ABSTRACT

A complex political economy revolves around shared land and water use between Kenyan Turkana and Ugandan Karamojong pastoralists. In response to growing pressure on resources, donors and the Ugandan government are investing in new surface water sources. However, power and political economy issues embedded within societal relationships are rarely factored into water infrastructure development. Drawing on Tony Allan’s teaching, we examine studies of two dams recently constructed in Karamoja and argue that a wider view encompassing power and politics within the Karamoja–Turkana Complex would help ensure more sustainable and effective future water supply development. Allan’s idea that catchments are part of much wider social, political economic and integrated livelihood systems, or problemsheds, is a key concept. Here we argue that adopting this concept in a complex of pastoral systems can improve future water resources planning and intervention in Karamoja, Uganda and similar contexts.

Introduction: resilience building and competing narratives

After peace, our next priority is water. Am glad we have done some dams, but they are not enough. I have come to check on what we can do to solve this problem completely. […] It is not true that there is no water in Karamoja, it comes and goes and you follow it to Teso. This must stop. The water must stay here. We are going to build about 20 dams. (President Museveni to regional leaders in Moroto district, Karamoja, June 2019)Footnote1

So stated the President of Uganda ahead of elections in 2020. In drylands across East Africa, augmenting water storage is regarded as an important buffer against drought and water insecurity, helping to bridge dry periods for both humans and livestock and enabling dry-season-irrigated agriculture – what is often seen as part of wider efforts at sedentarization of pastoralists. It is also, by extension, politically attractive, especially for governments facing complex state–society relations in often remote pastoral areas. This leads to a supply-led water security agenda that can generate extensive infrastructure construction but without appropriate longer term management arrangements, with significant consequences for the future climate resilience in pastoral areas – and future conflict over resource access.

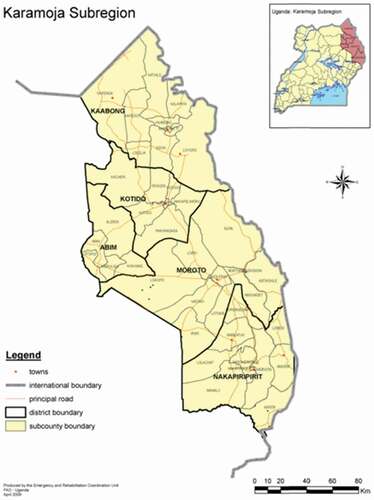

Augmenting water supplies for livestock has been pursued across the Karamoja subregion () under a succession of donor-funded programmes, starting with the Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF) (2003–20),Footnote2 and, more recently, the Karamoja Livelihoods Programme (KALIP) (2010–15) framed under Farming and Peace, Food and Security. The wider focus of these programmes on resilience-strengthening in the face of climate shocks represents a desire to shift from emergency food relief to investments that support sustainable livelihoods for the most vulnerable communities and help in establishing alternative livelihood resources, including small-scale irrigation. Access to water for livestock is regarded as a key element in this policy approach.

In tandem with these approaches, wider issues of water management within catchments have been part of central government water policy objectives. Under the Enhancing Resilience in Karamoja Programme (ERKP)Footnote3 in 2015, this broader water catchment perspective became an additional focus of donor interventions, encompassing water supply as a part of a whole systems approach. This was a significant step towards integrated planning, including food, land and water systems integration within environments under growing human- and climate-induced stress (e.g., the growing demand for biomass energy outside the region causing rapid deforestation).

At the same time, the catchment boundaries remained the planning unit, reducing management to hydrological limits and leading to the reductionism so apparent in much integrated water resources management. This is where Tony Allan’s idea that catchments are part of much wider social, political economic and integrated livelihood systems, or problemsheds (Allan, Citation1999) is a key concept, demonstrably so in the Karamoja subregion. Here, we argue that adopting this concept in a complex of pastoral systems can improve future water resources planning and intervention in Karamoja and similar contexts.

Managing water: power, contest and control

Issues of livestock survival lie at the heart of the Karamoja–Turkana Complex (KTC) – the problemshed at the centre of water management challenges in the region. Movement of livestock between sources of water and grazing is critical to pastoralist livelihoods, especially in light of growing human and animal numbers. Specific seasonal migration corridors provide access to key grazing and water resources as the dry season progresses. People and livestock follow the flow of water along the two major river systems and down into the wetlands of Teso, neighbouring Karamoja to the south-west. Capturing and using some of this flow in a series of dams is, as President Museveni noted, a key objective for government. And the more these sources are made available, the more important the region becomes for the neighbouring Kenyan Turkana, who live in a far drier environment.

In recent years, livestock have been affected by diseaseFootnote4 and poor veterinary support, as well as historic cattle-rustling. In 2021, cattle-rustling and insecurity revisited Karamoja after a period of relative calm. But at a more structural level, after years of livelihood insecurity within pastoral systems, many young Karamojong began seeking alternative livelihoods that would provide immediate cash income, ranging from wage labour to charcoal production and artisanal goldmining. The latter, in particular, contributes to a growing cash economy in this gold-rich region and has emerged alongside the rapid growth in the availability of mobile phones, enabling wealth storage in the digital realm through mobile banking, in contrast to wealth represented by livestock (the more traditional form of ‘mobile’ banking).Footnote5

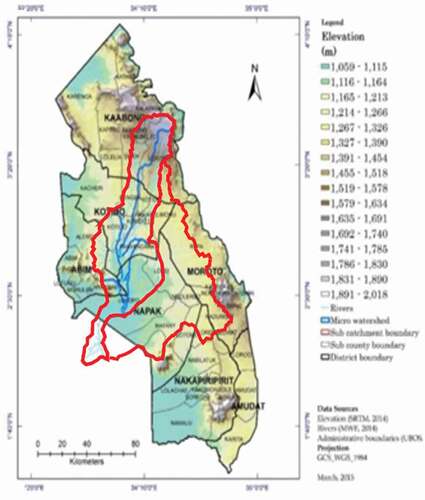

In the face of changing rainfall patterns in the region, building resilience to water scarcity and flood control has been central to the classic hydraulic mission of water infrastructure development. Alongside larger dams holding inter-annual storage, this includes many, smaller valley tanks to capture water sufficient to last three to six months. In this paper, we examine the political economy of the problemshed surrounding two of the three largest dams constructed since 2010, namely Arachet and Longoromit, respectively located in Napak and Kaabong districts. Together, they illustrate how the political-economy of the KTC problemshed is critical to understanding how complex demand for water and, therefore, future management challenges surrounding new water storage infrastructure require a broader view encompassing challenges and pressures that extend beyond the basin boundary.

Introducing new water structures without effective management concentrates people and livestock around water points, potentially generating competition and conflict, and degrading soils and tree cover. In Karamoja, as in other drylands in East Africa, these interventions are often instituted through top-down programmes with little community involvement. The structures are then handed over to the same communities to bear responsibility for managing infrastructural integrity in the long-term and effective regulation and control of the multiple user communities which, in this case, includes Turkana pastoralists from neighbouring Kenya (Mehta et al., Citation2014; Mollinga, Citation2008; Nicol & Mtisi, Citation2003).

This wider scale of analysis, embedded within which are various notions of power, preoccupied Tony Allan’s London Water Issues Group which drew distinctions between soft and hard power, and different power subcategories (Zeitoun et al., Citation2011, Citation2022, in this issue). Building on this analysis, we identify within the KTC three major forms that power has taken: first, direct coercive power, where physical instruments of state and non-state power exercise control over and access to resources, including water under the hydraulic mission; second, ideational power where controlling development narratives shape specific forms of resource deployment, positioning of interventions and management arrangements – including how notions of resilience-building are constructed under donor and government interventions and water infrastructural is made a centrepiece of this approach; and third, economic power, private or public, which shapes how livelihoods decisions are taken – for example, the growing markets for artisanal gold and charcoal that extend well beyond Karamoja to the wider national level, yet play key roles in shaping livelihoods and ecosystems within Karamoja. To these we add a fourth dimension – cultural power – through which, on the one hand, Karamojong society is sometimes characterized by non-Karamojong (and even elites from within the Karamajong) as backward, whilst, on the other, Karamojong exert their strength as a culture through identification with a wider Karamoja ClusterFootnote6 across the region, drawing on affinities in culture and language between peoples from Kenya, South Sudan and Ethiopia.Footnote7 The clash of cultural power with development narratives and shifting to more sedentary livelihoods is a strong current in many donor interventions.

Part of the complexity and schism within the KTC problemshed lies in British colonial demarcation of the border between Kenya and Uganda, which used the edge of the Nile basin and the north-east escarpment of Karamoja as an approximate boundary – hence its distinctly non-straight line. This action bisected peoples who were already sharing a landscape and associated water systems, albeit not always peacefully. Today an estimated 150,000 Turkana herders (about 10% of the total Turkana population in Kenya) move each year across this artificial political divide from drier herding areas to reach richer grazing – in both quantity and quality – and especially at the current time of drought in northern Turkana. This movement is central to the wider problemshed concept (Mollinga et al., Citation2007) as it involves a complex of factors involving political, economic, small-arms-related violence, and government–government at both local and national levels. In 2017, according to an official in KaabongFootnote8 (one of the wettest parts of the region), the district hosted about 50,000 cattle and 30,000 people from both Kenya and South Sudan.

Water governance in such a context is unbounded by basin limits and means that management decisions (on siting, access and regulation) impact wider political complexities between these polities and social groups. Political pressures and disputes arising extend across a substantial range of user communities; pressures that may exist transiently (as in the case of seasonal migrations to water points and grazing and, also, due to the changes in availability across wetter and drier seasons under an uncertain climate), and in very different spatial contexts. Understanding this broad, social, political and cultural context of how resources are used and developed becomes key to determining how, where and why investments in water supply structures and management systems can and should be made.

Field studies

Here we build on earlier work in the Karamoja region conducted during the period 2015–19, including specific analysis of the catchment-based planning process in the Karamoja region on behalf of the Department for International Development (DFID) and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) undertaken from November 2016 to June 2017 (Debevec et al., Citation2017; Nicol et al., Citation2021). For the two dam studies, we held key informant interviews at the national level (Ministry of Water, Directorate of Water for Production, Directorate of Water Resource Management – DWRM), through water-zone level (Kyoga Water Management Zone), catchment level (with representatives sitting on newly established catchment management committees), down to district level (with the elected and appointed officials in the districts where the dams are located) and subcounty levels. Interviews were held with officials at the dam locations as well as in district offices. To cover issues of gender dynamics and water resources development, we held gender-disaggregated focus groups within the communities in the vicinity of the dams – including age–sex-disaggregated discussions – and with key community members involved in small-scale irrigation schemes adjoining both dams. We also interviewed representatives of various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and donors working in the subregion.Footnote9

We carried out four field trips of six to 10 days’ duration (October 2017, March–April, August and November 2018). In addition to the field study, we reviewed the relevant literature with a specific focus on social science and development studies. We extended the political economy framework developed by Nash et al. (Citation2006) to include structural features under ‘historical factors and processes of change’ (A in ). These factors shape the current institutions and structures of power (B) which, in turn, affect and are affected by actors and agents at different levels (C), including the way they exercise power, construct values and project ideologies. While we tried to include a range of stakeholders in the study sample, time and resources were limited; random sampling or household-level survey work was not possible as kraals (pastoral settlements) sprawl over large areas, so we relied on focus group discussions and key informant interviews. The selection of focus group participants may have been biased by individuals and communities being suggested by the district and subcounty-level officials and coordinated by our local research assistant, so we triangulated and corroborated results from and between focus groups and with our key informant interviews.

A new structuring of power and authority

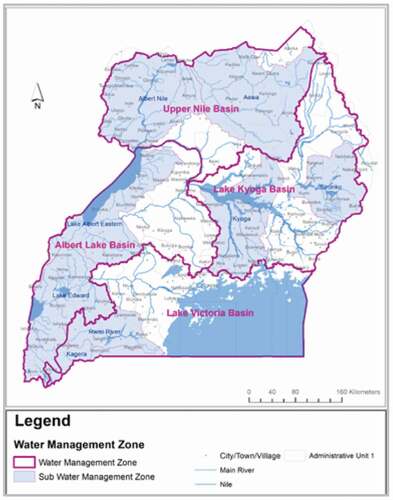

The Ministry of Water and Environment (MWRE) (Citation2014) has been rolling out integrated water resources management (IWRM)-style catchment-based planning, including the issuance of permits, for over a decade (Nicol & Odinga, Citation2016, p. 630) under which Uganda’s eight river basins have been grouped into four water management zones (WMZs). The Kyoga basin zone (KWMZ) includes the study area and both the Lokok and Lokere catchments ().

This new institutional arrangement envisages a role for districts located within catchments (Nicol & Odinga, Citation2016, p. 636). By late 2016, ten district water resources management organizations (DWRMO) had been established.

In Karamoja, the ERKP programme identified strengthening of integrated catchment-based planning and management as key to the development of water resources, including support to the development of catchment management plans for the Lokok and Lokere river basins, the two major catchments in the KWMZ ().

Small water, big narratives

The three dams, Arachet, Longorimit and Kobebe, which have been constructed in the last 10 years, all lie within these two basins and are built to be multipurpose, covering livestock watering, domestic supply, and a source of fish and irrigation water. In global terms they are small, but in the context of Karamoja are huge in their scope and influence on the surrounding social and economic systems – and therefore on the wider KTC problemshed.

Arachet dam () is located in Napak district within the Lokere catchment. It is sited near a much smaller dam known as Natapar ka Emomwai (literally, dam of the sorghum) which silted up and disappeared decades ago. The new structure was built in 2009–10 by Pearl Engineering/BEK Consulting for the Ministry of Water and Environment at a cost of Ush 6 billion (US$1.6 million at current rates). It is designed to serve both adjacent communities with water for irrigation (see ) and to provide water for migrant herds.

Napak district also has 18 much smaller valley tanks, but these empty in the dry season. Arachet is one of very few perennial water sources in Karamoja and services the Bokora, Jie and Matheniko Karamojong and, also, crucially, visiting Turkana pastoralists who may come directly or move to Arachet from Kobebe dam to the north – the third dam mentioned above – especially during March and July. Prior to construction of Arachet dam, herders would move their livestock in search of water to neighbouring districts – ‘chasing the water’ as they describe it – sometimes as far as Teso, Katakwe and Amuria where the wetlands of the Lokok and Lokere catchments provided dry-season grazing.

Arachet dam was constructed with a storage capacity of some 5 million m3. A water point next to the dam, provided at the time of construction, serves as the domestic supply for Nakichumet parish which previously had none. This attracted people from as far as Matany subcounty and Lotome county, bordering Nakapiripirit.

Management is carried out by a water user committee (WUC) of nine, with a caretaker paid for by the district before this responsibility shifted to the subcounty. In discussions with committee members, the largest reported challenge is taking care of the heavily used cattle troughs (). The committee asks people to contribute when watering their cattle and sought to charge Ush 5000 a month for large livestock users, mostly Karamojong herders,Footnote10 and a smaller fee for domestic users of the existing standpipes for household use. During the 2016 national elections, according to local informants, this was contested by the LC5 (district chairperson) who urged people not to pay user fees for livestock to try to gain local votes. Another issue arising from the dam’s construction is the landowner claiming compensation for land lost. According to local informants, much of land where the dam is sited belonged to a former British colonial agent family.

As a new water structure, the dam comes under Uganda’s national water policy framework. The competing claims on the water from the reservoir reveal a lack of clarity regarding rules for issuance of permits for water abstraction. In a small but significant way, this case demonstrates how water remains highly contested even at this very local level, and how strong narratives on water and development can come to dominate decision-making, sometimes disregarding the essentially politically contested nature of water resources management in drylands such as these.

In 2017, as part of the Soroti–Moroto road construction project, an important national project that opens up remote Karamoja to heavy road traffic (essential, amongst other things, for future mining in the region), the international contractor involved requested water for construction. As per regulations, the request was submitted to the permit-issuing office at the DWRMO and was received by officers at the KWMZ in Mbale for appraisal. The KWMZ approved a permit for up to seven trucks carrying 25,000 litres per day, but a subsequent field visit by the permit officer revealed that the contractors were drawing more than the requested amount, that they had done so before receiving the permit, and had started abstracting water at night. Moreover, it appeared that they had done a deal at a local level directly with the district water office and other district officials and had bypassed the DWRMO and KWMZ.

According to community members, abstraction was in the region of 20 trucks a day, each capable of removing some 20 m3. As abstraction proceeded, the local population noticed declining water levels – including the exposure of the new fish-farming cages. After complaining to local councillors, they took the complaint directly to district officials, and then Nakichumet subcounty community members blocked the road to prevent further abstraction of water. The KWMZ informed district officials that the permit had been officially rejected as the amount of water requested was not available. The district intervened to stop the contractors and instructed them to find alternative solutions. During October 2017, a series of water ponds and tanks dug by the contractors appeared along the road as an alternative to water abstraction.

During the next field trip, in March 2018, the contractor had begun pumping water again with the knowledge of district officials, under an memorandum of understanding (MoU) agreed with the district in December. The pumping took place through valves leading from the dam and no longer directly from the reservoir. No protests took place this time. One of the explanations given by the dam caretaker was that there was enough water; another was that since the water was coming from a valve not linked to the cattle trough, this was ‘not the same water’ and therefore did not appear to be in competition. In conversations with local officials, it became apparent that the money was at this time collected at the district and not the DWRMO level. A second MoU with the district, signed in July 2018, stipulated that the contractor could draw water when there was no rain, and the contractor was to pay the district Ush 3 million per month. The dam caretaker was required to note each time the contractor loaded the water bowser. His notes for March 2018 showed a total of 223 trucks were loaded, equivalent to over 4000 m3 if each truck was the standard 20 m3. Although the local population was not consulted about these arrangements and received no compensation, the dam caretaker confirmed having received money personally from the contractor informally. He was also responsible for turning on the tap that connected the dam to the cattle troughs and for preventing misuse of the reservoir, including bathing by local people.

Jurisdiction over the dam had therefore become a point of conflict between the subcounty and the district, including who should benefit financially from payments for abstraction. In many ways, these management challenges represent a microcosm of wider water governance challenges across drylands in East Africa where opacity in ownership rights combines with complex land–water interactions, including emerging relationships between government, private sector contractors and local communities. Some of the opaqueness surrounding the issuance of permits became apparent in discussion with the DWRMO office in Entebbe. We were told that, given the special status of Karamoja following disarmament, it was possible that ‘normal permit rules did not apply’. Officials stated that in the case of Arachet dam, which was built to support the subregion and district development,Footnote11 permit fees did not need to be paid (implying some kind of special status). However, we uncovered no official documentation of such status, which implied flexibility in the application of water permitting rules leaving open the possibility of misuse and rule-breaking. Ostensibly, all permit revenues go to the Treasury, and are then reallocated, including to the DWRMO. The permit issuing office at the KWMZ receives no direct funds and this, as their staff explained, reduced their motivation to follow up breaches in the rules governing permits. Given that there is no official line for local revenue use, there is district-level motivation to make a direct agreement with the contractors.

According to the Water for Production Office,Footnote12 revival of the former irrigation scheme in Nakichumet next to Arachet dam came under a wider initiative by government to establish 40 small-scale irrigation schemes in northern Uganda, which was soon abandoned. A key challenge was the sharing of benefits – but not costs – between scheme users, as well as securing the site and its valuable produce from theft. It was also reported that political interests, appreciating the value of the land, then claimed it back after selling it to the scheme. The number of people associated with the scheme (around 30) was also a challenge, leading to a lack of cohesion and common ‘buy-in’ across the group coupled with a general lack of irrigation experience. As a result, the scheme came to be seen as a ‘rent extractor’, rather than investment asset, so money did not flow back into maintaining the irrigation, only away from it to the users.

Longoromit dam in Kaabong district () was constructed in 2012 at a similar cost and also financed by the World Bank. It was intended to provide a permanent water source in the dry season for the district population of some 400,000 people as well as pastoralists from other areas, including Turkana in neighbouring Kenya.Footnote13 An adjoining water pump fed from shallow groundwater provides for domestic use. As part of efforts at livelihood diversification, the production department introduced fish into the reservoir, although local communities actively shun fish consumption.Footnote14 To the west, a small-scale irrigation plot was established. A detachment of troops is stationed nearby to oversee security, given the contestation over access to the reservoir, and made use of the fish stock and water pump.

A management committee was established but its governance, constitution and remit remained unclear at the time of the visit; the committee represented only one community surrounding the dam (Lobonge), with members chosen from among LC1s and LC2s, according to local informants. Local stakeholders stated that their remit was mainly to safeguard the micro-catchment around the reservoir and to prevent cultivation around the dam (beyond a small, irrigated plot). The committee also managed access to the cattle troughs including preventing direct access to the reservoir for cattle, and called community meetings when there were clashes at watering points. The neighbouring pastoralists from Jie (Kotido district) or Turkana (Kenya) would seek permission from the host community through the management committee and subcounty officials.

The Turkana ‘threat’, as some informants described it in Kaabong district, included their use of water provided by Longoromit dam. Community members mentioned that their presence had restricted artisanal goldmining, an increasingly important source of cash income, in particular for youth. During 2016, a year of lower-than-average rainfall, the reservoir was used for the whole year by Turkana, with locals resorting to the Kaabong River (the traditional water source for livestock) under an agreement reached between the two groups. The agreement followed a tradition of dialogue on water and pasture usage between Turkana and Karamajong communities, in spite of years of cattle-rustling. Nevertheless, in 2017, there were deaths in Kaabong over disputed grazing areas near Longoromit, according to local leaders. The same local leaders consulted during the research claimed that they had suggested a more distant location and the proximity of Longoromit to Kaabong town was a factor possibly contributing to the incident.

Part of the wider political economy in relation to access to resources in Karamoja concerns dialogue and reaching of agreements over grazing and access to water, including the establishment of two peace corridors at Lomia–Moroto and Lokink–Kweata. Discussions with both Karamojong communities and district officials, as well as with Turkana representatives, revealed the lived reality of one system shared between two communities. A further example of this wider institutionalization of cooperation is the Loyolo Resource Sharing Agreement signed between Dodoth of Kaabong and Turkana, enabling Turkana to access pasture and water in Uganda. The agreement included a bush market and land allocation to the Turkana for cultivation. Under USAID, PEACE III is also supporting the peace process between the Dassanech of Ethiopia to access water and pasture in the Todonyang area of Turkana–Kenya. The Dassenach can now access these resources, which greatly helps their coping with drought and dry seasons. In other words, this is not a simple resource-scarcity/conflict relationship. Arguably, across what we call the KTC, there are many complex relationships that each has an impact on the management of resources in specific geographies and at particular times.

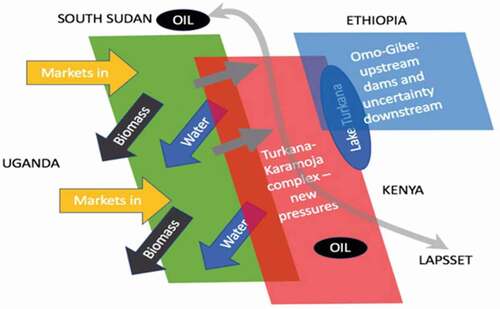

At the extremities of this system, changes in access to pasture and water may heighten competition and exacerbate tensions. Elders in KaabongFootnote15 describe tensions surrounding Turkana overgrazing and felling of trees for firewood and shelter in their district. Jie people from the drier Kotido district also come to Kaabong to cut trees for firewood. Additional external pressures include the impact of the Gibe III dam in Ethiopia, which has changed the flow of the Omo River into Lake Turkana affecting key wetland areas for cattle-grazing; particularly affecting the Nyangatom from South Omo who are related to the Karamojong and part of the Karamoja ‘Cluster’. The Turkana are further affected by oil exploration in southern Turkana and associated land enclosures in important grazing areas. Exploitation by extractive industries is likely to occur as the LAPSETT corridor from Lamu to South Sudan is constructedFootnote16 with this longer term infrastructure development opening up Karamoja’s rich mineral resources to greater exploitation.

Changing pressures on livelihoods in Karamoja are likely to bear down on water management as complex political economies shape and change the interest groups with a stake in future water management and governance. As catchment planning is institutionalized in the region under recent donor interventions, understanding these political economies should be a key part of refining the water management process through understanding the broader political-economic pressures that determine patterns of demand within the KTC problemshed. Local officials expressed knowledge of meetings in Gulu and Kitgum under the WMZ related to catchment planning in the Lokok catchment but, short of requests received to establish WUAs, these key political actors maintained only a tenuous sense of engagement in wider catchment planning processes.

The implications of forms of power within a complex problemshed

The problems associated with these two small dams reflect wider challenges and processes surrounding water-supply investment, power and politics in the East Africa region. They show that, beyond the technical challenge of construction, attention needs to be given to the long-term governance of surface water resources taking account of political pressures. Narratives on resilience are often reduced to making water more available – a supply-driven ‘hydraulic mission’ – but, in fact, supply without effective governance can exacerbate resource competition and reduce resilience.

At the outset, we described forms of power within this problemshed and how these can help unpack relationships between users, managers and legal entities. helps interpret these in relation to the evidence presented.

Dam construction often acquires a political logic of its own. It is a symbol of progress that donors and local leaders can parade – especially at election time – with the promise of future benefits. This is amplified by national media, suggesting that local objections to siting dams nearer to towns and district offices can be overridden in the name of development. This ideational power helps to overcome local resistance and can present this resistance as ‘barriers to change’. As a local key informant observed of the Longoromit siting, ‘sometimes politicians don’t want things located technically, but for political reasons’.Footnote17 This ideational power is further reflected in the coupling of dam construction with irrigation development – a challenge to established livelihood norms in the region based on pastoralism and rainfed agriculture.

In the cases of both the Arachet and Longoromit dams, post-completion management structures appeared inadequate, with confusion over responsibility for overseeing and maintaining structures and operations – including of benefit streams. As soon as water abstraction and permit issues arise – and the monetary value of water becomes apparent – struggles for control over these value streams may surface, even between formal government institutions demonstrating where de facto economic power lies. If such dams are to contribute to real resilience and sustainable livelihoods, their design, siting and management needs to be improved – and the economic power they represent needs to be managed and disbursed under effective governance structures. Otherwise, and especially in times of scarcity, competition for this power may lead to conflict. Whilst their purpose is simple – to provide dry-season stock water – their siting, management and inclusion in broader narratives for water production is complex. It presents new governance challenges, including multiple layers of decision-making. Indeed, informal coercive power in the form of small-arms violence around these structures can arise.

This suggests the need for a broader set of criteria in designing and implementing dams such as these in complex problemsheds, and criteria that include ways of understanding competition between narrow, sectional interests and wider development objectives. As the race to exploit the region’s resources accelerates, and given the government’s stated objective of multiplying these structures across Karamoja, these interests and powers may well find themselves in conflict. More generally, the decline of pastoralism is a fundamental shift in the political economy of Karamoja, hitherto home to 20% of Uganda’s total livestock (Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), Citation2014). And as land use changes, conflicts over land are increasing as communality gives way to private land grabs. Those who have ‘gone to school’, as Karamojong elders term it, understand the value of land (including in relation to farming, minerals and urbanization) and join a new elite seeking greater individual ownership at the expense of established communal management. In response, a process of customary land certification has been initiated by central government, but this will be a long process with no guarantee of success.

The major assumption of water resources development in Karamoja remains that water can be isolated from surrounding complex polities and social structure, and be treated as a single, contained system. Our analysis suggests, instead, that future planning and investment should be examined within the context of the KTC. depicts how some of these processes and pressures apply to water development in the region.

Economic power drives markets for firewood and charcoal from Karamoja leading to the rapid depletion of woodland, in turn affecting land degradation and flood management in the Lokok and Lokere catchments.

The demand for water will continue, and possibly grow if livestock numbers recover, yet the narrative on making water available without understanding the wider problemshed complexities continues to affect siting and management. Catchment planning must factor in future power and political-economy issues specific to water management to strengthen the next generation of planning and investment processes in the region and, in so doing, respond to the reality of wider political-economic landscapes beyond the basin shaping future water resources development within this remote patch of the Nile basin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

2. NUSAF was largely funded by the World Bank; KALIP was funded by the European Union (EU).

3. Funded by the Department for International Development (DFID).

4. Muhanguzi et al. (Citation2017) report that African animal trypanosomiasis and tick-borne diseases in particular have a serious impact on communities in the region. This aggravates poverty and malnutrition and undermines wider development efforts.

5. The extension of mobile telephone services has revolutionized cash income-earning. Herders use small panels to charge their mobile devices directly and, in one community visited near Kaabong town, nearly all men had mobile phones which they used for banking and security. Few, if any, rural women have access to phones and the network remains unreliable.

7. Many researchers use the term ‘Karamojong’ to refer in a political sense to the wider citizens of Karamoja (e.g., Caravani, Citation2018; Scott-Villiers & Karamoja Action Research Team, Citation2013). However, this masks great heterogeneity, including people originating from other parts of Uganda. This is important for claims to land and access to resources, particularly as there is a trend towards more individual land ownership. Karamojong inhabiting southern districts consist of three clans: Matheniko in Moroto district, Bokora in Napak district and Pian in Nakapiritpirit district (Czuba, Citation2011). The name Karamojong is often applied to the Jie and Dodoth further to the north due to similarities in language and culture. Jie live in Kotido, while Dodoth live in Kaabong district. Within these main groups there are nine separate tribal subgroups, all of which speak Ngakaramojong (Adoch & Ssemakula, Citation2011).

8. Personal Communication with the chief administrative officer, Kaabong district, October 2017.

9. Oral consent was given by informants before the recording of interviews. Focus group discussions were held in the Karamojong language with immediate translation into English.

10. Other specific challenges faced include upstream catchment management around the dam, such as loss of trees in 2016 and grass-burning in the dry season. In that year, grass-burning damaged the plastic pipes that carried water from the reservoir to the small, irrigated area.

11. For an example of the water construction narrative on Karamoja related to Arachet, see this contemporary blogpost (https://msserwanga.blogspot.com/2012/).

12. Interview with Mr Patrick Okotel, Mbale.

13. Unfortunately, this dam was almost dry in 2022 (https://www.africa-press.net/uganda/all-news/shs12b-longoromit-dam-in-kaabong-district-dries-up).

14. Communities spoken to in Kaabong referred to it as akin to a ‘consuming snake’.

15. 14 October 2017 focus group discussion with elders, Kaabong district.

16. Interviews with NGO officials from Turkana county, Kenya, September 2018.

17. District official, Kaabong town, September 2018.

References

- Adoch, C., & Ssemakula, E. G. (2011). Killing the goose that lays golden egg. An analysis of budget allocations and revenue from the environment and natural resource sector in Karamoja Region (ACODE Policy Research Series No. 47). Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment.

- Allan, J. A. (1999). Water in international systems: A risk society analysis of regional problemsheds and global hydrology (SOAS Water Issues Group Occasional Paper 22). School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. https://www.soas.ac.uk_water_paper_file38365pdf

- Caravani, M. (2018). De-pastoralisation in Uganda’s Northeast: From livelihoods diversification to social differentiation. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(7), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1517118

- Czuba, K. (2011) Governing the Karamojong: Tradition, modernity and power in contemporary Karamoja (Project Evaluation Report). BRAC.

- Debevec, L., Nicol A, A., & Nigussie, L. (2017). Integrated water resources management in the Karamoja sub-region of Uganda – An evidence review and diagnostic study of current investments and best practice (Unpublished Report for Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit).

- Mehta, L., Alba, R., Bolding, A., Denby, K., Derman, B., Hove, T., Manzungu, E., Movik, S., Prabhakaran, P., & van Koppen, B. (2014). The politics of IWRM in Southern Africa. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 30(3), 1–15. Retrieved January 1, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2014.91620

- Ministry of Water and Environment (MWRE). (2014). Uganda catchment management planning guidelines.

- Mollinga, P. P. (2008). Water, politics and development: Framing political sociology of water resources management. Water Alternatives, 1(1), 7‐23. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/volume1/v1issue1/15-a-1-1-2/file

- Mollinga, P. P., Meinzen-Dick, R. S., & Merrey, D. J. (2007). Politics, plurality and problemsheds: A strategic approach for reform of agricultural water resources management. Development Policy Review, 25(6), 699–719. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2007.00393.x

- Muhanguzi, D., Mugenyi, A., Bigirwa, G., Kamusiime, M., Kitibwa, A., Akurut, G. G., Ochwo, S., Amanyire, W., Okech, S. G., Hattendorf, J., & Tweyongyere, R. (2017). African animal trypanosomiasis as a constraint to livestock health and production in Karamoja region: A detailed qualitative and quantitative assessment. BMC Veterinary Research, 13(1), 355. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1285-z

- Nash, R., Hudson, A., & Luttrell, C. (2006). Mapping political context. A toolkit for civil society organisations. ODI.

- Nicol, A., Debevec, L., & Okene, S. (2021). Chasing the water: The political economy of water management and catchment development in the Karamoja–Turkana Complex (KTC), Uganda (IWMI Working Paper 198). International Water Management Institute. https://doi.org/10.5337/2021.214

- Nicol, A., & Mtisi, S. (2003). The politics of water: A Southern African example (Sustainable Livelihoods in Southern Africa Research Paper 20). Institute of Development Studies.

- Nicol, A., & Odinga, W. (2016). IWRM in Uganda – Progress after decades of implementation. Water Alternatives, 9(3), 627–643. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol9/v9issue3/326-a9-3-13/file

- Office of the Prime Minister (OPM). (2014). The second Karamoja integrated development plan (KIDP2) 2015–2020. Office of the Prime Minister, Ministry for Karamoja Affairs.

- Scott-Villiers, P., & Karamoja Action Research Team. (2013). Eki and Etem in Karamoja. A study of decision-making in a post-conflict society. Institute for Development Studies.

- Zeitoun, M., Cascão, A., Daoudy, M., Greco, F., Mirumachi, N., & Warner, J. (2022). Power plus: Tony Allan’s contributions to understanding transboundary water arrangements. Water International, 47(6), 1001–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2125234

- Zeitoun, M., Mirumachi, N., & Warner, J. (2011). Transboundary water interaction II: The influence of ‘soft’ power. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 11(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9134-6