ABSTRACT

Characterizing subcultural models of tap water derived from interviews from 154 respondents in four neighbourhoods in the urban Southwestern United States, we identify sources of public discourses that support and anticipate passive elite capture. In accord with predictions, social devaluation of those who use tap water is situated with residents of a privileged exclusive community sector. This suggests the value of a broader conceptualization and an empirical model of elite capture in water resources: not just as a physical deviation of resources, but also as a discursive devaluation of public resources by specifically elite populations.

Introduction

In many high-income countries in the Global North, the universal provision of a networked water supply is a valued social norm and public good (Meehan, Citation2020). In this paper we lay the groundwork for arguing that elite capture – as a form of corruption in advanced capitalism –not only may entail the physical deviation of public resources, but also may include a discursive devaluation and stigmatization of public resources by elite populations. We have two interrelated aims. First, we seek to establish an empirical basis for cultural models of tap water, drawing on survey research with residents in four socioeconomically different communities in the Phoenix metropolitan area of Arizona, USA. Specifically, we seek: (1) to identify any low-prestige or stigmatizing cultural models associated with drinking water, in particular municipal tap water; (2) to connect negative social valence to tap water and stigmatized attachments to particular people; and (3) to interpret these findings in relation to a critical discourse of ‘passive’ elite capture.

Second, we build on critical approaches to corruption and state power (Doshi & Ranganathan, Citation2019) to elaborate a potential conceptual understanding of elite capture as a passive and discursive process – one that pivots on the social stigmatization of public goods and users. To understand empirically how elite capture may work as a passive and discursive process, we investigate the ways that people cognitively connect different drinking waters to different social factors beyond access, cost, and convenience. For example, do people view the use of different types of water – such as municipal tap water, harvested rainwater or different brands of bottled water – as indicative of different social or moral attributes? Exposing possible cognitive processes and valuations of different types of water sheds light not only on the how people may use certain types of water to mark prestige and social status in a Bordieuan sense, but also on how non-avoidance of tap water might in itself mark or maintain low social standing and social divisions. In understanding empirically how people value or stigmatize different types of water, we hope to illuminate the possibility of less visible and more nefarious contradictions within processes of elite capture – the discourses that fuel a rhetoric of public decay amid material gains by privileged classes. And to begin, we develop this framework by linking critical approaches to elite capture with a different set of anthropological scholarship on social devaluation and stigma.

Linking elite capture and social devaluation

Corruption is typically framed as a set of deviant practices from an idealized norm of democracy and Western liberal capitalism – a one-word ‘explanation’ for backwardness and underdevelopment in the Global South (Doshi & Ranganathan, Citation2019). For example, the informalized urban poor have long been framed and denigrated as ‘corrupt’ by upper classes (Björkman, Citation2014), including which kinds of ‘informal’ water access count as legitimate and which require punitive measures and criminalization (Meehan, Citation2013). Recent efforts to reframe corruption as a shifting and subjective discourse – centred on the abuse of entrusted power (Doshi & Ranganathan, Citation2019) – provides a framework to situate social devaluation and stigma in relation to state power. In contrast to mainstream definitions of corruption as a ‘fixed and measurable set of practices, such as a bribery and nepotism’, Doshi and Ranganathan (Citation2019, p. 451) theorize corruption as ‘an ever-changing evaluative frame used to indict various configurations and abuses of entrenched power’. Their approach releases corruption from a list of predefined offences and focuses attention on the historical, geographically contingent power relations that produce a state of ‘corruption’. As they argue, ‘[w]hat makes corruption interesting is not so much the “truth” of its existence, but the different formations of power it implicates, the contradictory worldviews it expresses, and the actions it motivates’ (p. 437).

Contradiction is at the heart of corruption (Gupta, Citation1995). Furthermore, Doshi and Ranganathan (Citation2019) suggest that the contradictions and incongruencies expressed by research participants – such as the idea that tap water is ‘dirty’ or ‘low class’ even though elites benefit from universal service – may reflect broader social dynamics about class, power and the state in ways that are not immediately evident. Indeed, ‘corruption’s meanings shift across time and context, and how talk of corruption by research subjects symbolizes deeper malaise about the interpenetrations between the state and society and public and private life, even if it is used in highly contradictory ways’ (p. 441). Key to this definition is the idea that corruption is ‘normative discourse’ about the abuse of entrusted power and consequent social decay (p. 438) – including, in our case, the ‘decay’ of municipal tap water.

In this paper we explore such contradictions through the lens of tap water and stigma. Specifically, our goal is to lay the groundwork for extending the notion of elite capture beyond its traditional use. Elite capture is conventionally defined as a form of corruption – or territorialized power – whereby public resources are biased for the benefit of elite individuals in detriment to the welfare of the larger population. This form of corruption occurs when elites actively use public funds, originally intended to be invested in services that benefit the larger population, to fund projects that benefit high-status individuals and their networks. However, following Doshi and Ranganathan’s (Citation2019) argument that corruption is not just a set of practices but also a set of discursive processes that serve to shift public discourse and opinion, we suggest that processes of elite capture may also occur discursively and manifest in more subtle ways in which elite populations seek to devalue and stigmatize public goods with the goal of mobilizing the public undesirability of such goods to their own advantage. But to understand empirically whether or not such processes may be happening, we first must understand how people conceptualize the values and moral underpinnings of public goods (such as municipal tap water) and if these valuations differ across populations of different social standing. If we can empirically demonstrate negative or stigmatized valuations of public goods among elite populations, then we can more confidently assert that elite capture may be occurring in subtle and discursive ways.

To understand how people may cognitively connect desirability (or undesirability) and prestige (or stigma) to a public good such as municipal tap water, we turn a different literature in which anthropologists examine how people leverage consumption (including of bottled waters) to inscribe and re-inscribe class and other social distinctions in a dynamic and unequal economy. This body of work shows that people mobilize certain consumptive practices – such as drinking the ‘right’ brand of bottled water – to demonstrate their ‘refinement’ and ‘good taste’ (Biro, Citation2019; Wilk, Citation2006). Of course, bottled water companies are also well aware that water-prestige associations (as the opposite of stigma) both exist and can be created, and supply and market products accordingly. But anthropological literature on consumption as prestige suggests the possibility of another possible dimension of tap water aversion by implication – that consumption of some socially undesirable items will be avoided if people identify them as potentially socially devaluing of the person consuming (Hadley et al., Citation2019; Weaver et al., Citation2014). By social undesirability of tap water, here we mean its association with devalued social characteristics, including possibly social identities that are stigmatized and discriminated against. If what people consume can both elevate and mark high social prestige, it can also denigrate and mark low social standing.

Stigma is a pernicious social process in that it devalues not just a set of undesirable behaviours (say drinking tap water) but also the people who are seen as engaging in them; this is done by attaching moral meanings (say ‘poor’, ‘lazy’ or ‘ignorant’) to the behaviour (Brewis & Wutich, Citation2019). Put simply, we suggest the social devaluation of tap water – and its clear attachment to stigmatized people and places – may exist as a discursive practice that serves to shift perceptions, beliefs, rhetoric, norms and practices surrounding the use of public goods, such as municipal tap water, which could allow elite populations to redirect those goods, or the funds used to finance those goods, for their own use. In doing so, no laws are explicitly broken; nonetheless, the social identification of municipal tap water as ‘poor quality’ reflects a particular set of state–society relations in late capitalist societies. Yet, there has been little scholarly effort to date to identify this potential form of elite capture.

Research context and methodology

In the United States, tap water is generally considered safe and reliable by public health standards. Yet, even when tap water is safe and accessible, many citizens elect to treat it, or avoid it in favour of (more expensive) commercially bottled water. For example, an analysis of NHANES data for the period 2011–14 found that 44.1% of adults drank tap water and 27.2% drank bottled water (the rest drank non-water items such as soda or juice) (Rosinger et al., Citation2018). Factors that correlate to bottled water preferences include perceptions of water safety and quality, taste, the perception of health-giving qualities, cost, convenience, location, and access (Prasetiawan et al., Citation2017; Rosinger et al., Citation2018). These factors appear to differ by socioeconomics. For example, wealthier drinkers might cite convenience as a reason for drinking bottled water, whereas less wealthy drinkers might cite safety or lack of access (e.g., Pierce & Gonzalez, Citation2017). Prior studies of water perceptions in urban Phoenix in Arizona (our study site), using comparable methods from cognitive anthropology, have shown that residents perceive tap water as dirty, hard, nasty and unpleasant in taste – a perception shared across neighbourhoods (Gartin et al., Citation2010). Avoidance of tap water (by drinking bottled water) is also widely reported as a strategy employed by those who could afford it (York et al., Citation2011).

Public trust of tap water is geographically uneven. Studies, such as Fragkou and McEvoy (Citation2016) in Georgia, USA, have shown that distrust predicts the non-use of untreated tap water. Low trust in municipal water providers can fuel a higher reliance on bottled water (Anadu & Harding, Citation2000). This lack of trust can be embedded in recent or longer term histories of injustices towards lower income, marginalized or minoritized communities (Meehan, Citation2020). After the Flint water crisis, for example, tap water avoidance in affected communities increased – but most especially among Latinx, Black and lower socioeconomic households (Rosinger & Young, Citation2020). Accordingly, distrust around tap water, and so the decision to use tap water, must always be contextualized in relation to class and other political–economic dynamics (Meehan, Citation2020). Phoenix also exhibits these socioeconomic qualities, making it a suitable location to investigate variance in attitudes and values associated with municipal tap water.

Our operational approach is rooted in methods from cognitive anthropology that identify cultural differences and consensus between groups. The assumption is that people within an interacting community (e.g., a delimited urban neighbourhood) share cultural values that are distinctive and different, and researchers can capture these nuances by sampling any set of 25 or more members of a defined community through convenience sampling (Handwerker & Wozniak, Citation1997). Because cultural differences should be shared in a population, random versus convenience sampling is not central to the design. Ranking and vignettes are two techniques used by cognitive anthropologists to determine what beliefs are shared within groups and so meet the measurable definition of cultural phenomena. This approach also begins with the assumption that communities may have more than one set of values around the low/high prestige of water, meaning different groups may understand and organize what is ideal or desirable differently; these are sometimes referred to as ‘subcultural’ models (Henderson & Dressler, Citation2017; Hruschka et al., Citation2008). This approach can also test for subcultural models that might exist across neighbourhoods: beliefs patterned by gender or age cohort are one common example of this. For a detailed explanation of this cognitive approach to culture as consensus and how it relates to sampling and data analysis, see Dressler (Citation2017, Citation2020), Weller (Citation2007) and Hruschka et al. (Citation2008).

Study sample

For this study, we selected four different field sites within the Phoenix metropolitan area to capture geographical and socioeconomic diversity. Each sample site was defined by the boundaries of relevant neighbourhood zip-codes; we recruited participants in public places using convenience sampling (). Interviews were conducted in all four sites by trained field assistants. We sought to recruit enough respondents in each site to exceed the minimum sample sizes required for (1) extracting and comparing subcultural models from closed-ended survey responses (n ~ 24 per site) (Weller, Citation2007); and (2) identifying and comparing themes and meta-themes in open-ended (qualitative) data (n = 10–12 per site) (Guest et al., Citation2006; Hagaman & Wutich, Citation2017; Weller et al., Citation2018). This resulted in a completed sample of 154 respondents. Informed consent oversight was provided by the Institutional Review Board of Arizona State University.

Table 1. Sample size, sites, and subsample characteristics

Data collection

Water prestige ranking exercise

Each respondent completed a ranking exercise. They were presented with 20 shuffled cards, each labelled with one of 12 water items or eight other beverages (). In the first step, candidate items were initially identified with a convenience sample of 67 people selected to have varied demographics, asking them to free-list types of water they wanted and did not want to drink, and two water technology experts. This list was then reduced using cognitive interviewing in pilots in the ranking exercise, with a focus on removing highly similar items, and selecting final labels in using terms commonly used by participants themselves (e.g., ‘inner-city’).

Table 2. Items used in the ranking exercise

The interviewer then asked each respondent: ‘Please rank these 12 items in terms of how you think they would be ordered from most prestigious to least prestigious to be drinking. Put the ones you think rich and admired people drink at the top; put the one you think poor or powerless people would drink at the bottom.’ Cards were shuffled before presentation. For this analysis, we removed the non-water beverages and reranked the water items as 1–12, where 1 was the highest for rank on prestige and 12 was the lowest. Respondents were asked about ranking decisions using a cognitive interviewing approach (questioning of why they answered as they did) through the process.

Vignette response exercise

Each respondent then completed a vignette response exercise. We selected two generic line drawings of houses to reflect material wealth versus material poverty (). We piloted an array of tools, both photographic and line drawn, and found very simple line drawing with any context removed to be the least distracting to respondents so they could focus on the questions asked.

Figure 1. Line drawings of lower (top) and higher (bottom) material wealth homes used in the vignette elicitation

Respondents were randomly presented with the higher or lower material wealth house first. For each house they were asked to imagine the people who lived in the house and describe them. Prompts included ‘Who lives here?’, ‘What do they do?’ and ‘What is their social and economic situation?’. They were then asked to describe what kind(s) of water people within the house would drink. Such prompts included: ‘Where do they get their drinking water?’, ‘What is the quality of water in this house?’ and ‘Does everyone in the house drink the same water?’. Participants were also asked to rate the safety of the tap water consumed in the house and to locate the occupants of the house by social standing from 1 to 10 using the MacArthur scale of subjective social status (Singh-Manoux et al., Citation2003). The instructions said that people at the top (10) were the best off and had the most respect, while the people at the bottom (1) had the least respect, worst jobs or least money.

Survey

Each respondent also completed a survey that included demographics, questions about their own water use and socioeconomics. To establish socioeconomic status (SES) we used two approaches. In interviews, we asked for nearest cross-streets to their home and identified from census data the average household income of the four closest census block groups to the north, south, east and west of the main cross-streets. We also asked each respondent to locate themselves on the social standing ladder they used to characterize the houses in the vignette test (scale of 1–10 on how they compared with others in the city). This was taken as a self-perception of SES.

Analytical procedures

Ranking data

We used an item ranking exercise to identify how respondents understand and organize the prestige of different types of drinking water. This can assist with identifying which types of water might be seen as the lowest prestige or least desirable, and also clarify items of consensus and less agreement. Analysis explored the rankings of water types by prestige for 157 respondents. Our analysis used R to conduct principal components analysis with varimax rotation and Pearson’s correlation. We extracted and compared the first three factors. The factors are summaries of all individual responses, collapsed into representative responses.

Modelling of prestige rankings by demographics

We then used factor loadings derived from the ranking procedure with survey responses to test statistically if different potential subcultural models (factors) extracted in the ranking exercise correlate with demographics (neighbourhood, perceived social status, gender). Factor loadings show each respondent’s association with each of the identified subcultural models. An individual’s factor loading of 0.90 means their own views are highly positively correlated with the model (factor); 0.10 means it is little correlated; and −0.20 suggests it is negatively correlated. This helps us then identify if some subsamples, for example, people from wealthier neighbourhoods, are operating with different models of water prestige than others. In sum, this approach provides a basic test of localized or subcultural models of the negative social meanings of drinking waters.

Analysis of coded qualitative data

In the third analysis, we use coded open-ended structured interview responses elicited using a visualization of a wealthy and not wealthy household, combined with the same survey data, to test statistically if people cognitively connect specific types of water with very low social and economic standing. This allows us to test for both poverty (lack of wealth) and stigma (low moral standing) in cognitive associations people are expressing around the negative social meanings of drinking water from specific sources. It also allows us to test if there are differences in the moral attributions that are applied based on respondents’ wealth and perceived social status. For example, do people with high perceived social status judge those who drink certain forms of water more harshly?

Operationally, we developed a codebook to classify texts using four codes: low economic standing, low social standing, negative moral attributions, minoritized groups plus drinking water consumption (). Identifying negative social and moral attributions is the most analytically important because it can be used to index stigmatized responses (Brewis & Wutich, Citation2019), and hence identify is people are making cognitive connections (by co-occurrence in responses). After extensive pretesting, we assessed interrater reliability using Cohen’s kappa. These four codes had kappa = 1.0, indicating high reliability for all codes. In addition, we also coded responses based on how respondents classified the water types being drunk in the ‘wealthy house’ and ‘poor house’. These codes consisted of same 12 water types used for the ranking exercise. Qualitative data management was done using MAXQDA software, with codes applied to the open-ended responses on water consumption in the high and low wealth households at the level of the question response. Code counts for each respondent were then exported to SPSS for statistical analysis.

Table 3. Examples of codes classifying the lower economic, social and moral standing of house occupants

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS v26 and regression models were run in lm function in R (R Core Team, Citation2013), with alpha = 0.05. In the final analytic step, the structured interview responses were reviewed to yield exemplar statements that typify and contextualize the findings from the three prior analyses.

Results

Overall prestige rankings of water types

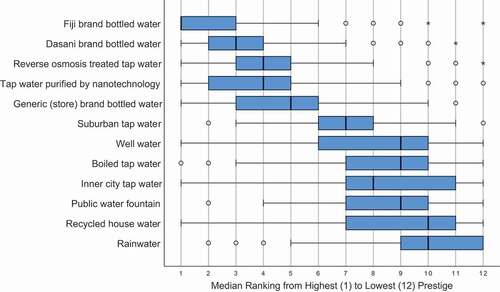

Considering all respondents together, median rank scores for branded bottled water (Fiji and Dasani) were highest for prestige of drinkers, followed by treated tap waters. Public fountain water and rainwater were ranked lowest (). Overall, additionally untreated tap water from any source was low ranked compared with bottled water from any source (including generic brand bottled water).

Cultural models of drinking water prestige

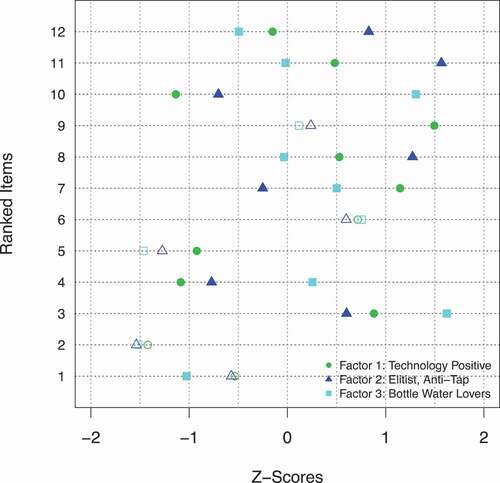

The analysis of the ranking data identified distinctions across the three extracted factors. The average z-scores for each item in each factor are shown in , and visually identify the relative prestige placement of the water types by prestige in each extracted subset of respondents (technology positive, elitist anti-tap, bottle water-lovers). The z-scores themselves are the weighted average of the scores that similar respondents gave to the 12 water types. These suggest how a hypothetical person representing a group of similar respondents (the factor) would rank the items. Similar z-scores across factors reflects consensus about the ranking of the item being considered.

Figure 3. Average z-scores from prestige ranking analysis. Filled markers indicate the distinctiveness of the factor for that item. For item key, see

The extracted cultural models (factors) suggest three slightly different potential underlying models of water prestige rankings (). All place Fiji brand bottled water high on prestige (< –1.4) and boiled tap water consistently fairly low on prestige (> 0.5). There was the most distinction across factors in the relative prestige of nanotechnology-treated tap water, reverse osmosis treated tap water, ‘inner city’ tap water and rainwater. Factor 1 rates self-captured water (well water and rainwater) as particularly low prestige, and technology treated water (nanotechnology and RO) as high prestige: we can term this a ‘technology-positive’ model. Factor 2 rates suburban, ‘inner city’ and public fountain tap water very low prestige, non-premier brand bottled water low prestige, and self-captured water relatively higher: we refer to this as an ‘elitist, anti-tap’ model. Factor 3 rates technology treated tap water (by reverse osmosis or nanotechnology) as lower prestige, and all types of bottled water as higher prestige: we can call this a ‘bottled water lover’ model.

Table 4. Average z-scores by three extracted factors, and consensus on item ranking across them

Demographic associations with different models

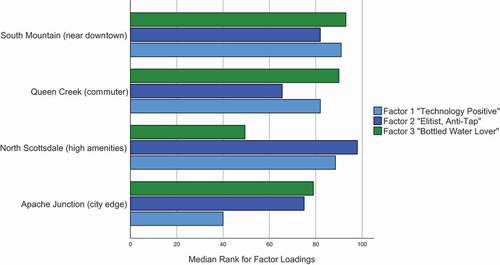

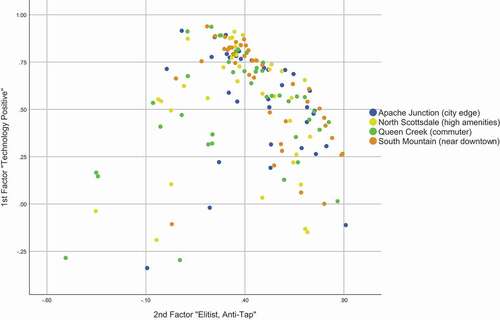

We then tested each individual’s factor loadings (extracted from the analysis of prestige rankings) against their demographics. The factor loading scores place each individual relative to that representative response. Higher factor loading scores reflect higher agreement with what other respondents believed. If the person did not agree with what was otherwise a widely agreed-upon idea, their loading would be very low. Relationship of individuals’ loadings on factors 1 and 2 by respondent site are shown in . Given our research questions, we were particularly interested in the profile of those with high loadings on factor 2, as this factor appeared to reflect a view containing lower prestige ranking of tap water.

Figure 4. Scatterplot of the bivariate relationships between an individual’s factor 1 and 2 scores, differentiated by site

Next, we ranked all individuals (1–154) for their loading scores on each factor and compared across the four study sites (). For factor 1 (‘technology positive’), the median rank was noticeably lower (i.e., less agreement with the model) for peri-rural Apache Junction. For factor 2 (‘elitist, anti-tap’), the median rank scores were highest in North Scottsdale. For factor 3 (‘bottled water lover’), median factor scores were noticeably lower in North Scottsdale.

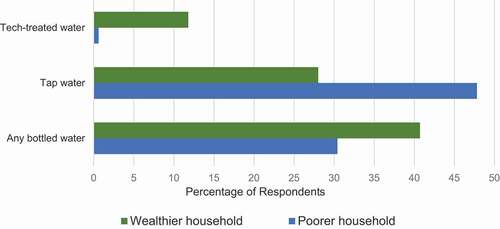

Figure 6. Percentage of respondents who identified people living in households as drinking water by type in open-ended question responses

We then used multiple regression to identify if neighbourhood income level, age, self-rated social standing or dummy variables for non-minoritized self-identified ethnicity or male gender varied with loadings on the three factors (as a test of individual agreement with each model) (). Overall, these tests yielded little additional useful information. For factor 1, lower self-assessed social standing was associated with higher loadings (p = 0.046, B = 0.04). For factor 2, male gender was associated with higher loading (p = 0.044, B = 0.09). Minoritized status, age and block income were not significant for any of the factors.

Table 5. Results of regression analysis testing the relationship between respondent demographics and factor loadings

Qualitative attribution of low status and drinking water source/type

Using the open-ended interview data, we then tested the pattern of codes assigned to question responses to identify association of tap water type/source with low economic status, social status and negative moral attributions. Percentage of respondents (by site) being coded as identifying specified markers based on their open-ended responses (). In response to the visual elicitations, tap water was more often mentioned in response to the poor house than the wealthier house, and bottled or technology-treated water was more often mentioned for the wealthier house ().

Table 6. Percentage of respondents attributing characteristics to imagined people in the visual vignettes of ‘wealthy house’ and ‘poor house’

In total, 44% of respondents associated tap water and low economic standing for the poor house prompt; none did for the rich house prompt. A total of 14.3% of respondents in all four locations identified tap water drinking and low social status together based on the poor house elicitation; only 0.6% (one person) did so for the wealthier house elicitation. Similarly, for negative moral attributions, 13% of respondents also mentioned tap water use in the poor house elicitation, while only one person did for the wealthier house. Considering distribution across all the sites, the percentages of association between tap water and low social status and negative moral attribution were higher in the two higher status neighbourhoods (Queen Creek and North Scottsdale). provides some exemplars of the ways people described these connections from the ‘poor house’ elicitation.

Table 7. Exemplars of statements about drinking water sources alongside assumed social standing in response to the poor house visual elicitation

Finally, using logistic regression, we then tested if individual respondent’s loadings on factor 2 (‘elitist, anti-tap’) from the ranking data were more likely to classify the ‘poor house’ residents as being tap water drinkers (where 1 = identified tap drinkers and 0 = did not). Higher loadings on factor 2 from the ranking dataset (with those with greater negative scores being the ‘elitists’) were significantly associated with identifying people in the poor households as drinking tap water (B = −1.293, SE = 0.640, p = 0.043). This confirms a meaningful concordance between the findings in the quantitative rankings data and that from the coding of qualitative open-ended interviews.

Discussion

Our empirical goal was to identify how people cognitively connect different types of drinking water to specific social and moral attributes in order to better understand shared social discourses about particular kinds of public infrastructure (municipal tap water) and people. Following what we know about discursive processes of corruption – that elite populations mobilize rhetoric of public decay to redirect funds intended for public services towards their own goals (Doshi & Ranganathan, Citation2019) – we were particularly keen to see if individuals in the elite population of our study sample were more likely to reflect cultural models that view municipal tap water as low prestige and/or stigmatizing, which may indicate a subtle and discursive process of elite capture.

Our research identified three clear cultural models of drinking water: the ‘technology positive’ model, the ‘elitist anti-tap’ model and the ‘bottled water lover’ model. All three models identified Fiji-brand bottled water as the most prestigious type of water, and all three models ranked boiled tap water as consistently low prestige. However, the ‘elitist anti-tap’ model most strongly reflected the idea that municipal tap water is low prestige and stigmatizing. Participants in this model ranked ‘inner-city’ and public fountain water as very low prestige, and identified self-captured water as having higher prestige. In sum, the ‘elitist anti-tap’ model reveals an interesting contradiction: respondents consistently ranked and degenerated ‘public’ tap water supply – and the people who use it – despite the fact that said elites universally relied on networked municipal service at home.

Moreover, our qualitative analysis showed that individuals who more closely adhere to the ‘elitist anti-tap’ model were significantly more likely to also identify poor households as drinking tap water. Again, our research shows the extent to which participants from different backgrounds share this discourse – in other words, indicate its hegemony. For example, our qualitative results showed that the majority of respondents across all research sites associated negative moral attributes on people identified as using tap water in poor households. Some examples include: ‘They are an indigent, low income, single parent household that is uneducated and potentially an immigrant,’ ‘They come from bad neighbourhoods where they have violence’ and ‘Probably just [drink] tap water, yucky tap water, smelly.’

Our most significant finding, however, is that we can connect this negative social valence and stigmatization of tap water to particular people in our study sample: specifically, respondents living North Scottsdale, a high-income community with a reputation for wealth, elitism, and exclusivity shared both within and beyond its borders (Wutich et al., Citation2014). This was reflected in what others from outside the area said. For example: ‘POSH!! Well dressed and smell good,’ and ‘clean water all the time. They pay people to make sure it is clean and good to use’. Taken together, these findings underscore a rhetoric of stigma and devaluation of public water infrastructure and users – a rhetoric that has the potential to be mobilized to justify the retrenchment of public goods.

Of course, based on our findings we cannot say that elite capture is happening in metropolitan Phoenix. Nonetheless, we have clearly established a discursive devaluation of public resources by specifically elite populations, as illustrated by the North Scottsdale ‘elitist anti-tap’ model. What this finding suggests is that the power dynamics inherent in elite capture – a model of active capture of public resources – maybe occurring in more subtle and passive ways that are difficult pin down in comparison to more conventional accounts of elite capture.

Following Doshi and Ranganathan (Citation2019), if we conceptualize ‘corruption’ as a discourse and practice of elite hegemony, then our findings clearly point to elite cultural models of stigmatization and devaluation of public resources – a nefarious form of power and control. Specifically, the North Scottsdale model most strongly associated state infrastructures (the municipal network) and people (tap water users) with negative moral attributions. Our findings suggest that elite capture may begin long before the ‘active’ process of capturing public resources for private benefit – here, the discursive construction of public water (and its drinkers) as ‘bad’ is a necessary precondition for elite control.

What are the implications of these findings? Two points are relevant for advancing insights about water insecurity and state–society relations. First, the elite model is shared across neighbourhoods and SES, indicating the pervasive influence of shared cultural norms and discourses, which circulate across Phoenix and are (re)produced by people of different backgrounds. Interestingly, the majority of research respondents across all sites ranked bottled water as having higher prestige than untreated public tap water. Furthermore, the majority of respondents across all sites associated branded bottled water use with wealthy households and untreated tap water with poor households. This finding points to an emerging discourse of private, prestige-branded bottled water (and its users) as ‘good water’ while stigmatizing the ‘bad’ public waters (and drinkers) of the municipal domain. Currently, this is not a focus in studies of perceptions of bottled water research (e.g., Rosinger et al., Citation2018). Just as discourses of water ‘scarcity’ are used in justifying the commodification and privatization of water (Bakker, Citation2014), we suggest that the ‘good/bad waters’ discourse found in our study serves to stigmatize public resources in way that maintains the structure of elite power – a population that has systematically benefitted from public water service. More research is needed to untangle the outcomes of elite discourses: such as the implications of this discourse in management practice – for example, do these shared norms lead to lower rates of public support and actual cases of municipal defunding or deregulation? – and how this rhetoric influences the ideas and values of tap water held by other populations and places.

Second, these findings underscore the necessity of a critical approach to water insecurity and elite power, in all its manifestations and locations. Corruption is about power relations and socio-spatial struggles in late capitalism (Doshi & Ranganathan, Citation2019); similarly, elite capture describes a form of ‘territorialized power’ with the potential to differentiate people and place through a deviation of public resources for private gain. What is being ‘captured’ in this particular case? As we show, elite cultural models of tap water serve to ‘normalize’ ideas of state failure (what economists call ‘market failure’), which may lay the groundwork for increased market-led rationale in water management (cf. Bakker, Citation2014). While it remains to be seen if this discourse can ‘capture’ broader public opinion or result in the actual deviation of resources, a broader discursive approach to elite capture – even in a passive sense – can nonetheless provide a useful lens into water struggles and power dynamics.

Conclusions

In this paper we have argued for a broader conceptualization and empirical model of elite capture in water resources, not just as a physical deviation of resources, but also a discursive devaluation of public resources by specifically elite populations, illustrated by the North Scottsdale ‘elitist anti-tap’ model. While corruption is often cited as a ‘driver’ of water problems worldwide, we have addressed the excessive attention given to corruption in water provision in the Global South by focusing on four Global North sites located in the Southwest United States. We examined elite capture as a possible discursive form of corruption in which people of high status disproportionately benefit from public resources. We introduced the concept of passive elite capture, in which elites devalue a public resource in ways that might facilitate its exploitation for their own benefit, as it pertains to tap water stigma. In eliciting the different cultural models of water, we demonstrated that the social devaluation and stigma of tap water is particularly associated with residents of a privileged exclusive community with the ‘elitist, anti-tap’ model, a finding in line with our predictions for passive elite capture.

Our results raise questions about the present and future of municipal tap water in other highly inequitable high-income economies (such as the United States), where similar dynamics of widening wealth gaps, declining tax bases, and the re-regulation of public functionaries and municipal infrastructures work to undermine the provision of universal water supply (Meehan, Citation2020). Our study suggests that elite populations may have a disproportionate role in facilitating discourses of ‘bad’, ‘low quality’ and ‘dirty’ stigma attached to vital public resources and, furthermore, people. These findings highlight the need for more critical research that identifies how corruption – as a hegemonic discourse, fuelled by active and also passive processes – works to undermine public water services in the Global North.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the PLUS Alliance’s support initiating their team’s collaboration. ASU global health students generously assisted with piloting and data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anadu, E. C., & Harding, A. K. (2000). Risk perception and bottled water use. American Water Works Association (AWWA), 92(11), 82–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1551-8833.2000.tb09051.x

- Bakker, K. (2014). The business of water: Market environmentalism in the water sector. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 39(1), 469–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-070312-132730

- Biro, A. (2019). Reading a water menu: Bottled water and the cultivation of taste. Journal of Consumer Culture, 19(2), 231–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517717779

- Björkman, L. (2014). ‘You can’t buy a vote’: Meanings of money in a Mumbai election. American Ethnologist, 41(4), 617–634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12101

- Brewis, A., & Wutich, A. (2019). Lazy, crazy, and disgusting: Stigma and the undoing of global health. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Doshi, S., & Ranganathan, M. (2019). Towards a critical geography of corruption and power in late capitalist. Progress in Human Geography, 43(3), 436–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517753070

- Dressler, W. W. (2017). Culture and the individual: Theory and method of cultural consonance. Routledge.

- Dressler, W. W. (2020). Cultural consensus and cultural consonance: Advancing a cognitive theory of culture. Field Methods, 32(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X20935599

- Fragkou, M. C., & McEvoy, J. (2016). Trust matters: Why augmenting water supplies via desalination may not overcome perceptual water scarcity. Desalination, 397, 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2016.06.007

- Gartin, M., Crona, B., Wutich, A., & Westerhoff, P. (2010). Urban ethnohydrology: Cultural knowledge of water quality and water management in a desert city. Ecology and Society, 15(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03808-150436

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Gupta, A. (1995). Blurred boundaries: The discourse of corruption. the culture of politics, and the imagined state. American Ethnologist, 22(2), 375–402. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1995.22.2.02a00090

- Hadley, C., Weaver, L. J., Tesema, F., & Tessema, F. (2019). Do people agree on what foods are prestigious? Evidence of a single, shared cultural model of food in urban Ethiopia and rural Brazil. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 58(2), 93–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2019.1566131

- Hagaman, A. K., & Wutich, A. (2017). How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on Guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Methods, 29(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16640447

- Handwerker, W. P., & Wozniak, D. F. (1997). Sampling strategies for the collection of cultural data: An extension of Boas’s answer to Galton’s problem. Current Anthropology, 38(5), 869–875. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/204675

- Henderson, N. L., & Dressler, W. W. (2017). Medical disease or moral defect? Stigma attribution and cultural models of addiction causality in a university population. Culture Medicine, and Psychiatry, 41(4), 480–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-017-9531-1

- Hruschka, D. J., Sibley, L. M., Kalim, N., & Edmonds, J. K. (2008). When there is more than one answer key: Cultural theories of postpartum hemorrhage in Matlab, Bangladesh. Field Methods, 20(4), 315–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X08321315

- Meehan, K. (2013). Disciplining de facto development: Water theft and hydrosocial order in Tijuana. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 31(2), 319–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/d20610

- Meehan, K., inter alia. (2020). Exposing the myths of household water insecurity in the Global North: A critical review. WIRES Water. forthcoming.

- Pierce, G. S., & Gonzalez, S. (2017). Mistrust at the tap? Factors contributing to public drinking water (mis)perception across US households. Water Policy, 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2016.143

- Prasetiawan, T., Nastiti, A., & Muntalif, B. S. (2017). ‘Bad’ piped water and other perceptual drivers of bottled water consumption in Indonesia. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 4(4), e1219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1219

- R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/

- Rosinger, A. Y., Herrick, K. A., Wutich, A. Y., Yoder, J. S., & Ogden, C. L. (2018). Disparities in plain, tap and bottled water consumption among US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2014. Public Health Nutrition, 21(8), 1455–1464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017004050

- Rosinger, A. Y., & Young, S. L. (2020). In–home tap water consumption trends changed among US children, but not adults, between 2007 and 2016. Water Resources Research, 56(7), e2020WR027657. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027657

- Singh-Manoux, A., Adler, N. E., & Marmot, M. G. (2003). Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine, 56(6), 1321–1333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00131-4

- Weaver, L. J., Meek, D., & Hadley, C. (2014). Exploring the role of culture in the link between mental health and food insecurity: A case study from Brazil. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 38(2), 250–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12055

- Weller, S. C. (2007). Cultural consensus theory: Applications and frequently asked questions. Field Methods, 19(4), 339–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X07303502

- Weller, S. C., Vickers, B., Bernard, H. R., Blackburn, A. M., Borgatti, S., Gravlee, C. C., Johnson, J. C., & Soundy, A. (2018). Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PLoS One, 13(6), e0198606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198606

- Wilk, R. (2006). Bottled water: The pure commodity in the age of branding. Journal of Consumer Culture, 6(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540506068681

- Wutich, A., Ruth, A., Brewis, A., & Boone, C. (2014). Stigmatized neighborhoods, social bonding, and health. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 28(4), 556–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12124

- York, A. M., Barnett, A., Wutich, A., & Crona, B. I. (2011). Household bottled water consumption in Phoenix: A lifestyle choice. Water International, 36(6), 708–718. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2011.610727