Abstract

Over the past 40 years, tourism has developed to become a sector of global economic, social and environmental significance. This paper provides a retrospective overview of the massive expansion and evolving geography of international and domestic tourism over the last 40 years, including the factors that enabled and challenged this growth, in order to contextualize a discussion of what the next 40 years may hold for global tourism. Social, technical, economic, environmental and political dimensions influencing tourism over the past and future 40 years are identified, together with a synthesis of available long-range scenarios of tourism futures to 2050. Comparisons with selected non-tourism scenarios suggest that current assessments of tourism futures are limited in scope, and that the tourism sector may have much to learn from scenario building and forecasting from other economic sectors and analyses of global grand challenges. Reconciling anticipated tourism growth with the sustainability and development imperatives of the next 40 years are discussed.

Introduction

As Tourism and Recreation Research celebrates its fortieth year of publication, it is intriguing to reflect on the magnitude of change in global tourism that the journal and its hundreds of contributors have borne witness to and sought to understand through diverse disciplinary lenses. During this 40-year period, international tourism has developed to become an economic, social and environmental force of global significance. Even more fascinating is to ask ‒ what of the future? What could the next 40 years hold for the tourism sector? What is the potential place of tourism in the global economy? What is its role in promoting sustainable development and positive social change? Are there challenges that could or perhaps should preclude its continued growth? While long-term forecasts and scenarios of tourism are fraught with uncertainty, in this era of rapid technological, economic, social and political change, where globalization has increased the connectivity and complexities of economic and governance systems, the need for techniques that can contribute to future preparedness has arguably never been greater.

This paper explores this central question in three parts. It begins by briefly reflecting on some of the major Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental and Political (also referred to as ‘STEEP’) changes that have transformed the tourism sector over the last 40 years. The future of tourism is set in motion by the past, and retrospective is helpful for tourism students and young professionals to understand how far the sector has developed and to comprehend the scale of changes that could occur over the next 40 years. As the old cliché reminds us, ‘you can't know where you are going until you know where you have been’. The paper thus provides a synthesis of available long-range projections of global international tourism and a comparative analysis of the major drivers that experts deem most salient to the future of tourism. Finally, it considers insights on major future STEEP influences from outside of the tourism literature. It compares the ‘top 10’ risks of a recent tourism Delphi study (von Bergner & Lohmann, Citation2014) to those of World Economic Forum's (Citation2014) Global Risks Report, and using the example of world energy futures it discusses the value of interpreting non-tourism sector scenarios to better understand future challenges for the tourism sector.

Looking back 40 years: a global revolution in tourism

A comprehensive discussion of the evolution of the global tourism sector over the latter decades of the twentieth century and early twenty-first century is beyond the scope of this paper. The history of modern tourism has been the subject of multiple authoritative books, to which the reader is referred (e.g. Gyr, Citation2010; Löfgren, Citation2002; Page, Citation2003).

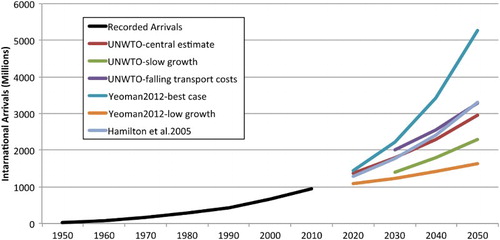

International tourism has grown to become one of the largest global economic sectors and a significant contributor to many national and local economies. Perhaps the best available indicator of the scale of global tourism growth over the last 40 years is the number of international tourist arrivals. The transition of tourism from an exclusive activity enjoyed by the elite to emergent mass tourism took place in the first half of the twentieth century (Weaver & Lawton, Citation2006). By 1970, it is estimated that there were 165.8 million international tourist arrivals (), up from only 69.3 million in 1960. Over the next four decades the number of international tourist arrivals grew exponentially to 940 million in 2010. Notably, in 2012 global international arrivals surpassed 1 billion for the first time (United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], Citation2014).

Figure 1. International tourist arrivals. Data sources: Recorded historical arrivals – United Nations World Tourism Organization (Citation2014). Projected arrivals: United Nations World Tourism Organization (Citation2014); Yeoman (Citation2012); Hamilton, Maddison, and Tol (Citation2005); United Nations Environment Programme (Citation2012).

As the scale of international tourism has grown, its geography has also evolved (). Europe and North America dominated international arrivals in 1970 at nearly 94% of the global market share. By 2010, the market share of these two regions had declined substantially to 67%, while in the same 40 years international arrivals to Asia and Pacific and the Middle East regions had increased almost six-fold. As of 2010, the proportion of international arrivals to advanced (53%) and emerging (47%) economies had almost reached an even distribution (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2014). As the next section will discuss, this geographic transition in regional markets is expected to continue over the next 40 years.

Table 1. The changing geography of international tourism.

The increase in international tourism is only part of the remarkable evolution of the tourism system over the last 40 years. Notably, the volume of domestic tourism trips has been estimated to be four times larger than the number of international trips. Although consistent data on worldwide domestic tourism remain problematic because of the varied definitions of domestic travel activity, an estimated 4.7 billion domestic arrivals occurred in countries with available data in 2010 (Cooper & Hall, Citation2013).

While international arrivals are among the most precisely monitored longitudinal indicators available for the tourism sector, it nonetheless provides a distorted representation of the relative importance of regions to global tourism. The political salience of monitoring the movement of people across international borders made it practical to measure international tourist arrivals. The concentration of relatively small countries with monitored borders in Europe create conditions for generating millions of international arrivals, while in large countries such as the US or China there are much longer journeys (e.g. Madrid to Moscow by air is 3400 km, while New York to Los Angeles is 3900 km) where travellers never cross a border to be counted as a tourist. For example, 82% of the 508.7 million international arrivals in the Europe tourism region in 2010 were generated within the region (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2011), while the estimated nearly 2 billion domestic person-trips per year in the US (Shifflet, & Associates Ltd & IHS Global Insight, Citation2008), many of which could be counted as much longer trips, are rarely considered in measurements of the global tourism sector.

Even more important to a comprehensive understanding of the ongoing evolution of global tourism is to consider the tremendous growth in domestic tourism in some of the world's most populous emerging economies. For example, China recorded an estimated 2.1 billion domestic tourist arrivals in 2010 (China National Tourism Administration, Citation2012), continuing its tremendous growth since the mid-1990s (up from 780 million in 2001). Similarly strong growth in domestic tourism has occurred in India, which recorded 740 million domestic tourist arrivals in 2010, an increase from 202 million in 2000 (Government of India, Citation2011). The Brazilian government's numbers reveal similar pattern of growth, with the number of domestic trips increasing from 139 million in 2005 to 186 million in 2010, while the number of international tourist arrivals stayed relatively constant at just over 5 million (King, Citation2013).

While few individual components of the tourism system have been monitored well at the global scale over this period of mass tourism expansion, there are some indicators that reveal how the infrastructure to transport and accommodate the expanding number of tourists has increased. The airline industry has experienced substantial growth in terms of both aircraft and passenger traffic over the last 40 years. Aviation industry data show there were just over 3700 aircraft in the global commercial fleet (greater than 100 seats) in 1970 (Airbus, Citation2014; Boeing, Citation2014). The world commercial airline fleet expanded to over 9100 aircraft by 1990 and has doubled in size in the last 20 years to over 21,000 aircraft in 2010. While the global commercial aircraft fleet thus increased nearly six-fold from 1970 to 2010, passenger traffic as measured by ‘revenue passenger kilometres’ (RPK) increased nearly nine-fold in the same period, from 500 billion RPK in 1970 to 4500 billion in 2010 (Airbus, Citation2014).

Growth in the global tourism system is also evident in accommodation capacity. According to the UNWTO (Citation2012) dataset, the global number of rooms in hotels and other forms of accommodation increased from 13.3 million in 1995 to 20.2 million in 2009/2010. Notably, available data for 1995 includes 175 countries, while data for 2009/2010 are limited to only 143 countries. The figure of 20.2 million hotel rooms in 2010 is thus a substantial underestimate as it does not consider hotel rooms in at least 50 countries, including Russia or Canada, each with hundreds of thousands of hotel rooms. Growth in the 143 countries for which data are available suggests an increase in room capacity by 61% over the period 1995–2010. Extrapolating this growth rate to the 32 countries for which only 1995 data exists suggests that in 2010 there were an additional 0.8 million rooms in these countries, and hence at least 21.0 million hotel rooms globally. This number is likely to have grown considerably in the past five years, and does not include room capacity in at least another 18 countries, considering that the UN recognizes 193 member states (www.un.org/members).

shows the regional share of total hotel room numbers, as well as growth by region in the period 1995–2009/2010. The Americas and Europe remain the most important regions in terms of hotel rooms, representing 38% and 34% of hotel rooms, respectively. Growth in accommodation capacity over the 15-year period studied has been strong in these regions, with 40% (Europe) and 59% (Americas). Third in terms of absolute room capacity is Asia and the Pacific region, with approximately 23% of the global total, and growth by 54%. Middle East (3%), Africa (2%) and South Asia (1%) have limited importance in room capacity, but huge differences in growth can be observed: while Africa grew by 12% since 1995, room numbers in the Middle East almost tripled.

Table 2. Hotel room distribution and growth 1995–2009/2010.

Over the past 40 years tourism has transformed from an emergent economic sector, largely concentrated in OECD countries, to one of global economic, social and environmental significance. The challenges of measuring the size and distribution of tourist flows domestically and internationally over time are compounded when attempting to assess the positive and negative impacts of tourism.

As has been discussed at length elsewhere, because tourism is not a distinct sector in the world trade system of accounts, its economic significance must be ‘revealed’ by compiling insights from a range of indicators in other sectors (e.g. accommodation, transportation). Only in the last decade have robust estimates of the contribution of the tourism sector to the global economy become available. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (Citation2014), the total contribution (direct and indirect) of the travel and tourism sector to gross domestic product (GDP) has grown from an estimated $5.5 trillion in 2003 to $6.9 trillion in 2013 (approximately 9.5% of global GDP). In 2004, the worldwide total contribution (direct and indirect) of travel and tourism to employment was 214 million jobs or 8.1% of global employment (up from just over 7% in 1988) (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2014), and by 2013 it reached an estimated 265 million jobs (or 8.9%) (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2014).

Like the geography of international arrivals, the distribution of economic benefits of tourism has evolved substantially in the last 40 years. Much of the growth in tourism since the mid-1990s has been concentrated in emerging economies. In 2000, approximately 75% of the contribution of tourism to national GDP was concentrated in developed countries (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2011). By 2010, this had dropped to an estimated 66%. Tourism has become one of the five top export earners in over 150 countries, while in 60 countries it is the number one export sector (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [UNCTAD], Citation2010). It is also the main source of foreign exchange for one-third of developing countries and one-half of least developed countries (LDCs) (United Nations World Tourism Organization & United Nations Environmental Programme [UNWTO & UNEP], Citation2011). As a consequence, the UNWTO, WTTC, World Economic Forum [WEF] and international development organizations believe international tourism holds great promise as a means of poverty reduction and contributes to the United Nation's Post-2015 Development Agenda (United Nations Development Programme, Citation2013). However, international tourism as a development strategy to achieve welfare equity and poverty reduction has long been substantially criticized (Hall & Lew, Citation2009).

Although analysis of the social and environmental consequences of the tourism sector emerged and became central themes of tourism scholarship over the last 40 years (Bramwell & Lane, Citation1993; Hall & Page, Citation2006; Mathieson & Wall, Citation1982), relevant global scale indicators are less developed and incomplete (Rutty, Gössling, Scott, & Hall, Citation2015). It is increasingly recognized that global tourism has grown to a size that it is no longer inconsequential with respect to environmental and social change. Tourism is both dependent on natural resources and contributes to the depletion of these resources. Understanding of the historical evolution of resource consumption and pollution from the global tourism sector remains very limited.

An estimate by two independent analyses found that tourism contributed approximately 5% to global anthropogenic emissions of CO2 in 2005, corresponding to 1304 Mt CO2 (Scott et al., Citation2008; World Economic Forum, Citation2009). In terms of energy use, this equates to 435 Mt of fuel, or approximately 17,500 Peta-joules of energy. Global freshwater consumption by the tourism sector is estimated to account for less than 1% (Gössling et al., Citation2012), but the overall water use for infrastructure construction, fuel and food production are considerably larger. For example, Cazcarro, Hoekstra, and SánchezChóliz (Citation2014) calculated that the net water footprint of tourism in Spain alone is seven times Gössling et al.’s (Citation2012) global estimate. It was estimated that leisure-related land use in the late 1990s amounted to approximately 515,000 km2, or 0.5% of the biologically productive area (Gössling, Citation2002). Since 2000, an estimated 4% of the total global sale of lands has been for tourism related properties (Anseeuw, Wily, Cotula, & Taylor, Citation2012). However, tourism is also an important economic factor behind heritage land and habitat conservation in many countries. In terms of food consumption, tourists eat an estimated 75 billion meals per annum, particularly higher-order foodstuffs (Gössling, Garrod, Aall, Hille, & Peeters, Citation2011). The environmental footprint associated with this food consumption has a much wider range of sustainability implications, including land conversion and the associated loss of biodiversity and ecosystems, changes in global biogeochemical processes, water consumption, the use of substances potentially harmful to human health (such as pesticides and herbicides) and the food service sector's contribution to global GHG emissions (Rutty et al., Citation2015). Hall and Lew (Citation2009) concluded that the contribution of tourism to global change is continuing to grow as a result of increasing tourist numbers, trip numbers and per trip distances, and increasing energy and water intensity of luxury tourism experiences and consumables.

A large body of literature examining the sociocultural impacts of tourism has also developed, but similarly has lacked global scale indicators. Jafari (Citation2001) outlined that sociocultural research within tourism advances arguments for both an advocacy platform, including the spread of cultural exchange and international peace and the appreciation and preservation of heritage and culture, and a controversy platform, which includes prostitution, increased crime, breakdowns in family structure, and the commercialization of arts, crafts and cultural traditions. This and other research is a reflection of the ‘cultural’ and ‘critical turn’ in tourism studies that has challenged conceptual and theoretical foundations of tourism research and emphasized the need to more critically engage with processes of globalization, capitalism and structural power (Bianchi, Citation2009). Consequently, contemporary studies often portray tourism and its sociocultural impacts at the destination as ambivalent (Sharpley & Telfer, Citation2014).

Measurable factors and associated social indicators that contribute to the social well-being and quality of life for host communities include economic security, employment, health, personal safety, housing conditions, physical environment and recreational opportunities (Hall & Lew, Citation2009). Many of these factors have been evaluated using the Human Development Index (HDI). Rutty et al. (Citation2015) found that the HDI improves for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) as the contribution of travel and tourism to national GDP and employment increases, suggesting that on a global scale, tourism can have positive socioeconomic impacts. Yet, climate change, with a growing contribution coming from tourism, is likely to jeopardize the livelihoods of potentially hundreds of millions of people who remain directly dependent on local ecosystem services, making it difficult to weigh socioeconomic advantages and disadvantages (Gössling, Hall, & Scott, Citation2009).

What major factors have stimulated and challenged the unprecedented growth and globalization of tourism over the past 40 years? A number of the most common and salient social, technological, economic, environmental and political factors contributing to increased travel across the globe are identified in , based on a review of recent publications discussing tourism futures.

Table 3. Major factors influencing tourism development.

Economic growth, initially concentrated in OECD nations, but then also in the emerging economies of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) nations and parts of the Middle East, has been fundamental to the expansion of tourism over the last 40 years. Dramatic acceleration in global economic growth occurred after World War II and by 1970 global GDP was estimated at $227 billion (constant 2005 US$). In 2010, global GDP had increased more than four-fold to nearly $1.1 trillion (World Bank, Citation2014). GDP remained highly concentrated in developed countries (>80%) until 1990, but diminished to approximately 60% by 2010, driving the rapid growth in tourism in the Asia and Pacific Region. The structural transformation of the global economy is anticipated to continue with the emerging economy share of global GDP anticipated to exceed 50% for the first time between 2015 and 2020 (World Bank, Citation2014).

While average personal incomes in developed countries and emerging economies have continued to increase over the past 40 years, according to the GINI coefficient (the most common measure income distribution of a nation) there has been a steady increase in global income inequality (0.65 in 1970 and 0.69 in 2010) as well as the income inequality of many individual nations (e.g. US: 0.39 in 1970 and 0.47 in 2010) (Milanovic, Citation2011). Nonetheless, greater prosperity among a larger population coupled with the introduction and expansion of paid (salaried) holidays for many workers in developed countries have been key social drivers of increased leisure travel. Combined statutory minimum employee holiday entitlement and public holidays exceeded 20 days in virtually all OECD nations in 2010, as well as the BRIC countries and several other developing countries (Mercer, Citation2014).

Improved transportation systems, including the massive expansion of highways and air travel networks, enabled significantly more travellers to reach a greater number of destinations. Reductions in the cost and increased speed of mobility created travel time-space compression that contributed to greater average travel distances for tourism (Hall, Citation2005). The expanding global transportation system available for domestic and international tourism was, with two exceptions, fuelled by low energy prices. World oil prices remained below US$ 40/barrel (in 2010 dollars) for 20 years, from the early 1980s until 2003 (BP, Citation2014). Substantially increased world oil prices in the 1970s and since 2005 (exceeding US$ 100 levels) influenced the costs of travel, but did not prevent continued growth in international tourism arrivals.

Evolving information and communication technology (ICT) systems have continued to revolutionize travel planning and marketing. The development of international payment systems and computerized reservation systems were the foundations for mass international tourism. The international tourism industry then went through a massive transformational change adapting to the widespread impact of the Internet in the 1990s and 2000s (Buhalis & Law, Citation2008). Internet technologies not only revolutionized travel planning and reservations but also the way tourism-related information was produced and distributed (Berne, Garcia-Gonzalez, & Mugica, Citation2012). It enabled tourism destinations and businesses to connect directly with consumers and for consumers to book their own travel reservations. The number of travel agents in the US declined from over 112, 000 in 2000 to just under 59,000 in 2010 (DePillis, Citation2013). Social media applications dramatically increased transparency in travel service quality and provided platforms for travellers to advise and influence their social networks and other travellers, substantially shifting the balance of power between customers and tourism providers.

A number of major political changes have diminished border travel restrictions, creating enormous new tourism opportunities in several regions of the world. The Schengen Agreement was signed in 1985 and now comprises 26 European countries that have abolished passport and any other type of border control at their common internal borders, allowing 400 million citizens to freely travel within its boundaries. Only a few years after the Schengen Agreement, the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1991 began the process of removing travel restrictions into and out of Western and Eastern Europe. It is estimated that less than 0.5% of the population of the USSR travelled abroad (Zhizhanova, Citation2011), but with the fall of the ‘iron curtain’ and a new freedom of travel, the number of outbound travellers from Russia exceeded 36 million in 2008, with a further 100 million from Poland, Hungary, Ukraine, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Latvia and Lithuania combined (based on data from United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2011). China was similarly closed to all but a selected few foreign visitors until the mid-1970s. In 1978, China received an estimated 230,000 international tourists (Lew, Citation1987), but as a result of political change, by 2010 China was one of the most visited countries with over 133 million international arrivals. Changes in China's outbound tourism policy also had major implications for international tourism. China's Approved Destination Status (ADS) policy was formalized in 1995 and allowed its citizens to take leisure trips abroad on group package tours to countries that have negotiated and implemented agreements with China (146 destination countries as of 2013). Over 57 million Chinese travelled abroad in 2010 and China is anticipated to become the largest outbound market by 2020 (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2011).

Tourism is a dynamic system and while the growth in international arrivals appears to be a smooth trend in , this growth trend has been punctuated by periods of stagnation or even reduced arrivals due to major disruptions from economic recession, pandemics, spikes in oil prices and terrorism. For example, international arrivals declined from 929 million in 2008 to 894 million in 2009 because of the economic crisis. Global airline RPK stagnated for three years in the aftermath of September 11, 2001 terror attacks on the US, and declined from 4400 billion to 4100 billion following the 2008–2009 economic crisis (Airbus, Citation2014). Regional scale disruptions have been even more significant, caused by natural disasters such as volcanic eruption (Iceland in 2010), tsunami (Southeast Asia in 2004 and Japan in 2011), and earthquakes, as well as armed conflict or political turmoil (e.g. Arab Spring).

Tourism futures towards 2050

If our retrospective view of the last 40 years of global tourism development has taught us anything, it is that planning for a ‘business as usual’ (BAU) future is a precarious strategy when the pace of technological, economic and environmental change is anticipated to continue to increase. The tumultuous events of the first decade of the twenty-first century, including the 2001 terrorist attacks on the US, the emergence of smart-phone technology and social media, the 2008 financial crisis and lingering economic recession, sovereign debt crisis in several nations, the Arab Spring movement, and the Asian and Japanese tsunamis, have further reinforced the importance of understanding and preparing for an uncertain and interconnected future. Although many of the principal drivers of tourism development from the past 40 years () will continue to be important influences of the next 40 years, tourism will encounter new opportunities and challenges that will shape its scope and scale at the global, regional and destination scales. Buckley, Gretzel, Scott, Weaver, and Becken (Citation2015) discuss in detail some of the ‘megatrends’ influencing the future of tourism.

What techniques do we have to provide insight into the near- and longer-term future of tourism? A wide range of forecasting techniques are available to assess well-established trends or influencing factors for which there is a reasonable understanding of, in order to provide seasonal, annual or multi-year investment and operational intelligence. For example, how cyclical economic conditions and currency exchange rates may influence seasonal visitation, or how demographic changes (population growth, ageing) and energy prices over the next 10 years could influence the evolution of specific tourism markets. Tourism forecasting began in the 1960s, with most early applications in Europe and North America (Goh & Law, Citation2002; Montgomery, Johnson, & Gardiner, Citation1990). Over the past 40 years, considerable progress in the development of scenarios has been made due to advances in analytical forecasting techniques. Today, trend extrapolation-based tourism forecasts are abundant, with most National Tourism Organizations or designated government departments providing extensive monthly, quarterly/seasonal and annual forecasts on domestic, inbound and outbound tourism trends. Multi-year forecasts are now available in many countries as part of tourism planning initiatives. Causal forecast models that examine relationships between the tourism performance indicator and other influencing factors are used to provide insight into changing tourism markets and their evolution in response to changes in various drivers, such as those listed in . Increasingly, contingency analysis is being applied in order to better reflect the uncertainty in multi-year forecasts. Instead of a single forecast of the future, contingency analysis examines how changes in key assumptions or influencing factors could alter outcomes and provide a range of future forecasts. For example, unlike the UNWTO's initial long-term forecast which provided a single forecast for global international tourist arrivals in 2020 (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2001), the more recent 2030 forecasts, included in , considered some varied assumptions of economic growth and transport costs (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2011). In this way, contingency analysis begins to take on some of the characteristics of scenarios-based planning.

Scenario techniques are available to explore the greater complexities and uncertainties of the more distant future, which institutional planning in business, government and non-governmental organizations generally does not handle well. Scenarios are not forecasts or predictions; they are alternate representations of plausible futures. In contrast to forecasts that focus on factors that contribute to transitionary change, scenarios-based planning is not based on extrapolating current trends and its explicit purpose is to constructively challenge the ‘business as usual’ assumptions inherent in the mental maps of organizations and key decision makers in order to uncover strategic blind spots that could create transformative change. Scenarios utilize broader perspectives to explore interactions among major known drivers of change to envision desired future states of a tourism business, destination or even the global tourism sector, and to identify the strategic implications of variously-called ‘game changers’, ‘black swans' or ‘x-factors' that could result in high-impact, non-linear changes. While scenario planning has had more limited application in the tourism sector to date, it could become increasingly valuable for navigating major future challenges (see ) as well as be used to develop a strategic vision for where tourism would like to be in the future.

What do these techniques tell us about the development trajectory and geography of global tourism over next 40 years? The World Travel and Tourism Council (Citation2014) provided 10-year projections for the economic contribution of the global tourism sector. The total contribution of tourism to global GDP has grown from an estimated US$ 5.5 trillion in 2003 to US$ 6.9 trillion in 2013 (9.5% GDP) and is further estimated to increase to 10.9 trillion by 2023 (10.3% GDP) (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2014). Similarly, the contribution of tourism to global employment is expected to increase from 265 million in 2013 (8.6%) to 345 million (9.8%) in 2023 (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2014).

The UNWTO (Citation2011) has developed 20-year projections of international tourist arrivals to provide insight into the sector's future role in the global economy, and they project an increase from 940 million in 2010 to 1.8 billion by 2030 (). Upper and lower forecasts for 2030 are between approximately 2 billion arrivals (‘real transport costs continue to fall’ scenario) and 1.4 billion arrivals (‘slower than expected economic recovery and future growth’ scenario) (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2011). Projections of global air travel are generally consistent with UNWTO's 2030 growth scenario, with the commercial aircraft fleet and RPK also projected to approximately double by 2030, from just over 21,300 aircraft and 4500 billion RPK in 2010 to approximately 40,000 aircraft and over 10,000 billion RPK in 2030 (Boeing, Citation2012). Extrapolating the growth rate from the end of the 2030s to 2050 when the global population is anticipated to begin to stabilize results in 2.9 billion international arrivals (with a range of 2.2 billion in the low economic growth scenario to 3.2 in the low mobility cost scenario). Modelling by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, Citation2012) produced similar estimates of 2.4–3.1 billion international arrivals in 2050 for green economy and BAU scenarios, respectively. Although the methodology is not articulated, Yeoman (Citation2012) provided another set of projections for the scale of international tourist arrivals in 2050. The low growth (1.6 billion international arrivals) and best-case (5.2 billion international arrivals) scenarios bracket the extrapolated UNWTO projections and represent the high and low projections in . Given the prospects of continued growth, many countries see tourism as one of their main future economic pillars, particularly in the perceived absence of other promising industrial sectors, as in the case of virtually all small island developing states (SIDS), or in countries where the extractive resource base is expected to be in decline over the next 40 years (e.g. Australia, Norway).

The geography of international tourism will continue to evolve, with the share of international arrivals to emerging economies surpassing those of advanced economies for the first time in approximately 2020 (United Nations World Tourism Organization, Citation2011; ), and the geographic centre of gravity will continue to shift as the market share in the Asia and Pacific and Middle East Regions continues to grow (to 30% and 8%, respectively, in 2030) at the expense of Europe and North America (). Given this projected regional growth pattern, international tourism is strongly promoted as an important element in development and poverty reduction in LDCs. The UNWTO (Citation2006, p. 1) outlines several reasons why tourism is an ‘especially suitable economic development sector for LDCs’. Similar positions are advocated by the World Travel and Tourism Council (Citation2003), the World Economic Forum (Citation2009), and several international development agencies (see Hall, Scott, & Gössling, Citation2013 for an overview). Interestingly, Yeoman's (Citation2012) regional growth projections for 2050 reveal contrasting outcomes for Africa and the Middle East, particularly under the low growth scenario where the market share of both regions declined relative to 2010 (). Notably, the UN has recently published a fundamentally revised estimate of global population growth until 2100, most of which is going to occur in Africa (Gerland et al., Citation2014). While the assumptions behind the Yeoman scenarios and how they influence regional tourism development are not explained, these outcomes may provide a note of caution for tourism as a development strategy in some countries and echo the recommendation of Hall et al. (Citation2013) and Vorster, Ungerer, and Volschenk (Citation2013) to better understand the conditions that could promote or hinder the purported long-term development of tourism in LDCs.

While the growth projections and broader work of the UNWTO and the WTTC have done much to promote the tourism growth agenda to the world's political and business leaders, neither have articulated how the projected doubling of international tourism by 2030 (and potentially tripling by 2050) might be accommodated sustainably. For example, how are these growth projections to be realized in a low carbon economy that achieves the more than 70% GHG emission reductions required to avert ‘dangerous’ climate change that would be an obstacle to achieving the very growth scenarios being promoted?

Indeed, sustainability outcomes associated with long-range tourism growth scenarios have received very limited and scientific scrutiny. For example, a tourism growth scenario based on the aforementioned sectoral projections and expected changes in travel frequency, length of stay, travel distance and technological efficiency gains, projected that CO2 emissions from tourism would grow by more than 135% by 2035 (compared with 2005 levels) (Scott et al., Citation2008; World Economic Forum, Citation2009). Similarly, water consumption by tourism is expected to double over the next 40 years, from an estimated current consumption of 138 km3 in 2010 to 265 km3 by 2050 in a ‘business as usual' scenario (Gössling & Peeters, Citation2015).

The United Nations Environment Programme-led Green Economy Initiative has explored long-term sustainability scenarios for the tourism sector. The United Nations Environment Programme (Citation2012) compared the outcomes of a BAU and two green investment scenarios (which assumed the annual allocation of 0.1% and 0.2% of global GDP or US$ 118 billion and US$ 248 billion – in constant 2010 US$ to support sustainable tourism development) for the tourism sector through to 2050. The two green economy scenarios resulted in total international tourist arrivals of 2.4–2.6 billion in 2050, which were 30–31% below the corresponding BAU scenarios due to the shift towards less frequent – but longer – trips in the green scenarios. The resulting economic contribution was estimated at US$ 9.3–10.2 trillion in 2050 (up from US$ 3 trillion in 2010) and direct employment was projected to grow to between 531–580 million. For both economic indicators the outcomes for the green investment scenarios were greater than in the BAU scenario and, importantly, despite the growing number of tourists, substantial reductions in resource consumption were also projected: water consumption reduced by 18–23%, CO2 emissions reduced by 31–52%. The United Nations Environment Programme (Citation2012) examined some of the enabling conditions that would be needed to achieve the more sustainable tourism futures, but did not examine the potential implications for regional economic development. Assumptions made for all scenarios are not articulated, although it needs to be assumed that massive policy interventions would be required to achieve such reductions in resource use.

Another interesting question that arises from these long-range forecasts and scenarios based on available trends and evidence is whether anything could conceivably challenge this central tenet of significant tourism growth for the next 40 years? While the United Nations Environment Programme (Citation2012) green growth and Yeoman's (Citation2012) low growth scenario for 2050 international arrivals represent limited growth from 2030 to 2050, none of the projections approximates a steady-state scenario as discussed by Hall (Citation2009). There are, of course, a number of ‘black-swan’ type scenarios that can be envisioned that could disrupt the assumed growth trajectory for tourism, including for example: a persistent virulent pandemic that makes international travel a personal risk and is highly regulated to prevent the spread of the biohazard or where airlines are held liable for the spread of the disease and become insolvent; a regional conflict in the Middle East that leaves oil production infrastructure highly damaged and causes a major and prolonged disruption of global oil supplies; a prolonged volcanic eruption in Iceland or Indonesia or elsewhere that interrupts aviation routes on a regional basis; abrupt climate change leads to unilateral climate engineering action by states, including the use of aircraft to distribute aerosols in international airspace; or an increasingly strict global GHG emissions regulatory framework and dwindling supply of carbon credits combined with the failure of a technological breakthrough on commercially scalable biofuels causes a substantial increase in the costs for aviation to achieve its ‘carbon neutral growth 2020’ commitment.

Wilkinson and Kupers (Citation2013) observed that a traditional trend-based BAU view of the future reflects the human tendency to comprehend familiar patterns and often results in an optimism bias that leaves the organization vulnerable to being blindsided by unexpected, disruptive events. Therefore, while the tourism sector cannot realistically be expected to anticipate and plan for low probability, massively disruptive ‘black swan’ events, it should be expected to plan for slower evolving trends that will have significant consequences for tourism, including: regional demographic change (ageing, population growth, increased urbanism), climate change and the requisite transition to a global low carbon economy, and near-term technological change (social media, mobile computing, the Internet of things, robotics in the service sector) (). While some innovative tourism focused scenario projects have explored some of these potential challenges (CSIRO Futures, Citation2013; Forum for the Future, Citation2009; Frost, Laing, & Beeton, Citation2014; Vorster et al., Citation2013; Yeoman, Citation2012), we contend here that tourism has much to gain from the expertise contained in the scenarios developed for other economic sectors.

Learning from non-tourism scenarios

As von Bergner and Lohmann (Citation2014, p. 420) indicate, ‘The existing tourism research does not fully address the nature of the global, intertwined challenges that may affect and shape the worldwide tourism system in the future with respect to both the industry and society’. Yeoman (Citation2012), as the self-proclaimed ‘only tourism futurist', is one of the few that assesses the tourism implications of the diverse future studies literature. There is tremendous expertise and insight available from risk analyses and scenarios developed for other sectors. Can tourism projections be reconciled with the future challenges identified by other sectors? Are there gaps in our thinking about the future enablers or consequences of tourism? What new technologies and social trends help overcome some of the challenges tourism is expected to face with respect to sustainability and human resources, or that might be presumed benefits of tourism development (e.g. pro-poor tourism)?

Scenario planning has enjoyed a revival of interest in the last decade as more organizations have integrated longer-term strategic planning in the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks on the US (Varum & Melo, Citation2010). Recent examples of scenario analyses for economic sectors and major global issues include: energy (e.g. International Energy Agency [IEA], Citation2011, Citation2012), demography (e.g. UN, Citation2012), economic development (e.g. International Monetary Fund, Citation2012), climate change (e.g. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2014), technology (e.g. Rockefeller Foundation, Citation2010), biodiversity and ecosystem change (e.g. Hassan, Scholes, & Neville, Citation2005; Leadley et al., Citation2010), transportation and mobility (e.g. Schäfer & Victor, Citation2000), agriculture and food production (e.g. Godfray et al., Citation2010) and water security (Cosgrove & Cosgrove, Citation2012).

The implications of these major exercises concerned with uncertain futures have rarely been interpreted for tourism and thus far represent a missed opportunity for the tourism community. Interpreting this large and diverse body of scholarship is beyond the scope of this paper, but two examples will be used to illustrate the insight that might be gained from greater engagement with available futures scholarship.

compares the 10 most prominent challenges facing the tourism sector in the next 20 years, as identified by Vorster et al.’s (Citation2013) recent Delphi analysis with tourism experts, with the 10 global risks of highest concern over the next 10-year horizon to the World Economic Forum's global panel, indicating considerable differences in perspectives. The limited scope of economic risks (i.e. steady-state economies or other challenges to neo-liberal economic growth projections) is a notable uncertainty on the tourism list of challenges given its prominence (i.e. fiscal crisis and systematic financial failure) for the global ‘shapers, agenda councils and young leaders’ that comprise the WEF sample. This risk has held the top position since the 2008–2009 economic crisis. The issues of high unemployment/under-employment on the list of global risks and human resource challenges for tourism are related, but the discussion is very different. The implications of continued automation in the service sector appear to be a blind spot for tourism, either for its potential to resolve human resource challenges or as a disruptive impact for the purported low-skill labour benefit of tourism development. A recent analysis of the potential impact of continued workplace automation concluded that as many as 45% of jobs in the US are vulnerable to computerization and robotics in the next 20 years, including an increasing number of service sector jobs (Frey & Osbourne, Citation2013). The prominence of environmental sustainability issues on both lists is a notable commonality, although each has slightly different emphases. The WEF panel identified regional to global risks related to water and food security, while the tourism panel identified destination scale issues (ecosystem conservation and local impacts management) and the need to incorporate sustainability in tourism management broadly. As Gössling et al. (Citation2015) concluded, while water is anticipated to become a more strategic, and in some regions more expensive, resource than oil in the twenty-first century (UN Water, Citation2014), and while there is a clear trend to further understand water risks for business, there is limited evidence that the tourism sector is considering future trends in water security and costs. That climate change appears on both lists is also notable, considering tourism has not been represented in a meaningful way in the annual UN Climate Conference since 2009. The need for greater contingency planning to disruptive events by tourism is encouraging and consistent with the trend towards contingency and scenario planning by governments and business noted previously.

Table 4. A comparison of the most important challenges over the next 10–20 years.

As indicated, there is a wide range of future forecasts and scenario research available for economic sectors, countries/regions and major global challenges. Some of these sectors and grand challenges are more relevant to the tourism sector than others. Because tourism is predicated on mobility, energy futures are among the most salient, and the issue we have selected to explore in more detail. While oil price and concerns over ‘peak oil’ are relevant to tourism, the principal near-term driver of the transformation of the global energy system is the need to reduce global GHG emissions to avoid ‘dangerous climate change’ (as defined by the international community). In late 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Synthesis Report (Citation2014) included a revolutionary recommendation to policy makers that net CO2 emissions need to decrease to zero if the policy of the international community to avoid dangerous global climate change is to be achieved. The IPCC has made the scientific case for a total phase out of CO2 emissions, not just a certain percentage reduction by a certain year. Angel Gurria (Citation2014), Secretary-General of the OECD, challenged governments, ‘ … to put us on a pathway to achieve zero net emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels in the second half of this century'. Knowing that GHG emissions need to get to zero means that from now on we must ask a question of any long-term infrastructure investment or proposed development: will it put the country/industry on track to achieve net zero emissions by the 2050s or shortly thereafter? In practice, phasing out CO2 emissions means that the tourism sector will need to plan for (and largely implement) a future powered by 100% renewable energy within the next 40 years. How is this transformative change to be reconciled with the tremendous growth anticipated in tourism?

A number of global energy scenarios have been developed to achieve what is referred to as ‘deep decarbonization’ of the global economy. The GHG emissions reduction strategies put forward by various organizations differ substantially with regard to how such transformative change in the global energy system can be accomplished, with attendant differential implications for tourism. For example, as part of its comprehensive assessment of current and future energy needs and the evolution of the global energy system for the 29 member countries that support it, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has developed scenarios of emission trajectory associated with BAU energy development (a +4°C or +6°C world) and how international climate policy objectives (+2°C world) could be achieved. The IEA utilizes all available technologies for emissions reduction, including increased use of nuclear and carbon capture and storage technologies to decarbonize the electrical grid. The transportation sector focused report (International Energy Agency [IEA], Citation2009) projected that air passenger kilometres increase by a factor of four between 2005 and 2050 in the Baseline scenario, and by a factor of five in the High Baseline scenario, with more than half of the growth in non-OECD countries. These are consistent with Boeing and Airbus growth projections outlined earlier. In their Blue Map/Shifts scenario, 30% of aircraft fuel is second-generation biofuel by 2050, but in order to achieve required emission reductions air travel is reduced from the BAU scenarios by 25% through strong policies to dampen its growth, including major investments in high-speed rail, fuel pricing and improvements in telecommunications that prompt changes in travel patterns (i.e. a strong trend towards video-conferencing instead of face-to-face meetings). Under this low carbon transport scenario, RPK reach 11,500 billion in 2050, slightly less than a tripling from 2010 and only 15% greater than the projections of Airbus and Boeing for 2030 (approximately 10,000 billion). With the UNWTO central estimate of 2.9 billion international arrivals in 2050, the average RPK per arrival would be 3900, which is 30% less than the average distance travelled by international tourists in 2010. The implications for long-haul dependent destinations are clear.

Deng, Blok, and van der Leun (Citation2012) provided an alternate energy future, one that has phased out fossil fuels and consists of entirely renewable energy sources by 2050. In this scenario, ground based transportation is extensively electrified and a massive scale-up of biofuels is used as the fossil fuel replacement where liquid fuels are required. Because of the expected challenges of massive biofuel deployment, this scenario explicitly limits growth in areas that depend on liquid fuels – notably aviation, shipping and heavy goods vehicles – until secure and sustainable supplies of bioenergy have been established. This reverses the onus on industries promising biofuels-based emission reductions (such as the IATA commitment to 50% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2050) to demonstrate proof of a scalable technology that does not compete with land use for food production before growth takes place. Similarly of relevance to tourism, the scenario assumes substantial modal shifts away from ‘inefficient individual road and aviation modes’ to rail and shared road modes and a 33% cut in passenger air travel over projected BAU growth. These reductions in air travel are accomplished through video conferencing and emerging innovative technologies that reduce the need for business travel and people choosing to travel more slowly, or holiday closer to home.

While these two scenarios are offered as examples, it is important to note that the authors have not been able to find any energy future scenario that achieves the climate change goals of the international community and includes the projected growth in air travel that is central to tourism growth scenarios (see Dubois, Ceron, Peeters, & Gössling, Citation2011). Furthermore, while the implications of this transformation of the global energy system seems decades into the future, it is the long-range requirement to fully decarbonize the electrical grid and transportation that MacDonald and Cao's (Citation2014) described as an impetus for their scenario of a ‘sudden rise of carbon taxes’ over the next 10–15 years, suggesting the implications for travel costs may not be decades away.

These and other competing visions for global low/no carbon energy systems are developed to influence policy makers, including leading up to the key climate change negotiations in Paris in 2015 that will establish the near term international emission reduction policy framework. Which of these energy futures is most compatible with the tourism futures envisioned by UNWTO and WTTC? The answer is that while the tourism sector has declared ‘aspirational’ GHG emission reduction targets (-25% by 2020 and -50% by 2035 – from the 2005 baseline), its lacks a coherent plan to achieve anything close to these emission reductions (Gössling, Scott, & Hall, Citation2013; Scott, Peeters, & Gössling, Citation2010) and does not have a position on these or other proposed global energy futures. In its assessment of the future of the global energy system for 2050, Shell International (Citation2008, p. 6) emphasized that, ‘(a) question that should be on the mind of every responsible leader in government, business and civil society’ … is … ‘How can I prepare for, or even shape, the dramatic developments in the global energy system that will emerge in the coming years?’ Conversely, the tourism sector has not yet completed an assessment of what ‘deep decarbonization’ would mean for the long-term prospects for regional tourism development, including long-haul destinations (which include many SIDS and LDC countries), regions with extensive rail connections, or for the economies of fossil fuel exporting nations and tourism growth scenarios predicated on associated economic growth of these regions (e.g. the Middle East tourism region).

Conclusions

If you don't know where you're going, any road will get you there.

As we look back at the first 40 years of TRR, international tourism has grown to become a global force of economic, social and environmental significance. Over the next 40 years, tourism is anticipated to continue to double or even triple in the number of travellers and economic contribution. While sustainability is expected to be an imperative in this period, the implications of such a massive expansion of tourism are not well understood.

As the global tourism system is affected by, and must respond to, an increasing number of interconnected challenges, including on-going uncertainty related to the financial and sovereign debt crisis, the new geography and market preferences of major tourist flows from emerging economies, the new realities of mobility in a world of fluctuating energy prices and the shift towards a low-carbon economy, threats of terrorism and political upheaval, demographic change with near and long-term implications for travel patterns of youth and seniors, and the consequences of climate and environmental change for destination attributes and attractiveness, the need for techniques that can contribute to future preparedness will only increase. This paper concludes that the diverse scenarios exercises completed for other sectors, including energy, economic development, climate change, technology, biodiversity and ecosystem change, transportation and mobility, agriculture and food production and water security, of global grand challenges have rarely been interpreted for tourism and thus far represents a missed opportunity for the tourism community concerned with planning for an uncertain future.

As we collectively look forward to the next 40 years of TRR, we need to ask some important questions about the future of tourism. Which of the megatrends and major challenges to regional or global tourism listed in and has the tourism sector evaluated? How vulnerable are the UNWTO projections of tourism growth to 2030 and beyond to these unfolding trends or disruptive events? In other words, what future(s) is tourism ready for? The answers to these questions are disconcerting, considering the increasing important contribution many perceive tourism will make to the future global economy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributors

Stefan Gössling is a professor at Linnaeus and Lund universities, Sweden, and a research coordinator at the Western Norway Research Institute. He is interested in all sustainability aspects of tourism and transport.

Daniel Scott is a University Research Chair in Global Change and Tourism at the University of Waterloo in Canada and a Research Fellow at the Western Norway Research Institute. His research interests centre on the interface of global change and sustainable tourism.

References

- Airbus. (2014). Global market forecast for 2014–2033. Retrieved from http://www.airbus.com/company/market/forecast/

- Anseeuw, W., Wily, L. A., Cotula, L., & Taylor, M. (2012). Land rights and the rush for land: Findings of the global commercial pressures on land research project. Rome, Italy: The International Land Coalition.

- Berne, C., Garcia-Gonzalez, M., & Mugica, J. (2012). How ICT shifts the power balance of tourism distribution channels. Tourism Management, 33(1), 205–214.

- Bianchi, R. V. (2009). The ‘Critical Turn’ in tourism studies: A radical critique. Tourism Geographies, 11(4), 484–504.

- Boeing. (2012). 2013 and realignment of aircraft finance. Retrieved from http://www.capetowntreatyforum.com/presentations/Realignment_of_Aircraft_Finance.pdf

- Boeing. (2014). Current market outlook 2014–2033. Retrieved from http://www.boeing.com/assets/pdf/commercial/cmo/pdf/Boeing_Current_Market_Outlook_2014.pdf

- BP. (2014). Annual BP statistical review of world energy. Retrieved from http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/about-bp/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (1993). Sustainable tourism: an evolving global approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(1), 1–5.

- Buckley, R., Gretzel, U., Scott, D., Weaver, D., & Becken, S. (2015). Tourism Megatrends. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(1), 59–70.

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 yearsafter the Internet—The state of eTourism research. TourismManagement, 29(4), 609–623.

- Cazcarro, I., Hoekstra, A. Y., & SánchezChóliz, J. (2014). The waterfootprint of tourism in Spain. TourismManagement, 40(1), 90–101.

- China National Tourism Administration. (2012). Domestic tourism statistics developments in China. Retrieved from http://dtxtq4w60xqpw.cloudfront.net/sites/all/files/pdf/rs_china_domestic.pdf

- Cooper, C., & Hall, C. M. (2013). Contemporary tourism: An international approach (2nd ed.). Oxford: Goodfellow.

- Cosgrove, C. E., & Cosgrove, W. J. (2012). The dynamics of global water futures driving forces 2011–2050. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002153/215377e.pdf

- CSIRO Futures. (2013). The future of tourism in Queensland. Retrieved from http://www.csiro.au/Portals/Partner/Futures/Future-of-Tourism-in-QLD.aspx

- Deloitte. (2010). Hospitality 2015-game changers or spectators? Retrieved from https://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-Uruguay/Local%20Assets/Documents/Industrias/Uy_Hospitality_2015.pdf

- Deng, Y., Blok, K., & van der Leun, K. (2012). Transition to a fully sustainable global energy system. Energy Strategy Reviews, 1(2), 109–121.

- DePillis, L. (2013). Travel agents: We do exist!. The Washington Post, 30 August. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/08/30/travel-agents-we-do-exist/

- Dubois, G., Ceron, J.-P., Peeters, P., & Gössling, S. (2011). The future tourism mobility of the world population: Emission growth versus climate policy. Transportation Research Part A, 45, 1031–1042.

- Forum for the Future. (2009). Tourism 2023. Retrieved from https://www.forumforthefuture.org/sites/default/files/project/downloads/tourism2023fullreportwebversion.pdf

- Frey, C., & Osbourne, M. (2013). The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerization? Oxford, UK: Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf

- Frost, W., Laing, J., & Beeton, S. (2014). The future of nature-based tourism in the Asia-Pacific region. Journal of Travel Research. doi:10.1177/0047287513517421

- Gerland, P., Raftery, A. E., Sevcikova, H., Li, N., Gu, D., Spoorenberg, T., … Wilmoth, J. (2014). World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science, online 18 September 2014. doi:10.1126/science.1257469

- Godfray, H. C. J., Beddington, J. R., Crute, I. R., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Muir, J. F., … Toulmin, C. (2010). Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science, 327(5967), 812–818.

- Goh, C., & Law, R. (2002). Modeling and forecasting tourism demand for arrivals with stochasticnon stationary seasonality and intervention. Tourism Management, 23(5), 499–510.

- Gössling, S. (2002). Global environmental consequences of tourism. Global Environmental Change, 12, 283–302.

- Gössling, S., Garrod, B., Aall, C., Hille, J., & Peeters, P. (2011). Food management in tourism: Reducing tourism's carbon ‘foodprint’. Tourism Management, 32(3), 534–543.

- Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., & Scott, D. (2009). The challenges of tourism as a development strategy in an era of global climate change. In E. Palosuo (Ed.), Rethinking development in a carbon-constrained world. Development cooperation and climate change (pp. 100–119). Finland: Helsinki: Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., & Scott, D. (2015). Tourism and water. Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications.

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism's global environmental impact 1900–2050. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1008500

- Gössling, S., Peeters, P., Hall, C. M., Dubois, G., Ceron, J. P., Lehmann, L., & Scott, D. (2012). Tourism and water use: supply, demand, and security. An International Review. Tourism Management, 33(1), 1–15.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2013). Challenges of tourism in a low-carbon economy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 4(6), 525–538.

- Government of India (2011). Indian tourism statistics. Retrieved from http://tourism.gov.in/writereaddata/CMSPagePicture/file/Primary%20Content/MR/pub-OR-statistics/2010Statistics.pdf

- Gurria, A. (2014). A call for zero net emissions. Retrieved from http://oecdinsights.org/2014/01/24/a-call-for-zero-emissions/

- Gyr, U. (2010). The history of tourism: Structures on the path to modernity. Retrieved from http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/the-history-of-tourism

- Hall, C. M. (2005). Tourism: Rethinking the social science of mobility. London: Pearson Education.

- Hall, C. M. (2009). Degrowing tourism: décroissance, sustainable consumption and steady-state tourism. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 20(1), 46–61.

- Hall, C. M., & Lew, A. (2009). Understanding and managing tourism impacts: An integrated approach. London: Routledge.

- Hall, C. M., & Page, S. (2006). The geography of tourism and recreation: Place, space and environment (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Hall, M. C., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2013). The primacy of climate change for sustainable international tourism. Special Issue: Critical Perspectives on Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development, 21, 112–121.

- Hamilton, J., Maddison, D., & Tol, R. (2005). Climate change and international tourism: A simulationstudy. Global Environmental Change, 15, 253–266.

- Hassan, I., Scholes, R., & Neville, A. (Eds). (2005). Millennium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: Current state and trends: Findings of the condition and trends working group. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- International Energy Agency. (2009). Transport, energy and CO2: moving toward sustainability. Retrieved from http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/transport2009.pdf

- International Energy Agency. (2011). World energy outlook 2011. Paris: Author. Retrieved from www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/WEO2011_WEB.pdf.

- International Energy Agency. (2012). World energy outlook 2012. Paris: Author. Retrieved from http://www.iea.org/newsroomandevents/speeches/weo_launch.pdf

- International Monetary Fund. (2012). World economic outlook April 2012: Growth resuming, dangers remain. Washington, DC: Author.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2013). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis – Summary for Policy Makers. The Working Group I (WGI) contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Retrieved from http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/uploads/WGIAR5-SPM_Approved27Sep2013.pdf

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2014). Fifth assessment synthesis report, summary for policy makers. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/SYR_AR5_SPM.pdf

- Jafari, J. (2001). The scientification of tourism. In V. L. Smith & M. Brent (Eds.), Hosts and guests revisited: Tourism issues of the 21st century (pp. 28–41). New York: Cognizant Communication.

- King, M. (2013). Brazil's domestic tourism market reached a value of $130 billion during 2011. Retrieved from https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/brazils-domestic-tourism-market-reached-000000953.html

- Leadley, P. H. M., Pereira, R., Alkemade, J. F., Fernandez-Manjarrés, V., Proença, J. P. W., Scharlemann, M. J., & Walpole, M. J. (2010). Biodiversity scenarios: Projections of 21st century change in biodiversity and associated ecosystem services. Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.diversitas-international.org/activities/research/biodiscovery/cbdts50en.pdf

- Lew, A. A. (1987). The history, policies and social impact of international tourism in the people's republic of China. Asian Profile, 15(2), 117–128.

- Löfgren, O. (2002). On holiday. A history of vacationing. Oakland: University of California Press.

- MacDonald, L., & Cao, J. (2014). The sudden rise of carbon taxes, 2010–2030. Retrieved from http://www.cgdev.org/publication/sudden-rise-carbon-taxes

- Mathieson, A. R., & Wall, G. (1982). Tourism: Economic, physical and social impacts. Harlow: Longman.

- Mercer. (2014). Holiday entitlements – global comparison. Retrieved from http://www.totallyexpat.memberlodge.com/resources/Documents/Mercer_Holidayentitlements_Globalcomparisontable.pdf

- Milanovic, B. (2011). More or less. Finance & Development, 48(3). Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2011/09/milanovic.htm

- Montgomery, D. C., Johnson, L. A., & Gardiner, J. S. (1990). Forecasting and time series analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies.

- Page, S. (2003). Tourism management: managing for change. Oxford: Butterworth- Heinemann.

- Rockefeller Foundation. (2010). Scenarios for the future of technology and international development. New York: Author. Retrieved from http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/news/publications/scenarios-future-technology

- Rutty, M., Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2015). The global effects and impacts of tourism: An overview. In C. M. Hall, S. Gössling, & D. Scott (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and sustainability (pp. 36–63). London: Routledge.

- Schäfer, A., & Victor, D. G. (2000). The future mobility of the world population. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 34(3), 171–205.

- Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2015). Tourism in the future(s): Forecasting and scenarios. In C. M. Hall, S. Gössling, & D. Scott (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and sustainability (pp. 305–319). London: Routledge.

- Scott, D., Amelung, B., Becken, S., Ceron, J.-P., Dubois, G., Gössling, S., … Simpson, M. (2008). Climate change and tourism: responding to global challenges. Madrid: UNWTO.

- Scott, D., Peeters, P., & Gössling, S. (2010). Can tourism deliver its ‘aspirational’ greenhouse gas emission reduction targets?. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18, 393–408.

- Sharpley, R., & Telfer, D. J. (2014). Tourism and development. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Shell International. (2008). Shell energy scenarios to 2050. Retrieved from http://www.shell.com/content/dam/shell/static/public/downloads/brochures/corporate-pkg/scenarios/shell-energy-scenarios2050.pdf

- Shifflet, D. K., & Associates, Ltd., & IHS Global Insight. (2008). Economic headwinds will slow 2008 U.S. Domestic Travel to 1.99 billion person-trips. Waltham, USA: MclLean.

- UN. (2012). United Nations Population Division Home Page, various pages. Retrieved from:www.un.org/esa/population

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2010). The contribution of tourism to trade and development, note by the UNCTAD secretariat TD/B/C.I/8. Geneva: Author.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2013). A new global partnership: Eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development. Retrieved from: http://www.post2015hlp.org/featured/high-level-panel-releases-recommendations-for-worlds-next-development-agenda/

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2012). Tourism in the green economy – Background report. Retrieved from http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/88/documents/ger/ger_final_dec_2011/Tourism%20in%20the%20green_economy%20unwto_unep.pdf

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2001). Tourism 2020 vision. Madrid: Author.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2006). Report of the World Tourism Organization to the United Nations Secretary-General in Prep- aration for the High Level Meeting on the Mid-Term Comprehensive Global Review of the Programme of Action for the Least Developed Countries for the Decade 2001–2010. UNWTO: Madrid.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2011). Tourism Towards 2030: Global Overview. UNWTO General Assembly, 19th session.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2012). Compendium of tourism statistics 1995–2010. Madrid: Author.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2014). UNWTO tourism highlights 2014 edition. Madrid: Author.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization & United Nations Environmental Programme. (2011). Tourism: investing in the green economy. In Towards a Green Economy (pp. 409–447). UNEP: Geneva.

- UN-Water. (2014). Water and energy. The United Nations World water development report 2014. Retrieved from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002257/225741E.pdf

- Varum, C. A., & Melo, C. (2010). Directions in scenario planning literature–A reviewof the past decades. Futures, 42(4), 355–369.

- von Bergner, N. M., & Lohmann, M. (2014). Future challenges for global tourism: A Delphi survey. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 420–432.

- Vorster, S., Ungerer, M., & Volschenk, J. (2013). 2050 Scenarios for Long-Haul Tourism in the Evolving Global Climate Change Regime. Sustainability, 5(1), 1–51.

- Weaver, D., & Lawton, L. (2006). Tourism management. Singapore: John Wiley and Sons.

- Wilkinson, A. & Kupers, R. (2013). Living in the futures. Harvard Business Review, May 2013. Retrieved from http://hbr.org/2013/05/living-in-the-futures/ar/1

- World Bank. (2014). GDP per capita. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD/countries

- World Economic Forum. (2009). Towards a low carbon travel and tourism sector. Davos, Switzerland: Author.

- World Economic Forum. (2014). Global risks 2014. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalRisks_Report_2014.pdf

- World Travel and Tourism Council. (2003). Blueprint for new tourism. WTTC: London.

- World Travel and Tourism Council. (2014). Travel and tourism economic impact 2014-World. Retrieved from: http://www.wttc.org/focus/research-for-action/economic-impact-analysis/

- Yeoman, I. (2012). 2050 – Tomorrow's tourism. Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications.

- Zhizhanova, Y. (2011). Tourism in the USSR in the second half of the 20th century.9th annual conference of the international association for the history of transport, traffic and mobility. Berlin. Retrieved from http://t2m.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Zhizhanova_Yuliya_Paper.pdf