Abstract

The role of the art press has been proved crucial in the early formation of art history. The study of art criticism at the turn of the century, however, is still mainly focused on male figures, such as Roger Fry (1866–1934) and Bernard Berenson (1865–1959). In fact, evidence indicates that women were important contributors to these debates through their contributions in the new periodicals: The Studio, The Connoisseur, and The Burlington Magazine. This essay offers key examples of women writers, such as Julia Frankau (1859–1916), Julia Cartwright (1851–1924), and Mary Berenson (1864–1944). It explores thematic case studies on decorative art, the Old Masters, and collections history. Although these writers lacked institutional affiliations, their scholarly approaches overturn gender stereotypes of superficiality. Women writers were also often attuned to the interconnectivity of the press, collecting, art production, and the art market.

Decorative Art

In the cases which fill the centre of the rooms are the treasures of a hundred armoires and museums of old mansions. The pretty things a dowager brings out on wet days to show a favourite grandchild are here in profusion. Fans, miniatures, frocks and lace and a hundred other trifles … .Footnote1

Women have long been associated with the collecting of “pretty things,” but recent reassessments of Victorian and Edwardian objects and contexts have indicated their vital role in both producing and consuming decorative art.Footnote2 The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art and subsequently The Connoisseur presented to the reader an overlapping milieu of fine and decorative art, and the latter was an arena in which women were particularly vocal.Footnote3 This may have been partly to do with more prosaic factors affecting individual writers: women contributing to periodicals at the turn of the century were rarely women of leisure, and the financial remuneration garnered for their work varied. In Frances Low's 1904 volume titled Press Work for Women, she indicated that writers were paid fifteen shillings for columns in The Connoisseur, while some magazines paid less than half that amount.Footnote4 Thus, article placement then (as now) was crucial, and The Connoisseur became a preferred option for women who were independent professionals, reliant on their writing to support themselves and their families.

The initial number of The Studio contained articles on “Sir Frederick Leighton, Bart., P. R. A.” (1830–1896), Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898), and bookplates. An applied art reviews section included a tapestry by Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) for Morris and wallpapers by Walter Crane (1845–1915) and C. F. A. (Charles Francis Annesley) Voysey (1857–1941), thus demonstrating, as Peter Rose observes, how “strongly and overtly the Studio supported the Morrisian artist-craftsman.”Footnote5 Clive Ashwin notes that its editor, Joseph Gleeson White (1851–1898), tailored the content of the periodical to the preferences and tastes of the middle-class art lover and amateur, carefully avoiding the two extremes of stale academicism and incomprehensible avant-garde late impressionism and post-impressionism. More recently, Ysanne Holt has emphasized Studio’s participation in an international milieu of producers and consumers.Footnote6 The art writers reflected this growing cosmopolitanism and many women writers undertook travel and translation in order to view and document objects, exhibitions, and collections. Women writing about decorative art also appeared in the two mainstream periodicals. For example, Alice Mullins's Art Journal article of 1896 advocated for the consideration of jewelry as an artistic object along with other domestic arts.Footnote7 However, The Studio’s applied art focus meant it became a primary vehicle for women's publishing on decorative art.

Women wrote reviews of national and provincial exhibitions and articles on specific mediums like embroidery, mural painting, black-and-white illustration, and bookbinding. These reviews featured both male and female artists. For example, an 1896–1897 article in The Studio special winter issue, by Margaret Armour (1860–1943), focused on the Glasgow artist Phoebe Traquair (1852–1936) ().Footnote8 Armour expressed her concern at the lack of attention to illuminated manuscripts. Although she was a keen proponent of Scottish arts and crafts, her work was wide-ranging and her professional networks encompassed the New English Art Club and collaborations with Beardsley (her husband was the artist William Brown MacDougall, 1868–1936).Footnote9 The breadth of her writing corroborates recent scholarship suggesting that the late Victorian interior reveals a lack of firm demarcation between the aesthetic and Arts and Crafts movements.Footnote10

Figure 1 Margaret Armour, “Beautiful Modern Manuscripts.” Page from the article in The Studio, Special Winter Number, 1896–1897, p. 47.

However, the emphasis on decorative art also allowed for new specializations in the work of women writers. One woman who wrote voluminously on the history of decorative art was Emily Gatliff Nevill Jackson (Mrs. Frederick Nevill Jackson; 1861–1947). Her series of articles on the history of lacemaking and types of lace objects appeared in The Connoisseur, and she also wrote one on the subject for the early Burlington as well as serving on its first Consultative Committee.Footnote11 Nevill Jackson was one of several writers who wrote about lace and needlework (another was Lady Marian Alford [1817–1888], an early expert on lace for the Royal School at South Kensington), and certainly The Connoisseur articles, although aimed at the collector rather than the practitioner, drew on the South Kensington collection. In 1905, this relationship was reciprocated when Nevill Jackson offered her own substantial collection of lace for sale to South Kensington.Footnote12 Her articles and a volume titled A History of Hand-made Lace (1900)Footnote13 served as a catalyst for other women writers, such as Mrs. R. E. Head and Margaret Jourdain (1876–1951), to contribute to the field of lace and needlework in the new art presses.Footnote14 After 1905, Nevill Jackson turned her attention to a wide variety of other decorative subjects, including china collecting, bookplates, door knockers, toys, and silhouettes. And in 1911, her volume on the History of Silhouettes was published by The Connoisseur. For the purposes of her research, Nevill Jackson collected the albums of the early American silhouettes compiled by the French artist Augustin-Amant-Constance-Fidèle Édouart (1789–1861). These portraits of figures, such as United States President John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), were completed when Édouart spent a decade in America between 1839 and 1849. Interestingly, when the New York Historical Society declined to purchase them for £10 per figure, she sold them individually in addition to copies she had made as “photo facsimiles”; the entire set could be purchased for £800.Footnote15 Clearly, Nevill Jackson was a writer carefully attuned to the American interest in genealogy; she located a market, not only for her writing, but also for objects acquired in the process. Her example suggests that women were active agents in the correlation between collecting and writing about collecting.

The role of women writing about decorative art can be correlated with recent emphasis on the important role of women as consumers or “shoppers” during this period.Footnote16 While on the one hand, the association of women with a mode of collecting that involved shopping for beautiful or luxurious objects was in some sense reinforced by the numbers of women writing about decorative art for the art press, on the other hand, this association of women with “uninformed” collecting was complicated by the texts themselves.Footnote17 Women in these periodicals were more intent on establishing scholarly histories and approaches to collecting objects. Therefore, the implied reader was in fact acquiring objects about which she or he had expert knowledge.

Old Masters

During the late Victorian period, an area of expanding interest in art writing was historical scholarship on artists, particularly of the Renaissance and the eighteenth century, most notably members of the early Royal Academy. These initially appeared in The Art Journal, The Magazine of Art, and The Portfolio as articles as well as more elaborately illustrated supplements. Women contributed many of these early articles, demonstrating that they were not only attending exhibitions, but also traveling, moving between London and Italy, and doing research in archives. This concern for Old Masters was to become a primary focus of The Burlington Magazine. Footnote18 Trevor Fawcett highlights the importance of connoisseurship to the early Burlington, and in art historiography the names most frequently associated with the development of connoisseurship are the founder of this method, Giovanni Morelli (1816–1891), and Bernard Berenson; however several women writing at the fin de siècle were active in these debates. Many of these debates were played out on the pages of the press. One elusive figure was the American Mary Costelloe (née Smith, 1864–1944), who would become Mary Berenson in 1900, and scholars have struggled to unravel the exact details of her writing partnership with Bernard due to her anonymity and/or pseudonymity.Footnote19 Another little-known writer, Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes (d. 1950), appeared in the first number of the new Burlington with a methodically researched piece on the date of Vincenzo Foppa's death—1516, living twenty-three years longer than had been thought previously—deduced from a document in the archives in Brescia (). Ffoulkes would eventually publish her work on Foppa as a volume, but she already had established expertise in this arena. In The Magazine of Art, she had published an 1890 article, “Misnamed Pictures in the Uffizi,” and she had in fact translated Morelli's Italian Painters in 1892.Footnote20 Translation was another key aspect of early art historical scholarship that was often undertaken by women.

Figure 2 Vincenzo Foppa's lease. Document reproduced in Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes, “The Date of Vincenzo Foppa's Death Gleanings from the Archives of S. Alessandro at Brescia,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 1, March 1903, p. 105.

The scholars Vernon Lee (1856–1935) and Julia Cartwright (1851–1924) were also familiar with Morelli and part of a circle that included Berenson. Lee, the pseudonym of Violet Paget, also lived in Florence with ready access to Renaissance collections.Footnote21 New scholarship and revision focused on specific artists. One example was Lorenzo Lotto (ca. 1480–1556), who Cartwright had written about for The Portfolio in 1889, but a flurry of pieces on this artist emerged in 1895, beginning with Berenson's Lorenzo Lotto: An Essay in Constructive Art Criticism (G. P. Putnam's Sons) followed by articles from Cartwright and Mary Logan, the pseudonym of Mary Costelloe, in The Art Journal and The Studio. Footnote22 Berenson's essay was illustrated with works, such as the Holford Lucretia (1530–1532), then in Dorchester House and now in the National Gallery, London. Cartwright's diary reveals she had detailed discussion with Berenson about his essay pre-publication, and he had promised to review the book she was writing on Raphael.Footnote23 Logan had largely written Berenson's Venetian Painters, published the same year, although she withdrew her name as a co-author. This pseudonymous network re-emerged in 1903, in The Burlington, when Mary Berenson, under the initials M. L., reviewed Cartwright's latest book and found her to be a “gifted compiler,” “free from the taint of journalism.”Footnote24 Thus, what these articles show is that the early development of art historical empirical research, attribution, and analyses of works emerged from a complicated array of friendships, publicity strategies, and allegiances with lesser-known women writers.

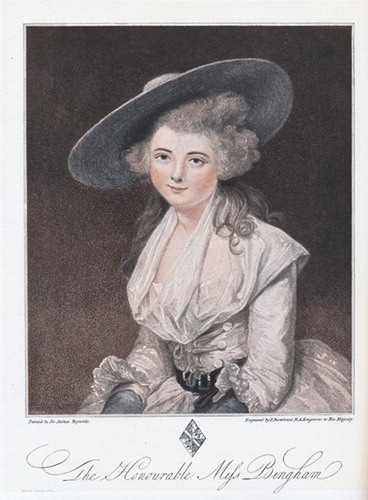

The study of the eighteenth century also underwent a revival at the turn of the nineteenth century. Vernon Lee and Emilia Dilke (1840–1904) both wrote histories of the eighteenth century. Dilke published a four-volume empirical study of French painters, architects, and sculptors, furniture and decoration, and engravers and draughtsmen.Footnote25 Many articles were also published on British artists, such as Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), George Romney (1734–1802), and Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788). Eighteenth-century prints were the subject of several articles and books by Julia Frankau (1859–1916); her first illustrated book on the topic came out in 1900.Footnote26 She was on The Burlington Consultative Committee and wrote an article in 1903 on five portraits by the artist John Downman, A. R. A. (1750–1824) held at the British Museum. She regaled readers with her own hunt in “dingy solitude” for the “drawings I have excavated from their mausoleum,” but went on to assert their importance, as specimens by a long-forgotten artist, now sought after by “great American millionaires.” Frankau, who came from a family prominent in literary and theatrical circles, was also a successful novelist, publishing under the pseudonym Frank Danby.Footnote27 In her Burlington article, she alluded to the value of Downman on the art market. Frankau had already addressed this aspect of print culture in the first year of The Connoisseur with “Prints and their Prices,” wherein she identified color engravings, as a “limited, narrow market,” with “no elements of stability.” Interestingly, Frankau wrote this piece in response to an article by the print dealer, Frank T. Sabin (1848–1915), thereby asserting her own authority on the market ().Footnote28

Figure 3 Francesco Bartolozzi (1727–1815), after Joshua Reynolds, The Honourable Miss Bingham. Engraving reproduced in Julia Frankau, “Prints and their Prices: A Small Collection,” The Connoisseur 1, September 1901, p. 180.

The writer Christiana Herringham (1851–1929), also on The Burlington Consultative Committee and a founder of the National Art Collections Fund, entered debates concerning the technique and authenticity of paintings. Herringham had considerable familiarity with the science of painting, having translated Cennino Cennini's (ca. 1370–1440) treatise on painting in 1899 and analyzed methods of reproducing early tempera painting.Footnote29 In relation to a collection of eighteenth-century portraits by Reynolds and Henry Raeburn (1756–1823), she wrote: “If picture-collectors would realize how easy it is to detect modern repaints and restorations, £4000 would not have been paid at Christie's recently for Lord Tweedmouth's Simplicity, formerly by Joshua Reynolds, now not, except for the general design and a portion of the hand.”Footnote30 Thus, while the burgeoning journals became a platform for women writing new histories of decorative art, capitalizing on its links with the domestic sphere, they also intervened in debates about fine art, connoisseurship, and the art market.

Anne Helmreich has recently shifted scholarly attention to “the art market, a little explored context in which the death of the old [art press] and the birth of the new needs to be situated.” She argues that the shift from the big, established journals to new, specialist magazines coincided with the rise of commercial galleries.Footnote31 Helmreich and Pamela Fletcher have investigated the dealer-critic system in Victorian England and Barbara Pezzini pinpoints its relevance in her examination of the market for Old Master paintings in The Burlington Magazine, The Burlington Gazette, and The Connoisseur. Pezzini observes that while The Connoisseur fully embraced the mechanisms of the market and related mostly to collectors and dealers, The Burlington and its Gazette maintained a more dialectical relationship with the art trade and intersected commercial, academic, and institutional interests.Footnote32 Pezzini's study does not focus specifically on women contributors, but both Frankau and Nevill Jackson exemplify this intersection of interests. They moved between the two journals, creating personal fields of object-expertise, while maintaining an acute awareness of the art market. This was established, at least in part, through buying (and selling) objects for the purposes of research. Thus, the careers of these women are a microcosm of the relationship between connoisseurship and the emerging discourse of art history.

Collectors and Collections

Although there was already a precedent for articles on collections in the established art journals, this was to be a particular feature of The Connoisseur, not surprisingly given that its intended audience was “collectors.” Writers, such as Frankau, Beatrice Strong Erskine (Mrs. Steuart Erskine; 1860–1948), and Lady Victoria (Alexandra Elizabeth Dorothy) Manners (1876–1933), contributed to the turn-of-the-century interest in individual collectors and their collections. The articles were similar to the existing “Artist and their Studios” format that had begun in The Magazine of Art and The Art Journal in the 1880s. This was an aspect of the Victorian fascination with biography,Footnote33 wherein readers were given, via engravings or photographs, as well as descriptive text, a peep into an artist's home. A biographical approach, it was asserted at the time, would give an insight into an artist's mind and a similar argument could be extended to individual collectors. Biographical articles gave readers a view into the homes and collections of both members of the British aristocracy and what Dianne Sachko Macleod terms “middle-class” collectors who had risen to prominence in forming taste. They were also allied with the growth in popularity of articles about personalities and celebrities that had emerged with the New Journalism in the 1880s. Frankau's articles documented the collectors, Lord Chesleymore and the varnish manufacturer George Harland Peck, and Erskine wrote about the Duke of Westminster's collection at Grosvenor House, Alfred de Rothschild's collection, and the Bridgewater and Ellesmere collections.Footnote34

Manners wrote a series of articles on the collections belonging to Harriet Sarah (née Lloyd), Lady Wantage (1837–1920). Her collection was primarily Old Masters amassed with her late husband. Manners emphasized Wantage's more recent collecting of nineteenth-century art by George Frederic Watts (1817–1904), Lawrence Alma Tadema (1836–1912), and Francis Bernard “Frank” Dicksee (1853–1928). Indeed, Lady Wantage, whose lifespan encompassed both the Victorian and Edwardian periods (and beyond), was an important cultural figure. This range and longevity in her patronage is indicated in her appearance in not only Henry Jamyn Brooks's painting, Private View of the Old Masters Exhibition, Royal Academy, 1888 (National Portrait Gallery, 1889), but also in two portraits (Tate, 1911; and private collection) by the fashionable portrait painter Philip Alexius Laszlo de Lombos (1869–1937). Manners had earlier done a series of articles on Belvoir in Leicestershire, more famously associated with the artist Violet Lindsay Manners (member of The Souls and wife of the 8th Duke of Rutland). Victoria Manner's father, John Manners, the 7th Duke of Rutland, had died in 1906, leaving Manners it seems to pursue a career in art and writing. Unlike other art writers, she had access through her familial networks to important collections, such as that of Wantage, which no doubt facilitated her work. Larger volumes by Manners on Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) and Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) were published in the ensuing decade.Footnote35

During the first decade of the twentieth century, Julia Cartwright was remarkably prolific, writing not only for the art press, but also publishing numerous books on Renaissance artists and patrons, including Sandro Botticelli (ca. 1445–1510), Raphael (1483–1520), and Isabella d'Este (1474–1539). But for the early Burlington, rather than contributing articles on Old Masters, she wrote a series of four articles on the drawings by Jean François Millet (1814–1875) in the collection of the engineer and railway manager James Staats Forbes (1823–1904).Footnote36 Although in some senses it was extraordinary for her not to be writing about the Renaissance for The Burlington, given her already established expertise in this area and scholarly networks, these were not without precedent. Throughout her career, Cartwright had published on Renaissance art alongside British and French nineteenth-century art, and her 1896 book on the Life and Letters of Millet had been reprinted in 1902. In the Millet publication, Cartwright had made several references to the importance and size (forty works) of the Forbes collection (indeed when Forbes died the collection was deemed too large to be sold as a single entity). The Burlington series enabled her to combine her knowledge of the artist with her already established knowledge of a Victorian collection of Barbizon, Dutch, and contemporary art that was about to come on the market.Footnote37 Cartwright is another example of a woman working at the intersection of the art market and art historical scholarship.

Scholars have demonstrated women's involvement in art museums at the end of the nineteenth century through cultural philanthropy, particularly in south London and the East End.Footnote38 However, women were also involved in public institutions, such as the Manchester Art Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), by this period, and Jordanna Bailkin has charted the prewar development of feminist museology.Footnote39 She cites the dramatic response to the potential sale of Hans Holbein's (ca. 1497–1543) Christina of Denmark in 1909 (now in the National Gallery). The painting was only saved for the nation when a mysterious female donor emerged at the eleventh hour. Lady Wantage's name was suggested as the mystery savior of Christina of Denmark. Another female patron, Lady Charlotte Schreiber (1812–1895), donated her collection to the V&A, ostensibly in memory of her husband, although her journal entries reveal a range of motivations, ranging from the formation of complex relationships with objects that aided in the process of self-actualization to the “transformation of the gendered ownership and interpretation of cultural property on a national level.”Footnote40 The existence of women philanthropists and patrons makes it perhaps less surprising that women were involved in documenting both collectors and collections in art journalism; indeed the two were directly linked. Moreover, women's expertise in matters of collecting continued a history of writing about private and public collections that had begun with Anna Jameson (1794–1860) decades earlier.

Conclusion

Intriguingly, both Lucretia and Christina of Denmark had appeared in 1894 at a hugely popular exhibition organized by the Ladies Committee at the Grafton Galleries, titled Fair Women, which contained historical and contemporary portraits of exemplary women as well as objects. The exhibition was a harbinger of the art press to come. Women had collectively brought together and displayed Old Master paintings, alongside objects, which they had collected and loaned themselves. The “pretty things” mentioned above in the quotation from The Studio article—“[f]ans, miniatures, frocks and lace and a hundred other trifles”—filled their houses. Over the next decade, women writers in the art press sought to define taste for collectors of fine and decorative art—those “treasures of a hundred armoires and museums of old mansions.”Footnote41

In summary, women writers made significant contributions to the art press that emerged at the turn of the century, although today their names are largely unknown. The interests of female art writers publishing in three periodicals reflected the diverse emphases in the journals themselves. These were indicative of shifts away from the established journals to encompass both fine and decorative art, and engaged more directly with collecting and the art market unlike their predecessors.Footnote42 All three journals, but particularly The Studio and The Connoisseur, offered new spaces for women to write about contemporary and historical decorative art. Similarly, all three journals published scholarly articles by women on Renaissance and eighteenth-century art, and women were represented as members of the original Consultative Committee of The Burlington, pointing to their important though virtually unrecognized voice in professional and publishing networks. Women were prominent contributors to the masses of material that appeared on collectors and collecting, especially in The Connoisseur.

To return to the question of women writing for the art press at the fin de siècle—Is it in part pragmatic and opportunistic because there was financial remuneration involved in writing for periodicals such as The Connoisseur?—there are several ways to understand the shift to writing about collecting and decorative arts. Certainly there is evidence that monetary concerns were crucial for women journalists, as was professional authority. Hilary Fraser, drawing on the work of Kali Israel, argues that female writers and artists appropriated the Renaissance to authorize for the “New Woman” intellectual self-development.Footnote43 Cartwright, who wrote a large tome on Isabella d'Este (1474–1839), exemplifies this. Similarly, eighteenth-century examples of “great women,” such as Lady Diana Beauclerk (1734–1808) and Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807), were identified by Erskine and others.

The new art press was also part of a shift in art writing from academic art to collecting and the art market. Whereas previously, art collectors relied on dealers to select works, the focus on a greater range of objects and art forms created a need for new forms of specialized knowledge. Did the proliferation of dealers and kinds of objects and greater complexity in “buying” create a role for women as advisers and interpreters through the press? We can see evidence of women acting as experts on the market. Scholars have emphasized the agency of women as consumers in the simultaneous transformation of London's West End to a mecca for department stores and cafés. It could be argued that women were able to gain entry into writing about “objects” because it reified their expertise as consumers. The evidence for this emerges in women writing about public collections as well as their own objects. However, their scholarly approaches to both decorative and fine art challenge assumptions about the frivolous interests of women collectors at the fin de siècle.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the excellent suggestions from reviewers. In addition, many thanks to the speakers and delegates at the “Art Press in the Twentieth Century” conference, organized by Sotheby's Institute of Art and The Burlington Magazine, especially my chair Barbara Pezzini and respondent Ysanne Holt.

Additional information

MEAGHAN CLARKE is Director of Doctoral Studies in the School of History, Art History, and Philosophy at the University of Sussex. She is the author of Critical Voices: Women and Art Criticism in Britain 1880–1905 (Ashgate, 2005), “Seeing in Black-and-White: Incidents in Print Culture, in Art History (June 2012), and “Sex and the City: The Metropolitan New Woman,” in The Camden Town Group in Context, edited by Helena Bonnet, Ysanne Holt, and Jennifer Mundy (Tate, 2012), http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/meaghan-clarke-sex-and-the-city-the-metropolitan-new-woman-r1105659. She has also published journal articles in Visual Resources, Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, Henry James Review, and Visual Culture in Britain along with essays in edited volumes, such as Critical Exchange: Art Criticism of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries in Russia and Western Europe, edited by Carol Adlam and Juliet Simpson (Peter Lang, 2009).

Notes

1 “From Gallery, Studio, and Mart. With Illustrations,” Studio 3 (June 1894): 89; online at http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studio1894a/0176.

2 The interior was a site for the empowerment of women in this period through both consumption and production. See Judith A. Neiswander, The Cosmopolitan Interior: Liberalism and the British Home, 1870–1914 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008); Imogen Hart, Arts and Crafts Objects (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010); See Lynne Walker and Anthea Callen for debates concerning the professional advantages for women artists: Anthea Callen, “Sexual Division of Labour in the Arts and Crafts Movement,” and Lynne Walker, “The Arts and Crafts Alternative,” in A View from the Interior: Feminism, Women and Design, ed. Judy Attfield and Pat Kirkham (London: Women's Press, 1989), 150–64; 164–73.

3 Trevor Fawcett and Clive Phillpot, eds., The Art Press: Two Centuries of Art Magazines—Essays Published for the Art Libraries Society on the Occasion of the International Conference on Art Periodicals and the Exhibition, The Art Press, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (London: Art Book Company, 1976); Ysanne Holt, “‘The Call of Commerce’: The Studio Magazine in the 1920s,” in The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939, ed. Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012), 151–73; Kristin Mahoney, “Nationalism, Cosmopolitanism, and the Politics of Collecting in The Connoisseur: An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors, 1901–1914,” Victorian Periodicals Review 45 (2012): 175–99.

4 Frances H. Low, Press Work for Women: A Text Book for the Young Woman Journalist. What to Write, How to Write It, and Where to Send It (London: L. Upcott Gill, 1904), 48; online at https://archive.org/details/pressworkforwom00lowgoog.

5 Peter Rose, “The Studio and the Arts and Crafts Movement,” in “High Art and Low Life: The Studio and the Fin de Siècle, Incorporating the Catalogue to the Exhibition High Art and Low Life: The Studio and the Arts of the 1890s, Victoria and Albert Museum, 23 June—31 October 1993,” special centenary issue, ed. Janet McKenzie and Michael Spens, Studio International 201 (1993): 12.

6 Clive Ashwin, “The Founding of The Studio,” in “High Art and Low Life,” 7; Holt, “Call of Commerce,” 152–53.

7 Alice Mullins, “Jewellery as an Art,” Magazine of Art (April 1896): 236–41.

8 Margaret Armour, “Beautiful Modern Manuscripts,” Studio (Special Winter Number 1896–1897): 47–55; online at http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studio1897/0370. See Elizabeth Cumming, Phoebe Anna Traquair, 1852–1936, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1993), 29; Annette Carruthers, The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland: A History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 151–73.

9 See, for example, Margaret Armour, “Edinburgh as a Sketching Ground,” Studio 6, no. 33 (December 1895): 164–70; online at http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studio1896/0179?sid=cb96733787e1d4a1194cde54212dbf55. This article suggests a more modern representation of landscape while engaging with what Ysanne Holt has identified as Studio's promotion of ruralism from its inception with articles on artists' haunts and sketching grounds. See Ysanne Holt, “The Camden Town Group and Early Twentieth-Century Ruralism,” in The Camden Town Group in Context, ed. Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, and Jennifer Mundy, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/ysanne-holt-the-camden-town-group-and-early-twentieth-century-ruralism-r1104365. See also Margaret Armour, “Aubrey Beardsley and the Decadents,” Magazine of Art (November 1896): 9–12, online at https://archive.org/stream/magazineofart20londuoft#page/8/mode/2up; and Jane Haville Demarais, The Beardsley Industry: The Critical Reception in England and France, 1893–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), 51.

10 Jason Edwards and Imogen Hart, eds., Rethinking the Interior, c. 1867–1896: Aestheticism and Arts and Crafts (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010).

11 Articles by Emily Gatliff Nevill Jackson (Mrs. F. Nevill Jackson) for The Connoisseur: “Lace and Needlework: The Evolution of Alençon Lace,” Connoisseur 1 (1901): 219–23, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus01lond#page/n285/mode/2up; “Lace and Needlework: English Coronation Robes,” Connoisseur 3 (1902): 156–61, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus03lond#page/156/mode/2up/search/jackson; “Lace and Needlework: Human Figures in Lace,” Connoisseur 4 (1902): 183–87, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus04lond#page/n229/mode/2up/search/jackson; “Lace: Ruffs,” Connoisseur 6 (1903): 164–73, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus06lond#page/164/mode/2up/search/nevill; “Lace: Cravats,” Connoisseur 9 (1904): 226–32, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus09lond#page/226/mode/2up/search/jackson; “Ecclesiastical Lace Ancient and Modern: A Comparison. Part I,” Burlington Magazine 4 (1904): 54–64.

12 See Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Nominal File E. Nevill Jackson: MA/1/J29. In 1905, the V&A agreed to purchase a blue embroidered border and two pieces of old brocade from the thirty-two items held at the dealers Walcots Antique Furniture, Lace, China, Silver, Glass and Prints.

13 Published in London by L. Upcott Gill and in New York by Charles Scribner's Sons; available online at https://archive.org/details/historyofhandmad00jack.

14 On contemporary production, see Janice Helland, “‘Caprices of Fashion’: Hand Made Lace in Ireland, 1883–1907,” Textile History 39 (November 2008): 193–222.

15 Emily Jackson Photograph Collection of Édouart's American Silhouette Portraits. New York Historical Society Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections, PR 101.

16 Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London's West End (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

17 On gender and collecting, see Sarah Cheang, “The Dogs of Fo: Gender, Identity and Collecting,” in Collectors: Expressions of Self and Other, ed. Anthony Shelton (London: Horniman Museum and Gardens, 2001), 55–72; Anne Anderson, “‘Chinamania’: Collecting Old Blue for the House Beautiful, c. 1860–1900,” in Material Cultures, 1740–1920: The Meanings and Pleasures of Collecting, ed. John Potvin and Alla Myzelev (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009), 109–28.

18 Helen Rees Leahy, “‘For Connoisseurs': The Burlington Magazine 1903–11,” in Art History and its Institutions, ed. Elizabeth Mansfield (London: Routledge, 2002), 231–45; Barbara Pezzini, “More Adey, the Carfax Gallery and The Burlington Magazine,” Burlington Magazine 153 (2011): 806–14; Elizabeth Prettejohn, “Out of the Nineteenth Century: Roger Fry's Early Art Criticism,” in Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art, ed. Christopher Green (London: Merrell Holberton, 1999), 31–44; Caroline Elam: “A More and More Important Work: Roger Fry and The Burlington Magazine,” Burlington Magazine 145 (2003): 142–52; Rachel Cohen, Bernard Berenson: A Life in the Picture Trade (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013); Joseph Connors, Louis Alexander Waldman, and Dietrich Seybold, eds., Bernard Berenson: Formation and Heritage (Florence: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, 2014).

19 Tiffany Johnston, “Mary Whitall Smith at the Harvard Annex,” Berenson and Harvard: Bernard and Mary as Students, ed. Jonathan Nelson (Florence: I Tatti, 2012), online exhibition and electronic catalog at http://berenson.itatti.harvard.edu/berenson/items/show/3030; Mary Berenson: A Self-Portrait from her Diaries and Letters, ed. Barbara Strachey and Jayne Samuels (London: Hamilton, 1985).

20 Constance J. Ffoulkes, “Misnamed Pictures in the Uffizi,” Magazine of Art (1890): 189–91; Giovanni Morelli, Italian Painters: Critical Studies of their Works, trans. C. J. Ffoulkes, 2 vols. (London: John Murray, 1892); Constance J. Ffoulkes and Rodolfo Maiocchi, Vincenzo Foppa of Brescia, Founder of the Lombard School, His Life and Work (London: John Lane The Bodley Head, 1909), online at https://archive.org/stream/vincenzofoppaofb00ffou#page/n11/mode/2up; see also Francesco Ventrella, “The Body of Art History: Writing, Embodiment and the Connoisseurial Imagination” (Ph.D. diss., University of Leeds, 2012).

21 Alison Brown, “Vernon Lee and the Renaissance: From Burckhardt to Berenson,” in Victorian and Edwardian Responses to the Italian Renaissance, ed. John E. Law and Lene Østermark-Johansen (Aldershot: Ashgate 2005), 185–209.

22 Julia Cartwright, “Lorenzo Lotto,” Portfolio (1889): 16–19, 26–30, online at http://scans.library.utoronto.ca/pdf/7/35/portfolioh20hame/portfolioh20hame.pdf; Julia Cartwright, “Lorenzo Lotto,” Art Journal (August 1895): 233–37; Mary Logan, “On a Recent Criticism of the Works of Lorenzo Lotto,” Studio 26, no. 5 (May 1895): 63–67; online at http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/studio1895/0079?sid=cb8d5d26b4a523e682d10f3ff291ff99.

23 Julia Cartwright, A Bright Remembrance: The Diaries of Julia Cartwright, 1851–1924, ed. Angela Emmanuel (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989), 188–92.

24 M. L. [Mary Logan], “Isabella D'Este, Marchioness of Mantua, 1474–1539: A Study of the Renaissance,” Burlington Magazine 2 (June 1903): 106–7. Mary Berenson's praise for Cartwright was not effusive, which also reveals shifts in these friendships and the development of Mary Berenson's role as Berenson's (pseudonymous) advocate. Mary Berenson was highly critical of the archival, as opposed to connoisseurial, approach of Gustave Ludwig and Pompeo Molmenti writing on Carpaccio; M. L. [Mary Logan], “Vittore Carpaccio el la Confrerie de Sainte Ursule a Venise,” Burlington Magazine 3 (December 1903): 317–21; see also M. L. [Mary Logan], “Pintoricchio: His Life, Work, and Time,” Burlington Magazine 2 (July 1903): 265–57. Many thanks to Barbara Pezzini for her helpful analysis of these three articles.

25 Lady [Emilia] Dilke, French Painters of the XVIIIth Century (London: Bell, 1899), online at https://archive.org/stream/cu31924008752366#page/n9/mode/2up; French Architects and Sculptors of the XVIIIth Century (London: Bell, 1900), online at https://archive.org/stream/cu31924030658748#page/n9/mode/2up; French Furniture and Decoration in the XVIIIth Century (London: Bell, 1901); online at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001470958; French Engravers and Draughtsmen of the XVIIIth Century (London: Bell, 1902), online at https://archive.org/stream/frenchengraversd00dilk#page/n9/mode/2up.

26 Julia Frankau, Eighteenth Century Colour Prints: An Essay on Certain Stipple Engravers and Their Work in Colour Illustrated with Fifty-two Characteristic Pictures Printed in Colours from Copper-plates (London: Macmillan, 1900); An Eighteenth Century Artist and Engraver. John Raphael Smith: His Life and Works with Thirty Photogravures (London: Macmillan, 1902); William Ward A. R.A., James Ward R. A.: Their Lives and Works (London: Macmillan, 1904), online at https://archive.org/stream/gri_33125002368963#page/n9/mode/2up.

27 Julia Frankau, “A Note on Five Portraits by John Downman, A. R. A.,” Burlington Magazine 1 (1903): 122; Todd M. Endelman, “The Frankaus of London: A Study in Radical Assimilation, 1837–1967,” Jewish History 8 (March 1994): 117–54.

28 Julia Frankau, “Engravings: Prints and their Prices: A Small Collection,” Connoisseur 1 (November 1901): 181–89, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus01unse#page/218/mode/1up.

29 The Book of the Art of Cennino Cennini: A Contemporary Practical Treatise on Quattrocento Painting, trans. Christiana Herringham (London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1899). Herringham was also a founder of the Society of Painters in Tempera. See Hannah Spooner, “Pure Painting: Joseph Southall, Christiana Herringham and the Tempera Revival,” British Art Journal 4 (2003): 49–56; Mary Lago, Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian Art Scene (London: Lund Humphries, 1996).

30 Christiana Herringham, “The Tweedmouth Pictures,” Burlington Magazine 7 (1905): 335–56. See Christie, Manson & Woods, London, Catalogue of Highly Important Pictures of the Early English School and Works by Old Masters, the Property of the Rt. Hon. Lord Tweedmouth, June 3, 1905, lot 43, [auction catalog], 16. A version in Waddesdon, National Trust: Joshua Reynolds, Miss Theophila Gwatkin (1782–1844) as Simplicity, ca. 1785, oil on canvas, in the Rothschild Collection.

31 Anne Helmreich, “The Death of the Victorian Art Periodical,” Visual Resources 26 (September 2010): 242.

32 Barbara Pezzini, “The Burlington Magazine, The Burlington Gazette, and The Connoisseur: The Art Periodical and the Market for Old Master Paintings in Edwardian London,” Visual Resources 29 (September 2013): 154–83.

33 Julie Codell, The Victorian Artist: Artists' Lifewritings in Britain, ca. 1870–1910 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 45–71.

34 Julia Frankau, “Collections Visited: Lord Cheylesmore's Mezzotints,” Connoisseur 2 (1902): 3–13, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseur02londuoft#page/n21/mode/2up; Julia Frankau, “Collections Visited: Mr. Hartland-Peck's Collections,” Connoisseur 5 (1903): 84–91; Mrs. Steuart Erskine [Beatrice Strong Erskine], “Collections Visited: Duke of Westminster's Collection at Grosvenor House,” Connoisseur 1 (1901): 209–16, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus01lond#page/208/mode/2up/search/erskine; Mrs. Steuart Erskine [Beatrice Strong Erskine], “Notable Collections: The Collection of Mr. Alfred de Rothschild in Seamore Place,” Connoisseur 3 (1902): 71–79, online athttps://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus03lond#page/n99/mode/2up/search/erskine; Mrs. Steuart Erskine [Beatrice Strong Erskine], “Collections Visited: The Bridgewater and Ellesmere Collections in Bridgewater House,” Connoisseur 6 (1903): 3–10, online at https://archive.org/stream/connoisseurillus06lond#page/n23/mode/2up/search/erskine.

35 See Lady Victoria Manners, Matthew William Peters, R. A.: His Life and Work, with a Catalogue of His Paintings and Engravings after His Works (London: The Connoisseur, 1913), online at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007695912; Lady Victoria Manners and G. C. Williamson, John Zoffany, R. A., His Life and Works, 1735–1810 (London: John Lane, 1920), online at https://archive.org/details/johnzoffanyrahis00zoffuoft; Lady Victoria Manners and G. C. Williamson, Angelica Kauffmann: Her Life and Her Works (London: John Lane, 1924).

36 Julia Cartwright, “The Drawings of Jean-François Millet in the Collection of Mr. James Staats Forbes. Part I,” Burlington Magazine 5 (April 1904): 47–67; Part II, 5 (May 1904): 118–59; Part III, 6 (December 1904): 192–203; Part IV, 6 (February 1905): 361–69.

37 Dianne Sachko Macleod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class: Money and the Making of Cultural Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 416.

38 Simon Joyce, “Castles in the Air: The People's Palace, Cultural Reformism, and the East End Working Class,” Victorian Studies (Summer 1996): 513–38; Seth Koven, “The Whitechapel Picture Exhibitions and the Politics of Seeing,” in Museum Culture: Histories, Discourses and Spectacles, ed. Daniel J. Sherman and Irit Rogoff (London: Routledge, 1994), 22–48; Shelagh Wilson, “‘The highest art for the lowest people’: The Whitechapel and Other Philanthropic Art Galleries, 1877–1901,” in Governing Cultures: Art Institutions in Victorian London, ed. Paul Barlow and Colin Trodd (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), 172–86; Diana Maltz, British Aestheticism and the Urban Working Classes, 1870–1900: Beauty for the People (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005).

39 Jordanna Bailkin, The Culture of Property: The Crisis of Liberalism in Modern Britain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 118–58.

40 Dianne Sachko Macleod, “Art Collecting As Play: Lady Charlotte Schreiber (1812–1895),” Visual Resources 27 (March 2011): 18–31.

41 “From Gallery, Studio, and Mart,” 89.

42 Julie Codell, “The Art Press and the Art Market: The Artist as ‘Economic Man,’” in Helmreich and Fletcher, The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 128–50.

43 Hilary Fraser, “Writing a Female Renaissance: Victorian Women and the Past,” in Law and Østermark-Johansen, Victorian and Edwardian Responses to the Italian Renaissance, 165–84.