ABSTRACT

Widely heralded as a driver of sustainable development, ecotourism is promoted using images of rural landscapes. But how important are the landscapes themselves in these tourism projects? Based on advertising by tour operators and trekking agencies on their websites and reviews by tourists posted on Tripadvisor®, we have identified the motivations on which landscape resources are based and analyzed the importance of forests and anthropogenic landscapes (formed by agricultural activity in particular) in attracting tourists. This study is based on an analysis of representations of forested landscapes in the Nam Ha National Protected Area, in the mountains of Northern Laos.

RÉSUMÉ

L’écotourisme, régulièrement présenté comme un levier du développement durable, se fonde sur la promotion d’images paysagères. Quel est cependant la place des paysages dans ces projets? Nous avons identifié, à partir des discours des agences de trek collectés sur leurs sites web et les avis des touristes déposés sur Tripadvisor, sur quels motifs la ressource paysagère repose, et nous avons analysé la place de la forêt et des paysages anthropiques (façonnés notamment par l’agriculture) dans l’attractivité touristique. Cette réflexion est conduite à partir de l’analyse des représentations paysagères associées aux paysages de montagnes forestières d’une aire protégée du Nord Laos, la Nam Ha National Protected Area.

Introduction

The landscape is a key resource for tourism in many rural areas (Daugstad Citation2008; Dérioz, Bachimon, and Gauché Citation2020). In Asia tourism promises to diversify and increase revenue for local communities (Weaver Citation2002) and even to gain greater appreciation of local cultures in societies that marginalize their ethnic minorities (Scott Citation2009). Since the 1990s, ecotourism has come to be regarded as a sustainable alternative that reconciles community development and environmental conservation (Fletcher Citation2009). Ecotourism, as defined by the UNWTO, means “all nature-based forms of tourism in which the main motivation of the tourists is the observation and appreciation of nature as well as the traditional cultures prevailing in natural areas.”Footnote1 This institutional definition, among others, is confronted with more restrictive scientific definitions. These aim to mark a clearer break with conventional tourism by insisting on the truly sustainable character of this alternative model, both from the point of view of environmental conservation and the distribution of benefits (e.g. Lane Citation1994; Tuohino and Hynonen Citation2001; Higham Citation2007). Community-based tourism has developed in parallel, actively involving local communities to ensure that they receive a fair share of tourism revenue.

A number of studies have explored the success of this paradigm (Sacareau Citation2009). They generally approach ecotourism from an economic angle, assessing its effectiveness in terms of poverty reduction and revenue sharing (e.g. Adams et al. Citation2013; Harrison and Schipani Citation2007; Hoang et al. Citation2014), or, more recently, through the prism of ecosystem services (Brandt and Buckley Citation2018; Nahuelhual et al. Citation2014). Other studies address tourism projects involving educational efforts to promote the conservation of protected areas by examining changes in the (economic, ecological and social) value placed on forests (Catibog-Sinha and Wen Citation2008; Yang et al. Citation2015). In Laos, for example, several studies have focused on how local communities view tourism (Suntikul, Bauer, and Song Citation2009; Keovilay Citation2012) or, conversely, on the lack of tourist interest in aspects of the local culture (e.g. in Yunnan, China: Li Citation2011; Yang, Ryan, and Zhang Citation2013). Some more critical approaches consider ecotourism in terms of power relations. Several works have criticized the instrumentalization of the positive environmental image of ethnic minorities and demonstrated that ecotourism fails to integrate them (Forsyth Citation2003; Fletcher Citation2009). Landy et al. (Citation2020) tested in different Asian countries the effectiveness of “eco-ethnicity” concept to empower marginalized groups but concluded that it is not a decisive factor. Promotional touristic materials have been used to decipher the strategies of the dominant groups or the State on ethnic minorities (Lee and Abrahams Citation2018). Very few studies to date, on the other hand, explicitly utilize the concept of landscape beyond its physical apprehension (Gauché Citation2015) to assess the success of ecotourism projects. While Western countries promote a brand of “green” tourism centered on agricultural and pastoral landscapes (Daugstad Citation2008; Thompson et al. Citation2016), our objective in the following is to determine whether ecotourism in nations of the Global South is reduced to “natural” landscapes based on a specific example in Northern Laos.

Bernard, Roche and Sarrasin wrote about the role of ecotourism in socio-ecological systems in Luang Namtha, Northern Laos, in this journal in 2016. We propose to round out that approach here by examining the role of landscape in an ecotourism project launched in the early 2000s. Our object is to study the importance of the landscape itself in this tourism model. Although we do not support the dualistic division Nature/Culture criticized by P. Descola (Citation2005) or T. Ingold (Citation2002), we found that the ecotourism project in Luang Namtha increasingly enforces this artificial dichotomy, with trekking in the forest for “Nature” and interacting with villagers of the Khmu, Lanten and Akka minorities for “Culture.” We conceive of landscape as the visible and perceived product of interactions between society and nature (Berque Citation1994), the everyday landscape of villagers who take part in forming it (Ingold Citation2002) and the exceptional landscape of tourists and tourism professionals who seek to discover or promote it (Dérioz, Bachimon, and Gauché Citation2020). We also examine the part ethnic minorities play in promoting forest landscapes and the views of various stakeholders in ecotourism on landscape patterns produced by local communities. We analyze and compare representations of landscapes to identify the similarities and differences between aspects of the landscape promoted by some stakeholders and sought after by others.

After describing the area concerned and our methodology, we recount the history and characteristics of this pilot ecotourism project in the protected area of Nam Ha, analyze the representations conveyed by tour operators and travel agencies, tourists and villagers, and conclude with a discussion of the limitations of the tourism model in question.

Area and methodology

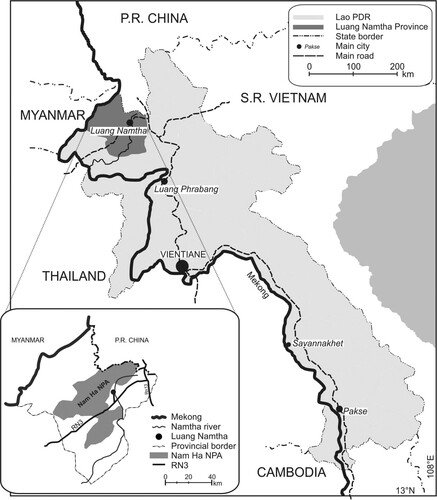

Luang Namtha is a province in northwestern Laos bordering on China and Myanmar (). It is an area of cross-border trade in which various ethnic minorities (Tibetan-Burmese, Mon-Khmer and Hmong-Mien) have been growing rice using shifting cultivation for centuries. Building on the establishment of the Nam Ha National Protected Area (NPA) in 1993, the Lao government launched the very first ecotourism project in this province in the early 2000s. As part of the AQAPA research project, we looked into recent changes in the landscape, due to ecotourism or not.

The area under consideration contains mountainous (500–2,000 m) and forested landscapes as well as several villages in the Nam Ha NPA. The NPA is traversed by Route 3 (N3), which was widened in 2008 to form a highway corridor from Bangkok to China (Taillard Citation2005; Ishida Citation2019). The mountain slopes closest to the road are occupied by rubber tree plantations under concession to Chinese investors, while the more remote areas form a mosaic of old growth and younger forests along with swiddens and fallows resulting from shifting cultivation. Some of the villages are located along the main road: accessible all year round, many of them resulted from the forced displacement of the population by the government in the 1970s (Ducourtieux Citation2013). The Khmu village of Chaleunsouk, comprising 70 families, was built in 1977 along N3 and is the starting point for many treks. Other villages are more remote, such as the Khmu village of Nalan Neua on the banks of the Nam Ha River. Made up of 43 families, it was also founded in 1977 and could only be reached by a five-hour walk from N3 until a dirt road was built in 2017. These two villages have been studied more thoroughly because they are destinations of choice for trekking agencies.

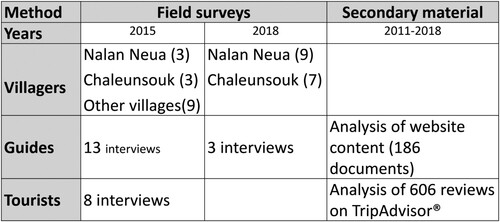

An analysis of landscape representations will serve to round out an approach based on the physical features of the landscapes and an analysis of the agrarian system (Cochet Citation2015; Ducourtieux Citation2013). Our approach draws on several types of surveys and materials to analyze representations of landscapes that have become tourist destinations (). We interviewed villagers during two missions. To make it easier for them to talk about the landscapes, they were shown photographs and sketches of several types of landscape deemed representative of local diversity (old-growth forests, rubber plantations, swiddens and fallows, irrigated rice paddies, rivers) to help them articulate their preferences according to various criteria (aesthetic, productive and environmental). We also interviewed trekking agency managers and guides in Luang Namtha, and collected descriptions of the activities offered by the agencies that have a website. Lastly, we used the same approach to analyze reviews and photographs posted by tourists on the Tripadvisor®Footnote2 website. This preeminent social network in the travel sector (Lu and Stepchenkova Citation2015) contributes to the construction of the image of a travel destination (Kladou and Mavragani Citation2015), and feedback from travelers influences tourist behavior (Stoleriu et al. Citation2019). The comments posted on Tripadvisor® obviated the need for us to interview tourists at just the right time, namely right after their trekking experiences, during their brief stays in the area. After harmonizing the spelling, the texts in English on the agency websites and on Tripadvisor® were subjected to a lexical analysis (Negura Citation2006; Germaine Citation2011; Comby Citation2013). Using the open-source software Iramuteq® and a descending hierarchical classification, we identified lexical fields characterized by a specific vocabulary distribution (Rouré and Reinert Citation1993; Cottet et al. Citation2018).

Ecotourism based on promoting forest landscapes

Before delving into landscape representations, let us return to the emergence of tourist activity in the province of Luang Namtha and how it is organized.

Ecotourism project following establishment of Nam Ha NPA

After the civil war and the establishment of the Lao People's Democratic Republic in December 1975, the country embraced a collectivist economy for a few years, then supplanted it in 1986 with a more free-market model, following the example of its Vietnamese and Chinese neighbors. In the wake of the country's gradual integration into the global economy, tourism has emerged as a national tool for poverty alleviation and development (Harrison and Schipani Citation2007). After the first foreign tourists were welcomed in 1989, the first plan to develop tourism was issued in 1990, prioritizing alternative principles of community-based and ecotourism as a means of generating new revenue (Khamvongsa and Russell Citation2009).

These tourism projects are closely associated with the natural protected areas established in 1993 to curb deforestation (Ducourtieux Citation2015), like the Nam Ha NPA in the Luang Namtha province (Bernard, Roche, and Sarrasin Citation2016). This protected area was extended in 1999 to encompass 2,224 km2, corresponding to one-fourth of the total area of the province (). It provides a habitat for some rare and endangered species of Asian elephants, felines, bears and ungulates (Johnson Citation2000) and nearly three hundred species of birds (Tizard Citation1997). In 2000, old-growth forest and a mosaic of secondary formations made up 32 per cent and 47 per cent of the NPA, respectively (Hedemark and Vongsak Citation2003). Nineteen villages (totaling 600 inhabitants) are located inside the NPA and 85 other villages adjacent to it. The villagers’ activities are restricted inside the NPA; shifting cultivation, hunting and gathering are prohibited within the so-called “core zones” and strictly regulated in the outlying areas. These restrictions account for the hourglass shape of the reserve, whose boundaries were drawn to exclude areas of intense human activity, e.g. along N3, which is lined with other villages, rice fields and rubber plantations.

Local trekking agencies: the mainstay of local tourism

The initial funding for the launch of the Nam Ha ecotourism project was provided by the governments of New Zealand (NZODA) and Japan. Various international institutions (e.g. GTZ) and NGOs (e.g. SNV Netherlands) have furnished financial and technical aid (Kleinod Citation2017) and remain present, providing support for the monitoring of biodiversity in particular. The Nam Ha NPA was to participate in the region's economic development by capitalizing on its attractiveness and the sustainable conservation of natural resources. Revenues from ecotourism were to enable local communities to improve their standard of living while giving up practices deemed harmful to the forest environment and illegal, such as shifting cultivation, hunting and opium poppy cultivation (Ducourtieux, Sacklokham, and Doligez Citation2017). The initial success of this pilot program in community-based ecotourism induced the Laotian government to replicate it in other provinces (Lyttleton and Allcock Citation2002; Schipani Citation2008).

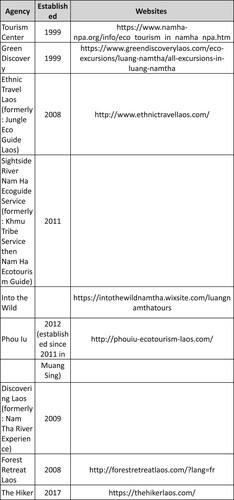

In the first place, three trekking and one kayak tours were launched and administered by the Provincial Tourism Office and the NPA Management Unit, which subsequently trained the guides as well. Private agencies then set up shop on the main street of the provincial capital. The first agency was a branch of Green Discovery, which has been operating in Vientiane since the late 1980s, followed by nearly ten competitors, not all of whom were to prove viable (). These agencies each offered a few trekking tours (1–4 days’ duration) combining hiking and kayaking with overnight stays in a village or camping out in the forest. In 2007, Schipani counted about 130 employees at these agencies. The tourist office, run by the provincial cultural service, provides information about the forest environment and local ethnic groups in the NPA.

The agencies are contractually required to provide a guide and an assistant guide for each trek as well as a local guide recruited from each village along the way. The gross proceeds from sales of trekking services must be distributed according to a breakdown decided by the provincial authorities: 51 per cent goes to the agency, 26 per cent to the villagers and 23 per cent to taxes. The agencies hire and pay the villagers to maintain the trails, to provide local guides and overnight accommodation: spending a night in a village is mandatory on each tour, either in a home or in an “eco-lodge” (a separate dedicated building). For “homestays,” villagers take turns hosting tourists and providing room and board for a consideration. For “eco-lodging,” the village council collects and manages payments on the community's behalf. The first eco-lodge was built in Nalan Neua. The women in the village are paid for the upkeep of the premises and welcoming and cooking for the tourists. Other villages, such as Nam Koi, have given up on eco-lodges due to insufficient occupancy, so the small numbers of tourists who do stay the night are housed in locals’ homes.

Early 2000s ecotourism boom

Tour operators in Europe, North America, Japan and Korea rarely propose trips to Laos alone: the itinerary usually focuses on neighboring countries (Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam) and includes excursion to Laos. Almost all include a stopover in Luang Phrabang, the former royal capital, and Vientiane, the present-day capital, which hold most the country's cultural attractions and are situated near natural sites of interest as well. Luang Namtha is by no means systematically included in the itineraries; when it is, then for a three-to-four-day stay to engage in outdoor activities (jungle treks, kayaking) and visit ethnic minority communities. These activities are associated with the Nam Ha NPA, which is described by the tour operator Evaneos as a place to discover “verdant landscapes of rice fields and pristine forests,” an “ideal reserve for observing the wilderness along the Nam Ha River, and where you’ll see plenty of birds and old-growth trees.”Footnote3

Ecotourism rapidly took off in Luang Namtha, jumping from no sales at all in the year 2000 to three thousand days of trekking in 2005. The vast majority of the trekkers were individual – Western (mainly European), followed by Japanese and Korean – tourists, who stayed an average of five days in the province. Most of them were young adults (18–29 years old), often passing through on regional or world tours, hence opportunity-based tourists, as opposed to hardcore trekkers flying in specifically for the local experience, as is the case for treks in Nepal, for example (Dérioz, Bachimon, and Gauché Citation2020). After peaking at 6,000–6,500 trekking days in 2007–2008, the number of treks has leveled off or slightly declined since then, even though the total number of tourists passing through the province has been steadily growing (increasingly tenfold between 2004 and 2015). One out of 15 tourists took part in a trek in 2004, as against only one out of nearly 50 now.Footnote4

Confrontation of divergent landscape representations

Tourists may have various motivations for traveling to a given place (Crompton Citation1979; Urry Citation1992), including a desire for a change of scenery and to discover new landscapes (Dérioz, Bachimon, and Gauché Citation2020). They come with their own systems of representation, which are then confronted with the discourse of tour operators seeking to attract clientele, and then with the reality on the ground, which is, in turn, influenced by the representations of local actors (Berque Citation1994; Gauché et al. Citation2019). The focus in the following is on the sensory relationship to the outside world, what Larrère (Citation2004) calls the “aesthetic landscape” (as opposed to say the landscape informed by science or initiated by planners and policymakers) or what Bertrand (Citation1991) simply calls “landscape” in his Geosystem/Territory/Landscape system.Footnote5 We stress here on the imaginary developed by tourists and promoters before to compare it with the materiality resulting from ecosystem characteristics and economic choices.

The “jungle experience” touted by trekking agencies

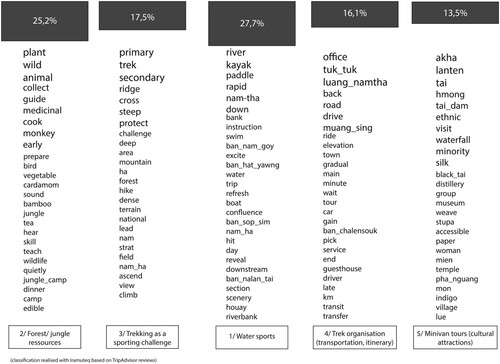

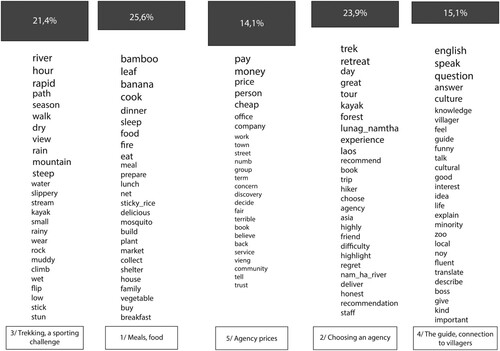

The local agencies advertise by means of posters and catalogs and, above all, in direct face-to-face exchanges with tourists in Luang Namtha. Publicity on the web has become a widespread practice as well since 2016, so we were able to analyze the content of ten agencies’ websites. We looked at a total of 186 texts, each of which describes an activity for a duration of one to ten days. The words most frequently used in these descriptions constitute two poles: the “village” (362 occurrences) and the “forest/jungle” (219). The lexical fields we identified reveal several recurring themes (): (1) water sports in the river, (2) forest/jungle resources, (3) trekking as a sporting challenge, (4) trek organization (logistics, itinerary) and (5) cultural activities on minivan tours of local villages (crafts, temples).

The villages are hardly, if at all, described as landscapes (buildings, gardens, topography), but in terms of the local communities, hence the references to various ethnic groups (76 occurrences) or “minorities” (58), who are mentioned by name (Khmu, Lanten, Akka). The village is the place where tourists can meet locals and learn about their daily lives. The descriptions break traditions (61) down into one-word categories: tourists are to discover the culture (30), customs (12) and women's clothes (16) (displayed in photographs for greater effect) by spending a night in the village either in a “community house” or at a villager's home. The village is sometimes associated with irrigated rice paddies; the farming of other crops is not mentioned.

The other area to discover is the forest. It is presented as a mountainous (87) national park (115 occurrences) traversed by a river (181) that is used for various sporting activities. The protected nature of the NPA is key to its tourist appeal: the boundaries of the protected area are shown on maps at the agencies (). The word “jungle” (81) is employed to highlight the exotic experience of one (or more rarely several) night(s) in the forest, encapsulated in the expression “jungle camp.” Indeed, the wild appeal of the landscapes is far more prominent in the very names of the agencies themselves than any cultural attractions (): e.g. Forest Retreat Laos, Green Discovery, Into the Wild, Jungle Retreat Laos (). The word “wild” is used 301 times in connection with fauna (wild pigs, monkeys, cats, bears etc.) and flora, though also to describe a way of life that involves tracking and hunting animals, cooking with bamboo utensils and building shelter for the night out of banana leaves. The forest is described as a place of resources. The descriptions of the treks draw attention to the forest's abundance: it provides food to be gathered, medicinal plants, materials for the jungle camp, etc. The flora and fauna are presented in terms of human needs, and only rarely in connection with the vocabulary of biodiversity (only a few species are mentioned).

Tourists seeking nature … though curious about local customs, too

We went through a total of 606 reviews on Tripadvisor® regarding 10 local agencies. The reviews are by tourists of various nationalities, ages, genders and profiles. They range from a few words to 3,500 characters, though most are brief. Some give practical information about booking and choosing a trek (), about meals and food from the market in town as well as produce gathered and prepared on site by the guide (1), and about the agencies’ reputations (2) and rates (5). The comments revolve above all around the various activities and how many days to spend there trekking through the forest, kayaking on the river or taking part in bike tours. They present these activities as sporting challenges that form part of the experience (3). Moreover, some of the reviews underscore the vital role of the guide (4).

The guides figure prominently in the discourse. They are the ones who transmit knowledge about the villages, peoples and customs as well as about the forest. They handle the logistics and the planning of meals, in particular, as well as of the itinerary, breaks and camping. The guides are closely associated with the forest, which they know so well that they find all the resources needed for adventure there. They teach tourists about nature and the forest itself (medicinal plants, protected area, animals), which contains an abundance of useful resources for “survival,” but is also portrayed as a wild, overgrown realm that is hard to reach without strenuous effort – and consequently a good place for adventure and discovery.

The cultural experience, on the other hand, is concentrated in the villages, which constitute the destinations for the excursions. This is where the trek comes to a halt and the trekkers can rest. Reviewers write about the families and ethnic groups who inhabit the villages and about their personal experiences of staying in the villagers’ homes. The tourists take walks around, play with the children and, more rarely, discover handicraft activities there. Whether to aid local communities with donations is a controversial question that is often raised and debated. The village landscape is not mentioned in comments, just as cultural aspects go unmentioned in connection with the forest. On the whole, landscapes figure less prominently in the tourists’ reviews than in the agencies’ descriptions. Tourist feedback tends to be geared more towards giving recommendations and advice than subjective or aesthetic descriptions. Nevertheless, the corpus does convey how they experience the landscape concretely in their descriptions of local sporting practices and nature activities, which are foregrounded and considered as physical challenges. These comments are rounded out by certain reviews that relate the tourists’ sensory experience of the landscapes in the focus on the physical setting in which these activities take place.

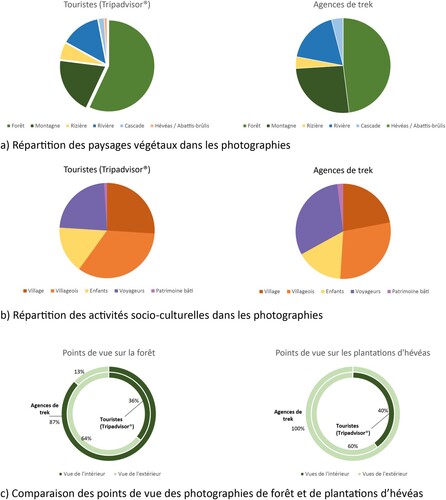

We also compared the 169 photographs posted by tourists on Tripadvisor® with the 91 photographs we found on local agency sites. They tend to foreground similar landscape motifs and social activities (a-b), though shot from different angles: the trekking experience is about discovering the forest from the inside, so local tour operators advertise “immersion in the jungle” with pictures taken mostly inside the forest, from under the trees (c). Tourists, on the other hand, seem to consider wider views more important, so they are three times more likely to post panoramas of the forest. This accords with the Western practice of hiking in the mountains to gain vantage points that offer a wide view of the landscape, which is rare in the forest. When it comes to rubber plantations, however, local tour operators use wide-angle shots to draw less attention to these monocultures (c): their canopy blends in with the green backdrop of the surrounding landscape, and while the neatly aligned rows of rubber trees are readily recognizable to the trained eye, most tourists looking at a photo shot from above or from afar merely see a forest, not a plantation. On the other hand, more than one-third of the photographs of rubber trees posted by tourists are obviously from inside the plantations, especially as they usually show the cups attached to the tapped trunks. The same goes for the rice paddies, which local operators photograph from a distance, whereas over three-fourths of the tourists’ pictures show much closer views of rice sheaves or locals working in the fields, which suggests that tourists are in fact curious about unfamiliar farming practices.

Villagers seeking comfort and modernity

Most of the villagers say the forest is the most beautiful of all landscapes. This aesthetic appreciation tallies with their utilitarian view of and economic interest in the forest, which supplies most of their foodstuffs and cash income (Poinsot Citation2008; Caillault and Marie Citation2009). They also appreciate the beauty of their lowland rice fields, especially when the plants have grown high just before the harvest. On the other hand, they reject shifting cultivation landscapes, which they equate with hard toil, low productivity and meager earnings. The only advantages cited are the possibility of growing a variety of vegetables there and the different flavor of the rice grown there. However, since shifting cultivation is officially condemned and prohibited, it is difficult to get Laotian villagers to express their opinions on it freely and frankly, especially in the presence of an interpreter from the city. In any case, there is a close correlation between farming and making a living off the land, and aesthetic appreciation of the landscapes (Blanc-Pamard and Milleville Citation1985; Deffontaines Citation1996), as evidenced by the villagers’ interest in cardamom plantations in the forest (high labor productivity: Ducourtieux, Visonnavong, and Rossard Citation2006). Rubber trees, however, although a significant source of income, are not aesthetically appreciated by all the villagers. Still, they are preferred to swiddens and fallows since rubber plantations require deforestation only once (rather than every seven years) and become integrated in the medium term as perennial wooded landscapes, in conformity with the official policy.

The inhabitants pointed out major changes in the landscape, both in the forest, with the introduction of rubber plantations and the diminution of wildlife, and in the modernization of villages, especially those near the highway, although more isolated villages are also modernizing by introducing manufactured materials (sheet-metal roofs, brick walls, satellite TV antennas, etc.). Hosting tourists in homestays has the effect of promoting these home improvements, host families are selected by the village headmen according to criteria laid down by the agencies, based on the house's size and comfort level (toilets, clean spacious rooms). The villagers themselves do not mention the architectural styles or traditional character of their houses. Nor do they show any interest in their village landscape, which some even consider dirty. In their view, the sites of interest are waterfalls and temples – without their villages. While the village headmen know what a tourist is – “someone who has to spend money on accommodation, food and amusement away from home” –, many villagers are confused about why the tourists come. They assume they come for the jungle and nature, but are amused at the tourists’ desire to scramble clumsily along steep slopes in temperatures more amenable to seeking a shady spot in which to cool off. The villagers are at a loss as to how to increase their income from tourism. In theory, hosting tourists overnight should promote sales of traditional hand-crafted products, but local production is very limited. In practice, more and more stalls in the village of Nalan Neua are vending industrially manufactured products (beer and instant coffee in particular).

Discussion

These different representations of the landscape pose a challenge to this model of ecotourism, which appears to be increasingly centered on the forest to the detriment of other motivating factors that were initially present. These discrepancies point up power relations that are unfavorable to local communities, who are accused of causing damage to the forest (Forsyth Citation2019; Menziès Citation2007; Ducourtieux Citation2015).

Conspicuous absence of cultural landscapes

The various actors agree on the primary interest of the forest landscape, beside which the villages and agricultural landscapes are relegated to secondary importance.

Controversial agroforestry landscapes

Except for rice paddies, agricultural landscapes are rarely mentioned by trekking agencies and some are avoided entirely, such as rubber plantations, which are too monotonous for tourists to appreciate: “Nice forests from time to time, but mostly it was rubber plantations and not primary forest”; “The rest was secondary forest or walking along fields. This is not what I came here for” (Tripadvisor®, MatthiasR, 2017). In 2014, the guides were concerned about an industrial plantation project undertaken by Chinese investors, which would involve building a road to the village of Nalan Neua – confirming threats to the NPA that Schipani had warned about several years earlier (Citation2007). The villagers themselves were in favor of such a road, however, as it would give them easier access to N3, and consequently to the city and its services. Some of them were not afraid of a decline in tourism, given the possibility of attracting new tourists arriving by car. The government eventually stopped the project in order to preserve the NPA – albeit after the road had already been opened. This outcome reassured some of the villagers who worried that, besides spoiling the forest, the project would also entail the use of pesticides and fertilizers.

Shifting cultivation is also controversial. Tourists’ feelings about the resulting landscapes vary according to the season and the appearance of the swiddens: the bare soil strewn with charred trunks in April and May makes for a desolate landscape, as opposed to golden rice fields swaying in the wind just before the October–November harvest (: “the beautiful yellow ready-to-harvest rice fields up the mountain” Tripadvisor®, DejntshiabL, 2017). The Tripadvisor corpus contains no explicit references to burnt swiddens: this may be due to avoidance strategies in charting the trekking routes (these landscapes seem not to have been noticed, or at least not sufficiently to detract from the tourists’ experience) or to the fact that tourists may have a hard time identifying and consequently talking about them. All the tourists interviewed on location deprecated these barren landscapes, although their views differed according to their degree of comprehension of this landscape type: the most critical among them attributed it to logging, while others said that, after receiving explanations from their guides, they understood the need for local communities to resort to such practices.

Although the guides talk at length about the forests, they seldom mention built landscapes, the use of pesticides in the farming of cash crops and some rice fields, or the rationality of shifting cultivation, although a number of researchers point out that these practices are widespread in sparsely populated regions (Ducourtieux Citation2015). Some visitors perceive this protected area as a reserve devoid of human residents, much the way that similar projects have been promoted on the African continent (Blanc Citation2020). As a result, tourists raise questions about the existing villages, however few and far between: “These are not national parks since people live there in remote villages and can work the land.” They feel this tourism project should allow for farming, especially as it contributes to landscape diversity: “The scenery changed a lot from deep jungle to rice fields with a beautiful view up and down.” Furthermore, these are in fact secondary forests resulting from anthropogenic disturbances over a long period of time (Froment and Bahuchet Citation2003; Ducourtieux Citation2015).

The place of minorities

The guides present a world in which villagers draw on the forest for their resources, which largely reflects the reality on the ground: dietary diversification is heavily dependent on gathering foodstuffs provided by the forest (Broegaard et al. Citation2017; Kaufmann Citation2008). However, this portrayal overlooks agricultural practices, including rice-growing, that constitute the staple food. Rice is the mainstay of the three daily meals for villagers as for trekkers, and yet its quality and origins are not specifically discussed. The produce and landscapes are disregarded and unappreciated by tour operators, who primarily bank on the “jungle” experience, whilst the villagers, who are unfamiliar with the practices of the tourist business, receive no support in their efforts to offer products and activities likely to catch the tourists’ attention.

As a result, many tourists complain of boredom upon arriving in the village: a village tour only takes a few minutes and there is not much to do there afterwards while the guide is busy seeing to the logistics of dinner and overnight accommodation. Some tourists would be keen on a more immersive village experience, in which they could learn about local arts and crafts and “farm work.” Kleinod (Citation2017) enumerates the many obstacles to authentic interaction between tourists and villagers. Small-scale production does exist, but the villagers’ functional wickerwork (baskets, animal cages, fish traps, etc.) are not adapted in size to the sort of souvenirs desired by trekkers. Although manufactured goods are increasingly present in their daily lives, the villagers still show pride in making various objects by hand. The mismatch between supply and demand for handicrafts in the trekking villages contrasts with a more cultural tourism developing in the Luang Namtha plain around rice paddies, temples and, above all, villages accessible by rented bicycle or motorcycle and without a guide, a model for tourists less intent on the adventure of trekking through the jungle. The specific local products made by hand for them include paper, scale basketwork and woven fabrics, among other things.

Despite the relative lack of interaction, trekking tourism has brought about changes in village life. Villagers themselves note changes resulting from efforts to attract tourists: animals are now tied up or penned, for example, which contributes to the cleanliness of the villages. Although these changes are part of the administration's health policy, the villagers associate them above all with the need to make their villages more welcoming to foreigners. A small number of tourists do show an interest in the local habitations, especially in the houses built on stilts. Given the relative modernity of the villages built along N3 (with brick houses and sheet metal), their appearance no longer conforms to the traditional image marketed by travel agencies. The same goes for clothing: locally woven garments have been largely supplanted by globalized Chinese mass-produced clothes, with the exception of women's apparel in certain remote Akka villages. Failing to offer any of the “folkloric” features expected, the villages are losing ground among the regional assets highlighted by agencies, even as they benefit from increasing demand for adventure sports rather than culture and authenticity.

Falling back on the forest, a fragile resource

Now that the subtle mix of landscapes initially promoted is being eroded and challenged, regional advertising efforts increasingly focus on the forest. Instead of promoting agro-pastoral landscapes shaped by local communities, as is common practice in the Western tourism sector (e.g. Garrod, Wornell, and Younell Citation2005; Daugstad Citation2008), the object is now to market the wilderness experience. Despite the creation of the NPA, however, the forest is threatened by various contemporary dynamics (Bernard, Roche, and Sarrasin Citation2016). Luang Namtha is presented as a “nature” destination in which to immerse oneself in the “jungle,” whose most conspicuous (and accessible) features are its gigantic old-growth trees and diversity of insects. Although some attributes of the wilderness are not always observable (“almost no animal crossed”; “we did not see any wild animals”), several means can be employed to boost the image of this destination nevertheless. The very existence of the NPA and its boundaries are the most effective “selling point” for this wilderness identity (). Several tourists point out the need to explore this protected area:

The Nam Ha NPA is wild! One of the last spots in SE Asia where to have real fun and observe primary forest. Just … Be Careful! Most of the companies will lie to you and tell you that they will bring you here … it is not true! You will see rubber trees all along the way. (Tripadvisor®, fabulousA, 2016)

The guide as a local relay

Trekking is conceived of as an adventure which, however, must be kept safe and controlled. Hence the primary importance of the guide, who figures prominently in the discourse of the various actors. This is indeed a peculiarity of ecotourism, which relies on “relays” to share knowledge about the local environment and culture while leading visitors through that environment and culture. The guide is the spokesman and ambassador of the protected area as well as the competent organizer of the expedition. This is why all treks are guided: visitors are not allowed to venture into the forest alone (and would have a hard time finding their way through it due to the absence of marked trails, maps, signs, etc.). On the other hand, this also constitutes a limitation on the “jungle experience”: most trekkers are young backpackers, often more inclined to explore on their own. So the requirement of a guide runs contrary to their inclinations – and their limited budgets. Older tourists, who usually have bigger budgets but only visit Luang Namtha as one stop on an extended, wide-ranging itinerary, tend to be less keen on long hikes of several days’ duration on slippery terrain infested with leeches, and more interested in discovering the traditional architecture, dress and handicrafts of the local villages by bicycle or even by minibus. In order to offer affordable rates for backpackers, the agencies are increasing the number of customers per trek and per guide. But larger groups distort and detract from the adventure of a “jungle experience”: “We were actually 11, too many to be quiet enough to see animals in the forest” (Tripadvisor®, mh, 2014). The guide brings the wilderness to life through activities that resemble hunting, “pointing out animal tracks and all around making the forest come alive” (Tripadvisor®, willpeever, 2017). As a result, visitors are offered more an experience in nature (rafting, kayaking, camping, picnicking etc.) than of nature itself.

The guide also serves as a link to other local actors. He mediates relations between visitors and villagers during the trek, serving as an interpreter to facilitate communication between them and coordinating services involved in accommodating the visitors. The guides are, in a word, at the interface between Western tourists and local villagers. But some also provide services for and address the concerns of other foreigners, including NGO naturalists or scientists (such as ourselves) working inside the NPA. At the intersection of several different models of representation, they help to spread an environmentalist view of the forest, raising awareness among local communities of the consequences of deforestation by pointing up its economic impact on tourism (hence the need to preserve attractive landscapes) and, more fundamentally, warning about the depletion of resources (fauna, flora, timber). Consequently, they serve as effective relays for government policies and urban discourse (Menziès Citation2007).

Jungle trek in Luang Namtha: a lack of decisive comparative advantages

In Luang Namtha, the dominant tourism model in discourse (albeit not in fact) is trekking, which depends on a shared resource in Northern Laos: the forested mountain landscape. While Luang Namtha is the first region to have developed this product, other regions now offer similar experiences. Compared to the neighboring provinces of Oudomxay and Phongsaly, which feature similar landscapes with some added attractions (waterfalls, hot springs, “more authentic” minorities), Luang Namtha has only a slight advantage over its domestic competitors: accessibility via Route 3. However, other mountainous provinces (Luang Phrabang, Xiangkhouang) in Northern Laos are more accessible and capture most of the incoming tourism. At the international level, Northern Laos suffers from competition with more emblematic destinations in terms of biodiversity such as Costa Rica (Carvache-Franco et al. Citation2020; Jones and Spadafora Citation2016) and other countries featuring large, more accessible and visible wildlife. Despite the creation of the NPA, this relative disadvantage is exacerbated by a marked reluctance among young tourists to sign up for extended – thus costlier – treks, which, however, represent the only way of penetrating deep into the forest to reach more pristine and richer wildlife. As a result, the program may end up falling short of their expectations and the agency's promises. The treks run along rows of rubber trees for a long time, merely skirting the forest, which consequently appears to be a relatively homogeneous landscape easily replaceable by other destinations. The forest landscapes advertised by the agencies are not compelling enough to attract tourists without emphasizing the local cultural attractions (ethnic minorities) as well.

In terms of international competition, the treks offered at Luang Namtha bear no comparison to destinations offering more grandiose nature and more spectacular outdoor activities elsewhere in Asia, such as in the Himalayas of Nepal, for example (Gauché et al. Citation2019). Comments on the technical difficulties and durations of treks in Luang Namtha vary considerably: some describe them as quiet hikes while others warn of their strenuousness and difficulty (“slippery paths,” “steep, wet, muddy slopes,” “walk too fast” etc.). Furthermore, several tourists point out the absence of scenic views: “Obviously you are in ‘jungle territory’ so this is not for you if you want meandering walks with panoramic views” (Tripadvisor®, t2000Surrey, 2013); “If you’re looking for a relaxed walk through beautiful scenery and panorama views, you should probably choose something else” (Tripadvisor®, fhsch, 2013). The forest lacks both vistas and singular landmarks, with the exception of “giant trees,” which makes it more of a vast composite, a mosaic of images, than a landscape per se (Descola in Lévi-Strauss, Descola, and Glowczeski-Barker Citation1991). Tourists have to put in a special request to obtain a panoramic view: “We asked the manager for a two-day trek in the forest, a little harder than usual in order to be able to spend the night at the top of the mountain and have a beautiful panoramic view” (Tripadvisor®, simoom, 2016). The agricultural landscapes, especially swiddens and recent fallows, are crucial clearings in which to enjoy views of the forest, as Kleinod (Citation2017) points out. Ultimately, it seems that Luang Namtha should stress its assets at the interface between nature and culture:

You can find both with the Nam Ha river ecotourism project: a beautiful nature, preserved from deforestation, in specific areas, and the cultural aspect of the local life. It is a way to link nature and culture, and to get involved in a larger touristic logic. (Tripadvisor®, arthurB3556, 2016)

Conclusion

The development strategy implemented by the Luang Namtha local authorities is based on two approaches. One is the promotion of the Nam Ha NPA and the ecotourist project for preserving biodiversity while improving the villagers’ livelihood. The other is to promote cash crops for export (e.g. rubber plantations) in the same area, although it implies revising and adapting the NPA rules and limits. However, the two approaches are mutually exclusive; the landscape repercussions of the second are detrimental to the tourist attractiveness for the first one. The local authorities must make a tough choice between the two development options, but each contributes to increasing socio-economic inequality within the villages in the NPA. Wealthy households can accommodate tourists or invest in cash crops, while the poor are most restrained by the conservation rules (e.g. ban of shifting cultivation or forest foraging). The landscape may be mobilized as an operational local-level dialogue tool in role-playing games to forecast the impacts of the different development options, to select the most suitable.

The research has also shown that the initial dual objective of the ecotourist project slipped towards the sole forest conservation one. The landscape has been reduced to the single natural component, showing how pervasive the occidental dichotomy of Nature and Culture is. Although ecotourism is often associated with the promotion of cultural landscapes – i.e. human-made – for example, in Europe (e.g. vineyards, cultivated terraces) as well as in Asia (e.g. paddy field; Gao, Lin, and Zhang Citation2021), they are left aside in the studied model. Here, the occidental imaginary of exotism and adventure projects in an ideal of the virgin forest; it meets with the environmental discourse on forest conservation that chastises the village communities for their alleged role in deforestation. At the forefront of the ecotourist project, the forest in North Laos is nevertheless an outcome of anthropogenic activities, a “taskscape” according to T. Ingold (Citation2002). Hence, promoting the “natural” landscapes for tourism contributes to marginalizing the ethnic minorities as long as their forest and agricultural practices are deemed contrary to environmental conservation. Rather than opposing these dimensions, it seems more fertile to recognize their complementarity. Our findings thus approach the proposals of Thompson et al. (Citation2016), inspired by the concept of tourist gaze (Urry Citation1992), which decompose the landscape into three components: naturescape, farmscape, and culturescape.

Approaching ecotourism by the landscape and its representations gives new insight into the limits of the concept. It highlights how ecotourism may mismatch with the material reality – a source of disappointment for tourists – as well as between the tourism imaginaries and the everyday life of local people. It questions their place and role within the promoted ecotourist model. More fundamentally, the landscape approach unveils a double gap: a conflict at the local scale between incompatible development programs; at a larger scale, the dissemination of the occidental Nature–Culture dualism deepens local communities’ marginalization.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marie-Anne Germaine

Marie-Anne Germaine (PhD) is an associate professor at Paris Nanterre University. Her research at the laboratory UMR LAVUE 7218 CNRS focuses on the interface between environmental issues, landscape amenities and local development in “ordinary” areas, as well as the ways in which environmental concerns inform landscape representations and conflicting models of representation.

Olivier Ducourtieux

Olivier Ducourtieux (PhD) is currently associate professor in comparative agriculture. After having implemented rural development projects in Northern Laos for 15 years, he joined AgroParisTech and the UMR Prodig to focus his research on the relationships between the State and the Highlanders in Southeast Asia, especially on the historical building of the policies on development and environment, and their impact on villagers’ practices and upland landscapes.

Jessica Orban Stone

Jessica Orban is a graduate from Paris Nanterre University in geography, land planning and local development with a minor in water management. Her M.A. led her to focus mainly on global discourse on and local perceptions of ecosystem services.

Xavier Cournet

Xavier Cournet is a graduate from the Nature and Landscape School of Blois in landscape design (France). He did an internship in the program ANR AQAPA.

Notes

2 The platform has several different sections: we confined our assessment to the tourist reviews (and disregarded reviews of hotels and restaurants). https://www.tripadvisor.fr/Attractions-g424933-Activities-Luang_Namtha_Luang_Namtha_Province.html.

3 https://www.evaneos.fr/laos/itineraire/9175-nature-passionnement/ (description of the stay “Laos Nature passionately”).

4 Sources: Provincial Tourism Department surveys (2014 and 2018).

5 With the GTP system, the geographer G. Bertrand associated three close concepts to propose a systemic approach: the geosystem, the territory and the landscape. This proposition is either methodological and epistemological and aims to cross the dualistic separation between nature and culture.

References

- Adams, C., L. Chamlian Munari, N. van Vliet, R. S. Sereni Murrieta, B. A. Piperata, C. Futemma, N. Jr. Novaes Pedroso, C. Santos Taqueda, M. Abrahão Crevelaro, and V. Luísa Spressola-Prado. 2013. “Diversifying Incomes and Losing Landscape Complexity in Quilombola Shifting Cultivation Communities of the Atlantic Rainforest (Brazil).” Human Ecology 41 (1): 119–137.

- Bernard, S., Y. Roche, and B. Sarrasin. 2016. “Écotourisme, aires protégées et expansion agricole: quelle place pour les systèmes socio-écologiques locaux.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 37 (4): 422–455. doi:10.1080/02255189.2016.1202813.

- Berque, A., ed. 1994. Cinq propositions pour une théorie du paysage. Ceyzérieu: Champ Vallon.

- Bertrand, G. 1991. “La nature en géographie. Un paradigme d’interface. Savoirs hybridés, savoirs débridés.” Geodoc: Documents de recherche de l’UFR “Géographie et aménagement,” Université de Toulouse-Le Mirail 34.

- Blanc, G. 2020. L’invention du colonialisme vert, Pour en finir avec le mythe de l’Eden africain. Paris: Flammarion.

- Blanc-Pamard, C., and P. Milleville. 1985. “Pratiques paysannes, perception du milieu et système agraire.” In À travers champs. Agronomes et géographes. Dynamique des systèmes agraires, 101–138. Paris: ORSTOM.

- Brandt, J. S., and R. C. Buckley. 2018. “A Global Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence of Ecotourism Impacts on Forests in Biodiversity Hotspots.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 32: 112–118.

- Broegaard, R. B., L. Vang Rasmussen, N. Dawson, O. Mertz, T. Vongvisouk, and K. Grogan. 2017. “Wild Food Collection and Nutrition Under Commercial Agriculture Expansion in Agriculture-Forest Landscapes.” Forest Policy and Economics 84: 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2016.12.012.

- Caillault, S., and M. Marie. 2009. “Pratiques agricoles, perceptions et représentations du paysage: quelles articulations ? Approches croisées Nord/Sud.” Norois 213: 9–20.

- Carvache-Franco, M., A. J. Pérez Orozco, O. D. Carvache-Franco, A. G. Víquez Paniagua, and W. Carvache-Franco. 2020. “The Perceived Value in Ecotourism Related to Satisfaction and Loyalty: A Study from Costa Rica.” Geographica Pannonica 24 (3): 229–243. doi:10.5937/gp24-25082.

- Catibog-Sinha, C., and J. Wen. 2008. “Sustainable Tourism Planning and Management Model for Protected Natural Areas: Xishuangbanna Biosphere Reserve, South China.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 13 (2): 145–162.

- Cochet, H. 2015. Comparative Agriculture. Berlin: Springer/Quae.

- Comby, E. 2013. “Les discours de presse sur les reconquêtes du Rhône lyonnais (Le Progrès 2003–2010).” Géocarrefour 88 (1): 31–43.

- Cottet, M., A. Rivière-Honegger, A. Evette, F. Piola, S. Rouifed, F. Dommanget, L. Vaudor, and J. Valy. 2018. “Représentations et pratiques de gestion des renouées asiatiques: intègrent-elles les dynamiques à long terme des écosystèmes?” Géocarrefour 92 (1). doi:10.4000/geocarrefour.10451.

- Crompton, J. L. 1979. “Motivations for Pleasure Vacation.” Annals of Tourism Research 6 (4): 408–424.

- Daugstad, K. 2008. “Negotiating Landscape in Rural Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2): 402–426.

- Deffontaines, J.-P. 1996. “Du paysage comme moyen de connaissance de l’activité agricole à l’activité agricole comme moyen de production de paysage. L’agriculteur producteur de paysages. Un point de vue d’agronome.” Comptes rendus de l’Académie d’agriculture de France 82 (4): 57–69.

- Dérioz, P., P. Bachimon, and E. Gauché. 2020. “Le paysage comme ressource touristique des espaces ruraux: Perspectives de l’Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est.” Via (Tourism Review) 17/2020. doi:10.4000/viatourism.5062.

- Descola, P. 2005. Par-delà nature et culture. Paris: Gallimard, Collection Bibliothèque des Sciences humaines.

- Ducourtieux, O. 2013. “Lao State Formation in Phôngsali Villages: Rising Intervention in the Daily Household and Phounoy Reaction”. Asian Studies Review 37 (4): 451–470.

- Ducourtieux, O. 2015. “Agriculture in the Forest: Ecology and Rationale of Shifting Cultivation.” In Handbook of Forest Ecology, edited by Kelvin S.-H. Peh, Richard T. Corlett, and Yves Bergeron, 573–587. London: Routledge.

- Ducourtieux, O., S. Sacklokham, and F. Doligez. 2017. “Eliminating Opium from the Lao PDR: Impoverishment and Threat of Resumption of Poppy Cultivation Following ‘Illusory’ Eradication.” In Shifting Cultivation Policies: Balancing Environmental and Social Sustainability, edited by M. F. Cairns, 647–670. Wallingford: CABI.

- Ducourtieux, O., P. Visonnavong, and J. Rossard. 2006. “Introducing Cash Crops in Shifting Cultivation Regions: The Experience with Cardamom in Laos.” Agroforestry Systems 66 (1): 65–76.

- Fletcher, R. 2009. “Ecotourism Discourse: Challenging the Stakeholders Theory.” Journal of Ecotourism 8 (3): 269–285.

- Forsyth, T. 2003. Critical Political Ecology: The Politics of Environmental Science. Routledge: London.

- Forsyth, T. 2019. “Beyond Narratives: Civic Epistemologies and the Coproduction of Environmental Knowledge and Popular Environmentalism in Thailand.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (2): 593–612.

- Froment, A., and S. Bahuchet. 2003. “L’Homme suit-il les forêts?” La Recherche HS°11: 20–25.

- Gao, J., H. Lin, and C. Zhang. 2021. “Locally Situated Rights and the ‘Doing’ of Responsibility for Heritage Conservation and Tourism Development at the Cultural Landscape of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29 (2-3): 193–213.

- Garrod, B., R. Wornell, and R. Younell. 2005. “Re-conceptualising Rural Resources as Countryside Capital: The Case of Rural Tourism.” Journal of Rural Studies 22: 117–128.

- Gauché, É. 2015. “Le paysage existe-t-il dans les pays du Sud ? Pistes de recherches sur l’institutionnalisation du paysage.” VertigO 15 (1). doi:10.4000/vertigo.16009.

- Gauché, É., S. Déry, P. Dérioz, O. Ducourtieux, M.-A. Germaine, F. Landy, M. Loireau, and L. Verdelli. 2019. “Culture du paysage, gouvernance territoriale et mise en tourisme dans des montagnes rurales de l’Asie méridionale (Népal, Inde, Chine, Laos, Vietnam).” Développement Durable et Territoires 10 (2). doi:10.4000/developpementdurable.14449.

- Germaine, M.-A. 2011. “Apport de l’analyse de discours pour renseigner les représentations paysagères et les demandes d’environnement. Exemple des vallées du nord-ouest de la France.” Annales de géographie 6: 629–650.

- Harrison, D., and S. Schipani. 2007. “Lao Tourism and Poverty Alleviation: Community-Based Tourism and the Private Sector.” Current Issues in Tourism 10 (2-3): 194–230.

- Hedemark, M., and U. Vongsak. 2003. Wildlife Survey of the Nam Ha National Protected Area: Wildlife Observation from 4 Areas of the Nam Ha National Protected Area in March 2002. Vientiane: Wildlife Conservation Society-Lao Program.

- Higham, J. E., ed. 2007. Critical Issues in Ecotourism: Understanding a Complex Tourism Phenomenon. London: Routledge.

- Hoang, H. T. T., V. Vanacker, A. van Rompaey, K. C. Vu, and A. T. Nguyen. 2014. “Changing Human–Landscape Interactions After Development of Tourism in the Northern Vietnamese Highlands.” Anthropocene 5: 42–51.

- Ingold, T. 2002. The Perception of the Environment. London: Routledge.

- Ishida, M. 2019. “GMS Economic Corridors Under the Belt and Road Initiative.” Journal of Asian Economic Integration 1 (2): 183–206. doi:10.1177/2631684619894102.

- Johnson, A. 2000. “Use of a Conceptual Model and Threat Assessment to Design and Monitor Effectiveness of the Nam Ha National Biodiversity Conservation Area, Lao PDR.” In The World Commission on Protected Areas, 2nd Southeast Asia Regional Forum, Vol. 2, 356–364.

- Jones, G., and A. Spadafora. 2016. “Creating Ecotourism in Costa Rica, 1970–2000.” Enterprise and Society 18 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1017/eso.2016.50.

- Kaufmann, S. 2008. “The Nutrition Situation in Northern Laos: Determinants of Malnutrition and Changes After Four Years of Intensive Interventions.” PhD thesis, Justus Liebig University Giessen.

- Keovilay, T. 2012. “Tourism and Development in Rural Communities: A Case Study of Louang Namtha Province, Lao PDR.” PhD thesis, Lincoln University.

- Khamvongsa, C., and E. Russell. 2009. “Legacies of War: Cluster Bombs in Laos.” Critical Asian Studies 41 (2): 281–306.

- Kladou, S., and E. Mavragani. 2015. “Assessing Destination Image: An Online Marketing Approach and the Case of TripAdvisor.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 4: 187–193.

- Kleinod, M. 2017. The Recreational Frontier-Ecotourism in Laos as Ecorational Instrumentality. Göttinge: Universitätsverlag Göttingen. doi:10.17875/gup2017-1006.

- Landy, F., R. Chand, S. Déry, P. Dérioz, O. Ducourtieux, N. Garambois, E. Gauché, M.-A. Germaine, M. Létang, and I. Sacareau. 2020. “Can Landscape Empower Rural ‘Minorities’ Through Tourism? Eco-Ethnicity in the Highlands of India, Nepal,China, Laos and Vietnam.” 2020. CSH-IFP Working Papers n°17. Pondichéry: Institut Français de Pondichéry. 31 p.

- Lane, B. 1994. “What is Rural Tourism?” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2: 7–21. doi:10.1080/09669589409510680.

- Larrère, R. 2004. Communication orale, colloque L’évaluation du paysage: une utopie nécessaire?, 15–16 janvier, Montpellier.

- Lee, A. K., and R. A. Abrahams. 2018. “Naturalizing People, Ethnicizing Landscape: Promoting Tourism in China’s Rural Periphery.” Asian Geographer 177–196.

- Lévi-Strauss, C., P. Descola, and B. Glowczeski-Barker. 1991. “Les sociétés exotiques ont-elles des paysages? Débat.” Études rurales 121 (124): 151–158.

- Li, Y. 2011. “Ethnic Tourism and Cultural Representation.” Annals of Tourism Research 38 (2): 561–585.

- Lu, W., and S. Stepchenkova. 2015. “User-Generated Content as a Research Mode in Tourism and Hospitality Applications: Topics, Methods, and Software.” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 24 (2): 119–154.

- Lyttleton, C., and A. Allcock. 2002. Tourism as a Tool for Development. Vientiane: UNESCO/Lao National Tourism Authority/Nam Ha Ecotourism Project.

- Menziès, N. K. 2007. Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber: Communities, Conservation, and the State in Community-Based Forest Management. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Nahuelhual, L., A. Carmona, M. Aguayo, and C. Echeverria. 2014. “Land Use Change and Ecosystem Services Provision: A Case Study of Recreation and Ecotourism Opportunities in Southern Chile.” Landscape Ecology 29 (2): 329–344.

- Negura, L. 2006. “L’analyse de contenu dans l’étude des représentations sociales.” Sociologies. https://journals.openedition.org/sociologies/993.

- Poinsot, Y. 2008. Comment l’agriculture fabrique ses paysages: Un regard géographique sur l’évolution des campagnes d’Europe, des Andes, et d’Afrique noire. Paris: Karthala. 243 p.

- Rouré, H., and M. Reinert. 1993. “Analyse d’un entretien à l’aide d’une méthode d’analyse lexicale.” Actes du Colloque des secondes journées internationales d’analyse de données textuelles, 418–428. Paris: ENST.

- Sacareau, I. 2009. “Évolution des politiques environnementales et tourisme de montagne au Népal.” Journal of Alpine Research 97 (3). doi:10.4000/rga.1018.

- Schipani, S. 2007. “Ecotourism as an Alternative to Upland Rubber Cultivation in the Nam Ha National Protected Area, Luang Namtha.” Juth Pakai 8: 5–17.

- Schipani, S. 2008. IMPACT: The Effects of Tourism on Culture and the Environment in Asia and the Pacific: Alleviating Poverty and Protecting Cultural and Natural Heritage Through Community-Based Ecotourism in Luang Namtha, Lao PDR. Bangkok: UNESCO.

- Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Stoleriu, O. M., A. Brochado, A. Rusu, and C. Lupu. 2019. “Analyses of Visitors’ Experiences in a Natural World Heritage Site Based on TripAdvisor Reviews.” Visitor Studies 22 (2): 192–212.

- Suntikul, W., T. Bauer, and H. Song. 2009. “Pro-poor Tourism Development in Viengxay, Laos: Current State and Future Prospects.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 14 (2): 153–168.

- Taillard, C. 2005. “Le Laos à la croisée des corridors de la région du Grand Mékong.” In Le Laos, doux et amer, edited by D. Gentil and P. Boumard, 71–92. Paris: Karthala.

- Thompson, M., B. Prideaux, C. McShane, A. Dale, J. Turnour, and M. Atkinson. 2016. “Tourism Development in Agricultural Landscapes: The Case of the Atherton Tablelands, Australia.” Landscape Research 41 (7): 730–743.

- Tizard, R. 1997. A Wildlife and Habitat Survey of Nam Ha and Nam Kong Protected Areas, Louang Namtha Province, Lao PDR. Vientiane: CPAWM-WCS Cooperative Programme, Department of Forestry, MAF.

- Tuohino, A., and A. Hynonen. 2001. “Ecotourism—Imagery and Reality. Reflections on Concepts and Practices in Finnish Rural Tourism.” Nordia Geographical Publications 30 (4): 21–34.

- Urry, J. 1992. “The Tourist Gaze and the Environment.” Theory, Culture & Society 9 (3): 1–26.

- Weaver, D. 2002. “Asian Ecotourism: Patterns and Themes.” Tourism Geographies 4 (2): 153–172.

- Yang, H., R. Harrison, Z. F. Yi, E. Goodale, M. X. Zhao, and J. C. Xu. 2015. “Changing Perceptions of Forest Value and Attitudes Toward Management of a Recently Established Nature Reserve: A Case Study in Southwest China.” Forests 6 (9): 3136–3164.

- Yang, J., C. Ryan, and L. Zhang. 2013. “Ethnic Minority Yourism in China—Han Perspectives of Tuva Figures in a Landscape.” Tourism Management 36: 45–56.