Abstract

The urban condition, as we know it, might be becoming obsolete: the continuous growth of urban textures points toward a total urbanization of the world. Together with the superimposition of electronic and virtual spaces in the city, this urban expansion furthers a radical alteration of our daily urban experiences, which in turn transforms the parameters of intervention for aesthetic production. This paper aims to outline three components of this aesthetic problem: 1) trans-industrial change, understood as the shift from industrial to postindustrial stages considered as in an ongoing process); 2) the specificities of aesthetic thought, understood as an independent mode of approaching the world differing from mathematical, political, or philosophical thought; and 3) realms of visibility, as informed by the digital and new media revolutions, which are reshaping our modes of communication. To discuss the parameters of this problem, I will draw from a number of examples originating in the United Kingdom, a territory whose cities were at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but which have witnessed a spectacular shift to a global service economy in the late twentieth century: as such, Great Britain offers a metonymical entry into the global context that constitute the framework for this reflection. Within this framework, crucially, the paper identifies the interstice, a crevice between two things, and interstitial space as a privileged locus of aesthetic intervention to be explored within the new terms of a total urbanization. It will evoke the interstice's capacity to divert the flattening impact of homogenizing tendencies and unveil new material and spiritual objects in the urban fabric. Finally, with the work of the Northern Ireland-based artist Conor McFeely, it will offer an artistic articulation addressing head on the problem of imagination in the context of the multilayered and digital/virtual urban becoming.

Industrial Foundations: The City of Cain

To set the tone of his first chapter focusing on “the revolution in technique,” in his 1947 study Art and the Industrial Revolution, Francis Klingender quoted the enthusiastic words of Daniel Defoe from his 1724–1727 Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain:

… every New View of Great Britain would require a New Description; the Improvements that increase, the New Buildings erected, the Old Buildings taken down; New Discoveries in Metals, Mines, Minerals; new Undertakings in Trade; Inventions, Engines, Manufactures, in a Nation, pushing and improving as we are; These Things open new Scenes every Day, and make England especially shew a new and differing Face in many Places, on every Occasion of Surveying it.Footnote1

Technological revolutions were abruptly changing the eighteenth-century British landscape. A remote rural gorge of potentially pleasant picturesque attribute became the launching platform of a global transformation when Abraham Darby (1678–1717) successfully managed the smelting with coke in the first decades of the eighteenth century in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire. The valley symbolically became the recipient of the first large-scale cast-iron bridge commissioned by Abraham Darby III (1750–1789), designed by Thomas Farnolls Pritchard (ca. 1723–1777), and completed in 1779.Footnote2 Fifty years later, as the first railway lines opened a realm of radically different spatial and temporal experience to human perception, a young visitor from Germany shared Defoe's awe, if not his enthusiasm:

I once went into Manchester with such a bourgeois, and spoke to him of the bad, unwholesome method of building, the frightful condition of the working-people's quarters, and asserted that I had never seen so ill-built a city. The man listened quietly to the end, and said at the corner where we parted: “And yet there is a great deal of money made here, good morning, sir.”Footnote3

Hence did Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) summarize the dual perplexity of the industrial city as observed in one of its historical cradles in the mid-nineteenth century. Manchester had been transformed through a combination of seemingly opposite qualities: utter human squalor and vast surplus value.

A century later, while the Salford-based painter L. S. Lowry (1887–1976) captured the charm and poetics of the factory environment (see, for instance, Going to Work, 1943, in the Imperial War Museum, London), it took another foreigner to denounce the residual debilitating effect of the northern industrial urban environment. In Michel Butor's L'emploi du temps [Passing Time], published in 1956, a young French man arrives in an imagined northern England city named Bleston. He is soon ill at ease in this archetypal industrial town:

From the very first I had felt this town to be unfriendly, unpleasant, a treacherous quicksand; but it was during these weeks of routine, as I gradually felt its lymph seeping into my blood, its grip tightening, my present existence growing rudderless, amnesia creeping over me, that began to harbour that passionate hatred towards it which, I am convinced, was in part a sign of my contamination by it, a kind of personal animosity, since although I am well aware that Bleston is not unique of its kind, that Manchester or Leeds, Newcastle or Sheffield, or Liverpool (which also, I am told, possesses a modern cathedral that is not uninteresting) or else, no doubt, some modern American town such as Pittsburgh or Detroit, would have had a similar effect on me, it seems to me that Bleston exaggerates certain characteristics of such urban centres, that no other is as cunning or as powerful in its witchcraft.Footnote4

The city is a sorceress, whose powers are linked in the novel to a mesmerizing window located in the ancient cathedral, known as the “murderer's window.” The subject is the biblical figure of Cain, the first murderer of humanity, and while the window of his brother, Abel, had not survived the demands of time, Cain's life and offspring are depicted in a series of images evoking in particular Cain as a builder of cities, his grandsons Yabal as father of weavers, Yubal of musicians, and Tubal-cain as of all who work with metals. For, as the priest guiding Jacques Revel, the narrator in the novel, among the iconography explains, the artist honored the father of all arts in Cain.Footnote5

This dual nature of the Industrial Revolution city did not go unnoticed. At the time Engels was turning his attention to the coming of age of what another critical mind, Lewis Mumford (1895–1900), dubbed the paleotechnic phase,Footnote6 the neo-Gothic architect, artist, and critic Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852) published a drastic attack on the mutilations caused to the English city by the Industrial Age. His attack on Victorian architecture, society, and industry was published under the title Contrasts—Or, a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries and Similar Buildings of the Present Day. Shewing the Present Decay of Taste Accompanied by Appropriate Text. The progress of the present days was judged to amount to a blind destruction of a noble historical heritage:

This great age of improvement and increased intellect … is asserted to have produced results which have never been equalled; and, puffed up by their supposed excellence, the generation of this day look back with pity and contempt on all that passed away before them.

In some respects, I am willing to grant, great and important inventions have been brought to perfection: but, it must be remembered, that these are purely of a mechanical nature; and I do not hesitate to say, that as works of this description progressed, works of art and productions of mental vigour have declined in a far greater ratio.Footnote7

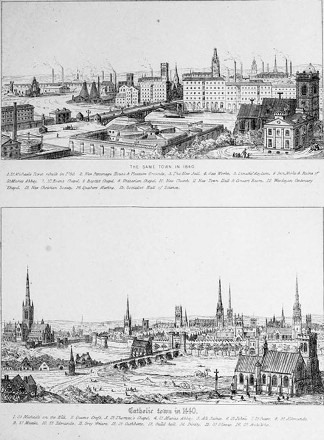

In one of the plates of the book, an imagined visual comparison between a “Catholic town” depicted in the mid-fifteenth century and its reformed state four centuries later underlined the extent of industrial disfiguration ().Footnote8

Figure 1 Augustus W. N. Pugin, “Catholic town in 1440” (lower) and “The same town in 1840” (upper). Unnumbered plate in Contrasts—Or, a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries and Similar Buildings of the Present Day. Shewing the Present Decay of Taste Accompanied by Appropriate Text (1836).

The elegant spires of pointed architecture have been replaced by the smoking chimneys of proliferating mills.Footnote9 The harmonious bird's-eye view has been defaced by a wall of stern buildings. In the front-right-hand corner, a medieval chapel has been similarly vandalized by an annex in the classical style. A jail in the shape of Jeremy Bentham's (1748–1832) panopticon occupies the foreground of the drawing. Moral turpitude is further emphasized by the numerous divisive groups listed in the caption: Baptist, Unitarian, Quakers, Socialists.Footnote10 The origins of the present decadence are to be found in the Reformation, King Henry VIII's abandonment of the Catholic faith, and the creation of the Church of England in the sixteenth century. In the end, history and a deviant religion have guided man and his urban environment to a fallacious destiny.

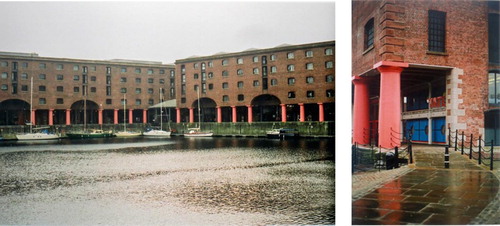

Yet at the end of the twentieth century, the industrial architecture which Pugin condemned as barbarous has seen its functions being disposed of while gaining a cachet that makes it the very equal of its Gothic predecessors. Spires and chimneys have become equal in the palimpsest city—where new buildings constantly superpose themselves on existing ones—brothers in arms as witnesses to a flavorsome past to be appreciated in the present. The source of this uncanny parallel, wherein medieval architecture, neo-Gothic revivals, Victorian fondness for historic architectural quotes, and nineteenth-century industrial warehouses all coalesce in a picturesque melting-pot, are situated in the second half of the century's global industrial transformation and the displacement of modernity's ideals.Footnote11 The renunciation of a teleological belief in humanity's unilateral progress enabled a juxtaposition of urban visions, which had long been seen as oppositional. This “postmodern” superposition has been clinically captured by the British photographer John Davies (b. 1949) in a series of photographs taken from the early 1980s onward, but more specifically in his Metropoli project (2000–). In this series, Victorian churches are bordered by motorway junctions (Former Holy Jesus Hospital, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 2002), Lancashire mills cohabit with textile museums (In the Wake of King Cotton),Footnote12 modernist postwar architecture glistens in dynamic élan (Hotel Piccadilly, Manchester, 2002), and former trading canals serve as marinas for a changing industry (Gas Street Basin, Birmingham, 2000). The extent of the transformation is such that Defoe's words could be appropriately transferred to our present time: “a new and differing Face in many Places, on every Occasion of Surveying it.”

These radical transformations of former industrial bastions indicated a shift from production to consumption.Footnote13 As Malcolm Miles and Steven Miles have underlined, former production spaces in the West in the late twentieth century could survive through becoming shopping or cultural assets for the tourism industry: spaces to be consumed.Footnote14 These new urban forms of consumption have brought about a symbolical reconfiguration of the figure of Cain, builder of cities, father of arts. In his 1991 novel titled Liverpool marée haute [Liverpool High Tide], the French writer Luc Lang followed in the footsteps of Michel Butor to depict the metamorphosis of the northern city.Footnote15 In Butor's text, the city remained at its core a space of production, where goods were made and traded. At the turn of the 1990s, manufacturing has disappeared from the city. It now specializes in cultural goods, and in particular art. In the novel it is the figure of Abel, the murdered brother in the biblical text, who seemingly leads the unfolding of the narrative. Abel Manson is the (fictitious) name of the director of the Walker Art Gallery, the Victorian museum of Liverpool which opened in 1877.Footnote16 Abel is in charge of the upcoming opening exhibition of the new Tate Gallery: a branch of the London museum, which (duly) opened at the Albert Docks by the Mersey in 1988 ().

Abel has a brother, an enigmatic figure named Jason, who returns from Africa to haunt the launch of the inaugural (fictitious) exhibition A Hundred Years of Africanism 1850–1950. The narrative opposes the pastoral mission of Abel who is involved in the reconversion of an industrial and colonial heritage (the Docks, which are tied to the city's ancient involvement in the triangular trade), and the destructive force of Cain, turned adventurer, who rejects the instrumentalization of life as an art exhibit. Jason's filiations to Cain are clear:

And when Abel asked too precise questions regarding the activities of his brother, he heard laudable whispers on Jason's persona, who was sometimes nicknamed the blacksmith, he who was Numu Bala in the cult of Souleymance, or he who had beside him the spirits of water and fire and who knew how to use them in accordance with Bobo Awa, the diva with golden teeth.Footnote17

Jason represents a rejection of the museification of the city. The point is made more blatant through the choice of the African-themed exhibit. For the new museum, the Tate in the North, will encage objects—masks, garments—whose life resides in their function and their agency into the world. In parallel, the rejection of a Western objectification mirrors a rejection of the deindustrialization processes, whereby contemplation and consumption take over action and production. The oppositional argument to a vision aiming to transform the former productive city into a branch of the service industry is phrased in the novel by the captain of the Liverpool harbor to the young Martin Finlay, Abel's assistant, who is looking for a rationale behind Abel's death, which occurs at the outset:

It is not battalions of soldiers that you train to colonize the earth, it is regiments of tourists. You turn the world into a stage set, a playground, a planetary cinemascope with museums here and there that proliferate like cancer.Footnote18

And this transformation of the tangible world, the real, into its representation, symbolized by the museum device, is ultimately the object of Cain's wrath: at the end of the novel, the new museum, the Tate in the North, goes up in flames.

The object of this repositioning of the figures of Cain and Abel and their respective symbolic functions echoes the historical development of the urban fabric and experience in the second half of the twentieth century. Michel de Certeau, among others, had pointed to this epochal shift from the predominance of the hand, that of the active maker, to that of the eye, of the passive beholder.Footnote19 The totalizing structures of industrial organization have been displaced by new urban functionalities and urban experiences characterized by tertiary activities and visual consumption. However, it is important to recognize in this shift the latent survival of fragmentary paleotechnic components, be they in the fabric of the city or in organizational or even social aspects of the new service industries' activities. The dialectic between production and contemplation, action and beholding, is in fact at play in the contemporary city at the turn of the twenty-first century—rather than a past condition. Past and present forms of industrial activity, for example, from steel to foam and from iron to liquid crystal, overlap each other. It is this interlocking of the material and the imagery, rather than the superseding of the latter over the former, that determines the present field of urban experience and intervention.

Fomenting Interstices in the Urban Fabric: From the Architect to the Artist

The opening words of Jane Jacobs's chapter “Visual Order: Its Limitations and Possibilities” in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) had seemed to caution the pretensions of the arts in matters pertaining to the design of urban environments:

When we deal with cities we are dealing with life as its most complex and intense. Because this is so, there is a basic esthetic limitation on what can be done with cities: A city cannot be a work of art Footnote20

However, it soon transpires that it is the architect's pretensions, which are condemned in this study. The issue lies in the modes of imposition of an order to the urban world:

To approach a city … as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art … .Footnote21

To counter this Promethean vision, it is recommended that “subsidiary irregularities” be nurtured “within a dominant grid system.” The grid system and its potent legacy are related to nineteenth-century industrialization: to the large cuts drawn into the city—Georges-Eugène Haussmann's Paris (1850–1870)—, to the urban expansion of Barcelona designed by Ildefons Cerdà i Sunyer (1860), and to the sprawl of the American megalopolis.Footnote22 Irregularities are the “organic” forms of cities that predate this modernization and large-scale urbanization. Jacobs's advice echoed the para-modern analysis of Camillo Sitte (1843–1903) in his influential 1889 book Der Städte-Bau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen [City Planning According to Artistic Principles].Footnote23 Sitte also reflected on the artistic nature of urban environments, where it could be found, and what its criteria might be. He opposed the all-encompassing deterministic modern trends of his contemporaries in the flexible usages of the past. The heart of the problem was not so much the possibility of envisaging the city as a work of art, but rather the rigidity inherent in modernist architecture:

Modern systems!—Yes, indeed! To approach everything in a strictly systematic manner and not to waver a hair's breadth from preconceived patterns, until genius has been strangled to death and joie de vivre stifled by the system—that is the sign of our time.Footnote24

To counter the rectangular logic of modernist architecture, Sitte turned to medieval and Baroque squares, in which irregularities brought variety and dynamism, as opposed to the sterile uninhabited stillness of their modern equivalents. Sitte underlined a significant reason for such a different outcome:

This is due to the fact that the irregularity of old planning is almost always of a kind that one notices only on paper, overlooking it in reality; and the reason for this is that old planning was not conceived on the drafting board, but instead developed gradually in natura.Footnote25

The immaterial conception of the urban space is opposed to a natural, historical, and organic antiurban development. A striking parallel in the critique of this process of retraction that severed the mind and the idea from the bodily and incarnated experience concerned the liveliness of art and its framing:

Works of art are straying increasingly from streets and plazas into the ‘art-cages' of the museum.Footnote26

This parallel brings together the city and the artwork in a confrontation with a mutual problem: the imposition of an artificial, overbearing, systematic ordering of their spatial identities. Is the only solution to prevent the sterilization of art-life the creative destruction symbolically represented by the burning of the museum in Luc Lang's Liverpool marée haute? Perhaps not, for the very irregularities note by Sitte in a myriad of examples, for instance the Piazza d'Erbe in Verona, or the Piazza Santa Maria Novella in Florence, offer an alternative strategy. This alternative suggests the use of Baroque diagonals to destabilize the alienating order of the modernist “right angle.”Footnote27 It suggests the use of parastrata, strata that are on the side, that generate interstrata and interstices, as an alternative to the all-encompassing geometric plan where no irregularity is meant to live on, where all should align to the righteous and monumental grid.

In the hybrid state of the twenty-first-century city, the cultivation of alternate strata in the urban condition must take into account the conservative precepts furthered by many incarnations of the twentieth- and twenty-first-centuries' industries. Lewis Mumford had already noted that, despite creating a number of positive apertures, many of the liberating qualities associated to what he termed the “neotechnic phase” (occurring between 1830 and 1900, and featuring inventions such as the electric cell, the moving picture, and the airplane) remained under the spell of the old “paleotechnic” orderFootnote28 (linked to the eighteenth century and to the exploitation of coal in particular):

The neotechnic refinement of the machine, without a coordinate development of higher social purposes, has only magnified the possibilities of depravity and barbarism.Footnote29

At the turn of twenty-first century, the scheme whereby the vicissitudes of the previous technological order envelop the hopes laid by the new advances is repeated. If the assembly line of machinery production had governed the Fordist-age, hypertrophied interaction subjected to criteria of economic efficiency could characterize the “post-industrial” age. In Sheffield in 2008, a potent reflection on performativity in our societies was proposed by the curator Jan Verwoert through the organization of a series of displays titled Yes, No & Other Options:

What would it mean to put up resistance against a social order in which performativity has become a growing demand, if not a norm? What would it mean to resist the need to perform? Is ‘resistance’ even a concept that would be useful to evoke in this context? After all the forms of resistance we know are in fact usually dramatic performances themselves. Maybe we should rather consider other, more subtle forms of not performing, of staging as the Slovakian conceptual artist Julius Koller called them ‘anti-happenings'. What silent but effective forms of unwillingness, noncompliance, uncooperativeness, reluctance or non-alignment do we find in contemporary culture when it comes to inventing ways to not perform how and when you are asked to perform?Footnote30

Artists participating in Yes, No & Other Options responded to this interrogation by devising actions that transgressed the performative demand. In this spirit, German artist Kirsten Pieroth contracted a bicycle messenger in Manchester, who was asked to bring a package to Sheffield, which implied crossing the Pennines, the mountains standing at the border of Lancashire and Yorkshire. The delivery consisted of a trophy to be handed to the messenger for completing the ride. Similarly, Paul Rooney's sound piece Words & Silence exemplarily explored the interstitial spaces in the context of a call center, an archetype of a flexible and alienating working environment: telephone centers can use devices that automatically prompt the dialing of a new number once the preceding one is over. The piece played on the role that answering machines can have in that time-controlled discursive assembly line. It is only in the blank space of the answering machine that the worker can have a break and step back from the continual performativity demanded of him. The interstitial unwritten tape becomes the locus of a liberating imaginary discourse. In accordance with the title of the project, Yes, No & Other Options, Verwoert pointed to a bypassing of a rigid binary system (horizontal–vertical) and the opening of layers of action in the unoccupied spaces of the worker's fabric.

With the advent of a postindustrial age, however, the remnants of the preceding production order did not disappear instantaneously. In former bastions of industrial production, mills, canals, and factories were left abandoned. With deindustrialization came opportunities for alternate occupation of these buildings: throughout the decade the number of artists' studio collectives multiplied in England, facilitated by access to cheap property. In Leeds, the organization East Street Arts, set up by Karen Watson and Jon Wakeman in 1993, pursued this aesthetic empowerment through the creation of a number of artist studios and a pragmatic negotiation with local authorities to construct viable models for artists to take over urban spaces ():

So we took a space, we were looking to find a mill with an empty top floor, and a landlord that wasn't that strict. We paid for enough space to have eight artists, and we organised it so they had studio spaces, communal spaces, kitchen facilities, that we could be warm … and then … we just kept taking more and more space, because people kept coming; in the end the had fifty spaces down there, and a big project space.Footnote31

But the reappropriation of urban textures by art should not occur in an idealized pristine aesthetic realm. Aesthetic, to be alive, has to engage directly with other types of activities in the city:

It wasn't just about bricks and mortar, about having a space, it wasn't just about programming and getting visible. If we were really going to make something last, we had to become part of the political fabric of the city, and then of the political fabric of the sector nationally.Footnote32

East Street Arts became engaged with the National Artist Association, with the local council in Leeds, and with the various cultural organizations and actors of the city. The aim was to secure the sustainability of the reclaimed strata in the urban fabric, on the basis of their aesthetic specificities. Interestingly, when the 2008 global economic crisis occurred, the opportunities that had been offered by the deindustrialized fabric were replicated through spaces of the new service economy being made available: former offices, bars, and restaurants that closed their doors and whose owners or the city were suddenly eager to find temporary occupants. East Street Arts could reenact their 1990s strategy in an even larger scale. As Karen Watson reflected:

We were very interested in invading everybody else . . . . We wanted artists everywhere, that's why we started looking for empty spaces again (in 2010). And that coincided with everything going a bit wonky with our economics and our banks. Landlords and estate agents started becoming more friendly with artists.Footnote33

The deindustrialization shifts in Britain in the second half of the twentieth century provided disused spaces for alternate aesthetic strategies to occupy; the 2008 recession suggested enlargement of these opportunities in the midst of the contemporary flexible service economy.

The two examples presented above embody two strategies of aesthetic production fomenting irregularities in the contemporary urban environment. On the one hand, we see subversion of the efficient performance model at the base of global urbanity—a model that can be read in the prolongation of German sociologist Max Weber's (1864–1920) account of the development of the capitalist model across the world through its origins in northern Europe Protestant ethics.Footnote34 On the other hand, we find a counter-narrative investment in a set of spatial layers which have been made available by the changing tectonics of economic orders, as well as their vicissitudes. Camillo Sitte's insistence on the benefits of natural or organic development in the city's aesthetic identity is there consciously enacted in opposition to the modernist ordering of space. The stress is placed on the notion of “lived space,” to use French Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre's (1901–1991) emphasis.Footnote35 Ultimately, one sees a conflict taking place in the city regarding two opposite forms of its own creative essence; two diverging modes of aesthetic being. First, one sees the attempt to create and shape the urban realm as a reflection of a superior intellectual design; this is the ground occupied by the heirs of the modern metropolis's architectural design, as well as the replication of global hotspots where the culture of display is paramount. Second, one sees the city's latent capacity to grow vital and viral variations from and within the grounds themselves; that is, the ground conquered by collective and individual spatial occupation: a space which is also a mental space, which enables one to think about the city diagonally.

Elizabethan Collars, or the Problem of Aesthetic Visibility in the Virtual Age

At the turn of the twenty-first century, this dialectical tension has been made more complex by the addition of a novel component to the city's texture. We have discussed the foundational industrial activity of the city; the paleotechnic moment in urban growth recalled its mythic birth: the crucial role of the artisan builder and craft of the blacksmith whose tools served to erect the urban fabric. We have evoked the twentieth-century historical evolution that transformed the ironmaker's world into a vibrant geometry of glass structures: the mirror-like reflections of the service industry, where the art of representation takes precedence over that of the forge and the steam engine. Accompanying these previous developments, however, an all-encompassing novel dimension made of virtual fluxes and virtual realities developed by computer-based technology arose. The new virtual spaces have been generated by radically new media, which Lev Manovich mapped through analyzing “web sites, virtual worlds,” such as multiplayer computer games, “ interactive installations, computer animation, digital video, cinema, and human-computer interfaces.”Footnote36 At the dawn of the twenty-first century, as Satomi Sugiyama and Jane Vincent suggested, the barriers between man and machine have become literally porous, with forms of information and communication technology (ICT) becoming ever more similar to humans, and humans turning more and more into ICT.Footnote37

Commentators have much reflected on the communication shift facilitating the constitution of an increasingly global world.Footnote38 As stated earlier in this text, Michel de Certeau in the 1970s had emphasized the growing role of the ocular in channeling our contemporary imaginaries. This preponderance of the eye, of seeing, was gained to the detriment of the hand, and of making. In chapter 2 of La culture au pluriel [Culture in the Plural] “The Imaginary of the City,” the search for happiness as meditated by a visual matrix opposed action to a decadent contemplation:

The development of the imaginary is the converse of a “civilization” in which visionaries and contemplative souls proliferate. Thus “current events,” this visual remainder of action, display the good and bad fortunes of others according to a law that combines the luxury of information with the passivity of its witnesses. Inaction seems to be the price of the image. Amorous pursuits, the bedazzlement of addicts, athletic exploits, or programs of social renewal pour into imaginary literature and offer, along with the spectacles themselves, an alibi of action.Footnote39

There appeared to be a disempowering impact brought about by the multiplication of images in our societies: visual consumption as formatting our imaginaries and sterilizing physical engagement. However, from the emission of instantaneous coding information to the all-over intrusion of the World Wide Web, the proliferation of visual signs has become entangled with myriads of tactile and mental digital-based interactions.

Virtual layers have reinforced the displacement of the self in an increasingly trans-industrial environment, where immaterial presences are juxtaposed with the concreteness of past and present constructions. Massimo di Felice in his consideration of “post-urban landscapes” notes that with the advent of electronic forms of living, the subject–object relationship (the human–nature split), has been replaced by a much more complex and interactive network that he defines as “subject-media-circuit-nature.”Footnote40 In the “electronic metropolis,” social relations are no longer solely affected by the continuous stimuli described by Georg Simmel's sociological foray into mental life in the modern metropolis,Footnote41 but, according to di Felice, take place within a collapse of former spatial structures:

The forms of habitat and the social relationships that develop in the electronic-metropolis are characterized by continuous mutations and a perpetual becoming. The absence of precise limit and the consequent loss of meaning of terms such as “within the walls,” “out of walls,” “native,” “foreign,” “center,” “periphery,” position its inhabitants in a post-identity condition and constrain them though their meta-geographical delocalization to non-linear processes that transform bodies and sites in information exchange circuits.Footnote42

Within this intricate merging of bodies and fluxes, reality has become an elusive entity. Decentralization and the superposition of physical with immaterial experiences characterize the postindustrial condition. In the face of such drastic social and cognitive shifts, Paolo Perulli in Vision di città [Vision of the City] underlined the necessity of analyses and to rethink the understanding of our urban environment:

The city represents a frame of an essentially cognitive type for a-territorial fluxes: it provides surfaces of reference and interpretation to actors who are multiple and delocalized, dispersed, and fragmented … . Today, we as well must redo the frame analysis of the city.Footnote43

There is a descriptive, analytical, and philosophical reflection to be carried out with respect to the intrusion of multiplicity, fragmentation, and the decentering of urban loci through virtual, digital, and spectral stratifications. But going back to the city of Cain, these transformations pose a particular problem to aesthetic thought, and to its trademark working of epochal imaginaries. This problem is not so unlike the theoretical issue posed to contemporary art as underlined by Jean-Claude Moineau in his L'art dans l'indifférence de l'art [Art in the Indifference of Art]: the multiplication of artistic forms has induced a neutralization of art's effectiveness. To overcome this nullification, it is only through stepping out of its own category, “art,” that art could find a guarantee of its very existence.Footnote44 Overall, the post-urban city and condition has drastically intensified the visual competition and thereby threatened the capacity of art to influence our imaginaries.

To discuss the articulation of this aesthetic problem, I now turn to a video work Inside His Master's Voice, by the Derry-based artist Conor McFeely ().Footnote45 This work furthered a reflection on perception that is both ancient and attuned to the virtual queries of the present. Its constitutive components as well as its fragmented narrative symbolically address the aesthetic problem suggested above.

Figure 4 Installation view of Conor McFeely's Inside His Master's Voice at Ormeau Bath Gallery, Belfast (2010). Image © and courtesy of Conor McFeely.

In the opening seconds, there is darkness; and out of the darkness emerges a moving pattern of silvering electronic waves that eventually crystallizes into a winter landscape. Then sound appears, a slow electronic fuzz, and into the darkness light, words in Japanese. And suddenly, accompanied by a confession in English “two people laughed, two people cried, most people were silent,” a fragment of a man's face is seen rotating within an Elizabethan collar ().

Figure 5 Conor McFeely, Inside His Master's Voice (detail) at Ormeau Bath Gallery, Belfast (2010). Image © and courtesy of Conor McFeely.

The Japanese voices are extracted from the life simulation computer game the Simms, for which a nonsense language was created. The English voice is that of J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967), who was one of the physicists working on the first American project to develop nuclear weapons in the 1940s. Both refer to the creation and destruction of worlds.Footnote46 The collar similarly alludes to the existence and mutability of parallel worlds. It is large and whitish, reaching far up around the man's head. It is seen in alternate takes with the light bulb going on and off. “And to impress him, takes mostly armed form, and says, now I am the coming death, the destroyer of worlds.” Horses in a snowy field, the lingering bit, and the sound of a lighter repeatedly stroke, and then the man in the collar again. The Elizabethan collar is the channel of the master's voice. It also prevents one, irresistibly drawn towards the itching parts, from hurting oneself. Concurrently, it necessarily segments one's vision. This rotating, fragmented collar is the present materialization of the former Renaissance viewing point. It is Leon Battista Alberti's (1404–1472) window opened onto the world, adapted and updated to the present human condition. The slices of the world seen are moveable, repetitive, and partial, and it is within this self-effacing surface that the artist has to position the work:

What we see subjectively and objectively is an ongoing concern. At that level, all communication is fragmented. We are sort of unreachable and reachable at the same time.Footnote47

The gap between the artist's intention and the viewer's perception is heightened by the multiplying screens, which surround our vision. In this context, where the immaterial displacing created by a-territorial fluxus surmounts the physical positioning, it is a challenge for the artwork to find the site from which to reconfigure the “real.” If Conor McFeely acknowledges that “we occupy some common ground,” it is a ground that is moving and saturated, where chariots are suddenly displaced in uncertain warehouses, where visibility as well as focus are turned in and out in a world dangerously perceived as internalized.

This segmentation, however, does not prevent some form of exchange. It might be seen as akin to Gottfried Leibniz's (1646–1716) monade, this “autonomy of the interior,” this “interior without exterior,” as discussed by Gilles Deleuze in his 1988 reflection on the fold.Footnote48 In particular, to go back to the specific issue of urban perception, Deleuze uses an urban metaphor to describe the mode through which each monade as an individual unit comprehends the totality of the series:

What is grasped from a viewing point, is not a specific street nor its definable relation with other streets, who are constants, but the variety of all possible connections in the route leading from one street to another: the city as an labyrinth susceptible of order.Footnote49

McFeely's Elizabethan collar, standing as a representative and metonymical component of his work, embodies the individual perspective that sheds light on a particular local region, while being folded within the textures of the whole. In the exhibition and installation Weathermen (), developed by McFeely from 2011 to 2013, the visitor who stepped into the gallery space in the Lugano version, in Ticino (2013), first encountered on a video screen a perfectly spherical shape animated by a tumult of foaming textures.Footnote50

Figure 6 Conor McFeely, Weathermen, at Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast (2013). Image © and courtesy of Conor McFeely.

After some inspection, the viewer might notice the silhouettes of two impenetrable figures hovering over the edge of the circle, as if directly influencing the movements underneath. It appears that the luxuriously contrasted events of the world are mirrored onto the top of a glass. It is perhaps one world within many others, but its very specificity is brought onto us in accordance to the transversal contemporary nature of our imaginaries: both partial and all encompassing.

Conclusion

In the evocation of the current parameters informing the faculties of aesthetic imagination in an ever more all-encompassing urban environment at the turn of the third millennium, I have moved through three constitutional and correlated components. First, the industrial foundations and industrial heritage. This heritage has been addressed in both its recent historical layer associated with the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution in Britain, and its “mythological” origins in the biblical figure of Cain, presiding over the burgeoning of cities and arts. Inspired by Luc Lang's literary reflection on an aesthetic phenomenon characteristic of British urban transformations explored as an archetype of a globally connected urban entity, this joint discussion over the city as forge led to a subsequent dilemma, when in the late twentieth century the aesthetic production of the urban is seen as framed or even imprisoned by the very urban fabric: the city becomes a museum. When the city becomes a sub-branch of the tourism industry, the risk might be that the arts are in a sense no longer agents, but prepackaged goods ready to be consumed; in other words, that they potentially become staged, mirrors of a reality they are no longer connected to, dependent upon factors extrinsic to their own selves, exhibits rather than tools.

At this point, the trans-industrial characteristics of our contemporary cities has been introduced: present urban entities are made of both past industrial paleotechnic textures, some still active as such, some transformed in other functional capacities, and newly devised economic and cultural layers, linked in particular to the broad sector of the service industries. In this context and stemming from the active–passive dichotomy regarding the role played by the arts, is introduced a second issue pertaining to the authentic or artificial character of the urban realm. The art historian Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945) famously stressed the crucial necessity for his discipline's practitioners to link the cell of the scholar to the mason's yard; in other words, the conceptualization or intellectualization of the world to its very fabric. With Jacobs and Sitte, the question regarding the artistic character of the city was asked anew in relation to modernity and modernism. It is the distance that separates the urban planner and the architect from lived space that was identified as the stilling axis. Following Sitte, a “living aesthetic” could be found in the irregularities and interstices of the urban as explored and constructed by artistic strategies taking advantage of both past and present industrial spaces abandoned by economic patterns and fluctuating economics. This “living aesthetic” was exemplified by the historical development in the 1990s and 2000s of the Leeds collective East Street Arts, as well as in the works and problematic deployed around the idea of performativity in the age of the service and knowledge industries by the Sheffield 2008 exhibition Yes, No & Other Options.

Finally, a crucial layer was added to the discussion of the aesthetic presence in the urban framework: the impact of virtual evolutions. In the past twenty years or so, we have witnessed a de-incarnation of the urban experience, to the extent that it might not even be viable to digress on the previously physically contained urban field. But here, more specifically, we have been interested in how the advent of digital, virtual, and immaterial communications created not solely a new realm to be explored by artistic practices, but also a ferocious competitor to the traditional functions and skills of the artist regarding the representation of the world. To a virtual world must correspond an aesthetic positioning that is aware and responds to the contemporary neutralization of optical aesthetics. To circumnavigate this actualized aesthetic problem, we followed the lead of Conor McFeely and in particular his both sculptural and digital Elizabethan collar. What can be seen—and how to be seen in aesthetic terms and thought—in the electronic and digital age? This remains an open question, though we may note that a) our trans-industrial perspective puts the emphasis on the superposition of material and virtual urban fabric, rather than a complete transformation and b) the initial reflection pertaining to the transformation of the city as production to consumption site can be transferred to that of the material–immaterial surfaces. And it is, perhaps, in the irregular and interstitial strategies discussed in the second part that the urban imaginary can be aesthetically built up in the present, provided it takes into account the recent metamorphosis of the figure of Cain, who now combines the skills of Hephaistos with that of the ever more magical Hermes.

Additional information

GABRIEL GEE is Assistant Professor of Art History at Franklin University Switzerland, in Lugano. His research interests include British art in the twentieth century, forms and discourses in the visual arts in Northern Ireland in the late twentieth century, the interaction between aesthetics and industry in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the iconology of twentieth-century globalized societies. He is a co-founder of the research group Textures and Experiences of Trans-industriality (TETI group).

Notes

1 Francis D. Klingender, Art and the Industrial Revolution (St Albans: Paladin, 1972), 3.

2 Guy McDonald, England (London: Cadogan Guides, 2003), 540.

3 Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844 (S. Sonnenschein, 1892), 277–78. This sentiment is reported by Engels in the second paragraph of his final chapter titled “The Attitude of the Bourgeoisie towards the Proletariat.”

4 Michel Butor, L'Emploi du temps (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1956). I am using the Jean Stewart translation: Passing Time (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960), 36.

5 Butor, Passing Time, 73.

6 Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 151–211.

7 A. W. N. Pugin, Contrasts—Or, a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries and Similar Buildings of the Present Day Shewing the Present Decay of taste Accompanied by Appropriate Text (London: James Moyes, 1836), 30.

8 The contrasted bird's-eye view is itself rather a rare occurrence. The plates show mostly building facades and interiors.

9 Pugin firmly launched the Gothic revival through the publication of The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture in 1841.

10 Rosemary Hill, “Reformation to Millennium: Pugin's Contrasts in the History of English Thought,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 58, no. 1 (March 1999): 26–41. Pugin himself converted to Catholicism. He was immersed in an intellectual milieu which believed in the golden age of the pre-Reformation period.

11 David Harvey, The Conditions of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (London: Basil Blackwell, 1989).

12 John Davies and Rob Powell, In the Wake of King Cotton (Rochdale: Rochdale Art Gallery, 1986).

13 Beside Harvey, The Conditions of Postmodernity, see his political pendant: Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-industrial Society (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

14 Steven Miles and Malcolm Miles, Consuming Cities (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

15 Luc Lang, Liverpool marée haute (Paris: Gallimard, 1991).

16 Edward Morris and Timothy Stevens, The Walker Art Gallery, 1873–2000 (Bristol, Samson & Co., 2013), 40.

17 Lang, Liverpool marée haute, 243–44. “Et quand Abel posait des questions trop précises sur les activités de son frère, il entendait des murmures d'estime sur la personne de Jason qu'on surnommait parfois le forgeron, celui qui était Numu Bala dans le culte de Souleymance, ou celui qui avait pour lui les génies de l'eau et du feu et qui savait s'en servir selon Bobo Awa, la diva aux dents d'or.” Unless otherwise noted, all translations in the text are mine.

18 Lang, Liverpool marée haute, 260. “Ce ne sont pas des bataillons de soldats que vous formez pour coloniser la planète, ce sont des régiments de touristes, vous faites du monde un décor, une aire de loisir, un cinémascope planétaire avec ici et là des musées qui prolifèrent comme un cancer.”

19 Michel de Certeau, La Culture au Pluriel (Union générale d’éditions, 1974), 33–36.

20 Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961), 372.

21 Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 373.

22 Marcel Roncayolo, La Ville et ses territoires (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), 101–04.

23 Camillo Sitte, Der Städte-Bau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen: Ein Beitrag zur Lösung modernster Fragen der Architektur und monumentalen Plastik unter besonderer Beziehung auf Wien (Vienna: C. Graeser, 1889); translated into French as L'art de bâtir les villes: notes et réflexions d'un architecte, trans. Camille Martin (Paris, H. Laurens, 1890), available online at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k744025/f1.image. The text translations used are from City Planning According to Artistic Principles, trans. George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins (New York, Random House, 1965).

24 Sitte, City Planning, 91.

25 Sitte, City Planning, 49–50.

26 Sitte, City Planning, 105.

27 On this topic of the diagonal and the Baroque, one thinks of Heinrich Wolfflin's Principles of Art History (New York: Dover, 1932) and to the reflections on the fold of Gilles Deleuze, in Le pli. Leibniz et le Baroque (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1988).

28 Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1934), 214.

29 Mumford, Technics and Civilization, 266.

30 http://www.artsheffield.org/as08/context.html, accessed February 1, 2014.

31 Karen Watson in conversation with the author, June 10, 2008.

32 Karen Watson in conversation with the author, June 10, 2008.

33 Karen Watson in conversation with the author, June 2012.

34 Max Weber, L’éthique Protestante et l'esprit du Capitalisme (1904; Paris: Plon, 1964).

35 Henri Lefebvre, La Production de l'espace (Paris: Anthropos, 1974).

36 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 8–9.

37 Satomi Sugiyama and Jane Vincent, “Social Robots and Emotion: Transcending the Boundary Between Humans and ICTs,” Intervalla 1 (2013): 1–6.

38 See, in particular, Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity, and Bell, The Coming of Post-industrial Society.

39 Michel de Certeau, Culture in the Plural, trans. by Tom Conley (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 18.

40 Massimo di Felice, Paesaggi post-urbani: la fine dell'esperienza urbana e le forme comunicative dell'abitare (Milan: Bevivino, 2010), 175.

41 David Frisby and Mike Featherstone, Simmel on Culture (London: Sage, 1997). Simmel “The Metropolis and Mental Life” [Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben] was published in 1903.

42 Di Felice, Paesaggi post-urbani, 175: “Le forme dell'abitare e le relazioni sociali che si sviluppano nelle metropoli-elettroniche sono caratterizzate da continue mutazioni e da un continuo divenire. L'assenza di un limite preciso e la conseguente perdita di significato di termini quali: ‘entro le mura,’ ‘fuori le mura,’ ‘nativo,’ ‘'straniero ,’ ‘centro,’ ‘periferia,’ pongono i suoi abitanti in una condizione post-identitaria e gli impongono, nelle loro dislocazioni meta geografiche, un ‘procedere non lineare’ che trasforma corpi e luoghi in circuiti di scambio di informazioni.”

43 Paolo Perulli, Vision di città (Torino: Einaudi 2009), 58: “La città rappresenta così un frame, una cornice di tipo essenzialmente cognitivo per flussi che sono propriamente a-territoriali: fornisce quadri di riferimento e di interpretazione ad attori multipli e delocalizzati, dispersi e framentati. Lo avevano detto Simmel e Goffman nell'epoca della metropoli. Oggi dobbiamo anche noi rifare frame analysis della città. Forse è questa la sua essenziale funzione da riscoprire, nell'epoca delle imprese globali e delle città-regione globali.”

44 Jean-Claude Moineau, L'art dans l'indifférence de l'art (Paris: PPT, 2001).

45 www.mentalimage.org.uk, accessed February 1, 2014.

46 Conor McFeely in correspondence with the author, 2014.

47 Conor Mc Feely in conversation with the author, 2011.

48 Deleuze, Le pli, 39.

49 Deleuze, Le pli, 34. “Ce qui est saisi d'un point de vue, ce n'est donc ni une rue déterminée ni son rapport déterminable avec les autres rues, qui sont des constantes, mais la variété de toutes les connexions possibles entre parcours d'une rue quelconque à une autre: la ville en tant que labyrinthe ordonnable.”

50 Conor McFeely, Weathermen, exhibition at Franklin College Switzerland, Sorengo, Ticino, February 21, 2013, to March 7, 2013. Weathermen was subsequently shown at The Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast, Ireland.