ABSTRACT

The present article focuses on three dominant forms of crisis in the twenty-first century (terrorism, climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic) that challenge tourism as a viable activity and sector. Through epistemological/methodological blends of compatible arguments from the sociology of knowledge (Karl Mannheim's notion of world-vision or Weltanschauung, which emphasises planetary ways of knowing), the new mobilities paradigm (Sheller's suggestion that such ‘knowing' also produces often competing positionalities and communities in research) and scholarship on the worldmaking powers of tourism (Hollinshead's and Hollinshead and Suleman's suggestion that knowing about tourism comes to life when it is enunciated as a reality), it investigates ‘affective refrains': recurring scholarly discourses about crises in the sector, which are endowed with affective qualities (Felix Guattari’s approach to preconscious formations of feelings). Such refrains, which are both prepersonal and structured like collective imaginaries, shed light on the core ethical and moral universes that are supported by their authors. Whereas the nature of the themes covered by these authors is the modus operandi of the scholarly community to which they claim membership. But more importantly, the styles they use to intensify the attention of audiences/readerships to these styles organises the powers of affective persuasion into a paradigm.

Introduction

Tourism analysis seems to progressively concentrate on the future of tourism as an activity and a multi-industry. The trigger seems to be distributed across at least three types of crisis, which threaten the tourist sector’s viability: terrorism, climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism and hospitality seem to be facing certain death, according to some scholars (Korstanje, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). However, before anyone agrees that tourism and hospitality are reaching ‘a dead end’, an investigation is necessary into why things are pronounced as such or otherwise and how scholars identify moral actants and agents in assemblages of human and natural ecologies. Crucially, even when tourism scholarship proposes solutions to such terminal problems, the moral texture on which such arguments are plotted seems to persist.

The article takes a closer look at the programmes of different scholarly communities with an interest in the futures of tourism. Fuller’s (Citation2011, Citation2012) suggest that in the twenty-first century human ‘interests’ are divided into biopolitical (with an emphasis on the political management of human life particularly), ecological (with an emphasis on the generation of rules about the management of dwelling territories, including the environmental) and cybernetic (with an emphasis on the digital-infrastructural organisation of social realities) as evident in the articles of this special issue. Nevertheless, interests communicate worldviews which eventually make (contribute to the design of) worlds of tourism (Hollinshead, Citation2009b). The emphasis on worldviews or Weltanschauungen (to use Karl Mannheim’s (Citation1936/1968) term) informs a deeper analysis of planetary-futuristic paradigms. In tourism analysis ‘paradigms’ are framed in a Kuhnian social-scientific discourse (Kuhn, Citation1962), which favours an understanding of their function as action frameworks (Jennings, Citation2012). From there, scholars are asked to demonstrate commitment to a methodological orientation, which in the field of tourism connects to three trends: interpretivism, positivism and critical analysis (Tribe, Citation2001). Drawing on Thomas Kuhn’s approach to scientific revolution, Jamal and Munar (Citation2016) see the role of paradigms as ways for a community to apposition itself in the field of practice (tourism studies), which have a durable influence in research and practice. However, a paradigm is the effect of peripheral (pará [παρά = nearby and around]) pointing/orientation (deikneíō [δϵικνϵίω]), a mobility device that delineates our field of movement as this is shaped by visions of the future. The field itself cannot be ‘proven’ factually in positivist ways, nor can it be reduced to subjective interpretations, because at the same time it exists independently from its enunciators (within communities of practice). A critical approach is also not enough when it reduces the field of interrogation to materialist manifestations of judgement calls that are made about the state of tourism. The latter is prominent in economic approaches to tourism claiming affiliation with critical traditions (Ibn-Mohammed et al., Citation2021; Okafor et al., Citation2022), which are problematised in this article. However, ‘critique’ in tourism analysis also possesses immaterial dimensions, which move past phenomenologies of perception and feeling. My approach is ‘postphenomenological’ because it attends to invisible processes of feeling, knowing, and valuing, which eventually shape the world around us materially. To reduce such processes to phenomenological or materialist inquiry is to miss the importance of temporality and contingency in the ways scholarly communities and their discourse come to life (see also Rosenberger & Verbeek, Citation2015). I return to this point below, as my version of postphenomenology does not inform science and technology but posthumanist approaches to crisis.

The article’s title dons an ‘economy of attention’ to suggest that what is chosen as the focal point in a paradigm constitutes a refrain, something that is repeated across different publications but also different domains of policy, scholarship, and even popular culture (although the latter is not addressed, because it belongs to a different type of futuristic design) (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1988, p. 315). Refrains allow for the gathering of forces of persuasion and thus the concentration of attention, so as to challenge an established argument (Bertelsen & Murphie, Citation2010, p. 145) – and continue until they assume its dominant position and may need to be challenged in turn. This means that refrains are pre-personal affective forces existing even within declared (and thus consciously articulated) futurist paradigms. Affects are phenomena emerging between sensorial and cognitive engagement with external environments. Although they are not consciously articulated emotions, they prompt humans to articulate action in the form of value-ridden utterances and even embodied performance. In this respect, they are existential happenings. Broadly speaking, ‘embodiment’ refers to the ways something is brought to life materially and conceptually; however, as a process (of what we may call ‘becoming’ a thing or a sentient being), it retains both formal (institutional, public) and informal (intimate, private) qualities. Because affects link the precognitive to the rational and conscious domain, they are involved in the early stages of making public culture. To bring to discourse such pre-personal constants in declarations of risks, crises, ends and beginnings in/of tourism and/or hospitality, the temporal ‘texture’ of the said ‘events’ (disasters and beginnings) must also be examined (Stern, Citation2004). Temporal textures or ‘contours’ allow for declarative paradigms to reorganise an existential territory (how we think and feel about bad events and hopeful possibilities), which is no longer viable.

Reorganising declarative paradigms by taking affective discourse seriously can shed alternative light on ‘vulnerability’ and ‘viability’ with regards to the academic field of tourism studies, but also its need to be enriched as an ontological and epistemological/methodological inquiry into planetary challenges and problems. Hollinshead and Suleman’s (Citation2018) suggestion that we do not dismiss the ‘declarative nature’ of tourism, and thus the ways it brings to life subjectively via everyday installations of practice, rather than institutionally, and organisationally places, cultures, and leisure activities, is repurposed. The present article’s ‘worldmaking’ tools, which are scholarly, may communicate with or be affected by the declarations/enunciations of the tourist state and international tourist industries in various ways. Enunciations/declarations refer to the realisation of ideas through their articulation in appropriate contexts, in which they can widely circulate and even be formalised. Hollinshead (Citation2009a) notes that the nation-state enters the field of tourismification to become an economic force (as a ‘tourist state’) by semantically defining the domains it governs as tourist sites. However, today’s tourism mobilities are managed by more blended networks of state-business partners, who subject the semantic potential of tourismified worlds (destinations) to the whims of demand. Massumi, (Citation2002, p. 24) calls such arbitrary negotiations of identity/meaning the ‘crossing [of] semantic wires’, because they produce new worldmakings (or Weltanschauungen), which are not always amenable to local needs and desires to autonomy from the calls of commercialisation. Sheller (Citation2020, pp. 105–106) notes that even academic researchers, who are often deemed to be in privileged positions vis-à-vis studied communities, are caught up in ‘bordering processes’ that hinge on competing territorialities. In many cases, scholarly worldmaking generates reflective and even oppositional worlds, which assume the role of a futuristic design modulated by affect and morality. Such cross-referential networks of enunciation will be mapped through intense repetitions in and across them. These refrains bring to life an academic existential territory, in which ‘ends’, ‘salvations’ and ‘future beginnings’ of tourism and its industrial networks emerge (Guattari, Citation1992/Citation1995, p. 28).

The second section outlines some key refrains currently at play in the field of tourism analysis. These refrains illuminate affective and moral textures in the teleological rationale of the three dominant crises in tourism activity and its industrial basis. Hence, the actual focal point is not the enunciation of vulnerabilities displayed by or within tourism, but the academic stances’ ‘categorical style’: the externalisation and sharing of particular affects and observations in the form of propositions about tourism futures. The article transposes an argument originating in psychotherapy (Stern, Citation2004, pp. 64–66) to the level of collective (paradigmatic) discourse with some serious qualifications and modifications: first, it acknowledges the porosity of borders between individual and collective experiences of crises as these unfold; second, it recognises that any futural propositions gain traction only when they draw on possibilities. The second section elaborates on the core values guiding such complex interplays between worldviews, tourism worldmaking and tourism imaginaries (first subsection), providing some concluding remarks (second subsection).

Dominant crisis trends and their refrains

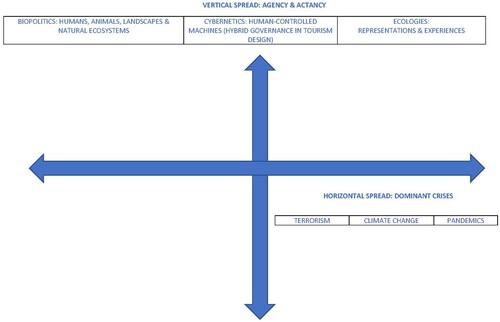

The number of paradigms circulating in tourism studies is vast, so a selection and appropriate organisation of ‘dominant trends’ is necessary (). The logic of selection is based on refraining: these paradigms present the most rigorous epistemological and methodological propositions in the field; aside their ‘reach’ or scope of judgment, scholars reiterate the necessity to commercialise, instead of exploring the causes and consequences of tourismification in relation to interest groups. The organisation develops across two primary axes: the vertical accommodates key agencies/actancies and interests. Key agency (human-driven action) and actancy (non-human action) necessitates further division on the basis of who or what produces movement or change in tourism development (or disaster): humans, technologies and natural actants (environments, floral and faunal ecosystems and so forth). These agents/actants are then connected to different clusters of interests (save the economy, social customs, local ecosystems and so forth). The vertical arrangement also spreads across a horizontal axis presenting the three dominant crises: terrorism, climate change/catastrophes and pandemic disruptions. However, on a closer look, the horizontal axis is subjected to cross- and multi-species complexity, because of convergences and divergences in interests across and between actants and agents. We end up with a diagrammatic presentation that reveals more about changes in patterns of movement than spatiotemporal specificities.

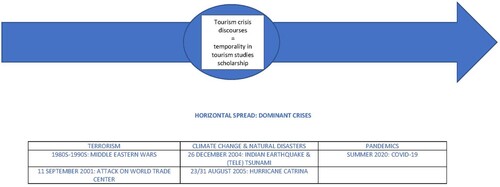

However, it could be argued that the horizontal spread encloses a rough atemporal genealogy of relevant discussions published in tourism analysis academic discourse (). The older crisis trend, that of terrorism, is associated with the late 1980s and the 1990s political turbulence in the Middle East and later on the world-defining event of 9/11, after which terrorist activity becomes an established theme in tourism crisis management. The theme of climate change comes next: at first, this remains submerged in discussions of sustainability at large or dark tourism and volunteer tourism in areas affected by natural disasters. However, the acceleration of natural disasters, especially in the second decade of the twenty-first century, promoted it to an area of analysis in its own right. The crisis caused by pandemics has been circulating in other fields of scientific enquiry for a long time, but it only made a strong appearance in tourism analysis in 2020, with the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). This is the ‘surface discourse’ of the present argument’s ‘temporal contours’.

Mapping the spread of studied or enunciated interests across these three crises provides the first cue to the temporal contours’ submerged (‘deep’) moral codes. The effects of terrorism on tourism destinations are discussed along the lines of regional material losses (including labour losses and infrastructural damages in tourist destinations), cultural isolation (disruptions in tourism’s peace-making impact, sanctions on the affected ‘tourist states’ by international coordinators, including travel bans in high-risk tourismified areas) and psychic/cultural traumas (the withdrawal of hospitality by local hosts, as well as increasing racialisation and mistrust among [Western] visitors). Analyses on the effects of climate change tend to borrow from all the aforementioned consequences. However, a more diverse interest hierarchy emerges from them: where scholars favouring a biopolitical approach to natural disasters may prioritise discussions on the human costs of climate disasters, posthuman tourism studies scholars resort to the presentation of entangled effects and consequences on the earth’s systems (Grimwood et al., Citation2018). Infrastructural costs and the loss of human life or a decline in labour mobilities are now rhizomatically connected not just to the ways climate patterns develop. Damaging natural ecosystems also hurts human life and productivity. Speaking of ‘hurt’ and ‘damage’ endows non-human life with presence and salience in crisis patterns. Finally, the effects of pandemics borrow from all the above registers, to either build arguments on the need to preserve human life without prejudice, or produce an etiological map of climate change, which leads back to human avarice and capitalist exploitation of nature and human populations (Lew et al., Citation2021).

If ‘interests’ can be usefully arranged into biopolitical, ecological and cybernetic (Fuller, Citation2011, Citation2012), the nature of agency and actancy as well as their crossovers may prove to be more challenging to sort into neat categories. It is not just that contingency in human action cannot be reduced to a simple formula of action-reaction, but also that assemblage and actor-network theory question the primacy of human agency in analyses of outcomes in tourism. To ‘map’ variations of ‘worldmaking’ in tourism one may need to place capitalist development next to feedback loops in climate systems, sustainability in employment, and the resilience of technological and infrastructural apparatuses (Sheller, Citation2009). Such sorting proves as difficult as the compartmentalisation of all these forms of agency and actancy. In addition, this may collapse analysis to blame-attribution, and thus the presentation of linear causalities, which lead to the erosion of tourist destinations as environments, communities, and hospitality infrastructures.

It would be useful to have a closer look at the two diagrams, with some examples from the vast literature on crises and/in tourism. Traditional understandings of the impact of terrorist events on tourist destinations commenced with victimological classifications (i.e. examining the status of victims of actual incidents), but slowly moved to critical arguments focusing on the act’s spectacular aspects: the ‘destruction’ of the destination’s (and the nation-state’s) international reputation as a cultural agent (Lutz & Lutz, Citation2018). Dory (Citation2021) usefully divides the relationship between tourism and terrorism in relation to the focus of attacks (including those having tourism as its key target or resulting in tourism-related damages in direct or indirect ways – e.g. when airports are targeted). Significant for the collection of refrains in this article is his observation that ‘the foreign tourist is a kind of “ideal” victim for a terrorist action conceived as a technique of violent communication’ (par. 5). In this respect, ‘vulnerability’ on terrorism-induced crises focuses on economic interests and destination image management (see special issue International Journal of Tourism Cities, 4(4), 2018).

The exploration of ‘damaged hospitality’ from without (by foreign terrorist cells) and within (the tourist destination) informs analyses of terrorism from a heritage tourism perspective (Korstanje & Séraphin, Citation2020). The analytical orientation of such publications bifurcates: on the one hand, terrorism is connected to the risk of destroying heritage destinations; on the other, the very act of terrorism may generate dark tourism (on this duality see special issue, International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 2(1), 2014; Korstanje, Citation2014). A third refrain pertaining to commonalities between tourism and terrorism populates works on state violence (Korstanje & Clayton, Citation2012). Such analyses purport the origins of tourism as a leisure industry in state strategies of labour control, including the pacification of union activism, which in turn are nominated ‘terrorist’ (Korstanje et al., Citation2014; Tzanelli, Citation2011). The last proposition concentrates on foreign tourists as ideal targets, for whom security organisations ought to provide due care (Agarwal et al., Citation2021). We should not lose sight of the panoramic picture in what ‘seems’ to be a collection of disparate arguments: (1) tourism is seen as the maker of a collective image, which is threatened by an ‘outside’; (2) the vulnerable targets are assemblages of humans and architecture; (3) as a crisis, terrorism produces a collective existential nature, with great affective potential (e.g. inducement of fear and insecurity either at home or abroad); finally (4) the ‘loss’ from terrorist activity in tourism contexts retains an ambivalent role as the negation of economic compensation. These refrains are para-digmatic: they ‘point’ at an ethics of care and responsibility for particular social groups and landscapes.

The study of crises, induced by climate change, retain a thin but sure connection to these refrains in the form of a ‘debt’ – this time to ecosystems and future generations. Let us work chronologically towards the crystallisation of these refrains: two special issues in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism published in the first decade of the twenty-first century (14(4), 2006 & 18(3), 2010) call for a responsibilisation of the tourism industry and tourists to significantly reduce global emissions, alongside the need to organise a global research community that produces collaborative and comparative research on these issues. More recently published special issues do not challenge the proposition that tourism is in a state of crisis due to the unsustainable behaviours of individuals and the tourist industry; instead, they either critique ‘business as usual’ or/and move on to propose ‘sustainable’ solutions. When clearly associated with the critical paradigm in tourism analysis, the nexus pushes, directly or indirectly, for material and/or cognitive changes in the ways the tourist industry works (see special issue in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7), 2021). The refrain clearly posits critique as criticism, rather than profit-orientated reflexivity.

Solutions and traps are often identified in the same strategies, such as for example the use of ICTs, which have both promoted sustainable digital travel and produced a new market with its own problems of labour exploitation and hidden pollution costs (Gössling, Citation2021). However, the crux of technology as solution-and-problem sits uncomfortably next to debates on cross-generational debts (‘we ought to hand over a pristine environment to those yet to come’ [Kumm et al., Citation2019]). Unlike arguments clearly directed towards digital travel as an accessible solution for those who are physically immobile (Fennell, Citation2021), the notion of a debt to future human populations presupposes shared interests with those to come. In other words, there is a dissonance in the temporal texture of such suggestions, which is not realistically resolved but envisaged. Where this is not the investigated problem (‘datum’), placing the climate and the disenfranchised in the same bracket, as is the case with some ‘degrowing tourism’ (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., Citation2019) and ‘regenerative tourism’ analyses (Scheyvens & van der Watt, Citation2021) may produce unintended associations with colonial tropes of patronage. Arguments mediating strategies of ‘climate adaptation’ do not always clarify whether the interests of human communities and natural/built environments are balanced vis-à-vis those of industries (Scott et al., Citation2012). In fact, these arguments retain similarities with policies of terrorism prevention in tourist destinations as strategies of economic growth (Coca-Stefaniak & Morrison, Citation2018). It is important to stress that the last two propositions share in the belief that tourism can act not as a collection of imaginaries about place, but a vision of ‘fair globalisation’. If realised, such strategies of growth will allegedly allow for the redistribution of wealth and the spread of democracy, in some cases by liberalising markets and in other by degrowing destinations. In sum, as is the case with the (critical) mobilities paradigm (Sheller, Citation2020, pp. 40–41), in critical tourism studies biopolitics command cybernetics and ‘tame’ existential territories (i.e. hospitableness). Contrariwise, in market-driven publications this schema of subjection and ‘failed development (Sheller, Citation2020) is supposed to offer solutions to the vulnerabilities of systems of tourism services.

The analysis of crises induced by pandemics tends to blend cybernetic, ecological and biopolitical arguments in even bolder ways. Especially between 2020 and 2022, at stake in academic publications has been the viability of tourist industries due to the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic (see special issue in Sustainability, 13, 2021; Ryu, Citation2021). Methodological and case-study publications with a focus on the visitor economy reproduced some familiar themes of risk perception by tourists, as well as the display of resilience in consumption patterns (Han, Citation2021). The new favourite of e-tourism also assumed the mantle of adaptation: in the absence of physical tourism, digital technologies began to ‘move’ both destinations and the prospective tourists’ imagination (see papers in special issues in Tourism Management, 85(4), 2021 & Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(11); Page, Citation2021; Walters & McKercher, Citation2021). The abrupt disruption of tourism mobilities directed attention to the need to ‘reset’ the ways tourism is performed and catered for (Brouder, Citation2020). Portfolios for pragmatic changes in the ways people travel include suggestions to bolster local/domestic travel, ecotourism, agritourism and cybertourism as sustainable solutions. Interestingly, a new trend favoured a model of crisis emergence and management, according to which COVID-19 and the ongoing climate crisis should be studied analogically (Gössling et al., Citation2021; Tzanelli, Citation2021a). Among the most sophisticated special issues stands one published in Tourism Geographies (22(3), 2020), with a call to think positively about cycles of resilience to adversity (see introductory article by Lew, Cheer, Haywood, et al., Citation2020). However, what ‘resilience’ stands for is morally active in ways not spelled out.

Thus, the moral-philosophical underpinnings of such suggestions merit further consideration. Firstly, the status and nature of beneficiaries from such changes is not as anthropocentric as before, due to the reorientation of solutions to a world of posthuman movement and interdependency. Secondly, the rhythm of consumption that these propositions favour is also slower than that of more established automobility-driven tourism. Some of the publications in this stream continue to address the importance of maintaining a multi-sensory approach to tourism, resembling the Italian philosophy of slow tourism (cittaslow – Fullagar et al., Citation2012), which favours contact with nature and sustainable local-global connectivity (Houge Mackenzie & Goodnow, Citation2020). The emphasis on embodied performance in even more intense ways than those that originally featured in the new wave of tourism analysis (e.g. Edensor, Citation2000, Citation2001a, Citation2001b) is intriguing, given that pandemic restrictions foreclosed or monitored such activity in tourism settings. Other publications resort to filtering the tourist experience through an allegedly pedagogical gaze (Gretzel et al., Citation2020). In the latter cases, ‘slow’ is equated with an ethical pragmatics of digital distance (e.g. Lapointe et al., Citation2020; Tzanelli, Citation2021a), which may be wrongly assumed to be more sustainable than embodied travel, given the actual environmental cost of digital footprint (Levy & Spicer, Citation2013).

Because refrains produce not just scholarly worlds of tourism but also the styles in which such worlds ‘dance’ the world to a future, it is appropriate to conclude this section with a special issue published in the Journal of Tourism Futures (7(3), 2021) under the title ‘Tourism in crisis: global threats to sustainable tourism futures’. Although the theme of crisis is filtered through the window of COVID-19, the actual contributions cut across the refrains used in all three dominant crises explored in this article. The keywords used in the editorial article are telling: biopolitics, risk society, political ecology, COVID-19, tourism recovery, tourism justice. Indeed, the editorial article plots futuristic enunciations in a style conforming to the rules of forward movement that is unpacked in the following section. The scholarly voices that weave the plot commence with Beck’s quintessential constructivism in ‘risk society’ (Beck, Citation2006), which is openly debated as ethico-political and anthropocentric and conclude with justice frameworks. The spotlight is turned ‘on the structural inequalities and violent social reproduction of subalternities’ in the Anthropocene (Cheer et al., Citation2021, p. 290). At this stage, questions emerge concerning the affective core not of what is brought to light, but the community that stages its polemics.

The worldmaking meta-refrain

Movement to the future

It would be absurd to argue that scholarship on tourism futures has no moral/ethical or political commitment after this presentation of crisis refrains. The question is how to evaluate such stances in dispassionate ways that illuminate what is considered vulnerable and how viabilities in tourism are envisaged. Given the introduction’s engagement with worldmaking, it is appropriate to backtrack to Hollinshead and Vellah’s (Citation2020) discussion of the Deleuzean emergist nature of postcolonial identities in tourism destinations. The stance Hollinshead & Vellah adopt exemplifies Mannheim’s ‘documentary’ method, while also providing the temporal contours (as per Stern, Citation2004) of an emancipatory future (or a hopeful version of the future after colonial domination). This camera-like vision featured in Urry’s (Citation2016) magnum opus on visions of the future without Mannheim’s solid generational analysis. Note also that Hollinshead and Vellah’s (Citation2020) Weltanschauung is not factual but virtual, because it relies on hopeful affect: what becomes a reality in the future emerges, so we can hope and plan, but cannot predict with assurance or precision. This introduces anti-rational elements in their analysis associated with ideology, but it also endorses social transformation, as their proposition has an orientation toward goals which are not yet attainable in reality. So, instead of disconnecting established paradigms on tourism in crisis or the end of tourism, outlined above from utopias and imaginaries, it is better to clarify the relationship between them. In a recent special issue on affective attunements in tourism studies, Germann Molz and Buda (Citation2022, p. 189) explain that ‘affect is corporeal’, ‘but in the sense that it circulates in between rather than residing within individual bodies’. Before tourism studies scholars learn to hope together, as an epistemic community or a collective body, they must discover that they are bound by the same affective movements into the future. Tourism utopias provide the contours of a type of imaginary ideal society – how society should be but is not yet. As such, they prompt an investigation of the ‘temporal texture’ in which they operate as a future diagnostic (Stern, Citation2004).

The ‘problem’ (or ‘sociological datum’) in last section’s refrains is how they are enunciated from an epistemological stance, which favours the dominant arguments by John Urry (Citation1990; Urry & Larsen, Citation2011) and Keith Hollinshead (Citation1999, Citation2009b), when vulnerability and viability are ontological issues. Indeed, these are the two poles of analysis that merit critical consideration. As the special issue in the Journal of Tourism Futures suggests, such bifurcated enunciations are biopolitical in nature, even though their ontological basis remains moral and not dispassionate (if there is such a thing). Especially tourism studies academics, who refute the primacy of economics in tourism development in the age of crises and extinction, understandably feel compelled to address what happens to (human or multi-species) becomings, alongside how they/we can study them. Otherwise put, the temporal texture of critical and interpretivist paradigms in tourism hides an affective commitment to ontogenesis, which clashes with the original epistemological framework of tourism as an ‘ER field’ in which patients are subjected to expert scrutiny. However, the age of crises and extinction cannot afford the excision of the expert from its material and existential territories: we are part of the picture we study in visceral ways that produce affective (intrinsic) knowledge. This calls for the resurgence of community in the ways crises are studied subjectively (by scholars) and objectively (as an object of study). Such themes are not alien to tourism analysis in frameworks propagating tourism as a ‘cosmopolitan vista’ (Swain, Citation2009), but the nature of this vista is taken for granted.

Karl Mannheim’s (1893–1947) magnum opus on utopia provides some helpful analytical tools to unpack this resurgent conservatism with a small ‘c’. One of the Frankfurt School scholars and a prominent sociologist of knowledge, Mannheim never featured in tourism analysis. Mannheim’s materialist phenomenology is epistemologically more sophisticated than Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s blended Weberian/Marxist/Freudian thesis on the dialectic of Enlightenment. It also facilitates connections to post-structuralist analyses of the ways identities and subjectivities are formed in the flux of research (Latour, Citation1987). Also, Mannheim’s work on the relationship between utopia and ideology stands at the heart of the present discussion on academic refrains and existential territorialisation in tourism analysis. His starting point is a temporal differentiation between conservative ideological formations, which are static and backward-looking, to ensure the preservation of tradition, and utopias, which are forward-looking and propagating change (Mannheim, Citation1936/1968). The notion of ‘categorical style’ in tourism analysis introduced at the start of the article matches what Mannheim distributes across ideological and utopian formations as forward or backward-looking visions in tourism planning. For those who want to equip epistemological statements with methodological tools, such ‘categorical styles’ can be known and studied in three ways, according to Mannheim (Citation1952): intrinsically or objectively (without investigating the motivation of those who uphold them), extrinsically or subjectively (through the ways they express/externalise them) and documentarily (through textual or third-party accounts). Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1988) as well as Guattari (Citation1989/Citation2000) invite a blend between these categories but emphasise the importance of the second as a meta-field of investigation (the existential territory).

Let us return now to the refrains in recent publications on crisis in/of tourism: in terms of temporality, their worldviews project one type of movement to the future but uphold at least two styles. When they adopt a critique of biopolitics, the analyses move backwards first, to establish genealogical accounts of inequalities; in terms of interests, this arc is mostly anthropocentric and anchored on effects of fairness, rather than fully articulated justice. Within this refrain, another group of arguments does not really attempt to ‘reset’ the world, only to show the state of human affairs at a particular moment in time. Such analyses are prominent in the cognate field of hospitality studies and have stronger connections to terrorism management, whereas the more recent work on climate change and pandemics tends to revive the affective tropes of hope. Yet, when coupled with understandings of resilience in blended scholarship-locality contexts, all these approaches fuse notions of preservation/conservation of material and immaterial heritage (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Citation1997) with the viability of futural forms of (posthuman or anthropocentric) life. As Kirshenblatt-Gimblett has explained, the ‘production of hereness’ in the absence of the actuality of heritage ‘depends increasingly on virtualities’ (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Citation1997, p. 169). The cybernetic project recedes in the background and is functionalised (to remain ‘useful’ to future generations of thinkers and doers of viable futures).

Tourism analyses on climate change and pandemics oscillate between communicating a feeling that an end approaches humanity (of environmental equilibriums, world peace or a pestilence-free earth, to stick to the three aforementioned dominant crises). The same or similar theses proffer ‘solutions’ to these disasters and policies of risk minimisation, adopting a salvaging stance. However, policy-making in publications is not where the true arc or meta-refrain rests: where an end is felt or pronounced, hope is resurrected among the epistemic communities that produce collections of critical special issues, monographs, and collective volumes (Tzanelli, Citation2021b). The catastrophist imaginary that forewords scholarly political commitment to a better world, free of prejudice, pollution and inequalities continues to be biopolitical even when it pronounces its support of pro-environmental causes. It could be argued that even the emergence of environmental humanities as a field served the same purpose: under an allegorical pretence to examine nature or the environment, it forms an epistemic basis of a community of interest.

Instead of concluding: the worlds know no ‘End’

French philosopher Paul Ricoeur (Citation1986) once suggested that the only way to escape the circularity of ideology, which keeps the world from changing, is to assume a utopian stance and judge ideology on this basis. Assuming the position of an onlooker (what Mannheim called a ‘free-floating intellectual’ or ‘extrinsic researcher’) is pragmatically impossible. To move from Hollinshead & Vellah’s virtual subjectivisation (i.e. the making of the tourist subject that ‘worldmakes’) to the pragmatic field of scholarly worldmaking, we may need to acknowledge a few inconvenient truths about our dominant epistemic role in crisis management as a species. For this, a shift to what Anna Tsing calls ‘world-making’ is useful. This involves the ways ‘projects’ emerge from practical activities of making lives ‘in the shadow of the Anthropocene’ (Citation2015, pp. 21–22). Tsing’s conception of world-making as a lay, practical activity, differs from Hollinshead’s (Citation2009a) emphasis on the authorial role of the nation/tourist state but mediates Hollinshead and Suleman’s (Citation2018) thesis on the ways worldmaking is instilled or normalised in everyday activities in tourism. However, taking a look inwards, reflecting on the ways epistemic-academic communities think about such projects leaves one with no outside. As much as Ricoeur’s proposition forges an anti-ideological polemics (against capitalism, state and corporate violence, ordinary human insensitivity towards the other and so forth), one must not lose sight of a peculiar convergence in antithetical refrains.

Both ideological and utopian propositions concerning the future of the world (and of worlds of tourism) favour a gaze which is cast upon variations of otherness: natural environments, disadvantaged human populations and failing industrial formations. The very nature of scholarship as a godly spectre over reality produces a meta-movement that takes place in one’s mind. It is unnecessary to repeat the old observation that especially critical theorists tend to assume the role of an infallible expert in the enunciation of problems that affect the world at large. In any case, such critiques of critique can also be reductive. In fact, it matters more to stress that (a) the primary antithetical binary of the tourist body versus tourist gaze or mind has been matched with that of tourist performance/authenticity versus contemplation/inauthenticity respectively and (b) this scaffolding cannot be excised from problematic moralistic divisions between action and spectatorship in crisis management. The scaffolding originates not in Foucault’s biopolitical thesis but the conditions of ‘total war’ and state violence discussed by Hannah Arendt (Arendt, Citation1958).

In the age of climate catastrophe, terror and pandemics, action becomes fetishised in a variety of ways that cannot neatly separate pro-environmental calls for a return to ‘Mother Nature’ or earth from a Hobbesian state of nature: we worked hard as a species to acquire all this technology to master an unfriendly planet, and here we are, wanting to bin it all in eco-friendly manifestos. Unfortunately, the promise of holistic philosophies underpinning post-humanist communitarianism (i.e. we are part of a larger-than-us whole) may also hide ecofascistic traps that recuperate total ideologies. Being eco-friendly can also be exclusionary and dangerous in other words. Ecofascism in climate change tourism solutions can also reproduce what ecologists call ‘Rapoport’s Rule’: less biodiverse environments mostly in temperate climate zones, are (unjustly, apparently) inhabited by species, such as humans and cockroaches, which can survive in other zones too, thus crowding and eliminating other local species (Fuller, Citation2006, pp. 184–135). This is an unfortunate reading of natural economy as a disturbed equilibrium between species and individuals, which turns posthuman collaborations into guilt games targeting particular groups, usually from the middle social strata. Such groups often act in tourism networks as supporters of various local causes, promoting variations of tourism amenable to development without always combating inequality (e.g. volunteer tourism – Mostafanezhad, Citation2016).

It is worth concluding with a few concise observations on the meta-refrain these three crises in tourism sustain in academic circles – their unitary ‘worldmaking arc’, so to speak. First, the scholarship that enunciates their aims presents an ambivalent attitude towards globalisation: on the one hand, it opposes the inequalities it generates and thus its spirit, which is that of unrestrained capitalist development. On the other, it supports tourism, which is one of its offshoots. It is important to stress for example how Irina Ateljevic’s (Citation2009, Citation2013, Citation2020) mobilisation of Enrique Dussel’s liberation theology refuses to turn tourism into an ‘criminal suspect’ in discourses of development. Her strategy, as is the case with others, is pragmatic: it aspires to subvert its system from within, by handing over its operative structures to those it initially harmed. In short, critical tourism’s de-theologised pragmatics of ‘thinking small’ and sustainably do not fully operate outside development but tend to favour communitarian models that support diversity.

The second aspect of this ambivalence towards globalisation is rooted in the nature of the movement such scholarship generates, which develops out of many ‘anarchic’ intellectual enclaves with quite different agendas. Although their worldmaking enunciations may project such disparate propositions to make better futures in tourism, with the exception of the integrationist futurism of traditional ‘business as usual’ tourism economics theorists, all other enclaves imagine themselves as part of a ‘commons’ that can induce the capitalist system’s destruction. This connects institutional-tourist imaginaries of the future to the utopian project of what Hardt and Negri (Citation2004) call the ‘multitude’: a counter-hegemonic movement of Marxist overtones which can challenge capitalism’s deterritorialised forces of persuasion. This will be achieved through an equally mobile counter-force sustaining local causes in the face of relentless homogenisation. This adumbrates the affective nature of the article’s meta-refrain as one of solidary com-passion: feeling-as-suffering (páthos) and thus affectively being together in tough times (see again Cheer et al., 2021 on ‘resilience’). It is fair to note that this type of worldmaking belongs to the domain of the ‘not yet’ possible, so it offers less in terms of concrete (‘viable’) futural planning. However, it addresses a crucial vulnerability in academic scholarship on tourism futures, which is generated by the very origins of tourism in global economic systems. Its revising potentiality connects to the very production of resurgent sympathetic communities that feel (Ahmed, Citation2004). Regardless of its vision of creating a better life for all sentient beings on earth, this meta-refrain’s enunciative channels continue to be human.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rodanthi Tzanelli

Rodanthi Tzanelli is an Associate Professor of Cultural Sociology and Director of the Mobilities Area in the Bauman Institute, University of Leeds, UK. She is a social and cultural theorist of mobility (tourism, technology, social and academic movements) with particular reference to the representational contexts of contemporary crises such as climate change, consumption and capitalism. She is the author of numerous critical interventions, research articles and chapters, as well as 15 monographs.

References

Individual references

- Agarwal, S., Page, S., & Mawby, R. (2021). Tourist security, terrorism risk management and tourist safety. Annals of Tourism Research, 89, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103207

- Ahmed, S. (2004). Cultural politics of emotion. Routledge.

- Arendt, H. (1958) The human condition. University of Chicago Press.

- Ateljevic, I. (2009). Transmodernity – remaking our (tourism) world? In J. Tribe (Ed.), Philosophical issues in tourism (pp. 278–300). Elsevier.

- Ateljevic, I. (2013). Transmodernity: Integrating perspectives on societal evolution. Futures, 47(March), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2013.01.002

- Ateljevic, I. (2020). Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re)generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 467–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759134

- Beck, U. (2006). Living in the world risk society. Economy and Society, 35(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140600844902

- Bertelsen, L., & Murphie, A. (2010). An ethics of everyday infinities and powers: Felix Guattari on affect and the refrain. In M. Gregg & G. J. Seigworth (Eds.), The affect theory reader (pp. 138–160). Duke University Press.

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Athlone.

- Dory, D. (2021). Tourism and international terrorism: A cartographic approach. Via, 19, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.4000/viatourism.7243.

- Edensor, T. (2000). Staging tourism: Tourists and performers. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 322–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00082-1

- Edensor, T. (2001a). Performing tourism, staging tourism: (Re)producing tourist pace and practice. Tourist Studies, 1(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879760100100104

- Edensor, T. (2001b). Walking the British countryside: Reflexivity, embodied practices and ways to escape. In P. MacNaughten & J. Urry (Eds.), Bodies of nature (pp. 81–106). SAGE.

- Fennell, D. A. (2021). Technology and the sustainable tourist in the new age of disruption. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1769639

- Fullagar, S., Wilson, E., & Markwell, K. (2012). Starting slow: Slow mobilities and experiences. In S. Fullagar, K. Markwell, & E. Wilson (Eds.), Slow tourism: Experiences and mobilities (pp. 1–11). Channel View.

- Fuller, S. (2006). The new sociological imagination. SAGE.

- Fuller, S. (2011). Humanity 2.0. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fuller, S. (2012). The art of being human: A project for general philosophy of science. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 43(1), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-012-9181-5

- Germann Molz, J., & Buda, D.-M. (2022). Attuning to affect and emotion in tourism studies. Tourism Geographies, 24(2-3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.2012714

- Gössling, S. (2021). Tourism, technology and ICT: A critical review of affordances and concessions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(5), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1873353

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, M. C. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gretzel, U., Fuchs, M., & Baggio, R. (2020). E-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00181-3

- Grimwood, B. S. R., Caton, K., & Cooke, L. (2018). New moral natures in tourism. Routledge.

- Guattari, F. (1989/2000). The three ecologies. Bloomsbury.

- Guattari, F. (1992/1995). Chaosmosis: An ethico-aesthetic paradigm. Indiana University Press.

- Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2004). Multitude: War and democracy in the age of empire. Penguin.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Carnicelli, S., Krolikowski, C., Wijesinghe, G., & Boluk, K. (2019). Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1926–1944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1601732

- Hollinshead, K. (1999). Surveillance of the worlds of tourism: Foucault and the eye-of-power. Tourism Management, 20(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00090-9

- Hollinshead, K. (2009a). ‘Tourism state’ cultural production: The re-making of Nova Scotia. Tourism Geographies, 11(4), 526–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903262737

- Hollinshead, K. (2009b). The “worldmaking” prodigy of tourism: The reach and power of tourism in the dynamics of change and transformation. Tourism Analysis, 14(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354209788970162

- Hollinshead, K., & Suleman, R. (2018). The everyday instillations of worldmaking: New vistas of understanding on the declarative reach of tourism. Tourism Analysis, 23(2), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354218X15210313504553

- Hollinshead, K., & Vellah, A. B. (2020). Dreaming forward: Postidentity and the generative thresholds of tourism. Journal of Geographical Research, 3(4), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.30564/jgr.v3i4.2299

- Houge Mackenzie, S., & Goodnow, J. (2020). Adventure in the age of COVID-19: Embracing microadventures and locavism in a post-pandemic world. Leisure Sciences, 43(1-2), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773984

- Ibn-Mohammed, T., Mustapha, K. B., Godsell, J., Adamu, Z., Babatunde, K. A., Akintade, D. D., Acquaye, A., Fujii, H., Ndiaye, M. M., Yamoah, F. A., & Koh, S. C. L. (2021). A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 164 (105169), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169.

- Jennings, G. R. (2012). Methodologies and methods. In T. Jamal & M. Robinson (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of tourism studies (pp. 672–692). SAGE.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1997). Destination culture. University of California Press.

- Korstanje, M. E. (2018a). The mobilities paradox: A critical analysis. Edward Elgar.

- Korstanje, M. E. (2018b). Terrorism, tourism and the end of hospitality in the west. Springer.

- Korstanje, M. E., & Clayton, A. (2012). Tourism and terrorism: Conflicts and commonalities. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 4(1), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554211211198552

- Korstanje, M. E., & Séraphin, H. (2020). Tourism, terrorism and security. Emerald.

- Korstanje, M. E., Skoll, G., & Timmermann, F. (2014). Terrorism, tourism and worker unions: The disciplinary boundaries of fear. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 2(1), https://doi.org/10.21427/D7HQ6C. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol2/iss1/4.

- Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- Kumm, B., Berbary, L., & Grimwood, B. S. R. (2019). For those to come: An introduction to why posthumanism matters. Leisure Sciences, 41(5), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2019.1628677

- Lapointe, D., Sarrasin, B., & Lagueux, J. (2020). Management, biopolitics and foresight: What looks for the future of the world? Teoros, 39(3), https://doi.org/10.7202/1075019ar. http://journals.openedition.org/teoros/8407.

- Latour, B. (1987). Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Open University Press.

- Levy, D. L., & Spicer, A. (2013). Contested imaginaries and the cultural political economy of climate change. Organization, 20(5), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413489816

- Lew, A. A., Cheer, J. M., Brouder, P., & Mostafanezhad, M. (2021). Global tourism and COVID-19. Routledge.

- Lutz, B. J., & Lutz, J. M. (2020). Terrorism and tourism in the Caribbean: A regional analysis. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 12(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2018.1518337

- Mannheim, K. (1936). Ideology and utopia: An introduction to the sociology of knowledge. Harvest Book/Harcourt Inc.

- Mannheim, K. (1952). Essays on the sociology of knowledge. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Massumi, B. (2002). Parables of the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Duke University Press.

- Mostafanezhad, M. (2016). Volunteer tourism: Popular humanitarianism in neoliberal times. Routledge.

- Munar, A. M., & Jamal, T. (2016). What are paradigms for? In A. M. Munar & T. Jamal (Eds.), Tourism research paradigms (pp. 1–16). Emerald.

- Okafor, L. E., Khalid, U., & Burzynska, K. (2022). Does the level of a country's resilience moderate the link between the tourism industry and the economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Current Issues in Tourism, 25(2), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1956441

- Ricoeur, P. (1986). Lectures on ideology and utopia. Columbia University Press.

- Rosenberger, R., & Verbeek, P.-P. (2015). A field guide to postphenomenology. In R. Rosenberger & P. P. Verbeek (Eds.), Postphenomenological investigations (pp. 9–41). Books.

- Scheyvens, R., & van der Watt, H. (2021). Tourism, empowerment and sustainable development: A new framework for analysis. Sustainability, 13(22), 12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212606

- Scott, D., Hall, C. M., & Gössling, S. (2012). Tourism and climate change: Impacts, adaptation and mitigation. Routledge.

- Sheller, M. (2009). Infrastructures of the imagined island: Software, mobilities and the architecture of Caribbean paradise. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(6), 1386–1403. https://doi.org/10.1068/a41248

- Sheller, M. (2020). Island futures: Caribbean survival in the Anthropocene. Duke University Press.

- Stern, D. N. (2004). The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. W.W. Norton & Co.

- Swain, M. (2009). The cosmopolitan hope of tourism: Critical action and worldmaking vistas. Tourism Geographies, 11(4), 505–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903262695

- Tribe, J. (2001). Research paradigms and the tourism curriculum. Journal of Travel Research, 39(4), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750103900411

- Tsing, A. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

- Tzanelli, R. (2011). Cosmopolitan memory in Europe’s ‘backwaters: Rethinking civility. Routledge.

- Tzanelli, R. (2021a). Cultural (im)mobilities and the Virocene: Mutating the crisis. Edward Elgar.

- Tzanelli, R. (2021b). “Post-viral tourism’s antagonistic tourist imaginaries”. Journal of Tourism Futures, 7(3), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-07-2020-0105

- Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze (1st ed.). SAGE.

- Urry, J. (2016). What is the future? Polity.

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. SAGE.

Special issues

- Cheer, J.M., Lapointe, D., Mostafanezhad, M. & Jamal, T. (Eds.) (2021) Tourism in crisis: global threats to sustainable tourism futures. Journal of Tourism Futures, 7(3). https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/issn/2055-5911/vol/7/iss/3

- Coca-Stefaniak, A. & A.M. Morrison (Eds.) (2018). ‘City tourism destinations and terrorism’. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 4(4). https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/issn/2056-5607/vol/4/iss/4

- Han, H. (Ed.) (2021). ‘Sustainability and consumer behavior’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7). https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rsus20/29/7

- Korstanje, M.E. (Ed.) (2014). ‘Tourism and terrorism’. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 2(1). https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol2/iss1/

- Lew, A., Cheer, J., Brouder, P. Teoh, S., Balslev Clausen, H., Hall, M., Haywood, M., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Lapointe, D., Mostafanezhad, M., Mei Pung, J. & Salazar, N. (Eds.) (2020). Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tourism Geographies, 22(3). https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rtxg20/22/3

- Page, S. (Ed.) (2021). ‘Compilation of Covid-19 and tourism papers’. Tourism Management, https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/tourism-management/special-issue/10LQNSMGXDN

- Ryu, K. (Ed.) (2021). 'Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the hospitality and tourism industry'. Sustainability, 13. https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/tourism_sus

- Walters, G. & McKercher, B. (Eds.) (2021). Where to from here? COVID 19 and the future of tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(11). https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rapt20/26/11