ABSTRACT

Despite widespread recognition of the importance of data exchange in transboundary waters’ management, there is growing evidence that data exchange is falling short in practice. A possible explanation may be that data exchange occurs where and when it is needed. Needs for data exchange in shared waters, nonetheless, have not been systematically assessed. This paper evaluates data exchange needs in a set of transboundary basins and compares such needs with evidenced levels of data exchange. Our findings indicate that it may be possible to accelerate data exchange by identifying and promoting the exchange of data that respond to palpable need and serve practical use.

Introduction

Data and information exchange are universally recognized as central to fostering equitable and sustainable use of transboundary watercourses. The 1992 Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Water Convention) and the 1997 United Nations Convention on the Law of the non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (UN Watercourses Convention) call for the exchange of data across countries sharing a watercourse (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), Citation1992; UN, Citation1997). Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 6.5, and its associated indicators on integrated water resources management (IWRM) implementation (6.5.1) and transboundary water cooperation (6.5.2), recognize the importance of data exchange. Similarly, the SDG 6 Water and Sanitation Global Acceleration Framework highlights data and information as one of the five critical accelerators for decision-making, including when shared in transboundary basins (UN Water, Citation2020). Data exchange is indeed rooted in the principles of international customary law (Dellapenna, Citation2001; Leb, Citation2015) and forms part of the key principles of transboundary water law such as equitable and reasonable utilization and obligation not to cause significant harm. Emphasizing the importance of data exchange, the 1992 Water Convention’s Working Group on Monitoring and Assessment promotes the exchange of data through supporting guidelines and strategies for riparian countries (UNECE, Citation2023).

Challenges in the practical realization of data exchange are nonetheless widespread. Plengsaeng et al. (Citation2014) suggest behavioural barriers such as attitude and social pressure constrain data exchange in the Mekong. Nishat and Shams (Citation2013) described weak and fragmented basin-wide data-sharing efforts in the Ganges. Thu and Wehn (Citation1992) observed the weaknesses – namely, outdated information systems and a lack of in-country regulations – of practical data exchange in the Mekong from the Vietnamese perspective. Mukuyu et al. (Citation2020) found that while exchange of data on river flow occurs in more than 75% of basins, exchange of data on other key parameters such as water quality, water abstraction and groundwater levels occurs in less than half of basins; and the frequency of data exchange is often irregular.

Drivers of and constraints to data exchange – key to understanding how to promote more widespread sharing of data – are not well understood. Chenoweth and Feitelson (Citation2001) suggested compatibility of development plans’ needs may promote data-sharing. Plengsaeng et al. (Citation2014) explored the perception of limited benefits and concerns over national security as key ‘bottlenecks’ to data-sharing. Mukuyu et al. (Citation2020)Footnote1 tested whether the platform of exchange and presence of a data exchange protocol influenced levels of data exchange; such tests proved inconclusive. Milman et al. (Citation2020) suggest that exchanging data alone may not be sufficient to address basin specific needs and results in ‘knowledge gaps’. Further, not all data shared would be useful in different parts of the basin (Gao et al., Citation2022). Ultimately, the determination of factors that explain the widespread challenges in transboundary data exchange may require deeper investigation.

A potentially key but-as-yet unexplored factor relates to the extent to which evidenced data exchange realities are a function of data exchange needs. Needs assessments have been undertaken in the water sector but are most often focused on national department’s data needs and interoperability of data (Cantor et al., Citation2018; Rosen et al., Citation2019). In transboundary basins, no clear evidence could be found on whether water related data exchange needs assessments are undertaken as a precursor to determining which data should be exchanged. The extent to which formulation of data exchange protocols (e.g., International Sava River Basin Commission (ISRBC), Citation2014; Mekong River Commission, Citation2001; Zambezi Watercourse Commission (ZAMCOM), Citation2016), for example, are motivated by a need-based prioritization of data exchange parameters is unclear. While guidelines such as the 2006 UNECE ‘Strategies for Monitoring and Assessment of While global guidelines (e.g. UNECE, Citation2023) detail the importance of determining information needs in basin management, the extent of application has not been assessed.

The aim of the research conducted and reported here was to assess data exchange needs in a set of transboundary basins in order to compare these needs with the data that are actually exchanged.Footnote2 The paper first reviews fundamentals on needs assessments and data exchange, using this review to develop a framework and questionnaire for assessing data exchange needs in shared watercourses. The results from the framework’s application are then presented. A discussion and conclusion contextualize the results and offer recommendations on leveraging data exchange needs assessments to accelerate data-sharing in transboundary waters.

Background

Defining need

Need is defined simply as ‘a lack of something requisite, desirable, or useful’ (Merriam Webster Online Dictionary, Citation2001). Alternative interpretations of this straightforward definition nonetheless exist when applied in specific disciplines. Kaufman et al. (Citation1993) view need as the ‘gap’ between current and desired outcomes, while Stufflebeam et al. (Citation2012) treat ‘need’ within the context of necessity and usefulness for purpose. Borrowing from Bradshaw’s (Citation1972) classification of social needs, two types of needs were discerned and applied to data exchange needs: (1) expressed needs, which are communicated; and (2) felt needs, which are based on specific situations and tend to be experienced on an operational level.

What is a needs assessment?

Rooted in social sciences, needs assessments have been conducted extensively across disciplines such as public health, education and human resources (Stufflebeam et al., Citation2012; Wright et al., Citation1998; Gagne et al., Citation1992). So prolific are needs assessments that books have been written on evaluation methods that suit different audiences and situations (Kaufman et al., Citation1993; Reviere et al., Citation1996; Royse et al., Citation2009; Soriano, Citation2012; Witkin & Altschuld, Citation1995). Ultimately, needs assessments are important (1) to assess shortcomings, that is, determine gaps, and (2) to prioritize identified needs and inform resource allocation such as financial or human resources.

Needs assessments in water resources management

Needs assessments conducted in water management (e.g., United States Department of the Interior (USDOI), Citation2012) are often oriented towards determining water-use needs in basins, which typically entails assessing current water availability against future demands in key water-use sectors, including agriculture, energy, urban water supply and the environment. Greater adoption of IWRM approaches (Del Moral et al., Citation2014; Jeffrey & Gearey, Citation2006; McDonnell, Citation2008) has led to a broader set of needs assessments, focused in at least three key interlinked areas: (1) information needs assessments, for example, related to climate; (2) assessments of data requirements; and (3) training needs assessments to support capacity-building in practitioners (Burton & Molden, Citation2005; Scherer et al., Citation2017; Vera et al., Citation2010).

Assessing need for water data

In transboundary basins, Mirghani (Citation2012) and Vaessen and Brentführer (Citation2014) have undertaken needs assessments on the institutional capacity of basin organizations to integrate groundwater management. Cantor et al. (Citation2018) and Rosen et al. (Citation2019) assessed national departments’ water data needs by asking users to develop a possible range of decisions they would typically require data for – in what they term ‘use cases’ – as a way of determining the type and form of data needed. However, there is a dearth of literature on needs assessments for exchange of water data in transboundary basins.

Data exchange and technological advancement

There is growing acknowledgement that technological advances may eventually complement data exchange efforts, or potentially obviate the need for intensive exchange (Leb, Citation2020). Advances such as remote sensing and big data analyses have made important strides in data collection and generation, particularly expanding the availability of openly accessible data. Nonetheless, uncertainties associated with remotely sensed data remain a challenge requiring on-the-ground data collection for validation (García et al., Citation2016). Further, the costs and capacity needs of higher tech approaches can be substantial and may undermine their long-term sustainability, particularly in under-resourced environments (Sheffield et al., Citation2018). As such, data generation through on-the-ground observations, conducted in countries and exchanged across them, is likely to continue to play an important role for the foreseeable future, even with technological progress.Footnote3

Do treaties identify data exchange needs?

Obligations for data and information exchange feature prominently in international treaties (Gerlak et al., Citation2011). Reference to data exchange in basin-specific treaties often reflects provisions of global conventions, such as the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention and the 1992 Water Convention. The 1997 UN Watercourses Convention obligates parties to regularly exchange data that are ‘readily available’, ‘in particular that of a hydrological, meteorological, hydrogeological and ecological nature and related to the water quality as well as related forecasts’ (UN, Citation1997). Additionally, a watercourse state, when requested by another watercourse state, is obliged to employ their ‘best efforts’ to exchange data that are not ‘readily available’. ‘Best efforts’ in this context is defined as a state acting ‘in good faith and in a spirit of cooperation in endeavouring to provide the data or information sought by the requesting watercourse State’ (International Law Commission (ILC), Citation1994, p. 109). Similarly, the 1992 Water Convention calls for parties to ‘provide for the widest exchange of information, as early as possible, on issues covered by the provisions of this Convention’ (UNECE, Citation1992). These issues include environmental conditions, emissions and monitoring data, planned future measures as well as wastewater discharge regulations or permits. While neither convention text provides guidance on specific data to be exchanged,Footnote4 the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention outlines four data categories, and similarly the 1992 Water Convention calls for the ‘widest exchange of information’ and specifies five categories ().

Table 1. Data exchange attributes in transboundary waters conventions.

Protocols and basin plans

In addition to basin agreements, data exchange protocols, memoranda of understanding and/or basin plans are commonly used to operationalize data exchange in transboundary waters. Such protocols, etc, (e.g., Mekong River Commission, Citation2001; ZAMCOM, Citation2016) tend to outline more detailed data requirements than treaties. However, the extent to which they respond to basin-specific needs rather than follow a standard template is unclear. For example, the Zambezi Basin Rules and Procedures for the Sharing of Data and Information were established:

to ensure that relevant and quality assured data and information are shared in a timely fashion between the Member States in order to facilitate that the Member States – through ZAMCOM – will be able to take informed decisions in relation to the planning and management of the shared water resources in the Zambezi Watercourse (ZAMCOM, 2016, Article 3).

This objective does not indicate any specific needs for which data would be required. As for basin plans, which are developed with increasing frequency in transboundary basins to outline key issues and foster joint solutions based on an informed knowledge (data) base, Kazbekov et al. (Citation2016) did not find data and information exchange needs to be a key feature.

Whose needs?

Users of data and information (processed data) include water resource managers, infrastructure operators, as well as government regulatory authorities, ministries, water-user associations, private companies, individuals and academia among others (Bureau of Meteorology, Citation2017; Burton & Molden, Citation2005). A key issue is that users generally do not operate at an overall basin level but rather in particular countries in a basin (i.e., basin country units – BCUs), which need data from neighbouring countries to ensure satisfaction of water requirements within their portion of the basin. Within countries, data may be used to inform the operation of infrastructure such as dams, to decide on water allocations for irrigation and to assist government ministries – for example, of agriculture, water resources management, infrastructure development – to plan and manage. Data may also be used in conservation activities, fishing and recreation, and tourism. In this study, we assessed the data needs at the BCU level as perceived by water resources management officials.

Methodology

Rationale and framework

Conceptualizing a needs assessment: driving questions

The lack of past work on needs assessment for data exchange in transboundary waters, coupled with the postulated importance of need in explaining which data are exchanged, calls for development and application of an assessment framework for data exchange needs in transboundary basin. The assessment framework can draw on the past work reviewed above in the background section, but needs to be centrally oriented towards assessing data exchange needs – which has thus far not been undertaken. Three important questions drove this paper, and influenced the formulation of such a framework:

What data need to be shared between neighbouring riparians in transboundary watercourses to ensure water is available for key beneficial uses and to minimize water related risks?

To what extent do data exchange needs in specific BCUs align with data actually exchanged?

Where are data exchange needs met, and where do they fall short?

These sub-questions aim to shed more light on the paper’s central question: Do needs motivate the exchange of data in transboundary waters? By first establishing the data demands by riparians for specific uses and then comparing this demand with observed levels of data exchanged, we attempt to explain why data needs are met, or not, and whether such needs for data drive greater exchange among riparian countries.

Towards a framework

Based on these questions, a needs assessment framework was developed to guide the needs assessment survey (). The framework included three main components. The first component contextualized data exchange needs by reviewing contents of applicable transboundary water agreements and associated supporting instruments, such as data exchange protocols. The second component focused on data exchange parameters that are required to manage water for beneficial use. The third and final component focused on parameters of data exchange necessary to mitigate risk.

Table 2. Analytical framework for data exchange needs assessment.

Context

An assessment of legal obligations, as documented in treaty arrangements or subsequent commitments, for example, protocols adopted by countries, provided a necessary background to account for formally agreed data exchange parameters. In line with the 1992 Water Convention and the 1997 Watercourses Convention, this paper only includes those agreements that address the use and protection of international watercourses, and not those exclusively focused on boundary delimitation, navigation or fishing rights (Wolf, Citation1999).

Data exchange needs for beneficial use areas

Four beneficial water-use areas were identified as importantFootnote5 for transboundary data exchange:

Agriculture, which uses large volumes of water for irrigation in many shared river systems. Data exchange needs for assessing this use were measured through river flow data, water levels and abstraction data.

Hydropower generation which is dependent on upstream flows and impacts downstream flows. Hydropower infrastructure needs and impacts, considered through flow releases, water levels and abstraction.

Environmental and ecological requirements (environmental flows).

Urban water supply, considered through river flows, levels, abstraction and water quality.

In each of these areas the focus in particular basins was placed on two questions:

Are data needed from neighbouring countries in a basin?

If yes, what data are needed from neighbouring riparians for identified use areas?

Data exchange needs assessment for risk areas

Increase in flood incidence has necessitated the need for rapid response and preparedness (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Citation2021). Similarly, pollution from mine drainage, industrial accidents and agriculture return flows continues to add to the deterioration of water quality. As such, data exchange needs assessments for risks such as floods, droughts, and other human and natural disasters, are a potentially important area of transboundary data exchange to inform decision-making for early warning and disaster preparedness. Similarly, risk of pollution in transboundary bodies is best approached through exchange of specific data that allows for necessary precautions to be taken and harm mitigated. In this area, a focus was placed on two key questions:

Are data needed from neighbouring countries for managing water for minimizing risk and mitigating harm?

If yes, what data are needed to manage risk (or prevent/ mitigate harm)?

Data collection

Populating the framework with data from BCUs

While data exchange needs could be evaluated at a basin level, most transboundary basin bodies play a primarily coordinating role, removed from the day-to-day management of the basin (Kliot et al., Citation2001). As such, data are typically exchanged across a basin for use within countries. Given that users and indeed generators of exchanged data are at a country level, it made sense to collect data on need at a BCU level rather than from basin organizations. Assessment at the BCU level also allows for disaggregation of specific data needs in up- versus downstream countries.

Focus on African transboundary basins

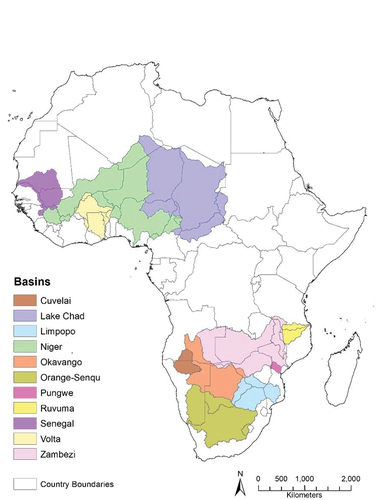

Given that the objectives of the paper include comparing data exchange needs with data exchange realities previously determined for 25 basins (Mukuyu et al., Citation2020), these 25 basins were used to delimit the potential geographical focus. Within this set of basins, those 11 basins located in Africa () were selected for two reasons: (1) similar contextual traits such as increasing population, water scarcity and variability in water availability (Mohamed, Citation2014); and (2) knowledge, networks and potential for synergies with other ongoing projects on the content, for example, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) BRIDGE – Building River Dialogue and Governance ProgrammeFootnote6 and an International Water Management Institute (IWMI)-led project – Conjunctive Surface-Groundwater Management of SADC’s Shared Waters: Generating Principles through Fit-for-Purpose PracticeFootnote7 – which greatly facilitated dissemination and follow-up on surveys to ensure response.

Figure 1. African basins of focus.

BCUs in African basins

Within the 11 selected basins, a focus was placed on BCUs with more than negligible portions of a transboundary basin in their country. As such, BCUs containing less than 5% of a transboundary basin were excluded from the analysis, in an effort: (1) to focus the assessment on BCUs with a substantial stake in transboundary cooperation and the data exchange to enable it;Footnote8 and (2) to render the questionnaire administration process manageable. This resulted in 37 BCUs of focus, located in 22 countries (). An exception was made for the Pungwe basin which is shared by only two countries, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, for which both countries were included.Footnote9

Table 3. Basin country units (BCUs) and corresponding area in the basin after filtering for at least 5% area in basin.

Survey design

The survey was formulated to enable populating the framework, while providing an intuitive presentation to respondents. Respondents simply ticked, or left unticked, boxes representing 18 different data parameters. Opportunity was also provided to specify other exchanged data, which may not have been included in the set of 18 parameters. If a parameter was needed, respondents further indicated the sectors for which data were needed. Six sectoral options were provided: agriculture, hydropower, environmental requirements, urban water supply, water quality and disaster risk management. To promote a high response rate after initial communication, respondents were contacted by telephone and prompted to complete the survey. Due to travel restrictions imposed by the COVID pandemic in 2020, remote communication proved an effective way of eliciting responses.

Populating the surveys

To the extent possible, we sought to assess country level needs through the lens of water resource managers entrusted with overall management of national and transboundary water resources. An experienced representative of each BCU thus completed the needs assessments survey. The representative typically participated in in-country basin management and represented the country on matters concerning the basin. While additional benefits may accrue from securing multiple perspectives on data exchange in each country, the practicalities of multiple engagements in each country would have likely proved onerous. As such, one focal person was nominated by a national representative active in a relevant transboundary river basin organization, to assess data exchange needs in each country. In cases for which multiple representatives became involved, such representatives were encouraged to channel their inputs through the overarching focal person. For instance, in the Orange–Senqu basin, where multiple responses were received from South Africa, a technical committee member of the Orange–Senqu basin technical committee was treated as the focal point. Ultimately, of the 37 BCUs for which questionnaires were sent, responses were received from 32. Responses were not received from: (1) Sudan in the Lake Chad basin, (2) Algeria in the Niger basin, (3) Botswana in the Orange–Senqu basin, (4) Mauritania in the Senegal basin, and (5) Burkina Faso in the Volta basin.

Data analyses

To enable assessment of data exchange needs, seven distinct analyses were carried out:

Reference to data exchange in treaties and protocols applying to the basins: Agreements and protocols were collected and examined. Guidance on data-sharing was then captured.

BCU perceptions of data exchange needs: Data exchange needs were aggregated across BCUs to generate a baseline picture of expressed data exchange needs.

How do data exchange needs vary across sectors? Given that data exchange needs likely vary across different sectors of water use, this analysis identified variation in needs across different sectors.

How do data exchange needs vary according to position in-basin (up-/downstream)? A BCU’s location in a basin was postulated to influence data exchange needs. Analytical assessment of location nonetheless requires classifying down- and upstream relationships, which can be complex (Delbourg & Strobl, Citation2012; Munia et al., Citation2016; Van Oel et al., Citation2009). For this paper, we used two methods to distinguish between BCU position:

In the first method we consider downstream countries according to a strict standard, that is, those where the mouth of the watercourse is located. All other countries are deemed upstream. Of the 32 BCUs analysed, 22 were classified as upstream and 10 as downstream.

In the second method we treat downstream countries according to a relaxed standard, that is, as any country with at least one upstream neighbour. As such, if a BCU is directly impacted by water use in a neighbouring country, then that BCU is deemed downstream. Of the 32 BCUs analysed, eight were classified as upstream and 24 as downstream:

Alignment between data exchange needs and data actually exchanged: To gauge the degree to which perceived data exchange needs are satisfied, BCUs that expressed data exchange need for particular data parameters were filtered and examined against actual level of basin-level data exchange on those same parameters. Data on actual levels of exchange were taken from Mukuyu et al. (Citation2020).

Where are needs satisfied? BCUs were stratified into four groups to clarify the degree to which data exchange needs were satisfied. A set of five core parameters were selected based on their persistence of demand across BCUs. These were used as benchmarks to assess need satisfaction: precipitation, river flow, reservoir storage, pH, electrical conductivity. The degree to which data exchange needs in these five core parameters were satisfied was classified into four categories (1) 0–24%, (2) 25–49%, (3) 50–74% and (4) 75–100%.

Does treaty coverage of data exchange align with expressed data exchange needs? Data exchange provisions in basin agreements were compared against levels of satisfaction. Quality of data exchange provisions in transboundary agreements were classified as either ‘general’ with no specific reference to data exchange or ‘specific’ with specific reference to data exchange. Agreements were also assessed for the breadth of coverage to different data parameters. These were then compared against expressed needs.

Results

This section presents the findings based on the framework elements (1) context, (2) data exchange for beneficial uses and (3) data exchange for risk mitigation to answer the driving questions:

What data needs to be shared?

To what extent needs for data exchange are met and why?

And ultimately to address the main research question.

Most treaties contain a focus on data exchange

Ten out of 11 basins possess legal frameworks that cover data exchange to at least some extent (). The 2000 Agreement on the Establishment of the Orange–Senqu River Commission and the 2004 Agreement on the establishment of the ZAMCOM specify the type of data to be exchanged: hydrological, water quality, meteorological and environmental condition for the Orange Senqu basin, and water levels, discharge, rainfall, evaporation, temperature, sediment concentration, water quality for the Zambezi basin. Other agreements, such as the 2016 Agreement between the Republic of Zimbabwe and the Republic of Mozambique on cooperation on the development, management and sustainable utilization of the water resources of the Pungwe Watercourse and the 2011 Water Charter for the Lake Chad basin provide specific guidance on data exchange as annexes to the main agreement which are similar in style to data exchange protocols. Such guidance includes aspects such as monitoring stations from which data would be generated, type of data and frequency of exchange.

Table 4. Coverage of data exchange in basin-wide treaties applying to basins of focus.a

Data exchange protocols exist in five of the 11 basins (). The 2010 Okavango River Basin Water Commission Protocol on Hydrological Data Sharing for the Okavango River Basin devotes focus to water levels, water discharge, water quality, sediment transport and meteorological data. Similarly, the 2016 Zambezi Basin Rules and Procedures for Sharing of Data and Information stipulate that water levels, discharge, rainfall, evaporation, temperature, sediment concentration and water quality data should be exchanged. Data exchange protocols often appear to complement treaties which provide only general coverage of data exchange. However, the 2003 Agreement between Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe on the Establishment of the Limpopo Watercourse Commission has a general data exchange clause but there is no supporting data exchange protocol.

The obligation to exchange data either fell on the secretariat, council or the state parties. In eight of the basins the obligation to exchange data is the responsibility of the contracting state parties while in the Limpopo basin the obligation is the responsibility of the council. It was unclear whose responsibility it is in the Senegal basin. Further, the strength of commitment to share data were either firm through the use of such wording as ‘shall exchange data’ (e.g., Cuvelai, Orange–Senqu) or less firm such as ‘cooperate in good faith’ (e.g., Zambezi). In the Okavango, the obligation to exchange data is tied to the national laws where parties can only exchange data ‘to the extent permitted by its own laws and procedures …’ ().

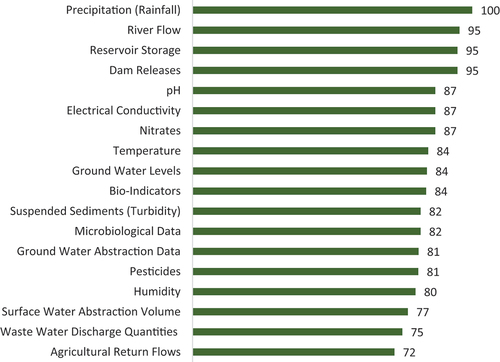

Data exchange needs are generally high across all basins

Expressed need across different parameters ranged from 70% to 100%. This would seem to underline realities of perceived high need for data exchange across the BCUs. There was nonetheless some variation, for instance, precipitation and river flow data registered the highest need at 100% and 95%, respectively, while the need for agricultural return flows was considerably lower (). In any case, demand for data was consistently high across the BCUs.

Urban water supply has greatest need for exchanged data

Urban water supply (68%), followed closely by agriculture (66%) and the environment (66%) use sectors, possessed greatest need for exchanged data (). The relatively low need for hydropower data (50%) may reflect the reality that hydropower did not exist in all BCUs.Footnote10 Demand for river flow data was consistently high in all six sectors, followed by precipitation data. Demand for exchanged data on groundwater level, surface water abstraction volume or biological indicator data was more variable.

Table 5. Data needs according to specific sector uses (%).

Downstream BCUs require more data exchange than upstream BCUs – mostly

Using the strict up-/downstream classification for which only countries at the river mouth were treated as downstream, variation of data exchange needs according to riparian position shows a consistent but expected trend of downstream data exchange needs exceeding upstream needs across the data parameters. Agriculture return flows and wastewater discharge quantities reflected the greatest discrepancy between upstream and downstream needs (). There were nonetheless similar levels of need for exchange for certain data parameters, regardless of riparian position. For example, all upstream and downstream BCUs expressed a need for exchange of precipitation data (100%).

Figure 3. (a) Data exchange-need variations according to a strict upstream–downstream classification; and (b) data exchange needs according to a relaxed upstream–downstream classification.

Applying a more relaxed classification of ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’(), in which a downstream riparian was treated as any country with at least one upstream riparian, resulted in a duller version of the same pattern. Perceived data needs in downstream BCUs were lower than in upstream BCUs in all but three parameters (bio-indicators, agriculture return flows, humidity) and similar across five parameters. Effectively, this result suggests that midstream countries – which possess both up- and downstream neighbours – do not harbour the same level of data exchange needs as strictly downstream riparians, located at river mouths with only upstream countries (i.e., as defined in the first classification).

Data exchange needs are often unsatisfied

When compared with previously reported levels of data exchanged (Mukuyu et al., Citation2020), there were no instances where data exchange needs were met completely (). Nonetheless, the need for exchange of river flow data can be interpreted as largely satisfied; likewise, exchange of data on precipitation is satisfied in more than half of basins. These positives are unfortunately contrasted by insufficiencies; meaning the need for data exceeds the extent of data currently exchanged. For data such as groundwater abstraction, suspended sediments, humidity and wastewater discharge quantities, exchange is completely absent despite considerable perceived need.

Table 6. Matching expressed need with assessed level of data exchange.

Stratifying BCUs based on satisfaction of data exchange needs reveals four groupings

To generate simple criteria for stratifying BCUs into groups based on the degree to which data exchange needs are met, a set of five core parameters were selected based on the ubiquity of expressed need for such data across sectors: river flow, reservoir storage, pH, electrical conductivity and precipitation. Based on degree to which expressed needs were met, BCUs were classified according to four classes of need satisfaction (1) 0–24% – needs unmet, (2) 25–49% – needs mostly unmet, (3) 50−74% – needs mostly met and (4) 75–100% – needs met.

Variation in satisfaction may depend on felt need

Assessing need satisfaction against the core set of parameters suggests, at least tenuously, that needs are mostly met at basin level – in the Lake Chad, Pungwe, Senegal, Niger and Zambezi basins but less so in the Cuvelai, Limpopo, Ruvuma and Okavango and Volta.Footnote11 Notably, the basins where perceived needs are mostly met appear to possess transboundary water infrastructure (Niger, Senegal, Zambezi), a pressing disaster risk reduction challenge such as desperately low lake levels (Lake Chad) or floods (Pungwe). Conversely, basins where perceived data exchange needs are less satisfactorily met, do not possess transboundary water infrastructure, and the likelihood of a collective action challenge was not entirely clear.

Do agreements associate with need for data exchange?

No clear pattern emerges between data exchange need satisfaction and coverage of data exchange in agreements or protocols (). However, where perceived needs are met in the Pungwe and Lake Chad basins, there is specific provision for data exchange including guidance on what data to exchange, and when. In the ‘needs mostly unmet’ category there is a mix of basins with a general data exchange clause (e.g., Limpopo) and no agreement in place (e.g., Ruvuma) as well as basins where specific provisions are given (e.g., Okavango). Similarly, needs are mostly met in the Niger basin where there is a clause but no specified data. Ultimately, it may be that a specific provision for data exchange is a necessary but insufficient condition for facilitating data exchange needs.Footnote12

Table 7. Role of agreements in supporting satisfaction of data exchange needs.

Discussion

While attention to data exchange in transboundary waters is increasingly focused on implementation challenges (Nishat & Shams, Citation2013; Plengsaeng et al., Citation2014; Thu & Wehn, Citation1992), assessment of factors explaining those challenges had not previously been systematically investigated. This paper designed a framework to assess the need for data exchange in transboundary waters and applied it in 11 shared river basins to gauge their need for shared water data. This paper thus constitutes a first effort to assess a factor – needs – that may explain the lower-than-targeted levels of data exchange. By establishing links between data exchange needs and data exchange realities, it is hoped that this paper can begin to focus discussion on addressing factors explaining chequered practical experiences in data exchange – which in turn is key to improving on the current baseline.

The paper generated at least four key findings in response to its driving questions. First, perceived data exchange needs are not fully satisfied by data exchange practice, and higher expressed needs for shared data do not explain lower levels of data exchange. Second, not surprisingly, data exchange requirements of downstream countries are greater than upstream countries in shared basins. Third, the sector most responsible for driving data exchange need, even if only marginally, is urban water supply. Fourth, stratification of basins into those with better versus worse levels of need satisfaction offers important clues on factors that drive data exchange. Ultimately, this suggests that addressing unmet data exchange needs may drive more data exchange in shared basins.

The paper’s first finding was that data exchange needs, as perceived by country representatives, were often unsatisfied and do not explain the low levels of exchange that are experienced. This finding was unexpected, as a hypothesis emerging from Mukuyu et al. (Citation2020) was that the low levels of exchange experienced in many transboundary watercourses, would be explained by low demand for exchanged data. In fact, data from neighbouring riparian countries are needed but not provided. There are a range of factors that may explain why needs are unsatisfied. Insufficient data digitization, for example, or concerns that data exchange may compromise national security, could both play some role.

The paper’s second finding – more demand for data exchange in downstream countries – was expected. Due to directionality of river flow, downstream countries have much to benefit from acquisition of data on upstream portions of shared water resources. Upstream countries, by contrast, may be mainly interested in downstream water resources insofar as there are developments that establish historic use precedents that preclude development in upstream parts of a shared basin. A policy implication of this finding, in any case, is that data exchange may not necessarily be required to flow in all directions in a basin. While fostering exchange from downstream to upstream countries is certainly positive, satisfying data exchange needs in a basin may call for central focus on ensuring data flows from upstream to downstream countries.

The paper’s third finding – most demand for exchanged data in urban water supply – may point to a deeper issue on the alternative manifestations of need. On the one hand, there is a general long-term need for exchange of water data for integrated planning and management, reflected in the high expressed demand for a range of parameters. On the other hand, there are data exchange needs in response to immediately felt concerns. Supplying adequate water and sanitation services to rapidly urbanizing population centres may fall in the latter category, despite the fact that water volumes used in urban supply are often much lower than sectors such as agriculture and the environment.

The paper’s fourth finding – differentiated need satisfaction across BCUs – may further underline the distinction between felt versus expressed need. In the case of BCUs that have their data exchange needs largely met, there is a direct felt need for exchanged data. Lake Chad faces declining lake levels that desperately require joint management. The Pungwe faces acute crises driven by severe floods, which can be partially mitigated through data exchange. The Niger, Zambezi and Senegal each possess transboundary infrastructure that are jointly planned or managed, and produce felt impacts. By contrast, in basins such as the Limpopo, Ruvuma and Zambezi, it may be that data exchange provides a broad basis for good water management, but may not be perceived to influence on-the-ground impacts to the same degree as the first group of basins.

Before concluding this section, it is important to acknowledge that data exchange is affected by third parties such as donors, as well as internal country dynamics. In some basins, for example, donors such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF) drive data exchange as part of a broader mandate related to institutional strengthening. Data exchange across countries is equally affected by the degree to which data are exchanged within countries. The limited exchange of data among related government departments, for example, can lead to data being locked in silos and not transmitted across countries.

Conclusions

Realization of data exchange that supports effective basin management and efficient progress towards national development aims may benefit from identification of basin-specific data-sharing needs. This paper assessed need for data exchange in 11 African basins and found that the high level of communicated need was generally unsatisfied by actual levels of exchange. Nonetheless, stratification of basins according to the degree of need satisfaction suggests that those with immediate uses of data, achieve higher levels of need satisfaction. Ultimately, while this paper’s findings cast some doubt on the role of expressed need for data exchange in driving on-the-ground data-sharing, the findings equally offer clues that real use drives real exchange. As such, needs do appear to motivate the exchange of data in transboundary waters, in particular when there is need to put data to use.

Contextualization of the paper’s findings in the chequered levels of global data exchange may call for exploration of needs-informed adjustments to data exchange targets. In particular, it may be prudent to consider more gradational approaches to targets, which could begin with, for example, a minimum aim of exchanging data in highest demand. The five core parameters identified above as cross-basin common denominators – river flow, reservoir storage, pH, electrical conductivity and precipitation – may provide a practically achievable starting point.

Related, consideration of findings in broader context reminds us that tools are needed to drive and promote data exchange. Given that felt needs appear to associate, at least tenuously, with more data exchange, one way to promote data exchange may be to concretize their benefits so they are palpable and felt. Indeed, discussion of the benefits of data exchange in shared waters may unfortunately too often default to generality despite existence of specific basin contexts which can motivate specific needs for, and modalities of, data exchange.

Three future directions may support deeper investigation into felt needs. First, data exchange needs, as expressed by survey respondents, may invariably be influenced by global directives which certainly constitute ideals to aspire to but may not always represent pressing needs in particular contexts. Measures to remove the influence of global best practice in respondent responses may help isolate the actual felt needs in specific basins. Second, monitoring changes in data exchange needs may provide general value by supporting revisions to data exchange modalities that foster alignment with evolving data exchange needs. There is also potential value in detecting some of the factors that explain evidenced changes in demand for data. Third, as this paper drew from evidence from Africa, basins in Asia and Latin America could receive focus in future efforts.

Before concluding this paper, we wish to acknowledge that this work is intended as a broad-based review rather than in-depth analysis of case studies. Individual cases studies were indeed not analysed to unearth deeper contextual issues. Nonetheless, the focus of this paper provides an opportunity for complementary future research focused on practical examples oriented towards discerning the potential of data needs assessments in improving data exchange in particular shared waters.

Ultimately, we offer five recommendations for enhancing data exchange in transboundary waters:

Identify and respond to real need for data exchange: A first recommendation centres on pinpointing – inferring if necessary – real felt needs for data, and supporting data exchange efforts that respond to those needs. Through prioritization and response to such needs, data exchange efforts can be more focused, targeted and ultimately effective.

Stimulate need as appropriate by encouraging the practical application of data: If data exchange is driven by real use of such data, it may be possible to promote use and application of data. University partnerships and institutionalized collaboration with research institutes, for example, may enhance use of data in activities such as modelling of alternative dam operations, water quality risk assessments or environmental impacts.

Promote a ‘first step’ set of data exchange parameters in resources-constrained basins: Given the widespread challenges of data exchange, it may be beneficial to start small initially and scale up progressively. Ideally, initial efforts should be focused on exchange of data parameters of greatest need. In the absence of information on data of greatest need in specific basins, data gauged to be of greatest importance through this study can serve as a minimum benchmark.

Implement periodic assessments of need to ensure data exchange aligns with evolutions in need: Needs are rarely static and needs for data exchange are no different. As such, periodic review of data exchange may help to ensure modalities remain up to date. Such data exchange needs assessments could form part of activities related to tasks such as basin plans and state of the basin reports.

Amplify the role of working groups and joint committees in identifying data needs: In this paper, a minimum set of five data exchange parameters were identified based on consistency of perceived need across the 11 basins surveyed. Transboundary working groups and joint technical committees can periodically undertake basin-specific assessment of data needs, on an ongoing basis, and provide clear direction on the practical application of shared data. Such actions may well augment basin agreements where data exchange provisions are lacking.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tamlyn Naidu for tirelessly engaging with basin countries, and Ranjith Alankara for map development. Special thanks to the basin country representatives who took part in the survey. This study was conducted under the Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE) Program of the CGIAR. and further financially supported by the United States State Department through the Shared Water Cooperation Facility (https://www.sharedwatersfacility.org/) as well as the CGIAR program - Nexus Gains. The authors also acknowledge the Building River Dialogue and Governance (BRIDGE) Programme implemented by the IUCN and funded by the Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC), for making available practical examples of data exchange in shared basins.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The work of Mukuyu et al. and some associated work was promoted through an IWMI policy brief. For more information, see https://www.iwmi.cgiar.org/publications/briefs/water-policy-briefs/data-sharing-in-transboundary-waters/.

2. The paper focuses on water-related data as opposed to information (processed data).

3. On-the-ground observation requires human and financial capital (e.g., skilled technicians and infrastructure for observation networks). As a result, many low-income countries are failing to maintain data collection networks (e.g., hydrometric networks).

4. Supporting guidelines to the Water Convention have been developed to guide its implementation, for example, the Strategies for Monitoring and Assessment of Transboundary Rivers, Lakes and Groundwaters where further guidance is given on data and information exchange (UNECE, Citation2023).

5. We acknowledge that these use areas are not exhaustive but represent the largest uses.

8. The authors equally recognize that geopolitical factors that may also influence the stake a country has in a basin – regardless of size. Nonetheless, determination of a threshold for inclusion or exclusion in light of such factors was not straightforward.

9. While there is only a 4% portion of the Pungwe basin in Zimbabwe, the country was included as it is one of only two countries that share the basin.

10. Five of basins do not possess hydropower.

11. Orange–Senqu satisfaction levels were inconclusive.

12. It is important to note the role of working group and joint committees in data exchange which are not discussed in this paper.

References

- Bradshaw, J. R. (1972). The taxonomy of social need, and G. McLachlan (Ed.), Problems and progress in medical care: Essays on current research, 7th series (pp. 71–82). Oxford University Press.

- Bureau of Meteorology. (2017). Good practice guidelines for water data management policy: World water data initiative.

- Burton, M., Molden, D. (2005). Making sound decisions: Information needs for basin water management, and M. Svendsen (Ed.), Irrigation and river basin management: Options for governance and institutions (pp. 51–74). CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851996721.0051

- Cantor, A., Kiparsky, M., Kennedy, R., Hubbard, S., Bales, R., Pecharroman, L. C., Guivetchi, K., McCready, C., & Darling, G. (2018). Data for water decision making: Informing the implementation of California’s open and transparent water data act through research and engagement. Center for Law, Energy & the Environment, UC Berkeley School of Law, Berkeley, CA, 56. https://doi.org/10.15779/J28H01

- Chenoweth, J. L., & Feitelson, E. (2001). Analysis of factors influencing data and information exchange in international river basins: Can such exchanges be used to build confidence in cooperative management? Water International, 26(4), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060108686951

- Delbourg, E., & Strobl, E. (2012). Cooperation and conflict between upstream and downstream countries in African transboundary rivers. Ecole Polytechnique.

- Dellapenna, J. W. (2001). The customary international law of transboundary fresh waters. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 1(3–4), 264–305. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGENVI.2001.000981

- Del Moral, L., Pita, M. F., Pedregal, B., Hernández-Mora, N., & Limones, N. (2014). Current paradigms in the management of water: Resulting information needs. In A. Roose (Ed.), Progress in water geography – Pan-European discourses, methods and practices of spatial water research (pp. 21–31). Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu.

- Gagne, R. M., Briggs, L. J., & Wager, W. W. (1992). Principles of instructional design (4th ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Gao, J., Castelletti, A., Burlado, P., Wang, H., & Zhao, J. (2022). Soft-cooperation via data sharing eases transboundary conflicts in the Lancang–Mekong river basin. Journal of Hydrology, 606, 127464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127464

- García, L., Rodríguez, D., Wijnen, M., & Pakulski, I. Eds. (2016). Earth observation for water resources management: Current use and future opportunities for the water sector. World Bank Publications. World Bank Group. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0475-5

- Gerlak, A. K., Lautze, J., & Giordano, M. (2011). Water resources data and information exchange in transboundary water treaties. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 11(2), 179–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9144-4

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

- International Law Commission (ILC). (1994). Draft articles on the Law of the non-navigational uses of international watercourses and commentaries thereto and resolution on transboundary confined groundwater. https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/commentaries/8_3_1994.pdf

- International Sava River Basin Commission (ISRBC). 2014: Policy on the exchange of hydrological and meteorological data and information in the Sava river basin. World Meteorological Organization and European Commission. http://www.savacommission.org/dms/docs/dokumenti/documents_publications/basic_documents/data_policy/dataexchangepolicy_en.pdf

- Jeffrey, P., & Gearey, M. (2006). Integrated water resources management: Lost on the road from ambition to realisation? Water Science and Technology, 53(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2006.001

- Kaufman, R., Rojas, A., & Mayer, H. (1993). Needs assessment: A user’s guide. Educational Technology Publishers.

- Kazbekov, J., Tagutanazvo, E., & Lautze, J. (2016). A global assessment of basin plans: Definitions, lessons, recommendations. Water Policy, 18(2), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2015.028

- Kliot, N., Shmueli, D., & Shamir, U. (2001). Institutions for management of transboundary water resources: Their nature, characteristics and shortcomings. Water Policy, 3(3), 229–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1366-7017(01)00008-3

- Leb, C. (2015). One step at a time: International law and the duty to cooperate in the management of shared water resources. Water International, 40(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2014.978972

- Leb, C. (2020). Data innovations for transboundary freshwater resources management: Are obligations related to information exchange still needed? Brill Research Perspectives in International Water Law, 4(4), 3–78. https://doi.org/10.1163/23529369-12340016

- McDonnell, R. A. (2008). Challenges for integrated water resources management: How do we provide the knowledge to support truly integrated thinking? International Journal of Water Resources Development, 24(1), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900620701723240

- Mekong River Commission. (2001). Procedures for data and information exchange and sharing. http://www.mrcmekong.org/assets/Publications/policies/Procedures-Data-Info-Exchange-n-Sharing.pdf

- Merriam Webster Online Dictionary. (2020). Merriam webster online dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/need

- Milman, A., Gerlak, A. K., Albrecht, T., Colosimo, M., Conca, K., Kittikhoun, A., Kovács, P., Moy, R., Schmeier, S., Wentling, K., Werick, W., Zavadsky, I., & Ziegler, J. (2020). Addressing knowledge gaps for transboundary environmental governance. Global Environmental Change, 64, 102162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102162

- Mirghani, M. (2012). Groundwater need assessment Nubian sandstone basin. WATERTRAC, Nile IWARM, 29.

- Mohamed, A. E. (2014). Comparing Africa’s shared river basins – The Limpopo, Orange, Juba and Shabelle basins. Universal Journal of Geoscience, 2(7), 200–211. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujg.2014.020703

- Mukuyu, P., Lautze, J., Rieu-Clarke, A., Saruchera, D., & McCartney, M. (2020). The devil’s in the details: Data exchange in transboundary waters. Water International, 45(7–8), 884–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2020.1850026

- Munia, H., Guillaume, J. H. A., Mirumachi, N., Porkka, M., Wada, Y., & Kummu, M. (2016). Water stress in global transboundary river basins: Significance of upstream water use on downstream stress. Environmental Research Letters, 11(1), 014002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/1/014002

- Nishat, B., & Shams, S. (2013). Towards improved data and information exchange in the Ganges basin. Issue brief. The Asia Foundation pp.1–8. https://www.india-seminar.com/2013/652/652_bushra_&_shamim_shams.htm

- Plengsaeng, B., Wehn, U., & van der Zaag, P. (2014). Data-sharing bottlenecks in transboundary integrated water resources management: A case study of the Mekong river commission’s procedures for data sharing in the Thai context. Water International, 39(7), 933–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2015.981783

- Reviere, R., Berkowitz, S., Carter, C. C., & Ferguson, C. (Eds.). (1996). Needs assessment: A creative and practical guide for social scientists. Taylor & Francis.

- Rosen, R. A., Hermitte, S. M., Pierce, S., Richards, S., & Roberts, S. V. (2019). An internet for water: Connecting Texas water data. Texas Water Journal, 10(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.21423/twj.v10i1.7086

- Royse, D., Staton-Tindall, M., Badger, K., & Webster, J. M. (2009). Needs assessment (Vol. 8). OUP USA.

- Scherer, R., Redding, T., Ronneseth, K., & Wilford, D. (2017). Research and information needs assessment to support sustainable watershed management in the South Coast and West Coast Natural Resource Regions, British Columbia. Prov. BC, Victoria. BC Tech. Rep. 110. www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/pubs/Docs/Tr/Tr110.htm.

- Sheffield, J., Wood, E. F., Pan, M., Beck, H., Coccia, G., Serrat-Capdevila, A., & Verbist, K. (2018). Satellite remote sensing for water resources management: Potential for supporting sustainable development in data-poor regions. Water Resources Research, 54(12), 9724–9758. https://doi.org/10.1029/2017wr022437

- Soriano, F. I., 2012. Conducting needs assessments: A multidisciplinary approach (Vol. 68). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335780

- Stufflebeam, D. L., McCormick, C. H., Brinkerhoff, R. O., & Nelson, C. O., 2012. Conducting educational needs assessments (Vol. 10). Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-7807-5

- TFDD. (2017). Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at: http://transboundarywaters.science.oregonstate.edu

- Thu, H. N., & Wehn, U. (2016). Data sharing in international transboundary contexts: The Vietnamese perspective on data sharing in the Lower Mekong Basin. Journal of Hydrology, 536, 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.02.035

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). (1992). Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes. Adopted in 1992 and effected in 1996.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). (2023). Updated strategies on monitoring and assessment of transboundary rivers, lakes and groundwaters. ECE/MP.WAT/70. https://unece.org/environment-policy/publications/updated-strategies-monitoring-and-assessment-transboundary-rivers

- United States Department of the Interior (USDOI). (2012). Water needs assessment technical report Northwest Area Water Supply (NAWS) project. North Dakota Dakotas Area Office, Great Plains Region.

- UN (United Nations). (1997). The Convention on the Law of non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses. Adopted 21 May 1997.

- UN Water. (2020). The sustainable development goal 6 global acceleration framework. United Nation Water. https://www.unwater.org/publications/the-sdg-6-global-acceleration-framework

- Vaessen, V., & Brentführer, R. (2014 ()). Integration of groundwater management: Into transboundary basin organizations in Africa. Training manual. https://www.gwp.org/globalassets/global/toolbox/references/trainingsmanual.pdf

- van Oel, P. R., Krol, M. S., & Hoekstra, A. Y. (2009). A river basin as a common-pool resource: A case study for the Jaguaribe basin in the semi-arid Northeast of Brazil. International Journal of River Basin Management, 7(4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2009.9635393

- Vera, C., Barange, M., Dube, O. P., Goddard, L., Griggs, D., Kobysheva, N., Odada, E., Parey, S., Polovina, J., Poveda, G., & Seguin, B. (2010). Needs assessment for climate information on decadal timescales and longer. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 1, 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2010.09.017

- Witkin, B. R., & Altschuld, J. W. (1995). Planning and conducting needs assessments: A practical guide. Sage Publications.

- Wolf, A. T. (1999). The transboundary freshwater dispute database project. Water International, 24(2), 160–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508069908692153

- Wright, J., Williams, R., & Wilkinson, J. R. (1998). Development and importance of health needs assessment. Bmj, 316(7140), 1310–1313. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7140.1310

- Zambezi Watercourse Commission (ZAMCOM (). (2016). Rules and procedures for sharing data and information related to the management and development of the Zambezi watercourse. http://www.zambezicommission.org/sites/default/files/clusters_pdfs/16.07.28-Rules_ProceduresForDataSharing_Adopted-by-Council_FinalEditing_Ver10_FINAL.pdf