ABSTRACT

Laws and institutions are ubiquitous in and transformative of development in ways that do not frequently present as commonly understood ‘law’, or are not foregrounded as such in development interventions. This article highlights fresh thinking from critical scholars that disrupts prevailing approaches to law and legality in development, in legal and in international development studies scholarship alike. Through the concepts of the ‘form to law’ and ‘forming of law’ in development, and the metaphor of the kaleidoscope, it offers one approach to analysing encounters within and between laws and the governance of development as a critical and reflexive project of disciplinary hiatus.

RÉSUMÉ

Les lois et les institutions sont omniprésentes dans le développement et le transforment de manières qui ne sont pas souvent présentées comme le « droit » tel qu’il est communément compris, ou qui ne sont pas mises de l’avant comme tel dans les interventions de développement. Cet article met en lumière les idées novatrices de chercheurs critiques qui perturbent les approches dominantes du droit et de la légalité dans le développement, tant dans les études juridiques que dans les études du développement international. Par le biais des concepts de « forme de droit » et de « formation du droit » dans le développement, et de la métaphore du kaléidoscope, il propose une approche à l’analyse des rencontres au sein de et entre les lois et la gouvernance du développement en tant que projet critique et réflexif de hiatus disciplinaire.

Introduction

Laws and institutions are ubiquitous in and transformative of development in ways that do not frequently present as commonly understood ‘law’, or are not foregrounded as such in development interventions. This subtlety and complexity make discerning the relationship between law and development theoretically and methodologically elusive. Unsurprisingly, assessments of the ‘state of the field’ of, or approaches to, international development studies have betrayed a notable absence of any serious examination of the role of law and regulation in development.Footnote1 One might speculate on reasons for this: the historical prominence within international development studies of economics, sociology and political science; the Anglo-American and continental European origins, and continuing orientation of a Western rationalist and positivist epistemology of development; and the continuing prevalence of mainstream over heterodox and critical perspectives on development. Conversely, within critical development studies a noted tendency is to rely on more traditional approaches to law, even while being critical of development and the role law plays in it. This Special Issue seeks to fill this gap by introducing fresh thinking on important, if frequently overlooked governance dimensions of international development that centre on law.

Though aimed primarily at an international development studies audience, the contributors also ‘speak back’ to legal scholarship, highlighting areas of tension and avenues where analysis and critique of the governance dimensions of development and of law's role therein have been absent or ambivalent, sometimes partial, and almost never pivotal. To do so, the contributors carefully develop bespoke methodological lenses and research methods that draw from critical strands of legal scholarship and from legal theory including feminist, Marxist, doctrinal, comparative, TWAIL (Third World Approaches to International Law) and transnational legal theory, as well as from insights from other disciplines that include history, institutional theory, economic theory, political economy, science and technology studies, and postcolonial studies. The articles apply a range of research methods including socio-legal and empirical research methods. In doing so, however, their contributions do not approach interdisciplinarity as either the linchpin of their engagement with law in development, or as instrumental to any sense of disciplinary anxiety and remediation in law or its study (Dubber Citation2014).Footnote2 Rather, they turn their attention inward in an attempt to carve out spaces within both legal and international development studies for greater engagement of questions of reflexivity and normativity in knowledge production (Riles Citation1994), seeking to resist the hegemony of liberal normativityFootnote3 and of instrumentalism (Riles Citation2006) that prevails and warps judgment in both. This is prompted by a recognition of the existence of an animating if implicit aspiration at the heart of development, captured well in Beard's assertion that ‘Development is transcendence: the place that everyone is trying to get to, to complete themselves. Development is desire – the desire to become that which language promises but never achieves’ (Beard Citation2007, 15). Such an aspiration is also paralleled in the idea of a deferred (im)possibility of justice that animates Law (Fitzpatrick Citation2001, 73–76). We explain the significance of the relation between these parallel dimensions to law and development in the next section.

Governance as lens and the role of/for law

Recent years have witnessed growing engagement between the field of scholarship and practice known as ‘law and development’ and a body of work that probes the relationship between law and governance at levels and scales transcending the nation state, through instruments of rule that include and challenge inherited understandings of the nature and content of ‘law’ and ‘legality’.Footnote4 At the same time, critical attention is being paid to the politics of ideas about development and the ways that particular kinds of development are promoted that underpin and direct this engagement. These trends offer revealing insights into two facets of emerging research on laws, and how they relate to development. First, they highlight the significance – to questions of governance – of legal, economic, and political ideas on the nature of development and its direction to particular ends, and how these underpin and usurp models of development. Within these ideas, the role of/for law, regulation and other instruments of governance comes to the fore. Second, they highlight the under-recognised and under-theorised role of development as a project of governance in itself: how development rationalises, frames and is key to how rights, subjectivities, and relations between entities such as states, peoples, markets, and the environment are conceptualised, distributed, and institutionalised within and across existing governance registers via the rubric of ‘development’.

We suggest that a focus on governance is an insightful and productive entry point to identify, unravel, and examine, in tandem, the following interconnected dimensions. These are, first, the role ascribed to laws and institutions in development, and secondly, the ideas about and models of development that demand a particular response by laws and other actors and instruments of governance. Instead of a traditional beginning in laws and institutions, however, we meditate ‘slantwise’, as Buchanan, Motha and Pahuja enjoin us to do, on what we may learn by thinking with and about these through a cognate concept such as ‘governance’ (Buchanan, Motha, and Pahuja Citation2012, 13). A deliberate exercise in disciplinary hiatus, this Special Issue proposes that a focus on governance enables critical scholarship both in law and in development studies to grapple with the myriad legal, juridical, normative, and other dimensions to laws’ role in development, and to analyse their modes of engagement within development beyond a formalist, pragmatic, instrumental focus that prevails in mainstream debates in both fields.Footnote5

This intuition is informed by a definition of governance which, on the one hand, is capacious, viewing it as a form of ‘political ordering’ whereby ‘political’ stands for anything affecting the ‘public interest’ or the ‘common good’, variously conceived (Guzzini Citation2012, 3). On the other hand, ‘ordering’ implies a structured pattern to naturalised relationships amidst a plural normative universe, which – in the context of the ordering of the public interest or public good through laws – foregrounds an analysis of power and of the instruments, actors and institutions and their legal and juridical dimensions that create and maintain hierarchies between law and non-law, the economic and non-economic, rights and regulations, etc. (Zumbansen Citation2014; Pahuja Citation2007). Here, questions arise about who is doing this ordering and how their identity affects their access to power and resources. What are the instruments through which power is wielded and order created and maintained; what is their legal or juridical quality, and how do these relate to formal laws and institutions? What kind of power(s) (coercive, persuasive, productive) are being wielded and how is this power shaped by law? What are the distributional and other effects of this kind of ordering and how are rights and responsibilities shifted in the process?

These questions on the ideological function of ordering through law become more pressing and more complex when we recognise, as Peet and Hartwick do, that development is

… a complex, contradictory, contentious phenomenon, reflective of the best of human aspirations, and yet, exactly for this reason, subject to the most intense manipulation, liable to be used for purposes that reverse its original intent by people who feign good intentions in order to gain greater power. (Peet and Hartwick Citation2015, 4)

In recognition of the intimacy of the relationship between law and development, we take our baseline insight from the observation that when economists and development practitioners speak about law from the vantage-point of economic theory and institutional practice, they do not turn to a disembedded sphere or realm of thought outside those realms to mine ideas and concepts for their own use.Footnote8 Rather, in thinking through economic governance and its effects, they harbour legal ideas and argument and traditions of legal thought at every turn. Yet for all the talk about embedding legal analysis in economic thinking about development policymaking, seldom are these ideas and traditions the best available ones for understanding and effecting radical transformative change in economic relations (Kennedy Citation2013, 19–20; Rittich Citation2016, 838–840). Law, regulation, and other technologies of governance that accompany law are central to a process of mystification by which certain ideas about development become harnessed, legitimised and institutionalised. This Special Issue does not purport to approach these facets of ideas and practices of thought as necessarily always symbiotic – that depends on the particularities of issue and context, of course. But it does recognise that a relationship exists, and seeks to detail and analyse its features, dynamics, and effects to better elaborate their link with political and material outcomes through the rubric of development. An important impulse underpinning emerging research on these engagements aims at revealing and highlighting the political and distributional valence of the relationship between law, regulation and the governance of development, and the frequently overlooked opportunities for a productive engagement between ideas and heterodox and critical thinking in each (Kennedy Citation2013, 63–70; Alessandrini Citation2016).Footnote9

We propose that these governance dimensions to law in a development context contribute acutely to the ordering quality that is especially evident and potent in the framing and planning instruments ubiquitous in international development frameworks, plans, strategies, reporting, etc., implemented by a variety of actors. Development scholars from a range of critical perspectives have captured well how development itself as both a discourse and practice, creates and sustains normative agendas that value and rank different aspects of social, natural, and human life in ways that generate and perpetuate both positive outcomes and terrible inequities. Law, regulations, and other institutions of governance are central to this world-making exercise by how these establish, articulate, and implement a development agenda, making laws central to maintaining the inequalities and violence engendered by development. From reflection on and building on these foundations, we describe our approach to discerning and analysing law's role in the governance dimensions of international development in the following section.Footnote10

‘Form to’ and ‘forming of’ law in development – a kaleidoscope approach

Legal scholarship – and critical legal scholarship in particular – contains rich insights and debate on the nature of the legal form, though the meaning of the concept varies, depending on the nature of the enquiry.Footnote11 Here, we use the term ‘form’ (disentangled from the ‘legal’) to describe ‘the patterns of relations and subject positions to which these laws attempt to give shape’ (Orford Citation2006, 157). By ‘form to law’ then, we mean the ‘ordering’ of identities, status and relations created within and through law(s) deemed proper and desirable. Because of the temporal nature of law (over history, precedent etc.,) favoured forms change over time, and because of the layered and overlapping nature of laws (think of how municipal, national, regional, and international laws intersect and weave in the serving of food in a street-side café, for example), the form to law may not be necessarily harmonious or uncontested.

We use the term ‘forming of law’ to describe more acutely the detail of the interactions between laws and the ‘winds of development’. The latter refers to forces and imperatives within the wider context of development that shape laws. Thus, the concept of ‘forming of law’ attempts to trace and explain how the morphology of the law-development encounter intensifies the potency of the governance dimension to both. While we frame encounter in terms of ongoing rival jurisdictions (Pahuja Citation2013, 65), our focus is not between law and development, but within laws in development where both are sites of competing and overlapping engagements between different sources, forms, and formations of authority. This rivalrous understanding – within and between law(s) and development – introduces an element of instability, opportunity and ‘play’ and foregrounds points of tensions and conflict as entry points for analyses whose ‘technical’ aspects (as well as their legal and juridical dimensions) require deeper excavation and analysis. The term ‘encounter’ helps foreground the dynamic and ongoing nature of the relationship between law and development whose depth and range transcend conventional attempts to cabin them in preconceived frames.Footnote12 It emphasises relational dimensions to these encounters between different orderings, departing from mono-directional or hierarchical understandings of legal evolution and change (Bak McKenna Citation2021, 68, 74).

Our approach described above by use of the concepts ‘form to’ and ‘forming of’ law in development is thus distinct from both terms ‘legal form’ and ‘legal formalism’ prevalent in legal theory research and the tacit theorising of lawyers. We find the formal/anti-formal distinction unhelpful when the aim is to redirect, as well as deepen, inquiries into law's expanse in imparting legal forms to what is not already prefigured by an order of rules. In recognition of the distance between law's messiness in practice within the project of development, and its wider perception as an unalloyed good and a straightforward constituent and objective of development per se, we focus on governance dimensions to laws and institutions that their manifestations in a development context bring about. Here, we aim to discern the detail, in as much as possible, of how situated encounters within and between laws and development constitute and assume a governance potency and charge far greater than ‘the sum of their [its] parts’. While this ‘situatedness’ takes account of the contours of the political and material contexts of these encounters, it does not regard law as merely epiphenomenal or solely as an instrumental tool developmentalists may mechanistically apply according to type (contract law, property rights etc.) and level (municipal, national, regional, etc.) in an ever more detailed as-clockwork application of the doctrine of lex specialis. Rather, the messy and sometimes internally contradictory nature of law's plurality is taken seriously, with further recognition that law's dual potential for promise and perversity stems from the encounters between law's own internal features and the particularities of law's external political-economic context (Özsu Citation2010, 698–700, 702), themselves shaped by the determinants and desiderata of development's own exigencies. Here, law's internal features include how it ‘minds’ and ‘knows’ the lifeworld (Teubner Citation1989, 740), its quasi-procedural, formal internal structure, including its core principles and concepts and their normative hierarchies and relationships, and its modes of reasoning and imagination (Del Mar Citation2020).Footnote13

We speculate that the potent governance charge emerging from encounters between and within law(s) and development is intensified by features common to both in their contemporary manifestation. These include their intrinsic, morally oriented normativity; their political authority and grounding in wider society; their transnational reach and ability to transcend the local even while being inscribed in particular geographies and time; their internal rejuvenative dynamics that turn crisis and instability into opportunities to regain status and authority; as well as their shadow sides/sitings. This latter dimension includes their enabling of predatory and hierarchical patterns of governance across several axes, including of place (for example, of the Global North over the Global South, of core over periphery etc.,); of racism (Neajai Pailey Citation2020; Anantharajah Citation2021), patriarchy (Nazneen, Hossain, and Chopra Citation2019; Loomba and Lukose Citation2012), and colonialism (Mignolo Citation2007), underpinned by internalised economic and political logics that are dismissive and destructive of life (Mbembé and Meintjes Citation2003; Rapozo Citation2020). As has become increasingly clear of late, a major cleft in the shadow side/sitings of law and development is the patent inadequacy of mainstream thinking and practice in law and in development to engage with what Grear terms the ‘crisis of human hierarchy’ (Grear Citation2015, 227) that characterises the Anthropocene. In foregrounding critical analysis of the outcomes from encounters between and within law(s) and development, several of the contributions in this issue unravel new aspects, hidden dynamics, and dilemmas to the shadow side/sitings of law and institutions that, because of their location and ‘ground operations’ (Eslava Citation2015, 286) within a development context, assume added potency.

Kaleidoscope and the law-development-governance encounter

The metaphor we use to describe our analytical approach to the governance dimensions of the law-development encounter is that of the kaleidoscope. We do so for two reasons. The first is etymological, as the word ‘kaleidoscope’ is derived from Greek words kalos, meaning beauteous, noble or good, and eidos, meaning shape or form. Thus ‘kaleidoscope’ intuitively illustrates our quest to examine the form to and forming of law in a development context, while maintaining a critical stance towards the benevolence implied in development as a project, and towards law's role therein. The second reason is explanatory. A kaleidoscope is an optical instrument containing loose coloured pieces of (usually) glass, and two or more reflecting surfaces (mirrors) located at an angle such that the coloured objects on one end of the mirrors are seen as a symmetrical pattern when viewed from the other end. The number and angle of the reflecting surfaces are essential to the operation and effect of the kaleidoscope, as is motion. These elements – the number and angle of mirrors, the coloured pieces of glass, and motion – are key to the infinity and the symmetry of patterns that can be viewed, as is the centrality of form and forming to the instrument and experience of a kaleidoscope. However, each of these elements also represents constituent aspects of the law-development governance encounters explored in this Special Issue.

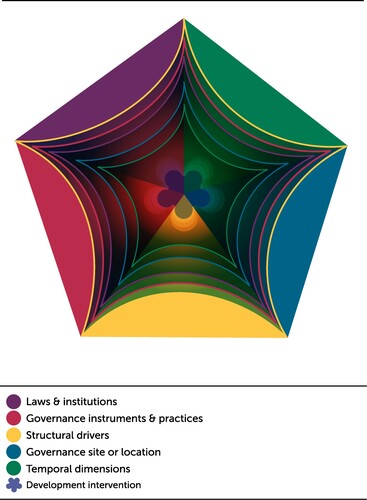

The number of angled mirrors of the reflecting surfaces of our kaleidoscope metaphor represent five vectors identified as foundational to the form to and forming of law that emerges from the law-development encounter and that are examined more deeply in each of the contributions. We explain these in more detail in the next section, but to summarise here, these include, firstly, the formal, recognised laws, regulations and institutions that are central to development, including the ‘internal’ dimensions to each of these. Second, there are the recognisably authoritative instruments and practices of governance augmented by laws, frequently characterised as ‘informal’ though they operate in close relation with formal law. Third, there are the structural, often implicit, ‘drivers’ to patterns of governance authority enabled by or manifest through laws shaped by the development context in question. In this Special Issue, three are explicitly examined – neoliberal ideology, colonial and imperial relations, and gender dynamics. Fourth, there are spatial dimensions (here, we focus on the significance of site and level at which the development intervention is planned or implemented), and finally, there are the temporal aspects of practices of governance, with both being central (if largely implicit) to the constitutive and normative dimensions of how laws and institutions govern in development. These five ‘higher-level’ vectors create a multidimensional concept of how encounters of laws with/in development effect a potent governance elixir (). Separately, and together, they create ‘angles’ of legal and juridical authority and meaning that bend and refract the possibilities of promise and perversity that are permissible in the dynamic crucible of development.

In considering the relationship between the vectors in the context of the law-development encounter, we are keen to recognise and stress their inter-relational and transversal manifestations and how these shape patterns to governance and their distributional outcomes. If the coloured pieces of glass at the centre of the kaleidoscope represent the particularity of the law-development encounter that emerges from the development intervention examined in each contribution, we allegorise that the motion that animates the kaleidoscope represents the potency and ripple effect of the governance dynamic generated by the engagements of the vectors in that encounter. What is key here are the relations and engagement between each vector and how these cumulatively shape the patterns of governance authority, altering the role and manifestation of laws and legality in a development context, though not in any simple causal or unidirectional way. How the vectors and the particularities of the development intervention therein engage together is key to law's governance role in a development context, yet impossible to easily atomise or anticipate. The patterns of engagement are potent and generative of law's and development's ability to consolidate or shift prior subjectivities and relationships, as well as evolve new ones. These patterns of engagement result in new relations of hierarchy, balance and alignment, contestation or harmony, rhythm, or rupture, and resistance. The significance of movement to changing the patterns presented within the kaleidoscope reflects the dynamism of law's encounters with development, while the governance effects of these encounters are captured by the actual changes to these patterns.

Law–development–governance: five vectors of significance

In our analysis, we mean those elements of forming central to the law-development encounters to be those that are key to shaping law's governance roles, manifestations, and effects in a development context. These are the primary constituent dimensions introduced or enhanced by laws that significantly affect and augment governance authority in a development context. Contrary to liberal approaches to law (which view law as distinct and separate from politics); mainstream approaches to law (that continue to reify binaries such as national/international; public/private; civil/criminal; hard/soft etc.) and instrumental approaches to law (which view law as a mere instrument of prevailing political and economic power), we hold that in a development context, the forming of law takes a more complex, dynamic, and curious shape. As highlighted in the previous section, from the rich analyses provided across the seven contributions to this Special Issue, five vectors of particular significance emerge, and we describe these in greater detail below.

First, there are the formal, recognised laws, regulations, institutions engaged in the governance and implementation of a development agenda that involve identifiably legal (as commonly perceived) rules (including constitutions and national laws, for example, but also the web of transnational laws that facilitate the activities of TNCs); regulations and regulatory instruments, (such as registers of land and permits, contracts etc.), and their authority in governance derived from this formal legal quality. These contain an inherent legal rationality (an approach to rights, duties, responsibilities, communicated through legal concepts such as sovereignty and ownership; influential norms such as the rule of law, along with what counts as evidence and justification). These formal laws and institutions (whether at the fore or in the background) create the development context (e.g. such as markets) that engage and guide the decision-making and activities of development actors including public entities such as states and international development finance organisations, and private actors such as corporations, NGOs and multi-stakeholder partnerships, whose outcomes have real effects on people and communities.

What several of the contributors to this Special Issue point out, however, is how the implementation and effectiveness of these laws in a development context is highly context-specific and contingent. Their interaction, over time, leads to significant, unintended, and often hidden outcomes for the form that laws take. Thus, Giedre Jokubauskaite and David Rossati's analysis of the growing reliance on environmental and social policies by development finance institutions (DFIs) demonstrates an altering of the core quality of law through what they refer to as a juridified form of welfare interventionism. Here, law assumes a more interventionist role in society, especially in the production of more welfare-oriented standards. However, they caution against the optimism that has greeted these developments as progressive legal innovations by activist NGOs and other actors. Instead, by approaching these developments as evidence of ‘market patterns’ in a wider ‘marketplace’ of DFIs, they show how these legal innovations result in a perverse double outcome of facilitating the adoption by DFIs of tactics of legal avoidance (through for example, their resort to use of management tools instead of actionable standards), while channelling the efforts of activist NGOs towards further procedural commitments instead of substantive standards. In turn, juridification and legal avoidance require more resources and efforts to enable mobilisation by affected communities. This perversity of requiring the intervention of external actors such as well-resourced NGOs, while likely leading to questionable results for affected communities, is part of the hidden tragedy of juridification in international development finance.

Meanwhile, by employing a material constitutionalist lens, Jennifer Lander traces how the pursuit by states of a natural resource-based development model within a wider global political economy of extractivism subtly creates three legal-constitutional ‘pressure points’ that strike at the heart of the role and powers of institutions within the state, and rework political relations of authority. These include the sovereign powers of the legislature to allocate property rights such as mining licenses and to raise taxes; an altering of the balance of power between central and sub-national administrations through domestic demands for fiscal decentralisation, and the creation of new categories of legal and political recognition by the state for people in ways that shift rights and responsibilities from those of citizenship to that of stakeholder-based identity. In doing so, her innovative methodological approach exposes the porous boundaries between the political-economic and the legal, and between the distinction between the sub-national and the transnational, and the public and the private legal domains.

Secondly, and less immediately visible, are the recognisably authoritative instruments and practices of governance. Their characterisation as ‘informal’ (or as ‘non-legal’) belies their close relationship to formal law and institutions. Frequently, their operation might be authorised by a law, or an interpretation of the legal mandate of an institution. Equally, their ability to mimic features of law, and graft the authority of legal institutions such that their influence and legitimacy assumes law-like status, is also significant to their governance potency. Like formal laws and institutions, the operation of these instruments and practices is key to decision-making in development, as well as to the authority and legitimacy of decisions made and of decision-makers. Often operating at a meso-level, these are regularly transnational and, though mixed in nature, operate in tandem and layered ways that, over time, create an intricate, thick web of governance through the axis of development. Examples of such instruments and practices include the existence and operation of audaciously self-determined, yet highly influential, background (and ‘backstage’) ideas and practices (e.g. on the role of laws and institutions in development and, in particular, in projects of legal and institutional reform) (Boer and Stolk Citation2019). They also include organisations’ self-determined working procedures such as inter and intra-institutional, bureaucratic engagement processes that development actors frequently create to engage with other development actors. Here, the public/private distinction frequently becomes blurred along several dimensions as actors play a variety of roles simultaneously (e.g. DFIs, though formally public actors, act according to market diktats shared with private financiers in development), while operating in the shadow of the legal infrastructure by which global markets are constituted and governed (Riles Citation2011). These actors often act in concert through formal and non-formal institutions and forums, and shape and are influenced by a variety of governance instruments including knowledge instruments such as data, indicators and indexes, and subject matter expertise provided by ‘expert’ consultants.

Here, two contributions to this Special Issue in particular reveal and analyse new dimensions to these instruments and practices of governance.

Liam McHugh-Russell's careful reconstruction of Legal Origins Theory (LOT) excavates the rationales that were foundational to the World Bank's now-debunked Doing Business (DB) report, revealing how ‘governance by knowledge’ helps drive development-inflected legal reform. LOT provided significant intellectual heft to DB's normative project on legal reform, and in doing so, legitimated aspects of the Bank's approach to aid and lending that relied on DB assessments, including through its Country Policy and Institutional Assessments and benchmarking for IBRD loans. Moreover, by capturing how knowledge claims in a project like DB function through a ‘bricolage’ of data, technique, conceptual framing and convention, (rather than being grounded on a single, well-grounded model), his contribution points to the risk that the popularly-perceived ‘victory’ of the recent cancellation of the DB report is likely misplaced. The Bank has left the intellectual premises of LOT untouched, and the types of reform DB rationalises remain poised to be materialised through other means.

Meanwhile, in her analysis of meso-level governance of Official Development Assistance (ODA) by donors in the aid-recipient state of Tanzania, Siobhán Airey frames the governance of ODA as a juridical field to reveal and trace the layered and complex legal dimensions to ODA's governance role in ways that usually remain legally invisible or ‘adjacent’ to law. She asserts that a very real if subtle legal link exists in the simultaneous and selective presence and absence of law, between how ODA is governed and how ODA governs – where in the former, formal law appears largely absent, while in the latter, legal and institutional reform are central. This dual governance of/by dynamic effectively creates avenues of executive intervention by donors in the domestic laws and policies of Tanzania, in ways that remain hidden to legal and democratic institutions of that aid-recipient state. This is exemplified in links between the governance of donor-backed Tanzania's Public Financial Reform Programme and donor antagonism to Tanzania's attempts to reform its mining laws to strengthen its status, leverage, and outcomes of engagements with foreign private investors. Here, the juridical qualities to ODA's governance are significantly augmented by scalar and temporal dimensions to ODA's governance that remain hidden to orthodox legal analysis.

Thirdly, there are the structural drivers to patterns of governance authority enabled by or manifested through law that emerge from the particulars of the development context in question. These drivers include contours to ideologies that shape politics and public policy; to history, and to the influence of colonialism and imperialism in particular; to political economy; and to factors such as race and gender and other variables that structure the experiences and manifestations of development at different levels including the personal and familial, at the level of communities (whether of identity or place), as well as at levels of the national, regional, transnational, and others. They also include less visible drivers such as the internal dynamics that emerge from institutional competition over funding priorities with borrowing countries and other donors, or other engagements, such as material and ideational struggles for power, resources, and prestige within and between clusters of development actors (e.g. Santos Citation2006, 278, 290–292). Such drivers are key to how relative hierarchies of authority, normativity and influence that evolve and are manifest within development become stabilised, augmented by, or disrupted through laws and institutions, but are often overlooked wholly or partially by legal and development studies scholars alike.

While each of the contributions in this Special Issue address different aspects of these structural drivers within their respective analysis, three of the contributions foreground them.

On gender, Évelyne Jean-Bouchard's consideration of the significance to women's agenc(ies) and identit(ies) of an international political economy for law and legal and institutional reform in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), offers new conceptual and empirical insights to examine encounters between laws and gendered socio-economic and sexual life. Centring her analysis on the experiences of women as they navigate a complex, dynamic and legally plural terrain, and drawing from a richly described multi-level analysis, she reveals the complex interactions between laws and legal institutions that derive from an amalgam of a variety of legal interventions. These include those instigated by international actors such as donors and international organisations (that create top-down, national-law and legal administrative reform initiatives that reflect international norms and legal expectations on gender (in)equality); pre-existing formal institutions; and informal legal mechanisms such as the barazas or ‘peace courts’ in Goma, North Kivu, that have integrated women into their own courts practices. Her research reveals the adeptness and agency of women in navigating this terrain as they strategize to mobilise sufficient social capital to ensure favourable and meaningful outcomes. From this perspective, she questions the merits of a unilateral setting aside of prior customary legal institutions by international development actors. In response, she argues convincingly of the necessity of a more strongly anthropologically informed, feminist institutional analysis by law and development scholars to better understand these interactions.

On ideology, Honor Brabazon's article focuses on a classic area of law and development enquiry – the thorny issue of land reform (in this instance, Bolivia's National Institute for Agrarian Reform (INRA) law (1996)). However, rather than focus on the relative success or failure of that initiative, her analysis shifts instead to what is revealed about the development encounter between development policy and ideology, when a particular approach to a neoliberal model of development in post-1980s Latin America is examined through the lens of law's inner logics. Here, context matters. With the failure of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes in Latin America in the 1980s, land reform through law became a particularly potent site and instrument, respectively, of development intervention, through which popular inclusion in wealth generation through land redistribution could appear to be pursued, while being strategically resisted. These coalesced through an approach to market-led agrarian reform through land titling. Her article traces three ways that legal logics and the legal form of social regulation were mobilised to advance a neoliberal vision of society while minimising dissent, including a rearticulation of the state as an ‘independent arbiter’ instead of as an agent of the public interest; the creation of a false equality amongst political actors of very different economic means (large landowners and landless peasants); and the simultaneous technocratisation and juridification of agrarian reform by emphasising the allocation of title over redistribution.

Finally, on colonial and imperial relations, Radha D'Souza frames and juxtaposes two historical developments, the issuance of a Royal Charter by Elizabeth I in December 1600 to a group of London merchants that created the East India Company, and the coining of the term ‘neocolonialism’ by Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister of Ghana who led the Gold Coast, a British colony, to independence in 1957. In her account, both are legally loaded actions whose ramifications for deeper, critical understandings of the nature of laws and institutions, and fundamental legal entities, identities, and concepts such as states, sovereignty, and the distinction between public and private, have failed to be substantively engaged with by orthodox law and development scholarship. She traces how four features of law and development scholarship (its identity, its approach to history, to questions of methodology, and to interdisciplinarity) operate as ‘picket-fence’ boundaries, constraining scholarly debate and critical engagement within that field, limiting its approach to law and legality to that of liberal orthodoxy, and its politics to that of pragmatic reform. By engaging with longue durée economic and legal histories, and reframing Nkrumah's and Third World critique more generally as substantive legal- and political economic critique and not political rhetoric, she illustrates and connects two seemingly disparate yet influential structural drivers. The first is the centrality of colonialism and imperialism to contemporary manifestations of legal, political, and economic relations; the second is the political economy of knowledge production and education on law and on development itself, which shapes what gets considered to be relevant for enquiry, and how this enquiry should be undertaken, in both of the fields of law and development, and international development studies.

Fourth, there is the significance of the level or site of governance encounter at which the confluence of laws and development comes into sharper relief or effect, highlighting the importance of recognition of the ‘glocal’ (Roudometof Citation2016; Swyngedouw Citation2004) nature of laws and of development. Here, scale and place are key to understanding and constructively engaging with the processes – frequently transnational and global in nature – through which material, social and other opportunities are created, maintained, and resisted within and alongside laws. Recognition of the glocal in a development context means that sites and locations of development can engage and effect development differently. Thus, though the ‘origin’ of a development initiative may be both ‘international’ and ‘universal’, its realisation and manifestation at national or local level may diverge significantly. Indeed, recognition of the glocal dimension opens up wider terrain for engagement, not only with considerations of power and agency, as well as opportunities for contestation and dissent, but also reimaginings of subjectivities and relations ascribed in a development context. While tracing and capturing the complexity of dimensions to scale and place for encounters of laws and institutions in an international development context can be challenging, this Special Issue showcases a variety of methodologies and methods used by legal researchers to successfully tease apart and critically examine the significance of the glocal to the contours of that encounter, and its stakes for different communities (see especially Jean-Bouchard; Lander; Brabazon Citation2021; Airey Citation2022).

This is matched by the fifth and final vector of the kaleidoscope metaphor – the interaction between temporality and authority, or how different temporalities, temporal practices or regimes transform development and its governance effects. Whether in the conventional sense of histories (at local, global, or other levels, or from colonial, imperial, modern etc. perspectives.), or in how the processes and instruments of development and its governance have inescapable temporal dimensions, time is intrinsic to shaping the normative and constitutive aspects of development in myriad ways. Thus, contributors to this Special Issue draw attention to the implications for governance of the cyclical nature of international commodity price movements (Lander Citation2021); the time limitations inherent in DFIs accountability mechanisms (Jokubauskaite and Rossati Citation2021); the centrality of temporal articulations of pathways to change in models and theories of development and of rights, such as, for example, the temporal ordering of legal (before) and economic (after) causality (McHugh-Russell Citation2021), as well as perceptions of causality to the realisation of rights after the introduction of new legal instruments and institutions (Jean-Bouchard Citation2022); the rhythms to the performance of repetitive bureaucratic governance practices in which the periodisation of gathering, processing and reporting of data are key (Airey Citation2022); and the significance to contemporary legal distinctions between the sovereign (public) and the state (private) of their evolution from legal developments that occurred during a particular time in the colonial era (D'Souza Citation2022). Though these dimensions of the relationship between power and the temporal reflect an approach to the commodification of time already deemed essential to states operating within capitalist systems (Thompson Citation1967), they expand our understanding of its significance in a fluid governance environment such as the one enabled by development.

The kaleidoscope lens we use to frame our introduction to this Special Issue, and the analysis of the five vectors above, is not intended to capture all or deliberately exclude any of development's governance dimensions; we recognise the significance of other elements that are not foregrounded as distinct vectors in the framing proposed. Furthermore, as the level of analysis at scale or object/aspect of development under scrutiny shifts, the pattern to governance and its legal and juridical dimensions will change. As example, the potency of development's governance dimensions is significantly enhanced by elements such as its symbolic qualities, its relationship to history, and the significance to the experience of laws in development of lived, embodied identities such as race, class and gender and their combination. A more acute focus on any of these dimensions will significantly re-calibrate laws’ roles in the governance dimensions of development and demand deeper reflection on its implications. But for now, we proceed with a higher-level approach to each of the above five vectors, recognising the generative work that further imaginative engagement with the kaleidoscope metaphor by others, and along other lines of enquiry, could yield.

Law, legality, and infinite regress in the governance of development, or ‘turtles all the way down’

If the kaleidoscope is the conceptual lens that emerges from this collaborative initiative, then methodologically, several features to law emerge from this lens that are evident across the contributions included here. The concept of law animating the contributions is one that takes formal law seriously on its own merits yet expands and deepens the reach and relevance of laws and institutions in a development context far beyond their formalist features. The approach to law in these contributions is not linear, nor does it focus on the superficially identifiable ‘legal’. Law's presence and absence, whether immediate or remote, explicit, or implicit, are recognised as multi-dimensional, emerging within and through encounters, and connecting diverse sites, actors, contexts, locales, and times. What is key here is how these manifestations of law and legality connect and engage, and how these connections and engagements bend and refract power, identity, and status, especially of those who stand to gain and lose the most from development interventions. Recognition of the relational dimensions of the encounter between law and development emphasises more plural anchors to law and legality than a traditional focus on the state or international organisations alone may reveal. Through law's interplay with development, the governance potency of both is augmented. In this way, we characterise the law-development encounter via analogy with the principle of ‘infinite regress’ – reflected by the popular saying ‘turtles all the way down’ – not in a quest for some chicken–egg explanation of which-comes-first, or how each contributes to governance – but to capture their enmeshed and complex engagement.

Through each of the powerfully argued, diversely situated, and carefully traced articles in this Special Issue, it is our aspiration that the myriad legal, juridical, normative, and other dimensions to laws’ role in development will be heightened and better understood, and that these insights will serve as a stepping-stone for further critical engagement from scholarship in law and in development studies with the governance dimensions of the development project.

Acknowledgements

This Special Issue is the result of a research initiative ‘Law, Governance & Development – Critical & Heterodox Approaches’ involving several conversations between many participants that took place over 2018–2021. These included a workshop hosted at the Human Rights Research and Education Centre at the University of Ottawa in March 2018, with support from the Centre for International Governance Innovation (University of Waterloo) and the Irish Research Council. We thank these institutions for their support.

We wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and the contributors to this Special Issue for their insightful and helpful comments on this Introduction; the Editorial Board of the Canadian Journal of Development Studies for embracing this project, and its ever-helpful editorial staff for guidance and expertly shepherding it to a successful conclusion. Thanks also to Karen Paalman for her artistic design skills on the kaleidoscope image in this article.

Though COVID-19 intervened, interrupted and delayed completion of this project in many ways, we are deeply appreciative of the commitment of all participants involved in these conversations, and above all, to the contributors whose research is included in this Special Issue, for enthusiastically sharing with us skilful essays that are both thoughtful and engaging.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siobhán Airey

Siobhán Airey is Government of Ireland Research Fellow at the School of Law, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Her research examines law and legality in the international governance of sustainable development, including its international financing. Her current research examines the international governance of the financial system's response to the climate crisis. She has undertaken research in several countries.

Mark Toufayan

Mark Toufayan is Assistant Professor of Law at the Université du Québec en Outaouais. His research focuses on the history and theory of international law, human rights and humanitarianism, law and development, and contemporary legal and economic thought about regulation and governance. He has edited (with Emmanuelle Tourme-Jouannet and Hélène Ruiz Fabri) Droit international et nouvelles approches sur le tiers monde: entre répétition et renouveau/International Law and New Approaches to the Third World: Between Repetition and Renewal (Société de législation comparée, 2013).

Notes

1 We note the content and contours of assessments of ‘state of the field’ approaches to international development studies (IDS) in recent years in publications including special issues in leading journals on IDS such as ‘Critical Development Studies and the Study of Globalization(s): Intersections, Fusions and Divergences,’ (2020) 18 (8) Globalizations; an earlier ‘The State of Development Studies,’ (2016) 37 (1) Canadian Journal of Development Studies, as well as edited collections such as Beaudet, Haslam, and Schafer (Citation2021), earlier editions of Veltmeyer and Bowles (eds) (Citation2022), and Baud, Basile, Kontinen and von Itter (eds) (Citation2019), in which discussions of law are notably absent. We interpret the lack of references to law in contributions to these edited collections and subject index of these books as indicative of a deeper disciplinary aporia about law despite law and regulation being more or less key to all of the topics addressed therein on development theories, actors, issues and practices. By way of a ‘state of the field’ comparison in law and development, see De Feyter, Erdem Türkelli, and de Moerloose (Citation2021), which includes entries that substantively engage with topics in each of the IDS edited collections and journal issues, but where sustained engagements with the governance dimensions in development are equally lacking.

2 In a similar vein, Haskell and Rasulov (Citation2018) have argued that the recent shift to ‘political economy’ within international law as a means of overcoming the latter's blind spots towards its complicity in the structural injustices of modern capitalism remains too weak a basis for disciplinary remediation, given the epistemic volatility of the concept to anchor telic interdisciplinary engagement.

3 A liberal approach to law is based on a particular social vision where law as an instrument is primarily concerned with serving individual autonomy. It concentrates on the protection of individual rights including freedom of expression and self-realisation; economic mobility and the free movement of capital and resources; and the protection of private property. It privileges markets over other instruments as the central organising principle of society, and thus remains (in the main) wedded to a view of law that focuses on its purpose in promoting efficiency in social life through markets, over other values and purposes such as achieving substantive equality through participatory or communitarian means.

4 As Rittich (Citation2016, 823–824) has pointed out, historically, ‘as the problem of development has been transformed into a question of governance, the field of law and development has become more intertwined with a broader normative project around global governance’. Such a shift, however, has led to attention being drawn to questions of governance that are largely ‘depoliticised’, ‘focused primarily on the role of domestic legal rules, norms, and institutions in fostering economic growth and social, political, and cultural modernization’.

5 The approach taken here is not introductory or cartographic – it does not seek to provide either a complete map or an overview of the rich body of legal scholarship that has explored many facets of development at multiple levels of governance. For this, we direct readers to individual contributions to this Special Issue and their extensive bibliographies to source materials for knowledge of issues and debates specific to their areas of interest. Rather, this Introduction's goals are critical and reflexive.

6 See for example Sylvester (Citation1999), Strongman (Citation2014), and more generally Schuurman (Citation2009). The elements of the critical mode of enquiry elaborated by Schuurman are shared by other critical theorists in sister disciplines to development studies, e.g. Mittelman (Citation2004).

7 The idea of development as a project is held by many development theorists and lends to linear narratives of the evolution of development theory, especially since the articulation of the Truman Doctrine. See for example Parpart and Veltmeyer (Citation2004). On the nature of the development project, see McMichael (Citation2012).

8 An assumption Trubek and Santos use to anchor their depiction of what they refer to as ‘law and development doctrine’ as the product of intersecting spheres of law, institutional practice, and economics, where the institutional practices and policies of international development agencies are shaped by economic ideas (Trubek and Santos Citation2006, 4).

9 Here we mean beyond the focus on human rights and ‘rule of law’ debates that dominates much attention by development commentators on the role of law in development.

10 In doing so, we are not suggesting that it supersedes others, such as Trubek and Santos’, nor that it constitutes the next ‘moment’ or ‘consensus’ in law and development (Vandenhole Citation2019), but rather seek to interrupt the normative and instrumental imperatives that have long underpinned orthodox approaches to the field.

11 See for example the different approaches to the nature of the legal form in Özsu (Citation2019), compared to Bodansky (Citation2016), as well as in various entries (from a broadly defined Marxist perspective) curated on the insightful Legal Form blog: https://legalform.blog/.

12 Here, we resist the impulse of moving from analysis of these encounters to a totalising typology capturing the totality of their engagement or its ‘resolution’.

13 The nature of law, from an ‘internal’ and ‘external’ point of view, has long been a core debate in legal theory, legal philosophy (as example, expressed in the Fuller-Hart debate of 1958 and the writings it subsequently inspired), and re-emerges periodically at moments of disciplinary crisis and consolidation in different bodies of law, as exemplified more recently in debates on the nature of international law. For a helpful overview, see Özsu (Citation2019).

References

- Airey, Siobhán. 2022. “Rationality, Regularity and Rule – Juridical Governance of/by Official Development Assistance.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/02255189.2022.2026306.

- Alessandrini, Donatella. 2016. Value Making in International Economic Law and Regulation: Alternative Possibilities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Anantharajah, Kirsty. 2021. “Racial Formation, Coloniality, and Climate Finance Organisations: Implications for Emergent Data Projects in the Pacific.” Big Data & Society 8 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1177/20539517211027600.

- Bak McKenna, Miriam. 2021. “Remaking the Law of Encounter: Comparative International Law as Transformative Translation.” In The Politics of Translation in International Relations, edited by Maj Grasten, Zeynep Gulsah Capan, and Filipe dos Reis, 67–86. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Baud, Isa, Elisabetta Basile, Tiina Kontinen, and Susanne von Itter, eds. 2019. Building Development Studies for the New Millennium. Bonn: European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes.

- Beard, Jennifer L. 2007. The Political Economy of Desire: International Law, Development and the Nation State. Abingdon: Routledge-Cavendish.

- Beaudet, Pierre, Paul Haslam, and Jessica Schafer, eds. 2021. Introduction to International Development. Approaches, Actors and Issues. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bodansky, Daniel. 2016. “The Legal Character of the Paris Agreement.” Review of European Community, and International Environmental Law 25 (2): 142–150. doi:10.1111/reel.12154.

- Boer, Lianne J.M., and Sofia Stolk, eds. 2019. Backstage Practices of Transnational Law. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Brabazon, Honor. 2021. “Juridifying Agrarian Reform: The Role of Law in the Reconstitution of Neoliberalism in Bolivia.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/02255189.2021.1945551.

- Buchanan, Ruth, Stewart Motha, and Sundhya Pahuja. 2012. “Introduction.” In Reading Modern Law: Critical Methodologies and Sovereign Formations, edited by Ruth Buchanan, Stewart Motha, and Sundhya Pahuja, 1–14. Abingdon: Routledge.

- De Feyter, Koen, Gamze Erdem Türkelli, and Stéphanie de Moerloose, eds. 2021. Encyclopedia of Law and Development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Del Mar, Maksymilian. 2020. Artefacts of Legal Inquiry: The Value of Imagination in Adjudication. London: Bloomsbury/Hart.

- D’Souza, Radha. 2022. “A Radical Turn in International Law and Development? Corporations, Capitalist States and Imperial Governance.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/02255189.2022.2027232.

- Dubber, Markus D. 2014. “Critical Analysis of Law; Interdisciplinarity, Contextuality and the Future of Legal Studies.” Critical Analysis of Law 1: 1–4. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2385656.

- Eslava, Luis. 2015. Local Space, Global Life: The Everyday Operation of International Law and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fitzpatrick, Peter. 2001. Modernism and the Grounds of Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grear, Anna. 2015. “Deconstructing Anthropos: A Critical Legal Reflection on ‘Anthropocentric’ Law and Anthropocene ‘Humanity’.” Law and Critique 26: 225–249. doi:10.1007/s10978-015-9161-0.

- Guzzini, Stefano. 2012. “The Ambivalent Diffusion of Power in Global Governance.” In The Diffusion of Power in Global Governance – International Political Economy Meets Foucault, edited by Stefano Guzzini and Iver B. Neumann, 1–37. New York: Palgrave.

- Haskell, John D., and Akbar Rasulov. 2018. “International Law and the Turn to Political Economy.” Leiden Journal of International Law 31 (2): 243–250. doi:10.1017/S0922156518000092.

- Jean-Bouchard, Évelyne. 2022. “Vers un institutionnalisme féministe et anthropologique: expériences congolaises multi-scalaires des femmes, du développement et du droit.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/02255189.2021.2011164.

- Jokubauskaite, Giedre, and David Rossati. 2021. “A Tragedy of Juridification in International Development Finance.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/02255189.2021.1895090.

- Kennedy, David. 2013. “Law and Development Economics: Towards a New Alliance.” In Law and Economics with Chinese Characteristics: Institutions for Promoting Development in the 21st Century, edited by David Kennedy and Joseph E. Stiglitz, 19–70. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lander, Jennifer. 2021. “Shifting States: The Constitutional Risks of Extractive Development.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/02255189.2021.1906632.

- Loomba, Ania, and Ritty A. Lukose. 2012. South Asian Feminisms. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mbembé, J.-A., and Libby Meintjes. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/39984.

- McHugh-Russell, Liam. 2021. “Doing Business: Guidance, Legal Origins Theory, and the Politics of Governance by Knowledge.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies. doi:10.1080/02255189.2021.1971953.

- McMichael, Philip. 2012. Development and Social Change: A Global Perspective. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2007. “DELINKING. The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-coloniality.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 449–514. doi:10.1080/09502380601162647.

- Mittelman, James H. 2004. “What is Critical Globalization Studies?” International Studies Perspectives 5: 219–230.

- Nazneen, Sohela, Naomi Hossain, and Deepta Chopra. 2019. “Introduction: Contentious Women’s Empowerment in South Asia.” Contemporary South Asia 27 (4): 457–470. doi:10.1080/09584935.2019.1689922.

- Neajai Pailey, Robtel. 2020. “Decentering the ‘White Gaze’ of Development.” Development and Change 51 (3): 729–745. doi:10.1111/dech.12550.

- Orford, Anne. 2006. “Trade, Human Rights and the Economy of Sacrifice.” In International Law and its Others, edited by Anne Orford, 156–196. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Özsu, Umut. 2010. “The Question of Form: Methodological Notes on Dialectics and International Law.” Leiden Journal of International Law 23 (3): 687–707.

- Özsu, Umut. 2019. “Legal Form.” In Concepts for International Law, Contributions to Disciplinary Thought, edited by Jean d’Aspremont and Sahib Singh, 624–635. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781783474684.00045.

- Pahuja, Sundhya. 2007. “Rights as Regulation: The Integration of Development and Human Rights.” In The Intersection of Rights and Regulation: New Directions in Sociolegal Scholarship, edited by Bronwen Morgan, 167–191. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Pahuja, Sundhya. 2013. “Laws of Encounter: A Jurisdictional Account of International Law.” London Review of International Law 1 (1): 63–98. doi:10.1093/lril/lrt009.

- Parpart, Jane L., and Henry Veltmeyer. 2004. “The Development Project in Theory and Practice: A Review of its Shifting Dynamics.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 25 (1): 39–59. doi:10.1080/02255189.2004.9668959.

- Peet, Richard, and Elaine Hartwick. 2015. Theories of Development: Contentions, Arguments, Alternatives. 3rd ed. London: Guilford Press.

- Rapozo, Pedro. 2020. “The Necropolitics of Development: Socio-Environmental Conflicts and the Cartography of Violence Among Indigenous Peoples of the Triple Amazonian Border Brazil, Colombia and Peru.” In Perspectivas de desarrollo rural en América Latina, edited by Marcos Aurelio Saquet and Adilson Francelino Alves, 227–257. Lecce, Italy: Universitá del Salento.

- Riles, Annelise. 1994. “Representing In-Between: Law, Anthropology, and the Rhetoric of Interdisciplinarity.” University of Illinois Law Review 3: 597–650. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1086/.

- Riles, Annelise. 2006. “Anthropology, Human Rights, and Legal Knowledge: Culture in the Iron Cage.” American Anthropologist 108 (1): 52–65.

- Riles, Annelise. 2011. Collateral Knowledge: Legal Reasoning in the Global Financial Markets. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rittich, Kerry. 2016. “Theorizing International Law and Development.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Theory of International Law, edited by Anne Orford and Florian Hoffman, 820–843. Oxford University Press, Oxford Handbooks Online.

- Roudometof, Victor. 2016. “Theorizing Glocalization: Three Interpretations.” European Journal of Social Theory 19 (3): 391–408. doi:10.1177/1368431015605443.

- Santos, Alvaro. 2006. “The World Bank’s Uses of the ‘Rule of Law’: Promise in Economic Development.” In The New Law and Economic Development. A Critical Appraisal, edited by David M. Trubek and Alvaro Santos, 253–300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schuurman, Frans J. 2009. “Critical Development Theory: Moving out of the Twilight Zone.” Third World Quarterly 30 (5): 831–848. doi:10.1080/01436590902959024.

- Strongman, Luke. 2014. “Postcolonialism and International Development Studies: A Dialectical Exchange?” Third World Quarterly 35 (8): 1343–1354. doi:10.1080/01436597.2014.946248.

- Swyngedouw, Erik. 2004. “Globalisation or ‘Glocalisation’? Networks, Territories and Rescaling.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 17 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1080/0955757042000203632.

- Sylvester, Christine. 1999. “Development Studies and Postcolonial Studies: Disparate Tales of the ‘Third World’.” Third World Quarterly 20 (4): 703–721. doi:10.1080/01436599913514.

- Teubner, Gunther. 1989. “How the Law Thinks: Toward a Constructivist Epistemology of Law.” Law & Society Review 23 (5): 727–757. doi:10.2307/3053760.

- Thompson, E. P. 1967. “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism.” Past and Present 38: 56–97.

- Trubek, David M., and Alvaro Santos. 2006. “Introduction: The Third Moment in Law and Development Theory and the Emergence of a New Critical Practice.” In The New Law and Economic Development: A Critical Appraisal, edited by David M. Trubek and Alvaro Santos, 1–18. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Vandenhole, Wouter. 2019. “Towards a Fourth Moment in Law and Development?” Law and Development Review 12 (2): 265–283. doi:10.1515/ldr-2019-0013.

- Veltmeyer, Henry, and Paul Bowles. 2022. The Essential Guide to Critical Development Studies. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Zumbansen, Peer. 2014. “Knowledge in Development, Law and Regulation, or How are We to Distinguish Between the Economic and the Non-Economic?” In Critical Legal Perspectives on Global Governance: Liber Amicorum David M Trubek, edited by Gráinne de Búrca, Claire Kilpatrick, and Joanne Scott, 103–126. London: Bloomsbury/Hart.