?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study examines the environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting in 38 public water companies owned by local municipalities from Andalusia. With an adapted measure integrated by 172 indicators drawn from national and international standards, results show a low level and quality of ESG disclosure. Along with the positive relationship with size and cultural orientation towards transparency, the hybrid nature of public companies is directly related to their ESG disclosure activity. Unlike what could happen in other sectors, the presence of private capital in the shareholding provides water companies with experienced knowledge to better report financial and non-financial information.

Introduction

The challenge facing the world in this century is to achieve a development that balances social, economic and environmental concerns (Cabello et al., Citation2021). The impact of human activity on our planet has led to a rapid transition from the Holocene to the Anthropocene, where demand for natural resources, energy and water has increased dramatically (Bebbington et al., Citation2020). Companies, aware that they are not exempt from this challenge and that controversial economic, social and environmental scandals in recent decades have led to a loss of trust and credibility, have increased their efforts to align their strategy with the achievement of sustainable principles (Garde et al., Citation2017). In this regard, annual reporting on social and environmental issues has become a widespread institutional practice through which companies can strengthen their corporate image and reputation (Farooq & de Villiers, Citation2019). In fact, The KPMG Survey of Sustainability Reporting found that 96% of the world’s 250 largest companies reported on sustainability or environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters in 2022 (KPMG, Citation2022). Several studies have highlighted that environmentally sensitive companies, as well as larger companies or those providing public services, have greater incentives to disclose social and environmental information due to their higher visibility and exposure to public scrutiny (Reverte, Citation2015). In addition, as Royo et al. (Citation2019) suggest, transparency and disclosure are key elements to facilitate the monitoring of whether companies offering public services are managing well and achieving both their public and business targets efficiently.

From the early 1990s to now, different international pronouncements (e.g., the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development in 1992) and declarations have been launched to emphasize a sustainable use of water resources in the pursuit of a balance between progress and sustainability (Larrinaga & Perez, Citation2008; Passetti & Rinaldi, Citation2020). Although the access to water became a fundamental right for everyone in 2010 by a United Nations General Assembly 64/292 resolution, the attention on water in the global political agenda has been renewed with the emergence of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the SDG 6’s mission statement: ‘Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all’ (Timmerman et al., Citation2022). The recent concern for how rapid climate change affects water scarcity reinforces this societal problem’s relevance for present and future generations (McDonald-Kerr, Citation2017; Tan & Egan, Citation2018).

Companies responsible for the management and distribution of water should be leading actors in advancing a sustainability agenda (Ferdous et al., Citation2019; Larrinaga & Perez, Citation2008). Water enterprises have a purpose that is inextricably linked to the satisfaction of a social need, such as the management of a fundamental resource for the sustainable development of the planet (Perez et al., Citation2016). This means that these enterprises (i.e., Veolia, Suez NWS, ITT Corp., United Utilities, Severn Trent, Thames Water or Aqualia) are highly exposed to public scrutiny, as they operate in an industry with high environmental risk (Andrades & Larran, Citation2019). To meet stakeholder pressures and maintain legitimacy, these companies are compelled to adopt ESG disclosures (Adams & McNicholas, Citation2007; Vinnari & Laine, Citation2013). Their social character also means that they have a moral obligation to society that could reinforce the idea of why they should have higher levels of ESG disclosure compared to companies from other industries (Andrades & Larran, Citation2019).

Public water companies owned and controlled by municipalities are unique and complex organizations that deserve special attention among all water companies (Bruton et al., Citation2015; Grossi et al., Citation2017). Public water utilities differ from private water companies because they are ‘situated at the boundary between the public and private sector’ (Nicolò et al., Citation2021, p. 139). Although public water utilities are structured and managed like private companies, they provide a public service to society (Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021; Rodríguez Bolívar et al., Citation2015). Based on previous research, it is suggested that they are hybrid organizations in which control and ownership are shared between public and private shareholders (Bruton et al., Citation2015). Their hybrid nature implies that they have to reconcile two diverging logics (Royo et al., Citation2019; Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021): (i) the provision of a public service to society (the social logic), and (ii) the pursuit of a financial reward (the market logic). This hybridity supposes that public water utilities can be very different from each other, mainly based on their proportion of public ownership (Nicolò et al., Citation2021). Different degrees of public ownership might impact their organizational structure, governance, funding, and control (Grossi et al., Citation2017).

The previous arguments suggest that public water utilities could be an interesting setting to examine ESG disclosure activity due to their unique organizational structure, agency environment, organizational objectives, and relationship with society (Grossi et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). In fact, it is particularly interesting to understand how the hybrid nature of public water utilities may affect their level of ESG disclosure (Argento et al., Citation2019). In line with the concept of hybridity, public water utilities with a mixed ownership of public and private shares could be pressured to balance and reconcile the market with social and environmental logics through the provision of reliable and comprehensible ESG information (Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021).

We seek to contribute to the ESG reporting research from the hybrid perspective of water utilities. Consistent with this theoretical approach, we can better understand whether hybridity affects the disclosure of ESG information by public water utilities. Most previous research has found different motivations for providing ESG information, ranging from legitimacy theory to stakeholder and institutional theories (Farneti et al., Citation2019; Li & Belal, Citation2018; Tirado-Valencia et al., Citation2019). However, little attention has been paid to understanding the role of hybridity in ESG disclosure patterns of public utilities (Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Drawing on the theory of institutional logics as well as legitimacy and stakeholder theories, public water utilities could use ESG disclosure to satisfy the demands of their private and public owners, who have different and conflicting needs, and could also provide them with legitimacy (Garde et al., Citation2017; Nicolò et al., Citation2021).

The Spanish setting is an interesting case to study for several reasons. (1) Spain is one of the Western countries with the longest tradition of ESG reporting practices (Reverte, Citation2015). (2) The Spanish government has approved various regulations requiring the disclosure of ESG information by private and public organizations (Luque & Larrinaga, Citation2016). It could be interesting to understand the role of regulatory forces in the commitment of public water companies to ESG disclosure (Larrinaga et al., Citation2018). (3) Many areas of Spain, like the Andalusian region, have experienced significant water scarcity in recent decades (McDonald-Kerr, Citation2017). Andalusia relies heavily on efficient public water management to meet agricultural, industrial, and domestic demands. Sustainable water management practices are crucial to ensure the productivity and stability of the agricultural sector (Bermejo-Martín & Rodríguez-Monroy, Citation2019; Cabello et al., Citation2021). Industries, including tourism, are major contributors to the region’s economy, emphasizing the need for a well-managed water supply to sustain these activities. Furthermore, the unique environmental characteristics of Andalusia, such as its diverse ecosystems and rich biodiversity, require careful consideration in water management (Cabello et al., Citation2021). Striking a balance between human needs and environmental preservation is a challenging yet essential aspect of public water governance (Bermejo-Martín & Rodríguez-Monroy, Citation2019). Collaborative and forward-thinking public policies are essential to address the challenges posed by water scarcity and to secure a resilient future for the region. For all these reasons public water utilities could be pressured to account for their social and environmental impacts (Larrinaga & Perez, Citation2008).

Therefore, this paper investigates the determinants of the ESG disclosure activities in public water companies owned by local municipalities from Andalusia (Spain). To this end, the researchers have conducted a content analysis of multiple reporting channels of the 38 Andalusian public water utilities sampled. To measure the level of ESG disclosure, the authors designed their own instrument tool integrated by 172 indicators derived from previous standards developed by national and international professional bodies or standard setters.

ESG disclosure activity in public water utilities

Regulatory framework

The Spanish government passed Law 2/2011 on Sustainable Economy, in line with the EU sustainable development strategy. This law mandates certain organizations to adopt ESG reporting practices (Larrinaga et al., Citation2018; Luque & Larrinaga, Citation2016). Article 35 of the same law requires that, within one year from its approval, state-owned enterprises and public business entities prepare annual sustainability reports following internationally accepted guidelines. More specifically, article 39 of this regulation argues that limited companies with more than 1000 employees should prepare annual sustainability reports and submit them to the State Council for Corporate Social Responsibility. These requirements are also contemplated in the Spanish Strategy for Corporate Social Responsibility (2014–2020). Despite this, public water utilities owned by local municipalities are not required by this law to produce annual sustainability reports.

More recently, the Spanish government transposed the European Directive 2014/95 on non-financial information into its national regulatory framework (Montesinos & Brusca, Citation2019). The Spanish Law 11/2018 on non-financial reporting introduced, from the 2018 fiscal year, mandatory ESG disclosure requirements for large companies and/or public interest entities through the preparation of a non-financial information statement (Garcia-Benau et al., Citation2022). From the 2021 fiscal year, this requirement has been extended to those companies with more than 250 employees that are considered public interest entities or that meet a series of turnover or asset volume requirements. This regulation requires companies to disclose some information about their social and environmental concerns according to one or more accepted sustainability reporting standards (Giner & Luque-Vilchez, Citation2022). However, with the exception of one company, Andalusian public water utilities are not required to comply with these mandatory ESG disclosure requirements.

On the other hand, the Spanish government approved Law 19/2013 on Transparency and Good Governance in response to society’s loss of confidence in public activity, caused by the increasing number of corruption cases (Andrades et al., Citation2022). This law mandated the online disclosure of corporate governance information for all enterprises in which the state, regional, or local governments own more than 50% (Andrades & Larran, Citation2019).

The description of the Spanish ESG reporting landscape reveals that the regulatory framework for public water utilities is insufficient. Apart from the Spanish Law 19/2013 on Transparency and Good Governance, which mandates certain requirements for ESG disclosure, the other two laws do not compel public water utilities to undertake ESG reporting practices.

Theoretical framework

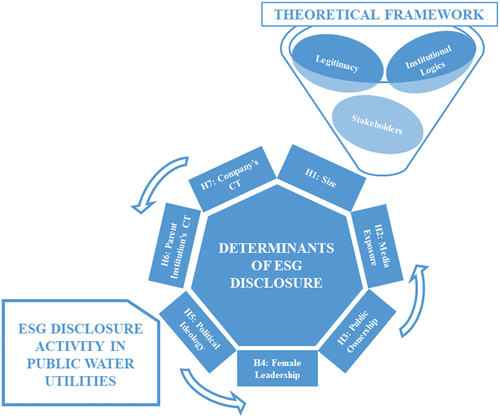

As can be observed in , this study proposes the joint use of the theory of institutional logics and stakeholder and legitimacy theoretical approaches to explain how different determinants, including hybridity factors, can affect the level of ESG disclosure in public water utilities. Consistent with Gendron (Citation2018), the combination of different theoretical concepts could be understood as a ‘theoretical bricolage’ to develop a framework that fits with our analytical purposes. The joint use of these theories could be a theoretical contribution of this paper.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework and determinants of ESG disclosure activity in public water utilities.

Legitimacy theory suggests the existence of an implicit ‘social contract’, organizations try to align their values with those of a broader social system in which they operate and the information disclosed seeks to convince society at large that interests and expectations of social development are being addressed (Garde et al., Citation2017; Ntim et al., Citation2017). According to Royo et al. (Citation2019), legitimacy theory determines a societal-led motivation for voluntary disclosure and public entities need their activities and objectives to be supported by society, especially those with higher visibility and influence. Whereas this theoretical approach is oriented to society at large, stakeholder theory (Freeman, Citation1984) considers the existence of a variety of interest groups (shareholders, employees, investors, public authorities, suppliers, customers, local communities, non-governmental organizations, the media or the general public) with different needs, expectations and capabilities for influencing organizational activity. Under this approach, ESG disclosure could be used as a strategic management tool to meet the requirements of the most important stakeholders, to gain their support and to guarantee the survival of the company (Garde et al., Citation2017; Ntim et al., Citation2017). Previous scholars have called for more research on how hybridity can affect ESG disclosure using the institutional logics approach (Argento et al., Citation2019; Grossi et al., Citation2017). According to Grossi et al. (Citation2015, p. 275), a public water utility, being a hybrid organization, ‘operates in a business-like manner to provide public services with public funding and is politically governed’. Consequently, they can differ between themselves depending on the following hybrid factors: proportion of public ownership, governance and control, the type of government (local, regional or national) that owns the company, or the dissimilar purpose that they pursue (Nicolò et al., Citation2021). Following the notion of hybridity, public water utilities have a complex organizational structure derived from their mixed ownership, and it supposes that they have a broad range of public and private stakeholders (Bruton et al., Citation2015). As a result, these organizations could experience amplified demands for ESG disclosure to gain legitimacy from various stakeholders (Argento et al., Citation2019; Tirado-Valencia et al., Citation2019).

Based on the theory of institutional logics, hybrid organizations, such as public water utilities, need to combine and reconcile two competing logics that are at the heart of their identity (Andrades & Larran, Citation2019; Argento et al., Citation2019). On the one hand, their public nature involves that public water utilities have to provide a service to society (social logic). On the other hand, as they operate in a business-like manner, they also have to pursue financial regard (market logic). Following this logic, we expect hybridity, measured as the proportion of public ownership, to explain different ESG disclosure patterns among public water utilities (Grossi et al., Citation2022; Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Based on theoretical insights drawn from institutional logics, stakeholder and legitimacy theories, the mixed ownership between public and private owners makes public water utilities disclose ESG information to balance the market with social logics due to the need to legitimize their behaviour towards their broad number of stakeholders (Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021; Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021).

In addition, other factors associated with visibility, like organizational size, media exposure and political ideology, could explain why some public water utilities could have better levels of ESG disclosure (Argento et al., Citation2019; Garde et al., Citation2017). Consistent with our theoretical framework, these companies may be more focused on reconciling social and market logics because they are highly sensitive to public opinion (Royo et al., Citation2019). Thus, they could provide more ESG information to legitimize their behaviour in society through the disclosure of ESG information (Garde et al., Citation2017). Finally, some factors connected with moral aspects, like female leadership or transparency culture, might determine whether some public water utilities are more engaged in ESG disclosure than others (Argento et al., Citation2019). Drawing on our theoretical framework, moral values are linked to an inherent sense of social responsibility, which might explain why some public water utilities feel morally obliged to balance their market and social logics through the provision of ESG information. In this regard, ESG reporting guarantees them legitimacy in the eyes of a broader number of stakeholders (Larrinaga & Perez, Citation2008).

ESG disclosure activity in public water utilities

Over the last three decades, the demand for social and environmental reporting in the corporate sector has intensified in response to societal pressures (Higgins et al., Citation2018). Since then, the practice of ESG reporting has become widely institutionalized in the corporate sector (Higgins et al., Citation2018; Milne & Gray, Citation2013). For more than 25 years, accounting researchers have explored the patterns, determinants and motivations associated with the disclosure of ESG information by private companies (Bebbington et al., Citation2009; Contrafatto, Citation2014). Recently, some authors have tried to explain whether ESG reporting is being integrated into the management decision of these companies (Farooq & de Villiers, Citation2019; Tarquinio & Xhindole, Citation2022).

Meanwhile, the topic of ESG reporting has been less investigated in the public water utility sector compared to the vast body of work on this research theme in the private sector (Tirado-Valencia et al., Citation2019; Vinnari & Laine, Citation2013). Previous literature on the public water utility setting has been approached from four main streams of research. (1) Some accounting researchers have explored the underlying drivers associated with the disclosure of ESG information, pointing out legitimizing motivations (Vinnari & Laine, Citation2013), with a public accountability purpose for internal and external stakeholders (Tan & Egan, Citation2018), as well as mandatory requirements compliance (Ferdous et al., Citation2019). (2) Other studies explored whether the external ESG information disclosed by public water utilities is informative or not (McDonald-Kerr, Citation2017; Perez et al., Citation2016). (3) A third group of researchers devoted their attention to explaining how different aspects can impact the processes and dynamics of the practice of ESG reporting in public water utilities over time (Adams & McNicholas, Citation2007; Larrinaga & Perez, Citation2008; Tregidga & Milne, Citation2006).

To the best of our knowledge, there has been limited empirical research into the determinants behind disclosing ESG information in public water utilities, particularly concerning the hybrid character of some of these organizations (Argento et al., Citation2019; Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Grossi et al. (Citation2022, p. 591) state that ‘more research is needed on how different drivers connected to hybridity affect their sustainability and SDGs’ disclosures’. Accordingly, the hybrid nature of public water utilities might explain different ESG disclosure patterns among these organizations depending on the proportion of public ownership (Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Furthermore, corporate characteristics and contextual factors may elucidate why some public water utilities disclose more ESG information than others (Andrades & Larran, Citation2019).

Based on our theoretical framework drawn from various sources, we try to examine whether the level and quality of ESG disclosure in Andalusian public water utilities is affected by different attributes, such as organizational size, media exposure, proportion of public ownership, female leadership, political ideology, and commitment to transparency.

Organizational size

Consistent with previous literature, large companies tend to disclose more ESG information because they ‘are more visible to the public, are more newsworthy, have a bigger effect on the community, and therefore typically have a broader group of stakeholders that influence the organisation and its priorities’ (Reverte, Citation2009, p. 354). Drawing on the theory of institutional logics along with legitimacy and stakeholder theories, large public water utilities are more exposed to public scrutiny, and they have higher stakeholder pressures to balance their social and market logics (Argento et al., Citation2019; Nicolò et al., Citation2021). Thus, the disclosure of ESG information would be a powerful instrument to satisfy the informational demands of their broad range of private and public stakeholders to be legitimate in society (Andrades & Larran, Citation2019; Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021). In addition, large public water utilities have more resources, and would have professionals with higher levels of skills within their senior management team. This could also explain why these organizations have better levels of ESG disclosure (Haraldsson & Tagesson, Citation2014). In view of these theoretical assumptions, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1: Larger Andalusian public water utilities are more likely to disclose ESG information than smaller ones.

Media exposure

Different authors have argued that the media could have a remarkable impact on top management decisions, suggesting that the level of exposure to the media could have an effect on ESG disclosure (Michelon, Citation2011; Reverte, Citation2009). Previous studies have documented a positive association between media exposure on the Internet and the visibility of any enterprise, which leads to these enterprises being publicly scrutinized (Bansal, Citation2005). In the context of this paper, public water utilities are companies that operate in a highly sensitive sector from a double point of view: first, their activity has a remarkable environmental impact (Larrinaga & Perez, Citation2008), and second, they are responsible for managing a basic resource for sustainable development (Vinnari & Laine, Citation2013). In accordance with our theoretical framework, those public water utilities more exposed to the media have greater incentives to reveal ESG information to reconcile their market and social logics (Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021. It could help them meet the informational demands of their multiple stakeholders and confer legitimacy upon them (Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021; Royo et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the following hypothesis is also considered:

H2: Andalusian public water utilities more exposed to the media are more likely to disclose ESG information.

Public ownership

Several authors have broadly argued about the pros and cons of private-sector participation in water and wastewater management (Lloyd Owen, Citation2022). According to Garde et al. (Citation2017), companies with a higher proportion of public ownership would have better levels of ESG disclosure because the government plays a fundamental role in representing the interests of society and contributing to social welfare. Accordingly, these enterprises have to manage the needs and demands of a wide range of stakeholders (Argento et al., Citation2019; Nicolò et al., Citation2021), with the government being the most powerful as it is the main owner of these companies (Royo et al., Citation2019). Drawing on stakeholder theory, companies with a higher proportion of public ownership might disclose ESG information because the government can exert its power to coerce them into fulfilling their demands (Farneti et al., Citation2019; Ferdous et al., Citation2019). From a legitimacy approach, the greater public ownership over the company means that they are subject to greater scrutiny by society, which would translate into an increase in the ESG information disclosed to legitimize themselves (Garde et al., Citation2017).

On the other hand, other scholars have argued that the higher proportion of private ownership in publicly owned companies could have a positive effect on the productivity (Molinos-Senante et al., Citation2022) and on the level of their ESG disclosures (Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Drawing on an institutional logics approach coupled with legitimacy and stakeholder theories, the presence of private investors as public water utilities owners’ may put pressure on these companies to reveal ESG information as a way to balance market and social logics in order to legitimize its behaviour with respect to all its stakeholders (Ferdous et al., Citation2019; Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: The degree of public or private ownership can affect the level of ESG disclosure in Andalusian public water utilities.

Female leadership

Previous literature has examined the impact of having women on company boards on the commitment to ESG reporting (Argento et al., Citation2019; Garde et al., Citation2017). Based on moral reasoning theory, female managers are more sensitive in scenarios requiring an ethical judgement because they tend to be more empathetic, compassionate, and cooperative than their male colleagues (Rao & Tilt, Citation2016). Drawing on our theoretical framework, public water utilities headed by a female board chair would have better levels of ESG disclosure. This is because their moral beliefs can facilitate the integration of social and market logics within the company (Adams & McNicholas, Citation2007). From a normative perspective of legitimacy and stakeholder theories, it would mean that women might feel that they have a moral obligation to society, and companies headed by them would adopt ESG disclosures to satisfy the informational demands of their stakeholders to be perceived as legitimate (Passetti & Rinaldi, Citation2020). Thus, the following hypothesis is raised:

H4: Andalusian public water utilities headed by a female board chair are more likely to disclose ESG information compared to others.

Political ideology

Previous studies on local governments have commonly employed political ideology as a potential variable for explaining the commitment to information disclosure (Garcia-Sanchez et al., Citation2013). However, most of this prior empirical literature has examined whether the level of disclosure by local governments differs based on their progressive or conservative ideology (Saez-Martin et al., Citation2017). Mostly, the literature has evidenced that left-wing local governments tend to have better levels of disclosure due to their higher orientation to social policies (Guillamón et al., Citation2011). On the contrary, other scholars found that municipal-owned companies located in regions governed by conservatives disclosed more information because they have greater incentives to improve their reputation and legitimacy in society as there is a perception that they are more concerned with economic aspects (Andrades et al., Citation2019).

For our study, it would be interesting to examine whether the presence of a politician within the board of directors of public water utilities affects the level of their ESG disclosures. The hybrid nature of public water utilities under study, with more than 50% of their shareholder equity held by a local government, justifies the analysis of this aspect. Focusing on the Spanish setting, it is well-known that there has been a proliferation of corruption scandals in traditional political parties in the last 10 years, regardless of their ideology (De la Higuera-Molina et al., Citation2019). Based on our theoretical framework, public water utilities with a board chairperson belonging to a traditional Spanish party have greater incentives to disclose ESG information because it could help improve their image with stakeholders and demonstrate that their behaviour is aimed at balancing their social and economic goals. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Andalusian public water utilities with a board chairperson belonging to a traditional Spanish party are more likely to disclose ESG information compared to others.

Parent institution’s commitment to transparency

Previous studies have documented that public-sector organizations that are better placed in rankings tend to have better levels of disclosure due to the social pressure for their positioning (Larran et al., Citation2019). It is expected that the best-placed public-sector organizations are powerful leaders in the movement for social change, which leads these institutions to promote the disclosure of information online to meet the demands of different stakeholders (Andrades et al., Citation2019). Thus, it may be expected that this same proactivity of the parent institution towards transparency will be extended to water utilities that depend on it. Furthermore, public water utilities whose parent institution has a higher level of transparency have greater incentives to disclose ESG information. According to our theoretical framework, these enterprises have been able to internalize transparency in their culture as a mechanism for reconciling their social and environmental goals, thereby conferring legitimacy with respect to their stakeholders (Argento et al., Citation2019; Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Consequently, the following hypothesis is raised:

H6: Andalusian public water utilities whose parent institution presents a higher level of commitment to transparency are more likely to disclose ESG information compared to others.

Company’s commitment to transparency

The design of a special section for transparency issues on companies’ websites could be an essential tool for any organization to publish their ESG disclosures, ensuring quick and free access to this type of information (Higgins et al., Citation2015). Andalusian public water utilities that have developed an individual section on their website to disclose ESG information demonstrate a corporate culture consistent with transparency principles (Andrades et al., Citation2021). Drawing on our theoretical framework, these companies would have better levels of ESG disclosure because their corporate culture aims to balance their different logics, thereby helping to gain legitimacy from their stakeholders (Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7: Andalusian public water utilities that have a transparency section on their websites are more likely to disclose ESG information.

Method

Sample selection

The sample consists of the entire population of public water utilities owned by local municipalities from Andalusia, identified by the General Intervention Board of the State Administration (IGAE). The researchers conducted the following search process between 13 July 2020 and 20 November 2020. In the first step, the researchers entered the institutional website of IGAE (https://www.igae.pap.hacienda.gob.es/sitios/igae/en-GB/paginas/inicio.aspx), and they selected the menu option ‘Inventory of entities of the public sector’ (INVENTE in Spanish), wherein enterprises owned by central, regional or local governments can be selected. Next, the authors entered into the entity finder web link that the IGAE webpage provides to find the list of public water utilities owned by local municipalities from Andalusia. To find these companies, the authors selected: (a) the term ‘enterprise’ (‘empresarial’) among the activity options (‘Actividad del sector público’); (b) the National Classification of Economic Activities (CNAE in Spanish) codes related to water utilities (‘E36. Captación, depuración y distribución de agua’ and ‘E37. Recogida y tratamiento de aguas residuales’); and the option ‘administration of local entities’ (‘Administración de las EELL’) in ‘assignment administration’ (‘Administración de adscripción’). On 20 November 2020, the list of Andalusian public water utilities owned by local municipalities was 38.

Data collection and treatment

The researchers conducted a content analysis of multiple sources to collect and analyse the ESG information disclosed by each of the 38 public water utilities sampled. This methodology, defined as a research technique that classifies the ESG information disclosed into several categories of items, has been widely used in previous research (Argento et al., Citation2019).

Although most publications have analysed annual or stand-alone sustainability reports (Patten et al., Citation2015), other scholars employed the institutional website as a source of information to capture the ESG information disclosed (Garde et al., Citation2017; Royo et al., Citation2019). Meanwhile, less attention has been devoted to combining different data sources to collect and analyse ESG disclosures (De Villiers et al., Citation2014). Some scholars have justified the use of a broad range of data sources to comprehensively capture the ESG disclosure activity in organizations like public water utilities (Larrinaga & Perez, Citation2008; De Villiers & Van Staden, Citation2011). In accordance with this statement, the authors use the following sources to collect the data: corporate websites, transparency portal in which public water utilities are required to disclose information in line with mandatory disclosure requirements, the stand-alone sustainability reports, non-financial information statements, financial statements, collective agreements, statutes, codes of conduct or codes of ethics. All these information sources are available within the institutional website of each company, and they could contain any type of information related to ESG issues. In addition to these sources, the authors examined external reporting channels, such as the website of the local municipality that owns the company. Also, the Spanish Accountability Portal (https://www.rendiciondecuentas.es/es/index.htm) was examined, as it collects the information provided by local entities according to the requirements contained in the Spanish Law 19/2013 on Transparency and Good Governance.

Consistent with the criticisms of Global Reporgting Initative (GRI) guidelines (Dumay et al., Citation2010) and following some literature recommendations on financial and non-financial information disclosure in the public sector (Caba et al., Citation2014), the following step was the design of a framework to capture the ESG disclosure in public water utilities. To do this, the authors performed an extensive review of reporting standards, guidelines, and frameworks frequently referenced in the literature to identify ESG key aspects. More specifically, the following international standards and frameworks were reviewed:

The most recent GRI guidelines together with the GRI 303 standard related to water and effluents and the GRI 306 standard focused on waste and effluents.

Integrated Information Reporting Framework.

United Nations Global Compact.

Sustainable Development Goals.

International Financial Reporting Standards.

International Standards of Accounting and Reporting.

Sustainability Accounting Standard Board guidance for water utilities.

South African Bureau of Standards (SABS) on water utilities.

In addition to this international normative review, the research team also analysed the applicable legal framework to determine the minimum disclosures for public water companies to comply with the law in terms of transparency, as well as some specific Spanish guidelines related to integrated reporting or the management of water utilities:

Spanish commercial law.

Spanish Law 19/2013 of 9 December on Transparency, Access to Public Information and Good Governance.

Spanish Royal Decree 18/2017 and subsequent Law 11/2018

Integrated reporting guidelines developed by the Spanish Accounting and Business Management Association.

Performance measurement for water utilities created by the Spanish Public Association of Water Utilities.

As a result, the researchers developed a tool composed of 172 indicators divided into 157 voluntary disclosure indicators and 15 mandatory disclosure indicators, which are grouped as follows:

Voluntary Information (by dimensions with the number of indicators in parentheses): Business model (26); Environment (25); Human Rights (11); Society and employee (42); Corruption (13); Diversity (8); Social impact (7); Suppliers (4); Consumers (6); Tax (1); Corporate governance (9); Finance (7).

Mandatory Information: Legal requirements (15).

As can be observed, our tool has been developed following an integrated reporting approach. It can help to capture the comprehensive disclosure of ESG information by meeting the demands of all stakeholders, as well as helping to provide insight related to value creation for the future (Farneti et al., Citation2019).

After creating the tool, the next stage involved the development of a disclosure index with a measurement unit where each information item was coded according whether or not it was disclosed. Although binary dichotomous scales (1 for disclosure and 0 for non-disclosure) have been mostly used in previous research, the authors opted for a coding system that ranges from 0 to 3. This system captured the quantity and the quality of ESG information disclosed (Kansal et al., Citation2018). This coding system was applied as follows: 0 for non-disclosure, 1 for narrative or qualitative disclosure, 2 for quantitative disclosure, and 3 for quantitative and comparative disclosure. Of the 157 voluntary indicators, 52 were qualitative and 105 were quantitative. Meanwhile, the 15 mandatory indicators were qualitative.

Regarding how the creation of the index was operationalized, the researchers developed partial disclosure indexes by dimension, and one global disclosure index that collects the set of indicators grouped in all dimensions. They were calculated by scaling the sum of the total indicators a public water utility discloses (in a dimension/total) by the maximum number of indicators that could be released (in a dimension/total). summarizes the list of voluntary and mandatory indicators according to their qualitative or quantitative nature. It also provides the maximum score to be achieved by dimension both for a public water utility and by the 38 companies sampled.

Table 1. Classification of indicators by dimension.

Three researchers collected and analysed the data as a strategy to improve the reliability of the coding process (Luque & Larrinaga, Citation2016). Each researcher coded a sample of the public water utilities selected, adopting the same criteria. A fourth researcher intervened to enhance the accuracy of the coding process resulting from different interpretations of the coding information (Larrinaga et al., Citation2018).

Empirical analysis

For this research, the authors employed a multiple linear regression analysis to determine how different variables can explain the level and quality of ESG disclosure in Andalusian public water utilities. To test the hypotheses, the researchers used three different regression models. Model 1 examines whether the level and quality of total ESG disclosure depend on the set of variables previously described. Model 2 focuses on determining whether the level of mandatory ESG disclosure is affected by these previous variables, and Model 3 analyses the level of voluntary ESG disclosure according to these factors.

Therefore, three dependent variables were used to measure the level of total, mandatory and voluntary ESG disclosure in Andalusian public water utilities. They were measured as follows:

Total disclosure index: This index measures the level and quality of the whole ESG disclosure by the 38 Andalusian public water utilities sampled in this study according to the 172 indicators that constitute the instrument tool.

Mandatory disclosure index: This index measures the level and quality of ESG information compulsorily disclosed by the 38 Andalusian public water utilities sampled in this study according to the 15 mandatory indicators that comprise the instrument tool.

Voluntary disclosure index: This index measures the level and quality of ESG information voluntarily disclosed by the 38 Andalusian public water utilities sampled in this study according to the 157 voluntary indicators that compose the instrument tool.

The independent variables were measured as shows.

Table 2. Variable definition.

Results

Voluntary and mandatory ESG disclosure activity

shows the level and quality of voluntary ESG disclosures. On a global level, public water utilities have had an implementation rate of 8.81% for the 157 voluntary indicators. This rate reveals that commitment to ESG disclosure in public water utilities remains low and fragmented among different categories. Broken down by dimensions, public water utilities have had better levels of ESG disclosure for the business model, followed by the finance dimension. Regarding the business model, the set of indicators that make up the business model are related to the description of the company and its profile, strategic goals, or the business environment. This type of information seems to be aimed at revealing a symbolic image of the nature of the company’s activity. Thus, ESG disclosure from the business model dimension might be driven by visibility reasons for public water utilities. Meanwhile, the disclosure of ESG information from the finance dimension might be explained by this information being easily extracted from the financial statements. The third and fourth dimensions that have received better scores than the others are consumers and the environment. On the one hand, public water utilities provide a service of vital relevance for the community, so it is not surprising their concern about the disclosure of ESG information related to their commitment to consumers. On the other hand, these enterprises are belonging to a high-risk industry because their activity has a high environmental impact. Thus, it seems to make sense that these companies have shown some awareness of the disclosure of information related to their environmental impact. The disclosure of ESG information in the dimensions related to society and employee, diversity, social impact, corporate governance, and suppliers are ranked in intermediate positions. Finally, public water utilities have paid little attention to disclosing ESG information about the following dimensions: tax, corruption, and human rights. This result may be explained by these companies feeling that these information items are not relevant for meeting the demands of their stakeholders.

Table 3. Level of voluntary disclosure on ESG information in public water utilities.

provides the level of compliance with mandatory ESG disclosure in public water utilities. The global level of disclosure shows an implementation rate of 35.61% for the 15 indicators. Individually, public water utilities have been more engaged with the disclosure of their functions, followed by information related to contracts, normative, administrative structure, salaries, and financial statements. Next, public water utilities have devoted some attention to the disclosure related to covenants, grants and subsidies, budgets, organizational chart and plans and programmes. The items associated with the annual declaration of assets and statistical report about the level of compliance have had the poorest levels of disclosure.

Table 4. Level of mandatory disclosure on ESG information in public water utilities.

Determinants of ESG disclosure activity

shows the bivariate Spearman correlation coefficients among all dependent and independent variables employed. Results show some correlations statistically significant at the 1% level, such as the association between the level of ESG disclosures and organizational size or media exposure. Also, there are some correlations among independent variables, but we did not find multicollinearity problems as the variance inflation factors (not reported) did not exceed the critical value of 10.

Table 5. Bivariate Spearman correlation.

reports the three regression models through which the researchers analyse whether the level and quality of total, voluntary and mandatory disclosure of ESG information is influenced by the independent variables selected. According to the R2, the set of independent variables explains 69.58%, 62.20% and 69.31% of the variation of the dependent variable for each of the three models. The F test shows that the three regression models are statistically significant. Multicollinearity is not a serious problem in our research because mean variance inflation factor values range from 1.23 to 1.90 in the three models (not reported).

Table 6. Regression results on the determinants associated with the ESG disclosure activity in Andalusian public water utilities.

Regarding Model 1, reveals that the disclosure of ESG information in public water utilities is positively associated with the institutional size and the commitments to transparency of the parent institution as well as the own water company. On the other hand, media exposure, the degree of public ownership and the presence of a chairwoman on the board of directors have a negative influence on the ESG disclosure activity. According to the standardized regression coefficients, the most influential variable in explaining better levels of ESG disclosure is the size, measured by the number of employees, and the availability of a transparency section, followed by public ownership. Consistent with what was stipulated in Hypothesis 1, large public water utilities in Andalusia have had higher levels of ESG disclosure than others. However, higher media exposure is not positively associated with reporting activity. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is not supported. Drawing on Hypothesis 3, which stipulated that the extent and quality of ESG disclosure depends on the proportion of public or private ownership, results support it. Attending to Hypothesis 4, female leadership on the board of directors is not positively associated with ESG disclosure; therefore, our results do not confirm our previous assumption. Finally, the regression coefficients show that public water utilities whose parent institution is highly committed to transparency, and companies with a transparency section on their website, reached better levels of ESG disclosure, confirming the initial assumptions. Hence, Hypotheses 6 and 7 cannot be rejected. Regarding political ideology (Hypothesis 5), the results reveal that it is negatively associated with ESG disclosure in public water utilities in contrast to the initial assumption. However, this association is not statistically significant.

Concerning the Mandatory Disclosure Index (Model 2) and the Voluntarily Disclosure Index (Model 3), results point out that large public water utilities with a transparency section on their websites have better levels of ESG disclosure. More specifically, Model 3 reveals similar findings as in the case of the Total Disclosure Index, except for political ideology. This variable has a significant negative effect on voluntary ESG reporting. Regarding this, it can be appreciated that companies led by politicians from traditional parties tend to report significantly higher levels of mandatory information and lower levels of voluntary information. A contrary effect of media exposure on the disclosure of ESG information is observed depending on whether it is required by law. However, it only contributes to significantly explaining the variance of the Voluntary Disclosure Index. Similarly, the presence of private stake in this kind of firm only has a significant effect when voluntary ESG reporting is under analysis. In fact, it is the third most relevant explanatory factor in Model 3.

Discussion

This paper has tried to contribute to the ESG disclosure activity from a theoretical point of view by employing institutional logics approach to understand how different variables can impact ESG reporting practices of public water utilities. It responds to the call made by previous scholars to use the notion of hybridity to improve our understanding of the level of ESG disclosure in hybrid organizations (Grossi et al., Citation2022). To accomplish this task, the researchers have designed a new tool composed of 172 indicators to capture the ESG disclosure activity in public water utilities.

As expected, this study has identified three sets of variables that affect the level of ESG disclosure in Andalusian public water utilities. The first set of variables relates to visibility, including organizational size, which has a significant impact on ESG disclosure levels in public water utilities. The second set of variables relates to cultural aspects, such as the higher levels of transparency of the parent institution and the availability of a transparency section on their websites, which also influences ESG disclosure levels. The third set of variables is the proportion of public ownership, which acts as a hybrid factor and affects ESG disclosure patterns in public water utilities.

Based on organizational size, large public water utilities could have greater incentives to disclose ESG information because they are highly exposed to public scrutiny (Andrades & Larran, Citation2019; Garde et al., Citation2017). These companies have achieved better levels of ESG disclosure because they face more pressure from different stakeholders to reconcile their social and market logics in order to be considered legitimate (Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021; Nicolò et al., Citation2021). Large public water utilities have more resources, and this might suggest that their accountants have a set of professional skills that conform to prevailing norms and values (Haraldsson & Tagesson, Citation2014). Thus, the adoption of ESG disclosure is configured as a norm that meets societal expectations (Andrades et al., Citation2021).

According to transparency culture variables, some public water utilities seem to have unconsciously institutionalized their commitment to transparency of ESG information, making it a habit within their organizational practices (Oliver, Citation1991). This kind of company experiences a sense of belonging to the community, and the disclosure of ESG information is understood as part of their moral obligation to society, combining their different logics to meet the demands of their stakeholders, which also gives them legitimacy (Andrades et al., Citation2021).

Regarding the proportion of public ownership of the public water utility, our results revealed that public water utilities with lower levels of public ownership disclosed more ESG information than others. In line with previous studies, the greater presence of private owners within a public water utility could suggest that these companies place more emphasis on their financial performance (Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Following this logic, these public water utilities could have greater incentives to demonstrate the close relationship between the financial, environmental, and social dimensions of their activity (Garde et al., Citation2017). According to the theory of institutional logics coupled with stakeholder and legitimacy theories, the disclosure of ESG information would be helpful to reconcile their different and conflicting logics (the social and the commercial), and this could provide them societal respect and meet the informational needs of their private and public stakeholders (Manes-Rossi et al., Citation2021; Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021). Therefore, this research shows that the ESG reporting of mixed water companies in which a well-known private firm has a stake could be more related to the management and transparency culture of this company than to the transparency culture of the local public entity.

Contrary to our initial expectation, the findings have revealed a negative association between the level of ESG disclosure and two variables: the exposure to the media and the leadership exerted by a woman within the board chair. Consistent with Garde et al. (Citation2017), these factors might not be decisive in determining the level of ESG disclosure in public water utilities because companies more exposed to the media and headed by a woman might not consider this type of disclosure as essential.

Nevertheless, the general picture indicates that the extent to which public water utilities are engaged with ESG disclosure practices remains low. Different scholars have argued that the hybrid nature of these enterprises confers them with a complex governance structure, and this could introduce some problems in undertaking ESG disclosure practices (Argento et al., Citation2019). The disclosure of ESG information in public water utilities, as they have to balance the demands of a multiplicity of stakeholders (Argento et al., Citation2019), is challenging because it is not clear ‘who is accountable for whom’ and ‘for what’ (Grossi et al., Citation2022; Royo et al., Citation2019). According to the theory of institutional logics, the hybrid nature of public water utilities has negatively affected their capacity to disclose ESG information as they have to deal with two conflicting logics (Argento et al., Citation2019; Yetano & Sorrentino, Citation2021): the provision of public service to society (the social logic) and the pursuit of financial performance (the market logic).

Our findings have also demonstrated that public water utilities have low levels of compliance with mandatory ESG disclosure requirements. Previous studies on social and environmental accounting research have documented that government regulation of ESG disclosure alone does not lead to better levels of disclosure among private- and public-sector organizations (Larrinaga et al., Citation2018; Luque & Larrinaga, Citation2016). To quote Bebbington et al. (Citation2012, p. 90), ‘formal legislation alone may not be sufficient to create a norm’. Accordingly, the need to create a proper normative climate in which structural changes should accompany the effective implementation of a law is suggested (Luque & Larrinaga, Citation2016).

Conclusion

This article has empirically documented that, although some determinants are associated with the ESG disclosure activity in public water utilities, the level and quality of such disclosure is relatively low. Hence, there is large room for improvement in the ESG disclosure practice of these enterprises.

Consistent with the findings, there are some practical implications. First, the results of this paper might be useful for managers and practitioners operating in Andalusian public water utilities. Our results can help these managers and practitioners to become aware of the need to take appropriate measures to improve their commitment to the transparency of ESG information. To achieve this, it would be recommendable that managers and practitioners acquire the necessary skills in terms of sustainability to improve their companies’ disclosure levels. Second, we also recommend that managers, practitioners, regulators and policymakers work together to include some enforcement mechanisms in current regulations (e.g., Spanish Law 19/2013 on Transparency and Good Governance) to enhance compliance with mandatory ESG reporting requirements by public water utilities. Lastly, it would be valuable for different actors, such as academics, regulators or managers of companies owned by municipalities, discuss the need to extend the scope of application of the non-financial information regulation to a wide range of organizations. It could help to institutionalize the commitment of different organizations towards ESG reporting.

This analysis has some limitations. First, it draws on a limited number of public water utilities belonging to one Spanish region, Andalusia. Thus, although the sample used encompasses all the public water utilities placed in this region, it is necessary to be cautious when the results of our regression models are interpreted more widely. In future, it could be convenient to expand this study to other regions of Spain to have a better understanding of the ESG disclosure activity in the Spanish setting. Also, this research could be extended to other European countries to demonstrate whether the country of origin affects the ESG disclosure activity in public water utilities. Second, the paper adopts an exploratory and quantitative approach to examine the determinants associated with the disclosure of ESG information. To arrive at meaningful conclusions, a future investigation could focus on qualitative research, examining a small, select group of companies with a long tradition in ESG disclosure. It would require conducting semi-structured interviews with managers to understand the underlying drivers that motivate these companies to undertake ESG disclosure, as well as the dynamics and processes associated with the evolution of this activity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, C., & McNicholas, P. (2007). Making a difference: Sustainability reporting, accountability and organisational change. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 382–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570710748553

- Andrades, J., & Larran, M. (2019). Examining the amount of mandatory non-financial information disclosed by Spanish state-owned enterprises and its potential influential variables. Meditari Accountancy Research, 27(4), 534–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-05-2018-0343

- Andrades, J., Larran, M., Muriel, M. J., Calzado, M. Y., & Lechuga, M. P. (2021). Online sustainability disclosure by Spanish hospitals: An institutionalist approach. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 34(5), 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-09-2020-0259

- Andrades, J., Martinez-Martinez, D., Larrán, M., & Herrera, J. (2019). Online information disclosure in Spanish municipal-owned enterprises. Online Information Review, 43(5), 922–944.

- Andrades, J., Muriel de Los Reyes, M. J., & Larrán Jorge, M. (2022). How far can mandatory requirements drive increased levels of disclosure? Public Money & Management, 43(8), 793–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2022.2045124

- Argento, D., Grossi, G., Persson, K., & Vingren, T. (2019). Sustainability disclosures of hybrid organizations: Swedish state-owned enterprises. Meditari Accountancy Research, 27(4), 505–533. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-07-2018-0362

- Bansal, P. (2005). Evolving sustainability: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.441

- Bebbington, J., Higgins, C., & Frame, B. (2009). Initiating sustainable development reporting: Evidence from New Zealand. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 22(4), 588–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570910955452

- Bebbington, J., Kirk, E. A., & Larrinaga, C. (2012). The production of normativity: A comparison of reporting regimes in Spain and the UK. Accounting, Organization and Society, 37(2), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2012.01.001

- Bebbington, J., Schneider, T., Stevenson, L., & Fox, A. (2020). Fossil fuel reserves and resources reporting and unburnable carbon: Investigating conflicting accounts. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 66, 102083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2019.04.004

- Bermejo-Martín, G., & Rodríguez-Monroy, C. (2019). Sustainability and water sensitive cities: Analysis for intermediary cities in Andalusia. Sustainability, 11(17), 4677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174677

- Bruton, G. D., Peng, M. W., Ahlstrom, D., Stan, C., & Xu, K. (2015). State owned enterprises around the world as hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1), 92–114. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0069

- Caba, M. C., Rodríguez, M. P., & Lopez, A. (2014). The determinants of government financial reports online. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 42, 5–37. https://www.rtsa.ro/tras/index.php/tras/article/view/15

- Cabello, J. M., Navarro-Jurado, E., Thiel-Ellul, D., Rodríguez-Díaz, B., & Ruiz, F. (2021). Assessing environmental sustainability by the double reference point methodology: The case of the provinces of Andalusia (Spain). International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 28(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2020.1778582

- Contrafatto, M. (2014). The institutionalization of social and environmental reporting: An Italian narrative. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 39(6), 414–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2014.01.002

- De la Higuera-Molina, E. J., Plata-Díaz, A. M., López- Hernández, A. M., & Zafra-Gómez, J. L. (2019). Dynamic-opportunistic behaviour in local government contracting-out decisions during the electoral cycle. Local Government Studies, 45(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1533819

- De Villiers, C., Low, M., & Samkin, G. (2014). The institutionalisation of mining company sustainability disclosures. Journal of Cleaner Production, 84, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.089

- De Villiers, C., & Van Staden, C. J. (2011). Where firms choose to disclose voluntary environmental information. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 30(6), 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2011.03.005

- Dumay, J., Guthrie, J., & Farneti, F. (2010). GRI sustainability reporting guidelines for public and third sector organizations: A critical review. Public Management Review, 12(4), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.496266

- Farneti, F., Casonato, F., Montecalvo, M., & De Villiers, C. (2019). The influence of integrated reporting and stakeholder information needs on the disclosure of social information in a state-owned enterprise. Meditari Accountancy Research, 27(4), 556–579. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-01-2019-0436

- Farooq, M. B., & de Villiers, C. (2019). Understanding how managers institutionalise sustainability reporting: Evidence from Australia and New Zealand. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(5), 1240–1269. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2017-2958

- Ferdous, M. I., Adams, C. A., & Boyce, G. (2019). Institutional drivers of environmental management accounting adoption in public sector water organisations. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(4), 984–1012. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-09-2017-3145

- Freeman, E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman.

- Garcia-Benau, M. A., Bollas-Araya, H. M., & Sierra-García, L. (2022). Non-financial reporting in Spain. The effects of the adoption of the 2014 EU Directive: La información no financiera en España. Los efectos de la adopción de la Directiva de la UE de 2014. Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review, 25(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.6018/rcsar.392631

- Garcia-Sanchez, I., Frias, J., & Rodriguez, L. (2013). Determinants of corporate social disclosure in Spanish local governments. Journal of Cleaner Production, 39, 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.08.037

- Garde, R., Rodriguez, M. P., & Lopez, A. M. (2017). Corporate and managerial characteristics as drivers of social responsibility disclosure by state-owned enterprises. Review of Managerial Science, 11(3), 633–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-016-0199-7

- Gendron, Y. (2018). Beyond Conventional Boundaries: Corporate Governance as Inspiration for Critical Accounting Research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 55, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2017.11.004

- Giner, B., & Luque-Vilchez, M. (2022). A commentary on the “new” institutional actors in sustainability reporting standard-setting: A European perspective. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, (ahead-of-print), 13(6), 1284–1309. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-06-2021-0222

- Grossi, G., Papenfuß, U., & Tremblay, M. (2015). Corporate governance and accountability of state-owned enterprises. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 28(4/5), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-09-2015-0166

- Grossi, G., Reichard, C., Thomasson, A., & Vakkuri, J. (2017). Theme: Performance measurement of hybrid organizations – Emerging issues and future research perspectives. Public Money and Management, 37(6), 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2017.1344007

- Grossi, G., Vakkuri, J., & Sargiacomo, M. (2022). Accounting, performance and accountability challenges in hybrid organisations: A value creation perspective. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability, 35(3), 577–597. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2021-5503

- Guillamón, M. D., Bastida, F., & Benito, B. (2011). The determinants of local government’s financial transparency. Local Government Studies, 37(4), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2011.588704

- Haraldsson, M., & Tagesson, T. (2014). Compromise and avoidance: The response to new legislation. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 10(3), 288–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-10-2012-0096

- Higgins, C., Milne, M. J., & Van Gramberg, B. (2015). The uptake of sustainability reporting in Australia. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(2), 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2171-2

- Higgins, C., Stubbs, W., & Milne, M. (2018). Is sustainability reporting becoming institutionalised? The role of an issues-based field. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(2), 309–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2931-7

- Kansal, M., Joshi, M., Babu, S., & Sharma, S. (2018). Reporting of corporate social responsibility in central public sector enterprises: A study of post mandatory regime in India. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(3), 813–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3253-0

- KPMG. (2022). Big shifts, small steps. The KPMG Survey of Sustainability Reporting 2022.

- Larran, M., Andrades, F. J., & Herrera, J. (2019). An analysis of university sustainability reports from the GRI database: An examination of influential variables. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(6), 1019–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1457952

- Larrinaga, C., Luque, M., & Fernandez, R. (2018). Sustainability accounting regulation in Spanish public sector organizations. Public Money & Management, 38(5), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2018.1477669

- Larrinaga, C., & Perez, V. (2008). Sustainability accounting and accountability in public water companies. Public Money and Management, 28(6), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2008.00667.x

- Li, T., & Belal, A. (2018). Authoritarian state, global expansion and corporate social responsibility reporting: The narrative of a Chinese state-owned enterprise. Accounting Forum, 42(2), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2018.05.002

- Lloyd Owen, D. (2022). The private sector and water services: A reflection. Water International, 47(7), 1032–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2022.2133416

- Luque, M., & Larrinaga, C. (2016). Reporting models do not translate well: Failing to regulate CSR reporting in Spain. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 36(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2016.1149301

- Manes-Rossi, F., Nicolò, G., Tiron, A., & Zanellato, G. (2021). Drivers of integrated reporting by state-owned enterprises in Europe: A longitudinal analysis. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(3), 586–616. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-07-2019-0532

- McDonald-Kerr, L. (2017). Water, water, everywhere: Using silent accounting to examine accountability for a desalination project. Sustainability, Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 8(1), 43–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-12-2015-0116

- Michelon, G. (2011). Sustainability disclosure and reputation: A comparative study. Corporate Reputation Review, 14(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2011.10

- Milne, M. J., & Gray, R. (2013). W(h) ither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1543-8

- Molinos-Senante, M., Maziotis, A., & Villegas, A. (2022). Performance analysis of Chilean water companies after the privatization of the industry: The influence of ownership. Water International, 47(1), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2021.1999761

- Montesinos, V., & Brusca, I. (2019). Non-financial reporting in the public sector: Alternatives, trends and opportunities: La información no financiera en el sector público: Alternativas, tendencias y oportunidades. Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review, 22(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.6018/rcsar.383071

- Nicolò, G., Zanellato, G., Manes, F., & Tiron-Tudor, A. (2021). Corporate reporting metamorphosis: Empirical findings from state-owned enterprises. Public Money & Management, 41(2), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1719633

- Ntim, C. G., Soobaroyen, T., & Broad, M. J. (2017). Governance structures, voluntary disclosures and public accountability: The case of UK higher education institutions. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 30(1), 65–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2014-1842

- Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/258610

- Passetti, E., & Rinaldi, L. (2020). Micro-processes of justification and critique in a water sustainability controversy: Examining the establishment of moral legitimacy through accounting. The British Accounting Review, 52(3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2020.100907

- Patten, D. M., Ren, Y., & Zhao, N. (2015). Standalone corporate social responsibility reporting in China: An exploratory analysis of its relation to legitimation. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 35(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2015.1007467

- Perez, V., Garcia, J., & Casasola, M. A. (2016). La elaboración de memorias GRI sobre responsabilidad social por entidades de gestión pública y mixta de abastecimiento y saneamiento de aguas españolas. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 87, 1–33. https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/ciriecespana/article/view/6864

- Rao, K., & Tilt, C. (2016). Board diversity and CSR reporting: An Australian study. Meditari Accountancy Research, 24(2), 182–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-08-2015-0052

- Reverte, C. (2009). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by Spanish listed firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(2), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9968-9

- Reverte, C. (2015). The new Spanish corporate social responsibility strategy 2014–2020: A crucial step forward with new challenges ahead. Journal of Cleaner Production, 91, 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.041

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M. P., Garde Sánchez, R., & López Hernández, A. M. (2015). Managers as drivers of CSR in state-owned enterprises. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 58(5), 777–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2014.892478

- Royo, S., Yetano, A., & García-Lacalle, J. (2019). Accountability styles in State-Owned enterprises: The good, the bad, the ugly … And the pretty. Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review, 22(2), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.6018/rcsar.382231

- Saez-Martin, A., Caba-Perez, C., & Lopez-Hernandez, A. (2017). Freedom of information in local government: Rhetoric or reality? Local Government Studies, 43(2), 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1269757

- Tan, L. K., & Egan, M. (2018). The public accountability value of a triple bottom line approach to performance reporting in the water sector. Australian Accounting Review, 28(2), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12173

- Tarquinio, L., & Xhindole, C. (2022). The institutionalisation of sustainability reporting in management practice: Evidence through action research. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(2), 362–386. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2020-0249

- Timmerman, J. G., de Vries, S., Berendsen, M., van Dokkum, R., van de Guchte, C., Vlaanderen, N., Broek, E., & van der Horst, A. (2022). The Information Strategy Model: A framework for developing a monitoring strategy for national policy making and SDG6 reporting. Water International, 47(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2021.1973856

- Tirado-Valencia, P., Cordobés-Madueño, M., Ruiz-Lozano, M., & De Vicente-Lama, M. (2019). Integrated thinking in the reporting of public sector enterprises: A proposal of contents. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(3), 435–453. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-03-2019-0458

- Tregidga, H., & Milne, M. J. (2006). From sustainable management to sustainable development: A longitudinal analysis of a leading New Zealand environmental reporter. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(4), 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.534

- Vinnari, E., & Laine, M. (2013). Just A passing fad?: The diffusion and decline of environmental reporting in the finnish water sector. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(7), 1107–1134. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2012-01002

- Yetano, A., & Sorrentino, D. (2021). Accountability disclosure of SOEs: Comparing hybrid and private European news agencies. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(2), 294–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-04-2020-0873