ABSTRACT

This article applies historical research with cross-disciplinary analysis to investigate some “lost” stories of Canadian engagement in China’s first multilateral development-aid project in 1981–1988. Policy reflection on bilateral relations can benefit from expanding recognition of some early Canadian experiences marginally examined in this significant case of Development Diplomacy within a Chinese context. Almost forgotten, these collaboration practices yet started when a small team of Canadian agricultural specialists provided three years of consulting service to this Northern Pasture and Livestock Development project co-funded by the IFAD. Our archival inquiries create refreshing lessons for international development-aid initiatives that advocate community-based, multiple-stakeholders collaboration for restoring bilateral relations.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article prend une approche interdisciplinaire de la recherche historique afin d’analyser certaines histoires « oubliées » de la participation du Canada dans le premier projet multilatéral chinois d’aide au développement en 1981–1988. Reconnaître les premières expériences Canadiennes telles qu’elles ont été vécues en marge de cet épisode important de la diplomatie du développement dans un contexte chinois peut informer la réflexion politique sur les relations bilatérales. Presque oubliées, ces pratiques de collaboration ont néanmoins débuté avec la contribution de trois ans de services de consultation par une équipe de spécialistes canadiens à ce projet de développement des pâturages et de l’élevage du bétail du Nord, co-fondé par l’IFAD. Nos recherches en archives nous permettent d’offrir de nouvelles perspectives pour les initiatives internationales d’aide au développement qui promeuvent des collaborations entre plusieurs partis, et effectuées au niveau communautaire, afin de rétablir des relations bilatérales.

Introduction

China received its first development-aid loan from the United Nations International Fund of Agricultural Development (IFAD) in the early 1980s,Footnote1 a Northern Pasture and Livestock Development Project (NPLDP) that has aimed to repair China’s northern grassland landscape and provide poverty relief in local communities. In 1982–1984, the IFAD supported three years of technical consultation and field investigation delivered by a Canadian consulting company, Agrodev Canada, based in Ottawa, Canada.Footnote2 This firm recruited agricultural specialists and rural development experts from some well-known universities, including McGill, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and others. Canadian experts visited dozens of project sites, all suffering from environmental degradation due to poor agricultural practices, in three provinces, eight counties, and 31 townships (villages) across Northern China. This NPLDP project was built on a Canadian tradition of engaging in China, which extends back to the 1950s with development-aid projects run by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). The significance of Canada’s contribution to Chinese agricultural development at this stage has not been well addressed in the literature.

This NPLDP case is consistent with the concept of Development Diplomacy, which represents an alternative to “coercive diplomacy” deployed in the Cold War eras and offers a more peaceful solution to many local or global interest conflicts (Azar and Moon Citation1986). Assessment of this early example of Development Diplomacy provides an opportunity to reflect on international development aid practices and offers insights to minimize the impacts of geopolitical risks and materialize the principle of engaging diverse stakeholders. Building on project notes offered by contributors to this study, and cross-referenced with the available records from IFAD, this study summarizes Canadian lessons in applying Development Diplomacy in early-1980s China, and supports a renewed narrative to advocate for community-based collaborations across national borders.

Aligned with the notion of Historical Diplomacy (Butterfield Citation1966; Sharp Citation2003), the exploration of Development Diplomacy also sheds light on the task of (re-)normalizing China-Canada relations. Ideological-political disputes between the two countries have escalated since the 1990s; in recent decades, Canada has drifted from its early engagement policies. China-Canada relations deteriorated rapidly with a series of controversial events beginning in 2019 with the Canada’s “staged” arrest of the Huawei CFO Ms. Meng Wanzhou followed quickly by China’s retaliation by “illegally” detaining the two Michaels (Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor) for nearly three years. Even after the resolution of these incidents, relations remained strained; Ottawa recently stated that “eyes are wide open when it comes to [re-]normalizing its relationship with China,” while Beijing urged the latter to adopt a more “rational and pragmatic” policy toward China.Footnote3 One pathway for the restoration of this bilateral relation is renewed engagement with a broader and more diverse group of stakeholders,Footnote4 and the praxis of international development aid policies offers substantive opportunity to engage local citizens with global commitment and multilateral solutions. This article reminds readers that historical ignorance limits the extensible applications of Development Diplomacy to fight against inequity and poverty. To resist clichéd post-colonial rhetoric with non-binary narratives, it is up to citizens (and not just policy-makers) to become educated and to remain critical of political populism.

Newly-discovered archival evidence from this NPLDP case study contributes to the academic debates within the overarching theoretical framework of Public or People’s Diplomacy (PD). One can define diplomacy as the institutions and processes deployed by various actors to represent themselves or their interests in global societies. PD advocates trust-building and pluralizing initiatives more by non-state actors or civil society members than classic diplomacy (Huijgh Citation2019). New PD forms, including Development Diplomacy and History Diplomacy, can open more potential with a holistic outlook and engage higher civil participation, deeper cultural dialogue, and better national branding (Aronczyk Citation2013). Relevant discourse, benefiting from multidisciplinary discussions, is oft-connected to another umbrella term, “soft power,” coined by Nye (Citation2008, Citation2019). Coupled with PD, the concept of soft power has gained wide acceptance by Chinese governmental agencies and scholars (Wang Citation2008; Vlassis Citation2016). This receptivity feature would demand mutual cultural respect and intellectual collaborations against essentializing political disputes. Refreshing such memories from those NPLDP stories helps correct some misconceptions entrenched in binary or “us-vs-others” narratives yet detrimental to transnational development aid collaboration. Those pro-antagonism arguments are typically connected to “othering” rhetoric, while “identity politics” either intentionally or obliviously feeds on misinformation with moral assertion and historical ignorance.

Early Canadian presence in the NPLDP case

This paper interprets the NPLDP case as a precursor case for partnership initiatives in Canada−China Development Diplomacy. Based on recently located archival records, including a set of unpublished reports and project sheet copies from Agrodev, this section first highlights the highly technological and culturally empathic languages used by the Canadian experts involved in the project. The engagement of these experts, funded within the multilateral framework between the Chinese governments and IFAD, helped integrate long-term goals for sustainable agricultural development and rural poverty reduction. IFAD has celebrated this long-term partnership, citing: “In 1981, IFAD became one of the first international donors to finance operations in China” and proudly labeled the agency as “ … the only one of China's development partners dedicated exclusively to reducing poverty and increasing food and nutrition security in rural areas.”Footnote5 Back then, Beijing presented strong willingness to embrace UN technical assistance after decades of exclusion in the Cold War, particularly after the Korea War.

Yet incomprehensibly, the role of Canadian experts in this NPLDP project has not been recognized, and the collective knowledge that the participants in this project amassed between 1981 and 1984 was not captured or built upon. In recent years, many of these experts have passed away; the survivors are all in their 80s and 90s.Footnote6 Preliminary archival inquiries showed that public reports on the success of this first international agricultural development-aid project in China had NEVER publically mentioned any Canadian participation in that success. Even the names of experts who had participated were difficult to find. One member, Dr. Eugene Donefer, was identified early and provided a number of materials and personnel contacts. Other experts were identified and located using the snowball method and building on each new contact’s knowledge. According to Donefer, “the largest handicap to identify [the experts who had participated] was the unavailability of the report of the Canadian organization, i.e. Agrodev, contracted with the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture.”Footnote7 Donefer felt that about 13 individual experts were involved from a variety of institutions or departments, but this number was only an estimate.

A small number of individuals could be identified from materials published by McGill University’s Animal Science Department, located at Macdonald Campus. As the host institute of four Agrodev consultants, this department summarized its involvement in NPLDP in the following quote from 1984:

During the summer of 1982, four MacDonald faculty members (B. Baker, E. Donefer, J. Moxley, and P. Jutras) were part of a Canadian team involved in an agricultural development project in the People's Republic of China. The Northern Pasture and Livestock Development project is a scheme of the Chinese Government for increasing production of milk, beef, and sheep in the northeast part of the country, which includes the Provinces of Hebei, Heilongjiang and Inner Mongolia. … Due to a long period of minimum contact with outsiders, during which time the Chinese had concentrated on building up their capacities for “self-reliance,” there was much interest expressed on how we do things in Canada. Since the area in North China had a similar climate to Canada, with a short growing season and relatively dry conditions, many of the Canadian livestock and forage stems could be related to their conditions.Footnote8

For a 3-year period (1982-’84), Department staff members (E. Donefer, J. Moxley, and later B. Downey) were selected as part of a Canadian team to consult with agencies of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on livestock production in the North- East Provinces (including Inner Mongolia). This participation involved travel to China over periods of several weeks each year. This project, funded from United Nations sources, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development ([IFAD]), was the first Chinese program involving foreign consultants.Footnote9

This project is the first IFAD loan project after China joined the Fund [IFAD] and also the first large-scale agricultural project funded by foreign investment in China. Commenced in 198 l, the project underwent an interim adjustment three years later and was completed in 1988. … This project was carried out in the arid and semi-arid prairies in northern China which cover eight counties and 31 townships (villages) in Heilongjiang, Hebei and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region about 1426 million hectares.Footnote10

About half of these consultant members traveled to China more than once. On average, each trip took two or three months in a few cases, up to six months.Footnote12 Agrodev offered a total of 20 positions to 23 experts; each of these experts was recruited by the Agrodev, and in total these consultants made 41 personnel/trips to China in three years. There were 20 individual personnel involved in trips in 1982, 14 in 1983, and 7 in 1984. L. Pelzer and D. Williams served as Canadian Project Managers in 1982–1984. A couple of consultants, including E. Donefer (Animal Nutrition expert) and T. Lee (Fencing/Beef Management specialist) made all three annual field trips. Some specialists only made one trip, probably based on the expertise that they brought; there were only one personnel/trip for Crop Preservation, Seed Processing, and Slaughter & Meat Processing.

Personnel change from year to year may have caused some concerns to the host agency in China – the General Bureau of Animal Husbandry (GBAH). This can be seen in the excerpts from a “Note on Continuity” attached below. In his letter of invitation to tender (October 15, 1981), the Deputy Director of GBAH wrote, quoting:

It would be appreciated that each individual proposed would be available for the entire assignment as indicated in terms of reference; (sic) such continuity of service is essential.

Of the 23 positions listed above, 11 were appointments for one season only. … Naturally, they were filled by one individual only. Of the 12 appoints of two or more seasons, seven were two-year appointments, and five were three-year appointments. … Footnote13

The final Agrodev report provided a detailed summary of fieldwork assignments by location, as 24 sub-project areas were identified and consultants designated to each. Not all sub-project sites were visited each year. Interestingly, while the report states that “sub-project areas will not be changed for the duration of the project,” it is clear that the Canadian consultants did exercise flexibility in subsequent years:

In 1983, the number of sub-project areas grew to 30, including 10 new sub-projects. Four 1982 sub-project areas ceased to be part of the project. Of the 30 sub-project areas, 14 were visited by the consultants in 1982. In 1983, six of 30 sub-project areas were visited, while in 1982, five of the 30 were visited.Footnote14

It is clear that Canadian experts – if not the government of Canada – had long-term plans for the NPDLP project. According to the Agrodev report, the Canadian experts stressed that “[T]he project, therefore, has been conceived in the perspective of a much longer-term development of, say, 15–20 years, so as to enable various measures to stabilize the ecology of the range lands,” while “ … the task of changing existing practices has to be taken up with utmost caution,” and “the pastoral communities have been practising animal husbandry over a long period of time, both as an economic avocation and a social way of life.”Footnote16 By 1986, two years after the Canadian consulting work had finished and also two years before the NPDLP project completed, China was listed in second position on the core category list of development aid countries by CIDA.Footnote17

The NPDLP project is an example of how Canada was utilizing Development Diplomacy at an early stage to augment traditional diplomacy (Potter Citation2003, Citation2009), and represents a substantive engagement over both an extended timeframe (3 years) and a wide geographic area within China. The kind of development aid work that the NPDLP project undertook aligns well with current strategies on international development; for example, Muirhead (Citation2009) has advised that Canadian international development policies in China should focus on investments in five specific areas: 1. China’s impoverished areas, especially among those of its ethnic minorities; 2. Environmental projects; 3. Community-based natural resource management; 4. Governance and legal system reform; 5. Areas that may yield trade potential for Canadian business. The NPDLP project meets the first three criteria well, and indirectly supports action in areas 4 and 5.

Insufficient public recognition afterwards

A narrative describing Canada’s role in the NPDLP case is mostly absent in the accessible literature. In the IFAD open database, the NPLDP profile is condensed to a few short lines: “Project Status: Closed; Approval Date: April 22, 1981; Duration: 1981–1988; Sector: Livestock; Total Project Cost: US$ 61.68 million; IFAD Financing: US$ 32.48 million; Co-financiers (Domestic): National Government US$ 29.2 million; Financing terms: Highly Concessional; and Project ID: 1100000062.” Interim and/or final reports, generally included in other IFAD cases archived, are not present. Unfortunately, not one single line of acknowledgement is publically available to mention Canadian contribution in this case. After several inquiries for the NPLDP archive, the IFAD China Office confirmed it as “the first IFAD loan project for China, effective from July 1981 and completed in early 1989.” Yet unfortunately, they go on to state that “the IFAD does not have many records of this project maintained in the IFAD archive.” The IFAD Beijing office kindly relayed the only piece of project information retrieved from its internal archive: “During the initial three years, the Canadian consulting firm, Agrodev, sent some 30 consultants to the project areas between L982 and 1984, for a total of 94.5 man-months, in the activities relating to Design and Analysis, Pasture and Fodder Improvement, Livestock, Irrigation, Machinery and Processing Monitoring & Evaluation.” The records recovered from remaining experts confirm this short description, which may be the only formal international record of Canada’s role in this early project.Footnote18

A literature review of published material from the 1980s to the present was conducted to understand how the NPLDP project was understood by others. Only one peer-reviewed paper was found to address this project: two Australian scholars, Brown and Longworth (Citation1992), carried out a policy examination of this study case. They accredited their work to close collaboration with their Chinese colleagues at the Institute of Agricultural Economics of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Institute of Rural Development of the Chinese Academy of Social Science.Footnote19 Their paper was published in 1992 and provides the following summary:

Multilateral aid agencies aim to fund projects which will contribute to sustained development in the Third World. The pastoral areas of China present major challenges in relation to sustainable development. A major multilateral aid project designed to meet these challenges, the IFAD North China Pasture and Animal Development project, is described and evaluated using new survey data. … . The case study also illustrates the point that financial arrangements adopted by agencies such as IFAD can impose potentially serious unintended burdens on the recipient country.Footnote20

A few other authors have touched on the NPLDP project without acknowledging the role that Canada has played. Work by Sheehy, Jeffrey, and Brant (Citation2006) was carried out at Yihenoer Sumu commune; this project was funded by the Canada−China Sustainable Agriculture Development Project in 2003. Interestingly, Yihenoer Sumu also appeared in the IFAD-Agrodev records.Footnote21 In the local demographic profile, Yihenoer Sumu ceased to exist in 2006 after merging with two nearby Communes; on the local map, only a lake keeps the name Yihenoer, reflecting the geographical legacy.Footnote22 A conference proceeding (Sheehy, Jeffrey, and Brant Citation2006) describing this work at Yihenoer Sumu mentions an earlier pastoral development project in the 1980s: The senior author worked in Yihenoer from 1985 to 1987, studying the grazing resources of the area and developing a range management plan for the Yihenoer Pilot Demonstration Area (YPDA). The YPDA included herders and the land area of three livestock production teams. It was established in 1985 by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Northern Pasture Project, an ongoing project in Inner Mongolia between 1981 and 1989, to demonstrate modern principles and techniques of rangeland and livestock management.Footnote23

As seen in the quote above, the paper mentioned a “Northern Pasture Project” in referencing the NPLDP. It is clear that Sheehy, as senior author, was active in the same place very shortly after Canadian researchers had been working in the region. The fact that Sheehy reports nothing of Canadian involvement after 1985 suggests that members of the Canadian team would not have returned to these sub-project sites after the consulting team formally dissolved in 1984.Footnote24

The earliest evidence of western intervention in China’s agricultural sector was found with relation to the dairy industry, and occurred shortly after China re-opened its door to the world in the late-1970s (Gorissen and Vermeer Citation1985).Footnote25 Given this context, it is clear that Canadian agricultural experts taking part in the NPLDP project were among the earliest western experts and thus some of the earliest participants in Development Diplomacy in China, along with countries like Australia. An important question is, why wasn’t Canada able to keep up this role? Some policy analysts have argued that Ottawa failed to recalibrate its Chinese policy in the post-1990s diplomatic shifts (Chin Citation2009). It does seem clear that an opportunity was missed, as these experts were not able to capitalize on the lessons they learned after the initial project was completed. Hanlon (Citation2012) has recommended a talent-leveraging strategy for sustainable community development with public or cultural diplomacy with Asia; this type of strategy, employed with the experts that participated in the NPLDP project, could have yielded greater dividends.

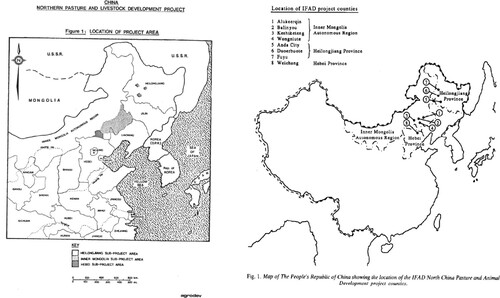

An example of how expert knowledge informs understanding of the political situation, and can help contribute to Development Diplomacy. Two maps of project sites, by the Canadian report provided by Agrodev (left) and the Brown and Longworth paper (right), are attached below. The 1984 Agrodev map is more detailed, providing provincial borders with sub-project sites denoted; on the 1992 Brown and Longworth paper, national borders with the former USSR and Mongolia are blank, and far fewer details are provided. One would expect that the latter focus on national policy analysis more on macroeconomic levels and extensible multilateral aid lessons. In comparison, the Canadian specialists attended more on how to adapt technic solutions locally for specific regions and the maps reflects those regions. For instance, Donefer was impressed that many local farms were familiar with the Russian rangeland techniques and European cattle breeds, evidently introduced in the 1950s-60s ().

In January 1990, an official report jointly issued by five ministries/agencies of the Chinese central government proclaimed the success of this NPLDP case as the first international multilateral development-aid project.Footnote26 This official report accredited the IFAD funding and valuable aid of UN specialists, presumably including the Canadian consultants recruited by the Agrodev. Those five state agencies included the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Finance, the Central Planning Committee, the National Audit Office, and the Agriculture Bank of China. Many project advice mentioned in this report looks consistent with the Agrodev report. For instance, the report spoke highly of these mid-stage adjustments on technology adaption and sub-project site elections started after 1983, most of which sound consistent with the Agrodev records. Nonetheless, not a word has explicitly addressed Canadian contribution in this closing report approved by Chinese authorities.

More indirect testimony for this information gap comes from some recent events noted in this historical inquiry. After nearly 40 years, the areas that once were home to NPLDP sub-projects now host China's primary regional dairy producers. Most Chinese dairy companies have their ranches based in those areas. In the mid-1980s, an UN-funded aid loan extension project initiated a brand-new dairy factory at Qiqihar (NenJiang), Heilongjiang, one of the NPLDP sub-project sites pre-selected by Canadian consultants.Footnote27 This factory was operated by the Feihe Company, which started as a county-owned diary collective. Feihe was one of many local beneficiaries of the NPLDP’s pioneering work and indeed it is likely that the NPLDP project set the scene for the expansion that would follow. The loans the company received led to Feihe experiencing spectacular growth along with many domestic competitors. In the present day, with an insatiable demand for milk in China, these dairy companies are involved in overseas expansion. In 2017, a dairy formula powder plant operated by the Feihe Company opened in Kingston, Ontario. Its venture project in Canada committed a total investment of $225 million Canadian dollars, in the hope of benefiting from the abundant local supply of goat/cow milk and exporting high-end dairy product back to China.Footnote28 Its Kingston plant processed its fast-track construction from 2018 and started operation in 2019–2020.

Continuing IFAD progress and development diplomacy

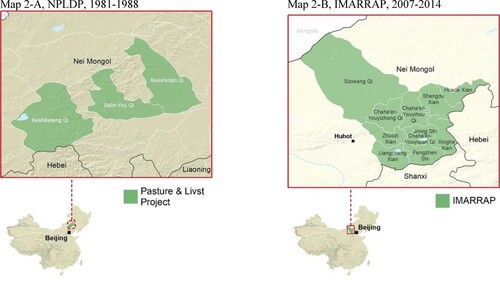

Some multilateral development-aid programs remained active in China throughout the late 1980s, 1990s, and into the 2000s. Brown and Longworth (Citation1992) noted that the majority of IFAD funding at that time flowed to projects in the IMAR – i.e. the very regions that the Canadian-led NPLDP concentrated on. Some countries (like Australia) have been very active to the present day in pastoral development projects in the IMAR and Mongolia.Footnote29 As late as 2007, a major IFAD project was announced (total project cost, US$70.92 million of which IFAD provided US$30 million) within this region; the community-based nature of this international development-aid project serves as a spiritual successor to NPLDP operations carried out in the 1980s ().Footnote30

Compared to the NPLDP case closed in 1988, the lately-finished development-aid project at IMAR has less fragmented project sites, yet almost the same financing size and terms. IFAD funding (US$30 million) awarded in 2007 is very similar to the US$32.48 million awarded in 1981, although the proportion of international aid in total project funding has fallen from 52.7% (1981) to 42.3% (2007). This change means that domestic financing, including those from various national governments, local beneficiaries, and other sources, has become a leading source of these multilateral development-aid cases.

This case study is a good example of the constructive effect of shifting from classic diplomacy to create more venues for others, via engaging diverse stakeholders and citizen participants in addition to state agencies, through mechanisms such as Development Diplomacy (Young and Henders Citation2012). Back in the early 1960s, when Canada embarked on large-scale wheat exports to China, US opposition highlighted some of the challenges presented by complicated alliances that underscore classic diplomacy approaches (Stevenson and Donaghy Citation2009; Evans and Frolic Citation1991). By contrast, the NPLDP case of the early 1980s helps foster “people-to-people” links, in contrast with the “leader-driven” Cold-War politics, which restricted collaborations with China (Nossal and Sarson Citation2014). Despite the presence of politically-critical voices against China, a Development Diplomacy approach based on inclusive engagement can help resolve policy dilemmas.

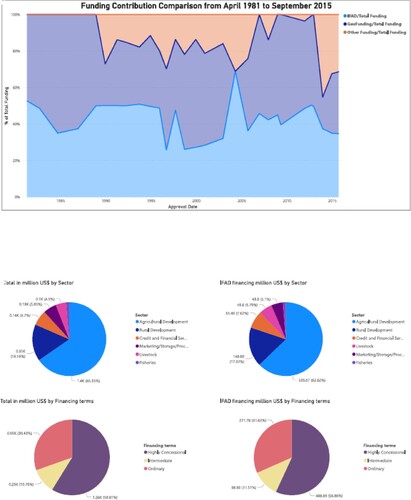

Unfortunately, Canada has not always applied this approach. After the chaotic 1989 Tiananmen tragedy, Canadian state agencies swiftly postponed five development-aid projects worth C$61 million for China.Footnote31 Almost coincidently, Australia quickly became the largest beef exporter to China. International multilateral development aid to China resumed in the 1990s; the IFAD database has registered a total of 33 projects in 1981–2021 China, 29 of which are complete and four of which are still in progress. The total project investment is US$ 2.98 billion, of which IFAD financing has contributed US$1.15 billion. These projects have benefited 4,589,181 households across China.Footnote32 A summary of these projects is provided in .

Figure 3. The IFAD-funded projects in China, 1981–2020. Data source: IFAD-China projects, 1981–2020, with a total of 29 closed projects by 2020.

The figures show that 29 closed IFAD projects have kept engaging local communities with extensive scales. This evidence confirms Canadian legacies of Development Diplomacy in the NPLDP case in the 1980s. Canadian specialists, mainly from technical support and animal science, expressed more interest in investing in new technologies, a different focus than some other countries which were more concerned with debt.Footnote33 Canadian experts did not downplay policy or institution reforms, which they had less explicitly highlighted than the Australian scholars. In the Agrodev consulting report, the section on technical recommendations dominated the discussion, while non-technical and management recommendations made up a much smaller component.Footnote34

There are strong connections between Development Diplomacy and Education Diplomacy which can be seen in this project. Beginning in the 1980s, a long list of Canada−China higher education partnership programs have been gradually established. These programs delivered great success and offered a pathway for cultural learning and soft diplomacy (Hayhoe, Pan, and Zha Citation2013, Citation2016). Most university-level partnership programs should be credited to the joint initiative by Chinese state agencies and the CIDA (Zha Citation2011), and many took advantage of Canadian partner institutions already active through programs like the NPLDP case – such as McGill University. As one major contributor and research collaborator to this case study, Donefer stated, “China collaborations were the result of my last ten years at McGill before my retirement when I was Director of McGill International [1985–1995], an office in the Graduate Faculty. As a result, McGill had many China projects.” Dr. Martin Singer at Concordia University notes that many China-Canada academic partnership programs go back to the early 1980s, and that up to 30 Canadian universities had active partnership by 1995 (Lan Citation2020).

Later studies by Sinclair, Blachford, and Pickard (Citation2015), Sinclair and Blachford (Citation2018), Meehan and Webster (Citation2013), and Sinclair, Blachford, and Magnan (Citation2016) examined a range of farming collaboration projects, endorsed by local partners across the national borders and funded by organizations including CIDA.Footnote35 This work highlighted the power of continued development aid projects to further Development Diplomacy and to strengthen international relations through the power of collaboration, discussion, and development. In the early 2020s, bilateral trade restrictions were abruptly imposed by China due to an escalating tensions connected mainly with geopolitical controversies, once again highlighting the need for multiple diplomatic pathways. Human rights have been the main triggering issue, both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This pandemic has created a great chance to spread legitimacy narratives of PD (Manfredi-Sánchez Citation2022), including Development Diplomacy. The NPLDP project, with some shared Canadian stories rediscovered after many years, has important historical and policy lessons. Reflections on Canada−China development collaborations and “untold” stories shed light on the current diplomatic conflict. Many researchers have reviewed the confusion that frequently occurs in China-Canada relations (Gilley Citation2008; Evans Citation2006). Despite bilateral relations evolving from a “tepid” status to a much colder one, Development Diplomacy has the potential to help return some heat to the relationship.

Conclusion

This paper attempts to recapture an early example of Development Diplomacy embodied in the 1981–1984 NPLDP project, primarily via archive-based study. It also aims to broaden discussions by civilian stakeholders beyond the purview of sinologists and historians and refresh valuable memories of Canada−China development-aid events in the 1980s. These IFAD-NPLDP consultants, identified first as Canadian citizens, represented some reasonable and pragmatic voices with substantive experience. Their early experiences emphasized the potential for long-term community-based engagement with diverse stakeholders in multilateral collaboration. It is clear that the expertise of NPLDP project members from Canada was never utilized in a fashion that might have seen their knowledge transferred to the next generation of developmental agency workers. This article calls for more specific reflection on how future efforts can build on the experiences of the past.

This article interprets early Canadian consulting activities in China’s first IFAD-funded project as early practices of Development Diplomacy within the PD theoretical framework. Archival findings endorse policy commitment with continual initiative for multilateral development-aid collaboration. Engaging more stakeholders must move beyond identity politics with Cold War languages or “othering” rhetoric. Multilateral development-aid agendas stabilize bilateral relations via engaging more local communities with less ideological interference. This study identifies those non-state participants as the Canadian people’s agents involved in this NPLDP case with their local civil societies and state agency partners. These historical inquiries attempt to tease out what factors in this study case could somehow herald more development-aid continuities and policy lessons. The archival evidence helps refresh memories of Canadian development-aid activities in 1980s China.

Examining the “lost” stories of Canadian engagement in the NPLDP case contributes to the historical record by contextualizing early Canadian international development-aid practices involving China. Although this early Canadian engagement in this early-1980s study case has not gained public recognition, it has a place in history as one of China’s first international multilateral development aid projects. The impacts of the experts who worked on this project are still being felt in development aid projects in both countries. Development Diplomacy can also be seen as highly relevant today, in a time of cooler China-Canada relations, as a pathway to improve international relations and stimulate the relevant discourses for “other diplomacy” with more “de-othering” narratives. Many early bilateral policy setbacks have accompanied historical ignorance, featured by “othering” narratives and post-Cold-War rhetoric. This article hopefully mobilizes historical lessons in addressing future policy barriers for more alternative solutions. The PD ideas should help (re-)normalize bilateral relations via engaging more civilian stakeholders with long-term initiatives of Development Diplomacy, along with other inclusive people-to-people platforms.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is credited to valuable comments by two anonymous reviewers and many colleagues. The authors also appreciate enormous help in accessing the primary sources in this case study, with great gratitude for the support by the University of Regina and the QIEEP at Queen’s University.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Warren Mabee

Warren Mabee (PhD 2001, Toronto) is Associate Dean and Director of the School of Policy Studies and a Professor in the Department of Geography and Planning at Queen's University. His past work experiences include stints at the University of British Columbia and the University of Toronto, as well as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the International Energy Agency.

Yun Liu

Yun Liu, PhD, works for the Department of International Studies, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, China, and is also affiliated with the Queen’s Institute of Energy and Environmental Policy, Queen’s University, and the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Regina. His research interests have focused on the cross-disciplinary themes concerning Globalization, South–North relations, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals within the local and global contexts.

Notes

1 The contributors include Eugene Donefer, Kevin Wade, Deborah Turnbull, Frank Schneider, Mehdi Abdelwahab, and Zheng Li, plus some research colleagues in Queen’s and U. of Regina, besides two anonymous reviewers.

2 This federal company was amalgamated into Stantec Consulting in 1997. Check our correspondence list with contributors and the federal company registrar record.

3 Check the news report, e.g. the Reuters, on 2021-Sept-26, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/canada-foreign-minister-says-eyes-wide-open-when-it-comes-normalizing-china-ties-2021-09-26/; also the public statement by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2021-Sept-25, and check the commentary of the Global Times https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1235266.shtml?id=11;

4 Refer to the pitch note by David Webster, titled “Meng for the two Michaels: Lessons for the world from the China-Canada prisoner swap,” Conversation Canada, 2021-Sept-26. https://theconversation.com/meng-for-the-two-michaels-lessons-for-the-world-from-the-china-canada-prisoner-swap-168737

5 Canada has been the founding member, and top donner of the IFAD since 1977; see the IFAD member pages, as well as the open project database by the IFAD. https://www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/w/country/china

6 Our story-lead came first from Eugene Donefer, one of the IFAD consultants and the retired head of the International Office at McGill University during 1985–1995 when he visited China annually. The authors contacted the IFAD Rome headquarters and Beijing office, the Library and Archive Canada. Eventually, getting connected with some Agrodev retiree staff, this article collected first-hand records and personal documents as our primary resource.

7 More precisely, the General Bureau of Animal Husbandry (GBAH) is a division of the latter. Refer to the preface of the final report of consulting activities presented by Agrodev.

8 Page 7, Macdonald Journal, Vol. 44–46 No. 2: May 1984. The issue included an article by Dr. Downey describing his experience in Heilongjiang, plus six Chinese graduate students and scholars involved in four different programs, funded by the Chinese Government and the CIDA and IDRC (International Development Research Centre).

9 Part 1 Chapter 3, page 71; Animal Science at McGill: 50 years and counting, a brief history of McGill University's Department of Animal Science, Kevin Wade, published on July 17, 2018.

10 This content is not accessible anymore, but a much shorter version still exists online. Refer to the profile of China Northern Pasture and Livestock Development project [062-CH] and https://www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/-/project/1100000062. Our archival records from the IFAD and Agrodev will be abbreviated afterwards as NPLDP-IFAD and NPLDP-Agrodev, respectively.

11 See pages 77–79, appendix 1 in the final report in the NPLDP-Agrodev archive.

12 In a few cases, the consulting period for each individual had just one month, e.g., Z. Liu, who stayed from August 11 to September 10, 1982, first as the Design & Analyst. There was no record of consulting activities in 1983 under the entry of Z. Liu, but twice a week in 1984, May 7th-May 22th, and December 10th-January 9th, as Monitoring & Evaluation instead, see item 03 and 03A; another case: B. Baker, as the expert of Crop Preservation stayed July 4th-August 4th, 1982 and was not on the list afterwards. See entry item 017.

13 Page 79, the final report of consulting activities, NPLDP-Arogdev.

14 Pp. 80–82, the final report of consulting activities, NPLDP-Arogdev. Some members, like Team leaders, experts for Design and Analysis, Monitoring and Evaluation, or Liaison Officer, are not included in this table because they were all based in Beijing; the Project Manager mainly operated in Canada.

15 Refer to the field reports on these sub-project cites in appendix 5, pp. 100–148, NPDLP-Agrodeve.

16 Page 10, Section 1.3 Project Design and RationalRationale, in the final report, the NPLDP-Agrodev.

17 Pp. 462–463, the list of Core/Category I and Non-Core/Category II, Contrie, Morrison Citation2012, Aid and Ebb Tide. The authors note that while there should be some materials not yet archived in the Library and Archives Canada massive and only partly catalogued RG74 (CIDA) records, there is astonishingly little on this NPLDP story.

18 Refer to the NPLDF-Agrodev record of 45 personnel trips with 28 appointments.

19 One of their primary sources came from the IMAR: AHMOCC (Animal Husbandry Modernization Office of Chifeng City), “North China Pasture and Livestock Development Project” (Chifeng City: AHMOCC 1989). In Chinese.

20 Page 1163, citing from the article summary by Brown and Longworth Citation1992. See also Brown, Waldron, and Longworth Citation2008; Waldron, Brown, and Longworth Citation2010.

21 Page 77, 89, the relevant records in the final report of consulting activities, by E. McIntosh, April 04-May 31, 1982.

22 Refer to the Balin Right-Banner county government website: http://www.blyq.gov.cn/zjbl/show-18491.html.

23 Ibid. Page 69, and their reference on Canada-China Sustainable Agriculture Development, supported by the Canadian International Development Agency, and started from 2003 and even earlier fieldwork in that region back to 1987,

24 One more sub-project was added to the IFAD report, making the final figures for 31 sub-project sites.

25 Refer to a few research publications coming from UK and Europe in the 1980s, pages 24–25.

26 The central government archive database, file number: 000014349/1990–00013, publically accessible after 2010 as catalogued: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2010-12/17/content_3327.htm?trs=1

27 The field reports on soils and ranch management in Fuyu county, appendix 5, pp. 100–101, 133, NPLDP-Agrodev.

28 Based on its corporate history profile, local public reports in Canada and China, and direct inquiries with its Kingston management by emails or in person on various occasions. Also see pp. 25, 49–51; Gorissen and Vermeer Citation1985.

29 See their highly-cited research publications, e.g. “Strengthening incentives for improved grassland management in China and Mongolia,” Sept. 2015–Dec. 2019, Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

30 Refer to the IFAD project profile, Project ID: 1100001400, titled "Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Rural Advancement Programme."https://www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/-/project/1100001400

31 Pp. 258–259 refers to the arguable justification and narratives on the ban on initiatives that “might strengthen the repressive capacity of the Chinese government.” Morrison Citation2012.

32 Refer to the webpages for the projects and programs by country in the open database of the IFAD from: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/w/country/china#anchor-projects_and_programmes

33 Pp. 1770–1772, Colin and Longworth, 1992, refer to the section on technical investment versus institutional and policy reforms for sustainable development.

34 Section 3 Recommendations, in the final report of consulting activities, contributed by Agrodev, pp. 64–70.

35 The project was co-hosted by the University of Regain and its Chinese partners in Jilin province, among a list of Canada-China higher-education partnership programs funded by CIDA after the later 1990s.

References

- Aronczyk, Melissa. 2013. Branding the Nation: The Global Business of National Identity. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Azar, Edward E., and Chung In Moon. 1986. “Managing Protracted Social Conflicts in the Third World: Facilitation and Development Diplomacy.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 15 (3): 393–406. doi:10.1177/03058298860150030601

- Brown, Colin G., and John W. Longworth. 1992. “Multilateral Assistance and Sustainable Development: The Case of an IFAD Project in the Pastoral Region of China.” World Development 20 (11): 1663–1674. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(92)90021-M

- Brown, Colin, Scott Waldron, and John Longworth. 2008. Sustainable Development in Western China: Managing People, Livestock and Grasslands in Pastoral Areas. United Kingdom: Edward Elgar.

- Butterfield, Herbert. 1966. “The New Diplomacy and Historical Diplomacy.” In Diplomatic Investigations: Essays in the Theory of International Politics, edited by Herbert Butterfield, Martin Wight, and Hedley Bull, 181–192. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Chin, Gregory. 2009. “Shifting Purpose: Asia's Rise and Canada's Foreign Aid.” International Journal 64 (4): 989–1009. doi:10.1177/002070200906400409

- Evans, Paul. 2006. “Canada, Meet Global China.” International Journal 61 (2): 283–297. doi:10.2307/40204157

- Evans, Paul, and B. Frolic, eds. 1991. Reluctant Adversaries: Canada and the People's Republic of China, 1949–1970. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Gilley, Bruce. 2008. “Reawakening Canada's China Policy.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 14 (2): 121–130. doi:10.1080/11926422.2008.9673467

- Gorissen, P. J. A., and Eduard Boudewijn Vermeer. 1985. Development of Milk Production in China in the 1980s. Wageningen: Pubdoc.

- Hanlon, Robert J. 2012. “Leveraging Talent: Exporting Ideas in the Asian Century.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 18 (3): 358–374. doi:10.1080/11926422.2012.742023

- Hayhoe, Ruth, Julia Pan, and Qiang Zha. 2013. “Lessons from the Legacy of Canada−China University Linkages.” Frontiers of Education in China 8 (1): 80–104. doi:10.1007/BF03396963

- Hayhoe, Ruth, Julia Pan, and Qiang Zha, eds. 2016. Canadian Universities in China's Transformation: An Untold Story. Montreal Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Huijgh, Ellen. 2019. Changing Tunes for Public Diplomacy: Exploring the Domestic Dimension. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff.

- Lan, Kenneth. 2020. “The Invaluable Experience: Martin Singer and Concordia's Extraordinary Path to Open China's Door to the World.” Asian Education and Development Studies 9 (4): 511–520. doi:10.1108/AEDS-01-2018-0020

- Manfredi-Sánchez, Juan Luis. 2022. “Vaccine (Public) Diplomacy: Legitimacy Narratives in the Pandemic Age.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2: 1–13. doi:10.1057/s41254-022-00258-2

- Meehan, John, and David Webster. 2013. “A Deeper Engagement: People, Institutions and Cultural Connections in Canada−China Relations.” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 20 (2/3): 109–116. doi:10.1163/18765610-02003013

- Morrison, David R. 2012. Aid and Ebb Tide: A History of CIDA and Canadian Development Assistance. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press in association with the North-South Institute = L'Institut Nord-Sud.

- Muirhead, Bruce. 2009. China and Canadian Official Development Assistance: Reassessing the Relationship, China and Canadian Official Development Assistance. Ottawa: Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.

- Nossal, Kim Richard, and Leah Sarson. 2014. “About Face: Explaining Changes in Canada's China Policy, 2006–2012.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 20 (2): 146–162. doi:10.1080/11926422.2014.934864

- Nye, Joseph S. 2008. “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (1): 94–109. doi:10.1177/0002716207311699

- Nye, Joseph S. 2019. “Soft Power and Public Diplomacy Revisited.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 2019 (1–2): 7–20. doi:10.1163/1871191X-14101013

- Potter, Evan. 2003. “Canada and the New Public Diplomacy.” International Journal 58 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1177/002070200305800103

- Potter, Evan H. 2009. Branding Canada: Projecting Canada's Soft Power Through Public Diplomacy. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Sharp, Paul. 2003. “Herbert Butterfield, the English School and the Civilizing Virtues of Diplomacy.” International Affairs 79 (4): 855–878. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.00340

- Sheehy, Dennis, Thorpe Jeffrey, and Kirychuk Brant. 2006. “Rangeland, Livestock and Herders Revisited in the Northern Pastoral Region of China.” Rangelands of Central Asia: Proceedings of the Conference on Transformations, Issues, and Future Challenges: January 24–30, 2004, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Sinclair, Paul, and Dongyan Ru Blachford. 2018. “Agriculture and Sino-Canadian Relations Hsieh Pei-chi and His Farmers Program.” China Review 18 (3): 207–232.

- Sinclair, Paul, Dongyan Blachford, and André Magnan. 2016. “The 1980 China Farmers Program: Shaping Canada’s Agricultural Relationship with China.” Prairie Forum.

- Sinclair, Paul, Dongyan Blachford, and Garth Pickard. 2015. “‘Sustainable Development’ and CIDA’s China Program: A Saskatchewan Case Study.” Frontiers of Education in China 10 (3): 401–426. doi:10.1007/BF03397077

- Stevenson, Michael D., and Greg Donaghy. 2009. “The Limits of Alliance: Cold War Solidarity and Canadian Wheat Exports to China, 1950–1963.” Agricultural History 83 (1): 29–50. doi:10.3098/ah.2008.83.1.29

- Vlassis, Antonios. 2016. “Soft Power, Global Governance of Cultural Industries and Rising Powers: The Case of China.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 22 (4): 481–496. doi:10.1080/10286632.2014.1002487

- Waldron, Scott, Colin Brown, and John Longworth. 2010. “Grassland Degradation and Livelihoods in China's Western Pastoral Region.” China Agricultural Economic Review 2 (3): 298–320. doi:10.1108/17561371011078435

- Wang, Y. W. 2008. “Public Diplomacy and the Rise of Chinese Soft Power.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616: 257–273. doi:10.1177/0002716207312757

- Young, Mary M., and Susan J. Henders. 2012. ““Other Diplomacies” and the Making of Canada–Asia Relations.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 18 (3): 375–388. doi:10.1080/11926422.2012.742022

- Zha, Qiang. 2011. “Canadian and Chinese Collaboration on Education: From Unilateral to Bilateral Exchanges.” In The China Challenge, edited by Huhua Cao and Vivienne Poy, 100–120. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.