ABSTRACT

This article focuses on communities’ contributions to a way of learning that seems to be common in many Indigenous communities of the Americas and among people with heritage in such communities: Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours (LOPI). We briefly contrast this with community contributions in Assembly-Line Instruction, a way of learning that is common in Western schooling, to highlight the distinct contributions of community in these two ways of learning. We theoretically situate the two ways of learning, considering communities and individuals as mutually constituting aspects of the process of life, not as separate entities. Then we discuss the contributions of community to the reasons that people participate, how they interact, and the underlying theory of learning and purpose of learning in LOPI. We briefly address the role of community in how people communicate with each other and evaluate learning. To conclude, we consider the prevalence of LOPI both within Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas and elsewhere, and our hopes for the contribution of describing this way of learning.

RESUMEN

Este artículo se enfoca en las contribuciones de la comunidad a un modo de aprender que parece ser común en muchas comunidades indígenas de las Américas y entre los pueblos descendientes de estas comunidades: Aprender por medio de Observar y Acomedirse en actividades de la familia y la comunidad (LOPI, por sus siglas en inglés). Comparamos brevemente estas contribuciones de la comunidad en Instrucción en Línea de Ensamblaje, un modo de aprendizaje común en las escuelas occidentales, para poner de relieve las contribuciones distintas de la comunidad en estos dos tipos de aprendizaje. Situamos teóricamente ambos modos de aprender, mientras consideramos a las comunidades y a las personas como aspectos mutuamente constituyentes del proceso de vida, no como entidades separadas. Después discutimos las contribuciones de la comunidad en torno a las razones por las que participan las personas, cómo interactúan, y la teoría subyacente del aprendizaje y el objetivo de aprender en la pers- pectiva LOPI. También abordamos brevemente el papel de la comunidad en cómo se comunican las personas entre ellas y evalúan el aprendizaje. Por último, consideramos la prevalencia de LOPI en las comunidades de herencia indígena de las Américas y en otros contextos, así como nuestras esperanzas respecto a la contribución de describir este modo de aprender.

This article focuses on communities’ contributions to a way of learning that seems to be especially common (but not inevitable) in many Indigenous communities of the Americas and among people with heritage in such communities: Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours (Rogoff, Citation2014; Rogoff, Aceves-Azuara et al., Citation2017). We briefly contrast this with community contributions in a way of learning that is common (but not inevitable) in Western schooling — Assembly-Line Instruction — to highlight the distinct contributions of community in these two ways of learning. Often, researchers and the mainstream public think that learning is an activity of individuals — both individual learners and those who guide them. Of course individuals are part of the story — but community contributions in learning and learning opportunities are often overlooked.

In this chapter, we first situate the two ways of learning in a theoretical view of communities and individuals as mutually constituting aspects of the process of life, not as separate entities. We then discuss our reasons and process for creating models to attempt to describe the contrasting features of the two ways of learning. Creating the models is an ongoing process — in this article we present new versions; the previous version of the model describing Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours was published eight years ago (Rogoff, Citation2014).

Next we focus on the importance of community contributions in Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours (LOPI). We briefly contrast community contributions in LOPI with the central role of community contributions in Assembly-Line Instruction (ALI), especially as related to people’s ways of learning and why they take part.

Turning our primary attention to Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours, we discuss the contributions of community to why people participate, how they interact and the underlying theory of learning and what learning is for, in LOPI. We briefly address the role of community in how people communicate with each other and evaluate learning. To conclude, we consider the prevalence of LOPI both within Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas and elsewhere, and our hopes for the contribution of describing this way of learning.

Communities and individuals — mutually constituting

In focusing on the role of community, we are not arguing that community is more important than individuals — indeed, we do not see individuals and communities as separate entities (Rogoff, Citation2011). Rather, we see individuals and communities as mutually constituting in ongoing historical and developmental processes — they are simply distinct foci of analysis in mutual process (Rogoff, Citation1995). We are drawing attention to the importance of community in order to counteract a common tendency in mainstream thinking (such as in psychology research, US public policy, and parenting advice) to consider learning as a property of solo individuals, sometimes ‘influenced’ by one or two other people (Rogoff, Citation2003).

Cultural researchers of human development have for decades called attention to the importance of community ways of organizing children’s lives — their ecologies or ‘niches’. The key role of communities has especially been highlighted in the work of Urie Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) and Beatrice Whiting and her intellectual descendants (e.g., Rogoff, Citation2003; Super & Harkness, Citation1997; Weisner, Citation2002). Whiting (Citation1980) drew attention to the settings that a society prescribes for children, with distinct community norms of expected behaviour in distinct settings.

Each setting is characterized by an activity in progress, a physically defined space, a characteristic group of people, and norms of behavior – the blueprint for propriety in this setting. Thus a child moving from the classroom to the playground interacts with adults and peers in a different manner. The standing rules for these settings do not prescribe the same type of social interaction. (Whiting, Citation1980, p. 104)

Attention to the differing ‘standing rules’ of distinct settings has yet to be taken up by the mainstream of researchers of human learning and development (Rogoff, Alcalá et al., Citation2014). However, many ethnographers have described communities’ ways of organizing learning that are quite distinct from the ways that are common in highly schooled communities and in Western schooling itself, such as children having responsible roles, included broadly in community activities (e.g., Cole & Scribner, Citation1981; Erickson & Mohatt, Citation1982; Fortes, Citation1938/1970; Gaskins, Citation1999, Citation2020; Paradise, Citation1998; Philips, Citation1983). In addition, Indigenous autobiographies and scholarly accounts have made observations of Indigenous American ways of learning — emphasizing the importance of children’s astute observation in the context of inclusion as contributors to community activities — sometimes contrasting these ways with the ways that learning is organized in Western schooling (e.g., Bang et al., Citation2016; Cajete, Citation1994; Kawagley, Citation1995; Pelletier, Citation1969; Swisher, Citation1990).

Such accounts, as well as experience in a Guatemalan Mayan community, inspired Rogoff (Citation1990, and before) to offer the concept of guided participation, to widen Vygotsky’s concept of the zone of proximal development, which focused on school learning and settings. The concept of guided participation includes the explicit and tacit contributions of other people and of varying community arrangements, together with children’s own initiative in learning. Guided participation encompasses many ways that children, other people, and communities contribute to organizing children’s (and others’) learning. For example, it includes both the contrasting approaches seen in informal learning arrangements as well as in the formats of Western schooling (Greenfield, Citation1984; Greenfield & Lave, Citation1982; Scribner & Cole, Citation1973).

The concept of guided participation was also created to emphasize the mutually constituting relation of the contributions of learners and the contributions of other people and of communities. At the same time as individual children and others take initiative, they do so in worlds that also channel the learning opportunities that they are allowed and encouraged to take part in and the roles they are encouraged or constrained to play. Learning occurs in the context of community ideas of what childhood is, how and why and what people should learn, and expectations regarding acting in accord with local values and local ‘normal’ practices. These community roles are constituted by and constitute the everyday lives of children, in a mutual process in which individuals and community are not separable. We see this as a continually changing historical process in which people’s ideas and actions contribute to the ongoing adaptations and ruptures in communities’ ways at the same time that communities’ ways contribute to the possibilities and development of the individual people involved in them, in a sort of fractal process (Dayton et al., Citationin press; Dayton & Rogoff, Citation2016; Marin, Citation2020; Rogoff, Citation2003, Citation2011; Rosado-May et al., Citation2020). This article draws attention to the role of community contributions in two common forms of guided participation.

Articulating the features of distinct ways of learning

Our primary focus is on understanding the role of community throughout the different features of Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours (LOPI). We contrast LOPI with Assembly-Line Instruction (ALI) as a way to bring forward the key features of LOPI by comparison with a way of organizing learning that is familiar to many readers who have extensive experience in Western schooling, where ALI remains common (but is not inevitable).

LOPI and ALI are not opposites; they are two ways of organizing learning among many others. (Some other approaches include guided repetition as described by Leslie Moore in Rogoff et al., Citation2007, and instructional conversation, as described by Tharp & Gallimore, Citation1988.) Our aim in comparing LOPI and ALI is to understand the LOPI paradigm and describe its features.

The LOPI and ALI models that we focus on in this article are attempts to describe the coherent features of two distinct paradigms differing in the ways that people learn and organize learning for themselves and others. We attempt to describe LOPI — and ALI by means of contrast — in order to bring attention to the coherence and the interrelated aspects of these ways of organizing learning. In this article, we discuss how community-wide worldviews, values and practices are central in both LOPI and ALI and have ramifications in the six other key interrelated features of each of these learning paradigms — the reasons that individuals take part, the ways people interact with each other, the ways that learning is conceptualized, the processes involved in learning, the primary forms of communication, and the role of evaluation.

In describing LOPI and ALI, we are trying to make the tacit nature of principles underlying ways of learning more explicit, as a way of aiding the consideration of alternative ways of organizing learning. This is important for several reasons:

(1) ALI has been shown to be an ineffective way of promoting learning, in research extending over more than a century (National Research Council, Citation2001). But ALI is still taken for granted in many places as the natural or normal way to organize learning. Many alternatives to ALI have been proposed and implemented in schools and other Western institutions, but often without consideration of how the principles of the alternatives cohere and differ from the principles of the prevailing ALI model. Often, attempts to move beyond ALI adopt piecemeal changes. One reason we see for describing the coherent features of LOPI is that we see LOPI as one promising alternative paradigm that could be used more broadly in middle-class families, schools and other institutions where ALI prevails (Rogoff et al., Citation2001). We hope that articulating the coherent defining features of LOPI as a multifaceted paradigm could facilitate understanding of this way of learning and inspire systematic descriptions of other alternative paradigms for learning.

(2) Experience and facility in the LOPI paradigm appear to provide important strengths for learning among people in many Indigenous communities of the Americas, and the LOPI paradigm itself seems to be a powerful and positive strength of families and communities. However, children’s learning and the family and community organization of these communities are often judged according to a deficit model based on assumptions that the ways of highly schooled communities are ‘normal’ (Bang et al., Citation2016; Rogoff, Coppens, Alcalá et al., Citation2017). Limited involvement with the ALI approach is treated as a deficit, and Indigenous practices are often seen as an impediment to both individual and societal ‘progress’, among people with extensive experience in Western schooling and other colonial institutions (Bonfil Batalla, Citation1996; Chaudhary & Sriram, Citation2020; Rogoff, Citation2003, Citation2011). We hope that articulating the features of LOPI will contribute to respect for a way of learning that is common in many Indigenous communities of the Americas, and we hope that the LOPI model is of use in Indigenous efforts to maintain and vitalize local ways of raising children and protect valued cultural practices, in the face of colonizing and globalizing forces.

The LOPI model

Our understanding of LOPI has been inspired and informed by observations in settings in which LOPI appears to be especially common. We have made use of the opportunities afforded by our collaborations among insiders and outsiders and those in between to create and continue to revise the LOPI model as a bridge to communicate the features of approaches that are taken for granted by some people, at the same time that they are strange and counterintuitive to others. We are trying to describe a way of organizing learning that is recognizable to members of the communities that commonly use it, as well as understandable to members of communities where the approach is not so common or recognized. This is a work in process; the newest prism is offered as the current effort to bridge understandings across communities that hold ideas that are not readily translated.

Our insider/outsider process of studying Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours involves a much larger ‘we’ than the two authors of the present article and the contributors to the LOPI model. Our understanding of LOPI has developed thanks to the writings of other scholars, especially the descriptions of learning in Indigenous communities of the Americas, and theorizing about this phenomenon by Indigenous American scholars writing about Indigenous Knowledge Systems (e.g., Bang et al., Citation2016; Barnhardt & Kawagley, Citation2005; Battiste, Citation2010; Brayboy & Maughan, Citation2009; Cajete, Citation1994; Urrieta, Citation2015). We have also learned a great deal about LOPI through our own decades of everyday participation, discussions, and research in several Indigenous and Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas (especially San Pedro la Laguna, in Guatemala, and San Juan de Ocotán, in Mexico, as well as several Native American communities in the USA and Mexican immigrant communities in the Santa Cruz and Los Angeles areas).

We have deepened our understanding of LOPI through several decades of conversations with about 60 other researchers engaged together in studying aspects of LOPI in Indigenous communities of the Americas. These conversations are the work of an interdisciplinary, international LOPI consortium of scholars. A large proportion of the participants in the consortium have grown up in Indigenous American communities. All have done research and lived in Indigenous or Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas. The writings of many participants in the consortium are cited in this article, and some have contributed articles to the special issue of which the present article is a part.

Our research on LOPI in Indigenous American communities has two entangled motivations: we study LOPI in a number of Indigenous communities of the Americas where LOPI is common to help us understand and describe this way of learning; and we hope that an explicit description of LOPI helps promote understanding of an approach that appears to be valued in many Indigenous American communities, both for members of those communities and for interested others.

For Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours to be common in many Indigenous American communities, as it appears to be, does not mean that it is a defining feature of Indigenous American ways, nor does it mean that people in Indigenous American communities inevitably follow this approach, even if they do so more often than people in some highly schooled, middle-class communities. The fact that LOPI has been noted in many Indigenous American communities also does not mean that it occurs in all Indigenous American communities, or at all times in any of them. Indigenous and Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas have also experienced European- and African-heritage cultural ways, often for centuries. (See Rogoff, Alcalá et al., Citation2014. Also see Medaets, Citation2016, for research indicating that while some of the features of LOPI are common, others are not characteristic of childrearing in an Amazonian region with a mixture of Portuguese, African and Amerindian backgrounds.)

Indeed, people are skilled in learning and using more than one approach, applying different practices from their repertoires according to changing and distinct circumstances (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, Citation2003; Rogoff, Citation2003). Change and flexibility are important processes of communities, as well as individuals, who change in some ways and persist in some ways — over very short and very long timespans (Dayton et al., Citation2022; Rogoff, Citation2011). Further, the possibility of enduring and commonly held values and practices across many Indigenous American communities should not obscure the many important differences among these communities (Rogoff, Citation2011; see also Leonard, Citation2021).

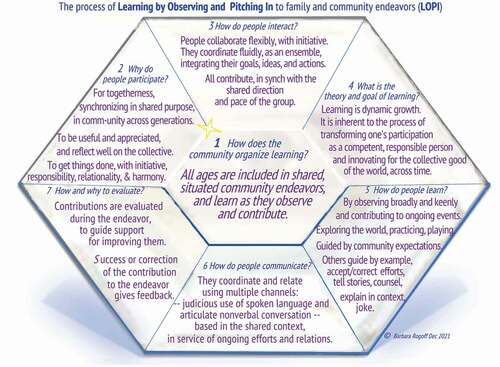

To delineate the features of LOPI, Rogoff and colleagues have developed — and continue to refine — a holistic model diagrammed as a prism with seven facets. The choice to diagram the features of LOPI in the form of a prism is intended to emphasize that all seven descriptive features are highly interrelated aspects (not components) of a single, multifaceted phenomenon. LOPI is described by the conjunction of all facets of the prism. Note that the LOPI prism is a theoretical model; it does not directly translate into a coding system to apply to moments of social interaction to determine whether an event ‘is or is not LOPI’. Recognizing a way of learning as fitting with LOPI would require consideration of all seven facets, over some time. In particular, to determine whether an event fits with the LOPI model requires examination of the overall community organization and context — the central facet in the LOPI model.

The questions that each of the seven facets of the LOPI model address are the same questions for the ALI prism, but of course the answers to the questions differ. The questions are thus a framework for describing these two ways of organizing learning and may be useful for developing descriptions of other ways of organizing learning (such as in the prism describing guided repetition offered by Leslie Moore in Rogoff et al., Citation2007). The numbers on the facets are for ease of reference; they do not denote a sequence — each of the seven facets represents an aspect of a whole process.

In this article, we present an update of the LOPI prism that attempts to bring the features of this way of learning into greater clarity than in previous versions, and especially to clarify the importance of community values, practices and ecologies. (See . See also a video overview of LOPI, https://videohall.com/p/2274.) The last published version of the LOPI prism was created almost a decade ago (Rogoff, Citation2014); the 2014 version was a revision of prior prisms that were referred to as Intent Community Participation or Intent Participation.

Figure 1. The 2021 LOPI prism, with seven facets that together describe a way of learning that appears to be common in many Indigenous and Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas.

Those prior versions, like the current one, are all efforts to describe the paradigm of Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours, in ways that communicate with audiences for whom this paradigm is common sense but tacit, as well as audiences for whom this paradigm is news. The changes in the prism over several decades reflect deepening understanding of the phenomenon as well as efforts to describe the phenomenon in ways that resonate with people from Indigenous communities of the Americas and communicate the approach to people who have little experience with Indigenous ways. As such, creating and revising the LOPI model is an effort to make use of the different positionalities and knowledge of insiders, outsiders and those of us who have some experience in navigating both LOPI and ALI (like all of the participants in the international research consortium mentioned above).

The central role of community in the LOPI model

Community values, practices, and ecology are key to the LOPI way of learning. But as mentioned earlier, they do not exist separately from the people who embody them, resist them, modify them. Community aspects and individual aspects of cultural processes are mutually constituting in a dynamic process of change and continuities across moments, years, decades and centuries (Rogoff, Citation1995, Citation2003, Citation2011).

The LOPI prism centres how the community organizes learning: ‘All ages are included in shared, situated community endeavors, and learn as they observe and contribute’ (Facet 1). This inclusion can be seen in the observations of Morelli et al. (Citation2003), which found that three-year-olds in a Guatemalan Maya community were considerably more often within eye- and earshot of people working than were children from two middle-class European American communities. The cultural value system of inclusion of children to support their learning has been emphasized over centuries, appearing in ancient Nahuatl texts from centuries ago in central Mexico (Chamoux, Citation2015, Citation2022, this volume) and in twenty-first-century practices in Yucatec Maya families (Gaskins, Citation2020; Jiménez-Balam et al., Citation2019).

Over the years, the importance of community aspects of the LOPI learning process has been difficult to convey. It has been easier for many highly schooled people who hear about LOPI to see the interpersonal or individual aspects of the process, but they often overlook or lose sight of the parts played by communities’ values, practices, and ecologies. The effort to highlight the importance of community contribution is apparent in the changes in the name of this model, over several decades, from ‘intent participation’ to ‘intent community participation’ to currently, ‘Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours’.

An ethical emphasis on relationality, reciprocity, responsibility and respect

In many Indigenous communities in the Americas, everyday practices are built on a cosmology that emphasizes the four ethical qualities of relationality, reciprocity, responsibility and respect (Brayboy et al., Citation2012; Elliott & Meixi, Citation2022, this volume; Leonard, Citation2021). As we see it, LOPI is based on concepts that fit with the cosmology of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, such as inclusiveness, relationality, mutuality, collaboration, autonomy, mutual respect, shared purpose, dynamic process, presence, embodiment, guidance. The expectations based in this ethical system may be explicit as well as implicit in everyday life.

An example of a community expectation that guides children’s learning in relationality, reciprocity, responsibility and respect is the Mexican value of being acomedido/a. People acting in accord with this value system are alert to what is going on around them to detect what needs to be done, and they take initiative, spontaneously lending a hand (López et al., Citation2012). Children are often pleased and proud to be able to help by being acomedido/a (Gaskins, Citation2020; Murray & Tizzoni, Citation2022, this volume). Relatedly, Elliott and Meixi (Citation2022, this volume) refer to the honour and affirmation of being included in a responsible role in an important community event.

An example of the expectation of being acomedida/o comes from RMA’s observations at a food stand that was selling hot meals in a market in Mexico, where a girl of about 12 was helping by clearing customers’ plates when they had finished. At that age, a child would be expected to routinely be acomedida. On one occasion, however, the girl did not notice that there were dirty plates to be cleared, and other customers were waiting. Her mother was not able to catch the girl’s eye to signal her to ‘wake up’, so the mother quietly said, firmly but not harshly, ‘Acomídete, m’ija’ [‘Be acomedida, honey’], to alert (not scold) her daughter, her teammate. The girl immediately and cheerfully hopped to, clearing the plates.

The importance of being acomedido/a is sometimes made explicit in complaints that someone is not being acomedido/a. For example, ‘Why can’t you be acomedido/a like your cousin?’ However, the community expectation to be acomedido/a is also implicit, as children can observe that people around them automatically help the host at a party, help fix something that breaks, and casually pitch in when help is needed. A similar valued set of practices based in mutual closeness and ‘caring’ is estar ahí (being there) and estar pendiente (‘being alert/aware of others’ needs and requirements by means of a proactive attitude that avoids waiting to be asked for help or favors’) among Mapuche Indigenous families in Chile (Murray et al., Citation2017, p. 373).

Community inclusion of all ages in the multigenerational endeavours that pervade the organization of the community, and the acceptance and encouragement of contributions by anyone and everyone, echo in the other facets of the LOPI prism. (Again, this phenomenon does not imply that Indigenous American parents are always accepting and encouraging!) The emphasis of LOPI Facet 1 on the community’s inclusion of children in valued multigenerational activities is especially reflected in Facet 5.

Community values, practices, and ecologies guide ways of learning (Facet 5) in LOPI

In LOPI, key ways of learning include paying wide, keen attention and contributing to ongoing family and community events (Facet 5). Paying attention and contributing clearly depend on being included in ongoing family and community events (Facet 1). Co-presence and observing are essential for learning, so much so that a way of saying that a person has truly learned something, in the ancient Nahuatl language and in modern Yucatec Maya expression, is to say that the learning ‘has settled in the eye’ (Cervera-Montejano, Citation2022, this volume; Chamoux, Citation2022, this volume). While contributing, learners have the opportunity for experiential learning, embedded in everyday social and communal processes. For example, Professor Emma Elliott recalls that in her Cowichan community, ‘I was cutting and smoking fish since the age of 4 years old with adult sharp knives’ (personal communication, 30 June 2021). This experience is supported by learning across a lifetime and geared towards fostering self-worth, belonging, competence, independence and reciprocity (Brendtro et al., Citation2019; Paradise & Rogoff, Citation2009).

Another way of learning in LOPI is to play at carrying out mature roles, guided by community expectations. This can only occur if people are included in mature activities that they can observe and emulate. Cultural differences in children’s access to community activities and accompanying forms of play were clear in the observations of three-year-old children by Morelli et al. (Citation2003): Mayan toddlers were more often in the presence of other people working, and they were more likely to emulate mature work and other roles in their play than were three-year-olds from two middle-class European American communities. By trying out mature skills and roles in play that they could routinely observe and take part in (Facet 5), their learning was thus based in the community’s inclusion of children in multigenerational events as observers and contributors (Facet 1).

The importance of the community’s practice of inclusion and encouragement of contribution is also key to Facet 5ʹs specification that people learn through the guidance provided by community-wide expectations based in the community’s worldview, values, and practices. The kind of contribution that characterizes LOPI is well illustrated in communities that expect children, and everyone else, to be alert to what is needed and to pitch in when something needs to be done, using the value system and practices of being acomedido/a, explained above.

Guided by such cultural expectations, children in many Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas show impressive helpfulness, often helping at home without being asked (Alcalá et al., Citation2014; Coppens et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Murray & Tizzoni, Citation2022, this volume). In the process, they have the opportunity to learn not only the skills and the social organization of the activity at hand but also to become proficient in attentiveness and collaboration.

Helpfulness without being asked is not common at home among children from highly schooled European American communities. Instead, children are often paid to do chores, in contractual arrangements, reflecting their community’s valuing of learning responsibility for individual assignments in which labour is exchanged for money (or gold stars on a chore chart, or privileges such as watching TV).

Such cultural differences in helping without being asked appeared in a study of pairs of siblings in California who had opportunities to help an instructor who visited their homes to show them how to make solar prints (see https://videohall.com/p/1318). On 15 scripted occasions while the instructor was demonstrating how to make photographic prints of small objects, something happened that the children could help with. For example, at a certain point, the instructor ‘accidentally’ tipped over a container containing the small objects needed for the activity. The instructor never asked for help or cued the children in any way. She simply put the objects back into the container while continuing her conversation with the children, without calling any attention to the spill, giving the children 15 opportunities to help spontaneously, without being asked.

The children from Mexican immigrant families with likely heritage from Indigenous communities (and limited Western schooling) more often spontaneously helped the instructor than did European American children from highly schooled families. The difference between the two backgrounds was especially strong if the event involved helping the instructor manage the overall activity, rather than helping opportunities that had more direct benefit to the children’s projects.

López-Fraire and colleagues also asked the children’s mothers about the children’s helpfulness at home. The Mexican Indigenous-heritage mothers reported that their children routinely helped without being asked, in line with prior studies (e.g., Alcalá et al., Citation2014; Coppens et al., Citation2016; Mejia-Arauz et al., Citation2015). In contrast, the European American highly schooled mothers reported that their children seldom did so; the mothers usually assigned chores to the children, accompanied by rewards or punishment for completion or its lack, and many struggles.

Thus, the Mexican Indigenous-heritage children helped in a way that corresponds with the cultural value being acomedido/a, showing alertness to what was happening and collaborative contributions to managing the activity. Indeed, all of their mothers referenced the importance of helping without being asked, describing this cultural value. (Most of the highly schooled European American mothers liked the idea of children helping without being asked, but some of them claimed that this would be nice but is unrealistic.) The Mexican-heritage mothers’ emphasis on helping without being asked occurred not only in Mexican immigrant families with Indigenous-heritage backgrounds (and limited Western schooling) but also in Mexican-heritage families with extensive Western schooling.

However, the children from Mexican-heritage families with extensive Western schooling acted differently in the two situations. They spontaneously helped at home, like the Indigenous-heritage Mexican children. But with the instructor, they seldom helped without being asked, like the European American children from families with extensive schooling. These children, with family experience of both communities’ ways, seemed to distinguish the community-held values for being acomedidos/as at home and the community-held values for not helping without being asked in an instructional situation (which is a widespread expectation in Western schooling, Adair & Sánchez-Suzuki Colegrove, Citation2021).

The children with family experience of both Indigenous-heritage and Western school practices reflected the value systems of each community regarding children’s inclusion as contributors (Facet 1). They were no doubt influenced by implicit and explicit indications of each community’s expectations of when and whether to pitch in as contributors to ongoing activities (Facet 5). Their flexibility in approaches gives evidence of their agency and skill in navigating distinct cultural ecologies, using varied repertoires of practice (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, Citation2003). Their flexibility illustrates Beatrice Whiting’s point that ‘The standing rules for these settings do not prescribe the same type of social interaction’ (Citation1980, p. 104). The children’s adaptation to use different approaches across settings with distinct cultural ‘standing rules’ also shows one way that cultural changes and continuities may occur across generations.

A contrasting learning paradigm: Assembly-Line Instruction

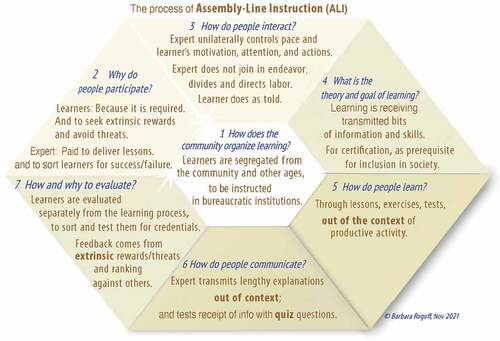

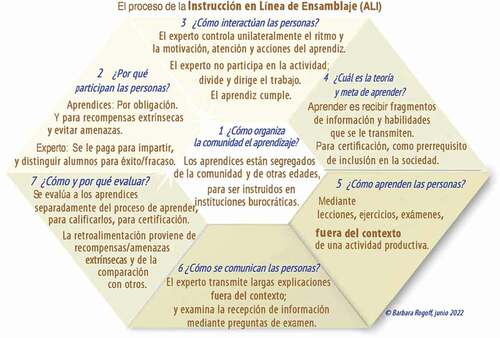

It is instructive to examine how LOPI contrasts with a way of learning that many people with extensive experience in Western schooling take for granted as being the way that people learn. Rogoff and colleagues have referred to this as Assembly-Line Instruction (ALI; e.g., Rogoff, Citation2014, see ). This paradigm is well known in the social sciences and in education by various names, such as the banking model or the factory model. It is often a central format of Western schooling — but not always (see Rogoff et al., Citation2001).

Figure 2. The seven facets of the Assembly-Line Instruction prism (revised 2021) together describe a way of learning that is frequently used in many Western schools and in families with extensive schooling.

Note that although we focus on two paradigms — LOPI and ALI — they are only two of many ways of organizing learning. The seven numbered questions that head the facets of the LOPI and ALI prisms could productively be used to develop articulated descriptions of other paradigms that organize learning. (For example, see the prism describing guided repetition in Rogoff et al., Citation2007.) The answers to the seven questions are what distinguish and describe these learning paradigms.

It is important to recognize that people everywhere engage in more than one way of learning, especially in distinct contexts — as was seen in López-Fraire et al.’s study with the children whose families had experience in both Indigenous Mexican and Western schooling values and practices. People can and do learn to use more than one way of organizing learning, in expanded cultural repertoires of practice (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, Citation2003; Rogoff, Citation2003). Knowing how to engage in both ALI and LOPI (and other ways of organizing learning) is a sophisticated form of adaptive expertise (Rogoff, Citation2003) that supports flexible, skilled participation in distinct settings.

The central role of community in assembly-line instruction

As in LOPI, the community has an important role to play in Assembly-Line Instruction, but the role itself contrasts markedly with the role of the community in LOPI. Facet 1 of the Assembly-Line Instruction model specifies that the community segregates children away from productive activities, in specialized settings apart from most of the everyday activities of adults in the community. Reflecting this emphasis on segregation, many North American parents treated their children’s presence at home as a ‘disruption to daily living’ when schools closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, rather than treating children’s presence as a normal and desirable aspect of family and community life (Landry, Citation2020).

The segregation that is central to the community organization of learning in ALI occurs in numerous ways. For example, children’s presence is forbidden or discouraged in many adult workplaces and social events, by the workplaces, by custom, and by the efforts of many international intervention organizations that espouse that separating children from the life of their family and community will give them a better life. In many nations, laws exclude children from labour and require them to attend school, which prototypically occurs in a setting apart from other community events and may prohibit most community members (even parents sometimes) from entering. School district and state policies often ‘batch’ children by age groups as narrow as 1–2 year spans, restricting children’s involvement with children of different ages (Anderson-Levitt, Citation1996; Bang et al., Citation2016; Chudakoff, Citation1989; Morelli et al., Citation2003; Rogoff, Citation2003). These practices and related values are often codified by the community’s laws and regulations of their governments and institutions.

Although ALI is common in Western schooling worldwide, it is not inherent to schooling. (See Sánchez-Suzuki Colegrove, Citation2022, this volume.) Some school settings are organized in ways that are very similar to LOPI, with students having the opportunity to observe others and pitch in to collaborate on real endeavours that are valued in the school community or the broader community. In Learning Together: Children and Adults in a School Community (2001), Rogoff, Goodman Turkanis and Bartlett and their colleagues analysed how kindergarten through sixth grade children were involved with adults in designing collaborative activities in which they learned academic material embedded in a shared purpose to benefit the classroom or broader community. This was based in a community involving the children, parents, and teachers of the whole school, and sometimes an administrator, collaborating over years in the formation of policies and traditions; it is difficult to recreate in solitary classrooms (Clokey-Till et al., Citation2001). The expectations of the community are an important guide to the learning of the children as well as to the learning of their parents and teachers.

In universities, ways of learning that resemble LOPI can often be found in laboratories where students join with established researchers to help move research projects forward. The students have opportunities to learn by observing and pitching in with other students, postdocs and professors, with the purpose of contributing to the lab and to the larger research community. Such multigenerational lab situations are organized in line with traditions and policies of community institutions — e.g., universities stipulating student credit hours, working conditions, work calendars, and policies of institutional review boards — again highlighting the role of community.

However, few university students have the opportunity to learn through LOPI as contributors in labs. Most universities organize instruction through a community-wide codified curriculum that relies on professors delivering information in lectures and students receiving it (ALI’s Facet 5). Both students and professors are required to comply with bureaucratic rules, national policies and community norms focusing heavily on grades and points for assessment (Rogoff, Citation2001).

The role of community in ALI connects with ways of learning (Facet 5) in ALI

Community segregation and bureaucratization of children’s learning — described in Facet 1 of Assembly-Line Instruction — appears in the other related facets. For example, Facet 5 of ALI specifies that learning occurs out of the context of productive activity, given that children are often excluded from such settings (Facet 1). As a result, the primary way of learning in Assembly-Line Instruction involves lessons, exercises and tests separate from situations in which information and skills are to be (eventually) applied. Instead of allowing and encouraging children to pitch in to help in ongoing events, the community organizes structured lessons in small steps, often according to district or state plans. These lessons provide children with what Fortes, Citation1938/1970, pp. 37–38) called ‘factitious’ activities, which do not in themselves have value but which provide practice with bits of activity extracted from the context of their use.

In ALI, the lessons and tests are organized in line with community-wide policies and restrictions. Instructors are expected to fit their instruction with a larger curriculum of the school system or of the nation, which specifies the order of what is learned when. For example, one school superintendent in Salt Lake City ordered all teachers across the city’s schools to instruct students on the same page of the same prescribed textbook on the same day (Rogoff et al., Citation2001).

The textbooks themselves are designed and vetted across a broad community in the United States, with expectations regarding coverage, order of topics (and avoidance of some topics), ways of encouraging student understanding and ways of assessing it. Children’s learning opportunities in public schools are organized by highly politicized community processes of textbook and technology production, adoption and purchase. In many schools worldwide, large corporations and corporate foundations play an outsize role, for example, in lobbying for the use of specific educational technologies (Moeller, Citation2020). Educational technologies themselves are structured in ways that promote some ways of learning and constrain others.

Besides Facets 1 and 5, other facets of ALI reflect the importance of how the community arranges children’s opportunities to learn.

The role of community in why people take part (Facet 2) in ALI

Facet 2 (of both ALI and LOPI) addresses the question of why individuals become and stay involved in the activities of their communities. In LOPI, learning with the purpose of contributing to the group is key. But often in Assembly-Line Instruction, children do not have a compelling purpose to engage in the exercises and lessons. Students often do not see any purpose in lessons and complain that the information is useless. With children excluded from contributing to actual productive activities of the community, there is often no way for them to see how the learning activities matter or make sense in the larger picture. Presenting a bit of information or repeating a skill out of context does not lend itself to understanding why this information or skill is worth knowing or knowing how to do. In ALI, the break-up of processes into small, isolated steps controlled by an expert may not make sense (Paradise et al., Citation2014).

The community organization of learning in ALI is based on bureaucratic efficiencies, in which children are expected to comply with the efforts of adults to transmit bits of information and skill without necessarily knowing (or even having) a broader purpose. In Facet 2 of ALI, teachers (and parents) are treated as responsible for motivating children to take part in lessons, with adults attempting to control learners’ behaviour through rewards such as grades or privileges or punishment such as grades or removal of privileges.

This motivational system in ALI is often used in homes in many communities of highly schooled families, as well as in many schools. Parents in such communities often use ‘allowances’ and other forms of reward and punishment to motivate children’s compliance with individual chore assignments (Coppens & Alcalá, Citation2015). The pressure that immigrant Mexican children who do not get an allowance often exert on their parents to do as their classmates’ parents in their new US community do — to give an allowance — illustrates the power of community expectations in people’s reasons to become and stay involved in the activities of their communities (Facet 2) in communities organized around ALI.

In LOPI, learning with shared purpose is key to why people participate in learning events of their community (Facet 2)

In LOPI, the community’s inclusion of people of all ages as contributors (Facet 1) facilitates children’s opportunities to see the overall goal underlying aspects of the activity in which they are involved. This fosters learning with purpose, indeed, shared purpose, to be of use and to help accomplish something with the group (Facet 2; see https://videohall.com/p/1910). An important aspect of why people do their part in LOPI is to be in relation with the group, in cohesive alignment with other people and with the direction of the group. Pelletier refers to this as having a sense of community consciousness (Pelletier, Citation1969; see also Elliott & Meixi, Citation2022, this volume); in Mexican Spanish, this is well expressed by the term convivir.

In interviews about children pitching in to help with work around the house, Mexican and Mexican-heritage mothers revealed an important community-based theory of learning that relies on individual agency and autonomy: that learning is born from the heart. They explained that it is important for mothers not to tell children what to do or obligate them to pitch in, because this would stifle the development of children’s own initiative, which is key to both learning and to being part of the collaborating group (Alcalá et al., Citation2014; Coppens et al., Citation2016, Citation2020). So the mothers do not simply let children be part of things; rather, they use a community-wide theory of learning that underlines the importance of non-intervention in children’s agency (Cervera-Montejano, Citation2022, this issue; Scollon & Scollon, Citation1981).

These mothers purposely include even the youngest children, so that toddlers see that their contributions are valued and begin to learn what to do — and the mothers avoid obliging children to help at home, to support the children in learning collaborative initiative (Cervera-Montejano, Citation2022, this issue; Coppens et al., Citation2020; Coppens & Rogoff, Citation2021; Rogoff, Alcalá et al., Citation2014). This apparently matters more than efficiently getting the work done, as the children’s efforts often need others’ guidance and correction.

For example, a Mexican-heritage California mother interviewed by Coppens and Rogoff (Citation2021) smiled proudly as she recounted that her two-year-old helps out and is developing community-mindedness: ‘Well, my son wants to learn, wants to … already enter into the family … . Like “we ought to all do this for us”. It is something good. Like, to enter the circle of “Let’s all do this all together”. I think it’s good’. (https://videohall.com/p/1676). Her emphasis was not so much on getting tasks done, nor on the two-year-old learning task-related skills. Rather, she underlined the importance of the child learning to enter the family circle, as a developmental goal to become a voluntarily contributing member of the group, with shared purpose and a sense of being part of something larger.

This contrasts with an emphasis on efficiency, which was paramount for many of the middle-class mothers who avoided letting their children help out at age 2–3 years. For example, a European American California mother smilingly complained, ‘It’s hard for me to get stuff done when they’re awake and around and, you know, and so I do a lot of the stuff when he’s, like, napping’. (https://videohall.com/p/1676). The priority was on getting the chores done efficiently, in contrast with the priority of the Mexican-heritage mothers who included toddlers in household work to help the children develop a collaborative attitude, to learn how to be a part of the larger group and endeavour.

We are often asked how communities that emphasize LOPI deal with children who are not motivated to take part. Paradise (Citation1998) has argued that in communities emphasizing LOPI, it is very rare for children not to want to be a part of things. Given that it is a community expectation and practice for everyone to pitch in, helping out is just ‘normal’, it is what everyone does (Alcalá et al., Citation2021; Coppens et al., Citation2014; Gaskins, Citation2020). If everyone around you is helping out and you are accorded the autonomy to decide to help or not, helpfulness does not derive from adult control, as is often the case in middle-class family life. LOPI is based on everybody voluntarily pitching in to the larger endeavour.

Of course there are times when people don’t do as they are expected to. If it is a young child in a system based in LOPI, this may be simply allowed, or attempts are made to persuade the small child. The child’s willingness is valued, in order to give them the respect for their autonomy that is seen as necessary for learning to collaborate (Gaskins, Citation2020; Mosier & Rogoff, Citation2003; Rogoff, Citation2003).

As our colleague Margarita Martínez-Pérez explained in a class about Indigenous ways of learning (November 2012), learning to be collaborative is a whole developmental process in her Mexican Indigenous community. The honouring of autonomy is regarded as contributing to young children learning how to align themselves with the direction of the group. If, by the age of eight or ten, a child has not learned to help with something that everyone is expected to know or do, adults may correct them, in the effort to make them aware of the importance of learning what is at hand. A correction may take the form of a scolding, for example, ‘Why can’t you be acomedida/o like your cousin?’ when a child has not helped out. Or a correction may be very subtle and lightened with laughter or instructional ribbing (Martínez-Pérez, Citation2022, this volume; Silva & Rogoff, Citation2020).

The developmental process in communities where LOPI is prevalent, in many Indigenous communities of the Americas, is thus based in individual autonomy and agency together with alignment with group goals. In contrast, it is common in highly schooled families for parents to try to enforce the same rules with toddlers as with older children (Mosier & Rogoff, Citation2003). Likewise, parents in highly schooled communities often begin to offer 2–3-year-olds incentives on a contractual basis to try to control even very young children’s involvement in individual chores (Coppens et al., Citation2016; Coppens & Rogoff, Citation2021). This connects with the adult control of children’s motivation, through contractual incentives and punishment, that characterizes Facet 2 of ALI.

Of course, in any Indigenous community or in any middle-class community, there is individual and situational variability. The LOPI prism attempts to describe a valued framework, with guiding principles. In line with this framework, research shows that in many situations, children and families in many Indigenous communities of the Americas are more likely to act in accord with the principles of the LOPI model than are children and families in many highly schooled communities.

LOPI’s collaborative community emphasis shows up in how groups collaborate (Facet 3)

The invitation and expectation for everyone to pitch in, in Facet 1 of LOPI, is echoed in processes of working together collaboratively (Facet 3). Where Facet 1 focuses on community-wide values and practices in the collaborative organization of the community, Facet 3 focuses on how individuals engage with each other collaboratively in groups. Facets 1 and 3 are companion angles on collaboration, dealing with community organization and the organization of group interaction, respectively.

The relation of LOPI’s community organization (Facet 1) and LOPI’s interpersonal forms of engagement (Facet 3) are clear in the community organization of collaborative decision-making, communal work (e.g., tequio), and economies built on reciprocity that are traditional and remain common in many Indigenous communities of the Americas (Flores et al., Citation2015; Walsh-Dilley, Citation2017). For example, in a Tzeltal community in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, ‘Consensus is the heart of their form of local governance’ (p. 68, Speed, Citation2006). Almost all of the land is communally owned, and its use is distributed to individual comuneros. In turn, the comuneros have the responsibility to take part in the community decision-making organization and to participate in the process of reaching consensus, for almost all aspects of local political life. Consensus is at one and the same time the community organization (Facet 1) and the interpersonal process (Facet 3). The importance of consensus in this community’s affairs was underscored when, for the first time in more than two centuries, a small faction broke from the community consensus. The assembly of comuneros decided that the rights to use communal land should be removed from the families that were not living up to the related responsibility of participation in community decisions.

Facet 3 specifies that everyone in a group helps out, fluidly blending their ideas in a shared pace and with flexible roles as one person or another sees what to do next. This fluid collaboration involves everyone contributing to the shared endeavour in smooth coordination based in alignment of individuals’ efforts with the direction of the group, as well as individual agency in moving the shared endeavour forward. This fluid form of collaboration does not mean that everyone contributes equally; the people with greater skill, experience and sense of purpose in the activity are more likely to lead — or rather, to be followed (Ruth Paradise, personal communication, February 2019; Rosado-May et al., Citation2020).

An example of community-wide practices in support of this expectation of flexible interpersonal collaboration came to light in interviews about household work. Mexican Indigenous-heritage mothers and children reported that often siblings and mother coordinate together fluently and willingly in co-labor-ation (Alcalá et al., Citation2014; Mejia-Arauz et al., Citation2015). Mothers often mentioned that on Saturday mornings, someone would turn on the radio and everyone would get to work cleaning up the house together, and then they would go together on a visit or an outing. When BR reports on this practice in talks, the Mexican-heritage audience members often comment, with some surprise, that their family did that but that they never stopped to think about it. This is an example of a community-wide practice for group interaction that is based in implicitly held community values and routines.

Note the contrast with Facet 3 of ALI, where a teacher/parent/expert is in charge and tells others what to do, without entering into the same activity with the children/learners. Instead of a collaborative relation in which everyone provides initiative in coordinating towards a shared goal, the adult’s role in ALI is to control the involvement of others, dividing up the task into separate chores and managing other people. The important contrast between having to do assigned individual chores in ALI versus helping to accomplish the group’s goal in LOPI is based in the role of control in ALI versus collaboration in LOPI.

In LOPI, anyone may take initiative in leading the group forward, if they see what to do. This could involve children leading the way, like the situation that many adults experience when learning how to use a new computer program or device. Anyone who has skill and clarity for moving towards the shared goals can lead the way. With increasing involvement and skill, children are entrusted with more and trusted to do things their own way, and elders will be willing to learn from them (Gloriana López, personal communication, June 2021). To be clear (because people unfamiliar with LOPI often assume otherwise), LOPI does not involve the form of hierarchy with a boss and underlings — it involves flexible roles and initiative and influence from everyone. This is what Rogoff (Citation2003) called ‘interdependence with autonomy’.

The contrast between control and collaboration shows up especially in Facets 1, 2 and 3 of the ALI and LOPI prisms. LOPI Facet 1 emphasizes the integration of all ages in the community’s endeavours; Facet 2 emphasizes individual agency and interest in the context of alignment with others; and Facet 3 emphasizes the process of side-by-side coordination of individuals taking initiative and collaborating as an ensemble. In ALI, each of these facets emphasizes control — by community institutions and by adults or experts.

Collaboration in the LOPI model, with individuals taking initiative in aligning with the group direction, is based in a very different view of the relation of individuals and groups than is common in developmental scholarship on the development of collaboration. It is usual in developmental psychology to assume that working together is basically negotiation between individuals who are inherently separate (Mejía-Arauz et al., Citation2018). It is thus assumed that individuals have to work to take into account each other’s private intentions, jockeying back and forth from one individual to another to compromise. Instead, in LOPI collaboration, alignment and relationality in the group do not involve a battle between individual perspectives but movement together in the shared direction, for the benefit of all. As Diego Carrandi has put it (personal communication, August 2017), LOPI collaboration is like musicians improvising music in an ensemble, in a shared endeavour relying on individual initiative/agency.

The community is key in the theory of learning and what learning is for (Facet 4) in LOPI

The theory and goal of learning in LOPI emphasizes the process of becoming more able to contribute to the community. In LOPI Facet 4, this process of becoming is a theory of learning as transformation of participation (Rogoff, Citation1998). It is a process of growth, based in mutuality of the individual and the rest of the world. (This is unlike ALI, where learning is seen as a process of an individual receiving and storing transmitted information and skills, separate from the world; see Rogoff, Citation2003.)

The process involved in LOPI Facet 4 includes developing skills and values that are recognized in the community as well as innovating new solutions to continually changing circumstances and to longstanding community efforts (Rivero & Gutiérrez, Citation2022, this issue; Rosado-May et al., Citation2020). In LOPI, individual initiative/agency is based in the shared effort to benefit the larger community, which of course includes benefitting oneself, because the individual is part of the community and the community is built on generations of individuals’ actions.

The process of learning in LOPI is viewed as people transforming their participation in the process of contributing to the valued activities of the community (Facet 4). Such learning relies on the community’s inclusion of children, engaging in the actual processes that matter in the community (connecting with Facets 1 and 2; see https://videohall.com/p/1910). By being included in the wholeness of real activities of the community, learners have the opportunity to pick up how the part they are contributing fits with the overall goal of the endeavour, unlike in ALI. For example, a Mayan girl might be asked to fetch more yarn or the scissors for her mother’s weaving; in the process of carrying out these steps, she can see how her mother uses the scissors and the new yarn to continue the weaving. She can see how her little contribution fits in the overall activity, which would be a pretty meaningless step if she weren’t embedded in the wholeness of the activity. If learners are included in whole processes, they can see where the process is going and how it unfolds. In the process of helping out, they have a chance to see how the steps fit together, even in longterm endeavours such as preparing over months for a ceremony (as in Cervera-Montejano, Citation2022, this volume).

Facet 4 of LOPI contrasts with Facet 4 of Assembly-Line Instruction, where learning is regarded as individuals storing information and skills that are ‘transmitted’ to them by experts outside the context of use. The learner’s role in ALI is to allow experts to control their efforts, in the hope that some information and skill might enter their heads. In ALI, the individual is seen as bounded off from other individuals and the world, so the expert tries to get the information and skills ‘inside’ the learner, ‘delivering’ the curriculum. In contrast, in LOPI, learners are already inside the process of using the information and skills, while they engage in ongoing, valued activities.

Related to the separation of individuals from the community in ALI, individuals’ learning is treated as a way for some individuals to earn the credentials that eventually allow them a role in the community as adults. The credentials are controlled by the community’s institutions (such as schools, universities, testing, and licencing bureaucracies) to determine which learners are accepted into the next level of training, and after many years, into contributing to the community in jobs and professions. (However, even in jobs and professions such as physician, professor, teacher, plumber and accountant, much of an individual’s contributions do not come from the bits of information gained in years of ALI but from learning while carrying out the job in a form of apprenticeship or on the job.)

In LOPI, even young children are already contributors, with the opportunity to learn in the process of becoming more capable of helping with the real endeavours in which they are included. LOPI Facet 4 specifies that young children’s efforts to contribute, even when their efforts require correction, are important to the community’s continuity across generations as well as to the community’s adaptation to changing times (e.g., Wilbert, Citation1979).

In many Indigenous communities of the Americas, individuals’ learning is embedded in mutual contribution to the future of the community as well as respect for the contributions of others, including ancestors and the more-than-human world. Individuals contribute within an ecology in which all participants play their part, whether humans, other creatures or the rest of the world. Elliott and Meixi (Citation2022, this volume, p. 569) describe this in terms of the individual being ‘deeply embedded within and emergent from a vast system of human and greater-than-human relations’ (see also Alonqueo et al., Citation2022, this volume; Bang et al., Citation2016; García, Citation2015; Leonard, Citation2021; Lorente Fernández, Citation2015; Remorini, Citation2015; Viveiros de Castro, Citation2015). In contrast, in ALI, rather than transforming one’s participation in the process of collaborative, mutual participation, the individual is considered separate and the goal is to control other people and the more-than-human world.

What about the role of community in the means of communication and evaluation in LOPI (Facets 6 and 7)?

Like the other facets, Facets 6 and 7 of LOPI also rely on the community being organized inclusively, with everyone involved and learning as they observe and contribute to shared endeavours. The forms of communication comprising LOPI Facet 6 are based in inclusion in shared family and community endeavours. Within this shared context, people can coordinate their efforts and build their relations using multiple channels. They use talk judiciously, in the service of the ongoing efforts and relations. For example, in the learning of traditional midwives in the Yucatán, communication in the face of a challenging obstetric case includes discussion of prior related cases, building hypotheses via talk that combines the experience of those present, in the service of addressing the current situation (Jordan, Citation1989). Verbal explanations are purposeful, in the context of shared endeavours. (Note that storytelling is also an important practice that commonly serves as a form of guidance, in Facet 5; Marin & Bang, Citation2018; Tsethlikai & Rogoff, Citation2013. Storytelling creates shared context in the narrative itself and in the involvement of listeners in the telling.)

This contrasts with communication in ALI, which is mostly carried through extensive explanation outside the context of applying the information, sometimes accompanied by quizzes. This is exemplified by the lessons that Western medical personnel used in attempting to ‘train’ the Yucatec traditional midwives — lengthy lectures and quizzes on vocabulary. Jordan (Citation1989) noted that this taught the midwives how to talk with Western medical personnel, although it did not connect with the midwives’ actual medical practice or medical knowledge. In ALI, where explanation is outside the context of applying the information, explanation is limited to being about the target activity, disconnected from using the information, rather than being supported by the multidimensional context of being within the target activity where talk is in the service of using the practices and knowledge in the context of shared activity.

The shared context of LOPI supports the use of articulate nonverbal conversation. While people engage in a shared endeavour, their actions and the ongoing events are part of the communicative process and can be referred to efficiently through nonverbal means. Ideas and events can be discussed through conversation that is largely nonverbal, as people comment, question, and hone their approaches to the ongoing endeavour through multiple rounds of communication based in gesture, postural change, gaze and touch, in addition to talk, within shared events (Alonqueo et al., Citation2022, this volume; Marin, Citation2020; Mejía-Arauz et al., Citation2012; Rogoff et al., Citation1993; Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2015). The availability of the ongoing shared endeavour as a referent, as the substrate of the verbal and nonverbal conversation, relies on co-presence in the ongoing activities of the community (Facet 1).

Facet 7 addresses the question of how and why to evaluate. In Facet 7 of ALI, evaluation centres on examining the knowledge and skills of individual learners and ranking them against each other in a competition that determines which learners receive opportunities and which learners are shunted aside. ALI’s external reports of relative ranking against other people are sometimes accompanied by tokens unrelated to the endeavour itself, such as grades or points or gold stars. This ranking system is a highly structured activity of the communities that employ ALI to sort people, to determine which ones receive a credential that allows them to move to the next stage in the ranking system or gives some of them priority for desirable occupations while removing others from the opportunity system or deflects them to less desirable or even punitive life courses. As is commonly known, this ranking system is closely tied to the competitive economic system that organizes societies by social class.

In contrast, LOPI’s Facet 7 focuses on evaluation of the contribution rather than the individual and occurs during the endeavour itself (unlike in ALI, where testing is separated from instructional moments). More experienced participants evaluate both how newcomers are proceeding in their efforts to contribute and the effectiveness of the supports that help the less experienced participants contribute in a worthwhile way. The purpose of LOPI evaluation is to support all participants in making valuable contributions.

In LOPI, while making contributions, learners can see how successful their efforts are by noticing whether their contribution is corrected by others or accepted as an adequate contribution. For example, a child whose efforts to make tortillas end up in the family dinner rather than being fed to the chickens has powerful information about their own progress in making tortillas. Or the graduate student whose draft of a paragraph gets incorporated in a collaborative manuscript for publication can see the success of their efforts. Evaluation in LOPI is based in the community emphasis on co-presence and mutual contribution of all.

Variation among and within cultural communities in prevalence of LOPI

There seems to us to be sufficient evidence, at this point, to hazard the statement that many Indigenous communities of the Americas share a way of organizing children’s learning — Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours — that is more common among them than in many middle-class, highly schooled communities. We do not generalize to all Indigenous communities of the Americas (much less all Indigenous communities of the world), nor to all circumstances and events in communities where this way of learning seems to be common.

However, it is important to note that people everywhere employ this way of learning to some extent. For example, as Rogoff (Citation2014) pointed out, infants and toddlers universally learn their first language through LOPI, by being immersed in families and communities that use a particular language. They observe and listen in to make sense of events, and they try it out, pitching in, to communicate in order to accomplish things. (See also Henne-Ochoa, Citation2022, this volume.) Even in communities where parents also play language games with toddlers, like known-answer quizzing and running commentary (Rogoff et al., Citation1993), the process of being involved, observing and trying to contribute is key to the impressive learning of our first languages.

The prevalent use of LOPI may not be limited to Indigenous communities of the Americas. LOPI may be a common way of learning on other continents than the Americas (see Corona et al., Citation2015). This is an empirical question that requires deep knowledge of ways of learning that are common in other communities around the world, through ethnographic research, autobiographies and lived experience. We believe that LOPI may be common in Indigenous communities of several other regions — with a guess that LOPI may be prevalent in Indigenous communities of Australia and New Zealand and in gathering and hunting communities in many regions (Lew-Levy et al., Citation2019).

But we also believe that LOPI is likely not to be prevalent in Indigenous communities of some regions, especially in groups where a rigid hierarchy of boss-to-underlings is prioritized. If a community’s valued and common way of learning prioritizes a rigid hierarchy of boss to underlings, this way of learning would not fit with Facet 3 of LOPI (e.g., see Medaets, Citation2016). A way of learning that does not fit with all seven features of the LOPI prism would not fit the multifaceted description of LOPI.

Nonetheless, such a way of learning would be interesting in its own right, worthy of investigation. We hope that other scholars address the question of whether LOPI is a common way of organizing learning elsewhere, beyond Indigenous communities of the Americas, and that others delineate other ways of learning that may share some features with LOPI but differ in other features.

It is also important to note that although LOPI appears to be especially common in many Indigenous and Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas, this way of learning is not the only way of learning in such communities. LOPI is, rather, commonly held as one model — implicit or explicit — of how children, families and communities should arrange for learning.

Although dozens of research studies and autobiographies indicate that LOPI is more common in Indigenous and Indigenous-heritage communities of the Americas than in highly schooled European American families and communities, as anywhere, life is complex. Everyday life includes borrowings and impositions from other cultural traditions over centuries, including Western schooling. In addition to challenges (such as alcohol) that make it difficult for people to do what they believe should be done, it is advantageous to know how to engage in more than one way of organizing learning, not only for people in Indigenous communities of the Americas but also for people in communities where extensive Western schooling has been a practice for a century or more.

Why try to describe LOPI?

People who are relatively unfamiliar with LOPI may find it difficult to understand the premises on which LOPI is based. (This was BR’s experience when she was first immersed in San Pedro life; Rogoff, Citation2012.) A primary purpose of the LOPI prism is to aid those who are less familiar with LOPI to understand its features and how they together compose this learning paradigm.

Another purpose of the LOPI prism is to aid those for whom LOPI is common sense, in justifying the use of this way of learning, in the face of bureaucracies that are based on contrasting models of learning such as ALI (see Henne-Ochoa, Citation2022, this volume). In particular, our description of LOPI would likely be common sense to many Indigenous American scholars who have described aspects of the LOPI way of learning in delineating Indigenous Knowledge Systems (see Rosado-May et al., Citation2020; Urrieta, Citation2015). As a Native American scholar kindly said to BR after her plenary address at a recent conference of child development researchers in Native American communities, ‘Well, to us, what you explained about the LOPI way of learning is … well, duh!’ Another Native American scholar chimed in, ‘Yes, of course. And we can use the LOPI prism with government agencies to explain and justify what we do’.

One of the most compelling forms of verification of the LOPI prism’s articulation of this way of learning is such ‘Yes, of course’ responses of colleagues and friends from Native North American and other Indigenous communities in other parts of the Americas. We hope that the latest version of the LOPI prism, presented here, deepens understanding of the key features of this way of learning, and especially of the crucial role of how communities organize the lives of children as contributors in family and community life.

El papel clave de la comunidad en Aprender por medio de Observar y Acomedirse en las actividades de la familia y la comunidad

Este artículo se centra en las contribuciones de las comunidades a un tipo de aprendizaje que parece especialmente común (aunque no inevitable) en muchas comunidades indígenas de las Américas y entre gente con herencia en tales comunidades: el Aprender por medio de Observar y Acomedirse en actividades de la familia y la comunidad (Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavours; Rogoff, Citation2014; Rogoff, Aceves-Azuara et al., Citation2017). Comparamos esto brevemente con las contribuciones de la comunidad a un tipo de aprendizaje que es común (pero no inevitable) en las escuelas occidentales — la Instrucción en Línea de Ensamblaje (Assembly-Line Instruction) — para poner de relieve las distintas contribuciones de la comunidad en estos dos tipos de aprendizaje. A menudo, los investigadores y el público en general consideran el aprendizaje como una actividad de individuos — tanto de las personas que aprenden como de las que les guían en el aprendizaje. Por supuesto, las personas en tanto que individuos forman parte de esta historia, pero con demasiada frecuencia se subestiman las contribuciones de la comunidad en el aprendizaje y en las oportunidades de aprendizaje.

En este capítulo, primero situamos los dos tipos de aprendizaje bajo un enfoque teórico en el que las comunidades y los individuos se consideran aspectos mutuamente constituyentes del proceso de la vida y no entidades separadas. Después discutimos nuestras razones y proceso para crear modelos con los que tratamos de describir las características contrastantes de las dos formas de aprendizaje. Crear los modelos es un proceso en curso — en este artículo presentamos nuevas versiones; la versión anterior del modelo que describe Aprender por medio de Observar y Acomedirse en actividades de la familia y la comunidad fue publicado hace ocho años (Rogoff, Citation2014).

A continuación, nos centramos en la relevancia de las contribuciones de la comunidad en Aprender por medio de Observar y Acomedirse en actividades de la familia y la comunidad (LOPI, por sus siglas en inglés). Contrastamos brevemente las contribuciones de la comunidad en LOPI con el papel central de las contribuciones de la comunidad en el modelo de Instrucción en Línea de Ensamblaje (ALI, por sus siglas en inglés), especialmente en relación con las formas de aprendizaje de las personas y sus razones para participar.