Abstract

Introduction: Tobacco control policies have helped to reduce the health, social, and economic burden of commercial tobacco use worldwide. Little is known about the long-term impact of regulatory policies and functioning bodies that make recommendations to inform policies. The Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was formed in 2009 to evaluate the safety, health, and dependence of tobacco products and provide related advice and recommendations to the FDA and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. This article describes the first 10 years of the TPSAC activities and reflects on the impact of their service on regulatory actions.

Methods: We reviewed public documents from the 2010–2019 TPSAC meetings to examine the purposes, TPSAC decisions, public health participation in meetings, and concordance of the TPSAC recommendations with regulatory actions. Meeting agendas, transcripts, public testimony, and presentations were reviewed to obtain this information.

Results: Since 2010, the TPSAC held 25 public meetings with 178 speakers who provided oral public testimony. Sixty-four percent of meetings were held from 2010 to 2012, when three congressionally mandated reports were due on the topics of menthol cigarettes, harmful and potentially harmful constituents in tobacco products, and dissolvable tobacco products. Forty-four percent of meetings focused on menthol cigarettes, 32% on modified risk tobacco products, 16% on harmful and potentially harmful constituents, 12% on dissolvable tobacco, and 4% on tobacco addiction/dependence. FDA regulatory actions were largely nonconcordant with voting decisions by TPSAC.

Conclusions: The TPSAC has evaluated an enormous amount of science during the first 10 years, but their influence on regulatory policies has been limited. The TPSAC roles and functioning should be reevaluated to determine how TPSAC can better fulfill its mandate to inform the FDA’s regulatory decision making, which could ultimately reduce the burden of tobacco use in the United States.

I. INTRODUCTION

Tobacco regulation, or the power to control, direct, and have oversight over tobacco products, became an integral component of public health practice after the release of the 1964 Surgeon General’s Report.Footnote1 In 1965, the United States passed the U.S. Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act,Footnote2 which required that tobacco manufacturers, packagers, and importers who sell or distribute tobacco in the United States place four prescribed rotating health warnings about the harms of tobacco on cigarettes packages, billboards, and other advertisements to help curb the tobacco epidemic. Warnings, such as, “SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING: Smoking Causes Lung Cancer, Heart Disease, Emphysema, and May Complicate Pregnancy,” began to appear on tobacco packages in 1966 and were governed by the Federal Trade Commission.Footnote3 Under the U.S. Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act, tobacco manufacturers, packagers, and importers were also required to submit a list of ingredients added to tobacco to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (hereafter, the Secretary) annually. The Secretary was given authority to implement programs to educate the public about the harms of smoking; conduct, support, and disseminate research; establish the Interagency Committee on Smoking and Health; coordinate activities with other federal, state, local, and private agencies related to the effects of cigarette smoking; and submit biennial reports to Congress.Footnote4

However, it was not until 2009 that the U.S. Congress gave the federal government more comprehensive oversight over tobacco products. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA)Footnote5 of 2009 was passed under President Barack H. Obama’s administration. This landmark legislation, modeled after the 1965 Act, led to the transfer of the responsibility from the Federal Trade Commission to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which was given broad authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, sales, and distribution of tobacco products.Footnote6 The FDA established the Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) to implement the 2009 FSPTCA. In addition, the FSPTCA § 917 mandated the formation of the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) to inform the FDA’s regulatory actions.Footnote7

As mandated by the FSPTCA, the TPSAC was established to provide advice, information, and recommendations to the Secretary on a variety of issues, including the effects of altering nicotine yields and nicotine thresholds related to dependence; review of safety, dependence, or other health issues related to tobacco; and to develop mandated reports specified in the FSPTCA. Specifically, the TPSAC was charged with:

evaluating the impact of the use of menthol in cigarettes on public health, including such use among children, African Americans, Hispanics, and other racial or ethnic minoritiesFootnote8;

examining the nature and impact of the use of dissolvable tobacco products on the public health, including such use among childrenFootnote9;

determining the effects of the alteration of nicotine yields from tobacco products and whether there is a threshold level below which nicotine yields do not produce dependence on the tobacco product involvedFootnote10;

reviewing applications submitted by a manufacturer for a modified risk tobacco productFootnote11;

providing recommendations to the Secretary regarding any regulations to be promulgated under the actFootnote12;

reviewing any applications for new tobacco products or petitions for exemption under Section 906(e) of the FSPTCAFootnote13; and

providing recommendations on any other matter as provided in the FSPTCA.

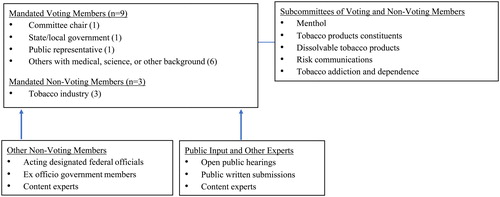

During the first 6 months of the FSPTCA, the FDA formed a 12-member committee that included an appointed chair.Footnote14 The law specified that members with voting rights include seven health professionals practicing in oncology, pulmonology, cardiology, toxicology, pharmacology, addiction, or other relevant specialty and represented various disciplines as specified by the law (e.g., medicine, science, or technology involving the manufacture, evaluation, or use of tobacco products); one officer of state, local, or federal government; and one representative of the general public.Footnote15 Nonvoting members, including one representative from tobacco industry manufacturers, tobacco small business, and tobacco growers (see ).

It was a monumental task for federal officials to meet the requirement of establishing TPSAC within 6 months after the enactment of the FSPTCA in addition to building the foundation for the CTP within the FDA. Federal officials transferred their positions from the Office on Smoking and Health of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Tobacco Control Research Branch of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the FDA. These pioneers were charged with building a new regulatory agency, hiring staff, and meeting other mandated requirements within the first year of enacting the FSPTCA. Establishing TPSAC was a high priority because this entity was charged with producing multiple reports within the first 2 years of the enactment of the FSPTCA.Footnote16

Much like federal officials who faced the enormous task of establishing the CTP, the inaugural members of the TPSAC faced an unprecedented task of producing three mandated reports by 2011.Footnote17 The initial work produced a lot of momentum, sense of contribution, and frustration following lawsuits by the tobacco industry that challenged the procedures of the TPSAC.Footnote18 As a result of these initial challenges, many in the tobacco control field wondered whether TPSAC, as a congressionally mandated body, could inform tobacco regulations effectively. This article critically analyzes the first 10 years of activities of the TPSAC and reflects on the impact of their public service on regulatory actions. Data from the examination of these activities can inform future activities, functions, and actions of the TPSAC and the CTP.

II. METHODS

A. Sample

To document the activities and impact of the TPSAC, we reviewed publicly available documents from the TPSAC meetings from 2010 to 2019. These documentsFootnote19 included the archived list of TPSAC members, meeting announcements, meeting agendas, meeting rosters, questions to the committee, public participants and submissions, briefing materials, FDA and tobacco industry presentations, meeting transcripts, and summary minutes. Because our analysis was not dependent on capturing information from the video webcast, we did not review videos. We reviewed meeting materials from the first TPSAC meetings on March 30–31, 2010, through February 6–7, 2019. This article is co-authored by former members of TPSAC, whose collective service to TPSAC spans most of the period of meetings held during the first 10 years. The authors of this article include TPSAC members who helped to verify additional information to support the discussion of the results in this article.

B. Analysis

We were specifically interested in the activities that the TPSAC performed that were consistent with its function as mandated by the FSPTCA: provide advice, information, and recommendations to the Secretary on a variety of issues, including the effects of altering nicotine yields and nicotine thresholds related to dependence; review of the safety, dependence or other health issues related to tobacco; and develop mandated reports specified in the FSPTCA. For the analysis, we summarize the purposes of each meeting, decisions and recommendations of TPSAC, public health participation in meetings, and concordance of the TPSAC recommendations with regulatory actions. Descriptive data are reported and summarized in the next section.

III. RESULTS

A. General Characteristics of Meetings and Meeting Participants

1. Number of Meeting and Meeting Topics

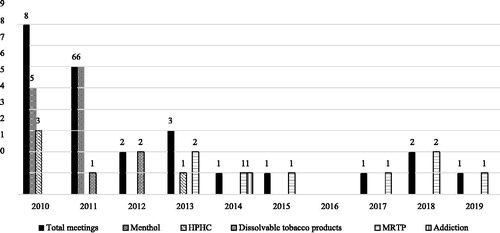

The majority of the TPSAC meetings were public with the exception of a few closed sessions. The FDA website lists each primary and subcommittee meeting whose durations ranged from 1 to 3 days.Footnote20 For example, in 2011, two meetings were held on consecutive days but are listed separately. On February 11, 2011, the menthol subcommittee met, and on February 10, 2011, the full TPSAC met. shows the number of meetings of the TPSAC from March 30, 2010, to February 6–7, 2019 (n = 25).

Figure 2. Number of TPSAC meetings, 2010–2019 (n = 25). Notes: We present the total number of meetings by year. Several meetings covered multiple topics.

Sixty-four percent of the meetings were held from 2010 to 2012, the time period when three congressionally mandated reports were due on the topics of menthol cigarettes, harmful and potentially harmful constituents (HPHCs) in tobacco products, and dissolvable tobacco products. During the 10-year period (2010–2019), the number of meetings per year substantially declined after 2012, with an average of 1.3 meetings per year. In 2014 and 2015, only one meeting was held each year. There were no meetings after the meeting on April 9–10, 2015, until the meeting on April 6, 2017, leaving a period of nearly 24 months when TPSAC did not meet at all. During this lag in meeting time, there were legal challenges to perceived conflicts of interests of TPSAC members. Judge Richard Leon’s ruling in 2015 expanded the conflict of interest criteria based on his view that “substantial” funding received by TPSAC members from private and public sources may have influenced TPSAC recommendations.Footnote21 This ruling prompted the FDA to reevaluate the previously disclosed conflicts (receipt of funding from pharmaceutical companies and NIH) and end the terms for four members to avoid the appearance of impropriety.Footnote22 The FDA replaced two of the members immediately, but the chair position remained vacant following this ruling.Footnote23

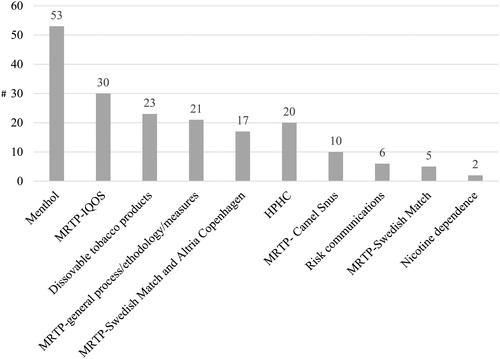

Over the 10-year period, 44% (n = 11) of the meetings focused on menthol cigarettes, 32% on modified risk tobacco products (MRTPs), 16% on HPHCs, 12% on dissolvable tobacco products, and 4% on tobacco addiction/dependence. Most meetings focused exclusively on a single topic, but some covered multiple topics. For example, the July 21–22, 2011 meeting focused on the topics of menthol cigarettes and dissolvable tobacco products. Over a 5-year period from 2014 to 2019, all meeting topics focused on MRTPs, with the exception of one meeting on addiction/dependence in 2014.

2. Structure of TPSAC

A total of 27 regular voting members and nine nonvoting (tobacco industry) members served on TPSAC during the 10-year period.Footnote24 Forty-four percent of TPSAC voting members were women who worked in academia or state health departments, and one worked for a nonprofit health organization. All tobacco industry representatives were male. A total of three underrepresented minorities have served on TPSAC. Two former members were African American and one American Indian. Since 2010, TPSAC has had three chairs, the inaugural chair, Jon Samet, MD, MS (2010–2014), who served the longest term, followed by Phillip Huang, MD (2015–2018), and Robin Mermelstein, PhD (2018–2019). Each member served different term periods (i.e., 2- to 4-year terms) and rotated off the committee at different points in time such that several members were retained as others rotated on and off the committee.

The FDA solicited multiple nonvoting consultants or experts from federal agencies (e.g., CDC, FDA) who presented data on topics relevant to their expertise (n = 29), several of whom were former voting TPSAC members or eventually became TPSAC voting members. Two scientific experts served as ad hoc voting members over the course of four meetings to discuss dissolvable tobacco products, MRTPs, and HPHCs (January 18, 2012; March 1–2, 2012; April 30, 2013; August 13, 2013). On August 15, 2013, a joint meeting of the TPSAC and the FDA Risk Communications Advisory Committee, which was convened to discuss the results of the experimental study on the public display of the list of HPHCs in tobacco products, was held. An additional eight voting members on the risk communications committee participated.

The FDA has the authority to adapt the structure of the TPSAC to accomplish the tasks of the committee.Footnote25 During the first meeting, the FDA added ex officio (i.e., by virtue of holding another office) nonvoting members who represented major stakeholders with interest in tobacco prevention and control. These nonvoting members included representatives from the CDC, the Indian Health Services, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NCI, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. In addition, government representatives from the FDA’s CTP attended the meetings and held a seat at the TPSAC discussion table. Other experts invited to attend the TPSAC meetings included government agency/institute and tobacco industry presenters who were not involved in the discussions beyond their presentations.

3. Meeting Subcommittees

Following the first initial meetings of TPSAC, the CTP and TPSAC recognized that in order to comply with the mandate to produce three reports during the first 2 years of the enactment of the FSPTCA, subcommittees of voting and nonvoting members and expert consultants needed to be formed. The first three subcommittees focused on the topics of menthol cigarettes, tobacco product constituents, and dissolvable tobacco products. Later, the risk communications committee meeting was developed and expanded the expertise of the existing TPSAC. Subcommittee meetings were often public meetings, which impacted the depth of the discussions that occurred.

4. Open Hearing Speakers and Written Submissions from the Public

The TPSAC had the opportunity to consider written and oral testimony from the general public as part of their decision making.Footnote26 TPSAC members and the FDA weighed this evidence along with other evidence presented during the meetings to inform their decision making. A total of 178 public speakers voluntarily provided public oral testimony during the open public hearings. If a meeting was held across 2 days, we counted each public speaker per day irrespective of whether testimony was provided by the same speaker. These open hearing speakers include representatives from public health organizations, tobacco industry, advocacy groups, for-profit companies affiliated with tobacco industry, health policy organizations, consultant groups, academic think tanks, and other representatives who requested to deliver a brief oral presentation during the public hearing portion of the meetings. Over the 10-year period, public hearing speakers who provided testimony related to MRTPs comprised nearly half (46.6%) of all speakers. Speakers who provided testimony on menthol cigarettes comprised nearly one-third (29.7%) of public speakers. shows the number of speakers by topic.

B. Process Questions Related to the TPSAC

The federal officials established a number of process-related questions that TPSAC was asked to consider for each of the meetings from 2010 to 2017 (n = 16) (see ). The types of questions posed to TPSAC included questions related to general meeting processes; support needed to facilitate the operations of the TPSAC; feedback on written reports; processes for writing reports; scientific approaches, methods, and analysis; approaches for reviewing and evaluating the scientific evidence; data needed from the literature, scientific studies, tobacco industry, and the FDA to inform decision making; types of models needed to assess public health impacts; how to evaluate relative risks; communication objectives for the lay public; definitions of dependence and addiction; evaluations of product application submissions; and discussions related to the public health impacts related to menthol, dissolvable tobacco products, HPHCs, and MRTPs. For example, during the March 30–31, 2010, meeting, the FDA asked TPSAC to describe the type of support it needed to complete the menthol report and meet the statutory deadline. During several meetings, the FDA asked TPSAC to describe the additional topics that it wanted the tobacco industry to present and address at future meetings (e.g., menthol, dissolvables). During the August 16, 2013, meeting, they asked TPSAC how it would recommended that the FDA evaluate the relative health risks of a MRTP to individuals. During the April 16/18, 2014, meeting, TPSAC was asked to discuss which factors related to dependence/addiction should be included in the evaluation of product submissions. The FDA also asked TPSAC to identify information that would be most useful and least useful to receive prior to review of an MRTP application. These and other process questions were posed to TPSAC during the April 6, 2017, meeting.

C. Decision-Making Questions Posed to TPSAC That Required Voting

1. Decision Making Related to Reports

TPSAC was asked to vote during seven meetings to make decisions related to tobacco products. The first voting meeting occurred on August 30, 2010. TPSAC voted on whether they agreed that certain constituents be included on the list of HPHCs in tobacco products and whether they agreed with specific machine regimens (International Organization for Standardization [ISO] and Canadian) to be used to measure HPHCs. This list of 93 constituents was posted on the FDA’s website 18 months later in March of 2012Footnote27 and included a list of chemicals related to cancer, cardiovascular disease, respiratory effects, reproductive problems, and addiction. The list was largely comprised of chemicals found in cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. At the time when the report was developed, neither electronic cigarettes, cigars, nor any other emerging tobacco products were under the authority of the FDA. After the publication of the HPHC report, the FDA began requiring tobacco manufacturers and importers to report the levels of HPHCs found in their tobacco products and tobacco smoke. The FDA has required that manufacturers and importers test their products for 20 of these chemicals for which testing methods are established.Footnote28 The FDA evaluates the quality and reliability of this evidence submitted by the tobacco industry. The FDA is also required to publish the HPHCs in brands and subbrands in a way that the information is not misleading to the public and incorporate messages about HPHCs in its educational campaigns.Footnote29

On July 21, 2011, TPSAC made a final vote related to the menthol subcommittee’s report and recommended that “the removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit public health in the United States.”Footnote30 The TPSAC voted 8 to 0 in support of this recommendation. Following this recommendation, the FDA did not take any actions from 2011 to 2019 to remove menthol cigarettes from the marketplace. In fact, in 2013, FDA Commissioner Hamburg stated in a report to Congress on Progress and Effectiveness of Implementing the TCA that TPSAC did not recommend a specific mechanism, timeline, or regulatory action that the FDA might pursue to address this conclusion,Footnote31 suggesting that TPSAC had failed to provide sufficient guidance when in fact several TPSAC members who were actively involved in the development of the report stated that they were unaware that TPSAC had the option to recommend mechanisms and a timeline through the recommendation. Further, in our analysis, we did not identify information in the meeting notes that suggested that TPSAC was provided guidance to suggest a mechanism or timeline.

On March 1, 2012, TPSAC voted 7 to 0 that they agreed with the content of the report on dissolvable tobacco products. TPSAC acknowledged that the report summarized the current state of the literature and that it was based on what was known. It was difficult for TPSAC to reach decisions due to the limited information available on dissolvable tobacco products. It is not clear whether the report itself informed FDA’s decision to mandate warning statements related to the addictiveness of tobacco products on dissolvable tobacco products beginning in 2018. Dissolvable tobacco products are a covered tobacco product (i.e., a tobacco product deemed under the deeming final rule to be subject to chapter IX of the 2018 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act)Footnote32 and therefore, are subject to the regulation that required that they bear an addictive warning statement.

2. Decision Making Related to Modified Risk Tobacco Product Applications

The remaining four meetings were voting meetings convened to review and discuss modified risk tobacco product applications (MRTPAs). According to Section 911 of the FSPTCA, products that are sold or distributed to reduce harm or risk of tobacco-related disease may not enter the market unless the FDA issues an order.Footnote33 The Secretary has the authority to refer these applications to review by TPSAC, who must report their recommendations back to the Secretary within 60 days.Footnote34 These MRTPA were submitted by Swedish Match North American, Inc. for 10 smokeless snus tobacco products (general loose, general dry mint portion original mini, general portion original large, general classic blend portion white large [0.48 oz.], general classic blend portion white large [0.38 oz.], general mint portion white large; general Nordic mint portion white large [0.48 oz.]; general Nordic mint portion white large [0.38 oz.], general portion white large, general wintergreen portion white large). RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company submitted applications for six smokeless tobacco products (camel snus frost, camel snus frost large, camel snus mellow, camel snus mint, camel snus robust, camel snus winterchill). Phillip Morris Products S.A. submitted applications for three heated tobacco products (IQOS systems with Marlboro heatsticks, IQOS system with Marlboro smooth menthol heatsticks, IQOS system with Marlboro fresh menthol heatsticks). Altria Client Services LLC/U.S. and Smokeless Tobacco Company LLC/U.S. filed applications for the smokeless tobacco product Copenhagen Snuff Fine Cut. Of these applications, Swedish Match North American snus products and Phillip Morris heated products were approved to market their products in 2019.

TPSAC first reviewed the MRTPA submitted for 10 products by Swedish Match during the April 9–10, 2015, meeting. Subsequently, the products were discussed again as an amended application during the TPSAC meeting held February 6–7, 2019. However, the voting process that occurred during the first review of the products in 2015 did not occur during the second review of the products. The FDA concluded that the applicant had addressed the previous concerns raised related to the modified risk claims. During the first meeting, concerns were raised by TPSAC that Swedish Match had not presented sufficient evidence related to the products health effects or impact of modified risk claims on women, pregnant women, racial groups, or persons of low socioeconomic status. TPSAC did not vote on whether these concerns were addressed in the revised application. Swedish Match was approved on October 22, 2019, to market 8 of the 10 snus (smokeless) tobacco products as MRTPs, 4 of which are mint or wintergreen flavors. In addition, the FDA approved Swedish Match to market the claim, “Using General Snus instead of cigarettes puts you at a lower risk of mouth cancer, heart disease, lung cancer, stroke, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis.”

Copenhagen Snuff Fine Cut was grandfathered to remain on the market as allowed by FSPTCA. The MRTPA that Altria Client Services LLC/U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Co., LLC submitted sought approval from the FDA for its modified risk claim. TPSAC generally felt that the MRTP claim “IF YOU SMOKE, CONSIDER THIS: Switching completely to this product from cigarettes reduces risk of lung cancer” was accurate. The TPSAC did not think that the claim was harmful, but they were not confident that the claim would actually motivate people to switch from cigarettes to the smokeless tobacco product completely. The FDA asked for public comments on this product claim, which closed in January of 2020. As of 2020, the FDA has not yet approved use of the MRTP claims for the Copenhagen Snuff Fine product.

On April 30, 2019, the FDA approved Phillip Morris’s request to market IQOS, a heated tobacco product that is marketed in menthol “fresh” and “smooth” and nonmenthol (regular) flavor. Interestingly, IQOS was approved under the premarket tobacco product application (PMTA) route. TPSAC evaluated the product as an MRTPA on January 24–25, 2018. The MRTPA has not yet been approved by the FDA as of April 2020. During the January 24–25, 2018, meeting, several votes were made including the vote of 8 (yes), 0 (no), and 1 (abstain) that Phillip Morris had not demonstrated that switching from cigarettes to IQOS would reduce the risk of tobacco-related diseases. In order for an applicant to be approved under the PMTA pathway, the tobacco industry has to demonstrate that the marketing of the product would be appropriate for the protection of public health, considering the risk and benefits to the population as a whole, including youth, users, and nonusers. The FDA stated that because IQOS delivers nicotine levels close to that of combustible cigarettes it is likely that IQOS users would completely transition from combustible cigarettes and use IQOS completely.Footnote35 Although TPSAC did not review the application under the PMTA pathway, as part of their review TPSAC had the opportunity to vote on the population benefits of IQOS. Seven of 9 TPSAC members voted that the likelihood of U.S. smokers completely switching to IQOS system was low and two stated that the likelihood was medium. In addition, 5 of 8 TPSAC members voted that the likelihood of U.S. smokers becoming long-term dual users of IQOS and combusted tobacco was medium and 3 stated that the likelihood was high. No TPSAC member voted low. Of the 8 members, 5 members stated that the applicant had not demonstrated that reductions in exposure are reasonably likely to translate to a measurable and substantial reduction in morbidity and/or mortality.

Following the approval of IQOS, the FDA stated that heated tobacco products must adhere to all existing FDA regulations, but the FDA has also limited youth access to IQOS and exposure by placing stringent restrictions on how IQOS products are marketed via websites and social media. Phillip Morris is also required to provide information on how it targets adults and how it will restrict youth access. Less than 1 year from approval, evidence emerged that Philip Morris used covert marketing strategies to imply that the FDA endorsed its product and has violated FDA marketing regulations.Footnote36

IV. DISCUSSION

In summary, this article described the first 10 years of activities of TPSAC and reflects on TPSAC’s impact on regulatory actions. The TPSAC held 25 meetings from 2010 to 2019 to discuss, make decisions, and submit recommendations to the FDA regarding tobacco products. The inaugural members of the TPSAC were occupied with fulfilling the congressional mandate to produce three reports (HPHCs, menthol, and dissolvable tobacco products), the only reports mandated by the TCA. The number of TPSAC meetings substantially declined after the congressionally mandated reports were delivered to the FDA, and there was a 2-year lapse in meetings between April 2015 and April 2017. This lag in meeting time may have been partly due to the fact that the FDA did not have a sufficient number of members to serve on TPSAC. Several members were asked to resign from TPSAC because the FDA lawyers perceived that their reported conflicts were too much of a risk. The majority of meetings in the first 2 years focused on menthol cigarettes. Following the delivery of the congressionally mandated reports, TPSAC meeting foci shifted to the review and evaluation of MRTPAs presented to them by the FDA. The impact of TPSAC on regulatory actions has been limited. During the first 10 years, TPSAC cast votes at 7 of 25 meetings. It appears that the only vote where there is concordance between TPSAC votes and FDA actions is the vote related to HPHCs.

The FDA followed the structure of TPSAC as described in the FSPTCA, but TPSAC also used subcommittees that included experts who could provide scientific advice on various topics discussed during the meetings. The FDA added representatives from federal agencies/institutes such as NCI, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Indian Health Services, CDC, and National Institute on Drug Abuse, whose experts contributed to scientific discussions at the meetings. Open public testimony and public submissions were provided during most meetings, but the degree to which they informed TPSAC decision making varied on the topic, quality of the testimony, and relevance of the testimony to the questions that TPSAC were directed to answer. Unlike the FDA, TPSAC was not required to review all of the public submissions to the FDA. The mandated composition of the TPSAC meetings included nonvoting tobacco industry representatives. Representatives over the 10-year period included males who represent growers and large and small manufacturers. Tobacco industry representatives were selected by the FDA as nonvoting members, but all had a voice at the table by contributing to the discussion of voting members, making statements that question the science as per the meeting notes, and seeking to develop relationships with scientists during meeting breaks, which are actions consistent with what the tobacco industry has done in the past.

Although it is not always clear how the FDA used reports and recommendations from TPSAC, the FDA did take regulatory actions consistent with the TPSAC vote related to HPHCs. The FDA used the HPHC report to require industry actions related to the reporting of 20 constituents for which there are robust methods of measurement. The FDA required that the tobacco industry place warning labels related to the addictive nature of nicotine on dissolvable tobacco products. It is not clear whether this action would have been taken without having the TPSAC report.

We do not know whether the FDA was under pressure from other entities to take actions that were not consistent with TPSAC recommendations. In most cases, the FDA made their own regulatory decisions with apparently little regard to the TPSAC recommendations or potential input that they could have leveraged from the TPSAC. For example, the FDA missed an opportunity to utilize the expertise and recommendations from TPSAC to inform whether it would allow Phillip Morris Products SA to release IQOS into the U.S. public market. Under the FSPTCA, the FDA had the authority to allow TPSAC to review the IQOS applications via the MRTPA and PMTA pathways. In addition, the FDA had sufficient information from TPSAC’s review of the application under the MRTPA pathway to not permit the sales of IQOS on the market. However, 1 year after TPSAC’s review of IQOS as an MRTP, the FDA approved IQOS under the PMTA route and suggested that Philip Morris did demonstrate that smokers of combustible cigarette are likely to completely transition from cigarettes to IQOS.Footnote37 This decision was contrary to TPSAC’s voting decision. TPSAC’s votes indicated that Phillip Morris did not demonstrate that switching from cigarettes to IQOS (menthol or regular flavor) would reduce the risk of disease. Exactly why the FDA decided to allow IQOS to enter the market when TPSAC determined that the science did not support this decision is unclear.

In the case of menthol cigarettes, where a unanimous TPSAC vote recommended that menthol cigarettes be removed from the public market, no additional public actions were taken by the FDA from 2010 to 2019 in response to this recommendation. The lack of regulation to remove menthol cigarettes from the market as suggested by TPSAC has been discussed.Footnote38 More than half of the new tobacco products approved by the FDA are menthol/mint/wintergreen flavored (four snus and two IQOS flavors). The inclusion of these flavors leaves dwindling hope that the FDA will at some point act on the recommendations made by the inaugural TPSAC, which was supported by a body of scientific evidence.

There did not appear to be a clear process for how the FDA engaged TPSAC for scientific review of a revised application. For example, following the TPSAC review of Swedish Match North American snus products in 2015, the FDA decided that they would only engage TPSAC in a nonvoting discussion related to a revised modified risk claim. It is important that TPSAC have the opportunity to vote and determine whether all of the concerns raised by TPSAC during prior meetings were addressed.

This discussion of TPSAC and review of the nuances of its operations reflects the unique nature of TPSAC as a federal advisory committee. The Federal Advisory Committee ActFootnote39 was established in 1972 to ensure that federal officials and the nation have access to information and advice on a broad range of issues that impact federal policies and programs. According to the U.S. General Services Administration, there are over 1,000 federal advisory committees.Footnote40 TPSAC is governed by the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which provides standards for formation and operations, but TPSAC is not subject to Section 14 of the Federal Advisory Committee Act,Footnote41 which limits federal advisory committees to a 2-year duration. TPSAC was established under an Act of Congress (FSPTCA), and its charter remains in effect until amended or terminated by the FDA Commissioner.Footnote42 Thus rules, order, and regulations under the Federal Advisory Committee Act apply except when the Act of Congress specifies otherwise.Footnote43 Because the charter is ongoing and helpful regulations could save more than 480,000 lives lost each year to tobacco use and exposure, TPSAC recommendations and how the committee operates must be critically examined.

A. Limitations

This qualitative content analysis of publicly available documents on the FDA website included a review of multiple written documents. We did not review the videos of the TPSAC meetings because the information needed for this analysis was available in the summaries and on other locations on the FDA website. We included several former TPSAC members as authors and who cover the TPSAC tenure from 2010 to 2018. In some cases, the written notes taken by CTP staff were not consistent with the agendas on record. For example, if meetings were held on 2 consecutive days and they were listed separately on the FDA website, we counted the meeting as an individual meeting. However, the notes that describe the number of attendees and public speakers cover both days and not individual meeting days.

B. Recommendations

Our final thought is that TPSAC’s expertise can be better utilized to inform regulatory processes, agendas, and decision-making. The FSPTCA provides TPSAC with broad authority, which is currently underutilized. The following recommendations may help to create new opportunities for TPSAC to inform tobacco regulation.

Federal advisory committees can meet at the call of, or in advanced approval of, a designated officer or employee of the federal government.Footnote44 Meeting agendas must be approved by such an officer. This rule does not preclude TPSAC members from requesting a meeting or suggesting agenda items. Thus, many of the subsequent recommendations are based on the notion that TPSAC can request meetings or agenda items that it deems important to informing tobacco regulations. The subsequent recommendations also assume that “agenda setting” on topics of interest is a participatory process between the public experts and designated officer or employee of the federal government in charge of calling a meeting and establishing the agendas.

TPSAC has the broad authority to provide recommendations on any matter related to the FSPTCA. Capitalizing on these authorities will provide the FDA with the scientific knowledge needed to inform sound and robust regulatory decisions that impact the public’s health. The chair and voting members should consider exercising their broad authority and define areas in which TPSAC seeks to influence; recommend processes for evaluating the science to inform regulatory actions; or make any recommendations to the Secretary regarding any regulations to be promulgated under the FSPTCA.

If TPSAC has evaluated a product via the MRTPA pathways, then their evaluation should inform the PMTA pathway when expert opinion has been rendered and is relevant to the PMTA and vice versa.

The process for TPSAC’s review of a revised application should be clarified and allow for TPSAC to revote using new data submitted by the tobacco company.

TPSAC should define questions in their evaluation of products that leads to voting decisions related to a vulnerable groups and populations disproportionately impacted by tobacco use. TPSAC should be able to add items to the meeting agenda and submit voting questions that help determine the costs and benefits of a new product on a specific population group (e.g., women, minorities, low literacy or socioeconomically disadvantaged groups).

Because the FDA has the authority to adapt the structure of the TPSAC to accomplish the tasks of the committee, TPSAC should recommend the type of structure that would help to facilitate its productivity.

TPSAC should consider updating the HPHC list and recommendations on dissolvable tobacco products as new products enter the market.

TSPAC should consider updating the report on menthol in cigarettes and incorporate its evaluation of menthol in emerging tobacco products and their impact on the public’s health.

TPSAC is not limited to producing congressionally mandated reports only and should determine other scientific reports needed to help advance tobacco regulation.

The FDA process for providing input to TPSAC is largely geared toward a scientific audience, even though the public hearing option is available. Lay-friendly strategies are needed so that non-scientists can actively and easily participate in sharing their thoughts and opinions about tobacco product regulation. Comments speak to the emotional toll of commercial tobacco on population groups may not inform recommendations with the same weight as scientific evidence-based comments.

Separate from TPSAC, other credible bodies may consider reviewing the science that suggests that new products should enter the market and make recommendations for regulatory action. External bodies should track the concordance of FDA decision making related to tobacco products with discussions and votes held during TPSAC meetings.

V. CONCLUSIONS

As we reflect on the first 10 years of opportunities and challenges of TPSAC, it is important to consider the lessons learned from the first 10 years of TPSAC and how TPSAC’s scientific recommendations can be better utilized to inform regulatory decisions. TPSAC has been asked to render its recommendations based on the science. If the science will not inform decision making, then TPSAC should provide recommendations based on the criteria that the FDA uses to inform their decision making. In the future, it is important to continue to evaluate the progress of TPSAC, the concordance of its recommendations with FDA actions, and how TPSAC’s composition influences voting and recommendations. It is our public responsibility to assure that TPSAC evolves into a body that will do more than review PMTAs and MRTPAs. The impact of FSPTCA on the public’s health depends on TPSAC being a viable, credible, and productive influential body of experts.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Thomas Eissenberg is a paid consultant in litigation against the tobacco industry and also the electronic cigarette industry and is named on one patent for a device that measures the puffing behavior of electronic cigarette users and on another patent for a smartphone app that determines electronic cigarette device and liquid characteristics.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data for this investigation are available at https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/committees-and-meeting-materials/tobacco-products-scientific-advisory-committee.

Table 1. Process Questions Posed to TPSAC by the FDA from 2010 to 2019 (n = 16 meetings).

ulgm_a_1868938_sm6986.docx

Download MS Word (50.4 KB)Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 U.S. Dep’t of Health, Education, and Welfare, Smoking and health: Report of the Advisory Comm. to the Surgeon Gen. of the Public Health Service, 97-126 (1964), https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/101584932X202.

2 Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act §5, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1331-1341 [hereinafter FCLAA].

3 Id. at § 1336.

4 Id. at § 1341(a).

5 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Pub. L. No. 111-31, 123 Stat. 1776 (2009) (codified as 21 U.S.C. §§ 387-387u.) [hereinafter FSPTCA].

6 Id. at § 387a.

7 Id. at § 387q.

8 Id. at § 387g(e).

9 Id. at § 387g(f).

10 Id. at § 387q(c).

11 Id. at § 387k(f).

12 Id. at § 387g(d).

13 Id. at § 387b(2).

14 U.S. Food and Drug Admin., Charter of the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (Sept. 10, 2012), https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/tobacco-products-scientific-advisory-committee/charter-tobacco-products-scientific-advisory-committee.

15 FSPTCA 21 U.S.C. § 387q(b)(1).

16 Id. at §§ 387g(e)(2), 387(f)(2).

17 Id.

18 Lorillard, Inc. v. United States FDA, 56 F. Supp. 3d 37 (D.D.C. 2014).

19 See U.S. Food and Drug Admin., Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (current as of Nov. 12, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/committees-and-meeting-materials/tobacco-products-scientific-advisory-committee [hereinafter TPSAC].

20 Id.

21 Lorillard, supra note 18.

22 Statement from FDA Director of the Center for Tobacco Products Mitch Zeller (Mar. 5, 2015). https://web.archive.org/web/20150418201511/https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/NewsEvents/ucm436783.htm?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

23 Id.

24 See meeting rosters available at TPSAC, supra note 19.

25 FSPTCA, 21 U.S.C. § 387q.

26 FSPTCA, 21 U.S.C. § 387g(d)(5).

27 U.S. Food and Drug Admin., Harmful and Potentially Harmful Constituents in Tobacco Products and Tobacco Smoke: Established List (Apr. 2012), https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/rules-regulations-and-guidance/harmful-and-potentially-harmful-constituents-tobacco-products-and-tobacco-smoke-established-list.

28 U.S. Food and Drug Admin., Reporting Harmful and Potentially Harmful Constituents in Tobacco Products and Tobacco Smoke under Section 904(a)(3) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; Draft Guidance for Industry, 77 Fed. Reg. 20030 (Apr. 3, 2012), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/04/03/2012-7766/draft-guidance-for-industry-reporting-harmful-and-potentially-harmful-constituents-in-tobacco.

29 Video: Chemicals in Cigarettes: From Plant to Product to Puff, U.S. Food and Drug Admin (2017), https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/chemicals-cigarettes-plant-product-puff.

30 Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations 225 (July 21, 2011), https://perma.cc/J875-9LBN.

31 Margaret A. Hamburg, M.D., Comm’r of Food and Drug Admin., Report to Congress: Progress and Effectiveness of the Implementation of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 15 (2013), https://perma.cc/4NL7-TWJV.

32 U.S. Food and Drug Admin., “Covered” Tobacco Products and Roll-Your-Own/Cigarette Tobacco Labeling and Warning Statement Requirements, 81 FR 28780 (May 10, 2016), https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/labeling-and-warning-statements-tobacco-products/covered-tobacco-products-and-roll-your-own-cigarette-tobacco-labeling-and-warning-statement.

33 FSPTCA, 21 U.S.C. § 387k(a).

34 FSPTCA, 21 U.S.C. § 387k(f).

35 U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Press Release: FDA Permits the Sale of IQOS Heating System through the Premarket Tobacco Product Application Pathway (Apr. 30, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-sale-iqos-tobacco-heating-system-through-premarket-tobacco-product-application-pathway.

36 Erik C. et al., A Philip Morris Advertisement for Its Heated Tobacco Product IQOS Sets a Troubling Precedent, Tobacco Control (2020, e-published ahead of print), doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055363.

37 U.S. Food & Drug Admin., supra note 35.

38 Kevin R.J. Schroth et al., Why an FDA Ban on Menthol Is Likely to Survive a Tobacco Industry Lawsuit, 134 Public Health Rep. 300 (2019).

39 The Federal Advisory Committee Act, Pub. L. No. 92-463, 86 Stat. 770 (1972) [hereinafter FACA].

40 U.S. Gen. Servs. Admin., Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) Management Overview, http://www.gsa.gov/faca.

41 FACA, 86 Stat. 770, § 14(a)(1)(b).

42 U.S. Food and Drug Admin., supra note 14.

43 FACA, 86 Stat. 770 § 4(a).

44 FACA, 86 Stat. 770 § 10(f).