ABSTRACT

Nowhere is the contrast between the top-down process of drawing a boundary and the ground-up reality of living with it so obvious as in delimitations along rivers – live features not just physically but also, potentially, navigable arteries. Illustrations are drawn from the chequered history of two famous colonial river boundaries along the Shatt al-Arab and Jordan rivers; and in the invocation of history in legal settlements of the status of Kasikili/Sedudu Island in the Caprivi Strip (1995–99) and the Abyei region on the Bahr al Arab between Sudan and South Sudan (2008–09).

Introduction

In legal terms, inter-state territorial delimitations running along rivers are classified as international land boundaries, but this prominent subcategory – whose origins always go back deep into history – poses a unique set of complex management challenges. Land boundary delimitations are essentially statist abstractions, legal lines of coordinates that are only given width and presence on the ground by the functions, facilities and (increasingly) the fortifications states choose to place there. Rivers are live physical features whose fluidity contrasts with sovereign connotations of territorial permanence and whose dynamism often results in changes to channel course and form (Prescott & Triggs, Citation2008, p. 215).

If the above amounts to an admonition that rivers are poorly suited for adoption as international boundaries, then there are also more fundamentally broad considerations at play here that relate more broadly to the history of human experience – as Bouchez alluded in a comparative review of river boundary delimitation following France and Germany’s Rhine agreement of April 1960:

Rivers, […] are natural links for the people who live adjacent to them. From history it is evident that both sides of a river valley were often areas of identical cultural and economic development. Thus, in relation to cultural and economic development, river valleys must be considered as a unit. (Bouchez, Citation1963, p. 789)

This position brings into sharp relief the oft-observed remote and marginal character of borderlands surrounding land boundaries that lay beyond a state’s economic and political core regions, frequently observable in a colonial context. For navigable rivers adopted as international boundaries the position was often quite different, especially economically where the banks could be a hive of activity, if not always hugely significant politically beyond their local context. The potential for contradictions and clashes between the top-down nomination of rivers as territorial limits and the ground-up socio-economic organization of riverain borderscapes was and is always there. While this article primarily seeks to further contribute to an existing body of literature that details the evolution of river boundary delimitation from a historical, technical and legalistic standpoint (Bouchez, Citation1963; Prescott & Triggs, Citation2008; Donaldson, Citation2009, Citation2014), it acknowledges that the current critical border studies literature has potentially much to offer in unveiling the ground-up human geographies of international river boundaries, with its phenomenological focus on the ‘lived experiences’ of borderlanders (Bialasiewicz and Minca, Citation2010).

If the illogic of nominating rivers as international boundaries is apparently clear, conversely there has been a clear historical logic to adopting them; as territorial outcomes of conflict; for the strategic benefits this confers; to reflect a fad for ‘natural’ boundaries and lastly; for their superficially easy recognition on maps. When one also considers the pronouncedly historical character of most international river boundaries, these considerations would have been instrumental in their adoption. Bear in mind, too, that the classical delimitation expert, Stephen Jones, did not see their adoption as likely to stop following the Second World War: ‘rivers will probably be adopted as boundaries even though the geographer or engineer inveigh against them’ (Jones, Citation1945, p. 108). And who knows, with state fragmentation and conflict providing ever more fertile grounds for secession in 2022, their nomination may continue to figure.

This article traces in varying detail levels four case studies – Shatt al-Arab (Iran/Iraq); Jordan (Israel/Jordan); Chobe (Botswana/Namibia); and Bahr al-Arab (South Sudan/Sudan) – to show how definitional and operational challenges were broached historically, how the thought process about river boundaries developed and how history was used retrospectively in the dispute resolution process.Footnote1

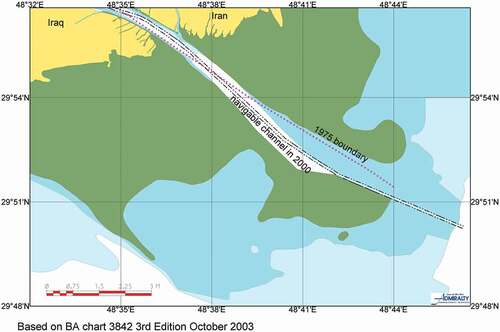

An 11 March 2019 announcement suggested that Iran and Iraq had agreed inter alia to respect the thalweg boundary delimitation introduced by bilateral treaty in June 1975. The arrangements struck that year arguably constitute the most sophisticated and comprehensive arrangements concluded in international law for dealing with a river boundary, with every conceivable safeguard contained for managing future dispute over delimitation status and alignment. Arguably, the specifications went too far, however – over-egging the pudding in trying to cater for the possibility of future physical change. Our focus here is to chart the evolving definition of the thalweg ().

The 26 October 1994 Israel–Jordan Peace Treaty reaffirmed a vaguely worded 1922 colonial territorial limit (Palestine/Transjordan) as the international boundary north and south of the West Bank (). For the most part the peace agreements retained the basis for dealing with physical change in the boundary river decided upon by the British Colonial Office in 1927 but, pragmatically, left all options open for dealing with future instances of sudden changes of river course (avulsion). Our chief concern here is to consider attitudes to physical change in boundary rivers and their effect on the alignment of delimitation – so the decisions taken during 1927 are clearly central.

A 13 December 1999 judgment of the International Court of Justice (Citation1999) held that the river boundary between Botswana and Namibia should run in the channel north of Kasikili/Sedudu island in the Chobe River. Yet, in something of a curve-ball, the court decreed at the same time that there should be equal rights of access north and south of the feature. There had been few indications that the sovereignty of the insular feature was a major issue on Namibian independence in 1990, but the dispute was forwarded for judicial treatment by special agreement in February 1995. Historical concerns were essentially retrospective therefore in the process of dispute resolution – specifically concerning issues of territorial allocation in an 1890 spheres of influence agreement between Britain and Germany. Our focus here is on identifying the major or principal channel in a boundary river.

A 22 July 2009 Permanent Court of Arbitration award established the territorial extent of Abyei province as an effective starting point in defining the international land boundary between Sudan and its new neighbour of Southern Sudan. The location and identity of rivers and the recognition of riverain terrain constituted a key component of this hurried case and award. The chief historical concerns here were again retrospective, centring around the transfer of one tribal group from one province of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium of Sudan to another in 1905 – with the presumption that there must have been some inkling of territorial definition for that transaction to take place. Our concern here is to highlight prevailing historical uncertainty over the identity of rivers, amidst questions about the reliability and admissibility of colonial evidence.

Drawing international boundaries along rivers

The rules of the game for defining river boundaries were broadly developed with Article 30 of the 28 June 1919 Treaty of Versailles with a median line stipulated for non-navigable rivers and division along the principal channel recommended for navigable rivers (Prescott & Triggs, Citation2008, p. 216). Yet this functional rationale had come all too late for the many and large variety of river borderscapes established by this time. Early international river boundary treaties often granted sovereignty over the whole water course to one riparian with the bank specified as the inter-state divide, obviously inequitable and generally the result of one power having the upper hand politically or militarily over its neighbour, a ratification of the territorial outcome of conflict. An example here was a 1773 Prussia–Poland treaty that set the boundary along the Polish bank of the Netze. Twelve such treaty arrangements survived into the post-Second World War period (Sevette, Citation1952).

It was especially during the European overseas colonial expansions that peaked in the last quarter of the 19th century that rivers were adopted as imperial boundaries. With rivers (and mountain ranges) not only representing opportunities for defence but also supposedly easy to identify on the crude cartography of the day, this reflected a coterminous fad for ‘natural’ boundaries, territorial limits that were coincident with prominent surficial features of the Earth. They would be almost reified by some prominent imperial boundary-makers, such as Government of India Surveyor-General Thomas Holdich, who posited – looking back on his own handiwork in the Asian subcontinent – that there could be no better boundary than that consisting of riverain and mountainous sections combined (Holdich, Citation1916, p. 46; Schofield, Citation2015, p. 137) While looking at things top-down, there is much to support Jones’s observation that ‘[t]he extensive use of river and geometrical boundaries testifie[d] to the prevalence of absentee boundary-making’ (Jones, Citation1945, p. 39); there have also been some efforts – for instance, in legal cases – to posit that equivalent notions of rivers acting as natural divides and barriers to movement held sway from a more localized, ground-up perspective. This would become a minor issue in the PCA’s 2008–09 Abyei case (see above). Here the Bahr al-Arab had possibly formed a loose Ottoman administrative division during the late 19th century, but to what degree was it seen as a boundary by groups on either side in a more localized sense? Did it constitute an effective local barrier to movement and, if so, was this more of a seasonal phenomenon?

The vogue for ‘natural’ boundaries would soon pass, certainly any intellectual case for their adoption. Yet, while no one would argue seriously for their continued adoption, they have disappeared neither from the legal process of boundary-making nor academic discussion. Support for natural boundaries holds in certain situations, such as in international law’s application of inter-temporal law in the adjudication of colonial boundary cases. An example can be found with the judicial resolution of the Honduras-El Salvador 1992 land boundary dispute at the International Court of Justice (Citation2017-22). Here, in attempting to second-guess what the colonial power would have understood by the line of uti possidetis juris it was bequeathing back in 1821, the ICJ seemingly tried to get into the imperial boundary-making mindset that would have prevailed at the time. The assumption in this instance that natural features would have been utilized in delimitation led to a presumption in favour of rivers as constituting the land boundary (Prescott & Triggs, Citation2008, p. 226). So, maybe there is life in that old natural boundaries dog yet. Recently, also, critical border scholars from the social sciences have begun to reimagine why boundaries (or any features that might constitute them) might be seen as ‘natural’ by those who encounter or have to negotiate them (van Houtum, Citation2005). The concept of natural boundaries in the round has been revisited imaginatively (Fall, Citation2010), including within an imperial boundary-making context (Tillotson, Citation2020).

History is omnipresent in the consideration of any international boundary, resonating most loudly and dramatically when invoked and mobilized for political gain during the course and conduct of disputes and the issue and pursuit of territorial claims (Murphy, Citation1990; O’Dowd, Citation2010). Regulation of the territorial framework enshrines the record of treaty settlement to bolster the stability and finality of international boundaries, while the dispute resolution process prioritizes the historical (and often colonial) evidentiary record – leading to charges from postcolonial law that it is essentially neo-colonial in nature (Anghie, Citation2006).

However, history tends to matter even more for rivers than for other classes of land boundary. After all, more history has been accumulated since they have tended to be around for longer. The varying ways in which boundaries have been drawn along rivers generally reflects a balance of top-down considerations in their nomination and the specific complexities of the regional environment into which they have been introduced. Consequently, river borderscapes tend to be very distinctive in their territorial arrangements and not easily subject to comparative study. If Jones caution that ‘(e)ach boundary is unique and therefore many generalisations are of doubtful validity’ (Jones, Citation1945, p. vi) holds true in a general sense, it is perhaps even more pertinent for river boundaries. If the logic for sharing the main channel of a navigable river was appreciated (if not always applied) long before the principle’s codification at Versailles, there were other ways in which boundaries were drawn along riverain features observable by the early 20th century. In instances where median lines were employed for non-navigable rivers, their adoption tended to be relatively less problematic, requiring less attention and management going forward since the river would generally not be so active an economic zone. Yet there was not any appreciable consistency in the nomination of navigation channels and median lines as river boundaries before 1919 and there would not be any significantly enhanced uniformity going forward.

In addition to riverbanks, navigable channels and median lines being adopted as boundaries, other arrangements were also in evidence – ones that acknowledged the specific natural structure of the river in question. In those rare cases where there were two equally important channels, the boundary might be fixed so that each state possessed its own, and this was how Portugal and Spain treated the River Guidiana in 1895 (Bouchez, Citation1963, p. 795; Lauterpacht, Citation1960). To introduce stability to the boundary along the St. Croix River by effectively rendering irrelevant variations in water flow, Canada and the United States arrived at a delimitation comprising arbitrary straight-line segments that were actually demarcated in this instance by pillar (Bouchez, Citation1963, p. 795). Complex river boundary delimitations arose when different methods of fixing a river boundary were employed for different stretches of the water course (p. 796). No one would ever devise such a scheme in introducing a delimitation; rather, it would usually eventualize in response to the economic and strategic value of the waterway and the local and international use made of it – developing in piecemeal fashion. Sometimes, too, regional circumstances needed to change before the ideal delimitation could be introduced, colonial and postcolonial. The Shatt al Arab was the most obvious example here (see below) (Schofield, Citation2004). By the early 1960s, legal experts would be championing a co-imperium over waterways as their preferred arrangement for international boundary rivers, with sovereign state limits fixed at the low-water mark on each bank (Lauterpacht, Citation1960). This was how Germany and France delimited the Rhine in their 8 April 1960 treaty.

Beyond how boundaries were drawn along waterways historically, the way in which their surrounding borderlands were altered as a consequence or deliberately configured in accompanying regional infrastructural schemes warrants mention. River borderscapes were sometimes seemingly more obviously created for the benefits of states or, just as often, colonial powers than the local populations themselves. Their architects might aim for showcase diplomatic settlements that provided the requisite definitional clarity to preclude further territorial disputes and enable the projection of economic or strategic regional interests. The St. Croix (US/Canada) settlement of the late 18th century was essentially designed to introduce enhanced territorial definition to decrease the possibility of future interstate conflict – it was not really for the benefit of the locals (Demeritt, Citation1997). Britain knew from the start what boundary would be fairest for the Shatt al Arab at the head of the Persian Gulf, but also realized that it was constrained by the art of the possible if it wanted to project its economic interests in southern Mesopotamia from the mid-19th century forward. So it pragmatically arrived at a mixed fudge of vague delimitation and explanatory notes in its attempts to keep the Ottoman Empire and Persia on board – and not wholly successfully (Schofield, Citation2004). Moving to East Africa a half century later, Britain and Italy came up with a novel scheme by agreement in 1911 to recognize that the river (Juba) separating their colonial territories was highly unstable, frequently cutting new courses including new openings into the Red Sea. Basically, the two sides agreed to regard the whole river valley as a river boundary zone – quite prescient in many ways (Field, TNA, Citation1927, CO 733/142/1).

The last point to underline in this extended introductory section is that certain conventional wisdoms about inter-state riverine limits, like any international boundary, have been around for a long time. It was also in 1911 that the Institute of International Law issued their Madrid Resolution to decree the following. States with a common river boundary were in ‘a position of permanent physical dependence on each other which precludes the idea of the complete autonomy of each State in the section of the natural watercourse under its sovereignty’ (Prescott & Triggs, Citation2008, p. 216). Such a statement was meant to apply to both divided and successive river disputes, would soon find an echo quite soon in the Versailles rules but also, much later, in the 1997 Convention on the Non-Navigational Uses of International Waterways. Old truisms tend to resurface in statements about international boundaries.

Working out how to deal with river boundaries: lessons from history

Shatt al-Arab

It would take a full 128 years of regulating treaty history for boundary delimitation along the estuary to move from eastern (Iranian) bank, the limit Britain had meant to introduce with the 1847 Treaty Of Erzurum, to the thalweg line introduced by the package of agreements and treaties agreed between Iran and Iraq during March–July 1975 (Schofield, Citation2004). Yet the suitability of a mid-channel delimitation had been known from the start, as no less a figure than British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston had demurred in March 1847, two months before the Erzurum treaty had been signed:

[…] I have to state to you with reference to the pretension which has been advanced by the Porte [Ottoman Empire] to an absolute right of sovereignty over the Chat-el-Arab, that when the opposite banks of a River belong as they will do in this case of the lower portion of the Chat el Arab, to different Powers, it would be contrary to International usage to give to one of the two Powers the exclusive sovereignty of that portion of the course of such River, and that therefore this proposal of the Turkish Government seems to be inadmissible. (Palmerston, The National Archives (TNA), Citation1847, FO 78/2716)

The ideals expressed here echoed the legal logic articulated early in the 17th century by Hugo Grotius whereby: ‘the jurisdictions on each side reach to the middle of the river that runs betwixt them’ (Prescott & Triggs, Citation2008, p. 215). Yet Britain, after all only a mediating power with Russia on the quadripartite commission that sought to lay down a boundary from the Gulf northwards to Mount Ararat, ultimately had no choice but to expediently accommodate Ottoman claims. It regarded the 1847 treaty as having laid down a boundary along the Persian bank without the document having specified as much (Schofield, Citation2004). The ensuing four-party project to lay down in stone the line supposedly outlined in the Erzurum deal over the next few years ended in near farce, with ambitions soon relegated to collecting data that would allow for the mapping of the borderlands (Schofield, Citation2008a). A much more pragmatic Palmerston would soon comment that Britain and Russia could only lay down the boundary they were urging if they possessed full arbitrating powers. These would ultimately be afforded in advance of a further quadripartite treaty of November 1913 that sought to adjust, update and refine the Perso-Ottoman territorial deal of 1847. Another stab at demarcation followed during 1914. Though far from a glowing success, Britain and Russia had at least in their own minds stabilized this classic frontier zone, albeit nearly seven decades later than originally planned. No wonder Ernest Hubbard, Britain’s Secretary on the 1914 demarcation commission, described the episode as constituting ‘[a] phenomenon of procrastination unparalleled even in the chronicles of Oriental diplomacy’ (Hubbard, Citation1916, p. 2).

If expediency had dictated that the mid-channel did not get nominated as the Perso-Ottoman boundary along the Shatt during the mid-19th century, it would be the local observations in the early 20th century of a young Arnold Wilson, then a junior British official at Muhammara (now Khorramshahr) and the future architect of imperial Iraq, that redirected attentions to the question of delimiting the river boundary in the early 19th century (Schofield, Citation2004). He noted how the local authorities on both sides of the river recognized the mid-stream as the boundary in the vicinity of Muhammara and that not only commerce and shipping apparently respected it as a matter of course but the inhabitants of either bank. The local observations of imperial agents and their suggestions for the application of European spatial norms to areas of the colonial world is a frontier experience that has come under increasing scrutiny in historical border studies in recent years (Simpson, Citation2021; Tillotson, Citation2020). There were also notable examples where locals would point out that Britain was not even implementing its own delimitation logic properly when demarcating the territorial limits it had introduced – usually when mistaking or misinterpreting the natural features that supposedly governed them (Jones, Citation1945, p. 39; Schofield, Citation2008b, pp. 419–420).

Despite Wilson’s observations that Britain would hold to the line that the Persian bank constituted the proper boundary until such time as wider economic circumstances changed more fundamentally – namely the discovery in 1908 of oil in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. This got their officials thinking about improving Muhammara’s anchorage facilities for the future export of oil, specifically replacing the outdated facilities on the River Karun with modern ones on the Shatt. So Wilson’s observations would be used as the justification to extend the river boundary to the median line – but note not to the thalweg line – of the Shatt in Britain’s recommendation for a delimitation, but elsewhere this would remain as running along the low-water mark of the Persian bank in the 1913–14 settlement (Schofield, Citation2004, Citation2008b).

Following the specification of the Versailles thalweg/median line rules for navigable and non-navigable rivers in 1919, Iran would push fairly consistently for a thalweg boundary along the whole length of its boundary with Iraq along the Shatt from the mid- to late 1920s onwards. It was something of a surprise therefore when Iran and Iraq agreed a further treaty in 1937 that extended the river delimitation to the thalweg, but only for the short stretch alongside the Iranian oil port of Abadan, home to the world’s largest oil refinery in the early 20th century (Schofield, Citation2004). There were some complex linkages to other bilateral, regional and security questions, but no one has ever really got to the bottom of why Reza Shah agreed to an adjustment that resulted in the Shatt boundary being defined variously along the Iranian bank, median line (Khorramshahr) and thalweg (Abadan). So much for the Versailles rules clarifying things for we now had the complex river boundary delimitation mentioned above.

River Jordan

The western boundary of Transjordan, as specified in Article 25 of the Palestine Mandate, was defined in the following manner:

The territory lying to the east of a line drawn from a point two miles west of the town of Aqaba on the Gulf of that name up the centre of the Wadi Araba, Dead Sea and River Jordan to its junction with the Yarmuk: hence up the centre of that river to the Syrian frontier. (Article 25 of the Palestine Mandate, Geneva, 23 September 1922)

For its sheer vagueness, this rivalled Britain’s threadbare definition of the Iraq–Kuwait boundary or the line it would initially set for Iraq and Syria with France in 1920 – where hundreds of miles of boundary were supposedly specified in three or four lines of text (Schofield, Citation2008b). Admittedly, this was not seen at the time as a burning issue with Palestine and Transjordan coming under the same mandate and, partly for this reason, there was not the same two-stage process of colonial boundary delimitation we had witnessed from Britain elsewhere in the Middle East, where a territorial deal hatched in European corridors of power would be followed invariably by its reconciliation to local surficial realities by commission or the like (Schofield, Citation2008b). Here, no surveys were undertaken, no lines on maps had been seriously considered and no consideration made of what was mean by the centre of the succession of hydraulic divides that constituted the boundary.

The ambiguities and difficulties resulting from such a lack of exactitude would soon make themselves apparent. Within five years, an instance of avulsion in the Jordan River led Lord Plumer, Britain’s High Commissioner in Jerusalem, to ask what precisely was meant by a boundary running ‘up the centre of the […], River Jordan […]’. For in February 1927 the Jordan burst its banks and, pretty much overnight, cut a new course for some 500 m in the Beisan subdistrict. Consequently, an area of some 800 dunums that had originally belonged to Palestine now found itself east of the river’s new course. With the original riverbed dry and debris-ridden, the British authorities now sought clarification as to whether the ‘transferred territory’ remained Palestinian or Transjordanian (Law, TNA, Citation1927, CO 733/142/1).

So Plumer commissioned the Colonial Office to conduct a survey of other river boundaries in an effort to establish whether it was the norm in such instances for the old channel course to be maintained as the boundary or for the new shifted course to be adopted. On 27 July 1927, the Colonial Office reported back as follows:

It will be observed from this memorandum that according to a general rule of International Law, the gradual shifting of the thalweg from one side of the river to the other by reason of imperceptible erosion of accretion of its banks, has the effect of changing the boundary to a corresponding degree. If, however, the river should, by a process known as avulsion, suddenly become diverted from its regular channel, the boundary line remains where it was before the change. (Oliphant, TNA, Citation1927, CO 733/142/1)

Yet Field’s survey of past state practice presented anything but a clear picture. The general rule of international law referred to in the above quotation followed Judge Caleb Cushing’s famous 1853 opinion on the effect that a change of course in the Rio Grande had on the coincident international boundary between the United States and Mexico.Footnote2 However, Field reviewed other examples and contexts where there had been change to the course of rivers that formed international boundaries and where this principle had not been followed: Belgium/the Netherlands and the Scheldt, 1842; Germany/(Polish) Russia, 1888 (River Drewens); Germany/Austria, 1898 (River Prezemsa); and Britain/Italy, 1891–1911 (River Juba). These outcomes reflected a pronouncedly individualistic ‘horses for courses’ approach with little concurrence in inter-state or colonial practice (Field, TNA, Citation1927, CO 733/142/1).

With no definitive guide as to how the Jordan should be treated, the Colonial Office went along with the view earlier expressed by the Survey of Palestine:

the Jordan is unique and should be treated as a special case in which it is necessary to adopt the natural boundary of the river itself, wherever it is? The fact that the river describes a course of some 200 miles in a distance of 65 miles is sufficient evidence of its unstable and eccentric nature. (Leys, TNA, Citation1927, CO 733/142/1)

So an interpretation was made of the vague 1922 Jordan River delimitation that seemed the most practical to manage at a local level. Plumer’s decree of 12 September 1927 flew in the face of most conventional legal interpretations. First, a thalweg was prescribed for a non-navigable river and, second, it was being proposed that the boundary moved with any shift in the main river channel, even when this was being occasioned by sudden, violent physical change (i.e., avulsion): ‘[t]his decision will involve periodical minor changes in the boundary as the “thalweg” of the river shifts, but will probably prove to be the most practical solution of the question’ (Kirkbride, 12 September Citation1927).

The Chobe and Bahr al-Arab rivers

The International Court of Justice gained jurisdiction to treat the dispute between Botswana and Namibia over boundary alignment and island sovereignty in the Chobe River by a special agreement of 15 February 1995 (Shaw & Evans, Citation2000), the kind of reference the court prefers since not only was the substance of dispute clearly articulated but the main legal source of evidence it wanted interrogating also clearly identified:

The Court is asked to determine, on the basis of the Anglo-German Treaty of 1 July 1890 [an agreement between Great Britain and Germany respecting the spheres of influence of the two countries in Africa] and the rules and principles of international law, the boundary between Namibia and Botswana around Kasikili/Sedudu island and the legal status of the island. (International Court of Justice, 13 December 1999)

It would soon become clear that the case was likely to revolve around the identity of the ‘major channel’ mentioned in the text of the 1890 spheres of influence agreement, one of whose chief effects was to provide Germany with access to the Zambezi River and Victoria Falls through the extended land corridor created for that purpose: the Caprivi Strip.Footnote3

How might one recognize the major channel when a river divides into two or more channels. Here is what the ruling in the 1966 Chile/Argentina arbitration case had to say:

Where an instrument (such as a treaty) has laid down that a boundary must follow a river, and that river divides into two or more channels and nothing is specified in that instrument as to which channel the boundary shall follow, the boundary must normally follow the major channel. (United Nations, Citation2006)

American boundary delimitation expert Stephen Jones had earlier commented that:

(t)he allocation of islands in rivers has been handled in a number of ways. The Paris treaties provided that the boundary should follow the ‘principal branch’ about islands and shoals. ‘Principal’ might mean widest, deepest, most used or carrying the most water. (Jones, Citation1945, p. 113)

With no detailed specification in its text as to what was meant by the major channel, it was always most likely that the intent of the parties to the 1890 agreement would be unearthed in the records of negotiations that led to the instrument being included.

The 2008–09 Abyei case at the Permanent Court of Arbitration would soon effectively fixate upon the status of the provincial boundary between the Sudanese provinces of Kordofan and Bahr al Ghazal in 1905, just six years into the establishment of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Administration. This was because the key historical mechanism for identifying the territorial extent of Abyei revolved around the transfer that year of the Ngok Dinka tribe from Bahr al Ghazal to Kordofan with a presumption that either the boundary between the provinces or the extent of territory inhabited by the tribe (both north and south of the Bahr al-Arab River) must have been known.Footnote4 Abyei had played host to some of the worst violence witnessed in two bloody Sudanese civil wars and the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 9 January 2005 tried symbolically to make territorial definition of the province a bridge going forward to the peaceful coexistence of two Sudans – one old and established and one new. Once its territorial extent was established, the inhabitants of Abyei could vote in a referendum to join one or the other state – at least, that was the idea (Born & Raviv, Citation2017). Later in 2005, the findings of the Abyei Boundary Commission (ABC) – a group of recognized experts commissioned purposefully to define Abyei territorially – that the province should extend some distance north into Kordofan were rejected by Sudanese President Bashir, with reports that his immediate reaction was to suggest their report be thrown back into the Sudd from whence they came (confidential source). Hence, the reference of Abyei to the Permanent Court of Arbitration – with the missive being to establish whether the ABC had exceeded its mandate in defining the province so extensively and, should that be found to be the case, to lay down a more appropriate one and a more suitable basis for doing so (Born & Raviv, Citation2017).

On the face of it, the territorial argument maintained by the Government of Sudan during the case that Abyei province should extend no further north than the Bahr al Arab River seemed to possess some validity. For there were references, albeit generally vague ones, to the Bahr al-Arab as constituting the provincial boundary made by the governors of Kordofan and Bahr al-Ghazal provinces in the first half-decade of the 20th century, while it was even itemized as such in more than one colonial administration report around this time (Schofield & Allan, Citation2009, p. 14). Bahr al-Ghazal province under Ottoman–Egyptian rule had been characterized spatially as follows: ‘This “mudirieh” was vaguely defined, but may be described as enclosing the entire district watered by the southern tributaries of the Bahr al Arab and the Bahr al Ghazal Rivers’ (Gleichen, Citation1905, pp. 2, 151). Even at provincial level, the colonial mindset would probably have worked for the presumption of rivers as boundaries around this time, even if the above quotation hinted at the possibility that the entirety of the riverine area might lie within the province of Bahr al-Ghazal. Whatever, it is fair to say no agreed delimitation was in place along the Bahr al-Arab in 1905 – something the 1911 Handbook on the Sudan specifically confirmed a half-decade on (Government of Sudan Memorial, Citation2009, p. 376). Nothing had been agreed centrally in Khartoum or back in London.

Ottoman territorial limits on whatever scale were often indeterminate, shifting and impermanent (Schofield, Citation2018) but what contributed most to the prevailing uncertainty in 1905 concerning the status of any Bahr al-Arab provincial boundary was Britain’s confusion as to where the riverine feature lay. In particular, the Ragaba as-Zarga (Ngol) and Bahr al-Arab (Kiir) rivers were frequently confused with the former often mistaken for the latter by all levels of British officialdom in Sudan, not to mention a great number of travellers to this largely unexplored region. The same governors who thought the Bahr al-Arab was probably the provincial boundary demonstrably did not know where it was, even Governor-General Wingate made the same mistake of confusing the two rivers. Logically, therefore, or so the south (SPLM/A) argued in the case, any putative Bahr al-Arab boundary must have been indeterminate and indefinite in 1905 – there had been no central allocation, never mind delimitation while significant leading Condominium personnel did not know where it was (Schofield & Allan, Citation2009, p. 2).

As to whether the Bahr al-Arab might have constituted a barrier to local movement, historical research into the physical geography unearthed in service of the SPLM/A’s case was used to argue that the riverine ‘Bahr region’ was both discernible, indeed measurable and presented no such impediments:Footnote5

the Kiir/Bahr al-Arab is not a physical barrier, and would not present a meaningful obstacle to the movement of the Ngok Dinka and their cattle, save perhaps in very limited parts of the rainy season […] the whole of the Bahr region (as well as some parts of the goz) would support the Ngok Dinka agro-pastoral culture and way of life. (Schofield & Allan, Citation2009, p. 2)

Uncertainty was the watchword here though. Britain’s geographical knowledge half a decade into the Condominium administration of a region that exhibited huge seasonal variations was unsurprisingly threadbare. No wonder the identity of water course was so confused. Not that much had been explored by this stage, never mind surveyed and very few stretches of channels that were potentially navigable had been cleared. In reality, negotiating the Bahr al-Arab depended on whether the dry or wet season was being experienced.

the river bed of the Kiir/Bahr el Arab varies in its course through the Abyei Region from continuous flow to areas of discontinuity along its length during the dry season. […] In the high wet season during July/August it will flood, and its banks and areas around them will be under water. During this the river would in some years prevent passage by humans. However, outside of those limited times and particularly in the driest months from November to May, the Kiir/Bahr el Arab is a comparatively gentle one that is not particularly deep. (Schofield & Allan, Citation2009, pp. 27–28)

Contemporary outcomes: old and new in river boundary dispute settlement

Shatt al-Arab

The complex regional geopolitics that were in large part responsible for the conclusion of the breakthrough package of territorial settlements between Iran and Iraq during 1975 cannot disguise the fact that with agreement on a thalweg delimitation for the Shatt, a long-standing Iranian positional demand had been satisfied and Palmerston’s original mid-19th-century recommendation realized (Kaikobad, Citation1988; Schofield, Citation2004). The 1975 package constituted a sophisticated legal river boundary settlement by any reckoning. Let us concern ourselves here with how the thalweg was elaborated and how the contingency of future physical change in the boundary estuary would be regulated and managed. The geopolitics have been covered elsewhere (Schofield, Citation2021).

The 6 March 1975 Algiers Accord simply announced that Iran and Iraq had ‘decided to delimit their river frontiers on the thalweg line’ (United Nations, Citation1975). A fortnight later it was announced that arrangements had been made for the establishment of a tripartite committee (including technicians from Algeria, who had mediated the accord) ‘to determine the water border in the Shatt al Arab estuary on the basis of the thalweg principle’ (telegram from Tehran, TNA, Citation1975, FCO 8/2547). Within a couple of months, a thalweg delimitation had been established on the basis of surveys undertaken by the said committee in time for the conclusion in Baghdad on 13 June 1975 of the ‘Treaty Relating to the State Boundary and Good Neighbourliness between Iraq and Iran’ (United Nations, Citation1975). The boundary treaty was supplemented by three protocols, including a ‘Protocol Relating to the Delimitation of the River Frontier between Iraq and Iran’. Its first article declared that ‘the State river frontier between Iran and Iraq in the Shatt al-Arab has been delimited along the thalweg’ (United Nations, Citation1975). Attached to the Article 1 were four (British Admiralty) charts upon which the delimitation was plotted (Schofield, Citation2009, vol. 18, maps 27–30).

Article 2 was where things got interesting and perhaps where the pudding got over-egged – most pointedly in anticipating future physical change in the waterway. More so than in any other river boundary treaty signed before this time, the thalweg was defined in exacting terms in its first paragraph (though the mixture of its key terms – median line and thalweg – could be seen as a little confusing):

The frontier line in the Shatt al-Arab shall follow the ‘thalweg’, i.e., the median line of the main navigable channel at the lowest navigable level, starting from the point at which the land frontier between Iran and Iraq enters the Shatt al-Arab and continuing to the sea. (United Nations, Citation1975)

Article 2’s second paragraph specified that the new thalweg line would ‘vary with changes brought about by natural causes in the main navigable channel’ unless the parties agreed otherwise, with the third establishing that technical teams from both states would have to confirm and attest to such occurrences. This was anticipating gradual change via erosion and accretion as foreseen by the 1919 Versailles rules. Things got more specific and detailed in dealing with the contingency of sudden physical change in the riverbed. Paragraph 4 held that:

[a]ny change in the bed of the Shatt al-Arab brought about by natural causes which would involve a change in the national character of the two States’ respective territory or of landed property, constructions, or technical or other installations shall not change the course of the frontier line, which shall continue to follow the thalweg in accordance with the provisions of paragraph one above. (United Nations, Citation1975)

Paragraph 5 of the River Protocol’s Second Article went on to specify what ought to be done in such a contingency, with its bizarre provision for the possible transfer of the river back to the boundary:

Unless an agreement is reached between the two Contracting Parties concerning the transfer of the frontier line to the new bed, the water shall be re-directed at the joint expense of both parties to the bed existing in 1975 – as marked on the four common charts listed in article one […] – should one of the Parties so request within two years after the date on which the occurrence of the change was attested by either of the two Parties. Until such time, both Parties shall retain their previous rights of navigation over the water of the new bed. (United Nations, Citation1975, emphasis added)

Article 6 of the river boundary protocol committed the two sides to jointly survey the main river channel afresh every 10 years, or even more frequently should one of the parties request as much. War and conflict pretty much ever since has meant that acting on its provisions was never a practicable possibility, at least until recently. Prospectively, the announcement of 11 March 2019 on Hassan Rouhani’s first visit to Baghdad as Iranian President that agreement had been reached to renew the 1975 river boundary arrangements is significant (Schofield, Citation2021, p. 11). For some time before then, though, it had seemed that remaining disputes were less about whether the 1975 regime is applicable – both sides broadly agreed that it was – and more about how details might be implemented in any new settlement.

As for recent physical change in the Shatt’s main navigable channel, a willingness to broach any associated problems has accompanied not just better relations between Baghdad and Tehran but also acknowledges a post-conflictual context of regional reconstruction. Nonetheless, Iraq is known to be frustrated that channel movement has all been to the south and west of the coordinates officially nominated for the Shatt’s southernmost reaches in 1975, with some law-makers casting doubt on whether this has all been down to nature. It was maritime incidents of summer 2004 and spring 2007, involving the capture of British sailors by Iranian patrols near the estuary mouth, that also drew attention to the absence of a territorial waters boundary between Iran and Iraq south of the terminal point of the 1975 river boundary delimitation. One important consequence of the first incident had been that Iran and the occupying powers (the US and UK) would apparently agree that the current position of the thalweg as it existed at any one time along the Shatt would serve as an operative international boundary (Schofield, Citation2021, pp. 14–15).

River Jordan

In famously signing their Common Agenda in Washington on the White House lawn on 14 September 1993, Israel and Jordan agreed inter alia the basis upon which they would negotiate a full boundary agreement over the following year. Paragraph 5 of the Israel–Jordan Common Agenda on Borders and Territorial Matters read as follows:

Settlement of territorial matters and agreed definitive delimitation and demarcation of the international boundary between Israel and Jordan with reference to the boundary definition under the Mandate, without prejudice to the status of any territories that came under Israeli Military Government control in 1967. Both parties will respect and comply with the above international boundary. (Schofield & Allan, Citation2010)

Just over a year on, ‘The Treaty of Peace between the State of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan’ was signed by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Jordanian Prime Minister Abdul Salam Majali on 26 October 1994. Article 3 of a long document (with its annexe and appendices) defined and regulated their international boundary. The first four paragraphs (of nine) in the article provided for boundary definition, regulation and future demarcation. Paragraph 1 reiterated that the vague old 1922 colonial delimitation remained the definitional basis of the Israel–Jordan boundary.

The international boundary between Israel and Jordan is delimited with reference to the boundary definition under the Mandate as is shown in Annex I (a), on the mapping materials attached thereto and co-ordinates specified therein. (United Nations, Citation1995)

The first annexe to the treaty was entitled ‘Israel–Jordan International Boundary Delimitation and Demarcation’ and described the basis of delimitation for four specified stretches of the boundary, respectively: the Jordan and Yarmuk rivers; the Dead Sea; Wadi Araba, and the Gulf of Aqaba:

For the Jordan river, Britain’s definitional clarification of 1927 was basically retained for, without employing the term specifically, the boundary was defined as running along the thalweg of the Jordan river.

The boundary line shall follow the middle of the main course of the Jordan and Yarmouk rivers. (United Nations, Citation1995)

More flexibility, however, was granted to Jordan and Israel in dealing with future natural change in the main channel of the river than had been provided all those years ago by the Colonial Office in 1927. While it was confirmed that the boundary would move with gradual shifts in the main channel occasioned by accretion, a newly appointed Joint Boundary Commission would meet to consider the most appropriate course of action in future cases of avulsion, with all options remaining open to them.

Chobe River

On 13 December 1999, the International Court of Justice announced its ruling with respect to the sovereignty of Kasikili/Sedudu island in favour of Botswana by 11 votes to four, thereby also decreeing that the northern channel of the Chobe River was the main one. Yet, even so, both states would have equal navigation rights in each of the river’s channels north and south of the island (International Court of Justice, Citation1999). Three items seem worthy of discussion, given the concerns of this article: the local human context, identification of the main channel, and a judgment that seemingly wanted to address both top-down and ground-up aspects simultaneously.

Traditional, seasonal usage of the insular feature in question – which is only 3.5 km2 in size and is generally flooded for a third of the year from March onwards – led to Namibia advancing a claim of prescriptive title based upon the Caprivi-based Masubia tribe’s use of it for herding cattle. The two disputing parties had agreed a four-stage definition of prescription prior to the case which, in the International Court of Justice's ruling, the Masubia’s historical actions did not satisfy (Shaw & Evans, Citation2000).

The Court finds that while the Masubia of the Caprivi Strip (territory belonging to Namibia) did indeed use the Island for many years, they did so intermittently, according to the seasons, and for exclusively agricultural purposes, without it being established that they occupied the Island à titre de souverain, that is, that they were exercising functions of State authority there on behalf of the Caprivi authorities. The Court therefore rejects this argument (International Court of Justice, Citation1999).

As for identification of the Chobe’s main channel, there were hints and implications in the textual negotiation record of the 1890 Anglo-German spheres of influence treaty that it would have laid to the north of the island feature but nothing definitive – neither was there any mapping of suitable scale and detail that could indicate the intentions of the rival imperial powers. Likewise, a thorough survey of navigational practice up to Botswanan independence in 1966 and Namibia’s a quarter century later did not point to any agreed interpretation of the principal channel. This all only underlined that in the scheme of things, local as well as regional, this had not been a particularly significant river boundary dispute. So, the International Court of Justice effectively took it upon it itself to determine the major channel by running through Jones’ old checklist of indicators earlier itemized in this article:

In order to do so, it [took] into consideration, inter alia, the depth and the width of the channel, the flow (that is, the volume of water carried), the bed profile configuration and the navigability of the channel. After having considered the figures submitted by the Parties, as well as surveys carried out on the ground at different periods, the Court concludes that ‘the northern channel of the River Chobe around Kasikili/Sedudu Island must be regarded as its main channel’. (International Court of Justice, Citation1999)

So with its identification of Kasikili/Sedudu as Botswanan in sovereign terms, what lay behind the International Court of Justice's specification here that there would be ‘unimpeded navigation for craft of [Namibian] nationals and flags in the channels of Kasikili/Sedudu island […] a treatment equal to that accorded by Botswana to its own nationals and to vessels flying its own flag’ (International Court of Justice, Citation1999). Was it to soften the blow of a sovereign decision when the historical indicators had not been overwhelming in a (relatively) obscure dispute and which, in many ways, contradicted local patterns of traditional usage? Or did it genuinely reflect more progressive thinking with respects to the local management and implementation of inter-state boundary awards? After all, fairly prominent reference was lent to the 1997 Convention on the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which defines a watercourse as a ‘system of surface waters and ground waters constituting by virtue of their physical relationship a unitary whole flowing into a common terminus’ (United Nations, Citation2014).

Abyei/Bahr al-Arab

The PCA’s award of 22 July 2009 would subsequently be sharply castigated by the lead in the SPLM/A’s legal team during the Abyei case: ‘Decisions like the Abyei Award provide sobering reminders of the shortcomings of the international legal system and its capacity to resolve interstate disputes’ (Born & Raviv, Citation2017, p. 224). Such comments referenced the tribunal’s procedural deliberations more widely but also, more specifically, its rejection of the northern limits for the ‘Abyei area’ earlier recommended by the Abyei Boundary Commission – with the tribunal’s seeming dismissal of their supporting arguments. It will be recalled that there were competing tribal and territorial arguments at work in the case supporting Abyei’s areal definition and, specifically, interpretation of the 1905 tribal transfer. On one hand, the 2009 Abyei award concluded that the ABC had not exceeded its mandate in calculating northern limits on the basis of its tribal formula but, on the other, it moved these significantly southwards, truncating the defined territorial extent of the ‘Abyei area’ by some 40% from 18,559 to 10,460 km2 (Born & Raviv, Citation2017, p. 1.

The above quotation might also be extended more widely to refer to what was being attempted with the specified basis of dispute resolution here – establishing what lay in place on the ground over a century earlier in a seasonally flooded area of central Sudan and whether a provincial boundary could be held to be in existence there. We have already seen just how vague and ambiguous imperial boundary delimitations could be but here we were talking about a provincial divide and colonial evidence was always likely to be even more threadbare, flimsy and uncertain (Schofield, Citation2015, p. 140). Hence, a wider array of evidence needed to be relied upon and considered in the Abyei case than is usual in territorial cases – mapping surveys, travellers’ reports, burial sites and oral histories, testimonies and traditions.

For the reasons elaborated above, it was little surprise when Khartoum’s claim that the Bahr al-Arab constituted an inter-provincial colonial boundary in 1905 (and therefore the northern territorial limits of Abyei) failed to find favour in the July 2009 Permanent Court of Arbitration award. For starters, no delimitation could be held to have been in place at the time along the river,Footnote6 even had the Condominium government known with more certainty which riverain feature it comprised. If the prevailing lack of geographical knowledge of the Abyei region at the turn of the 20th century on Britain’s part worked against any prospect of a river boundary materializing with the Permanent Court of Arbitration July 2009 award, late 19th-century characterizations of the possible extent of the Ottoman province of Bahr al-Ghazal as an essentially riverain area perhaps found partial expression. Any quick perusal of the territorial outcome of the award would confirm that the south ended up with pretty much all of the rivers whose identity and configuration had been at the heart of the territorial arguments put forward by Sudan in the case.

Conclusions

Despite the development of guidelines for drawing boundaries along rivers at Versailles during 1919, there would continue to be wide variability in the manner by which delimitations were selected or agreed upon by states for specific physical contexts and regional constellations – horses for courses, if you like. Pronounced individuality in river boundary regimes in international law reflects, after all, the innate complexity of this class of delimitation: the challenge of reconciling the top-down desiderata that dictated their nomination in the first instance with the live ground-up realities and challenges posed by physical change in channel alignment and the evolving socio-economic development of the adjoining areas.

The Shatt and Jordan cases demonstrate obviously different legal approaches to refining and regulating an international river boundary, which is to be expected since the former is navigable and the latter non-navigable. Although the regional geopolitics that drove their conclusion were wholly decisive, the 1975 package of Iran–Iraq agreements constitute in many ways a model river boundary settlement, with the most appropriate delimitation from a legal and regional perspective defined in exacting terms and the contingency of future physical change dealt with at length. Conversely, Jordan and Israel kept with a threadbare colonial delimitation and management approach in their territorial settlement of 1993–94, even though these arrangements ran contrary to the Versailles rules. Instead of specifying an elaborate regime for sudden, avulsive change – as did Iran and Iraq in their June 1975 river boundary protocol, Israel and Jordan simply agreed to meet up should this eventualize – and decide upon the most appropriate course of action. The approach taken to the Jordan seemingly affords more flexibility and the prospect of sudden changes in the riverbed has always been much greater here than with the main channel of the Shatt al-Arab, where recent change – though significant – has been of a gradual accretional character.

The use made of history in guiding the dispute resolution process in the 1995–99 Kasikili/Sedudu island and 2008–09 Abyei cases at the International Court of Justice and Permanent Court of Arbitration, respectively, demanded the clarification of the major channel of the Chobe River in the first instance and suggested the possibility for a river boundary delimitation along the Bahr al-Arab in the second. Yet the status of the rivers was anything but a live, regional issue for the colonial powers in 1890 and 1905, respectively, the key historical dates decided upon for dispute resolution. Given that evidence was resultantly threadbare for the existence of the Chobe’s major channel back then and the Abyei region was essentially unexplored, such prevailing uncertainty had to be acknowledged thoughtfully in resolving these disputes. The PCA’s spatial characterization of Abyei as a riverain area tallied to some extent with late 19th-century descriptions and also nodded in some ways, without saying as much, to the arrangements reached by Britain and Italy over the Juba in 1911 – where the greater river valley area was seen as an operative border region. As for the Chobe River, the court decided that through Botswana had argued the merits for sovereign ownership over Kasikili/Sedudu, use of the channels on either side would be free to nationals of both states. This stipulation was couched progressively with reference made to the 1997 UN Non-Navigational Use of Waterways Convention – perhaps the Institute of International Law’s 1911 Madrid Resolution could also have been invoked! Maybe this effective instruction to cooperate over the boundary river reflected a slight uneasiness on behalf of the court over its rejection of Namibia’s prescriptive arguments and the lack of definitive evidence for what had been its major channel in 1890. River delimitation settlements have always required more local management than other classes of international boundary but here was a legal resolution that took steps to guide it.

The recent legal settlement and management of complex international river boundary questions shows signs of balancing localized human and environmental context with the specific individual histories and geopolitics of the territorial limits in question. Perhaps there is an opportunity for more critical academic engagement with their socio-spatial characteristics, both historically and contemporaneously – one that addresses their localized human dynamics more fully than traditional approaches.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Matthew Tillotson for his useful comments on an earlier draft and also three individuals who, like Tony Allan, are sadly no longer with us but with whom I have enjoyed so many great conversations about river boundaries over the years: Mike Burrell, Kaiyan Kaikobad and Keith McLachlan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The author and Tony Allan were involved together with the dispute resolution process in two of these cases. In conjunction with Tony’s late colleague, Keith McLachlan, we put together a Report on Jordan’s Western Boundary during 1993–94 in conjunction with Jordan’s Royal Scientific Society (Geopolitics Research Centre, Citation1994) with Tony leading on water and myself on territorial issues. Fast forward one-and-a-half decades to February 2009, we later co-authored a report entitled The Boundaries and Hydrology of the Abyei Area, Sudan (referred to as the Menas Borders report in subsequent court proceedings) (Schofield & Allan, Citation2009) to support the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army’s (SPLM/A) case at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Abyei case. We would then defend this under cross-examination a couple of months later at the hearings stage of the case when appearing as expert witnesses for the SPLM/A.

2. This general rule would later be summed up neatly by a 1970 US Supreme Court decision (Arkansas vs. Tennessee, 1970): ‘It is settled beyond the possibility of dispute that where running streams are the boundaries between States, the same rule applies as between private proprietors, namely, that when the bed and channel are changed by the natural and gradual processes known as erosion and accretion, the boundary follows the varying course of the stream; while if the stream from any cause, natural or artificial, suddenly leaves its old bed and forms a new one, by the process known as an avulsion, the resulting change of channel works no change of boundary, which remains in the middle of the old channel, although no water may be flowing into it, and irrespective of subsequent changes in the new channel’ (US Supreme Court, 25 February 1970).

3. Imperial access to the continent’s prominent physical features was seen as a prestige indicator, hence the Kenya/Tanzania boundary was reputedly defined in a manner that shared colonial control of East Africa’s two highest mountains, Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro – a sort of natural boundaries mindset writ large!

4. Hence during the Permanent Court of Arbitration case, the SPLM/A (South) went for a tribal interpretation that reflected the extent of territory inhabited by the Ngok Dinka in 1905, while the Government of Sudan went for a more conventional territorial interpretation that argued for the existence of a known provincial river boundary (Born & Raviv, Citation2017).

5. ‘The Bahr region extends south from the boundary of the ‘go’z area in the west of Southern Kordofan at a latitude of approximately 10 degrees 0 minutes N, and south from Lake Keliak in the east of Southern Kordofan, and encompasses the areas around the Ngol/Ragaba ez Zarga and Kiir/Bahr el Arab’ (Schofield & Allan, Citation2009, p. 1).

6. In its definition of delimitation, the Permanent Court of Arbitration relied upon what this author had said in court during the hearings stage in April 2009: ‘As explained by […] Schofield, there are three stages in a boundary’s evolution: allocation, delimitation and demarcation. Allocation deals with allocating territory and not the actual boundary, while demarcation simply physically marks out the boundary on the ground. Delimitation, quite differently, is when the line is established and specified. It requires “an executive act” of determining where the actual boundary line should be, and calls for a detailed description of the location of a boundary line’ (SPLM/A Oral Pleadings, 22 April 2009, Transcr.121/03-122/02).

References

- Anghie, A. (2006). The evolution of international law: Colonial and postcolonial realities. Third World Quarterly, 27(5), 739–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590600780011

- Bialasiewicz, L., & Minca, C. (2010). The `border within’: Inhabiting the border in Trieste. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(6), 1084–1105. https://doi.org/10.1068/d2609

- Born, G., & Raviv, A. (2017). The Abyei arbitration and the rule of law. Harvard Journal of International Law, 58(1), 177–224.

- Bouchez, L. J. (1963 July). The fixing of boundaries in international boundary rivers. International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 12(3), 789–817. https://doi.org/10.1093/iclqaj/12.3.789

- British Embassy, Tehran to FCO. 18th March 1975 in TNA file: FCO 8/2457.

- Demeritt, D. (1997). Representing the ‘true’ St. Croix: Knowledge and power in the partition of the Northeast. William and Mary Quarterly, 54(3), 515–548. https://doi.org/10.2307/2953838

- Donaldson, J. (2009). Where rivers and boundaries meet: Building the international river boundaries database. Water Policy, 11(5), 629–644. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2009.065

- Donaldson, J. (2014). Re-thinking international boundary practices: Moving away from the ‘edge. In F. McConnell, N. Megoran, & P. Williams (Eds.), Geographies of peace (pp. 89–108). Tauris.

- Fall, J. (2010). Artificial states? On the enduring geographical myth of natural borders. Political Geography, 29(3), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.02.007

- Field, J. W. (1927). Foreign Office memorandum on the effect of deviation of rivers on boundaries. 7th October 1927 in TNA file: CO 733/142/1. Unpublished.

- Geopolitics Research Centre, SOAS. (1994). Report on Jordan’s western boundary.

- Gleichen, E. (ed.). (1905). The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A compendium prepared by officers of the Sudan government (Vol. 2). War Office.

- Government of Sudan. (2009). Memorial. Government of Sudan v. SPLM/A (Abyei), Permanent Court of Arbitration.

- Holdich, T. (1916, June). Geographical problems in boundary making. The Geographical Journal, 47(6), 421. https://doi.org/10.2307/1779240

- Hubbard, G. E. (1916). From the Gulf to Ararat, Blackwood, Edinburgh (2016 centenary edition published as from the Gulf to Ararat: Imperial boundary-making in the late Ottoman Empire. IB Tauris. with a preface by Richard Schofield.

- International Court of Justice. (1999). ICJ finds that Kasikili/Sedudu Island forms part of the territory of Botswana. Press release, ICJ/594. Retrieved December 13, 1999 from https://www.un.org/press/en/1999/19991213.icj594.doc.html

- International Court of Justice (2017–22). Land, Island and maritime frontier dispute (El Salvador/Honduras: Nicaragua intervening). https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/75/judgments

- Jones, S. P. (1945). Boundary-making: A handbook for statesmen, treaty editors and boundary commissioners. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Kaikobad, K. (1988). The Shatt-al-Arab boundary question: A legal reappraisal. Clarendon Press.

- Kirkbride, A. (1927 September 12). High Commissioner for Palestine and Transjordan to the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Letter, TNA file: FO 816/23.

- Lauterpacht, E. (1960). River boundaries: Legal aspects of the Shatt al-Arab frontier. International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 9(2), 208–236. https://doi.org/10.1093/iclqaj/9.2.208

- Law to the Chief Secretary, Government Offices, Jerusalem. 5th April 1927 in TNA file: CO 733/142/1.

- Leys to the Chief Secretary, Government Offices, Jerusalem. 21st April 1927 in TNA file: CO 733/142/1.

- Menas Borders. (2010). Jordanian boundaries and border geopolitics.

- Murphy, B. (1990). Historical justifications for territorial claims. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 80(4), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1990.tb00316.x

- O’Dowd, L. (2010). From a borderless world to a ‘World of Borders’: Bringing history back in. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(6), 1031–1050. https://doi.org/10.1068/d2009

- Oliphant to the Under Secretary of State, Colonial Office. 12 July 1927 in TNA file: CO 733/142/1.

- Palmerston to Bloomfield. 3rd March 1847 in TNA file: FO 78/2716.

- Prescott, J. R. V., & Triggs, G. D. (2008). International frontiers and boundaries: Law, politics and geography. Martinus Nijhoff.

- Schofield, R. (2004). Position, function and symbol: The Shatt al-Arab dispute in perspective. In L. G. Potter & G. G. Sick (Eds.), Iran and Iraq and the legacies of war (pp. 29–70). Palgrave Press.

- Schofield, R. (2008a). Narrowing the frontier: Mid-nineteenth century efforts to delimit and map the Perso-Ottoman boundary. In R. Farmanfarmaian (Ed.), War and Peace in Qajar Persia (pp. 149–173). Routledge.

- Schofield, R. (2008b). Laying it down in stone: Delimiting and demarcating Iraq’s boundaries by mixed international commission. Journal of Historical Geography, 34(3), 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2007.11.002

- Schofield, R. (ed.). (2009). Arabian boundaries: New documents, 1966–1975. Cambridge Archive Editions (Cambridge University Press).

- Schofield, R. (2015). Back to the barrier function: Where next for international boundary and territorial disputes in political geography? Geography, 100(3 (Autumn 2015)), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2015.12093968

- Schofield, R. (2018). British bordering practices in the Middle East before Sykes–Picot: Giving an edge to zones. Égypte/Monde arabe, 18(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.4000/ema.4279

- Schofield, R. (2021). Back to 1975 and all that: Linking the technicalities and underlying dynamics of Iraq’s border disputes at the head of the Persian Gulf. In G. Joffe & R. Schofield (Eds.), Geographic realities in the Middle East and North Africa: State, oil and agriculture (pp. 11–24). Routledge.

- Schofield, R., & Allan, J. A. (2009). The boundaries and hydrology of the Abyei Region, Sudan. Expert report submitted to the PCA, signed on 11th February 2009 by Schofield and Allan.Menas Borders. Submitted with the SPLM/A Counter-Memorial.

- Sevette, P. (1952 January). Legal aspects of the hydro-electric development of rivers and lakes of common interests, committee on electric power of the United Nations. Economic Commission for Europe. (Doc E/ECE/136).

- Shaw, M., & Evans, M. (2000). Case concerning Kasikili/Sedudu Island (Botswana/Namibia). International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 49(4), 964–978. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020589300064782

- Simpson, T. (2021). The frontier in British India: Space, science, and power in the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Tillotson, M. (2020). Nature, space and distances in an imperial boundary network: The delimitation of the Nyasa–Tanganyika plateau boundary. Political Geography, 76(1), 102081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102081

- United Nations. (1975). Treaty Series, 1017, 14903.

- United Nations. (1995). The question of Palestine: ‘Letter dated 9 January 1995 from the permanent representatives of Israel, Jordan, the Russian federation and the United States of America to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General’. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-179122/

- United Nations. (2006). Reports of international arbitral awards: Argentina–Chile frontier case. xvi, 109–192. Retrieved December 9, 1966, from https://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/vol_XVI/109-182.pdf

- United Nations. (2014). Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational uses of International Watercourses 1997 [Adopted by the general assembly of the United Nations on 21 May 1997. [Entered into force on 17 August 2014. See General Assembly resolution 51/229, annex, Official Records of the General Assembly, Fifty-first Session, Supplement No. 49 (A/51/49)], https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/8_3_1997.pdf

- van Houtum, H. (2005). The geopolitics of borders and boundaries. Geopolitics, 10(4), 672–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040500318522