ABSTRACT

Much has been written about policy learning and transfer over the past 20-years. However little of this has examined the role of transfer within authoritarian nations. We propose to start addressing this by examining the movement of the river chief system from its original setting in the city of Wuxi in the Jiangsu Province to Suqian, Nantong, Suzhou and Huzhou, in Zhejiang Province. To do this we looked at two basic patterns of transfer: (1) horizontal transfer from one municipality (or combination of several) to another, and (2) vertical transfer up to and down from the Provincial level. This allowed local agents to act either autonomously in the transfer and learning processes or act under some level of compulsion to engage in the act of transfer. Based on our four case studies we argue that even when transfer involves a high degree of autonomy and translation of the transferred model to the local circumstances, successful outcomes are not guaranteed, just as when agents are forced into transfer a given model to their jurisdiction, there is no guarantee that it will result in policy failure.

Introduction

Governments around the globe are facing difficult problems and decisions in relation to the causes and impacts of climate change. As a result, many have started to examine policies and ideas that have been developed by others (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation1996, Citation2000, Citation2012; Rose, Citation1991; Wolman & Page, Citation2002). Moreover, this appears to be true regardless of whether the originating and borrowing systems are facing the same (or even similar) situations for which the policy is being examined. As a result, it is often the case that using other’s ideas and policies (even those regarded as ‘best practice’) might not be appropriate for application in new contexts; even, as we will show, when modified by local agents attempting to make the policy more appropriate for the endogenous situation (Dolowitz, Citation2017; Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000; Jacoby, Citation2002; Kerber & Eckardt, Citation2005; Marsh & Sharman, Citation2009; Peck, Citation2011; Peck & Theodore, Citation2010).

Part of the reason of the disjuncture between the transfer (of even well-established environmental policies) and the ‘successful’ use of a policy developed elsewhere is due to the complexity of the processes needed to learn, transform and then translate a policy from one context to another (Clarke et al., Citation2015; Dolowitz et al., Citation2020; Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2013; Rose, Citation2005).Footnote1 The basic fact in this is that what is learned, how it is learned, and what is done with and to this information is often overlooked in studies examining policy development. This is particularly true when we turn to the policymaking processes occurring within authoritarian regimes. Here, policy development is often depicted as if the central authority (Beijing in our case) can operate top-down command and control mechanisms, making the movement of policies (particularly those developed internally) a straightforward process. The depiction of a top-down approach to policy development within China is no exception (Li, Citation2021; Parton, Citation2018; For a more nuanced view see: Bai & Liu, Citation2020; Huang & Kim, Citation2019). However, in studying the development and spread of the river chief system across two provinces in China makes it clear that this is far from the case in relation to environmental policies. More specifically, we demonstrate that the transfer of the river chief system within Jiangsu Province and between Jiangsu and Huzhou (in Zhejiang Province), followed a considerably more traditional ‘western’ process of learning and transfer than one might expect; including similar issues of success and failure, miss translations, and even poor use of copying, seen in studies of transfer associated with the movement of policies and ideas between and within democratic nations (whether federal or unitary).

It is often argued that policy transfer is possible, despite differences between political systems, because policymakers face similar challenges, problems, and issues regardless of whether they are embedded in national, subnational, or even international governing structures. And, that this is true regardless of whether the system is authoritarian, democratic or somewhere in between (Prince, Citation2010, Citation2012). As a result, policymakers often find themselves looking at ideas and policies that have been developed elsewhere (Fritsch & Benson, Citation2020). The possibility of finding oneself in contact with information and ideas developed elsewhere has increased over the past 20-years as the globalization of information and spread of technology has made accessing information, ideas and policies little more than a mouse click away (Howlett et al., Citation2009; Stone, Citation1999; Ward, Citation2006) even for policymakers in authoritarian regimes, who are often able to access information that is blocked to the general public. In this, when engaged in policymaking actors are commonly portrayed as ‘rational’ learners, able to control knowledge production and take ownership of their learning (Rose, Citation1993, Citation2005; Simon, Citation1947). However, this is clearly not the case in many circumstances. Rather, learning, particularly when it is involved in the transfer process, is mediated by variables which bound individual and collective rationality. Notably, actors and institutions are bounded by pre-existing ‘mental maps’ (Denzau & North, Citation1994), values (Brown, Citation1995), and perceptions of the socio-political and institutional ‘life spaces’ they inhabit (John-Steiner, Citation1997). As a result, transfer and learning are conditioned by discursive paradigms, ideational circuits, institutional frameworks, and the power structures surrounding the agents involved in the movement and implementation of transferred ideas and policies. Because of this, transfer is seldomly a straightforward, but rather a process of adaptation and change based on the internal and collective constraints of the agents involved and how this shapes their learning processes (Martin & Beaumont, Citation1998; Meseguer, Citation2005; Mukhtarov, Citation2014; Patton, Citation2001; Purcell, Citation1999).

As part of our focus on policy transfer, we want to stress that the purpose of this study is not to narrate the story of the river chief system transfer process in China, but to explore why there are differences in the performance of the policies that are transferred in our four case study jurisdictions and how this appeared to be impacted by the combination of ‘policy learning’ and ‘situational differences’. The goal is to start to break the stereotype of the policy transfer authoritative countries as being a top-down mechanism of control. Rather, diverging from most ‘western’ perceptions, what we will show is that in China, policy transfer can (and does) occur independently of the central administration within and between different levels of local government. More specifically, we show that the transfer of the river chief system between different jurisdictions encompasses both obligatory reform (though not necessarily a directly imposed model) from higher authorities and independent transfers initiated at the discretion of local policymakers, providing a quasi-experimental setting for observing and comparing the success of outcomes under varying levels of learning control and situational conditions.

Background and methodology

In May 2007 an outbreak of cyanobacteria in Lake Taihu led the city of Wuxi (who depended on the lake as its primary source of drinking water) to develop a quick solution. In brief, to respond to the outbreak of cyanobacteria, the Wuxi Municipal Communist Party Committee and Municipal government devised the ‘original’ river chief system. In this arrangement local Party and government leaders concurrently served as ‘river chiefs’ being assigned responsible for water pollution control and water quality protection of water bodies (i.e. Lake Taihu and its feeder rivers) within their jurisdiction. The idea was to use the authority of local Party and government leaders to coordinate and promote the formation of a river and lake management system with clear individual and intuitional responsibilities.Footnote2 Based on this model and the subsequent movement of the river chief idea to other localities, in December 2016, the Chinese central government issued the Opinions on Comprehensively Implementing the River Chief System, marking the point at which the Wuxi policy was officially ‘nationalized’, obliging local officials, that had not already taken up the river chief system, to adopt (even if in an altered form) the Wuxi river chief model.

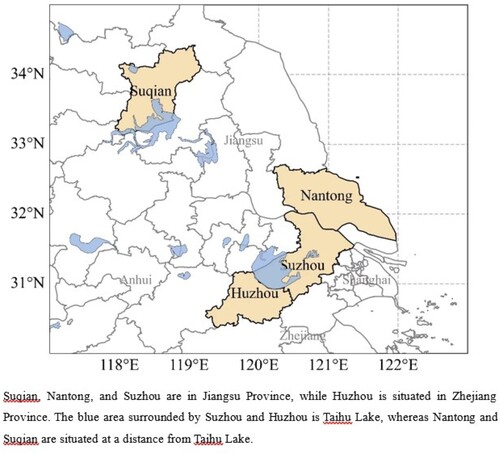

While our study is limited to two Eastern Provinces, we believe that by examining whether a jurisdiction is linked to Taihu Lake or not can act as a criterion for establishing basic ‘situational differences’ between authorities adopting the river chief system early in the transfer process and those waiting until they were ‘forced to act’ by a higher-level jurisdiction. Suzhou and Huzhou were chosen because they have similar administrative designs, populations, and institutional structures.

To balance the equation not only were two similar jurisdictions selected in relation to the development of the river chief system, but two municipalities (Suqian and Nantong) were selected that fell outside the Taihu Lake catchment (see ). Not only did Suqian and Nantong fall outside the Taihu Lake catchment area, but they also exhibited different socioeconomic issues and administrative interactions. More directly in relation to the freedom to engage in an uninhibited or structured transfer process the municipal governments of Suqian and Huzhou engaged in transfer before the release of the policy by a higher-level authority, while the municipal governments of Nantong and Suzho developed their river chief systems after the Provincial policy was officially launched.Footnote3

In relation to the data collected and used for this study we reviewed over 200 documents both primary and secondary consisting of official reports, data from websites and databases, policy texts, media reports, manuals, and official performance evaluation reports. In addition to our documentary analysis that was used to shape where we decided to focus our case studies, we collected a range of primary data between October and November 2020. This consisted of a series of field investigations involving semi-structured interviews with core policymakers in each of our case study municipalities, a subsequent set of questionnaires sent to officials working on the river chief system in Suzhou, Huzhou, Suqian and Nantong. Finally, we compiled a series of observational logs to help verify the data we collected.

More specifically, the interviewees were drawn from the core staff members of the river chief system office in the selected provinces. Interviewees were drawn from all three levels of the river chief system provincial, municipal, and county (city, district). We focused on individuals operating in these offices because the consist of the core organization of the river chief system at the time. We selected to use personnel in the river chief offices because they operationalize the core functions of the river chief system; it is responsible for undertaking the daily work of the river chief system, assign and supervise matters determined by the river chief. The office is also responsible for break down and assign annual work tasks, organize inspections, undertaking river assessments and conducting evaluations of the river chief system work in the next level administrative region. In relation to outreach and public accountability the office is also responsible for the construction of an information platform and carry out publicity on river and lake protection. Organizationally, the office of the River Chief has been established within the water conservancy department and incorporates personnel from the functional departments (such as environmental protection and natural resources) responsible for environmental affairs. In other addition, the offices serve as a liaison between the river chief and these functional departments (it does not replace them).Footnote4

Findings

.

Table 1. Summary of findings.

Suqian

In May 2008, the Suqian Municipal Party Committee and Government Offices issued the Opinions on Establishing a River (Lake) Chief System in Rivers and Lakes under the municipal administrative region. With this document Suqian committed itself to formally transferring the Wuxi River chief system into their municipal administrative region. In this case the transfer occurred before higher level governing institutions ‘required’ the development of a river chief system, making this a traditional example of horizontal transfer from Wuxi to Suqian.

What makes this interesting is not just that local officials told us that they ‘independently sought information from Wuxi’, but that they did this even though they were not facing similar water pollution issues. In fact, the river and lake situation are considerably different in relation to Suqian and Wuxi. Suqian has two major lakes, Hongze and Luoma and over 2000 rivers. As a result, unlike Wuxi, the prominent problem was not cyanobacteria pollution or specific lake management problems, but rather the management of river channel functions and the development and utilization of river channel shorelines (Report on the work of the River Chief System of Suqian, 19 October 2017).

Not surprisingly, considering the learning processes that appear to have been involved in the decision to look to Wuxi for ideas, the Suqian river chief system involved a range of innovations to adapt the model to their needs, including the development of a Water Resources Bureau. Unfortunately, while Suqian actively sought to lean and adapt the Wuxi model they appear to have failed to learn from some of the most important elements that underpinned the Wuxi model; particularly the necessity of bringing together the core staff of water-related departments under the river chief umbrella. This created problems of communication and coordination as noted, unlike Wuxi: ‘The River Chief's Office is only [seen as] a temporary institution, with no permanent staff’. Those who are there are ‘often changed, and some departments arranged it so that [some] people … could not be transferred’. (Interview 22 November 2019)

Second, in relation to the distribution of water control, the original river chief system aimed to establish a sound management system which included a number of protection mechanisms. These were themselves supported by water conservancy departments in the area. Although the policy text of Suqian’s plan (Citation2008) stipulates that local leaders are responsible for river and lake governance, in practice, the governance responsibility has been transferred to the water administrative department which undermined the design (and intent) found in the Wuxi model (Interview 22 November 2019).

Third, the assessment and accountability system, which appears to have improved both performance and leadership in Wuxi, was not replicated in Suqian. In fact, it was specifically drawn to our attention that the river chief system developed in Suqian led to a situation where accountability ‘is not strong enough, [because] the corresponding reward and punishment measures and methods [included in the river chief documentation] cannot be implemented … [leading to a situation where] the process of accountability is often difficult to achieve’ which leads to further implementation problems. (Interview 24 November 2019)

Despite having the time and opportunity to learn and adapt the system to their individual situation, according to the annual river management assessment Suqian ranks in the bottom 20% in terms of fund implementation, river cleaning quality and inspection implementation due to issues such as cognitive bias, organizational weakness, and ineffective implementation (Jiangsu Provincial Department of Water Resources and the Department of Finance, Citation2016). As such, it appears that even when agents have time and are free to learn and adapt a policy to the local environment, there is no guarantee that what is finally created will be able successful.

Nantong

Based on the Wuxi and Suqian models the river chief system began to spread to other municipalities and provinces in eastern China. Early in this the Jiangsu Provincial Government decided to make the river chief system official policy across the province. As a result, in January 2014, the Nantong Municipal Government issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Work of River Chief System in Regional River Management. Contextually, like Suqian, the difficulty the Nantong government faced was one of watershed governance of its river systems rather than major pollution and bacterial outbreaks.Footnote5 Despite the similarity to Suqian, Nantong chose to stick to the provincial governments ‘recommendations’, which were closely based on the Wuxi model (Citation2012; Nantong Municipal Government Office, Citation2014; Wuxi Municipal Government Office, Citation2008). As a result, the transferred policy is closer to a copy of the Wuxi model than the potentially more contextually appropriate Suqian model.

As a result of the degree to which Wuxi’s model was replicated, despite being an essentially lake-based model, according to the 2014 Jiangsu Province backbone river management and protection performance evaluation report (Nanjing Great Wall Land Real Estate Assets Appraisal Cost Appraisal Office, Citation2015), the quality of river cleaning was lower than the national average. This negative evaluation was confirmed by field research which found that despite hopes, the river chief system did not achieve the expected outcomes. First, it was discovered that the function of the river chief's office in Nantong was weak.

From the perspective of more than two years of operation, the vast majority of river chiefs are still only in name … They do not take the initiative to inspect, do not actively investigate, do not timely plan and solve the problem in their daily work. The river chief does not play much of an organizing and coordinating role. (Interview 23 September 2019)

Second, even though policymakers had a model to build on, it appears that they used their powers to alter the model offered by the Provincial government in ways that led to less effective outcomes. Specifically, we found that the Nantong model was deliberately designed to not integrate all the corresponding responsibilities of the river chief found in Wuxi and the provincial policy. As a result, Nantong found itself facing serious implementation issues. Or as one interviewee noted: ‘For the departmental assessment, there is no higher level of institutions and technical forces to implement it, and it is difficult to formulate appropriate measures to reward and punish administrative leaders at all levels for the performance assessment of the river chief’ (Interview 23 September 2019). As a result of following a model designed for Lake maintenance rather than river design and maintenance and removing some of the core functionality that was recommended in the Provincial guidance, Nantong’s river chief system that has to date proven to be poorly performing.

Suzhou

In January 2014, Suzhou issued the Implementation Opinions on Strengthening the ‘River Chief System’ of the City's River Management. From the perspective of time, it was issued after that of the Provincial government acted, which means that the transfer was carried out under the directive of the superior administration, reducing the opportunities for learning and adaptation seen in our previous case. However, unlike Nantong which was operating under the ‘recommendations’ of a superior administration, Suzhou and Wuxi are both administrative regions in the Taihu Lake catchment area (and its feeder rivers), and as such there is a relatively high degree of similarity in their base situations. As a result of the similarities Suzhou decided to implement a virtual copy of the policy recommendations issued by Jiangsu Province.Footnote6 Not only does textual analysis illustrate the direct nature of the copy (See: Suzhou Municipal Government Office, Citation2014; General Office of Jiangsu Provincial Government, Citation2012) but our survey responses found that officials deliberately did not consider any policy innovation or policies in other regions.

We started the transfer of the river chief system after the policy of the higher government was issued. The policy document of the higher government clearly defined the objectives to be achieved in stages. We accelerated the transfer under the pressure of the assessment and inspection of the higher government. Our policies are mainly based on those of our superiors and are laid out and concretized according to their requirements and road map. (Interview 13 September 2019)

Although a near copy of the Provincial guidance, with ‘almost no learning or adaptation’ the Suzhou’s river chief system has been evaluated as one of the high-performing systems (Nanjing Great Wall Land Real Estate Assets Appraisal Cost Appraisal Office, Citation2015). For instance, in 2017 the Joint Conference of Urban Remediation of Black and odorous Water Bodies in Jiangsu Province ranked Suzhou first in the province for the quality of its river chief system and the redevelopment and maintenance of its rivers (Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Water Affairs, Citation2017). The work of river chief system in Wujiang District of Suzhou City was commended by the state, and Hu Mingzhong, director of the District River Chief Office, was awarded as the advanced worker of the comprehensive implementation of the river chief system and Lake chief system (Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Water Affairs, Citation2021). We believe that part of the reason for the success of the program lies not only with the fact Suzhou essentially copied the Provincial model (itself based on Wuxi’s base model) but also due to the fact that their situation was very similar to that which drove Wuxi to develop the original river chief system.

Huzhou

Huzhou issued the Implementation Plan of Establishing the River Chief System in Huzhou in 2013, and the Implementation Opinions on Deepening the River Chief System in December 2014. Different from the other three cases, Huzhou is part of Zhejiang Province, which did not issue its River Chief System Regulations until October 2017. As such, the decision to develop its own river chief system was not a result of top down or vertical pressures, but rather, according to interviews and a review of official documents Huzhou decided to investigate the possibility of developing a river chief system because they not only didn’t want to fall behind others but actively wanted to be seen as a model others could look to. As a result, policymakers in Huzhou actively worked to adopt and adapt what they saw as the best policies emerging out of the raft of river chief systems being developed in other locations.

This process not only allowed them to design their own structures, but it also led them to innovate in several important ways. One of which can be seen in the inclusion of watershed governance into their river chief system. The core of this development was the inclusion of the ‘three clean and three improve goals’ to be realized by the river chief. Of these, it is worth noting that unlike Wuxi which only explicitly addressed the goal of improving water environment governance, Huzhou made the river chief responsible for ensuring; the riverbank is clean, the river is smooth and clean, the water quality of the river course is significantly improved, the riverbank greening is significantly improved, and the pollution intercepting capacity is significantly improved many of these found their way into Options. As a result, in comparison to Wuxi's river chief, Huzhou target direction offered a more diversified yet explicit target model (Huzhou Municipal Government Office, Citation2014; Wuxi Municipal Government Office, Citation2008).

In Huzhou region, the responsibilities of river chiefs at different levels have also been differentiated in policy documents. It makes clear the three core responsibilities of the municipal river chief system are the examination and approval of the work program, work promotion and coordination, and the assessment of county-level river chiefs. The four responsibilities of county-level river chiefs are: formulating and organizing the implementation of comprehensive water environment treatment plans and annual plans for river chiefs; enhancing information disclosure; organizing the supervision and assessment of township ‘river chiefs’; reporting the annual plan and summary, key projects, and work progress on time (Huzhou Municipal Government Office, Citation2013). Additionally, a more targeted and operable assessment scheme was established that has a more targeted and operable assessment scheme than the previous cases. Compared with Wuxi, there is no doubt the river chief system in Huzhou is an adaptation of the original that offered many of the elements seen in the national Options legislation.

In line with the desire to be a showcase Huzhou not only publicized their river chief structures and systems they also built the first river chief system exhibition hall in China and set up the first ‘river chief day’.

In terms of performance, it was reported that the water quality in the functional area of the river, lake and reservoir reached 100%, while the water quality of the rivers flowing into Taihu Lake from Huzhou has remained above Class III for 13 consecutive years.Footnote7 In addition, the 13 main channels in the South Taihu Lake were systematically regulated. In 2021, the Water Resources Bureau of Huzhou won the title of ‘National Advanced Collective for Comprehensively implementing the River Chief System and Lake Chief System’ issued by the Ministry of Water Resources (Huzhou Municipal Bureau of Water Affairs, Citation2021). In conclusion, Huzhou engaged in reflective learning to adapt the river chief system to its own needs based on the transfer of several river chief characteristics to create a unique system that would attract the attention of other provinces and municipalities.

Discussion

Case study results

In this study we view ‘how much of the original system is transferred’ as the dependent variable and ‘the degree to which the importing structures and environment are different’ as the independent variable. Doing this there appears to be relationship between learning autonomy and the degree to which governing bodies adapt what they transfer and where they look for ideas.

In Suqian and Huzhou, where considerable policy restructuring occurred, transfer occurred before the superior government issued a policy text. Not only did this allow local policymakers to engage in a range of horizontal transfer activities independently of higher-level authority involvement, but it helped to explain why we found considerable adaption to the initial Wuxi model, despite the fact that the environmental protection department test indicated that in part as, a result of the Wuxi system, by 2011, the water quality of 12 national assessment sections in Wuxi met the standard rate of 100%, and the water quality of the main drinking water sources met the standard rate of 100%, and the rivers above four categories in Wuxi increased from 53.2% in 2007 to about 70%.

These findings were reenforced by reports in social media and the affirmation of the work conference of government departments. As a result, the river chief system (as implemented by Wuxi) became a hot innovative brand under the promotion of multiple forces of government, media, and academia.

However, while there was a push for transfer, there were a range of local factors that mitigated against a direct copy. These included conditions ‘such as the lack of watershed governance in our local jurisdiction, illegal construction on the shores of rivers and lakes, illegal sand mining and other problems have been prominent’ (Interview 22 November 2019). These situational differences were also highlighted by another interview, who noted that the policy transfer of Suqian was driven by the watershed governance issues within the jurisdiction. More directly, Suqian was facing issues that dealt mainly with river management and protection under conventional situations, which was fundamentally different from the crisis response of Wuxi City (19 December 2019).

As a result, the policy text of Suqian's river chief system deleted much of the Wuxi policy text and replaced it with content stressing daily river management, protection, and fund investment. Interestingly, the Suqian model also removed the contents of cross-domain cooperation, which has subsequently formed one of the cores of the National policy (i.e. the river chief office). To sum up, the policy transfer of the river chief system in Suqian is not a copy or imitation, but a jurisdiction-oriented policy, which reduced the original policy content and increases the river management and protection content under the conventional situation of the jurisdiction.

Unlike Suqian which undertook transfer in a similar context (even if the exact situation was different), Huzhou engaged in the transfer process due to the competitive desires of local officials (often found across China due to how party and government promotion occurs). In general terms Huzhou tends not to be satisfied as follower; this held true in the development of the chief system for which policymakers believed they could obtain greater influence in the whole country if they could create a best practice model:

Our goal is not only to build the practice of river chief system in Huzhou into a sample of Zhejiang Province, but also to build a local model in the whole country. In fact, many of our measures are in the forefront of the whole country, such as the establishment of the first exhibition hall of river chief system in Changxing County, Huzhou. Of course, our policy practices are supported by many resources from higher authorities. (Interview 17 October 2019)

It is important to stress here that Huzhou is the first prefecture-level city in Zhejiang Province to carry out the development of the river chief system, and both Huzhou and Wuxi are prefecture-level cities around Taihu Lake. Unlike Wuxi who initially engaged in the construction of the river chief to cope with an emergency, Huzhou officials indicated that they wanted the Huzhou model to be the example for Zhejiang Province and the whole country. In fact, it was stressed that ‘many of our measures are in the forefront of the whole country [and that] our policy practices are supported by many resources from higher authorities’ (Interview 17 October 2019).

From the perspective of policy practice, Huzhou did make considerable alterations to the Wuxi's policy innovation. In addition to the formulation of new supporting systems and the introduction of more perfect assessment plans, we believe that as a result of these modifications the Huzhou River chief system has had a greater impact in the country than the initial Wuxi model.Footnote8

Role of higher-level governing authorities

In 2012, Jiangsu Province issued the opinions on the work of the river chief system, which defined the basic goals, tasks, and time schedule of the reform of the river chief system in the entire Jiangsu Province. It required municipalities establish river chief management and protection system to protect over 2,000 major regional river courses by 2014 and township river courses, village rivers and ponds by 2015. Since then, Jiangsu Provincial government and the Department of Water Resources have launched various forms of research, inspection, meetings, and assessment activities. As a result, many of the municipalities that had not initiated their own river chief policies didn’t rely on horizontal transfer but rather: ‘Our policy learning is mainly about the policy texts of the higher authorities. The higher authorities have also held some training meetings on the river chief system’ that we attended before ‘designing our system’. (Interview 17 October 2019)

Policy performance

Using the performance of the transferred policy as the independent variable and situational difference the dependent variable, we can draw a range of conclusions. First, our data shows that there appears to be a correlation between situational differences and the performance of transferred policies. Specifically, we found that policy transfer under similar situations led to better overall outcomes than systems that engaged in transfer but operated under different situations. This finding held true even when the borrowing system attempted to make appropriate adjustments to the ideas and policies borrowed. We believe that this is an artifact of the complexity of governing structures and issues in China which often makes transfer within regions where lower levels of government face similar situations more likely to succeed then interregional transfer (even when learning is involved).Footnote9

At the same time, learning and adaptation does not determine the performance of the policy transferred. The case of Suqian shows that although policymakers engaged in learning and adaptation of the Wuxi model they performed poorly across a range of indicators since the introduction of the river chief system. This is partially due to the differences in the reasons for the development of the river chief system in Wuxi and Suqian. Recall, Wuxi was responding quickly to address the issue of bacterial growth in lake water used for human consumption while the Suqian developed their system to address the management of a complex river system and its core features and structures.

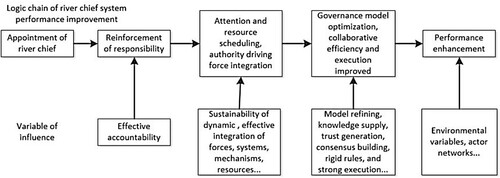

In addition, we believe that part of the reason why the river chief system was effective in Wuxi, was only tangentially linked to the appointment of the river chief. Rather it was the result of the establishment of a complete set of watershed management mechanism under the umbrella of the river chief office. As shown in , the reform of the river chief system in Wuxi strengthened the responsibility of local leaders involved in water control; with the river chief acting as a single focus with the authority to hold others involved in the management of water resources accountable for outcomes all while promoting the ‘overall’ integration of governance forces surrounding general water management.

Second, not only does the initial purpose of the river chief system need to be considered but the overall performance of the river chief system is based on many elements and mechanisms which acted to inhibit (or facilitate) the effective transfer of the Wuxi model to other locations. In short, our analysis confirmed that many of the operational mechanisms that made for the success of the Wuxi system were not directly reflected in the official policy text, but exist as a kind of tacit knowledge amongst the core actors. For instance, although Nantong tried to learn from Wuxi, they failed to fully grasp the operation logic of the river chief system due to the loss of the tacit procedures and processes that made it work because they: ‘mainly read the policy texts and news reports of Wuxi. At that time, there was no special research group set up … to discuss or reflect on the experience of Wuxi’ (Interview 12 July 2019).

Third, we found that cost matters: As stated by one interviewee ‘It needed a lot of investment to completely copy the river chief system of Wuxi. At that time, we mainly aimed to solve several problems in river management in the area under our jurisdiction’. To reduce the cost of policy implementation Nantong decided to ‘alter the original contents of the river chief system and adapted it to better fit the prominent problems’ of the jurisdiction (Interview 12 July 2019). However, the problem of routine river management and protection in Nantong proved to be considerably different from the cyanobacteria crisis that drove the creation of the river chief system in Wuxi (and the government’s desire to reduce costs made the adaptations made by Nantong ineffective).

Through comparative analysis of our cases, it appears that there is a correlation between situation differences and the performance of transferred policies. In this study, similar situations lead the implemented river chief system to perform better, while large situation differences usually lead to lower performance even in the face of learning and localized adaptations. On the opposite side, the relationship between the type of transfer undertaken and the degree of learning involved (direct copy all the way to simple inspiration) and the performance of the transferred policy was not clear. Therefore, even when a policy is transformed it still might not be compatible with the policy context of the transplanted regime due to factors such as the compatibility of policy issues, the attitude of target groups, the resources required for policy implementation, the network status of policy subjects and the macro environment.

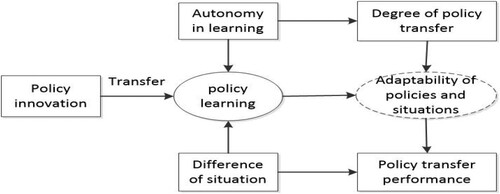

As shown in , to open the black box of policy learning (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2013; Hassink & Lagendijk, Citation2001; Nikolakis & Roberts, Citation2022; Stein et al., Citation2017), we propose that future studies work to combine learning autonomy and situational difference. We propose this as case comparison shows that learning autonomy appears to be related to the type of policy transfer undertaken (from attempting a direct copy to acting little more than an inspiration to try something new or modify what already exists – based on the experience and ideas of others), while the situational differences between importing and exporting systems appear to be related to the performance of the transferred policy.

Conclusion

Unlike many depictions of authoritarian regimes (China in particular), this study has demonstrated that local governments have considerably more policymaking and policy shaping authority than a top-down model would predict (Dong, Citation2020; Heilmann, Citation2008; Müller, Citation2015). Thus, the Wuxi municipal government was able to develop its river chief system independently of the provincial or central government in response to the outbreak of cyanobacteria. In doing this they set the stage for the transfer of the river chief system throughout the province via traditional horizontal transfer processes often observed in democratic federal political systems (Evans, Citation2009; Gilardi, Citation2013; Graham et al., Citation2013; Jones & Newburn, Citation2007; Walker, Citation1969). As the river chief system spread horizontally the provincial government in Jiangsu Province adopted the Wuxi model as its official policy (see also Robinson, Citation2011; Rogers, Citation2003). Again, this is very similar to what we see in democratic political systems as state governments adopt and subsequently transfer local initiatives into state policy (i.e. vertical transfer up). Just as in the US (and other democratic systems) once a higher level of authority adopts a policy it is often spread across the local jurisdictions in that state (vertical transfer down) as either direct copies or modified versions of the recommended policy (Kerber & Eckardt, Citation2005; Lundvall & Tomlinson, Citation2002 Radaelli, Citation2000). This is exactly what we saw in relation to the river chief system where some localities copied the Jiangsu recommendations almost directly while others made local modifications to better suit their needs (whether these be political, economic, or situational).

In addition to finding that transfer operated within Jiangsu much like we see in their democratic counterparts, but the transfer process continued with the movement of the river chief system from Jiangsu Province to Huzhou in the Zhejiang Province. In this, just as we have seen in democratic nations, the core reason initiating this movement was the desire by officials in Huzhou be seen as a leader in the area of water management or ‘as the model that others would follow’ (Interview 12 October 2019).

Not only did we find that transfer within the authoritarian governing structures of China follow similar patterns to what has been shown to occur in democratic political systems but by looking at structural and dynamic factors we demonstrated that while not causal, there is a correlation between governing autonomy and policy transfer and that the greater degree of autonomy the governing actors had, the more they actively worked to modify what was transferred to better fit their needs (even if this was not situationally appropriate)(see also Marsh & Sharman, Citation2009; Stone, Citation2017). Our study also found that situational differences are similarly correlated to the outcome performance of the transferred river chief system. In brief, we found that large situational differences appeared to have a negative impact on the performance of a transferred policy, and that this held true regardless of whether the policymakers’ attempted adaptation or simply relied on copying what was developed at a higher level of authority.

This study has helped to open the black box of policy learning and policy transfer in China and put forward an illustrative framework of policy transfer performance appears to be based more on context than actual policy design. More Specifically, it is evident that autonomy in learning, situational differences, and degree of transfer alone cannot fully explain the rationale behind effective policy transfer generation. Furthermore, policy learning does not necessarily correspond directly with the level of transfer effectiveness. Rather it is important to consider context fit. This has implications for research on transfer performance outside Chinese context as it is vital to start to consider more diverse and composite perspectives if we are to enhance the performance of the policies that are transferred, for different types of transfer and learning have their own characteristics which will vary across political systems and policy areas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David P. Dolowitz

David P. Dolowitz is a professor in the Department of Politics at the University of Liverpool, UK. His research interests include policy transfer, knowledge development, water management and the potential of China to transfer lessons (particularly in relation to water management) to other nations.

Ye Xiong

Ye Xiong is a lecturer at the Institute of environment and health, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China. His research fields include the transfer of policy innovation between regions in China and the institutional innovation of river basin governance.

Notes

1 Success in a policy setting is often subjective and could involve several different potential outcomes being pursued by the same policy – both stated and unstated (see Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000; Marsh & Sharman, Citation2009).

2 It is important to note that the separation of the party and the government is no longer mentioned in Xi’s era, and the overall leadership of the party has become the mainstream discourse in China. At present, the policy document for the river chief system is jointly issued by the party and government, that is, the general office of the party and the general office of the administrative department are the joint issuing units. In addition, the river chief is led by local party and government leaders, who are also the leaders of the party and government in China. That is, the chief executive also serves as the party secretary. Therefore, without observations that were not authorized for this study it is difficult to distinguish the role differences between the party and government in the transfer of the river chief system. Of course, in some technical and professional fields, the party's leadership is mainly in political direction, and there is not much intervention, mainly for administrative departments to explore.

3 The municipal administrative regions of Suqian, Nantong and Suzhou belong to Jiangsu Province. In September 2012, Jiangsu Province issued the policy on Strengthening the ‘River Chief System’ for River Management in the whole Province, marking the compulsory promotion of the river chief system in the whole province. In May 2008, Suqian issued policy on the Establishment of ‘River (Lake) Chief’ system in the region’s rivers and Lakes. Therefore, Suqian carried out policy transfer before the provincial policy was issued. Nantong Municipal Government issued Opinions on Strengthening the ‘River Chief System’ of the region’s River Management in January 2014, and Suzhou issued policy on the Implementation of the ‘River Chief System’ of the region’s River Management in January 2014. Huzhou, a subordinate to Zhejiang Province, issued the Implementation Plan for the Establishment of ‘River Chief System’ in Huzhou region in 2013. Suqian has numerous rivers and lakes within its jurisdiction and dense river network with over 2045 river channels above county and township level, and a water area accounting for one fourth of the land area. The prominent problems lie in the function management of river channels and the development and utilization management of river shorelines within the jurisdiction. Therefore, governance situation in Suqian is quite different from that in Wuxi. Nantong has a flat terrain and a network of rivers and ditches. The water system is roughly bounded by the Tongyang Canal and Rutai Canal. The Huaihe River basin covers an area of more than 2200 square kilometres in the north and the Yangtze River basin covers an area of more than 5700 square kilometres in the south. Rivers at all levels interweave into a network and communicate with each other. The Yangtze River coastline within the territory is 166 kilometres, and the river surface extends southeast in a trumpet shape..The difficulty of watershed governance of Nantong lies in the complex rivers within its jurisdiction, which is different from Wuxi. The water systems in Suzhou take Taihu Lake as the center, including the ‘three vertical and three horizontal’ backbone river and branch river channels with more than 40% of the surface covered by water. Therefore, Suzhou is like Wuxi. Huzhou, located in the north of Zhejiang Province and the southwest of Taihu Lake, bordering Wujiang City of Jiangsu Province and Tongxiang City of Jiaxing in the east. Like Wuxi, Huzhou is a region around Taihu Lake, and the main channel connecting Taihu Lake is five key channels, namely Tai Chi, Luo Lougou, Huan Lougou, Pu Lougou and Tang Lougou. Overall, as a prefecture-level city around Taihu Lake, the river and lake governance situation in region Huzhou is like Wuxi (For more information see: Nantong Historical Records Network’ http://www.ntszw.gov.cn/?c=index&a=show&id=2460; How many rivers are there in Suzhou. https://www.sohu.com/a/206862173_100044954.2017-11-27; Huzhou water ecological environment protection fourteen – fifth plan, http://www.huzhou.gov.cn/hzgov/front/s1/xxgk/sswgh/sswzxgh/ybzxgh/sthbl/20220315/i3140804.html).

4 We want to stress that while this paper uses the method of multi case comparison to preliminarily analyze the impact of policy learning control and policy situation on the degree of policy transfer and performance, we can only discuss correlations as the in-depth case study approach taken cannot address causal mechanism.

5 The water system is roughly bounded by the Tongyang Canal and Rutai Canal. The Huaihe River basin covers an area of more than 2200 square kilometres in the north and the Yangtze River basin covers an area of more than 5700 square kilometres in the south. Rivers at all levels of local government interweave into a network and connect with each other. Nantong Historical Records Network. See: http://www.ntszw.gov.cn/?c=index&a=show&id=2460 (accessed 4/8/2022).

6 Textual analysis of the policy documents of Suzhou River chief system and those of Jiangsu Province, demonstrate the virtual copy of the provincial policy in relation to the value significance, guiding ideology, basic principles, objectives and tasks, organizational system, and core measures of the policy.

7 For more information on the different classes of water quality and purpose see: https://english.mee.gov.cn/SOE/soechina1997/water/standard.htm.

8 The reconstruction of Huzhou is not simply driven by the issue of jurisdiction, but by the performance competition among localities, that is, trying to promote re-innovation to obtain a national demonstration effect.

9 It should be stressed that there are cases of successful transfer even where there are large jurisdictional differences in policy situations. The issue is that under such situations there tends to be considerably higher requirements on learning capacity, willingness, interest, and ability.

References

- Bai, Z., & Liu, J. (2020). China’s governance model and system in transition. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 9(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2020.1744229

- Brown, G. (1995). What is involved in learning? In C. Desforges (Ed.), An introduction to teaching: psychological perspectives (pp. 11–33). Blackwell.

- Clarke, J., Bainton, D., Lendvai, N., & Stubbs, P. (2015). Making policy move. Policy Press.

- Denzau, A., & North, D. (1994). Shared mental models: Ideologies and institutions. Kyklos, 47(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1994.tb02246.x

- Dolowitz, D. (2017). Does transfer lead to learning? The international movement if information. CEBRAP Review Novos Estudos, 17(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.25091/S0101-3300201700010002

- Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (1996). Who learns what from whom? Political Studies, 44(2), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00334.x

- Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance, 13(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00120

- Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (2012). The future of policy transfer research. Political Studies Review, 10(2), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00274.x

- Dolowitz, D., Plugaru, R., & Saurugger, S. (2020). The process of transfer: The micro-influences of power, time and learning. Public Policy and Administration, 35(4), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076718822714

- Dong, L. (2020). China’s renewed perception of global environmental governance. Chinese Jouranl of Populaiton, Resources and Environment, 18, 319–323.

- Dunlop, C., & Radaelli, C. (2013). Systematising policy learning. Political Studies, 61(3), 599–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00982.x

- Evans, M. (2009). Policy transfer in critical perspective. Policy Studies, 30(3), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870902863828

- Fritsch, O., & Benson, D. (2020). Mutual learning and policy transfer in integrated water resources management. Water, 12(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010072

- General Office of Jiangsu Provincial Government. (11 September 2012). Notice on strengthening the work of river chief system of river management in Jiangsu Province, internal documents.

- Gilardi, F. (2013). Transnational diffusion: Norms, ideas, and policies. In W. Carlsnaes, T. Risse, & B. Simmons (Eds.), Handbook of international relations (pp. 453–477). Sage.

- Graham, E., Shipan, C., & Volden, C. (2013). The diffusion of policy diffusion research in political Science. British Journal of Political Science, 43(3), 673–701. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000415

- Hassink, R., & Lagendijk, A. (2001). The dilemmas of interregional institutional learning. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 19(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1068/c9943

- Heilmann, S. (2008). Policy experimentation in China’s economic rise. Studies in Comparative International Development, 43(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-007-9014-4

- Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., & Perl, A. (2009). Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems. Oxford University Press.

- Huang, X., & Kim, S. E. (2019). When top-down meets bottom-up: Local adoption of social policy reform in China. Governance, 33(2), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12433

- Huzhou Municipal Bureau of Water Affairs. (27 January 2021). Huzhou won the title of national advanced collective for comprehensively implementing the river chief system and lake chief system. Retrieved 30 September 2022 from https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1690003733439938155&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- Huzhou Municipal Government Office. (15 December 2014). Implementation opinions on deepening the river chief system, Internal Document.

- Huzhou Municipal Government Office. (8 August 2013). Implementation plan of establishing the river chief system in Huzhou, Internal Document.

- Jacoby, W. (2002). Talking the talk and walking the walk: The cultural and institutional effects of Western models. In F. Bonker, K. Muller, & A. Pickel (Eds.), Post-communist transformation and the social sciences (pp. 129–151). Rowman and Littlefield.

- Jiangsu Provincial Department of Water Resources and the Department of Finance. (March 2016). Circular on the assessment of the management of key rivers in Jiangsu Province in 2016, Internal Document: Jiangsu Provincial Department of Water Resources (non-public).

- John-Steiner, V. (1997). Notebooks of the mind: Explorations of thinking. Oxford University Press.

- Jones, T., & Newburn, T. (2007). Policy transfer and criminal Justice. Open University Press.

- Kerber, W., & Eckardt, M. (2005). Policy learning in Europe: The ‘open method of coordination’ and laboratory federalism’, Thünen-Series of Applied Economic Theory – Working Paper, No. 48. Universität Rostock, Institut für Volkswirtschaftslehre, Rostock.

- Li, W. (2021). Design and learning effects of China’s expert advisory committees. Policy Design and Practice, 4(4), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1915596

- Lundvall, B., & Tomlinson, M. (2002). International benchmarking as a policy learning Tool. In M. Rodrigues (Ed.), The new knowledge economy in Europe (pp. 203–231). Edward Elgar.

- Marsh, D., & Sharman, J. (2009). Policy diffusion and policy transfer. Policy Studies, 30(3), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870902863851

- Martin, G., & Beaumont, P. (1998). Diffusing “best practice” in multinational firms. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9(4), 671–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/095851998340955

- Meseguer, C. (2005). Policy learning, policy diffusion, and the making of a new order. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 598(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716204272372

- Mukhtarov, F. (2014). Rethinking the travel of ideas: Policy translation in the water sector. Policy & Politics, 42(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655459

- Müller, M. (2015). (Im-)mobile policies. Why sustainability went wrong in the 2014 Olympics in Sochi. European Urban and Regional Studies, 22(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776414523801

- Nanjing Great Wall Land Real Estate Assets Appraisal Cost Appraisal Office. (August 2015). Performance evaluation report of Jiangsu Province's backbone river management and protection (2014) project. Internal Documents (non-public).

- Nantong Municipal Government Office. (8 January 2014). Opinions on strengthening the river chief system of river management in the city. Internal Document.

- Nikolakis, W., & Roberts, E. (2022). Wildfire governance in a changing world: Insights for policy learning and policy transfer. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 13(2), 144–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12235

- Parton, C. (28 June 2018). China’s top-down governance model is flawed. Financial Times. Retrieved 20 August 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/71838d7a-7a30-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d.

- Patton, M. (2001). Evaluation, knowledge management, best practices, and high quality lessons learned. American Journal of Evaluation, 22(3), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/109821400102200307

- Peck, J. (2011). Geographies of policy: From transfer-diffusion to mobility-mutation. Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 773–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510394010

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010). Mobilizing policy: Models, methods, and mutations. Geoforum, 41(2), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.01.002

- Prince, R. (2010). Policy transfer as policy assemblage: Making policy for the creative industries in New Zealand. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(1), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4224

- Prince, R. (2012). Policy transfer, consultants and the geographies of governance. Progress in Human Geography, 36(2), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511417659

- Purcell, J. (1999). Best practice and best fit: Chimera or cul-de-sac? Human Resource Management Journal, 9(3), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.1999.tb00201.x

- Radaelli, C. (2000). Policy transfer in the European Union: Institutional isomorphism as a source of legitimacy. Governance, 13(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00122

- Robinson, J. (2011). The spaces of circulating knowledge: City strategies and global urban governmentality. In E. McCann, & K. Ward (Eds.), Mobile urbanism: Cities and policymaking in the global age (pp. 15–40). University of Minnesota Press.

- Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press.

- Rose, R. (1991). What is lesson-drawing? Journal of Public Policy, 11(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00004918

- Rose, R. (1993). Lesson-drawing in public policy. Chatham House.

- Rose, R. (2005). Learning from comparative public policy. Abingdon.

- Simon, H. (1947). Administrative behaviour. Free Press.

- Stein, C., Michel, B., Glaze, G., & Putz, R. (2017). Learning from failed policy mobilities: Contradictions, resistances and unintended outcomes in the transfer of “Business Improvement Districts” to Germany. European Urban and Regional Studies, 24(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776415596797

- Stone, D. (1999). Learning lessons and transferring policy across time, space and disciplines. Politics, 19(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.00086

- Stone, D. (2017). Understanding the transfer of policy failure. Policy & Politics, 45(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14748914098041

- Suqian Municipal Government Office. (May 2008). Opinions on establishing the river (lake) chief system in rivers and lakes in the city, Internal Document.

- Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Water Affairs. (29 August 2017). Suzhou River chief system reform leads the whole province. Retrieved 28 October 2022. http://water.suzhou.gov.cn/slj/mtjj/201708/767ddc4ba2a5487e8358484b2a5660fe.shtml.

- Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Water Affairs. (8 June 2021). The reform of the system of river chief and lake chief in Wujiang District was commended by the state. Retrieved 28 October 2022. http://water.suzhou.gov.cn/slj/mtjj/202106/9f59fcf7410040688f8fcee121bde579.shtml.

- Suzhou Municipal Government Office. (24 January 2014). Notice on the implementation opinions on strengthening the river chief system of river management in the city, internal document.

- Walker, J. (1969). The diffusion of innovations among the American states. American Political Science Review, 63(3), 880–899. https://doi.org/10.2307/1954434

- Ward, K. (2006). Policies in motion. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00643.x

- Wolman, H., & Page, E. (2002). Policy transfer among local governments. Governance, 15(4), 577–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0491.00198

- Wuxi Municipal Government Office. (3 September 2008). Decision on comprehensively establishing the river chief system and comprehensively strengthening the comprehensive and comprehensive improvement and management of river courses, Internal Document.