ABSTRACT

Market gardening is an important contributor to food security and to the livelihoods of households in sub-Saharan Africa. Women represent an important share of this activity. Our goal in the present article is to draw attention to an overlooked area of the world that echoes many other situations. What is it like being a woman market gardener in Kinshasa? Using a qualitative methodology, we show that this strongly gendered activity is an important opportunity for women. However, they face a multiplicity of threats, intensified by their gender, regarding access to land, possibilities to organize, gender norms, and rights.

RÉSUMÉ

La culture maraîchère contribue de manière conséquente à la sécurité alimentaire et aux revenus des foyers en Afrique subsaharienne. Les femmes représentent une part importante de cette activité. L’objectif du présent article est d’attirer l’attention sur une région du monde que l’on a tendance à oublier, et dont les caractéristiques reflètent des situations similaires ailleurs dans le monde. Qu’est-ce que d’être une femme vivant de la culture maraîchère à Kinshasa ? En utilisant une méthodologie qualitative, nous démontrons que cette activité très genrée présente une opportunité importante pour les femmes. Cependant, elles font face à de nombreux obstacles, intensifiés par leur genre, et relatifs à l’accès à la terre, aux possibilités de s’organiser, aux normes de genres, et aux droits des femmes.

Introduction

Urban and peri-urban agriculture has been growing significantly in Africa in recent decades. As a result, it contributes significantly to the livelihoods of the households that practice it. In the present paper, we focus on one example of urban and peri-urban agriculture: market gardening. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as in many countries, market gardening contributes to food security. The population in the DRC languishes in high poverty and is among the poorest and hungriest on the planet. Indeed, in December 2019, the DRC had 15.58 million people in a situation of severe food insecurity (IPC Citation2019), while the World Bank estimated in 2017 a prevalence of extreme poverty at 80 per cent in the rest of the country, except around large cities such as Kinshasa and Lubumbashi, where it is estimated at 50 per cent (World Bank Citation2017). Urban and peri-urban market gardening supplies Kinshasa’s markets with fresh vegetables and thus contributes to food security.

Agriculture is an important sector for women in sub-Saharan Africa (Adekanye Citation1984). Women are in the social strata most affected by economic, social, and climatic crises, facing a multiplicity of threats. As a growing body of literature aims at understanding the barriers to women’s entrepreneurship in African countries and elsewhere, a better comprehension of the gender structures, threats, and representations of women is needed (Masika Citation2017). Following Chen, Vanek, and Heintz (Citation2006), efforts to combat poverty must pay greater attention to the needs and constraints faced by the working poor, both women and men. Understanding women’s realities and the diverse interests they may have is fundamental to drawing inclusive policies and improving the multi-layered structures of domination they encounter (Ghorayshi Citation1997). It is especially important as women’s wellbeing and empowerment have been emphasized more and more in international agreements that, unfortunately, often fail to achieve these goals (Larson et al. Citation2018). Following these trends to better understand gender roles and issues in developing countries, we focus on gender divisions in market gardening in the DRC. What is it like being a woman doing a subsistence job such as market gardening in a low-income country? How is the multiplicity of threats women can encounter translated in such an activity?

We aim to provide insights into the challenges faced by women in sub-Saharan Africa. If we want to achieve sustainable developments goals, we have to understand the situation of women, the opportunities offered to them, the threats they encounter, and their working conditions. Through a qualitative methodology, relying on many observations and interviews in one field, we elaborate a deeper understanding of the situation. We show that market gardening is an activity that people have been driven to, but it still offers important economic opportunities for women. It is also interestingly an activity that is strongly occupied by women, from the production of vegetables to reselling them. However, because of different external threats (land tenure, job market, poverty, conflicts), more and more men are becoming producers of vegetables. In this evolution of market gardening, we observe that if women and men share some common threats in a vulnerable and endangered activity, women suffer more, related to the structure of the activity but also to other lacks of capacities, such as the possibility to formally organize. We finally show the needed recognition of the voices of all, and especially traditionally silenced groups, in order to understand such complex situations and to be able to formulate policies for development.

Market gardening in Africa, a contribution to food security

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO Citation1999), peri-urban agriculture is practiced worldwide within or around the administrative boundaries of cities. It provides products from agriculture, livestock, fisheries, and forestry. The history of peri-urban agriculture is long-standing and linked to the colonial process. The first forms of peri-urban agriculture were intended to feed urban settlers and missionaries. The crops were then oriented toward the food needs of Westerners. The first practitioners of peri-urban agriculture were the missionaries’ servants and, later, peasants. These peasants diversified their knowledge based on what they learned from the missionaries (Nahmias and le Caro Citation2012). Doucouré and Fleury (Citation2004) point out that this agriculture contributes to the management of the city in several ways: by participating in the supply of fresh produce, by creating jobs and sources of income, and by occupying land that serves as tree spaces in the urban fabric, thus participating in the development of green spaces and improving air quality. Urban and peri-urban agriculture is a recurring theme in the literature of southern countries and is at the heart of many international cooperation projects (Rezelman Citation2009). Market gardening is a specific form of urban and peri-urban agriculture. The term “market gardening” was first applied to the cultivation of vegetables in swamps. This term has evolved over time and has become a branch of horticulture oriented toward the intensive and professional cultivation of vegetables. According to Moustier (Citation1998), in Africa, urban market gardening plays an important role in the urban economy. Most market gardening systems require little start-up manufactured capital. Thus, in a context of precarious employment, market gardening can represent a survival activity in an urban environment in order to self-generate income.

The contribution to food security is also important. It is estimated that 80 per cent of the vegetables sold in Kinshasa are produced by the city itself (CAVTK Citation2006). Market gardening contributes to the livelihoods of vulnerable populations. The DRC has settled for several years at the bottom of the annual human development ranking. In order to face this generalized crisis, people are constantly engaged in scavenging activities. Resourcefulness is based on informal activities, among which market gardening is almost in first place. Peri-urban agriculture has a long tradition in the DRC (Minengu, Mwengi, and Maleke Citation2018). However, this activity has grown, particularly since conflicts in the 1990s. Between 1995 and 2000, the population of Kinshasa, the capital, increased by more than one million. With its impoverished population and disrupted food supply, Kinshasa was experiencing severe food shortages, with child malnutrition rates on the rise. In the face of adversity, Kinshasa residents revived an age-old survival strategy. Throughout the city, residents began growing vegetables and root crops around their homes, in vacant lots, and along streets and waterways. The amount of land used for market gardening in and around the city increased rapidly. The new market gardeners were often displaced rural people who had settled on the outskirts of the city.

Following this evolution, in 1996, the Congolese government decided to set up the Service National d’Appui au Développement de l’Horticulture Urbaine et Périurbaine (National Service to Support the Development of Urban and Peri-Urban Horticulture, or SENAHUP) within the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock. Since 2000, this service has been working with professional associations of market gardeners at Kinshasa’s production sites to meet the growing demand for vegetables and fruit. It targets women market gardeners as a priority because an increase in their income benefits their entire families (Kuyengila and van Hoof Citation2010). However, the conditions under which Congolese market gardeners carry out their activities, as well as the risks related to land, marketing, and production, raise questions about their livelihoods and their futures. In addition, these market gardeners are also victims of threats from customary chiefs. There is a lot of ambiguity because several traditional chiefs are reappropriating land in different sites, with the aim of using it as a source of profit or reselling it. The customary chief is untouchable (Dumbi Citation2017).

Thus, market gardeners continue their activities while being aware of their exposure to various risks (eviction, theft, etc.) (Dumbi Citation2017). Nowadays, urban and peri-urban market gardening is one of the means of reducing poverty and food insecurity, but in such a precarious context, it is not excessive to speak of survival market gardening (Lallau and Dumbi Citation2007).

Multidimensional gender inequalities

Understanding women’s realities and the diverse interests they may have is fundamental to drawing inclusive policies and improving the multi-layered structures of domination they encounter (Ghorayshi Citation1997). The present section explores the multidimensional threats encountered by women: environmental, social, economic, and political. There is a need, according to the literature on intersectionalityFootnote1 but also practitioners and women in the field, for sex-differentiated questions related to wellbeing.

As pointed out by Spring (Citation2009), this situation correlates with other variables such as poverty and low education. Women’s lower incomes and poor job security are even worse because of external shocks like global warming as these conditions are hard to modify. Furthermore, the institutions are often unbalanced toward males in the first place (Branisa, Klasen, and Ziegler Citation2013). Women have limited access to human capital and agricultural inputs compared to men (Demetriades and Esplen Citation2008). Land tenure is another important issue. Several case studies refer to some intrinsic differences concerning the ways land is distributed: Perez et al. (Citation2014, 15) found that “Participants in all sites reported that both men and women have access to individual fields and communal ones, but only men own and inherit the land.” In addition to the unequal formal distribution of land, women farmers informally control less land than men as well: what they control is usually worse in quality and with insecure tenure. The women working the land are found to be less likely to be given access to the use of modern inputs such as improved seeds, fertilizers, machinery, and modern tools (Peterman, Behrman, and Quisumbing Citation2011).

The conditions of males and females are unequal from the start, where women are less educated than men and have less available free time and access to extensive resources, which makes it harder to overcome formal difficulties through a process of empowerment. Women carry all household responsibilities such as childcare and the collection of firewood and water (Kakota et al. Citation2011; Nelson and Stathers Citation2009). Perez et al. (Citation2014), analyzing a comparison between female-headed households and male-headed households, found that the former are more dependent on irregular income flows and remittances, and their employment is also less stable and more precarious, making them more insecure from a financial point of view. A great deal of existing anti-women bias potentially makes female-headed households lack so-called social capital, such as participation in networks and society (Lowndes Citation2004). Men and women would generally rely on different types of social relations for both their social and economic needs: women’s social relations tend to be based on informal channels, such as kinships or friendships, and they have more difficulties accessing information and formal organizations than men. Their networks, ranging from friends to relatives and community members, are based on mutual help and common risk-sharing as a kind of informal insurance. However, reciprocal help is not granted by definition (Molyneux Citation2002). Considering the consequences of climate change, because of all these reasons, women are far more impacted than men, and the low social development that concerns most women in Africa is a cause of their insufficient adaptive capacity. Climate change can at the same time reveal inequalities between men and women when they have to adapt and exacerbate these inequalities (Demetriades and Esplen Citation2008). These aspects will be discussed further later on in the context of our case study.

Overall, we want to understand how gender inequalities impact an activity that is already highly vulnerable, and how all these possible threats interact with these inequalities.

Methodology: a case study of informal market gardening in the DRC

We focus on a specific case in this work: market gardening in Kimwenza, in the south of Kinshasa (located in the semi-rural district of Mont-Ngafula), the capital city of the DRC. In Kinshasa, according to the United Nations Development Program website, the number of informal production units (equivalent of a company) was estimated at 875,500 in 2009. In total, 89.5 per cent of household income in the city was coming from informal activities (UNDP Citation2009). The population has a very low standard of living and a high illiteracy rate. Of all the neighborhoods in Mont-Ngafula, Kimwenza is the only one with renowned tourist sites. There is also a stone quarry, the Lukaya River and some streams, a railway station, cultivatable land, and a young and available workforce. The Kimwenza district also benefits from several poultry farms, most of which belong to Catholic religious congregations and some to expatriates who have had them set them up in the Kimwenza area for several years. Market gardening is the main activity of the majority of the population. Kimwenza is counted among the largest market gardening sites that supply the city of Kinshasa with fresh vegetables. The most cited productions are amaranth, spinach, celery, sweet potato leaves, sorrel, lettuce, parsley, nightshade, tomato, eggplant, and okra. On the site focused on in this study, the staple crops are amaranth and sweet potato leaves, which have a very short growing cycle of about one month. According to the testimony of a market gardener in Kimwenza, amaranth is called Nzela mukuse, which means “shortcut” because it allows one to earn money without waiting too long. Market gardeners in Kinshasa focus more on local crops, except at the Kimwenza sites, where households produce some European crops, in this case lettuce.

For the historical analysis, we rely on data collected during previous works in Kimwenza and on a literature review conducted in libraries in Kinshasa. In order to account for the current situation, the production of data was carried out in two phases at Kimwenza. The first phase was carried out between March and June 2020 and allowed us to understand the realities of the site and its recent evolution through observation and interviews. During this first phase, interviews were conducted with 15 market gardening cooperative leaders,Footnote2 10 resource persons (people who have lived in the sites for decades and former market gardeners who can no longer practice market gardening because of age), the four oldest market gardeners (30–40 years of experience; these people constitute the “memory” of the site), and 25 young market gardeners (fewer than five years of experience, 15 men and 10 women). The second phase, in December 2020 and January 2021, allowed us to go deeper into understanding gender inequalities by interviewing 45 additional women market gardeners. Most of them had completed at least several years of secondary education, were between 40 and 70 years old, and had been market gardening for decades, some before the lootings in the 1990s,Footnote3 which is also important in attesting about the evolution of this activity.

Overall, the topics of these interviews revolved around understanding the familial situations of interviewees, their trajectories and livelihood histories (the difficulty they encounter, how they perceive the threats and opportunities of market gardening), their current activities (in terms of production and commercialization), and collective dynamics (external support, participation in a cooperative, relationships with other market gardeners). This helped us understand their perceptions of their own activity, positive and negative aspects, the threats they encounter, and how they face these threats. It is important to note the great difficulties of any fieldwork on these market garden sites, first because of the general insecurity in Kinshasa.Footnote4 In addition, we also observed a reluctance to participate on the part of market gardeners, even more with women, which translated into a feeling of mistrust and a refusal to continue answering questions. For example, most respondents were afraid to give us their identities and their telephone numbers, and they did not want us to ask about certain topics, such as savings, because they feared being attacked at night. Recording was also not possible because of this complex situation. This climate of tension is, as we shall see, closely linked to the extent of land pressure and the fear of eviction, as well as to the false promises of support that have followed one another. The interviews in this study were possible because relationships had been established through previous field work and helped us overcome this feeling of mistrust.

Our methodology relies on a combination of an inductive and a deductive process (Azungah Citation2018). It is deductive as we follow some leads from the literature, considering the multiple dimensions of threats encountered by women in the case of subsistence market gardening in the DRC. As explored in the previous section, we mainly consider the challenges to accessing different forms of capital (social, human, financial, physical), gender roles, and external threats such as climate change or land tenure institutions. We thus crossed these topics emerging from the literature with the topics discussed with women market gardeners in the field to organize the results. However, the inductive aspect is also important for giving a voice to these women and understanding in a bottom-up process what their perceptions of their own situation are. If giving a voice is a fundamental aspect of qualitative research (Vissandjée et al. Citation2000), it is even more important in the development field and when considering intersectionality. Voices of populations are already overlooked generally in the development field, and this is even more the case when considering women (Dowling and Yap Citation2013; Hankivsky Citation2012).

Results: between empowerment and vulnerability

According to the ILOSTAT Database,Footnote5 the economically active female population is estimated at 48.5 per cent of the total economically active population in 2019. Eighty-six per cent of women are employed in the primary sector; these women are mainly involved in small-scale trade in the agri-food products they grow. In Kinshasa itself, in 2009, 55.3 per cent of informal jobs were occupied by women (UNDP Citation2009). However, in the enterprises created by rural and peri-urban women, their living conditions are of concern for several reasons. We are structuring this section according to the main topics that emerged from the field work and in combination with the literature review.

Coping with patterns of poverty and restructuring the household over time

One of the first important topics that emerged as important from our field work was the evolution of the activity of market gardening. In the recent years of conflict and post-conflict, the informal economy has taken off in a way that was previously unsuspected (Dumbi Citation2017). This happened first because many men lost their formal employment, the economic situation wavering dramatically with the weakening of the Zairian regime, and had a choice between being unemployed or switching to an informal activity and second because it also pushed their wives into the markets and fields to save the material life of the households. Thus, in the agro-pastoral field, women have invested in agriculture, especially in market gardening (Ngoma Binda Citation1999). This is confirmed by the high proportion of households in Kinshasa producing more than 25 kg of vegetables per month, nearly 95 per cent of female-headed households and slightly fewer male-headed households (Kinkela Citation2001).Footnote6 This evolution from the literature is largely confirmed by our field data. Different women market gardeners that we interviewed were occupying other activities, such as teaching or nursing, before the 1990s. Following the conflicts and the poor opportunities for jobs in the country, they had to find alternatives, and market gardening has been a lucrative one according to different women. What is more, they succeeded at first more rapidly than men according to our interviews.

The two years of looting in 1991 and 1993 are a sad memory that forced my husband into unemployment without any benefits, and forced us to become tenants. And the children attended school where the expenses were paid in Belgian francs. Thanks to the savings made from my activity, I was able to take over my household. I covered for my husband in his biological family whenever a problem arose in his family during this critical period. (Interview with Mrs. Binda Victorine)Footnote7

I who speak to you, my husband was a sentinel, I supported him and all my family through the work of rice. I would like to remind you that my husband did not earn much, even when he had problems with bereavements and illnesses in his family, I was the one who covered him. (Interview with Mrs. Wavuma)

I have a degree in accounting, but I am doing market gardening because I have not found a job. My husband does not work, and market gardening is the only activity that supports us. (Interview with anonymous woman market gardener)

However, this tendency is being slowly reversed in the site we investigated. Urban market gardening used to be a typically female activity. Nowadays, because of the increased need for market garden produce and the continuous rise in unemployment, many men have also taken up this activity. According to Mrs. Elysée, “it is difficult to dream of carrying out a large-scale project like in the past.” Older women market gardeners were able to buy land, to build houses, to benefit from this lucrative activity, and they see the evolution of the situation, which younger women market gardeners confirm. The opportunities are not the same nowadays, and even when women market gardeners try to ensure the best opportunities for their own children, the dire situation of the labor market in Kinshasa is leading to many missed chances according to our interviewees. Illustrating this issue, two women market gardeners reported that they had sent their children to university: one had studied hotel management and the other electronics, but as they never found jobs, they invested in market gardening.

Even considering this negative evolution, we observed in our interviews a positive perception of women market gardeners regarding their own activity, outside the difficulties they may encounter. Although it was difficult to obtain income figures from women market gardeners, most of them expressed relative satisfaction. According to many of them, the income from this activity provides food, basic medical care, and schooling for their children, especially those in elementary school.

I built our house, because we owned an empty lot in Kimbanseke, I paid for the education of four children until they graduated. (Interview with Mrs. Binda Victorine)

The activity allows me, first of all, to take care of the schooling of my children from primary school to university for my first son, to take care of the health care of the family, to pay the rent, and to take care of my mother. (Interview with Mrs. Elysée)

I have sent all my children to school and made others travel outside the country. (Interview with Mrs. Wumba Madeleine)

Land tenure

The second topic that came back repeatedly in the discussions in the field were about land tenure insecurity growing over time. Land management remains complex and ambiguous in the DRC. Although the region has theoretically abundant land, the country is faced with high land insecurity resulting from a conflicted and inconsistent policy history (Huggins and Mastaki Citation2019). Access to land is not easy due to a hybrid land tenure law between modern and traditional rules, which leads to multiple confusions and conflicts on the ground (Tawab Citation2010). This complexity is accentuated by the high population density exerting significant pressure on the available land in some provinces of the country, particularly in the East, but also by land exploitation leading to its progressive exhaustion and infertility. Harmful practices lead to low yields and often to the abandonment of lands by farmers. In addition, land grabbing by economic, political, and military elites deprives small farmers of exploitable spaces for their activities and threatens their survival (Peemans Citation2018).

The site of the present study illustrates well this situation, explained in the literature, as some areas of the Kimwenza site are being subdivided and transformed into a residential city. Only the owners remain on the site, and the tenants are being evicted by the new occupants. The military is even becoming involved. On location, women market gardeners have tried to establish a common advocacy to defend their rights, but facing the military’s strength, nothing has been achieved.

Not only the traditional chiefs but also the market gardeners think that there are other, more powerful people involved in this issue. Some market gardening sites throughout the city of Kinshasa are under the surveillance of soldiers whose role is to intimidate market gardeners to prevent them from entering the site. (Interview with the president of the UCOOPMAKIN cooperative)

I am really scared and worried. What would happen to my family if we were hunted? We know that they don’t want to kill us with guns, but they are already killing us indirectly by taking away this land that is our only source of survival (Interview with anonymous woman market gardener).

It was market gardening that made my living. I was driven out of my farm in 2016. Fortunately, one of my friends gave me this small area that I cultivated, but unfortunately, as you can see, they are building a maisonette. This is a sign that the space is sold. I don't know how I will live without this activity. Life has no meaning for me anymore. I am 67 years old. The Kimwenza site is disappearing. I used to make a good living from market gardening but since I was evicted from my former land, my life has become precarious. (Interview with Mrs. Albertine)

The problem is very serious. As you can see, the market garden is being transformed into a residential area. The space that I have been using since 2004 is only shrinking. This site is really disappearing. The president of our cooperative has no power to defend us with the dealers. (Interview with Mrs. Rose)

With this in mind, the vulnerability of market gardening is reinforced by the gender roles and opportunities of women in land management and ownership, as we can observe at the site we investigated. Most women market gardeners have only small plots of land and a few beds (about 10–12 meters long and one meter wide). This can be enough. However, the threats on land tenure are reinforcing their vulnerability in the long term, and expulsions from the land are not announced to the market gardeners. Furthermore, while some are land owners, this is not the case for all of them, and the decision to sell in any case is taken by customary chiefs in the end (customary law is not, according to our interviews and observations, working in favor of women). Additionally, this vulnerability regarding land tenure is combined with a lack of access to resources (credit, equipment) for many women. Despite all the strategies they mobilize to claim their rights, no authority intervenes on their behalf. For example, the women market gardeners wrote a memorandum in February 2010, addressed to the various authorities responsible for land matters. These market gardeners openly denounced the threats to which they are subjected regarding the subdivision and the anarchic plundering of the land they use for their market gardening activities. Unfortunately, their memorandum has remained locked in a drawer since 2010 until today.

Division of roles

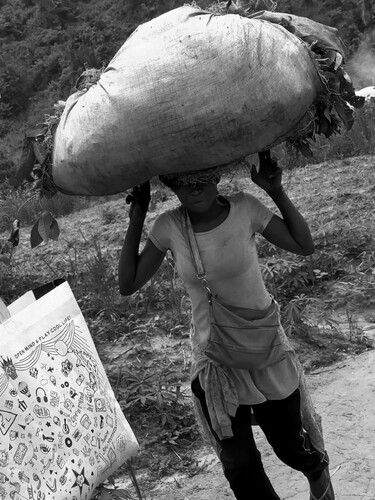

Even if disadvantaged, women are particularly present in agricultural activities, from the activity of farming itself to the commercialization of products, reflecting on what we explained earlier regarding social roles within households. In this space traditionally allocated to them, the women of Kinshasa have been able to develop a sector of production and exchange for their benefit. This strong presence that we observed in the site we investigated is explained at first by lower education levels and economic opportunities for women, and by the fact that this type of activity is generally considered as more feminine, while other types of activities, such as fishing, crafting, or hunting, are considered more masculine activities (Interviews; Bibi Ekomene Citation2020; JICA Citation2017). This has led, in the case of market gardening, to a peculiar organization of the chain of production, reinforced by the low level of infrastructure in Kinshasa, as our field work revealed. Although close to the center of the capital, Kimwenza depends on the state of the roads for its economic integration. The main access road was cut off for a long time due to collapses caused by the rains. It was restored in 2019, improving the accessibility of the area’s market garden produce to urban markets. Even so, the bus or cab stops used by women market gardeners are not close to the production sites, and the almost exclusive method of marketing remains the mamans ya ndunda. These women are the resellers of vegetable products coming from market gardening. As market gardeners struggle to get to marketplaces, as it is requiring time and resources, the women resellers directly come to the production sites to buy the vegetables (see ).

They impose undesirable selling prices by brandishing the pretext of the cost of transport to arrive at the bus stop and sometimes of the use of package carriers. The agreement on price is perceived as very unfavorable by the market gardeners.

We always feel in a weak position in front of the resellers when it comes to setting prices. Given the distance, the fact that they have come to our farms, they take advantage of this to impose the price on us. Faced with the perishable nature of fruits and vegetables, we are forced to give in because we do not have the means to preserve our products and sell them in a timely manner. (Interview with anonymous woman market gardener)

It is a common phenomenon to see women sitting on the side of the road, accompanied by their vegetable parcels, waiting for vehicles for several hours, or even all day. (Interview with anonymous woman market gardener)

Different ways to organize collectively

Another important topic is how to organize collectively. This leads again to the tendency of all market gardeners, men and women, to face similar threats, but women are disadvantaged when having to cope with these threats as they organize differently, confirming findings from the literature (e.g. Molyneux Citation2002). It is first important to understand the growing numbers of formal cooperatives on the site over the years. Cooperative forms of production are not new, and they became a major modality and condition for any project supported by international organizations (e.g. FAO) on the site. Collective action is thus closely linked to external support, linking market gardeners together in formal organizations. To the first four cooperatives that were formed under the impetus of Agrisud’s support,Footnote8 six new cooperatives have been added more recently, within the framework of the Papakin project. These 10 cooperatives are grouped within the Union des Coopératives Maraîchères de Kimwenza (UCMK). The cooperatives were created and supported by the projects, and their operating methods are quite similar, based on a management team, a control committee, and a general assembly. The statutes and internal regulations are similar from one cooperative to another. The same is true for their resources, which are fed by members’ contributions (not without difficulty and delay in payment) and by income from community fields. According to our interviews, despite some limitations,Footnote9 they play an important role in the regulation of the site by becoming involved in conflicts, particularly those related to land boundaries or late payment of rent. Finally, they represent the market gardeners when dealing with the local authorities and the concessionaires. However, the action of cooperatives and the financial support from non-governmental organizations is not totally positive, and it can even lead to additional mistrust and to the division of market gardeners. Different respondents indicate a waste of time, a waste of money, and the fact they are excluded from external support because they refuse to join cooperatives. We also note a certain weakness at the local level in terms of continuity of actions undertaken with the supporting non-governmental organizations after their departure.

In addition, the representation in these formal cooperatives is in favor of men: 95 per cent of the managers in these organizations are men. From what we heard in our interviews, men are more motivated to participate in these types of structures because women are afraid of being used or deceived, and at the same time they feel disrespected as they cannot participate in the decision-making process of the association. When men are going through formal collective actions, women are counting on informal relationships much more to access land and labor.

I have lost my farm, but I am often invited to the homes of market gardening friends to do odd jobs. I don’t earn much, but it allows me to buy food at the end of the day. A market gardener friend of mine gave me two 12X10 beds that I cultivate. I don’t earn much, but it’s something. As he has a large farm, I also work as a day laborer if he needs me (i.e. temporary labor). (Interview with Mrs. Mbumba)

I was earning a good living before being chased away by the concessionaire. Life became very difficult […] Friends who are market gardeners and who need help sometimes hire me to perform certain daily tasks (watering, transplanting …). (Interview with Mrs. Nsimba)

Accentuation of difficulties with climate change

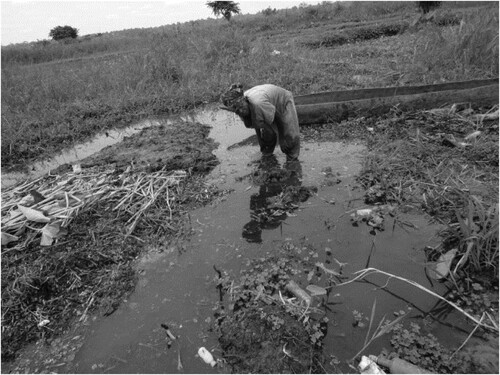

There is a growing interest in the literature in the distributional consequences of climate change, considered an additional threat for women in developing countries. As women have less access to many resources and forms of capital, it reinforces this external threat (Aguilar Revelo Citation2021). We can observe this situation in our site, following our interviews and observations of the daily activities of women during field work. It is already a seasonal activity, leading to many variations, especially because of the ambivalent role of water in market gardening. Watering is facilitated on this site by the proximity of the Lukaya River. This proximity, along with the availability of land, is at the origin of the development of market gardening in Kimwenza. This situation has hardly changed over the years, with the exception of one major difference: the increased risk of flooding of the plots. While this has always been a risk for the site, the older market gardeners have noted an increase in the prevalence of heavy rains, causing the river and other waterways to overflow and reducing the area under cultivation (see ).

In addition, excessive temperatures are causing a considerable drop in production. Some women cope by adapting their production. Some of them grow maize in the beds at distances of more than one meter or at the edges of their fields, especially during the rainy season, because maize is flood-resistant. This makes up for some of the deficits caused by the loss or destruction of crops due to flooding and erosion, resulting in the silting up of cultivated areas. When faced with the problem of water shortages, women market gardeners told us they try to organize themselves at the site level. They build small wells to store water that they use during the dry season. However, due to a lack of financial means, they cannot build anything solid and capable of satisfying all their needs. Just as with the other threats we observed, climate change is impacting all market gardeners on the site. However, women generally have less access to financial or physical capital, and, as we saw, they have smaller plots of land, accentuating the problems of climate change.

Conclusion

What is the impact of being a woman in such a vulnerable activity as market gardening? We first showed that this strongly gendered activity is an important opportunity for women, from the small owners who are able to secure their livelihoods to other groups of women who work as resellers. The perceptions of women regarding their market gardening were positive, as it gives them some autonomy and supports their families in a context where no formal job exists, for them or their husbands. While the entrepreneurial identity has often been associated with men (Masika Citation2017), these women have been able to engage and evolve in this activity to compensate for the lack of jobs for the male members of their families and related to their own roles inside their households. We then observed that market gardeners face a multiplicity of threats. Women and men share the threats of land tenure and the evolution of climate change. However, they must cope in different ways: women have smaller pieces of land and do not have the same resources in terms of organizations, meaning that they count especially on informal relationships. There is a situation of empowerment for women in this activity within the family and larger social spheres. However, women face many socio-political sources of disempowerment and subordination that result in making them more vulnerable. Overall, these threats are at the same time external, such as land tenure, external support, or climate change, and internal, such as gender roles and the capacities women have to cope facing these external threats. Even the initiative of the SENAHUP, supported by the FAO to compensate for a lack of resources, is not enough when considering the situation of women market gardeners in 2020 and 2021, as other interests, mainly the benefits from the land, seem to be prioritized.

The patterns we observed in this very particular context in a neighborhood of Kinshasa echo the situation of many other groups of women in the developing world and urge researchers to pay more attention to overlooked social groups or areas of the world. Further research should be focused on three main points. First and foremost, there should be a focus on the limitations of land tenure and its evolution that does not consider the livelihoods of market gardeners. This is not an easy lead to follow, as it requires consideration of many aspects: formal institutions and formal tenure would not necessarily be the best solution because of the heavy bureaucracy and the important presence of corruption, nor would customary land tenure, being disadvantageous for women. Second, we observed a lack of political power in women market gardeners, reflected in the lack of capacities to organize collectively and of participation in cooperatives to defend their own rights, showing the problems of relying on formal institutions. Even with a specific service dedicated in part to women market gardeners, they are not heard, and other priorities are pushed by public authorities. Finally, climate change is aggravating this limitation, impacting more and more populations in the Global South. Any type of program around adaptation to or mitigation of climate change must consider gender roles. There is a need to continue expanding our collective knowledge about these issues, a need for development, and a need to transition to sustainability while considering the consequences for women.

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Claudine Dumbi Suka

Claudine Dumbi Suka's work has always revolved around helping communities, especially in her home country, the Republic Democratic of Congo. After a PhD in Lille about survival strategies of vulnerable communities, she is now a Professor of Rural Economics at the Catholic University of Congo. Combining agricultural studies and economics, she is working on the multi-dimensional aspects of poverty and resilience in communities, between external pressures, gender issues and environmental constraints.

Juliette Alenda-Demoutiez

Juliette Alenda-Demoutiez completed her PhD in France in 2016, after which she served as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Amsterdam. She is now an Assistant Professor in the chair of economic theory and policy at the Radboud University’s department of Economics. Her areas of expertise include environmental sustainability, governance, institutions, macroeconomic indicators, welfare and social economy, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Notes

1 Intersectionality is a framework dedicated to the understanding of the interconnected nature of social categorizations, creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.

2 Many cooperatives exist in the city of Kinshasa as external development programs supported the creation of many of them. However, a minority of market gardeners join these cooperatives, mainly because of the price of becoming a member. Some very small cooperatives (with fewer than 100 members) co-exist with larger ones (more than 1,000 members). The details for the site of Kimwenza are explained later in this section.

3 The 1990s were a very tensed period, combining conflicts, massacres, and, in 1991, unpaid soldiers engaged in serious looting in Kinshasa as well as in several other cities in the country.

4 One of the authors got threatened while conducting field work, and street crimes are increasingly common.

5 Available at https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

6 In Kinshasa, almost half of the households are female-headed (UNDP Citation2009).

7 As all the interviews were conducted in French, all quotes are translated by the authors.

8 Since 2005, AGRISUD International has been implementing the Kinshasa Peri-Urban Agricultural Development Support Program (PADAP Kinshasa). This program, conducted until the end of 2008 in the Kimwenza area, combined two components: market gardening in the Lukaya Valley and market gardening in Kimwenza. These two components were supported, respectively, by the French Cooperation and the European Union. They were co-financed by AGRISUD, the PHITRUST Foundation, the Caisses d'Epargne Aquitaine Poitou Charente (CEAPC), and the association Toit de la Grande Arche. Two main partners were associated with the action: FOLECO (Federation of Lay NGOs with an Economic Character in Congo) and AGRIDEV (non-governmental organization in Congo Brazzaville).

9 As for the security of the exploited plots, the cooperative can do nothing but negotiate a notice or a payment for the value of the crops already in place before the eviction.

References

- Adekanye, Tomilayo. 1984. “Women in Agriculture in Nigeria: Problems and Policies for Development.” Women’s Studies International Forum 7 (6): 423–431. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(84)90013-X.

- Aguilar Revelo, Lorena. 2021. Gender Equality in the Midst of Climate Change: What Can the Region’s Machineries for the Advancement of Women Do? Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

- Azungah, Theophilus. 2018. “Qualitative Research: Deductive and Inductive Approaches to Data Analysis.” Qualitative Research Journal 18 (4): 383–400. doi:10.1108/qrj-d-18-00035.

- Bibi Ekomene, Genèse. 2020. “La promotion de l’entrepreneuriat féminin par le microcrédit en République Démocratique du Congo.” KAS African Law Study Library 7 (2): 350–361. doi:10.5771/2363-6262-2020-2-350.

- Branisa, Boris, Stephan Klasen, and Maria Ziegler. 2013. “Gender Inequality in Social Institutions and Gendered Development Outcomes.” World Development 45: 252–268. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.12.003.

- CAVTK. 2006. Amélioration de la sécurité alimentaire de Kinshasa. Kinshasa: Centre Agronomique et vétérinaire tropical de Kinshasa.

- Chen, Martha, Joann Vanek, and James Heintz. 2006. “Informality, Gender and Poverty: A Global Picture.” Economic and Political Weekly 41 (21): 2131–2139. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4418269.

- Demetriades, Justina, and Emily Esplen. 2008. “The Gender Dimensions of Poverty and Climate Change Adaptation.” IDS Bulletin 39 (4): 24–31. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2008.tb00473.x.

- Doucouré, Djibrill, and André Fleury. 2004. “La place de l’agriculture urbaine dans les dispositifs institutionnels et la planification.” In Développement durable de l’agriculture urbaine en Afrique francophone, edited by Olanrewaju Smith, Paule Moustier, Luc Mougeot, and Abdou Fall, 45–78. Ottawa: CIRAD.

- Dowling, John, and Chin-Fang Yap. 2013. Happiness and Poverty in Developing Countries a Global Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Dumbi, Claudine. 2017. Quel avenir pour les ménages maraichers en République Démocratique du Congo ? Paris: L’Harmattan.

- FAO. 1999. Agriculture urbaine et péri-urbaine. Rome: FAO.

- Ghorayshi, Parvin. 1997. “Women and Social Change: Towards Understanding Gender Relations in Rural Iran.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études Du Développement 18 (1): 71–92. doi:10.1080/02255189.1997.9669695.

- Hankivsky, Olena, ed. 2012. An Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Framework. Burnaby: Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University.

- Huggins, Chris, and Christol Paluku Mastaki. 2019. “The Political Economy of Land Law and Policy Reform in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An Institutional Bricolage Approach.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne D’études Du Développement, 1–19. doi:10.1080/02255189.2019.1683519.

- IPC. 2019. Analyse IPC de l’insécurité alimentaire aigüe juillet 2019-mai 2020, 17e cycle. Online Report. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/analyse-ipc-de-lins-curit-alimentaire-aigu-juillet-2019-mai-2020-0.

- JICA. 2017. Country Gender Profile Democratic Republic of the Congo. Online Report. https://www.jica.go.jp/english/our_work/thematic_issues/gender/background/c8h0vm0000anjqj6-att/drc_2017.pdf.

- Kakota, Tasokwa, Dickson Nyariki, David Mkwambisi, and Wambi Kogi-Makau. 2011. “Gender Vulnerability to Climate Variability and Household Food Insecurity.” Climate and Development 3 (4): 298–309. doi:10.1080/17565529.2011.627419.

- Kinkela, Charles. 2001. “L’apport du maraîchage dans la lutte contre l’insécurité alimentaire à Kinshasa.” In Sécurité alimentaire au Congo-Kinshasa, production, consommation et survie, edited by Kankonde Mukadi and Eric Tollens, 225–285. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Kuyengila, Ernest, and Frans van Hoof. 2010. Un soutien plus efficace à l’agriculture par davantage de complémentarité et de synergie entre les Organisations Paysannes et les autres acteurs. Middelbeers: Advisors For Africa Farmers Organisation.

- Lallau, Benoît, and Claudine Dumbi. 2007. “Un maraîchage de survie peut-il être durable ? Quelques enseignements de la situation kinoise.” Cahiers Agricultures 16 (6): 485–490. doi:10.1684/agr.2007.0145.

- Larson, Anne, David Solis, Amy Duchelle, Stibnitia Atmadja, Ida Resosudarmo, Therese Dokken, and Komalasari Mella. 2018. “Gender Lessons for Climate Initiatives: A Comparative Study of REDD+ Impacts on Subjective Wellbeing.” World Development 108: 86–102. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.027.

- Lowndes, Vivien. 2004. “Getting on or Getting By? Women, Social Capital and Political Participation.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 6 (1): 45–64. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856x.2004.00126.x.

- Masika, Rachel. 2017. “Mobile Phones and Entrepreneurial Identity Negotiation by Urban Female Street Traders in Uganda.” Gender, Work & Organization 24 (6): 610–627. doi:10.1111/gwao.12184.

- Mianda, Gertrude. 2000. Femmes africaines et pouvoir (Zaïre, Histoire et Société). Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Minengu, Jean de Dieu, Ikonso Mwengi, and Mawikiya Maleke. 2018. “Agriculture familiale dans les zones péri-urbaines de Kinshasa : analyse, enjeux et perspectives (synthèse bibliographique).” Revue Africaine d’Environnement et d’Agriculture 1 (1): 60–69. http://rafea-congo.com/admin/pdfFile/RAFEA-Article-Minengu-et-al-2018-ok.pdf.

- Molyneux, Maxine. 2002. “Gender and the Silences of Social Capital: Lessons from Latin America.” Development and Change 33 (2): 167–188. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00246.

- Moustier, Paule. 1998. “Définitions et contours de l’agriculture périurbaine en Afrique sub-saharienne.” In Agriculture périurbaine en Afrique subsaharienne : actes de l’atelier international du 20 au 24 avril 1998, edited by Paule Moustier, Alain Mbaye, Hubert De Bon, Hubert Guérin, and Jacques Pagès, 29–42. Montpellier: CIRAD.

- Nahmias, Paula, and Yvon le Caro. 2012. “Pour une définition de l’agriculture urbaine : réciprocité fonctionnelle et diversité des formes spatiales.” Urban environment 6. http://journals.openedition.org/eue/437.

- Nelson, Valerie, and Tanya Stathers. 2009. “Resilience, Power, Culture, and Climate: A Case Study from Semi-Arid Tanzania, and New Research Directions.” Gender and Development 17 (1): 81–94. doi:10.1080/13552070802696946.

- Ngoma Binda, Phambu. 1999. Rôle de la femme et de la famille dans le développement. Argument pour la justice et l’égalité entre les sexes. Kinshasa: Institut de formation et d’études politiques.

- Peemans, Jean-Philippe. 2018. “Agricultures, ruralités, paysanneries : réflexions et questions pour une économie politique critique des discours dominants sur le développement.” Mondes en développement n° 182 (182): 21–48. doi:10.3917/med.182.0021.

- Perez, Carlos, E. M. Jones, Patricia Kristjanson, Laura Cramer, Philipp Thornton, Wiebke Förch, and Carlos Barahona. 2014. “How Resilient are Farming Households and Communities to a Changing Climate in Africa? A Gender-Based Perspective” Global Environmental Change 34: 95–107. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.003.

- Peterman, Amber, Julia Behrman, and Agnes Quisumbing. 2011. A Review of Empirical Evidence on Gender Differences in Non-Land Agricultural Inputs, Technology, and Services in Developing Countries. Working Paper, ESA. http://www.fao.org/3/am316e/am316e.pdf.

- Rezelman, Abigail. 2009. Agriculture urbaine : réflexion sur l ‘alimentation dans les villes durables. Working Paper. [Online]. www.bretagneprospective.org/diawel/component/option … /gid, 77/.

- Spring, Anita. 2009. “African Women in the Entrepreneurial Landscape: Reconsidering the Formal and Informal Sectors.” Journal of African Business 10 (1): 11–30. doi:10.1080/15228910802701296.

- Tawab, Garry. 2010. Code forestier congolais et ses mesures d’application. Louvain-La-Neuve: Academia-Bruylant.

- UNDP. 2009. Pauvreté et conditions de vie des ménages, Province de Kinshasa. UNDP RDC. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/dem_rep_congo/docs/povred/UNDP-CD-Profil-Ville-Kinshasa.pdf.

- Vissandjée, Bilkis, Shelley Abdool, Sophie Dupéré, and Shree Mulay. 2000. “An Account of Participatory Research with Women in Rural Gujarat.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études Du Développement 21 (Suppl. 1): 543–564. doi:10.1080/02255189.2000.9669930.

- World Bank. 2017. WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country: A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Washington, DC: WASH Poverty Diagnostic Series. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/27320.