ABSTRACT

The developmental state paradigm (DSP) has traversed global south contexts from Latin America to Asia with a revival in African contexts. However, there is limited understanding of how international political economy (IPE) dynamics influence the analysis offered by the DSP. This article addresses this gap by introducing an IPE-enhanced DSP that centres interactions between the state and international capital in the analysis of industrialisation in the Ethiopian leather subsector and the role of Chinese investment. Its key finding is that these complex interactions influence and disrupt the classical roles of domestic private capital and domestic industrial demand in socio-economic transformation.

RÉSUMÉ

Le paradigme de l’État développemental (PED) est courant dans l’analyse économique des pays du Sud global, que ce soit en Amérique latine ou en Asie, et connaît une recrudescence dans l’étude des pays Africains. Cependant, l’on ne comprend pas encore complètement comment les dynamiques d’économie politique internationale (EPI) influencent l’analyse offerte par le PED. Notre article se penche sur cette question en proposant un PED informé par l’EPI, qui recentre les interactions entre l’état et le capital international dans l’analyse de l’industrialisation du sous-secteur du cuir en Éthiopie, ainsi que le rôle des investissements chinois. Sa principale conclusion est que ces interactions complexes viennent à la fois influencer et déstabiliser les rôles traditionnels des capitaux privés nationaux et de la demande industrielle nationale dans les transformations socio-économiques.

Introduction

The developmental state paradigm (DSP) remains an important and relevant framework for analyses of socio-economic and political development across global south and global north contexts. However, within this body of work, there is limited conceptual treatment of how states’ interactions with development processes are impacted by international dynamics. This article offers an international political economy (IPE)-enhancement of the DSP that centres the state’s engagement with notable global economic forces using a case study of Ethiopia. In doing so, it makes an original contribution on the complex ways through which extranational dynamics impinge on the Ethiopian state’s actions in developmental pursuits. The article’s analysis considers the Ethiopian context as a basis for concept building and expansion and responds to longstanding calls to centre African contexts, their dynamisms and complexities, in theory building within the social sciences (Ake Citation1982).

The most robust facet of the Africa rising narrative is of net resource importers that have shown resilience with steady and stable growth through resource price crises. Ethiopia is the noted star of the continent in this regard attaining the highest growth globally in 2017 as well as an average of 10.3 per cent growth from 2006 to 2017 alongside a 20 per cent fall in its headcount poverty rate since 2000 (World Bank Citation2020; UNDP Citation2018). The Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF)-led state draws its notions of developmental capitalism fundamentally from the experiences of the developmental states Taiwan and South Korea although claims have also been made about lessons from China (Zenawi CitationForthcoming; Bezawagaw et al. Citation2018).

This article responds to the central question, to what extent do interdependencies exist and function across the state and private capital, especially Chinese foreign investment, within industrial development and therein movements between the agricultural and manufacturing sectors in leather production in Ethiopia? In responding to the question, it utilises an extended lens of the DSP to undertake its analysis, the IPE-enhanced DSP. The IPE-enhancement of the DSP is based on Hirschman’s linkages thesis. It examines the relationship between agricultural and industrial sectors through examination of industrial policy, resource movements and industrial development outcomes.

The IPE-enhanced DSP highlights two sets of dynamics for conceptualising interdependencies between the state and private capital, especially international capital, namely: synergies between fiscal linkages and savings for investment; synergies between production linkages and the use of raw materials for industrial production; synergies between consumption linkages and domestic demand for manufactured goods; and the lines of influence in the economic, social and political factors that undergird state actions.

This article makes an original contribution to the political economy of development and on the conceptualisation of developmentalism that is rooted in African empiricism. It builds on a rich literature on developmental statehood in Africa from early studies on Botswana and Mauritius to later studies on Nigeria, South Africa, Rwanda, Uganda, Ghana, Namibia and Ethiopia, among others. By highlighting the importance of international capital the article progresses beyond the conceptual focus of the DSP on the domestic sphere due to its basis in the state-market dichotomy. Radice (Citation2010) highlights how the analytical foundations of the developmental state thesis in this dichotomy overlooks the powerful influence of global market forces on state engagement with development processes and outcomes.

This article is a timely analysis as it relates to Ethiopia as a space in flux. The succession of the EPRDF by the Prosperity Party has led to debate around the changes in Ethiopia’s developmental statehood trajectory with purposed shifts towards Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s Medemer-led development agenda (Mariam Citation2019; Lashitew Citation2019). Medemer-led development offers more liberal policy directions, including concerns with public financing of infrastructural investment, delinking of public debt from its critical role in addressing industrial investment and adopting a home-grown economic liberalisation agenda, that is, the Addis Ababa Consensus and trade policy changes to liberalise raw material exports (FRE Citation2019; Samaro Citation2019; Gelan Citation2019; Astatike Citation2020).

The rest of the article is divided into four sections. First, the article articulates the IPE-enhanced DSP as a conceptual advancement that examines the influence of international capital. Second, it discusses the literature and recent trends in developmentalism and shows the utility of the IPE-enhanced DSP in the Ethiopian case. Third, it deploys the IPE-enhanced DSP in the Ethiopian leather subsector in response to the research question. Fourth, it concludes with a reflection on the analytical utility of an expanded DSP and its wider relevance.

The IPE-enhanced DSP: bringing international political economy dynamics back in

Contemporary attention to industrial policy draws on the DSP’s challenge to mainstream thinking on the primacy of the market mechanism as well as antagonism between the state and the market in socio-economic transformation. This is evidenced in both the Post-Washington Consensus and New Structural Economics (Stiglitz Citation2008; Lin Citation2012). The DSP relies on classical development economics for its theoretical understanding of the role of the state in development: in the generation of savings for investments to support industrial transformation, design and implementation of industrial policy and creation of relevant institutions and investment in physical and social infrastructure (see Amsden Citation1989; Wade Citation1990; Lewis Citation1954; Gerschenkron Citation1962; Hirschman Citation1958).

Fine (Citation2007) presents the DSP as comprising distinct economic and political schools. These are concerned with developmental economic policies and the nature and construct of the state, respectively. Mkandawire (Citation2001) highlights a similar distinction in the ideology-structure nexus. The schools show a dichotomy between economic and political spheres as opposed to their intrinsic interrelatedness. The dichotomy underpins the DSP’s analytical focus on the domestic sphere as the domain of the state with limited conceptual engagement with global economic dynamics.

However, the well-celebrated achievements of the Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese developmental states relied extensively on interaction with the global economy. First international trade has been central to the defining characteristics of developmental statehood. The focus of the discourse on international trade vis-à-vis developmental states has been on the influential role of exports of agricultural as well as manufactured and industrial goods (Akyuz, Chang, and Kozul Wright Citation1998; Wade Citation1990; Amsden Citation1989).

Second, the contestations around the post-second world war global influence of communist regimes underscored untied development finance from the US to Taiwan and South Korea. Thorbecke (Citation1979) has suggested that from 1951 to 1965, the US financed agriculture extensively through allocating one-third of its total aid to the sector through the Sino American Joint Commission for Rural Reconstruction (JCRR). Tsai (Citation2002, 138) has argued that, the making of the developmental state in Taiwan was precipitated by an international system dominated by the US. He highlights especially the transition of US financial support from military to substantial sums of economic aid (also to South Korea). Bowles (Citation2020, 3) argues that “US procurement for its military campaigns” supported industry in South Korea and Taiwan. This suggests that developmental states pursued developmental agendas that were shaped by the realities of different interests including those of international capital and global polar states.

Nem Singh and Ovadia (Citation2018) provide an overview of DSP concept-building and articulate two themes relating to international dynamics that are also underpinned by classical development thought: protecting domestic private capital from more dominant foreign capital and mobilisation of financial resources. Weiss and Thurbon (Citation2020, 4) adapt economic statecraft to explain state engagement with “domestic economic activities, in efforts to counter geopolitical and/or geoeconomic challenges.” Bowles (Citation2020) shows how the continued relevance of the DSP requires analytical treatment of globalisation dynamics including financial liberalisation, global production networks (GPN), globalised trade and climate change and changing social relations. These important contributions ideate about interactions between the DSP and international dynamics. This article makes its contribution with its development and application of an analytical framework, IPE-enhanced DSP.

Analyses of GPN and global value chains (GVC) challenge developmentalism (Gereffi Citation2014). But there is increasing recognition of the need to reengage the structures that underscore these dynamics, including the state (Horner and Alford Citation2019). Hauge (Citation2020) outlines how GVC debates are amiss in not recognising their antecedents in the developmentalist literature with reflections on South Korea and Taiwan. Oqubay (Citation2016, 196) also notes the limitations of GVC debates in analysing dynamism and agency of some global south contexts with the focus on lead firms as located predominantly in industrialised economies.

The DSP has the capacity for extension given its theoretical basis in the inductive examination of empirical experiences. For Masterman (Citation1970) paradigm extension requires the retention of key principles of the original paradigm while introducing new aspects that address new questions and expand an extant community of scientists. This provides a basis for (i) maintaining principles of analysing the state’s role in industrial development and methodological reliance on case studies and (ii) (re)introducing significant issues such as agriculture, state-market interdependencies and IPE dynamics as long as they have been relevant in the DSP’s own empirical underpinning.

Hirschman (Citation1981) identifies three main categories of linkages as follows: fiscal linkages refer to the state’s use of resources that accrue to it from taxes (from natural resources) to irrigate other sectors, (forward) production linkages refer to the use of the primary sector’s outputs as raw materials for production in other sectors and consumption linkages refer to the domestic industrial demand resulting from income generated within the primary sector. Ovadia and Wolf (Citation2018) emphasise a contemporary need to recentre demand as critical to developmental statehood in African contexts. This ties in also with African development policy directions that are refocusing on domestic regional markets through continental economic and trade integration with the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Ikpe (Citation2013, Citation2018) draws on Hirschman’s linkages thesis, to propose a framework for broadening analysis of industrialisation to include the primary sector. Drawing also on Japanese, South Korean, Taiwanese, Indonesian and Nigerian experiences, it shows that states influence structural transformation processes and outcomes by managing fiscal, consumption and (forward) production linkages across agricultural/fuel and manufacturing sectors to address classical constraints on industrialisation, particularly during initial stages of structural transformation. While these analyses offer a rich examination across time, space and issue, there is silence on the ways in which international capital and associated dynamics interact with linkages and impinge on underlying economic, political and social factors that underpin the actions of the state.

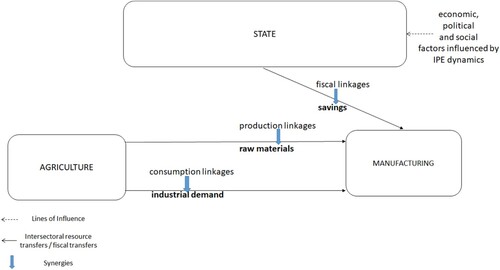

This study on Ethiopia presents an opportunity to enrich the developmental state discourse further through reintroducing the influence of IPE dynamics. The IPE-enhanced DSP in , highlights two sets of dynamics as a basis for conceptualising. The first is synergies, that is, between fiscal linkages and savings for investment; between production linkages and the use of raw materials for industrial production; between consumption linkages and domestic demand for manufactured goods; and the lines of influence in the underlying economic, social and political factors that undergird state actions. Building on Hirschman’s thesis the IPE-enhanced DSP centres the state in this process while considering its interrelatedness with the market in domestic and international capital across both synergies and lines of influence.

Figure 1. IPE-enhanced DSP (adapted from Ikpe Citation2018).

Methodological approach

This article undertakes a case study analysis of the leather sector in Ethiopia. It deploys the IPE-Enhanced DSP as an analytical tool for understanding how the interdependencies between the state and foreign private capital interact with industrial development. The leather sector is selected for two reasons. First, it has been prioritised by the Ethiopian state as a basis for industrial development in attempts to establish and strengthen fiscal, production and consumption linkages. These occur through the generation of savings from exports, production of higher value leather goods from hides and skin as well as mixed commitments to addressing local market needs as emphasised in the Industrial Development Strategy and the Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda (Oqubay Citation2016, 79–80; FRE Citation2019). This allows some reflection on ongoing policy transitions associated with the Medemer model. Second, the sector has a longstanding engagement with foreign private capital that has seen recent expansion with a leading role for Chinese capital (Xiaoyang Citation2019).

Ovadia and Wolf (Citation2018) emphasise the methodological importance of case study approaches in theorising developmental statehood with mixed-methods analysis using descriptive quantitative and qualitative methods. This article analyses processed and unprocessed quantitative data from Ethiopian government databases including the National Bank of Ethiopia and the Leather Industry Development Institute (LIDI), China–Africa Research Initiative (CARI) Database, UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), UN Comtrade and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators on foreign loans and investment, national economic indicators and the Ethiopian leather subsector. Descriptive statistics are used to analyse the trends in the data sets. The article triangulates these findings with the analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies on the Ethiopian leather sector in relation to the interactions between the state, industrial policy, foreign and domestic private capital in the production and trade of hides and skin, crust leather, finished leather and leather goods. There are challenges with the secondary analysis of qualitative studies as these have been organised around set questions and objectives. However, this approach has been valuable in enabling a synthesis of published studies that address relevant themes from a range of perspectives.

The problem of data quality and its impact on development research in Africa abounds across time on the veracity of indicators. This can be due to contestations between national bodies as well as between national and international bodies, misreporting by governments to data banks as well as by frontline agencies to national government bodies (Jerven Citation2013, Chapter 3; Sandefur and Glassman Citation2015). In Ethiopia, data challenges are highlighted in the politicising of data to support narratives of development progress, challenges with agricultural data and the inconsistencies of data on economic indicators (Mandefro Citation2016; Cochrane and Bekele Citation2018a, Citation2018b). For instance, although the data trends on the leather sector from FAO and LIDI are similar there are some disparities in the values that call for a cautious interpretation of analysis.

To address the risk of data misreporting to government authorities the study also utilises unprocessed data from LIDI which is collated directly from the industry. The data is incomplete in parts including on export volumes. Different data sources use different calendar systems; LIDI data is based on the Ethiopian calendar. This can pose problems for comparability across sources. This is addressed by the standard practices of citing data across two years and accounting for this in the analysis.

Developmental statehood in Ethiopia: considering the literature

The literature on developmental statehood in Africa, has roots in Mkandawire’s (Citation2001) conceptual contribution that referenced the significance of industrialisation in the post-independence era. This pivotal work challenged the DSP’s hitherto tautological focus on outcomes by insisting on the need to pay attention to “trial and error” and the possibilities therein for examining African economies within this framework (Mkandawire Citation2001, 291). Ethiopia emerges as a contemporary case of significance in the ongoing expansion of this body of work. On the theme of state-private sector interactions, Zenawi (Citation2012) discusses developmental statehood as contingent on social and political processes towards outcomes of accelerated development and intent on the obligatory distance between the state and private sector. Pellerin’s (Citation2020) study on the chambers of commerce argues that the state has influenced its construct driven both by economic and political imperatives for developmentalism. While this offers greater reflection on the complexities of the Ethiopian state’s interactions with private capital there is limited engagement with how the state is influenced and impinged upon in these processes thus reinforcing analytical reliance on the state-market dichotomy. This article responds to this gap by centring the state’s interdependence with (foreign) private capital.

Lefort (Citation2012) analyses developmental statehood in the state’s interactions with differentiated agricultural constituencies but also highlights farmers’ negotiations on engagement with interventions. Planel (Citation2014) presents the notional efficiency of the Ethiopian agricultural bureaucracy and how its lack of flexibility and malleability to local conditions, realities and knowledge undermines developmental outcomes. Chinigò (Citation2015) examines how the Ethiopian state’s interactions with foreign capital and farmers in agricultural commercialisation processes have impinged on the state in interactions between local and central authorities. This links also to arguments about the intense centralisation of the Ethiopian developmental state and the contradictions therein with ethnic federalism (Abebe Citation2018; Hailu Woldegebrael Citation2018). While these studies give a welcome nuanced picture of the interactions between the state and private sector in the dominant agricultural sector, they do not locate agriculture along the trajectory of industrial development in line with the DSP logic. This article addresses this gap by centring linkages across agriculture and manufacturing in its analysis.

Across these rich contributions, the debates on Ethiopia’s developmental statehood remain entrenched in the domestic realm with limited reference to how extranational dynamics impinge on the Ethiopian state’s actions in developmental pursuits. This is despite the substantial role of international capital in Ethiopia’s growth trajectory. Feyissa (Citation2011), Gagliardone (Citation2014) and Clapham (Citation2018) reflect on the Ethiopian state’s negotiated engagement with global development policy and access to donor funds and foreign investment in a largely empirical sense, but there is room for a more conceptual treatment of these complex dynamics as is being offered in this article.

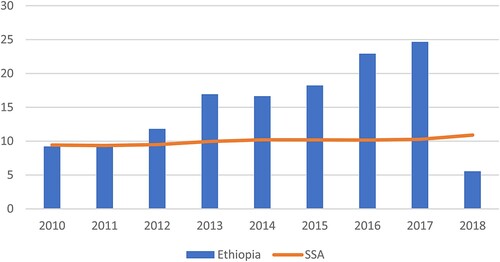

Ethiopia shows the significance of agriculture and manufacturing to building economic resilience in the narrative on emergence. There has been a stronger role for industrial development with manufacturing value added, as a percentage of GDP, increasing by about 15 per cent over 2010–2017 as observed in . This growth is more impressive against the background of Sub-Saharan Africa’s performance. There have been patterns of consistent improvements in manufacturing and its enduring linkages with agriculture. The World Bank (Citation2018, vii, 2) notes manufacturing performance has been energised by stronger agricultural performances.

Figure 2. Manufacturing value added-MVA (% of GDP). Source: World Development Indicators (Citation2020).

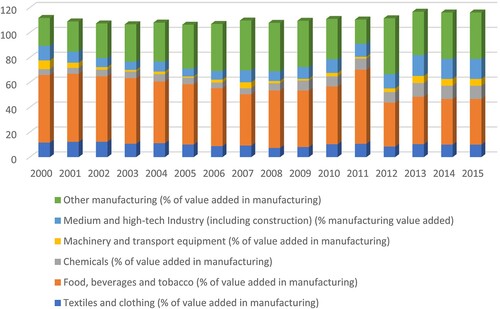

MVA expansion has occurred against the background of industrial policy that has its basis in links between agriculture and manufacturing. This is most directly typified by the Agricultural Development Led Industrialisation (ADLI) strategy. This has influenced policy programmes including the Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction Program (SDPRP) and the Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP) (Ohno Citation2009). The Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) has followed with greater emphasis on early industrialisation. Focus has been on key sectors that exhibit strong interactions across the primary and secondary sectors including leather, food processing-sugar and textiles as within the Industrial Development Strategy (Gebreeyesus Citation2013; Shiferaw Citation2017). shows that of the priority sectors, food and beverages, with linkages across agriculture and manufacturing, is the most dominant with fluctuating performances and the textiles subsector, including leather, has remained consistent since 2010 at about 10 per cent but these have not generated much of the recent expansions in MVA noted in .

Figure 3. Composition of manufacturing value added across sectors in Ethiopia. Source: World Development Indicators (Citation2020).

The prominence of industrial policy in Ethiopia through the late 1990s and 2000s is significant given global development policy directed by market fundamentalist strategies. However, Ethiopia was subject to structural adjustment and enhanced structural programmes over 1992–1999 as well as poverty reduction programmes over 2002–2009; Feyissa (Citation2011) denotes this as linked to the EPRDF-led state’s negotiation with international donor communities in the global north. Gebreeyesus (Citation2013) and Ohno (Citation2009) suggest that increasing liberalisation has underscored Ethiopia’s latter-day successes. But others have offered a more nuanced reading of the integration of degrees of economic liberalisation with a longstanding and coherent industrial policy across regimes as well as a stronger negotiating position with key global development policy actors on account of a lower debt burden and the political will to pursue a set industrial agenda (Oqubay Citation2019).

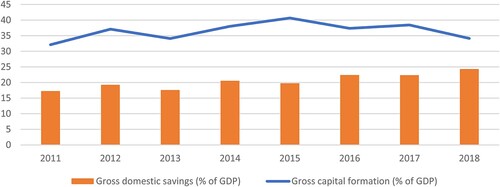

Another key element of Ethiopia’s industrial strategy is the importance of foreign direct investment flows. Despite improving performances, Ethiopia suffers a substantial savings-investment gap as evidenced by . The gap has been met consistently through international capital flows, including Chinese capital (UNCTAD Citation2002). This interaction has faced criticism across time (World Bank Citation2019). Over 2000–2018, Ethiopia was the largest African recipient of Chinese loans at 13.7 billion USD (CARI Citation2018). Over 2005–2018 Ethiopia was the highest recipient of Chinese investment flows in the Horn at a total of 1.6 billion USD and the highest recipient of investment stocks in East Africa and the Horn at 11.4 billion USD (CARI Citation2018). China has been the second-largest export market for Ethiopia following a rapid ascent and is thus a key source of foreign exchange (NBE Citation2017).

Figure 4. Savings gap in Ethiopia: gross capital formation and gross domestic saving (% of GDP). Source: World Development Indicators (Citation2020).

The Ethiopian case offers rich contemporary empirical experiences that present an African basis for the conceptual development of the DSP. Recognition of this reality has given rise to its rich emerging literature on developmental statehood. However, these remain largely focused on the domestic context despite the significant role of international capital in Ethiopian developmentalism. The IPE-enhanced DSP contributes original analysis to this body of work with the conceptualisation of developmental statehood that considers movements across agricultural and manufacturing sectors and it traverses the strictures of state versus market framings through the analysis offered by its synergies and lines of influence.

Deploying the IPE-enhanced DSP in the Ethiopian leather sector

The leather industry has been selected by the state as one of the “few industries to lead its ambitious industrialization agenda … prioritized because of their expected linkages with the agricultural sector … ” (Shiferaw Citation2017, 5). Hides and skin are an agricultural by-product of the livestock sector and Ethiopia is noted as an important base for leather goods producers due to access to raw materials and low labour costs (KIDI Citation2013, 470).

International capital has historically had a strong role in the Ethiopian leather sector. GRM International (Citation2007) and Oqubay (Citation2016, 195) highlight the foundational role of Armenian investment. China’s growing interaction with the Ethiopian leather industry is reinforced by its ascension to the second-largest export market for Ethiopia within which leather and leather goods play a significant role (NBE Citation2017). Major Chinese leather company Huajian is estimated as using 30–60 per cent of the local hides and skin for its production (Giannecchini and Taylor Citation2018; Xiaoyang Citation2019). Over 2010–2018, Chinese investment in tanneries has made it the largest investing country in the leather sector (Xiaoyang Citation2019). Fitawek and Kalaba (Citation2016) show foreign investment inflows to the Ethiopian leather sector from China increased from 0.43 million USD to 58.53 million USD over 2004–2010. Despite being a sector that is dominated by local ownership structures, international capital is playing a disproportionately significant role especially in upward shifts across the value chain for trade.

The rest of the section deploys the IPE-enhanced DSP as depicted in in response to the research question. This analysis sets out an examination of synergies and lines of influence in the following four subsections as follows: the synergies between fiscal linkages and savings with attention to Chinese investment and the generation of foreign exchange; the synergies between production linkages and the use of raw materials for leather and leather goods manufactures as influenced by Chinese and local firms’ interactions; the synergies (or lack thereof) between consumption linkages and domestic demand for leather manufactured goods; and the lines of influence in how economic, social and political factors that undergird state actions have interacted with interests, actions and negotiations with international and domestic capital.

Synergies in leather: fiscal linkages and savings for investments in the leather sector

Two roles emerge for the Ethiopian state that intersect with foreign capital: (i) its foregoing of fiscal revenue, through incentives to manufacturers, and (ii) the prioritisation of the leather industry within industrial policy, primarily as a source of foreign exchange. These are examined as synergies between fiscal linkages and savings. First, the Ethiopian state drives fiscal transfers to manufacturing by foregoing revenue to incentivise international private investment inflows. Gebreeyesus (Citation2013, 24) highlights “100 per cent exemption from the payment of duties on import of all investment capital goods and raw materials necessary for the production of export goods, and tax holidays on profit for five years … .” However, tax revenue has been on a declining trend since 2010 falling to 11.6 per cent of GDP in 2016, against the target of 17 per cent of GDP (UNIDO Citation2018). This reflects the complex realities of fiscal transfers from the state to private and especially foreign capital.

Second, savings are pursued by the state as a basis for fiscal linkages to support industry in how the leather sector is “part of a wider push, … to widen and deepen exports with the ultimate goal of generating sufficient foreign exchange to fund ongoing large-scale development projects in other sectors” (Abebe and Schaefer Citation2014, 15). This is in the mould of Lewis’s (Citation1954) role for manufacturing in industrialisation. It is this focus of the state on generating savings that has been a central factor in motivating the wholesale attention to a shift up from exports of hides to exports of finished leather goods (Abebe and Schaefer Citation2014). Notably, the state’s emphasis on exports pays minimal attention to shifts across the value chain domestically and therein attention to the domestic market and demand as part of industrial policy.

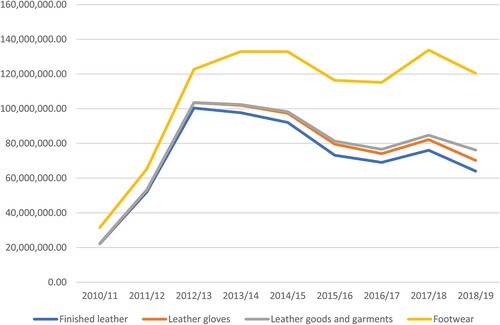

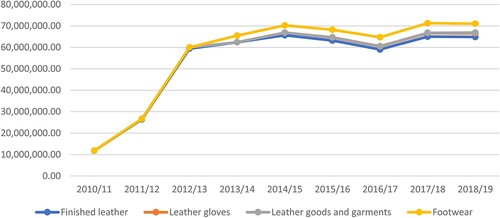

The institution of 150 per cent export taxes on hides and skin and crust leather energised the leather industry with a focus on domestic production for export (Fitawek and Kalaba Citation2016; Xiaoyang Citation2019). Exports of hides fell from highs of 87.3 million USD in 2007 to 301,000 USD in 2013 while exports of Ethiopian finished leather and leather goods increased from 18 million USD to 133 million USD (Fitawek and Kalaba Citation2016). The higher value of exports speaks, even cursorily, to the expected stability and higher value of manufactured goods exports. The leather industry is a growing source of foreign exchange revenues in leather and leather products exports that have been on an upward trend from 59 million USD in 2003 to 134 million USD in 2017/2018 and leather shoes as a subset going from almost 0 in 2002 to 49 million USD in 2017/2018 (See ; Abebe and Schaefer Citation2014). There is thus potential for increased higher value exports to generate foreign exchange to strengthen investment towards deepened structural and industrial change.

Volume and value of exports have been on an upward trend as seen in and . Leather goods exports are dominated by foreign firms and larger Ethiopian firms (also focused on local markets) with smaller and medium-sized Ethiopian firms serving local markets exclusively (Brautigam, Weis, et al. Citation2018). Lika (Citation2011, 120) finds from field-based research that local producers “have limited information about how to access and benefit from global trade”. KIDI (Citation2013, 450–453) draws on qualitative data on local exporters to explain their stilted participation in export growth due to premium prices for local leather, challenges with imported inputs and customs processes, lower capacity, scale and design and production know-how. This reinforces the significance of foreign investment in generating foreign exchange from trade increases as in and and potential support to industrial development.

Synergies in leather: production linkages and raw materials for leather manufacturing

Two roles emerge for the Ethiopian state that intersect with foreign capital: (i) its pursuit of industrial policy to simultaneously discourage exports of raw materials and encourage exports of finished leather and leather goods and (ii) the organisation of raw material supply and trade to manufacturers. These are examined as synergies between production linkages and raw materials. First, the 150 per cent export taxes on hides and skin and crust leather were designed to halt exports and channel raw materials to the domestic manufacturing sector. This shows the state’s role in driving resource transfers from agriculture to industry. Xiaoyang (Citation2019) highlights foreign firms procuring capital equipment to domestically produce and eventually export finished leather goods. These had previously only exported semi-processed goods. In fact, intersectoral linkages are not unidirectional but emerge also from manufacturing to lower value tanning activities. Abebe and Schaefer (Citation2014) and Xiaoyang (Citation2019) confirm these findings from their primary research on the sector with Chinese firms. In essence, industrial policy may strengthen both forward and backward production linkages.

Production linkages have been important for addressing raw material constraints in the leather sector. Oqubay (Citation2016, 211, 218) is clear on the strength of raw material provision to leather production particularly given the high levels of material intensity in the sector. The leather sector maintains a lower (though growing) level of import dependence of raw materials at 35 per cent of total costs (Gebreeyesus Citation2013). Although critical of the leather sector Oqubay (Citation2016, 201) reflects on the upward trend of finished leather goods production and export performance since 2009 following the export ban.

Second, the Ethiopian state’s commitments to the organisation of raw material supply and trade comprised institutional support to LIDI to enable its coordinating and training functions and more integrated policy formulation and implementation through focus on the raw material, livestock, sector (Brautigam, Weis, et al. Citation2018). LIDI has delivered on sectoral training and upskilling, data and information collation and flows between the government and private sector, organising incentives, improving bureaucratic performance and prioritising support to firms over regulation (Brautigam, Weis, et al. Citation2018; Oqubay Citation2016, 102–103, 236). There is also evidence of policymaking that considers integration between livestock and leather production with clear references to the Industrial Development Strategy and the 2015 Livestock Masterplan (Shapiro et al. Citation2015, 108). Despite these commitments, there are challenges with effectiveness in the transformation of the endowment of hides and skins to leather production due to poor organisation of livestock owners, suppliers and traders, poor quality of hides, disincentivising pricing structures and policy coordination (Oqubay Citation2016, 196, 237; Brautigam, Weis et al. Citation2018; Brautigam, Xiaoyang et al. Citation2018; Shapiro et al. Citation2015).

Foreign investors that are encouraged to build backward linkages can enhance and reinforce synergies between production linkages and raw materials. Abebe and Schaefer (Citation2014) highlight how skins that would normally have been disposed of due to inferior quality have been utilised because of technological innovations introduced by Chinese firms. Abebe, McMillan, and Serafinelli (Citation2018) suggest this as showing how production linkages drive lasting spill-over effects with upgraded input quality. Beyond input quality, there is action to enhance capacities for production and supply. Xiaoyang (Citation2019) reports that Chinese tanneries have undertaken training exercises on better approaches to local slaughtering to improve hide quality.

Brautigam, Weis et al. (Citation2018), Brautigam, Xiaoyang et al. (Citation2018) and Xiaoyang (Citation2019) are clear that in building synergies across production linkages and raw materials, the domestic private sector is at a disadvantage vis-à-vis their foreign, particularly Chinese, counterparts. This is due to their relatively poorer access to resources for investment, technology, participation in export zones and international market access.

Synergies in leather: consumption linkages and domestic industrial demand

The Ethiopian state does not appear to support synergies between consumption linkages and domestic industrial demand in relation to Chinese capital in the leather sector. Rather industrial policy has located local firms as competing with their foreign counterparts with trade policies to encourage production and exports of higher value leather goods (Oqubay Citation2016, 198). However, UNDP (Citation2018) notes that local demand has been a driver of Ethiopia’s impressive growth trajectory. Diao et al. (Citation2007) also show that increases in agricultural income are disproportionately expended on consumer industrial goods.

Former Commissioner of the Ethiopian Investment Commission, Mekuria (Citation2019) posits the neglect of the domestic private sector as due to the emphasis on foreign investment and export promotion. Industrial policy has tended not to situate domestic private capital in its central export-led industrialisation narrative. Oqubay (Citation2016, 100–101) demonstrates this in the Ethiopian National Export Coordination Committee’s stilted interactions with industrialists and their collectives. There is a latter-day recognition of this limitation with the homegrown economic reform agenda committing to promote import-competing industries and focus on the domestic market (FRE Citation2019, 27).

There is potential for synergies across consumption linkages and industrial demand constraints in the leather industry. This is especially given that leather goods are readily consumable within the domestic market. In general, improved performances from the leather sector reflect the domestic and foreign private sector as supplying different market bases. KIDI (Citation2013, 442) note that key foreign firm producers from Germany, Italy and China produce export quality shoes with domestic firms largely catering to domestic markets alongside continued imports.

There is evidence that the vibrant domestic market is increasingly serviced by less expensive imports from China.Footnote1 Alongside upward shifts in leather shoe export volume and value (see and ) that accompanied the entry of the major footwear producer and exporter Huajian, leather imports have also been expanding (Xiaoyang Citation2019; KIDI Citation2013, 414). Fitawek and Kalaba (Citation2016) show that leather goods imports are rising and UN Comtrade data confirms an almost four-fold increase from 2010 to 2018. This expansion in imports occurs alongside higher levels of production, from , and exports and therefore suggests that industrial policy has not supported synergies between domestic industrial demand and consumption linkages. It is on this note that Tesfaye (Citation2020, 64–65) acknowledges the potential disadvantage to domestic producers for local consumption and for exports due to growing Chinese footwear imports for domestic consumption and production for exports.

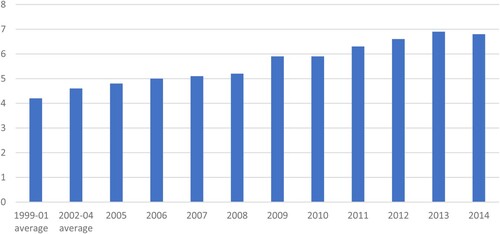

Figure 7. Leather shoe production (million pairs). Source: Food and Agricultural Organisation World statistical compendium for raw hides and skins, leather and leather footwear, 1999–2015.

There is a sense in which synergies across consumption linkages and industrial demand are not regarded as an industrial policy priority. The imports of leather goods from countries including China reflects some dissonance with the DSP narrative where domestic markets tend to be significant for locally produced manufactured goods in early stages of structural transformation.

Lines of influence, the state and international capital: underlying economic, social and political factors

Two contexts reflect the lines of influence that underpin the actions of the state as linked to international capital dynamics across economic, political and social spheres. The first is the Ethiopian state’s industrial policy emphasis on export promotion. There are underlying social and political factors that have underscored this direction. Clapham (Citation2018) suggests that the Ethiopian state considered foreign capital as potentially more controllable and best situated within an externally facing agenda of export promotion. This is especially in relation to a domestic capital class that has stronger societal links and vulnerability towards political tensions that can potentially challenge the occupants of the state apparatus. Meles Zenawi noted that the developmental state in Ethiopia, under the EPRDF, would best “keep the private sector at a distance … avoid business finance which would determine the short-term activities of the party” (De Waal Citation2018, 4). Pellerin (Citation2020) suggests the lack of interdependent relationships between the state and the domestic private sector.

The economic case for export promotion is anchored on prioritising foreign exchange savings for onward investment (Abebe and Schaefer Citation2014). The absence of a ready pot of resources that would serve as a base for irrigating other sectors of the economy has meant Ethiopia relies extensively on external sources. The precarity of the situation is not lost on the Ethiopian state. However, as mentioned there has been a reticence to embolden a domestic private capital constituency to diversify potential risks.

The Ethiopian state’s political interactions with international capital, at home and abroad, arise also in contestations of export taxes on hides and skin. These contestations have been pursued by political power play in global trade settings. Powerful raw hide importers in the global north, sought to pressure the Ethiopian state’s stance, given the risk to maintaining access to raw materials at more competitive rates. There were requests that the export tax increase be raised during Ethiopia’s negotiations to join the World Trade Organisation (Abebe and Schaefer Citation2014). Brautigam, Weis et al. (Citation2018) note that Italian authorities protested against its impact on access to raw materials for their tanneries by boycotting the All-Africa Leather Fair in Addis and attempting to undermine the exhibition of Ethiopian finished leather goods at a key global leather trade fair. Within Ethiopia also there were contentions with international capital given the harsh penalties meted out to Chinese-led tanneries despite their prominence and influence within the sector (Xiaoyang Citation2019). These power dynamics attended the state’s actions and suggest a degree of resilience in its deliberate and articulated position on export taxes on raw hides. Nonetheless, the 2020 reversal of these export taxes denotes a transitioned stance. The reversal has been recognised by the state and associations as necessary to address domestic producers’ performance as well as foreign capital inflows in upstream activities in the leather sector (Astatike Citation2020). It is vital to consider what future implications this may have for the hitherto impressive growth of exports of leather goods and how this intersects with the Medemer turn.

Another point of note is that the impetus to address social concerns and maintain stability informed state interventions in the aftermath of the implementation of the taxes on raw material exports. Brautigam, Weis et al. (Citation2018) highlight a targeted approach to technology transfer through the employment of foreign tannery workers to support local tanneries and enable vertical interlinkages.

The second observable set of concerns that illuminate lines of influence are around domestic versus foreign private capital interests. Foreign investment in tanneries was banned until 2006 due to social concerns about the dominance of foreign capital and the risk of displacement of domestic actors (Brautigam, Weis et al. Citation2018; Brautigam, Xiaoyang et al. Citation2018). A key factor was the domestic tanneries’ and footwear manufacturers’ interests influence on the state’s agenda through intensive lobbying (Oqubay Citation2016, 215). However, the economic case was put forward for improving input availability. This underscored the abolishment of the ban of foreign participation in tanneries given limited availability of high-quality leather for upgrading (Fitawek and Kalaba Citation2016). Beyond this, the core economic and political commitments to foreign investor interests on account of export promotion were likely significant factors driving this outcome.

The Ethiopian state reflects a wariness towards domestic hides and skins traders as undermining efficiency through pursuing deliberate subterfuge and price manipulation through artificially induced shortages (GRM International Citation2007, 33). Given the key role of international investors there are potential tensions with domestic private capital. Some foreign tanneries have voiced requirements for state support to undermine local traders notably to provide higher quality hides and better pricing (Brautigam, Weis et al. Citation2018).

We return to the research question, on how and to what extent interdependencies exist and function across the state and private capital, especially Chinese capital, within industrial development and therein movements between the agricultural and manufacturing sectors in the leather sector. In response, first the deployment of the IPE-enhanced DSP elucidates the interactions between the state and Chinese foreign capital and domestic capital on industrial upgrading across hides and skin, tanneries and finished leather goods. On resource movements between agriculture and manufacturing, there are synergies between fiscal transfers from the state in foregone revenues and the generation of foreign exchange from exports driven by foreign capital; synergies between forward as well as backwardFootnote2 production linkages and addressing raw material constraints, with activity from domestic actors and increasing participation by foreign firms; and challenges regarding the synergies across consumption linkages and addressing industrial domestic demand.

Second, the IPE-enhanced DSP reveals the interdependencies between the state and private capital in the lines of influence across economic, political and social factors in the focus on exports as key to industrial policy and tensions between foreign and domestic private capital. Meles Zenawi raised the limitations of excluding society, beyond the state-market dichotomy, in developmental state debates (De Waal Citation2018). Given the social and political unrest linked to the socio-economic transformation agenda in 2018, this is a valid consideration. This analysis has drawn attention also to the state’s response to social pressure in attempts to restrict foreign capital participation in lower economic value activities, such as leather production as well as the economic pressures, limited raw material supply, that undermined this effort.

Conclusions

In responding to the central research question, this article has proposed and deployed the IPE-enhanced DSP. This IPE-enhanced DSP has highlighted two sets of dynamics, synergies and lines of influence. These explain the interactions between the state and private capital, especially international capital, in industrial development.

This article has offered a set of starting points for understanding how a range of contexts may speak to an emerging and evolving idea of developmental statehood that is relevant more widely. Ethiopia has allowed us to consider concretely and conceptually how IPE dynamics impinge on developmental statehood that has influenced industrial development typified by increasing production and exports of finished manufactured goods. Other cases will bring with them new sets of dimensions for consideration that should enrich the DSP itself, through pattern building across time, space and issue. This is a dynamic contribution to the developmental state literature that conceptually centres the interactions between states and the international sphere which has been largely unaddressed until now.

The Ethiopian case distils the significance of international capital in the discourse of developmental states that has been observed also across historical exemplars such as Taiwan and South Korea. The IPE-enhanced DSP shows that interactions between international capital and state industrial policy have informed the dynamics of industrial upgrading. The article’s key finding is that in the Ethiopian leather sector, domestic private capital and, more recently, international capital have been important for addressing raw materials requirements for manufacturing leather and finished leather goods. Due to the industrial policy focus on exports which is dominated by international capital, building synergies across domestic industrial demand and local consumption of manufactured goods is neglected as an element of industrial policy and therein the role of domestic private capital. This dynamic has been highlighted by critical political economy scholars as reinforcing core–periphery dynamics particularly in how value as articulated by international trade and global production networks can undermine periphery contexts (Ghosh Citation2019; Ake Citation1982; Amin Citation1974). This article offers an important critique to the IPE turn in aspects of global value chain and production network analyses that deprioritise national contexts and therein local development processes and outcomes.

The DSP has traditionally emphasised domestic demand as part of industrial policy, particularly in early structural transformation. However, the interactions between international capital and state industrial policy of export promotion in Ethiopia appear to deviate from this path. Amin (Citation1974, 9) has long criticised the logic of development and unequal exchange that reinforces the neglect of African internal markets by prioritising extracontinental exports. This study evidences the need, and offers a framework, for critical analyses of African political economy realities in relation to international dynamics. This concern endures as African contexts now face a contemporary challenge in the drive for insertion into industrial development processes within global value chains and doing so potentially on the terms of international capital.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Zekarias Abebe for research assistance and to Professor Medhane Tadesse, Dr Belachew Mekuria and ALC Research Cluster Six colleagues for insightful comments on earlier versions of the article. She is grateful to two anonymous reviewers for very thorough and thoughtful comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eka Ikpe

Dr Eka Ikpe is Senior Lecturer and Deputy Director, African Leadership Centre, King’s College London.

Notes

1 Although domestic producers have emerged as more competitive at times, such as when Birr devaluation has effected price pressures on imports (Oqubay Citation2016, 215).

2 Hirschman’s revolutionary idea of backward linkages, i.e. industrialisation pulling along the primary sector has been considered to be socially important by softening the impact of disequilibria that can attend transition (Bianchi Citation2004).

References

- Abebe, Z. B. 2018. “Developmental State and Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia: Is Leadership the Missing Link?” Leadership & Developing Societies 3 (1): 95–127.

- Abebe, G., M. S. McMillan, and M. Serafinelli. 2018. Foreign Direct Investment and Knowledge Diffusion in Poor Locations: Evidence from Ethiopia. Working Article No. 24461. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Abebe, G., and F. Schaefer. 2014. High Hopes and Limited Successes: Experimenting with Industrial Polices in the Leather Industry in Ethiopia. Working Article No. 011. Ethiopian Development Research Institute.

- Ake, C. 1982. Social Sciences as Imperialism: The Theory of Political Development. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press.

- Akyüz, Y., H.-J. Chang, and R. S. Kozul Wright. 1998. “New Perspectives on East Asian Development.” Journal of Development Studies 34 (6): 4–36.

- Amin, S. 1974. “Accumulation and Development: A Theoretical Model.” Review of African Political Economy 1 (1): 9–26.

- Amsden, A. H. 1989. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Astatike, D. 2020. “Ethiopia Lifts Tax on Semi-Finished Leather Export.” Ethiopia Capital, January 13. https://www.capitalethiopia.com/capital/ethiopia-lifts-tax-on-semi-finished-leather-export/.

- Bezawagaw, M., N. Dihel, M. T. Geiger, and K. Z. Getachew. 2018. Ethiopia Economic Update: The Inescapable Manufacturing Services Nexus: Exploring the Potential of Distribution Services. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/811791526447120021/The-inescapable-manufacturing-services-nexus-exploring-the-potentialof-distribution-services.

- Bianchi, A. M. 2004. “Albert Hirschman in Latin America: Notes on Hirschman’s Trilogy on Economic Development”. In Proceedings of the 32nd Brazilian Economics Meeting, 004, ANPEC–Brazilian Association of Graduate Programs in Economics, João Pessoa.

- Bowles, P. 2020. “The Developmental State and the Study of Globalizations.” Globalizations 17 (8): 1–18.

- Brautigam, D., T. Weis, and X. Tang. 2018. “Latent Advantage, Complex Challenges: Industrial Policy and Chinese Linkages in Ethiopia's Leather Sector.” China Economic Review 48: 158–169.

- Brautigam, D., T. Xiaoyang, and X. Ying. 2018. What Kinds of Chinese “Geese” Are Flying to Africa? Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Working Article No. 2018/17. Washington, DC: China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.

- CARI (China-Africa Research Initiative Database). 2018. Data on Chinese Loans and Foreign Direct Investment Data. Johns Hopkins University. http://www.sais-cari.org/data.

- Chinigò, D. 2015. “Historicising Agrarian Transformation. Agricultural Commercialisation and Social Differentiation in Wolaita, Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 9 (2): 193–211.

- Clapham, C. 2018. “The Ethiopian Developmental State.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6): 1151–1165.

- Cochrane, L., and Y. W. Bekele. 2018a. “Average Crop Yield (2001–2017) in Ethiopia: Trends at National, Regional and Zonal Levels.” Data in Brief 16: 10.

- Cochrane, L., and Y. W. Bekele. 2018b. “Contextualizing Narratives of Economic Growth and Navigating Problematic Data: Economic Trends in Ethiopia (1999–2017).” Economies 6 (4): 64.

- De Waal, A. 2018. The Future of Ethiopia: Developmental State or Political Marketplace? Somerville, MA: World Peace Foundation.

- Diao, X., B. Fekadu, S. Haggblade, A. S. Taffesse, K. Wamisho, and B. Yu. 2007. Agricultural Growth Linkages in Ethiopia: Estimates Using Fixed and Flexible Price Models. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Feyissa, D. 2011. “Aid Negotiation: The Uneasy “Partnership” Between EPRDF and the Donors.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5 (4): 788–817.

- Fine, B. 2007. “State, Development and Inequality: The Curious Incidence of the Developmental State in the Night-Time.” Presented at the Sanpad Conference, Durban, June 26–30, Durban, South Africa.

- Fitawek, W. B., and M. Kalaba. 2016. “The Role of Trade Policy on Ethiopia’s Leather Industry: Effect of Export Tax on Competitiveness.” Presented at the 5th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists, September 23–26, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- FRE (Federal Republic of Ethiopia). 2019. A Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda: A Pathway to Prosperity. Addis Ababa: Office of the Prime Minister.

- Gagliardone, I. 2014. “New Media and the Developmental State in Ethiopia.” African Affairs 113 (451): 279–299.

- Gebreeyesus, M. 2013. Industrial Policy and Development in Ethiopia: Evolution and Present Experimentation. WIDER Working Article No. 2013/125. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/industrial-policy-and-development-ethiopia.

- Gelan, A. 2019. “Ethiopia’s ‘Homegrown’ Economic Reform: An Afterthought.” Addis Fortune. October 12. https://addisfortune.com/ethiopias-homegrown-economic-reform-an-afterthought/.

- Gereffi, G. 2014. “Global Value Chains in a Post-Washington Consensus World.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (1): 9–37.

- Gerschenkron, A. 1962. Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Ghosh, J. 2019. “A Brave New World, or the Same Old Story with New Characters?” Development and Change 50 (2): 379–393.

- Giannecchini, P., and I. Taylor. 2018. “The Eastern Industrial Zone in Ethiopia: Catalyst for Development?” Geoforum 88: 28–35.

- GRM International. 2007. Livestock Development Master Plan Study for Government of Ethiopia. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and African Development Bank. http://www.igadhost.com/igaddata/docs/LDMPS_Phase%20I_Vol.K_Hides%20&%20Skins.pdf.

- Hailu Woldegebrael, E. 2018. “The Materialization of ‘Developmental State’ in Ethiopia: Insights from the Gibe III Hydroelectric Development Project Regime, Omo Valley.” L’Espace Politique. Revue en ligne de géographie politique et de géopolitique (35).

- Hauge, J. 2020. “Industrial Policy in the Era of Global Value Chains: Towards a Developmentalist Framework Drawing on the Industrialisation Experiences of South Korea and Taiwan.” The World Economy 43 (8): 2070–2092.

- Hirschman, A. O. 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Hirschman, A. O. 1981. “A Generalized Linkage Approach to Development, with Special Reference to Staples.” In Essays in Trespassing: Economics to Politics and Beyond, edited by A. O. Hirschman, 59–97. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Horner, R., and M. Alford. 2019. The Roles of the State in Global Value Chains: An Update and Emerging Agenda. Global Development Institute Working Article Series 2019-036. Global Development Institute, University of Manchester.

- Ikpe, E. 2013. “Lessons for Nigeria from Developmental States: The Role of Agriculture in Structural Transformation.” In Beyond the Developmental State: Industrial Policy Into the 21st Century, edited by B. Fine, J. Saraswati, and D. Tavasci, 187–215. London: Pluto Press.

- Ikpe, E. 2018. “The Enduring Relevance of the Developmental State Paradigm Across Space and Time: Lessons for Africa on Structural Transformation and Agriculture in Oil-Rich Contexts.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 53 (5): 764–781.

- Jerven, M. 2013. Poor Numbers: How We Are Misled by African Development Statistics and What to Do About It. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- KIDI (Korea International Development Institute). 2013. GTP and Sector Analysis, Business Cases and Policy, Recommendations Based on the Korean experiences. Korea International Cooperation Agency.

- Lashitew, A. 2019. “Ethiopia’s Newly Unified Ruling Party Pivots to a Liberal Political Economy.” Africa in Focus. December 6. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2019/12/06/ethiopias-newly-unified-ruling-party-pivots-to-a-liberal-political-economy/.

- Lefort, R. 2012. “Free Market Economy, ‘Developmental State' and Party-State Hegemony in Ethiopia: The Case of the ‘Model Farmers.'” The Journal of Modern African Studies 50 (4): 681–706.

- Lewis, W. A. 1954. “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour.” The Manchester School 22 (2): 139–191.

- Lika, T. 2011. “Inter-Firm Relationships and Governance Structures: A Study of the Ethiopian Leather and Leather Products Industry Value Chain.” Ethiopian Journal of the Social Sciences and Humanities 7 (1–2): 113–124.

- Lin, J. Y. 2012. New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development and Policy. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Mandefro, H. 2016. “Politics by Numbers: Poverty Reduction Discourse, Contestations and Regime Legitimacy in Ethiopia.” International Review of Sociology 26 (3): 386–406.

- Mariam, A. 2019. “Innovating the Developmental State Through Homegrown Economic Reform?” Addis Fortune. October 12. https://addisfortune.com/innovating-the-developmental-state-through-homegrown-economic-reform/.

- Masterman, M. 1970. “The Nature of a Paradigm.” In Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, edited by I. Lakatos and A. Musgrave, 59–90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mekuria, B. 2019. “Economic Analysis: Ethiopia’s Developmental State: Dead or Alive?” Addis Standard, May 29. http://addisstandard.com/economic-analysis-ethiopias-developmental-state-dead-or-alive/.

- Mkandawire, T. 2001. “Thinking About Developmental States in Africa.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 25 (3): 289–314.

- NBE (National Bank of Ethiopia). 2017. Annual Report 2016–17. Addis Ababa: National Bank of Ethiopia. http://www.nbebank.com/pdf/annualbulletin/NBE%20Annual%20report%202016-2017/NBE%20Annual%20Report%202016-2017.pdf.

- Nem Singh, J., and J. S. Ovadia. 2018. “The Theory and Practice of Building Developmental States in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6): 1033–1055.

- Ohno, K. 2009. Ethiopia: Political Regime and Development Policies. GRIPS Development Forum, June 2009. http://www.grips.ac.jp/forum/af-growth/support_ethiopia/document/Jun09_DD&ADLI_10E.pdf.

- Oqubay, A. 2016. Made in Africa: Industrial Policy in Ethiopia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oqubay, A. 2019. “The Structure and Performance of the Ethiopian Manufacturing Sector.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy, edited by F. Cheru, C. Cramer, and A. Oqubay, 630–650. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ovadia, J. S., and C. Wolf. 2018. “Studying the Developmental State: Theory and Method in Research on Industrial Policy and State-Led Development in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6): 1056–1076.

- Pellerin, C. L. 2020. “The Aspiring Developmental State and Business Associations in Ethiopia–(Dis-) Embedded Autonomy?” Journal of Modern African Studies 57 (4): 589–612.

- Planel, S. 2014. “A View of a Bureaucratic Developmental State: Local Governance and Agricultural Extension in Rural Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 8 (3): 420–437.

- Radice, H. 2010. “Book Review: Capital, Class and Crisis: The False Dichotomy of Market and State: An Extended Book Review.” Capital & Class 34 (1): 137–142.

- Samaro, Z. 2019. “Reform Agenda Neither Homegrown Nor Pathway to Prosperity.” Addis Fortune, September 21. https://addisfortune.news/reform-agenda-neither-homegrown-nor-pathway-to-prosperity/.

- Sandefur, J., and A. Glassman. 2015. “The Political Economy of Bad Data: Evidence from African Survey and Administrative Statistics.” Journal of Development Studies 51 (2): 116–132.

- Shapiro, B. I., G. Gebru, S. Desta, A. Negassa, K. Nigussie, G. Aboset, and H. Mechal. 2015. Ethiopia Livestock Master Plan. ILRI Project Report. Nairobi: International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/68037/lmp_roadmaps.pdf?sequence=1.

- Shiferaw, A. 2017. Productive Capacity and Economic Growth in Ethiopia. CDP Background Article No. 34 ST/ESA/2017/CDP/34 United Nations. Department of Economics and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/CDP-bp-2017-34.pdf.

- Stiglitz, J. E. 2008. “Is There a Post-Washington Consensus?” In The Washington Consensus Reconsidered: Towards a New Global Governance, edited by N. Serra and J. E. Stiglitz, 41–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tesfaye, A. 2020. China in Ethiopia: The Long-Term Perspective. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Thorbecke, E. 1979. “Agricultural Development.” In Economic Growth and Structural Change in Taiwan: The Postwar Experience of the Republic of China, edited by W. Galenson. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Tsai, M. C. 2002. “Taming a Leviathan: Geopolitics, State Power and the Making of a Development Regime in Taiwan.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 23 (1): 127–153.

- UNCTAD. 2002. Investment and Innovation Policy Review Ethiopia. Geneva: UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/en/docs/poiteipcm4.en.pdf.

- UNDP. 2018. “Ethiopia’s Progress Towards Eradicating Poverty.” Article Presented to the Inter-Agency Group Meeting On the “Implementation of the Third United Nations Decade for the Eradication of Poverty (2018–2027).” Addis Ababa: UNDP. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/CDP-bp-2017-34.pdf.

- UNIDO. 2018. Industrial Park Development in Ethiopia: Case Study Report. Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development Working Article Series WP 21 2018. Vienna: UNIDO.

- Wade, R. 1990. Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Weiss, L., and E. Thurbon. 2020. “Developmental State or Economic Statecraft? Where, Why and How the Difference Matters.” New Political Economy 26 (3): 1–18.

- World Bank. 2018. Ethiopia Economic Update – the Inescapable Manufacturing Services Nexus: Exploring the Potential of Distribution Services. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- World Bank. 2019. Global Economic Prospects January 2019 – Sub-Saharan Africa Chapter. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- World Bank. 2020. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Xiaoyang, T. 2019. Export, Employment, or Productivity? Chinese Investments in Ethiopia’s Leather and Leather Product Sectors. Working Article No. 2019/32. Washington, DC: China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.

- Zenawi, M. 2012. “States and Markets: Neoliberal Limitations and the Case for a Developmental State.” In Good Growth and Governance in Africa: Rethinking Development Strategies, edited by A. Noman, K. Botchwey, H. Stein, and J. E. Stiglitz, 140–174. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zenawi, M. Forthcoming. African Development: Dead Ends and New Beginnings. http://www.meleszenawi.com/african-development-deadends-and-new-biginnings-by-meles-zenawi/.