectionality between class and race/ethnicity while also considering the impact of planning and policy on gentrification of color. By embracing this perspective, we can foster equitable and inclusive redevelopment processes.

Methods

Search Strategy

To identify studies published between 1960 and 2021 that examined gentrification of color in the United States, I performed a literature review between January and February 2022. I consulted four electronic databases: Sociological Abstracts, Scopus, Academic Search Complete, and Web of Science. These databases index journals from each of the major fields that have produced articles on gentrification and race/ethnicity/minority research. In addition, I conducted a snowball search examining the reference lists of all the cited studies.

I applied a selection criterion for study inclusion based on the definition of gentrification provided by the original authors of each study. Studies that acknowledged or explored the existence of gentrification in any form, encompassing different types, levels, and stages, were considered eligible for inclusion in this review. Studies that focused on urban redevelopment, renewal, and revitalization processes were not considered eligible unless the authors explicitly referred to them as gentrification or they were analyzed within the framework of gentrification.

I used a large variety of search terms in the given databases to find as many U.S. gentrification studies as possible. I used truncated terms to capture variation in terminology. For example, gentrif* caught the terms gentrification, gentrified, gentrifies, gentrify, and gentrifying. To capture the variety of ethnic groups that can take part in gentrification, I conducted searches using the following title, abstract, and keyword terms: (gentrif*) and Ethnic gentrif*; Ethnic-led gentrif*; nonwhite gentrif* Racial-led gentrif*; Racial gentrif*; B/black gentrif*; black-led gentrif*; African-american gentrif*; Hispanic-led gentrif*; Latinx/Hispanic gentrif*; Latino-led gentrif*; Latino gentrif*; Latin American gentrification; Self-led gentrify*; Self- gentrify*; Bottom-up gentrify*; Asian gentrify*; Asian-led gentrify*; Chinese gentrification; Minority gentrify*; Minority-led gentrify*; people of color gentrify*; indigenous gentrification; indigenous-led gentrification; gentrification from within; inter-ethnic gentrification; intra-ethnic gentrification; intra-racial gentrification; inter-racial gentrification; and Puerto-rican gentrification.

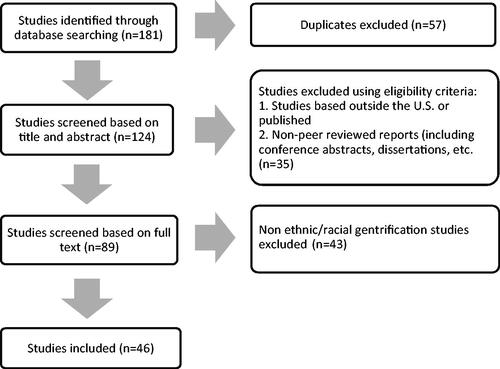

After the search phase, I consolidated the list of articles found from the databases into one file that included 181 results. I deleted duplicate articles found in more than one database from this list (n = 57), leaving 124 results ().

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

I completed title and abstract screenings using two eligibility criteria: First, I limited the search to articles in the English language with a U.S. study population.

Gentrification in the United States exhibits characteristics that differentiate it from gentrification processes in other countries. In addition, the conceptualization of race and ethnicity varies across countries, which limits the insights gained from comparing U.S. studies with those conducted elsewhere (Blum & Guérin-Pace, Citation2008). Therefore, I excluded studies conducted outside the United States. Second, I excluded non-peer-reviewed reports (including conference abstracts, dissertations, commentaries, etc.). These criteria eliminated 35 articles, leaving 89.

Finally, I conducted a full-article review, excluding even more articles. Throughout the full-article review, I pinpointed articles that researched specifically gentrification of color within a designated city or neighborhood in the United States between 1960 and 2021. Therefore, I removed studies that did not assess gentrification of color; only studies that described gentrification led by racial/ethnic members were included. These criteria eliminated 43 articles. All of these steps resulted in a universe of scientific studies of racial/ethnic gentrification written between 1960 and 2021 (n = 46; see ).

For the purposes of this research, the studies eventually included were the most important of all available studies on gentrification because they were the only peer-reviewed articles available on specifically racial/ethnic gentrification published in an American context within the time period in question. I then conducted a second full-article review during the data extraction process and defined themes according to the studies’ objectives and questions.

The methods I used in this study have certain limitations. One limitation of my sampling method is that I did not include studies on urban redevelopment or urban renewal that did not mention the term gentrification in the text, even if initiated by people of color, and therefore studies that may be relevant to the subject had to be dropped (for example, see Grogan & Proscio, Citation2000; Inwood, Citation2010; Lara, Citation2018).

Similarly, studies that defined specific urban processes as gentrification, regardless of displacement outcomes, were included in this review (for example, Black gentrification as defined by Moore, Citation2009). This review therefore encompasses a broad conceptualization of gentrification of color and encompasses various outcomes. This limitation is inherent to any conceptualization or review and, in a sense, justifies the existence of the review itself: the necessity to map and differentiate between different cases to advance and refine future research. In the findings section, I distinguish between displacing and nondisplacing gentrification of color, emphasizing the need for further examination of their differences.

Another limitation of this review is that its methodology was based on existing studies, making it difficult to provide extensive quantitative findings on displacement. Similarly, discerning whether certain policy-specific aspects were unique to gentrification of color or applied to White gentrification was challenging without a detailed description of the policies by the authors of the studies reviewed. Last, the methodology combined ethnicity and race in the analysis to advance a broader theory of gentrification of color. However, future studies should focus on distinguishing and comparing specific forms of gentrification, like Black gentrification and Latino gentrification, for a more nuanced understanding.

Despite these methodological limitations, reviewing studies in the field is crucial. It identifies research trends, offers comprehensive mapping and analysis, sharpens different phenomena and consequences, and promotes future research in the field of gentrification of color.

Results

Background: The Frequency and Research Interest in Gentrification of Color

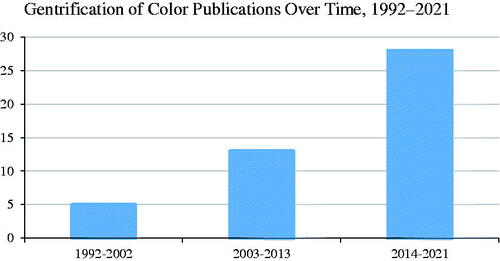

To present changes in the research interest regarding gentrification of color over time, I classified the 46 studies into three periods based on publication date: 1992–2002, 2003–2013, and 2014–2021 (). I divided periods corresponding to both shifts in gentrification and urban racial changes (Brown & Sharma, Citation2010; Florida & Mellander, Citation2015; Hackworth & Smith, Citation2001). This allowed me to identify the increase in studies on gentrification of color in U.S. cities over the years.

Studies on gentrification of color in Black communities specifically began about 30 years ago (Schaffer & Smith, Citation1986). Based on ethnographic research in Harlem, New York (NY), including in-depth interviews and field observations, Monique Taylor wrote on gentrification of color in 1992, examining how Black middle-class citizens were drawn to Harlem because of its representation as a symbol of Blackness. Since her research, there has been a gradual increase in publications on this phenomenon, though it is historically a poorly researched area (I found only 5 studies on the subject between 1992 and 2002 and 13 studies between 2003 and 2013). However, in the last decade there has been a significant increase in research (28 studies between 2014 and 2021; ).

This recent increase in publications on gentrification of color reflects a growing interest in the emergent trend unfolding across urban America: gentrification led by a variety of ethnic or racial actors, whom I describe as gentrifiers of color. In the past 3 decades, there has been significant growth in both Black and Latino middle-class populations (Grammenos, Citation2006; Hyra, Citation2008). Such growth, alongside the fact that neighborhoods with higher proportions of minorities were more likely to be gentrified by people of color (Hwang, Citation2015b), increases the importance of studying gentrification of color.

Analysis of Gentrification of Color: Population, Location, and Period of Time

My review revealed a diverse phenomenon that began as early as the mid-1970s in Harlem and has intensified in the last 2 decades. This phenomenon includes different gentrifiers of color and several key focal points on racial/ethnic composition.

First, the findings highlighted gentrifiers of various ethnic and racial backgrounds. The studies predominantly presented Black gentrifiers in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia (PA), and Washington (DC; 63%, n = 29 of total studies on Black gentrification) and Latinos in California and Chicago (15%, n = 7; also described as “Gentefication”; Berestein Rojas in Ahrens, Citation2015, p. 9, based on la gente, “the people” in Spanish).

Other gentrifiers have been Chinese, Bosnian, Korean, and Cuban (17%, n = 8) in different cities across the United States.Footnote1 They were mostly first-generation immigrants or refugees and managed to establish a middle class, developing their neighborhoods with businesspeople. This type can therefore be called immigrant gentrifiers. Finally, my analysis found seven studies (15%) that described more than one ethnic/racial group that led to gentrification in the same space, so I defined this type as mixed ethnic/racial gentrification. summarizes the analysis of gentrification of color by population, location, period, study method, and published author.

Table 1 Gentrification of color in the United States: Summary of literature.

Profiles of Gentrifiers of Color: Commercial, Artists, Developers, Residential, and Institutional

Gentrifiers of color represented not only diverse actors but also varying gentrification duration, nature of residence, activity, marital status, and more. The first profile of gentrifiers of color was commercial; that is, ethnic/racial entrepreneurs and business owners who promoted gentrification through establishing businesses. We can see this in the neighborhoods of Barrio Logan in San Diego (CA) and Boyle Heights in Los Angeles (CA). Young educated Latinx citizens who grew up in and outside of these neighborhoods started businesses there (Ahrens, Citation2015; Delgado & Swanson, Citation2021; Huante, Citation2021; Sandoval, Citation2021). In some of these cases, outside entrepreneurs displaced local entrepreneurs (Khare et al., Citation2015), but in most cases the ethnic/racial commercialization combined outside and local entrepreneurs, who managed to adapt to the business changes and even participate in them. In some cases, entrepreneurs of color were a major factor in driving neighborhood gentrification (Hom, Citation2022; Hume, Citation2015; Loukaitou-Sideris, Citation2002; Somashekhar, Citation2020).

Commercial gentrifiers of color sometimes partnered with artists, who played a central role in the aesthetics of gentrification (Lindner & Sandoval, Citation2021) and represented the second profile of ethnic gentrifiers. Artists have long been recognized as pioneers and catalysts of gentrification as they searched for cheaper rent and fruitful spaces for cultural production (Lloyd, Citation2010). Some ethnic artists purposefully committed to the area’s identity of place, expressing symbolic cultural capital and ethnic identity (Delgado & Swanson, Citation2021; Sandoval, Citation2021). They also branded neighborhoods in terms of distinctive cultural identities (Summers, Citation2021). For example, in El Barrio, New York City, artists used their craft to attract Puerto Ricans and Latinxs to serve as buffers to White gentrification (Dávila, Citation2004). Similarly, in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, Japanese American and Asian communities used art to empower community action, place identity, and urban development rather than cultural gentrification and outsider art (Crisman, Citation2021). Art in these cases was formed from a shared ethnic identity within art cafes, galleries, studios, murals, and graffiti on public spaces (Sandoval, Citation2021).

A third profile of gentrifiers of color is political elites, brokers, real estate developers, and real estate development firms from the same ethnic/racial groups. For example, the following Black real estate development firms have promoted gentrification in their areas: Ellis Development Group in Washington (DC); East Lake Management and Development in Chicago; and Full Spectrum (Hyra, Citation2008, Citation2012), community development corporations (CDCs), Abyssinian CDC, and the Harlem congregation’s community initiative in New York City (Freeman, Citation2006). Similar examples include Cuban gentrification in Miami (FL; Feldman & Jolivet, Citation2014), Black gentrification in Bronzeville, Chicago (Kim, Citation2022), and Chinese gentrification in Chinatown, Los Angeles (Lin, Citation2008). In cases where these real estate developers were also long-time residents of the neighborhood, they had a significant gentrification advantage because they were experienced in communicating with the national, regional, and local financial institutions. They were deeply engaged in local politics and well versed in local regulatory frameworks (Kim, Citation2022).

The fourth profile of gentrifiers is residential. Middle- and upper-class homeowners of color moved to ethnic/racial neighborhoods for numerous reasons, among them financial constraints, seeking a safe home free of racism (Prince, Citation2002; M. M. Taylor, Citation1992, Citation2002), a desire to revive ethnic/racial neighborhoods, promoting racial uplift, and creating a social buffer to gentrification (Boyd, Citation2005, Citation2008; M. M. Taylor, Citation2002). In some cases, they were unintentionally participating in gentrification, whereas in others they were purposefully gentrifying to attract external investment and resources (Anderson & Sternberg, Citation2013; Boyd, Citation2000, Citation2005; Helmuth, Citation2019; Hwang, Citation2020). These gentrifiers formed diverse groups including, among others, employees in the human and social services industry (J. Jackson, Citation2015; Moore, Citation2009; Prince, Citation2002). They also comprised younger, often single, and childless homebuyers from outside gentrified neighborhoods (Gibbons, Citation2021; Hyra, Citation2006, Citation2008; Pattillo, Citation2003, Citation2007; Sutton, Citation2020; Taplin-Kaguru, Citation2018; M. M. Taylor, Citation1992, Citation2002; Timberlake & Johns-Wolfe, Citation2017).

Finally, a fifth profile of gentrifiers of color is local religious or cultural organizations and institutions such as churches, museums, etc. For example, in Harlem, the famed Abyssinian Baptist Church has been a major housing developer (Hyra, Citation2008). Though usually local institutions and organizations whose prior affiliations, history, and specific identification with place are critical of gentrification, in some cases they promote it, whether out of an economic constraint (Sze, Citation2010) or out of perception and an agenda that sees gentrification as an opportunity for neighborhood development (Boyd, Citation2008; Chronopoulos, Citation2016; M. M. Taylor, Citation2002).

The Political and Economic Contexts of Gentrification of Color

During the 1930s and 1940s, ethnic/racial U.S. neighborhoods in inner cities became victims of discriminatory federal home appraisal practices. They were excluded from most Federal Housing Administration–insured loans due to the high risk of redlining or providing mortgages on homes in racially mixed neighborhoods. This together with White flight to the suburbs created segregation and a decline of ethnic/racial neighborhoods (Rothstein, Citation2017).

In the 1950s and 1960s, these ethnic enclaves received thousands of units of public housing that later, due to lack of maintenance, became centers of poverty and a burden on communities (Pattillo, Citation2007). Even after redlining’s end in the early 1970s, new policies within the racial economy continued to exclude minorities in housing (K. Y. Taylor, Citation2019; Wilson, Citation2009). These policies exacerbated residential racial segregation, disinvestment, and urban decay in the United States (Wilson, Citation2009) and laid the groundwork for gentrification and gentrification of color later (Freeman, Citation2006).

Following a period of sustained deterioration in inner-city neighborhoods and the simultaneous rise in potential ground rent levels, many American cities experienced the gentrification of select central-city neighborhoods (N. Smith, Citation1979). Studying Black gentrification in Chicago’s neighborhoods through ethnographic research, including participant observation, interviews (N = 20), and document analysis, Boyd (Citation2008) observed that in the 1970s, Black populations were more susceptible to becoming victims of White populations’ gentrification. At the same time, Black middle-class residents were significantly involved in gentrification because the race-based housing restrictions may have limited their living choices to gentrifiable neighborhoods, forcing them to live with lower-income Black populations. By the 1980s, however, stronger fair housing policies had expanded the Black middle class’s options, and they were increasingly drawn to more affluent areas, namely nongentrifiable neighborhoods (Bostic & Martin, Citation2003; Hyra, Citation2006).

Later, as inner-city real estate increased in value, these now-affluent Black residents returned to the poor Black neighborhoods they had vacated a decade before (Freeman, Citation2006; Hyra, Citation2006; Pattillo, Citation2007; Wilson & Grammenos, Citation2005; also described as a “rhetoric of return” by M. M. Taylor, Citation2002, p. xi). For some Black individuals, the move was motivated by what Sheryll Cashin called “integration exhaustion” (Cashin, cited in Pattillo, Citation2007, p. 10), the sociopsychological fatigue experienced especially by Black individuals who work in integrated environments or have been pioneers in White neighborhoods.

Based on 68 interviews with Black working-class to middle-class in Chicago, Taplin-Kaguru (Citation2018) argued that although most middle-class Black homebuyers wanted to live in a racially diverse and solidly middle-class neighborhood, the historical memory of White hostility and negative experiences in White neighborhoods limited their choices and led them to Black neighborhoods, where they acted as gentrifiers. Based on ethnographic research in Harlem, M. M. Taylor (Citation1992, Citation2002) found that for some gentrifiers of color, their neighborhood felt like a safe home free of racism. Thus, enclaves function as a protective factor not only for lower-income (Garcia-Hallett et al., Citation2020) but also for middle-and upper-class minorities against socio-structural hardship.

Another critical piece of context regarding gentrification of color—especially to the immigrant—is transnationalism. Whether supported by policy or acting as an expression of popular resistance of grassroots activities from below (P. M. Smith & Eduardo, Citation1998), immigration has laid the foundation for ethnic gentrification in many U.S. cities. Hwang (Citation2015a) suggested that the influx of immigrants following the passage of the 1965 Hart-Celler Act, which eased immigration restrictions, influenced gentrification’s development in different U.S. cities. These immigrants, predominantly Asian and Hispanic, settled in low-income, central neighborhoods such as Brooklyn’s Williamsburg, Manhattan’s Lower East Side, and Chicago’s Wicker Park, where they established commercial businesses.

Some of these neighborhoods eventually became established ethnic enclaves, spurring gentrification in the late 1970s and 1980s. For example, in Seattle (WA) neighborhoods, the legislative immigration reforms in 1965 led to a rapid increase in Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and Vietnamese populations, laying the foundations for gentrification later (Hwang, Citation2020). Similarly, in the late 1990s, new opportunities for investors from South Korea via the E-2 visa promoted the gentrification of Koreatown in Los Angeles (DeVerteuil et al., Citation2019). Finally, based on field observations and local media analysis in St. Louis (MO), Hume (Citation2015) indicated that a supportive immigration policy toward Bosnian refugees in the late 1990s, including a supportive city mayor and local officials championing Bosnian community-building efforts, contributed to the construction of Little Bosnia in St. Louis and its later gentrification (Hume, Citation2015).

Urban Redevelopment Policies Preceding Gentrification of Color

In the last 2 decades, studies have highlighted the state and city as key players in advancing gentrification. Gentrification is often part of a neoliberal urban policy that relies on markets and economic incentives to achieve goals such as strengthening the local government’s tax base, generating growth, and rehabilitating urban spaces (Lees et al., Citation2016). Institutional investors facilitate gentrification through pro-development regimes, including transit-oriented development and shifts in housing policies toward privatization. These target disadvantaged neighborhoods through means like public housing demolition and mixed-income developments (Goetz, Citation2011).

Similarly, my analysis revealed that gentrification of color was closely linked to urban policies encouraging neighborhood redevelopment and renewal. Six different redevelopment policies, sometimes combined with each other, were linked to gentrification of color (see ). Though these policy strategies were not unique to gentrification of color, some elements were unique to this type of gentrification, primarily cultural development policies and tax incentives intended for ethnic communities.

Table 2 Urban redevelopment policies preceding gentrification of color.

Commonly, gentrification of color emerged after or during policies promoting business and commercial development in the area. In some cases, this gentrification involved mixing business, industry, or commercial uses in housing as well as partnerships between the city, ethnic community organizations, corporations, real estate firms, and ethnic/racial developers and brokers. In Barrio Logan, San Diego, for example, urban planners promoted public investment to make the neighborhood more attractive to private investment in neighborhood revitalization. San Diego’s city hall and redevelopment agency conceptualized a request for proposal that has increased commercial development and higher-density housing within Barrio Logan (Delgado & Swanson, Citation2021; Sandoval, Citation2021).

In Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, the Wyvernwood Garden apartments’ planned conversion into the upscale residential New Wyvernwood primed the city for gentrification; the city also revitalized a nearby Sears property as a commercial and residential center (Ahrens, Citation2015; Huante, Citation2021). Similarly, public officials, developers, the City of Los Angeles, and the community redevelopment agency have repeatedly attempted renewal processes in Chinatown. The city provided $36 million in funding to establish Blossom Plaza, a mixed-use project including residential condominiums with both retail and commercial uses. In 2000, a property-based business improvement district was established, initiated by business leaders to encourage economic development through additional security, sanitation, and marketing services. The district was funded through tax assessments. In addition, in 2007, the community redevelopment agency approved a 5-story, mixed-used project called Chinatown Gateway that converted previously commercial spaces into luxury residential condominiums along with retail spaces (Hom, Citation2022; Lin, Citation2008).

In the cases of Huntington Park in Los Angeles and Valley Boulevard, San Gabriel, and Little Saigon in Orange County, ethnic gentrification resulted from a very conscious city council strategy to reposition certain areas as a center for ethnic economic activity (Loukaitou-Sideris, Citation2002). Similar policies occurred in North Kenwood–Oakland in Chicago (Pattillo, Citation2003), Brickton in Philadelphia (Moore, Citation2009), Little Havana in Miami (Feldman & Jolivet, Citation2014), Santa Ana’s downtown in Orange County (Sarmiento, Citation2022), and various neighborhoods in Washington (DC), Chicago, and New York City (Freeman, Citation2006; Hyra, Citation2008, Citation2012).

A second redevelopment policy linked to gentrification of color was tax policies. Tax-based redevelopment initiatives; tax increment financing; U.S. tax credit programs; tax benefits for real estate development, renovation, and development construction; a development block grant; a low-income tax credit; and incentives for first-time homebuyers all affect urban property development. The Empowerment Zones and Enterprise Communities initiative was an innovative federal policy in the 1990s to revitalize distressed communities. Providing tax credits for businesses and grants, this policy promoted Black gentrification in Bronzeville (Chicago), Harlem (New York), and Brooklyn (New York; Freeman, Citation2006; Hyra, Citation2008; M. M. Taylor, Citation2002), as well as Latinx gentrification in El Barrio/East Harlem (Dávila, Citation2004).

Harlem’s designation as a historic district made the area eligible for federal tax credits for rehabilitating historic buildings. This led to gentrification (Freeman, Citation2006). More recently, in Bronzeville, the Opportunity Zones policy, a federal policy offering capital gains tax benefits to spur economic development in distressed communities, made real estate the most attractive type of investment (Kim, Citation2022). In various Philadelphia neighborhoods, public–private partnerships and subsidies, the Community Development Block Grant, and the Low Income Tax Credit Program allowed housing refurbishment and new residential construction (Gibbons, Citation2021; Moore, Citation2009).

In Little Havana, the city provided incentives for middle-income, young Cuban Americans to move to Miami, purchase older historic homes, and renovate them. This would afford Miami an opportunity to facilitate an influx of middle-class families while generating more retail opportunities in Little Havana for local small businesses (Feldman & Jolivet, Citation2014). In Harlem, tax incentives and local housing plans encouraged central business district expansion and gentrification. Through quasi-governmental associations that required a levy from for-profit businesses in designated districts, the city used those funds to develop Harlem (Hyra, Citation2008).

Some of these public investments integrated with transit-oriented development (TOD), which represents a third policy strategy linked to gentrification of color. Hence, cities have been seeing an increase in TODs linked to mixed-use housing and development. For example, the public investments in expanding the metro system in DC attracted higher-income residents into DC neighborhoods, resulting in a dramatic rise in housing costs and a pattern of gentrification across the city (Helmuth, Citation2019). Similarly, in Los Angeles, gentrification began accelerating when the Gold Line Metro station opened. The accessibility of the neighborhood has not only attracted White gentrification but has also provided opportunities for Latino entrepreneurs, residents, and artists to participate in and benefit from the process of gentrification (Ahrens, Citation2015; Lin, Citation2008, Citation2021; Sandoval, Citation2021).

The fourth policy related to gentrification of color includes the demolition or rehabilitation of public housing to construct mixed-income residential buildings. This policy was implemented as part of the Federal Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE VI) program. As Goetz (Citation2011) described, in many cases, gentrifying neighborhoods have constituted older public housing that has suffered from decades of disinvestment and neglect. Demolishing such housing estates drives away significant proportions of impoverished communities and allows for housing stock and land more appealing to private-sector investment. In the United States, the centerpiece of state-led efforts to deconcentrate poverty and transform inner-city neighborhoods is the HOPE VI program. This program has been used in dozens of cities to demolish public housing and create new mixed-income communities in their place (Freeman, Citation2006; Hyra, Citation2008). The program thus redefined public housing policy and has served as the main vehicle through which the state has triggered inner-city revitalization.

The dismantling of public housing is not limited to HOPE VI projects, however. Chicago implemented the HOPE VI mission through its Plan for Transformation, with municipal support from the Chicago Office of Tourism and the Pilsen Together Chamber of Commerce, and later through the Pilsen Planning Committee (Anderson & Sternberg, Citation2013; Khare et al., Citation2015). In Oakland (Chicago), the city’s development policy from the 1990s included demolishing public housing apartments called the Lakefront Properties, which the Chicago Housing Authority built in the early 1960s (Pattillo, Citation2003). These urban policies represent the fifth policy strategy that promotes gentrification.

A final development policy strategy, unique to ethnic/racial neighborhoods, uses the neighborhood’s ethnic and cultural character as a tool for developing and attracting tourism and was described as cultural tourism (Loukaitou-Sideris & Soureli, Citation2012). In these cases, ethnic entrepreneurs, gentrifiers, and cultural architecture were significant policy components. In Pilsen, alongside the demolishing of public housing as part of the HOPE VI program, urban redevelopment was created through a revised and positively charged portrayal of the neighborhood and its inhabitants. Led by city policymakers, Pilsen was recodified as an authentic and vibrant Mexican ethnoscape, deployed to facilitate a form of tourist-oriented redevelopment (Anderson & Sternberg, Citation2013).

Similarly, Little Havana’s revitalization has been in the making since the early 1980s, when city officials issued plans to capitalize on the neighborhood’s Cuban flavor (Feldman & Jolivet, Citation2014). Similarly, in Manhattan’s Chinatown, public–private partnerships widely promoted the Chinese (residential) character of the neighborhood to encourage both gentrification and tourism (Sze, Citation2010). Finally, in recent years, government agencies and community organizations have put significant effort into rebuilding and rebranding H Street in Washington (DC) as a culturally diverse area, constructing art and entertainment districts with products simulating a global village (Summers, Citation2021).

The Implication of Gentrification of Color and the Efforts Made to Deal with Its Consequences

Although in many cases gentrification of color is linked to urban redevelopment policies, there has been a lack of attention given to policy questions concerning displacement and affordable housing. Specifically, there has been a lack of understanding regarding the existence of dedicated policies addressing issues such as 1) community-based intervention with an emphasis on intra-ethnic community relations, 2) policy efforts dealing with tensions between classes in the community, and 3) ensuring representation that is not only ethnically/racially descriptive but also class based in the centers of municipal decision making. The issue of representation is significant because, as I demonstrate in the next sections, ethnic gentrifiers have not necessarily upheld the interests of their lower-income counterparts, despite identifying with the same ethnic/racial community.

Some of the reasons for the lack of policy in relation to dealing with the social consequences of the phenomenon might be related to its complex consequences on displacement, intra-ethnic relations, and the complex attitudes of both the displaced ethnic/racial residents and the gentrifiers of color. The prevailing tendency of researchers has therefore been to focus on intra-ethnic relations and not on policies regarding the phenomenon.

Studies have tended to focus on the positions and activity of gentrifiers of color in relation to displacement, public housing, or affordable housing.Footnote2 Based on interviews, document analysis, and observations in several case studies, scholars reported that gentrifiers of color declared positive attitudes toward affordable housing and described specific activities ethnic gentrifiers engaged in to prevent displacement and promote affordable housing (Anderson & Sternberg, Citation2013; Dávila, Citation2004; Delgado & Swanson, Citation2021; Pattillo, Citation2007) However, studies have shown little evidence of an increase in affordable housing following gentrifiers of color’s involvement (Boyd, Citation2005; Moore, Citation2009; Sandoval, Citation2021).

Another complex and controversial research issue is the impact of gentrification of color on displacement (see Technical Appendix 1). Some findings have indicated that it differs from other forms of gentrification because it prevents displacement, acts as a buffer against White gentrification, and promotes affordable housing (Crisman, Citation2021; Moore, Citation2009; Sandoval, Citation2021; Sutton, Citation2020). Drawing from a 3-year ethnographic study in Philadelphia’s Brickton neighborhood, which involved 39 resident interviews and participant observations, Moore (Citation2009) posited that Black gentrification actively prevented the displacement of low-income neighbors while concurrently fostering increased class diversity within the neighborhood.

Similarly, Sandoval’s (Citation2021) analysis, which involved 70 interviews with stakeholders in Fruitvale, Boyle Heights, and Barrio Logan in California, identified Latino activists and gentrifiers of color, including Latino small business owners and entrepreneurs, as embodiments of ethnic representation that translated into a political agenda of redistribution and increased affordable housing.

These studies shed light on how gentrifiers of color can potentially prevent displacement. However, they also raise crucial questions: Why does displacement occur in certain cases but not in others? How can we generalize these findings to diverse scenarios? Last, how does gentrification of color differ from ethnic/racial-led urban revitalization/renewal when displacement is not present? I suggest that it might be related to the broader context of gentrification and displacement in the neighborhood, wherein gentrification of color can effectively serve as a buffer and preventive measure against displacement.

In contrast, based on qualitative studies involving participant interviews and observations, most scholars have argued that lower-income residents were indeed experiencing displacement from their communities (Ahrens, Citation2015; Anderson & Sternberg, Citation2013; Boyd, Citation2005, Citation2008; Chronopoulos, Citation2016; Dávila, Citation2004; Delgado & Swanson, Citation2021; DeVerteuil et al., Citation2019; Feldman & Jolivet, Citation2014; Huante, Citation2021; Hyra, Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2012; Khare et al., Citation2015; Kim, Citation2022; Lin, Citation2008; Pattilo, 2007; Prince, Citation2002; Sarmiento, Citation2022; Summers, Citation2021; Sze, Citation2010; M. M. Taylor, Citation1992, Citation2002; for quantitative study, see Goetz, Citation2011, and Technical Appendix 1).

Gentrifiers of color contributed to displacement by opposing affordable housing or public housing projects, promoting luxury construction, attracting external capital and tourism, and commercializing the neighborhood. Hyra’s (Citation2006, Citation2008) 4-year comparative ethnographic investigation on Black gentrification in Harlem and Bronzeville revealed that Black gentrifiers, using their racial and political power, advocated for community improvements while displacing lower-income residents and driving up property values.

Similarly, Ahrens (Citation2015) found in a qualitative study in Boyle Heights in Los Angeles that although Latinx gentrification could empower ethnic groups and raise the neighborhood’s social standing, it also can lead to lower-income Latinos’ displacement due to upscaling processes and increased reinvestment. Other studies indicated fears and pressures of displacement (Freeman, Citation2006; Gibbons, Citation2021; Khare et al., Citation2015) as well as cultural or symbolic displacement (Gibbons & Barton, Citation2016; Helmuth, Citation2019; Hom, Citation2022) resulting from gentrification of color.

Although these studies have made valuable contributions, there is some ambiguity in distinguishing between findings on direct and indirect displacement, as well as displacement pressures. Furthermore, there remains a gap in understanding how the actions of gentrifiers of color, who promote higher-income projects as both developers and customers, contribute to displacement in practice. Similarly, these findings raise questions about the extent to which displacement, as described by scholars, is directly linked to gentrification of color or if it stems from other forms of gentrification (such as White, commercial, or state-led gentrification) that often coexist within a neighborhood.

Last, it is crucial to note that most scholars have relied on qualitative data, primarily residents’ perceptions and statements, to draw their conclusions. This methodological limitation means that these findings might reflect concerns and pressures rather than concrete outcomes of displacement (as highlighted by Freeman, Citation2006). Therefore, further research is needed to measure the extent empirically and quantitatively to which low-income residents have been directly displaced because of gentrification of color.

Nevertheless, these findings highlight racial communities’ occasionally dissentious relationships, as well as the alienation and economic gaps occurring within the same ethnic/racial community. The inherent advantage is that differences and conflicting interests encourage group conflict by “position[ing] groups differently and relationally so that one group’s misfortune becomes another’s opportunity” (Kim, Citation2000, pp. 37–38). Alongside solidarity with lower-income ethnic residents, gentrifiers of color have frequently critiqued the behavior of the same residents as failing to adhere to acceptable cultural norms and having a ghetto mentality. They then negatively stereotype lower-income residents and attempt to control their behavior (Khare et al., Citation2015; Pattillo, Citation2007).

Residents and activists have also described this tension. Based on in-depth, semistructured interviews (N = 20) and ethnographic fieldwork in Boyle Heights, Huante (Citation2021) argued that residents perceived Latino gentrifiers as a betrayal of lower-income residents and immigrant solidarity, forming part of the larger threat of displacement rather than serving as a pathway to socioeconomic mobility.

Despite the importance of displacement, the studies analyzed tended to focus on the perceptions of gentrifiers of color, rarely addressing the attitudes and patterns of resistance among lower-income residents. Some studies described resistance and opposition attitudes or activism among lower-income residents in favor of affordable housing and working to prevent displacement (Ahrens, Citation2015; Hom, Citation2022; Huante, Citation2021; Hyra, Citation2008; Pattillo, Citation2003; M. M. Taylor, Citation2002). In general, these studies described activities to prevent displacement but did not clearly address lower-income residents’ resistance to the gentrifiers of color.

The few studies that have addressed the resistance of lower-income residents have revealed the dominance of organizations and grassroots housing advocacy to resist gentrification and call for affordable housing (Hyra, Citation2006; Kim, Citation2022). For example, in Los Angeles, Wyvernwood residents and supporters founded the group Save Wyvernwood to voice their concerns about mass tenant displacement following urban redevelopment (Ahrens, Citation2015). Similarly, in Chinatown, Los Angeles, a local organization called the Chinatown Community Advisory Committee worked for affordable housing (Hom, Citation2022). Pattillo (Citation2003) also described in detail protests and a lawsuit against the Chicago Housing Authority. Latino gentrification in San Diego also incited criticism and opposition from lower-income residents (Delgado & Swanson, Citation2021).

In general, the research has not identified whether lower-income residents were acting specifically against gentrifiers of color, seeing them as part of the gentrification process. As some studies have implied, because ethnic gentrifiers belong to the same community and some of them never left the neighborhood, they are viewed with less suspicion by lower-income residents. Low-income residents’ reluctance to oppose gentrifiers of color can be better understood when considering the criticism and internal policing they face from these gentrifiers (Boyd, Citation2008; Freeman, Citation2006; Patillo, Citation2003, Citation2007; M. M. Taylor, Citation1992, Citation2002).

Therefore, it is important to understand whether any resistance manifests differently or is unique to ethnic gentrification versus White gentrification. Not only does gentrification of color lead to the displacement of lower-income residents, but its long-term benefit for even gentrifiers of color is uncertain. Studies indicate displacement of gentrifiers of color or concern for such displacement in later stages of gentrification. This initial gentrification of color may have only opened the door to subsequent rounds of White-dominated gentrification (Lees, Citation2016). Therefore, gentrifiers of color have been described as early pioneers of gentrification (Hwang, Citation2015b, Citation2020), merely a stage of neighborhood change that precedes White gentrification (Somashekhar, Citation2020).

This process occurs because the neighborhood transition following gentrification of color often arouses the interest of White developers and local middle and upper classes. Such interest encourages city governments to provide incentives for economic development (Chronopoulos, Citation2016). Gentrification of color thus attracts large-scale reinvestment that both increases displacement pressure on low-income residents and invites interest in housing by other ethnicities (Ahrens, Citation2015). As a result, scholars have found that in gentrification’s second stage, as change extends across the city, middle-class Black and Latino residents are increasingly unable to remain in gentrifying neighborhoods and have become increasingly susceptible to displacement or voluntary relocation (Anderson & Sternberg, Citation2013; Pattillo, Citation2003; Sutton, Citation2020; M. M. Taylor, Citation1992, Citation2002). Even when such displacement has yet to occur, gentrifiers of color express concerns about housing affordability (Hyra, Citation2006; Lin, Citation2008; Patillo, 2003, 2007).

To conclude, studies indicate the complex social consequences of gentrification of color, particularly regarding the displacement of both the lower-income residents and gentrifiers, tensions that arise between different classes, and the objection of some gentrifiers of color to affordable housing, as well as the less-suspicious feelings and opposition from the lower-income residents to gentrifiers belonging to the same community. All of these complex consequences divert the scholarly attention from engaging in policy and its responsibility in dealing with the social consequences of gentrification, and reveal the unique complexities and challenges of gentrification of color and the importance of future research on these issues.

Conclusions

Although the dominant stream of urban studies research has linked ethnic/racial and class-based marginalization resulting from gentrification, this review has identified cases where class and ethnic affiliations exhibit contradictions. Gentrification of color shows that gentrification may both mobilize and marginalize some but not others in the minority racial or ethnic group, depending on their class affiliation. This study has both theoretical and practical contributions to urban planners, policymakers, and scholars.

Theoretical Contribution and a Call for Further Research

In this review I have presented a comprehensive analysis of the phenomenon of gentrification of color, encompassing its locations, actors, the policies linked to its occurrence, and its consequences. I found that there is an increase in research on gentrification of color, focusing on a few cities in the United States. The phenomenon appears not only in Black and Latinx communities, which are the more familiar cases, but as gentrification of color among other ethnic, immigrant, and minority U.S. communities. Analyzing the literature also suggested different profiles of gentrifiers of color: commercial, artist, developer, residential, and institutional. These studies identify both solidarity and tensions between different classes within the same ethnic/racial groups as the consequence of gentrification.

In particular, the findings shed light on the planning and policy processes that are linked to its occurrence. Gentrification of color, much like other forms of gentrification, is connected to a capitalist housing regime, which intensifies competition for housing affordability and resources among different classes within communities of color. Therefore, addressing these issues is fundamentally a matter of policy and planning.

The phenomenon’s relevance and increasing interest by researchers emphasize the importance of more deeply examining the complex intersection of race and class in gentrification processes and their yet-unfamiliar social implications. There is a lack of empirical research comparing the social consequences of gentrification of color’s differing profiles; for example, Black versus Latinx or residential versus commercial gentrification. Another understudied area is gentrification of color that displaces a White majority. As cities become more diverse, gentrification involves more diverse groups, requiring the investigation of multiple scenarios.

Similarly, it is important to expand the research on gentrification of color beyond the Global North. The studies of Sakızlıoğlu and Lees (Citation2020) on commercial gentrification led by ethnic minority entrepreneurs in Indische Buurt (Amsterdam), of Arkaraprasertkul (Citation2016) on “gentrification from within” (p. 6) in Shanghai, and my previous research (Shmaryahu-Yeshurun, Citation2022) on “minority gentrification” by Arab entrepreneurs in Old Acre (Israel) constitute a starting point for an empirical study of phenomena outside the United States.

Finally, I encourage researchers to explore gentrification of color from a planning and policy angle and propose effective solutions to displacement and community unrest. As I found, gentrification of color is very much linked to urban policies that encourage neighborhood redevelopment. These include business, commercial, and residential urban redevelopment policies; tax policies; TOD; federally led demolition or rehabilitation of public housing; municipally led demolition or rehabilitation of public housing; and cultural tourism policy. Sometimes gentrification policies are intensified in ethnic neighborhoods precisely because of the culture and art offered to tourists (i.e., a cultural tourism policy). However, there is a lack of empirical research that specifically examines how these policies have contributed to gentrification of color, as opposed to White gentrification.

Similarly, only a few studies addressed the policy efforts to deal with the social consequences of the phenomenon. More research is needed to also quantify the displacement caused by gentrification of color, differentiate between direct and indirect displacement, and measure displacement pressure. In addition, distinguishing between gentrification of color that leads to displacement and those that do not, along with providing explanations for these differences, requires further investigation. Further research is required to address these gaps in knowledge.

The lack of research on planning and policy related to gentrification of color is particularly glaring considering recent research trends that have positioned city and state policymakers as key players in the urban process (Lees et al., Citation2016). Though researchers describe diverse policies to promote affordable housing and cope with displacement resulting from gentrification, such policies in the case of gentrification of color have not yet been addressed. As I suggested, the complex consequences of the phenomenon on the displacement of both lower-income ethnic/racial residents and gentrifiers, and on forming intra-ethnic tensions, leads to our tendency to focus on intra-ethnic issues and debates and, as a result, to neglect the policies and planning aspects.

The lack of research on planning and policy related to the social consequences of gentrification of color may also be due to the assumption that there is communal solidarity between classes in the same ethnic/racial communities and that racial elites care for their disadvantaged populations, thus empowering the entire community and providing racial uplift (Boyd, Citation2008; Huante, Citation2021; Moore, Citation2009). Whereas minority Americans and, in particular, those living in mostly Black neighborhoods are more likely than Whites to see political activities as a way to care for their community and help people in need (Anoll, Citation2018), this is not always the case. Lacking the planning perspective, the literature diverts our attention from the policy responsibility to deal with the consequences caused by planning activities. This may unintentionally contribute to the perception that this is an internal and local problem of the ethnic/racial community and that the responsibility or even the blame lies with the gentrifiers of color.

Therefore, it is essential to research an approach to planning and policymaking that will foster harmony and fair urban planning, considering both class and race in gentrification of color. On the one hand, such an approach should avoid examining only racial displacement and thus overlooking class displacement. On the other hand, new policies should emphasize that displacement in ethnic neighborhoods manifests differently from White gentrification in its class repression and intra-racial characteristics.

A Practical Contribution to Urban Policy and Planning

Gentrification of color demands further consideration of the intersectionality of race and class when making urban planning interventions. Analyzing gentrification of color may inspire urban planners and policymakers to mobilize and partner with ethnic gentrifiers to promote urban development that is culturally inclusive, empower the cultural identity of the space, and use ethnic communities’ historical and cultural assets to promote affordable housing (Boyd, Citation2005, Citation2008; Crisman, Citation2021; Moore, Citation2009; Sandoval, Citation2021; M. M. Taylor, Citation2002). Despite their economic status and disparate interests, gentrifiers of color often declare solidarity with and a desire to prevent the displacement of lower-income residents. In many cases they move to the neighborhood with a sense of racial pride and duty, acting as conduits of resources, role models, or social buffers from White gentrification. They wish to promote racial uplift, protect the culture, and promote affordable housing.

Urban planners can learn from cases of Latinx gentrification where gentrifiers used cultural and ethnic symbols as political capital, empowering lower-income residents with more control over the gentrification process. In these cases, Latinx gentrifiers increased affordable housing, provided access to more social services, improved public spaces, and linked regional public transportation systems (Sandoval, Citation2021). Similarly, urban planners can learn from the case of gentrification in Little Tokyo (CA). Community organizations, artists, and business owners pooled resources and used art in a grassroots movement to increase a sense of belonging and Japanese American and Asian American placemaking, which was the antithesis of cultural gentrification (Crisman, Citation2021).

Urban planners can also learn from cases of Black gentrification in which Black gentrifiers integrated into local organizations and worked for affordable housing. Boyd (Citation2008) described how Black elites adopted “defensive development” (p. 752): community building and economic revitalization designed to protect their neighborhoods from White residents, city elites, and developers. Black organizations attempted to link the interests of low- and middle-income residents by highlighting their common economic concerns. They used tourism as an economic driver for both lower- and middle-class Black residents. Though tourism would encourage small business development among the community’s middle-income residents, they urged these businesses to serve and provide local employment for the neighborhood’s poorer residents.

Similarly, Brickton in Philadelphia became a class-integrated neighborhood; attracting middle-class residents through housing development has not prevented an emphasis on homeownership and rental housing for low-income families. Many middle-class residents have worked through community-based organizations and housing developers to limit displacement, ensure relatively low housing prices, and promote homeownership among Brickton’s current residents (Moore, Citation2009).

At the same time, it is important for urban planners and policymakers to consider that ethnic gentrifiers do not necessarily uphold the interest of their lower-class counterparts. As demonstrated, some ethnic gentrifiers see their communities as bearing enough of the public housing burden and other spatial injustices. They therefore promote the neighborhood’s uplift and redevelopment even at the expense of lower-income residents.

This analysis calls on urban planners to pay extra attention to social relations and the suppression of the poor in neighborhoods where intra-ethnic tensions, possible hierarchies, and inequality within the minority community are masked under the guise of ethnic unity. Intra-ethnic tensions may also be hidden due to internal policing and gentrifiers’ silencing of lower-income residents. To complicate the issue, gentrifiers of color present themselves as community representatives, backed by the fact that indeed some of them have never left the neighborhood (Freeman, Citation2006). Therefore, it is critical that planners ensure not only ethnic/racial representation but also class representation in urban decision-making processes, even in neighborhoods where there seems to be ethnic solidarity.

By recognizing the intricate intersection between class, ethnicity/race, and the crucial role of policy and planning in gentrification processes, urban planners and scholars can adopt more holistic and inclusive approaches to tackle the social and economic consequences of gentrification. This comprehensive perspective enables the development of strategies that promote equity, cultural preservation, and economic opportunity for the benefit of all individuals involved.

Research Support

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 101025665.

Technical Appendix

Download PDF (230.9 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Professor Gershon Shafir of the Sociology Department at the University of California, San Diego, and Professor Avner de-Shalit of the Political Science Department at the Hebrew University for their helpful comments and suggestions. I also thank the Editor, Dr. Ann Forsyth, and the anonymous reviewers for their generous and constructive feedback.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2023.2251981

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yael Shmaryahu-Yeshurun

YAEL SHMARYAHU-YESHURUN ([email protected]) is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, San Diego.

Notes

1 Few studies have focused on more than one ethnic/racial group, so the total percentage of the populations came out to more than 100%.

2 The rest of the studies analyzed did not address this issue.

References

- Ahrens, M. (2015). “Gentrify? No! Gentefy? Sí!” Urban redevelopment and ethnic gentrification in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles. Aspeers: Emerging Voices in American Studies, 8, 9–26. https://doi.org/10.54465/aspeers.08-03

- Anderson, M. B., & Sternberg, C. (2013). “Non-White” gentrification in Chicago’s Bronzeville and Pilsen: Racial economy and the intraurban contingency of urban redevelopment. Urban Affairs Review, 49(3), 435–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087412465590

- Anoll, A. P. (2018). What makes a good neighbor? Race, place, and norms of political participation. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 494–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000175

- Arena, J. (2012). Driven from New Orleans: How nonprofits betray public housing and promote privatization. University of Minnesota Press.

- Arkaraprasertkul, N. (2016). Gentrification from within: Urban social change as anthropological process. Asian Anthropology, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1683478X.2016.1158227

- Blum, A., & Guérin-Pace, F. (2008). From measuring integration to fighting discrimination: The illusion of “ethnic statistics.” French Politics, Culture & Society, 26(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.3167/fpcs.2008.260104

- Bostic, R. W., & Martin, R. W. (2003). Black home-owners as a gentrifying force? Neighbourhood dynamics in the context of minority home-ownership. Urban Studies, 40(12), 2427–2449. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000136147

- Boyd, M. (2000). Reconstructing Bronzeville: Racial nostalgia and neighbourhood redevelopment. Journal of Urban Affairs, 22(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2166.00045

- Boyd, M. (2005). The downside of racial uplift: The meaning of gentrification in an African American neighborhood. City & Society, 17(2), 265–288. https://doi.org/10.1525/city.2005.17.2.265

- Boyd, M. (2008). Defensive development: The role of racial conflict in gentrification. Urban Affairs Review, 43(6), 751–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087407313581

- Brown, L. A., & Sharma, M. (2010). Metropolitan context and racial/ethnic intermixing in residential space: U.S. metropolitan statistical areas, 1990–2001. Urban Geography, 31(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.31.1.1

- Chronopoulos, T. (2016). African Americans, gentrification, and neoliberal urbanization: The case of Fort Greene, Brooklyn. Journal of African American Studies, 20(3-4), 294–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-016-9332-6

- Crisman, J. (2021). Art and the aesthetics of cultural gentrification: The cases of Boyle Heights and Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. In C. Lindner & G. Sandoval (Eds.), Aesthetics of gentrification: Seductive spaces and exclusive communities in the neoliberal city (pp. 137–154). Amsterdam University Press.

- Dávila, A. (2004). Barrio dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and the neoliberal city. University of California Press.

- Delgado, E., & Swanson, K. (2021). Gentefication in the barrio: Displacement and urban change in Southern California. Journal of Urban Affairs, 43(7), 925–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1680245

- DeVerteuil, G., Yun, O., & Choi, C. (2019). Between the cosmopolitan and the parochial: The immigrant gentrifier in Koreatown, Los Angeles. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1347955

- Feldman, M., & Jolivet, F. (2014). Back to Little Havana: Controlling gentrification in the heart of Cuban Miami. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1266–1285. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12097

- Florida, R., & Mellander, C. (2015). Segregated city: The geography of economic segregation in America’s metros. Martin Prosperity Institute.

- Freeman, L. (2006). There goes the hood: Views of gentrification from the ground up. Temple University Press.

- Garcia-Hallett, J., Like, T., Torres, T., & Irazábal, C. (2020). Latinxs in the Kansas City Metro Area: Policing and criminalization in ethnic enclaves. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 40(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19882749

- Gibbons, J. (2021). Measuring gentrification’s association with perceived housing unaffordability: A Philadelphia case study. Housing Policy Debate, 31(2), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1810097

- Gibbons, J., M., & Barton, S. (2016). The association of minority self-rated health with Black versus White gentrification. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 93(6), 909–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0087-0

- Gibbons, J., Barton, M. S., & Reling, T. T. (2020). Do gentrifying neighbourhoods have less community? Evidence from Philadelphia. Urban Studies, 57(6), 1143–1163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019829331

- Goetz, E. (2011). Gentrification in Black and White: The racial impact of public housing demolition in American cities. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 48(8), 1581–1604. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010375323

- Grammenos, D. (2006). Latino Chicago. In R. Greene, M. Bauman, and D. Grammenos (Eds.), Chicago’s geographies: Metropolis for the 21st century (pp. 205–216). Association of American Geographers.

- Grogan, P. S., & Proscio, T. (2000). Comeback cities. A blueprint for urban neighborhood revival. Basic Books.

- Hackworth, J., & Smith, N. (2001). The changing state of gentrification. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 92(4), 464–477.

- Helmuth, A. S. (2019). “Chocolate City, rest in peace”: White space-claiming and the exclusion of Black people in Washington, DC. City & Community, 18(3), 746–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12428

- Hom, L. D. (2022). Symbols of gentrification? Narrating displacement in Los Angeles Chinatown. Urban Affairs Review, 58(1), 196–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087420954917

- Huante, A. (2021). A lighter shade of brown? Racial formation and gentrification in Latino Los Angeles. Social Problems, 68(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spz047

- Hume, S. E. (2015). Two decades of Bosnian place-making in St. Louis, Missouri. Journal of Cultural Geography, 32(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2015.1005880

- Hwang, J. (2015a). Gentrification in changing cities: Immigration, new diversity, and racial inequality in neighborhood renewal. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 660(1), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215579823

- Hwang, J. (2015b). Pioneers of gentrification: Transformation in global neighborhoods in urban America in the late twentieth century. Demography, 53(1), 189–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0448-4

- Hwang, J. (2020). Gentrification without segregation? Race, immigration, and renewal in a diversifying city. City & Community, 19(3), 538–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12419

- Hwang, J., & Sampson, R. J. (2014). Divergent pathways of gentrification: Racial inequality and the social order of renewal in Chicago neighborhoods. American Sociological Review, 79(4), 726–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414535774

- Hyra, D. S. (2006). Racial uplift? Intra‐racial class conflict and the economic revitalization of Harlem and Bronzeville. City & Community, 5(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2006.00156.x

- Hyra, D. S. (2008). The new urban renewal: The economic transformation of Harlem and Bronzeville. University of Chicago Press.

- Hyra, D. S. (2012). Conceptualizing the new urban renewal: Comparing the past to the present. Urban Affairs Review, 48(4), 498–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411434905

- Inwood, F. J. (2010). Sweet Auburn: Constructing Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue as a heritage tourist destination. Urban Geography, 31(5), 573–594. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.31.5.573

- Jackson, J. (2015). The consequences of gentrification for racial change in Washington, DC. Housing Policy Debate, 25(2), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2014.921221

- Kent‐Stoll, P. (2020). The racial and colonial dimensions of gentrification. Sociology Compass, 14(12), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12838

- Khare, A. T. M., Joseph, L., & Chaskin, R. J. (2015). The enduring significance of race in mixed-income developments. Urban Affairs Review, 51(4), 474–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087414537608

- Kim, C. (2000). Bitter fruit: The politics of Black-Korean conflict in New York City. Yale University Press.

- Kim, M. (2022). How do tax-based revitalisation policies affect urban property development? Evidence from Bronzeville, Chicago. Urban Studies, 59(5), 1031–1047. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098021995148

- Kipfer, S., & Petrunia, J. (2009). “Recolonization” and public housing: A Toronto case study. Studies in Political Economy, 83(1), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/19187033.2009.11675058

- Lara, J. J. (2018). Latino placemaking and planning: Cultural resilience and strategies for reurbanization. University of Arizona Press.

- Lees, L. (2016). Gentrification, race, and ethnicity: Towards a global research agenda? City & Community, 15(3), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12185

- Lees, L., Shin, H. B., & López-Morales, E. (2016). Planetary gentrification. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lin, J. C. (2021). Hipster aesthetics and anti-gentrification struggles in Los Angeles. In C. Lindner & G. Sandoval (Eds.), Aesthetics of gentrification: Seductive spaces and exclusive communities in the neoliberal city (pp. 199–220). Amsterdam University Press.

- Lin, J. C. (2008). Los Angeles Chinatown: Tourism, gentrification, and the rise of an ethnic growth machine. Amerasia Journal, 34(3), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.17953/amer.34.3.v545v63lpj1535p7

- Lindner, C., & Sandoval, G. (2021). Aesthetics of gentrification: Seductive spaces and exclusive communities in the neoliberal city. Amsterdam University Press.

- Lloyd, R. (2010). Neo-bohemia: Art and commerce in the postindustrial city. Routledge.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2002). Regeneration of urban commercial strips: Ethnicity and space in three Los Angeles neighborhoods. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 19(4), 334–350.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., & Soureli, K. (2012). Cultural tourism as an economic development strategy for ethnic neighborhoods. Economic Development Quarterly, 26(1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242411422902

- Melamed, J. (2015). Racial capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies, 1(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.5749/jcritethnstud.1.1.0076

- Mele, C. (2017). Race and the politics of deception: The making of an American city. New York University Press.

- Moore, K. S. (2009). Gentrification in Black face? The return of the Black middle class to urban neighborhoods. Urban Geography, 30(2), 118–142. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.30.2.118

- Mumm, J., & Sternberg, C. (2022). Mapping racial capital: Gentrification, race and value in three Chicago neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review, 59(3), 435–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087422108261

- Pattillo, M. (2003). Negotiating Blackness, for richer or for poorer. Ethnography, 4(1), 61–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138103004001004

- Pattillo, M. (2007). Black on the block: The politics of race and class in the city. University of Chicago Press.

- Prince, S. R. (2002). Changing places: Race, class, and belonging in the new Harlem. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development, B. Williams and S. Prince (Eds.), 31(1), 5–35.

- Robinson, C. (2000). Black Marxism: The making of the Black radical tradition. University of North Carolina Press.