Abstract

Digital financial inclusion initiatives in developing countries have gained salience because of their potential to improve the socioeconomic condition of marginalized groups such as low-income women. However, persistent challenges remain in overcoming the digital divide in developing countries and enhancing access and participation of women in digital financial services. Despite the growing scholarly attention, little is known about how digital technologies might be designed to enable financial inclusion of women in developing countries. Using the technology affordances approach, we extend previous theorizing on inclusive information system, and introduce a relational approach to designing for inclusion. Specifically, we conduct a case study of a digital finance initiative in Ghana involving the design of an interactive voice response system (IVR) for low-income women where systemic barriers to technology adoption and use are pervasive. We show the significance of user feedback, environmental factors, and affordances for more inclusive information system design. We contribute a theoretically grounded framework that takes holistic account of the sociotechnical context of IS design for inclusion.

Introduction

Although digital innovation is recognized as a major contributor in changing the social, economic, and political landscape across the globe, persistent concerns remain about the digital divide and its implication for marginalized groups, particularly women living in developing countries (Olatokun Citation2008; Vimalkumar, Singh, and Sharma Citation2021). In a number of African countries, women are often left behind in terms of access and use of digital technologies (Mbarika et al. Citation2007; Alozie and Akpan‐Obong Citation2017). This has serious implications for social and economic progress, which is linked to the participation of women in the digital revolution (Alozie and Akpan‐Obong Citation2017; World Bank Citation2021).

United Nations in its Sustainable Development Goals spotlights the importance of empowering women (Adeola Citation2020). The African Union, declared the last decade as the “African Women Decade” to drive grassroot participation. Its declaration further highlighted the importance of harnessing digital technologies to improve women’s socio-economic status across the continent, creating more inclusive economies and closing the gaps in gender equality (African Union Citation2018). One such way to drive socio-economic development is through digital financial inclusion.Footnote1

Digital technologies can engender financial inclusion by facilitating the provision of digital financial services (DFS) (Buteau, Rao, and Valenti Citation2021). DFS “encompasses a magnitude of new financial products, financial businesses, finance-related software, and novel forms of customer communication and interaction – delivered by FinTech companies and innovative financial service providers” (Gomber, Koch, and Siering Citation2017, 537). While DFS is important for financial inclusion, there are both demand-side and supply-side barriers to financial inclusion (Dupas and Robinson Citation2013; Kalba Citation2016). On the demand-side, women often lack access to appropriate technologies and this inhibits their ability to adopt DFS (Mbarika et al. Citation2007; Klapper and Dutt Citation2015; Mumporeze and Prieler Citation2017; GSMA Citation2019; Hendriks Citation2019; Molinier Citation2019). For example, for the use of mobile money systems, having mobile access is a fundamental requirement, yet in Sub-Saharan Africa gender gaps in mobile phone ownership and usage stood at 15% and 33% respectively (GSMA Citation2019; UNECA Citation2020). On the supply side, barriers include unsuitable product offerings and distribution channels (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Citation2012; Gammage et al. Citation2017).

Previous research has paid more attention to the demand-side of inclusion, examining factors related to individuals and households, and largely ignored the supply-side factors such as technology design (Dupas and Robinson Citation2013; Kalba Citation2016). Critically, research suggests that uptake of technologies by marginalized groups, such as low income women, is to a great extent an outcome of their design features, and, subsequently, their enactment in practice opens up social and economic opportunities for them (Fountain Citation2000; Salvador, Rojas, and Susinos Citation2010). Consequently, design decisions have profound impacts on social and economic empowerment through technological innovation (Stillman and Denison Citation2014).

Exclusion occurs when users’ identity, defined by their gender, socio-economic status, age, disability and so on, does not align or there is a perceived lack of alignment with the designed product (Zheng and Walsham Citation2008; Tambulasi Citation2009). Therefore inclusive design strives to create products, services, and experiences that are effective and user-friendly as well as accessible, and convenient to use for individuals in a diverse range of situations, without requiring modifications or accommodations (Tobias Citation2003; Johnson, Clarkson, and Huppert Citation2010; Simons, Fleischmann, and Roy Citation2020; Patrick and Hollenbeck Citation2021). However, persistent challenges for inclusive design remain with conflicting approaches suggested for roles of both designers and users in the design process (Olbrich et al. Citation2015; Wass, Thygesen, and Purao Citation2023).

We focus on how project designers design digital technology artifacts to promote accessibility, usability, and effectiveness of DFS. We explore the relational process, between designers and users for inclusive design in a developing country – Ghana. A relational process allows for the design decisions to be informed by users’ needs and understanding of barriers unique to their situations. Specifically, we examine the process of redesigning an interactive voice response system (IVR), which is part of a DFS system, for low-income Ghanaian women. We recognize some broader social structures (e.g. cultural norms, economic factors, gender roles) impacting design, thereby address the call by Simons, Fleischmann, and Roy (Citation2020) to explore social and organizational contexts of digital phenomena.

Leveraging technologies for gender equality and women’s advancement for financial inclusion, requires a holistic approach (UNECA Citation2020). Drawing from the sociotechnical tradition of information systems (IS) research, we argue that such a holistic approach takes into consideration design and overall functionality of the technology as well as the broader considerations such as socio-economic factors, e.g. literacy rates and income levels impede technology adoption, supportive social context (social network and support) is needed for user adoption and utilization of technology (Alozie and Akpan‐Obong Citation2017; Aziz and Naima Citation2021; Kolade et al. Citation2022). These is a particularly important issue in contexts of profound gender divide because “gender-neutral” approach to product design in reality often becomes by default male-centric (Wilson Citation2002; Fox, Johnson, and Rosser Citation2006; Fuchs and Horak Citation2008).

We propose a relational approach to design decisions, in order to foster inclusion. Further, we suggest a more holistic approach to viewing inclusive design to take into consideration societal barriers to inclusion. We organize the article as follows. We start by highlighting the relevant IS literature on financial inclusion and introduce our technology affordances approach to design. Next, we describe our method, case, and findings. We discuss implications of our findings and conclude with contributions for scholarship and practice.

Information systems and financial inclusion

Calls to bridge the digital divide through inclusive IS designs are persistent, regular, and insistent, both in press and in academia. However, challenges remain. There is a growing recognition that ISs are subject to existing structures of privilege (e.g., Kvasny and Trauth Citation2003) and are not gender neutral (e.g., Alozie and Akpan‐Obong Citation2017). Furthermore, due to existing societal inequalities, systematic exclusion is inherent in IS design, implementation, and organization (e.g., Zheng and Walsham Citation2008; Tambulasi Citation2009). This has led to a growing recognition of the critical need for the awareness of local context and local adaptation of IS (Urquhart and Underhill-Sem Citation2009).

The concern about IS being inadvertently exclusionary is not just imagined. There are documented examples of this including: 1) marginalized communities are omitted as a user group when upgrading or redesigning an IS (e.g. Letch and Carroll Citation2008), 2) although recognized as a user group, subsequently, marginalized communities are excluded in the consultations during the design phase and/or not given opportunities to provide feedback (e.g. Wilson Citation2002), and 3) when providing feedback or raising concerns, users from disadvantaged groups are denied equal voice or their voices are marginalized (e.g. Naidoo, Coleman, and Guyo Citation2020).

Previous research acknowledges both first order and second order effects of exclusion: access to technology (first order effects) and inequality in the ability to use IS among those with access (second order effects), respectively (Dewan and Riggins Citation2005). Broadening the approach of understanding second-order exclusion, we acknowledge the wider remit of exclusion as a multi-dimensional concept that involves “the involuntary exclusion of individuals and groups from society’s political, economic and societal processes, which prevents their full participation in the society in which they live” (Atkinson and Marlier Citation2010, 1).

Generally, the literature on inclusion in IS has focused on two perspectives (Trauth Citation2017). The first perspective considers those within the system who create, design, and work in IS (e.g. Joshi et al. Citation2017; Armstrong, Riemenschneider, and Giddens Citation2018); the second perspective, focuses on end-users and the impact that IS designs have on specific user groups (e.g. Light, Fletcher, and Adam Citation2008; Naidoo, Coleman, and Guyo Citation2020). Often, what is missing in these approaches is an understanding of how both users and designers work together, through a relational process, to ensure the IS is designed for inclusion and to ensure that systems of exclusion are not perpetuated at the same time.

Such exclusionary barriers according to Silver and Miller (Citation2003, 3) involve a “relational process of declining participation, solidarity, and access.” This is an important distinction from a limited discussion of social exclusion which focuses on barriers to IS access and its consequences (e.g., Dewan and Riggins Citation2005; Wei et al. Citation2011). This distinction, between barriers to technology access vs relational process, is important because it addresses the issue of existing (often exclusionary) processes and institutions. The focus on barriers to access, alone, is insufficient for understanding exclusion. Instead, a focus on relational processes provides insights into the larger context of processes and institutions that foster exclusion.

A relational approach also draws attention to who has the power to decide and implement processes i.e., choice of technology, channels for communication, level of support, choice of hardware, financial outlays, etc. This helps to understand when communities enact processes that bar or reduce others from participation in IS, and as a result, deny others autonomy that would have otherwise been available (Kvasny and Trauth Citation2003; Trauth and Howcroft Citation2006; Trauth, Joshi, and Yarger Citation2018). Relational processes help shift the power imbalance toward those in marginalized spaces (Kvasny and Trauth Citation2003). These shifts in power allow for agency in the use of IS for social change as experienced by those in marginal spaces.

Additionally, the relational processes that deter access (e.g., social norms, culture, traditional power structures etc.) perpetuate exclusionary practices (Kvasny and Trauth Citation2003). Researchers have sought to understand how inclusion of different disadvantaged communities through IS can be fostered. This research often focuses on specific disadvantaged groups (Pethig and Kroenung Citation2019) such as rural communities (Ashraf, Karlan, and Yin Citation2010; Hill, Troshani, and Burgan Citation2014; Venkatesh, Sykes, and Venkatraman Citation2014), refugees (e.g. Alam and Imran Citation2015; Andrade and Doolin Citation2016), indigenous populations (e.g., Letch and Carroll Citation2008) and those with physical disabilities (Newman et al. Citation2017; Pethig and Kroenung Citation2019). From a gender perspective, researchers have found the existence of “gendered spheres’’ in relation to the interaction between design and implementation of technology, among predominantly gendered roles such as nursing (Wilson Citation2002) as well as how power asymmetries in user voice can impact the exclusion and marginalization of women gamers thereby toxic and harmful experiences (Naidoo, Coleman, and Guys 2020).

When technology and design result in gender-based marginalization, it can give rise to a range of outcomes. From a fairness perspective, when designers develop a product for everyone, they aspire for the technology to be of use to individuals of all genders, ensuring that everyone has an equitable chance of achieving their goals (Stumpf et al. Citation2020). Many times products are designed with an implicit belief that they are gender-neutral i.e., they are not deliberately tailored toward any particular gender. This belief, however, does not necessarily guarantee true gender neutrality (Williams Citation2014). The Gates Foundation is a good example of this. During a crop-development project, they found an unintentional bias which made them more responsive to male farmers’ views, ignoring the needs of female farmers who were responsible for the subsistence crops consumed by the household. This prompted them to incorporate a gender responsive program (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Citation2012). Such awareness is often not found in technology and design development. Gender is often not taken into account when it’s considered irrelevant to users’ tasks (Williams Citation2014).

Financial inclusion for women

Financial inclusion has been defined as “a state in which all people who can use them have access to a full suite of quality financial services, provided at affordable prices, in a convenient manner, and with dignity for the clients” (The Center for Financial Inclusion Citation2018). Policy makers across the world are increasingly interested in financial inclusion due to its potential to enable poverty reduction, at a time when a growing number of people are being excluded from formal financial and banking institutions in developing countries (Blumenstock, Cadamuro, and On Citation2015; Wang and Guan Citation2017; Serbeh, Adjei, and Forkuor Citation2022).

Recent research shows that digital technologies could help with this. For example, mobile banking systems could offer financial services, thereby, cutting transaction costs, improving accessibility to users, and giving them more privacy and control over transactions (Aker et al. Citation2016; Holloway, Niazi, and Rouse Citation2017). Yet despite these potential benefits, the services and products have been unable to transform the situation of the most disadvantaged groups or close the financial inclusion gender gap in developing economies (Tiwari, Schaub, and Sultana Citation2019).

One of the many reasons is the lack of inclusive technology and service design (Kirisci et al. Citation2011). A 2023 report by Alliance for Financial Inclusion (Citation2023) suggests that despite the strong desire to engage with digital services, women in Ghana continue being marginalized by the lack of customized financial products designed to meet their unique needs. The idea that design shapes human behavior is not new and has gained attention in the literature especially in the field of behavioral economics, e.g. Kahneman (Citation2011) and Thaler and Sunstein (Citation2008). For example, behavioral economists show that even minor design biases such as default options substantially influence individual decision-making processes.

There are various hurdles developing a design that increases accessibility and usability by specific groups of women including time sensitivity, costs, technical challenges, and lack of guidelines (Goodman et al. Citation2006; Kirisci et al. Citation2011). This is mainly due to the delay in user input in product prototyping and testing. Furthermore, if the product design is at a later stage, making changes to the design will require more time and finance (Zitkus, Langdon, and Clarkson Citation2011).

Additionally, it is important to acknowledge that there are inequalities regarding women users’ abilities in using financial products and these are dependent on time and context. Inclusive design considers these and recognizes users’ needs as changing and situational (Heeks Citation2002; Whitaker Citation2020). It includes considering their skills as well as other aspects such as their gender, socio-economic status, digital literacy, and first language. All these can play a role in how an individual might use digital financial services. One of the mistakes design teams often make is using their own personal experiences to design for others (Whitaker Citation2020) while omitting the use of indigenous knowledge of users (Simons, Fleischmann, and Roy Citation2020). To help alleviate the problem, studies have suggested a model for inclusive design that incorporates (1) design intentions (2) design team demographics (3) design principles and (4) usability, to guide an inclusive design practice and prevent discrimination (Olbrich et al. Citation2015).

Gender-based disparities in developing countries like Ghana

The last decade has seen a significant rise in financial inclusion in Ghana, leading to more than twofold increase in account ownership from 2011 to 2021 (World Bank Citation2021). This growth is mainly due to the implementation of multiple policies designed to promote the adoption of DFS. Despite this high growth especially when contrasting it with other neighboring nations such as Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria, the gender gap has persistently widened (Alliance for Financial Inclusion Citation2023).

Before we discuss the factors that prevent women’s financial inclusion, let’s discuss how we see gender. We consider gender to be a social and cultural phenomenon that has real consequences for individuals, particularly women, who are generally considered in many societies as the “weaker sex”. Similar to other socially constructed phenomena, we view gender as an interplay of complex individual-level and structural level conditions. In Ghana, like many other countries, gender-based disparities are widely experienced with lower income groups generally experiencing them at higher levels compared to higher income groups (Steeves and Kwami Citation2019). The power difference between men and women in Ghanaian context translates into positions and privileges, with men, for example, having greater access to and control over resources. It has been found that the likelihood of buying mobile phones, engaging in training, and spending in internet cafés without any policing was higher among men, making access to digital technologies easier for them compared to their female counterparts (Kwami Citation2010). The difference in mobile phone ownership and mobile money account ownership between men and women in Ghana stands at 16% and 17% respectively (GSMA Citation2018).

Work environment has also been linked to digital resource access in Ghana. “While such access may seem gender-neutral at first, traditional gender roles, institutional structures and economic realities force disproportionate numbers of females into the informal sector where opportunities for access to new ICTs are limited” (Steeves and Kwami Citation2019, 117). In the same vein, Alozie and Akpan‐Obong (Citation2017) highlight that the cultural norms in Africa subjectively define “gendered spaces” more severely than in other societies, as such having digital technology controlled by men further increases the gender gap, which further excludes women.

Cultural norms further increase the plight of women, controlling division of roles, responsibilities, resources, access to education and so on (Adom et al. Citation2018). Research on 18 African nations including Ghana found that millions of women are not getting an education or different job roles due to household work and caregiving responsibilities (Arbache, Kolev, and Filipiak Citation2010). This is supported by the recent literacy data by the World Bank (Citation2021), which shows that marked differences exist in adult literacy rates between men and women in Ghana. Research has linked literacy rates (due to lower education) to time constraints imposed by caregiving responsibilities and reduced usage of technology among women (Alozie and Akpan‐Obong Citation2017).

In general, across Sub-Saharan Africa, digital and financial literacy (which constitute the basis of digitalization) and the awareness of DFS benefits remain low among women and girls (UNECA Citation2020). Studies on accelerating digital literacy among women, found that digital illiteracy discourages new users from using mobile internet and restricts the usage of existing users (GSMA Citation2015). Furthermore, low financial knowledge and confidence also deter women from taking a lead in managing their finances (Molinier Citation2019). Women often lack awareness regarding the services offered to them by formal financial institutions as well as the options that are available to them (Alliance for Financial Inclusion Citation2023). Therefore, there is a pressing need for financial information campaigns as a fundamental approach to increase financial literacy levels and thereby drive financial inclusion.

There are also cultural, legal and societal barriers to consider that restrict women’s access to entrepreneurial opportunities, bank accounts, and credits. A study in Ghana suggests that the gender gap in the ownership of land limits women’s economic participation with banks favoring land as a powerful form of collateral (Law and Development Partnership Citation2011). Women also face challenges in obtaining identity documents mandatory to open bank accounts and mobile accounts (GSMA Citation2016). Furthermore, women experience the threat of gender-based harassment as a result of mobile phone ownership, online communication, and gaining access to online financial services. For example, Ganle, Afriyie, and Segbefia (Citation2015). found that gender-based violence is often a consequence of conflict over control of microloans. Gender stereotypes also shape digital finance as well as impact those leading the digital financial services (UNECA Citation2020). It has been noted that “the faith in digital solutions in countries such as Ghana is fundamentally flawed …” (Alhassan Citation2004, 100), as the preexisting gender inequalities are often ignored (Kwami Citation2010).

Affordances approach to inclusive design

Our study uses the affordance approach to understand how an IS could be made more inclusive for low-income women. In this study, as in several others in the IS field, we adopt a affordances-centric view of design as developed in the work of Donald Norman (Citation1988). Affordance here is understood as “the perceived and actual properties of the thing … that determine just how the thing could possibly be used.” (Norman Citation1988, 9).

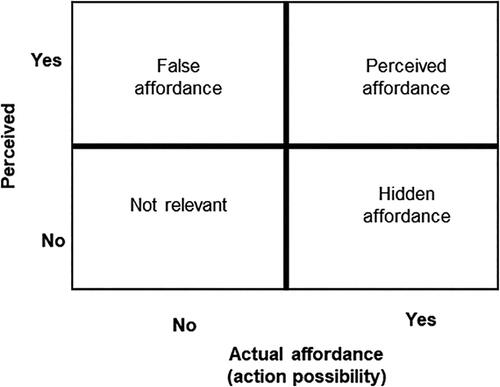

The affordances approach allows for equal emphasis on both the material aspects of technology design and the perception of users as shaped by their social and cultural use contexts. It takes into consideration both the objective and subjective aspects of affordances, that is, the inherent properties of artifacts like technology and the ability of actors to recognize and be able to act upon those. Given these considerations, we could have three different situations with regard to affordances – perceived (affordance exists and is also perceived), hidden (affordance is not perceived although one actually exists) or false (affordance is perceived although one does not actually exist) ().

Figure 1. Types of affordances.

Source: Adapted from Gaver (Citation1991)

Ultimately, from a design perspective, perceived affordances lead to the actual use of a technology. Therefore, good design should not only offer useful affordances but also make them easily perceivable by users based on their experience and other frames of reference they bring to their interaction with technology (Norman Citation1993, Citation1998, Citation2013).

Our study examines how the affordances of a standard technology (an IVR system) were redesigned or reconfigured to align with perceived affordances of low-income women in Ghana.

Materials and methods

Research design

Inspired by Volkoff and Strong (Citation2013), we examine: (1) How technology affordances arise in the strategies, structures, and processes of designing inclusive IS; (2) How these affordances are actualized; and (3) How actualizations of designed affordances lead to greater inclusivity. We take actualizations to mean the set of “actions taken by actors as they take advantage of one or more affordances through their use of technology to achieve immediate concrete outcomes in support of organizational goals” (Strong et al. Citation2014, 70).

Following Wynn and Williams (Citation2012), our methodology for data collection and analysis included the follow steps:

Step 1. Identify key events of the case we wish to explain, namely changes to the IVR to make it more inclusive.

Step 2. Identify key entities (technologies, people, context, etc.) and their relationships to the changes.

Step 3. Identify relevant technology affordances that help explain the changes. Examine how and why these technology affordances were or were not actualized, including any contextual conditions.

Step 4. Use data collected from multiple sources along with possible alternative explanations to assess the findings.

Step 5. Explore potential causal relationships (i.e., how technology affordances affect the IS).

Steps 1–2 of the methodology consisted of gathering data, through participant observations and documents, which were related to characteristics, relationships, interactions, and evolutions pertaining to the various entities involved in the design of the IVR. Steps 3-5 consisted primarily of further analysis of the data that were collected in steps 1-2 along with theory development.

Case background: The IVR system

This study is based on a project designed to test whether IVR was an appropriate channel for interacting with the female clients,Footnote2 through their mobile phones. They were clients of a savings and loans microfinance organization in Ghana – Spark Microfinance Ghana.Footnote3 The project team comprised of staff from the three main entities, Spark Microfinance Ghana, Spark Microfinance International, and the IVR technology supplier. They were technical staff who put together the messages and configured the IVR technology. The project team also monitored and evaluated project performance based on data from the IVR and core banking systems, interviews with clients and staff, and ad hoc client feedback collected by branch staff. Spark Microfinance Ghana found that there was a 35% gender gap between their male and female users, with only 30% of the women being active users. Its aim was to redesign their IVR strategy for greater inclusion and engagement of their low-income female clients.

Our study encompassed IVR usage by 28,028 low-income women belonging to 37 bank branches. Their usage was compared to that of 18,643 male savings clients to understand how redesign efforts supported financial inclusion of female users. The women were selected from across Ghana’s southern, central, and northern regions. They spoke various languages, with Twi, Ga, and Dagbani being the most prominent. English was not a commonly understood language among them, indicative of their lower literacy and socioeconomic status.Footnote4 Their ages ranged from 18 to 89 years old, with 40 being the average age. As entrepreneurial women, they owned small businesses and about 7% had an active business loan from Spark Microfinance Ghana. All the women had savings accounts, with an average balance of 129 Ghanaian Cedis (about USD$28) at the start of the research. To open these savings accounts, a starting balance of 10 Ghanaian Cedis (USD$2) was required as this product was designed for low-income individuals.

IVR systems can be programmed to provide a set of customized messages to address specific needs of customers, taking into consideration any structural disadvantages they may face in their use of the technology (e.g., adding visual communication for low literate groups). For this project, weekly messages were sent to the female clients during the project period. The messages contained financial literacy education and aimed to promote positive savings behaviors such as savings deposits and balance increases among clients. The messages were scripted by the project team in batches so that new understandings (e.g., feedback from the women) could inform the message development as the project unfolded. This iterative approach enabled a relational process between IVR designers and the women using it. The women found the process empowering as it gave them a “voice” and ensured that the IVR met their needs.Footnote5

As social context and contextual factors are critical for technology access and use, we also examined the relationship between the technology and its context of use (Williams and Edge Citation1996). Gender disaggregated data was used to evaluate how well the women were engaging with the IVR compared to men. The various sources of information (“feedback”) heavily informed the project’s development, including various redesigns made to the IVR system to tailor it to the women.

Data collection

We conducted the study over a two-year period which enabled us to cover the project development, implementation, and closure phases. During this period, one of the authors was embedded as a participant observer on the project team and co-led the data analysis and research aspects of the project.

We gathered strategic plans, technology and program reports, organizational charts, policies and procedures documents, product data, manuals, bank records, customer journey maps, documents on performance analytics, etc. They helped us understand the nuts and bolts of the IVR system’s composition and structure, along with the changes made to better engage low-income women.

The user evaluations consisted of transcribed phone interviews with 102 clients and 52 branch staff members. A coauthor led the evaluation process, established the research design, developed the interview protocol, and oversaw the interviews. Cluster sampling was used to select the users for interviews to ensure a proportional representation of various financial and call behaviors, while random sampling was used to select the branch staff members. The interviews were conducted during the middle and end of the project by a team of five staff members. The interviews were conducted in the local languages of the interviewees, including Twi, Ga, and Dagbani, and translated into English. These interviews were a critical source of information to the project team which used the user feedback to improve IVR's design.

Observational data were gathered over a year and a half through interactions that took place between the lead researcher and staff involved in the project. During this time, the first author worked alongside the project team and recorded notes in the form of observational memos. The observational data also included the project team’s written communications (emails and instant messaging). All these observational data were entered in NVivo software for analysis.

We also gathered and analyzed data on user engagement. Using frequencies, we analyzed the engagement rates of the women (n = 28,028) and compared them to the engagement rates of male clients (n = 18,643). Furthermore, we compared the gender gap in engagement rates for this project to other gender gaps in digital technologies, including mobile phone ownership and mobile banking. With these analytical methods, the project team gaged whether the project successfully engaged its intended user group.

Data analysis

As suggested by Wynn and Williams (Citation2012), we analyzed the data thematically and iteratively throughout the data collection process (see ). We applied descriptive and interpretive codes to our key themes (Miles and Huberman Citation1994) which included: changes to the IVR system, female client and contextual characteristics (including perceptions held by staff members), and perceived and actualized technology affordances. Mid-analysis, we revised our coding schematic to include a new theme “feedback.” After coding our documents, we examined these codes to identify patterns that provided insights into how various factors and relationships played a role in shaping the IVR system. In doing so, we categorized the codes into meta-codes (i.e., human-only changes, positive client feedback, technical challenges). We reviewed evidence from the various sources to triangulate the findings (Yin Citation2003). In addition, we used customer data related to financial savings from the organization to evaluate whether these interventions impacted savings (see for sample codes).

Table 1. Thematic and iterative analysis of data throughout the collection process.

Table 2. Sample codes by element and sub-theme.

Steps of the methodology are summarized below.

Step 1. Identify changes to the IVR system to improve inclusiveness. The analysis focused on identifying changes to improve, or with the intention to improve, call performance among low-income women. The following excerpt from a project communications logFootnote6 provides an illustrative example:

This is the message asking customers to change their language or hang up to keep their existing language? (Steve, project leader)

So, I think < the IVR supplier > said not to use that idea in the end because the clients we’re targeting < low-income women > wouldn’t understand that message, <it’s > giving them options (Leanne, project leader)

We identified 28 changes, mostly related to improving the call performance among the women. Twenty-one of the changes were coded “IT-associated changes” because they involved actions related to the algorithm or technical behavior of the system. The other seven changes did not involve algorithmic or technical changes directly, hence, we coded these “human-only changes.” Examples of IT-associated changes included: introducing a call-back feature, changing the call schedule, and adding branch staff as call recipients. Human-only changes included: changes to in-person communications, changes in the voice actors used for the recordings, and project staff changes.

Step 2. Identify relevant entities and their relationships to the changes. We identified 22 characteristics categories. Fifteen of them related to low-income women and/or contextual characteristics (e.g., unfamiliarity with IVR, price-sensitive, multiple languages spoken). Seven of them related to technical challenges (e.g., network down, calls repeating, call delays) which affected women’s use of the IVR (and trust of it).

Step 3. Identify technology affordances, along with conditions and affordance-related outcomes. For each IT-associated change identified in Step 1, we employed the process of retroduction to identify technology affordances that helped to explain these changes (Wynn and Williams Citation2012, Citation2020; Volkoff and Strong Citation2013). Retroduction involves starting with observable actions and events (i.e., changes made to the IVR) and working backward to identify the unobservable objects involved (i.e., the technology systems and features) and underlying mechanisms (causes of change). We identified technology affordances for each instance of change. Examples of identified affordances included the IVR system’s capacity to integrate with mobile network systems, recombine audio clips, and deliver automated messages (). These affordances had implications for if and how the women used the IVR and benefited from it.

Step 4. Test technology affordances as generative mechanisms. We examined data for plausible alternatives explanations and triangulated our findings using various sources (documents and observations). We compared perceived, hidden, and false affordances in our case to understand various conditions under which the IVR was designed for inclusion of low-income women (Gaver Citation1991).

We also examined if the organizations could design the IS for these women without the presence of various elements identified in Step 3. While our test data consisted of a limited sample from our case, the process was useful for refininig and validating our findings.

Step 5. Explore potential causal relationships. The analysis laid the foundations for identifying potential causal relationships between technology affordances and the changes that were made to the IVR to better include the women. The causal relationships we identified could be understood as probabilistic rather than deterministic.

Findings

We assess whether the IVR redesign increased engagement with the low-income Ghanaian women. We do this first by discussing data related to changes in time spent listening to messages, number of messages listened to, and call engagement were analyzed as indicators of redesign that support inclusion. Next, we discuss the key socio-technical aspects of the IVR were redesigned to become more inclusive for the low-income women. Finally, we assess the robustness of our findings and synthesize our results.

Designing for financial inclusion of low-income women

The data shows that the redesign made to the system was successful in reducing barriers to engagement among the low-income women. The metric for IVR engagement was the number of seconds that the clients listened to each IVR message. “Listening” was defined by the project team as 20 or more seconds since this cutoff was roughly the amount of time required for the main content of a message to play.

The analysis found that 79% of women listened to at least one message and 44% listened to at least six messages. Rates of call engagement were slightly higher for male clients, but only by roughly five percentage points. Furthermore, the women accounted for nearly half of all time spent listening to the messages, indicating that the IVR interactions were sufficiently adapted to be as relevant for women as for male clients. Lastly, the data showed that the IVR messages helped the women increase their savings balances by prompting them to save more. A significant positive correlation was found between savings balance increases and number of IVR messages listened to.Footnote7

Other observations related to attitudes and actions that suggested greater agency and independence for the women. These included:

Communicating in-person as follow-up. The IVR helped the women increase their connectedness and build social capital. More women displayed agency by reaching out and asking questions, both of which are actions that require confidence in themselves and in the institution.

Prompted to go to the branch or contact staff. The women felt confident to engage with formal financial institutions and had trust and confidence in institutional actors. This was evident the increased branch footfall, contact with staff, and ultimately, the increase in key metrics such as savings.

Feelings of emotional and relational connectedness. Greater willingness to engage with financial service providers builds social capital and trust in financial institutions. It also addresses issues of “gendered spheres” for IS where traditionally in Ghana, IS-related activities are considered a space for males only. Furthermore, this indicates the womens’ growing social networks and engagement in society.

Useful/educational messages. The knowledge acquired through the messages may also have had an empowering effect by enabling the women to take more informed decisions and actions about their finances, which would help address low financial literacy.

Added toll free hotline. The additional support was used by the women to gather more information about the IVR and other services including mobile banking, thus lowering potential concerns about their engagement with IS.

Applicable for “market women.” “Market women” are one of the most disadvantaged groups of women, i.e., low-income women who hawk petty goods in Ghana’s crowded outdoor markets. This menial work typically supports a hand-to-mouth existence. In our case, IVR brought increased financial services to these women.

Enablers of inclusivity

We found that changes toward greater inclusivity of the women involved three conditions: feedback, client and/or contextual characteristics, and technology affordances. These three conditions had intricate and interdependent relationships that unfolded in our analysis.

Feedback

The project team received feedback from the women about the project in three main ways. First, the clients provided feedback about the IVR calls especially when there were problems, e.g., the messages came in the wrong language. This type of feedback was collected in person or over the phone by branch staff and was subsequently channeled to the project team.

The second channel for obtaining feedback was from interviews that were conducted by the project team at two intervals during the project. These interviews sought to evaluate the project using a sample of 102 clients and 52 branch staff.

The third channel for obtaining feedback was from the project analytics. The data generated from the IVR calls were collated and displayed onto a live dashboard provided by the IVR technology supplier to the project team.

Additional data from the IVR system and the host organization’s core banking system were provided in spreadsheets for manual processing. These sources allowed the team to track various aspects of the project such as call performance and any correlations between calls and changes in savings account balances. If women’s call performance was found to be better or worse than average, the project team could examine the message scripts, the timing of delivery, and other aspects of the calls to derive clues about how to improve the women’s future call and savings performance.

When new feedback was received by the project team, the team considered this feedback in relation to other factors, such as characteristics of low-income women, the local and broader national context, and the technology affordances. After considering these factors jointly, and in relation to the project and its objectives, decisions were made by the project team on a case-by-case basis regarding whether or how to change the IVR system. The following excerpt from a project communications log provides an illustrative example:

Would it be worth exploring every other week?” (Leanne, project staff)

Yes, I think that’s right, given the < women > customers preference for Saturdays (was it?), we send out every other Saturday?” (Steve, project staff)

Can we group the client list into 2 so that 1 group receives it Saturday afternoon and evening, then Sunday (for remaining); then group 2 receives it the following weekend. Trying to figure out a way to get it all completed within weekends. (Leanne)

Perhaps we can ask whether they can really strive to complete it during the weekend, and therefore why some calls take longer than others? (Steve)

Client and contextual characteristics

Constraints faced by women played a prominent role in influencing changes to the IVR. Their active feedback offered guidance to the project team for making changes in a way that would increase the system’s relevance and appropriateness. As the transcript excerpt above shows, the timing of the calls changed midway through the project from weekdays to weekends. Several of the women had provided feedback to staff that they were too busy to listen to IVR messages during weekdays and would prefer receiving the calls on weekends. Upon receiving this feedback, the project team discussed concerns regarding how during weekdays, many of the women tended to be busy with their businesses during the day and with housework in the evening. Because of traditional social and gender norms (as previously described), women in Ghana have greater responsibility than men for carrying out domestic work (Owoo and Lambon-Quayefio Citation2021). Subsequently, a decision was made by the team to revise the call schedule, sending calls on weekends, and therefore providing women a more convenient time for receiving the calls.

Various technical challenges arose throughout the project that influenced redesign of the IVR system. For example, near the start of the project, the women complained about receiving repeated messages. After an investigation, adjustments were made to the IVR system to try to fix the problem. The project team adjusted the number of times the system would attempt call retries for undelivered calls. They also removed the language selection menu from being played before calls, which was used for clients without an assigned language. These changes were deliberately made to improve future call performance, especially among the women. Technical reliability was particularly important for the women since they had generally low digital skills, which combined with low literacy, manifested in a lack of confidence in technology and a propensity to disengage when problems arose (UNECA Citation2020; Abima et al. Citation2021).

IVR affordances for financial inclusion

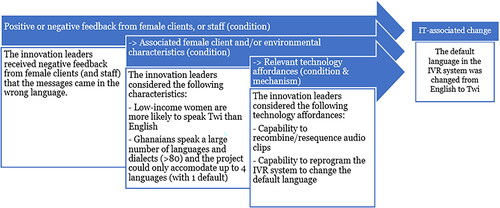

We found the technology affordances to have critical bearing on whether and/or how changes to the IVR technology and system took place to advance women’s inclusion. provides illustrative examples of changes made to the IVR based on women’s feedback. While low-income male clients shared many of the characteristics (low-income, low literacy, etc.), their experiences, however, differed due to societal and cultural barriers that make women more disadvantaged and vulnerable (Osabuohien and Karakara Citation2018). For example, while both low-income female and male clients were considered by the project team as resource constrained, the organization’s female clients were deemed disproportionately more resource constrained than their male counterparts, evident in the women’s lower average savings balances and loan sizes.

Table 3. Illustrative examples of changes made to the IVR based on women’s feedback.

Actualizing affordances through design

Once the three conditions – feedback, female client and/or contextual characteristics, and (perceived) technology affordances – had been considered by the project team, actionable changes to the IVR to make it more inclusive of low-income women were put forward for redesign. Our analysis found that actualization of technology affordances involved human and machine inputs such as programming code, altering technical structures, and sending communications. There was a complementary and interdependent relationship between the human and machine inputs. The IVR system, for example, was preprogrammed by software engineers to run code at specific times and retrieve available information when queried by clients using their phones (e.g., pressing 1, when prompted, to hear more information).

It was through this iterative relational process, whereby affordances were perceived and subsequently actualized, that the intended outcome was realized, i.e., the needs and preferences of the women were factored in the IVR system, enabling the women to engage with it more easily, thereby facilitating financial inclusion. These processes took into consideration the traditional barriers that the women faced and their unique contextual needs and identified specific design features needed to address them. In doing so, they helped shift the traditional balance of power (e.g., usually men took decisions about the IVR without female input) by creating opportunities for women to exercise influence on IVR-related decisions. Such feedback loops shifted power to the women by enabling them to actively shape and support tangible IVR-associated changes for inclusion.

Distinguishing types of affordances

In examining plausible alternative explanations for the changes that we observed (i.e., changes to the IVR to make it more inclusive of low-income women), the analysis followed Gaver (Citation1991) who distinguished between perceived, hidden, and false affordances. We observed all three in our data.

Our analysis showed that changes to the IVR to better include low-income women occurred when technology affordances were both perceived and actualized. False or hidden affordances, on the other hand, hindered change. There were numerous instances when the project team considered a technology affordance which was believed to deliver a desired outcome (i.e., improved call performance among low-income women). At times, this considered affordance presented a perceived, actionable affordance. At other times, it turned out to be a false affordance. Furthermore, the potentialities of hidden affordances could not be leveraged.

At times, non-technical members would query how the technologies might be redesigned to improve call performance among female clients (e.g., about possible changes to the messaging structure and schedule to better suit women’s needs and preferences). At times, these lines of questioning introduced novel ideas which prompted further exploration by the project team. In such discussions, the technical team members would help the non-technical members distinguish between perceived affordances and false affordances before decisions were made. The following excerpt from a project communications log provides an illustrative example:

Kisi, … I am looking at the dashboard for the Ghana project and a few things are unclear. I know one of the trees a few weeks ago was mislabeled (6-M4 is really 6-M3). What would be really helpful is if you could rename the tree titles to be consistent with the past. (For example, is the tree “Tracks” the messages from 6-M4? And the Thank you message is 7-M1?). (Leanne, project manager)

Leanne, I am unable to change the names of the trees since this is locked in the system (Kisi, project leader and IVR vendor)

Kisi, related to my last question, Steve and I were just chatting about the message schedule. It seems messages are taking longer than a day or two to get to the full list of recipients. We are wanting to have the messages go out only on the weekend from now on. We also don’t want clients to hear messages more frequently than 1 week (there needs to be a break of at least 6 days between messages). Perhaps you can help us understand if messages going out on the weekend will be quicker or if we can continue to expect delays. (Leanne)

Table 4. Change outcomes by affordance type.

Associations between conditions and outcomes

To assess the relationships among the three conditions – feedback, female client and/or contextual characteristics, and technology affordances, we analyzed their presence and their associations.

Feedback was a condition for all types of changes we identified. The feedback provided by clients and staff members led to consequential outcomes. When positive feedback and complaints were associated with client and/or contextual characteristics, the project leaders considered the barriers and opportunities that were specific to low-income women (e.g., ways to address low levels of literacy and numeracy). They also considered what was technically feasible for removing the barriers and exploiting the opportunities. We provide the following vignette to show how the codes we derived in our analysis () related across three conditions.

When some clients complained that the messages had been delivered in the wrong language, the project leaders discussed the situation and how they might fix this problem by tailoring the IVR system. Clients who had not selected a preferred language using the language menu were receiving the messages in English as the default language. This is because English had been identified at the start of the project as the language that most clients would be familiar with, especially compared to the many regional local languages. During the decision-making process, the project leaders discussed how the low-income women generally had low levels of formal education and were therefore less likely to speak English than Twi (the most widely spoken local dialect in Ghana), especially compared to the men, given traditional barriers to access to education and lack of literacy. The leaders also discussed that a contextual challenge for the project was that Ghana was a country of many languagesFootnote8 and most of these languages could not be accommodated in the project due to resource constraints. Since the project could only accommodate the top four commonly spoken languages by clients (English, Twi, Ga, and Dagbani), a decision was made by the project leaders between the two most commonly spoken languages among clients: English and Twi. Twi was believed to be more appropriate for low-income women thus the IVR system was redesigned to make Twi the default language instead of English.

In this case, the first two conditions – feedback and female client and/or contextual characteristics played key – influencing roles in generating the change to the IVR system to better include low-income women. The decision to make Twi the default language of the IVR included the low-income women “by default”. The feedback served as the trigger and the characteristics served as a consequential factor in the decision-making process that led to the change.

While feedback was always a critical condition for bring about IT-associated change in the IVR, we did not find it to be a necessary condition. In our testing, we considered and identified various plausible alternatives that could have filled the role of feedback in the development of IVR. For instance, alternative sources of information such as external reports might have provided the project team with new valuable insights on reconfiguring IVR to make it more inclusive.

Similar to our findings on feedback, we found there is an association between the development of inclusive IVR and the consideration of one or more client and/or contextual characteristics, either directly or indirectly.Footnote9 In extending this logic, we assert that the consideration of one or more client and/or contextual characteristics in the decision-making process is a condition for generating inclusive IS.

Finally, there is an association between any IT-associated change and the presence of one or more perceived technology affordances. On the other hand, “human-only changes” as listed in we not dependent on technology affordances. summarizes the associations we found in our data between the conditions and outcomes.

Table 5. Associations between elements and change outcomes.

Discussion

In understanding and leveraging technology affordances, our project team strategically adjusted the IS to better suit the needs of low-income women. We show how technology affordances serve as generative mechanisms when recognized and leveraged, consequently impacting existing power dynamics – specifically, empowering women through greater inclusion.

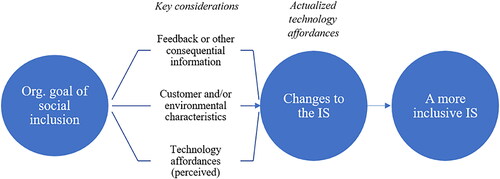

Using the wrong language feedback example from the case, illustrates the four stage process we identify for designing a more inclusive IS. Stage 1 entails obtaining feedback from the users of the technology as well as the support staff who enable its use. In Stage 2 the demographic, socioeconomic, and other characteristics of the environment are considered. In Stage 3 they are used to identify and actualize relevant technology affordances. Finally, in Stage 4 once such affordances are actualized, the IS might become more inclusive by addressing the issues identified through the initial feedback in Stage 1.

spotlights the significance of feedback, environmental factors, and affordances as the conditions for developing a more inclusive IS design. All three influenced project leaders’ decisions on whether and how to make the IS more inclusive for women, resulting in more targeted and effective financial inclusion initiatives.

Our relational process-based approach to identifying technology affordances highlights the importance of processes in generating change. Organizational change toward greater inclusion becomes feasible when processes can be reassessed and adjusted to respond dynamically to relevant social contexts. Our study shows how technology affordances within the IS design process play a generative role through iterative and relational processes.

Operationalizing changes to the IS involves perceiving technology affordances and then actualizing them. Affordances are actualized based on organizational resources, reflecting the organization’s willingness and capability to enact changes. By actualizing technology affordances, the IS could be (re)designed to be more inclusive, with significant implications for organizational transformation. As the IS evolves to become more inclusive, so does the organization, potentially leading to more effective engagement with disadvantaged groups ().

Table 6. Considerations for designing an IS for financial inclusion.

presents a simplified model illustrating potential causal links between an organization’s goals for financial inclusion, design changes to its IS, and the realization of a more inclusive IS. It suggests that the link between an organization’s goals of social inclusion and the design changes to its IS are driven by user feedback and other consequential information from organization members, characteristics of the users and their social and other environmental characteristics, and the affordances the designers and users perceive the technology to have. We believe this model can be applied to any IS where an organization has a goal of financial inclusion through the design and development of a more inclusive IS. To implement this model, we offer practical guidelines (see ).

Conclusions

We contribute to the digital financial inclusion literature in three significant ways.

Firstly, we emphasize the importance of understanding and actively addressing social context, such as traditional power imbalances and limited resources, when designing and implementing IS. We show how leveraging of technology affordances can mitigate these structural disadvantages and drive organizational change toward financial inclusion. Our study showcases how organizational actors strategically leverage technology affordances to tailor the IS to the needs of low-income women.

Secondly, we contribute by presenting a relational process-oriented approach to inclusion. We focus on how the IS could address barriers and empower women in their financial inclusion journey. Our study highlights how relational processes influence decision-making and IS implementation, leading to greater adaptation of the IS to the context faced by women. These processes foster greater agency and inclusion for women, with inclusion becoming ingrained in all facets of the IS and evolving iteratively.

Thirdly, we stress the importance of taking a holistic view to understand inclusion and exclusion processes in technology design, adoption, and use. Drawing from the sociotechnical tradition of IS research, we emphasize the intricate interplay between technology artifacts and social and organizational contexts. Factors like gender and socioeconomic conditions significantly shape sociotechnical outcomes and must be considered in explanations of technological phenomena like digital financial inclusion.

Our research also contributes to the broader IS literature, particularly regarding technology affordances. Firstly, it provides insights into embedding inclusion within IS through routine practices leveraging technology affordances to better address the needs of low-income women. Secondly, it underscores the role of technology affordances in generating inclusive IS during the design and use stages. Lastly, it demonstrates how technologies, and their affordances can yield consequential outcomes for meeting inclusion objectives.

Practically, our research offers insights for organizations seeking to leverage digital technologies to enhance financial inclusion objectives. It sheds light on how technology affordances can facilitate (re)designing IS to better serve disadvantaged groups and provides practical guidelines for achieving inclusivity.

While we acknowledge that technology affordances may not always lead to enhanced financial inclusion within IS, and that our findings capture only the aspect of gender disparities, our research lays the groundwork for future exploration in different contexts to uncover additional elements of IS design for financial inclusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We take “financial inclusion IS” to be an outcome of design changes whereby standardized, or off-shelf technologies are adjusted to allow greater flexibility of use and engagement among those who traditionally would have been excluded (Kvasny and Trauth Citation2003).

2 “Female clients” here and in other parts of the manuscript refers to the low-income women users.

3 A pseudonym.

4 English is commonly spoken by wealthier people in Ghana who had access to English-based education and/or work (Afrifa, Anderson, and Ansah Citation2019).

5 Below are the categories of actions and feelings that were used as prompts. (The list was made after analyzing the interview data from the project evaluation.) Several of the feelings listed suggest there were feelings related to a sense of empowerment (pride, being valued, inspired). Categories of Prompted Actions: save/make a deposit, check my account balance, get a loan/save to get a loan, visit a bank branch, plan, rethink savings, remember my financial goals; Categories of Prompted Feelings: encouragement, inspiration, excitement, security, uniqueness, assurance, being valued, pride, surprise.

6 Pseudonyms have been used for our respondents throughout the article.

7 The correlation between engagement and savings was tracked by the team, through their in-built systems.

8 There are 80 native languages in Ghana, according to WorldAtlas.com (https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are-spoken-in-ghana.html, accessed January 21, 2019). When local dialects are included, the number of spoken languages and dialects in Ghana is 250, according to the Ghana Embassy (http://www.ghanaembassy.nl/index.php/faqs-mainmenu-25/121-what-is-the-official-language-of-ghana.html, accessed January 21, 2019).

9 We identified some changes (e.g., a switch in mobile network operator, an SMS sent to clients to remedy a programming error, and a change in reporting format) that had an indirect association with the organization’s goals around financial inclusion, i.e., these changes aimed at improving call performance generally, including the female clients.

References

- Abima, B., B. Engotoit, G. M. Kituyi, R. Kyeyune, and M. Koyola. 2021. Relevant local content, social influence, digital literacy, and attitude toward the use of digital technologies by women in Uganda. Gender, Technology and Development 25 (1):87–111. doi:10.1080/09718524.2020.1830337.

- Adeola, O. ed. 2020. Empowering African women for sustainable development: Toward achieving the United Nations’ 2030 goals. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Adom, K., I. T. Asare-Yeboa, D. M. Quaye, and A. O. Ampomah. 2018. A critical assessment of work and family life of female entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa: Some fresh evidence from Ghana. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 25 (3):405–27. doi:10.1108/JSBED-02-2017-0063.

- African Union. 2018. The African women’s decade: Grassroots approach to gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE). Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.chr.up.ac.za/images/researchunits/wru/documents_/the_african_womens_decade.pdf

- Afrifa, G. A., J. A. Anderson, and G. N. Ansah. 2019. The choice of English as a home language in urban Ghana. Current Issues in Language Planning 20 (4):418–34. doi:10.1080/14664208.2019.1582947.

- Aker, J. C., R. Boumnijel, A. McClelland, and N. Tierney. 2016. Payment mechanisms and antipoverty programs: Evidence from a mobile money cash transfer experiment in Niger. Economic Development and Cultural Change 65 (1):1–37. doi:10.1086/687578.

- Alam, K., and S. Imran. 2015. The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants: A case in regional Australia. Information Technology & People 28 (2):344–65. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2014-0083.

- Alhassan, A. 2004. Development communication policy and economic fundamentalism in Ghana. Tampere, Finland: University of Tampere.

- Alliance for Financial Inclusion. 2023. The role regulators play in closing financial inclusion gender gap: A case study of Ghana. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.afi-global.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/The-Role-Regulators-Play-in-Closing-the-Financial-Inclusion-Gender-Gap-Ghana_v2.pdf

- Alozie, N. O., and P. Akpan‐Obong. 2017. The digital gender divide: Confronting obstacles to women’s development in Africa. Development Policy Review 35 (2):137–60. doi:10.1111/dpr.12204.

- Andrade, A. D., and B. Doolin. 2016. Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. MIS Quarterly 40 (2):405–16. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.2.06.

- Arbache, J. S., A. Kolev, and E. Filipiak. 2010. Gender disparities in Africa’s labor market. Washington, DC: World Bank. Accessed December 14, 2021. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/c5b12a6b-4064-532e-86f4-a87219610f36.

- Armstrong, D. J., C. K. Riemenschneider, and L. G. Giddens. 2018. The advancement and persistence of women in the information technology profession: An extension of Ahuja’s gendered theory of IT career stages. Information Systems Journal 28 (6):1082–124. doi: 10.1111/isj.12185.

- Ashraf, N., D. Karlan, and W. Yin. 2010. Female empowerment: Impact of a commitment savings product in the Philippines. World Development 38 (3):333–44. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.05.010.

- Atkinson, A. B., and E. Marlier. 2010. Analyzing and measuring social inclusion in a global context. New York: United Nations. Accessed January 18, 2022. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/.

- Aziz, A., and U. Naima. 2021. Rethinking digital financial inclusion: Evidence from Bangladesh. Technology in Society 64:101509. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101509.

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. 2012. Creating gender-responsive agricultural development programs: An orientation document. Accessed September 18, 2023. http://docs.gatesfoundation.org/learning/documents/gender-responsive-orientation-document.pdf

- Blumenstock, J., G. Cadamuro, and R. On. 2015. Predicting poverty and wealth from mobile phone metadata. Science (New York, NY) 350 (6264):1073–6. doi:10.1126/science.aac4420.

- Buteau, S., P. Rao, and F. Valenti. 2021. Emerging insights from digital solutions in financial inclusion. CSI Transactions on ICT 9 (2):105–14. doi:10.1007/s40012-021-00330-x.

- Dewan, S., and F. J. Riggins. 2005. The digital divide: Current and future research directions. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 6 (12):298–337. doi:10.17705/1jais.00074.

- Dupas, P., and J. Robinson. 2013. Savings constraints and microenterprise development: Evidence from a field experiment in Kenya. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5 (1):163–92. doi:10.1257/app.5.1.163.

- Fountain, J. E. 2000. Constructing the information society: Women, information technology, and design. Technology in Society 22 (1):45–62. doi:10.1016/S0160-791X(99)00036-6.

- Fox, M. F., D. G. Johnson, and S. V. Rosser. eds. 2006. Women, gender, and technology. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Fuchs, C., and E. Horak. 2008. Africa and the digital divide. Telematics and Informatics 25 (2):99–116. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2006.06.004.

- Gammage, S., A. Kes, L. Winograd, N. Sultana, S. Hiller, and S. Bourgault. 2017. Gender and digital financial inclusion: What do we know and what do we need to know. Accessed 5, 2024. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Gender-and-digital-financial-inclusion.pdf

- Ganle, J. K., K. Afriyie, and A. Y. Segbefia. 2015. Microcredit empowerment and disempowerment of rural women in Ghana. World Development 66:335–45. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.08.027.

- Gaver, W. W. 1991. Technology affordances. In CHI ‘91: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 79–84. New York: ACM.

- Gomber, P., J. A. Koch, and M. Siering. 2017. Digital finance and FinTech: Current research and future research directions. Journal of Business Economics 87 (5):537–80. doi:10.1007/s11573-017-0852-x.

- Goodman, J., H. Dong, P. Langdon, and P. J. Clarkson. 2006. Increasing the uptake of inclusive design in industry. Gerontechnology 5 (3):140–9. doi:10.4017/gt.2006.05.03.003.00.

- GSMA. 2015. Bridging the gender gap: Mobile access and usage in low and middle-income countries. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/GSMA_Bridging-the-gender-gap_Methodology3.2015-1.pdf

- GSMA. 2016. Mandatory registration of prepaid SIM cards: Addressing challenges through best practice. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.gsma.com/publicpolicy/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GSMA2016_Report_MandatoryRegistrationOfPrepaidSIMCards.pdf

- GSMA. 2018. The mobile economy: Sub-Saharan Africa. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/sub-saharan-africa

- GSMA. 2019. Connected women: The mobile gender gap report 2019. Accessed January 11, 2020. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/GSMA-The-Mobile-Gender-Gap-Report-2019.pdf

- Heeks, R. 2002. Information systems and developing countries: Failure, success, and local improvisations. The Information Society 18 (2):101–12. doi:10.1080/01972240290075039.

- Hendriks, S. 2019. The role of financial inclusion in driving women’s economic empowerment. Development in Practice 29 (8):1029–38. doi:10.1080/09614524.2019.1660308.

- Hill, S. R., I. Troshani, and B. Burgan. 2014. Broadband adoption in regional and urban households. Journal of Computer Information Systems 54 (3):57–66. doi:10.1080/08874417.2014.11645704.

- Holloway, K., Z. Niazi, and R. Rouse. 2017. Women’s economic empowerment through financial inclusion: A review of existing evidence and remaining knowledge gaps. Accessed July 6, 2024. https://poverty-action.org/sites/default/files/publications/Womens-Economic-Empowerment-Through-Financial-Inclusion.pdf

- Johnson, D., J. Clarkson, and F. Huppert. 2010. Capability measurement for inclusive design. Journal of Engineering Design 21 (2–3):275–88. doi:10.1080/09544820903303464.

- Joshi, K. D., E. Trauth, L. Kvasny, A. J. Morgan, and F. C. Payton. 2017. Making black lives matter in the information technology profession: Issues, perspectives, and a call for action. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems 48 (2):21–34. doi:10.1145/3084179.3084183.

- Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kalba, K. 2016. Explaining the mobile money adoption-usage gap. Digiworld Economic Journal 103:113–43.

- Kirisci, P. T., P. Klein, M. Modzelewski, M. Lawo, Y. Mohamad, T. Fiddian, C. Bowden, A. Fennell, and J. O. Connor. 2011. Supporting inclusive design of user interfaces with a virtual user model. In Universal access in human-computer interaction: Users diversity, ed. C. Stephanidis, 69–78. Berlin: Springer.

- Klapper, L., and P. Dutt. 2015. Digital financial solutions to advance women’s economic participation. Accessed July 6, 2024. https://www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/documents/03-Digital%20Financial%20Solution%20to%20Advance%20Women….pdf.

- Kolade, O., V. Odumuyiwa, S. Abolfathi, P. Schröder, K. Wakunuma, I. Akanmu, T. Whitehead, B. Tijani, and M. Oyinlola. 2022. Technology acceptance and readiness of stakeholders for transitioning to a circular plastic economy in Africa. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 183:121954. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121954.

- Kvasny, L., and E. M. Trauth. 2003. The digital divide at work and home: The discourse about power and underrepresented groups in the information society. In Global and organizational discourse about information technology, eds. E. H. Wynn, E. A. Whitley, M. D. Myers, and J. I. DeGross, 273–91. Berlin: Springer.

- Kwami, J. D. 2010. Information and communication technologies for development and gendered realities in the South: Case studies of policy and practice in Ghana. Doctoral diss., University of Oregon.

- Law and Development Partnership. 2011. Access to credit for women entrepreneurs in Ghana: Gender perspective of secured lending initiatives. Accessed December 12, 2021. http://www.lawdevelopment.com

- Letch, N., and J. Carroll. 2008. Excluded again: Implications of integrated e-government systems for those at the margins. Information Technology & People 21 (3):283–99. doi:10.1108/09593840810896037.

- Light, B., G. Fletcher, and A. Adam. 2008. Gay men, gaydar and the commodification of difference. Information Technology & People 21 (3):300–14. doi:10.1108/09593840810896046.

- Mbarika, V. W., F. C. Payton, L. Kvasny, and A. Amadi. 2007. IT education and workforce participation: A new era for women in Kenya? The Information Society 23 (1):1–18. doi:10.1080/01972240601057213.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mingers, J., A. Mutch, and L. P. Willcocks. 2013. Critical realism in information systems research. MIS Quarterly 37 (3):795–802. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2013/37:3.3.

- Molinier, H. 2019. Leveraging digital finance for gender equality and women’s empowerment (Working paper). New York: UN Women. Accessed August 15, 2020. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2019/09/discussion-paper-leveraging-digital-finance-for-gender-equality-and-womens-empowerment

- Mumporeze, N., and M. Prieler. 2017. Gender digital divide in Rwanda: A qualitative analysis of socioeconomic factors. Telematics and Informatics 34 (7):1285–93. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2017.05.014.

- Naidoo, R., K. Coleman, and C. Guyo. 2020. Exploring gender discursive struggles about social inclusion in an online gaming community. Information Technology & People 33 (2):576–601. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2019-0163.

- Newman, L., K. Browne-Yung, P. Raghavendra, D. Wood, and E. Grace. 2017. Applying a critical approach to investigate barriers to digital inclusion and online social networking among young people with disabilities. Information Systems Journal 27 (5):559–88. doi:10.1111/isj.12106.

- Norman, D. A. 1988. The psychology of everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

- Norman, D. A. 1993. Things that make us smart. Reading, MA: Addision-Wesley.

- Norman, D. A. 1998. The invisible computer: Why good products can fail, the personal computer is so complex and information appliances are the solution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Norman, D. A. 2013. The design of everyday things. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Olatokun, W. M. 2008. Gender and national ICT policy in Africa: Issues, strategies, and policy options. Information Development 24 (1):53–65. doi:10.1177/0266666907087697.

- Olbrich, S., E. M. Trauth, F. Niederman, and S. Gregor. 2015. Inclusive design in is: Why diversity matters. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 37:767–82. doi:10.17705/1CAIS.03737.

- Osabuohien, E. S., and A. A. Karakara. 2018. ICT usage, mobile money and financial access of women in Ghana. Africagrowth Agenda 15 (1):14–18.

- Owoo, N. S., and M. P. Lambon-Quayefio. 2021. Mixed methods exploration of Ghanaian women’s domestic work, childcare and effects on their mental health. PloS One 16 (2):e0245059. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245059.

- Patrick, V. M., and C. R. Hollenbeck. 2021. Designing for all: Consumer response to inclusive design. Journal of Consumer Psychology 31 (2):360–81. doi:10.1002/jcpy.1225.

- Pethig, F., and J. Kroenung. 2019. Specialized information systems for the digitally disadvantaged. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 20:1412–46. doi:10.17705/1jais.00573.

- Salvador, A. C., S. Rojas, and T. Susinos. 2010. Weaving networks: An educational project for digital inclusion. The Information Society 26 (2):137–43. doi:10.1080/01972240903562795.

- Serbeh, R., P. O. W. Adjei, and D. Forkuor. 2022. Financial inclusion of rural households in the mobile money era: Insights from Ghana. Development in Practice 32 (1):16–28. doi:10.1080/09614524.2021.1911940.

- Silver, H., and S. M. Miller. 2003. Social exclusion. Indicators 2 (2):5–21. doi:10.1080/15357449.2003.11069166.

- Simons, R. N., K. R. Fleischmann, and L. Roy. 2020. Leveling the playing field in ICT design: Transcending knowledge roles by balancing division and privileging of knowledges. The Information Society 36 (4):183–98. doi:10.1080/01972243.2020.1762270.

- Steeves, H. L., and J. D. Kwami. 2019. Social context in development communication: Reflecting on gender and information and communication technologies for development in Ghana. Asia Pacific Media Educator 29 (2):106–22. doi:10.1177/1326365X19856139.

- Stillman, L., and T. Denison. 2014. The capability approach community informatics. The Information Society 30 (3):200–11. doi:10.1080/01972243.2014.896687.

- Strong, D., O. Volkoff, S. A. Johnson, L. R. Pelletier, B. Tulu, I. Bar-On, J. Trudel, and L. Garber. 2014. A theory of organization-EHR affordance actualization. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 15 (2):53–85. doi:10.17705/1jais.00353.