Abstract

Social media and news use arguably contribute to the prevalence of contentious politics because individuals may express dissent through their social networks as they consume news. This study seeks to test whether individuals might be more open to political persuasion in this context, especially if they are exposed to political disagreement or discuss politics in a civil manner. Relying on survey data from the UK, results based on a moderated moderation model show that (a) social media news use predicts political persuasion on social media (direct effects) and, (b) discussion disagreement and civil reasoning moderate this relationship in two-way and three-way interactions.

Political communication in Western countries has grown increasingly contentious (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012; Meyer and Tarrow Citation1998; Tilly and Tarrow Citation2015) and many people feel less favorable toward their fellow citizens on the “other side” of social and political issues (Garrett et al. Citation2014; Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes 2013). Some have argued that social media have contributed to these social changes, suggesting that they make political disagreement (Halpern and Gibbs Citation2013; Papacharissi Citation2014) and counter-attitudinal information more visible and prevalent in the everyday lives of ordinary citizens (Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic Citation2015; Barberá Citation2014). In such an environment, some people are more likely to “dig in their heels” and close themselves off to the kinds of cross-cutting communication that might bring people together across social cleavages to discuss common problems and solutions (Mutz Citation2006).

At the same time, others have explored how social media make people more susceptible to the influence of others in their social networks (Bode Citation2016; Bond et al. Citation2012; Turcotte et al. Citation2015). In this research the focus has been on the social and communicative nature of attitude formation; persuasion is conceptualized as the outcome of cognitive reflection in response to discussion and exposure to news (e.g. Kim, Wyatt, and Katz Citation1999; Levitan and Visser Citation2009; Wood Citation2000). Although in online settings political communication may lead to less dependence on elite institutions for information, it also means that people are increasingly dependent on their networks for news and opinion (Benkler Citation2006). Therefore, a growing number of researchers have turned their attention to how socially mediated networks influence news consumption, political discourse, and political attitude formation (Feldman Citation2011; Glynn, Huge, and Hoffman Citation2012). Some scholars argue that exposure to debate and disagreement in this environment fosters democratic discussion (Halpern and Gibbs Citation2013; Papacharissi Citation2004). However, it remains less clear how the tone of discussion disagreement influences how open an individual is to political persuasion, particularly when people get their news on social media.

As an increasing number of adults, especially young adults, turn to social media for their news and information, understanding how political discussions make people more open to political persuasion on social media is key to understanding the nature of political contentiousness online (Gil de Zúñiga and Valenzuela, Citation2010; Ofcom Citation2015; Pew Research Center Citation2015). This study examines the specific conditions under which persuasion occurs in social media settings. Relying on a representative survey of adults in the United Kingdom, this study investigates the relationships among news use, political disagreement, civil reasoning, and political persuasion on social media. The findings suggest that persuasion in social media is most likely to occur when people engage in cross-cutting discussions in general; and when strong arguments are presented in a civil manner.

Literature review

Political news use and political persuasion

Without new information, people are unlikely to reconsider their opinions, and when it comes to politics, the news media are one of the primary sources of new information on which citizens rely (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). Political persuasion, or the reconsidering of one’s political attitudes based on exposure to new information, has been explored as attitude ambivalence (Levitan and Visser Citation2009), strength and consistency of one’s attitudes and opinions (Kim, Wyatt, and Katz Citation1999), and the tendency to change one’s mind based on information they come across in their social environment (e.g. Mutz, Sniderman, and Brody Citation1996; Wood Citation2000). Recent evidence suggests that political affairs news use can have direct and relatively strong effects on political persuasion (Diehl, Weeks, and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2016; Barker and Lawrence Citation2006; Feldman Citation2011; Ladd and Lenz Citation2008; Zaller Citation1992). Researchers have offered various explanations for direct effects. Individuals may follow cues from elites of their own parties (Feldman et al. Citation2012; Zaller Citation1992). They could be influenced by agenda-setting and framing by the news media (McCombs and Shaw Citation1972; Nelson, Oxley, and Clawson Citation1997). Other evidence suggests that news use can persuade people regardless of their partizan leanings (Feldman Citation2011). For example, recent research shows that favorable media coverage of a political candidate increases his or her public support and newspaper endorsements of candidates can change the degree of public support (Barker and Lawrence Citation2006). The association between political news use and political persuasion may not be dependent on political ideology to the extent previously suggested (Zaller Citation1992).

Political information on social media might have a particularly powerful influence on persuasion because, in social media formats, news is delivered alongside information about social traits and public opinion. For example, Diehl, Weeks, and Gil de Zúñiga (Citation2016) found a direct effect of social media news use on political persuasion among adults in the United States. Because social media rely on systems of social accreditation and recommendation, social media users may also be more likely to be persuaded through exposure to counter-attitudinal information (Messing and Westwood 2012; Turcotte et al. Citation2015). This is particularly the case when individuals have larger, more heterogeneous networks (Brundidge Citation2010). In networked spaces, individuals are often presented with conflicting considerations based not only on Partizan cues in the news media, but also on cues from their personal social contacts who posted the story (Bode Citation2016; Bond et al. Citation2012; Turcotte et al. Citation2015). Thus, political news use in social media environments presents users with overlapping and often conflicting dimensions of informational relevance (Kwon, Stefanone, and Barnett Citation2014). Social media news use becomes an ideal catalyst for exposure to new political information.

The potential diversity of information, mediated through social connections, could make people relatively more ambivalent and therefore more open to opinion change. Based on this literature, we predict a positive relationship between political news use on social media and political persuasion within social media.

H1: Social media political news use will be positively related to political persuasion on social media.

Social media for political information, political disagreement, and persuasion

People do not only encounter new information through the news media, but also through interactions in their social networks. Although scholars have long noted the importance of interpersonal networks for the diffusion of political information (Katz and Lazarsfeld Citation1955; Granovetter Citation1983; Gil de Zúñiga Citation2012, Citation2015), a new wave of scholarship has focused on the ways that online and offline social networks have become increasingly isomorphic (Rojas Citation2015; Rojas, Barnidge, and Abril Citation2016). Thanks to online social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter, which largely translated offline social ties onto online platforms, there is arguable more convergence in the makeup and composition of online and offline social networks (e.g. Brundidge Citation2010; Eveland, Hutchens, and Morey Citation2013; Lee et al. Citation2014; Heatherly, Lu, and Lee Citation2017). Thus, as the adoption and use of social media has become more widespread, they have grown in importance as sources of political information, not only from the news media, but also from personal social ties (Bond et al Citation2012).

The observation that social media have grown in importance as sources of political information is important because recent research shows that they may promote exposure to political disagreement, particularly among those who use these platforms for news (Heatherly, Lu, and Lee 2016; Kim, Hsu, and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2013; Lee et al. Citation2014; Lu, Heatherly, and Lee Citation2016; Mitchell et al. Citation2014). Both survey evidence and analysis of “big data” show that social media expose people to news stories from both sides of the political spectrum, with the result that social media users are exposed to a broader array of stories than they would be otherwise (Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic Citation2015; Barberá Citation2014; Barnidge Citation2015; Kim Citation2011). This happens, in part these studies argue, because social media users tend to have easy access to more diverse networks—and, consequently, they are exposed to a wider variety of opinions.

The growing trend toward increased exposure to political disagreement in social networks is important because encountering political difference makes political persuasion more likely (Gil de Zúñiga, Valenzuela, and Weeks Citation2016). As Huckfeldt, Mendez, and Osborn (Citation2004a) argue, social influence—that is, persuasion resulting from interpersonal interaction—is less likely if individuals only encounter information with which they already agree. Potentially, this process occurs because political disagreement has the capacity to make people more ambivalent about their prior attitudes and preferences, and this ambivalence makes people more open to the influence of new information (Mutz Citation2006). Given this theoretical perspective, we predict that exposure to political disagreement in both online and offline discussions will be positively associated with being open to political persuasion on social media.

H2: Political discussion disagreement will be positively related to political persuasion on social media.

The empirical evidence suggests that news use and exposure to political disagreement are related in social media spaces. More specifically, the idea that disagreement makes people more ambivalent toward, and therefore more open to, diverse information they encounter in the public sphere, implies that exposure to political disagreement moderates the relationship between news exposure and political persuasion. In addition, political communication scholars have long noted that the political effects of media use are often indirect. One strand in this area suggests that many political outcomes are the result of some combination of political and public affairs news consumption and political discussion. When individuals talk about the news, they also engage in cognitive processes that influence further reflection on what they discussed, and this reflection drives other behaviors, such as motivated news use or additional political discussion (Cho et al. Citation2009; Kim, Wyatt, and Katz Citation1999). Thus, the simple act of discussing politics with those holding opposing views should make individuals less recalcitrant in their political opinions because it forces them to think about the information they came across (Fishkin Citation1991; Mutz and Martin Citation2001). Though some scholars may argue that discussion diversity leads people to reinforce existing attitudes (e.g. Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes 2013; Meyer and Tarrow Citation1998; Tilly and Tarrow Citation2015), exceptions may apply in social media because in certain online settings individuals may be more concerned with maintaining social ties than arguing about politics (Bisgin, Agarwal, and Xu Citation2012). The positive social media news use-political persuasion in social media relationship (H1) should be enhanced by an individual’s levels of political discussion disagreement. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3: The relationship between social media news use and political persuasion on social media will be moderated by political discussion disagreement. For those individuals who are exposed to disagreement in their discussions, the positive relationship social media news consumption-political persuasion will be stronger.

The moderating role of civil reasoning in political discussion

Reasoned discussion is engagement in political discussions in which judicious arguments are presented, and civil discussion conducted in a respectful, civil manner (Gastil Citation2000; Papacharissi Citation2004). The concept of civil reasoning combines these two dimensions and characterizes both the strength of arguments presented in discussions, and the civility of those discussions. Both of these concepts are important to theories of deliberative democracy, which suggest that people should come together across lines of social and political difference, and discuss common issues reasonably and in a respectful manner (Conover, Searing, and Crewe Citation2002; Mansbridge Citation1999).

Research shows that both of these dimensions—reasoning and civility—have an influence on political persuasion. First, as predicted by the Elaboration Likelihood Model, people are more persuaded by strong arguments than they are by weak arguments. For example, researchers have found that argument strength affected attitudes about products in advertisements (Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann Citation1983; Petty and Krosnick Citation1995). Hosman, Huebner, and Siltanen (Citation2002) also found that argument quality had a direct effect on attitudes toward social issues. In a similar study, Kempf and Palan (Citation2006) found that argument strength increased positive perceptions of word-of-mouth communication. Second, research also shows that people are more open to considering oppositional arguments when discussions are civil, and they are less likely to consider these arguments when discussions are uncivil. For example, Ng and Detenber (2005) found that civil online discussions were more credible and persuasive than uncivil discussions.

In other studies, Wallsten and Tarsi (Citation2016) found that uncivil discussion in news comment sections leads to less favorable perceptions of the news, and news media in general. Finally, Anderson et al. (Citation2014) found that uncivil discussion on YouTube polarized perceptions of nanotechnology based on prior attitudes toward the topic. Given that both well-reasoned and civil discussions tend to make persuasion more likely, we predict that exposure to online and offline political discussions characterized by civil reasoning will be positively associated with political persuasion.

H4: Civil reasoning will be positively related to political persuasion on social media.

Given that reasoned and civil discussions with others makes people more open to persuasion, civil reasoning should moderate the relationship between the two primary sources of new information (social media news use and political disagreement in online and offline discussions) and political persuasion (Diehl, Weeks, and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2016; Mutz Citation2006). In other words, we predict that people will be more receptive to new ideas from both news media and discussion disagreement when they are presented in a civil and reasoned (with arguments) manner.

H5: Civil reasoning will positively moderate the relationship between social media news use and political persuasion on social media. For those individuals who are exposed to civil reasoning in their discussions, the positive relationship social media news consumption-political persuasion will be stronger.

H6: Civil reasoning will positively moderate the relationship between political discussion disagreement and political persuasion on social media. For those individuals who are exposed to civil reasoning in their discussions, the positive relationship political discussion disagreement-political persuasion will be stronger.

Finally, given the predicted interaction between social media news use and political disagreement on persuasion, it makes sense to inquire as to whether civil reasoning interacts with this process. Social media are a major source of counter-attitudinal information, and disagreement in discussion makes preference change in response to this information more likely (Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic Citation2015; Barberá Citation2014; Huckfeldt, Johnson, and Sprague Citation2004b). If people are most open to these new ideas when they are presented in a civil and reasoned manner, then civil reasoning may further moderate this process. That is, it is possible that people will be the most open to new ideas when they (a) are exposed to counter-attitudinal information in the news media via social media, (b) they encounter disagreement within their political discussion networks (both online and offline), and (c) they engage in discussions that are both civil and reasonable. Because of the lack of prior research on this topic, we pose an exploratory hypothesis.

H7: Civil reasoning will positively moderate the conditional influence of political discussion disagreement in the relationship between social media news use and political persuasion on social media. For those individuals who are exposed to civil reasoning in their discussions, and to political discussion disagreement, the positive social media news use-political persuasion relationship will be stronger.

Methodology

Sample

Survey Sampling International (SSI) distributed the survey from February to March 2014 using a cluster sampling technique to ensure respondents matched the demographic profile of the UK (see Appendix ). Sample quota was requested from SSI based on age, gender, and geographic zone (urban versus rural). In keeping with other studies employing online surveys, the sampling methodology and the sample met general expectations for validity and reliability (e.g., Bode et al. Citation2014; Bosnjak, Das, and Lynn Citation2016). Total collected cases (N = 1529) were then screened for spam cases (i.e. failed to complete at least 60% of the questionnaire, they took very little time to complete the questionnaire, etc.; N = 412), yielding a sample size of 1117 valid cases. Since this is non-probability sample, cooperation rates (proportion of respondents who on having been contacted agree to participate in the study) are calculated in lieu of typical response rates (American Association of Public Opinion Research Citation2016). The cooperation rate (73%) is relatively high.

Measures

This section covers all variables employed in the study and descriptive statistics results from reliability tests. We employed a 10-point Likert scale, where 1 = never or strongly disagree, and 10 = always or strongly agree, for most survey questions.

Social media political persuasion (self-reported)

The main criterion variable of interest in the study is a measure of reconsidering political attitudes in social media, which was based on previous literature (Diehl, Weeks, and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2016; Weeks, Ardèvol-Abreu, and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2017). Respondents were asked three questions: (a) “I have changed an opinion based upon what someone influential to me posted on social media (1 = disagree; 10 = agree),” (b) “How often do you take part in changing your mind about political issues because of information or interactions on social media (1 = never; 10 = strongly agree),” (c) ‘How often do you take part in reconsidering your political views because of information or interactions on social media (1 = never; 10 = strongly agree).” For the 3-item averaged scale, Cronbach’s α = 0.88, M = 2.77, SD = 2.10.

Social media news use

Social media news use was the first independent variable of interest. This study builds on previous scholarship that highlights the various pro-social benefits of using networked communication technologies for news (Gil de Zúñiga, Molyneux, and Zheng, Citation2014; Shah et al. Citation2005). Items asked how often respondents get their news from Facebook and Twitter, how often they encounter news when using social networking sites or micro-blogging sites, and how often they use social media to stay informed about current events and public affairs, to stay informed about the local community, and finally, to get news about current events from mainstream media. For the six-item average construct, Cronbach’s α = 0.91, M = 3.60, SD = 2.40.

Political discussion disagreement

The survey also asked respondents to rate how often they “use social media to have discussions with people who have different views,” “how often do you talk about politics or public affairs online and offline with people who disagree with you,” and “whose political views are different from yours?” For the three-item average construct, Cronbach’s α = 0.76, M = 3.30, SD = 2.20.

Civil reasoning

The measure for civil reasons was based on the assumption that respondents will make an association between providing evidence for claims and civil discussion (Gastil and Black Citation2007). Although it is possible that not all respondents make an association between evidence and civility, crosstab comparisons reveal that they are strongly associated. Although civility and rationality (providing evidence) are conceptually very different things, our data show that they are empirically tied, and therefore we opted to combine them). The three items for civil reasoning are: “How often do you talk about politics or public affairs online and offline with people who: (a) back up arguments with evidence, (b) propose alternatives or policies for problem solving, (c) who discuss politics in a civil manner?’ For the three-item average construct, Cronbach’s α = 0.95, M = 3.40, SD = 2.60.

Political discussion network size

Following Eveland, Hutchens, and Morey (Citation2013), respondents were asked open-ended questions to get following estimates for the last month: “about how many people would you say you have talked to via the Internet, including e-mail, chat rooms, social networking sites, and micro-blogging sites,” and “about how many total people have you talked to face-to-face or over the phone about politics or public affairs”’ Averaged item index, using a natural log to improve distribution was as follows: Spearman-Brown coefficient =0.67; M = .53, SD = 0.26; skewness = 1.40.

Political discussion frequency

The frequency with which and individual engages in political discussion might influence the extent to which one experiences disagreement on social media (Eveland and Hutchens Citation2009). Frequency of political discussion was measured using five separate items that asked how often respondents talk about politics or public affairs online and offline, with a spouse or partner, family or relatives, friends, acquaintances, and strangers. For the 5-item average construct, Cronbach’s α = 0.84; M = 3.10, SD = 2.10.

Non-social media news media use

Prior research has linked citizens’ offline news consumption with attitude change (e.g., Feldman Citation2011). Nine questions addressed overall news consumption in the study. Respondents were asked to rate how often they get news from network TV, national and local newspapers, cable, satirical news programs, radio, online, and citizen journalism and “hyper local” websites. For the 9-item average construct, Cronbach’s α = 0.80; M = 4.10, SD = 1.70.

Frequency of social media use

Most people use social media to connect with family and friends, socialize, or checkup on distant contacts (Quan-Haase and Young Citation2010). Respondents were asked to rate, on a typical day, “How much do you use social media,” “How often do you use social media to stay in touch with friends and family,” “How often do you use social media to meet new people who share interests,” and finally “How often do you use social media to contact people you wouldn’t meet otherwise?” For the 4-item average construct, Cronbach’s α = 0.88, M = 4.50, SD = 2.60.

Strength of ideology

Strength of political ideology has been associated with political discussion and political attitude formation (Bartels Citation2002; Huckfeldt, Mendez, and Osborn Citation2004a). Two items asked, on a scale of 0–10, where 0 = strong conservative and 10 = strong liberal: “On social issues, where would you place yourself,” and “On economic issues, where would you place yourself?” Items were folded into a five-point index, where 0 = low affiliation and 5 = strong ideological affiliation. Here the Spearman-Brown coefficient = .87, M = 1.82, SD = 1.31.

Political efficacy

Research on deliberative democracy shows that the nature of political discussion is contingent upon levels of individual political self-efficacy (Gastil and Xenos Citation2010; Morrell Citation2005). Political efficacy was measured with the items: “I consider myself well qualified to participate in politics,” “I have a good understanding of the important political issues facing our country,” and “People like me can influence government.” For the 3-item average construct, Cronbach’s α = 0.81; M = 4.40, SD = 2.2.

Political knowledge

More knowledgeable people tend to be more resistant to political persuasion (Huber and Arceneaux Citation2007). Respondents were asked multiple-choice questions about various political actors, rules related to government institutions, and current events (Delli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996). The questions were: (a) What job or political office does Nick Clegg currently hold, (b) How many years is a British Member of Parliament elected, (c) What political office does Sir John Thomas currently hold, (d) On which of the following does the UK government currently spend the least, (e) Do you happen to know what the “bedroom tax” is all about, (f) Which party currently has the most members in the House of Lords, (g) Which organization’s documents were released by Edward Snowden, (h) Recently, the UN and US were in negotiations with the Syrian government over the removal of what. These questions were based on top stories in Pew Research Center’s News Coverage Index for the weeks prior to the survey administration dates. For the eight-item average construct (1 = correct answer, 0 = incorrect answer; Range 0–8), Cronbach’s α = 0.55; M = 3.30; SD = 1.70.

Political interest

Political interest has long been associated with political discussion, in both online and offline contexts (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995; Bimber et al. Citation2015). Two items asked, “How interested are you in information about what’s going on in politics and public affairs,” and “How closely do you pay attention to information about what's going on in politics and public affairs.” Here Spearman-Brown coefficient =0.96; M = 5.70, SD = 2.60.

Demographics

The sample had more females (55.9%) than males (43.50), was mostly white (91%), middle-aged (M = 45.70; SD = 12.75), and was moderately educated (M = 3.17; some college). When compared with the U.K. Census, the population in our sample was slightly older, skewed female, and had higher levels of education. Education was measured in eight categories (1 = less than high school, 8 = doctoral degree). Income was measured using 8 categories of total annual household income (M = 3.20; £15,000–£24,999).

Analysis

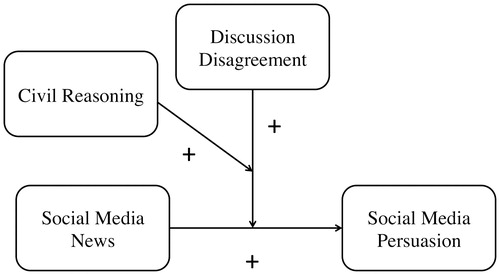

Statistical analysis relied on a series of ordinarily least squares (OLS) regression models. The models were designed to include three blocks of control variables: demographics, media use and network attributes, and political traits. The final block of variables contained the predictor variables of interest. Social media news use, political discussion disagreement, and civil reasoning were added in the fourth and final block of the OLS models. Political persuasion on social media was the main dependent variable in each model. To answer the research questions and hypotheses related to moderated relationships, we also tested a conceptual model with two moderators. The three-way moderation model included all predictor variables, and was analyzed using Hayes PROCESS macro (Model 3; Hayes Citation2017). In this model, political discussion disagreement was the primary moderator (M), and civil reasoning operated as the secondary moderator (W) (). Data analysis was conducted in SPSS 22.

Results

H1 hypothesized that social media news use will be positively associated with changing or reconsidering political opinions based on information received through social media. also shows positive, statistically significant correlations between political persuasion in social media and frequency of social media use (r = 0.59, p < .001), nonsocial media news use (r = .53, p < .001), and social media news use (r = 0.72, p < .001). With the exception of overall social media use, the existence of these relationships is supported in the OLS regression analyses (). After accounting for the influence of demographics, discussion network attributes, and political orientations (Δ R2 = 45%), social media news use remains strongly associated with political persuasion on social media (β = 0.42, p < .001) (Total model R2 = 60%). Holding all other predictors constant, an increase of one SD on the social media news use scale corresponds with an increase of 42% of a SD on the persuasion scale. H1 is supported.

Table 1. Zero-order correlations among all independent and dependent variables in the analysis.

Table 2. OLS regression model testing relationships among social media news use, discussion political disagreement, and civil reasoning on social media political persuasion.

H2 hypothesized that political discussion disagreement will be positively associated with political persuasion on social media. Exposure to dissenting political opinions online is positively related to persuasion in the zero-order correlations () (r = 0.58, p < .001). Political discussion disagreement is a positive, statistically significant predictor of being persuaded about politics through social media, even after accounting for demographics, political orientations, and overall media use () (β = 0.42, p < .001). Thus, H2 is supported.

H3 predicts that political discussion disagreement will moderate the relationship between social media news use and political persuasion. In other words, there should be a stronger relationship between social media for news use and political persuasion (H1) when respondents show higher levels of political discussion disagreement. shows the relevant results, which are reported as unstandardized beta coefficients. The interaction of exposure to political discussion disagreement and social media news use on political persuasion on social media was positive and statistically significant (B = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001). Among respondents who report being exposed to higher levels of dissenting political discussion, the relationship between social media news use and political persuasion on social media is stronger. H3 is supported.

Table 3. OLS moderated moderation model showing three-way interactions among social media news use, political discussion disagreement, and civil reasoning political persuasion on social media.

Interaction terms

The next set of hypotheses (H4-H6) address the role of civil reasoning in the process of political persuasion on social media. Civil reasoning is positively correlated with getting news on social media () (r = .36, p < .001), political discussion disagreement (r = .81, p < .001), and social media political persuasion (r = .38, p < .001). In the OLS model (), civil reasoning had no direct relationship with social media political persuasion (H4). H4 is rejected. However, among people who score high in civil reasoning social media news use has a significant and positive relationship with political persuasion on social media (H5) () (B = 0.04, SE = 0.01, p < .001). Thus, civil reasoning moderates the relationship between social media news use and political persuasion on social media, as expected, and H5 is supported. H6 predicts that civil reasoning will moderate the relationship between discussion political disagreement and political persuasion. shows that the interaction fails to reach commonly accepted levels of statistical significance (B = –0.016, SE = 0.010, n.s.). H6 is rejected.

H7 asks how civil reasoning might influence the extent to which an individual will be persuaded by information on social media when they use social media for news and are exposed to political discussion disagreement. By employing a three-way interaction model, we can estimate the moderating influence of civil reasoning, which operates as a secondary moderator (Hayes Citation2017), in this process (see ).

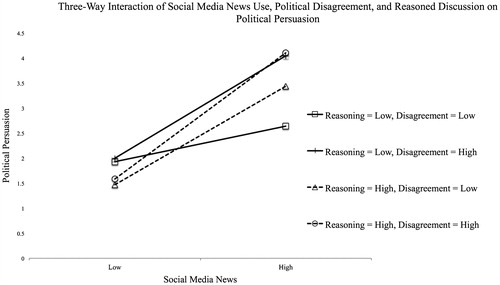

The overall three-way interaction model (moderated moderation) accounted for 62.3% of the total variance of being political persuaded on social media. Furthermore, the three-way interaction of social media news use by political discussion disagreement and by reasoned discussions uniquely accounted for 0.3% of the variance (F[20, 1057] = 88.77, p = .001). The moderated moderation model shows a statistically significant and negative three-way interaction between social media news use, political discussion disagreement, and civil reasoning () (B = –0.008, SE = 0.003, p < .05). Results from the three-way interaction model are visualized in , which shows that the highest mean for persuasion occurs among the group that scored high in news use, disagreement, and civil reasoning (M = 4.10). Looking more closely at , we see that there is a significant interaction between news use and disagreement at low levels of civic reasoning (B = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < .001).

Figure 2. Three-way interaction plot of social media news use, political discussion disagreement, and civil reasoning on political persuasion on social media.

In instances where people do not present many arguments in their discussion, or their civil reasoning is low, the relationship between news use and persuasion is significantly stronger where there are high levels of disagreement (B = 0.44, SE = 0.07, p < .001) than where there are low levels of disagreement (B = 0.15, SE = 0.05, p < .001). On the other hand, where civil reasoning is high, there is no significant interaction between news use and disagreement on persuasion. For these subgroups, the relationship between news use and persuasion is statistically significant, and positive regardless of the level of disagreement, and these relationships are not statistically different from one another (for high disagreement, B = 0.53, SE = 0.04, p < .001; for low disagreement, B = 0.42, SE = 0.07, p < .001).

Discussion

The prevalence of social media makes it easy to express one’s political opinion, share political information and news, and become exposed to the opinions of others. This study finds evidence for a model of persuasion in social media environments that suggests people are most open to persuasion when (a) they consume political news through social media, (b) they are exposed to political disagreement in both online and offline discussions, and (c) political arguments are presented in a reasoned and civil manner. In other words, people are less likely to “dig in their heels” when they encounter disagreeable, but well-reasoned and civil, information on social media. Reconsidering one’s political views is most likely to happen when discussion disagreement, or civility, is high and news consumption is high.

First, this study supports the idea that the news media and political discussion within interpersonal networks are the two primary sources of political information that makes people more open to persuasion. As social media have grown in importance as sources of news, so too has the link between social media news use and political persuasion. This study finds a direct relationship between these variables, which was the strongest among the variables of interest in the statistical model (). This finding is concurrent with prior research that shows a direct relationship between news use and political persuasion in social media contexts (Barker and Lawrence Citation2006; Feldman Citation2011; Ladd and Lenz Citation2008), and it contributes to an increasingly convincing argument for examining the influence of social media news use on political attitudes and opinions (Bode Citation2016; Bond et al. Citation2012; Turcotte et al. Citation2015; Beam, Hutchens, and Hmielowski Citation2016).

The study also finds a direct relationship between political discussion disagreement and political persuasion in social media contexts, which aligns with previous literature showing a direct relationship between online and offline discussion and political persuasion on social media in the U.S. context. Offline and online social networks become increasingly isomorphic, and this process has arguably increased the amount of political disagreement people encounter in their daily lives through discussion (Bachmann and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2013; Barnidge Citation2015; Heatherly, Lu, and Lee 2016; Kim Citation2011; Rojas Citation2015). Because political disagreement has the capacity to make people more ambivalent, it arguably makes them more open to political persuasion.

Second, the study finds that political discussion disagreement moderates the relationship between social media news use and political persuasion on social media. More specifically, the study shows that the relationship between news use and reconsidering political beliefs is stronger among those who encounter political difference in online and offline discussions. Prior research suggests that political discussion largely mediates the relationship between news use and political attitude formation and/or change (Cho et al. Citation2009; Kim, Wyatt, and Katz Citation1999), perhaps because discussion promotes cognitive processes of reflection on previously held ideas. Therefore, the act of discussion the information to which one is exposed in both online and offline settings may make individuals more open to cross-cutting ideas (Fishkin Citation1991; Mutz and Martin Citation2001).

Third, the study shows that civil reasoning also plays a moderating role in the process of political persuasion on social media, pointing toward two specific conclusions. The first conclusion is that political persuasion on social media is most likely when people (a) use social media for news, (b) encounter political difference in their offline and online social networks, and (c) are presented with arguments in a reasonable and civil manner. Among the study’s respondents, those who scored high on these variables were also the most open to political persuasion in social media contexts. This conclusion implies that well-reasoned, civil disagreement about news articles posted on social media make conditions ripe for social influence. This implication fits with prior research showing the persuasive influence of disagreement, strong argumentation, and civility (Huckfeldt, Mendez, and Osborn Citation2004a; Ng and Detenber 2005; Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986).

Digging deeper into the process of moderated moderation behind political persuasion in social media contexts, the second conclusion is that political persuasion is more likely when people use social media for news and either (a) encounter political different in their social networks or (b) encounter well-reasoned ideas presented in a civil manner. Where reasoning was low, the relationship between news use and persuasion was stronger where disagreement was high. Where reasoning was high, the news use—persuasion relationship was strong at all levels of disagreement. This conclusion implies that disagreement may not be a necessary condition for political persuasion on social media. Rather, civil and well-reasoned argumentation can persuade people toward their own side.

There are some important limitations to note when interpreting the results of this study. First, the results are based on self-directed online surveys, which are prone to sampling and measurement error. However, the cluster and stratified quote sampling techniques implemented by SSI polling company in their opt-in panel provides estimates of population parameters that are in line with census estimates (see Appendix ). Second, we do not know the content of the discussions on social media, and we do not have a measure of the particular opinions that people change when they report being persuaded. Therefore, it remains unclear whether individuals are changing their minds to conform to opinions prevailing in their social network, or if they are altering their preexisting attitudes to mirror a diverse opinion climate. Finally, the dependent variable of interest, persuasion on social media, is based on a self-reported measure. There may be an element of social-desirability that influence’s one’s response. Future studies might employ more direct observational designs or experiments to capture distinct altitudinal or behavioral changes in response to different types of social media content. Results from this study offer an opportunity for future studies to test these nuances in an experimental setting.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a clear contribution to our understanding of political attitude formation on social media. In particular it highlights the processes through which information is received and discussed in both online and offline social networks. Both political disagreement and civil reasoning may set the stage for persuasion on social media. But persuasion is most likely when both factors are at play. That is, people are most likely to reconsider their views when they engage in well-reasoned, civil disagreement about the news and information they receive in social media settings. These conclusions provide a relatively optimistic view of social media’s contribution to democratic discourse, particularly in light of the growing tendency toward contention in Western societies.

Notes

1 It is possible that not all respondents associate these two, though crosstab frequencies based on mean comparisons reveal that over 95% of the population score above the mean on both measures (civil reasoning and exposure to conversations where individuals provide evidence). Although civility and rationality (providing evidence) are conceptually very different things, our data show that they are empirically tied, and therefore we opted to combine them).

References

- American Association of Public Opinion Research. 2016. Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Available at: https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf (accessed June 7, 2018).

- Anderson, A. A., D. Brossard, D. A. Scheufele, M. A. Xenos, and P. Ladwig. 2014. The “nasty effect”: online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19 (3):373–87. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12009.

- Bachmann, I., and H. Gil de Zúñiga. 2013. News platform preference as a predictor of political and civic participation. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 19 (4):496–512. doi:10.1177/1354856513493699.

- Bakshy, E., S. Messing, and L. Adamic. 2015. Political science. Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science (New York, N.Y.) 348 (6239):1130–2. doi:10.1126/science.aaa160.

- Barberá, P. 2014. How social media reduces mass political polarization: Evidence from Germany, Spain, and the United States. http://pablobarbera.com/static/barbera-polarization-social-media.pdf (accessed June 7, 2018).

- Barker, D., and A. B. Lawrence. 2006. Media favouritism and presidential nominations: Reviving the direct effects model. Political Communication 23 (1):41–59. doi:10.1080/10584600500477013.

- Barnidge, M. 2015. The role of news in promoting political disagreement on social media. Computers in Human Behavior 52:211–8. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.011.

- Bartels, L. M. 2002. Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior 24 (2):117–150.

- Beam, M. A., M. J. Hutchens, and J. D. Hmielowski. 2016. Clicking vs. sharing: the relationship between online news behaviors and political knowledge. Computers in Human Behavior 59:215–20.

- Bennett, W. L., and A. Segerberg. 2012. The logic of connective action: the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication and Society 15 (5):739–68. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

- Benkler, Y. 2006. The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Bimber, B., M. C. Cunill, L. Copeland, and R. Gibson. 2015. Digital media and political participation: the moderating role of political interest across acts and over time. Social Science Computer Review 33 (1):21–42.

- Bisgin, H., N. Agarwal, and X. Xu. 2012. A study of homophily on social media. World Wide Web 15 (2):213–232. doi:10.1007/s11280-011-0143-3.

- Bode, L. 2016. Political news in the news feed: Learning politics from social media. Mass Communication and Society 19 (1):24–48. doi:10/1080/15205436.2015.10455149.

- Bode, L., E. K. Vraga, P. Borah, and D. V. Shah. 2014. A new space for political behavior: Political social networking and its democratic consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19 (3):414–429. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12048.

- Bond, R. M., C. J. Faris, J. J. Jones, A. D. Kramer, C. Marlow, J. E. Settle, and J. H. Fowler. 2012. A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature 489 (7415):295–298. doi:10.1038/nature11421.

- Bosnjak, M., M. Das, and P. Lynn. 2016. Methods for probability-based online and mixed-mode panels. Symposium issue on methods for probability-based online and mixed-mode panels. Social Science Computer Review 34 (1):3–5. doi:10.1177/0894439315579246.

- Brundidge, J. 2010. Encountering “difference” in the contemporary public sphere: the contribution of the internet to the heterogeneity of political discussion networks. Journal of Communication, 60 (4):680–700. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01509.x.

- Cho, J., Shah, D. V. D. V. McLeod, J. M. McLeod, D. M. Scholl, R. M., and M. R. Gotlieb. 2009. Campaigns, reflection, and deliberation: Advancing an O‐S‐R‐O‐R model of communication effects. Communication Theory 19 (1):66–88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.01333.x.

- Conover, P. J., D. D. Searing, and I. M. Crewe. 2002. The deliberative potential of political discussion. British Journal of Political Science 32 (1):21–62.

- Delli Carpini, M. X., and S. Keeter. 1996. What americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Diehl, T., B. E. Weeks, and H. Gil de Zúñiga. 2016. Political persuasion on social media: Tracing direct and indirect effects of news use and social interaction. New Media and Society 29 (2):214–239. doi:10.1177/1461444815616224.

- Eveland Jr, W. P., and H. M. Hutchens. 2009. Political discussion frequency, network size, and “heterogeneity” of discussion as predictors of political knowledge and participation. Journal of Communication 59 (2):205–224.

- Eveland W. P., M. J. Hutchens, and A. C. Morey. 2013. Political network size and its antecedents and consequences. Political Communication 30 (3):371–394.

- Feldman, L. 2011. The opinion factor: the effects of opinionated news on information processing and attitude change. Political Communication 28 (2):163–81. doi:10.1080/10584609.2011.565014.

- Feldman, L., E. W. Maibach, C. Roser-Renouf, and A. Leiserowitz. 2012. Climate on cable. The nature and impact of global warming coverage on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC. The International Journal of Press/Politics 17 (1):3–31. doi:10.1177/1940161211425410.

- Fishkin, J. S. 1991. Democracy and deliberation: New directions for democratic reform. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Garrett, R. K., S. Dvir Gvirsman, B. K. Johnson, Y. Tsfati, R. Neo, and A. Dal. 2014. Applications of pro- and counter-attitudinal information exposure for affective polarization. Human Communication Research 40 (3):309–332.

- Gastil, J. 2000. By popular demand: Revitalizing representative democracy through deliberative elections. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Gastil, J., and L. Black. 2007. Public deliberation as the organizing principle of political communication research. Journal of Public Deliberation 4 (1):1–49. http://services.bepress.com/jpd/vol4/iss1/art3

- Gastil, J., and M. Xenos. 2010. Of attitudes and engagement: Clarifying the reciprocal relationship between civic attitudes and political participation. Journal of Communication 60 (2):318–43. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01484.x.

- Glynn, C. J., M. E. Huge, and L. H. Hoffman. 2012. All the news that’s fit to post: a profile of news use on social networking sites. Computers in Human Behavior 28 (1):113–9. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.017.

- Gil de Zúñiga. H. 2012. Modeling the process of political participation in the EU. In European identity & culture: Narratives of transnational belonging, eds. R. Friedman and M. Thiel, 75–95. New York: Ashgate.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H. 2015. Toward a European public sphere? the promise and perils of modern democracy in the age of digital and social media. International Journal of Communication 9:3152–3160.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., and S. Valenzuela. 2010. Who uses Facebook and why. In Facebook and philosophy: What's on your mind? ed. D. Wittkower, xxi–xxxi. Chicago: Open Court.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., L. Molyneux, and P. Zheng. 2014. Social media, political expression and political participation: Panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. Journal of Communication 64(4):612–34. doi:10.1111/jcom.12103.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., S. Valenzuela, and B. Weeks. 2016. Motivations for political discussion: Antecedents and consequences on civic participation. Human Communication Research 42 (4):533–52. doi:10.1111/hcre.12086.

- Granovetter, M. 1983. The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. Sociological Theory 1:201–233. http://www.jstor.org/stable/202051

- Halpern, D., and J. Gibbs. 2013. Social media as a catalyst for online deliberation? Exploring the affordances of Facebook and YouTube for political expression. Computers in Human Behavior 29 (3):1159–1168. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.008.

- Hayes, A. F. 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

- Heatherly, K. A., Y. Lu, and J. K. Lee. 2017. Filtering out the other side? cross-cutting and like-minded discussions on social networking sites. New Media & Society 19 (8):1271–89. doi:10.1177/1461444816634677.

- Hosman, L. A., T. M. Huebner, and S. A. Siltanen. 2002. The impact of power-of-speech style, argument strength, and need for cognition on impression formation, cognitive responses, and persuasion. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 21 (4):361–79. doi:10.1177/026192702237954.

- Huber, G. A., and K. Arceneaux. 2007. Identifying the persuasive effects of presidential advertising. American Journal of Political Science 51 (4):957–977.

- Huckfeldt, R., J. Mendez, and T. Osborn. 2004a. Disagreement, ambivalence, and engagement: the political consequences of heterogeneous networks. Political Psychology 25 (1):65–95. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00357.x.

- Huckfeldt, R., P. E. Johnson, and J. Sprague. 2004b. Political disagreement: the survival of diverse opinions within communication networks. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Iyengar, S., G. Sood, and Y. Lelkes. 2012. Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective. Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (3):405–431. doi:10.1093/poq/nfs038.

- Katz, E., and P. E. Lazarsfeld. 1955. Personal influence: the part played by people in mass communication. New York: The Free Press.

- Kempf, D. S., and K. M. Palan. 2006. The effects of gender and argument strength on the processing of word-of-mouth communication. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 10 (1):1–18.

- Kim, J., R. O. Wyatt, and E. Katz. 1999. News, talk, opinion, participation: the part played by conversation in deliberative democracy. Political Communication 16 (4):361–85.

- Kim, Y. 2011. The contribution of social network sites to exposure to political difference: the relationships among SNSs, online political messaging, and exposure to cross-cutting perspectives. Computers in Human Behavior 27 (2):971–977. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.12.001.

- Kim, Y., Hsu, S. H. Gil de Zúñiga. H., and H. 2013. Influence of social media use on discussion network heterogeneity and civic engagement: the moderating role of personality traits. Journal of Communication 63 (3):498–516. doi:10.1111/jcom.12034.

- Kwon, K. H., M. A. Stefanone, and G. A. Barnett. 2014. Social network influence on online behavioral choices: Exploring group formation on social network sites. American Behavioral Scientist 58 (10):1345–1360. doi:10.1177/0002764214527092.

- Ladd, J. M. and G. S. Lenz. 2008. Exploiting a rare shift in communication flows to document news media persuasion: The 1997 United Kingdom general election. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id =1189811 (accessed June 7, 2017).

- Lee, J. K., J. Choi, C. Kim, and Y. Kim. 2014. Social media, network heterogeneity, and opinion polarization. Journal of Communication 64 (4):702–22. doi:10.11/jcom.12077.

- Levitan, L. C., and P. S. Visser. 2009. Social network composition and attitude strength: Exploring the dynamics within newly formed social networks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45 (5):1057–1067.

- Lu, Y., K. A. Heatherly, and J. K. Lee. 2016. Cross-cutting exposure on social networking sites: the effects of SNS discussion disagreement on political participation. Computers in Human Behavior 59:74–81. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.030.

- Mansbridge, J. 1999. Everyday talk in the deliberative system. In Deliberative politics: Essays on democracy and disagreement, ed. S. Macedo, 211–42. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McCombs, M. E., and D. L. Shaw. 1972. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2):176–87. doi:10.1086/267990.

- Messing, S., and S. J. Westwood. 2014. Selective exposure in the age of social media: endorsements trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online. Communication Research 41 (8):1042–1063. doi:10.1177/0093650212466406.

- Meyer, D. S., and S. G. Tarrow. 1998. The social movement society: Contentious politics for a new century. New York: Roman & Littlefield.

- Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Kiley, J., and K.E. Matsa. 2014. Political polarization and media habits (Report for the Pew Research Internet Project). Available at: http://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/ (accessed June 7, 2018).

- Morrell, M. E. 2005. Deliberation, democratic decision-making and internal political efficacy. Political Behavior 27 (1):49–69.

- Mutz, D. C. 2006. Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mutz, D. C., and P. S. Martin. 2001. Facilitating communication across lines of political difference: the role of mass media. American Political Science Review 95 (1):97–114.

- Mutz, D. C., P. M. Sniderman, and R. A. Brody. 1996. Political persuasion: The birth of a field of study. In Political persuasion and attitude change, eds. D.C. Mutz, P.M. Sniderman, and R.A. Brody, 1–14. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

- Nelson, T. E., Z. M. Oxley, and R. A. Clawson. 1997. Toward a psychology of framing effects. Political Behavior 19 (3):221–46. doi:10.1023/A:1024834831093.

- Ng, E. W. J., and B. H. Detenber. 2006. The impact of synchronicity and civility in online political discussions on perceptions and intentions to participate. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 10 (3):00. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00252.x

- Ofcom. 2015. News consumption in the UK 2015, executive summary. London, UK. http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/tvresearch/news/2015/News_consumption_in_the_UK_2015_executive_summary.pdf (accessed December 1, 2016).

- Papacharissi, Z. 2004. Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society 6 (2):259–83. doi:10.1177/1461444804041444.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2014. Affective publics: Sentiment, technology, and politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Petty, R. E., J. T. Cacioppo, and D. Schumann. 1983. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: the moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research 10 (2):135–46. doi:10.1086/208954.

- Petty, R. E., and J. T. Cacioppo. 1986. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 19:123–205. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60214-2.

- Petty, R. E., and J. A. Krosnick. 1995. Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Pew Research Center. 2015. State of the news media 2015. http://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/state-of-the-news-media-2015 (accessed March 1, 2017).

- Quan-Haase, A., and A. L. Young. 2010. Uses and gratifications of social media: a comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30 (5):350–361. doi:10.1177/0270467610380009.

- Rojas, H. 2015. Egocentric publics and perceptions of the worlds around us. In New technologies and civic engagement: New agendas in communication, ed. H. Gil de Zúñiga, 93–102. New York: Routledge.

- Rojas, H., M. Barnidge, and E. P. Abril. 2016. Egocentric publics and corrective action. Communication and the Public 1 (1):27–38. doi:10.1177/2057047315619421.

- Shah, D. V., J. Cho, W. P. Eveland, and N. Kwak. 2005. Information and expression in a digital age modeling internet effects on civic participation. Communication Research 32 (5):531–65.

- Tilly, C., and S. Tarrow. 2015. Contentious politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Turcotte, J., C. York, J. Irving, R. M. Scholl, and R. J. Pingree. 2015. News recommendations from social media opinion leaders: Effects on media trust and information seeking. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (5):520–35. doi:10.111/jcc4.12127.

- Verba, S., K. L. Schlozman, and H. E. Brady. 1995. Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. New York: Harvard University Press.

- Wallsten, K., and M. Tarsi. 2016. Persuasion from below? an experimental assessment of the impact of anonymous comments sections. Journalism Practice 109 (8):1019–1040. doi:10.1080/17512786.2015.1102607.

- Weeks, B. E., A. Ardèvol-Abreu, and H. Gil de Zúñiga. 2017. Online influence? Social media use, opinion leadership, and political persuasion. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 299 (2):214–239. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edv050.

- Wood, W. 2000. Attitude change: Persuasion and social influence. Annual Review of Psychology 51 (1):539–570. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.539

- Zaller, J. 1992. The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge.

Appendix

Table A1. Demographic profile of study survey and other comparable surveys.