ABSTRACT

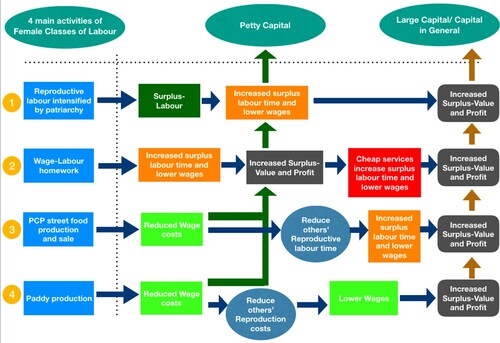

This article argues that patriarchy expands capitalist accumulation by increasing surplus labour-time, lowering production costs, and dividing and controlling workers. Consequently, patriarchy increases profits, manages intra-capitalist competition, and impedes labour’s capacity to organise. Analysing how it does so can inform counter-strategies. Based on fieldwork in two West Java villages, the article analyses four forms of patriarchal accumulation: (i) reproductive labour underpinned by the ideology of housewifeization; (ii) the gendered production of cheap foodgrains; (iii) the production of street-food that reduces reproduction time and costs; and (iv) the extension of labour-time through low-waged homework squeezed into the rhythms of reproductive labour.

RÉSUMÉ

Dans le présent article, nous soutenons que le patriarcat favorise l’accumulation capitaliste, en augmentant le surplus de temps de travail, en diminuant les coûts de production, et en divisant les travailleurs pour mieux les contrôler. En conséquence, le patriarcat accroît les profits, régule la compétition intra-capitaliste, et limite la capacité des travailleurs à s’organiser. C’est l’analyse de ce processus qui nous permet d’élaborer des contre-stratégies. Cet article se base sur des recherches sur le terrain, menées dans deux villages situés dans l’est de Java, pour analyser quatre formes d’accumulation patriarcale : (i) le travail reproductif sous-tendu par l’idéologie de housewifeization ; (ii) la production genrée de céréales à bas prix ; (iii) la production de street-food qui réduit le temps et le coût de production ; (iii) l’extension du temps de travail par le biais de travail à la maison peu rémunéré et intégré de force dans les rythmes de travail reproductif.

Introduction

Like gender and class, production and reproduction cannot be understood dichotomously. Capital accumulates through sites of production and social life in general at the expense of classes of labour, and especially the women among them. Despite some disagreement over how to conceptualise the relationship between reproductive and productive labour in the creation of surplus value (Mezzadri Citation2020), there is widespread agreement over the fact that both are essential to capitalist accumulation (Baglioni Citation2021; Bakker and Gill Citation2019; Bhattacharya Citation2017; Ferguson Citation2016; Mezzadri Citation2020; Rioux Citation2015). As capitalism moves through time and place it may appropriate reproductive labour wholesale, or attempt to reconcile the tensions that emerge between its relentless need for self-expansion and its need to shape social life for that end (Bakker and Gill Citation2019; Fraser Citation2017). Governments use a range of strategies to manage the reproduction-production nexus in ways that boost accumulation and regulate the flow of workers into sites of production – from violence and ideological conditioning to the expansion or contraction of public provisioning of reproductive labour (Federici Citation2004; Fraser Citation2017).

As well as coercive and ideological mechanisms, capital maximises its appropriation of surplus labour time by shaping divisions of labour. And while there is no space here to discuss why forms and intensities of patriarchy vary across time and place, it is worth noting that historical analyses of colonial appropriations of labour, and more recent analyses of the commodification of life and livelihood, both indicate the significance of divisions of labour (Boserup Citation1970, 77; Young Park and Maffii Citation2017; Stoler Citation1977, 75–77). In the case of Java, the distinct labour processes required for paddy production reduced the separation of men’s and women’s labour and seemingly contributed to a less extreme form of patriarchy than found in much of South Asia and significant parts of East Asia, the Middle East and Africa (Stoler Citation1977 and Wolf Citation1990 on Java; Boserup Citation1970 and Kandiyoti Citation1988 more generally). This article is concerned with the concrete ways in which productive and reproductive labour are intertwined (Mies Citation1982; see also Mezzadri Citation2020). Rather than a linear notion of the reproductive-productive nexus (understood as the former providing labour-power for the latter), it shows the multiple movements between the two spheres, which reflect the many ways in which capital in two West Java villages, in its more general and more specific forms, tries to maximise the appropriation of all forms of labour at the lowest possible cost through the patriarchy of accumulation.

This does not mean that patriarchy is not contested in multiple ways (e.g. Ong and Peletz Citation1995), nor that patriarchy is entirely subsumed within capitalism.Footnote1 The argument here is a more modest one: patriarchy and capitalism are co-constitutive, and capitalism uses patriarchy to expand accumulation by increasing surplus labour-time, lowering production costs, and dividing and controlling workers. It does so through the intricately related spheres of production and reproduction, and in material and ideological ways.

Terms like ‘variegated social reproduction’ and ‘reproduction regime’ help to locate the reproduction-production nexus within the spatially uneven world-historical dynamics of capitalism (Bakker and Gill Citation2019; Ferguson Citation2016, 46; Fraser Citation2017). These broader patterns are ‘the sum’ of the many concrete forms of patriarchal accumulation, and analysis of the latter is equally central to understanding how patriarchy and capitalism are co-constituted. This article locates the concrete forms of the patriarchy of accumulation in two West Java villages in their broader context of accumulation, and among capital-labour relations and intra-capitalist relations in Indonesia as a whole, and beyond that the world economy. It shows, contrary to Sanyal’s (Citation2007) separation of capitalist and non-capitalist spheres, that informal wage-labour and petty forms of self-employment are not ‘non-capitalist’, but central features of capitalism in ways that criss-cross the productive and reproductive spheres.

The article analyses how gender and class-based inequalities are (re)produced through four key forms of the patriarchy of accumulation that increase capital’s extraction of surplus value from classes of labour while managing capital-labour and intra-capitalist relations, and in ways that heighten extraction of surplus labour time from women relative to men: (i) homework that is squeezed into the rhythms of reproductive labour, extending surplus labour time and pushing down wages (along with the many forms of low-waged work through which classes of labour contribute to accumulation in general); (ii) petty commodity production and the production and sale of street-food that cheapens reproductive labour and heightens surplus labour time by reducing others’ reproductive labour time; (iii) the gendered production of staple food for rural households and society at large in ways that hold down the costs of reproduction and allow capital to reduce costs and increase competitiveness and profits; and (iv) elements of the ideology of housewifeization,Footnote2 which normalise patriarchy and encourage the ‘primary’ reproductive labour that nurtures labour-power – the primary basis, alongside natural resources, of capitalist accumulation. Each of these four elements is briefly outlined after the methods section before being discussed in more detail.

Capital exploits labour by appropriating surplus labour time from the production process and by appropriating reproductive labour. Its interests are best served by maximising surplus labour time and reproductive labour time, but if the demands become too great, as they did for many working-class women in Victorian London who struggled to combine long factory hours with raising children, then both forms of work can be undermined (Fraser Citation2017). In other words, the overall working day has to be stretched, but not to breaking point. Regardless of the degree to which surplus labour and reproductive labour are ‘pumped out’ of women, to varying degreesFootnote3 the divisive profit-maximising woman-subordinating co-constitution of patriarchy and capitalism renders women’s wages ‘doubly low’ – in relation to the spheres of production and reproduction – and extends and intensifies her working day (Mies Citation1986).

Through its analysis of the production-reproduction nexus in rural West Java this article shows that patriarchy in its concrete and ideological forms, and the ways in which capital divides labour along gendered lines, are central to capitalist accumulation and to its control over labour. While the two spheres of human labour – production and reproduction – have to be distinguished for the purposes of analysis, they must be understood as ontologically unified if capitalist dynamics are to be more fully revealed.

Methods, the social structure of the fieldwork villages, and patterns of wage-labour and self-employment

Fieldwork was carried out in two villages in West Java – one close to the city of Tasik Malaya, and one a little further away, beyond easy commutable distance. Eighty-eight per cent of households across the two villages belonged to classes of labour (see Bernstein Citation2006) engaged in multiple forms of informal low waged-labour and low-income petty commodity production (PCP).Footnote4 Of these around two thirds were primarily dependent on wage-labour, and a third on petty self-employment.Footnote5

Relatively few exploitative relations were internal to either village. Only 6.4 per cent of households were petty capitalist, while 5.6 per cent were government employees or white-collar workers with small side-businesses. Two-thirds of the land in the two kampungs was owned by city-based absentee landowners with historical kinship ties to the area. The primary mechanisms of exploitation centred on their relations with sharecroppers and other agricultural labourers, as well as on the urban-based petty capitalists who outsource work to female homeworkers and employ younger workers in peri-urban factories.

In all, around ninety per cent of non-agricultural wage labour was for small businesses, and ninety per cent of wages were at rates below the nationally mandated minimums (see ) – something driven by the competitive dynamics of small-scale capitalism, and its place in capitalism in general, and facilitated by the long working hours of ‘pluri-active’ households. The ten per cent of households that accessed higher-waged work had noticeably higher living standards, and worked shorter days in fewer jobs.

Table 1. Hourly wage-rates in kampungs 1 and 2.

The social structure, then, was relatively flat with nearly 90 per cent belonging to classes of labour, and exploitative relations being primarily external to the villages. Nonetheless there were socio-economic and socio-political differences among classes of labour (see and below for detailed comparison of particular households).

All 233 households in the two kampungs (a kampung is a hamlet and villages on Java are made up multiple hamlets) were surveyed and 49 were interviewed. Around one third of these were interviewed twice, and half of those on multiple occasions as key informants. Most interviews were conducted with women alone (with a local female co-researcher), some with men alone, sometimes one and then the other and occasionally both together. Interviews were conducted in August-September and November-December 2019. A number of villages had been visited in late 2018 to determine field-sites, and the co-researcher surveyed the villages in early 2019.

There were notable differences between the two kampungs. Kampung 1, located a few kilometres from the city’s edge, was predominantly non-agrarian. Its main economic activities were the production and trade of street-food and low-paid female homework, which was seamlessly interwoven with reproductive work. Other activities were, in order, migrant street-vending, agricultural labour, farming, work in small local factories, and construction. Kampung 2, which was beyond easy commutable distance of the city, was still predominantly agrarian, and agricultural wage-labour was its most common form of work. It had a little more construction work than Kampung 1, but considerably less street-food production and scarcely any homework as yet. There were similar levels of migration in both Kampungs (encompassing around a quarter of households, but mostly to distant factories from Kampung 2, and as streetfood-vendors from Kampung 1) (see Pattenden and Wastuti, Citationforthcoming). Although all four elements of the patriarchy of accumulation were present in both fieldwork sites, the mix of elements varied and so the ensuing discussion moves its focus between the two kampungs. The first two elements (homework and food production/trade) focus mostly on Kampung 1, while the third element (paddy production) focuses mostly on Kampung 2.

The patriarchy of accumulation

An outline of the four elements

This paper focuses on women’s three main economic activities across the fieldwork villages, which were homework (a form of wage-labour), street-food production and sales (a form of PCP), and paddy (rice) cultivation (mostly as wage-labour but also as PCP). Less common economic activities, including child-minding (paid reproductive labour) and factory work (primarily by younger women) are not systematically considered in this article due to space constraints. Other papers focus on migration (Pattenden and Wastuti, Citationforthcoming) and on the substantial literature on agrarian change in Indonesia.Footnote6

Women’s homework – packing krupuk (cassava chips) and making toys from balloons – was the most common form of wage-labour in Kampung 1, taking place in over one third of its households. Homework has to be understood in relation to reproductive labour, labouring class reproduction as a whole, and capitalist accumulation in general. Homework was one of a number of forms of wage-labour and PCP that members of classes of labour did to make ends meet. Classes of labour subsidised petty capitalists by extending their working days and multiplying their economic activities to make up for the low wages and incomes of each, allowing employers to hold wages down (lower costs) and maximise surplus labour time.

Homework was particularly effective as a means of maximising surplus labour-time as it allowed petty capital to feed wage-labour time into the interstices of reproductive labour. Homeworkers were mostly mothers with high reproductive labour burdens who threaded snack-packing into the gaps between childcare and other tasks. The short-lived repetitive nature of the work lent itself to a stop-start labour process. The low hourly wage (around $0.20 per hour, less than a quarter of government-stipulated minimums; see ) allowed small capitalist businesses to stay afloat in a crowded marketplace.

These exploitative relations have to be located in the context of the broader economy. Not only were pluri-active labouring class households, and in particular the women among them, making it possible for petty capitalists to stay afloat by lowering wage costs and increasing the availability of wage-labour, but by doing so they were subsidising capital as a whole by providing cheap services and commodities that lowered reproduction costs across society and enabled capital-in-general to lower costs and increase profits.

This last point becomes clearer when we expand the discussion into the second activity of labouring class women in the two fieldwork villages – the production and sale of street-food. Street-food, mostly produced in the sleeping hours before dawn, is cheap and reduces the reproductive labour time of others who are freed up to work longer hours – both other members of the labouring class and middle-class city dwellers who tend to work for government or for larger businesses. And so low-income forms of PCP increase the surplus labour time available to capital-in-general and reduce the wage-bill – something that ultimately increases Indonesia’s competitiveness in the world economy. The provision of cheap food-grains has a similar impact with the low wages/incomes of paddy cultivators lowering society’s reproduction costs and, again, allowing capital to reduce costs and boost competitiveness and profits.

Reproductive labour provides labour-power for capital, and when it produces a surplus of labour-power, it pushes down wages and weakens labour politically, making it more pliant and more likely to intensify work and lengthen working hours. In other words a surplus of labour-power does not only put downwards pressure on wages in a direct sense, but also indirectly by increasing surplus labour time.

Reproductive labour and labour-power have often been intensified through the propagation of patriarchal ideology (e.g. Federici Citation2004; Kalb Citation2004). Indonesia is no exception (Robinson Citation2009), and elements of this were identified in the fieldwork villages (see below). Each of the four inter-related elements of the patriarchy of accumulation will now be elaborated. The prominence of each varies between labouring class households, villages and areas. And while ideology is included here as a fourth element, it is different to the other three, all of which it helps to shape.

Element no. 1: homework and accumulation-in-general

Female homework maximises surplus labour time by weaving wage-labour into the rhythms of reproductive work.Footnote7 No time is lost travelling to workplaces and every lull in reproductive labour can be filled with bursts of piece-rated wage-labour. In other words, capital squeezes surplus labour time from the gaps between reproductive labour, and for those with younger children and infants those gaps are often little more than moments. And when the reproductive labour time of particular homeworkers increases – when a child is unwell for example – they can sub-contract part of their quota to neighbours. Production within these decentralised factories, then, is not constrained by the four walls of particular houses, but can seep out into nearby homes and appropriate pauses in work throughout the community. And, as noted, because tasks tend to be repetitive and brief, a stop-start working routine does not reduce productivity. It may even increase it as the tedium is punctuated.

Unlike factory labour overtly disciplined by surveillant managers seeking to intensify labour time and minimise any loss of surplus labour time during the working day, homeworkers are (‘self’-)disciplined by the compulsion to maximise surplus labour time across multiple low-paid and unpaid activities so that their household’s basic needs can be met. Petty capital maximises its extraction of others’ time by combining this compulsion, driven by the widespread prevalence of low wages and the competitiveness of PCP and petty capitalism as a whole, with the piece-rated payment mechanism that removes the need for supervision. The piece-rate wage-worker is disciplined by the habit of feeding wage-work into less busy moments and periods, and hitting daily targets. This does come with elements of autonomy (Carswell and De Neve Citation2013), but these are more ‘perceived’ than ‘actual’ given the broader capitalist and patriarchal dynamic shaping these gendered forms of exploitation.

If the number of homeworkers in any given village grows to the point where production targets are no longer reliably reached, then business owners push into villages further from the city. When fieldwork was conducted close to the city in Kampung 1 in late 2019, the number of homeworkers was set to exceed fifty per cent of households. Much more than that and growth would spill up the valley. Meanwhile in Kampung 2, twenty kilometres to the west and further from the city, homework was just beginning.

Homework, which extends working days, is part of a broader lengthening of surplus labour-time and a cheapening of labour costs that increase surplus-value extraction in general. Paid at around $0.20 per hour (less than a quarter of government-stipulated minimum wages), homework is one of the multiple forms of low-waged labour and PCP that classes of labour are compelled to do to make ends meet. Through a process of cross-subsidisation, this pluri-activityFootnote8 allows each type of work to be low-paid. And while the direct beneficiaries are the small capitalist enterprises operating in and around the fieldwork kampungs, capital-in-general benefits from the low wages and low costs that allow Indonesia’s mass of small businesses to provide cheap services. Cheap services – be it snacks, food, childcare, elder care, construction of house extensions, plumbing etc. – allow capital-in-general to pay low wages, including those of white-collar workers whose reproduction costs and reproductive labour time are both reduced (see ).

This latter point brings into focus the reproduction-production nexus in ways that will be elaborated on in the next section, but it should be underlined that low homework wages reflect a broader pattern of holding down wages and boosting capitalist profit across Indonesian society, and beyond it. It also helps to explain why so many small businesses survive within the Indonesian economy. The very structure of the economy is built on classes of labour’s long working days, low wages and low-paid PCP. Before elaborating on this point, it is worth outlining some examples of women’s working days and their frequent movements between wage-labour, PCP and reproductive labour.

Most of those involved in homework – whether as krupuk-packers or street-food makers – get up around 3.30am. Novi gets up even earlier because the reproductive labour burden of caring for an infant is more extensive than caring for a husband and older children, but also because a significant part of her husband’s wage is lost through helping his mother make interest payments to the moneylender she has been in debt to perpetually for nine years. Novi, whose social networks are restricted because she lives matrilocally (relatively unusual in this region) rarely leaves the backstreet that she lives on. She squeezes ten hours of tedious wage-work into her 16-hour working day, sealing 2000 plastic bags with the flame of an oil-lamp, at the rate of one every 20 seconds. Her daily wage brings her an income of 20,000 IDR ($1.45). And within her other six hours of work she washes her husband’s clothes and prepares the meals that propel him through a 14-hour working day in the factory – the same factory that produces the krupuk that Novi packs. Her wages are a little over a third of his (see ).

Then there is Eli. She does two types of homework – krupuk-packing and balloon toy-making. Her husband has a morning job collecting rubbish from the market on the edge of town. Afterwards he spends three hours a day feeding the goats that they obtained by looking after others’ goats (a kind of goat ‘sharecropping’). They also sell chickens and marmots, and cultivate 0.07 hectares (50 bata)Footnote9 of Tanah BengkokFootnote10 exclusively with their own labour, which feeds the family for six months.

Eli gets up at 3.30am and fits nine hours of balloon toy-making into her day, as well as some krupuk-packing. On the days when she does both, she subcontracts parts of the process out to neighbours. She earns 48,000 IDR ($3.49) for nine hours of toy-making, and 15,000 IDR ($1.09) for five hours spent sealing 1000 small krupuk packets. Interestingly she says that she does not need to work as much as she does – she and her husband make 100,000 ($7.27) per day on average – more than is required for everyday needs (excluding higher education costs, spikes in health expenditure and weddings). She says that she is ‘used to working’. It seems that the ease with which homework fits into a day of housework and childcare normalises long working days in ways that would not be the case for those who work outside of their homes. Eli was always working on the many occasions that we passed her house.

Eli, like Aldora (see below), is better-off than Novi. Novi’s house is smaller, her income lower and as a young mother from a distant village whose husband is usually at a factory, she is socially isolated and has little autonomy from her mother-in-law. Eli, in contrast, is prominent within both her family and her community, and has social links to village leaders. And so while, as stated above, most households in the two fieldwork villages occupy similar socio-economic positions, there are nonetheless significant variations. Both Eli and Novi are homeworkers. Both do the same krupuk-packing work, but Eli also does higher-paid toy-making, raises animals and rents a small piece of land. And while their reproductive labour burdens are similar, there are differences – the younger woman has the more insistent work of caring for an infant, the older one has a number of children and a greater weight of work overall, but also longer periods of respite and a husband who works shorter hours and sometimes helps out.

Homework wages were the lowest identified in Kampung 1, and subject to an estimated 20 per cent cut by two intermediaries (the kampung coordinator, herself a packer, and the delivery man). The more than two and a half times disparity with men’s wages in the krupuk factories comfortably exceeded the gendered discrepancy in agricultural wages (see ). In part this was because homework is individualised and relatively invisible, and most of those involved self-identified as housewives in the survey (see also Mies Citation1982). But perhaps more than anything the low wages were due to the way that homework slipped seamlessly in with women’s reproductive work. In a broader sense, then, the low wages reflect patriarchal norms.

Element no. 2: petty commodity production, reproductive labour and capital accumulation

While the previous section showed how homework contributes not only to the accumulation of local capitalists, but to capital-in-general (total social capital) when seen as part of informal low-waged work in general, this section focuses on home PCP, and in so doing further elaborates on the reproduction-production nexus. Labouring class women in the kampungs make and sell cheap street-food (gorengan, cilok, baso and the like).Footnote11 It is sold in the village, at school-gates, and also finds its way to the suburbs of nearby Tasik city, increasing the availability of surplus labour-time in society as a whole by reducing customers’ reproductive labour time.

The wage-workers who buy the food have more time to work, as do the middle class customers working for the government or as white-collar workers for larger capital. Cheap street-food reduces reproductive costs and time, freeing up workers for longer hours and making it easier for them to accept low wages.

Those producing street-food alongside homework and other forms of wage-labour and PCP, as well as doing almost all the reproductive work in their households, are shaping others’ productive and reproductive spheres as well as their own. They transfer reproductive labour time in ways that are refracted by class as well as gender relations. The leisure time of men is lengthened while the reproductive labour time of the better-off is shortened by extending the working day of poorer women. And it is even longer in those households where the husband returns less of his income to the family pool.

Aldora is a case in point. She does over seven hours of wage-work, and over four hours of petty commodity production every day as well as all of the housework. Her long working hours support her daughter’s higher education. Education, part of the intergenerational rather than daily dimensions of social reproduction, is also something where the burden falls disproportionately on women in the fieldwork villages.

Aldora prepares three different types of street-food in the hours before dawn, during the afternoon and in the evening before she sleeps. After praying and preparing breakfast she packs krupuk until midday prayers. After lunch she does two and a half hours of low-waged work reading children the Koran at a crèche – contributing in another way to increasing surplus labour time by extending the school day so that parents can stay at work for longer. After the crèche work, there are a series of moves between krupuk-packing, housework and street-food preparation before the working day ends at 10pm. Five hours of krupuk-packing are squeezed in overall, and, like Eli, she sometimes sub-contracts to neighbours on days when reproductive labour burdens are greater, spilling surplus labour time out into cracks and crevices of potential surplus labour time elsewhere in the neighbourhood. Capital appropriates surplus-value as well as time. And amidst the jumble of ‘reproductive’ and ‘productive’ labour time, there is a transfer of reproductive labour from the working class to the middle class (who buy but do not make and sell), as well as from women to men (see also Wolf Citation1990, 98).

There is one further link between the spheres of reproduction and production, which brings into the focus the appropriations of petty capitalists within the kampungs. Poorer women who are unable to make ends meet through multiple forms of part-time low-waged work sometimes turn to better-off women who sell consumer goods on credit – a widespread system known as kiridit. Repayment by instalment conceals high mark-ups of up to 100 per cent, which are in effect usurious interest rates conveniently hidden to comply with Islamic norms. The kiridit traders circulate regularly through the village, offering fresh sales while taking payments.

Returning to the paper’s starting point: the reproduction-production nexus cannot be understood in linear terms as the movement from reproductive labour to the labour process and on to surplus value extraction and distribution. Instead reproductive labour is better understood as seeping at various points into surplus labour time and the extraction and distribution of surplus value. And so reproductive labour not only underpins the labour process in the most obvious sense of providing the means of labour-power, it criss-crosses the broader process of exploitation and fuels the dynamics of accumulation as they work their way through women’s social and working lives. This is the patriarchy of accumulation, and it shows that the distinction between reproductive and productive labour is analytical rather than real.

Homework and PCP in their broader context

In her finely-grained study of rural industrialisation in a central Java village Wolf (Citation1990) underlines how capital appropriates surplus labour from four types of paid and unpaid reproductive and productive labour. Women in villages that had sold land to the factories, provided food and services to incoming migrant workers – petty forms of self-employment that helped to keep wages down by subsidising the migrant factory workers’ reproduction costs, and increased surplus labour time by reducing reproductive labour time. In effect capital had found a way to divide productive and reproductive labour between local and migrant women. The capitalist, Wolf pointed out, had appropriated four times: wage-labour from the worker, daily reproductive wage-labour from the locals, the latter’s own reproductive labour, and the reproductive labour of those left behind in the migrants’ households. The capitalist also appropriated natural resources – a means of production and a source of profit in two ways (through speculation and production), but also a means of squeezing reproductive wage-labour out of those whose access to land had been diminished. There are parallels in this article’s fieldwork villages: declining access to land due to city landowners, population growth and processes of socio-economic differentiation all pushing growing numbers of women into forms of PCP that cut others’ reproductive labour – mostly that of city dwellers. The result is the same: cheap time-saving reproductive commodities allow for longer hours to be worked and lower wages to be paid.

Wolf’s analysis touches on all three aspects of Mezzadri’s (Citation2020) three-way typology of how reproductive labour contributes to capital’s extraction of surplus value: the more temporarily and spatially extended forms of daily and inter-generational reproductive labour in migrants’ home villages through which older workers take up a greater share of reproductive work and younger, faster workers are released into wage-work; the more spatially concentrated provision of daily and intergenerational reproductive labour in and around sites of production (in dormitories, hamlets etc.) which are also marked by generational divisions of labour; and wage-labour in the home where the spaces between productive and reproductive labour are blurred. All three are present in this article’s fieldwork villages and two have been discussed in the previous sections. Rather than Mezzadri’s characterisation of the reproduction-production nexus across space, the focus here has been on the reproduction-production nexus within particular places and their relations to society as a whole.

In one sense, the kampungs (hamlets) discussed above can be added to the list of dormitory regimes (Burawoy Citation1985), which include encampments of construction workers on SEZs, solitary huts on smaller construction sites, and shared dormitories in factory compounds. Within hamlets like the two discussed here, women’s reproductive labour can be intensified alongside wage-work, and working days can be easily extended because production is located within sites of reproduction. And not only can ‘overtime’ be maximised within each house (by keeping down wages and compelling longer hours, and in an environment that is less directly coercive, and so more conducive to self-disciplining), but also by allowing wage-work to spill over into neighbours’ houses.

Disciplining is also ideological. Where Burawoy (Citation1985) alluded to the indoctrination of sobriety and discipline by dog-collared preachers in chapels constructed beside Victorian mills, here in West Java women cast themselves as housewives and recall the culinary arts instilled in their mothers by village-level government institutions that exhorted women to compete with each other to be better cooks, better makers and repairers of clothes, and better nurturers of tomorrow’s workers – a point that is returned to below.

Element no. 3: fieldwork

Paddy cultivation was the third main economic activity of labouring class women, and especially the middle-aged among them, and a key aspect of labouring class pluri-activity. By both providing a significant share of household grain needs inside the kampung and by supplying cheap rice to the broader population, paddy cultivation plays a key role in reducing the reproductive costs of the kampungs and society as a whole. This helps capital to hold down wages and increase surplus value and profit. At the time of fieldwork consumers paid 10,000 IDR ($0.65) per kilo of rice – around a third of women’s agricultural wages and around one eighth of legally stipulated minimum wages.

A handful of women rent in land on fixed in-kind rents in Kampung 1, and one or two (far fewer than men) work as sharecroppers. Sharecropping is understood here as a form of disguised wage-labour through which risk and management responsibilities are offloaded by capitalist landowners to sharecroppers whose labour-power is tied to particular fields for the duration of each season. Most women, though, are straightforward wage-labourers, whose collective share of the value of the paddy they produce is significantly less than the landowners who are mostly urban-based capitalists with historical links to the area, and less than a chain of four traders who supply urban consumers (see Pattenden and Wastuti Citation2021, Table 5 for details).

So agricultural labourers are exploited by outside capitalists, but the division of labour within cultivating households shows how women’s (re)productive labour is appropriated within households as well as between them, and between labour and capital more broadly. Paddy cultivation entails a gendering of the reproduction-production nexus and a gendered labour process that is located within a gendering of social space. Women transplant paddy, weed it, and harvest it. Men harrow, hoe, spread fertiliser, and tend to take part in the harvest. Male labour is more individualised, more stretched over time, more given to roaming and movement – not least in their role as guardians of water levels, and maintainers of bunds. If you drop by a house of agricultural labourers/sharecroppers, the women of the house are much more likely to be at home, even if are they are not looking after children. Men have often ‘gone to the sawah’ (paddy fields). Women’s work is temporally and spatially more bounded. It is also more constant, less social in an inter-household sense, but more social in an intra-household sense.

Similar physical geographies of work in general reflect the same gendering of social space. Access to non-agricultural work and to commuting and migration is often gendered, and not just in Indonesia (e.g. Da Corta and Venkateshwarlu Citation1999). Unmarried women in the fieldwork villages occasionally migrate alone for factory work, but seemingly only ever where there is a family connection in the destination area. Solo migration is by and large the preserve of younger men, or sometimes couples or families. Commuting is similarly gendered, with women commuting less and those with children hardly doing so at all. Social space is gendered beyond the village as well as within it, and this relates to the gendered distribution of reproductive labour as well as to patriarchal norms about social interactions. Female social space is more oriented around home and family. They shoulder the bulk of reproductive labour, and their role in the production of paddy and rice relates to that. They dry the paddy, and then they cook the rice and feed the family.

Female labour in agriculture is almost always carried out collectively, it is more regulated, more closely supervised, more time-bound, and less spatially as well as temporally expansive. Women plant together and weed together but during the harvest usually pair up with male relatives, creating divisions among workers at the key moment of value distribution between capital and labour. Women move between the house and the field with much greater predictability. And after the harvest they must stay at home for around half a week waiting for the paddy, their wages in kind, to dry. If their vigilance wanes, chickens will peck their wages away, or the wind will blow them away. At night mice might nibble them away. Drying paddy is not arduous, but it is nagging and persistent. And it takes up close to one tenth of a woman’s working life.

Ebong, an agricultural labour since the late 1970s when she was 12, underlines the time-bound nature of her working life by commenting that she waits every working day (around half of all her days) for the Muezzin to call the village for lunchtime prayers, as that is the moment when her working day ends. In her 50s now, she finds the work increasingly arduous, but she has a granddaughter to feed and other family members do little to help.

Harvest work is the hardest, especially when the sharecropper allocates part of the field that is further away from the place where the paddy is to be divided. If the sharecropper is a relative she may get a position that involves shorter carries. And when she works for her brother she gets a larger share. If she works for those more distanced from her family or her street, she gets a smaller share (Stoler Citation1977). Harvest shares, the most important source of income for agricultural labourers, are distributed through kinship and social ties as well as through exploitative class relations.

Women’s role in paddy cultivation, then, is not only gendered in relation to society as a whole, but also with regards to the relations among those cultivating paddy. Women agricultural labourers were mostly paid cash wages for transplantation and weeding work (with all but the poorest women preferring lunch to be provided by the landowner, and a lower wage, to avoid having to wake earlier to prepare their own lunch). But most of their wages were paid in kind after harvesting the paddy. When women transplant or weed on land sharecropped by her husband, they will not generally be paid. Instead she and her husband take a greater share at harvest time, some of which is sold and some transferred to her care for drying, storing and cooking. The husband as the sharecropper is more likely to control the money from the paddy that is sold. Poorer male sharecroppers earn an amount that is equivalent to female wages unless they ‘appropriate’ their wife’s wage. All are paid in the end, but in-kind and via additional labour and the family hearth. Neither the distribution of work or of value is equal. These patterns of work and distribution of value can also encompass other close female relatives and neighbours. And all this in a social setting where patriarchy is less oppressive than in much of, say, south Asia (Kandiyoti Citation1988; Stoler Citation1977). Residence is usually matrilocal, inheritance is bilateral rather than patrilineal, and land acquired during a marriage is owned by both as gono-gini land.

It is worth noting also the slight variations between the two kampungs: paddy cultivation in the kampung further from urban labour markets was slightly more gendered. Here the bulk of sharecropping responsibilities lay with men while in Kampung 1, closer to the city, women were as likely as men to rent paddy land – something that probably related to men’s greater access to non-agricultural labour markets more than to any clear-cut difference in gender relations. And a smaller share of paddy produced in Kampung 1 was sold, which could make its cultivation of less interest to men than women.

Element no. 4: ideology

As noted above, this fourth element is somewhat different to the other three because it is common to each of them, and primes the appropriation of reproductive labour. When survey work for this paper started, many women identified themselves as housewives (see also Mies Citation1982), even though in almost all cases they were involved in various forms of wage-labour and PCP, as well as shouldering the bulk of reproductive labour. The latter is ideologically devalued, of course, and de-linked from its broader role in the capitalist economy.

Each of the previous sections speaks to aspects of the patriarchy of accumulation, which is rooted in the unequal distribution of labour and value across the spheres of production and reproduction. Women do the bulk of reproductive labour that provides the labour-power through which capital accumulates. And women are systematically underpaid for equivalent work, which cheapens production and increases the scale and speed of capital accumulation. These two basic elements of the patriarchy of accumulation are, as Federici (Citation2004) has reminded us, linked to one another as women’s association with a ‘distinct’ reproductive domain is used to justify women’s systematic underpayment as wage labourers. Divisions of reproductive and productive labour, as noted in the introduction, are co-constituted with forms and degrees of patriarchy.

The systematic underpayment of women also contributes to the patriarchy of accumulation in a less direct sense – by dividing workers. Uneven wage levels create schisms between male and female labourers. And capitalists have used patriarchal ideology to co-opt men (Kalb Citation2004), and even, at times, to break up women’s collective action (see Koo Citation2001). Patriarchal ideology is closely related to ideological support for the family unit, which has been supported in practical ways, as well as discursively. In the words of Sue Ferguson (Citation2016, 50–51),

capital and the state have used social welfare practices, tax breaks and ideological signifiers to champion the ‘privatised household’ as the primary foundation of social reproduction due to its cost-saving efficiencies – all part of the ‘ways in which a capitalist totality inflects our institutions, interactions and relations’.

And so the ideology of the family as a gendered unit of social reproduction, as a reproductive labour form writ large as a reproductive labour regime, has found its way into the dynamics of patriarchal accumulation in different ways. So too in Indonesia. In the 1970s and 1980s ‘housewifiesation’ was institutionalised by Indonesia’s New Order regime in its promotion of ‘domesticated femininity’ and a ‘normative vision of women’s primary role as wife and mother’ (Robinson Citation2009, 5). Patriarchal ideological conditioning in relation to the household was linked to broader subservience to an oppressive masculinised authoritarian regime. As Robinson has put it (Citation2009, 5),

the presumed natural sexual hierarchy of the family with a core of patriarchal authority provided the ideological rationale for the Suharto regime. A violent and militaristic form of hegemonic masculinity was linked to the exercise of power in general. The naturalized authority of the father normalized the authoritarian power of the state.

Patriarchy was legally enshrined by the New Order regime as well as being inculcated ideologically. According to Article 31 of the Marriage Law of 1974, the husband is the head of the family and the wife is the mother of the family (Wolf Citation1990, 66). Azas Kekeluargaan, or the ‘family foundation of the state’ (Robinson Citation2009, 68), was a primary pillar of New Order ideology, and imposed through localised PKK practices. The PKK cast women as dutiful housewives, organised quizzes about how to be a good wife and mother, and, in one case, exhorted women to make Black Forest Gateaux with canned cherries and aerosol cream (Robinson Citation2009, 72, 76; see also Blackwood Citation2008, 32–33).

Both Permuda Pancasila and the PKK had left a strong imprint in the fieldwork villages. In Kampung 2, the wife of a civil servant (and daughter of a family that had, for a time, set up a small garment factory in the city before returning home in the 1960s to protect their land from the risk of redistribution) had led the local PKK organisation. She organised cookery competitions, sewing training, and women’s savings groups – all part of the seemingly benign propagation of propaganda about women’s responsibilities to her family, to housework, and the production of children. Better-off women, more time-rich, had understandably been more active. Her daughter was now involved in related activities, but these were more administrative than ideological. Interest had waned over time, and the PKK, now under the leadership of the Village Head’s wife, was a shell of its former self.

Partly this relates to the state’s changing reproductive regime – no longer so focused on championing totemic symbols of women’s reproductive labour, but still championing women’s domestic role, her supply of future labour power and contribution of her own labour power to accumulation in the present. The ideology of housewifeization remains strongly etched onto the social consciousness, even if exhortations of fetishised femininity are now less widespread.

And in Kampung 2, the remnants of the Permuda Pancasila maintained a presence in a more concrete way – a low-level state official proudly stating his membership of the organisation in a manner befitting its machismo. He allegedly performed informal minor tasks for capitalists, had links to premens, and occasionally expounded ideologies of masculine order. Both activists and ideology have a lesser presence than in the heyday of the authoritarian New Order regime (1965-1998), but their lingering presence recalls the impact they had on the older generation and may deter the younger one from resisting too.

The most notable aspects of civil society in the kampungs centred on religion, and clustered around the micro-level administrative divisions knows as ‘RTs’ or ‘Rohun Tetangga’ meaning ‘neighbours getting on’ – a term with its origins in 1943 in Imperial Japan’s wartime surveillance systems. Its primary initial function had been as a neighbourhood watch group designed to keep an eye on outsiders and report on any who stayed overnight. Today each RT has a ‘RT’ – the lowest level state official who is responsible for circulating information from the government and for mediating disputes. A small trickle of funds flows to them and through them, and RTs’ wives are sometimes involved in delivering elements of infant or maternal healthcare. Mosques serve social as well as religious functions, and as well as house construction and minor infrastructure works, a RT’s reputation seemed to hang on his support for the mosque. Kampung 1 will soon have its fourth mosque – one for every thirty houses.

What of counter-currents in everyday consciousness? Mies noted (Citation1982, 68) that solidarity among homeworkers is less likely than among agricultural labourers because they do not conceive of themselves as workers. But the competitiveness of the paddy harvest mitigates against agricultural workers developing a sense of collective interests. The women’s working gang is effectively carved up into husband and wife pairings vying for a greater share of the harvest pot, which will then be channelled through the household via unequal distributions of value and labour.

There are elements of cooperation in the sharing of knowledge about toy-making or the distribution of homework. And groups of women sometimes gathered on doorsteps, clustered around the small oil-lamps used to seal krupuk packs. But there are also elements of competition – one gorengan maker lamenting the greater success of the more fashionable snacks prepared and sold by her upwardly mobile neighbour.

The divisions of labour by generation point to a degree of change. Younger women commuted more, women with children home-worked more, and older women ‘fieldworked’ more. The former’s enlarged social space can galvanise elements of change within intra-household socio-political dynamics, and break down norms to a degree before, in most cases, women slide into sedentary gendered domesticity. It is hard to imagine significant change without the state pushing more strongly for equivalence of female wages or challenging violence against women – thereby giving women clear targets for mobilisations in larger factories and among more formal types of work, which might produce ripples in the more fragmented informal forms of wage-labour and PCP that occupied the majority of the lives of the women in the fieldwork villages. Such moves from the state, though, would undermine its bid to make Indonesia competitive in the global economy. So, while experiences of collective action by women factory workers may sometimes spill over (Silvey Citation2003), working class women are generally pushing against social as well as ideological tides (Ong Citation1987).

Conclusion

In outlining key aspects of the patriarchy of accumulation in two West Java villages, this article has shown that the reproduction-production nexus cannot be understood in a linear sense. It has also illustrated how the gendered exploitation of classes of labour in its more concrete forms is related to the broader dynamics of accumulation in Indonesia and beyond. Pluri-activity of classes of labour and the numerical weight of petty forms of capital are key features of the Indonesian economy, as they are in much of the Global South (and increasingly the Global North). To a considerable degree, then, accumulation on a world scale works its way through the appropriation of the time and labour of working-class women labouring in combinations of often scarcely visible forms of informal wage-labour and PCP.

The structure of the economy conceals the many ways in which their labour contributes to capital accumulation: as the main providers of the means of labour-power; as members of pluri-active classes of labour that push down wage levels across society; as homeworkers yielding surplus labour and providing surplus value for petty capital and for capital-in-general; as providers of cheap services – both via petty capitalist employers and directly as PCPs who cut the reproductive labour time of others; and as paddy cultivators subsidising the capitalist system with cheap food-grains derived, like everything, through gendered divisions of labour that form part of a coherent whole restricting women’s social space, lengthening her working days and lowering her wages.

The routes out of place-bound patriarchy in the fieldwork villages are limited, and in most cases only attainable through husbands and relatives. Patriarchal ideology, once so crudely propagated by the state, still circumscribes what is possible for working-class women – in their own minds as well as others’. Structural change slowly expands the spaces of working-class reproduction, but the everyday struggle to make ends meet renders notions of collective action fanciful for most. Concessions extracted from sympathetic pockets of the state may galvanise some gains for working class women (Robinson Citation2009), and collective action on more amenable terrain, like that which swept Bandung’s garment factories a generation ago, can cause ripples on the periphery and occasionally coalesce into movements aimed at more substantive change. In the meantime, there is a role for better understanding of the many aspects of the patriarchy of accumulation that are realised through the nexus of production and reproduction – two analytically distinct spheres that together underpin contemporary capitalism and its assiduous exploitation of working-class women.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank his co-researcher Mia Wastuti for indefatigable data collection and companionship, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Pattenden

Jonathan Pattenden is at the University of East Anglia in the UK. He is author of the monograph Labour, State and Society in Rural India: A Class-Relational Approach, and an editor of the Journal of Agrarian Change. His work on agrarian political economy and political sociology has been published in journals such as Development and Change, the Journal of Peasant Studies, Global Labour Journal, and the Journal of Agrarian Change.

Notes

1 Patriarchy tends to serve the interests of capital and is shaped by capitalists for such ends (e.g. Kalb Citation2004), but it does not always serve its interests. Excessive appropriation of female labour can undermine the capacity to work (Fraser Citation2017), and patriarchy can obstruct women from seeking employment (as in some dominant caste households of better-off farmers in India [Pattenden Citation2016]). It can also help women to exit from harsh forms of low-paid work (Heyer Citation2015).

2 Term is from Mies (Citation1986).

3 Reproductive labour is appropriated to varying degrees – less in Li’s (Citation2013) remote fieldwork areas in northern Sulawesi than in this article’s fieldwork villages, which are more thoroughly integrated into capitalist social relations.

4 Petty forms of self-employment that produce goods or services at a level that contributes part or all of a household’s living, but without any accumulation.

5 This was an estimate. While most households could be characterised as primarily PCP or primarily wage-labour, this was not the case for some households that were only surveyed, and had similar amounts of both. The margin of error for these figures may be as much as 5 per cent.

6 This includes the work of White, Stoler, Wiradi and Hart among others (see Pattenden and Wastuti Citation2021).

7 There is a long history of research on this in Indonesia. See, for example, Hartiningsih (Citation2000).

8 Typically around four, with additional fall-back options for poorer households (such as fodder collection).

9 One bata (term used locally to measure land) is 14 m2. One hectare is 714 bata.

10 Government-owned land rented out by the kampung’s representative on the village council.

11 Deep-fried vegetables, cassava dumplings and meat balls (especially the former; the latter are mostly made by men).

References

- Baglioni, Elena. 2021. “The Making of Cheap Labour Across Production and Reproduction. Control and Resistance in the Senegalese Horticultural Value Chain.” Work, Employment and Society, early view.

- Bakker, Isabella, and Stephen Gill. 2019. “Rethinking Power, Production, and Social Reproduction: Toward Variegated Social Reproduction.” Capital & Class 43 (4): 503–523.

- Bernstein, Henry. 2006. “Is There an Agrarian Question in the 21st Century?” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 27 (4): 449–460.

- Bhattacharya, Tithi, ed. 2017. Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. London: Pluto.

- Blackwood, Evelyn. 2008. “Not Your Average Housewife: Minangkabau Women and Work.” In Women and Work in Indonesia, edited by M. Ford and L. Parker, 17–40. London: Routledge.

- Boserup, Esther. 1970. Woman’s Role in Economic Development. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Burawoy, Michael. 1985. The Politics of Production. London: Verso.

- Carswell, Grace, and Geert De Neve. 2013. “Labouring for Global Markets: Conceptualising Labour Agency in Global Production Networks.” Geoforum 44 (1): 62–70.

- Da Corta, L., and D. Venkateshwarlu. 1999. “Unfree Relations and the Feminisation of Agricultural Labour in Andhra Pradesh, 1970-95.” Journal of Peasant Studies 26 (2-3): 71–139.

- Federici, Silvia. 2004. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia.

- Ferguson, Susan. 2016. “Intersectionality and Social-Reproduction Feminisms.” Historical Materialism 24 (2): 38–60.

- Fraser, Nancy. 2017. “Crisis of Care? On the Social-Reproductive Contradictions of Contemporary Capitalism.” In Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, edited by T. Bhattacharya, 21–36. London: Pluto.

- Hartiningsih, Maria. 2000. “Women Workers in the Putting-Out System: An Undemanding and Unrecognised Labour Force.” In Indonesian Women: The Journey Continues, edited by M. Oey-Gardiner and C. Bianpoen, 203–223. Canberra: ANU.

- Heyer, Judith. 2015. “Dalit Women Becoming ‘Housewives’: Lessons from the Tiruppur Region, 1981-82 to 2008-09.” In Dalits in Neoliberal India, edited by Clarinda Still, 228–255. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kalb, Don. 2004. “‘Bare Legs Like Ice’: Recasting Class for Local/Global Inquiry.” In Critical Junctions: Anthropology and History Beyond the Cultural Turn, edited by D. Kalb and H. Tak, 109–136. New York: Berghahn.

- Kandiyoti, Deniz. 1988. “Bargaining with Patriarchy.” Gender & Society 2 (3): 274–290.

- Koo, Hagen. 2001. Korean Workers: The Culture and Politics of Class Formation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Li, Tania. 2013. Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mather, Celia. 1983. “Industrialization in the Tangerang Regency of West Java: Women Workers and the Islamic Patriarchy.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 15 (2): 2–17.

- Mezzadri, Alessandra. 2020. “A Value Theory of Inclusion: Informal Labour, the Homeworker and the Social Reproduction of Value.” Antipode, early view.

- Mies, Maria. 1982. The Lacemakers of Narsapur. London: Zed.

- Mies, Maria. 1986. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. London: Zed.

- Ong, Aihwa. 1987. Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline: Factory Women in Malaysia. Albany: State University Press of New York.

- Ong, Aihwa, and Michael Peletz. 1995. Bewitching Women, Pious Men: Gender and Body Politics in Southeast Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Pattenden, Jonathan. 2016. Labour, State and Society in Rural India: A Class-Relational Approach. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Pattenden, Jonathan, and Mia Wastuti. 2021. “Waiting for the Call to Prayer: Exploitation, Accumulation and Social Reproduction in Rural Java.” Journal of Peasant Studies, early view.

- Pattenden, Jonathan, and Mia Wastuti. Forthcoming. “From Kampung to Kota: Labour, Migration, and the Political Economy of Accumulation in Java.”

- Rioux, Sébastien. 2015. “Embodied Contradictions: Capitalism, Social Reproduction and Body Formation.” Women's Studies International Forum 48: 194–202.

- Robinson, Kathryn. 2009. Gender, Islam and Democracy in Indonesia. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sanyal, Kalyan. 2007. Rethinking Capitalist Development: Primitive Accumulation, Governmentality and Post-Colonial Capitalism. New Delhi: Routledge.

- Silvey, Rachel. 2003. “Spaces of Protest: Gendered Migration, Social Networks, and Labor Activism in West Java, Indonesia.” Political Geography 22 (2): 129–155.

- Stoler, Ann. 1977. “Rice Harvesting in Kali Loro: A Study of Class and Labour Relations in Rural Java.” American Ethnologist 4 (4): 687–697.

- Wolf, Diane. 1990. Factory Daughters: Gender, Household Dynamics, and Rural Industrialization in Java. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Young Park, Clara, and Margherita Maffii. 2017. “‘We Are Not Afraid to Die’: Gender Dynamics of Agrarian Change in Ratanakiri Province, Cambodia.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (6): 1235–1254.