ABSTRACT

This paper uses survey data from the Mekong River Delta region of Vietnam to explore the equity implications of export-oriented agrarian transitions in two communities, one engaged in intensive rice agriculture and the other shrimp farming. The data show that shrimp aquaculture has brought greater inequality in the distribution of land, while generating more employment and economic opportunity and creating a more equitable distribution of income than rice farming. This study suggests that processes of agrarian transition can shape social relations around land and labour in divergent ways, due to differences in the nature of export commodities and their production.

RÉSUMÉ

Dans cet article, nous analysons les données obtenues lors d’une étude effectuée dans la région vietnamienne du delta de la rivière du Mékong afin de comprendre l’impact que les transitions agraires axées sur l’exportation peuvent avoir sur l’équité dans deux communautés, l’une engagée dans la riziculture intensive, et l’autre dans l’élevage de crevettes. Les données recueillies dans cette étude indiquent que l’aquaculture de la crevette a provoqué plus d’inégalités dans le partage des terres, tout en générant plus d’emplois et d’opportunités économiques, et en donnant lieu à une répartition des revenus plus équitable que la riziculture. Ces résultats suggèrent que les processus de transition agraire peuvent influencer le rapport entre les relations sociales, la terre et le travail de différentes façons, du fait des différences qui existent dans la nature des produits d’exportation et dans leur production.

Introduction

Since the implementation of Đổi Mới reforms in the 1980s, the Mekong River Delta region of Vietnam has undergone a rapid shift towards export-oriented production of agricultural commodities. Export-oriented agriculture is not new to the region – which was among the world’s most important producers of rice and rubber during the era of French colonial (Brocheux and Hémery Citation2009, 123–128) – but it was disrupted by the socialist economic policies imposed at the conclusion of the Vietnam War in 1975. Since the 1990s, however, the region has once again emerged as a major supplier of agricultural commodities to the world market. These include the region’s traditional crop, rice; the Mekong Delta now produces more than 20 million tons per year, accounting for more than half of Vietnam’s overall output and 90% of its rice exports (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Citation2017; The Anh, Van Tinh, and Vang Citation2020). However, the region has also experienced the explosive growth of other crops, driven by Vietnam’s reintegration into the global market in 1990s and 2000s. Among the most notable of these new crops is farmed seafood, much of which is exported to the Global North. The production of farmed shrimp in Vietnam has exploded, from 55,300 tons in 1995 to 634,800 in 2015 (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Citation2017). As with rice, the vast majority of that production is concentrated in the Mekong Delta, making that region the hotbed of commercialised and export-oriented agriculture and aquaculture.

This study explores the connection between export-oriented crop production and distributional equity, looking specifically at changes in the distribution of land and income that have accompanied the growth of export-oriented production in two rural communities in the Vietnamese province of Bạc Liêu, in the Mekong Delta. Each of these communities is involved in a different form of export-oriented production, one based on the intensive cultivation of rice and the other a shift to shrimp aquaculture, allowing for a comparison of these systems and their tendencies to generate inequality in the distribution of land and income. What I find is that while both forms of production have generated increasing landlessness and inequalities in the distribution of land, they differ, however, in the degree of economic inequality that they have engendered.

From this, I argue that export-oriented agrarian transitions can have divergent effects on equity, even within a confined geographic area, depending on the nature of the crop being produced (be it rice, shrimp, or some other commodity) and the specific ways in which capital is accumulated (such as the expansion of the area under production or the intensification of production using new chemical, mechanical, and biological inputs) by commercial producers. By using detailed survey data from these two geographic areas at two points in time, this study contributes to our understanding of export-driven agrarian transitions, especially regarding the ways in which peasant producers are – or are not – separated from the land and the ways in which their labour is – or is not – incorporated into export-oriented production.

Literature review

The value of global trade in food is increasing, especially the value of South-South and South-North trade (Kastner, Kastner, and Nonhebel Citation2011). This is due to increased trade in staple grains, such as rice, as well as high-value commodities such as ‘cocoa, coffee, fast-growing trees, oil palm, rubber and shrimp’ (Hall Citation2011a, 838). The increasing importance of export-oriented production in Vietnam, as elsewhere in the Global South, indicates an ongoing ‘agrarian transition’, defined by Byres as the process by which ‘capitalism becomes the dominant mode of production in agriculture’ (Citation1977, 258). As Turner and Caouette note, this transition consists of a ‘range of processes that link a country’s agricultural sector with the market economy to a far greater extent than ever before’ (Citation2009, 953), and thus the increased dependence of rural people on markets, both for the sale of agricultural commodities (as well as labour, and sometimes land) and the purchase of inputs and consumer goods (Wood Citation2002).

Agrarian transitions have been conceptualised through Kautsky’s original formulation of the ‘agrarian question’ as ‘whether, and how, capital is seizing hold of agriculture, revolutionising it, making old forms of production and property untenable and creating the necessity for new ones’ (Citation1988, 12) Building on Kautsky’s ‘agrarian question of capital’, more recent scholars have formulated related ‘agrarian questions’ relevant to ongoing processes of export-oriented agrarian transitions. These include the ‘agrarian question[s] of land’ namely ‘who controls it, how it is controlled, and the purpose for which it is controlled’ (Akram-Lodhi, Kay, and Borras Citation2009, 217). Bernstein (Citation2004) has also recognised within Kautsky’s framing of the classical agrarian question an implicit ‘agrarian question of labour’, regarding the fate of dispossessed farmers and their potential absorption into other sectors (see also Moyo, Jha, and Yeros Citation2013).Footnote1

Based on Marx’s formulation of ‘primitive accumulation’ as a historical and theoretical template for accumulation in agriculture, the answers to these agrarian questions would seem to be straightforward. To Marx, primitive accumulation is ‘a process that transforms, on one hand, the social means of subsistence and of production into capital’ and ‘on the other, the immediate producers into wage-labourers’ (Marx Citation1906, 786). That is, the separation of the peasants from their traditional means of subsistence (in Marx’s example, common lands worked by English peasants) would not only create a base of capital for the development of commercial agriculture but also a newly proletarianised class of workers dependent on wage labour for their survival. As Akram-Lodhi and Kay (Citation2010) note, ‘for many readers of Marx it appears that the outcome of the introduction of capitalist relations of production into agriculture must inevitably be the emergence of agrarian capital and agrarian wage labour’ (182).

In the Global South more broadly and in Southeast Asia specifically, we can see cases of export-driven agrarian transition that do indeed look very much like Marx’s classic formulation of primitive accumulation. Across the Global South, for example, corporate and state actors have forcibly dispossessed farmers and forest users to amass large holdings for export-oriented agriculture; this phenomenon of ‘land grabbing’ is especially prevalent in Southeast Asia (Schoenberger, Hall, and Vandergeest Citation2017). Working in Laos, for example, both Ian Baird (Citation2011) and Miles Kenney-Lazar (Citation2012) have noted the impacts of such land grabs, both on the accumulation of capital by foreign agribusiness and on the labour of displaced land users. Kenney-Lazar (Citation2012), for example, finds that villagers in the Lao highlands have lost significant access to forest resources through land acquisitions by the Vietnamese rubber company HAGL and have as a result been rendered partly dependent on waged work on the new rubber plantation, which he dubs a process of ‘semi-proletarianization’. Baird (Citation2011), meanwhile, argues that such grabs are facilitated by a Lao state that is fixated on a developmental project of turning ‘land into capital’ and ‘people into labour’.

In rural Vietnam – and in many other parts of Southeast Asia and the Global South – large-scale land grabs have played a less important role in processes of export-oriented agrarian transition than more gradual or subtle processes of accumulation. For example, the available literature on agriculture in the Mekong Delta suggests that, rather than a single act of primitive accumulation, there is an ongoing process of land accumulation that has been taking place in the region since the 1990s, as relatively prosperous farmers acquire land from their neighbours for rice production and horticulture (Akram-Lodhi Citation2005, Citation2010; Trần Citation2018). Akram-Lodhi dubs this process one of ‘rich peasant accumulation’, and describes the ways in which economic integration and the liberalisation of tenure have created conditions for class differentiation and increasing polarisation in the distribution of agricultural land. As he puts it, ‘it appears that processes of peasant class differentiation are underway, with the apparent emergence of a stratum of rich peasants with relatively larger landholdings’, while below this group sit the ‘rural landless, whose numbers are swelling as the agrarian transition proceeds’ (Citation2005, 107); for these new landless, wage labour on larger farms represents a major source of employment (Trần Citation2018).

Such processes of what Hall, Hirsch, and Li (Citation2011) dub ‘everyday accumulation’ have also been observed among producers of other high-value export crops. In Li’s research among cacao farmers in Sulawesi, for example, she notes that there are active land markets, through which some farmers acquire larger holdings on which to engage in export-oriented production, while other farmers have sold off their holdings in the face of debt and other economic pressures (Hall, Hirsch, and Li Citation2011, 154–160). Such gradual processes of accumulation are also noted in the context of export-oriented shrimp aquaculture. For example, in her research on shrimp farming in the Mekong Delta province of Trà Vinh in Vietnam, Hong Anh Vu notes that many small farmers have attempted to cultivate shrimp and failed, forcing them to sell their land to either wealthier members of their own communities or to outsiders (Hong Anh Citation2011). Paprocki and Cons (Citation2014) note a similar tendency at work in the char lands of coastal Bangladesh; facing falling harvests and changing soil salinity as a result of marine shrimp farming by their neighbours, many small farmers have been forced to sell their land and abandon agriculture altogether.

The accumulation of land by wealthier farmers has, in some contexts, been accompanied by the at least partial transformation of the newly landless into a sort of agrarian proletariat. Both Akram-Lodhi (Citation2005) and Paprocki and Cons (Citation2014) note that some of those who have sold their land have become wage labourers for large farmers or shrimp cultivators. However, Li (Citation2011) notes that, in many cases, there is little demand for the labour of landless households among the cacao farmers (or nearby palm oil plantations) of Sulawesi. In short, these newly landless former peasants were not proletarianised as such but simply rendered surplus to the process of capital accumulation in export-oriented agriculture; as she puts it, ‘their land was needed, but their labour was not’ (Li Citation2011, 286). This decoupling between the imperative of accumulation and the need for newly proletarianised labour lies at the heart of Bernstein’s formulation of the ‘new’ agrarian question of labour (Citation2004). By this, he focuses on how a class of newly landless former farmers survive and reproduce itself through ‘insecure, oppressive and typically increasingly scarce wage employment and/or a range of likewise precarious small-scale and ‘informal economy’ survival activity’ (Bernstein Citation2010, 111).

From this brief survey of the relevant literature, one would logically expect the polarisation of land to accompany the rise of export-oriented agriculture and aquaculture in Vietnam. One would also expect increased distributional inequality in regard to income since the accumulation of productive land in the hands of a small class of commercial farmers would concentrate profits in their hands as well. Moreover, if former farmers are losing their land and becoming wage labourers, or if their labour is, as in the case of Li’s research, being rendered surplus to the needs of capitalist farmers, one would expect that landlessness would be accompanied by a loss of income and thus a widening gap between the rural poor and an emerging class of richer farmers.

The literature does, however, present two possible reasons for which such a rise in distributional inequality, either in land or income, may not accompany the growth in export-oriented production. The first is what Rigg (Citation2020) has described as the ‘persistence’ of peasant producers, especially in Southeast Asia. Defying predictions of their eventual demise, small-scale producers have successfully carved out niches for themselves in the export-oriented production of staple grains, as well as higher-value ‘boom crops’ (Hall Citation2011b). Vandergeest, Flaherty, and Miller (Citation1999, 584) make a similar finding in regard to shrimp aquaculture in Thailand, which is characterised by the ‘continued predominance of small and medium-sized’ producers. This body of scholarship suggests that the polarisation of land ownership may not in fact be an inevitable counterpart to the rise of export-oriented production, or that there may at least be factors that retard the accumulation of land by large producers and the loss or sale of land by smallholders.

Second, there is another body of literature that suggests that, even when there is a transition to large-scale commercial farming and a concomitant rise in rural landlessness, such a process may in fact result in greater equity in the distribution of income. Rigg (Citation2006) argues that ‘livelihoods and poverty are becoming de-linked from land (and from farming)’ in the Global South, and in Southeast Asia in particular, as ‘non-farm activities’ become more ‘central to rural livelihoods’, and as ‘an increasing number of rural households have no commitment to farming whatsoever’ (181–183). Under these circumstances, the trend towards ‘proletarianization’ can actually be a positive force in the lives and livelihoods of former peasant farmers and their families. When smallholder farmers sell (or ‘lose’) their land, they are not automatically rendered surplus or reliant on agrarian wage labour. Instead, many are ‘freed’ to pursue non-agricultural jobs in the industrial or service sectors, a process Bryceson describes as ‘de-agrarianization’ (Citation1997). For this reason, Ravallion and Van De Walle (Citation2008) argue that rising landlessness in rural Vietnam might actually be associated with poverty alleviation rather than immiseration.

Study sites and research methods

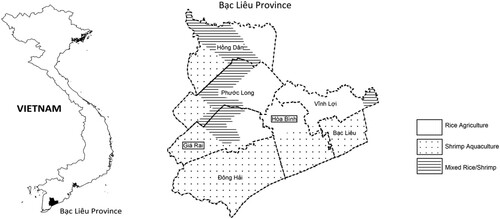

This paper seeks to assess the distributional impact of export-oriented agrarian transitions, comparing the ways in which two forms of production, rice agriculture and shrimp aquaculture, have restructured social relations around land and labour in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. To do so, I draw on survey data collected in two villages in Bạc Liêu province, which I pseudonymously dub Hòa Bình and Giá Rai (see ), after the larger districts in which they are located, at two points in time: 2001 and 2014. These sites are broadly representative of emerging hydrological zones linked to distinct modes of agriculture and aquaculture production. In 2001, residents of both villages engaged in rice agriculture as their predominant form of livelihood, but production was limited by the tidally driven intrusion of saltwater. However, environmental conditions and cropping patterns diverged dramatically in the 2000s, due to the construction and operation of a set of sluice gates and canals that sealed off the eastern part of the province (including Hòa Bình) from the influence of the tides and ensured a supply of irrigation water for intensive rice agriculture; meanwhile, farmers in the western half of the province (including Giá Rai) almost entirely abandoned rice agriculture, transformed their paddy fields into saltwater shrimp ponds.

The survey data for this study consists, first, of survey responses collected in 2001 by researchers from the International Rice Research Institute (Tran Citation2004), and second, of data collected in 2014 by the author and a team of research assistants from the Mekong Delta Development Research Institute at Cần Thơ University. The 2014 resurvey replicated the sampling approach of the original 2001 survey, which consisted of a full census of both villages. In 2001, 162 households in Hòa Bình village were surveyed, and in 2014, 223 were surveyed. In Giá Rai, 213 households were surveyed in 2001 and 324 in 2014.Footnote2 The overall response rate to these surveys was high, reflecting more than 90% of the reported population in these villages. The 2014 survey questionnaire largely replicated the one used in 2001, allowing for a comparison of household socio-economic conditions over time. These questionnaires also included sections on household demography (ages, occupations, and residential status of household members); on the use and ownership of productive assets like land; on cultivation activities, including income and production costs from agriculture and aquaculture; and on non-agricultural income sources such as wage labour and remittances. The survey was administered by research assistants, and data entry was performed electronically, via the tablet-based OpenDataKit software package.

It was possible to match some households between the 2001 and 2014 survey waves based on the age and name of the household head. On this basis, it is possible to compare the rate at which households ‘dropped out’ of the survey between waves, if not to give precise reasons as to why they were not present in 2014: in Giá Rai, 29.6% of households present in 2001 could not be matched to households in the 2014 wave, for Hòa Bình, the figure was 33.3%. In Giá Rai, the median age of household heads among those households that disappeared between waves was 49 years in 2001, compared to 43.5 for those matched between samples. This indicates that demographic factors (such as the dissolution of households due to the death or advanced age of household heads) may play some role in attrition. However, in Hòa Bình, the median age for heads of disappearing households (44.5 years) was younger than those for remaining households (46 years). This fact, coupled with the higher overall rate of attrition, indicates that out-migration may be a more significant phenomenon in this rice-growing village. Though data collection was, for practical reasons, constrained to the two study villages, one limitation of such a geographically-bounded approach is that the fates of these disappearing households remain unclear. It is possible that the village-level analysis that follows below fails to capture additional distributional inequalities that have their roots in village-level processes of accumulation and agrarian change, but which resulted in the geographical displacement of households between 2001 and 2014, and thus their omission from the second survey.

Finally, both villages also saw the formation of new households between 2001 and 2014. Of the households surveyed in 2014, 47.2% of households (including 46.3% in Giá Rai and 48.4% in Hòa Bình) could be matched to a household present in the 2001 sample. Again, the formation of new households can be driven by several factors (including the establishment of new households by village residents who formerly lived with parents or other family members), but these data suggest that the rate of in-migration may be slightly higher in the shrimp-farming village of Giá Rai.

Findings

Distribution of land

This analysis starts from the expectation that land is the ‘principal agrarian asset’ (Akram-Lodhi Citation2004, 763) and thus the primary, but not sole, basis for production and accumulation in agriculture and aquaculture. While land is the sine qua non of primary production, the centrality of land to accumulation varies with the biophysical form that production takes in a particular crop or sector, as well as the political-economic context in which that production is embedded. This section analyzes the changing distribution of land in both villages, as well as the potential mechanisms that have driven these changes.

Both waves of the survey gathered detailed information on all parcels for which households possessed land use rights. Land tenure in Vietnam is complex; technically, there is no private land ownership in Vietnam. Instead, households possess long-term tenure rights secured with an official title. These certificates were first issued in 1993 and were initially valid for a term of 20 years for paddy land and fully transferable (Marsh, Gordon MacAulay, and Van Hung Citation2006). Subsequent revisions to the Land Law in 1998, 2001, and 2003 created a liberalised market for the sale, transfer, lease, exchange, or mortgage of agricultural land. In 2013, the term of those certificates was extended another 30 years (Hirsch, Mellac, and Scurrah Citation2016).

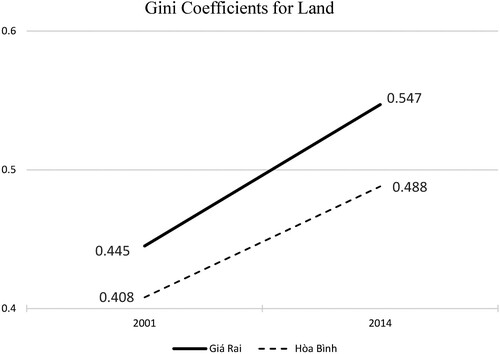

With that caveat in mind, I calculated Gini indexes for land holdings (that is, land for which households held long-term use rights) in 2001 and 2014, based on survey data collected in both years.Footnote3 The results are shown in . In both villages, inequality in the distribution of land rose. The Gini index for landholdings rose from 0.445 to 0.547 in Giá Rai, and from 0.408 to 0.488 in Hòa Bình.Footnote4 Inequality in the distribution of land tenure rose at a similar rate in both locations; however, the distribution of land was significantly more unequal in the shrimp-growing village of Giá Rai at both survey points. The rate of landlessness also rose in each location between 2001 and 2014. 6.3% of households in Hòa Bình were landless in 2014, an increase from 3.1% in 2001. The growth of landlessness was even more dramatic in Giá Rai; in 22.5% of households were landless, up from 7.5% in 2001.

At first glance, there seems to be ample evidence that the growth in export-oriented shrimp production has generated more inequality in the distribution of land than that of commercial rice agriculture. However, the data tell a more complex story. The share of households with fairly large areas of land under control (more than 2 hectares, in this case) has grown in the rice-growing village of Hòa Bình, while declining in Giá Rai. In other terms, large landowners seem to be growing as a class in Hòa Bình and shrinking in Giá Rai, complicating the initial impression made by the Gini coefficients alone. Large landowners (those with more than five hectares) actually control a larger portion of the total land in Hòa Bình (51 out of 352 hectares) than they do in Giá Rai (54 out of 416 hectares). Rather than being driven by the concentration of land among a new class of capitalist producers, increased land inequality in Giá Rai seems instead to be driven primarily by the rise in landlessness.

Distribution of income

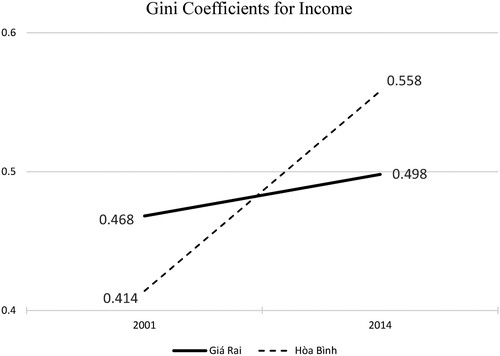

By calculating the Gini index for the distribution of income by household, we can see a different pattern emerge than that for land. As with land, the Gini coefficient for the distribution of land rose in both sites, indicating increased economic inequality, but at significantly different rates. Between 2001 and 2014, the Gini index for the distribution of income by household increased from 0.468 to 0.498 in Giá Rai and from 0.414 to 0.558 in Hòa Bình (see ). Hence, while the rise of shrimp aquaculture in Giá Rai has been accompanied by a modest increase in income inequality, the intensification of rice production in Hòa Bình has seen a much larger uptick in inequality.

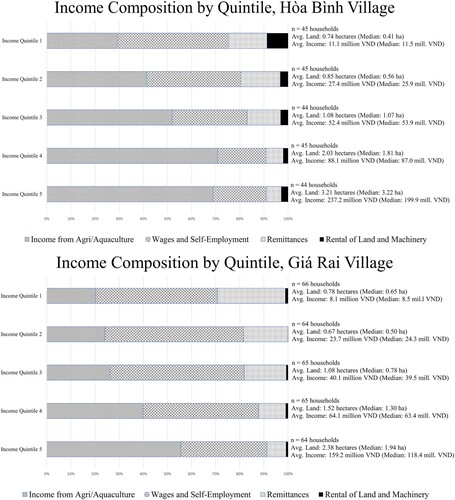

By dividing the households in both villages into income quintiles (with Quintile 1 representing the bottom 20% of the income distribution and Quintile 5 the top 20%) and calculating the mean income for households within each quintile (see ), we can better understand exactly how the study sites differ in the distribution of income. Hòa Bình has, overall, a higher income level, and the mean income for every income quintile is higher there than in Giá Rai. However, the gap between lower and higher income households is larger in Hòa Bình than in Giá Rai. The highest income quintile in Hòa Bình, for example, has an average household income of nearly 237 million Vietnam Dong per household, equivalent to more than $10,000 USD. It is this concentration of income among the upper income quintiles that drive the relatively rapid increase in inequality that has accompanied the commercialisation of rice agriculture. High-income households in Hòa Bình derive the bulk of their incomes from agricultural activities; in Hòa Bình, agriculture provides 70% and 69% of total income for those in the fourth and fifth quintiles, respectively. By contrast, aquaculture generates a more modest share of returns among upper income groups in Giá Rai, with only the uppermost quintile generating more than half (56%) of total income from shrimp farming. This leads us to believe that the polarisation and concentration of income in Hòa Bình is connected in a more direct sense to agricultural production and to the accumulation of land and other forms of capital among the richest households.

The survey data also allow for the calculation of income from other sources such as wages, self-employment, and remittances. One stark contrast between villages is the much greater importance of wages and self-employment to households in Giá Rai (and especially households in the lower income quintiles) than in Hòa Bình. Also of note is the differing importance of remittances. While the percentage of households with migrant members is roughly the same between the two contexts: 40.8% in Hòa Bình and 40.6% in Giá Rai, the relative contribution of remittances to household incomes was higher in Giá Rai than Hòa Bình.

Connections between land and income

As we have seen, the distribution of both land and income is becoming more unequal in both locations, but with significant differences between villages. On the one hand, the distribution of land is becoming more unequal at a comparable pace, with the overall concentration of land higher in Giá Rai than in Hòa Bình. On the other, income inequality has risen sharply in Hòa Bình, while climbing only slightly in Giá Rai, and Hòa Bình now has a more unequal distribution of income than Giá Rai, despite its more egalitarian distribution of land and relatively low rates of landlessness. Clearly, the relationship between land and income is not the same between the two villages for reasons which have to do, in part, with the differing nature of rice agriculture and shrimp aquaculture.

One means of assessing the relationship between landholdings and income is to obtain correlation coefficients for two variables: total household landholdings and household income. Using the 2014 survey data from Giá Rai, I obtain a correlation coefficient of 0.340. In Hòa Bình, however, the correlation coefficient for agricultural income and land is 0.679. For both sites, the coefficient of correlation is significant at the 0.01 level. This simple test demonstrates that the relationship between land holdings and income from agriculture and aquaculture is stronger in Hòa Bình than in Giá Rai but does not yet provide an explanation for why this might be the case. If land holdings are a weaker determinant of income in the shrimp sector than it is in the rice sector, we must then turn our attention to the possible reasons why these two variables are more tightly linked for one village (and crop) than for the other.

Dividing the households by income quintile (see ) serves to visualise the differing relationship between land and income in each village. In Hòa Bình, where landholding size is more strongly correlated with total income, the average landholding rises with each income quintile, from 0.74 hectares for the lowest income quintile to 3.21 hectares for the highest quintile. In Giá Rai, however, the poorest quintile actually controls more land, on average, (0.78 hectares) than does the next-highest quintile (0.67 hectares). Average landholdings rise with each successive income quintile after that, but the wealthiest 20% of households in Giá Rai own, on average, only 2.38 hectares of land, compared with 3.21 hectares for their counterparts in Hòa Bình. The conclusion to be drawn from both this and the coefficients of correlation presented above is that having a large area of land does not produce the same gains in terms of income as it does in Hòa Bình.

Turning first to the data from Hòa Bình, it is relatively easy to explain why incomes from agriculture so closely follow landholdings. Nearly all agricultural households in the village practice rice agriculture and variability in rice yields is relatively low, with households harvesting 7.1 tons per hectare per crop of rice on average. In comparison to the province of Bạc Liêu as a whole, this level of productivity is fairly high, especially given that all rice-growing households in the village engage in the cultivation of three crops per year. In 2014, for example, the average yield across the province was 5.75 tons per hectare (General Statistics Office of Vietnam Citation2017). Given the ubiquity of triple-cropping and relatively high yields from rice agriculture in Hòa Bình, there are few opportunities to boost production past current levels; thus, the dominant accumulation strategy is one of land acquisition or scaling up rice production through the expansion of land under control.

Scaling up is not just, however, a pathway to accumulation but to survival as well: in the face of rising input costs and stagnant yields, the profits from rice agriculture are, at least on a per hectare basis, relatively meagre. A kilogram of paddy sells for roughly 5,000 VND (or $0.25), and after expenses, profits per hectare are clustered around 100 million VND (or $500) per crop. Barring a failed growing season, a hectare of land would thus provide about 30 million VND ($1500) in income over the course of a year. In a country where the average per capita income has recently surpassed $2000 per annum, this is barely sufficient to support an entire household. Rather, farmers in Hòa Bình reported that it was necessary to have at least three hectares of land in order to make a comfortable living from rice agriculture alone. Reaching such a scale requires, however, that households grow their holdings, and the only practical way to do so is by purchasing land from other households. Meanwhile, given the high fixed costs of intensive, mechanised rice production, rice farmers with small holdings of about 0.5 hectares or less (representing approximately 25% of Hòa Bình’s households) struggle to break even, creating pressures to sell their land and exit agriculture entirely.

In contrast, the relationship between area under production and income is more variable in the Giá Rai, and by inference, the shrimp sector at large, at least in its current form. The vast majority of shrimp farmers in Giá Rai follow the extensive model of cultivation, which uses purchased shrimp fry stocked at relatively low densities, with limited applications of antibiotics and fertiliser, as opposed to an intensive method that uses higher stocking densities, purchased feed, and mechanically operated pumps and fans to aerate ponds, requiring higher capital outlays (Joffre and Bosma Citation2009; Lan Citation2013). On the whole, however, returns from this extensive method are low, at least as compared to agriculture; the average profit among extensive shrimp farmers in Giá Rai was 14.7 million VND per hectare (or about $750) per year.

There exist, however, alternative pathways to accumulation in shrimp aquaculture that lie not in the acquisition of land but rather in the intensification of production. Such intensification can take the form of increased investments in improved inputs within the confines of extensive production. Some households have, however, made large capital investments in moving to intensive production, which requires higher outlays (for seed stock, antibiotics, electricity, labour for security as well as cleaning of ponds) but potentially yields much higher incomes. With this increased average profitability comes greater variability, however; of the five households raising intensive shrimp, two lost money, while one reported a profit of nearly 900 million VND (or $45,000) on three hectares of ponds.

Six households in Giá Rai were also engaged in an extremely capital-intensive form of shrimp aquaculture that required relatively little in the way of land: the raising of shrimp stock (giống) in concrete-lined ponds or tanks. These operations ranged in scale from 50 to 500 m2 but required capital outlays of upwards of 100 million VND ($5000) for the purchase of starter stock and equipment. While one farmer had lost his entire investment on a failed stock-raising venture, the five successful households had averaged 38.7 million VND in returns. Thus, the available pathways for accumulation in aquaculture lie not just through the acquisition of land, though that certainly has occurred, but through investments in inputs, as well as physical implements (such as fans) and modifications of the biophysical environment (such as through the digging, cleaning, and lining of shrimp ponds) that open up opportunities for more intensive production on existing land.

Discussion

The findings presented above indicate that the relationship between income and land is shifting, and while both modes of commercial production have gone hand-in-hand with increased inequality in the distribution of land, their implications for the distribution of income are very different. Since accumulation in the rice-growing community of Hòa Bình takes place primarily through the acquisition of land, there is a tendency for inequality in the distribution of land and income to rise in tandem. By contrast, pathways to accumulation exist in the shrimp sector that do not necessitate the displacement of other producers, as through the intensification of shrimp production on existing land, by means of investments in capital and inputs, thus weakening the connection between land inequality and income inequality.

While differences in the nature of production – and the prospects for intensification – in each village account for some of the observed variations in the relationship between control of land and income from agriculture and aquaculture, there are additional reasons for which rising inequality in land ownership has been accompanied by a far sharper increase in income inequality in Hòa Bình than in Giá Rai. Understanding processes of accumulation in Giá Rai and Hòa Bình thus requires that we look not just at the ways in which the ownership and control of land have changed, but at the new opportunities that these sectors have – or have not – generated for self-employment and wage labour.

A closer inspection of the survey data reveal that many households in Giá Rai, even if they are not directly involved in shrimp production, depend upon new forms of livelihood that are closely connected with the larger aquaculture sector. Once harvested, shrimp are extremely perishable, and since the requisite cold chains do not exist to transport them for long distances, they thus need to be processed close to their place of origin. As Hall notes, the ‘biological characteristics of shrimp are … exacting’; since they deteriorate quickly, shrimp ‘must be moved from harvest to freezing/processing as quickly as possible’ (Hall Citation2003, 255). For this reason, there is now a processing facility in the district town nearest to Giá Rai that prepares shrimp for freezing and export. Many people from Giá Rai village, especially young women, work at this facility, while continuing to reside in the village. Thus, the shift towards high-value production in Giá Rai generates off-farm employment opportunities that are absent in the rice sector and serves as a kind of lever for economic diversification. This diversification is marked by the proliferation of seafood processing facilities, as well as the rise of other businesses like the transportation and trading of shrimp and the cultivation and sale of shrimp fry. The overall result is that the shrimp boom has brought opportunities for ancillary businesses not just for the poor but also for the wealthiest households in Giá Rai, serving to direct accumulation out of the acquisition of land and into other venues, many of which remained tied to shrimp farming and processing for export. One of the households with the largest holdings of shrimp-farming land was, for example, deriving a significant percent of its overall income not from direct production but from the buying and selling of shrimp; the household, headed by a man in his late 30s, had even purchased a truck, with which he gathered shrimp from farmers in the village, which he packed with ice and transported to the processing plant in the district town.

As we have seen, the connection between land and income is stronger in the rice-growing village of Hòa Bình than in the shrimp-farming village of Giá Rai. This suggests that incomes – and, by extension, economic activities at the household level – are becoming decoupled from land ownership in Giá Rai (if not in Hòa Bình). This trend is evidenced in Giá Rai by the relatively low share of household income generated by direct aquaculture production, as households, even those who still own and cultivate land, derive a greater and greater proportion of their incomes not from direct production, but from wage labour and non-agricultural self-employment. In this way, sector-wide accumulation in shrimp aquaculture generates new economic opportunities for residents of Giá Rai village, both in the realm of wage labour and self-employment, that serve to attract or ‘pull’ small shrimp farmers out of direct production.

Such a process, however, has not taken place in Hòa Bình. There, there is little investment or accumulation by rich households outside land and machinery for rice cultivation, and accumulation in the rice sector has generated few economic opportunities for smaller farmers and land-poor households. The lack of economic viability for small-scale rice farming is compounded by the disappearance of wage labour opportunities in the agricultural sector itself. In the past, many poorer farmers were able to supplement their incomes by performing seasonal work on the farms of their neighbours, especially at harvest time. With the recent turn to mechanised combine harvesters, however, this source of income has evaporated. This trend towards mechanisation has been exacerbated by reliance on harvesting teams from other provinces; these teams transport combine harvesters on barges around the Mekong Delta, travelling from place to place based on local cropping calendars (see also Prota and Beresford Citation2012 and The Anh, Van Tinh, and Vang Citation2020). In a focus group interview before the survey, a group of representatives from poor households reported that the use of combine harvesters, which were introduced about 4–5 years prior to the survey, had served to steadily erode their prospects for wage labour. As one woman in her forties reported, Hồ Chí Minh City. ‘There’s too much labour in the countryside and not enough work’, she explained. ‘That’s why everyone has to go to the city or to Bình Dương’, an industrial area to the northeast.

Conclusion

As demonstrated above, these two cases display very different tendencies in terms of distributional equity, both in terms of land and income. These findings help illuminate the varying ways in which export-oriented agrarian transitions have reconfigured social relations around land and labour in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta region.

The pathway of agrarian transition in Hòa Bình, oriented towards intensive rice agriculture for domestic consumption and export markets, has resulted in considerable accumulation; in economic terms alone, the value of rice production remains significantly higher than shrimp production in Giá Rai, though the ongoing intensification of shrimp aquaculture may eventually narrow this gap. This accumulation has been fuelled by the acquisition of land by large producers, in a process mirroring the ‘rich peasant’ accumulation described by Akram-Lodhi. Although small farmers have to some degree persisted, they have gradually lost ground, both in terms of their control over land and their relative incomes, in comparison to their larger counterparts. While the loss of land by smaller farmers has, given constraints on the overall supply of land, been an inevitable corollary to the accumulation of land by large, commercial producers, intensive rice production has generated little in terms of employment opportunities for the newly landless or land-poor. In this way, the process of agrarian transition in Hòa Bình resembles that observed by Li in Sulawesi: though their land is needed for capital accumulation by their wealthier counterparts, the labour of the rural poor is not.

In Giá Rai, meanwhile, the untapped possibility of intensification within shrimp aquaculture channels accumulation tendencies towards investments in capital – rather than the acquisition of land – thus allowing highly-capitalised modes of intensive production to exist, at least for the time being, side-by-side with more extensive modes of production that remain economically viable for smaller-scale producers, a sign of what Rigg and others might describe as ‘peasant persistence’. Meanwhile, the proliferation of ancillary enterprises has opened up pathways for both accumulation (as in the buying and selling of shrimp) and wage labour in the shrimp sector more broadly, creating positive incentives for diversification and transition out of direct production. This proliferation of wage labour and self-employment around shrimp aquaculture, combined with remittance income, has allowed both the rural landless and small-scale producers to keep relative pace with richer shrimp farmers, leading to lower levels of income inequality than in the rice-growing village of Hòa Bình. Significantly, these relatively equitable outcomes have not followed a process of de-agrarianisation, as export-oriented aquaculture remains essential to both the livelihoods of the rural poor and those of the higher income quintiles. Rather than a process of de-linking livelihoods from the land or shifting capital accumulation to a non-agrarian base, the shrimp boom in Giá Rai can be more accurately described as the elaboration of an export-oriented agri-processing industry with a considerable demand for local labour. Some of this labour is indeed tedious and low-paying, as in the shrimp processing factories of the district town, which points to the emergence of a new rural proletariat in the shrimp-farming zone of the coastal Mekong Delta. But unlike their counterparts in the rice-growing land of Hòa Bình, the former farmers and remaining smallholders of Giá Rai have indeed found that, more so than their land, it is their labour that is necessary for capital accumulation in export-oriented shrimp aquaculture.

As we have seen, the perishable nature of shrimp itself, the labour-intensive nature of shrimp processing, and the relatively dispersed, decentralised nature of shrimp farming have generated ancillary livelihoods that have serve to replace or supplement farming itself as primary income sources, not just for the poor, but for a broad cross-section of rural households in Giá Rai. Whether the accumulation of capital in the shrimp sector will continue to produce relatively broad-based economic opportunities, however, remains to be seen. Recently, there has been a shift towards greater consolidation in Vietnam’s shrimp sector, as export-processing companies become more directly involved in the production of shrimp on a large scale, rather than relying on traders or buying from shrimp farmers. This shift is driven primarily by the need to ensure rigorous quality control and food safety standards for foreign buyers but stands to erode the position of independent shrimp farmers, both large and small, and the livelihoods of those who have carved out a living providing services to these farmers. It is possible that the survey data were collected in a transient period in which rapid export-driven growth produced broadly equitable, pro-poor outcomes – a brief stop, perhaps, on the road towards a more consolidated, capitalised, and industrialised shrimp complex – so future data collection will be needed to determine whether or not such positive outcomes have indeed been sustained.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timothy Gorman

Timothy Gorman is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Montclair State University in the United States.

Notes

1 This is distinct from the Bernstein’s delineation of the ‘new’ agrarian question of labour, discussed below.

2 This paper follows Schmink (Citation1984) in defining the household as a ‘co-resident groups of persons, who share most aspects of consumption, drawing on and allocating a common pool of resources (including labour) to ensure their material reproduction’ (89). The use of the household as both the unit of data collection and empirical analysis was informed not just by practical concerns (the previous iteration of the survey data was collected at the household level, and the household, or hộ, is also a unit of political administration in Vietnam) but by the continuing position of households as the primary unit of production and social organization in rural Vietnam. It is, however, important to note at the outset that are limitations and risks to such an approach. One, as Schmink points out, is the ‘danger reifying the household unit and ignoring other organizational forms’ (Citation1984, 94); the other is the risk of ignoring gendered power dynamics at the intrahousehold level (Deere Citation1995).

3 The Gini index is a means of measuring distributional inequality, in which 0 indicates a perfectly equal distribution and 1 a perfectly unequal distribution. Gini coefficient values were calculated using the Ineqdec0 module for Stata (Jenkins Citation1999).

4 For the 2014 survey data, it was possible to calculate total land under cultivation by each household by excluding land rented, mortgaged or lent out by households, while including land rented, mortgaged, or lent to them. This may provide a better picture of land inequality than the possession of land use rights alone. By this calculation, the Gini index for land under cultivation in Giá Rai was 0.537 (as compared to 0.547 for land tenure). In Hòa Bình, however, the Gini index for land under cultivation was 0.532, significantly higher than the figure of 0.488 for land tenure, indicating a higher level of distributional inequality.

References

- Akram-Lodhi, A. 2004. “Are Landlords Taking Back the Land'? An Essay on the Agrarian Transition in Vietnam.” European Journal of Development Research 16 (4): 757–789.

- Akram-Lodhi, A. Haroon. 2005. “Vietnam's Agriculture: Processes of Rich Peasant Accumulation and Mechanisms of Social Differentiation.” Journal of Agrarian Change 5 (1): 73–116. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2004.00095.x.

- Akram-Lodhi, A. H. 2010. “Review Essay: Land, Labour and Agrarian Transition in Vietnam.” Journal of Agrarian Change 10 (4): 564–580. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2010.00286.x.

- Akram-Lodhi, A. Haroon, and Cristóbal Kay. 2010. “Surveying the Agrarian Question (Part 1): Unearthing Foundations, Exploring Diversity.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 37 (1): 177–202. doi:10.1080/03066150903498838.

- Akram-Lodhi, A. Haroon, Cristóbal Kay, and Saturnino M. Borras Jr. 2009. “The Political Economy of Land and the Agrarian Question in an Era of Neoliberal Globalization.” In Peasants and Globalization: Political Economy, Rural Transformation and the Agrarian Question, edited by A. Haroon Akram-Lodhi and Cristóbal Kay, 214–238. London: Routledge.

- Baird, Ian G. 2011. “Turning Land Into Capital, Turning People Into Labor: Primitive Accumulation and the Arrival of Large-Scale Economic Land Concessions in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic.” New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 5 (1): 10–26.

- Bernstein, Henry. 2004. “‘Changing Before Our Very Eyes’: Agrarian Questions and the Politics of Land in Capitalism Today.” Journal of Agrarian Change 4 (1-2): 190–225. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2004.00078.x.

- Bernstein, Henry. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Halifax: Fernwood Pub., Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press.

- Brocheux, Pierre, and Daniel Hémery. 2009. Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonization, 1858-1954. [English-Language ed] from Indochina to Vietnam. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bryceson, Deborah Fahy. 1997. Farewell to Farms De-Agrarianisation and Employment in Africa. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Byres, T. J. 1977. “Agrarian Transition and the Agrarian Question.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 4 (3): 258–274. doi:10.1080/03066157708438024.

- Deere, C. D. 1995. “What Difference Does Gender Make? Rethinking Peasant Studies.” Feminist Economics 1(1): 53–72. doi:10.1080/714042214.

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam. 2017. Sản lượng lúa cả năm phân theo địa phương (Annual Rice Production by Locality). http://www.gso.gov.vn/SLTK/Menu.aspx?rxid = c30ee742-6436-43dc-a38c-a8a6f120d199&px_language = vi&px_db = 06.+N%C3%B4ng%2C+l%C3%A2m+nghi%E1%BB%87p+v%C3%A0+th%E1%BB%A7y+s%E1%BA%A3n&px_type = PX.

- Hall, Derek. 2003. “The International Political Ecology of Industrial Shrimp Aquaculture and Industrial Plantation Forestry in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 34 (2): 251–264. doi:10.1017/S0022463403000249.

- Hall, Derek. 2011a. “Land Grabs, Land Control, and Southeast Asian Crop Booms.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (4): 837–857. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.607706.

- Hall, Derek. 2011b. “Where the Streets Are Paved with Prawns.” Critical Asian Studies 43 (4): 507–530. doi:10.1080/14672715.2011.623518.

- Hall, Derek, Philip Hirsch, and Tania Li. 2011. Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawai′i Press.

- Hirsch, Philip, Marie Mellac, and Natalia Scurrah. 2016. The Political Economy of Land Governance in Viet Nam. Vientiane, Lao PDR: Mekong Region Land Governance.

- Hong Anh, Vu. 2011. “Moral Economy Meets Global Economy: Negotiating Risk, Vulnerability and Sustainable Livelihood Among Shrimp Farming Households in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta.” Ph.D., Anthropology, Syracuse University.

- Jenkins, Stephen P. 1999. INEQDEC0: Stata Module to Calculate Inequality Indices with Decomposition by Subgroup. Boston: Boston College Department of Economics.

- Joffre, Olivier M., and Roel H. Bosma. 2009. “Typology of Shrimp Farming in Bac Lieu Province, Mekong Delta, Using Multivariate Statistics.” Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 132 (1): 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2009.03.010.

- Kastner, Thomas, Michael Kastner, and Sanderine Nonhebel. 2011. “Tracing Distant Environmental Impacts of Agricultural Products from a Consumer Perspective.” Ecological Economics 70 (6): 1032–1040. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.01.012.

- Kautsky, Karl. 1988. The Agrarian Question: In Two Volumes. Vol. I. Winchester, MA: Zwan Publications.

- Kenney-Lazar, Miles. 2012. “Plantation Rubber, Land Grabbing and Social-Property Transformation in Southern Laos.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3-4): 1017–1037. doi:10.1080/03066150.2012.674942.

- Lan, Ngo Thi Phuong. 2013. “Social and Ecological Challenges of Market-Oriented Shrimp Farming in Vietnam.” SpringerPlus 2 (1): 675. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-675.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2011. “Centering Labor in the Land Grab Debate.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (2): 281–298. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.559009.

- Marsh, Sally P., T. Gordon MacAulay, and Pham Van Hung. 2006. Agricultural Development and Land Policy in Vietnam. Canberra: ACIAR.

- Marx, K. 1906. Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. New York: Modern Library.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. 2017. Cơ sở Dữ liệu về Thống kê - Thông tin An ninh Lương thực (Informational and Statistical Database on Food Security). Accessed May 10. http://fsiu.mard.gov.vn/data/trongtrot.htm.

- Moyo, Sam, Praveen Jha, and Paris Yeros. 2013. “The Classical Agrarian Question: Myth, Reality and Relevance Today.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 2 (1): 93–119.

- Paprocki, Kasia, and Jason Cons. 2014. “Life in a Shrimp Zone: Aqua- and Other Cultures of Bangladesh's Coastal Landscape.” Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 1109–1130. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.937709.

- Prota, Laura, and Melanie Beresford. 2012. “Emerging Class Relations in the Mekong River Delta of Vietnam: A Network Analysis.” Journal of Agrarian Change 12 (1): 60–80. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00334.x.

- Ravallion, Martin, and Dominique Van De Walle. 2008. “Does Rising Landlessness Signal Success or Failure for Vietnam's Agrarian Transition?” Journal of Development Economics 87 (2): 191–209. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.03.003.

- Rigg, Jonathan. 2006. “Land, Farming, Livelihoods, and Poverty: Rethinking the Links in the Rural South.” World Development 34 (1): 180–202. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.015.

- Rigg, Jonathan. 2020. Rural Development in Southeast Asia: Dispossession, Accumulation and Persistence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schmink, Marianne. 1984. “Household Economic Strategies: Review and Research Agenda.” Latin American Research Review 19 (3): 87–87.

- Schoenberger, Laura, Derek Hall, and Peter Vandergeest. 2017. “What Happened When the Land Grab Came to Southeast Asia?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (4): 697–725. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1331433.

- The Anh, Dao, Thai Van Tinh, and Nguyen Ngoc Vang. 2020. “The Domestic Rice Value Chain in the Mekong Delta.” In White Gold: The Commercialisation of Rice Farming in the Lower Mekong Basin, edited by Rob Cramb, 375–395. Singapore: Springer.

- Tran, Thi Ut. 2004. “Land and Water Resource Management in Coastal Areas.” In Working Paper Series, Resource Politics and Cultural Transformation in the Mekong Region. Chiang Mai: Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD), Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

- Trần, Hữu Quang. 2018. “Land Accumulation in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam: A Question Revisited.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D'études du Développement 39 (2): 199–214.

- Turner, Sarah, and Dominique Caouette. 2009. “Agrarian Angst: Rural Resistance in Southeast Asia.” Geography Compass 3 (3): 950–975.

- Vandergeest, Peter, Mark Flaherty, and Paul Miller. 1999. “A Political Ecology of Shrimp Aquaculture in Thailand.” Rural Sociology 64 (4): 573–596. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.1999.tb00379.x.

- Wood, Ellen Meiksins. 2002. “The Question of Market Dependence.” Journal of Agrarian Change 2 (1): 50–87.