ABSTRACT

Conversational robots and agents are being designed for educational and/or persuasive tasks, e.g., health or fitness coaching. To pursue such tasks over a long time, they will need a complex model of the strategic goal, a variety of strategies to implement it in interaction, and the capability of strategic talk. Strategic talk is incipient ongoing conversation in which at least one participant has the objective of changing the other participant’s attitudes or goals. The paper is based on the observation that strategic talk can stretch over considerable periods of time and a number of conversational segments. Film dialogues are taken as a source to develop a model of the strategic talk of mentor characters. A corpus of film mentor utterances is annotated on the basis of the model, and the data are interpreted to arrive at insights into mentor behavior, especially into the realization and sequencing of strategies.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

One function that has always been seen as a prerequisite for conversational agents and companion robots for long-term use is the capacity to bring about and/or support behavior and attitude change. Studies on long-term relationships with companions, either virtual or embodied as robots, regularly are based on scenarios of health-related counseling, coaching, or monitoring, often with a view to the potential of these technologies for active assisted living for an aging population: physical training (Bickmore, Schulman, and Langxuan Citation2010), weight loss (Kidd Citation2008), therapy compliance (Anderson and Anderson Citation2015), etc. Similar challenges arise for educational robots and agents as soon as they are supposed to motivate and foster substantial long-term learning processes. Persuasion, however, understood as bringing about a change of attitudes and objectives in the human counterpart, is rarely a short, one-step process, especially when it addresses lifestyle and lifelong habits.

Our research focuses on the identification of such strategies, with a view to modeling and generating strategic interaction. As it is hard to come by natural conversational data of long-term strategic talk, we turned to films in which relationships are contained and compressed within the diegesis. An obvious case of strategic talk in film is the relationship between mentor and hero/ine. The price we have to pay for this choice is the undisputed artificiality of film dialogue, in which the effect of talk on the participants is imagined by the screenwriter and only one of the functions of the dialogue. Kozloff (Citation2000) points out the role of dialogue in film beyond its diegetic functions: it explains the world of the film and the characters’ backstory to the audience, and gives meaning to what they see on the screen. Strategic talk in film need not “prove” to be effective in educating or persuading because the plot advances anyway, following the screenwriter’s and the director’s intentions. For all its artificiality, however, screen dialogue follows the fundamental logic of conversation (Grice Citation1975) to be comprehensible and believable to the audience.

The starting point of our research work was therefore the simple question: how is mentoring done in film? Is it possible to identify distinctive strategies, and in which way, if at all, are they related to their verbal realization in dialogue? In the broader context of our research into the generation of strategic dialogue, the analysis should also provide evidence and methods of sampling “good” and “bad” mentoring.

Modeling Mentor Interaction

Mentor Characters in Film

Our definition of mentor characters is broad, including all types of characters who at some point recruit, teach, guide, or otherwise prepare the hero for his mission or quest. Mentors are important supporting characters in films (Vogler Citation2007; Lynn Schmidt Citation2001) not least because many screenwriters tap into old popular myths and story elements (Campbell Citation2008; Propp Citation1968). The classical mentor in the guise of old man/old woman is therefore frequently found in films with fantasy elements (fairy tales of course, but also science fiction and horror movies), but there is a crowd of mentor characters also in realistic genres.

The mentor is characterized by knowledge, experience, superior force or skills, age, discipline (he adheres to the cause), knowledge of the future (the quest, the mission) and of immediate threats (urgency). HeFootnote1 derives power from his superiority. The mentor’s power is often not only his own, but handed down by a superior (magical or abstract) power, an institution (the mentor as teacher, officer, superior etc.) or business (the mentor as manager, editor-in-chief, supervisor, boss, etc.). The main distinction to be made is the answer to the question: who seeks out whom?

The Mentor as Seeker

There are mentors who search for the hero-to-be, call him to adventure and initiate or support his departure from the ordinary world (Campbell Citation2008).

The dilemma of the mentor in the role of a seeker is that, with all his power and knowledge, he needs the mentee, who is (to become) the hero/ine of the story. The quest is such that the mentor cannot fulfill it himself, and the reasons for this may or may not be given in the story. For example: the mentor is too old, feels death approaching, there is a superior rule that hinders him; the mentee has some special quality or capability that the mentor has not. The mentor’s dilemma will be manifest in the interaction: on the one hand, he has to gain the mentee’s trust and must empower him so that the mentee accepts his mission and sets off on the quest; on the other hand, the mentee should accept the mentor’s authority, at least long enough to learn what he needs for the quest.

The mentee in this setting is usually young, inexperienced, and lives his ordinary life. The mentee is surprised and reluctant to take on the quest. He wants to stick to the ordinary world out of habit, fear, or inertia, and resists being called to adventure. He may be shy and lack self-assurance; or else he may be too self-assured, but for the wrong reasons or qualities. The mentee may be eager to start the quest because of boredom or a vague desire to change his life, or else he may be satisfied with his everyday life and unwilling to give it up. There is, however, always an underlying desire or need which make the mentee (finally) accept the quest, be it love, ideals, money, or some lack of which he is, initially, not even aware (Vogler Citation2007).

The Mentee as Seeker

Here, the hero has already started on his quest, maybe called to adventure by another character (but more often by events, or crises). He is in search of help, guidance, access, training, or simply a job. In this case, it is the mentor who is, at first, unwilling, even threatening, and demands proof by the hero that he is worthy. The mentee is self-assured but may over-estimate his skills and/or underestimate the danger. Motivations of the mentee include revenge, bad experiences, search for identity and personal development, money, power, boredom or dissatisfaction with ordinary life, professional ethics, or orders from higher up.

The task of the mentee in the interaction is to make the mentor accept him as mentee. He tries to motivate the mentor by showing his worthiness, convincing him of the importance of the quest, or by pointing to possible reward. The mentee is also in a dilemma, but a smaller one: he has to show the mentor respect while at the same time convince him of his own qualities.

The mentor may not be interested and reluctant to take on the mentee. He demonstrates his freedom of decision and displays his power to select or refuse the mentee. He tests the qualities of the mentee that are relevant to the quest. The reasons why the mentor accepts the mentee include the mentee’s personality, compassion, shared objectives (e.g., revenge or money), dissatisfaction with his ordinary life, or his values.

Strategic Talk

Strategic talk is goal-oriented, as opposed to casual conversation. Other types of goal-oriented talk are:

Task-oriented talk, where both (all) participants pursue the same goal. Possible negotiation of this goal lies outside the situation under observation. The overall shared goal does not preclude that single steps, sub-goals etc. have still to be negotiated, while the overall attitude is cooperative.

Negotiation, where both (all) parties have differing goals which pre-exist the situation under observation and do not change over the course of the conversation. Although the meta-objective of reaching a favorable deal is shared by the participants, this means something different for each of them.

Both task-oriented talk and negotiations are, in principle, symmetric. Strategic talk, by contrast, is characterized by its asymmetry: both participants may have different goals at the outset, as in negotiation, but one of them is made to change his/her goal to adopt the other’s goal (cf. Habermas Citation1999, vol. I, p. 131). It can include persuasion, manipulation, education, and argumentation to different degrees and at different times. Asymmetric talk in institutional settings, e.g., doctor–patient or teacher–student, are strategic if one participant pursues the goal of bringing about a change of attitude, goals, and behavior in the other.

People need time to change. Even in the diegesis of film, where an epoch can be compressed to 90 min screen time, people do not change from one moment to the next. Strategic talk proceeds in segments of “continuing states of incipient talk” (Schegloff and Sacks Citation1973). Strategic talk is best viewed as a series of conversations marking different stages of goal pursuit and achievement. The active or dominant participant will have specific subgoals and corresponding strategies for each segment which have their logical place in the sequence of exchanges, much like a curriculum or agenda. This study is based on the assumption that mentors in film, too, use different strategies to achieve their goal. It was clear, though, that mentoring in film bears hardly any relationship to mentoring as it is contemporaneously understood and practiced in real life.

Data and Method

To identify these strategies, we chose a data-driven qualitative approach based on Grounded Theory methods (Corbin and Strauss Citation2008). Our data sources for this stage are the Walker, Lin, and Sawyer (Citation2012) corpus of dialogue extracts from over 1000 movies, as well as IMsDB (Internet Movie Script Database) and IMDB (Internet Movie Database). Mentor characters were identified through popular lists (e.g., “50 best mentors”, http://www.shortlist.com/shortlists/best-movie-mentors) and through a search for user-generated tags of IMDB film descriptions.

From the corpus, we then extracted dialogues between mentors and their mentees (= the hero/ine), starting with their first encounter and adding consequent scenes where necessary. This collection of 63 dialogues from 45 films were annotated with free text, i.e., paraphrases, descriptions, and other observations. These open descriptions were progressively condensed and abstracted into concepts and categories. The categories were refined and modified by testing them on the annotation of additional mentor-mentee-dialogues, until they were found sufficient for covering any new dialogue. The use of three descriptive levels—dialogue acts, moves/themes, and strategies—was found to be necessary to achieve coverage of the data and sufficient distinction between mentor behaviors.

Moves, Themes, and Dialogue Acts

On the assumption that film dialogue can reveal mentoring strategies, we adopt a perspective which foregrounds dialogue as action, which in turn raises the question of defining action-based units of discourse. In accordance with the screenplay as a dramatic text, our concept of action is inspired by the (late) Stanislavski “Method of Physical Action” (Sawoski Citation2010) for actor training and rehearsal. Stanislavski defined a “unit” as a portion of a scene in which an actor pursues a single objective through his/her action. For Stanislavski, the through line of a character is a coherent string of actions, each which its objective, held together by an overarching “superobjective” which constitutes the spine of the character. These superobjectives are what we call “strategies” in our model, while each unit with an identifiable (sub)objective is called a “move”. The move in turn is linked to the realized dialogue act.

With a view to automatic classification, we use a simplified set of dialogue acts:

Statement (S),

Wh-question (WH),

YN-question (YN),

Command (C),

Interjection (I): a broad category of short non-elliptic utterances, such as responses, backchannels, interjections, discourse particles, etc.; all infrequent in written dialogue.

The move as a unit of discourse does not necessarily coincide with dialogue act boundaries, as one move can stretch over several utterances, and vice versa. Technical reasons, namely the existing format of the extracts and the intended use of the data for utterance-level classification and clustering, made it necessary to annotate moves on the utterance level. Our concept of move therefore is a second-level dialogue act annotation which can, for example, account for indirect speech acts. However, sequences of identical moves remain accessible in the data as coherent chunks and allow for the qualitative analysis of moves beyond the utterance level.

Our catalogue of moves was developed on the basis of Tsui (Citation1994) who in turn draws on Sinclair and Coulthard (Citation1975). Tsui’s field of study is tutoring dialogue, more specifically classroom exchanges. The set of moves was therefore not completely adequate for our film dialogues, and had to be adapted to fit our data better. Moves, by denotating action with regard to the enacted strategy, link the surface level of dialogue acts to the higher order strategies.

We reduced the number of moves, for example by collapsing the fine-grained distinction between types of requests and directives, because these distinctions cannot easily be made in film dialogue. Likewise, the four-part-structure of the exchange observed by Tsui (Citation1994), with two follow-ups, is not present in film dialogue. The dogma of screenwriting to use as little dialogue as possible (Kozloff Citation2000; Jaeckle Citation2013) leads to unnatural shortcuts where much of conversational behavior such as backchannels and discourse particles is realized visually (gaze, facial expression of the actor, etc.). On the other hand, we added three move types, namely social, evaluative, and narrative, which emerged from our data as distinctive actions of mentors.

The final list of moves is the following. For most types, the class of a move can be tested with the way the utterance would be reported in indirect speech:

Social (S): utterances primarily oriented toward the relationship, e.g., greetings, jokes, expression of emotion, introductions, farewell, swearing, expressions of power/submission.

Assertion (A): information-oriented; teaching, rule, information, report, “words of wisdom”; test: “tell that.”

Elicitation E: request for information, or confirmation, test: “ask if”, “ask wh-.”

Directive (D): command, order, advice, threat, warning, instruction, request; test: “ask to”, “tell to.”

Evaluative (V): assessment, value judgment of the other or the other’s actions; test: “tell how.”

Narrative N: story, coherent sequence of utterances; test: “tell about.”

Response (R): any response that does not constitute itself one of the above moves; follow-up in a turn sequence, dependent move; can be positive = R1, negative = R0, or undecided (e.g., “don’t know”) = R2.

In addition to moves, it turned out necessary to annotate for themes, i.e., what the move is about, to introduce an additional feature for the differentiation of moves:

Mentor (M): moves about the mentor himself, e.g., biography, feelings,

Pupil (mentee, hero/ine) (P): moves concerning the mentee, e.g., biography, personality, behavior,

Quest (Q): everything that has to do with the (future) mission, role, or quest,

Other (O): any other theme.

Strategies

The data-driven approach to mentor characters’ strategies resulted in the following set:

Social relationship building S: Mentor and mentee have to establish rapport; the initiative for this usually lies with the character who seeks out the other. Relationship-building remains a by-strategy throughout the interaction. In fact, every utterance in a conversation has also a function in establishing and maintaining the relationship, status, or closeness. The relationship between mentor and mentee is usually characterized by the higher status of the mentor as older, wiser, more experienced, and/or equipped with power through the institutional context (e.g., military rank) or through another higher (e.g., magical) authority, see “The mentor as seeker”. The mentor’s relationship building strategy includes conventional politeness as well as swearwords and affirmations of power, as illustrated by the following examples:

(98) Shake hands and let your emotions go.

(141) Congratulations.

(1223) Agent Myers, this is Agent Clay.

(2927) The first and last words out of your stinking holes will be sir.

Empowerment E: The pro-active mentor singles out the mentee as predestined, specially gifted, etc. He has to convince the mentee that he is the “chosen one”, the right person to do the job, and that he has the abilities to perform. Shy or modest mentees need to be convinced that they are able to acquire the skills necessary for the quest, and all need further encouragement during the training,

(399) I’ve searched the entire world for you, Buffy.

(1486) The universe has brought us the Dragon Warrior!

(2177) You are here because you have the gift.

(2477) There are some who believed you would fail, but I knew you would not.

Testing T: Especially when the mentee seeks out the mentor, the mentor will test the mentee’s capacities and resolve, but the pro-active mentors also put the mentee to sometimes harsh tests. Hard testing is often a strategy of the mentor in a role of threshold guardian. While the (future) hero passes the test, the high chances of failure can be illustrated by third characters (e.g., the “other” recruit who drops out of training). Testing can alternate with instruction, and the passed test is a reason for (further) empowerment of the mentee,

(207) Those who I deem unworthy to pass through this camp will quit, and those who refuse to quit I will kill.

(607) Have you mastered the threefold transmutation?

(3664) Could you jump from that tower to that roof?

(2457) This is your first test.

Instruction I: Once the mentee is found worthy and/or has proven to be the chosen one, real training starts. Many films, however, start with an existing mentor-mentee relationship, and we find them in the middle of training (e.g., Dragonslayer, Blade). While instruction in physical skills is obviously not well represented in dialogue, the mentor always has other things to teach as well. He can give the mentee (and the audience) insights into the backstory, and he often delivers some “words of wisdom”, proverbs or proverb-like general assertions and mottos. In the hands of mediocre screenwriters, these mottos can border on the trivial. Often a separate training phase is only hinted at in the film, or cut short by the events. Training then continues “on the job”, so that training merges with instructions given by the mentor as leader in action,

(73) Physical labor keeps us humble.

(1571) The true path to victory is to find your opponent’s weakness and make him suffer for it.

(1798) You must look into the eyes of your enemy to know who you have killed.

(2319) Consider this your first lesson.

Selling the Quest Q: The mentor has to motivate the mentee to adopt the quest, role, or mission, for which he is foreseen. The mentor can appeal to the mentee’s values, relationships, ambition, or other needs, to bring about the intended change in the mentee. At this key point, events or signs often come to the aid of the mentor, but he still has to give these events meaning for the benefit of the mentee. It is not always easy to detect from the first reading of a screenplay what the quest will actually be: it can be victory over antagonistic forces to save the world, revenge, survival, an ingenious act of espionage or theft, etc., but these can turn out to be only the visible/action component of the adventures through which the real quest is achieved, e.g., the personal development of the hero’s character. Furthermore, not all mentors are “good guys”, and the real task of the hero may be to liberate himself from the mission defined by the mentor (e.g., Ninja Assassin). The quest that the mentor promotes therefore need not be what the movie ultimately is about,

(52) I grew up on the stories of the Shaolin, and you can be those stories.

(309) There’s a war going on out there.

(903) We have to save the world.

(1636) He is coming for the Dragon Scroll, and you are the only one who can stop him.

Resist R: Both the mentor and the mentee, depending on who is the initiator of the interaction, can and often do resist the call to adventure,

(3685) What the hell was Eli thinking, giving me a smart-ass, cocky, amateur kid when I need a stunt man!

(3893) You should never have come to this place!

(1504) You are not the Dragon Warrior.

(3543) My own counsel will I keep on who is to be trained!

Model of Mentor-Mentee Interaction

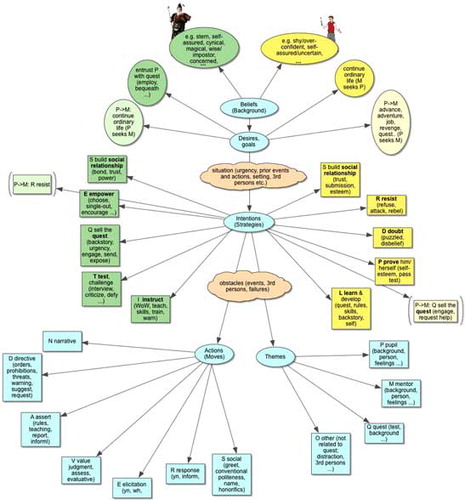

We developed and tested a BDI-inspired model for both mentor and mentee in interaction, taking into account that both participants contribute to the execution of mentoring strategies. The illustration of the model in shows the strategies of mentee and mentor for both cases of initiative (mentor seeks mentee vs. mentee seeks mentor). This model is static, i.e., it does not take into account the sequence structure of the interaction and the alternation of moves between mentor and mentee (the mentee is labeled “pupil” in what follows for better distinction).

Interpretation of the Annotated Data

Annotation and Description of Data

From the corpus of screenplay dialogue lines (Walker, Lin, and Sawyer Citation2012), we randomly selected 25 films with mentor characters and extracted their utterances (see Annex). Out of the 4000+ lines, 3383 were usable for annotation, representing 28 mentor characters. These utterances were annotated by two persons for grammatical features (person, tense), dialogue act type, move, theme, and strategy. Only for strategy more than one label were allowed, to reflect the fact that speakers often pursue more than one strategy with one and the same move. Most often, a double annotation labels a move as relationship-related (S) in addition to any other strategy. Annotation was done taking the whole screenplay as a reference to provide context. Inter-rater reliability was tested with 60 lines extracts from three screenplays which were cross-annotated by both annotators. Cohen’s Kappa is substantial for person, tense, dialogue act and move (>0.6), moderate for theme (0.43), and fair for strategy (0.37). An inspection of the annotations showed that the low inter-rater reliability for strategy was mostly caused by mismatches of the strategies I and Q (instruction and Selling the quest): this is due to the difficulty to identify the quest or quests at the first reading of a screenplay (see “Strategies”).

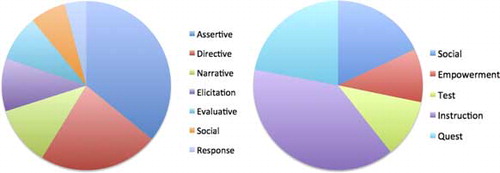

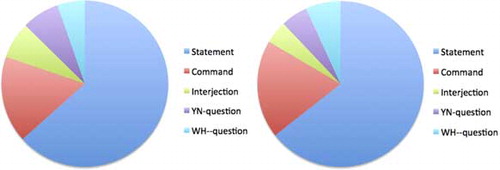

The number of utterances per mentor character ranges from 24 to 284, with an average of 120 and almost half of the characters (13) having between 100 and 155 utterances. The results for dialogue acts show the expected strong prevalence of statements, with commands coming in as second most frequent type. The distribution of dialogue act types does not deviate from what we could establish as the normal range through previously annotated samples and screenplays (Skowron et al. Citation2016). In , the distribution of dialogue acts for a complete film dialogue (Avatar) is shown alongside the distribution for the current sample of 28 mentors.

Figure 2. Distribution of dialogue acts: 28 mentor characters sample (left), Avatar screenplay, all characters (right).

On the level of moves, the predominance of statements is carried over into the relative frequency of assertive moves. Statements are also used for nearly all other move types, most obviously for narrative moves, but also as directives and evaluative. The different ways in which instructions can be given are reflected by the result that only 73% of directives are formulated as commands. The most frequent theme in the mentors’ utterances is the mentee, followed by the quest, i.e., the mission or task in the story. The proportion of all “other” themes taken together turned out to be smaller than expected.

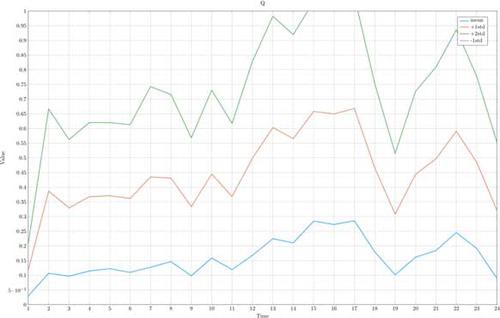

shows that instruction is the most frequent strategy, in line with the core function of the mentor as a teacher/trainer. Social relationship building is also frequent but often, as noted above, annotated as a by-strategy. We find not much evidence of resistance strategies, which is not unexpected given that our sample contains few cases of unwilling and reluctant mentors.

Relationships Between Dialogue Acts, Moves, and Strategies

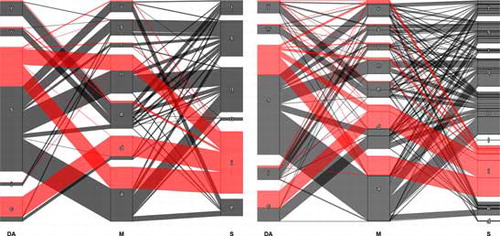

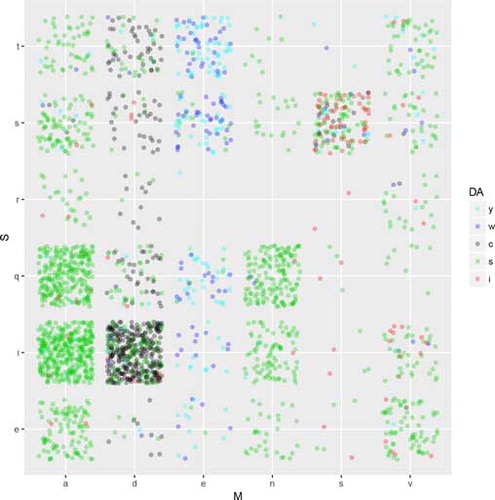

Although we did not expect straightforward links all the way from dialogue acts to strategies, we examined whether there are patterns of co-occurrence. shows the co-occurrence map of moves and strategies, with dialogue act classes coded by the dot colour.

Figure 4. Relationship between moves, strategies, and dialogue acts. S (strategies): t(esting), s(ocial relationship), r(esistance), q(uest), i(nstruction), e(mpowerment); M (moves): a(ssertive), d(irective), e(licitation), n(arrative), s(ocial), v(alue = evaluative); DA (dialogue acts): y(y/n-question), w (wh-question), c (command), s (statement), i(interjection).

Given our definition of moves that remains close to the level of dialogue act classification, we find obvious co-occurrences between dialogue acts and moves: elicitation moves are predominantly performed as YN/WH-questions. Over 95% of commands are used to perform directive moves. More than half of statement type dialogue acts are assertive moves, with narrative, evaluative, and directive moves accounting for most of the other half. As to the relationship between moves and strategies, the plot shows, not surprisingly, a strong overlap of social move with the relationship-building strategy. The correlation between commands and directive moves is carried onward into the instruction strategy: 58.9% of commands are used in instruction. The plot also shows that a major part of narrative moves serves for “selling the quest”. 17.6% of all utterances of the statement type are narrative moves. For both the themes and the strategies they are used in, we find that the quest and “selling the quest” to the mentee account for nearly half of these moves.

Use of Strategies Over Time

For insights into the mentoring process, it is of interest to know whether the strategies are used simultaneously or in sequence. The model of the mentoring process () is, in principle, ignorant of any chronological order, although commonsense would interpret it as also representing a logical sequence of actions.

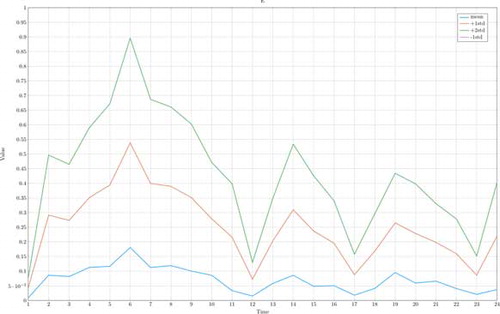

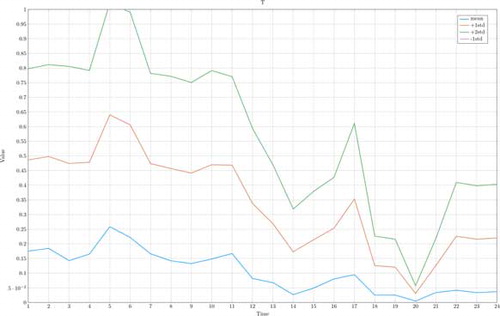

The distribution of all mentors’ utterances over time (, , and ) does not account for the “real” timeslot in the film where the mentor character actually appears. Despite this bias, the plots indicate that some strategies have a preferred slot in the lifetime of the mentor-mentee-relationship: empowerment and testing tend to come early, while talk about the quest is delayed.

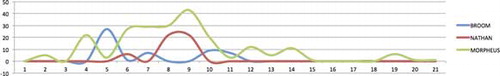

For three mentor characters (Morpheus, Nathan, and Broom; see annex for list of characters and films), we also compared presence and strategies over (real) film or screenplay time. To do this, we considered the whole text of each screenplay individually, segmented it, and then allocated the mentor character’s annotated utterances to its timeslot in the screenplay. The timeline comparison shows that they are active only or mostly in the first half of the movie. Their activity is concentrated between units 4 and 10 on a timeline of 20 segments, see . Typically, the part of the movie before the mentor’s appearance shows the hero/ines in their ordinary lives and introduces the problem, often in parallel storylines, with the appearance of the mentor marking the first main plot point, cf. Skowron et al. (Citation2016). At the end of the character’s presence, the mentor often dies or disappears, but even if he lives on, like Morpheus, his activity is reduced.

Comparison of Mentor Characters

For the purpose of validating the model of the mentoring process, the overall results are less relevant than a comparison of mentor characters with a view to refining the model for different mentor types. One of our questions was therefore which mentor characters in our sample best reflected the model. In our definition, the ideal mentor would display all the main strategies. To answer this question, we developed a ranking method based on the proportion of utterances dedicated by each of the 28 characters to each of the main strategies (E, T, I, S, and Q). We then corrected the rankings by subtracting the standard deviation between individual strategy rankings, to reflect our ideal case of balanced use of the relevant strategies. Column 4 in the list of mentor characters in the Annex contains the resulting rank.

The top three mentor characters are Morpheus (The Matrix), Ramirez (Highlander), and San De (American Shaolin). Morpheus is also the mentor character with the most utterances, but the other two characters, with 111 and 134 utterances respectively, are in mid-range (average: 120 utterances) and show that the ranking does not depend on the overall importance of the character in the screenplay. Low-ranking characters are written to play only one part of the mentor role, sometimes sharing aspects of mentoring with a second supporting character (e.g., Oogway and Shifu in Kungfu Panda, or Zim and Rasczak in Starship Troopers). Another reason for low rank is that some characters change roles over time, to leave mentoring behind and to become friends, companions, or followers of the mentee/hero (e.g., Proximo in Gladiator). Other films set in with pre-existing mentor-mentee relationships so that the audience is led to assume that important aspects of strategic mentoring, i.e., changing the mentee’s goal, have been dealt with at some earlier point in time (e.g., Ulrich in Dragonslayer, Whistler in Blade).

To assess the relations between the annotated features, the Mutual Information scores were calculated for the set of labels in the dialogue acts, moves, themes and strategies categories. The abbreviations are composed of a capital letter for the class type (DA = dialogue act, M = move, T = theme, S = strategy) and a lowercase letter for the categories within the class (see “Moves, themes, and dialogue acts”)

For the most typical mentor character Morpheus (set “M”) the strongest relation between the labels from different categories indicate a typical realization of Move directive with Dialogue Acts: command (0.38) and statement (0.23). Move narrative is most frequently related to the Themes: pupil (0.21) and quest (0.17). The Strategy quest is, as expected, most strongly anchored in the Theme quest (0.15), while Strategies empower and social relationship relate to Moves value (0.18) and social (0.16) respectively.

When considered jointly, the three archetypical mentors Morpheus, Ramirez, Katsumoto (set “A”), provide an additional evidence on the typical realizations of the Move directive with the Dialogue Acts: command (0.34) and statement (0.17) and the role of Theme quest in the Strategy quest (0.16). When analyzed jointly the three archetypical mentors, the most typical realization of the Move empower is with the Dialogue Act YN-question (0.16).

visualizes the connections between dialogue acts, moves, and strategies for the set of three archetypical mentors “A” and the set of the remaining 25, “nA”. In each diagram, the links for the instruction strategy are highlighted. The more balanced distribution of strategies in the left diagram confirms the ranking. The ranking method ignores the strategy O (other) where a considerable difference between the groups appears in the diagrams, hinting at a “more focused” mentoring behavior of the “A” mentors. The stronger use of narrative moves by the “A” group is also a result that is independent of the ranking.

Discussion of Results

Different methods are used to interpret the annotated data to answer several research questions. One objective was to explore to what degree dialogue act recognition combined with grammatical and positional information allows to predict the strategies that mentor characters apply to reach their goal of influencing and teaching the film mentees. In particular, we examined the co-occurrence of dialogue act types with move types, and of these with strategy types. Results are satisfying for the dialogue act type “command”, but the degree of ambiguity for other categories is high.

The time-dependent interpretation of the data shows preferences for occurrence and sequencing for the strategies testing, empowerment, and selling the quest. This results hints at a possible difference between the classes of strategies as postulated by the model, i.e., that instruction and relationship-building are not or less subject to sequencing of strategies. This hint will be followed up in qualitative analyses of individual mentor characters’ application of strategies.

The ranking and comparison of mentor characters indicates some behavioral features of archetypical mentors, namely use of narrative and task-focused interaction. The primary purpose of this exercise is to get a basis for further more detailed analyses, e.g., of the occurrence of story-telling.

It is obvious to any student of dialogue and discourse that our study so far lacks the most important ingredients, namely the other participant and the interaction. A detailed study of mentor-mentee interactions will have to be limited to selected segments. The explorative study presented in this paper has provided insights into the data that puts this selection on a firm basis and generates specific questions for further research.

Related Work

The availability of vast numbers of screenplays has inspired a number of studies on style and character. Methods developed and evaluated on non-fictional texts were also applied to the analysis of fictional dialogues (Kundu, Das, and Bandyopadhyay Citation2013; Gorinski and Lapata Citation2015; Shen Citation2011; Karsdorp et al. Citation2015). Although limited to linguistic style analysis, Walker et al. (Citation2011) showed that the detection of some of the communicative patterns and linguistic features of a character can be achieved (Walker et al. Citation2011). Specifically, the published approach relied on a set of linguistic features, aggregated and extracted jointly from all dialogues a given character conducted, without differentiating conversational partner, point in the dramatic arc, or narrative relevance. Lee and Marsella (Citation2011) provide an analysis of nonverbal behaviors in interactive drama associated with side participants and bystanders in multiparty interactions and construct an analysis framework incorporating characters’ interpersonal relationships, conversational roles and communicative acts. Their set of conversational roles includes: speaker, addressee, side participant and bystander. The relationships between characters are described in terms of dominance and friendliness, the communicative acts extend beyond the dialogue acts of character utterances to include events that may evoke emotional responses from the characters. Bamman, O’Connor, and Smith (Citation2014a) take as data the plot summaries of movies, plus metadata about films (genre) and actors (gender, age) from wikipedia.org.

Using an extension of the latent Dirichlet allocation, Bamman, O’Connor, and Smith (Citation2014a) obtain shared multinomial distributions estimated on actions of characters, actions done to characters, and attributes. The assignment of a character’s actions, received actions and attributes are used to describe the latent persona of a character. In Bamman, Underwood, and Smith (Citation2014b), narratives extracted from a large collection of novels are used for the modeling of characters. In Skowron et al. (Citation2016) action movies character types are analyzed and classified using an integrative approach that complements linguistic analysis with interactive and communication characteristics. Selected aspects of the interactive characteristics of fictional characters are captured by the descriptive analysis of semantic graphs weighted by linguistic markers of expressivity and social role.

The challenge of designing virtual characters (ECAs) and robots for long-term companionship has persisted in the field since Bickmore (Citation2003). It is accepted that such companions should, as one important functionality, be able to coach and influence their users with regard to health and fitness. Research toward this objective was done by Kidd (Citation2008), Anderson and Anderson (Citation2015), Bickmore, Schulman, and Langxuan (Citation2010), Sloman (Citation2010), von der Puetten, Kraemer, and Eimler (Citation2011), Payr (Citation2013), and many others, most with a focus on the building and maintaining of social relationships as a prerequisite for long-term use, e.g., Cassell and Bickmore (Citation2003). In the field of persuasive technologies in general and agents in particular (e.g., Narita and Kitamura Citation2010; Pickard Citation2012), the specific challenges of long-term persuasion have been recognized more recently and begin to be addressed (e.g., in Fritz et al. Citation2014 or Yoshii and Nakajima Citation2016). While numerous models of persuasion, coaching, or mentoring do exist, there is a lack of studies on recurring strategic talk as it naturally occurs in series of tutoring or coaching sessions. Studies of coaching discourse (e.g., Engstrand and Vesterberg Citation2011; Nielsen and Norreklit Citation2009) are based only on secondary sources, namely interviews with coaches and coaching manuals, respectively.

Summary and Outlook

A data-driven model of mentor-mentee interaction and their strategies is developed and tested with an annotated corpus of mentor utterances extracted from screenplays. The corpus is analyzed for typical mentor behavior in terms of the application of all strategies and over time, and for relationships between the levels of descriptions. The results will be used for further qualitative interpretation of the data, and for sampling of mentor behavior with a view to behavior and dialogue generation. Additionally, the present results will be examined for relationships with a typology of mentor characters which is currently being developed based on visual and secondary textual data. The present model of mentor-mentee interaction is strictly data-driven and applies only to the domain for which it was developed. No claims to any relationship of the model with real life mentoring, coaching or other strategic talk are being made. The portability of the methods to naturally occurring strategic talk, and in particular to talk-in-interaction, will be examined in future research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1In most of this paper, we will refer to both mentors and mentees with male pronoun forms. This reflects the plain, if deplorable, fact that most of these characters are indeed male. Besides, “mentor”, being the name of a—male—character in the Odyssey, has no female form.

References

- Anderson, M., and S. L. Anderson. 2015. Case-supported principle-based behavior paradigm. In A construction manual for robots’ ethical systems, ed. R. Trappl, 155–68. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Bamman, D., B. O’Connor, and N. A. Smith. 2014a. Learning latent personas of film characters. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, vol. 1, 352–61. Association for Computational Linguistics: Sofia, Bulgaria.

- Bamman, D., T. Underwood, and N. A. Smith. 2014b. A bayesian mixed effects model of literary character. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, vol. 1, 370–79. Association for Computational Linguistics: Baltimore, Maryland.

- Bickmore, T. 2003. Relational agents: effecting change through human-computer relationships. PhD. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Bickmore, T., D. Schulman, and Y. Langxuan. 2010. Maintaining engagement in long-term interventions with relational agents. Applied Artificial Intelligence 24 (6):648–66.

- Campbell, J. 2008. The hero with a thousand faces. Novaro, CA: New World Library.

- Cassell, J., and T. Bickmore. 2003. Negotiated collusion: Modeling social language and its relationship effects in intelligent agents. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 13 (1):89–132.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Engstrand, A-K., and V. Vesterberg. 2011. Job Coaching: A Discourse Analysis. In Proc. 7th International Critical Managment Studies Conference, Naples, Italy.

- Fritz, T., E. M. Huang, G. C. Murphy, and T. Zimmermann. 2014. Persuasive technology in the real world: A study of long-term use of activity sensing devices for fitness. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, CHI ’14, 487–96, ACM, New York, NY, USA.

- Gorinski, P. J., and M. Lapata. 2015. Movie script summarization as graph-based scene extraction. In Proc. Human Language Technologies: The 2015 Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the ACL, 1066–1076. ACL: Denver, Coloarado.

- Grice, H. P. 1975. Logic and conversation, vol. 3, 41–58. New York: Academic Press.

- Habermas, J. 1999. Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. 3rd ed. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

- Jaeckle, J. 2013. Introduction: A brief primer for film dialogue study. In Film dialogue, ed. J. Jaeckle, 1–16. London, New York: Wallflower Press.

- Karsdorp, F., M. Kestemont, C. Schöch, and A. van den Bosch. 2015. The love equation: Computational modeling of romantic relationships in french classical drama. In Proc. 6th Workshop on Computational Models of Narrative CMN'15, 98–107. Dagstuhl Publishing: Schloss Dagstuhl, Germany.

- Kidd, C. D. 2008. Designing for long-term human-robot interaction and application to weight loss. PhD. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, School of Architecture and Planning, Program in Media Arts and Sciences.

- Kozloff, S. 2000. Overhearing film dialogue. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kundu, A., D. Das, and S. Bandyopadhyay. 2013. Scene boundary detection from movie dialogue: A genetic algorithm approach. Polibits 47:55–60.

- Lee, J., and S. Marsella. 2011. Modeling side participants and bystanders: The importance of being a laugh track. In IVA, 240–47. Springer: Reykjavik, Iceland.

- Lynn Schmidt, V. 2001. 45 Master characters. Mythic models for creating original characters. Blue Ash, OH: Writer’s Digest Books.

- Narita, T., and Y. Kitamura. 2010. Persuasive conversational agent with persuasion tactics. LNCS. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Nielsen, A. E., and H. Norreklit. 2009. A discourse analysis of the disciplinary power of management coaching. Society and Business Review 4 (3):202–214.

- Payr, S. 2013. Virtual butlers and real people: Styles and practices in long-term use of a companion. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Pickard, M. 2012. Persuasive embodied agents: Using embodied agents to change people’s behavior, beliefs, assessments. PhD. thesis. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/238634.

- Propp, V. 1968. Morpphology of the folk tale. American Folklore Society, 2nd ed. University of Texas Press: Austin, TX. http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/propp.pdf.

- Sawoski, P. 2010. The stanislavski system growth and methodology. http://homepage.smc.edu/sawoski_perviz/Stanislavski.pdf.

- Schegloff, E. A., and H. Sacks. 1973. Opening up closings. Semiotica 8 (4):289–327. http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/soc/faculty/schegloff/.

- Shen, Y. K. 2011. Identifying power relationships in dialogues. Thesis, MIT.

- Sinclair, J., and M. Coulthard. 1975. Towards an analysis of discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Skowron, M., M. Trapp, S. Payr, and R. Trappl. 2016. Automatic identification of character types from film dialogs. Applied Artificial Intelligence 30 (10):942–973.

- Sloman, A. 2010. Requirements for artificial companions: Its harder than you think. In Close Engagements with Artificial Companions: Key Social, Psychological, Ethical and Design Issues, ed. Yorick, Wilks, 179–200. John Benjamins: Amsterdam.

- Tsui, A. B. M. 1994. English conversation. Describing English language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vogler, C. 2007. The writer’s journey. Mythic structures for writers. 3rd ed. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions.

- von der Puetten, A., and N. C. Kraemer, and S. Eimler. 2011. Living with a robot companion - empirical study on the interaction with an artificial health advisor. 13th International conference on multimodal interaction ICMI, Alicante, Spain.

- Walker, M. A., G. I. Lin, and J. Sawyer. 2012. An annotated corpus of film dialogue for learning and characterizing character style. Proceedings of the Eight International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’12), 1373–78, Istanbul.

- Walker, M. A., G. I. Lin, J. Sawyer, R. Grant, M. Buell, and N. Wardrip-Fruin. 2011. Murder in the arboretum: Comparing character models to personality models. In 4th International Workshop on Intelligent Narrative Technologies, AIIDE 2011. Stanford, Palo Alto, CA.

- Yoshii, A., and T. Nakajima. 2016. Toward long-term persuasion using a personified agent, 122–31. Cham: Springer International Publishing.