ABSTRACT

Powerful yet hidden juridical dimensions to Official Development Assistance (ODA) exist whose quality and relationship to law remain overlooked. Donors’ reliance on bureaucratic and technocratic governance instruments to govern ODA, institutionalises permanent co-governance within aid-recipient states in ways that remain invisible to recipient states’ ordinary laws and institutions (governance of ODA). Meanwhile, ODA-leveraged, donor-led legal and institutional reform, provides donors with opportunity for executive intervention in aid-recipient domestic affairs (governance by ODA). Approaching ODA as a juridical field through a meso-Tanzania-level analysis of donor governance, this article contributes new conceptual and empirical insights to the relationship between law, governance, and ODA.

RÉSUMÉ

Il existe des dimensions juridiques puissantes mais cachées de l'aide publique au développement (l’APD), dont la qualité et la relation au droit restent négligées. Le recours par les donateurs à des instruments de gouvernance bureaucratiques et technocratiques pour régir l'APD institutionnalise une co-gouvernance permanente au sein des États bénéficiaires de l'aide d'une manière qui reste invisible pour leurs lois et institutions ordinaires (gouvernance de l'APD). Parallèlement, les réformes juridiques et institutionnelles menées par les donateurs et financées par l'APD offrent aux donateurs la possibilité d'intervention exécutive dans les affaires intérieures des bénéficiaires de l'aide (gouvernance par l'APD). En abordant l'APD comme un champ juridique par le biais d'une analyse de la gouvernance des donateurs au niveau méso-tanzanien, cet article apporte de nouveaux éclairages conceptuels et empiriques sur la relation entre le droit, la gouvernance et l'APD.

Introduction

The relationship between law and the international governance of Official Development AssistanceFootnote1 (ODA or public concessional development finance, popularly called development aid) remains complex and is underexplored. At first glance, law’s presence in the governance of ODA appears highly inconsistent, and even incongruous with ODA’s normative assertions on the partnership nature of the aid relationship. On the former, though some donor states’ implementation of ODA is guided by a dedicated domestic law, this is not typical (Dann Citation2013). On the latter, a divergence is emerging between the legally-backed governance approach of the recognised international locus of authority on ODA – the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Global Partnership on Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC) (a multi-stakeholder initiative designed to specifically promote and monitor commitments to ‘inclusive partnerships’ and ‘mutual accountability’ in international development). Recent data from the ‘soft-law’ GPEDC suggests that donors’ ‘alignment’ with aid-recipient states’ development objectives and monitoring systems is declining (OECD Citation2019), while other analyses suggest that the GPEDC itself enjoys only partial and waning influence (Brown Citation2020; Lundsgaarde and Engberg-Pedersen Citation2019). Meanwhile, the DAC – who can issue formal Recommendations to its 30 donor Members on their implementation of ODA – relies on a donor- and data-centric disclosure approach to donor implementation of ODA that makes the tracing and monitoring of the manifestation and measurement of power in donor-recipient state relationships impossible. Unlike with international development finance institutions, ODA between donor and aid-recipient states is usually governed by high-level instruments of financial agreement that are largely diplomatic in nature and purpose, ranging from letters of intent to more formal (yet still not formally legal) Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs).Footnote2 With confidentiality as their signature feature, it becomes impossible to ignore the political leverage that the context of their use, and legal quality of this kind of agreement invites (Aust Citation2012). Thus, the role of and for law in the international governance of ODA might, at first glance, appear ambiguous at best.

It is not surprising then, that legal scholarship on the international governance of ODA has examined ODA’s governance from a variety of methodological approaches and loci, since recognition within legal scholarship of development finance as an autonomous area of international relations (Davis Citation2009). Several contributions draw from Global Administrative Law to propose thoughtful responses for donor governance frameworks at national and international levels to address challenges of transparency and accountability (Dann Citation2013; Reigner Citation2015). Unsurprisingly, the hidden legal dimensions of the World Bank’s role and approach as key international donor and development actor predominate, with its approach to law in development (Rittich Citation2002, Citation2006), the Bank’s application of its ‘Safeguard Policies’ in development projects (Jokubauskaite [Citation2018], Citation2019; de Moerloose Citation2020), and conditionality (Tan Citation2011) attracting particular attention. Welcome scrutiny of the frequently overlooked private law dimensions to the activities of public development finance actors (Bhatt Citation2020), as well as to the emergence of new ‘hybrid’ development actors such as multistakeholder partnerships (Türkelli Citation2021) has also recently emerged. In addition, other legal research has examined the significance to law in, and to governance of ODA, of mundane, if highly influential dimensions including use of epistemological instruments and practices that are central to the promulgation of ODA-backed ideas about the appropriate role for laws, institutions (McHugh-Russell Citation2021, this issue), and for actors such as NGOs and communities in development (Jokubauskaite and Rosatti Citation2021, this issue); the centrality of data and information technologies to governance through development finance (Krever Citation2013); the roles of legal professionals (Van Den Meerssche Citation2021), and particular institutional discourses on law within influential development finance institutions (Sarfaty Citation2012) such as the World Bank, as well as new policy orientations in, and through the funding of development (such as financialisation) that ODA helps bring forth (Karwowski Citation2021; OECD Citation2021).

This article contributes to and expands this growing body of legal scholarship in three ways. First, I reveal how reform of aid-recipient state laws and institutions is central to donor governance of ODA, but how this is made legally and politically invisible to recipient state domestic democratic institutions through its rationalisation and formalisation via ‘soft law’ technocratic governance instruments and bureaucratic practices. I term this approach a mode of juridical governance that effectively institutionalises permanent co- governance by donors within the aid-recipient state. Thus, a very real if subtle legal link exists between how ODA is governed and how ODA governs – where in the former, formal law appears largely absent, while in the latter, legal and institutional reform are central. Secondly, I bring legal insights to bear on a legally invisible, politically hidden yet highly influential site and level of ODA governance that uniquely traverses the international/national, and donor/recipient state domains previously framed by legal scholars as separate and distinct. This site is that of institutionalised international donor co-ordination that operates at national level within the aid-recipient state, and I term this ‘meso-level’ governance. Thirdly, I frame the international governance of ODA as a juridical field to foreground, reveal and trace the layered and complex legal dimensions to ODA’s governance role and qualities in ways that usually remain legally invisible or ‘adjacent’ to law. A key enabling feature of this dual governance of/by dynamic is the weave of law and governance instruments, technologies, and practices that, underpinned by a pattern of historically engrained structural dynamics, constitute ODA as a cohesive juridical field. In doing so, though I draw from some aspects of Bourdieu’s thinking in the ‘The Force of Law’ (Citation1987), my approach here is different.Footnote3

This article focuses on the meso-level ODA governance interface between international donors (as a group) and an individual aid-recipient state (United Republic of Tanzania and Zanzibar, henceforth Tanzania). It draws from reflections on data gathered through empirical research in the European Union and East Africa in 2015 (in Tanzania; in the East African Community institution; at the Third UN Conference on Financing for Development held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia), and on reform of Tanzania’s mining laws that occurred in 2017. This article proceeds as follows. In the following section I describe the rationale for approaching ODA as a juridical field, and my approach to this. I then examine different aspects of meso-level governance of ODA, tracing how one donor’s plans for ODA-backed reform of Tanzania’s public finances management appears linked to Tanzania’s controversial 2017 reform of its mining code. This example illustrates how the apolitical managerial framing of public governance by donors, implemented via a thick web of technocratic governance instruments and institutionalised bureaucratic mechanisms (section four), institutionalises donor governance of ODA within the Tanzanian state in ways that are distant from Tanzanian democratic institutional scrutiny. In section five, I step back from this detailed institutional analysis to trace the presence, patterns, and centrality of hidden legal logics in ODA’s governance by donors. Their potency and influence extends far beyond the meso-level explored here because of the presence of hidden scalar and temporal dynamics. The article concludes with a reflection on further possibilities to legal analysis of ODA governance that a focus on the juridical can bring.

Official Development Assistance as a juridical field

Mapping a complex transnational legal and governance landscape and its governance effects invites consideration of varied methodological approaches from legal and international relations scholars (Ruhl and Katz Citation2015; Pattberg et al. Citation2014; Gehring Citation2004). In the following paragraphs, I describe why ODA can usefully be framed as a juridical field, and how this foregrounds dimensions to its governance that earlier research has missed.

Historically, ODA has had an influential instrumental role in implementing development policy through successive iterations from modernisation theory to structural adjustment, the Washington Consensus and post-Washington’s neoliberal foundations, and latterly, via ideas strongly resonant with financialisation (Watts and Scales Citation2020). ODA’s ability to traverse multiple levels, policy spheres, and public and private actors, relies on a set of recognised and recognisable institutional governance practices that include a strongly prescriptive and highly normative discourse on development, underpinned by concepts such as development effectiveness, partnership, and country ownership. At the international level, normative iterations on development are promulgated through digests such as the annual World Bank’s flagship World Development Report and OECD DAC’s Development Co-operation Report, and translated respectively into practice via the Bank’s lending and advisory services (Knack et al. Citation2020), and Recommendations, Guidelines, and periodic peer review of donor practices by the DAC. At the national level, these are translated, prioritised and implemented through a thick web of technocratic governance instruments that include time-bound country, area, and sectoral plans (for example, donors’ ‘Country Strategy Plan’ and recipient states’ ‘National Development Plan’), along with periodic reviews, evaluations and specialist research papers in which data, indicators, indexes, and expertise are key. Together, these constitute a transnational ‘infrastructure of measurement’ (Merry Citation2019, 146), through which deeply political decisions on development are masked by their articulation through seemingly neutral, objective and ‘scientific’ data (Fukuda-Parr and McNeill Citation2019). Bureaucratic instruments such as meeting minutes, progress reports etc. produced according to a common format, along with bureaucratic mechanisms such as the overlapping donor co-ordination groups, working groups, advisory groups, taskforces etc., and their highly ritualised working methods, further operationalise and legitimise this political work through mundane means. Backed up by donors’ individual chains of command and standard ways of working, including decision-making, communications, levels of responsibility, teamwork and professional self-identity, these work routines are easily replicated – and recognisable – across different donors and recipient states. Anchoring both these bureaucratic mechanisms and technocratic instruments is a twin logic of local relevance (development interventions must respond to sectoral or national development ‘challenges’) matched with universal recognition (the rationale, authority and legitimacy of the interventions is recognised by a wide variety of national and international development stakeholders). These are further consolidated through reliance on a distinct temporal dimension intrinsic to the implementation of ODA. Thus, repetition of the annual, three- and five-year plans, with reviews, evaluations etc. are central to the authority and legitimacy of ODA’s governance.

As I show in detail in the next section, the nature of how ODA is governed results in the evolution of a highly juridical – but not formally legal – modality of governance. In the context of this article on ODA, I mean the term ‘juridical’ to refer to practices of governance that include the following four features. First, there is the presence of a recognised Authority with Executive powers – there is an entity who makes determinative decisions (donors individually and as a group) – and there is a community (the recipient state and its public administration) that recognises this Authority as such. Secondly, there is an expectation of determinative decision-making through methods and practices that are recognisable to that Executive Authority as legitimate. These include the availability of appropriate ‘facts’ that function as ‘evidence’, from which a kind of ‘fact pattern’ is discerned, to which a particular kind of normative reasoning is applied, aimed at progressing a particular model of development. These ‘facts’ have strong ontological and epistemic dimensions, and their authority relies to a considerable extent on their perception of being scientific and objective through their representation via calculative technologies involving compilations of numbers and ‘scientific’ data such as indicators, indexes and models. Thirdly, a differentiated approach to the subjectivities and agency of donors and recipient states is created, where donors are awarded more authority in development decision-making than aid-recipient states, and this differentiated relationship is not in conflict with the law of that community. Finally, there is the presence of an underlying risk of coercion ‘that cannot be fully understood, justified and curtailed by practical reasoning’ (Schotel Citation2016, 214). This feature aims at capturing the ever-present, unequal power dynamic between donor and aid-recipient state. Though this approach to the juridical dimensions of ODA holds some resonance with Bourdieu’s explication of the ontological and epistemological dimensions of the juridical field (for example, through ‘the symbolic power of naming’ and interpretation (Bourdieu Citation1987, 837), practiced through long-established procedures and acts of codification, formulation, formalisation, neutralisation, and systematisation, (ibid., 840–841) and enacted through ‘extraordinarily’ elastic texts (Bourdieu Citation1987, 827)), my framing and analysis of ODA as a juridical field in this article excludes attention to the professional groups active in the implementation of ODA.

In the next section, I trace these juridical dimensions to ODA through a meso-level analysis of a key ODA modality (Budget Support) and object of donor intervention (Public Financial Management reform). Budget Support is the form of aid commonly associated with recipient state ownership (Swedlund and Lierl Citation2019) and is the preferred option of recipient state governments. It is also an ODA modality that frequently encompasses financial support for Technical Assistance (Gibson et al. Citation2015) and for Capacity Building (Cox and Norrington-Davies Citation2019) aimed at the recipient state. Both are central to donor identification, implementation, and monitoring of recipient state institutional reform (Easterly and Pfutze Citation2008). The significance of reform of Public Financial Management as an especially potent sector where donors can more effectively shape reform priorities of aid recipient states through ODA, has only recently been recognised (Masaki et al. Citation2021).

Public financial management reform and the right to determine the law

In 2015–2016, major reserves of gas were discovered offshore in Tanzania, near to Dar es Salaam and Mozambique. In July 2017, the Parliament of Tanzania passed three new laws, amending previous laws governing the natural resources sector.Footnote4 Notably, the preamble to the Permanent Sovereignty Act recites articles of the Constitution of Tanzania, including those that concern the Government's duty to protect natural resources for the benefit of the people and use of the country's natural resources for the common good of the people.Footnote5 It also includes reference to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights,Footnote6 and references the 1962 UN General Assembly Resolution on Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources and the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States (1974) in its Schedules.

Together, these Acts introduced significant changes to the national governance of oil and gas, empowering the Tanzanian National Assembly to direct the Government to re-negotiate contracts relating to the development of natural resources (including minerals and oil and gas) that contain ‘unconscionable terms’, including those entered into before the amendments come into force. Though ‘unconscionable’ is not strictly defined in the law, it included provisions intended to restrict the right of the State to exercise full or permanent sovereignty over its wealth, natural resources, or economic activity; restrict the right of the State to exercise authority over foreign investment within the country and in accordance with the laws of Tanzania that were inequitable and onerous to the State; restrict periodic review of the arrangement or agreement; secure preferential treatment designed to create a separate legal regime to be applied for the benefit of a particular investor, or deprive the people of Tanzania of economic benefits derived from subjecting natural wealth and resources to beneficiationFootnote7 in the country.

The new legislation increased royalties and rights to the Tanzanian Government in several ways, giving it a non-dilutable free carried interest of no less than 16% in the capital of mining companies that have mining operations under a mining licence or special mining licence in Tanzania; rights to acquire up to 50% of any mining asset commensurate with the value of tax benefits provided to the owner of that asset, while increasing revenue royalties from 4% to 6% on gold, copper, silver and platinum exports, and from 4% to 5% on uranium exports. Furthermore, Section 28 of the Amendments Act added several new provisions on local content, obliging mineral-rights holders to give preferences to goods and services produced by Tanzanian companies and by Tanzanian citizens (Woodroffe et al. Citation2017). Of special interest to states with bilateral investment treaties with Tanzania is a provision that prohibits adjudication of disputes relating to natural resources by ‘any foreign court or tribunal’, and provides that all disputes arising from extraction, exploitation or acquisition and use of natural wealth and resources shall be adjudicated by ‘judicial bodies or other organs established in the United Republic and accordance with laws of Tanzania’.Footnote8

These legislative developments prompted the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID)Footnote9 to note in its ‘Business Case’ for ‘Strengthening Public Financial Management’ supported by its ODA to Tanzania that:

With the advent of the new government under President Magufuli, Tanzania is undergoing a political and economic transition that is quite disruptive … . [R]adical measures being taken to review contractual arrangements with the private sector pose significant risks for the investment climate . … [T]he new economic policy on natural resources and mineral wealth has weakened investor confidence. The aggressive approach to tax collection and the prevailing policy uncertainty is affecting business sentiment. The fact that there are limited opportunities for the private sector to engage with the government on policy issues has aggravated the situation. (DFID Citation2017, 4)

The deeply political nature of sectoral intervention by donors in Public Financial Management Reform is masked by its technocratic framing in key planning documents, further reinforced by a strong visual aesthetic contained in key documents. Thus, the Five Year Medium-Term Strategic Plan for the Public Finance Management Reform Programme (PFMRP) Phase V (2017/18–2021/22) for Tanzania and Zanzibar is a comprehensive, five-year reform programme covering macro-economic management (fiscal and tax policies); financing the budget; processes for budget preparation, execution, accounting, and reporting; financial accountability systems external oversight, and reforms of local government revenues and expenditures. This sensitive and sweeping area of recipient domestic policy, and the range and depth of donor scrutiny and intervention therein, are easily elided by their presentation as a sixteen-page table of data. The table consists of seven ‘PFM Challenge’ areas, with forty-three sub-challenges, where initiatives to address these are described via columns titled ‘PFMRP Objectives’, ‘Baseline (2017)’, ‘Result (2022)’ and ‘Responsibility (this refers to the government department responsible e.g. Budget Division, Internal Auditor General’s Division, Accountant General etc.)’ (GOT Citation2017, 50–66).

Public financial reform is thus presented as an essentially technical exercise, denuding it of its deeply political character, making the identification of its underlying financial and legal logic, as well as its accessibility for domestic scrutiny, far more challenging. It is notable that the legal and regulatory framework on public financial management in Tanzania has been significantly strengthened over the previous 10–15 years with the introduction of a Public Finance Act (2004), a Public Audit Act (2008), a Public Procurement Act (2011), a Budget Act (2015) and a Value Added Tax Act (2015). Part II 5 (2) (c) of the Public Finance Act vests the National Assembly, via the Minister for Finance and Treasury, with responsibility for ‘the control … over such resources and public moneys … and (that) transparent systems are established and maintained which (i) provide a full account to the National Assembly for the use of resources and public moneys; (ii) ensure the exercise of regularity and propriety in the handling and expenditure of resources and public money.’

This technocratic approach to performance management of and in public administration is a key feature of managerial governance. Here, practices from the corporate sector aimed at a distinct, ‘scientific’ approach to decision-making, whose more rigorous, formalised, and technical approach empowered decision-making by top management, providing them with new forms of agency, in opposition to traditional authorities and decision-making processes (Knafo et al. Citation2019). In this approach, data and models are used not only to think about the more efficient way to carry out a goal, but to decide on which objective to pursue in the first place (Knafo Citation2020). Governance of a country thus becomes primarily oriented towards optimisation practices, with the material and other political dimensions of development choices, and their ‘fairness’, receding from consideration. As Knafo points out, ‘micro managerial decisions about efficiency were imbued in this framework with new macro or strategic significance’ (Knafo Citation2020, 789).

In the context of the governance of ODA, a reliance on a managerialist approach to the governance of the Tanzanian PFMRP raises several concerns. Foremost is how it can mask the highly politically sensitive nature of donor intervention through resort to technical rationales. Thus, DFID’s ‘Business Case’ rationalises its intervention in Tanzanian public financial management using technical ‘key PFM indicators.’ These indicators use data from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to assert that on, for example ‘fiscal policy’, Tanzania scored 3.5 out of 6, with ‘limited improvement recorded in recent years’, and that in relation to ‘Budgetary Management’, Tanzania scored 3.0 out of 6, noting that ‘budget credibility is low and affects budget execution’ (DFID Citation2017, 5). Though the rationale for this scoring system is not elaborated, DFID proposes a need for ‘budget credibility’ based on recognition that ‘Fiscal policy in Tanzania is often used as a political tool … hampered by a nexus of interests between the ruling party, the government and businesses’ (ibid., 6). Thus, a managerial approach to donor governance of the PFMRP potentially enables a donor-led highly partial approach to public financial management reform based on internationally derived indices whose responsiveness to the local context is unclear. It risks replicating a pattern of intervention by donors and international financial institutions of the implementation of accounting and auditing reforms which are ill suited to local needs (Lassou et al. Citation2021), as research on the earlier implementation of the EPICOR accounting system in some Tanzanian Local Government Authorities indicates (Mzenzi Citation2013).

The PFMRP articulates a multi-faceted ‘robust and effective’ programme management and implementation process (ibid xi), where donors’ roles are key. Firstly, a high level strategic and policy dialogue mechanism between Tanzania/Zanzibar, and donors (Development Partners or DPs) on PFM issues is created ‘to provide an opportunity for senior officials of the MOFP and DPs to discuss policy level PFM issues and reform priorities’. Secondly, there is a Joint Steering Committee of representatives from Tanzania-Zanzibar and donors, to provide oversight, guidance, and direction to the implementation of the reform programme, with approval authority for all its work. Finally, there is a Technical Working Group on each of the seven strategic objective areas of the PFMRP, to provide a forum for technical discussions to build consensus on implementation prior to the Joint Steering Group meetings. This is to be co-led by a lead implementing agency and parallel donor counterparts.

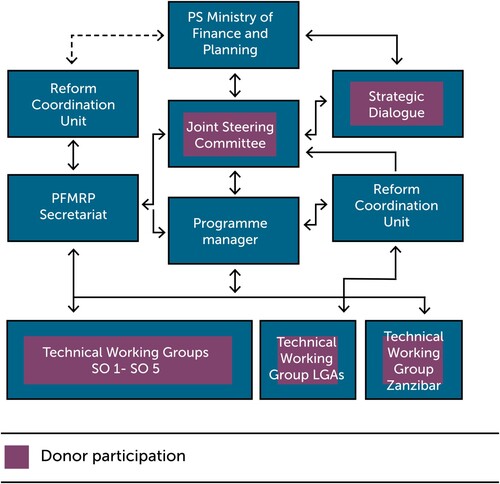

While the PFMRP also has a Secretariat and a Programme Implementation Committee (to which civil society members may be invited), from the above we can clearly see that donors are fully involved in leadership, decision-making, and technical advisory roles in the key implementation mechanisms of the PFMRP (ibid., 38–41). However, their invisibility in these roles is, revealingly, visually captured in the report’s original organogram in which donors’ presence is completely left out. I have modified it to visually include donors’ presence (). Of deeper significance is the omission from the PFMRP report of recognition of the legal responsibility of the National Assembly in oversight of PFMRP, or to reports on its implementation by the Minister or nominated elected representative to the National Assembly or to any of its Committees, as might be expected by the requirements of the Public Finance Act (2004).

Figure 1. PFMRP Phase V institutional arrangements with donors’ presence highlighted by author. Source: Adapted from Ministry for Finance and Planning, PFMRP Phase V (2017/18–2021/22) at 37.

Notably, DFID is both a key funder and actor in the Tanzanian PFMRP and governance mechanisms. It chairs the PFM Development Partners Group; was the lead donor in the preceding Phase IV Reform Programme; works closely with other key international donors such as the IMF’s Policy Support Instrument and the World Bank’s Development Policy Operations, as well as the budget support operation of the EU.

Though the scope of the PFMRP includes wider institutional arrangements for Tanzania’s macro-economic, budget, and financial accountability systems, DFID’s focus prioritises funding reform aimed at improving the regulatory environment for the business sector in Tanzania, including ‘[S]upporting the strategic GoT-donor dialogue platform with information and advice on fiscal and tax policies for a conducive business environment; support policy advocacy and research on business environment through reputed think-tanks … .work with the wider HMG and continue to raise challenging business environment issues facing international investors’ (DFID Citation2017, 7). It is notable that the UK is one of the largest suppliers of foreign direct investment (FDI) to Tanzania with a 36% market share, followed by the US and China (Tanzanian Investment Hub Citation2019; also DFID Citation2019).

Beyond conditionality – institutionalising co-governance in ODA-recipient states

Budget support is an aid modality. It should not be seen as an end in itself, but as a means of delivering better aid and achieving sustainable development results. It involves dialogue, financial transfers to the national treasury account of the partner country, performance assessment and capacity development … . it is important to distinguish between the budget support aid modality, which incorporates all four elements of this package, and budget support funds, which relates only to the financial resources transferred to the partner country. (European Commission Citation2012, 11, emphasis added)

A thick web of donor-originating bureaucratic organisational arrangements such as Donor Co-ordination Groups and sub-groups institutionalise intimate intervention by donors within the aid-recipient state’s governance processes. These are enmeshed within and operate alongside recipient states’ own aid management bureaucratic mechanisms, government departments and domestic policy processes. Tanzania’s mechanisms for co-ordinating donor engagement are recognised as one of the most advanced and deliberate in aid-recipient states. What began several decades ago as recipient state efforts at donor ‘co-ordination’ (Helleiner et al. Citation1995), have now resulted in permanent institutionalised co-governance by donors within the aid-recipient state.

By the mid-1990s, Tanzania had a national Planning Commission, supplemented by sectoral strategies for the social services sector, agriculture, infrastructure, and the civil service. Dedicated systems and institutional mechanisms were set up to exchange information between donors and the various parts of the Tanzanian state, and separately between donors themselves, with the establishment of a Donor Assistance Committee (of the main OECD Development Assistance Committee donors) that met once a month. This mechanism paralleled joint Government – Donor meetings, Joint Evaluation Committee and Joint Management Committee monthly meetings. The Tanzanian Donor Assistance Committee was replaced in 2004 by the Development Partners Group (DPG) of 17 bilateral and five multilateral donors. A new kind of Government of Tanzania–DPG planning instrument was developed called the Tanzania Assistance Strategy, later replaced by the Joint Assistance Strategy for Tanzania (JAST) that expired in 2011, itself replaced by a more recent Development Co-operation Framework. Under the DPG, several policy Clusters exist, each with several Working Groups. One example is the Development Partners Agriculture Working Group (A-WG) of 19 bilateral and multilateral donors engaged in the agricultural sector in Tanzania. Meeting monthly, the Group has a sophisticated working method, including terms of reference and a code of conduct agreed between government and donors, with meetings and work schedules organised through a modified troika chairing structure. In addition to aid administration and review mechanisms, donors are also engaged in key national fora on financing development including annual Public Expenditure Reviews, reviews of its General Budget Support, and reviews of policy reform (undertaken through reviews of Memoranda on Economic and Financial Policies). These fora also include key institutional actors at the national level such as the Bank of Tanzania, and at the international level, such as the IMF (URT Citation2006, 23).

Currently, Tanzania is operating under a Five-Year Development Plan II (2015/16–2020/2021) that combines and replaces two prior frameworks that separately focused on economic growth (the first five-year plan) and poverty reduction (the Mukukuta II) plan. The Plan seeks to incorporate aspects of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025 that aims to make Tanzania a middle-income country by 2025. Legal and institutional reform is a central policy aim of these plans, reflecting wider international development policy on a changed role of the state to foster a particular kind of transnational capital-led neoliberal reform. Vision 2025 describes three underlying principles for ‘good governance’ institutional reform to include (i) unleashing the power of the market and the private sector; (ii) striking a balance between the state and other institutions (markets and the economy); and (iii) promoting democratic participation (URT Planning Commission Citation1999, 23–24). The market-enhancement focus of these principles is reflected in specific law and regulation reform initiatives elaborated in both recent five-year plans (the 2011/2012–2015/2016 Plan and 2016/2017–2020/2021 Plan, respectively). Of note are references to improvements to Tanzania’s score on the World Bank’s ‘Ease of Doing Business Index’ (DBI) in both documents as rationales for and evidence of, success in particular kinds of reforms. Thus the 2011/2012 five-year plan notes the state’s dedicated attention to legal reform to encourage business investment, including in areas such as infrastructure, access to finance, macro-economic stability, taxation and labour market efficiency, and commits it to further specific reforms in getting construction permits, the registration of property, obtaining financial credit, cross-border trading and closing a business, with dedicated attention to Special Economic Zones to be employed as an efficient instrument to improve the ease of doing business in targeted regions (United Republic of Tanzania President’s Office Citation2012, 41). The current 2016/17 Plan makes the DBI’s twelve areas (that include starting a business, registering property, protecting investors, and enforcing contracts) and improvements in the Index’ scores, a central part of its reform agenda (URT Ministry of Finance and Planning Citation2016, 82–83).

The significance of donor funding of reform to Tanzania’s development strategies over the years is reflected in the existence and work of multiple sector-focused donor-funded government reform initiatives. These include the Public Service Reform Programme (PSRP), the Public Financial Management Reform Programme (PFMRP), the Legal Sector Reform Programme (LSRP), the Local Government Reform Programme (LGRP), the National Anti- Corruption Strategy and Action Plan (NACSAP), and for the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar’s Economic and Financial Reforms, Institutional and Human Resource Reforms, and the Good Governance Reform programmes. These highlight the centrality of legal reform to development planning, and to donor’s funding agendas, and raises a question about the kind of legal logic employed in these reform programmes.

Unsurprisingly, as seen earlier in Tanzania’s PFMRP, market-centred governance techniques of New Public Management (NPM) such as audits, targets, internal markets, performance indicators, and emphasis upon outputs (Gamble Citation2006, 30), are also highly visible. Tanzania’s first five-year plan included an explicit commitment to the adoption of New Public Management Principles in its Local Government Reforms Programme. For donors, this turn can also be seen in the UK’s current aid strategy that includes a dedicated approach to ‘Value for Money’ and ‘Payment by Results’ in assessing project ‘success’ (UK HM Treasury and DFID Citation2015).

It is curious that a continued commitment to NPM remains, as initiatives to de-bureaucratise and decentralise Tanzanian government have long preceded the first five-year plan, with questionable results. A ten-year Civil Service Reform Programme, begun in 1991, already included a similar objective. Though the programme was deemed to be successful in reducing the numbers of public service staff by 25% by 1998, results in terms of decentralisation of decision-making were very weak. One commentator noted that though reforms were made, new institutions remained unused except for meetings, with ‘ownership of the reform remain(ing) with donors and external consultants based in the President’s Office, Public Service Management’ (Khamba Citation2017, 161). Though available data suggest that results to date have been mixed (Hulst et al. Citation2015), donor commitments to NPM principles in civil service reform continue in reform plans.Footnote10

The technocratisation of aid-recipient state development planning is especially visible in the latest Tanzanian five-year plan. Assessment of progress of the previous five-year plan to 2015 is described as follows – ‘[O]verall performance was 50 percent based on achieved indicators … [with]FYDP performance (to) reach 60 percent by June 2016.’ Visually, the document that captures the policy goals and commitments of Tanzania and Zanzibar is data heavy, with policy goals and commitments for each of the twenty-three policy areas for the forthcoming period presented in tabular form, along with timeframes, indicators and objectives listed. Performance targets and indicators are described for manufacturing, industrial, mining, construction, agriculture, trade, natural resources management, tourism, science and technology, the creative industry, human development, education, skills development, health, water and sanitation, urbanisation and housing, food security, social protection, good governance sectors as well as on macroeconomic stability, infrastructure and services and improving performance in ease of doing business (URT Citation2016, xvii–xviii). Narrative sections are peppered with terms such as ‘interventions’, ‘flagship projects’, ‘priority areas’, ‘criteria’, ‘factors’ and ‘indicators’.

Thus, we see how a technical and managerial framing and bureaucratic implementation of donor intervention masks a highly partial, executive intervention in Tanzanian domestic affairs in ways that remain legally and institutionally invisible to the domestic law and institutions in Tanzania. My description of the extensive donor intervention mechanisms at the national (the DPG, public finance reform etc.,) and sectoral levels (in areas such as law reform, agriculture etc.) reveals how donors have inserted and institutionalised their presence at the highest political and executive levels in the domestic governance of Tanzania. Clearly, the bureaucratic and technocratic instruments and practices of ODA governance used by donors are hugely influential in constructing the ‘objects and objectives … the grammar of analyses and prescriptions, the vocabularies of programmes, the terms in which the legitimacy of government is established’ (Miller and Rose Citation1990, 6). Framed thus, Budget Support – of Public Financial Management Reform especially – offers donors an entry point to much deeper intervention in Tanzania’s domestic laws and institutions in ways that escape domestic democratic scrutiny. Furthermore, how Budget Support is articulated means that the potential and risk of executive donor intervention in areas and in ways that serve donor self-interest remains both hidden and high, though it may be contrary to recipient state’s own development pathway choices, and to international best practice on PFM.

Rationality, regularity and rule in ODA's governance

If we return to the governance of/by dynamic intrinsic to ODA and its juridical qualities, we can see that a particular kind of legal rationality is implicit in the governance of/by dynamic intrinsic to ODA. This denudes law in general – and the laws and institutions of the recipient state in particular – of their political and symbolic meanings, and of the potential for a more participatory kind of politics that recognises accountability to the demos as central to the aid-recipient state. First, there is the predominant framing of legal and policy reform in abstract and technical terms, in ways that are amenable to technocratic assessment and monitoring, and managerial intervention. The spread of corporate techniques of counting and auditing to the domain of law and institutional reform by the state, not only reflects a seepage of corporate forms of governance into governance and law reform more generally, (and specifically into public financial management), but also carries within it a normative theory or worldview of how law and institutional reform is instigated, undertaken, and implemented.

Related to this, secondly, is an implicit view of the recipient state as a nomocratic one. Plant (Citation2010, 6–7) notes that ‘[N]omocratic politics focuses on the idea of political institutions as providing a framework of general rules which facilitate the pursuit of private ends, however divergent such ends may be. It is not the function of political institutions to realise some common goal, good, or purpose and to galvanise society around the achievement of such a purpose. Rather, nomocratic politics is indifferent to common ends and has an interest in private ends only in so far as they may collide.’ In this instance, we see that DFID’s approach to the role for law, and the role of the state, is a neoliberal one, oriented towards the integration of Tanzania in the global economy. This kind of state form is pursued even when the recipient Tanzanian state has elaborated, for example in its constitution and in its mining laws of 2017, a different role for itself and a different approach to rights such as ownership of property.

Thirdly, we see how, by institutionalising donor governance through bureaucratic mechanisms and technocratic means, donor intervention in recipient state governance remains very distant from scrutiny by Tanzania’s democratic governance institutions. In general, donors are not ordinarily accountable before the Tanzanian legislature, to Parliamentary mechanisms such as its Budget Committee. Given the centrality of public financial reform to donor engagement, it remains unclear whether institutions such as Tanzania’s Accounting Officer or the Ministry of Finance and Planning can credibly and effectively scrutinise and report on donor activity therein. This kind of institutionalised co-governance by donors remains invisible to recipient state domestic law and governance institutions. Paradoxically, scrutiny of donor institutions and instruments aimed at reform of Tanzania’s own governance institutions and instruments may well be beyond the formal purview of Tanzania’s current legal and institutional governance arrangements.

The juridical qualities to ODA’s governance institutions, instruments and practices are further enhanced by the operation of underlying temporal and scalar structural dynamics. On the former, for this meso-level, three dimensions are relevant. The first is the significance of repetition and performance in the bureaucratic and technocratic governance instruments and practices on ODA just described. Here we see a constant and never-ceasing production of time-bound annual, three -, five- and longer-year programmes, plans and strategies, augmented with periodic reviews and reports, undertaken through schedules of meetings of Working Groups, sectoral clusters, co-ordination groups, Task Forces and so on. Together, these act as mini regimes of temporal control (Adib and Emiljanowicz Citation2019; Brook Citation2009). Secondly, the centrality of this schedule of meetings involving mainly just two sets of actors – donors and aid-recipient state representatives – using set-piece bureaucratic mechanisms and technocratic governance instruments, over time, performatively (Butler Citation2010) institutionalises and naturalises a differentiated authority and identity between donor states and recipient states. Thirdly, the absence of any recognition and consideration of longue durée in the governance interventions to be funded by Budget Support etc. effectively removes the ‘development’ of Tanzania – and the actions of its donors – from their continuities with approaches to governance of Third World states in a colonial and imperial context, an area that has only recently begun to be explored in the context of international development policy (Schmitt Citation2020; Chiba and Heinrich Citation2019).

This article’s focus on the meso-level institutional interface of governance encounters via ODA between donors as a group and Tanzania as a recipient state, reveals a significantly different role for law and legality in the governance of ODA than that exposed through analysis of other levels (see Introduction). Attention to the scalar dimensions to ODA’s governance reveals different features of significance to the role of and for law at each level. Superficially, two dimensions stand out. At the national level, for some aid-recipient states, ODA continues to remain a very significant source of central government expenditure (according to World Bank Citation2019 figures, for Rwanda it was 59.5%; for Ethiopia, 51.7%; for Tanzania, 29.5%; for Kenya 17.2%; with Somalia’s recorded as 15,548,980%).Footnote11 Donor governance and co-ordination institutions within Tanzania are mirrored in many other recipient states that have OECD DAC donors, and international development organisations and institutions. Taking the countries just listed, this ‘permanent co-governance’ is institutionalised in many of the states, potentially constituting a web of donor co-governance across East Africa. At the extra-national level, other governance dimensions and relations also emerge, for example, how one donor governs their ODA across multiple aid-recipient states, and/or interacts with other international entities such as the DAC (if a member) or other International Financial Institutions. Thus, consideration of the multi-scalar dimensions to ODA’s governance holds much potential for future legal research.

Conscious of an analysis that emphasises the transnational cohesion and institutional stability of ODA governance practices, it is important to also recognise that situations and sites of contestation and (potentially) rupture do exist, where law may be both a key site and instrument of both. Recall the preamble and attached schedules of Natural Wealth and Resources (Permanent Sovereignty) Act 2017, which referred to articles of the Constitution of Tanzania on the Government’s duties to the Tanzanian people; the UN General Assembly Resolutions on Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources, and the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States. Though this fascinating site and incidence of legal contestation is not dwelled on here, it does signal a potential within law for disruption of development ‘proper’. Thus, despite a clear turn towards increasing technification of governance and law by donors through ODA, the laws and institutions of aid recipient states continue to retain significant symbolic potential. In the example described earlier, the symbolic role of and for law is revealed, along with its unique ability to connect with laws from other jurisdictions (such as from the UN General Assembly) and other, non-Northern approaches to law in development (such as the New International Economic Order). Whether this incidence marks this legal development as a contemporary example of contested postcolonial legality (Baxi Citation2012), an attempted, if partial, break from prior laws on the governance of Tanzania’s natural resources, remains to be further explored.

Conclusion

This article contributes new insights to critical legal engagement on hidden legal dimensions to governance of/by ODA. Here, I offer a conceptual approach that aims to reveal formerly hidden juridical features to the governance of/by dynamic that makes ODA such a powerful, yet under-recognised, field of global governance. In this way, the juridical dimensions to what are ordinarily considered ‘soft law’ technocratic and bureaucratic approaches and instruments for donor ODA governance are revealed, as well as their governance effects. First, these enable ODA to be in dynamic and deliberate engagement with formal law and governance institutions, while being selectively – and simultaneously – visible and invisible to those institutions. Secondly, it places donors in positions of executive authority within the recipient state’s domestic policy decision- and implementation processes. Thirdly, the legal and political governance effects of this approach to ODA governance create highly differentiated legal and political subjectivities of both donors and aid-recipient states, cognisable to and posing challenges to the legal and democratic institutions and demos of the latter. Donor executive authority and permanent donor co-governance are institutionalised in recipient states in ways that remain invisible to and distant from recipient states’ own legal and political institutions of scrutiny, oversight, and accountability, as well as to regional and international law(s) and institutions.

The location of the governance scale of analysis at the meso-level here offers the potential for deriving governance insights that would otherwise remain invisible at the micro- or macro-level. These include how ODA, through what appears to be a benign financial transfer in the form of Budget Support, opens opportunities for donors as a group to exercise executive authority and create avenues for donor policy intervention in legal and policy reform in the recipient state, in ways that may not conform to donor-affirmed international best practice on financial reform, for example, and whose governance effects may remain similarly outside effective scrutiny by the recipient state. Meso-level scrutiny may also offer advantages to research on ODA’s governance, not least in lending to identifying sites and strategies of contestation and resistance in ways that better reveal – or perhaps indicate a greater scope for – recipient state agency and governance contingency in transnational governance than have been previously identified. Here, greater attention to the scalar also reveals other factors and dimensions to the operation and effectiveness of ODA’s governance of/by dynamic that have only been touched upon in this article. In this instance, temporal considerations relating to how regimes of time are central to donor governance, and the significance of repetition and performance to subjectivities, agency and relations between donors and recipient states, emerge to the fore. Tracing the role of law and presence of the juridical in the rationality, regularity, and rule in ODA’s governance and paying particular attention to the scalar helps reveal overlooked dimensions to ODA’s governance that may counter the top-down and siloed approach that predominates in legal research in international relations, while offering opportunity for greater innovation in critical legal research on the governance of international development more broadly.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments, as well as Professor Mark Toufayan and Dr Giedre Jokubauskaite for their insights and observations on earlier versions of this article. This article is part of a larger project on the international governance of ODA, insights from which were shaped by researchers and professionals in Canada, the EU and Tanzania, over several years. I thank you all. Special thanks to the Tanzanian-German Centre for East African Legal Studies, at the School of Law, University of Dar es Salaam; to Dr Kennedy Gastorn, and to the academic and administrative staff of the School of Law there, who kindly facilitated a research visit in 2015 to undertake part of this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siobhán Airey

Siobhán Airey is Government of Ireland Research Fellow at the School of Law, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Her research examines law and legality in the international governance of development, including its international financing.

Notes

1 ‘Grants or loans to countries and territories on the DAC List of ODA Recipients (developing countries) and to multilateral agencies which are: (a) undertaken by the official sector; (b) with promotion of economic development and welfare as the main objective; (c) at concessional financial terms (if a loan, having a grant element of at least 25 per cent). In addition to financial flows, technical co-operation is included in aid. Grants, loans and credits for military purposes are excluded. Transfer payments to private individuals (e.g., pensions, reparations or insurance payouts) are in general not counted.’ See http://www.oecd.org/dac/dac-glossary.htm#ODA.

2 MOUs on ODA remain difficult to obtain from donors and are not ordinarily publicly available.

3 While details of the habitus of groups of ODA professionals and their joustings is certainly key to ODA’s governance at several levels, is not the central focus in the account here. Though a stand-out feature of ODA’s governance is the universality of its habitus, and transnational ‘mobility’ of its personnel, it is highly unlikely that ODA professionals operating at the meso-level examined in this article, view themselves as engaging significantly with law; neither would they likely view ODA as necessarily constituting a juridical field in the way that Bourdieu coined the term.

4 These are the Natural Wealth and Resources Contracts (Review and Re-negotiation of Unconscionable Terms) Act, 2017 (‘Unconscionable Terms Act’) that mandates the Government to renegotiate or remove terms from investor-state agreements that Parliament considers ‘unconscionable’; The Natural Wealth and Resources (Permanent Sovereignty) Act, 2017 (‘Permanent Sovereignty Act’) requires Parliamentary approval for future investor-state agreements, which must ‘fully secure’ the interests of Tanzanian citizens, and restricts investors from exporting raw minerals, repatriating funds and accessing international dispute resolution mechanism, and the Written Laws (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act, 2017 (‘Miscellaneous Amendments Act’) amends the Mining Act, 2010 (‘Mining Act’) by (among other things): establishing a Mining Commission to regulate the industry; overhauling the requirements for the storage, transportation and beneficiation of raw minerals; and increasing royalty rates and government shareholding in mineral right holders.

5 Constitution of the United Republic of Tanzania, Article 27, and Article 9 respectively.

6 Article 17 on ownership of property, and Article 21 Right to Free Disposal of Wealth and Natural Resources, respectively.

7 In the mining industry, beneficiation is a process that improves the economic value of the ore by removing the gangue minerals (the commercially valueless material in which ore is found).

8 Art. 11 of the Natural Wealth and Resources (Permanent Sovereignty Act, No. 5), 2017.

9 An announcement that DFID and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office were to merge was made in June 2020, by the UK’s Prime Minister, Boris Johnson. For this article, I retain the references to DFID as this was the UK’s donor body responsible for ODA at the time of this research.

References

- Adib, and Paul Emiljanowicz. 2019. “Colonial Time in Tension: Decolonizing Temporal Imaginaries.” Time & Society 28 (3): 1221–1238. doi:10.1177/0961463X17718161.

- Aust, Anthony. 2012. “Alternatives to Treaty-Making: MOUs as Political Commitments.” In The Oxford Guide to Treaties, edited by Duncan Hollis, 46–72. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baxi, Upendra. 2012. “Postcolonial Legality: A Postscript from India.” Verfassung und Recht in Übersee / Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America 45 (2): 178–194. doi:10.5771/0506-7286-2012-2-178.

- Bhatt, Kinnari. 2020. Concessionaires, Financiers and Communities, Implementing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights to Land in Transnational Development Projects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. “The Force of Law: Toward a Sociology of the Juridical Field.” Hastings Law Journal 38 (5): 805–813. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/hastlj38&i=825.

- Brook, Timothy. 2009. “Time and Global History.” Globalizations 6 (3): 379–397. doi:10.1080/14747730903142009.

- Brown, Stephen. 2020. “The Rise and Fall of the Aid Effectiveness Norm.” European Journal of Development Research 32 (4): 1230–1248. doi:10.1057/s41287-020-00272-1.

- Butler, Judith. 2010. “Performative Agency.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2): 147–161. doi:10.1080/17530350.2010.494117.

- Chiba, Dainam, and Tobias Heinrich. 2019. “Colonial Legacy and Foreign Aid: Decomposing the Colonial Bias.” International Interactions 45 (3): 474–499. doi:10.1080/03050629.2019.1593834.

- Commission, European. September 2012. Tools and Methods Series Working Document: Budget Support Guidelines. Programming, Design and Management – A modern approach to Budget Support. Brussels: EuropeAid DevCo, 2012. An updated version (2018) has been issued.

- Cox, Marcus, and Gemma Norrington-Davies. January 2019. Technical Assistance: New Thinking on an Old Problem. London: Open Society Foundations. https://agulhas.co.uk/publications/technical-assistance-new-thinking-old-problem/.

- Dann, Philipp. 2013. The Law of Development Cooperation, A Comparative Analysis of the World Bank, the EU and Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Davis, Kevin E. 2009. “Financing Development’ as a Field of Practice, Study and Innovation.” Acta Juridica, 168–184. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1341291.

- de Mesquita, Bruce Bueno, and Alastair Smith. 2007. “Foreign Aid and Policy Concessions.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51 (2): 251–284. doi:10.1177/0022002706297696.

- de Moerloose, Stéphanie. 2020. World Bank Environmental and Social Conditionality as a Vector of Sustainable Development. Zurich: Schulthess Verlag.

- Department for International Development UK. 2017. Business Case Summary Sheet – Strengthening Public Financial Management in Tanzania (2018–2023). On file with author.

- Department for International Development UK. 26th February 2019. “Doing Business in Tanzania: Tanzania Trade and Export Guide.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/exporting-to-tanzania/exporting-to-tanzania.

- Easterly, William, and Tobias Pfutze. 2008. “Where Does the Money Go? Best and Worst Practices in Foreign Aid.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22 (2): 29–52. doi:10.1257/jep.22.2.29.

- Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, and Desmond McNeill. 2019. “Knowledge and Politics in Setting and Measuring the SDGs: Introduction to Special Issue.” Global Policy 10 (S1): 5–11. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12604.

- Gamble, Andrew. 2006. “Two Faces of Neo-Liberalism.” In The Neo-Liberal Revolution: Forging the Market State, edited by Richard Robison, 20–35. London: Palgrave.

- Gehring, Thomas. 2004. “Methodological Issues in the Study of Broader Consequences.” In Regime Consequences – Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies, edited by Arild Underdal and Oran R. Young, 219–246. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Gibson, Clark C., Barak D. Hoffman, and Ryan S Jablonski. 2015. “Did Aid Promote Democracy in Africa? The Role of Technical Assistance in Africa’s Transitions.” World Development 68: 323–335. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.009.

- Government of Tanzania. September 2017. Five Year Medium-Term Strategic Plan for the Public Finance Management Reform Programme (PFMRP) Phase V (2017/18–2021/22). http://www.mof.go.tz/index.php/public-financial-management-reform-programme-pfmrp. On file with author.

- Helleiner, Gerry K., Tony Killick, Nguyuru Lipumba, Benno J. Ndulu, and Knud Erik Svendsen. June 1995. Development Cooperation Issues Between Tanzania and its Aid Donors, Report of the Group of Independent Advisors. (On file with author).

- Hulst, Rudie, Wilhelm Mafuru, and Deogratias Mpenzi. 2015. “Fifteen Years After Decentralisation by Devolution: Political-Administrative Relations in Tanzanian Local Government.” Public Administration and Development 35 (5): 360–375. doi:10.1002/pad.1743.

- Jokubauskaite, Giedre. 2018. “The Legal Nature of the World Bank Safeguards.” Verfassung in Recht und Übersee 51 (1): 78–102. doi:10.5771/0506-7286-2018-1-78.

- Jokubauskaite, Giedre. 2019. “The World Bank Environmental and Social Framework in a Wider Realm of Public International law.” Leiden Journal of International Law 32 (3): 457–463.

- Jokubauskaite, Giedre, and David Rossati. 2021. “A Tragedy of Juridification in International Development Finance.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d'études du développement, doi:10.1080/02255189.2021.1895090.

- Karwowski, Ewa. 2021. “Commercial Finance for Development: A Back Door for Financialisation.” Review of African Political Economy. (Online, unassigned). doi:10.1080/03056244.2021.1912722

- Kihamba, John S. 2017. “New Public Management Issues in Tanzania.” In New Public Management in Africa, Emerging Issues and Lessons, edited by Benon C. Basheka and Lukamba-Muhiya. Tshombe, 149–171. New York: Routledge.

- Knack, Stephen, Bradley C. Parks, Ani Harutyunyan, and Matthew DiLorenzo. April 2020. How Does the World Bank Influence the Development Policy Priorities of Low-Income and Lower-Middle Income Countries? World Bank Group Policy Research Working Paper 9225, Development Research Group. Available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33707?locale-attribute=en.

- Knafo, Samuel. 2020. “Neoliberalism and the Origins of Public Management.” Review of International Political Economy 27 (4): 780–801. doi:10.1080/09692290.2019.1625425.

- Knafo, Samuel, Sahil Jai Dutta, Richard Lane, and Steffan Wyn-Jones. 2019. “The Managerial Lineages of Neoliberalism.” New Political Economy 24 (2): 235–251. doi:10.1080/13563467.2018.1431621.

- Krever, Tor. 2013. “Quantifying law: Legal Indicator Projects and the Reproduction of Neoliberal Common Sense.” Third World Quarterly 34 (1): 131–150. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.755014.

- Lassou, Philippe J.C., Trevor Hopper, and Collins Ntim. 2021. “Accounting and Development in Africa.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 78: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2020.102280.

- Lundsgaarde, Erik, and Lars Engberg-Pedersen. 2019. The Aid Effectiveness Agenda – Past Experiences and Future Prospects. Copenhagen: DIIS – Danish Institute for International Studies. https://www.diis.dk/node/21711.

- Masaki, Takaaki, Bradley C. Parks, Jörg Faust, Stefan Leiderer, and Matthew D. DiLorenzo. 2021. “Aid Management, Trust, and Development Policy Influence: New Evidence from a Survey of Public Sector Officials in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries.” Studies in Comparative International Development 56 (3): 364–383. doi:10.1007/s12116-020-09316-3.

- McHugh-Russell, L. 2021. “Doing Business Guidance, Legal Origins Theory, and the Politics of Governance by Knowledge.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d'études du développement, doi:10.1080/02255189.2021.1971953.

- Merry, Sally E. 2019. “The Sustainable Development Goals Confront the Infrastructure of Measurement.” Global Policy 10 (S1): 146–148. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12606.

- Miller, Peter, and Nikolas Rose. 1990. “Governing Economic Life.” Economy and Society 19 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1080/03085149000000001.

- Mzenzi, Siasa Issa. 2013. Accounting Practices in the Tanzanian Local Government Authorities (LGAs). Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Southampton, Faculty of Business and Law.

- OECD. 2019. Making Development Co-operation More Effective, 2019 Progress Report, OECD and UNDP. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/making-development-co-operation-more-effective_26f2638f-en.

- OECD. 2021. The OECD DAC Blended Finance Guidance. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/the-oecd-dac-blended-finance-guidance_ded656b4-en.

- Pattberg, Philipp, Oscar Widerberg, Maria Isailovic, and Flávia Dias Guerra. 18th August 2014. Mapping and Measuring Fragmentation in Global Governance Architectures – A Framework for Analysis. Amsterdam: IVM Institute for Environmental Studies, VU University of Amsterdam.

- PEFA. 2016. Framework for Assessing Public Financial Management. Washington, DC: PEFA. https://www.pefa.org/content/pefa-framework.

- Plant, Raymond. 2010. The Neo-Liberal State. Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Reigner, Michael. 2015. “Towards an International Institutional Law of Information.” International Organizations Law Review 12: 50–80.

- Rittich, Kerry. 2002. Recharacterizing Restructuring: Law, Distribution and Gender in Market Reform. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Rittich, Kerry. 2006. “The Future of Law and Development: Second Generation Reforms and the Incorporation of the Social.” In The New Law and Economic Development: A Critical Appraisal, edited by David M. Trubek and Alvaro Santos, 203–252. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ruhl, J. B., and Daniel Martin Katz. 2015. “Measuring, Monitoring, and Managing Legal Complexity.” Iowa Law Review 101 (1): 191–243.

- Sarfaty, Galit. 2012. Values in Translation: Human Rights and the Culture of the World Bank. Stanford, CA: Stanford Studies on Human Rights.

- Schmitt, Carina, ed. 2020. From Colonialism to International Aid – External Actors and Social Protection in the Global South. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Schotel, Bas. 2016. “Multiple Legalities and International Criminal Tribunals: Juridical Versus Political Legality.” In The Power of Legality: Practices of International Law and Their Politics, edited by Nicholas M. Rajkovic, Tanja E. Aalberts, and Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen, Chapter 8, 209–232. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Swedlund, Haley J., and Malte Lierl. 2019. “The Rise and Fall of Budget Support: Ownership, Bargaining and Donor Commitment Problems in Foreign Aid.” Development Policy Review 38 (S1): 50–69. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eoh&AN=EP143042588.

- Tan, Celine. 2011. Governance Through Development Poverty Reduction Strategies, International Law and the Disciplining of Third World States. Abingdon: Routledge-Cavendish.

- Tanzanian Investment Hub. 2019. “UK Investments in Tanzania” (undated) at https://www.tanzaniainvest.com/uk. Accessed 13th June 2021.

- Türkelli, Gamze Erdem. 2021. “Transnational Multistakeholder Partnerships as Vessels to Finance Development: Navigating the Accountability Waters.” Global Policy 12 (2): 177–189. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12889.

- UK HM Treasury & Department for International Development. November 2015. UK Aid: Tackling Global Challenges in the National Interest. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-aid-tackling-global-challenges-in-the-national-interest.

- United Republic of Tanzania President’s Office. 2012. The Tanzania Five Year Development Plan (2011/2012–2015/2016) “Unleashing Tanzania’s Latent Growth Potentials.” Planning Commission of Tanzania.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT). 2006. Joint Assistance Strategy for Tanzania (JAST), (December). http://www/tzdpg.or.tz.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT). June 2016. National Five Year Development Plan (2016/2017–2020/2021): “Nurturing Industrialisation for Economic Transformation and Human Development.” Ministry of Finance and Planning.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT) Planning Commission. 1999. Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025. (Planning Commission of Tanzania). http://www.tzdpg.or.tz/dpg-website/dpg-tanzania.html.

- Van Den Meerssche, Dimitri. 2021. “A Legal Black Hole in the Cosmos of Virtue – The Politics of Human Rights Critique Against the World Bank.” Human Rights Law Review 21 (1): 80–107. doi:10.1093/hrlr/ngaa045.

- Watts, Natasha, and Ivan R. Scales. 2020. “Social Impact Investing, Agriculture, and the Financialisation of Development: Insights from Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Development 130: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104918.

- Whitfield, Lindsay. 2009. Reframing the Aid Debate: Why Aid Isn’t Working and How it Should be Changed, DIIS Working Paper. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/44657.

- Woodroffe, Nicola, Matt Genasci, and Thomas Scurfield. August 2017. Tanzania’s New Natural Resources Legislation: What Will Change? Natural Resource Governance Institute. Available at https://resourcegovernance.org/analysis-tools/publications/tanzania-new-natural-resources-legislation-what-will-change.

- World Bank. 2019. WP Open Data Net ODA received (% of central government expense). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.ODA.ODAT.XP.ZS.