Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

Planning under uncertainty and planning for racial equity both require imagination. In confronting the uncertain future, regional planners often opt for exploratory scenario planning: telling multiple future stories to prepare for any outcome. For equity planning, imagination supports vision beyond the deeply unequal present condition, wherein policy tinkering is insufficient for necessary change. And yet, scenario planning and equity planning are estranged. Although regional planners wish to engage both, they lack guidance on how. I look to close this gap by providing a framework (the Framework) for using scenarios in equity planning. The Framework builds on the five types of racial equity, a six-stage hybrid scenario process, and the three outcomes of public-sector scenarios. Using the Framework, I assessed the inclusion of equity in the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s Dispatches From Alternative Futures scenario plan. This plan successfully raises racial equity as a concern for the future of the Philadelphia (PA) region. However, the stakeholder group was not sufficiently diverse for deliberative equity and the scenario planners did not use tools that could assess the distributional outcomes. Neither epistemic nor restorative equity were a significant part of the scenario plan, leaving open the possibility for co-designed scenarios for a racial equity future.

Takeaway for practice

Metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) can use the Framework to ensure that exploratory scenarios advance equity goals. Although the Framework can supply a starting point for MPOs, the most important voices are those from Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) and other marginalized communities. Scenario planners should consider how they can reach out to community members not just as stakeholders but as co-creators of a more epistemically equitable scenario planning process, one that addresses the uncertainties and aspirations that already percolate within these communities.

The inclusion and focus on equity in the Dispatches scenarios came from the Futures Group participants. Staff here struggled with how to tell stories about and understand the implications of more or less equitable futures. [Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission planner]

In confronting the uncertain future, regional planners often opt for exploratory scenario planning: telling multiple future stories to prepare for any outcome (Avin, Citation2007). For equity planning, scenarios could support vision beyond the unequal present condition, wherein policy tinkering is insufficient. And yet, scenario planning and equity planning have been estranged. The uncertainties that scenarios seek to address often seem irrelevant to the day-to-day certainties of marginalization experienced by racialized communities (Zapata, Citation2021). Moreover, regional planning has contributed to the production of racialized space (Williams, Citation2024). Although regional planners wish to engage both, they lack guidance on how. In this study, I sought to close this gap by providing a framework for using regional scenarios in equity planning (the Framework).

Racial equity planning explicitly sets clear equity goals and pursues policies and programs to achieve more equitable outcomes. I specifically examine metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), federally mandated regional transportation planning bodies, which have increased equity planning in recent years. MPOs are setting ambitious equity goals (Martens & Golub, Citation2021) but still lack equity-planning competencies (Zapata & Bates, Citation2017). In critically examining the history of planning, this is unsurprising. Public action and inaction have supported the implicit norm of producing racialized spaces that support racial dispossession and exploitation (Mills, Citation2008; Williams, Citation2024; Yiftachel, Citation1998). If scenario planners are serious about confronting these legacies, they must embrace approaches that examine racial inequities through scenario development.

Many systems driving racial inequity are regional, such as transportation networks and housing markets. Regional scenario planning’s focus on key regional trends could be well directed toward collectively understanding the root causes of unequal access, segregation, and other manifestations of structural racism. Having these conversations within the MPO would inform regional decision makers on how these inequitable forces affect everyone’s lives.

Here I address exploratory scenarios, which examine external forces to tell several unlike future stories (Goodspeed, Citation2020). Through these stories, stakeholders explore possibilities and prepare for whatever comes. The approach is exploratory in that it is oriented toward exploring driving forces, uncertainties, and plausible outcomes rather than designing desired futures (Avin, Citation2007). However, exploratory scenarios need to adopt a hybrid approach that accounts for community values (Bezold, Citation2009). For readability, I use scenarios except when more precision is needed.

I demonstrate the Framework by applying it to the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s (DVRPC’s) Dispatches From Alternative Futures (Dispatches) scenarios. I used the Framework to uncover how DVRPC was already promoting racial equity through Dispatches and what they can do additionally. In the following section, I introduce the literature. The next two sections develop the Framework and apply it to Dispatches. Finally, I summarize what the case illustrates about promoting racial equity through scenario planning and then draw conclusions.

Literature Review

Scenario Planning and Its Purpose

Scenario planning is “long-term strategic planning that creates representations of multiple, plausible futures of a system of interest” (Goodspeed, Citation2020, p. 21). Exploratory scenarios ask, “What could happen?” To answer that question, stakeholders craft multiple future stories driven by external uncertainties. Exploratory scenarios require plausible, coherent, and compelling storytelling (Goodspeed, Citation2020). Hybrid approaches combine normative ambition with exploration of uncertain forces (Bezold, Citation2009).

Public-sector scenarios aim toward three outcomes: stakeholder learning, strategic guidance, and community learning. For stakeholder learning, collective deliberation over driving forces and scenarios alerts stakeholders to underlying dynamics and pathways for change (Schwartz, Citation1991). In theory, stakeholders are then more open to the change and prepared to adapt (Zegras & Rayle, Citation2012). Strategic guidance refers to testing policy options through the scenarios to find robust strategies (those that work in all circumstances) and contingent strategies (those that are effective in specific conditions; Zegras et al., Citation2004). Scenarios can also support community learning about the regional dynamics through public meetings and media (Goodspeed, Citation2020).

Regional organizations have embraced scenarios because they have limited powers relative to other levels of government and are thus aware of how much forces outside of their control impact whether they achieve their policy goals (Sherman & Chakraborty, Citation2022). Federal guidance for MPO long-range plans encourages scenario development (Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act, Citation2012), and the Federal Highway Administration has produced multiple guidebooks (Bauer et al., Citation2015; Twaddell et al., Citation2016).

Racial Equity Planning

Here I use racial equity to refer to accounting for racial difference and working to remove barriers to more equal distribution of goods and opportunities (Karner et al., Citation2020). In equity planning, government institutions explicitly prioritize equity, set clear equity goals, and pursue policies and programs to achieve more equitable outcomes (Krumholz, Citation1982; Zapata & Bates, Citation2017). Racial equity planning maintains power positions, whereas justice-oriented movements seek to transform social and political systems so that the distribution of goods and opportunities is inherently more equal and power is shared more broadly (Karner et al., Citation2020).

Williams (Citation2024) provided theoretical grounding for equity planning and argued for reparative planning. Up to now, equity planning—and planning more generally—has failed to recognize the normative acceptance of White supremacy in North American liberal democracies. I use White supremacy here to refer to the sociopolitical system that solidifies racial hierarchies (Fredrickson, 1982). Yiftachel (Citation1998) uncovered how planning is often used as an apparatus of oppressive control, but Williams went further in establishing the dominant racial dimensions. Building on theories of racial capitalism (Fraser, Citation2016) and racial liberalism (Mills, Citation2008), Williams demonstrated how planning supported spatial difference among races and argued that planning should be reparative, in that it addresses previous harm. The above arguments highlight the importance of professional frameworks for racial equity and reparations.

Despite the normative blind spots, several decades of equity planning have provided concrete recommendations that apply to scenario planning. Equity planners should be clear that they are not neutral concerning promoting greater equity and should set clear, measurable objectives (Krumholz, Citation1982). Racial equity planners should remain attuned to topics that matter to communities of color, establish a shared vision, develop appropriate technical tools, and consider governance strategies (Zapata & Kaza, Citation2015). Both process and outcomes should be equitable (Metzger, Citation1996). Planning departments should review equity in their internal practices (Solis, Citation2020).

The Unrealized Values in Using Scenarios for Racial Equity Planning

Equity planners have generally focused their work on the municipal scale. Many center cities, such as Cleveland (OH), under planning director Norman Krumholz, pushed for equity planning in the second half of the 20th century. Increasingly non-White populations have elected mayors who have pushed for more consideration of race and class in planning and policy (Clavel, Citation1994; Metzger, Citation1996). Despite initial resistance, many suburban jurisdictions have embraced equity-planning policies as their populations have diversified (Kneebone & Holmes, Citation2015). MPOs have historically oriented transportation investments toward economic growth with limited equity consideration, as outlined in federal Title IX and environmental justice requirements (Martens & Golub, Citation2021).

Scholars have argued that regions are essential for addressing equity because they are scaled to address problems that transcend municipal borders (Pastor et al., Citation2011). Others have been concerned that regionalizing equity issues only serves to moderate progressive urban concerns with Whiter, wealthier voices (Imbroscio, Citation2006). Nonetheless, MPOs are increasingly interested in more fairly distributing the benefits of transportation investments. Black Lives Matter protests and other movements have awakened the profession to the ongoing legacies of racialization and oppression. This commitment is clear in recent MPO equity standards that go beyond federal requirements (Martens & Golub, Citation2021).

Racial equity planning can strengthen scenario planning by broadening scenario insights. Although some authors have emphasized stakeholder values (Avin, Citation2007), most scenario plans have been technocratic, expert-driven exercises (Zapata & Kaza, Citation2015). We can expect that such plans would reflect professional values (Goetz et al., Citation2020). Incorporating stakeholders from marginalized communities will expand the range of scenarios. Scenarios developed with BIPOCFootnote1 communities may highlight forces implicated in structural racism. Scenario stories can then aid in understanding the consequences of inequities for those directly affected and the broader community. Plans for racial equity planning and justice need a more expansive imagination than is currently present (Inch, Citation2021; Zapata, Citation2021). In examining multiple futures, scenarios remind communities that the future is not doomed to reproduce the inequitable present.

The Current State of Equity in Scenario Planning

Federal regulations require MPO equity analysis for planned transportation investments as guided by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ensures the fair distribution of benefits to marginalized populations, and environmental justice guidelines stemming from Executive Order 12898, which protects against disproportionate harms. These regulations apply to both planning processes and products (Martens & Golub, Citation2021). MPOs must meet these minimum requirements but are also welcome to exceed them. MPO equity compliance documentation has focused on the long-range plan process and projected project impacts. To my knowledge, no MPO equity analysis includes scenarios.

Avin (Citation2007) argued that scenario planning requires parallel trend-analytic and goals-oriented processes, or a “hybrid” (Bezold, Citation2009) approach. Values ground scenarios in community concerns and improve scenario relevance (Avin & Goodspeed, Citation2020). In this vision, stakeholders draft scenarios from combining possible and preferred futures.

Prioritizing equity places several additional demands on scenario planning. First, equity planning requires identifying target populations, setting normative principles, and determining specific actions (Zapata & Bates, Citation2017). Second, equity is cross-cutting and requires setting distributional goals (Bills & Walker, Citation2017). Finally, racial equity planning must deeply engage BIPOC populations and procedures to elevate BIPOC voices (Bartholomew, Citation2007; Zapata & Kaza, Citation2015).

The literature on equity in scenarios is sparse. Avin et al. (Citation2014) argued that the analytic techniques in scenario plans do not produce useful equity measures. They promoted opportunity mapping for spatializing equity impacts. Bauer et al. (Citation2015) suggested advancing equity through specific goals, objectives, and performance measures in widely representative stakeholder processes. In Scenario Planning for Cities and Regions, Goodspeed examined the potential for transformative practices (2020). Although scenarios could lead to more equitable results, this potential has rarely been realized. To achieve more equitable outcomes, scenario planning needs to imagine emancipatory futures by genuinely empowering BIPOC and other marginalized communities.

Finally, Ayambire & Moos (Citation2024) systematically reviewed social equity in the scenario planning literature. The authors confirmed the lack of equity and suggested exploring multiple futures with different social equity outcomes. Aside from these studies, suggestions for using scenarios to promote racial equity have been scattered across publications focused on other concerns. Here, I weave those pieces together into a coherent framework.

A Framework for the Use of Scenarios in Racial Equity Planning

Methods for Developing the Framework

I considered all articles on public-sector scenario planning in the Journal of the American Planning Association, the Journal of Planning Education and Research, Planning Theory and Practice, Planning Theory, the Environment and Planning journals, Transport Reviews, and the Transportation Research journals. From those journals and through Google Scholar searches, I compiled articles that discussed scenario planning methods. In addition to an initial reading, I searched (using the Find function) each article for equity words and topics. I looked for equity topics broadly instead of just racial equity because some of the suggested approaches may also be applicable for racial equity planning. I supplemented this with literature on regional equity planning, literature searches, practitioner conversations, and my experience with regional scenario planning.

From the start of the process, I wanted the framework to be familiar to practicing planners, so I assigned equity-planning recommendations to each stage in the scenario planning process. I looked to outside literature for a second dimension and found that the “five types of justice” (Sheller, Citation2018) clarified how different recommendations fit within theories of justice and equity. To the best of my knowledge, I included all equity recommendations suggested in the scenario planning literature and many from the general equity-planning literature.

Three Dimensions of the Framework

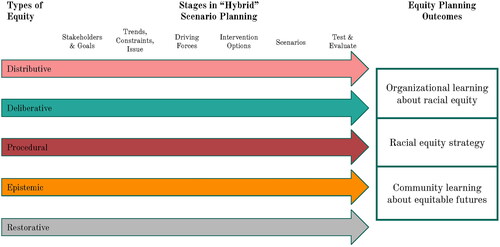

Three questions guided the Framework: 1) How can scenario planners promote the “five types of justice” (Sheller, Citation2018)? 2) What can planners do in each scenario planning stage to promote racial equity? 3) How can scenario planning outcomes support racial equity?

The Five Types of Justice

Sheller (Citation2018) argued that a more just society should promote five types of justice: distributive, deliberative, procedural, restorative, and epistemic. Although Sheller used the term justice and was arguing for social transformation, I applied the same types to government-led equity planning. The key difference is who advances these priorities and how. If the priorities are advanced through government agencies, then those policies constitute equity planning.

Distributive equity refers to promoting a fairer distribution of goods and opportunities, with a particular focus on ensuring greater opportunity for those who have the least. Within scenario planning, trends and driving forces include social and political structures enforcing racially unequal outcomes. The stakeholders select and evaluate policies to address the distribution of goods in each scenario. The MPO deploys appropriate tools to assess distributions across different racial identities (Avin et al., Citation2014).

Deliberative equity is the fair inclusion of racialized or other marginalized communities in planning processes. BIPOC stakeholders are proportionate or greater than their regional population share. Planners invite equity-focused community leaders, identified for visible leadership in social justice organizations (Twaddell et al., Citation2016). The scenario planners also ensure that each planning stage focuses on equity.

Procedural equity is crafting the planning process such that affected communities can take part as equals. This includes access to information, informed consent and local understanding, and procedures to guide deliberations toward racial equity. Scenario planners could employ an equity-focused working group to ensure that equity is considered in each stage. Then planners engage BIPOC communities beyond the stakeholders in scenario development and use.

Restorative equity requires admission of responsibility for harms, truth and reconciliation, and making reparations. This form is most closely aligned with reparative planning (Williams, Citation2024). Trends and forces spotlight historic and present regional structures that reinforce oppressive structures. Scenarios name racism, capitalism, and colonialism—and those who tacitly support those systems—as drivers of inequality. Stakeholders suggest and test reparational policies.

Epistemic equity is the recognition of BIPOC ways of knowing and looking to BIPOC communities for the generation of appropriate knowledge and facts to reconcile past injustices and present inequities. Epistemic equity would entail co-creating novel scenario-generating processes that center BIPOC knowledge systems.

The Scenario Planning Stages

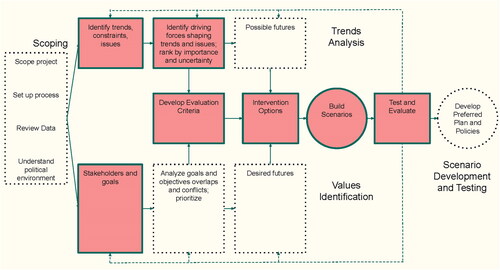

I grounded the scenario-building () stages in the process presented in Avin (Citation2007). Scoping determines whether scenarios are right for the problems at hand. In parallel, trend analysis crafts possible futures and community values direct desirable futures. Many MPOs will use values established in their long-range plan. Finally, possible and desirable futures inform indicators, interventions, scenarios, and plans. Testing and evaluation supply feedback for additional analyses. Stages included in the Framework have a solid outline in .

Several stages are not strictly related to scenario development: developing evaluation criteria, selecting intervention options, and testing and evaluation. Whether they take place alongside scenario development or afterward, they are essential for using scenarios to advance racial equity. Developing and deploying evaluation criteria are combined for legibility.

Stakeholders should be diverse across several dimensions (Chakraborty, Citation2010). Stakeholders should disproportionately represent marginalized populations (Xiang & Clarke, Citation2003) and include equity leaders (Twaddell et al., Citation2016). Planners should be trained to pay attention to influence in the room or bring in external expertise to manage power dynamics (Twaddell et al., Citation2016). Even though limited stakeholder groups are often required, scenarios should engage the broader public (Bartholomew et al., Citation2010; Chakraborty, Citation2010).

Trends, constraints, and issues are dependent on what communities’ value and prioritize. Stakeholders prioritize those trends that affect their lives. Which uncertainties matter depends on one’s socioeconomic position (Marris, Citation2003). Racial equity planning also encourages a deeper examination of poverty’s causes and constraints (Zapata & Bates, Citation2017), housing insecurity (Berbés-Blázquez et al., Citation2021), accessibility inequalities (Martens, Citation2017), and unfair labor markets (Clark & Christopherson, Citation2009), among other issues.

External forces include the causes and consequences of poverty (Xiang & Clarke, Citation2003). Scenario planning can alert stakeholders to the roots of inequity (Krumholz, Citation1982; Schulz, Citation2015). Looking forward, planners investigate institutional structures that continue to reproduce racial inequity (Frick et al., Citation2015). Racial inequity should also be emphasized as a driving force for democratic dysfunction (McGee, Citation2021).

Intervention options include actionable policies to advance racial equity, not just further studies (Zapata & Bates, Citation2017). Narratives and quantitative approaches can highlight how equity-oriented policies play out through each scenario (Avin, Citation2007; Goodspeed, Citation2020).

The best scenario narratives are emotionally interesting and connect to community issues (Xiang & Clarke, Citation2003). Imaginative stories enhance community understanding of the forces causing inequities (Sandercock, Citation2004). They can also generate hope for solutions (Zapata, Citation2021). All scenarios illustrate the equity outcomes and present more and less equitable futures (Trombulak & Byrne, Citation2022). Person-oriented narratives can increase scenario relatability and emotional resonance (Zapata, Citation2007).

Equity planning requires evaluation criteria with specific outcomes and metrics (Zapata & Bates, Citation2017). Some indicators, such as jobs accessible by transit, can serve as direct equity measures (Avin et al., Citation2014). Opportunity and social vulnerability mapping tools provide spatially meaningful ways to understand equity implications (Avin et al., Citation2014; Goodspeed, Citation2020; Knaap et al., Citation2020). Analyses also measure the impacts across different populations (Bills & Walker, Citation2017; Jones & Lucas, Citation2012; Karner et al., Citation2018). Planners establish clear and ambitious targets to minimize disparities (Martens, Citation2017), to meet minimum capabilities (Pereira et al., Citation2017), or to address historic disparities (Frick et al., Citation2015).

Scenario testing and evaluation examine the scenario and policy impacts in each. Technical tools need to be able to produce equity outcomes (Zapata & Bates, Citation2017). Qualitative assessment complements data and analysis in illustrating disparities (Avin et al., Citation2022). Analyses can help to assess which equity policies are robust to changing circumstances (Avin, Citation2007).

The Three Outcomes of Using Scenarios in Racial Equity Planning

The Framework can be used to support racial equity for any of the three scenario-planning outcomes: organizational learning, organizational strategy, and community learning.

For organizational learning, scenario planning informs the board and staff regarding the underlying causes and consequences of racial inequity. Planners cultivate a process that brings together BIPOC community members and equity leaders alongside organizational decision makers. The planners guide discussions toward forces influencing racial equity. In preparing scenarios, decision makers consider how structural forces could entrench or dissipate inequities.

For organizational strategy, scenario planning finds robust and contingent strategies to promote racial equity. Planners focus the process on distributive and restorative equity in policy choice, testing, and evaluation. They also examine the equity impacts of nominally race-neutral policies. BIPOC perspectives inform strategic guidance across scenarios.

For community learning, planners deeply engage communities regarding equitable futures. This includes sourcing trends, issues, and driving forces with communities of color and recruiting them for drafting scenario stories. Only a small subset of any region can participate in any public process, but robust engagement with select communities could deliver a compelling final product to BIPOC communities.

The Complete Framework

In the Framework (), the scenario stages are laid out across the top. Five arrows run across representing the types of equity planning. For a 5 × 6 matrix with recommendations in each cell, see Technical Appendix A. Finally, on the right side, I reinterpret the three scenario planning outcomes.

The Dispatches Case

Racial Inequity in the Philadelphia (PA) Region

The Philadelphia region has a history of racial discrimination, from the enforced displacement of the Lenape and Nantego peoples through the institutionalization of slavery for much of the 17th and 18th centuries (Gigantino, Citation2021), to segregation in squalid conditions in the 20th century (Du Bois, Citation2010). Planning enforced racial inequity with restrictive covenants, redlining, and exclusionary zoning (Hillier, Citation2003; Rhynhart, Citation2020); jurisdictional fragmentation (Rothstein, Citation2018); and highway building (Zuk et al., Citation2015).

The region is still segregated. Most of greater Philadelphia’s non-White population (50.2%) live in four majority non-White cities: Philadelphia, Trenton (NJ), Chester (PA), and Camden (NJ). Households in these jurisdictions have lower incomes, higher poverty rates, lower home values, and lower educational attainment than the region overall (). In terms of transportation—DVRPC’s central mandate—14% of Black workers and 6% of Hispanic workers commuted on transit, as opposed to 2% of White workers, with average travel times two to three times longer than car commuters (TransitCenter, Citation2021; U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2022).

Table 1. Census indicators for four DVRPC jurisdictions with most of the regions’ non-White population.

DVRPC

DVRPC is the MPO for greater Philadelphia, including the city of Philadelphia and four counties each in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Federal legislation requires that MPOs aid in planning for and dispersing federal transportation funding. MPOs produce long-range (20+ year) plans every 3 to 4 years, which establish the regional vision and prioritize fiscally constrained, air quality–significant transportation projects. Federal legislation encourages scenario planning to support the long-range plan. The two state governments also empower DVRPC to plan for non-transportation regional priorities. The current plan, Connections 2050, set a vision for an equitable, resilient, and sustainable Greater Philadelphia region that:

Preserves and restores the natural environment.

Develops inclusive, healthy, and walkable communities.

Maintains a safe, multimodal transportation network that serves everyone.

Grows an innovative and connected economy with broadly shared prosperity (DVRPC, Citation2021a).

The vision is advanced by a board consisting of one representative from each county; one each from the cities of Philadelphia, Trenton, Chester, and Camden; and three from each state government. More than 110 planners, analysts, and other staff support the board.

Connections 2050 includes $67.3 billion of transportation investments over nearly 30 years. This includes major roadway investments, such as widening U.S. Highway 130, and significant transit projects, such as the now-cancelled King of Prussia Line. Greater emphasis on equity could result in the additional inclusion of multimillion-dollar projects serving marginalized communities or the exclusion of projects negatively affecting those communities, even if these considerations only reallocate a small portion of the budget.

Scenario Planning at DVRPC

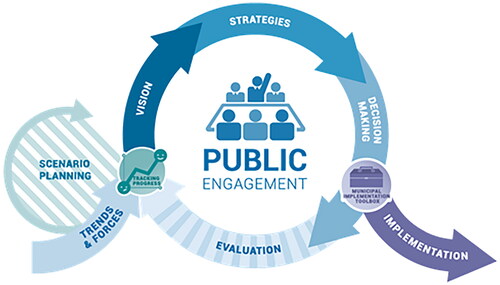

DVRPC develops the plan in 4-year cycles (). Scenarios aid DVRPC in grappling with future uncertainty in conjunction with more predictable drivers of change (e.g., demographic; DVRPC, Citation2021a). Scenario planning at DVRPC began in 2003 with the Regional Analysis of What-If Transportation Scenarios (DVRPC, Citation2003). Establishing the Futures Group (FG) in 2014—a quarterly stakeholder group—launched an era of exploratory scenario planning. The first FG scenarios—Greater Philadelphia Future Forces—informed Connections 2045, the plan adopted in 2017 (DVRPC, Citation2016).

Figure 3. DVRPC long-range planning cycle from DVRPC connections 2050 long-range plan (DVRPC, Citation2021a, p. 14).

The Connections 2045 vision included advancing equity and fostering diversity among the five vision principles. This vision informed Dispatches’ four scenarios emphasizing technology, climate, and equity. Dispatches supported the 2021 plan, Connections 2050 (DVRPC, Citation2021a). Connections 2050 incorporates universal strategies applying to all scenarios and scenario-specific/adaptive strategies. In 2022–2023, DVRPC returned to the Dispatches scenarios for further analysis.

The FG includes representatives of DVRPC, local/county government, state agencies, businesses, advocacy organizations, higher education, and nonprofits. In addition to scenario development, the FG hosts speakers, panels, and workshops on emerging forces.

A Commitment to Equity in Planning

Connections 2045—the plan in place when Dispatches was authored—included advancing equity and diversity as a planning principle with four goals: address equitable access for vulnerable populations, age-friendly communities, childhood access to good schools, and a commitment to development without displacement. Connections 2050 elevated equity to one of three cross-cutting principles, alongside sustainability and resiliency, to be applied to the four focus areas: the environment, communities, multimodal transportation, and the economy. In addition to the federally mandated equity and environmental justice analyses, equity is mentioned in sections on education, housing, and transportation. Equity is also 12% of the plan’s project evaluation score, based on whether projects serve census tracts with a high “Indicator of Potential Disadvantage” (IDP; DVRPC, Citation2021b).

A cross-cutting equity approach is evident in DVRPC activities. The publicly available IPD map uses age, gender, race, language, disability, and income to identify communities meeting the federal definition of equity target populations. DVRPC uses this tool for varied analyses, such as prioritizing safety investments. Interviews with staff indicated that the 2020 racial justice uprising prompted conversations about DVRPC and expanded equity-planning activities. For instance, DVRPC initiated surveys and focus groups to understand the BIPOC mobility opportunities and choices and has been working with marginalized communities to identify desired transportation improvements.

Dispatches from Alternate Futures

DVRPC prepared Dispatches from the spring of 2019 through summer of 2020. The scenarios were drafted by February 2020 and were later amended to include COVID-19 and the racial justice uprising. The presentation—news stories from future dates—was designed to alert, engage, and enhance plausibility. DVRPC also developed outreach videos for each scenario. Connections 2050 included later strategic analysis.

As is typical of exploratory scenarios, stakeholders suggested critical forces affecting the region and then ranked the finalists according to the depth of uncertainty and the potential impact. The FG included housing shortages and socioeconomic inequality among the high-impact/high-uncertainty forces. The plan team crafted four scenarios with stakeholder feedback defined by two axes of uncertainty: the pace of technological innovation and the degree to which political will and collective action tackle issues of climate change and equity. Equity primarily referred to socioeconomic equity, but scenario stories touched on connections between socioeconomic and racial equity (DVRPC, Citation2020a).

“Inclusive Tech” is a future in which novel technologies are harnessed for a greener and more democratically governed future. “People Power” is a future in which grassroots movements craft inclusive, sustainable communities with existing technology. In “Technology in the Driver’s Seat,” market-driven corporations expand the economy without substantially addressing inequity or climate change. Last, “Delayed Expectations” imagines a future in which lack of governmental or technological solutions exacerbates social, environmental, and economic challenges.

DVRPC used the scenarios to guide four FG strategic discussions and five public strategy workshops. Activities included imagining threats and opportunities, crafting new scenario headlines, and suggesting scenario-specific strategies. The strategy workshops each had a topical focus, including a February 2021 workshop on equity and civic engagement. The workshops directly informed Connections 2050 strategic recommendations. Breakout groups considered a single scenario at a time, with broader strategic recommendations emerging from synthesis across the breakout groups. Connections 2050 included 10 universal recommendations that emerged most frequently across scenarios and several scenario-specific recommendations.

Applying the Framework

Paradigmatic Case Analysis

Dispatches is a paradigmatic case (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006) of scenario planning. It is a state-of-the-practice regional scenario plan produced by an organization with a scenario-planning history. DVRPC’s commitment to equity, clear outside and within the scenarios, ensured that the Framework could be meaningfully applied. Single case studies run the risk of making unwarranted generalizations from a single case. However, the purpose of the case was primarily to demonstrate the applicability of the Framework. Suggestions for MPO practice have roots in the broader literature informing the Framework as well as my study of Dispatches.

I interviewed DVRPC staff and stakeholders, reviewed planning documents, and engaged as a participant observer. Before the interviews, I performed a stakeholder analysis. Through publicly available sources, I researched the 108 FG stakeholders and assigned each member to an organization type and focus areas. I derived the focus areas from the three E’s: equity, economy, and environment (Campbell, Citation1996). Individuals could be assigned to none, one, or multiple categories. Although this article is not about sustainability, the three E’s supply a straightforward way to compare the number of equity-focused stakeholders with other interests.

I completed 20 semistructured interviews addressing racial equity in scenarios and other research topics in January 2020 and 12 additional interviews focused solely on values and racial equity in the summer of 2022. Through both visits, I conducted 19 interviews across 12 DVRPC staff, including all scenario planners. I also conducted 14 interviews with 13 FG members, seven of whom I identified as equity oriented.

Dispatches is the central document in my analysis. Associated with Dispatches are archived agendas, minutes, and slides. I also examined Connections 2045 and Connections 2050 where they mentioned equity or scenarios. Finally, I explored the broader universe of DVRPC materials to understand the organization’s racial equity commitments.

Observations were performed in-person and remotely. When in Philadelphia, the DVRPC staff offered me a desk and a seat in long-range plan meetings. I attended two FG meetings in-person and three remotely. I also attended three virtual board meetings and watched others posted online.

I coded the data according to the Framework. I coded Dispatches for the equity topics and the stage in the scenario process. I then built summaries of what DVRPC did and how they did it. Finally, I synthesized these summaries and compared them with the Framework.

Applying the Framework to Dispatches

In the following section, I discuss how I applied the Framework to Dispatches. It primarily addresses the five types of equity. I weave the stages into the five types (see Technical Appendix B for a complete summary). I conclude with how Dispatches is used and not used to promote racial equity scenario-planning outcomes.

Distributive

Distributional concerns were present in the creation and use of Dispatches. The FG named several forces related to distributional equity. Stakeholders elevated the housing shortage and socioeconomic inequality, alongside five other forces, as having high uncertainty and impact. Socioeconomic inequality was selected as one of three structuring forces determining the scenarios, sharing an axis with climate change (). Two scenarios were defined by political will and collective action for greater equity and climate policy, while two scenarios were defined by market forces and individualism. This created space for FG members to discuss how socioeconomic inequity affected the region’s trajectory.

Figure 4. Key driving forces and the four scenarios in dispatches for alternate futures (DVRPC, Citation2020a, p. 17).

Scenario narratives and strategies highlighted some external causes of and solutions to racial inequity. As mentioned, socioeconomic inequity exacerbates racial divisions. The scenario stories presented social movements, including Black Lives Matter, as the driving force for policies that address structural inequities. In workshops, FG members suggested strategies for equitable transportation, housing, schools, and technology, although these suggestions were often single sentences or less.

Distributional outcome evaluation was absent. Dispatches’ quantitative indicators did not measure the distributions across racial groups. The indicators included percentage change in non-White households, but they did not assess the distribution of any benefits or burdens between populations. Changes in population by income group supplied a sense of changing poverty but did not capture the quality of impoverished lives. In addition, policy recommendations were not evaluated for their impacts.

Deliberative

The FG included 11 equity-oriented, 27 environmentally oriented, and 26 economy-oriented stakeholders. Even though the FG selected equity as a driving force, equity voices were limited and randomly assigned breakout groups could easily lack one. Although there is a large margin of error in assessing policy orientations based on online presence, the relative paucity of equity-oriented stakeholders was significant.

The lack of racial equity voices was reinforced by the lack of racial diversity. Four external stakeholders whom I spoke with, including one not identified as equity-oriented, expressed concerns about lack of racial diversity. This observation was affirmed by DVRPC staff, whose diversity recruitment fell short of targets. In recent FG meetings, diversity has increased.

Procedural

In the first scenario-planning meeting, the FG was instructed to focus on themes and forces that could “impact the region’s ability to achieve its vision” (DVRPC, Citation2019, p. 25). The staff reminded the FG of the vision, including the equity component, in each workshop. As the vision shifted in Connections 2050 to equity as a cross-cutting priority, messaging shifted accordingly (DVRPC, Citation2020b).

DVRPC never defined equity goals or target populations for the FG. Each stakeholder was implicitly left to define and prioritize equity for themselves. When breakout groups wrote strategic recommendations for advancing regional priorities within each scenario, the volume and specificity of equity recommendations varied tremendously, as detailed later. When I asked stakeholders about the issues that kept them up at night, some spoke about the region’s inequities. Others did not mention any related topic.

Procedural equity also includes the extent to which affected communities understand and contribute to the scenarios. DVRPC engaged non-FG stakeholders when the Dispatches document was published. They presented scenario videos at strategy workshops like the FG strategy workshop. From my data, the extent to which communities of color felt they understood and contributed was unclear.

Epistemic

To promote epistemic equity, we would expect to observe DVPRC partnering with BIPOC communities in co-designing the scenario process. This was not the case.

Restorative

I found no evidence that Dispatches and its use promoted restorative equity. In Dispatches, “Equity is defined as ‘the just and fair inclusion in a society where everyone can participate, prosper, and reach their full potential’” (DVRPC, Citation2020a, p. 15). This definition suggested a sufficiency standard in which equity is each individual having sufficient access to goods and opportunities to fully take part in society (Martens, Citation2017). The only mention of restitution occurred in the “People Power” scenario, in which a fictional public official said, “We had a lot of difficult and honest conversations around systemic racism, social justice, and reconciliation” (DVRPC, Citation2020a, p. 50). None of the policies in the more equitable scenarios were explicitly oriented toward restoring communities after racialized harm. This contrasts with the federal government’s Reconnecting Communities pilot program started just 2 years after Dispatches. Similarly, no strategic recommendations have addressed past harms.

Dispatches Racial Equity Outcomes

DVRPC’s use of the scenarios was oriented toward strategic guidance. In December 2020, FG breakout groups were assigned to develop strategies for one scenario and prioritize five strategies. The top 20 strategies included promoting equitable transportation and expanding transit, discounted transportation passes and credits, and affordable communications infrastructure and devices (DVRPC, Citation2020c).

DVRPC also conducted five Connections 2050 public strategy workshops that followed the FG workshop format. The February 2021 workshop thematically focused on equity and civic engagement (DVRPC, Citation2020b). Connections 2050 cited 10 universal recommendations from these exercises, including building equitable communities; enhancing transit; and expanding public outreach, equitable access to developing technologies, and affordable housing. Strategies assigned to specific scenarios included equitably improving education and equitable transportation and empowering community-led solutions (DVRPC, Citation2021a).

In a January 2023 workshop updating Dispatches, FG breakout groups were assigned one focus area (community, environment, economy, and transportation) and one scenario. Each breakout crafted headlines, named challenges and opportunities, suggested adaptive strategies, and assigned a transportation budget across 12 different priority investments. Equity was not an investment category, though resiliency was. The degree to which breakout groups suggested equity strategies varied widely. Some groups suggested no equity strategies. Others were vague: “Equity in technology is challenging.” Still, others suggested specific strategies—“Citizens council evaluating data to identify efficiencies, increase transparency, incorporate equity”—or added an equity investment category (DVRPC, Citation2023).

Neither organizational learning nor community learning appeared to be priority outcomes. For organizational learning, organizational leadership should engage along with members of affected communities to inform shared scenarios. Neither group was thoroughly represented. Although many DVRPC staff participated, including the deputy executive director, the executive director and the board participated infrequently. They were informed at regular intervals. This differs from private-sector scenarios, where the company board is often central (Schwartz, Citation1991). In addition, my stakeholder analysis showed a relative lack of equity-oriented stakeholders.

Similarly, the public engagement with Dispatches did not support community learning. DVRPC involved the public with finished scenarios. Such late exposure, even with compelling reports and videos, would not support deep learning about the forces shaping regional equity. Scenario-based learning is linked to collective development for collective learning.

Conclusions

Scenario planning and racial equity planning appear to be meeting as MPOs increasingly focus on racial equity. For scenario planners, the Framework supplies direction for promoting equity in their processes. This Framework builds on the five types of racial equity, a six-stage hybrid scenario process, and the three outcomes of public-sector scenario planning. Applying the Framework to Dispatches, a state-of-the-practice scenario plan, shows how far scenario planning can promote equitable strategies and how planners can do more to include BIPOC voices and assess racial equity strategies.

When considered against the history of public-sector scenarios, Dispatches advanced scenario planning for racial equity. However, assessed against the Framework, DVRPC could do more to intentionally promote racial equity through their scenarios. DVRPC staff did consistently remind stakeholders of racial equity in the regional vision, included socioeconomic inequity as a driving force, and developed strategic recommendations. However, DVRPC was unable to cultivate sufficiently diverse stakeholders despite their efforts and did not develop equity measures. For broader participation, MPOs need to examine their scenario processes to determine what value they could provide to equity stakeholders. Community stakeholder compensation, a DVRPC practice in recent environmental justice workshops, would support more equitable scenario planning. But getting people into the room is just one step. DVRPC should consider establishing an equity working group within the FG to vet the racial equity implications of their process and product.

I do not argue that MPOs should deliver scenarios that focus on equity while dimming other priorities. Rather, MPOs should use the Framework or other equity-oriented approaches to target desired equity-planning outcomes within broader scenarios. If these organizations pursue scenario planning without a clear intention to reduce racial disparities, they will likely contribute to those disparities through public inaction. This is as much the case when scenarios are used to examine the potential of emerging technology as when they focus on emergent social movements.

To promote organizational learning, MPOs need to bring equity advocates and their own organizational leaders into the scenario-generating process. For strategic guidance, MPOs should recruit BIPOC community members as stakeholders and develop methods for assessing equity outcomes of policies across scenarios. For community learning, planners should consider how they can include community members as co-creators of a more epistemically equitable scenario-planning process, one that addresses the uncertainties and aspirations that percolate within these communities.

This research is a largely theoretical exercise developed from literature, experience, and field research. As a White, male planning scholar, I look to advance equity planning, but I can never experience scenarios from the perspective of BIPOC individuals. More so, the use of scenarios for racial equity should not emerge from any single individual, but rather from the many perspectives of those affected by racial inequities. I welcome future revisions from members of affected communities who have participated in scenario planning and wish to reconcile the Framework with their own experience.

Researchers should also work along with communities to radically redesign scenarios. This research should lean into the restorative or reparative potential of using scenarios to identify futures that redress past harms. Community representatives would co-design scenario planning from their perspectives, rather than apply processes designed by professional planners and scholars. The results might look quite different from current practice. However, the process should be more meaningful to BIPOC communities as they craft and tell multiple stories born of their own worldviews.

This research was limited by the lack of perspectives distant from the DVRPC. Although some FG members were critical toward parts of Dispatches, they were invested in the process and dedicated workday hours toward creative, open-ended exercises. Their responses likely differed from those who stopped engaging, chose not to engage, or were never asked to take part. Such an outsider perspective may have informed more strident critiques of DVRPC scenario planning. Future research into regional scenario planning and equity should look beyond organizational boundaries.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (143.4 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel L. Engelberg

Daniel L. Engelberg [email protected]

Notes

1 I define BIPOC to refer to all people of color while centering the experiences of Black and Indigenous peoples. However, MPOs and all planning organizations should review the racial histories of their jurisdictions and their organizations to develop suitable reparative planning approaches.

References

- Avin, U. (2007). Using scenarios to make plans. In L. D. Hopkins & M. A. Zapata (Eds.), Engaging the future: Forecasts, scenarios, plans, and projects (pp. 103–134). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Avin, U., & Goodspeed, R. (2020). Using exploratory scenarios in planning practice: A spectrum of approaches. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(4), 403–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1746688

- Avin, U., Goodspeed, R., & Murnen, L. (2022). From exploratory scenarios to plans: Bridging the gap. Planning Theory & Practice, 23(4), 637–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2022.2119008

- Avin, U., Knaap, E., Knaap, G., Sartori, J., Barnett, B., Snyder, K., & Appleyard, B. (2014). Equity in scenario planning. National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education.

- Ayambire, R. A., & Moos, M. (2024). Inclusive futures? A systematic review of social equity in scenario planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 0739456X241238684. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X241238684

- Bartholomew, K. (2007). Land use-transportation scenario planning: Promise and reality. Transportation, 34(4), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-006-9108-2

- Bartholomew, K., Ewing, R., & Meakins, G. (2010). Integrated transportation scenario planning. Metropolitan Research Center, University of Utah College of Architecture + Planning. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/18592/dot_18592_DS1.pdf?

- Bauer, J., Ange, K., Twaddell, H. (2015). Advancing transportation systems management and operations through scenario planning. U.S. Department of Transportation. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop16016/fhwahop16016.pdf

- Berbés-Blázquez, M., Grimm, N. B., Cook, E. M., Iwaniec, D. M., Mannetti, L. M., Muñoz-Erickson, T. A., Hobbins, V., & Wahl, D. (2021). Assessing future resilience, equity, and sustainability in scenario planning. In Z. A. Hampstead, D. M. Iwaniec, T. McPhearson, M. Berbés-Blázquez, E. M. Cook, & T. A. Muñoz-Erickson (Eds.), Resilient urban futures (pp. 113–127). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63131-4_8

- Bezold, C. (2009). Aspirational futures. Journal of Future Studies, 13(4), 81–90.

- Bills, T. S., & Walker, J. L. (2017). Looking beyond the mean for equity analysis: Examining distributional impacts of transportation improvements. Transport Policy, 54, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.08.003

- Campbell, S. (1996). Green cities, growing cities, just cities?: Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369608975696

- Chakraborty, A. (2010). Scenario planning for effective regional governance: Promises and limitations. State and Local Government Review, 42(2), 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X10377344

- Clark, J., & Christopherson, S. (2009). Integrating investment and equity: A critical regionalist agenda for a progressive regionalism. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 28(3), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08327371

- Clavel, P. (1994). The evolution of advocacy planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(2), 146–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369408975564

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2016). Greater Philadelphia future forces technical report. https://www.dvrpc.org/reports/16007.pdf

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (2010). The Philadelphia Negro. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2019, February). Futures group introduction to scenario planning. https://www.dvrpc.org/longrangeplan/futuresgroup/pdf/2.15.19_presentation.pdf

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2020a). Dispatches from alternative futures. https://indd.adobe.com/view/39a8d5db-23df-4324-9099-4562dd8ed59b

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2020b). Long-range plan strategies workshop: Transportation technology. https://www.dvrpc.org/longrangeplan/futuresgroup/pdf/12.10.20_highlights.pdf

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2020c, December). Strategies workshop: Transportation technology presentation. https://www.dvrpc.org/longrangeplan/futuresgroup/pdf/12.10.20_materials.pdf

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2021a). Connections 2050: Plan for Greater Philadelphia. Process and analysis manual. https://www.dvrpc.org/reports/21028b.pdf

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2021b). TIP-LRP project benefit evaluation criteria. https://www.dvrpc.org/longrangeplanandtip/pdf/4690_designed_final_tip-lrp_benefit_evaluation_criteria.pdf

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2023). Scenario planning workshops: November 17, 2022 & January 11, 2023. https://www.dvrpc.org/plan/futuresgroup/

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC). (2003). Regional analysis of what-if transportation scenarios. https://www.dvrpc.org/reports/03020.pdf

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Fraser, N. (2016). Expropriation and exploitation in racialized capitalism: A reply to Michael Dawson. Critical Historical Studies, 3(1), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1086/685814

- Frick, K. T., Chapple, K., Mattiuzzi, E., & Zuk, M. (2015). Collaboration and equity in regional sustainability planning in California: Challenges in implementation. California Journal of Politics and Policy, 7(4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5070/P2CJPP7428924

- Gigantino, J. (2021). Slavery and the slave trade. Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/slavery-and-the-slave-trade/

- Goetz, E. G., Williams, R. A., & Damiano, A. (2020). Whiteness and urban planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(2), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1693907

- Goodspeed, R. (2020). Scenario planning for cities and regions. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Hillier, A. E. (2003). Redlining and the home owners’ loan corporation. Journal of Urban History, 29(4), 394–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144203029004002

- Imbroscio, D. L. (2006). Shaming the inside game: A critique of the liberal expansionist approach to addressing urban problems. Urban Affairs Review, 42(2), 224–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087406291444

- Inch, A. (2021). For utopian planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 22(4), 613–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1956815

- Jones, P., & Lucas, K. (2012). The social consequences of transport decision-making: Clarifying concepts, synthesizing knowledge and assessing implications. Journal of Transport Geography, 21, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.012

- Karner, A., Golub, A., Martens, K., & Robinson, G. (2018). Transportation and environmental justice: History and emerging practice. In R. Holifield, J. Chakraborty, & G. Walker (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of environmental justice (pp. 400–411). Routledge.

- Karner, A., London, J., Rowangould, D., & Manaugh, K. (2020). From transportation equity to transportation justice: Within, through, and beyond the state. Journal of Planning Literature, 35(4), 440–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412220927691

- Knaap, G.-J., Engelberg, D., Avin, U., Erdogan, S., Ducca, F., Welch, T. F., Finio, N., Moeckel, R., & Shahumyan, H. (2020). Modeling sustainability scenarios in the Baltimore–Washington (DC) region: Implications for methodology and policy. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(2), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1680311

- Kneebone, E., & Holmes, N. (2015). The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America. Transportation reform series for the metropolitan policy program. Brookings Institution.

- Krumholz, N. (1982). A retrospective view of equity planning Cleveland 1969–1979. Journal of the American Planning Association, 48(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944368208976535

- Marris, P. (2003). The politics of uncertainty: Attachment in private and public life. Routledge.

- Martens, K. (2017). Transport justice: Designing fair transportation systems. Routledge.

- Martens, K., & Golub, A. (2021). A fair distribution of accessibility: Interpreting civil rights regulations for regional transportation plans. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 41(4), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18791014

- McGee, H. (2021). The sum of us: What racism costs everyone and how we can prosper together. Random House.

- Metzger, J. T. (1996). The theory and practice of equity planning: An annotated bibliography. Journal of Planning Literature, 11(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/088541229601100106

- Mills, C. W. (2008). Racial liberalism. PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 123(5), 1380–1397. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2008.123.5.1380

- Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act. (2012). Pub. L. No. 112–141.

- Pastor, M., Benner, C., & Matsuoka, M. (2011). For what it’s worth: Regional equity, community organizing, and metropolitan America. Community Development, 42(4), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2010.532877

- Pereira, R. H. M., Schwanen, T., & Banister, D. (2017). Distributive justice and equity in transportation. Transport Reviews, 37(2), 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2016.1257660

- Rhynhart, R. (2020). Mapping the impact of structural racism in Philadelphia. Office of the Controller, Philadelphia. https://controller.phila.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/redlining_report-1.pdf

- Rothstein, R. (2018). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

- Sandercock, L. (2004). Towards a planning imagination for the 21st century. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(2), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360408976368

- Schulz, M. S. (2015). Future moves: Forward-oriented studies of culture, society, and technology. Current Sociology, 63(2), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392114556573

- Schwartz, P. (1991). The art of the long view. Doubleday.

- Sheller, M. (2018). Mobility justice: The politics of movement in the age of extremes. Verso Books.

- Sherman, S. A., & Chakraborty, A. (2022). Beyond plans: Scenario planning as a tool for regional capacity building. Journal of the American Planning Association, 88(4), 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2021.2004913

- Solis, M. (2020). Racial equity in planning organizations. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(3), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1742189

- TransitCenter. (2021). The Philadelphia Story—TransitCenter equity dashboard. https://dashboard.transitcenter.org/story/philadelphia

- Trombulak, S. C., & Byrne, J. M. (2022). Case study: Integrating scenario planning into sustainability practicums. Journal of Sustainability Education, 26. https://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/case-study-integrating-scenario-planning-into-sustainability-practicums_2022_02/

- Twaddell, H., McKeeman, A., Grant, M., Klion, J., Avin, U., Ange, K., & Callahan, M. (2016). Supporting performance-based planning and programming through scenario planning. United States Department of Transportation.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/philadelphiacountypennsylvania

- Williams, R. A. (2024). From racial to reparative planning: Confronting the white side of planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 44(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20946416

- Xiang, W.-N., & Clarke, K. C. (2003). The use of scenarios in land-use planning. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 30(6), 885–909. https://doi.org/10.1068/b2945

- Yiftachel, O. (1998). Planning and social control: Exploring the dark side. Journal of Planning Literature, 12(4), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/088541229801200401

- Zapata, M. A. (2007). Person-oriented narratives: Extensions on scenario planning for multicultural and multivocal communities. In L. D. Hopkins & M. A. Zapata (Eds.), Engaging the future: Forecasts, scenarios, plans, and projects (pp. 261–282). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Zapata, M. A. (2021). Planning just futures: An introduction. Planning Theory & Practice, 22(4), 613–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1956815

- Zapata, M. A., & Bates, L. K. (2017). Equity planning or equitable opportunities? The construction of equity in the HUD sustainable communities regional planning grants. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16657874

- Zapata, M. A., & Kaza, N. (2015). Radical uncertainty: Scenario planning for futures. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 42(4), 754–770. https://doi.org/10.1068/b39059

- Zegras, C., & Rayle, L. (2012). Testing the rhetoric: An approach to assess scenario planning’s role as a catalyst for urban policy integration. Futures, 44(4), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2011.10.013

- Zegras, C., Sussman, J., & Conklin, C. (2004). Scenario planning for strategic regional transportation planning. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 130(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9488(2004)130:1(2)

- Zuk, M., Bierbaum, A. H., Gorska, K., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Ong, P., Thomas, T., & Chapple, K. (2015). Gentrification, displacement and the role of public investment: A literature review. Journal of Planning Literature, 33(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12408.60168