Water, a driver of sustainable development

Water is a critical driver for sustainable development. Protecting from the risks of too little, too much and too polluted water is key for any economic activities and social well-being. The mismanagement of water resources and services can affect people, places and societies. As such, the lack of clean water may limit economic growth worldwide by one-third (Damania et al., Citation2019), and polluted marine environments directly affect billions of people worldwide who rely on the ocean for jobs and food (Patil et al., Citation2016). Moreover, a drought can reduce a city’s economic growth by up to 12% (Zaveri et al., Citation2021). Lack of access to safe drinking water and sanitation may affect income and schooling. For example, in 25 Sub-Saharan African countries, in one day women spend 16 million hours collecting water, at the expense of education or paid work. In fact, many countries are still far from reaching the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 on water and sanitation: according to the latest available data, 74% of the global population uses a safely managed drinking water service, and 54% uses a safely managed sanitation service (UNICEF/WHO, Citation2021).

Megatrends such as climate change, urbanization and rapid population growth are likely to increase the frequency and magnitude of water risks. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) projections show that by 2050 water demand will increase by 55% globally, and about 4 billion people will be living in water-stressed areas (OECD, Citation2012). Over-abstraction and contamination of aquifers worldwide will pose significant challenges to food security, the health of ecosystems and safe drinking water supply. Besides, water infrastructure in the OECD area is ageing, the technology is becoming outdated and governance systems are often ill-equipped to handle rising demand, environmental challenges, continued urbanization, climate variability and water disasters. In addition, the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated the critical importance of sanitation, hygiene, and adequate access to clean water for preventing and containing diseases.

For over 15 years, the OECD has argued that in many instances water crises are often rooted in governance crises, whereby technical, financial and institutional solutions exist and are well known, but their uptake and effective implementation is hindered by several gaps (OECD, Citation2011, Citation2021). Practitioners and government representatives tend to agree that effective, efficient and inclusive water governance is key to coping with pressing and emerging water challenges, because such challenges raise the questions not only of ‘what to do’ but also of ‘who does what’, ‘why’, ‘at which scale’ and ‘how’. In essence, policy responses will only be viable if they are coherent, if stakeholders are properly engaged, if well-designed regulatory frameworks are in place, if there is adequate and accessible information, and if there is sufficient capacity, integrity and transparency.

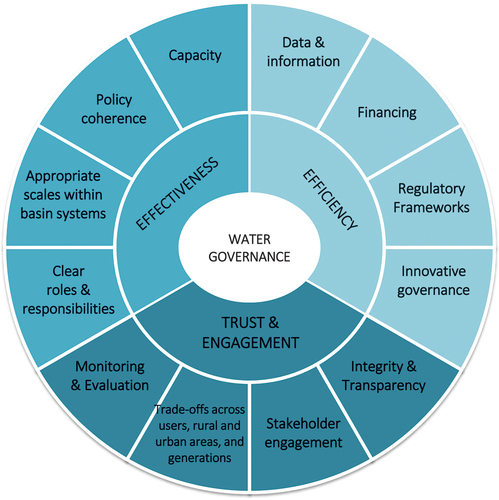

Since their approval by all OECD member countries in 2015, the OECD Principles on Water Governance have guided decision-makers and practitioners on water-related policy development, implementation, research and assessment. The Principles lay out 12 framework conditions for governments at all levels to achieve effective, efficient and inclusive governance systems in a shared responsibility with citizens and stakeholders from the public, private and non-profit sectors. They also provide a framework to understand whether water governance systems are performing optimally at local, basin or national levels, and to guide better policies and reforms for better lives. The Principles were co-produced within the OECD Water Governance Initiative, a multi-stakeholder forum of 120 plus representatives from public, private and non-profit sectors ().

Measuring water governance impacts matters

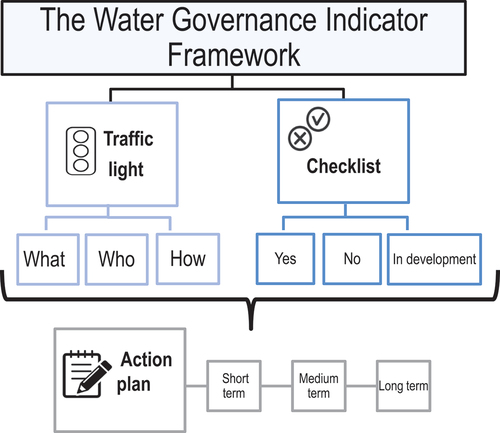

With the objective to help assess the performance of water governance systems, in 2018 the OECD Water Governance Initiative also developed a Water Governance Indicator Framework (OECD, Citation2018a). This self-assessment tool aims to facilitate policy dialogues and consensus among multiple stakeholders on the state of play of water governance policy frameworks (‘what’), institutions (‘who’) and instruments (‘how’), and their improvements over time. The ultimate goal of the framework is to stimulate a transparent, neutral, open, inclusive and forward-looking dialogue across stakeholders on what works, what does not, what should be improved and who can do what. It is composed of a traffic light system of 36 water governance indicators (input and process), a checklist containing 100 plus questions on water governance, and an action plan for improvement in the short, medium and long runs ().

Why is it so important to understand the impact of water governance? Measuring the impact of water governance arrangements can help determine if governance played a role in achieving the desired water management and socio-economic outcomes. However, as documented in the OECD Inventory: Water Governance Impact Indicators and Measurement Frameworks (OECD, Citation2018b), several methodological issues explain why this area of research has remained largely uncharted so far. In particular, water governance impacts depend on a variety of place-based, institutional, environmental and technical factors. As such, positive or negative impacts cannot be attributed to just one cause, institution, mechanism or policy framework. Moreover, most practical examples and studies focus on output and outcomes rather than on impacts, which often require a longer term horizon to materialize. In addition, there is not a universal and harmonized set of indicators or methodology to measure impacts.

Good water governance, as a means to an end, can help improve water services and water quality, protect from water-related risks and reduce their consequences, with ultimate impacts on health, ecosystem, social well-being and economic growth. For example, delivering effective water services at the appropriate scale is key to ensure greater coverage (e.g., to urban and rural areas alike) and leverage economies of scale; coordinating water and energy policies can help increase water-use efficiency; dedicated economic regulators can enhance sustainable financing strategies; greater transparency and citizen awareness of the value of water can drive better quality and sustainability of water services; and setting tariffs that cover the costs of service provision is critical to sustainable investment in universal access and the rational use of water resources. On the contrary, investment backlogs may lead to higher interruption and leakage rates in supply systems, jeopardizing service continuity. For example, in England and Wales (UK), the rate of expenditure for water mains and sewer renewal rates in 2017 was £962 million (€1100 million) per year, an amount estimated to lead to more frequent failures of pipe networks, affecting water customers and the environment (OECD, Citation2020).

Water governance mechanisms can also affect water quality outcomes. For instance, river basin organizations, where they exist, can contribute to better water quality through planning and monitoring. In its 2019 Fitness Check of the Water Framework Directive, the European Union collected data on the status of water bodies for both surface and groundwater. It evaluated the implementation of river basin management plans across member states to assess the extent to which they contributed to restoring the ‘good’ status of ecological bodies. Results show that the stronger the governance of the basin, the more developed the river basin management plan (RBMP), and the better the results in terms of achieving Water Framework Directive objectives. Member states also implemented monitoring networks to better assess the ecological and chemical status of surface waters within RBMPs, which resulted in improvements regarding measures to tackle pollutants and to reduce the negative environmental impacts of hydromorphological pressures (European Commission, Citation2019).

Good governance can drive better preparedness, management and recovery from water-related disasters such as floods. Greater ex ante investment in flood mitigation and prevention can effectively reduce long-term financial needs and improve the economic sustainability of water services. Moreover, removing bottlenecks through policy coherence and greater coordination is essential to prevent and mitigate floods. For instance, the Environment and Planning Act in the Netherlands combines 15 laws and hundreds of regulations for land use, residential areas, infrastructure, the environment, nature and water. This Act replaced the Water Act, the Crisis and Recovery Act, and the Spatial Planning Act to make the environmental legislation more coherent, more open to private initiatives and less burdensome for business and citizens to obtain permits for spatial projects, use data and carry out studies and projects (OECD, Citation2019).

Are we there yet in measuring impacts?

In 2021, the OECD and the International Water Resources Association (IWRA) launched a call for applications to contribute to a Water International journal special issue, ‘The OECD Principles on Water Governance as a Means to an End: How to Measure Impacts of Water Governance?’. The objective of this special issue was to understand the extent to which good governance (as a means) contributes to good outcomes for people, planet and places (as an end), and how to measure such impacts. As such, it leverages the OECD Principles on Water Governance as a common thread across the papers to describe and analyse the state of play and main challenges related to measuring water governance impacts in different geographical and institutional contexts. In particular:

Barraqué et al. examine the evolution of French water governance since the 1960s against all 12 Principles on Water Governance. As a result of this analysis, they offer a preliminary reflection on the impact of governance changes over time, and about the indicators needed to measure these impacts.

Loghmani Khouzani et al. assess the impacts of policy (in)coherence on groundwater management in the Mahyar valley, Iran. They use Principle 3 on Policy Coherence to scrutinize the consequences of inconsistencies across water, land-use and agriculture policies on well use for agricultural irrigation and decreasing groundwater levels. They also highlight the unsustainability of such policies as reflected in groundwater depletion in a context of population growth, climate change and economic development.

Ménard examines the role of ‘intermediate’ and ‘meso-institutions’ in water, sanitation and wastewater services in Egypt. Referring to Principle 1 on Clear Roles and Responsibilities as a benchmark, he shows how flaws in the coordination of polycentric ‘meso-institutions’ and blurred definitions of their responsibilities lead to inefficiencies, hamper innovation and challenge the implementation of appropriate governance. The analysis sheds light on how inadequate institutional design in terms of the allocation of responsibilities and multilevel coordination can derail well-intentioned policies.

Building on the results of a nationwide survey on the perception and involvement of river basin committee members in the decision-making process in Brazil, Matos discusses the governance failures caused by river basin committee members’ gaps in terms of awareness, technical knowledge, accountability and transparency. These flaws adversely affect Principle 10 on Stakeholder Engagement processes and weaken the exchange of ideas and the fair balance across members’ participation, whilst reflecting knowledge asymmetry, challenges to access information and complexity of issues at stake.

Neto and Camkin discuss how a policy that is coherent (Principle 3), transparent (Principle 9) and inclusive (Principle 10) builds trust and enables improvements in water governance over time. They highlight the importance of collaborative planning for long-term sustainable water use through facilitating community learning and capacity-building, as well as the engagement of water stakeholders in the co-design and co-implementation of any water governance indicator framework.

Drawing on a 2021 survey of land and water managers within the Colorado River Basin in the United States, Quay and Sternlieb examine the salience, credibility and legitimacy of two approaches to evaluate policies that integrate water and land management. As such, Principle 1 on Clear Roles and Responsibilities, Principle 3 on Policy Coherence, and Principle 12 on Monitoring & Evaluation serve as a thread to assess the impact of integrated land and water policy practices on water sustainability, using indicators and practitioners’ perceptions of policy effectiveness. Results show that perceptions of policy effectiveness vary according to place-based contexts and organizations.

Velis et al. performed a comparative analysis of eight case studies across North America, South America, Europe and Africa to assess the effectiveness of transboundary aquifer governance. Findings suggest that the most significant contributors to efficacy in transboundary aquifer governance are: (1) institutional structure and mandate; (2) objectives and baselines; and (3) monitoring and adaptive capacity. While these are in line with the OECD Principles on Water Governance, the extent of their implementation is highly contextual.

Luu et al. assess the impact of diverging perceptions of climate adaptation policies at national and local levels on the effectiveness of water governance in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. To do so, they map the objectives of climate adaptation policies as set out at central level and the objectives of climate adaptation policies as perceived by local officials. They find that diverging perceptions and objectives undermined the effectiveness of water governance in the delta.

Based on the corporate governance indicator set up in 2015 by the national regulatory authority to monitor the Kenyan water sector, and referring to Principle 5 on Data & Information and Principle 12 on Monitoring & Evaluation, Zentai shows that a utility that performs well on governance is very likely to perform well on the nine other key performance indicators. In addition, the improvement in the technical performance of utilities appears partly attributable to improved performance in good governance.

The essays in this special issue provide a good overview of the breadth and complexity of issues that arise when assessing water governance impacts. But they are only a first step. Identifying the universal impacts and cohesive units of measurement of governance impacts is a daunting task. To assess how and to what extent governance is delivering the intended outcomes for people, planet and places, there is neither a unique way to measure the complexity that the concept of water governance entails nor a finite number of water governance indicators that can capture the diversity of political, historical, legal, administrative, geographical and economic circumstances. Water governance cannot be isolated from the place-based context and broader governance conditions of a given city, catchment or country. Good water governance, and its related impacts, will largely depend on the broader institutional quality of a given place, and related assessments may also imply subjectivity.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the authors, the Editorial Committee was composed of the following experts: Melissa Kerim Dikeni, Policy Analyst, OECD Water Governance Programme; Donal O’Leary, Senior Advisor, Transparency International; Barbara Schreiner, Executive Director, Water Integrity Network; Daniel Valensuela, former Deputy Director, Office international for Water; and Gari Villa-Landa Sokolova, Head of International Affair, Spanish Water and Wastewater Association. Their commitment is duly acknowledged. Special thanks are hereby conveyed to Peter Glas, Chair of the OECD Water Governance Initiative, for his insights and support throughout the development of this special issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Damania, R., Desbureaux, S., Rodella, A.-S., Russ, J., & Zaveri, E. (2019). Quality unknown: The invisible water crisis. World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32245

- European Commission. (2019). Fitness check of the water framework directive and the floods directive. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/fitness_check_of_the_eu_water_legislation/documents/Water%20Fitness%20Check%20-%20SWD(2019)439%20-%20web.pdf

- OECD. (2011). Water governance in OECD countries: A multi-level approach. OECD Studies on Water. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264119284-en

- OECD. (2012). OECD environmental outlook 2050. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/1999155x

- OECD. (2015), OECD Principles on Water Governance. www.oecd.org/governance/oecd-principles-on-water-governance.htm

- OECD. (2018a). OECD Water Governance Indicator Framework. https://www.oecd.org/regional/OECD-Water-Governance-Indicator-Framework.pdf

- OECD. (2018b). Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator framework and evolving practices. OECD Studies on Water. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292659-en

- OECD. (2019). Applying the OECD Principles on Water Governance to floods: A checklist for action. OECD Studies on Water. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d5098392-en

- OECD. (2020). Financing water supply, sanitation and flood protection: Challenges in EU member states and policy options. OECD Studies on Water. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/6893cdac-en

- OECD. (2021). Fifteen years of water wisdom, the OECD water legacy 2006–2021. https://www.oecd.org/water/regional/Water_Policies_for_Better_Lives_FINAL_WEB.pdf

- Patil, P. G., Virdin, J., Diez, S. M., Roberts, J., & Singh, A. (2016). Toward a blue economy: A promise for sustainable growth in the Caribbean. World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25061

- UNICEF/WHO. (2021). Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000–2020: Five years into the SDGs. https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/jmp-2021-wash-households_3.pdf

- Zaveri, E., Russ, J., Khan, A., Damania, R., Borgomeo, E., & Jägerskog, A. (2021). Ebb and flow: Volume 1. Water, migration, and development. World Bank. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1745-8