ABSTRACT

Legitimacy is a fundamental dimension of co-creation as it determines the desirability, suitability, and appropriateness of individuals or organisations in any community. This research explores how users establish legitimacy when co-creating value in online travel communities. The proliferation of online communities propels a bottom-up approach to legitimacy that resides at the micro level within online contexts and can be achieved through discursive legitimacy. The research context focuses on travellers during the COVID period and the online customer-to-customer (C2C) community they formulated. Travellers’ posts were analysed based on thematic analysis. Findings reveal the five discursive legitimation strategies used to legitimate or delegitimate proposed co-creation practices in tourism, namely: authorisation, rationalisation, trustification, normalisation and narrativisation. These were employed by multiple online users to influence travellers and were associated with discursive resources (technology affordances) to support narratives during times of contestations. The discursive strategies aided in creating two levels of customer-to-customer value co-created experiences. This research moves away from the dominant institutional approach to provide a novel understanding of legitimacy in tourism: discursive legitimacy, which is more relevant for online customer-to-customer (C2C) travel communities' co-creation practices.

Introduction

The United Nations World Tourism Organisation (Citation2022) urges travellers to be aware of online interactions and engage in legitimate practices when co-creating online. There has been increasing reports of fake profiles, purchases and reviews in online travel marketplaces (Peterkin et al., Citation2022; Xu et al., Citation2020). TripAdvisor (Citation2022) removed or rejected more than two million reviews of which almost 40% were deemed to be biased or fraudulent. Destinations such as Puerto Vallarta in Mexico has experienced a 200% increase in fraud as tourists are being sold fake vacation packages (Traveloffpath, Citation2022). In response, businesses have increased their structures for monitoring, harnessing the power of artificial intelligence and context moderators to protect travellers when interacting online.

While initiatives are being implemented at a business-to-tourist level, there are also micro-interactions on a customer-to-customer (C2C) or traveller-to-traveller (T2 T) level. Online communities have been ranked as the most important group during the COVID-19 crisis (TheGovLab, Citation2021). Individuals need to also exercise caution in these environments as they continue to be subject to a number of risks that cause them distress and unpleasant travel experiences (Assiouras et al., Citation2023). Unlike organisation-led online platforms, these communities have challenges with ensuring safety as they are decentralised public spheres with anonymous individuals and hence cannot be easily monitored. Ongoing conversations allow individuals to position themselves as legitimate. Users should be mindful of the discursive tactics used for attaining (il)legitimacy on these platforms for fostering co-creation (Talwar et al., Citation2020).

Legitimacy refers to an individual or organisation being ‘desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions’ (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 574). Edvardsson et al. (Citation2011), in their conceptual paper on a social construction, approach to value co-creation identified legitimacy as being a part of the social structures for understanding co-creation. Legitimacy has mainly been explored in the context of community-based tourism (Jamal & Getz, Citation1995; Wang et al., Citation2018), ecotourism (Phillips, Citation1997), film (Bertolini et al., Citation2021), gaming development (Wong et al., Citation2019) and backpacker literature (Farrelly, Citation2021). The introduction of technologies has necessitated a shift in how legitimacy is explored (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021). Online communities provide networked environments for generating practices underpinned by discursive legitimacy (Kavoura & Buhalis, Citation2022; Castello et al., Citation2016; Etter et al., Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2015; Mendoza et al., Citation2021; Veil et al., Citation2012). However, legitimacy, as a dimension of co-creation, remains largely unexplored in tourism. The literature on legitimacy in online environments in hospitality and tourism and business is still lacking (Antretter et al., Citation2019).

This research examines how users establish legitimacy when co-creating online by examining an online travel community. The study (1) explores the discursive legitimation strategies applied by travellers of the online community for influencing others, (2) identifies the co-created practices in the online community that are linked to these strategies, and (3) presents the affordances that are drawn on by users to support their narratives. The research investigates the online travel community of Nina Island South Inmates WhatsApp group, which was created in 2020. The group was user-driven as it was formed by travellers online who stayed at Nina Island South Hotel. It later expanded to embrace travellers to Hong Kong, amassing over 100 users. It developed at a time when there was significant concern for (il)legitimate online travel posts and lack of information (Kelleher, Citation2021). Users credit the WhatsApp group as a viable platform to receive factual information during the COVID infodemic (SCMP, Citation2021). This research illustrates discursive legitimacy as a key aspect in online tourism contexts, specifically online travel communities. The study contributes to co-creation in tourism literature by exploring the dimension of legitimacy in co-creation.

Co-creation not only results in enhanced tourism experiences but is also necessary for instilling legitimacy in online communities. The base idea is that legitimacy is socially constructed, dependent on social structures. Hence, there are the strategic management and institutional theory views embraced in tourism, which propose that organisations use these normative structures and procedures to signal legitimacy in organisational behaviours. Building on this observation, this paper proposes that legitimacy is not solely socially constructed, but rather social constructions constituted through discourse or verbal interactions. It is managed based on communication, as individuals deploy verbal explanations to garner legitimacy (Phillips et al., Citation2004). Legitimacy is established through an ongoing verbally interactive (communicative) process. This way of managing legitimacy is usually tied to individuals (Elsbach, Citation1994). This paper moves away from the dominant view of legitimacy as a resource embedded in individuals or organisations. It proposes a novel perspective-discursive legitimacy, whereas legitimacy is seen as a process shaped by multiple stakeholders (Suddaby et al., Citation2017).

Literature review

Co-creation in tourism and online travel communities

Co-creation is a collaborative process of producing value among resource integrators (Vargo et al., Citation2008). It is a well-cited concept in tourism research to explore both physical and virtual environments (Arıca et al., Citation2023; Mohammadi et al., Citation2021; Leal et al., Citation2022). A variety of terms have been applied in tourism to describe co-creation in virtual environments. Terms include online co-creation, mobile co-creation, virtual co-creation, IT-enabled co-creation and real time co-creation (Lei et al., Citation2022). These experiences are technology-enhanced tourism experiences for facilitating interactions and producing value (Neuhofer et al., Citation2014). Online travel communities facilitate these experiences of extensive interactions that are constant and ongoing (Buhalis & Foerste, Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2017). These communities are ‘social aggregations that emerge from the Net when enough people carry on those public discussions long enough, with sufficient human feelings, to form webs of personal relationships in cyberspace’ (Rheingold, Citation1993, pp. 57–58). They provide members with the opportunity to ascertain information, garner socio-psychological and hedonic benefits (Chung & Buhalis, Citation2008).

Users visit online communities to share knowledge, experiences and contact information for tourist customer-to-customer (C2C) co-creation (Arıca et al., Citation2023; Oliveira et al., Citation2020). This refers to interactive practices among tourists for generating value (Rihova et al., Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2015). Interactions can occur at four layers, namely: detached, is less socially immersive and focuses on single customers who may refer assistance but still engage in activities privately; social bubble focuses on customers who share consumption experiences; communitas is based on temporary communities that share a sense of togetherness and solidarity (Johnson & Buhalis, Citation2023); and neo-tribes are collectives that are associated with particular brands and activities (Rihova et al., Citation2013). Co-creation is often seen as only an interactive process to collaboratively create and/or enhance experiences (Herrmann-Pillath, Citation2020). However, there are other forms of value that can emerge particularly in technology networks, which are yet to be unravelled such as legitimacy (Massi et al., Citation2021).

Online co-created experiences are shaped by social context. For instance, technological infrastructures, such as affordances, can be drawn on by users during co-creation on social media platforms (Ge & Gretzel, Citation2018). Lei et al. (Citation2019) unravelled the contextual factors affecting organisation and individual interactions. These are individual characteristics; trip characteristics and computer-mediated communication characteristics. While prior studies focus on how technical and non-technical resources of online platforms bind actors together for co-creation, there is limited understanding of how these online communities in which these actors are based obtain legitimacy, that is, acceptance beyond resources. There is need to further expand on social aspects and specifically the importance of legitimacy, which is embedded in social structures of value co-creation (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016). Edvardsson et al. (Citation2011), noted that co-creators are influenced by social structures, such as legitimation. Individuals within the co-creation process must be deemed acceptable (Grace & Iacono, Citation2015). Pfeffer and Salanick (Citation1978) argue that legitimacy is controlled by publics. However, there is a lack of studies in tourism on legitimacy and co-creation among individuals and even so online, which is unlike business studies, which pay much attention on co-creation online and legitimacy of stakeholders (Illia et al., Citation2023).

Edvardsson et al.’s (Citation2011) work on the social structures of value co-creation such as legitimation draws on Gidden’s (Citation1984) work on structuration. Stakeholders engage in co-creation by embracing these four building blocks: dialogue, access, transparency and risk (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). Dialogue has become increasingly possibly for tourists who engage within online communities thereby facilitating customer-to-customer co-creation virtually (Williams et al., Citation2015). However, Roiseland (Citation2022) argues that while co-creation enables wide participation and dialogue, only a limited number of actors are usually listened to and acknowledged as being acceptable for sharing information. Centeno and Wang (Citation2017) are one of the few scholars who have illustrated the connection between value co-creation and legitimacy for at the individual (micro) level. They find that celebrities employ communicative strategies for validating their content, such as sharing their visions and aspects of their personal lives. Celebrities are seen as entrepreneurs and are not reflective of the everyday online users, who are enrolled in participant-driven platforms. These influencers individuals gain legitimacy through embodying cultural norms, which aligns with Suchman’s (Citation1995) view of legitimacy. However, Suchman (Citation1995), who is widely embraced by tourism scholars, does not focus on individual legitimacy but instead emphasis the strategies for acceptance by corporations (Arnould & Dion, Citation2022; Elsbach, Citation1994). Individuals are bounded by institutional structures thereby limiting agency (Edvardsson et al., Citation2011). Co-created activities are highly agential and collaborative in networks (Melis et al., Citation2022; Thomas & Ritala, Citation2022) and particularly in online media contexts where discursive legitimacy is salient (Glozer et al., Citation2019).

Participation in online co-creation has meant that individuals, not just organisations and celebrities, are expected to legitimise their actions in these communities due to the misinfodemic. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted global tourism and changed the co-creation context dramatically (Assiouras et al., Citation2023; Liu et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2021). Since the pandemic a stigma emerged towards interacting in virtual networks; as they are not deemed to be equally acceptable as in-person interactions. Online users have been asked to adopt strategies that can allow them to detect false users and narratives.

Online environments require legitimacy to overcome mistrust from possible and prospective users (United Nations, Citation2022). Online communities have an array of diverse users making it challenging to establish legitimacy (Fisher et al., Citation2017). They suffer from the liability of newness-being perceived as new rather than well-established, reliable means of co-creating (Snihur et al., Citation2018). These communities also do not conform to official guidelines by technology companies, by which their legitimacy could have been judged. Instead, they are unregulated and rely mostly on discourse; namely texts and symbols used in conversation (Phillips et al., Citation2004). Online communities are sites of negotiation, which means discourse and legitimation strategies can vary across contexts (Suddaby et al., Citation2017). Thomas and Ritala (Citation2022) conclude that there is need for studies on how these communities acquire legitimacy.

Legitimacy in tourism

Legitimacy as a concept was mainly derived from sociology studies and has filtered into business research (Parsons, Citation1960) as well as tourism (Richter, Citation1980). Tourism studies have extensively examined strategies for portraying organisational (Foley, Citation2003; Wang et al., Citation2018) and individual legitimacy (Adongo & Kim, Citation2018). It is a tool, which individuals and businesses can possess and use. This understanding associates with a functionalist or strategic perspective (Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990; Blanco-González et al., Citation2021). This view is underpinned by institutional theory, which signifies that legitimacy is based on external conditions such as rules and values (Suchman, Citation1995). Adherence to laws can make an organisation appear more or less valid (Powell & DiMaggio, Citation2012). However, this view is limited (see ).

Table 1. Types of legitimacy.

Suddaby et al. (Citation2017) explain that there are two streams of research: legitimacy as a property (a resource, a capacity, an asset) underpinned institutional theory; and legitimacy as a process. ‘The process perspective is, necessarily, multilevel because social construction assumes interactions and reciprocal influences between the individual and collective levels of analysis’ (Suddaby et al., Citation2017, p. 462). Legitimacy is seen as a social construction. It is not a stable condition but instead the result of an ongoing process that must be exercised as it is continually being negotiated and contested (Antretter et al., Citation2019). It is a process of influence or persuasion through language, hence, it is found within intersubjective actions. It does not occur dyadically, from A to B, but involves a collective (Suddaby et al., Citation2017).

Studies regarding legitimacy in technology-enhanced tourism contexts are limited. Newlands and Lutz (Citation2020) examined the impact of fairness on the perceived moral legitimacy of home-sharing platforms. Platforms that were deemed fair by individuals were regarded as having more validity and required less regulation. Like traditional tourism businesses (Foley, Citation2003), peer-to-peer accommodation listings were deemed more legitimate when associated with individuals in certain positions and from hegemonic backgrounds (Shepherd & Matherly, Citation2020). Tourists can also assess the validity of peer-to-peer accommodation by comparing them with traditional lodgings (Buhalis et al., Citation2020). In these cases, legitimacy is still linked to institutional logics as businesses operate based on set criteria within varying social contexts (Ackermann et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, there are other legitimation mechanisms that can emerge online at the individual and network level through collective discussions, confrontations and interpretations within networks (Fisher et al., Citation2017; Hargrave & Van de Ven, Citation2017; Thomas & Ritala, Citation2022). In networked platforms, consumers do not have to conform to institutional logics (Hakala et al., Citation2017) and networks have increased micro-level dynamics and discursive struggles (Vaara & Tienari, Citation2008). Users rely on actions and the production of texts (Phillips et al., Citation2004). Instead of being a top-down approach as is the norm in tourism studies, legitimacy should instead be framed as a bottom-up approach that reside at the micro level within online contexts (Wong et al., Citation2019). This can be achieved through discursive legitimacy.

Discursive legitimacy: legitimacy strategies online

Discursive legitimacy implies establishing legitimacy through discourse. Dryzek (Citation2001, p. 660) defines discursive legitimacy as ‘being achieved when a collective decision is consistent with constellation of discourses present in the public sphere (online community), in the degree to which this constellation is subject to the reflective control of competent actors’. These strategies are in keeping with reconceptualising legitimacy as a process (Suddaby et al., Citation2017). Business and management scholars have examined discursive legitimacy in online environments. It is mainly explored within the context of social media platforms, such as YouTube (Veil et al., Citation2012), Twitter (Etter et al., Citation2018) and Facebook (Glozer et al., Citation2019). Studies mainly concentrate on organisational contexts.

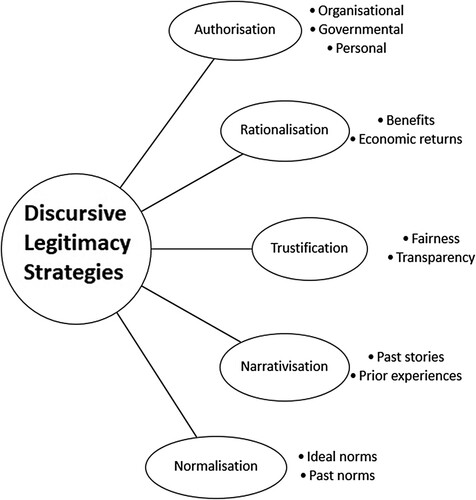

Scholars have drawn on Van Leeuwen and Wodak’s (Citation1999) well-cited discursive legitimation strategies. Strategies include authorisation, moralisation, normalisation and rationalisation. Authorisation refers to the exercise of authority by a user. This authority can be personal, expert, role model, impersonal or the authority of tradition. Moralisation occurs when a reference is made to moral values and social acceptance in order to maintain a suitable profile. Rationalisation is based on references to the usefulness of a product or practice. Individuals associate with the notion of purpose in their discourses. There is also normalisation, which is an individual referring to how things ought to be. Vaara et al. (Citation2006) further improved on these strategies by including narrativisation, which is validating an act through storytelling. Korkeamaki and Kohtamaki (Citation2020) proposed the strategy of trustification, as a strategy that focuses on drawing on narratives based on benevolence, fairness and honesty. These strategies, presented in , can legitimate or delegitimate individuals or activities (Hakala et al., Citation2017; Vaara & Tienari, Citation2008; Vestergaard & Uldam, Citation2022). They emerge within environments of extensive discussions where it can be challenged and must be maintained through ongoing deliberations. Sometimes, justification regarding an argument is needed, which calls for individuals to draw on discursive resources (Van der Steen et al., Citation2022). This is contrary to traditional forms of legitimation, which are unquestionable (Steffek, Citation2009).

Methodology

To investigate discursive legitimacy and strategies online, this research context investigates Nina Island South Inmates WhatsApp group as the online travel community. The group was formed as a traveller-to-traveller (T2T) community by travellers at the Nina Island South Hotel, which is located in the southern district of Hong Kong Island in Hong Kong. Travellers stayed at the property to fulfil the Hong Kong COVID quarantine travel requirements, that were enforced during the period of March 2020 to September 2022. The group was created six months after the property was established as a quarantine hotel and lasted until the end of quarantine requirement. While the online travel community originally emerged as a private group, overtime the community expanded to support travellers to Hong Kong before they arrived and during their stay. The T2T online community exchanged advise and tips to deal with the travel disruptions and entry requirement complications that emerged throughout the COVID period (Assiouras et al., Citation2023; Liu et al., Citation2021). The T2T community also interpreted difficult and constantly changing travel requirements and proved resourceful for traveller resilience. The group evolved overtime during COVID-19 to post COVID recovery period (Johnson & Buhalis, Citation2023). Members of the community often became close friends and co-created other online C2C communities to enable travellers to remain in contact and socialise. Communities, such as the Nina Murder Survivors and Mystery WhatsApp groups, emerged from the original Nina Island South Inmates WhatsApp communities and provided the opportunity for travellers to meet and socialise after they were released.

The research applied netnography as it is a means of examining interactions occurring via online platforms (Kozinets, Citation2010). It entails data collection, analysis and ethical research practices (Kozinets et al., Citation2010). The data for this research was gathered from the WhatsApp group, which had more than 100 members. It was a participant-driven online community established during the COVID-19 pandemic for travellers in quarantine. The period of the pandemic was considered appropriate as it was a time in which there was great concern for (il)legitimacy (Suddaby et al., Citation2017). At a gathering in Munich in 2020, the World Health Organisation Director-General told a group of foreign policy and security representative that ‘we are not just battling the virus, we are also fighting an infodemic’ (WHO, Citation2021, n.p.).

The data were collected for one month in September 2021 and yielding a total of 21,719 posts. The researchers were observers and active members of the selected online community. They engaged with the community members by posting and responding to questions and reading posts, comments and replies. This position allowed the researchers to have an in-depth understand of what individuals said and what they meant. They were also able to follow the discussions to locate legitimacy strategies. This meant identifying questions asked and locating the responses to and by members. The researchers downloaded chats from the WhatsApp platform. Password-protected folders were created to store data on a computer belonging to one of the researchers. Approval for data collection was received from the University’s human research ethics committee and members of the group. Steps were taken to ensure the anonymity of members of the community.

Thematic data analysis, as proposed by previous studies on discursive legitimation strategies (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Glozer et al., Citation2019; Korkeamaki & Kohtamaki, Citation2020) was applied. This is consistent with Kozinets and Jenkins (Citation2021) recommendation of using a data condensation process for analysing online data (Luyckx & Janssens, Citation2016; Vestergaard & Uldam, Citation2022). Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) steps were used: data familiarisation, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and generating a report. In regards to data familiarisation, notes were made as to the type of legitimation strategy that took place in real-time. Once the data was compiled and downloaded, it was read by the researchers to get a better understanding of how the legitimation strategies emerged. They noted where co-created activities were referred to, points of contestations arose, questions for further justification were made and responses that drew on various legitimation strategies. Then, initial codes were generated by reviewing each post to understand the occurrence such as time of questioning, contestation or response. The data was further sorted for generating initial codes by being placed into similar groups such as co-created experiences, communication with, communication to, emojis, posting, responses to user narratives, queries, utterances, and legitimation strategies.

The researchers continued analysis by searching for themes. Following Vestergaard and Uldam (Citation2022), the categories that guided the analysis were mainly developed based on Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2007) strategies and updated literature. This led to a framework of discursive legitimation strategies: authorisation, moralisation, normalisation, rationalisation, narrativisation, trustification and cognitive. The researchers allowed new themes to emerge as they manually coded the data. This gave rise to overarching themes. Strategies were also linked to various practices, as seen in previous business research, such as Vaara et al. (Citation2006) and Hakala et al. (Citation2017). In this research, there were strategies that associated with different types of online community co-creation practices. The researchers thematically analysed the data set in order to identify the online travel community’s practices while being guided by previous literature on such practices (Chung & Buhalis, Citation2008). The analysis was checked for similarities, differences and findings in relation to the research question. This led to the elimination of themes and sub-themes such as mythic, technological and impersonal authorisation, moralisation and cognitive strategies as these were either not present, duplicated themes or not pertaining to conversations where legitimacy was being highlighted. In terms of identifying discursive legitimacy, it is active in comparison to legitimacy from an institutional perspective. Phillips et al. (Citation2004) explained that it is tied to multiple individuals, ongoing deep engagement (contestation) that incorporates a range of discursive strategies and draws on multiple text formats. Strategies that are most received or of highest influence are based on communication genre or embedded in well-established discourses.

The themes were defined and named to ensure that they were related but separate. Sub-themes were produced (see ). The analysis process was ongoing so themes were evolved leading to the categorisation based on purpose of legitimation strategy, discursive and sub-discursive legitimation strategies, associated technology affordances, co-created practices-detached level, and co-created practices-communitas level. A research report (findings and analysis) was generated. For online communities, data may be triangulated using interviews or in-person data collection methods (Kozinets, Citation2010). However, due to lack of access and travel restrictions, investigator triangulation was done, whereas the researchers compared and settled on final themes. Examples of narratives are presented in the findings.

Table 2. Themes for discursive legitimation strategies.

Findings and discussion

This section draws attention to the five discursive strategies that emerged from the analysis, namely: authorisation, rationalisation, trustification, narrativisation and normalisation. While there are five strategies, two are noted as means for resisting and delegitimising proposed claims: authorisation and normalisation. Particularly, normalisation was evident to a lesser extent in comparison to the other strategies. It emerged as a means to resisting claims that were rationalised.

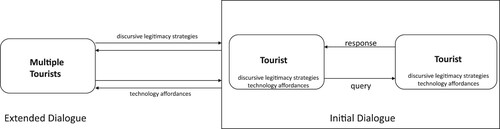

The discussion incorporates the emergent aspects that associate with each strategy. The strategies and technology affordances represent discursive resources that were used as justifications to queries and contestations regarding user-co-created practices. The analysis illustrates that co-created practices were intertwined with these discursive techniques, which resulted in an extended dialogue (see ). In this study, the practices are associated with customer-to-customer co-creation at the detached and communitas levels. Legitimation was evident to a lesser extent in relation to queries pertaining to group-related activities.

Authorisation

Authorisation refers to legitimation based on authority (Van Leeuwen, Citation2007). Feedback to user queries were accompanied by justifications based on various types of authorities. Discursive strategies were found in the form of personal authorisation, organisation authorisation and government authorisation. These authorities added credibility to user statements, as they served as a means of validating a proposed act. Co-created practices were noted at the detached level as well as the communitas level. Tourists can occupy collaborative environments but seek to detach themselves from other individuals at particular times following the co-created practice (Rihova et al., Citation2015). The practices found in this online community included information gathering for consumption experiences, optimising contextual experiences and implementing quarantine practices. Each practice was associated with various types of authorisation.

Practices that users had less control of, such as quarantine requirements, were often justified by referencing figures of authority. The members of the group asked numerous questions related to the quarantine experience, as some aspects required them to carry out procedures solo or in tandem with government representatives. In this case, legitimacy was being contested by multiple individuals with co-creation not being limited to solely a sender and receiver. In response to legitimacy threats, individual narratives incorporated external uniform resource locators (URLs), which were technology affordances that enhanced the soundness of the claim. This was a sign of legitimacy being sought through a variety of symbolic forms of communication. Indeed, not all links were seen as valid, as shown by this response regarding a service provider: ‘when I click on a (the) hyperlink of an item it takes me to the read me page’. The practice of incorporating links to well-cited external media sources enhanced some narratives, as they served as tools of legitimacy:

This article contains one interview with a named government official. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3145839/who-can-skip-quarantine-hong-kong-closer-look.

Practices in which users sought advice to optimise their in-house experiences were points of contestation, which saw guests employing two types of discursive practices: organisational and personal. For instance, a user requested contact details for a pharmacy to deal with a health matter they were experiencing. Members responded by sharing contact cards of possible service providers in the chat area. The user judged two suggestions as unsatisfactory, as they doubted the capabilities of the suggested businesses: ‘I need a real pharmacy’ as many Hong Kong outlets operate as retailers of health supplements or beauty products, rather than medical-based pharmacies. Here, the individual behaved in a more evaluative manner and casted their own judgment of the organisations, as seen in the case of Hakala et al. (Citation2017). This was a sign of a constructive interaction, which is often not seen in the co-creation process. Users in the online community exercised their agency by questioning some of the proposed narratives for delegitimising claims.

Individuals connected their social identities with statements such as ‘I’m a positive person’ and ‘I work for’. This added credibility to their narratives and perceptions of them being rational and trustworthy, which is also evident in research by Zhou (Citation2011) and Glozer et al. (Citation2019). These narratives illustrate how consumers can occupy multiple subject positions when compared to businesses. Their connections were expected to improve the acceptance of their feedback by others. Terms are often drawn on to resist organisational authorities, which is not usually the case within environments with collective identities, such as this online community for ‘Nina Inmates’ (Ananda & Fatanti, Citation2021). The community provided a space for users to express themselves, as there were emotions of anger and disgust among the members stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, similar to other online travel communities (Hao et al., Citation2022).

Personal authorisation arose in instances wherein users desired advice on consumption experiences. Travellers can be presented with a range of options based on recommendations from online users, resulting in information overload (Jones et al., Citation2004). Travellers gained clarity with regard to their queries in these cases, as users drew gave personal testimonies and reviews regarding service providers to justify their choice for purchasing particular products from preferred suppliers. Personal authorisation contributed to legitimation processes by establishing the credibility of the products in question. User responses were accompanied by a link for enabling immediate, direct connectivity to products: ‘For the wine or bubbles cravings I found https://winest.hk/’. Individuals posted photos of their rooms and meals to signal the validity of their claims as there was need for validating actions for users who had not arrived at the destination yet but were members of the group. Users were actively engaged in gaining legitimacy through different forms of communication (Phillips et al., Citation2004).

The discussion above highlighted co-created experiences at the detached level. Users typically engage in practices that establish a sense of belonging or we-ness, namely customer-to-customer co-created practices at the communitas level (Rihova et al., Citation2015). This online community was participant-driven; hence, individuals offered their time and expertise to shape the online environment. Many of the occurrences regarding the setup of the platform were justified based on personal authorisation. This strategy is favourable in instances where there is little accountability and responsibility:

Post #700: Can we put this link in the group description?

Post #701: I think that would be the best idea.

Rationalisation

Rationalisation refers to legitimation based on usefulness (Van Leeuwen, Citation2007). It is used as a strategy to enhance the credibility of offline and online experiences for travellers. In this study, offline experiences were found at the detached level when users posed questions regarding a variety of shopping experiences. Online experiences were created at the communitas level, which focused on users engaging in activities to develop user experiences. These co-created practices were associated with two types of rationalisation – benefits and economic returns. Online communities are known to be environments that provide a wealth of information that can aid users in creating plans that would influence their shopping (consumption) experiences. Feedback on prior experiences with fast-moving consumer products has been found useful by travellers. User reviews were further accepted by others when they were able to emphasise the unique characteristics and benefits of the product, thereby enhancing its utility: ‘Healthy Meal has less meat, more salads & less filling’, ‘pumpkins strengthen the immune system with vitamin C & E, iron & folate. The way they cooked it means the nutrients are retained’. According to Humpreys (Citation2010), these judgments based on benefits can serve to validate consumption experiences. Some individuals distanced themselves after further reflection and post experience, thereby illustrating that the legitimation process is continuous: ‘I was joking at some of the inmates saying that tonight healthy lunch box was too healthy’.

In some instances, users also provided responses to consumption queries that emphasised the capabilities of an organisation, which were also classified as benefits: ‘We used Market Place Super Market and they were super good. Their app (application) is well done’. Like Healthy Meal, the Market Place Super Market is not being assessed based on its conformity to institutional structures. Follow-up responses by members of the community included affordances, such as emojis and reply-to options, hence, users incorporated a range of communicative texts (Phillips et al., Citation2004). These forms of communication enabled users to show their appreciation to members even days after the post was made. Ongoing discussions regarding the rationales given also presented moments of reflection for some users, as there were instances in which users shifted their view from an association with personal authorisation to rationalisation strategies that emphasised the capabilities of the food provider. A collective voice is useful for enabling users to make more certain buying decisions.

Rationalisation based on benefits was also evident in community-based activities. The online community lacked structure and rules. Therefore, there was often little certainty on how to proceed with the development of user experiences. For instance, a member inquired whether they could change how data were presented in one of the group documents that housed items being shared among members of the community when inmates checked out. The rationale for the individual suggestion was based on maintaining aesthetics of the document layout:

Post #340: Can we not add room numbers please because then people will need to add confirmation numbers as well and it will get very messy. Just message each other privately.

Post #288: If they lowered the price … the problem is that they can't charge the ‘normal’ price when things become ‘normal’.

Post #290: Definitely worth the investment.

Post #295: The amount of testing and associated costs is bonkers also.

Trustification

Some users were interested in garnering deeper insights regarding the nature of the stakeholders. At this point, discursive strategies associated with trustification were most apparent. While previous studies note honesty, benevolence and competence as the dominant traits of trust in online travel communities (Casalo et al., Citation2011), two novel forms of trustification were found in this study: fairness and transparency. Fairness was also evident in the case of Korkeamaki and Kohtamaki (Citation2020).

Narratives that drew on these types of discursive legitimacies served to add credibility to stakeholders, specifically service providers, for queries related to co-creating experiences at the detached and communitas levels. For instance, travellers raised questions regarding where to shop and were responded to with recommendations of possible online suppliers. Feedback would emphasise that individuals have the opportunity to exercise agency through negotiating with service providers directly in order to receive fair considerations: ‘Just a small business with her mom, so it depends on how many you order; you can negotiate & pay her through FPS or PayMe’. When direct contact with a supplier was not possible, users shared the supplier’s website link (technology affordance) alongside background information to verify the supplier’s status. Verbal narratives can still draw on institutional legitimacy as noted in management research (Elsbach, Citation1994). However, here, the users’ verbal account (URL and perception) precede reference to the businesses’ normative procedures:

‘Hello ###name### here. Usually for wine I order there: http://www.hkwineguild.com bottle starts around 120HKD (Hong Kong Dollars) and are good. They select smaller producers to offer smaller price’.

Narrativisation

Narrativisation refers to stories that reward the individual for maintaining legitimacy in social practices (Van Leeuwen, Citation2007). This technique is common in destination marketing and is done based on creating stories that closely relates to one’s self (Miralbell et al., Citation2013). This is also the case with the members of the online travel community. Two types of narrativisation: past stories and prior experiences. These strategies were evident at the detached and communitas levels. Narrativisation was evident when individuals sought advice on quarantine experiences, as noted below. Like Vaara (Citation2014), the technique was drawn on as a means of offering a compelling story that may facilitate or hinder an action:

Post # 311: OK so we have had people high five other people on their floor as they exited and not a problem because only people's arms exited the room. I would not recommend this.

Post #312: I just wouldn't. Quarantine camp is not fun.

Post #316: Sorry to hear this. The only story I recall is about these two brothers throwing bags of chips across the hall.

Post #52: re pizza, my dad always had a story about when he was in the Canadian air force in the 1950s and they were delivering a plane they had overhauled to some NATO base in Greece or something, and they stopped in Naples. He and the other crewmen went out to eat dinner and they found a pizza place where they were tossing crusts in the air and there were wood fired ovens and jugs of wine and so forth. he loved it and then when we went back to Canada, he was trying to tell people about the pizza in Naples and they were like ‘What the hell are you talking about? That's crazy!’

Members drew on past experiences not only to influence others (Vaara et al., Citation2006) but to allow individuals to imagine how the experience was developed in order to enable an increased sense of belonging. One user shared their memories of developments that occurred during the early times of creating the online community. They told new members that developing the databases had incorporated procedures in which individuals had to note their name and the flag of their country of origin: ‘funny story – when the group was created – it was always name and flag’.

Discussion

Legitimacy is noted as being a key aspect shaping co-creation, however, it is yet to be acknowledged in tourism. Traditional approaches in tourism are centred on examining legitimacy at the macro level, such as organisations and business executives. Yet, influence at the micro level has been increasing since the development and adoption of technologies (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021). This study has drawn attention to the micro-level practices of establishing legitimacy, resulting in proposing a novel conceptualisation in tourism: discursive legitimacy (see ).

Figure 2. Discursive legitimacy for online customer to customer (C2C) online travel communities co-creation.

This research shows that legitimacy can be manifested online and specifically in online communities. Within this environment, legitimacy is not based on one’s association to an organisation or their identity. It is centred on the narratives that are expressed by members of the online community (Vaara & Tienari, Citation2008). Unlike the dominant institutional view of legitimacy, this paper shows that discursive legitimacy is a condition whereas individuals and organisations have to be involved in an ongoing process of creating and recreating legitimacy by interacting with all stakeholders and drawing on one or more discursive legitimacy strategies and resources. Five discursive strategies can be drawn on to legitimate or delegitimate proposed co-creation practices in tourism: authorisation, rationalisation, trustification, normalisation and narrativisation. Not all queries are legitimised while some warrant the use of more than one strategy. In some cases, members of the community issued responses that were deemed acceptable by drawing on technology affordances as discursive resources to further validate claims such as external content via URLs, photos and contact cards posting. Online environments are not easily accepted as environments for exchange when compared to brick-and-mortar businesses that are underpinned by historical data. Hence, there is need for legitimacy building for co-creation.

Customers are positioned as active stakeholders engaged in ongoing dialogue of evaluating value propositions. Hence, businesses should be aware of increasing social power that online customers possess. Digital marketing experts can suggest strategies to their contracted influencers or receive training on how to influence individuals online. This can improve their social and digital marketing skills and knowledge on content curation, which is vital for real-time co-creation (Buhalis & Sinarta, Citation2019). Entities mainly focus on storytelling for content curation. Based on the findings of this study, narrativisation is only one of the many strategies that is necessary for online dialogue (Miralbell et al., Citation2013). For instance, an online post telling travellers how to act during quarantine will draw on an authorisation strategy when compared to a post recommending suppliers that they can purchase from, which may necessitate drawing instead on trustification narratives. Businesses are increasingly turning to individuals to host social media takeovers, that is, transferring privileges of using online accounts to customers. Based on this, it is useful for users to be familiar with some of the strategies they can employ for addressing issues in real-time and building useful online communities.

Travellers’ co-created experiences are ongoing and cyclical and legitimacy is seen as a fluid, interactive process. Narratives related to communitas C2C co-created practices encountered less deliberations in comparison to those at the detached level. Individuals exercise greater care when taking suggestions regarding their detached practices in comparison to those at the communitas level. This can result in individual resistance to even organisational and government authorities. While value is perceived to be subjective in this regard, it is influenced by the legitimation process exercised collectively (Hakala et al., Citation2017). Individuals’ realities are determined based on the information that is readily available within the group. Customers' actions are determined by and restricted to the claims made by users. Legitimation forms part of the social system that influences the value co-creation process (Edvardsson et al., Citation2011).

Conclusion

This research explores how users gained legitimacy online in tourism based on discursive legitimacy. Findings reveal the five discursive legitimation strategies used to legitimate or delegitimate proposed co-creation practices in tourism, namely: authorisation, rationalisation, trustification, normalisation and narrativisation. The results provide an understanding of how the members of an online community influence others. The findings illustrate the discursive legitimation strategies employed by customers in response to two co-created practices (detached and communitas). In cases where individuals employed more than one strategy, users drew on affordances to support narratives. The study unravelled the core aspects of the discursive legitimation process, namely technology affordances, online community co-created practices and legitimation strategies.

The research has several theoretical implications and contributes to the literature in multiple ways. The study introduced and illustrated legitimacy from a discursive perspective. It examined how discursive legitimacy can emerge in technology and tourism contexts. Previous studies have also mainly focused on exploring moral legitimacy within the sharing economy. The above mentioned five types of discursive legitimation strategies excluding moralisation differ from the functionalist and institutional approaches taken to explore legitimacy in tourism settings (Suchman, Citation1995). This study illustrates those affordances alongside the strategies as core components in the dialogic aspects for co-creation. Previous research view legitimacy as an organisational, top-down approach but this study highlights that it is dependent on multiple individuals who are a part of a collective group. It is also an actively engaging approach as it arises in times of contestations and reliant on verbal explanations. During these interactions, individuals may contribute to the social construction of organisational legitimacy or the acceptance of an individual.

The research illustrated the importance of legitimacy for co-creating experiences in online travel communities. Previous studies on value co-creation in tourism and further afield have acknowledged value co-creation as being shaped by social structures. However, legitimacy has not been focused on in tourism. This study showed that legitimacy is associated with co-creation. Co-creation helps to overcome (il)legitimacy concerns as online users engage to legitimise propositions, hinder actions and provide resources while having a collective identity that is favourable. Detached and communitas co-created practices are tied to these discursive strategies. While previous studies on management have researched the discursive legitimacy strategies employed online mainly by organisations, this study illustrated those adopted by customers. The research provides also novel insights for business and management scholars through improving Van Van Leeuwen and Wodak’s (Citation1999) widely cited typologies by removing moralisation, introducing trustification as a strategy, co-created tourism experiences, technology affordances and resistance techniques during dialogue. The research emphasised that an online community is not only a space for sharing information but also an environment for legitimising stakeholders, products and practices.

The research also provides practical implications for practitioners and travellers. The study illustrates how travellers and influencers can engage more actively with users online in light of challenges, such as misinfodemics. Trust concerns regarding the identification of legitimate online users as fake user profiles and robots have proliferated (Suchacka & Iwanski, Citation2020). Findings provide consumers with information on the various strategies and affordances used for constructive human interactions online. Hospitality and tourism executives should be aware of the strategies that can be employed to strengthen their legitimacy, when acting as moderators or outsourcing online communities to individuals. Practitioners such as marketing executives, who struggle to remain in control in a digitised world, can craft communication strategies that are geared towards these users. Representatives can also take part in online communities and draw on discursive legitimation strategies to convince users to take actions that can enhance their travel experiences. Technology designers can consider the key aspects of the dialogic process to improve the layout and features of online communities. Gargaglia (Citation2022) noted that ‘online communities are the future’. Therefore, businesses are urged to take advantage of them in the post-pandemic era. They should create platforms for target marketing or engaging in partnerships. Destination management organisations can share information on destination websites of how travellers can use online travel communities more securely.

The research inevitably has a few limitations. While the research concentrated on discursive legitimacy at the micro level, it did not consider the social and institutional elements that guide users’ narratives. It examined a specific online community within a set time period. Consideration can be given for exploring how fake news on social media is established in the tourism context. The research was based on a single case study. Hence, the findings are only generalisable to similar contexts. Discursive legitimacy also overlooks the view that legitimacy can be based on the perceptions of individuals. Hence, future research can draw on the latter view for further exploration.

Nonetheless, this research can serve as a starting point for understanding discursive legitimacy in virtual environments. Based on the link between discursive strategies and co-creation, scholars can further distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate in other technology-based contexts and operationalise the concept of dialogue, as it is a core antecedent of co-creation. Future studies can conceptualise dialogic interactions within co-created contexts. Research can examine how organisations and micro-entrepreneurs, such as sharing economy service providers, draw on these strategies to promote products online as well as increase support for stakeholders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abbie-Gayle Johnson

Abbie-Gayle Johnson is an Assistant Professor at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests are in eTourism, smart tourism and the sharing economy.

Dimitrios Buhalis

Dimitrios Buhalis is a Professor of eTourism at Bournemouth University and a Strategic Management and Marketing expert. Dimitrios current research focus includes: real time and nowness, smart tourism and smart hospitality, social media context and mobile marketing (SoCoMo), technology enhanced experience management and personalisation, reputation and social media strategies.

References

- Ackermann, C., Matson-Barkat, S., & Truong, Y. (2021). A legitimacy perspective on sharing economy consumption in the accommodation section. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(12), 1947–1967. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1935789

- Adongo, R., & Kim, S. (2018). Whose festival is it anyway? Analysis of festival stakeholder power, legitimacy, urgency, and the sustainability of local festivals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(11), 1863–1889. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1514042

- Ananda, K., & Fatanti, M. (2021). Digital activism through online petition: A challenge for digital sphere in Indonesia. Development, Social Change and Environmental Sustainability, 136–140. doi:10.1201/9781003178163-30

- Antretter, T., Blohm, I., Grichnik, D., & Wincent, J. (2019). Predicting new venture survival: A Twitter-based machine learning approach to measuring online legitimacy. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 11(June 2019), e00109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2018.e00109

- Arıca, R., Kodas, B., Cobanoglu, C., Parvez, M. O., Ongsakul, V., & Della Corte, V. (2023). The role of trust in tourists’ motivation to participate in co-creation. Tourism Review, 78(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2021-0399

- Arnould, E., & Dion, D. (2022). Brand dynasty: Managing charismatic legitimacy over time. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(3-4), 338–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2022.2120059

- Ashforth, B., & Gibbs, B. (1990). The double-edge of organizational legitimation. Organization Science, 1(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.2.177

- Assiouras, I., Vallström, N., Skourtis, G., & Buhalis, D. (2022). Value propositions during service mega-disruptions: Exploring value co-creation and value co-destruction in service recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 97, 103501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103501

- Barros, M. (2014). Tools of legitimacy: The case of the Petrobras corporate blog. Organization Studies, 35(8), 1211–1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614530914

- Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks. De Gruyter.

- Bertolini, O., Moniticelli, J., Garrido, I., Verschoore, J., & Henz, M. (2021). Achieving legitimacy of a film-tourism strategy through joint private-public policymaking. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(2), 424–443. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2021-0066

- Blanco-González, A., Prado-Román, C., Díez-Martín, F., & Miotto, G. (2021). Progress in ethical practices of businesses. Progress in Ethical Practices of Businesses, 3, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60727-2_11

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buhalis, D. (2020). Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2019-0258

- Buhalis, D., Andreu, L., & Gnoth, J. (2020). The dark side of the sharing economy: Balancing value co-creation and value co-destruction. Psychology & Marketing, 37(5), 689–704. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21344

- Buhalis, D., & Foerste, M. (2015). SoCoMo marketing for travel and tourism: Empowering co-creation of value. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(3), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.001

- Buhalis, D., & Sinarta, Y. (2019). Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 563–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1592059

- Casalo, L., Flavian, C., & Guinaliu, M. (2011). Understanding the intention to follow the advice obtained in an online travel community. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 622–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.013

- Castello, I., Etter, M., & Nielsen, F. (2016). Strategies of legitimacy through social media: The networked strategy. Journal of Management Studies, 53(3), 402–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12145

- Centeno, D., & Wang, J. (2017). Celebrities as human brands: An inquiry on stakeholder-actor co-creation of brand identities. Journal of Business Research, 74, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.024

- Chung, J., & Buhalis, D. (2008). Information needs in online social networks. Information Technology & Tourism, 10(4), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.3727/109830508788403123

- CTVnews. (2022). CTVnews. Retrieved 1 October 2022, from https://www.ctvnews.ca/.

- Davis. (2019). Forbes. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescontentmarketing/2019/04/22/how-to-win-followers-and-influence-people-on-social-media/?sh=14f44683dfbd.

- Dawson, V., & Bencherki, N. (2021). Federal employees or rogue rangers: Sharing and resisting organizational authority through Twitter communication practices. Human Relations, 75(11), 2091–2121. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211032944

- Dryzek, J. (2001). Legitimacy and economy in deliberative democracy. Political Theory, 29(5), 651–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591701029005003

- Edvardsson, B., Tronvoll, B., & Gruber. (2011). Expanding understanding of service exchange and value co-creation: A social construction approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(2), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0200-y

- Elsbach, K. (1994). Managing organizational legitimacy in the California Cattle Industry: The construction and effectiveness of verbal accounts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(1), 57–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393494

- Eriksen, E. (2005). An emerging European public sphere. European Journal of Social Theory, 8(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431005054798

- Erkama, N., & Vaara, E. (2010). Struggles over legitimacy in global organizational restructuring: A rhetorical perspective on legitimation strategies and dynamics in a shutdown case. Organization Studies, 31(7), 813–839. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609346924

- Etter, M., Colleoni, E., Illia, L., Meggiorin, K., & D-Eugenio, A. (2018). Measuring organizational legitimacy in social media: Assessing citizens’ judgments with sentiment analysis. Business & Society, 57(1), 60–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316683926

- Farrelly, F. (2022). Exploring the cultural legitimacy of backpacker ideology and identity. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2485

- Fisher, G., Kuratko, D., Bloodgood, J., & Hornsby, J. (2017). Legitimate to whom? The challenge of audience diversity and new venture legitimacy. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 52-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.005

- Foley, D. (2003). An examination of indigenous Australian entrepreneurs. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 133–151.

- Giddens, A. (1984). Elements of the Theory of Structuration, Routledge.

- Gargaglia. (2022). MarketingTech. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://marketingtechnews.net/news/2022/feb/09/creating-engaging-online-communities-the-key-to-post-pandemic-brand-success/.

- Ge, J., & Gretzel, U. (2018). A taxonomy of value co-creation on Weibo – A communication perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(4), 2075–2092. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0557

- Glozer, S., Caruana, R., & Hibbert, S. (2019). The never-ending story: Discursive legitimation in social media dialogue. Organization Studies, 40(5), 625–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617751006

- Grace, D., & Iacono, J. (2015). Value creation: An internal customers’ perspective. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(6/7), 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-09-2014-0311

- Gustafson, B., & Pomirleanu, N. (2021). A discursive framework of B2B brand legitimacy. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.12.009

- Hakala, H., Niemi, L., & Kohtamaki, M. (2017). Online brand community practices and the construction of brand legitimacy. Marketing Theory, 17(4), 537–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593117705695

- Hao, F., Park, E., & Chon, K. (2022). Social media and disaster risk reduction and management: How have Reddit travel communities experienced the COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, XX(X), 1–26.

- Hargrave, T., & Van de Ven, A. (2017). Integrating dialectical and paradox perspectives on managing contradictions in organisations. Organization Studies, 38(2-4), 319-339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616640843

- Herrmann-Pillath, C. (2020). The art of co-creation: An intervention in the philosophy of ecological economics. Ecological Economics, 169, 106526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106526

- Humpreys, A. (2010). Semiotic structure and the legitimation of consumption practices: The case of casino gambling. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(3), 490–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/652464

- Illia, L., Colleoni, E., Etter, M., & Meggiorin, K. (2023). Finding the tipping point: When heterogeneous evaluations in social media converge and influence organizational legitimacy. Business & Society, 62(1), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503211073516

- Jamal, T., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

- Johnson, A., & Buhalis, D. (2022). Solidarity during times of crisis through co-creation. Annals of Tourism Research, 97(November), 103503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103503

- Jones, Q., Ravid, G., & Rafaeli, S. (2004). Information overload and the message dynamics of online interaction spaces: A theoretical model and empirical exploration. Information Systems Research, 15(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1040.0023

- Karlsson, J., & Skalen, P. (2022). Learning resource integration by engaging in value cocreation practices: A study of music actors. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 32(7), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-09-2021-0193

- Kavoura, A., & Buhalis, D. (2022). Online communities. In D. Buhalis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of tourism management and marketing. Edward Elgar.

- Kelleher, S. (2021). Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/suzannerowankelleher/2021/10/27/tripadvisor-reviews-china-virus-wuhan-virus-covid-slurs/?sh=38aec87315e8, January 30, 2023.

- Kim, S., Park, M., & Rho, J. (2015). Effect of the government’s use of social media on the reliability of the government: Focus on Twitter. Public Management Review, 17(3), 328–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.822530

- Korkeamaki, L., & Kohtamaki, M. (2020). To outcomes and beyond: Discursively managing legitimacy struggles in outcome business models. Industrial Marketing Management, 91(November), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.08.023

- Kozinets, R. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage.

- Kozinets, R., De Valck, K., Wojnicki, A., & Wilner, S. (2010). Networked narratives: Understanding word-of-mouth marketing in online communities. Journal of Marketing, 74(2), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.74.2.71

- Kozinets, R., & Jenkins, H. (2022). Consumer movements, brand activism, and the participatory politics of media: A conversation. Journal of Consumer Culture, 22(1), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/14695405211013993

- Leal, M. M., Casais, B., & Proença, J. F. (2022). Tourism co-creation in place branding: The role of local community. Tourism Review, 77(5), 1322–1332. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-12-2021-0542

- Lee, H., Law, R., & Murphy, J. (2011). Helpful reviewers in TripAdvisor, an online travel community. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(7), 675–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.611739

- Lei, S. I., Wang, D., & Law, R. (2022). Mobile-based value co-creation: Contextual factors towards customer experiences. Tourism Review, 77(4), 1153–1165. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-10-2020-0504

- Lei, S., Wang, D., & Law, R. (2019). Hoteliers’ service design for mobile-based value co-creation. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(11), 4338–4356. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2018-0249

- Leung, D., Law, R., Van Hoof, H., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1-2), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.750919

- Liu, C.-H., Lee, W.-L., Fang, Y.-P., & Zhang, Y. (2022). The effect of COVID-19 perceptions on tourists’ attitudes, safety perceptions and destination images: Moderating role of information sharing. Tourism Review, 77(5), 1249–1261. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2021-0422

- Liu, X., Fu, X., Hua, C., & Li, Z. (2021). Crisis information, communication strategies and customer complaint behaviours: The case of COVID-19. Tourism Review, 76(4), 962–983. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-01-2021-0004

- Luyckx, J., & Janssens, M. (2016). Discursive legitimation of a contested actor over time: The multinational corporation as a historical case (1964–2012). Organization Studies, 37(111), 1595–1619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616655493

- Massi, M., Rod, M., & Corsaro, D. (2021). Is co-created value the only legitimate value? An institutional-theory perspective on business interaction in B2B-marketing systems. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 36((2)/2), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-01-2020-0029

- Melis, G., McCabe, S., Atzeni, M., & Del Chiappa, G. (2022). Collaboration and learning processes in value co-creation: A destination perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 1–18.

- Mendoza, M., Alfonso, M., & Lhuillery, S. (2021). A battle of drones: Utilizing legitimacy strategies for the transfer and diffusion of dual-use technologies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120539

- Middleton, K., Thompson-Whiteside, H., Turnbull, S., & Fletcher-Brown, J. (2022). How consumers subvert advertising through rhetorical institutional work. Psychology & Marketing, 39(3), 634–646. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21612

- Miralbell, O., Alzua-Sorzabal, A., & Gerrikagoitia, J. K. (2013). Content curation and narrative tourism marketing. In Z. Xiang, & I. Tussyadiah (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014. Springer International Publishing.

- Mohammadi, F., Yazdani, H. R., Jami Pour, M., & Soltani, M. (2021). Co-creation in tourism: A systematic mapping study. Tourism Review, 76(2), 305–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-10-2019-0425

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2014). A typology of technology-enhanced tourism experiences. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(4), 340–350. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1958

- Newlands, G., & Lutz, C. (2020). Fairness, legitimacy and the regulation of home-sharing platforms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(10), 3177–3197. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2019-0733

- Oliveira, T., Araujo, B., & Tam, C. (2020). Why do people share their travel experiences on social media? Tourism Management, 78, 104041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104041

- Pappas, N. (2016). Marketing strategies, perceived risks, and consumer trust in online buying behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29(March 2016), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.11.007

- Parsons, T. (1960). Structure and process in modern societies. Free Press.

- Peterkin, K., Badu-Baiden, F., & Alhuqbani, F. M. (2022). Stress and coping: Exploring the experiences of travellers during COVID-19 hotel quarantine. Tourism Recreation Research, ahead-of-print, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2114747

- Pfeffer, J., & Salanick, G. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Harper & Row.

- Phillips, N. (1997). Managing legitimacy in ecotourism. Tourism Management, 18(5), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00020-4

- Phillips, N., Lawrence, T., & Hardy, C. (2004). Discourse and institutions. The Academy of Management Review, 29(4), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159075

- Powell, W., & DiMaggio, P. (2012). The new institutionalism in organisational analysis. University of Chicago Press.

- Prahalad, C., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

- Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Addison-Wesley.

- Richter, L. (1980). The political uses of tourism: A Philippine case study. The Journal of Developing Areas, 14(2), 237–257.

- Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Moital, M., & Gouthro, M. (2013). Social layers of customer-to-customer value co-creation. Journal of Service Management, 24(5), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-04-2013-0092

- Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Moital, M., & Gouthro, M. (2015). Conceptualising customer-to-customer value co-creation in tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(4), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1993

- Roiseland, A. (2022). Co-creating democratic legitimacy: Potentials and pitfalls. Administration & Society, 54(8), 1493–1515. https://doi.org/10.1177/00953997211061740

- SCMP. (2021). SCMP. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3150110/hong-kong-quarantine-hotel-residents-wave-outside, April 1, 2022.

- Shen, H., Wu, L., Yi, S., & Xue, L. (2020). The effect of online interaction and trust on consumers’ value co-creation behavior in the online travel community. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(4), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1553749

- Shepherd, S., & Matherly, T. (2021). Racialization of peer-to-peer transactions: Inequality and barriers to legitimacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 55(2), 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12337

- Snihur, Y., Thomas, L. D. W., & Burgelman, R. A. (2018). An ecosystem-level process model of business model disruption: The disruptor’s gambit. Journal of Management Studies, 55(7), 1278–1316. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12343

- Steffek, J. (2009). Discursive legitimation in environmental governance. Forest Policy and Economics, 11(5-6), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2009.04.003

- Suchacka, G., & Iwanski, J. (2020). Identifying legitimate Web users and bots with different traffic profiles — An Information Bottleneck approach. Knowledge-Based Systems, 197, 105875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2020.105875

- Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Suddaby, R., Bitektine, A., & Haack, P. (2017). Legitimacy. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 451–478. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0101

- Talwar, S., Dhir, A., Singh, D., Virk, G., & Salo, J. (2020). Sharing of fake news on social media: Application of the honeycomb framework and the third-person effect hypothesis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102197

- TheGovLab. (2021). The Gov Lab. Retrieved 1 April 2022, from https://virtual-communities.thegovlab.org/.

- Thomas, L., & Ritala, P. (2022). Ecosystem legitimacy emergence: A collective action view. Journal of Management, 48(3), 515–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320986617

- Traveloffpath. (2022). Travelofpath. Retrieved 1 October 2022, from https://www.traveloffpath.com/.

- TripAdvisor. (2022). TripAdvisor. Retrieved 1 October 2022, from https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/TransparencyReport2021.

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation. (2022). UNWTO. Retrieved 1 October 2022, from https://www.unwto.org/.

- Vaara, E. (2014). Struggles over legitimacy in the Eurozone crisis: Discursive legitimation strategies and their ideological underpinnings. Discourse & Society, 25(4), 500–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926514536962

- Vaara, E., & Monin, P. (2010). A recursive perspective on discursive legitimation and organizational action in mergers and acquisitions. Organization Science, 21(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0394

- Vaara, E., & Tienari, J. (2008). A discursive perspective on legitimation strategies in multinational corporations. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.34422019

- Vaara, E., Tienari, J., & Laurilla, J. (2006). Pulp and paper fiction: On the discursive legitimation of global industrial restructuring. Organization Studies, 27(6), 789–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606061071

- Van der Steen, M., Quinn, M., & Moreno, A. (2022). Discursive strategies for internal legitimacy: narrating the alternative organizational form. Long Range Planning, 55(5), 102162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2021.102162

- Van Herck, R., Decock, S., & De Clerck, B. (2020). “Can you send US a PM please?” Service recovery interactions on social media from the perspective of organizational legitimacy. Discourse, Context & Media, 38, 100445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2020.100445

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2007). Legitimation in discourse and communication. Discourse & Communication, 1(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481307071986

- Van Leeuwen, T., & Wodak, R. (1999). Legitimizing immigration control: A discourse-historical analysis. Discourse Studies, 1(1), 83–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445699001001005

- Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. (2016). Institutions and axioms: an extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44, 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3

- Vargo, S., Maglio, P., & Akaka, M. (2008). On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. European Management Journal, 26(3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2008.04.003

- Veil, S., Sellnow, T., & Petrun, E. (2012). Hoaxes and the paradoxical challenges of restoring legitimacy. Management Communication Quarterly, 26(2), 322–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318911426685

- Vestergaard, A., & Uldam, J. (2022). Legitimacy and cosmopolitanism: Online public debates on (corporate) responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 176(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04703-1

- Wang, C., Hu, H., & Lie, G. (2018). The corporate philanthropy and legitimacy strategy of tourism firms: A community perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1124–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1428334

- WHO. (2021). World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic#tab=tab_1

- Williams, N. L., Inversini, A., Buhalis, D., & Ferdinand, N. (2015). Community crosstalk: An exploratory analysis of destination and festival eWOM on Twitter. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(9-10), 1113–1140. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1035308

- Williams, N. L., Inversini, A., Ferdinand, N., & Buhalis, D. (2017). Destination eWOM: A macro and meso network approach? Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.02.007

- Wong, I., Luo, J., & Fong, V. (2019). Legitimacy of gaming development through framing: An insider perspective. Tourism Management, 74, 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.005

- Wood, D., & Gray, B. (1991). Toward a comprehensive theory of collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(2), 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886391272001

- Xu, Y., Zhang, Z., Law, R., & Zhang, Z. (2020). Effects of online reviews and managerial responses from a review manipulation perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(17), 2207–2222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1626814

- Yates, J., & Orlikowski, W. (2002). Genre systems: structuring interaction through communicative norms. The Journal of Business Communication, 39(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194360203900102

- Yu, C., Tsai, C., Wang, Y., Lai, K., & Tajvidi, M. (2020). Towards building a value co-creation circle in social commerce. Computers in Human Behavior, 108, 105476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.021