ABSTRACT

This article analyzes different visions and positions in a conflict between the developer of an open-pit mine in Mexico and project opponents using the echelons of rights analysis framework, distinguishing four layers of dispute: contested resources; contents of rules and regulations; decision-making power; and discourses. Complexities in this study manifest how communities’ land and water rights are circumvented by governmental bodies and ambivalent regulations favouring the large mining company. This process is importantly reinforced by international trade legislation. Multi-actor, multi-scale alliances may offer opportunities to foster environmental and social justice solutions.

Introduction

In 1996, Minera San Xavier (MSX), Mexican tributary of the Canadian mining company Newgold Inc., announced that it wanted to start a large open-pit gold and silver mine () in the municipality of Cerro de San Pedro, occupying 373 ha of community land. This was subject to great controversy as the scale and type of mining operation would put a heavy burden on the available land and water, not to mention adverse environmental effects. Resistance was fierce, and several opposition groups united themselves in the Frente Amplio Opositor (Broad Opposition Front, or BOF). Despite the opposition, MSX started operating in 2007. As of this writing, its presence is still being disputed.

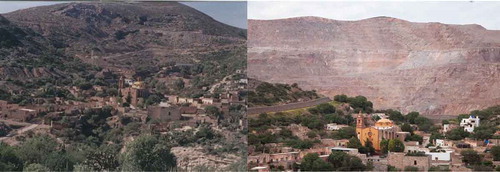

Figure 1. Before and after. On the left, the hill of Cerro de San Pedro before 2007, when operation of the mine started. On the right, the status of the landscape at the same time of year in 2013. The open-pit mine about 200 m from the centre of the village of Cerro de San Pedro has caused a large conflict that continues to date. (Left photo from BOF, Citation2013; right photo, Jesse Samaniego Leyva, 2013.)

Though mining is a highly profitable business for some actors, the downsides of mining activity are becoming more and more obvious. Environmental degradation, illegal land acquisition, water contamination, corruption, violence, resistance and conflict are often associated with mining development (Hogenboom, Citation2012; van der Sandt, Citation2009; Wilder & Romero-Lankao, Citation2006). Campesino (peasant) and indigenous communities are affected by mining activity in the area, and the livelihood strategies of mine-adjacent communities are often endangered through decreased access to and control over the land (Peace Brigades Internacionales, Citation2011; van der Sandt, Citation2009). Frequently, the economic ‘benefits’ promised by mining companies, for example in the form of temporary employment, do not outweigh the losses suffered (Perreault, Citation2014; Sosa & Zwarteveen, Citation2011; Yacoub, Duarte-Abadía, & Boelens, Citation2015). These negative effects often give rise to conflicts, and, unfortunately, conflict in a ‘miningscape’ is generally the rule rather than the exception. In 2013, the Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros en América Latina (OCMAL, Citation2014) registered 13 large-scale mining conflicts in Mexico, most of which involved foreign companies. One of these conflicts is taking place in Cerro de San Pedro.

This article elaborates how conflict arose over land and water rights between inhabitants of Cerro de San Pedro and MSX. The article examines how this ‘natural resources conflict’ is not just about rights to access resources, but also about underlying injustice in local, national and international rules and regulations, and about the question of the legitimacy and authority to shape these rules. It also shows how interconnected, powerful actor alliances, discourses, and knowledge claims profoundly influence the struggle over land and water in this municipality.

The article is based on literature and archival investigation throughout 2013 and field research in September–December 2013 in Cerro de San Pedro, with follow-up correspondence and conversations in 2014 and 2015. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with inhabitants of Cerro de San Pedro and surrounding villages, migrants who had left the zone, local municipality and government officials, mine representatives, mine-opposing groups, and journalists and scholars in San Luis Potosí. Next, a series of interviews were conducted (in three meetings each) with particular, representative individuals living in the mining area, whose life histories were compiled. Quotes and comments were taken from several interviews and conversations (all in Spanish and translated by the authors), which were conducted during both formal and informal encounters whilst performing fieldwork in Cerro de San Pedro (names of interviewees have been changed where needed to protect informants). The research for this article forms part of the activities of the international research and action alliance Justicia Hídrica/Water Justice.

The structure of the article is as follows. In the next section Mexico’s neoliberal development, which paved the way for MSX to operate in Cerro de San Pedro, is elaborated. In the third section the background of the conflict over natural resources in Cerro de San Pedro is discussed, after which the conceptual framework, echelons of rights analysis, used to analyze the conflict is explained. In the fifth section the results are presented. The concluding section reflects on how economic interests and associated discursive practices have had severe implications for the inhabitants of Cerro de San Pedro.

The background: Mexico, a protectionist state, takes a neoliberal path

To understand the conflict in Cerro de San Pedro, a brief look at the history of Mexico’s laws concerning land, water and mining in the last century is essential. After the revolution of 1910, Mexico created a protectionist state in which land and water rights were a noncommodity. After years of unequal division of land and water under the hacienda system, the Mexican government expropriated the large landowners and reallocated the majority of the land and water to former day-labourers. These labourers formed farmer groups that collectively manage the resources to this day: the so-called ejidos, or social property sector. Under the ejido system, the majority of the allocated land is managed collectively whilst a small part can be cultivated for private purposes (Assies & Duhau, Citation2009). Under the law of ejido tenure, land was a non-negotiable resource. Article 74 of the Mexican Constitution stated that the ownership of common-use land is “imprescriptible, inalienable e inembargable [imprescriptible, inalienable and indefeasible]”, i.e., land could not be transferred to third parties, land rights could not expire, and they could not be seized through an injunction (Herman, Citation2010). Water rights were linked to agricultural property rights under ejidal law, which means that they could not be sold, rented out, used on other lands, or used for purposes other than those stated in the grant (Assies, Citation2008).

However, after 1992, legislation on land and water rights changed. In the 1980s Mexico faced a severe economic crisis, and the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Inter-American Development Bank demanded that Mexico adopt neoliberal policies if the country wanted to obtain international credit, similar to many other Latin American countries in the 1980s and 1990s (Achterhuis, Boelens, & Zwarteveen, Citation2010; Hogenboom, Citation1998, Citation2012; Wilder, Citation2010). The main focus of the restructuring of the economy was on opening the Mexican market to foreign investment. The social property sector and its regulatory framework of the time did not allow private ownership, as ejidos could not legally be privatized. This conflicted with the aim of increased foreign investment in Mexico, as land and water could not be converted into private and transferable commodities. Hence, according to neoliberal policy makers, if Mexico was to increase private (foreign) investment, legislation on land and water rights needed modification (Herman, Citation2010). Among others, the Agricultural Law, the Mining Law and the Foreign Investment Law were profoundly changed. To open up the mining sector to foreign mining companies, an amendment was made to Article 6 of the Mining Law that enables land to be alienated through “temporary occupancy”. This provision enables mining activity to occupy land, and prioritizes mining above any other form of land use. The temporary occupancy permit is granted by Mexico’s Ministry of Economics (Bricker, Citation2009; Herman, Citation2010). The 1992 market revisions paved the way for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which Mexico joined in 1994 (e.g. Hogenboom, Citation1998). Through NAFTA, foreign direct investment was stimulated greatly, and it was predicted that Mexico, as a developing country, would economically benefit most from these investments (Krueger, Citation1999; Ramirez, Citation2003). Meanwhile, for Canadian and US mining companies it became appealing to invest in Mexico due to the relatively low tax rates. It was shortly after the union with NAFTA that MSX announced its interest in exploiting the minerals in Cerro de San Pedro.

NAFTA has received criticism that environmental standards are easy to circumvent, due to the ‘investor-state mechanism’ that NAFTA encompasses. NAFTA aims to have investors of different countries treated equally and protected from expropriation by all levels of the (host) government. NAFTA’s Chapter 11 gives an investor the right to challenge the government for noncompliance with the agreements made in NAFTA, in an international court, superseding national law. In the design phase, this mechanism was meant as a defensive measure to protect foreign companies against arbitrary and unreasonable government actions. However, it has had several deeply problematic side effects (Hogenboom, Citation1998, Citation2012; Solanes & Jouravlev, Citation2006, Citation2007). For example, first, it allows foreign companies to operate in the host country, but in case of a dispute they can go directly to the international arbitration process and entirely bypass domestic courts. Second, starting this process is relatively cheap and easy. This makes it an attractive option for foreign companies that wish to protect themselves against restrictions posed by new environmental laws or social security policies which could have a negative impact on their business (Mann & Von Moltke, Citation1999). The option of appealing to the international court under NAFTA is only available to companies operating under NAFTA, and not, for example, to communities or other non-business stakeholders who fear injustice, unequal competition, or socio-environmental costs (Herman, Citation2010; Nogales, Citation2002). On more than one occasion, multinational companies have used the possibility of suing governments for noncompliance with agreements made in NAFTA to prevail against environmental restrictions (Hogenboom, Citation1998, Citation2012; Solanes & Jouravlev, Citation2006, Citation2007). For example, near Cerro de San Pedro, in 2001, the American corporation Metalclad was awarded $16.5 million dollars by the NAFTA committee after the state of San Luis Potosí refused the installation of a hazardous waste transfer station. This shocked both national actors and international environmentalists (Kass & McCarrol, Citation2000).

The conflict in Cerro de San Pedro

Cerro de San Pedro has a long mining history. The gold and silver reserves in the area were already exploited by the indigenous inhabitants of Cerro de San Pedro, the Huachichiles, before the Spanish arrived. The Spanish conquistadores started exploiting the first mines in Cerro de San Pedro in the sixteenth century (Reygadas & Reyna Jiménez, Citation2008; Vargaz-Hernandez, Citation2006). Over time, several mining companies have come and gone in Cerro de San Pedro. Livelihoods were based on mining and agriculture, the latter practised for subsistence purposes under the ejido system.

The last large mining enterprise, before the current mining company, was active until 1948: the American Smelting and Refinery Company. After its shutdown, the majority of the miner families left the town to work in other mines in the north of Mexico; others went to San Luis Potosí in search of jobs. The remaining inhabitants developed new livelihood strategies, for instance based on tourism, making use of the local ecology and cultural heritage opportunities (interviews with local residents, October 2013; Reygadas & Reyna Jiménez, Citation2008; Vargaz-Hernandez, Citation2006). As soon as MSX announced that it wanted to exploit the minerals by means of an open-pit mine in 1996, opposition to the project started, involving inhabitants from Cerro de San Pedro and neighbouring villages, as well as relatives and ex-villagers now residing in cities like San Luis Potosí.

The mine covers 373 ha and consists of a large open pit, two waste dumps and a lixiviation area. In the lixiviation area, a water-cyanide solution is applied to the rock debris, dissolving the gold and silver particles. From the bottom of the heap the solution, now enriched with gold and silver particles, is drained. Eventually the water is evaporated, and what remains is a mixture of gold and silver known as doré. For this process, 16 tonnes of cyanide, dissolved in 32 million litres of water, is applied daily to the lixiviation area (Newgold Inc., Citation2009). MSX has water concessions for 1.3 MCM (million cubic metres) per year, but project opponents claim that the actual water extraction is much higher, and simple calculations show that the actual water needs of the mine are many times this figure (pers. comm., BOF member Eduardo da Silva, November 2014). For comparison, Interapas, which is responsible for the drinking water supply of the four municipalities close to the city of San Luis Potosí (more than a million people), has a total authorized annual extraction of 85 MCM of water (Peña & Herrera, Citation2008b). This use of cyanide, amongst other issues, has given rise to great opposition, as water is scarce in the area and cyanide is extremely toxic (Lutz, Citation2010). Years of litigation followed, during which a large number of court cases were filed, rejected, delayed or overruled by other courts. A large number of court cases were filed against MSX, questioning the legitimacy of the environmental/land use change permit, the mine’s water use permit, and many other issues. Despite the mine’s having lost a number of these court cases, MSX started its mining operation in 2007 (Herman, Citation2010; Peña & Herrera, Citation2008a). To date, MSX is still active in Cerro de San Pedro, but in 2015 the company announced it would gradually shut down the mine and accordingly start rehabilitation activities. These rehabilitation activities are described in MSX’s project plan. They form part of a larger ‘shutdown plan’, in which MSX describes the process of closing the mine, and have been approved by the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources). Examples of planned rehabilitation activities are sterilization of the lixiviation area and reforestation of the mining pit. However, deep distrust of the mining company and the Mexican government, due to a lack of transparency and suspicion of corruption (as explained later), has caused the BOF to demand that the president of the municipality form a commission of independent experts to supervise the remediation work and its effectiveness (pers. comm., BOF, December 2015). Given the hugely problematic and controversial track record of the company, the government and other mining companies in the country in terms of (in)action regarding socio-environmental rehabilitation, this lack of trust is deep and generalized in the population.

Changing landscapes and waterscapes in Cerro de San Pedro

Unlike earlier decades’ (tunnel-based) mining operations, the current open-pit mining practices have had a tremendous impact on the land and waterscape. The hill itself (Cerro de San Pedro, the Hill of Saint Peter) – the place containing gold and silver particles – has been completely excavated (63 ha); beside it, two new hills of waste material have emerged (145 ha), and a newly constructed hill two kilometres to the south makes up the lixiviation area (120 ha). The new hills have altered the natural drainage pattern, blocking a dam and river in the village. Great amounts of dust cause severe pollution (Gordoa, Citation2011), and farmers in the area complain of crop failure caused by the pollution (interviews with local farmers, October 2013). The profound changes in the landscape caused by the mine were fiercely opposed. The litigation process in obtaining permits was seemingly never-ending, with courts referring to other courts and rejecting responsibility, creating a vicious cycle of court cases with no solid resolution (Herman, Citation2010; Peña & Herrera, Citation2008a). The differing opinions within the village drove a wedge between villagers, and a fully fledged conflict started in Cerro de San Pedro. Project opponents living in Cerro de San Pedro talk about cases of severe intimidation, aggression and violence against them, inflicted on them by both MSX employees and pro-MSX villagers. The economic interests in the realization of the mining project were enormous, and the national government put pressure on local authorities to issue the required permits. Oscár Loredo, the young mayor of Cerro de San Pedro, at first announced that he would not ratify municipal permits, but later changed his mind. He claimed that he was being put under great pressure by MSX, by the state, and even by the president (Vicente Fox), and that he could no longer stand the pressure. He claimed that he felt he had no choice and that his life was at risk. He added that his personal fears had made him change his mind about the matter. When challenged by one of the council members, the mayor responded: “Does my life not matter to you?” (Herman, Citation2010; Reygadas & Reyna Jiménez, Citation2008). Shortly afterwards, the municipal permits were ratified. A few years before, the former mayor, Baltazar Loredo (father of Oscár Loredo), was murdered after openly opposing the mining project (Vargaz-Hernandez, Citation2006).

Water availability in Cerro de San Pedro

Cerro de San Pedro and the city of San Luis Potosí are located in the hydrological watershed of the Valle de San Luis Potosí. This watershed stretches over approximately 1900 km2 and supplies drinking water for about 90% of the San Luis Potosí population (more than a million people). The Valle de San Luis Potosí aquifer is being over-exploited: yearly, approximately 149.34 MCM is extracted from the deep aquifer, while only an estimated 78.1 MCM recharges it (Santacruz De Leon, Citation2008). As a way of mitigating aquifer over-exploitation, the Mexican government declared a zona de veda in the area.Footnote1 Vedas are designed to prevent uncontrolled and unlimited water extraction from the deep aquifer, and thus aim to obtain a sustainable equilibrium, allowing human activities without degrading the environment (Conagua, Citation2012). Since 1961 the largest part of the Valle de San Luis Potosí aquifer has been subject to the veda, including the mine in Cerro de San Pedro (Conagua, Citation2004).

Another decree, issued 24 September 1993, designates 75% of the municipality of Cerro de San Pedro as a zona de preservación de la vida silvestre (zone for the preservation of wildlife). This decree was issued a few years before MSX announced its interest in exploiting the gold and silver reserves of the area (BOF, Citation2014). The State Congress assigned Cerro de San Pedro and the surrounding area this protected status due to its ecological function and importance for watersheds. This was formalized in a state decree, which mandated that in 75% of the municipality of Cerro de San Pedro (1) no changes were to be made in the subsoil for a period of 20 years; (2) the area was not suited for industrial activities with high water consumption; and (3) it was acknowledged as having an important function for wildlife preservation (Gordoa, Citation2011; Vargaz-Hernandez, Citation2006).

Despite the veda and the watershed protection status, MSX has managed to bypass all regulations and court cases by obtaining a temporary occupancy permit and thus to start and continue mining. To illustrate the consequences, we present life histories from two affected families who took diverging paths. These stories show that some families outright opposed the transformation of their livelihoods, while others thought they could take advantage of the economic opportunities the mine would offer. After that, we present brief conceptual notes to examine the natural resource conflicts in Cerro de San Pedro.

Subsistence and opposition: the story of Doña Morena Sanchez Aguilar

“MSX arrived in 1996 and announced it wanted to start an open-pit mine. My husband and I were against the plans from the very beginning; we saw that they would destroy our surroundings, the land with which we are connected. My family descends from the indigenous Huachichiles: I belong here, this is my land. Moreover, we never saw the need to work for the mine. We saw another future for Cerro de San Pedro. Tourism was starting to pick up, and there were plans for the development of Cerro de San Pedro, such as the building of a hotel and restaurants. We didn’t need the mine at all! Before MSX arrived, life was very different in Cerro de San Pedro. The town was united: we used to have dinner together, there were masses, sometimes we would dance on the square. This all changed when MSX came. They divided us. In the very beginning, almost everyone was against the plans of MSX. However, when MSX started to pay people for their ‘vote’, things changed. Our neighbours became our enemies! It got really violent, once they even tried to shoot my husband. The mine tried to silence the people who were against them. Houses were set on fire, our house was boarded up, all to intimidate us. Yet it was never proven that the mine was behind these things. These were really scary times, especially when our mayor was murdered. We stayed in the house and didn’t meet up with our neighbours anymore. We were lonely. My husband, who was the fiercest in his opposition against the mine, passed away a year ago. Since then, the relationship with our neighbours has normalized a bit. We greet each other in the streets again. Yet we never interact with those who work for the mine. Sometimes MSX invites us for activities, but we never go. They might be starting to think we’re now okay with the presence of the mine, but we are not. Moreover, we will never forget how our neighbours treated and threatened us a few years ago. This village is now a divided place. Life will never be the same here.” (Interview with Doña Morena, November 2013)

Joining the opportunities offered by mining? The story of Don Vicente Estrada Diaz

“In 1996 Minera San Xavier came. They started going by our houses and told us that they were planning to start a mine here. They promised us that the mine would bring us a lot of benefits: job positions for everyone living in the village, a medical station, scholarships for our kids, and so on. I wanted a better future for my children; I wanted to give them the opportunity to study, which I never had. So to me this sounded like a great opportunity, and we agreed with the plans. My brothers and I sold about 19 hectares of our land, which we previously used to cultivate, to MSX. I am in favour of the mine out of necessity: I wanted job opportunities for me, my family and my village, and MSX was the only option we had. In other words, I am not in favour of the mine but in favour of a source of work. Of course I don’t like the total change of our environment, or the contamination that mining activity brings about. Yet in MSX I saw the only way out of our poverty. Nowadays I doubt whether I should have been so positive about MSX in the beginning. Back then, I was one of the first to be in favour of the mine, and I convinced many of my neighbours. I really thought that MSX would give us a better life, yet did I know that MSX would not live up to all those promises they made? Yes, MSX improved our livelihoods, but not as much as we all expected and hoped. I feel I have let my people down: I was the one most positive about the mine, and look what we have now. We are all very worried about the contamination. The dust pollution and maybe the cyanide have severely affected our harvest. I still cultivate my fields, but the one located close to the lixiviation area hasn’t given any yield at all. The plants are often covered in dust: how are they supposed to grow like that? It has rained quite a lot this year, and in other places my milpa grew pretty well. It must be the mine affecting my harvest, but what can I prove? I have no money or education to prove all this. We are very worried about the future. MSX is not going to operate here forever. What are we going to do when the mine is gone? The history is going to repeat itself. Everybody will leave our village, since there is no work. But this is where we were born, where we were raised and where we got married. How could we not love our land? Yet most of us stopped cultivating our land a long time ago. The best fields for cultivating were sold to MSX: now their offices are on top of it. Living off the land is a hard life and the young people are not attracted to this lifestyle anymore. On top of that, what can they do with a contaminated area? Only the old people, me, my wife and some other people, will stay here. But we have no option. When MSX goes, the life will go from our village as well.” (Interviews with Don Vicente Estrada, October–November 2013)

Conceptual notes: examining the entwined layers of the natural resource management conflict

In mining areas such as Cerro de San Pedro, the use of natural resources such as land and water lies at the root of local inhabitants’ livelihoods. Consequently, opposing interests and the struggle over access to and withdrawal of these natural resources has high potential for conflict. When new stakeholders, such as the MSX gold mine, enter the playing field and claim a substantial share of the resources, access rights are commonly reallocated through an interplay of (socio)legal, economic and political power. Redefinition of rights always causes some actors or use sectors to lose, such as less well-accommodated social groups, or the environment, while others reap the benefits and strengthen their political and economic positions – a basic tenet in political ecology (e.g. Forsyth, Citation2003; Neumann, Citation2005; Robbins, Citation2004).

In scrutinizing the conflicts that arise during the reallocation of natural resources, political ecology does not only attempt to focus on which population groups are most affected by these politics. It also aims to clarify the political forces that are at the roots of environmental distribution conflicts (e.g., Boelens, Citation2009, Citation2015; Brooks, Thompson, & El Fattal, Citation2007, Citation2013; Martínez-Alier, Citation2003; Neumann, Citation2005; Peet & Watts, Citation1996; Robbins, Citation2004; Turton, Citation2010; Wilder, Citation2010). Further, in order to grasp such political forces and their unequal outcomes in terms of resource distribution, there is also the need to focus on the ways in which environmental knowledge itself is produced, how ‘knowers’ are defined, by whom, and how they conceptualize ‘environmental problems’ and ‘solutions’. All of these often implicitly generate uneven allocation of social costs and benefits. As Hajer (Citation1993, p. 5) commented: “The new environmental conflict should not be conceptualized as a conflict over a predefined unequivocal problem with competing actors pro and con, but is to be seen as a complex and continuous struggle over the definition and the meaning of the environmental problem itself” (see also Forsyth, Citation2003). Different actors, with different socio-economic, cultural and political backgrounds, will commonly perceive and evaluate environmental transformations differently, and therefore use different frameworks to construct their “environmental imaginaries” (Peet & Watts, Citation1996, p. 37; see also Feindt & Oels, Citation2005).

As is common in such water extraction disputes, the conflict in Cerro de San Pedro exhibits many different levels and issues over which actors collide (Adler et al., Citation2007; Achterhuis et al., Citation2010; Brooks et al., Citation2007; Martínez-Alier, Citation2003; Turton, Citation2010; Wilder, Citation2010). To unravel the depths of the conflict, we use the echelons of rights analysis (ERA) framework (Boelens, Citation2009, Citation2015; Duarte-Abadía, Boelens, & Roa-Avendaño, Citation2015; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014). ERA can be applied to conceptually and empirically distinguish several mutually linked levels of abstraction within a natural resource management (e.g., water governance) conflict:

The first echelon is about conflicts over access to and withdrawal of resources. In order to materialize these access and withdrawal rights, technological artefacts, infrastructure, labour and financial resources have to be in place. In this echelon the conflicts regarding access to and distribution of the resource(s) in question are examined.

The second echelon refers to conflicts over the contents and meaning of the rules and regulations that are connected to resource distribution and management. Conflicts often occur over the contents of rules, norms and laws that determine the allocation and distribution of land, water and other territorial resources. Key elements of analysis in this field are the bundles of rights and obligations, roles and responsibilities of users, criteria for allocation based on the heterogeneous values and meanings given to the resource, and the diverse interpretations of fairness by different stakeholders.

At the third echelon, conflicts over decision-making power are analyzed. Who is entitled to participate in questions about the division of land and water rights? Whose definitions, interests and priorities prevail? Who is able to exert formal or informal influence, and how?

The fourth echelon is about the opposing discourses that are used by the different stakeholders to express the problems and solutions concerning land and water rights. Different regimes of representation claim ‘truth’ in different ways, and so legitimize their policies, plans, actions and the distribution of the resources. This last echelon seeks to coherently link all echelons together in one convincing framework (see e.g. Boelens, Citation2009, Citation2015; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014).

Throughout history and across continents and cultures, political and economic elites have often sought to justify their (often highly unequal) use of the environment by making use of a discourse that upholds this use as if it were for ‘the greater good’. Opposing groups subsequently challenge these elite groups by forming their own counter-discourse. Hence, as the ERA framework illustrates, environmental conflicts do not concern only material practices but are simultaneously struggles over rules, over authority, and over meaning and ideological structures. In miningscapes, as in other arenas where actors fight over natural resources, rather than a search for absolute truths about environmental problems, we witness a battle about “the rules according to which the true and false are separated and specific effects of power are attached to the true”, a struggle over “the status of truth and the economic and political role it plays” (Foucault, qtd. in Rabinow, Citation1991; see also Boelens, Citation2014; Boelens & Vos, Citation2012; Brooks et al., Citation2013; Forsyth, Citation2003; Turton & Funke, Citation2008; Wilder, Citation2010; Vos, Boelens, & Bustamante, Citation2006). As we see in this case about how the mining company MSX managed to get access to land and water rights in Cerro de San Pedro, discourses are not innocent tools: they often serve to justify particular policies and practices, and obliterate alternative modes of thinking and acting.

Unravelling the conflict in Cerro de San Pedro: the echelons of rights

Conflict over access to and withdrawal of land and water

In the analysis of the conflict in Cerro de San Pedro we see that on the surface the conflict revolves around access to land and water, the quality of these natural resources, and their use purposes and practices. Conflict over access to land is importantly expressed in the false lease contract that was presented by MSX, and the subsequent temporary occupancy of ejido land. Mexican law holds that the surface of the land belongs to the land right holders, in this case the ejidatarios, yet the subsoil remains the property of the government. This means that for MSX to obtain access to the land both a mining concession for the subsoil from the Mexican government and a rental agreement with the ejidatarios were required (Herman, Citation2010). Obtaining the mining concession from the government was not a problem. And since most rightful titleholders (ejidatarios) had left Cerro de San Pedro after 1948, MSX had the few remaining inhabitants (avecindados) sign a lease contract. However, these people did not hold the land title and thus could not legally rent the land to MSX. The false lease agreement was initially accepted, but eventually, in 2004, it was declared void. Meanwhile, between 1996 and 2004, despite the lack of a legal permit to access the land, MSX continued construction activities. Eventually, in 2005, a temporary occupancy permit was granted to MSX (Herman, Citation2010). The means by which the land was ‘temporarily occupied’ was also subject to controversy. In practice the occupancy means that local inhabitants are no longer able to use this land for agricultural purposes (for which the land was originally intended under the Agricultural Law), for tourism, or for artisanal mining.

Another part of the conflict is related to water use. MSX requires a large amount of water for operation of the mine, in an area in which water is already a scarce resource. The mining activity also has large impacts on the quality of the environment. Great controversy exists over the negative consequences for the quality of the land and water in the affected area, such as contamination of surface and groundwater; dust pollution; negative impacts on flora and fauna; contamination by heavy metals; and profound change of the surface of the landscape (Gordoa, Citation2011; Reyna Jiménez, Citation2009). The question is what quality of land and water will be left to local inhabitants after MSX closes the mine. Already evident is that, as explained above, the mining practices have transformed the territory into a huge open pit, altering its current and potential land uses, changing the village itself, drying out the groundwater wells, and even blocking the small river that once meandered through town but now has been usurped by the mine.

Disputing the content of the rules and regulations

Land rights. In Cerro de San Pedro, and Mexico in general, we see that the conflict is equally about the contents of the rules and regulations linked to mining and land and water use. At the very base of this conflict are two laws, the Agricultural Law and the Mining Law. Mexico’s Mining Law considers mining to be of benefit to the entire society. Thus, any kind of exploration, exploitation and beneficiation of minerals should get preference over any other types of land use, including agriculture and housing (GAES Consultancy, Citation2007; Herman, Citation2010). However, this is not in accordance with Article 75 of Mexico’s Agrarian Law, which states that “in cases where lands have been proven to be of use to the ejido population, the common land uses in which the ejido or ejidatarios participate may be prioritized” (Herman, Citation2010, p. 84). To ensure that mining activity can eventually take over all other forms of land use, Article 6 of the Mining Law enables land to be alienated through “temporary occupation” (Herman, Citation2010). Yet the Agricultural Law does not recognize this temporary-occupation instrument. Moreover, the Constitution considers land given to the ejidos “imprescribtible, inalienable e inembargable”. Nevertheless, the denial of these fundamental rights is precisely what has taken place in Cerro de San Pedro. By denying ejidatarios the property of the subsoil as well as the surface, ejidatarios are legally being excluded from the game. The Agricultural Law recognizes them as the legal landowners, but the Mining Law considers mining to be in the public interest. So, the threat of having their land expropriated in the name of this public interest is ever-present for local villagers. If landowners do not agree to a lease contract they risk losing everything, with no compensation, through temporary occupancy. This puts them in an unequal negotiation position and forces them to accept unfair lease contracts (Clark, Citation2003; Ochoa, Citation2006). The Mining Law’s temporary-occupancy provision de facto undermines the land titles of ejidatarios. Estrada and Hofbauer (Citation2001) and the BOF state that local inhabitants are even further disadvantaged by the lack of legal follow-up: the Agrarian Attorney is obligated to supervise and assess the process of selling or renting ejido land to third parties, yet in practice this is often not done. In Cerro de San Pedro (and the majority of similar cases in which lease or sale contracts were produced between ejidos and a mining company), the ejidatarios were not informed about their rights and the possible risks of living close to mining activity.

In addition, as we elaborate below, San Pedro’s customary rights and national agrarian laws supporting the position of Cerro de San Pedro’s landowners are even further hollowed out by NAFTA rules, which stimulate and empower investors’ rights and nullify the contents of local socio-legal arrangements protecting the environment and the community.

Water rights. Another subject of fierce conflict is the neoliberal policies that have converted water rights from a noncommodity into a tradable asset, which importantly favoured MSX’s opportunities to operate in San Luis Potosí. These changes have allowed purchase and sale of presumably out-of-use water permits and the proliferation of well perforations in the veda zone (considered, under the new laws, ‘relocation’ of the old well), despite the clear objective of reducing over-exploitation of the aquifer. MSX obtained its water permits by making use of the new regulation and thus managed to buy 12 concessions totalling 1.3 MCM annually (Newgold Inc., Citation2009; Santacruz De Leon, Citation2008). Project opponents state that, keeping in mind the severe over-exploitation of the aquifer, tradable water rights put extra pressure on the aquifer in San Luis Potosí and endanger future water provision for San Luis Potosí inhabitants. Moreover, opponents claim that the granting of 1.3 MCM of a ‘scarce resource’ for mining purposes shows that the so-called scarcity is not an environmental condition, but rather the result of priorities that the government assigns to certain uses. They argue that the government decides that for some uses water is ‘abundant’ whereas for others it is ‘scarce’ (Peña & Herrera, Citation2008b). Scarcity in this sense is a social construction and political phenomenon rather than a natural state of the environment.

Besides the veda, the 1993 preservation of wildlife decree (preventing industrial water use) was also circumnavigated by MSX, triggering important conflict. In 2005 the Sala Superior del Tribunal Federal de Justicia Fiscal y Administrativa (Superior Chamber of the Federal Fiscal and Administrative Federal Tribunal) declared that the 1993 decree speaks of “industrial activity” (which has lower water rights prioritization), and since mining can be considered a “primary activity” (with higher priority), it is not subject to the decree (Herman, Citation2010). This decision provoked strong controversy, and project opponents objected in another court, starting a vicious cycle of court cases, seemingly without end. Project opponents claim that the location of the lixiviation area, in a zone designated for aquifer recharge according to this decree, besides being illegal, poses an extra threat of contamination of the aquifer (BOF, Citation2014).

Conflict over decision-making authority

As explained, MSX used a provision within the Mining Law that allows “temporary occupancy” of the land to acquire usufruct rights. This was granted by the Ministry of Economy in 2005, and thus the ejidatarios’ rights to land and water were circumvented. Temporary occupancy has given birth to a much deeper discussion about the contents of the laws, how they interact and who has legal and/or legitimate power. In this case, the Mining Law was given preference over the Agricultural Law, but a large litigation process started, contesting the decision-making power of Mexico’s courts: who is to decide whether the Mining Law supersedes Agricultural Law, or otherwise? This discussion is profoundly connected to power positions, discourse and knowledge, discussed in the fourth echelon.

Similar disputes relate to decision-making authority regarding the three decrees that have been issued in the past (zona de monumentos, zona de veda and zona de preservación de vida silvestre), which all have been overthrown in favour of mining activity. They were intended to protect the region socio-environmentally and culturally, but recent political power plays have altered and generated reinterpretation of the decrees with the aim of welcoming MSX to the area. However, the authority to overthrow these decrees (varying from the state governor to the national government) is fiercely disputed in the courts. BOF is actively fighting the decisions taken by authorities. BOF member Eduardo da Silva said, “Even when MSX leaves Cerro de San Pedro, our job is not done. There are so many other places in which the same thing is going on. We are not just questioning MSX, but equally the Mexican government: eventually, the government is the one who allows the law to be broken. Our goal is to change this governmental system, full of corruption, and to change the laws and the legal system that make it possible for companies such as MSX to operate in the illegal way they currently are” (pers. comm., October 2013).

The long legal battle and the different courts’ rejecting responsibility and consequently referring to other courts have enabled MSX to continue operating while court cases remained pending. Several members of BOF mentioned that they feel that the Mexican government has deliberately adopted a ‘from pillar to post’ strategy of rejecting responsibility and referring to other courts, to postpone decision making and meanwhile give MSX the chance to operate (pers. comm., BOF member Eduardo da Silva, October 2013). Herman (Citation2010, p. 85), quotes BOF’s lawyer Esteban in her research on Cerro de San Pedro: “The legal processes are so poorly managed and the regulations are so vague that there are lots of ambiguities around the Agrarian Registry.… So the ejidatarios are not only against the mine, they’re also litigating so that the courts recognize their rights.”

International legislation has also put its mark on developments in Cerro de San Pedro, and brings up the question of which type of legislation (national or international) supersedes the other. Through NAFTA’s Chapter 11, a foreign company may sue the host government, if it considers that the latter has not complied with agreements made under NAFTA, and thus put the company economically at a disadvantage. As UN’s principal water lawyer, Miguel Solanes, writes about NAFTA and its threats to the public interest: “There is a tendency to replace the obligatory jurisdiction of the State with that of international arbitration tribunals.… Two types of economic players are thus created: those having all manner of guarantees, whatever the fluctuations in the economy, and those, usually ordinary citizens, who do not have any” (Solanes & Jouravlev, Citation2006, p. 63; see also Solanes & Jouravlev, Citation2007). In Mexican practice, on several occasions, local and national governments were sued by companies over the revocation or cancellation of environmental permits, after which the companies received large compensations for their economic loss from the host government (e.g. Kass & McCarrol, Citation2000). Solanes explains: “Only investors have legitimacy to request the intervention of investment arbitration courts, and to initiate suits and legal actions. They create the arbitration market, which depends on investors for its existence – the risk of capture and bias is strong. Since they are based on international agreements, investment courts trump national jurisdiction. In addition, other fora such as human rights courts lack the enforcement powers of the decisions of arbitration courts” (pers. comm., 20 December 2014).

MSX has threatened the Mexican government with NAFTA Chapter 11 to obtain the required permits at a time when the process seemed very difficult. Similar to the observation made by Warden and Jeremic (Citation2007), just the threat of use of this provision has already caused a strong chilling effect in the case of Cerro de San Pedro. NAFTA provides an enormously powerful position for MSX vis-à-vis the national and local governmental authorities. Local communities are not allowed to object to resolutions taken within NAFTA, even though they often are the ones facing the greatest impact. Denying local inhabitants and communities the ability to file a complaint under NAFTA repudiates their legal status and stake in the conflict. As in Cerro de San Pedro, this creates enormous power differences between the local inhabitants versus the foreign company (Ochoa, Citation2006). As Miguel Solanes comments: “International investment agreements and their arbitration courts have made a travesty of local interests and power devolution. An arbitration court, at the international level, beyond local and national judges, ends up adjudicating conflicts between public local interests and global companies and investors. The international investment court does not only perform beyond local reach, but also outside the limits of public interest at the local level. Its mandate is to protect investors’ interests, disregarding local problems” (pers. comm., 20 December 2014).

Conflicts among discourses

MSX’s discourse is an essential tool in reaching its objectives, and helps understand how the issues explained in the previous echelons were tackled. The Cerro de San Pedro case witnesses how the mine’s powerful discursive practices aim to morally, institutionally and politically legitimize their particular interests in using, managing and usurping the local natural resources, thereby arranging the human, the technological and the natural worlds in a ‘convenient miningscape’, as if these bonds were entirely natural.

Under its Corporate Social Responsibility programme, MSX claims that the company is deeply concerned with the environment, health, safety, and community development in both social and economic terms (Herman, Citation2010; Newgold Inc., Citation2012a). MSX states that it will provide jobs, education, healthcare and infrastructure to the local residents. On top of that, MSX claims to work with the newest techniques in order to minimize impact on the environment and reduce chances of contamination. Work and safety standards at work are said to be high; the wages that the mine offers would be high compared to Mexican standards (Newgold Inc., Citation2012b). The company’s discourse explains that MSX is genuinely concerned with the livelihoods of its employees. By strongly advocating their commitment to security, health, environment and sustainability, MSX creates a discursive link between large-scale open-pit mining and positive development of the area. For example, MSX’s annual Sustainability Report focuses largely on the job opportunities that MSX created for local inhabitants and on MSX’s community development support, e.g. by means of the development of alternative income sources such as cactus nurseries, fish farms and a supply of microcredit for entrepreneurial initiatives to enable the people to sustain themselves after MSX abandons operation (pers. comm., MSX representative, November 2013; Newgold Inc., Citation2012b). By obtaining internationally recognized certificates confirming their ‘sustainable operation strategy’, such as the Conflict-Free Gold Certificate, MSX aims to comfort the public and government when it comes to health, society, environment and pollution (see also Vos & Boelens, Citation2014).

In many of its social activities – such as collective tree-planting days, the museum in Cerro de San Pedro in which the mining operation is explained and the ‘benefit’ for the local community is emphasized, and workshops on the production of silver jewellery – the company combines its strong power position with the creation of particular mine-convenient knowledge and facts, to make its mining truths become locally accepted truth. MSX has a very powerful position in this sense: it uses its economic position to influence public (e.g. mass-media) and governmental opinion, enhancing its social and political power position. Knowledge is actively created by MSX, as the company itself is in charge of monitoring the quality of water, air and soil. Thus, MSX establishes firm, triangular linkages between the three fundamental elements of Foucauldian discourse – power, knowledge and truth – mutually linked and shaping each other.

While some of the inhabitants have been convinced and have adopted the discourse of the mine’s important economic, social and even environmental function for the region, others (for example those united in the BOF) have developed critiques and alternative or counter-discourses. BOF’s mission is to stop MSX’s activity in Cerro de San Pedro. To reach this, BOF actively spreads information in newspapers, social media and other outlets about the litigation process and the adverse environmental, cultural and economic effects caused by MSX, and organizes a yearly anti-mine music festival that takes place in Cerro de San Pedro.

Clearly, analyzing mining discourses and counter-discourses in Cerro de San Pedro gives insight into how the different groups perceive environmental problems and design solutions. Guthman (Citation1997, p. 45) notes that the “production of environmental interventions is intimately connected to the production of environmental knowledge, both of which are intrinsically bound up with power relations. Therefore, the facts about environmental deterioration have become subordinate to the broader debates on the politics of resource use and sustainable development.” Many villagers perceive that the process of knowledge production by the mining company, consultants, and state agencies reflects but also reinforces social and economic inequities in the area.

In everyday life, the discursive struggles and conflicts in the region – together with the diverging interests of villagers in relation to the mine’s operations – have fuelled the divide-and-rule strategy that MSX has applied to the villagers since it arrived. When MSX came to Cerro de San Pedro, the village was unanimous in its objection to the mine. However, local inhabitants explain that the ambience in the village slowly changed and opinions on the mine started to diverge. For example, people say that certain families received money in return for their vote and others did not receive anything. The division between Cerro de San Pedro’s villagers came to an all-time high when several pro-MSX villagers attacked some anti-MSX villagers, with the anti-mine villagers just able to run for their lives. Effectively objecting to the presence of MSX is more difficult for the anti-mine villagers if opinion is divided, an asset cleverly used by MSX.

Ways forward

Mining conflicts as in Cerro de San Pedro show a common feature, typical of most cases in Latin America as well as in many other regions: mining companies’ power positions are reinforced by strong state backing and international investment agreement, producing a profoundly unequal negotiation position for the mining-affected populations. For the latter to obtain fairer and equal access to litigation possibilities, the mining company should be forced back to the negotiation table, and government institutions need to be made accountable for their key role as public service entities. To be successful, various cases provide evidence that this requires forging multi-actor alliances that work on multi-scalar levels, thus creating civil society networks that are internally complementary while connecting the local, national and global (see e.g. Bebbington, Humphreys-Bebbington, & Bury, Citation2010, and Boelens, Citation2008, for cases in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador; Ochoa, Citation2006, for México; Urkidi, Citation2010, for Chile; and Hoogesteger, Boelens, & Baud, Citation2016, for Ecuador). By linking, for example, local village initiatives, women’s groups, and journalists and newspapers with provincial indigenous and peasant federations, national ombudsman and civil rights offices, international research centres, and environmental and human rights NGOs, the negotiation forces (including access to research, information dissemination and possibilities for international arbitrage) can become more balanced and one-sided discourses can be challenged. Getches (Citation2010) describes important opportunities for these multi-actor networks to use international norms and laws that can counterbalance powerful NAFTA-type agreements (see also Solanes & Jouravlev, Citation2007). Thus, besides more localized first-echelon resource struggles, in particular for second- and third-echelon strategies, the marginalized mining-affected communities may find important support through multi-actor and multi-scalar network action. These can seek to bend discriminatory rules or apply (inter)national protective regulations, and to balance the currently skewed decision-making powers. At the fourth echelon of ERA, such multi-actor network strategies will also strengthen the building of an alternative discursive framework, one that enables challenging the ‘official’ regimes of representation and can generate broader support for socially and environmentally friendly alternatives.

Currently the leading mining opposition group in Cerro de San Pedro, the BOF, is working on proposals for a new Mining Law, which builds on a more equitable and ecologically sound management of land and water resources. Getting the Mexican government to accept this will require great lobbying skills, a large network of influential partners and a well-balanced discourse. To this end, BOF is forging an alliance of local, national and international environmental organizations and universities, such as Pro San Luis Ecológico, Greenpeace México, and Amnesty International. These alliances provide BOF with access to new strategic-political opportunities, not only in Cerro de San Pedro but also in other mining arenas in Mexico. In the Cerro de San Pedro case, in which extraction activity is almost at its final stages, the main effort is now to try to reduce the damage done to the environment. Demanding ethically and ecologically responsible mining practices and waste cleanup, and also enabling alternative local livelihood opportunities, such as ecological and cultural tourism, might improve future job opportunities for the villagers whilst reducing the environmental impact.

Conclusions

Making use of the ERA framework shows that this mining conflict goes beyond the obvious struggle over accessing or defending land and water resources. In Cerro de San Pedro, an exemplary struggle is being fought over land and water, yet with underlying struggles over the content of the rules and rights, and disputes regarding the decision-making authority to make those rules, which in the end seek to distribute the resources in particular ways. The discourses that are developed are not just weapons and counter-weapons in this struggle but also seek, in accordance with each party’s interests and worldviews, to convincingly answer the questions and coherently link the issues raised in the first three echelons. In Cerro de San Pedro, they aim to depoliticize and naturalize MSX’s miningscape, or, alternatively, show its profound contradictions as well as politically motivated ‘mining truth’, and arrange for ‘alternative truths’.

MSX obtained access to the ejido land through the consent of Mexican government institutions which, despite the lack of required permits, allowed MSX to proceed with its operations on communal land. Moreover, the position of ejidatarios vis-à-vis the powerful mining company is further weakened by the systemic legal contradictions between the Agricultural Law and the Mining Law. The possibility of a temporary occupancy that can overrule the ‘inalienable’ land titles of ejidos inherently means that in Cerro de San Pedro, and throughout the country, ejidos can and will be pushed aside in favour of mining companies. Also, NAFTA has had great influence on the litigation process and on the bargaining position of local inhabitants. NAFTA’s Chapter 11 gives foreign companies the opportunity to ignore national legislation concerning environmental and social rights and operate directly under the rules and regulations of NAFTA. NAFTA does not accept complaints from local inhabitants or communities, dismissing local communities’ co-decision-making about their own futures.

The decision to overrule the existing decrees (the veda-regulations and the zone for the environmental preservation) in favour of MSX shows the Mexican government’s eagerness for MSX to exploit the area. Although these decisions are contested by project opponents and remain to be decided in Mexico’s courts, the circumvention of these decrees shows the extent to which an international, powerful actor like MSX can influence execution of national environmental legislation. Linked to these decrees is the granting of water concessions to MSX. Governmental allocation of 1.3 MCM annually to a mining industry contrasts with the total lack of water in a few neighbouring villages, with the endangered provision of water quantity and quality to a large city like San Luis Potosí, and with the official argument that in this valley water is generally an extremely scarce resource for which veda restrictions need to be obeyed. Water-scarcity declarations in the region clearly refer to political statements and priorities, which in the power context of San Luis Potosi easily bypass the natural state of this resource. The government declares a state of water scarcity when villages claim subsistence water use, yet it can simultaneously declare water abundance when a multinational mining company asks for large volumes of water to produce metals and a toxic environment. The economic interests of the few prevail over ensuring that the mine’s neighbouring villages are provided with the most basic human right.

In the end, the changes in land and water rights in Cerro de San Pedro result from a complex interplay between different actors, where the court systems, officials and governments at diverse levels play a double and deeply troublesome role, and where multinational MSX has cleverly used the loopholes in the laws, plus its economic and discursive powers, to reach its objectives. In addition, international agreements as NAFTA have had a profound unethical impact on the litigation process, stimulating encroachment and sidelining social and environmental rights. The real victims of this interplay are the ejidatarios and inhabitants of Cerro de San Pedro, who have lost their alternative income-generating activities and access rights to land and water and who, once MSX abandons its operation, will be left without job opportunities, and with a polluted, entirely distorted environment.

Yet, the mine’s deeply problematic impact may be reduced and halted in the near future. Through multi-actor networks that creatively engage in multi-scale action, mining-affected population groups, together with a variety of mutually complementary advocacy and policy actors, are striving to balance negotiation power and force the mining company to clean up mining residues and enable alternative local livelihood opportunities.

Notes

1. Zona de veda: a specific area in which additional water use (on top of those concessions already granted) is not allowed; in short, new water concessions are no longer granted. This provision is designed to preserve the quantity and quality of the water, which can be either of superficial or subsurface nature (Conagua, Citation2012). However, the previously established amount of water for extraction may be so high as to prevent a healthy equilibrium from being reached. In the Valle de San Luis Potosí the veda refers to groundwater exploitation.

References

- Achterhuis, H., Boelens, R., & Zwarteveen, M. (2010). Water property relations and modern policy regimes: Neoliberal utopia and the disempowerment of collective action. In R. Boelens, D. Getches, & A. Guevara-Gil (Eds.), Out of the mainstream. water rights, politics and identity (pp. 27–55). London: Earthscan.

- Adler, R., Claassen, M., Godfrey, L., & Turton, A. R. (2007). Water, mining and waste: An historical and economic perspective on conflict management in South Africa. The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 2(2), 32–41. doi:10.15355/epsj.2.2.33

- Assies, W. (2008). Land tenure and tenure regimes in Mexico: An overview. Journal of Agrarian Change, 8(1), 33–63. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2007.00162.x

- Assies, W., & Duhau, E. (2009). Land tenure and tenure regimes in Mexico: An overview. In J. M. Ubink, A. J. Hoekema, & W. J. Assies (Eds.), Legalising land rights. Local practices, state responses and tenure security in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Bebbington, A., Humphreys-Bebbington, D., & Bury, J. (2010). Federating and defending: Water, territory and extraction in the Andes. In R. Boelens, D. Getches, & A. Guevara-Gil (Eds.), Out of the mainstream. Water rights, politics and identity (pp. 307–327). London: Earthscan.

- Boelens, R. (2008). Water rights arenas in the Andes: Upscaling Networks to strengthen local water control. Water Alternatives, 1(1), 48‐65.

- Boelens, R. (2009). The politics of disciplining water rights. Development and Change, 40(2), 307–331. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01516.x

- Boelens, R. (2014). Cultural politics and the hydrosocial cycle: Water, power and identity in the Andean highlands. Geoforum, 57, 234–247. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.02.008

- Boelens, R. (2015). Water, power and identity. The cultural politics of water in the andes. London and Washington DC: Routledge/Earthscan.

- Boelens, R., & Vos, J. (2012). The danger of naturalizing water policy concepts: Water productivity and efficiency discourses from field irrigation to virtual water trade. Journal of Agricultural Water Management, 108, 16–26. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2011.06.013

- BOF. (2013). Website of BOF (Broad Opposition Front). Retrieved July 9th, 2013, from http://faoantimsx.blogspot.mx/

- BOF. (2014, April 5th). Carta a Carmen Aristegui. Retrieved October 23th, 2014, from http://faoantimsx.blogspot.mx/2014/04/carta-carmen-aristegui.html

- Bricker, K. (2009). Chiapas Anti-Mining Organizer Murdered. Retrieved April 8th, 2014, from http://narcosphere.narconews.com/notebook/kristin-bricker/2009/12/chiapas-anti-mining-organizer-murdered

- Brooks, D. B., Thompson, L., & El Fattal, L. (2007). Water demand management in the Middle East and North Africa: Observations from the IDRC forums and lessons for the future. Water International, 32(2), 193–204. doi:10.1080/02508060708692200

- Brooks, D. B., Trottier, J., & Doliner, L. (2013). Changing the nature of transboundary water agreements: The Israeli–Palestinian case. Water International, 38(6), 671–686. doi:10.1080/02508060.2013.810038

- Clark, T. (2003). Canadian mining companies in Latin America: Community rights and corporate responsibility. Paper Conference CERLAC/York University and Mining Watch Canada, May 9 - 11, 2002, Toronto.

- Conagua. (2004). Registro publico de derechos de agua. Retrieved March 25, 2014, from http://www.conagua.gob.mx/Repda.aspx?n1=5&n2=37&n3=115

- Conagua. (2012). Vedas Superficiales. Retrieved March 25, 2014, from http://www.conagua.gob.mx/ConsultaInformacion.aspx?n1=3&n2=63&n3=210&n0=1

- Duarte-Abadía, B., Boelens, R., & Roa-Avendaño, T. (2015). Hydropower, encroachment and the repatterning of hydrosocial territory: The case of Hidrosogamoso in Colombia. Human Organization, 74(3), 243–254. doi:10.17730/0018-7259-74.3.243

- Estrada, A. C., & Hofbauer, H. (2001). Impactos de la inversión minera canadiense en México: Una primera aproximación. México, DF: Fundar, Centro de Análisis e Investigación.

- Feindt, P. H., & Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 161–173. doi:10.1080/15239080500339638

- Forsyth, T. (2003). Critical political ecology: The politics of environmental science. London: Routledge.

- GAES Consultancy. (2007). Mexico - mexican market profile mining. Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Trade.

- Getches, D. (2010). Using international law to assert indigenous water rights. In R. Boelens, D. Getches, & A. Guevara-Gil (Eds.), Out of the mainstream. Water rights, politics and identity. London: Earthscan.

- Gordoa, S. E. M. (2011). Conflictos socio-ambientales ocasionados por la minería de tajo a cielo abierto en Cerro de San Pedro, San Luis Potosí. (Licenciatura en Geografia). San Luis Potosí: Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí.

- Guthman, J. (1997). Representing crisis: The theory of himalayan environmental degradation and the project of development in Post-Rana Nepal. Development and Change, 28(1), 45–69. doi:10.1111/dech.1997.28.issue-1

- Hajer, M. (1993). Discourse coalitions and the institutionalization of practice: The case of acid rain in Great Britain. In F. Fischer & J. Forester (Eds.), The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning (pp. 43–76). Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Herman, T. (2010). Extracting Consent or Engineering Support? An institutional ethnography of mining, “community support” and land acquisition in Cerro de San Pedro. Mexico: Department of Studies in Policy and Practice, University of Victoria.

- Hogenboom, B. (1998). Mexico and the NAFTA environment debate. The transnational politics of economic integration. Utrecht: International Books.

- Hogenboom, B. (2012). Depoliticized and repoliticized minerals in Latin America. Journal of Developing Societies, 28(2), 133–158. doi:10.1177/0169796X12448755

- Hoogesteger, J., Boelens, R., & Baud, M. (2016). Territorial pluralism: water users’ multi-scalar struggles against state ordering in Ecuador’s highlands. Water International, 41(1), 91–106. doi:10.1080/02508060.2016.1130910

- Kass, S. L., & McCarrol, J. M. (2000). The ‘Metalclad’ Decision Under NAFTA’s Chapter 11. New York Law Journal. Environmental Law. Retrieved 27 April 2014, from http://www.clm.com/pubs/pub-990359_1.html

- Krueger, A. O. (1999). Trade creation and trade diversion under NAFTA. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Lutz, D. (2010). Beware of the smell of bitter almonds. Newsroom. Retrieved July 23, 2014, from http://news.wustl.edu/news/Pages/20916.aspx

- Mann, H., & Von Moltke, K. (1999). NAFTA’s Chapter 11 and the environment. Addressing the impacts of the investor-state process on the environment. Winnipeg, Manitoba: International Institute for Sustainable Development.

- Martínez-Alier, J. M. (2003). The environmentalism of the poor: A study of ecological conflicts and valuation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Neumann, R. P. (2005). Making political ecology. London: Hodder Arnold.

- Newgold Inc. (2009). Manifesto de impacto ambiental. Modalidad regional unidad minera Cerro de San Pedro - Operación y Desarrollo. Cerro de San Pedro, San Luis Potosí: Minera San Xavier S.A.

- Newgold Inc. (2012a). Mining Project in Cerro de San Pedro. Retrieved 9 July, 2013, from http://www.newgold.com/properties/operations/cerro-san-pedro/default.aspx

- Newgold Inc. (2012b). Reporte de Sustentabilidad 2012. Cerro de San Pedro.

- Nogales. (2002). The NAFTA environmental framework, Chapter 11 investment provisions, and the environment. Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law, 8(1), 6.

- Ochoa, E. (2006). Canadian mining operations in Mexico. In L. North, T. D. Clark, & V. Patroni (Eds.), Community rights and corporate responsibility: Canadian mining and oil companies in Latin America (pp. 143–160). Toronto: Between the Lines.

- OCMAL. (2014). Conflictos Mineros en México. Retrieved April 18, 2014, www.ocmal.com

- Peace Brigades Internacionales. (2011). Undermining the Land. The defense of community rights and the environment in Mexico. Mexico Project Newsletter. London.

- Peet, R., & Watts, M. (1996). Liberation ecologies: Environment, development and social movements. New York: Routledge Press.

- Peña, F., & Herrera, E. (2008a). El litigio de Minera San Xavier: Una cronología. In M. C. Costero-Garbarino (Ed.), Internacionalización económica, historia y conflicto ambiental en la minería. El caso de Minera San Xavier. San Luis Potosí: COLSAN.

- Peña, F., & Herrera, E. (2008b). Vocaciones y riesgos de un territorio en litigio. Actores, representaciones sociales y argumentos frente a la Minera San Xavier. In M. C. Costero-Garbarino (Ed.), Internacionalización económica, historia y conflicto ambiental en la minería. El caso de Minera San Xavier. San Luis Potosí: COLSAN.

- Perreault, T. (ed.), (2014). Minería, Agua y Justicia Social en los Andes. Experiencias Comparativas de Perú y Bolivia. Justica Hídrica. Cusco: CBC.

- Rabinow, P. (1991). The foucault reader. London: Penguin.

- Ramirez, M. D. (2003). Mexico under NAFTA: A critical assessment. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 43(5), 863–892. doi:10.1016/S1062-9769(03)00052-8

- Reygadas, P., & Reyna Jiménez, O. F. (2008). La batalla por San Luis: ¿El agua o el oro? La disputa argumentativa contra la Minera San Xavier. Estudios Demograficos Y Urbanos, 23(2 (68)), 299–331.

- Reyna Jiménez, O. F. (2009). Oro por cianuro: Arenas políticas y conflicto socioambiental en el caso Minera San Xavier en Cerro de San Pedro. San Luis Potosí: COLSAN.

- Robbins, P. (2004). Political ecology: A critical introduction. Chichester: Wiley.

- Sandt, J. van der (2009). Mining conflicts and indigenous Peoples in Guatemala. The Hague: Cordaid.

- Santacruz De Leon, G. (2008). La minería de oro como problema ambiental: El caso de Minera San Xavier. In M. C. Costero-Garbarino (Ed.), Internacionalización económica, hierstoia y conficto ambiental en la minería. El caso de Minera San Xavier. San Luis Potosí: COLSAN.

- Solanes, M., & Jouravlev, A. (2006). Water governance for development and sustainability. Santiago: UN/ECLAC.

- Solanes, M., & Jouravlev, A. (2007). Revisiting privatization, foreign investment, international arbitration, and water. Santiago: UN/ECLAC.

- Sosa, M., & Zwarteveen, M. (2011). Acumulación a través del despojo: el caso de la gran minería en Cajamarca. In R. Boelens, L. Cremers, & M. Zwarteveen (Eds.), Justicia Hídrica: Acumulación, Conflicto y Acción Social. (pp. 381–392). Lima: IEP.

- Turton, A. R. (2010). The politics of water and mining in South Africa. In K. Wegerich & J. Warner (Eds.), The politics of water: A survey. London: Routledge.

- Turton, A. R., & Funke, N. (2008). Hydro-hegemony in the context of the orange river basin. Water Policy, 10(S2), 51–70. doi:10.2166/wp.2008.207

- Urkidi, L. (2010). A glocal environmental movement against gold mining: Pascua-Lama in Chile. Ecological Economics, 70, 219–227. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.05.004

- Vargaz-Hernandez, J. G. (2006). Cooperacion y conflicto entre empresas, comunidades, nuevos movimientos sociales y el papel del gobierno. El caso de Cerro de San Pedro.

- Vos, H. de, Boelens, R., & Bustamante, R. (2006). Formal law and local water control in the andean region: A fiercely contested field. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 22(1), 37–48. doi:10.1080/07900620500405049

- Vos, J., & Boelens, R. (2014). Sustainability standards and the water question. Development and Change, 45(2), 205–230. doi:10.1111/dech.12083

- Warden, R., & Jeremic, R. (2007). The Cerro de San Pedro case. A clarion call for binding legislation of Canadian corporate activity abroad. Toronto: KAIROS.

- Wilder, M. (2010). Water governance in Mexico: Political and economic apertures and a shifting state-citizen relationship. Ecology and Society, 15(2), 22.

- Wilder, M., & Romero-Lankao, P. (2006). Paradoxes of decentralization: Water reform and social implications in Mexico. World Development, 34(11), 1977–1995. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.026

- Yacoub, C., Duarte-Abadía, B., & Boelens, R. (2015). Agua y Ecología Política. El extractivismo en la agro-exportación, la minería y las hidroeléctricas en Latino América. Justicia Hídrica. Quito: Abya-Yala.

- Zwarteveen, M. Z., & Boelens, R. A. (2014). Defining, researching and struggling for water justice: Some conceptual building blocks for research and action. Water International, 39(2), 143–158. doi:10.1080/02508060.2014.891168