Abstract

This special issue of Visual Resources brings together studies of some of the principal journals and themes related to the history of the international art press in the twentieth century. Journals have played a crucial role in the art world and in the study of art history: often the site of new scholarship or interpretation, they also illuminate the role of the art critic and art criticism and the relationship of these to artistic practice. Moreover, periodicals often reveal the complexities of the wider art world, including the art market and art funding; they can also be examined as works of art in their own right. This special issue explores these and other themes, demonstrating the rich diversity embedded in this nascent field of scholarly research and underscoring the significance of journals within the sphere of art publishing. The collection focuses on the twentieth century, which witnessed the emergence of the modern specialist art magazine. It concludes before the digital revolution in publishing in the early twenty-first century, which has already prompted dramatic changes in the periodicals landscape. Through case studies drawn from across Europe and the United States, this special issue aims to present a significant contribution to a growing body of research and literature within the discipline of art history.

The Art Press: Inception and Scope of This Project

This special issue of Visual Resources is focused on investigations of the art press, a theme particularly germane to this journal. This was a main research interest of its former editor Helene E. Roberts, a true pioneer in the study of art journals.Footnote1 Visual Resources has then continued to publish significant essays on the art press under the editorship of Christine L. Sundt. Notably, the art press and photography were featured in the special 2010 issue of Visual Resources, “‘Second Hand Images’: On Art's Surrogate Means and Media,” edited by Julie Codell and dedicated to Roberts.Footnote2 Whereas the bulk of literature on periodicals targets the nineteenth century or early modernism, the art press in the twentieth century is a less explored subject. This special issue wishes to recognize the specificity of this period as a timeframe in which sweeping changes have happened both in art history as well as in the art press. The methodology of art historical investigation has widened considerably and the art press has been rapidly transformed by technology—for instance, digital media has modified not only the way we deliver content, but also how the content is studied.Footnote3

The selection in the special issue grew out of a conference on art periodicals of the twentieth century, organized in London by Sotheby's Institute of Art and The Burlington Magazine in 2013, in which the contributions by Meaghan Clarke, Poppy Sfakianaki, and Dorothea Schöne were presented as papers. The essays by Giovanni Gasbarri and Samuel Shaw were presented as papers at the Art Historiography Seminar at the Warburg Institute (London) in 2012–2013, while those by Róisín Kennedy, Matthew Bowman, and Stephen Moonie were specially commissioned. The essays investigate a group of North American and European publications which include The Studio, The Burlington Magazine, and The Connoisseur from Britain; L'Arte from Italy; Cahiers d'Art from France; and from the United States Artforum, Art News, October, and the art pages of The New York Times. Even such a relatively small selection testifies powerfully to the importance of the periodical press. If their geographical scope is comparatively narrow, their interests are transnational and the range of magazines examined is broad. Some were relatively long-lived, others survived briefly; some were open-ended in scope and/or methodology, others more focused or with a specific agenda. This diversity is also reflected in the variety of individuals writing for those art periodicals: journalists, critics, dealers, museum professionals, art historians, and artists themselves.

The Art Press Today: Study and Development

The study of the art press is a relatively new yet fast-developing area of inquiry. It has developed within art libraries and bibliographical studies, investigations on art historiography and parallel with the growth of social histories of art. In 1968, the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals was founded in the United States. Its journal, Victorian Periodicals Newsletter, was an early platform for discussion, which, although confined to the nineteenth century and English-language publications, produced (and in its most recent form Victorian Periodicals Review produces) much important work.Footnote4 The 1976 exhibition The Art Press at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, site of the (British) National Art Library, represented a wider chronological and geographical attempt to consider the art periodical as a genre. Its supporting publication, edited by Clive Phillpot and Trevor Fawcett, gave a broad overview of the historic development of the art press from the eighteenth to the mid-twentieth century.Footnote5 More recently, scholars, including Julie Codell, Meaghan Clarke, Anne Helmreich, and Ysanne Holt, have produced exemplary case studies, some of which have been published in this journal.Footnote6 The newly published The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines is also an important and comprehensive survey, which focuses mainly on “Little Magazines.”Footnote7 In the rest of Europe, the works by Gianni Carlo Sciolla and others in Italy and Maria Rennhofer in Germany deserve mention.Footnote8 These publications demonstrate the potential of periodicals, often used merely as supporting sources, as worthy objects of analysis in their own right. Periodicals are significant for the study of art criticism, art historiography, and the social history of art alike. They allow us to trace new developments in art writing, establishing and circulating ideas that may later be expanded in books. They are also an essential tool for investigating social mechanisms, such as the changing role of art criticism, as well as scholarship and the relationship with and between artistic practice and the art market.

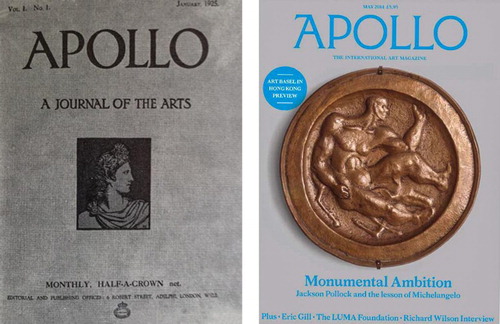

This is a timely period for a reflection on periodicals because in recent years, the vicissitudes of the global economy, developments in the methodology of art history, and innovations in technology have all brought forward significant changes in the art press. Two worldwide economic recessions in the early 1990s and 2010s have resulted in a significant reduction in public funding for the arts and have diminished the assets of private institutions that traditionally sponsor cultural projects. Because of the necessity to operate as a commercially viable enterprise, some leading journals, such as Apollo (since 1925) (), have shifted their focus from scholarly to that of general public interest, while others, such as the Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1859–2002), have closed down altogether. New digital platforms and online publication through the World Wide Web have also threatened the predominance that paper has had for five centuries and have brought about changes in format. Some journals have migrated from print to online publication only, whereas others, such as The Journal of Art Historiography (2009–) and Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide (2002–), have been established from the outset as online, free-access publications only. Yet, digital technology has also contributed to a renaissance in the study of journals. More and more publications are accessible online, on JSTOR, or in repositories, such as archive.org or the Modernist Journals Project.Footnote9 New Internet-based indexing projects also make a large volume of text available and easier to search, so that the research possibilities of periodicals can be explored and exploited in full, and new digital visualization software promises to be an effective tool in the analysis of such large data.Footnote10 More changes have been brought up by a methodological shift in academic art history, from an essentially object-based study to a broader investigation of network. From the mid-1970s, concerns with circulation, consumption, and a socio-economic reading of the works of art have privileged (at least for a time) vis-á-vis questions of authorship and authenticity. This change in focus of the discipline has contributed to the demise of some publications, as in the case of The Connoisseur (1901–1992).Footnote11 This, however, has also elicited the foundation of other periodicals, such as Art History, a journal that began in 1978 as the voice of radical art history and conflicted with the connoisseurial bias of much of the art press at the time.Footnote12 Moreover, the investigation of network-enabled scholarship, as we shall see, is proving to be a particularly fruitful methodology to apply to the study of the art press.

The Art Press: Critical Questions

Perhaps the most important critical question that the essays in this special issue aim to address is: what is the position of periodicals within the larger panorama of art history and art historiography? The answer they provide is complex. Art history is a discipline in fieri, still in search of a definition, and an investigation into the art press reveals the inception of this disorientation as well as a developing quest for terminology and clarification. For instance, there still exists an abiding and deep-seated tension between definitions of “art criticism” and “art history,” as is evident by the prevalence of the recent term, “art writing.” Stephen Moonie's essay on Artforum argues that this condition, latent since the hybrid professional panorama of the nineteenth century, was exacerbated by this publication's emergence in the 1970s. Yet periodicals are not merely historical testimonies and passive commentators; they actively construct a critical situation, as Matthew Bowman argues when exploring October’s postmodernism. Journals construct criticism even under the guise of reportage and by creating dialectic of reception and production are crucial contributors to art historiography. They are platforms for immediate trends and can be instrumental in the inception of what subsequently becomes established academic thought. This is evident, for instance, in the case analyzed by Giovanni Gasbarri, demonstrating how periodicals contributed to the critical rediscovery of Byzantine art in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century. And yet there is more to be said as periodicals fulfilled a somehow ambivalent role. Journals not only contributed significantly to the development of a language that has become the dominant discourse in the discipline, and ultimately enforce the process of canonization of what is considered “important” or “worth studying” throughout history, but they are also fundamental to our understanding of art history as a collective research enterprise, composed by different contributors, and where voices at the periphery and outside the establishment also find their expression. In the special issue, several essays address these factors. For instance, Dorothea Schöne's contribution exemplifies the importance of including non-canonical sources in the study of the art press because it was a popular newspaper, The New York Times, rather than a specialized publication, which disseminated and influenced the post-1945 perception of German art in the United States. A reflection on gender is also pertinent as women's contributions in art journals have often been central to their constitution but peripheral in their later historiography. Meaghan Clarke's essay reveals the many women who contributed to early histories of collecting and connoisseurship in early modern journals such as The Studio, The Connoisseur, and The Burlington Magazine; whereas Róisín Kennedy explores the role of the almost forgotten curator and writer Ellen Duncan (1850–1937), a crucial figure in the organization of the postimpressionist exhibitions in Dublin.

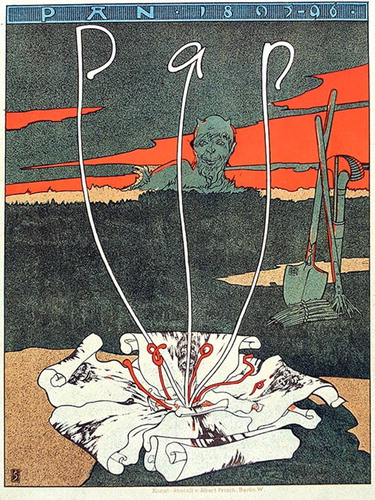

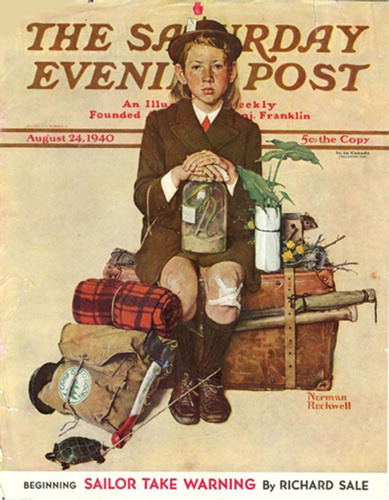

The study of journals also raises awareness of the weaknesses implicit in usual disciplinary boundaries. For instance, the connection between art writing and artistic practice in the periodical press has so far been one of its less-explored aspects, possibly because of the development of art history as an academic discipline and its subsequent departmental divisions in modern universities. This vital connection between criticism and practice is reestablished by Samuel Shaw who examines the role of the artist as art writer and investigates the critical output in periodicals of Charles John Holmes (1868–1936) and William Rothenstein (1872–1945) in relation to their art. The intersection between art and art writing is not just an early twentieth-century phenomenon. Stephen Moonie here examines how the critical development in Artforum was fostered by a dialogue between critics and artists, citing the example of Frank Stella's (b. 1936) paintings which took their cue from Clement Greenberg's (1909–1994) criticism. Journals, however, sometimes cross the disciplinary boundaries between art writing and art practice, by being, on the one hand, the carriers of writing on art and, on the other, being art object themselves. For instance, in the earlier years of the century, some periodicals such as The Art Journal (1839–1912), published in London, were vehicles for art reproductions, eagerly collected and exchanged as works of art themselves; and publications like PAN magazine (1895–1900 and 1910–1915), were more akin to an objet d'art than magazine (). More recently, Carl Andre's (b. 1935) “critique of criticism,” published in Art Monthly (since 1976), was constructed, like his sculpture, as a grid.Footnote13 Covers of magazines are an art form in their own right, as exemplified by Byam Shaw's (1872–1919) early covers of The Connoisseur or Norman Rockwell's (1894–1978) for The Saturday Evening Post ().Footnote14

Figure 2 Joseph Sattler (1867–1931), cover of PAN, 1895-1896. Color lithograph, 25.7 × 33.2 cm. London, Victoria and Albert Museum (Inv. no. E.3099-1938).

Figure 3 Norman Rockwell, cover for The Saturday Evening Post, August 24, 1940. Color lithograph, 27 × 35 cm.

Journals also offer fruitful material for political and socio-economical investigations, such as questions of nationalism and funding. In fact, investigations on “foreign” forms of art develop into and from a heightened awareness in national practices, just like studies of the past are stimulated by contemporary concerns. Giovanni Gasbarri investigates how the Italian art press was a crucial part in the debate on how Byzantine, and therefore “Greek” and “foreign,” elements contributed to the origin of Italian art at a time when a recently united Italy (1861) was striving for a cohesive national identity. Róisín Kennedy analyses how in Ireland in the mid-1910s the overturning of traditional ideas found in postimpressionism was for some a radical model for the invention of a New Ireland. The connection of the art press with the art market is another crucial matter, already identified by Harrison C. and Cynthia White in their influential study on the nineteenth century critic-dealer system and later expanded by other scholars.Footnote15 Poppy Sfakianaki, in her analysis of the interviews with art dealers by Teriáde (Efstratios Eleftheriadis, 1897–1983) and Christian Zervos (1889–1970) in Cahiers d'Art in the mid-1920s, demonstrates how much the reputation of artists depended on being at the center of a network of critics and dealers, and how the latter contributed toward the construction, legitimization, and promotion of the values of modernism. The relationship between journals and museums is equally close. Not only were many art writers museum professionals, but their commentary on public collections and their exhibitions was also a principal topic of journals, which often had a rather transparent agenda to influence museums’ choices. For instance, Helen Rees Leahy has demonstrated elsewhere how in its early years The Burlington Magazine strove to influence the acquisition policy of London's National Gallery and wished to support a new class of professional expert to manage the national collections.Footnote16

Conclusions

As early as 1976, Trevor Fawcett and Clive Phillpot had invited scholars to exploit the research potential of periodicals, but it was only in 2001 that Julie F. Codell, in her often cited essay “When Art Historians Use Periodicals; Methodology and Meaning,” questioned the use of periodicals merely as sources and argued that the art press created a network of allegiances, cultural interests, and a political economy of art that deserved to be critiqued as such.Footnote17 The studies gathered in this issue of Visual Resources do so: they re-create the circles of artists and writers, their institutional and commercial connections that gravitated to significant art journals of the twentieth century. In doing thus, they recognize the character of the art press as a social, an intellectual, and an economic activity within which writers and artists shared expertise and contacts. Ultimately, all essays in this issue are concerned with art and art writing as a social practice and can be described as case studies of networks. Such studies not only illuminate the connections between the periodicals examined, but they also explain how social networks had a direct bearing on the type of art writing adopted by each publication and how they contributed to the forming of a specific aesthetic and art historical language. This complements recent work in aesthetics, which now seeks to historicize aesthetic values, and therefore interprets art writing as texts originating from a specific and shifting history rather than from an abstract philosophy unbounded by constraints of time or context.Footnote18

Even through the analysis of single case studies of this current issue, a narrative of growing self-awareness and increased specialism emerges in the course of the century, from the still fluid boundaries of competences in the art world investigated by Clarke to the highly complex professional situation examined by Bowman. The discipline of art history is still in a state of flux, and it is difficult to predict what changes its development will bring for the periodical press. For instance, a return to an interest in connoisseurship, where the establishing of authorship and authenticity is seen again as a core responsibility of art history, is also causing concomitant concerns about the abandonment of paper as preferred format for publication, since this is still the medium in which art works are more faithfully reproduced. Moreover, as questions of permanence and sustainability of online-only projects are raised, paper offers a more stable publishing platform than digital. As the twenty-first century unfolds with new challenges for the art press, it is timely to reflect on the specific challenges and accomplishments of the previous century. This issue of Visual Resources not only wishes to raise questions in order to stimulate further contributions but also, by expanding on the work of its precursors, aims to provide some answers.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Dylan Armbrust, Olivia Parker, and Claire Sapsford at The Burlington Magazine who have facilitated and encouraged this project since its inception. At Sotheby's Institute of Art, thanks are due to Jos Hackford-Jones, Megan Aldrich, and Jonathan Woolfson. I wish to thank also Scott Howie for his support, insights, and patience throughout the project. I am especially indebted to my conference co-organizers—Anne Blood, then at The Burlington Magazine, and Lis Darby from Sotheby's Institute of Art—who have shared very generously with me their time and their thoughts. This special issue truly would not have happened without their initial contribution.

This is the last issue of VR edited by Christine L. Sundt before her retirement. I have had the pleasure and privilege to work with Sundt both as an author and guest editor and I was unfailingly impressed by her clarity of thought and accuracy. I wish to dedicate this special issue to her, in recognition of all her work to further the study of the art press.

Additional information

BARBARA PEZZINI is a London-based art historian, curator, and writer. As Index Editor of The Burlington Magazine she edits the digital archive of this journal, and writes and researches on all matters related to the art press, with a wider interest in the interaction between art criticism and the art market and a particular focus on the early history of The Burlington Magazine. Pezzini has contributed to scholarly periodicals, such as The British Art Journal, Visual Resources, Art Libraries Journal, Romney Society Transactions, and The Burlington Magazine. Her current digital project, for which she is the recipient of a Monument Trust Grant, is the digitization and catalog of historical art dealers’ advertisements in The Burlington Magazine from 1903 to the present. Since October 2014, Pezzini is the recipient of an Arts & Humanities Research Council's Collaborative Doctoral Award between The National Gallery (London) and the University of Manchester to research the relationship between the museum and the London art dealer Agnew's.

Notes

1 For instance, very recently, Chara Kolokytha, “The Art Press and Visual Culture in Paris during the Great Depression: Cahiers d'Art, Minotaure, and Verve,” Visual Resources 29 (September 2013): 184–215, and Barbara Pezzini, “The Burlington Magazine, The Burlington Gazette, and The Connoisseur: The Art Periodical and the Market for Old Master Paintings in Edwardian London,” Visual Resources 29 (September 2013): 154–83.

2 Notably by Helene E. Roberts, American Art Periodicals of the Nineteenth Century, ACRL Microcard Series, No. 141 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1962); “British Art Periodicals of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Victorian Periodicals Review 9 (July 1970): 1–183; “Exhibition and Review: The Periodical Press and Victorian Exhibition System,” in The Victorian Periodical Press: Samplings and Soundings, ed. Joanne Shattock and Michael Wolf (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1982), 79–107; “The European Magazine,” in British Literary Magazines, The Augustan Age and the Age of Johnson, 1698–1788, ed. Alvin Sullivan (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983), 106–12; “Periodicals, III:5(vi); Great Britain,” in The Dictionary of Art, ed. Jane Shoaf Turner (London: Macmillan Publishers, Ltd., 1996), vol. 24, 445–47. Also, “A Tribute to Helene E. Roberts ‘Second Hand Images': On Art's Surrogate Means and Media—Part I: The Art Press and Photography,” ed. Julie F. Codell, special issue, Visual Resources 26 (September 2010): 211–330.

3 The changes in art history brought forward by digital technologies and applications were discussed in a recent special issue of this journal: “Digital Art History,” ed. Murtha Baca, Anne Helmreich, and Nuria Rodríguez Ortega, Visual Resources 29 (March–June 2013): 1–146.

4 Notably the writing by Helene E. Roberts, but also, more recently, Julie Codell, ed., “The 19th-century Press in India,” special issue, Victorian Periodicals Review 37 (Summer 2004); Rosemary Van Arsdel, ed., “Australian, New Zealand, and South African Periodicals,” special issue, Victorian Periodicals Review 37 (Winter 2004); Teresa Mangum, ed., “Periodical Pedagogy,” special issue, Victorian Periodicals Review 39 (Winter 2006).

5 Trevor Fawcett and Clive Phillpot, eds., The Art Press: Two Centuries of Art Magazines—Essays Published for the Art Libraries Society on the Occasion of the International Conference on Art Periodicals and the Exhibition, The Art Press, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (London: Art Book Company, 1976). In March 1976, The Connoisseur published a special issue on the art press in conjunction with this exhibition, with articles by Bevis Hillier on The Connoisseur, Benedict Nicolson on The Burlington Magazine, Paul Goldman on Apollo, and others. The articles were mainly historical surveys or personal reminiscences of their editors. In parallel, the Art Libraries Society of North America (ARLIS/NA) and its newsletter, which later became the journal Art Documentation, provided bibliographies, source material, and debate on classification.

6 Trevor Fawcett, “Scholarly Journals,” in The Art Press: Two Centuries of Art Magazines, 13–20; Clive Phillpot, “Movement Magazines, The Years of Style” in The Art Press: Two Centuries of Art Magazines, 41–44; Laurel Brake and Julie F. Codell, eds., Encounters in the Victorian Press: Editors, Authors, Readers (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); Julie F. Codell, “The Art Press and the Art Market: The Artist as ‘Economic Man,’” in The Rise of the London Art Market, 1860–1939, ed. Anne Helmreich and Pamela Fletcher (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 128–50; Meaghan Clarke, “Critical Mediators: Locating the Art Press,” Visual Resources 26 (September 2010): 226–41; Anne Helmreich, “The Death of the Victorian Art Periodical,” Visual Resources 26 (September 2010): 242–53; Ysanne Holt, “The Call of Commerce: The Studio Magazine in the 1920s,” in Helmreich and Fletcher, The Rise of the London Art Market, 151–73.

7 Peter Brooker, Andrew Thacker, Sascha Bru, and Christian Weikop, eds., The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, 3 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009–2013).

8 Maria Rennhofer, Kunstzeitschriften der Jahrhundertwende in Deutschland und Österreich, 1895–1914 (Augsburg: Bechtermünz, 1997); Gianni Carlo Sciolla and Franca Varallo, L'Archivio storico dell'arte e le origini della Kunstwissenschaft in Italia (Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso, 1999); Gian Carlo Sciolla, Riviste d'arte fra Ottocento e etá contemporanea: Forme, modelli, funzioni (Turin: Skira, 2004); Alessandro Rovetta and Rosanna Cioffi Martinelli, eds., Percorsi di critica: Un archivio per le riviste d'arte in Italia dell'Ottocento e del Novecento (Milan: Vita e Pensiero, 2008).

9 The Modernist Journal Project by Brown University and the University of Tulsa: http://dl.lib.brown.edu/mjp/.

10 The digital humanities are developing quickly and hold significant promise. For a first analysis of the potential of visualization software in the study of (literary) periodicals, see James Stephen Murphy, “Looking at Magazines: An Argument for Not Reading,” in the blog Magazine Modernisms Dedicated to Modern Periodical Studies, June 19, 2012, http://magmods.wordpress.com/.

11 Luke Uglow, “The Life and Death of The Connoisseur,” Art Libraries Journal 39 (January 2014): 17–23.

12 On the significance of Art History within the discipline and its conflict with other journals, for instance, Apollo, see Jonathan Harris, The New Art History: A Critical Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2001), 7–10.

13 Patricia Bickers, “Art Monthly 1976–: On the Gentle Art of Staying the Same While Changing Utterly,” Art Libraries Journal 35 (January 2010): 5–11.

14 C. E. Brookeman, “Norman Rockwell and the Saturday Evening Post: Advertising, Iconography and Mass Production, 1897–1929,” in Art Apart: Art Institutions and Ideology across England and North America, ed. Marcia R. Pointon (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 142–74.

15 Harrison C. White and Cynthia White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965), 76–110; Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, “The Periodical and the Art Market: Investigating the “Dealer-Critic System” in Victorian England,” Victorian Periodicals Review 41 (Winter 2008): 323–51; Daniel Birnbaum and Isabelle Graw, eds., Canvases and Careers Today: Criticism and its Markets (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2008).

16 Helen Rees Leahy, “‘For Connoisseurs': The Burlington Magazine,” in Art History and its Institutions: Foundations of a Discipline, ed. Elizabeth Mansfield (London: Routledge, 2002), 231–45.

17 Trevor Fawcett and Clive Phillpot, “Introduction,” in The Art Press: Two Centuries of Art Magazines, 1–2. Julie F. Codell, “When Art Historians Use Periodicals: Methodology and Meaning,” Victorian Periodicals Review 34 (Autumn 2001): 284–89.

18 Rachel Teukolsky, The Literate Eye: Victorian Art Writing and Modernist Aesthetics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 4–5.