ABSTRACT

Kazakhstan is the location of some of the most important Gulag heritage from the Soviet period of domination. However, commemoration, conservation and interpretation of Gulag sites is at best partial, visitation low and the attitude to this element of Kazakh history is ambiguous. This paper considers key heritage sites and museums in Kazakhstan and a qualitative case study approach is adopted based on a combination of interviews with twenty-four key stakeholders involved in the development and operation of Gulag tourism. Direct observations and qualitative document analysis of the major national Gulag museums and other important Gulag heritage sites was also undertaken. This research questions the orthodoxy inherent in the supposed attraction of dark tourism sites and seeks to ascertain why domestic and international visitation remains low given the scale and importance of the Gulag narrative.

Introduction

Kazakhstan is the location of some of the most important GulagFootnote1 sites of the Soviet period of domination. The Gulag originated following the chaos of the Russian Revolution and became the primary method of enforcing the punitive and repressive forces of the Soviet state (Ivanova, Citation2000). These camps were used to imprison, isolate and oppress political opponents, and incarcerating prisoners of war, as well as serving as part of the Soviet penal system. The use of the Gulag system of forced labour for industrial production and oppression intensified under Stalin (Khlevniuk, Citation2004) and Gulag camps were located throughout much of the former USSR (see ). The penal aspects of the Gulag remained in operation after the death of Stalin and the use of forced labour continued until final closure by former President Gorbachev in 1987. The treatment of Gulag heritage in Kazakhstan forms the basis of this paper which considers issues of dilution, ambiguity and selectivity in Kazakh narratives of the period.

Figure 1. Gulag Network in Former USSR (Memorial, Citation2001).

The literature on Gulag heritage and commemoration in both Russia and other former Soviet Republics has increased in recent years. Bogumil (Citation2018), offers analysis of selected Gulag sites considering their contested and complex commemoration and the relationship with Russian nationalism. Norris (Citation2020), considers the range of formats and nature of interpretation in Central and Eastern European nation museums and heritage sites. Indeed, Barnes (Citation2020) adds to the consideration of Kazakhstan focussing on the Alzhir and Karlag sites also considered in this paper. The Gulag was an important element of the Soviet economy and constituted a supply of forced labour in a range of sectors. Yet, often on completion of tasks, Gulag camps would be abandoned to deteriorate, leaving little evidence of their existence (Gessen & Friedman, Citation2018). In Kazakhstan, two major museums of the Gulag exist, both located on sites of former camps. These institutions were created with Central Government funding for construction and operation and in the case of the Alzhir Museum, then President; Nursultan Nazarbayev, opened the site in 2007 and his audio narrative is available on entry. However, other built heritage conservation of this period is limited and interpretation is sometimes ambiguous. Since independence in 1991, Kazakhstan has adopted a stabilising and unifying ideology of civic nationhood wherein memories of Soviet oppression are framed in variable but politically popular narratives (Adams & Rustemova, Citation2009). The loss of life in the Soviet Gulag system is a central part of understanding this shared dark past of what has been referred to as ‘the century of the camps’ (Toker, Citation2019). For some, the camps are important evidential heritage which can be diluted by selective consideration. Literally, they are:

… material facts of our time (but) this will not be meaningful unless we can bring the dead into existential focus (Elliot, Citation1972, p. 6)

In Kazakhstan, Gulag heritage and museums are characterised by low visitation and limited commemoration. The location of both major Gulag museums does not make access straightforward, particularly by public transport. Alzhir museum located 40 kms. outside of the relocated and architect planned capital; Nur-Sultan (formerly Astana) is illustrative. Similarly, the relatively recent opening of these museums; Alzhir (opened in 2007) and Karlag (opened in 2005) intimated relatively recent levels of political interest in this heritage. Interpretation in both cases whilst identifying the Gulag as an instrument of oppression of the Kazakh nation is less definitive on political and criminal responsibilities. Some identify this phenomenon as a renegotiation of history with permitted tourism elements forming part of the preferred exhibition of the nation state (Sant-Cassia, Citation1999). Memory and the relationship to tourism is linked with heritage (Marschall, Citation2012) and Gulag heritage constitutes evidence of a past that can influence collective memory. As Arendt (Citation1973), noted in the cases of Nazi and Soviet camps; the anonymity of death and the lack of narrative makes the loss hard to record or interpret.

… by making death itself anonymous (making it impossible to find out whether a prisoner is dead or alive) robbed death of its meaning as the end of a fulfilled life. In a sense that took away the individual's own death, providing that henceforth nothing belonged to him and he belonged to no one. (Arendt, Citation1973, p. 452)

Photographic imagery and literary coverage also play a role in both perceptions and destination awareness (Hunter, Citation2008) and the current circulation of imagery captured on digital devices provides a record of both visitation and ‘experience’. Arguably, in the case of the Gulag, imagery and literary consideration is more limited. The Gulag has of course famously featured in some literature and film, notable examples include; Solzhenitsyn (Citation1963, Citation1986), Rawiez (1956) and Theroux (Citation2009). Gulag imagery is similarly limited in tourism marketing materials for such sites in Kazakhstan. Indeed, even the most basic visual infrastructure, such as signage and visitor information is scarce. Interestingly, the Gulag Museums examined in this paper have few directional signs and limited paper or electronic marketing as visitor ‘attractions’. In other nations; such as Rwanda, such dissonant heritage has been controversially used as a key marketing element of the tourism offer (Friedrich & Johnston, Citation2013). In the USA and Australia, battlefields are developed visitor attractions and aspects of the tourism offer, even though in some cases omission of indigenous narratives has occurred (Harvey Lemelin et al., Citation2013). Herein, such selective interpretation of history has been challenged by collaborative management approaches to the difficult past, seeking to provide more transparent and measured approaches to such history. Despite this, the appeal of such sites to visitors is evidenced globally and in many locations appropriate marketing and signage is employed to this end. Hartmann (Citation2014), has highlighted this continued interest in the shadowed past and the geography of memory in generating conflicting responses amongst visitors. For some, making dissonant heritage visible resides in an enlightened perspective on the power of such visibility to catalyse concern (Poria et al., Citation2006). Such perspectives optimistically anticipate that such dark attractions will communicate learning and generate condemnatory actions (Torchin, Citation2012); although as history has illustrated, this is not necessarily the case. Tourism marketing materials normally highlight elements attractive to visitors creating positive perceptions (Dann, Citation1996); thus, it is perhaps understandable that Kazakh Gulag visual and linguistic narratives are partially absent. Just a single tour operator: Nomadic Travel, in Kazakhstan offered elements of Gulag history as a small part of their ‘Back to the USSR’ package (Nomadic Travel, Citation2020). Yet, such dark heritage undoubtedly has generated appeal to consumers globally and ‘dark marketing’ of sites has been identified as a phenomena (Brown et al., Citation2012). Indeed, in the case of Northern Ireland, the appeal of conflict heritage has evidenced enduring interest (McDowell, Citation2008, Citation2009; Neill, Citation2017). Similarly, the difficult and dark heritage of destinations ranging from Cambodia to the nations of the former Yugoslavia have continued to generate interest and visitation (Lennon, Citation2009; Rivera, Citation2008). However, the national focus for much of Kazakhstan historical narrative since independence in 1991, has been nationhood and the achievements since independence, see for example Ospanova (Citation2020). In contrast, the Soviet colonial period receives limited coverage in tourism, museums or secondary school curriculum. Interpretation of the famines that followed forced collectivisation is limited, statistics on victims and incarceration are less than exhaustive and identification of perpetrators in Kazakhstan remained absent (see for example: Turlygul et al., Citation2015; Uskembayev et al., Citation2019). Yet, the presence of state funded Gulag museums contradicts any hypothesis of simply the covering of such dark history (Rivera, Citation2008). These museums exist and welcome visitors. They provide web resources and have clear educational missions. The narrative is neither covered nor overlooked but occupies a diluted and unclear position in respect of this part of Kazakh history. Fentress and Wickham (Citation1994) have argued that each generation creates social memories of the past through the selection and interpretation of data, relevant heritage, memorials, and museums. People assemble a collective perspective of the past (Winter, Citation2009) and if evidential heritage is only partially interpreted or conserved then understanding and appreciation may well be impacted.

Dark tourism and Gulag heritage

Death, suffering, and tourism have generated analogous academic research in this area and consideration of work on; selective interpretation (Lennon, Citation2009; Wight & and Lennon, Citation2007); criminal omission (Botterill & Jones, Citation2010) and dissonant heritage (Ashworth, Citation1996; Tunbridge & Ashworth, Citation1996), has merit in this context. War, genocide and death can operate as both a deterrent to visiting destinations, but also as motivation for visitation. Government responses to commemoration and commercial development of ‘dark’ sites varies and the ambiguity of Kazakhstan Gulag heritage is not unique. However, the scale of the Gulag narrative suggests the relationship between heritage and memory is significant. Memory as a reconstruction of the past is invariably based on the present (Halbwachs, Citation1992). Where interpretation is limited and awareness and access to sites is both difficult and expensive, then the influence and awareness can be diluted. MacCannell’s (Citation1989) system of tourist attractions as signs, sites (designated as signifiers) and tourists (designated as interpretants) is challenged. Experience and discourse provide objects with their past, present and future. Seremetakis (Citation1994), reaffirmed this centrality of heritage to memory; buildings and artefacts connect individuals with their historic pasts. However, the commemoration of the Gulag is contested and politicised in many parts of the former USSR (Slade, Citation2017; Trochev, Citation2018) and such sites can be used to legitimise past and current political ideologies (Pearce, Citation1992). Yet, these sites are related to shared and traumatic history and sometimes perceived as ‘authentic’ representations of the past by visitors (Chhabra, Citation2008; Pearce, Citation1992; Piché & Walby, Citation2010). Indeed, such sites of death and incarceration have catalysed visitors for generations (Strange & Kempa, Citation2003) with education frequently cited to defend development and visitation (Lennon & Foley, Citation2000; Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009). In the Gulag context, selective interpretation and partial omission is evident (Lloyd, Citation2007), despite the fact that over 1.3 million people were deported to Kazakhstan during the USSR period (Barnes, Citation2011; Trochev, Citation2018) and the Kazakh Gulag footprint is evident in; infrastructure, heritage and mass graves.

Methodology of this study

This pilot study investigated Kazakhstani Gulag sites through interviews with 24 key stakeholders and analysis of key sites. Content, interpretation and conservation was considered at museums and heritage sites in 2018. The research constituted a qualitative case study methodology and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders (listed in ) were combined with document analysis. A constructivist paradigm for review of interpretation and heritage narratives was employed. Such a case study approach can encompass numerous data collection method which includes considering stakeholders’ perceptions through interview analysis (Yin, Citation2003). Conservation and maintenance elements were also reviewed and museums and heritage sites were selected through purposive sampling. Stakeholder interviews were undertaken in parallel with key site evaluation throughout 2018.

Table 1. Identification of stakeholders interviewed.

Interviews were digitally recorded in Kazakh or Russian, translated, transcribed and subject to content analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Analysis of documents, books, visual materials was also undertaken and fieldwork notes of direct observations of museums contrasted with interview transcripts.

Kazakh museums and Gulag heritage

For locals these are not the best places to go

Tour Operator, Nur-Sultan.

The two major national museums that provide primary consideration of Gulag history in Kazakhstan were both considered. They are introduced below and accompanied by evaluation of other Gulag heritage sites.

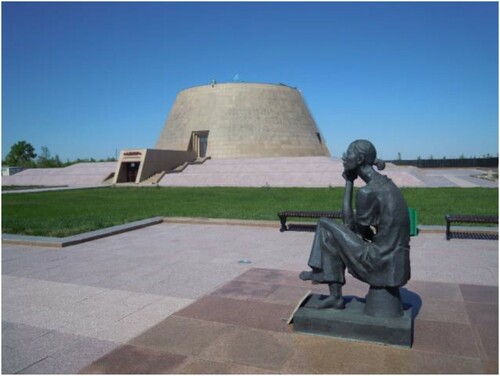

Museum 1: Alzhir museum, Nur-Sultan (www.museum-alzhir.kz/en/)

The Soviet prison and forced labour camp; ‘Alzhir’, (Akmolinsk Camp for Wives of Traitors to the Motherland), is located 30 km south of Nur-Sultan () and was a subdivision of the wider Karlag system. It was an incarceration site for females and children containing over 18,000 women of 62 nationalities and ethnic groups (Alzhir Museum, Citation2018). These women originated predominantly from: Russia, Ukraine, Belorussia, Georgia, Armenia and Central Asia and included scientists, musicians and artists.

This contemporary architect designed museum complex is built on the site of the former Gulag orchard. It was opened in 2007 and it incorporates reconstructed; prison barracks, cells, torture locations and tableaux, following the loss of most of the original structures. This museum focuses on Kazakh history and the domination of Kazakh nationals initially as part of the Russian Empire and later, the USSR. The transformation of nomadic life through collectivisation and the destruction of the Khans is featured and interpretation of resistance to colonial and later Soviet oppression is considered. This is primarily focussed around male narratives and the consideration of the females and children imprisoned at Alzhir is eclipsed. It has been argued that the Kazakh commemorative narrative is not developed from a nationalistic perspective but focussed on more general victims of the Stalinist era (Kundakbayeva & Kassymova, Citation2016). However, museum content features political and artistic Kazakh figures and portraits and narratives concerning those Kazakh nationals incarcerated. The final element is a celebration of progress and leadership since independence in 1991. The narrative culminates in a clear focus on citizenship, Kazakh nationhood and achievements since 1991.

The partial treatment of female history suggests that commemorative practice, content and interpretation was consciously part of the design. The absence of interpretation surrounding issues of sexual violence in the memorialisation processes being symptomatic of this selective process (Satymbekova, Citation2017). Rates of birth at Alzhir and the growth of the child population was a direct result of systematic rape and abuse. This tragic narrative is absent in Alzhir, which instead concentrates on the skills and output of female prisoners and their treasured possessions, providing at best a partial perspective of the history of this place. Furthermore, the issue of incarceration of infants is given similar limited consideration. At Alzhir, children, deported with their mothers, or born in the Camp were classified as criminals from birth. They were separated from their mothers and relocated to a network of 18 orphanages within the Karlag region. This narrative of systematic crimes against women and children is not the primary narrative of what was a prison for women and children. Notably, the consideration of areas such as sexual violence is similarly absence in many memoirs and literature of the Gulag (Toker, Citation2019). Interpretation at Alzhir is selective, there is no accessible archive, and building have decayed. Visitation remained low until 2017 when visitation to museum and the nation increased as a consequence of the Astana International Expo event (see ).

Table 2. Alzhir visitors (Alzhir Museum Management).

When questioned on this subject, one stakeholder offered the following:

… it's very difficult to reach this place for local people … in the case of Astana (now Nur-Sultan), maybe people know we have such a site, but they don't know how to get here

Tour Operator, Nur-Sultan

This is a doubtful justification given the location on the primary Kugaldzhinskoye Highway, only 40 km from Nur-Sultan. The website has access details (see https://museum-alzhir.kz/en/) and can be located on directional software and there is a single directional sign from the highway (see ).

The wider lack of appreciation of Gulag history and sites was considered by Applebaum (Citation2003), who hypothesised that low awareness was partially due to limited media and literary consideration. This is reiterated in recent work covering the literature of Gulag and Nazi Camps, wherein the prominence of Holocaust testimonials, such as; Primo Levi, Elie Wiesel, Charlotte Delbo and Tadeusz Borowski is more evident than equivalents on the Gulag (Toker, Citation2019). Clearly, the impact of the Gulag on the national psyche in Russia and other ex-Soviet nations is pervasive but has generated far less interest beyond their borders. Indeed, the limited filmic representation of Gulag operation, and the absence of ‘liberation’ footage further reduce awareness and interest. As one travel agent noted in interview:

… our government tries to leave it because they don't want any association with the Soviet times.

Museum 2: Karlag museum, Dolinka (www.karlagmuseum.kz/kz)

There is no speech about the camps … people living in Karaganda, they know there was a camp but they never talk about it

Former Curator, Karlag Museum

The second subject; the Karlag Museum, or more fully; the Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp () of The People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs,Footnote2 is located in Central Kazakhstan, south of the regional capital; Karaganda. It is over 300 km from north to south and more than 200 km from east to west. It comprised a collection of incarceration and forced labour camps spread across the Steppe. Its economic output extended from mining to steel manufacture, from textiles to agriculture, in more than 100 sub-Camps. The overall economic contribution of the Gulag system was important to the USSR, and the incarcerated had few options but to work as directed (Applebaum, Citation2003). The museum records the origins of the Gulag as an element of Soviet colonial domination; however, consideration of those who staffed and directed this facility at a local and Soviet level is given limited consideration. The museum is surrounded by decaying buildings since conservation was very limited following closure of the Gulag (Kundakbayeva & Kassymova, Citation2016). Elements of the museum opened in 2001, originally sharing a buildings with a medical facility and only in 2009, was the Gulag administrative building fully designated as a Gulag museum (Barnes, Citation2013). Given the enormity of the site and the shadow of this period on Kazakh history, the relatively late development of the museum is interesting. Since 2009, the facility has comprised over thirty interpretation halls and exhibition spaces, over three levels. It combines narrative panels, photography and artefacts with experiential practices. The museum provides detail of forced mass deportations during the Soviet era and the repression of Kazakh intelligentsia, culture and artists. Gulag life, including economic and scientific achievements are also interpreted. Prison artefacts, photographs and narratives are displayed along with diorama models of the Camp. Recreated incarceration and torture cells feature yet this was an administrative building and not the authentic site of such acts. The pursuit of ‘authentic’ experiences has been the subject of wider debate in tourism (Herbert, Citation1995; MacCannell, Citation1973) and the boundaries between memorable experiences and authenticity is challenged in many of the Karlag exhibits, interpretation and public awareness raising activities. Notably, since 2013, the museum has operated a ‘Night in Karlag’ event, attended by over 1,000 predominantly local visitors. It incorporates staged scenes of Gulag life; recreating sensational, violent and gratuitous elements (Tiberghien & Lennon, Citation2019). Such ‘entertainment’ contributes to shaping local collective memory, yet, even with such animation activity, museum visitation remained marginal until 2017 when visitors to the museum and to the nation increased as a consequence of the Astana International Expo event(see ).

Table 3. Karlag: Number of visitors (Karlag Management).

Herein, the ambiguity of Gulag history interpretation is presented through animated spectacle, designed to educate and build awareness; yet visitation remains low. Once again, location may be a factor and it is notable that this part of central Kazakhstan is remote and expensive to reach via public transport. Clearly, proximity to centres of population helps to increase visitor numbers in analogous dark tourism sites (Winter, Citation2009). However, low visitation was seen by some tour operators as caused by more than the remote location. For some, the site was deliberately avoided because of the association with Soviet times and the deportation and incarceration of that period had left its imprint on the Kazakh population. Indeed, now this multicultural nation, is very much a consequence of the forced movement of peoples during the Soviet era. Kazakh citizens are descendants of deportees, prisoners and those employed in the military and Gulag system. Furthermore, following closure of the Karlag, many prisoners and those employed in the camps remained in the region, former captors and their guards living in the city and region. As one stakeholder recorded:

The main population here (in Karaganda) – their grandparents are former employees of the NKVD or former prisoners … these people survived, nobody took revenge, nothing happened.

Former Archivist, Karlag

Such attitudes might also have contributed to the re-appropriation of heritage buildings as living accommodation by locals given the limited conservation of Karlag heritage that followed closure of Gulag operations. For some, this was further evidence of the dilution of the past:

… if they (Gulag buildings) are demolished, there will be no sign or evidence of the camp … you need to show these places, they should be preserved … not for people's living places …

Karlag Tour Guide

However, the reality is probably more complex since in a number of cases such buildings have been in use for decades since the closure of Gulag sites. They are historic buildings but their reuse as part of Soviet and post-Soviet cities for some decades was also illustrative of the normalising and accommodation of Gulag heritage. Barenberg (Citation2014), in his work on the Arctic city of Vorkuta and the Vorkuta Gulag considered the complex interrelationship between urban context, industrial output and incarceration of prisoners in an attempt to understand the nature of space and identity in the Soviet and Post-Soviet period.

The ambiguous position of evidential heritage was illustrated elsewhere in the Karlag landscape. The Karabas Gulag railway terminal, where prisoners arrived and were selected for forced labour is still used as a rail terminal with access to an operating Kazakh prison, which in turn utilises former Gulag incarceration buildings. This built heritage is unmarked and understanding of its previous role is not clear. As the former Karlag Museum curator noted:

We have Karabas station, it was a major distribution centre for prisoners, people were taken there and distributed to the camps … there are many burial graves around, they are not named, they have no signs, locals don't even know about their existence.

Other Kazakh Gulag heritage sites

Spassk 99 and related mass grave sites

So many humans buried there, so many lives destroyed.

Tour Operator, Alzhir

The Spassk 99 Special Camp, of the former National Commissariat of Internal Affairs, is located 45 km from Karaganda. This site with few visitors and no signage was a Prisoner of War Camp which also served to incarcerate political prisoners. The numbers buried here in mass graves remain unknown and much of the site now operates as a Kazakh military base. Such reuse of Gulag sites and buildings is also evident in the regional capital; Karaganda. Herein the former NKVD headquarters have been re-appropriated as the central Kazakh police offices and the original purpose of the buildings is not indicated or signalled.

In the Spassk 99 site, it is estimated that some 67,000 foreign prisoners were detained between 1941 and 1950 and officially some 7,765 prisoners were buried in mass graves along with a greater number of political prisoners (Zagarulko, Citation2005). Foreign funded monuments and memorial statues exist here to commemorate those international fatalities buried on this site. Memorials associated with the following nations; Armenia, Romania, Japan, Finland, South Korea, Germany, Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Ukraine and Russia are present reflecting the scale of each nation's loss. However, there is no formal interpretation detailing the purpose, nature and context of this facility during the period of the Karlag. Similarly, there is no site management and the full extent of the mass graves are not obvious to the visitor. Burials here followed deaths in the wider Karlag, and the estimated mass grave is in excess of 1.5 sq. kms.,although without detailed forensic archaeology this remains uncorroborated. After the camp was closed in 1950, it was re-used by the Kazakh military as a driver training facility, obliterating much of the built heritage and original grave markings. The presence of mass graves in Kazakhstan; unmarked, difficult to locate and with limited or non-existent archive records are not unusual. The limited conservation or interpretation of such sites was seen by some stakeholders as part of a collective amnesia about the darker past of this nation. As one stakeholder noted:

It is connected with mentality, mainly we would like to show positive places … we are ashamed, we do not want to remember it and we do not want wide publicity.

Karlag Tour Guide

It should be noted that the UN International Convention on enforced disappearances supports the ethical imperative to develop better awareness of such sites, with forensic archaeology and encourages the legal pursuit of criminal activities (Jaquement, Citation2008). However, Kazakhstan has a weak history of criminal prosecutions following the Soviet period and this has led to distrust of the Kazakh judiciary and Police. The legal system is characterised by pro-accusation bias, low judicial autonomy and high levels of government influence on judgements (Trochev & Slade, Citation2019).

In this case, the narrative is diluted and the identities of the vast majority of victims have been lost. At Spassk 99, the site is overgrown and neglected. Yet, by comparison, the two museums examined exist to provide education and public awareness. They often also provide the foundation for variable heritage narratives (Adams & Rustemova, Citation2009). Indeed, the Gulag and its history has, in the past, been politicised by the Kazakh government to service the macro-political agenda in negotiations with its neighbour Russia, whilst at other times it seems to be avoided or offered minimal consideration.

Osakarovka orphanage and Mamochkino cemetery

All of these children from Karlag and Astana were sent there. There was a high level of child mortality, many deaths

Tour Operator, Alzhir

The Osakarovka orphanage was part of a network of 18 children's homes across the Karlag region. These ‘orphanages’ were prisons, with gates and barbed wire for an infant population that continued to increase as a result of rape and sexual assault of female prisoners. Children, forcibly separated from their mothers, were relocated to orphanages where infant mortality was significant (Hoffman, Citation2009). The orphanages operated under the jurisdiction of the NKVD, underlining their political role. The orphan population included: those born in prison camps; those left behind when parents were imprisoned, and those incarcerated by the Soviet authorities. For survivors, the emotional and economic impacts of a Gulag childhood were considerable (MacKinnon, Citation2012). The buildings that comprised Osakarovka are currently still in use as a facility for orphan children aged 3–12 years. There are indications of the buildings previous use and role in the Gulag system.

Many who did not survive Osakarovka, remain in Mamochkino cemetery or other regional unmarked graves (Miheeva, Citation2010). According to stakeholders, local awareness of this history is limited;

Even now barely anyone knows where these graves are located …

Museum Manager, Karlag Museum

This is indeed the case and this unmaintained cemetery is located 40 km from Karaganda, it lacks any route directional signs, interpretation with only a single sign at the entry point (see ).

The rare visitors are unlikely to fully appreciate the scale of the original boundaries of the site which extends to 1.25 sq.kms (Memorial, Citation2001). Over building and infrastructure development has made graveyard boundaries difficult to locate and only a small proportion of the original site is maintained and fenced. It receives no funding from central or regional government and for some the knowledge of its past has already been diluted or lost. However, Mamochkino is an important historical burial site with potentially significant educational narrative. However, like the Osakarovka orphanage, it is not a simple fit for the new Kazakh narrative of independence and reflects the dark and difficult journey to nationhood. The tragedy of the site and its victims remains:

Dysentery was very common (in Osakarovka orphanage) … winters were cold there … in general all children under the age of one year died. They were buried in the cemetery … now there is nothing.

Retired Karlag Museum Archivist

Contentious Gulag heritage and dark tourism

These sites illustrate the ambiguity and omission evident in the treatment of Gulag heritage in Kazakhstan. The two museums considered, constitute the major interpretation of the Soviet and Russian colonial period. However, many Gulag heritage sites, graveyards and building are not conserved or identified. Invariably, in such circumstances, their full past is unattributed. The educational and heritage of some sites is highlighted by companies such as Nomadic Travel (Citation2020) and their ‘Kazakhstan: Back to the USSR’ tour features Gulag ruins and related but unattributed sites. Indeed, when this type of tourist activity containing Gulag elements was originally marketed by the company in 2015, it was met with significant national (Kazakh) resistance at travel and trade fairs. As the Nomadic Travel Manager recorded:

Some of the locals and the authorities said; Why are you not patriots? Why are you telling such stories about our country? We have Baravoie, Balkhash, (natural heritage attractions) we have the picturesque nature. Why do you show this negative material?

The majority of locals don't go to these museums at all and to … Karlag in particular

Karaganda Tour Operator

For others this was conflated with the impact and influence of the Soviet era which was still in evidence:

… they (the Soviets) killed the memory, the education and the memory, without memory, without education people become more obedient

Former Karlag Museum Director.

The reality is probably more complex and the Kazakh state funded museums considered do constitute de facto commemorative interpretation of the Gulag period. Yet, other heritage sites examined contained limited interpretation, received few, if any, visitors and were essentially neglected. Sharpley and Stone (Citation2009), refer to this as interpretive dissonance, however these attitudes have to be tempered by the clear evidence of state museum development, creating memorials and maintaining educational record of this period. The local response and reluctance to engage with the darker elements of Kazakh Gulag history may possibly be seen as part of a desire for an alternative past that is useable and tolerable to recall (Wertsch, Citation2002). This thinking might allow Kazakhs to redefine their identity post-independence. However, although ostensibly now independent, there remain many issues with civil liberties and free speech in Kazakhstan (Trochev & Slade, Citation2019). Critical analysis of the USSR and earlier history is rare and selective (Licata & Mercy, Citation2015). This is connected to partial covering in respect of the period of Soviet domination. The Gulag was part of a repressive state; it was a forbidden area, rarely discussed or visited (Miheeva, Citation2010). Some of those who lived through this period and survived are reluctant to reconcile that dark past with the present and there is at least a partial societal amnesia in respect of the period. In many nations, emerging from traumatic events, citizens seek to distance themselves from difficult histories (Roth et al., Citation2017). Halbwachs (Citation1992), recorded the disruptive psychological impacts of such trauma on inhabitants and the unwillingness of victims to communicate about their shared dark pasts. This response whether in; museum interpretation, conservation or even discussion, is a reaction to the period of repression, deportation, incarceration and fear. Despite a national network of Kazakh Gulag Camps, only two are developed as museums. Such omission can be contrasted with individual memory which exists beyond survivors, and their descendants. The Gulag is remembered by individuals and groups yet partially removed from the traumatic events both historically, culturally and geographically. In tourism terms, the limited imagery, film, photographs and literature will limit awareness (Mitchell, Citation1994). Imagery is central to tourism marketing and touristic images are essential symbols, stored in collective memories of place and time (Marschall, Citation2012). Visiting or ignoring symbolic memory sites and heritage is inherently connected with the construction and understanding of national identity (Nora, Citation1989). In this sense, the loss of such dark heritage sites in Kazakhstan should be seen as more than non-conservation or alternative prioritisation of resources. Rather this is part of a process of omission and ambiguity in the treatment of the recent past. The relationship with tourism is important since:

… it is also an ideological framing of history, nature and tradition

(Desmond, Citation1999 xiv)

Tourism can work as an information channel for destinations and nations to communicate messages on identity and nationality. The loss and destruction of sites elsewhere in the world reaffirms this importance. As Marschall (Citation2012) noted the deliberate destruction of Osama Bin Laden's compound in Abbottbad, Pakistan, and his burial at sea, was at least partially about averting memory of a physical place and preventing pilgrimage and martyr veneration. Similar debates exist in respect of the Fuhrer Bunker in Berlin and Hitler's birthplace (Lennon & Foley, Citation2000). Indeed, research in this area frequently relates to the holocaust and the collective trauma of genocide (Mazur & Vollhardt, Citation2015). In the case of the holocaust, memory of the period has undoubtedly contributed to religious and nationalistic narratives (Alexander et al., Citation2004) and the emergence of a shared identity (Canetti et al., Citation2018). In Kazakhstan, the re-utilisation of Gulag associated heritage buildings and the limited conservation of sites is perhaps part of a similar phenomenon.

… I think it's (the Gulag) massive, much bigger than the Holocaust. But it's like amnesia, self-induced, you want to forget.

Tour Operator Nur-Sultan

One former archivist actively involved in teaching Gulag history in Kazakh secondary schools commented:

… this topic is really significant in the current time … in order not to repeat these mistakes, this topic must stay significant

A more comprehensive understanding motivations and interest in Gulag sites amongst Kazakh and international visitors would benefit this research. It would help understand the socially constructed and (possibly) government sanctioned perspectives on Gulag heritage. If Kazakh awareness is low and school and media coverage is partial, then lower levels of visitation are understandable. The Museums and heritage sites examined are influenced by this collective ambiguity and selectivity in respect of which heritage is explored, interpreted and conserved. Baudrillard (Citation1983), argued that tourism spaces have become commodified and hollowed spaces suggesting that the real and authentic has disappeared. In the case of the Kazakh Gulag sites, some locations are overlooked and omit references to a darker past. However, such responses are not uniform in the states of the former USSR. The presence of so few museums of the Gulag in this vast nation may be contrasted with the situation in Russia. The State Museum of Gulag History in Moscow, was originally conceived in 2001, and following significant investment (primarily from Moscow civic administration rather than central government), moved to new purpose developed premises in 2015 (https://gmig.ru/en/). Furthermore, individuals can access the Central Gulag archives in Moscow and the Memorial Society Archive (http://old.memo.ru/library/arh_eng.pdf) for the purposes of research. Similarly, across Russia there are a range of regional museum projects and associations working to preserve evidence of Gulag history although relative profiles and levels of visitation has been low. In the case of Perm-36, a former camp which became a Gulag museum in 1995, there has been a long struggle for local and national museum funding. It became an ideological battleground and target for self-styled Russian patriots who argued it was distorting Soviet history (Goode, Citation2020). The regional government forced takeover of the management of the museum saw it transformed into a site honouring the Gulag rather than its victims. The Memorial organisation (https://www.memo.ru/en-us/memorial/mission-and-statute/) was involved in this struggle, registering national and regional attempts to suppress and marginalise the history of the Gulag (Cichowlas, Citation2014). Indeed, the presence of Memorial, its international connectivity and ongoing conflicts with the Russian government is one of the substantial differences with the situation in Kazakhstan, where such critical voices are less audible. The coverage of Gulag heritage in Kazakhstan is the product of a number of competing factors. Gulag history is not central to the current narrative of Kazakh nationhood and independence, yet it is neither ignored nor covered. Evidence, records and heritage of the Gulag exists and the nation commemorates victims of political repression annually on 31 May each year (Boteu, Citation2019) and its 1991 independence from the USSR on 16 December. This later date being synonymous with Almaty protests of December 1986 (Bransten & Jiyenday, Citation1996). However, historical consideration of this period remains ambiguous and influenced by the relationship with Russia that predates the USSR and relates to a colonial past of oppression and repression (Bogumil, Citation2018). The heritage and history of the Kazakhstan Gulag Sites are neither at the heart of education curriculum, museum provision, tourism nor conservation yet their legacy endures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

J. John Lennon

J. John Lennon is Professor and Dean of Glasgow School for Business and Society, Glasgow Caledonan University and the founding director of the Moffat Centre for Travel and Tourism. John has undertaken more than 700 commercial tourism projects in over 50 countries.

Guillaume Tiberghien

Guillaume Tilberghien is a Lecturer and Programme Leader at Glasgow University. His main research and teaching activities focus on the relationships between Cultural Heritage Tourism, Sustainable Tourism Development and Tourism Marketing. Guillaume also conducted and participated in several consulting projects in the fields of Tourism Marketing and Management in Central Asia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Notes

1 Gulag is an acronym for Glavnoe upravlenie lagerei, although it has come to label the range of prison, punishment and transit camps of the Soviet era.

2 NKVD is the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, romanized: Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, abbreviated NKVD) of the Soviet Union.

References

- Adams, L. L., & Rustemova, A. (2009). Mass spectacle and styles of governmentality in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Europe-Asia Studies, 61(7), 1249–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130903068798

- Alexander, J., Eyerman, R., Giesen, B., Smelser, N., & Sztompka, P. (2004). Cultural trauma and collective identity: Toward a theory of cultural trauma. University of California Press.

- Alzhir Museum. (2018). “ALZHIR” camp history. http://museum-alzhir.kz/en/about-museum/alzshir-camp-history.

- Applebaum, A. (2003). Gulag: A history. Doubleday Press.

- Arendt, H. (1973). The origins of totalitarianism. Harcourt BraceJovanovich.

- Ashworth, G. (1996). ‘Holocaust tourism and Jewish culture: The Lessons of Krakow – Kazimierz’. In M. Robinson, N. Evans, & P. Callaghan (Eds.), Tourism and culture – towards the 21st century (pp. 123–137). Athenaeum Press.

- Bandelj, N. (2002). Embedded economies: Social relations as determinants of foreign direct investment in central and Eastern Europe. Social Forces, 81(2), 411–444. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0001

- Barenberg, A. (2014). Gulag town, company town forced labour and its legacy in Vorkuta. Yale University Press.

- Barnes, S. A. (2011). Reclaiming the margins and the marginal: Gulag practices in Karaganda, 1930s. In S. A. Barnes (Ed.), Death and redemption: The Gulag and the shaping of Soviet society (pp. 28–78). Princeton University Press.

- Barnes, S. A. (2013). A night in Karlag. http://russianhistoryblog.org/2013/12/a-night-in-karlag/.

- Barnes, S. A. (2020). Remembering the Gulag in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. In S. M. Norris (Ed.), Museums of Communism: New memory sites in central and Eastern Europe (pp. 106–135). Indiana University Press.

- Baudrillard, J. (1983). Simulations, (Foss, P., Patton, P., and Beitchman, P.,. Trans.). Semiotext Inc.

- Beech, J. G. (2000). The enigma of Holocast sites as tourist attractions – the case of Buchenwald. Managing Leisure, 5(1), 29–41. London: Taylor Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/136067100375722

- Bogumil, Z. (2018). Gulag memories: The Rediscovery and commemoration of Russia’s repressive past. Berghahn Books.

- Boteu, S. (2019). Kazakhstan marks day of remembrance of victims of political repression in Astana Times. 6.6.2019 https://astanatimes.com/2019/06/kazakhstan-marks-day-of-remembrance-of-victims-of-political-repression/.

- Botterill, D., & Jones, T. (2010). Tourism and crime. Goodfellow Publishing Ltd.

- Bransten, J., & Jiyenday, A. (1996). Kazakhstan: Almaty – a look back to the events of December, 1986 in Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/1082701.html.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, S., McDonagh, P., & Shultz, C. (2012). Dark marketing: Ghost in the machine or skeleton in the cupboard? European Business Review, 24(2), 196–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/095553412112224771

- Cameron, S. (2012). The Kazakh famine of 1930-33 and the politics of history in the post-Soviet space. Kennan Institute, Woodrow Wilson Centre. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/the-kazakh-famine-1930-33-and-the-politics-history-the-post-soviet-space.

- Canetti, D., Hirschberger, G., Rapaport, C., Elad-Strenger, J., Ein-Dor, T., & Rosenzvieg, S. (2018). Holocaust from the real world to the Lab: The effects of historical trauma on contemporary political cognitions. Political Psychology, 39(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12384

- Chhabra, D. (2008). Positioning museums on an authenticity continuum. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.12.001

- Cichowlas, O. (2014). The Kremlin is trying to erase memorise of the Gulag in The New Republic, June 2014, https://newrepublic.com/article/118306/kremlin-trying-erase-memories-gulag.

- Dalziel, I. (2020). Book Auschwitz, get a free lunch. In F. Bajohr, A. Drecoll, & J. Lennon (Eds.), Dark tourism, Reisen zu Statten von Krieg, Massengewalt und NS-Verfolgung (pp. 35–46). Metropol.

- Dann, G. (1996). The people of tourist brochures. In T. Selwyn (Ed.), The tourist Image (pp. 112–147). John Wiley.

- Desmond, J. (1999). Staging tourism: Bodies on display from Waikiki to Sea world. University of Chicago Press.

- Elliot, G. (1972). Twentieth century book of the dead. Penguin.

- Fentress, J., & Wickham, C. (1994). Social memory. Blackwell.

- Friedrich, M., & Johnston, T. (2013). Beauty versus tragedy: Thanatourism and the memorialisation of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 11(4), 302–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2013.852565

- Gessen, M., & Friedman, M. (2018). Never remember searching for Stalin’s Gulags in Putin’s Russia. Colombia Global Reports.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor.

- Goode, J. P. (2020). Patriotism without patriots? Perm-36 and Patriotic Legitimation in Russia. Slavic Review, 79(2), 390–411. https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2020.89

- Habermas, J. (1962). The Structural transformation of the public Sphere: An inquiry into a category of Bourgeoise society. Polity.

- Halbwachs, M. (1992). On collective memory. University of Chicago Press.

- Hartmann, R. (2014). Dark tourism, thanatourism, and dissonance in heritage tourism management: New directions in contemporary tourism research. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(2), 166–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2013.807266

- Harvey Lemelin, R., Powys Whyte, K., Johansen, K., Higgins Desbiolles, F., Wilson, C., & Hemming, S. (2013). Conflicts, battlefields, indigenous peoples and tourism: Addressing dissonant heritage in warfare tourism in Australia and North America in the twenty-first century. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(3), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2012-0038

- Herbert, D. (1995). Heritage, tourism and society. Burns and Oates.

- Hoffman, D. (2009). The Littlest Enemies: Children in the shadow of the Gulag. Slavic Publishers.

- Hunter, W. C. (2008). A typology of photographic representations for tourism: Depictions of groomed spaces. Tourism Management, 29(2), 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.008

- Ivanova, G. M. (2000). Labour Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Soviet totalitarianism system. M E Sharp.

- Jaquement, I. (2008). Fighting amnesia; Ways to uncover the truth about Lebanon’s missing. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 3(1), 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijn019

- Kalinowska, M. (2012). Monuments of memory: Defensive mechanisms of the collective psyche and their manifestation in the memorialization process. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 57(4), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5922.2012.01984.x

- Khlevniuk, O. V. (2004). The history of the Gulag: From collectivisation to the Great terror. Yale University.

- Kundakbayeva, Z., & Kassymova, D. (2016). Remembering and forgetting: The state policy of memorializing Stalin’s repression in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, 44(4), 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2016.1158157

- Lennon, J. (2009). Tragedy and heritage: The case of Cambodia. Tourism Recreational Research, 34(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2009.11081573

- Lennon, J. J., & Foley, M. (2000). Dark tourism: The attraction of death and disaster. Continuum.

- Licata, L., & Mercy, A. (2015). Collective memory, social psychology. In James D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 173–198). Elsevier.

- Lloyd, A. (2007). Guarding against collective amnesia? Making significance problematic: An exploration of issues. Library Trends, 56(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2007.0052

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1086/225585

- MacCannell, D. (1989). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Schocken.

- MacKinnon, E. (2012). The Forgotten: Childhood and the Soviet Gulag, 1929–1953, The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies, No 2203. https://carlbeckpapers.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/cbp.

- Marschall, S. (2012). Personal memory tourism’ and a wider exploration of the tourism-memory nexus. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 10(4), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2012.742094

- Mazur, L. B., & Vollhardt, J. R. (2015). The prototypicality of genocide: Implications for international intervention. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 16(1), 290–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12099

- McDowell, S. (2008). Selling conflict heritage through tourism in Peacetime Northern Ireland: Transforming conflict or Exacerbating Difference? International Journal of Heritage Studies, 14(5), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250802284859

- McDowell, S. (2009). Negotiating places of pain in post-conflict Northern Ireland: Debating the future of the Maze prison/long Kesh. In W. Logan & K. Reeves (Eds.), Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with difficult heritage (pp. 160–176). Routledge.

- Memorial. (2001). Karlag: Endless Pain of hard times (Memoir) The international Charitable society of history, Enlightenment and Human Rights Protection. Bolashak Karaganda University.

- Meyer, J., Boli, J., Thomas, G., & Ramirez, F. (1997). World society and the nation state. American Journal of Sociology, 103(1), 144–181. https://doi.org/10.1086/231174

- Miheeva, L. (2010). Inostrannye voenoplennye i internirovannye vtoroi morovoi voiny v Tzentralnov Kazahstane (1941-nacialo 1950) Karaganda, MGTI -Lingva.

- Mitchell, W. (1994). Picture theory: Essays on verbal and visual representation. University of Chicago Press.

- Neill, W. V. J. (2017). Representing the Maze/long Kesh prison in Northern Ireland: Conflict Resolution centre and tourist Draw or Trojan Horse in a culture War? In J. Wilson, S. Hodgkinson, J. Piché, & K. Walby (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of prison tourism (pp. 241–259). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nomadic Travel. (2020). Back in the USSR Tour. Retrieved from http://nomadic.kz/tours-common/important/kazakhstan-back-in-the-ussr/.

- Nora, P. (1989). Between memory and history: Les lieux de mémoire. Representations, 26, 7–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928520

- Norris, S. M. (2020). Ed) museums of Communism: New memory sites in central and Eastern Europe. Indiana University Press.

- Ospanova, A. (2020). Kazakhstan celebrates its Independence Day. The Astana Times, 16.12.2020. https://astanatimes.com/2020/12/kazakhstan-celebrates-its-independence-day/.

- Pearce, S. (1992). Museums, objects and collections. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Piché, J., & Walby, K. (2010). Problematizing carceral tours. British Journal of Criminology, 50(3), 570–581. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq014

- Poria, Y., Reichel, A., & Biran, A. (2006). Heritage site perceptions and motivations to visit. Journal of Travel Research, 44(3), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505279004

- Rivera, L. (2008). Managing “spoiled” national identity: War, tourism, and memory in Croatia. American Sociological Review, 73(4), 613–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240807300405

- Roth, J., Huber, M., Juenger, A., & Liu, J. H. (2017). It’s about valence: Historical continuity or historical discontinuity as a threat to social identity. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 5(2), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v5i2.677

- Sant-Cassia, P. (1999). Tradition, tourism and memory in Malta. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 5(2), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2660696

- Satymbekova, R. (2017). The Gulag Camp “alzhir”: memorialization practices, MA Dissertation, Budapest, Department of Gender Studies, Central European University.

- Seremetakis, N. (1994). The memory of the senses: Historical perception, commensual exchange and modernity. In L. Taylor (Ed.), Visualizing theory (pp. 214–229). Routledge.

- Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. (2009). The darker side of travel. Channel View Publications.

- Slade, G. (2017). Remembering and forgetting the Gulag: Prison tourism across post-Soviet region, The Palgrave Handbook of prison tourism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Solzhenitsyn, A. (1963). One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich. Penguin.

- Solzhenitsyn, A. (1986). The Gulag Archipelago Volumes I,II, III. Random House.

- Strange, C., & Kempa, M. (2003). Shades of dark tourism: Alcatraz and Robben Island. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00102-0

- Theroux, P. (2009). Ghost Train to the Eastern Star. Penguin.

- Tiberghien, G., & Lennon, J. J. (2019). Managing authenticity and performance in Gulag tourism. Tourism Geographies, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1674371

- Toker, L. (2019). Gulag literature and the literature of the Nazi camps: An intercontextual reading. Indiana University Press.

- Torchin, L. (2012). Creating the witness documenting genocide on film, video and the Internet. University of Miunnesota Press.

- Trochev, A. (2018). Transitional justice attempts in Kazakhstan. In C. M. Horne & L. Stan (Eds.), Transitional Justice and the former Soviet Union: Reviewing the past, looking toward the future (pp. 88–108). Cambridge University Press.

- Trochev, A., & Slade, G. (2019). Trials and tribulations: Kazakhstan’s criminal Justice Reforms. In J. F. Caron (Ed.), Kazakhstan and the Soviet legacy (pp. 75–99). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tunbridge, J. E., & Ashworth, G. J. (1996). Dissonant heritage: The management of the past as a resource in conflict. John Wiley and Sons.

- Turlygul, T. T., Zholdasbayev, S. Z., Kozhakeyeva, L. T., & Zhusanbayeva, G. M. (2015). History of Kazakhstan, 11th grade (3rd ed.). Mektep.

- Uskembayev, K. S., Saktaganova, Z. G., & Zuyeva, L. I. (2019). History of Kazakhstan. 8-9th grades (1900-1945). Part 1. Mektep.

- Volkava, E. (2012). The Kazakh famine of 1930-33 and the Politics of history in the post-Soviet space. Kennan Institute, Woodrow Wilson Centre. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/the-kazakh-famine-1930-33-and-the-politics-history-the-post-soviet-space.

- Wertsch, J. V. (2002). Voices of collective remembering. Cambridge University Press.

- Wherry, F. (2007). Trading impressions: Evidence from Costa Rica. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 610(1), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206296818

- Wight, A. C., & and Lennon, J. J. (2007). Selective interpretation and eclectic human heritage in Lithuania. Tourism Management, 28(2), 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.006

- Winter, C. (2009). Tourism, social memory and the Great War. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(4), 607–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.05.002

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications.

- Zagarulko, M. M. (2005). Regionalye struktury GUPVI NKVD 1941-151. Izadateli.