?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the resilience of the Turkey tourism industry to exogenous shocks over the period from January 1997 to December 2018. Using the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag model, our results show strong evidence for the existence of an asymmetric effect of terrorist attacks on tourism receipts and the number of tourist arrivals. Interestingly, the results reveal that terrorist attacks decreases have a higher impact on tourism demand compared to the impact of terrorist attacks increases. This finding confirms the resilience of the Turkey tourism sector to exogenous shocks. The result indicates the significant role of the Turkey government in supporting the tourism sector during periods of instability. These findings offer several valuable insights for policy-makers and researchers.

Introduction

The recent coronavirus pandemic has significantly affected the worldwide tourism industry, and the effect is expected to continue on the industry going forward. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, Citation2018, Citation2020a, Citation2020b) has repeatedly highlighted the importance to evaluating of the extent which terrorism, wars, political violence, financial and economic crises, health crises, and natural disasters affect the countries’ tourism demand and the sustainability of the tourism sector. In particular, it has renewed the interest in the importance and necessity of measuring tourism’s vulnerability and resilience to exogenous shocks in general. This topic is critical because these exogenous shocks have questioned the tourism sector’s future evolution and prosperity (Charfeddine & Goaied, Citation2019; Khazai et al., Citation2018; Sönmez, Citation1998; Steiner, Citation2007). Although some studies have discussed the effects of political unrests, wars, and natural disasters on tourism activity, the impact of terrorism and economic and financial disasters on tourist activity has only recently emerged (Charfeddine & Goaied, Citation2019; Chesney et al., Citation2011).

Theoretically, it acknowledged that terrorism has severe adverse effects on tourism activity (Araña & León, Citation2008; Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998). Terrorism might decrease or stop of the tourist flow in some tourist destinations, making terrorist attacks a significant concern to the tourism industry (Corbet et al., Citation2019). Terrorism is also considered a significant obstacle to global tourism by generating panic and increasing instability (Liu & Pratt, Citation2017). The recent conflicts in the ‘Middle East and North Africa’ (MENA) region have proved this. The terrorism, war, and civil/political unrest incident hurt the tourism industry in the area by reducing tourist arrivals and tourist revenue. For instance, in Turkey, when the number of attacks increased from 94 attacks in 2014 to 542 attacks in 2016, the tourism receipt and tourism arrivals decreased from $29,552 million and 39,811 million visitors in 2014 to $18,743 million and 30,289 million visitors in 2016, respectively, indicating the several challenges facing the significant sector, such as tourism. Thus understanding the nature (non-linear asymmetric) and factors influencing the tourism demand in the short- and long-run may notably help propose market-oriented policies in periods of high terrorist attacks, political instability and crises.

This article aims to advance our understanding of the influence of terrorism, political instability, natural disaster, and economic and financial crises on tourism activity in general, and particularly in Turkey. Such a study is further emphasized by exploring the possible existence of non-linearity (asymmetric impact) in the tourism-terrorism nexus. Three main reasons may explain the presence of a possible asymmetry in the terrorism–tourism nexus. First, terrorist attack shocks create sudden changes and structural breaks in the tourist arrivals and tourism receipts time series, which create evidence for non-linearity in these time series (Charfeddine & Goaied, Citation2019; Fareed et al., Citation2018). Second, the impact of terrorist incidents on tourist flow is known to have a long-lasting effect with different degrees of impact duration during periods characterized by increases in terrorist attacks versus periods of decreases in terrorist attacks (Hadi et al., Citation2020; Pizam & Smith, Citation2000). Finally, the economic and monetary expansion policies implemented by the governments and the monetary authorities during periods of terrorist attacks are generally advanced as causes for the existence of asymmetry (see Alqaralleh, Citation2020; Charfeddine & Barkat, Citation2020; Kandemir Kocaaslan, Citation2019). Evidence of asymmetric impact is known to have important implications for policymakers when designing strategies for recovery, and it also has important implications for forecasting tourism demand (see Alqaralleh, Citation2020; Bodman, Citation2001, among others).

The current article attempts to add to the growing literature examining the tourism–terrorism nexus by focusing on the case of Turkey. Several reasons motivate the choice of Turkey as a case of study. First, its distinctive geographical location. Turkey is located close to three important continents, Europe, Asia, and Africa, sharing boundaries with Middle Eastern, Caucasian and European nations. The state’s geographical location impacts its demographics. Turkish society consists of a multi-ethnic community such as Muslims, Armenians, Kurds, and Greeks, contributing to its cultural diversity and political instability.Footnote1 Second, Turkey is one of the nation’s hit hardest by terrorism (Feridun, Citation2011). According to Rodoplu et al. (Citation2003), terrorist incidences killed about 30,000–35,000 Turkish citizens from 1984 to the 2000s. Since then, the state has become exposed to terrorist incidences on tourist facilities such as Izmir, Istanbul, Ankara, Marmaris and Antalya. Third, the contribution of tourism P to the GDP represents 12.1% (US$95.6 billion), and the sector grew by approximately 15% in 2018. In 2018, the tourism sector growth in Turkey was the largest of all the European countries, significantly outpaced across world growth of 3.9% and the European of 3.1% (WTTC, Citation2019). Turkey rates as the most preferred destination for tourists in the Middle East and in Europe after France, Spain and Italy. This rank is attributed to Turkey’s high growth rate of tourist flow annually, especially in recent years when tourist arrivals grew by approximately 24% between 2016 and 2018.Footnote2 Consequently, any fall in tourist receipts and tourism arrivals will significantly negatively influence the Turkey economy (e.g. deterioration in economic growth and fall of job creation).

This study has three significant contributions to the tourism–terrorism nexus in tourism-dependent economies. First, unlike previous studies that have generally failed to consider possible non-linearity when exploring the terrorism-tourism nexus, this study uses the Nonlinear ARDL () technique to examine evidence of asymmetry in the effect of terrorism on tourist flow in Turkey in both short-and long-run. Second, it contributes to a growing literature exploring the tourism sector’s resilience by considering different types of events (political turmoil, economic and financial crises, and natural disaster and health crises). Finally, this study analyses the real effective exchange rate’s role in determining the level of tourism demand. The findings of this study improve our understanding of the tourism sector sensitivity to a much range of shocks and how tourism demand reacts to increases and decreases in terrorist attacks. The results will also help policymakers in Turkey, and tourism-dependent economies design adequate tourism recovery strategies and forecast the tourism industry’s future with reliability.

The structure of the article is as follows: Next section offers a brief overview of the related literature followed by the sections that describe various shocks affecting the Turkish tourism industry, the materials and methods, results analyses and finally, the conclusion and the implications are provided.

Literature review

Prior related studies indicate that only recently scholars have begun to look at the tourism industry’s resilience to exogenous shocks. Overall, the existing literature can be grouped into two main categories depending on the econometric approach. The first category includes statistical and econometric models exploring the data-generating process of the tourism demand series. The second category groups the econometric based explanatory models.

In the first category an extensive set of linear and non-linear models were used to account for the principal statistical properties characterizing time series measures for the tourism demand. These statistical properties include high persistent behaviour, structural changes, trends and seasonality. Technically, most of these properties are accounted for by using non-linear econometric models involving the use of stationary and non-stationary data such as unit root tests with structural breaks, long-range dependence process, structural changes model, or a combination of two or more of the previously cited techniques (see Cunado et al., Citation2008; and Charfeddine & Goaied, Citation2019 among others). In the second category, both fundamentals and non-fundamentals factors are used to explain the tourism demand (see Balli et al., Citation2019; Bassil et al., Citation2019; Charfeddine & Goaied, Citation2019; Polyzos, Papadopoulou, and Fotiadis, Citation2021; Polyzos, Papadopoulou, and Xesfingi, Citation2021; Sun & Luo, Citation2021).

In this study, we follow the second strand of literature, where fundamental economic variables, together with exogenous shocks, are used to assess their power to explain the tourism demand. To be consistent with the main objective of the research question for this study, we focus our analysis only on studies that have used non-stationary data to investigate the evidence for a cointegration relationship between the different factors explaining the tourism demand. A review of the non-stationary models applied to the tourism demand context shows that researchers have used panel cointegration and time-series cointegration models to analyse short- and long-run impacts of terrorist incidents on tourism demand. While the tradeoff between a single and cross-countries analysis is always on the debate, in this study, a single country analysis was chosen due to data availability, which allows us to provide more specific country policies.

The following paragraphs, focus our analysis on time- series cointegration approaches investigating the terrorism-tourism nexus. In particular, we will focus our review on studies that assume symmetric effects (such as the Johansen and Juselius (JJ) cointegration and the linear ARDL techniques) versus asymmetric impacts of terrorism on tourism activity (such as the nonlinear ARDL technique).

Among the studies that have used the JJ cointegration technique to explore the terrorism-tourism nexus, Raza and Jawaid (Citation2013) examined the effect of terrorist attacks on tourist flow in Pakistan between 1980 and 2010. Their study shows that terrorism significantly decreases tourism performance in both the short- and long-term. More recently, Samitas et al. (Citation2018) applied the JJ (Citation1990) method to examine the existence of cointegration between terrorist attacks and tourism. They use a monthly dataset for Greece from 1997 to 2012 and find that the effect of terrorist attacks has been negative and persistent in the long-run on tourist arrivals.

Recently, the Auto Regressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) technique to examine the tourism-terrorism nexus has become more popular mainly due to the flexibility of the ARDL model in terms of assumptions (see Pesaran et al., Citation2001). For instance, Song et al. (Citation2011) use the linear ARDL model to examine the influence of financial and economic crises on demand for four types of hotel rooms in Hong Kong. In their study, Song et al. (Citation2011) use several dummy variables to account for and control for external shocks like the ‘SARS’ pandemic of (2003) and the worldwide financial crisis of (2008). Similarly, Lin et al. (Citation2015) use the linear ARDL model to forecast the outbound tourism demand by mainland Chinese residents for up to the year 2020. Their forecasting results highlight the importance of external shocks, including terrorist attacks, in explaining the tourism demand. Their results also show that external shocks are significant factors in explaining the demand for outbound tourism and can bias the results if they are not accounted for.

In a study for Turkey, Feridun (Citation2011) uses the ARDL technique to analyse the influence of terrorism attacks on Turkey tourists flow. Based on annual data during 1986–2006, the author found that tourism has a long-run equilibrium association with terrorism. In his analysis, the author measured the terrorist attacks by the number of casualties (the number of casualties exceeded ten people). He found that the coefficient associated with terrorist attacks is negative as expected and statistically significant. Recently, Liu and Pratt (Citation2017) used time series and panel ARDL models for 95 countries from 1995 to 2012 to explore evidence for a cointegration association between terrorism and tourism activity. As for the terrorism variable, the authors have used the ‘global terrorism index’ constructed by ‘the institute of economic and peace’. Liu and Pratt (Citation2017) results show that the international tourist flow is resilient to terrorism with rapid ability to recover, e.g. the impact is only significant in the short-run.

More recently, the model has proven its superiority in capturing the nonlinear and asymmetric relationships that characterize several relationships. Compared to the Johansen and Juselius cointegration technique and the linear ARDL technique, the outperformance of the

is mainly due to the relaxation of some assumptions (the condition that all the variables should be integrated with order one or that the impact of shocks is symmetric). However, despite these advantages, only a few studies have used this model in the context of tourism (Demir et al., Citation2020; Fareed et al., Citation2018; Husein & Kara, Citation2020). For instance, Fareed et al. (Citation2018) use the

approach to analyse the asymmetric effect of terrorism on Thailand’s economic development from 1990 to 2017. The authors found that both increases and decreases in terrorist attacks negatively affect economic activity. However, Fareed et al. (Citation2018) and Husein and Kara (Citation2020) do not analyse the asymmetric effect of terrorism on tourism activity. In the second study, Husein and Kara (Citation2020) studied the impact of economic growth increases and decreases in the US on the tourism receipts in Puerto Rico over the period 1970–2016. They find robust evidence for the presence of an asymmetric impact and that a 1% rise in GDP per capita of the US results in approximately 2% improvement in Puerto Rico’s tourism receipts. In contrast, they found that a 1% drop in GDP per capita of the US induces a decline in tourism receipts by approximately 4.8%.

This research is also related to a recent study of Demir et al. (Citation2020) who examined a similar objective but with some differences. Methodologically, this study differs by adopting two proxies of the tourism demand activity, namely tourism receipts and tourists arrivals while Demir et al. (Citation2020) use the tourist arrivals variable as the only proxy of tourism demand for the case of Turkey. We believe that for the case of Turkey, where the tourism industry relies on its suitable price to tourists, tourism receipt is considered the appropriate compared to tourist arrivals as the cost is a fundamental factor in determining tourists destination (see Sun & Luo, Citation2021). Second, in our study, we distinguish between different types of shocks like terrorist attacks, health pandemic crises, and natural disasters, while Demir et al. (Citation2020) use only one index called geopolitical risks, which account for several aspects of exogenous shocks. Although the Geopolitical index is attractive, it does not help to design specific conclusion and policies. In this study, by focusing on tourism demand activity, namely tourism receipts and distinguishing between different types of shocks, our analysis provides novel evidence regarding the extent to which terrorism and significant events contribute to tourism performance failure. Third, our study uses the real effective exchange rate rather than the consumer price index used by Demir et al. (Citation2020). Using a real effective exchange rate is motivated by the fact that an exchange rate is a policy tool that policymakers can use to stimulate tourism demand activity. Finally, the absence of a significant impact of geopolitical risks decreases on the tourism demand activity in the Demir et al. (Citation2020) study can be attributed to the heteroscedasticity problem in their results.

Terrorism and other exogenous shocks

Terrorism in Turkey

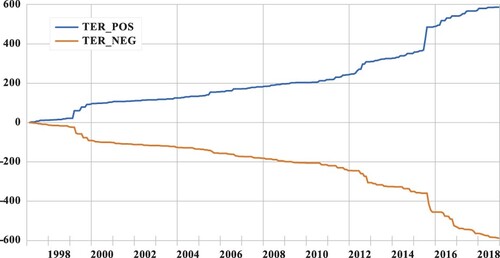

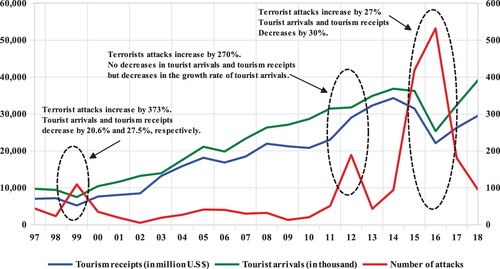

Over the last two decades, the Turkey economy, particularly its tourism industry, has suffered from several terrorist incidents (Estrada et al., Citation2018). shows a negative correlation between the number of terrorist attacks and tourist demand. also indicates that Turkey has recorded a dramatic increase in terrorist attacks in recent years, where the average of attacks raised from 33 attacks annually between 1998 and 2010 to 201 between 2011 and 2018.

Figure 1. Terrorist attacks and tourism demand evolution in Turkey over the period 1997–2018 (tourism receipts and tourists arrivals – left axis, terrorist attacks right axis).

When we looked in depth at the years driving this increase, we observed that in the first period, 1998–2010, the attacks increased five times in one year, from 24 attacks in 1998 to 109 incidences in 1999. This rise in terrorist events was viewed as a reaction of the PKK group to the arrest of their leader Abdullah Ocalan in Nairobi in 1999 (Rodoplu et al., Citation2003). A second important date is the terrorist incidents on the tourism facilities held in August 2006 in the tourist site of Marmaris, resulting in 21 injured people (Öcal & Yildirim, Citation2010). Economically, the cost of the Marmaris attack was evaluated to a decrease in international tourism arrivals from 20,273,000 million in 2005 to 18,916,000 million in 2006 and a decline in global receipts from 20,760,000 billion in 2005 to 19,137,000 billion in 2006 (World Bank, Citation2017).

During the second period, between 2011 and 2018, the number of terrorist attacks has sharply increased in 2012 to reach 189 attacks; this increase is about ten times higher than the number of attacks in 2010. More recently, 2016 recorded the highest number of terrorist attacks, which is 26 times higher than attacks in 2010. Due to this, Turkey was listed in 2016 as one of the ten countries most affected by terrorism with a very high human cost recording 658 deaths, and this accounted for 2.6% of all global deaths and 3.3% of all terrorist attacks (Global Terrorism Index, Citation2019).

Others exogenous shocks

In addition to terrorist attacks, the Turkey tourism industry has also been subject to several other human-caused disasters, such as political unrests, economic crises and or natural disasters and health crisis, all of them expected to highly hamper the tourism activity (Khazai et al., Citation2018; Sönmez, Citation1998; Steiner, Citation2007). In the current section, we present the major political instability, economic crisis, natural disaster and health crisis that have affected Turkey’s economy; see below.

Figure 2. Major terrorist attacks, political instability, financial crisis, natural disaster and health crisis affecting the Turkey economy.

Political instability

Turkey’s proximity to countries suffering from civil wars (such as Iran, Iraq, Syria) and the country’s involvement in several ongoing international disputes has significantly affected the state’s political instability and tourism activity (Öcal & Yildirim, Citation2010). Evidence for a negative association between political instability and tourism activity has been highlighted in several studies (see Ivanov et al. [Citation2017] for the case of Ukraine and Charfeddine and Goaied [Citation2019] for the case of Tunisia). For the case of Turkey, the recent political conflict with Russia due to the shot down of a Russian jet over the Syrian border in November 2015 by the Turkish air forces has badly affected the Turkey tourism sector during recent years. The increase in the political conflict between those nations drive down the decrease in Russian tourist flow to Turkey from approximately 17.82% in May 2014 and 13.17% in May 2015 to only 1.65% of the foreign tourists to Turkey in May 2016 (Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Citation2016). Political instability has also influenced the tourism industry through the bloody military coup attempt in July 2016. Such incidents damaged the tourism sector, where the tourism arrival recorded the biggest fall (40% decreases) in the last 20 years.

Economic and financial crisis

During the last two decades, Turkey has been also subject to the effects of some important exogenous financial and economic crises, like, the Asian and Russian financial crash of 1998–99, and the worldwide economic crisis of 2008–09. From an economic perspective, it is expected that these crises will negatively affect the tourism industry due to a slowdown in regional or global economic activity. These crises will result in a decline in the tourist flow due to the slowdown in the tourist-generating nations’ economic activity (Song & Lin, Citation2010; Yarcan, Citation2007). As an illustration, according to the Turkish Statistic Institute (Citation2014), the increase in the tourist flows to Turkey was 13.7% annually in the period preceding the global worldwide financial crisis (2003–2008), this growth decreased to only 4.83% annually after the crisis (2008–2013). This remarkable change is evidence of the influence of the economic crash on global tourism demand in Turkey.

Health crisis and natural disaster

Health crises and natural catastrophe disasters situations like volcanic eruption, wildfire, earthquake, tsunami, storm and health pandemics have severely affected the performance of the tourism industry (Asgary & Ozdemir, Citation2020; Park & Reisinger, Citation2010; Ritchie et al., Citation2010). Theoretically, natural catastrophes cause notable damage to the tourist infrastructure, tourist sites, cultural heritage and tourism facilities in general, which generally leads to a decrease in tourism receipts and tourist arrivals (Çetinsöz & Ege, Citation2012). Similarly, health crises or pandemics negatively affect tourism demand from or to destinations as tourists prefer safer destinations. Some of these pandemics are the ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)’ of 2003 and ‘Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)' of 2015 (Gössling et al., Citation2021). Empirically, Uzuner and Ghosh (Citation2021) documented a negative relationship between world pandemic uncertainty and tourist flow in Italy from March, 2000 to March, 2020.

The Turkish economy has also suffered from the effects of health and natural catastrophes. For instance, according to Eryiğit et al. (Citation2010), the devastating Marmara earthquake that hit Turkey in its industrial heartland on 17 August 1999 has negatively impacted Turkey’s tourist arrivals. Turkey was one of the nations critically affected by ‘the avian flu outbreaks’ from 2003 to 2007 (Kuo et al., Citation2009), leading to notable disruption in tourist flows.

Empirical methodology

Data description and data sources

Monthly data on two tourism demand proxies (tourism receipts and tourist arrivals) covering a period of 22 years, spanning from January 1997 to December 2018, are collected from the ‘Turkey ministry of culture and tourism’.Footnote3 The period of the data is restricted to December 2018 because of the non-availability of the number of terrorist attacks variable for the last two years, 2019 and 2020. Data for the terrorist attacks was taken from the ‘Global Terrorism Database’.Footnote4 For the real effective exchange rate (REER), we collect the data from the Turkey Central Bank,Footnote5 with a base of 2003 = 100. Economically, rise in REER make the exports more expensive and the imports cheaper. Consequently, rise in REER will make tourism travel to Turkey more expensive, negatively affecting the tourism demand in Turkey. We also use dummies variables to consider the significant incidents that have affected the Turkey economy, especially the tourism sector (see ). All the variables, except the dummy variables and the number of terrorist attacks, are taken in logarithm due to the existence of zeros.

The dummy variables take the value one during the events periods (political instability events, economic and financial crisis, natural catastrophes, and health crises) and zero otherwise. These dummies are constructed based on economic facts and the findings of the unit root tests with structural breaks.

The list of dummy variables for this study are described as follow:

is a dummy variable representing financial and economic crisis of 1998–2001. It takes the value one for the period between December 1998 to March 2001 and zero otherwise.

refers to the devastating earthquake of 17 August 1999. It takes value 1 for the two months of August and September 2016 and zeros otherwise.

refers to the avian influenza epidemic of January 2006 – March 2007. It takes value 1 during the avian influenza period and 0 otherwise.

refers to the period of political tensions between Russia and Turkey after the latter has shoot down a Sukhoi Su-24 warplane on 24 November 2015. This dummy variable takes the value 1 for the period of November 2015 to May 2016 and zero otherwise.

is a dummy variable that refers to the Global financial crisis. It takes the value 1 for the period from June 2007 to February 2009 and zero otherwise.

: is a dummy variable that refers to the coup d’état attempt in Turkey in July 2016. It gives 1 for the two months of August and September 2016 and 0 otherwise.

Unit root tests with abrupt and smooth structural breaks

Although the stationarity property of the different time series used in our system framework is not highly crucial for the ARDL and techniques as it should be for the case of the cointegration approach of Engle and Granger (Citation1987),Footnote6 there are some important reasons that motivate us to determine the level of integration of the different time series. One of these reasons is the necessity that all the variables are mixed I(0) and I(1) process to be able to use the

approach. A second important reason is that evidence for the existence of structural breaks will enable us to control for by using dummy variables when estimating the

model.

In this study, to save space, we limit our analysis to the use of unit root tests with structural breaks known to outperform standard unit root tests. The three-unit root tests that will be used are: (1) two-unit root tests with abrupt breaks (Kapetanios, Citation2005; Lee & Strazicich, Citation2003) and (2) a unit root tests with smooth breaks (Enders & Lee, Citation2012). The three-unit root tests considered here were chosen based on their flexibility in terms of assumptions. For instance, while the Lee and Strazicich (Citation2003) tests allow for two structural breaks under both the null and alternatives hypothesis, the Kapetanios (Citation2005) test allows for up to five breaks under the null hypothesis.

approach

approach

Besides the commonly known advantage of the non-necessity that all the variables are I(1), the model presents the advantage of being able to model the asymmetric effect of an explanatory variable on the explicative variable. In this paper, the nonlinear ARDL technique will be used to examine whether terrorist attacks increases have different impact on the tourism demand compared to terrorist’s attacks decreases.

The following subsections introduce the terrorist attacks decomposition, the form of the model, the tests for cointegration, for asymmetry in both the short-run and long-run, and the dynamic nonlinear multiplier.

Terrorist attacks decomposition

The first step of the technique implementation is the decomposition of the terrorist attacks between positive cumulative sums,

, and negative cumulative sums,

as follow,

(1)

(1) Where

is the initial value of terrorist attacks. The two partial sums (

and

)Footnote7 are defined as follow,

(2)

(2) And in a similar way

(3)

(3)

model

model

The error correction form of the model applied in our research to test the asymmetric impact of terrorist attacks on tourism activity (

) after adding the dummy variables is given by Eq. 4,

(4)

(4) Where,

(5)

(5) Where

is the tourism demand variable (proxied by tourism receipts (

) or tourist arrivals (

)).

,

and

are the explanatory variables.

is an independent and identically distributed

.

for

are dummies that are defined as in the data description section.

is the nonlinear error correction term. In this model, the parameters

,

and

represent the asymmetric long-run parameters associated to

,

and the real effective exchange rate (LREERt−1), respectively. The optimal lag is determined based on the standard information criterion’s (AIC, SC or HQ).

Long-run relationship tests

The two tests statistics employed to test for evidence of an asymmetric long-run relationship are:

- The Banerjee et al. (Citation1998) test is a t-statistic test, where the null hypothesis of no cointegration (no long-run relationship) is given by

and the alternative is

in Eq. 5.

- The Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) test, the F-statistic test used to test the joint null hypothesis

(no long-run relationship or absence of cointegration) against the alternative

in Eq. 6.

See Banerjee et al. (Citation1998) and Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) for more details about these two tests statistics and their limiting distribution.

Long- and short-run asymmetry tests

The next step after validating the existence of long-run relationship is to test for long- and short-run asymmetry. We use the two tests of asymmetry of Shin et al. (Citation2014),

The long-run asymmetry test: the null hypothesis of absence of asymmetry in the long-run is given by

against the alternative

.

The short-run asymmetry test: Similar to previous studies, we use the restrictive additive caseFootnote8 under which the hypothesis of asymmetry is

, here

is the optimal lag length.

Dynamic nonlinear multipliers

The dynamic nonlinear multipliers is an important feature of the NARDL approach since it provides the adjustment behaviour pattern of the asymmetry impacts towards the final new equilibrium following a shocks (terrorists attacks) on the dependent variable (tourist demand).

The dynamic nonlinear multipliers related to a unit changes in and

, are defined by,

(6)

(6) It is easy to show that both

and

converge, as

, to

and

, respectively (see Shin et al., Citation2014).

Results and discussion

Preliminary analysis

This section provides a first preliminary analysis of the tourism receipts, number of tourist arrivals, terrorist attacks, and real effective exchange rate time series based on the series trajectories, the descriptive statistics and the analysis of the stationarity property.

Graphical analysis

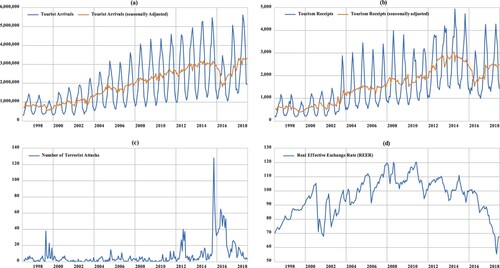

(a)-(d) report the evolution of the tourism demand series along with their seasonally adjusted series,Footnote9 the number of terrorist attacks and the real effective exchange rate from January 1997 to December 2018. The trajectories of the four variables show evidence for some important statistical properties such as seasonality, trends and structural breaks. The analysis of the two tourism demand series shows that the significant decrease in the tourism receipts and the number of tourist arrivals coincide with the escalation of terrorist incidents and other important events. For instance, between April and August 1999 a significant fall in tourism receipts and tourist arrivals was characterized. This period includes some months with many terrorist attacks, such as 38 attacks in April 1999, 23 attacks in August 1999 and includes the earthquake of 17 August 1999. The second period was characterized by a significant decline in the tourist flow for 17 months, from August 2015 to December 2016, where the total number of terrorist attacks reached 890, with a monthly average of 64 attacks. This number of incidents corresponds to around 43% of the total terrorist attacks of our sample (2061).

Figure 3. Trajectories of Tourism demand proxies (tourist’s receipts and tourism arrivals), terrorist attacks and real effective exchange rate.

Regarding the partial sums of the terrorist attacks variables, the chart lines reported in show clear evidence for both upward and downward trends, respectively.

Descriptive statistics and graphical analysis

Descriptions of the series are reported in in non-logarithmic form. The results show that all the variables’ mean and median are quite similar except for the terrorist attacks variable (mean = 7.832 and median = 3), meaning that only this variable is characterized by outliers (for example, a maximum = 128 attacks in August 2015).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (seasonally adjusted).

also shows that terrorist attacks have the highest variability since its standard deviation value is approximately equal to two times the mean value compared to the other series. The two tourism demand proxies show similar values of a standard deviation when compared to their mean values (approximately half of the mean). The lowest variability is found for the real exchange rate when the standard deviation is compared to its mean value. The skewness, kurtosis and Jarque Bera statistic show that the normal distribution is rejected for all four series.

Unit root tests with structural breaks

The three-unit root tests with structural breaks considered in our study for both the series in level and first differences are displayed in . Columns 2 and 3 of present the LM statistic of the Lee and Strazicich (Citation2003) unit root tests and the two breaks dates. We find that all the series are non-stationary in level, except the real effective exchange rate. Taken in their first difference, we find all the series are stationary significant at the 1% level. Regarding the break dates, some common dates appear for almost all the series, such as the year 2016. Others breaks correspond to the year 2003, 2012 and 2015.

Table 2. Results of unit root tests with abrupt and smooth structural breaks.

As a result of Kapetanios (Citation2005) unit root tests, we could not reject the null hypothesis of unit root except for the positive partial sum of terrorist attacks. The null hypothesis is highly rejected in the first difference, e.g. 1% level. A result indicates the stationarity of all the series in the first difference. Compared to the Lee and Strazicich (Citation2003) results, the Kapetanios (Citation2005) results show evidence for the existence of several breaks. For instance, the two-tourism demand proxies have two common breaks dates, the first corresponds to the year 1999 (August for tourist arrivals and September for tourism receipts) and the second to the year 2016 (July for the tourist arrivals and June for the tourism demand). These two breaks coincide with the earthquake of the year 1999 and the Turkey coup d’état of 2016. For the two partial terrorist attacks series, the results also show evidence for some common breaks, such as the year 1999 and the year 2016.

Finally, using the Enders and Lee (Citation2012) unit root, the results show with clear evidence that the first difference is enough to make the series stationary. However, the unit tests do not provide a specific date for the considered breaks.

To summarize, two important conclusions can be drawn from the findings of unit root with structural breaks. First, all the series are either I(0) or I(1), which allow us to use the approach. Second, the results show evidence for the existence of structural breaks in almost all the series that coincide with important political instability, economics and financial crisis, and natural disasters crisis. Moreover, the strong evidence for several structural breaks in the examined time series can be considered as an important preliminary indication for a possible asymmetry in the tourism-terrorism nexus.

validation

validation

An important step for analyzing the tourism-terrorism nexus is to find out whether the relationship is symmetric or asymmetric. The results of the and

tests for testing for both symmetrical (linear ARDL) and asymmetrical (nonlinear ARDL) effects of terrorist attacks on tourism demand series are reported in . The results indicate that the null hypothesis of absence of cointegration cannot be rejected whatever the proxy of the tourism demand used for the case of the linear ARDL model. In contrast, when testing for the existence of an asymmetric (non-linear) cointegration, the findings show that the null hypothesis of absence of cointegration is highly rejected. These findings shows that terrorists’ attacks increases and decreases have a different impact of tourism demand.

Table 3. Long-run relationship tests results.

However, it is important before estimating the model to test for the existence of long- and short-run asymmetries. The results of testing for these two types of asymmetry using the Wald tests are reported in Panel B of . Regarding tourism receipts, the results show strong evidence for asymmetry in the long- and short-run since the calculated Wald tests statistics are greater than the critical values at 1% level of significance, e.g.

with

for the long-run asymmetry and

with

for the short-run asymmetry. The results of tourist arrivals also show strong evidence for asymmetry in long-run,

with

and absence of asymmetry in short-run,

. For results replication motives, we report the unrestricted

model for both cases.

The results show that the estimated two unrestricted models pass successfully all the standard diagnostic tests of serial correlations (BG test), heteroscedasticity (White test), and of functional form misspecification (RESET test).

Finally, our two models have passed the two tests of coefficients stability, the CUSUM and squared CUSUM tests (see ). We find that for both cases and both tests the blue line fall into the two % critical values. To save space, we report only the results for the tourism receipts case.

NARDL interpretations and discussion

The estimation results of the long- and short-run asymmetry relationship are presented in Panel A of columns 2–3 for tourism receipts and columns 6–7 for tourist flow. In the case of tourism receipts, the long-run coefficients associated to terrorists attacks increases and decreases are highly significant and have the negative expected sign, e.g. and

, respectively. For tourist arrivals, the impact of terrorist attacks increases and decreases are also negative but only significant at 10% and 5% respectively, e.g.

and

. The results show that an increase of terrorist attacks by 1 attack will induce a decrease of 2.3% in monthly tourism receipts and 2.62% in monthly number of tourist arrival, and vice versa. Our results regarding the impact in the long-run of terrorist attacks increases are consistent with Balli et al. (Citation2019) and Demir et al. (Citation2020), who use the geopolitical risks index rather than terrorist attacks. In contrast, our findings significantly differ from that of Demir et al. (Citation2020) when analysing the effect of terrorist attacks decreases on tourism demand. While we find strong evidence for a substantial effect of the decreases in the number of terrorism incidents on tourism demand, Demir et al. (Citation2020) failed to find, a substantial effect of geopolitical risks decrease on tourism demand. This latter result may due to the heteroscedasticity problem in their final selected model.

Table 4. NL-ARDL estimation results.

The results of the asymmetric impact of terrorist attacks on tourism demand show that in terms of magnitude, the effect is much higher (in absolute value) for the case of terrorist attacks decreases than terrorist attacks increases. This result indicates a rapid recovery of the Turkey tourism sector following a decrease in terrorist attacks. Although this result seems counter-intuitive, since negative shocks (terrorist attacks increases) have a higher impact than positive shocks (terrorist attacks decreases), several reasons can explain this result. First, the adoption of a strategy of mass tourism development by Turkish policy makers provides a reasonable explanation of why the response of the Turkey tourism sector is higher following terrorist attacks decreases compared to terrorist attacks increases (see Egresi, Citation2016). It is possible to explain this because tourists choosing charter flights and mass tourism destinations are generally less sensitive to media reports on terrorism in some tourist destinations, including Turkey. A second possible explanation is that Turkish policy makers react rapidly with strong policies after terrorist attacks, such as providing important supports and attractive products to increase the demand for Turkey tourism destinations.

The results for the REER variable show that the real effective exchange rate is a key determinant of the tourism demand. The positive sign of the coefficient associated with the REER variable indicates that an increase in REER will positively affect both the tourism receipts and tourist arrivals. A similar finding of a positive effect of the REER on the tourism demand variables was found in several other studies including, Kılıç and Bayar (Citation2014). A possible explanation for the non-expected sign is that the main trade partners of Turkey differs from the main tourist’s generators countries.

In addition to the long-run results, Panel A2 of reports the results of the short-run part of the model, we found that the estimated coefficient of the speed of adjustment has its expected negative sign and it is highly significant, e.g. −0.1345 (

) and −0.1178 (

) for the tourism receipts and tourist arrivals cases, respectively. The finding here indicates evidence for the existence of a dynamic adjustment of tourism receipts and tourist arrivals that will eventually bring them to their long-run steady states with a half-time estimate of 4.8 months for tourism receipts and 5.5 months for tourism arrivals.

Panel A2 also shows the results of the short-run impact of terrorist attacks increases and decreases, the real effective exchange rate (in first difference) and the results for the dummy variables. The results show that almost all the coefficients are significant at 5% and consistent between the two tourism demand proxies. Overall, all the significant variables have their expected sign except for the positive sign of the coefficients associated with the lags of the positive changes in terrorist attacks. The explanation of this result is that Turkish tourists have a very short memory of the attacks prevailing in the last months and are confident that Turkey policy makers policies will make their stay safer after a period of terrorist attacks.

Finally, regarding the impact of the one-off dummy variables, we found that the two dummies associated with the economic and financial crisis of 1998 and the recent political tension between Turkey and Russia have a significant negative effect on the tourism receipts indicator. For the tourist arrivals indicator, in addition to the two events affecting the tourism receipts, we found that the bloody attempted military coup in July 2016 has had a significant negative effect on tourism demand. However, our empirical findings do not show evidence for a significant impact of the global financial crises on the two tourism demand proxies.

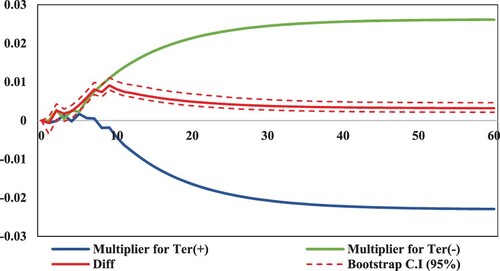

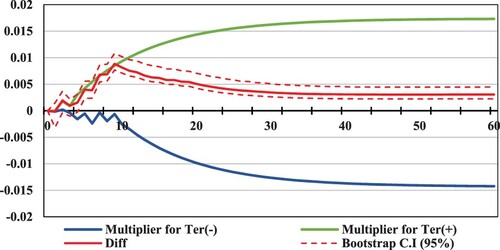

Dynamic multipliers

The dynamic multipliers for up to 60 months (5 years) are reported in and for the tourism receipts and tourist arrivals series, respectively. In both figures, the heavy solid red line explains the difference between the impact on the tourism receipts of an increase terrorist attacks by one attack and the effect of a decrease in terrorist incidents by one attack. The thin dashed red lines report the confidence interval for the different effects in both figures.

shows that the response of the tourism receipts following a terrorist attacks increase remains almost positive but close to zero during the first sixth months, however, it changed to negative starting from the beginning of the seventh month. This result indicates that, in the short-run, the response of tourism receipts to positive terrorist attacks increases is weak. However, following a decline in the number of terrorist attacks, the response of tourism receipts is positive for the whole period. In terms of the difference in impact, the results show that the difference is positive and significant with the beginning of the fourth month. A result, which indicates that the reaction of the tourism receipts following a decrease in terrorist attacks decreases, is much higher, in absolute value, than the reaction following terrorist attacks increases (negative shock). We also notice that the multipliers (following positive and negative shock) take approximately 30 months to converge to its long-run multipliers. Accordingly, this result can be viewed as evidence for the resilience of the Turkish tourism sector to such types of shocks.

Conclusion and policy implications

This article examines the resilience of the Turkey tourism industry to exogenous shocks by exploring the evidence for the existence of asymmetrical effect of terrorist attacks on tourism demand. Precisely, we use the technique over the period from January 1997 to December 2018 to investigate whether the terrorist attacks in Turkey have a significant asymmetric impact on the tourism receipts and tourist arrivals in both the short-run and long-run, and this after controlling for fundamental factors and non-fundamental factors (political violence, economic and financial crises, health crises and natural disasters).

The analysis of the statistical properties of the different variables in our system shows strong evidence that all the variables are integrated with a first-order or stationary level. Interestingly, the results show evidence for several structural breaks in all the time series, indicating the possible existence of an asymmetry in the tourism-terrorism relationship. The breakpoints’ identification shows that they correspond to specific events like the economic and financial crisis of 1998, the earthquake of 1999, the Russia-Turkey tension of 2016 and the bloody attempted military coup.

Testing for symmetric and asymmetric long-run relationships show that the symmetric linear ARDL model cannot capture the non-linear dynamic between tourism demand and terrorist attacks, whatever the proxies of tourism demand are used. However, by allowing for the possible asymmetry, the results reveal the hypothesis of asymmetric relationship cannot be rejected. In particular, our analysis shows that the effect of terrorist attacks decreases is significantly higher than terrorist attacks increases.

The results of this paper have several important policy implications. First, the surprising fact that decreases in terrorist attacks affect tourism demand more than increases in terror attacks (in absolute value) is beneficial for the Turkey policy makers and government when designing economic strategies to establish rapid recovery after a period of high terrorist activity. The result suggests that any efforts from governments to control terrorist activities will be positively seen by tourists and will ensure a rapid recovery process of the tourism activity. Hence, the government and policymakers should maintain their efforts and strategies to manage such crises to give a feeling of safety to potential tourists. Second, the results indicate that the political party in power should thoughtfully and carefully consider political instability, mainly with tourism partners, because of its high effects on the tourism demand. Third, the results indicate that policy makers can use the exchange rate policy in the short-run to stimulate tourist arrivals and increase tourism receipts.

In addition, the results of this study are also helpful for academics because they help fill a gap in the literature in analysing the influence of terrorist activity on tourism demand in different nations, especially for tourism-dependent countries and which are more susceptible to terrorist incidents. Despite the important findings of this research and their implications, this study are subject to limitations that need to be examined in future studies. This study focuses on a single country. Future research could usefully examine tourism-terrorism nexus cross-countries; this could improve the analysis and allow for a more generalized results and may help us infer further on this matter. Constructing a REER as a weighted nominal exchange rate, multiplied by the ratio of a harmonized index of consumer prices for restaurants and hotels of the tourist generator countries and its corresponding harmonized consumer prices in the tourist destination country is another way to improve this study. We leave these potentially important issues as future research topics.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lanouar Charfeddine

Lanouar Charfeddine, Ph.D, is an Associate Professor in Economics in the College of Business and Economic at Qatar University. He got a Ph.D in economics, applied econometrics, and two master research in international trade, and finance and econometrics from University Paris II, France. Dr. Charfeddine research interests include the macroeconomic impact of terrorism, terrorism and tourism, innovation in tourism, entrepreneurship and financial inclusion, and energy economics. He has published more than 40 articles in peer-review journals. His research was funded by several national and international grants.

Issa Dawd

Issa Dawd, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in Accounting in the College of Business and Economic at Qatar University. He was awarded his PhD in Accounting and Finance from the University of Dundee (UK). Dr. Dawd's research interests include financial accounting/reporting, measuring corporate disclosure quality and quality, determinants of disclosure, corporate governance, international accounting standard, emerging market, financial innovation, terrorism and tourism performance, innovation in tourism and the innovation types and organisations/market performance and have published articles in international journals in these and related fields.

Notes

1 Mixed results on this issue have been presented in the existing literature. Abadie (Citation2006) reported that the impact of ethnic multiracialism on the terrorism risk is insignificant, whereas Bravo and Dias (Citation2006) found a negative association between ethnic multiracialism and several terrorist incidents.

2 World Tourism Ranking.

6 In the model the series can be a mixture between I(1) and I(0) processes. However, they should be all I(1) for the Engle and Granger (Citation1987) approach.

7 We found no dominance of either positive or negative values of the terrorist attacks.

8 Another way to conduct the test is to test for all

in

9 The use of the TRAMO/SEATS technique is known to outperform other existent techniques when the tourism demand series are subject to irregularities such as the existence of structural breaks (see Charfeddine & Goaied, Citation2019).

References

- Abadie, A. (2006). Poverty, political freedom, and the roots of terrorism. American Economic Review, 96(2), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282806777211847

- Alqaralleh, H. (2020). On the asymmetric response of the exchange rate to shocks in the crude oil market. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 14(4), 839–852. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJESM-10-2019-0011

- Araña, J. E., & León, C. J. (2008). The impact of terrorism on tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.08.003

- Asgary, A., & Ozdemir, A. I. (2020). Global risks and tourism industry in Turkey. Quality & Quantity, 54(5-6), 1513–1536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00902-9

- Balli, F., Uddin, G. S., & Shahzad, S. J. H. (2019). Geopolitical risk and tourism demand in emerging economies. Tourism Economics, 25(6), 997–1005. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619831824

- Banerjee, A., Dolado, J., & Mestre, R. (1998). Error-correction mechanism tests for cointegration in single-equation framework. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 19(3), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9892.00091

- Bassil, C., Saleh, A. S., & Anwar, S. (2019). Terrorism and tourism demand: A case study of Lebanon, Turkey and Israel. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1397609

- Bodman, P. M. (2001). Steepness and deepness in the Australian macroeconomy. Applied Economics, 33(3), 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840122115

- Bravo, A. B. S., & Dias, C. M. (2006). An empirical analysis of terrorism: Deprivation, Islamism and geopo-litical factors. Defence and Peace Economics, 17(4), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690500526509

- Çetinsöz, B. C., & Ege, Z. (2012). Risk reduction strategies according to demographic features of tourists: The case of Alanya. Anatolia: Turizm Arastirmalari Dergisi, 23(2), 159–172.

- Charfeddine, L., & Barkat, K. (2020). Short- and long-run asymmetric effect of oil prices and oil and gas revenues on the real GDP and economic diversification in oil-dependent economy. Energy Economics, 86, 104680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104680

- Charfeddine, L., & Goaied, M. (2019). Tourism, terrorism and political violence in Tunisia: Evidence from Markov-switching models. Tourism Management, 70, 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.002

- Chesney, M., Reshetar, G., & Karaman, M. (2011). The impact of terrorism on financial markets: An empirical study. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(2), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.07.026

- Corbet, S., O’Connell, J. F., Efthymiou, M., Guiomard, C., & Lucey, B. (2019). The impact of terrorism on European tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.012

- Cunado, J., Gil-Alana, L. A., & de Gracia, F. P. E. (2008). Fractional integration and structural breaks: Evidence from international monthly arrivals in the USA. Tourism Economics, 14(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000008783554884

- Demir, E., Simonyan, S., Chen, M. H., & Marco Lau, C. K. (2020). Asymmetric effects of geopolitical risks on Turkey’s tourist arrivals. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.04.006

- Egresi, I. (2016). Tourism and sustainability in Turkey: Negative impact of mass tourism development. In I. Egresi (Eds.), Alternative tourism in Turkey (pp. 35–53). Springer.

- Enders, W., & Lee, J. (2012). A unit root test using a Fourier series to approximate smooth breaks. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 74(4), 574–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2011.00662.x

- Engle, R., & Granger, C. (1987). Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation and testing. Econometrica, 55(2), 251–276. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913236

- Eryiğit, M., Kotil, E., & Eryiğit, R. (2010). Factors affecting international tourism flows to Turkey: A gravity model approach. Tourism Economics, 16(3), 585–595. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000010792278374

- Estrada, M. A. R., Park, D., & Khan, A. (2018). The impact of terrorism on economic performance: The case of Turkey. Economic Analysis and Policy, 60, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2018.09.008

- Fareed, Z., Meo, M. S., Zulfiqar, B., Shahzad, F., & Wang, N. (2018). Nexus of tourism, terrorism, and economic growth in Thailand: New evidence from asymmetric ARDL cointegration approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(12), 1129–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1528289

- Feridun, M. (2011). Impact of terrorism on tourism in Turkey: Empirical evidence from Turkey. Applied Economics, 43(24), 3349–3354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036841003636268

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- GTI. (2019). Global terrorism index (2019). http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2019/11/GTI-2019web.pdf

- Hadi, D., Katircioglu, S., & Adaoglu, S. (2020). The vulnerability of tourism firms’ stocks to the terrorist incidents. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(9), 1138–1152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1592124

- Husein, J., & Kara, S. (2020). Nonlinear ARDL estimation of tourism demand for Puerto Rico from the USA. Tourism Management, 77, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103998

- Ivanov, S., Gavrilina, M., Webster, C., & Ralko, V. (2017). Impacts of political instability on the tourism industry in Ukraine. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 9(1), 100–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2016.1209677

- Johansen, S., & Juselius, K. (1990). Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration with application to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 52(2), 169–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.1990.mp52002003.x

- Kandemir Kocaaslan, O. (2019). Oil price uncertainty and unemployment. Energy Economics, 81, 577–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2019.04.021

- Kapetanios, G. (2005). Unit-root testing against the alternative hypothesis of up to m structural breaks. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 26(1), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9892.2005.00393.x

- Khazai, B., Mahdavian, F., & Platt, S. (2018). Tourism recovery scorecard (TOURS) – Benchmarking and monitoring progress on disaster recovery in tourism destinations. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 27, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.039

- Kılıç, C., & Bayar, Y. (2014). Effects of real exchange rate volatility on tourism receipts and expenditures in Turkey. Advances in Management and Applied Economics, 4(1), 89–101.

- Kuo, H. I., Chang, C. L., Huang, B. W., Chen, C. C., & McAleer, M. (2009). Estimating the impact of Avian Flu on international tourism demand using panel data. Tourism Economics, 15(3), 501–511. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000009789036611

- Lee, J., & Strazicich, M. C. (2003). Minimum Lagrange multiplier unit root test with two structural breaks. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4), 1082–1089. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465303772815961

- Lin, V., Liu, A., & Song, H. (2015). Modeling and forecasting Chinese outbound tourism: An econometric approach. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(1-2), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.986011

- Liu, A., & Pratt, S. (2017). Tourism’s vulnerability and resilience to terrorism. Tourism Management, 60, 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.001

- Öcal, N., & Yildirim, J. (2010). Regional effects of terrorism on economic growth in Turkey: A geographically weighted regression approach. Journal of Peace Research, 47(4), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310364576

- Park, K., & Reisinger, Y. (2010). Differences in the perceived influence of natural disasters and travel risk on international travel. Tourism Geographies, 12(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903493621

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Pizam, A., & Smith, G. (2000). Tourism and terrorism: A quantitative analysis of major terrorist acts and their impact on tourism destinations. Tourism Economics, 6(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000000101297523

- Polyzos, S., Papadopoulou, G., & Fotiadis, A. (2021). Determining terrorism proxies for the relationship with tourism demand: A global view. Tourism Analysis. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354221X16186299762089

- Polyzos, S., Papadopoulou, G., & Xesfingi, S. (2021). Examining the link between terrorism and tourism demand: The case of Egypt. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2021.1904965

- Raza, S. A., & Jawaid, S. T. (2013). Terrorism and tourism: A conjunction and ramification in Pakistan. Economic Modelling, 33, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2013.03.008

- Ritchie, J. R. B., Amaya Molinar, C. M., & Frechtling, D. C. (2010). Impacts of the world recession and economic crisis on tourism: North America. Journal of Travel Research, 49(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509353193

- Rodoplu, U., Arnold, J., & Ersoy, G. (2003). Terrorism in Turkey: Implications for emergency management. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 18(2), 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00000285

- Samitas, A., Asteriou, D., Polyzos, S., & Kenourgios, D. (2018). Terrorist incidents and tourism demand: Evidence from Greece. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.005

- Shin, Y., Yu, B., & Greenwood-Nimmo, M. (2014). Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In R. C. Sickles, & W. C. Horrace (Eds.), Festschrift in honor of Peter Schmidt (pp. 281–314). Springer.

- Song, H., & Lin, S. (2010). Impacts of the financial and economic crisis on tourism in Asia. Journal of Travel Research, 49(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509353190

- Song, H., Lin, S., Witt, S., & Zhang, X. (2011). Impact of financial/economic crisis on demand for hotel rooms in Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 32(1), 172–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.006

- Sönmez, S. F. (1998). Tourism, terrorism and political instability. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(2), 416–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00093-5

- Sönmez, S. F., & Graefe, S. (1998). Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 112–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00072-8

- Steiner, C. (2007). Political instability, transnational tourist companies and destination recovery in the Middle East after 9/11. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 4(3), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530701733421

- Sun, Y., & Luo, M. (2021). Impacts of terrorist events on tourism development: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 109634802098690. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020986903

- Turkish Statistic Institute. (2014). Tuketim Harcamalari, Yoksulluk ve Gelir Dagilimi: Sorularla Resmi Istatistikler Dizisi-6. www.tuik.gov.tr/IcerikGetir.do?istab_id=156.

- Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. (2016). Number of arriving-departing visitors, foreigners and citizens, Issue 5.

- UNWTO. (2018). Compendium of tourism statistics, data 2010–2017, 2018 Edition.

- UNWTO. (2020a). Covid-19: Putting people first. https://www.unwto.org/tourism-covid-19

- UNWTO. (2020b). Impact assessment of the COVID-19 outbreak on international tourism. https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism

- Uzuner, G., & Ghosh, S. (2021). Do pandemics have an asymmetric effect on tourism in Italy? Quality & Quantity, 55(5), 1561–1579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01074-7

- WTTC. (2019). Travel & Tourism Global Economic Impact & Trends. https://ambassade-ethiopie.fr/onewebmedia/Tourism-WTTC-Global-Economic-Impact-Trends-2019.pdf

- World Bank. (2017). International tourism, arrivals and receipts for travel items. Retrieved October 21, 2019, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.TVLR.CD?locations=TR

- Yarcan, S. (2007). Coping with continuous crises: The case of Turkish inbound tourism. Middle Eastern Studies, 43(5), 779–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263200701422691