ABSTRACT

Discursive, netnographic and visual methods have been applied in the past to critique self-images, providing insight into the behaviours of tourists. However, such studies have ignored reactions to self-image posts on social media, and particularly to those that are captured within sites of atrocity. Based on an analysis of Instagram, and drawing on Scheurich’s grid of social regularities, this article critiques the practice of digilantism, coding the identity variables that shape punitive attitudes towards perceived morally transgressive behaviour at Holocaust tourism sites. We propose that the presence and richness of visitor interpretation shapes the extent to which self-images are consciously organised, and where respectful consumption is deemed important, behavioural expectations should be communicated to visitors. We suggest there is a need for greater recognition that visitor behaviours are challenging to enforce, particularly in the backdrop of a public culture that embraces self-images, and the practice of sharing on social media.

Introduction

This article examines dark tourism visitor practices, focusing on the social surveillance of Holocaust-memorial-site tourist selfies posted on Instagram. In netnographic analysis (Kozinets, Citation2015), we apply Scheurich’s (Citation1997) grid of social regularities, introduced in our methodology section, to understand a corpus of social media imagery and user-generated comment-responses to the sample of discrete posts that this comprises of. This data set allows for insights into the discursive treatment of Holocaust memorial selfies as examples of morally contested, transgressive visitor behaviours. We offer an empirical-conceptual account of the formation and negotiation of social regularities, taking the debate around visitor behaviours at Holocaust memorial spaces beyond the binary of acceptable-unacceptable. Instead, we propose a framework that complexifies this space, drawing on context, phenotypical and other identity factors, contested readings of selfie-taking, and textual identity performances undertaken in social media captions and comments.

This contribution matters because such liminal social borderlands generate scholarly insights into how online social life works. In this case, tourists’ online rule-breaking – and interlocutors’ discursive negotiation of acceptability – appear to be mediated through identity factors including age, gender, lingua-culture, conventional attractiveness, and cultural capital as displayed in captions. In addition, the location and nature of particular Holocaust memorial sites affect behavioural appropriateness as it is negotiated. Our article develops Volo and Irimiás’ (Citation2021) observation that the growing availability of rich visual datasets shapes our understanding of tourists’ behaviour, preferences, and creative interpretations of place meaning. We extend Volo and Irimiás’s work, contributing the first scholarly engagement with social media users’ response-comment-reactions to Holocaust tourism selfies, and noting the implications for inter-tourist social regularities.

The study is motivated by recent cultural projects and debates that have been mobilised in pursuit, implicitly, of a dividing line between binary ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ behaviours at Holocaust memorials and tourism sites. Key amongst these is Yolocaust, a digital project curated by Israeli-German artist Shahak Shapira (Citation2017). This project took the form of a website that documented the artist’s objection to selfie-taking and disrespectful captioning at the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. Specifically, Shapira layered modern-day selfies (such as people juggling, running, and playing at the Berlin memorial) with historical images from Nazi extermination camps (e.g. piles of dead bodies; prisoners crowded together in bunks). The resulting juxtaposed images were his means of challenging – and shaming – the original selfie-posters, not least because some of the captions were inarguably disrespectful (e.g. ‘jumping on dead Jews’ accompanied a picture of two young men leaping between stone blocks of the Berlin memorial). Shapira’s project attracted much media coverage, and all twelve of those whose selfies were represented contacted Shapira to apologise, and ask that their photo be removed. As a result, the Yolocaust website no longer contains images. Instead, it documents the project, the social media posters’ and others’ engagements with its message. The effect, however, is ongoing. Some – but by no means all – selfie-taking at Holocaust memorial sites still attracts critical responses on social media. Research has yet to engage with how user-generated captions and viewer-generated comments work intertextually with social media selfies to produce and mediate ‘social regularities’ of behaviour in such touristic spaces. This paper addresses that gap.

Yolocaust – and online digilantism in its wake – represent a condemnation of certain practices, in particular the taking and sharing of Holocaust-memorial-site selfies on social media. Although selfie-taking may be viewed as narcissistic and careless, such behaviour may be constructed and performed as a legitimate means of (per-)forming a connection with experience (Gannon & Prothero, Citation2016). We therefore problematise perspectives on meaning-making, arguing that ostensibly ‘deviant’ visitor behaviours may be readable as examples of Debord’s psychogeography: playful navigation of urban environments in ways that are not always consciously organised. Engagement with emotionally challenging spaces, we propose, is a rich site of identity construction in which narrative identities are proposed and negotiated against a foil of socially sanctioned rules and extant scripts.

We begin by interrogating the concepts of social order and identity-as-ever emergent and as performance, discussing the construction of otherness and the differential treatment of Holocaust-memorial visitors who transgress the ‘social regularities’ of respect, humility, solemnity, and deference which appear to have crystallised into an explicit set of expectations that visitors have of each other (see Wight, Citation2020). Next, we explore the construct of selfies in Holocaust tourism before considering digilantism (online vigilante activity). We then analyse a sample of social media entries (i.e. users’ selfies and captions) and critically interrogate user-viewers’ responses. Together, these allow us to construct a framework of social regularities as identity work.

Theoretical background

Tourism selfies and identity as performance

Image-rich social media sites such as Instagram are increasingly regarded as legitimate sources of social scientific data in tourism research. Such data sources provide insight into destination image as well as the behaviour and experiences of tourists (Volo & Irimiás, Citation2021). Visual ‘evidence’ is fundamental to tourism, since part of the motivation to travel is to collect images to understand destinations and attractions as sights (Dinhopl & Gretzel, Citation2015). Selfies – self-portrait photographs, usually captured on a smartphone and shared via social media – have come to dominate expressions of tourism consumption, existing at the intersection of multiple assemblages which ‘connect disparate modes of existence into one simple act’ (Hess, Citation2015, p. 1629).

Selfies are not necessarily taken by the subjects of photographs; they can be shot by anyone, in or out of the frame. The defining feature is that the selfie centres the individual, as opposed to the background (the site or experience) and represents a form of self-presentation typically shared with online audiences (Dinhopl and Gretzel, Citation2015; Kozinets et al, Citation2015). For this reason, selfie-taking/sharing provides evidence of a culture of self-obsession, particularly among young people (Murray, Citation2015). As digital technology has become more powerful, and more portable, the ways in which we self-express and articulate/negotiate a connection with others have also fundamentally changed. The practice of sharing images, in tourism particularly, has come to represent a modality of visual conversation, and image-centric social media platforms such as Instagram and Snapchat are prolific in terms of usage and cultural importance (Tiidenberg & Cruz, Citation2015).

In their analysis of identity, Lindgren and Wahlin (Citation2001, p. 359) emphasise reflexivity, noting that identities are not fixed but are ‘continually socially constructed and subject to contradictions, revisions, and change’. As Erin Manning (Citation2013, p. 17) notes:

Identity is less a form than the pinnacle of a relational field tuning to a certain constellation. … The point is not that there is no form-taking, no identity. The point is that all form-takings are complexes of a process ecological in nature. A body is the how of its emergence, not the what of its form.

A body is a complex activated through phases in collision and collusion, phasings in and out of processes of individuation that are transformed – transduced – to create new iterations not of what a body is but of what a body can do. What we tend to call “body” and what is experienced as the wholeness of form is simply one remarkable point, one instance of a collusion materializing as this or that.

Holocaust visitor attractions and selfies

There are at least two threads of argumentation in the literature on the issue of selfie-taking and selfie-sharing on social media sites where the physical context is a Holocaust memorial or visitor attraction. On the one hand, it is useful to trace the emergence of collective cultural anxieties about how others behave at Holocaust heritage sites. Previous research has noted how a code of ethics appears to be hardening around what counts as morally acceptable behaviour within such spaces. The selfie is often at the heart of these anxieties, as evidenced in reflective Holocaust-tourism visitor narratives that amass on travel review websites (Wight, Citation2020). Indeed, such cultural anxieties seem to centre on specific types of selfies – cute, interactionist, or model-like, for instance (Pearce & Wang, Citation2019) – which may add a sense of individuality and uniqueness to the image, and render it more worthy of sharing, but which may also make it seem more self-centring and less memory-respecting. It is conceivably these types of behaviours, rather than simply the idea of selfie-taking at Holocaust sites, that generate moral objections and a perceived sense of harm being done. For this reason, those who post selfies from Holocaust memorial sites – particularly those in which they are seemingly not following the ‘rules’ of respect, humility, solemnity, and deference – may be subject to public shaming (e.g. Moss, Citation2014). There is, however evidence in recent literature (see Wight, Citation2020) that some visitors to Holocaust heritage sites oppose all selfie-taking, regardless of the intention, and type of pose.

A second line of thinking is that the selfie is a contemporary, normalised form of social currency: a commonplace form of cultural expression. A selfie at a Holocaust memorial site might seem the ideal opportunity to communicate a meaningful, felt connection with a unique physical space. Indeed, the normalcy of selfies as disposable snapshots of everyday life, consumption, and identity work is accentuated by their emergence in all corners of social life. The act of taking a selfie – whether at a Holocaust memorial site, or a museum, or any other setting – may be about having a moment of agency, connection, and self-expression, in which one constructs, maintains and adapts a sense of personal identity. Kozinet’s et al. (Citation2015) note how museums serve as a stage for the embodied self, and that taking selfies is perhaps a way of consuming and making sense of museums: a way to record an experience, and a means to frame what is seen in artistic and creative ways. This engagement function of selfies does not seem to be restricted to museums since social media and mobile devices can play a similarly experience-enhancing role in the consumption of dark tourism spaces. However, as the section below identifies, selfie-taking at visitor attractions themed around tragedy, death and suffering remains contentious, and is beginning to be ‘punished’ on social media spaces where selfies are shared.

Digilantes and digilantism

Citizens have always taken justice ‘into their own hands’ (Reichl, Citation2019). For example, the townships of South Africa, during the political violence of the late 1980s and early 1990s, played host to acts of community vigilantism enforced by People’s Courts. So-called ‘necklace’ executions, in which a rubber tyre is placed over the collaborator’s head and set alight, came to symbolise this era of unrest (Minaar, Citation2001). Social media has served to further enable this kind of mob justice, not least as ‘misbehaviour’ is more widely visible online, but also because ‘punishment’ can be extremely swift, widespread, and anonymous. While in the offline world, the unauthorised enforcement, investigation, and/or punishment of perceived offenses is referred to as vigilantism, the online equivalent is digilantism, carried out by digilantes.

One key distinction between digilantism and vigilantism is the largely non-material nature of the former’s ‘punishment’, which occurs in digital settings. However, the practice of ‘doxing’ – the act of revealing targets’ private information (i.e. ‘documents’, hence ‘dox’) such as address or bank account details – blurs the sharpness of this division, as doxing results in offline reprisals for online ‘offences’ (Trottier, Citation2020). However, most digilantism occurs online, involving trickery, persuasion, reputation assaults, harassment – including rape or death-threats, and public shaming. This is not to say that no harm occurs, but rather to underscore the distinction between the material harms of vigilantism and the largely psychological harms of digilantism.

While digilantism has not yet been researched in relation to Holocaust-tourism selfie-taking, orientation can be taken from recent research on digilante activism in other areas. Trottier (Citation2020) cites the Russian group Lev Protiv, which shames seemingly intoxicated people, and Gamergate, a right-wing digilante campaign from 2014 against feminist activists who called out sexism in video game culture; it used public shaming as well as doxing, rape threats and death threats. Jane (Citation2017) explores feminist digilantism as a response to ‘slut-shaming’ on Facebook, noting the benefits – such as raising public consciousness and humanising victims – as well as the risks and disadvantages – the activists themselves often face retribution – of digital activism. At a conceptual level, Gerbauda and Treré (Citation2015) view digilante activism from the perspective of collective identity building, pointing to the viral uptake of memes on social media to ‘join’ various social movements, including protests and demonstrations. Examples include Anonymous’ anti-establishment Guy Fawkes masks, which had a popular presence on Facebook from 2003, and the hashtag #wearethe99percent launched by the Occupy Wall Street movement on Twitter. In this sense, social media can be approached as a space for the negotiation and performance of identities, communicated via emerging iconographies and lexicons. Yet most of the literature in the fields of communication and tourism studies have focused on the organisational and strategic consequences of social media protests, at the expense of examining collective identity and forms of expressive communication. These form the basis of our netnographic analysis, introduced below.

Methods

Philosophically, our analysis takes orientation from Scheurich’s (Citation1997) metaphoric grid of social regularities, inside which ‘problematic’ groups (in this case, those that are recognised as having subverted or disrespected Holocaust memorial spaces) are constructed and discussed. This grid is both epistemological and ontological, since it constitutes simultaneously who the ‘problem’ group is, as well as how and by whom it is seen/recognised as problematic. Our aim in describing such a grid of social regularities was to understand how particular individuals come to be recognised as ‘a problem’. Following Scheurich’s ideas around epistemological actions, we investigate the discursive practice (i.e. how knowledge is produced through culturally contingent practices) of digilantism as enunciations (Foucault, Citation1972), which determine who and what is problematic in such settings. Our unique focus is therefore on the treatment of social media posts through comment-reactions, rather than analysing the posts themselves. As such, we produce an analysis of digilantism-as-discourse by recognising enunciations that function with constitutive effects (Foucault, Citation1972).

Netnography in tourism research

Netnography is increasingly used methodologically in tourism research to understand the complexity of social experiences, and to offer alternatives to big data methods, which obscure the potential for humanistic interpretations of tourism (Kozinets, Citation2022). Podoshen et al. (Citation2011) note how netnography is useful as a means to obtain data in virtual settings, since the social groups within these environments are ‘real’ to the participants, and therefore constitute tangible examples of consumer behaviour. Netnography, they suggest can be used as a naturalistic, unobtrusive method to engage with online communities through passive observation to understand community members, and the discourses that occur between them (Citation2011). Iqani and Schroeder (Citation2015) speak to the importance and value of selfies as units of analysis in netnography, noting that they have implications for identity, privacy, security and surveillance, but also for authenticity, consumption and self-expression. As a consequence, a number of contributions in the tourism literature address the centring of the self through images, using netnography as a method of inquiry. Examples include Canavan’s (Citation2020) analysis of the social media activity of backpackers taking part in the 2019 Mogol intercontinental car rally. Using this approach, Canavan identified nuanced motives linked to the performance of ‘seeing, and being seen’. Similarly, the technologically mediated tourist gaze is central to Dinhopl and Gretzl’s (Citation2015) analysis of selfie-taking as a means of ‘tourist-looking’, in which tourists become the objects of a self-directed gaze as part of an emerging visual culture of the self-as-tourist. This culture is specifically interpreted as a departure from the analogue gaze – whereby the extraordinary sights of destinations are fetishised – towards an emerging set of consumption rituals that capture the extraordinary-of-the-self, with the sights and attractions assuming diminished importance. This is observable in dark tourist settings such, as Grutas Park, Lithuania, in which statues lure visitors into creating interactive selfie poses for their own amusement (Wight, Citation2009).

The present study

The articles cited above – and many others in a similar vein – focus on the selfie as an object of analysis. However, there remains a gap in the tourism literature around the intertextuality of selfies – how they intersect with captions and with viewer comments – and the ways in which this complex interplay mediates identity negotiations at individual and group levels. We propose that self-centring images, user-generated captions, and viewer/reader responses, taken together, offer a rich data set in which the negotiation of identities is observable. Our goal is therefore to examine the critical digilante treatments that some Holocaust-selfie posts are subjected to, in order to extend knowledge around public reactions to seemingly disrespectful selfie-taking/posting behaviours at Holocaust memorials and tourism attractions.

As a social media site, Instagram is different from Facebook, for example, in that most accounts are open access, and networks do not mainly rely on, or replicate real-world friendships. Many accounts are anonymous, with users hiding their legal names behind pseudonyms. This means that Instagram users can ‘follow’ and ‘be followed’ by each other based on common interests, discoverable through hashtags (keywords) and geotags (location labelling). In a paper on the ethics of using social media data, Stevens et al (Citation2015, p. 157) conclude that considerations for using online social media data are: the distinction between public and private spaces, informed consent, and protecting data to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. For this reason, the data in this paper were exclusively drawn from public-domain Instagram accounts. Further, the posts that are offered as examples have been anonymised by blurring/covering user-names, anonymising photographs, and checking the searchability of utterances to ensure anonymity.

For this paper, we analysed 4000 Instagram posts, considering 1000 from each of two hashtags (#auschwitz and #holocaust) and 1000 each from two geotags (the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, Germany and Auschwitz-Birkenhau in Oświęcim, Poland). Under each of these tags sit many thousands of individual posts: for instance, as of September 2021, #auschwitz has 493,000 public posts and #holocaust has 835,000. These posts are accessible via the hashtags/geotags mentioned above, and in each case, viewers are offered two ways of viewing a selection of posts relating to topics or places. One can view ‘top’ posts, which are ranked numerically by the number of ‘likes’ they have received. Alternatively, one can select ‘recent’ posts, in which additions are listed in reverse chronological order.

Within this large data set, we examined both ‘top’ and ‘recent’ index pages, analysing five hundred posts in each index for each tag (i.e. 500 posts in each of two indices – ‘top’ and ‘recent’ – for each of four tags; so, 4000 posts in total). In order to capture seasonal variation among visitors posting under the various tags, and appearing in the ‘recent’ indices, data analysis was undertaken across three phases: March/April 2021, August/September 2021, and November 2021. Having identified overall genres and types of post, we focused on those that displayed self-centring portraits – including selfies – with at least one critical comment. Within these, we identified just over 200 within the overall set. To reiterate: our intention was not to catalogue all posts or activity in these spaces – a Sisyphean task – but to consider examples of self-centring photographic behaviours, captioning, posting, and digilante-type comments.

Data reduction was achieved using Nichol’s (Citation2009) approach to critical discourse analysis, based on a strategy of accumulating familiarity with source-data. We also took orientation from Namey et al.’s (Citation2008) approach to content analysis, whereby entries were read closely, with themes, trends, and ideas emerging iteratively to shape analysis. Having identified our core themes in this way – the negotiation work of selfie-taking and online commenting and the factors that appear to mediate the tone of online commenting – we then undertook constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, Citation2014). This meant that we centred the data itself, inductively drawing out the data and discussion, organised into sections, as presented below. In this way our understandings (and thus, our theorising) come from the data itself rather than from any overlaid theoretical framing applied from the outset.

Data analysis was then undertaken using critical discourse analysis and Pearce and Wang’s (Citation2019) framework of tourists’ photographic pose types. It is important to note that these are qualitative methods, and no attempt was made to produce a quantitative account of the number of instances of a given phenomenon. As qualitative research, this data and its analysis is not intended to represent from ‘sample’ to ‘population’. Instagram, like all social media, is in constant flux, with new posts and comments being added and deleted second-by-second. While it would, in theory, be possible to hold still a ‘snapshot’ of Instagram on a given day and time, and count the numbers of posts, comments, this is not what we sought to achieve.

Findings

Genres of Holocaust-related social media posts: images and captions

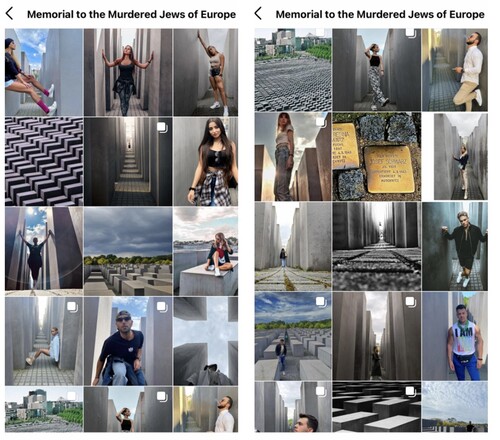

In three of the four tags considered in this paper, the top posts are not tourist selfies. Instead, under the hashtags #auschwitz and #holocaust, and in posts geotagged at the Auschwitz memorial site, the most ‘liked’ images are overwhelmingly historical photographs, primarily pre-war images of individual Jewish people living their pre-camp lives. The same cannot be said for many of the posts geotagged at the Berlin memorial, where user-centring posts are very common, as screenshots from the index page show (). As a result, digilante comments are overwhelmingly concentrated under this geotag, and in this section, we present and discuss examples of selfie-based posts and the digilante comments they attract. We are particularly interested in the ways in which some selfies seem to trigger digilantes where others do not. We then explore possible reasons for geographical differences between the Berlin site compared to the other geotag/hashtags.

To provide a brief orientation to the site itself, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe occupies a city square near the Brandenburg Gate. It comprises 2710 grey concrete slabs (called ‘stele’) arranged in a grid pattern, each 2.38 m by 95 cm in length/depth, and of varying heights, ranging from 20 cm to 4.7 m. Inaugurated in 2005, it is designed to evoke in visitors feelings of ‘unease and confusion’. There is space to walk between the stele, but it is difficult to get a sense of the overall layout/pattern (Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Citationn.d.). Importantly, there is no signage: no victims are named and no overt mention is made of Holocaust. Further, while there is an underground visitor centre, open during the day, the memorial itself is open all hours and in all weathers, as part of the central-Berlin cityscape.

The memorial site’s Instagram geotag offers rich pickings for ‘rule-breaking’ selfies and digilante-shaming, and we begin by discussing two examples of this phenomenon ( and ). The first is a post from a young Austrian woman who poses at the Berlin site in a summer dress. She is conventionally attractive, sitting on the ground with her back to one of the stele, her feet up, and her right shoulder and gaze turned towards the camera. Per Pearce and Wang’s (Citation2019, p. 117) framework, her pose is ‘projecting’: she ‘dominat[es] the image through physical movement … fill[ing] the frame of the photograph and represent[ing] an exhibitionist, look-at-me style’. Indeed, the Berlin memorial itself hardly features: the uneven stele tops are cropped out of the picture, leaving an anonymous grey backdrop that serves to highlight the woman herself. There is no caption, only three hashtags: #berlin, #germany and #memorial, and the photo receives 374 likes and 12 comments, mostly positive (including ‘gorgeous’ and ‘so hübschhhh [heart emoji]’ [i.e. ‘so prettyyyy’, in German]). However, two critical comments appear, including one in which she is shamed for using the memorial as a ‘backdrop for [her own] self-actualization’. One reads ‘No respect and only one [previous commenter] calls it out … You are disgusting’. The first comment garnered 28 likes, and the second, added nine weeks later, attracted three likes. Both digilante comments are in English.

The second example (see ) is a Spanish tourist who posts a selfie that blends Pearce and Wang’s ‘model’ and ‘composed’ categories. The caption, in English, reads: ‘Right or wrong, I had to do it’. No further explanation is given, but the meaning is negotiated in the 25 comments that follow. The first comment-type are messages of praise/approval. There are flame and heart emojis [suggesting he looks ‘hot’, i.e. attractive], and the comments ‘eres tan bonito’ [‘you are so pretty’] and ‘me flipas, amigo’ [‘you freak me out, friend’]. The next comment type is messages where the meaning of the caption is negotiated. These include: ‘Peeeeerooooo que pasa contigoooo???’ [buuuuut what happened with yoooou?], ‘A ver está wrong, pero como te queda todo bien te perdono’ [Let’s see what is wrong, but as everything looks good, I forgive you], and ‘U had 2do what???’. It appears from these comments that while the original poster knows that Holocaust memorial selfies are contentious and potentially transgressive, some of those commenting do not. In response to the second comment, the original poster replies, although the reply does not serve to clarify much. He writes: ‘I know! Era consciente de que no era correcto, pero pudo más mi incocorreción. Nadie es perfecto [I was aware that it/I wasn’t correct, but my wrongness was stronger] [eyeroll emoji; shrug emoji]’. Finally, there is a third type of comment on the post, with one commenter writing, simply, ‘#yolocaust’, while another initiates the following exchange:

Commenter [who posts elsewhere in German and English]: This place is called “memorial to the murdered Jews of [E]urope” and still ppl [people] act like it’s a runway #yolocaust

Original poster, replying: I know, that's why the title [i.e. caption] of the photo.

Commenter: Ok now I am curious, is this the next level of irony that I don’t get at this point? Joking about ppl misusing the memorial for self-presentation and likes by misusing it for self-presentation and likes?

Factors affecting digilante engagement

Whilst we do not intend to present a quantitative analysis of the data corpus or the broader ‘population’ from which it is drawn, there are some broad tendencies worth noting within the data. First, location matters. There is far more censure of ‘inappropriate’ posting at Auschwitz than there is at the Berlin Memorial, for reasons suggested below. Second, users’ phenotypical characteristics seem to affect the reception of their posts, with salient factors including age, gender, and – in the case of younger women – conventional attractiveness and choice of pose. While physical attractiveness is difficult to quantify, research shows high inter-rater reliability in studies based on subjective judgements (e.g. Gupta, Etcoff & Jaeger, Citation2016). Physical attractiveness is also gendered, with attractiveness markers for women including a small waist combined with relatively large hips (Lassek & Gaulin, Citation2019), whereas for men a similar role is played by muscularity (Cordes, Vocks & Hartmann, Citation2021). These factors are multiplicative, affecting the content and prevalence of comments. The result is that younger women – and particularly attractive younger women choosing ‘model’ or ‘projecting’ poses that display the body – seem to attract the most digilantism, all other factors being equal. Third, and overlapping with the above tendencies, the language of the post seems to matter, as this likely affects the demographics of those viewing and commenting, including the users’ own circle of followers, but also others finding the post through language-specific hashtagging. Specifically, posts written and hashtagged in Russian or Turkish, for example, seem to attract much less digilantism than posts in English or German.

Interestingly, younger people, particularly attractive younger women bear the brunt of digilantism. We posit that this tendency may relate to the perceived sexualisation of young women’s bodies more broadly, and more specifically the poses and/or attire of some women who choose to display their bodies in model-like ways. Perhaps these behaviours are perceived by digilantes as jarring most strongly with the ‘respectfulness’ necessitated by the setting. Age differences may also be connected with more proficient hashtagging among younger people and/or numbers of followers, and thus the relatively easier findability of some users’ posts.

Location is also important. While the Berlin Memorial sees plenty of ‘disrespectful’ tourist behaviour, it is rare to encounter disrespectful selfie-taking at Auschwitz itself. We propose the following theorising to understand why this is the case. First, at Auschwitz, most visitors pay to enter, and to be escorted by guides; there is only a short period in the day when it is possible to enter without a guide, and thus without paying. Related, the Auschwitz-Birkenhau Museum is not easily on any tourist trail: it takes some time to reach by public transport from Kraków, and tours cost around forty Euros per person. Thus, getting to Auschwitz is something of a production. Presumably, therefore, those visiting Auschwitz have a good sense of where they are, why it is significant, and why they have made an active decision to engage with the site. In contrast, the Berlin Memorial exists as part of the central Berlin cityscape – indeed, some Instagram posts use generic hashtags such as #urbanlife, #flaneur, and #streetphotography as well as the Berlin memorial geotag – and it is plausible that some visitors to the Berlin site do not realise what its purpose actually is, not least as the visitor centre is tucked away underground and there is no signage on the stele themselves.

Second, Auschwitz is deeply confronting in the artefacts it displays: pictures of piles of bodies and portraits of individual victims, for example, with the sheer scale of murder emphasised with piles of everyday objects that belonged to victims. The Berlin memorial, in contrast, is comprised of concrete blocks. Indeed, the Berlin memorial is designed to be interactive and experiential. So, again, it may be easier to miss its significance, and to focus, instead, on simply interacting with a quirky memorial. For these reasons, being ‘disrespectful’ seems to be easier at the Berlin memorial: it is part of the cityscape, it is open all hours, and it is a conduit to other places, with minimal signage. A related reason is that the memorial may simply be more interactively photogenic and ‘Instagrammable’; perhaps it just looks better on screen.

In the case of unmanaged monuments, such as the Holocaust monument in Berlin, however, it is not clear whether those photographed are aware of the significance of the sites that form the backdrop to the images. Indeed, the highly subjective nature of tourism experiences means that observations made about visitors to dark tourism sites cannot prima facie tell us much about visitors’ motives. Places that exist which mark tragic histories may not, after all, be intuitively recognised as significant, or ‘dark’ by those that visit them, particularly in the absence of explicit signage. Conceivably, therefore, a form of ‘free range’ dark tourism is taking place. Crucial here are notions of the ‘unwitting’ or ‘unintentionality’ that have surfaced in debates around dark tourism motivation, and it may be that innocent responses to ‘dark’ spaces are not just common, but natural, and even intuitive for certain age groups.

Cultural capital, identity display, and bending the rules

Besides location choice, another way that Holocaust memorial site visitors can avoid digilante censure is through complex captioning, including overt identity display. This section discusses how text – in captions but also comment responses – mediates seemingly problematic images. By strategically leveraging specific types of symbolic, cultural, and social capital in the text, Instagram users seem to earn the right to break the rules. Two examples are offered here.

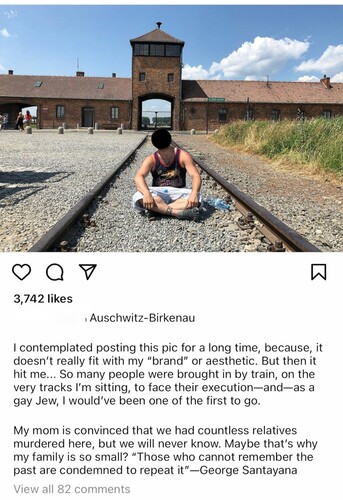

is the first of these. The picture shows a US American man in his late thirties as he sits, cross-legged, on the disused train tracks leading to the red-brick Auschwitz tower gate. It is summertime, and he wears long shorts, a vest top, and sunglasses. His expression is neutral, and his body is held ‘composed’, ‘signaling a low-threat individual’ (Pearce and Wang, Citation2019, p. 117). This Instagram account differs from the majority in the data set in that it has a relatively large follower count: 68,300 as of November 2021 (although likely fewer in summer 2018, when this post is dated). For this reason, follower engagement involves much higher numbers than other posts: 3742 likes and 82 comments.

Larger Instagram accounts may creep into the territory of social media ‘influencing’, defined as everyday people whose textual-visual narration of their lives becomes increasingly professionalised, so as to maximise and commodify their audiences, leading to paid content (e.g. Van Driel & Dumitrica, Citation2021). This does not seem to apply to this account, although the user appears in most of his posts, usually in user-centring selfies, generally alone, and mostly in dynamic or projecting poses (Pearce & Wang, Citation2019). In this sense, his Auschwitz picture is little different from the rest of his feed. However, an implied association with the ethics of ‘influencing’ and the importance of maintaining a certain look or feel to the account may explain the opening sentence of the caption (also shown in ).

This is an instructive exemplar of a caption that serves to permit the photo. Its moves can be analysed as follows:

I contemplated posting this pic – not taking lightly the fact of posting an Auschwitz selfie;

… as a gay Jew – claiming insider status in the persecuted group, suggesting a legitimatising disadvantage from which to speak;

My mom is convinced that we had countless relatives murdered here – aligning with persecuted group; emphasising nature and extent of persecution;

’Those who cannot remember the past’ – invoking philosophical aphorism, which performs the following functions: 1. by adding a legitimising veneer of historicity, credibility is added and thus the perception of a considered and well-argued post; 2. it firmly positions the writer as anti-Holocaust; and 3. it represents a performance of erudite identity, i.e. perhaps someone more difficult to dismiss with a facile digilante-style #yolocaust in the comments.

And, indeed, no digilante comments are made. Instead, the comments include the following:

Well said

Damn dude that’s brutal

Nothing wrong with this post … much respect!!!

These comments engage with the content of the post, and all are supportive of the fact of visiting and posting a selfie.

Other comments, however, are more complex, containing gentle digilantism worded in much more reasoned and subtle ways than in the comments analysed above. They include:

Unfortunately, you are correct. Personally, I do not approve of these macabre pilgrimage[s]. Poland is the biggest cemetery of the Jewish people. A country whose population at large were deeply anticlimactic [sic; anti-Semitic?] and collaborated with the nazis should not profit by this kind of tourism. Come to Israel and visit יד ושם [Yad Vashem; Israel’s official Holocaust Memorial site].

o [user] I’m planning a visit there … maybe even this summer

This perspective focuses critique on Poland/Polish people’s putative complicity in the Nazi Holocaust, seemingly disagreeing with the account holder even visiting Poland. Other similarly subtle comments focus on the account holder’s concern with brand integrity, his lack of research into or knowledge of his family’s Holocaust history, and the fact of non-Jewish/non-gay victims of the Holocaust. Examples of these comment types read as follows:

[commenter X] Glad you had the courage to get past your ‘brand’ and be real. It matters.

o I agree with [commenter X] … as the granddaughter of survivors from the Armenian Genocide … the brand you have today won’t matter if history repeats! So we never ever forget. May the countless souls who perished Rest In Peace [butterfly emoji]

o [user] yes, we must never forget! Otherwise, we are condemning our future!

Thank you for that picture. These monsters actually kept really detailed records of names and people. So, with a bit of digging you might be able to find out what happened to your family.

o [user] maybe one day I’ll try.

o [commenter] let me know if you need help

Thank you! Mine relatives too. But not that they were Jews they were also Gypsies and anyone who looked Jewish. Curly dark hair would make one a target. In my case I also give my respects for all the gay men who went down there.

o [user] I have curly dark hair! I’d be one of the first to go …

Together, these comments critique the user’s engagement with Holocaust as rather superficial. Although he performs complex legitimising identity work around the posting of his Auschwitz selfie, he is nevertheless subject to digilantism around the level of engagement. This can be seen especially in his replies to these comments, which seem (with their exclamation marks) rather glib.

However, what we are seeing in the case above is not the considered comments of a Holocaust scholar. These are brief, social-media engagements with strangers by someone who runs a popular Instagram account, writing while he is travelling in Europe, and engaging on a topic that is not the main focus or interest of his account. The critical comments he receives seem to imply that only those ‘qualified’ to take on the Holocaust may post about it. We would disagree, as discussed below.

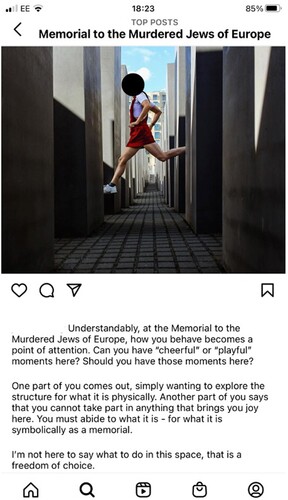

But identity work that allows for rule-bending does not always rely on insiderness (e.g. invoking Jewish and/or gay identities). Although seems to be a classic ‘disrespectful’ selfie, taken of the account holder jumping between the Berlin memorial stele, a competent caption performance seems to mediate the image. This juxtaposition complexifies the post by questioning visitors’ right to enjoy the space cheerfully or playfully –‘for what it is physically’ [that is, an artist-made installation]. She concludes by noting that it is not for her ‘to say what to do in this space, that is a freedom of choice’. However, the intertexuality between photograph and caption negate this statement: clearly, she takes up the position that being ‘playful’ in the space is acceptable.

In a subsequent post – which features a similarly ‘playful’ selfie taken in the same site – she adds:

Many people play amongst these blocks, that urge to play in such a different space comes naturally. To quell it or decide against it will come second. But only if you know why you should be thinking twice. This memorial, as any memorial, stands to remind us of something. In this case, to remind us of the Murdered Jews of Europe. … A photo of several grey blocks was stuck up in my RS [religious studies?] class, I didn’t know what it symbolised, and in that class I never asked. So, it’s easy to forgive anyone for running around and hiding between blocks, admiring the shadows, when there is little to explicitly confront what it stands for, just the simple fact that you must know, and an underground information centre hidden away.

Discussion and conclusions

Coming to terms with Holocaust selfies: psychogeographic exploration

It appears, therefore, that seemingly disrespectful Holocaust selfies routinely escape censure, but only if these are accompanied by captions displaying adequate cultural capital. The attempts in and failed to do this, by not posting a caption at all () or posting too cryptic a caption (). These – and many other like them – received digilante comments as a result. However, the examples in (claiming membership of insider groups) and (performing a seemingly erudite identity) seem to allow for disrespectful selfies to go unchallenged. This finding is a tendency that extended well beyond the selected examples, across the data set.

The digilantes seem to be ‘punching down’. They display their own putative cultural capital of ‘knowing better’, thereby performing identities (self-)positioned as morally superior to those they critique. This seems galling – bullying, even – when we note that their targets tend to be women, younger people, and those posting in languages other than English and/or writing in English as an additional language. Whereas the digilantes cited are predominantly USA- and UK-based, the targets of their shaming comments in the data set were variously Austrian, Mexican, Spanish, Danish, and Thai. Besides the linguistic advantage, US- and UK-based Instagrammers may be more closely associated with ‘cancel culture’, ‘wokeness’, and other recent forms of digilante activity, which originate in and arguably still largely ‘belong’ to the Anglosphere.

Paradoxically, also, it appears that the digilantes are, themselves, engaged in precisely what they are critiquing: centring the self in an identity performance that enhances their own status. Whereas those posting model-like selfies do this in ways that display their own (attractive, desirable) bodies, the digilantes do precisely the same thing in ways that display their own (attractive, desirable) moral superiority and/or erudite minds. This is to say: the digilantes themselves perform desired identities using Holocaust as a foil against which to centre the self. What is different is that they seem to enjoy a greater position of cultural capital from which to look down on those who do not. Certainly, as Trottier writes (Citation2020, p. 206; our emphasis):

[P]articipants may come to discover offensive conduct, either by witnessing and presumably recording and uploading an embodied offence, or by proactively searching for objectionable content in a target’s online presence. They may spread this content through mobile devices onto social platforms, and may add editorial content that serves to reproduce mediated policing. … Yet this implies a certain amount of capital and privilege on the part of those advocating for [i.e. denouncing] something deemed offensive […] Participants impose denunciatory values and opinions upon a target, who is identified and scrutinised through their personal information, but also through their reputation. Here scholars should be attentive to how the social status of a target is expressed in public discourse, as well as the grounds upon which they are being shamed (the offence in question; behaviour more generally; perceptions of their character; categorical affiliation). Shaming may [be] considered as either reintegrative or stigmatising [.]

Further, the skewing of digilantism towards conventionally attractive younger women – especially those posing in model-like and projecting ways – seems particularly problematic, suggesting as it does that such identities are inadequately ‘serious’ to be posting about the Holocaust. In this, the digilantes’ behaviour tends to echo feminist critiques that women – particularly whose gendered identity performances are conventionally feminine – tend to be taken less seriously, being assumed to be less competent and even less than fully human. As discussed above, when the ‘correct’ performances of deference and respect at Holocaust tourist attractions ‘fail to conform to those norms of cultural intelligibility, they appear only as developmental failures or logical impossibilities from within that domain’. That is: when younger women visit Holocaust memorial sites and engage with them in their own ways, they are bullied for doing so.

We remain unconvinced by the putative certainty and harshness of the digilantes’ comments. Plenty of posts from the Berlin site are of people climbing or jumping between the stele; posing for ‘arty’ photos; or simply having fun with their friends. Many are of children or young people. Indeed, perhaps this is part of the point of Holocaust memorials: visitors are living their ordinary, complex, joyous lives, exactly as six million Nazi murder victims could not. Might it be that the touristic purpose of memorial visiting is precisely about enjoying them in one’s own way? Might some visitors later reflect on those whose lives were cut short and who did not have the same opportunity to simply horse around, having fun? While such behaviour may appear to be ‘disrespectful’, we feel it is more important to keep alive – however clumsily and imperfectly– the memory of more than six million murdered people (who were predominantly Jews, but who were also LGBTQIA + people, Roma people, people with disabilities, and people who helped those fleeing the Nazis). To censure those engaging with the sites and posting in their own ways about the Holocaust would risk censoring discussion.

This is not to say that any and all engagement with Holocaust memorial sites is better than no engagement. Clearly there are, and there should be, limits. For this reason, the German penal code (Strafgesetzbuch, Citation1998) proscribes Holocaust denial and Nazi propaganda, including symbols. In 2017, the Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz (Network Enforcement Act) extended this proscription to social media content, providing for fines of up to fifty-million Euros for social media companies that do not delete illegal posts – including posts related to Holocaust denial and Nazi propaganda – within 24 h.Footnote1 In contrast, playful and perhaps ignorant engagements appear, to us, to fall rather more on the side of clumsy imperfection than dangerous denial. Commane & Potton write (Citation2019, p.178):

The inconsistencies and varieties of representations uploaded to Instagram using #Auschwitz sustain and continuously generate discussions about sites of trauma; thus social media can provide a significant role in maintaining Holocaust remembrance in future generations’ lives.

Theoretical and management contributions

In our analysis of a corpus of intertextually complex Instagram images and comments, we identify a social grid of regularities in which disorderly objects (selfie takers in Holocaust settings) come to be socially constituted via acts of digilantism in the rarefied setting of social media. Second, we note that these constructions are mediated through intertextuality, with complex captions and comment-responses serving to mitigate the effects of seemingly disrespectful selfie-taking and posting. In terms of critical discourse analysis, our analysis represents an example of Foucault’s concept of discursive formation, which is to say that Holocaust self-images on Instagram draw from a means of thinking that perpetuates itself: it enacts a systematic paradigm or (co-constructed) reality of Holocaust commemoration that only exists so long as the posts continue to be generated. Discursive formations are the capillary actions of discourse: the means for the dispersal of ‘realities’ that exist only when they are enacted. These realities are therefore enacting structures that shape and maintain ‘the way things are’ in terms of Holocaust tourism in the digital/image-saturated age. These observations add to the debate on the extent to which Holocaust and dark tourism memorial attractions, and visitors to these ought to be organised and controlled according to fixed or fluid values.

Our theoretical and management contributions can therefore be located within the body of literature on dark tourism, and particularly in the context of more recent outputs that speak to moral transgression and image sharing on social media. First, the fixed expectations (Wight, Citation2020) that visitors have of Holocaust heritage sites, and the collective anxieties that are apparent as a reaction to the behaviours of others as they go about consuming Holocaust heritage are confirmed in this study. This code of ethics is articulated on Instagram in the form of digilantism, which is recognisable as a social movement (Gerbauda and Treré, Citation2015) which organises itself in opposition to Holocaust tourism as a performed identity. We also extend the conceptual analysis offered by Bareither, (Citation2021) in noting the complex identity work that is provoked in response to Holocaust heritage selfies which are posted as a way of exploring and enacting emotional relationships to the past. We suggest that, far from being simplistic (Citation2021) and sweeping, the narratives of condemnation, at least on Instagram are nuanced, and tend to emanate from the Anglosphere, targeting mainly young women and non-native English speakers, enunciating cultural capital to assert status. Despite the volume and variety of digilantism that this paper identifies, selfies remain a present-day form of legitimate social currency, (Iqani and Schoeder, Citation2015) and Holocaust heritage selfies are no exception as evidenced by the sheer volume that we came across in our analysis. Finally, our analysis challenges Pratt and Tolkach’s (Citation2022) framing as selfie-taking amongst tourists as egocentric and occasionally ‘stupid’. The idea of the quest for the best or most quirky selfie to provide egocentric tourists with bragging rights on social media is contested in our analysis, which suggests that, in many cases there is a playful innocence to selfie-taking at Holocaust heritage spaces, particularly those that have sparse, or absent visitor interpretation.

In terms of managerial implications, this paper invites managers at Holocaust memorial and other sites of atrocity, as well as visitors to look beyond the binary positions of ‘acceptable / not acceptable’ in relation to selfie-taking at Holocaust heritage sites, and to consider the possibility that engagement is nuanced. Despite the accumulation of digilante discourses on social media, there is no ‘correct’ way to consume Holocaust heritage. Indeed, the practice of consumption, far from being one-dimensional is complex, and shaped by the cultural and demographic backgrounds of visitors. Further, the extent to which there is a self-awareness when it comes to the consumption of Holocaust spaces is clearly tempered by the extent to which these are commercialised, visitor-orientated and presented using interpretive techniques and basic signage. At sites where respectful consumption is deemed important, there is a need to communicate this to visitors, but also a need to recognise behaviours cannot be enforced, particularly as part of a culture that continues to embrace self-images, and the practice of sharing on social media.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Craig Wight

Craig Wight has authored works within a range of journals and books on the discourses of genocide heritage sites in the public cultures of various, mainly European destinations. Craig is a recognised expert in the field of genocide heritage as part of the wider research topic of dark tourism. He has disseminated his research at international conferences, and was recently interviewed by the New York Times about trends and emerging products in dark tourism.

Phiona Stanley

Phiona Stanley's research centres on mobilities and how people engage in 'intercultural' settings. This includes research on working abroad, intercultural education, and tourism in terms of the outdoors, sport and mobilities. Her theoretical paradigm is critical and she is particularly focused on how power relations operate in these spaces. She is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) and is interested in innovative ways of doing, writing, and teaching qualitative research methods.

Notes

1 We focus here on German legislation because, as noted above, most of the questionable selfie-posting and resultant digilantism occurs at the Berlin Memorial rather than at the Auschwitz Museum, which is in Poland.

References

- Antchak, V. (2018). City rhythm and events. Annals of Tourism Research, 68, 52–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.11.006

- Bareither, C. (2021). Difficult heritage and digital media: ‘Selfie culture’ and emotional practices at the memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1768578

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

- Canavan, B. (2020). Let's get this show on the road! Introducing the tourist celebrity gaze. Annals of Tourism Research, 82, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102898

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructivist grounded theory (2nd ed). Sage Publications.

- Commane, G., & Potton, R. (2019). Instagram and Auschwitz: A critical assessment of the impact social media has on Holocaust representation. Holocaust Studies, (25/1-2), 158–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2018.1472879

- Cordes, M., Vocks, S., & Hartmann, A. S. (2021). Appearance-related partner preferences and body image in a German sample of homosexual and heterosexual women and men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 3575–3586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02087-5

- Coverley, M. (2018). Psychogeography. Oldcastle Books Ltd.

- Dinhopl, A., & Gretzel, U. (2015). Selfie-taking as touristic looking. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.12.015

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge. Pantheon Books.

- Gannon, V., & Prothero, A. (2016). Beauty blogger selfies as authenticating practices. European Journal of Marketing, 50(9/10), 1858–1878. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-07-2015-0510

- Gerbaudo, P., & Treré, E. (2015). In search of the ‘we’ of social media activism: Introduction to the special issue on social media and protest identities, information. Communication & Society, 18(8), 865–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1043319

- Gupta, D. N., Etcoff, N. L., & Jaeger, M. M. (2016). Beauty in mind: The effects of physical attractiveness on psychological well-being and distress. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(3), 1313–1325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015

- Hess, A. (2015). The selfie assemblage. International Journal of Communication, 9(1), 1629–1646.

- Iqania, M., & Schroeder, J. E. (2015). #Selfie: Digital self-portraits as commodity form and consumption practice. Consumption Markets and Culture, 19(5), 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2015.1116784

- Jane, E. A. (2017). Feminist digilante responses to a slut-shaming on Facebook. Social Media and Society, 3(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117705

- Kozinets, R. V. (2015). Netnography: Redefined (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Kozinets, R. V. (2022). E-Tourism research, cultural understanding, and netnography. In Z. Xiang, M. Fuchs, U. Gretzel, & W. Hopek (Eds.), Handbook of e-tourism (pp. 737–752). Springer.

- Kozinets, R. V., Gretzel, U., & Dinhopl, A. (2015). Self in art/self: Museum selfies as identity work. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(731), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00731

- Lassek, W. D., & Gaulin, S. J. C. (2019). Evidence supporting nubility and reproductive value as the key to human female physical attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behavior, 40(5), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2019.05.001

- Lindgren, M., & Wahlin, N. (2001). Identity construction among boundary-crossing individuals. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 17(3), 357–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(99)00041-X

- Manning, E. (2013). Always more than one: Individuation’s dance. Duke University Press.

- Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe . (n.d.). Retrieved From https://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/en/memorials/memorial-to-the-murdered-jews-of-europe/.

- Minaar, A. (2001). The new vigilantism in post April 1994 South Africa: Crime prevention or an expression of lawlessness? Institute for Human Rights and Criminal Justice Studies, Technikon, South Africa.

- Moss, C. (2014). This teenager is getting harassed after her smiling selfie at Auschwitz goes viral. Business Insider (July, 20) Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/selfie-at-auschwitz-goes-viral-2014-7?r = US&IR = T.

- Murray, D. C. (2015). Notes to self: The visual culture of selfies in the age of social media. Consumption Markets & Culture, 18(6), 490–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2015.1052967

- Namey, E., Guest, G., Thairu, L., & Johnson, L. (2008). Data reduction techniques for large qualitative data sets. In G. Guest & K. M. MacQueen (Eds.), Handbook for team-based qualitative research (pp. 137–163). AltaMira.

- Nicholls, D. A. (2009). Putting Foucault to work: An approach to the practical application of Foucault's Methodological Imperatives. Aporia, 1(1), 30–40.

- Pearce, P. L., & Wang, Z. (2019). Human ethology and tourists’ photographic poses. Annals of Tourism Research, 74, 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.11.002

- Podoshen, J. S., & and Hunt, J. M. (2011). Equity restoration, the Holocaust and tourism of sacred sites. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1332–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.007

- Pratt, S., & Tolkach, D. (2022). Stupidity in tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 47(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1828555

- Reichl, F. (2019). From vigilantism to digilantism? In B. Akhhar, P. Bayerl, & G. Leventakis (Eds.), Social media strategy in policing. Security informatics and Law enforcement (pp. 117–138). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22002-07

- Scheurich, J. J. (1997). Research method in the postmodern. Routledge.

- Shapira, S. (2017). Yolocaust. Retrieved from: https://yolocaust.de/.

- Stevens, G., O'Donnell, V. L., & Williams, L. (2015). Public domain or private data? Developing an ethical approach to social media research in an interdisciplinary project. Educational Research and Evaluation, 21(2), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2015.1024010

- Strafgesetzbuch. (1998). German Penal Code (trans. Bohlander). Federal Ministry of Justice (Germany). Retrieved 21 November 2022, from: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_stgb/englisch_stgb.html.

- Tiidenberg, K., & Cruz, E. G. (2015). Selfies, image, and the remaking of the body. Body & Society, 21(4), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X15592465

- Trottier, D. (2020). Denunciation and doxing: Towards a conceptual model of digital vigilantism. Global Crime, 21(3-4), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2019.1591952

- Van Driel, L., & Dumitrica, D. (2021). Selling brands while staying “authentic”: The professionalization of Instagram influencers. Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies, 27(1), 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520902136

- Volo, S., & Irimiás, A. (2021). Instagram: Visual methods in tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103098

- Wight, A. C. (2009). Competing national narratives, An ethical dimension. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism (pp. 129–144). Channel View Publications.

- Wight, A. C. (2020). Visitor perceptions of European Holocaust heritage: A social media analysis. Tourism Management, 81, 104–142.