ABSTRACT

The tourism sector has a role in environmental stewardship, including the responsible representation of tourism destinations. However, tourism stakeholders may, willingly or unwittingly, through uninformed or irresponsible promotion, support the perpetuation of environmental problems. We explore how tourism stakeholders portray a serious environmental problem in New Zealand – invasive species – using the case of Russell lupin. Lupins are an example of a ‘charismatic’ but highly invasive weed that tourism stakeholders may perceive as contributing to destination attractiveness. We document how 17 regional/national tourism organisations portray this invasive species in their Instagram accounts, employing an analysis of the imagery and accompanying commentary of 94 exhibits. We found overwhelming evidence of lupin being represented both by tourism organisations and their audiences as a highly desirable landscape feature. Where negative impacts were alluded to, these were embedded within a broader positive narrative underplaying the seriousness of the ecological threats. Uncritical acceptance and incorporation of invasive species as destination attractions may complicate future efforts for control or eradication. Tourism organisations have a role in sustainable destination management that includes the need to responsibly re-present environmental problems in their promotion activities to foster awareness and action among their audiences and visitor markets.

Introduction

Tourism researchers point out the critically important role of environmental stewardship for tourism organisations (Hudson and Miller, Citation2005, p. 133), especially in ecologically vulnerable places, and observe the role of responsible marketing to this end. Unfortunately, the tourism sector continues to be implicated in the perpetuation of unsustainable environmental practices in destinations, often through inappropriate marketing that incorporates unsustainable settings or activities as attractions in their destination promotion (Jamal & Camargo, Citation2022). Such promotional activities that condone or perpetuate irresponsible tourism practices leading to unsustainable environmental settings fail to meet contemporary expectations around sustainable tourism. Furthermore, they are a long way from what is considered to be regenerative tourism, an aspirational state for the tourism sector in which visitors would depart the destination leaving it better off than when they had arrived (Becken & Kaur, Citation2021; Pollock, Citation2020). In line with sustainable and regenerative approaches, tourism entities, and in particular public entities such as regional tourism organisations (RTOs), would ideally adopt responsible marketing practices with a view towards enlightening visitors about the unsustainable settings that they may encounter within destinations and providing opportunities for visitors to contribute to positive change.

To date the limited research on unethical or irresponsible marketing practices in tourism has focused on human rights (e.g. Jamal & Camargo, Citation2014), consumer rights (e.g. Liu & Tien, Citation2019), and greenwashing (e.g. Campelo et al., Citation2011; Smith & Font, Citation2014). The object of interest for this paper falls within the field of nature-based tourism, and we focus on how a so-called natural attraction is represented. The study examines the promotional efforts of RTOs in relation to natural settings that have been impacted by invasive alien species. Invasive alien species (IAS) are those that are found outside of their natural range, and which have spread rapidly causing significant ecological and associated impacts. Thousands of alien plants and animals are now found around the world, causing profound impacts on biodiversity, ecosystem functioning, public health, recreation, and infrastructure, and are implicated in the extinction or endangerment of hundreds of species (Milanović et al., Citation2020; Vila & Hulme, Citation2017). Invasive alien species are one of the main challenges for contemporary environmental management (Bolpagni, Citation2021), and are associated with a global annual mean cost of US$26.8 billion over the last few decades (Diagne et al., Citation2021).

IAS have been described as a ‘missing dimension’ in sustainable tourism (Hall, Citation2015, p. 81). They can impact negatively on tourism destinations by reducing naturalness, biodiversity, and ecological integrity, aspects of destinations which are often seen as important for attractiveness and competitiveness (Hakim et al., Citation2005; Hall, Citation2015; Lovelock, Citation2007a). Conversely, tourism is a significant vector for IAS movement to and within destinations (e.g. through flights, vehicular movements, footwear etc. (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2011)). But importantly, tourism can also perpetuate the presence and spread of IAS through non-tangential means, notably when invasive species are promoted as attractive ‘natural’ elements within touristic imagery. In these cases, IAS may become ingrained in tourist and community mindsets as essential elements of destination attractiveness, and their ecological and associated impacts ignored.

This paper considers one IAS, Russell lupin, which is a serious environmental weed in New Zealand, yet which also appears in the promotional activities of RTOs in an ambiguous manner. Recognising the centrality of social media in regional tourism promotion, and particularly the Instagram platform (Fatanti & Suyadnya, Citation2015; Fusté-Forné, Citation2022; Iglesias-Sánchez et al., Citation2020), we provide an analysis of how one serious IAS is portrayed by RTOs and responded to by audiences (including locals and potential visitors). We discuss the implications of such a portrayal, not only for the issue of IAS but more broadly for a range of unsustainable social and environmental practices and settings that tourism destination entities may be inadvertently or deliberately endorsing through their touristic marketing and imagery.

Literature review

Invasive alien species: an ambiguous issue

Invasive alien species (IAS) are non-native species that arrive in a new area, establish, and increase in density and distribution to the detriment of the recipient environment. In many instances invasive plants and animals eat, predate, and spread, impacting native species and landscapes. The spread and impacts of IAS are expected to grow with continued globalisation, land use modification, and climate change (Veitch & Clout, Citation2002; Bonanno, Citation2016).

Based on the proposition that they threaten ecological values, there is in general an assumption of on-going homogeneity in public support for eradication of IAS. But that view is not necessarily shared by all stakeholders. The way we view IAS is a by-product of our values (Reaser, Citation2001, p. 89), and the acceptability of IAS is associated with the values attributed to the invasive species in question (Estévez, Anderson, Pizarro & Burgman, Citation2015; Selge, Fischer & van der Wal, Citation2011; Shackleton et al., Citation2019a). A significant proportion of IAS, even some quite noxious ones (e.g. cane toad, black rat, Nile perch, kudzu grass), may benefit or please some stakeholders, and this makes their control or eradication politically and socially complicated (Robinson et al., Citation2005). IAS form the basis of many social, cultural, and economic resource use systems; people and communities can develop attachments to introduced species (e.g. as important food sources or a source of firewood and building material) – but also cultural ecosystem services related to tourism and recreation (Pejchar & Mooney, Citation2009). But in addition to having critical nutritional or economic importance, IAS may become icons of regional identity and history, and core symbols of communities (e.g. Shackleton et al., Citation2019b).

Globally there are many examples of where attempted eradication of IAS has been challenged and delayed by opposition from interested and affected communities (Bremner & Park, Citation2007). For example, in the United Kingdom, eradication of introduced monk parakeets has been resisted by local community members due to the attractiveness of the birds and the affective attachments that have developed between people and parakeets (Crowley et al., Citation2019). This example is illustrative of how opposition to control of IAS is stronger for ‘charismatic’ species (i.e. those that are aesthetically pleasing or have sentimental value). Similarly, there is less support for the removal of ‘beautiful’ invasive plants (Lindemann-Matthies, Citation2016; Veitch & Clout, Citation2001).

Adding to social and political ambiguities surrounding IAS is an emerging narrative of invasive species ‘denialism’ that challenges the native/introduced dichotomy and promotes a globalised world in which we accept and ‘learn to live’ with IAS and the novel ecosystems that arise (Russell & Blackburn, Citation2017; Wallach et al., Citation2020). Conservation biologist and former IUCN Chief Scientist Jeffrey McNeely referred to this as the ‘great reshuffling’, a process in which post-colonial ecologies become irreversibly hybridised (McNeely, Citation2001). At the radical end, we observe narratives of eco-xenophobia, in which those wishing to control invasive trees, for example, have been labelled ‘Tree Taliban’ or ‘tree racists’ (Dinat et al., Citation2019; Thomson, Citation2019). Similarly, there are arguments for retention of some IAS which may have a potential role in replacing native species that are now extinct, or that environmental change has impacted. Invasive trees, for example, may play a role in more efficiently sequestering carbon; introduced coarse fish may be able to survive in water of lower quality (Pearce, Citation2016). It is also argued that some IAS may contribute to greater system resilience (Bhagwat, Citation2018). Alongside such views, more ‘compassionate conservation’ narratives call for IAS to be reconsidered as ‘migrant’ species and advocate for their inclusion in counts of biodiversity (e.g. Wallach et al., Citation2020).

IAS and tourism

Tourism, as an economically valuable activity, significantly contributes to, and is affected by biological invasions (Hall et al., Citation2011; Hall, Citation2015; Oded & Ram, Citation2015). Tourism continues to be an agent for IAS movement to and within destinations (Anderson et al., Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2011; Hall, Citation2015; Pickering & Mount, Citation2010). Pickering and Mount’s (Citation2010) review of the role of tourism in the spread of IAS revealed a wide range of plant species including known environmental weeds spread by tourists on clothing, vehicles, and animal transport. Visitors also carry microscopic pathogens, for example, the soil-borne fungal pathogen fatal to Kauri trees in New Zealand (Ovenden, Citation2020). Hall (Citation2015) points out that the movement of IAS – or biological exchange – via tourism constitutes a ‘major threat to future food supplies and human and environmental health’ (p. 82). In this context, tourism is seen as a significant vector of environmental change.

As Oded and Ram (Citation2015) note, as well as being a vector for environmental change, tourism can also be a victim when it comes to the spread of IAS. In their study, Odel and Ram use numerous examples to illustrate how the spread of IAS in Israel has served to devalue the tourism experience. They highlight, for instance, how the Asian Tiger Mosquito and the Little Fire Ant can detract from positive nature-based tourism and recreation by preventing access to visitor sites and attractions. Similar examples abound in the literature. Nikodinoska et al. (Citation2014), for instance, discuss how the prickly Opuntia plant impedes physical access and restricts recreational activities for tourists in parts of South Africa. Invasive plants may also impact upon on a larger scale, for example wilding trees can increase landscape homogenisation, effect landscape aesthetics, and decrease overall biodiversity of destinations (Villéger & Brosse, Citation2012). Such homogenisation can also degrade the ecosystem services that support tourism activities (Hall, Citation2015; Oded & Ram, Citation2015; Kueffer & Kull, Citation2017). In addition to the actual direct impact of IAS upon visitors, it is also found that prevention and control measures targeting IAS may have a negative impact upon tourism activities. This may be through the impact of control measures upon landscapes (e.g. vegetation being sprayed with herbicide), or access being restricted to those areas that are subject to control measures (Liu & Tien, Citation2019).

However, as Kourantidou et al. (Citation2022) point out, many IAS may be perceived as ‘double-edged’, exhibiting both positive and negative impacts on society. We also observe this aspect of IAS in their interactions with tourism, with some invasive species arguably enhancing destination attractiveness. Indeed, on occasion, IAS have even been deliberately spread to enhance the attractiveness of destinations, but with subsequent negative impacts upon endangered wildlife (Lovelock et al., Citation2022). Sometimes charismatic IAS are valued because of their contribution to the touristscape, for example, the protection of invasive feral horses has gained support from tourism agencies (Beever & Brussard, Citation2000). Some attractive non-native plants, including acknowledged environmental weeds, have been found to have value as tourist resources (Onozuka & Osawa, Citation2022). Other IAS may have value associated with certain touristic activities (e.g. fish or game species, introduced for the purposes of angling or hunting) and thus having substantial economic value (Lovelock, Citation2007b; Barnes et al., Citation2014). Rainbow trout, for example, an introduced fish in South Africa, are highly valued for tourist and recreational angling there yet have substantial ecological impacts on native aquatic ecosystems (Cambray, Citation2003). The establishment of Nile perch in Lake Victoria, Africa, is a widely known case of an ecologically destructive invasive fish, yet the species plays an important role in boosting local economies, including tourism (Yongo et al., Citation2005). Some IAS may also have value associated with popular culture, for example the wild horse via its portrayal in movies as a North American icon (Sullivan, Citation2019). This may even hold true in cases where the cultural reference is more obscure and may only hold relevance to a small group of visitors from a particular background (e.g. the Monty Python Flying Circus sketch wherein the character Dennis Moore, played by John Cleese, robbed the rich of their lupins to ‘pay’ the poorFootnote1).

A number of IAS have been integrated into tourism products, for example Southern cattail, an invasive plant in Mexico, has helped indigenous peoples there to diversify their local handicraft practices and gain economic benefits from enhanced sales to tourists: ‘Vendors and locals reported that this invasive species is a central part of what supports their tourist economy’ (Andrade, Citation2019, p. 53). In other destinations IAS may feature strongly in destination imagery or form part of tourism branding (e.g. Tonellotto et al., Citation2022). This has been observed in some of New Zealand’s regional towns, for example Gore promoting itself as the ‘Brown trout capital of the world’, Waimate capitalising on its introduced wallabies, ‘Hop in for a visit’, and Twizel labelling itself the ‘Town of Trees’ – albeit the trees being primarily introduced conifers, now invasive in the region.

Thus, tourists too may see some IAS as beneficial, if not essential to their visits. Accordingly, tourists and the tourism industry are therefore stakeholders in the management of IAS, either supportive of control or eradication of IAS (e.g. Schneider & Qian, Citation2014) or opposed if this runs counter to business or destination level interests (Ansong & Pickering, Citation2015; Lovelock et al., Citation2022; Malpica-Cruz et al., Citation2017; Morgan & Simmons, Citation2014).

While there are limited studies of how tourists and the tourism industry actually engage with IAS, extant studies (e.g. Ansong & Pickering, Citation2015; Bravo-Vargas et al., Citation2019; Koichi et al., Citation2012; Lovelock, Citation2007a; Lovelock et al., Citation2022; van Wilgen, Citation2012; Zhang et al., Citation2021) reveal variation in the way that visitors assess the threat from such species. van Wilgen (Citation2012) notes that many visitors to Table Mountain National Park in South Africa see invasive trees as aesthetically attractive and associate them with ecological benefits. Koichi et al. (Citation2012) found that visitors were unaware of the presence of feral pigs and encouraged environmental education to be incorporated into rainforest ecotourism activities to increase visitor awareness of the impacts of pests on the environment. The few studies of tourism businesses reveal recognition of the IAS problem and its potential negative impact upon the sector (Tonellotto et al., Citation2022), but also highlight that some tourism sector members see the potential value of IAS. Some tourism stakeholders in Gawith et al.’s (Citation2020) study of invasive conifers in New Zealand advanced a ‘counter-narrative’ (to the dominant narrative of the need for control or eradication) that wilding conifers made the landscapes more aesthetically pleasing for tourists: ‘To remove the [invasive] trees would therefore remove what could arguably constitute what has become one of the larger cultural values of the landscape’ (Gawith et al., Citation2020, p. 3047).

These studies demonstrate that the support of the tourism sector in the management of IAS is by no means assured, especially for those IAS that may be seen to be attractive and to have ‘value’ for tourism. However, extant studies are limited and are based mainly on visitor surveys or stakeholder interviews. There is a need to further understand how the tourism sector perceives and portrays IAS, and how potential visitors (as well as locals and others) respond to such portrayals (Nikodinoska et al., Citation2014). Social media, in this case Instagram, offers a potentially useful source of data from which we can simultaneously analyse how the supply-side (in this case destination management organisations) portray IAS and how the demand side (visitors and the destination community) receive and respond to such portrayals. This research will thus be helpful for supporting IAS managers in their engagement with the tourism sector concerning IAS control and eradication programmes, and in the design of effective environmental messages aimed at tourism businesses and visitors (Lovelock et al., Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2021).

Methods

The study setting

New Zealand is an island nation where 60 million years of geological isolation from other land masses has resulted in a high degree of endemism (McNeely, Citation2001) and a unique flora and fauna. However, human settlement, initially Māori from the thirteenth century and European colonisation from the late eighteenth Century, has severely modified ecosystems across the country (Beattie, Citation2011), with much native vegetation burned and cleared during settlement. Accompanying these destructive land management practices, a wide range of invasive plant and animal species, many deliberately introduced for a variety of economic and cultural reasons during settlement and colonisation, have also profoundly affected the native biota of New Zealand, leading to large numbers of extinctions (Wilson, Citation2004).

Many areas and landscapes of New Zealand now comprise mixed biodiversity with native and introduced species (De Lange et al., Citation2009). Along with invasive predators, invasive plants are an important ecological problem throughout New Zealand, contributing to loss of indigenous biodiversity, production losses, and landscape modification, and requiring an ongoing substantial investment in control (Russell et al., Citation2015). The collective economic costs to the country of IAS in terms of loss of production and ecosystem services, along with management costs, have been estimated to be over US$120 million per annum (Bodey et al., Citation2022).

The IAS in question – Russell lupin

Notwithstanding the ecologically destructive impacts of IAS in New Zealand, tourism, as the nation’s primary export earner (until Covid-19), has traded heavily on a 100% Pure brand which brings with it expectations of an unmodified land and the promise of spectacular landscapes and engagement with a unique, native, flora and fauna (Campelo et al., Citation2011). The reality, however, is that in most tourists’ itineraries throughout New Zealand they will encounter a number of invasive species, sometimes in otherwise highly natural settings. Such is the case with the invasive plant that is the focus of this study. Russell lupin (Lupinus × russellii), is a decorative perennial garden plant that is a hybrid of a species native to North America (where lupins are also considered a pest in some locations (National Park Service, Citation2021)). This plant is present across the study area but is a particularly significant problem in Canterbury and specifically Te Manahuna Mackenzie Basin where it rapidly invades the shingle braided river systems that are characteristic of this area. There, it modifies river flows, reduces feeding habitat and nesting site availability for a number of endangered birds (e.g. black stilt/kakī, banded dotterel/tūturiwhatu, black fronted tern/tarapirohe, wrybill/ngutu pare and black-billed gull/tarāpuka), and provides cover for invasive predators (cats, mustelids, hedgehogs) (Caruso et al., Citation2013). Russell lupins are subject to control operations (e.g. spraying) in certain areas that have high ecological value, undertaken by central and regional government agencies (Schori, Gale, Hines & Nelson, Citation2021).

Large amounts of seed are spread by water, and also by humans purposefully distributing them along roadsides. Lupins have also been grown by some famers in the area as a nitrogen fixing plant and source of sheep fodder in difficult dryland soils (Scott et al., Citation2018). The plants’ current wide range across Te Manahuna originates from the 1930s when initially planted in the gardens of high-country farms. From that time, seeds were then deliberately spread along the roads of the area to ‘beautify’ the landscape (InspiredNZ.com, Citation2021; Weedbusters, Citation2021). Local legend has it that seeds were also given by tour bus drivers to their passengers to distribute during their holidays in the region. Seeds continue to be sold in nurseries and tourist shops – and have even been labelled as ‘native plants’ (Anthony, Citation2021). The outcome is that swathes of land are now covered in Russell lupins, which, when in bloom, form an attractive and highly photogenic foreground to the spectacular mountain landscapes of the region. Lupins now feature in official tourism imagery, nationally and regionally, and are prominent in visitors’ social media imagery of the region.

Analysis of Instagram representations of Russell lupin

Social media has become an indispensable tool for tourism promotion, utilised at a number of levels from individual tourist operator/attraction to national tourism organisations (Fatanti & Suyadnya, Citation2015; Fusté-Forné, Citation2022; Iglesias-Sánchez et al., Citation2020; Nautiyal et al., Citation2022). This study examines how Russell lupin are portrayed by RTOs on their Instagram accounts, and the responses to these portrayals by audiences. These audiences may include potential domestic/international visitors, but also non-visitors, for example residents within the destination, citizens from outside the destination, tourist operators, and of course, those who may have a particular interest in the IAS itself.

Instagram is a highly prominent visual social media platform (Gretzel, Citation2017; Laestadius, Citation2017; Kozinets, Citation2020) with almost 1.5 billion active users globally (Statista, Citation2022). Instagram supports the uploading of user photographs that are ‘posted’ with or without an accompanying text explanation. Other Instagram users can then ‘comment’ on the original post and/or provide a ‘like’. The original post may also provide important ‘researchable’ data, for example geolocation data, that goes beyond the core online traces (photo’s, text explanations, and comments).

For Kozinets (Citation2020),

When people post images, video, or text online, or when they comment, share, or do anything else that is accessible online … , what they leave behind are online traces’. (p. 16)

Kozinets (Citation2020) goes on to note that online traces represent a ‘free form of public social information’ (p. 16) of which, arguably, tourism promotional materials, and other touristic-related material, may be included. In this study, the ‘online traces’ being investigated are Instagram posts from RTOs and associated comments from audiences.

Together, Instagram’s rich data provides a ‘highly visual culture that frequently conveys meanings through photographs, with text … as needed for context’ (Laestadius, Citation2017, p. 575). The richness of data afforded by Instagram helps to make the platform a valuable one for conducting social research. Added to this, as Laestadius (Citation2017) explains, Instagram also affords searchability (specific topics and/or accounts can easily be found), a high degree of interpretability (because of the richness of data), and replicability (posts and associated comments can be easily screen-captured and saved, aiding data analysis). In part, the kinds of affordances outlined have ensured that Instagram – as a research site – has grown in popularity among tourism scholars, albeit there remains considerable untapped potential (see Volo and Irimiás (Citation2021) review).

Research context

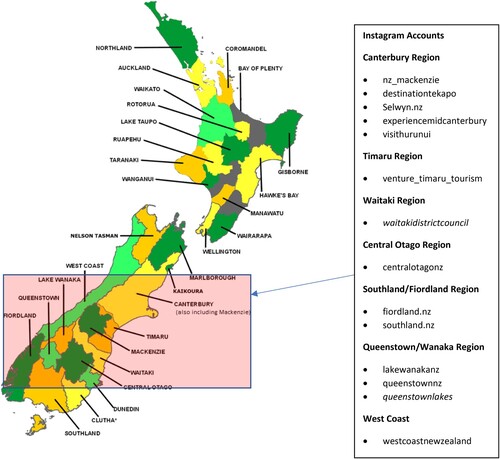

This study analyses the Instagram accounts – specifically, any online ‘traces’ (i.e. posts) to do with Russell lupin – of 14 RTOs, including two local authorities with RTO functions. The figure below () depicts the geographical area covered by the 14 RTOs.

Figure 1. Map of Regional Tourism Organisations and list of regional/local Instagram accounts analysed (map source: Regional Tourism New Zealand). (Note: italicised names represent the accounts of local authorities with RTO functions; all others are RTO accounts).

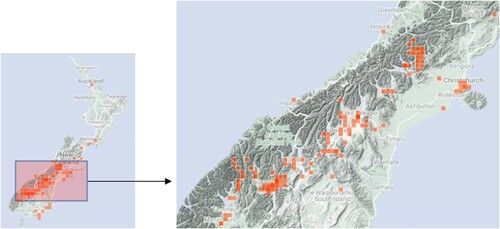

The justification for focusing on this particular area – the mid/lower South Island of New Zealand – is two-fold. Firstly, the mid/lower South Island contains the largest distribution of wild Russell lupin in New Zealand (see ). Secondly, the area is home to many key tourism destinations (e.g. Lake Tekapo/Takapō, Aoraki Mount Cook) where, based on our wider study, Russell lupin are known to be simultaneously popular with visitors and locals but at the same time highly problematic from an ecological perspective (e.g. due to an abundance of braided rivers inhabited by endangered native species).

Figure 2. Distribution of wild Russell lupin in New Zealand and the lower South Island (source: inaturalist.org).

Tourism New Zealand (the national tourism organisation), the Department of Conservation (the country’s national conservation agency), and Air New Zealand (the national carrier) are all national organisations with a key stake in New Zealand tourism promotion and/or conservation and, as such, these three accounts were also analysed in order to further understand how Russell lupin are represented.

In total, therefore, 17 Instagram accounts and associated ‘online traces’ were initially reviewed as part of this study. Each account was accessed via the Instagram link on the organisation’s official website. For example, the account ‘queenstownnz’ was accessed via the Instagram link on the Queenstown RTO website, www.queenstownnz.co.nz. Once access to an account had been gained, the visual component of all posts (i.e. the photo) were reviewed and each post containing an image of Russell lupin, along with associated comments, if any, and geolocation information, was screen-captured and saved as an ‘exhibit’ for further analysis (see for an example of a screen-captured ‘exhibit’).

The screen-capture in provides a useful example of the need to discuss ethical considerations in relation to the use of public Instagram content. The data used in this study was collected from public Instagram accounts and, as such, institutional ethics approval was waived. Yet as McCrow-Young (Citation2021) cautions ‘users’ perception of what it means to have a ‘public profile’ on Instagram’ (p. 26, emphasis ours) can vary considerably. The implication here is that issues to do with consent are opaque. As such, care needs to be taken, especially when representing individual user data. Following McKeown and Miller (Citation2020), no personal identifying markers (e.g. usernames, handles) are used in the thematic presentation of findings (e.g. quotes) or in the reproduction of screen-captures. For example, in all personal identifying markers have been removed using the eraser function on Microsoft Paint 3D.

Data collection and analysis

Of the 17 Instagram accounts and associated ‘online traces’ initially reviewed, 94 exhibits containing Russell lupin were collected for further qualitative content analysis. shows, proportionally, which accounts the exhibits were collected from.

Table 1. Overview of Instagram accounts reviewed, and exhibits collected for further analysis.

Each of the 94 exhibits was first subject to qualitative content analysis. For Patton (Citation2002) qualitative content analysis is a ‘qualitative data reduction and sense-making effort that takes a volume of … material and attempts to identify core consistencies and meanings’ (p. 453). The process of qualitative content analysis used in this study first involved determining appropriate coding categories. Following Hsieh and Shannon’s (Citation2005) work on qualitative content analysis, coding categories were derived from the data (visual and text) by the first author. Here, a random selection of posts was analysed, and an initial set of coding categories identified. The same selection of posts was then independently analysed by another member of the research team in order to confirm, or challenge, the accuracy of the coding categories. This ‘team coding’ approach, as Saldaña (Citation2009) refers to it, led ultimately to inter-coder agreement and interpretative convergence. Once inter-coder agreement had been achieved, a summative analysis of all 94 exhibits was conducted. During this phase, the analysis focused on the following:

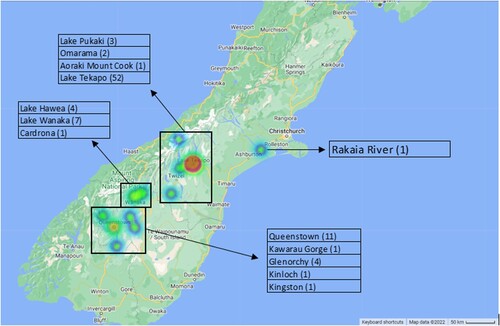

Geolocation: when a photo is uploaded to Instagram, the poster has the option to add the location. In all but five of the 94 posts, the location was provided. This information was then entered into the software Maptive where it was then possible to develop a heat map to show the geographical spread of posts (see ).

Visual analysis: involved extracting data relevant to each photo as a means to identify patterns in the uses of and for Russell lupin. The quality indicators included the following:

o A description of the landscape context (i.e. in addition to the Russel lupin, what landscape features are included in the photo? E.g. roadside, lakeside, open field, mixed – mountain/hill/lake/open field etc.).

o A description of the social context (i.e. what is happening in the photo? E.g. are there people/animals in the photo and, if so, what are they doing?).

o Centrality of Russell lupin (i.e. was the Russell lupin the main or partial focus of the photo?).

Text analysis of post, comments, and replies. The quality indicators included the following:

o Whether RTOs were portraying Russell lupin in posts as acceptable (e.g. ‘field of dreams’) or non-acceptable (no examples), or whether posts were ambiguous (e.g. ‘Lovely lupins at Lake McGregor. Although technically they are classified as invasive weeds they sure do have a pretty colour palette!’).

o Reactions on the part of audiences in terms of comments and replies to posts. Here analysis focussed again on whether audiences appeared to view lupin as acceptable (e.g. ‘Heaven!’) or non-acceptable (e.g. ‘purple weed’), or whether there were ambiguities (e.g. ‘Really they’re a weed, but they’re beautiful’). Quotes best highlighting the (non)acceptability of Russell lupin were selected, as were quotes best highlighting ambiguities in portrayals. Some of these quotes are presented in the findings section that follows.

For each exhibit where there were ambiguities in relation to portrayals of Russell lupin (n = 16 exhibits), a second, more in-depth, analysis of text data was conducted to better understand the explicit, and perhaps also latent, messages being communicated. In the section that follows, findings are presented thematically and draw on data from both phases of analysis to further support and illuminate arguments.

Findings

Favourable and storied representations

Perhaps unsurprisingly, almost all the photos of Russell lupin were taken in, nearby, or on the sides of major highways connecting, popular tourism hotspots such as Lake Tekapo/Takapō, Aoraki Mt Cook, Lake Wanaka, and Queenstown. This is well illustrated in the labelled heatmap in . Locations that are most popular for taking and sharing photographs of Russell lupin are also those that, in general, have the highest distribution of Russell lupin (see )

Figure 4. Geolocation data for 94 posts containing Russell lupin (Note: no. in brackets = no. of posts per location; geolocation data not available for 4 posts) (Map source: Maptive).

In the vast majority of posts (n = 78), the photo and accompanying comments appeared to communicate a strong and positive overall sentiment that Russell lupins are highly acceptable. This was true for both the organisation posting the content (e.g. RTOs) and the audience engaging with it (e.g. through ‘comments’). The notion of acceptability referred to here encompasses both an explicit and implicit celebration of the Russell lupin aesthetic. The message is clear – the Russell lupin is a species that belongs and even adds to the environment because of its perceived beauty.

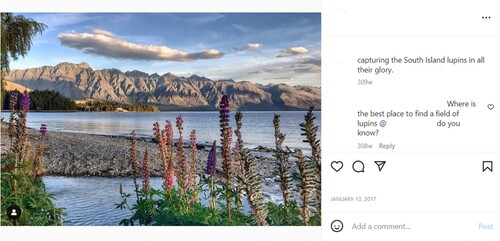

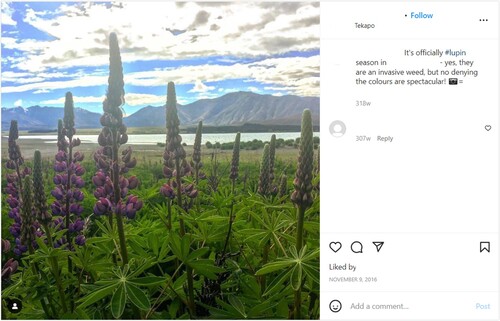

In terms of visual imagery, in most instances the Russell lupin was the main actor, with other elements of a landscape providing a supporting role. In almost half of all the photos posted (n = 40), ‘other’ elements included both a lake and hills/mountains. Based on this finding, an example of what could be considered a typical photo of Russell lupin in New Zealand, one where all three elements feature, can be seen in . Added to this were a number of other photos (n = 15) containing just an open field of Russell lupin with hills/mountains in the background.

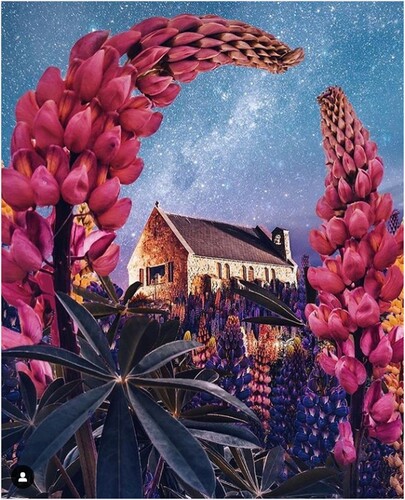

In some instances (n = 9), close-up photography was used, and the Russell lupin featured either on its own or as a means to frame/compliment/introduce some other element such as a famous landmark or a natural phenomenon. In such contexts, Russell lupin were afforded an almost ethereal quality; sublime, paradisical. This is well illustrated in , in which the Russell lupin is used in promotion that frames not only a popular tourist landmark (Church of the Good Shepherd, Lake Tekapo) but also the ‘dark sky’, a popular tourism attraction in its own right in this part of New Zealand which has International Dark Sky Reserve status (Dark Sky Project, Citation2022).

Figure 5. Church of Good Shepherd, Lake Tekapo, and Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve framed by Russell lupin.

As Larsen (Citation2006) notes, ‘Places have a dense materiality of roads, bridges, buildings, restaurants, monuments, cornfields, woods and so on’ (p. 77). We might, in certain locales, add to that list ‘Russell lupin’. And, as the discussion thus far suggests, in complementing other natural/built landscape elements Russell lupin are seen, by Instagram users, as a highly acceptable component of the landscape that adds value to the places where it grows (e.g. and ).

Visually, Russell lupin also appeared to be used, albeit to a lesser extent, as an aesthetic ‘prop’ to frame/complement the social consumption of place(s). Around a quarter of the photos (n = 25) included people and/or pets. Most of these included a single adult individual posing among Russell lupins; some smiling, some thoughtful, some with backs turned from the camera looking out at the landscape (e.g. ).

Such photos conveyed, whether deliberately or not, a sense of connection between human/animal, species (Russell lupin), and landscape. Such photos, when used in this way by RTOs to promote places, may serve to strengthen the ‘myths, desires and fantasies’ that constitute ones ‘imaginative geographies’ (Larsen, Citation2006, p. 78) in relation to lupin-rich landscapes and the affordances they bring. Furthermore, the images being conveyed through Instagram – especially those that include people/pets (and Russell lupin) performing place – offer audiences mediatised access to these imagined places and inviting behaviours such as Instagram ‘selfies’.

It was not, however, just the photos conveying the message that Russell lupins are a highly acceptable aesthetic. Indeed, the text amplified and strengthened that message. In 78 out of 94 posts analysed (83%), there was no indication in the text (e.g. poster comment, audience comments/replies) that Russell lupin should be considered anything but acceptable. Interestingly, the text, as a corpus, relayed a story of acceptability that, in many ways, connected the life cycle of Russell lupin to the seasonality of a tourist destination.

In considering posts as a collection of storied representations, RTOs appeared to use the combination of text and photo to first help build a sense of anticipation. In one example, a photo of a field of Russell lupin in bloom was captioned with ‘The Lupins are almost here!’. The audience – potential visitors – responded enthusiastically: ‘Can’t wait!!!’. In another example, a decrepit but highly photogenic wooden jetty reaches into a lake and is foregrounded by several Russell lupin in various stages of bloom. The caption reads: ‘Not long until more of these beauties will be out!’. In this example, the soon-to-be-blooming lupins juxtaposed against the crumbling wooden jetty highlights contrasting notions of flourishing (lupin-as-natural-feature) and decay (jetty-as-built-feature).

Next, the celebrations of Russell lupin in full bloom. Here, RTOs would again use photos and text in powerful combination to alert the audience to, and celebrate with them, the arrival of Russell lupin. In one example, a photo of a person standing in an open field of Russell lupin in bloom, whilst looking out to the lake and mountains in the background, is captioned with ‘Guess what time it is?! Lupins lupins lupins time!’. In another example, a field of Russell lupin can be seen in the foreground, with lake, mountains, and a rainbow in the background. The caption reads: ‘Lupins at Lake Pukaki. Rainbow as well … nice touch Mother Nature!’. Here, Russell lupin are represented as an integral part of the landscape, a species that naturally belongs in its surroundings, just like the mountains, lake, and rainbow. There were also subtle reminders that ‘blooming’ Russell lupin are – like tourism itself – seasonal. Captions such as ‘Lupin season in #Tekapo – it’s hard to tell where flowers end and sky begins. They’ll be at their best soon!’ reminds potential visitors to visit now. With this sentiment in mind, RTOs also use photos to suggest to audiences that experiencing Russell lupin is a ‘New Zealand MUST DO’, just as other iconic experiences such as bungy jumping are.

Finally, the end of the ‘lupin season’ (spring/summer) arrives and audiences are reminded that ‘This is what happens to our beautiful Lupins once they’ve finished flowering for the season. We think they’re still gorgeous in their own right’. In this example, several withered Russell lupin, replete with dead flowerheads, are pictured standing steadfast against a backdrop of snow-capped mountains. Even in a state of off-season decay, the Russell lupin continues to be celebrated. Furthermore, RTOs appeared to draw on the Russell lupin throughout autumn and winter as a way to remind audiences of that which was lost but would inevitably return, potentially informing trip planning. Thus, the process of building anticipation for what lay ahead (i.e. summer, lupin season) began again. For example, ‘We sure are missing these beautiful Summery scenes!’ captioned a photo of a sunlit lake foregrounded by brightly coloured lupins. Similarly, ‘These lupins bloom from November until just after Christmas - which means we're only months away from some EPIC landscapes! Who's excited?’.

In summary, of the posts analysed, most represented Russell lupin in an extremely positive and celebratory light. Both RTOs and audiences appeared almost reverential in their acceptance of this particular IAS, cherishing Russell lupin for its aesthetic value. Despite this, there were other instances, albeit rare, where the potential negative impacts of Russell lupin were alluded to in posts. In almost all such posts, however, negative messages continued to be embedded within a broader positive narrative underplaying the seriousness of the ecological threats. This resulted in there being a level of ambiguity in relation to these ‘other’ representations of Russell lupin.

Ambiguous representations

Ambiguous representations of Russell lupin were found in 16 of the 94 exhibits analysed (17%). In ten of those exhibits, the potential negative impacts of Russell lupin were highlighted by the RTO itself. In those ten exhibits, the photos used continued to showcase the aesthetic appeal of Russell lupin. The photos included Russell lupin in various landscape settings along with common features including open fields, lakes/rivers, and mountains (e.g. ).

In terms of the text used, RTOs tended to communicate messages that, either implicitly and/or explicitly, contained multiple contrasting/contradictory representations: Russell lupin is an IAS/weed; Russell lupin is relatively harmless, especially in areas where it is well established; Russell lupin adds aesthetic value to the landscape (author reflections). A good example of this ambiguity can be seen in the following text excerpt:

Enjoying the beauty of lupins at Lake Tekapo. Although quite pretty to look at, lupins are considered an invasive weed by the Department of Conservation (DOC). Lupins can alter the course of braided rivers and displace slower growing native plants. As such, they are carefully monitored by DOC to help prevent them from spreading to new areas. Nothing wrong with appreciating them where they’re already established though!

Lupin flowers in bloom at Lake Tekapo. Considered an invasive weed by the Department of Conservation (DOC), lupins can alter the course of braided rivers and displace slower growing native plants. As such, they are carefully monitored by DOC to help prevent them spreading to new areas. However, there’s certainly no harm in appreciating the lovely purple, white and pink colours of these existing flowers - just don’t plant any new ones!

Furthermore, the ambiguous messages communicated by RTOs in relation to the negative ecological impacts of Russell lupin fall short of highlighting all its potential impacts. For the most part, Russell lupin are shown in the Instagram posts of RTOs only to alter the course of braided rivers and displace slower growing native plants. What is not mentioned, though, is the way that Russell lupin provide shade for predators (e.g. feral cats, ferrets) of critically endangered native birds such as the Black stilt/kakī (Himantopus novaezelandiae) that would usually nest safely on the bare islands common to braided rivers. The partial, or selective, representation being communicated by RTOs underplays the seriousness of the ecological threat of Russell lupin for the Black stilt/kakī (Caruso et al., Citation2013), a bird that is considered as a taonga/living treasure by Māori and non-Māori but one that is also at risk of extinction (Department of Conservation, Citationn.d.). In so doing, this sort of selective process can be said to illustrate the RTOs’ ‘worldmaking’ power (Hollinshead, Citation2008), in that they appear to ‘purposely … privilege particular dominant/favoured representations [e.g. Russell lupin as benign beauty] … over and above other actual or potential representations [e.g. Russell lupin as quick spreading killer]’ (p. 643).

Consequently, because of the incomplete representations being communicated by RTOs, those viewers who are unfamiliar with the ecology of Russell lupin are likely to remain unaware of the full damage wrought by this IAS. Linked to this point, Instagram audiences receive no indication or warning from RTOs about common human practices that have facilitated the spread of Russell lupin and that are, therefore, to be avoided. For example, tourist bus operators have been known to provide tourists with Russell lupin seeds which they were encouraged to scatter along highway verges. The lack of warnings, coupled, with incomplete messaging on the part of RTOs about the threat of Russell lupin, helps perpetuate what Meurck (Citation2002) has previously shown to be ‘the farcical situation of the tourist industry promoting imagery and activities that are harmful or destructive to [New Zealand] biodiversity’ (p. 24).

It should also be noted that in several exhibits where Russell lupin were explicitly being referred to as a weed/invasive, any potential downsides were downplayed, and at the same time compensated for, with clear reminders that blooming Russell lupins are a welcome aesthetic: Lovely lupins … Although technically they are classified as invasive weeds they sure do have a pretty colour palette!

Another interesting finding relates to whether ‘immigrant’ species like the Russell lupin, which originated in North America, deserve to ‘belong’, just as native species do. In one example, an RTO posted a photo of a row of Russell lupin bordering a clump of wild thyme (another IAS) along with the caption ‘They may not be native, but the lupins and thyme really give a lift to Central Otago’s colour palatte (sic) during Spring’. The reply from one of the audience is: ‘Beautiful, and we’re not native either so I’m happy not to get too hung up about it’. The suggestion here is that all (beautiful?) species are welcome, regardless of whether they are native or immigrant. In so doing, these sorts of comments are somewhat representative of more ‘compassionate’ and inclusive narratives toward IAS (e.g. Wallach et al., Citation2020).

In relation to ‘Ambiguous representations’, the discussion thus far has focussed only on the ten exhibits wherein RTOs included, in an initial post, a reference to Russell lupin being an IAS. In the remaining six exhibits, it was audience members who, unprompted by the RTO, made similar references. In three of these exhibits, comments from audience members were similar to those of RTOs, with Russell lupin represented as a beautiful pest: Really they’re a weed, but they’re beautiful. In the other three exhibits, however, the comments become much less ambiguous (e.g. Purple weeds!). One audience member even went as far as to suggest that ‘They may look pretty but they are a horrible weed and should be removed’. Somewhat tellingly, of all the 94 exhibits analysed in total, this singular comment was the only occasion where removal of Russell lupin was proposed.

Discussion and conclusion

This study contributes on a number of fronts. First as an investigation into the touristic dimensions of invasive species, the findings reaffirm that public and visitor support for IAS management is by no means a given. While there may, to some degree, be a lack of knowledge about IAS among the travelling public (Bravo-Vargas et al., Citation2019; Koichi et al., Citation2012; Lovelock et al., Citation2022), in this study, even when individuals were aware of the negative impacts of the invasive plant, they still supported its retention within local landscapes. In this study, the retention of Russell lupins within the touristic landscapes of New Zealand continues to be championed by tourism organisations and audiences (e.g. potential visitors, locals) despite an awareness of the plants’ impacts upon braided river ecosystems and the endangered species of birds that those ecosystems support.

This continued acceptance of lupin appears to involve a process of rationalisation (‘we know they’re damaging but they are pretty’) on the part of both the RTOs and their audiences, in order to justify their ecologically unsustainable positions. Such processes of rationalisation have certainly been documented before in studies that seek to understand visitors’ engagement with contested sites or activities (e.g. McKercher et al., Citation2008) but to some extent we wonder if the ongoing promotion of Russell lupins by ‘official’ tourism organisations lends further power to such processes of rationalisation.

We find problematic the fact that the organisations which are continuing to champion the place of Russell lupins are (mostly) publicly funded RTOs. Whether this is a conscious and/or unwitting failure on the part of RTOs to meet their prescribed role with respect to the sustainable marketing and management of their destinations and the attractions and activities wherein (Styles et al., Citation2013; Weber & Wehrli, Citation2015) or simply their successful and opportunistic promotion a ‘natural’ attraction for the good of their destination is subject to debate. Estrella et al. (Citation2016) argue that while traditionally the responsibility of a RTO was limited to promoting a destination, ‘It is crucial to understand that RTOs are part of a wider network and they need to take their environment into account’ (p. 320). While they argue for RTOs to be role models for sustainable tourism, there is little evidence of this happening in practice (Wagenseil & Zemp, Citation2016). The deliberate or opportunistic exercising of agendas through promotional activities that, either way, serve to normalise and privilege unsustainable attractions is another good example of the ‘worldmaking’ power and agency of organisations such as RTOs (Hollinshead, Citation2008). Our research also demonstrates how social media platforms such as Instagram offer ever more powerful and convenient tools for RTOs to exercise their powers of persuasion. With this is mind, it is crucial that RTOs exercise their worldmaking power for good.

As long ago as 1987, Krippendorf argued for an ‘ecological approach’ to tourism marketing (Krippendorf, Citation1987). The contemporary expression of this can be seen in Jamal and Camargo’s (Citation2022) call for a move for responsible tourism marketing by RTOs, away from purely profit-driven motives that promote destinations ‘with the sole purpose of visitor and revenue growth’ (p. 717). Such a responsible tourism marketing approach would benefit the destination’s environmental sustainability, as well as enabling behavioural change on the part of visitors (Jamal & Camargo, Citation2022).

That behavioural change is possible is supported by research into public and visitor attitudes towards IAS, which has shown that positive changes are achievable if credible information is provided (Gawith et al., Citation2020; Lovelock et al., Citation2022; Ovenden, Citation2020). Novoa et al. (Citation2017) found that providing knowledge to the public about the harmful effects of IAS increased their support for management, even after receiving only a ‘limited amount of information provided on the origin and negative impacts of the target species’ (p. 3701). This has been found to hold true even for charismatic invasive plants such as Russell lupin; Junge et al. (Citation2019) found that after providing information on the invasiveness and ecological impact of a set of invasive plants (which included some attractive flowering plants), respondents’ aesthetic preferences for all species decreased significantly and that they also showed stronger support for more intensive control of the plants. Enhancing awareness in this way can also contribute more directly to IAS management, for example by reducing visitors’ potential to spread IAS and engaging them as ‘citizen scientists’ to report locations of IAS.

It may also be the case that RTOs and other interested stakeholders, in their ‘worldmaking-for-good’ capacity, have a responsibility to actively enhance awareness of, and engage audiences with, the very species’ that are threatened by IAS. In the context of New Zealand, and this study, this may mean RTOs ‘deselecting’ Russell lupin as a tool for regional promotion, and instead ‘selecting’ the elusive, but no less ‘charismatic’, kakī/black stilt, or flowering kowhai (a native tree species present in the Te Manahuna Mackenzie Basin). Doing so, as a responsible means to raise awareness of, and engagement with, such endangered native species would align with regenerative approaches to tourism that have been espoused (Pollock, Citation2020; Becken & Kaur, Citation2021), which would see RTOs and visitors contributing to positive ecological change within destinations.

While this research is focused specifically on Russell lupin, other IAS that are arguably more pervasive, but perhaps less charismatic, may also play a supporting role in RTO projections of place. This is well illustrated in some of the images displayed above, where, for example, wilding conifers including pine, larch, fir are evident – albeit not the foci of the images. These exotic IAS have infested iconic New Zealand landscapes and pose a significantly more widespread threat than Russell lupin by forcing out native flora and fauna en masse (Department of Conservation, Citation2023). It is important to note, however, that Russell lupin possesses two characteristics that together differentiate this species from other IAS in New Zealand, including wildling conifers: 1. Its status as an acknowledged environmental weed; and 2. Its beauty and resultant strong integration into the tourist experience. This combination of ‘beauty and beast’ (Lindemann-Matthies, Citation2016) characteristics warrants the current focus on this and similar species, among a raft of other IAS.

Regarding the bigger picture of tourism-IAS relationships, this study does point to the need to debate the net value of IAS. An ecosystem services approach has been utilised in this regard with some researchers considering the cultural ecosystem services for tourism and recreation that arise from IAS (Kueffer & Kull, Citation2017; Pejchar & Mooney, Citation2009; Vaz et al., Citation2018). While such an approach may be useful in recognising the ‘value’ of IAS (such as the species under consideration in this study), the profound disservices of IAS also need to be carefully accounted for, and consideration given to the likelihood that services and disservices may accrue differentially to different visitor groups, and different tourism stakeholders. For example, while Vaz et al. (Citation2018) observed how ‘non-native’ trees increased recreation and ecotourism services, this was only when considering data from official tourism entities; when data from tourists and recreationist who were specifically seeking natural experiences was accounted for, gross benefits from IAS did not accrue. Similarly, Kueffer and Kull (Citation2017) identified the role of Invasive plants in landscape homogenisation and the devaluing of cultural ecosystem services. There is a danger that the neoliberal assumptions of the ecosystem services approach (McCauley, Citation2006) coupled with the threats of IAS denialism (Russell & Blackburn, Citation2017) may lend credence to arguments for the retention of IAS, and even provide legitimacy for the deliberate anthropocentric spread of IAS for touristic economic gain. Such deliberate spread in the name of tourism and ‘beautification’ has happened in the past (Lovelock et al., Citation2022) so is not beyond the realms of imagination. As this study, and that of Vaz et al. (Citation2018) suggest, destination marketers and managers are crucial stakeholders in this debate, and efforts to raise awareness around IAS should prioritise destination organisations. Future research needs to explore the awareness and attitudes of destination marketers in this regard.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stu Hayes

Stu Hayes' main research interests are in the areas of recreation, with a particular emphasis on freshwater environments, and tourism education. He is also a Research Fellow on the Marsden-funded project 'Good Nature, Bad Nature'.

Brent Lovelock

Brent Lovelock is currently leading a Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden-funded project ('Good Nature, Bad Nature') exploring the relationships that different communities have with invasive species in New Zealand and how this may affect future management of these species.

Anna Carr

Anna Carr's research interests centre around cultural heritage and the management of tourism and recreation in protected areas. Anna's work on the Marsden-funded project 'Good Nature, Bad Nature' enables her to incorporate a passion for conserving Aotearoa's Indigenous biodiversity alongside furthering her understanding of how people relate to, recreate in and value the different dimensions of our natural environment.

Notes

1 As Small (Citation2012) explains, in past centuries lupin were regarded as ‘Penny Bean’, often used as play money, and thus there was a strong association between lupin and money.

References

- Anderson, L. G., Rocliffe, S., Haddaway, N. R., & Dunn, A. M. (2015). The role of tourism and recreation in the spread of non-native species: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 10(10), e0140833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140833

- Andrade, G. M. (2019). The paradox of culturally useful invasive species: Chuspatel (Typha domingensis) crafts of lake Patzcuaro, Mexico. California State University.

- Ansong, M., & Pickering, C. (2015). What’s a weed? Knowledge, attitude and behaviour of park visitors about weeds. PloS one, 10(8), Article e0135026. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135026

- Anthony, J. (2021). Invasive pest plant Russell lupin marketed as ‘native seeds’ by McGregor's. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/124054427/invasive-pest-plant-russell-lupin-marketed-as-native-seeds-by-mcgregors.

- Barnes, M. A., Deines, A. M., Gentile, R. M., & Grieneisen, L. E. (2014). Adapting to invasions in a changing world: invasive species as an economic resource. In L. H. Ziska & J. S. Dukes (Eds.), Invasive species and global climate change (pp. 326–344). CAB International.

- Beattie, J. (2011). Empire and Environmental Anxiety: health, science, art and conservation in South Asia and Australasia, 1800–1920. Springer.

- Becken, S., & Kaur, J. (2021). Anchoring “tourism value” within a regenerative tourism paradigm – A government perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1990305

- Beever, E. A., & Brussard, P. F. (2000). Charismatic megafauna or exotic pest? Interactions between popular perceptions of feral horses (Equus caballus) and their management and research. In T. P. Salmon, & A. C. Crabb (Eds.), Proceedings of the 19th International Vertebrate Pest Conference (pp. 413–418). University of California.

- Bhagwat, S. (2018). Non-native invasive species: Nature, society and the management of novel nature in the Anthropocene. In T. Marsden (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of nature (pp. 986–1012). SAGE.

- Bodey, T. W., Carter, Z. T., Haubrock, P. J., Cuthbert, R. N., Welsh, M. J., Diagne, C., & Courchamp, F. (2022). Building a synthesis of economic costs of biological invasions in New Zealand. Research Square, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13580

- Bolpagni, R. (2021). Towards global dominance of invasive alien plants in freshwater ecosystems: The dawn of the Exocene? Hydrobiologia, 848(9), 2259–2279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04490-w

- Bonanno, G. (2016). Alien species: to remove or not to remove? That is the question. Environmental Science & Policy, 59, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.02.011

- Bravo-Vargas, V., García, R. A., Pizarro, J. C., & Pauchard, A. (2019). Do people care about pine invasions? Visitor perceptions and willingness to pay for pine control in a protected area. Journal of Environmental Management, 229, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.07.018

- Bremner, A., & Park, K. (2007). Public attitudes to the management of invasive non-native species in Scotland. Biological Conservation, 139(3–4), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2007.07.005

- Cambray, J. A. (2003). The global impact of alien trout species—A review; with reference to their impact in South Africa. African Journal of Aquatic Science, 28(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085914.2003.9626601

- Campelo, A., Aitken, R., & Gnoth, J. (2011). Visual rhetoric and ethics in marketing of destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362777

- Caruso, B., Ross, A., Shuker, C., & Davies, T. (2013). Flood hydraulics and impacts on invasive vegetation in a braided river floodplain, New Zealand. Environment and Natural Resources Research, 3(1), 92. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v3n1p92

- Crowley, S. L., Hinchliffe, S., & McDonald, R. A. (2019). The Parakeet Protectors: understanding opposition to introduced species management. Journal of Environmental Management, 229, 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.11.036

- Dark Sky Project. (2022). Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve. Retrieved August 16, 2022, from https://www.darkskyproject.co.nz/our-team-and-story/dark-sky-reserve/.

- De Lange, P., Norton, D., Courtney, S., Heenan, P., Barkla, J., Cameron, E., & Townsend, A. (2009). Threatened and uncommon plants of New Zealand (2008 revision). New Zealand Journal of Botany, 47(1), 61–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288250909509794

- Department of Conservation. (2023). Wilding conifers. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/pests-and-threats/weeds/common-weeds/wilding-conifers/.

- Department of Conservation. (n.d.). Black stilt/kakī. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/birds/birds-a-z/black-stilt-kaki/.

- Diagne, C., Leroy, B., Vaissière, A. C., Gozlan, R. E., Roiz, D., Jarić, I., Salles, J-M., Bradshaw, C. J. A., & Courchamp, F. (2021). High and rising economic costs of biological invasions worldwide. Nature, 592(7855), 571–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03405-6

- Dinat, D., Echeverri, A., Chapman, M., Karp, D. S., & Satterfield, T. (2019). Eco-xenophobia among rural populations: The Great-tailed Grackle as a contested species in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 24(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2019.1614239

- Estévez, R. A., Anderson, C. B., Pizarro, J. C., & Burgman, M. A. (2015). Clarifying values, risk perceptions, and attitudes to resolve or avoid social conflicts in invasive species management. Conservation Biology, 29(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12359

- Estrella, G., Zemp, M., & Wagenseil, U. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: The role of modern destination management organizations. In BEST EN Think Tank XVI Corporate Responsibility in Tourism-Standards Practices and Policies (pp. 310–325). BEST Education Network

- Fatanti, M. N., & Suyadnya, I. W. (2015). Beyond user gaze: How Instagram creates tourism destination brand? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 211, 1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.145

- Fusté-Forné, F. (2022). The portrayal of Greenland: A visual analysis of its digital storytelling. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(11), 1696–1701. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1974359

- Gawith, D., Greenaway, A., Samarasinghe, O., Bayne, K., Velarde, S., & Kravchenko, A. (2020). Socio-ecological mapping generates public understanding of wilding conifer incursion. Biological Invasions, 22(10), 3031–3049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-020-02309-2

- Gretzel, U. (2017). # travelselfie: A netnographic study of travel identity communicated via Instagram. In S. Carson, & M. Pennings (Eds.), Performing cultural tourism: Communities, tourists and creative practices (pp. 115–127). Routledge.

- Hakim, L., Leksono, A. S., Purwaningtyas, D., & Nakagoshi, N. (2005). Invasive plant species and the competitiveness of wildlife tourist destination: A case of sadengan feeding area at Alas Purwo National Park, Indonesia. Journal of International Development and Cooperation, 12(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.15027/29767

- Hall, C. M. (2015). Tourism and biological exchange and invasions: A missing dimension in sustainable tourism? Tourism Recreation Research, 40(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1005943

- Hall, C. M., James, M., & Baird, T. (2011). Forests and trees as charismatic mega-flora: Implications for heritage tourism and conservation. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 6(4), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2011.620116

- Hollinshead, K. (2008). Tourism and the social production of culture and place: Critical conceptualizations on the projection of location. Tourism Analysis, 13(5–6), 639–660. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354208788160540

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., Correia, M. B., Jambrino-Maldonado, C., & de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. (2020). Instagram as a co-creation space for tourist destination image-building: Algarve and Costa del Sol case studies. Sustainability, 12(7), Article 2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072793

- InspiredNZ.com. (2021). Mackenzie Country. Retrieved from https://inspirednz.com/2018/05/23/lupins-mackenzie-country/

- Hudson, S., & Miller, G. A. (2005). The responsible marketing of tourism: the case of Canadian Mountain Holidays. Tourism Management, 26(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.06.005

- Jamal, T., & Camargo, B. (2022). Responsible tourism marketing. In D. Buhalis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of tourism management and marketing (pp. 717–719). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Jamal, T., & Camargo, B. A. (2014). Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the just destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.786084

- Junge, X., Hunziker, M., Bauer, N., Arnberger, A., & Olschewski, R. (2019). Invasive alien species in Switzerland: Awareness and preferences of experts and the public. Environmental Management, 63(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1115-5

- Koichi, K., Cottrell, A., Sangha, K. K., & Gordon, I. J. (2012). Are feral pigs (Sus scrofa) a pest to rainforest tourism? Journal of Ecotourism, 11(2), 132–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2012.703672

- Kourantidou, M., Haubrock, P. J., Cuthbert, R. N., Bodey, T. W., Lenzner, B., Gozlan, R. E., Nuñez, M. A., Salles, J-M., Diagne, C., & Courchamp, F. (2022). Invasive alien species as simultaneous benefits and burdens: Trends, stakeholder perceptions and management. Biological Invasions, 24, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-021-02727-w

- Kozinets, R. V. (2020). Netnography: The essential guide to qualitative social media research (Vol. 3). Sage

- Krippendorf, J. (1987). Ecological approach to tourism marketing. Tourism Management, 8(2), 174–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(87)90029-X

- Kueffer, C., & Kull, C. (2017). Non-native species and the aesthetics of nature. In M. Vilà, & P. Hulme (Eds.), Impact of biological invasions on ecosystem services (pp. 311–324). Springer.

- Laestadius, L. (2017). Instagram. In L. Sloan, & A. Quan-Haase (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media research methods (pp. 573–592). SAGE.

- Larsen, J. (2006). Picturing Bornholm: Producing and consuming a tourist place through picturing practices. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 6(2), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250600658853

- Lindemann-Matthies, P. (2016). Beasts or beauties? Laypersons’ perception of invasive alien plant species in Switzerland and attitudes towards their management. NeoBiota, 29, 15. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.29.5786

- Liu, T. M., & Tien, C. M. (2019). Assessing tourists’ preferences of negative externalities of environmental management programs: A case study on invasive species in Shei-Pa national park, Taiwan. Sustainability, 11(10), Article 2953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102953

- Lovelock, B. (2007a). ‘If that's a moose, I'd hate to see a rat!’ Visitors’ perspectives on naturalness and their consequences for ecological integrity in peripheral natural areas of New Zealand. In D. K. Müller, & B. Jansson (Eds.), Tourism in peripheries: Perspectives from the far north and south (pp. 124–140). CABI.

- Lovelock, B. (2007b). An introduction to consumptive wildlife tourism. In B. Lovelock (Ed.), In tourism and the consumption of wildlife (pp. 25–52). Routledge.

- Lovelock, B., Ji, Y., Carr, A., & Blye, C. J. (2022). Should tourists care more about invasive species? International and domestic visitors’ perceptions of invasive plants and their control in New Zealand. Biological Invasions, 24, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-022-02890-8

- Malpica-Cruz, L., Haider, W., Smith, N. S., Fernández-Lozada, S., & Côté, I. M. (2017). Heterogeneous attitudes of tourists toward Lionfish in the Mexican Caribbean: Implications for invasive species management. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, Article 138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00138

- McCauley, D. J. (2006). Selling out on nature. Nature, 443(7107), 27–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/443027a

- McCrow-Young, A. (2021). Approaching Instagram data: reflections on accessing, archiving and anonymising visual social media. Communication Research and Practice, 7(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2020.1847820

- McKeown, J. K., & Miller, M. C. (2020). #tableforone: Exploring representations of dining out alone on Instagram. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(5), 645–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1613245

- McKercher, B., Weber, K., & Du Cros, H. (2008). Rationalising inappropriate behaviour at contested sites. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802154165

- McNeely, J. A. (2001). An introduction to human dimensions of invasive alien species. In J. A. McNeely (Ed.), The great reshuffling: Human dimensions of invasive alien species (pp. 5–22). IUCN Publishers.

- Meurck, C. D. (2002). Threats to native plants and niches for survival in New Zealand cultural landscapes. Canterbury Botanical Society Journal, 36, 18–25.

- Milanović, M., Knapp, S., Pyšek, P., & Kühn, I. (2020). Linking traits of invasive plants with ecosystem services and disservices. Ecosystem Services, 42, Article 101072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101072

- Morgan, G., & Simmons, G. (2014). Predator free Rakiura: An economic appraisal. Morgan Foundation, Wellington, 52.

- National Park Service. (2021). Lupine, a controversial plant. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/lupine.htm.

- Nautiyal, R., Albrecht, J., & Carr, A. (2022). Can destination image be ascertained from social media? An examination of Twitter hashtags. Tourism and Hospitality Research, https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221119380

- Nikodinoska, N., Foxcroft, L. C., Rouget, M., Paletto, A., & Notaro, S. (2014). Tourists’ perceptions and willingness to pay for the control of Opuntia stricta invasion in protected areas: A case study from South Africa. Koedoe: African Protected Area Conservation and Science, 56(1), 1–8. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC155274

- Novoa, A., Dehnen-Schmutz, K., Fried, J., & Vimercati, G. (2017). Does public awareness increase support for invasive species management? Promising evidence across taxa and landscape types. Biological Invasions, 19(12), 3691–3705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1592-0

- Oded, C., & Ram, Y. (2015). Tourism is not only the vector of biological invasion but also the victim: Evidence from Israel. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1086130

- Onozuka, M., & Osawa, T. (2022). Utilization potential of alien plants in nature-based tourism sites: A case study on Agave americana (century plant) in the Ogasawara Islands. Ecological Economics, 195, Article 107362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107362

- Ovenden, K. (2020). Kauri Dieback Track User Study 2020. Auckland Council, Te Kaunihera o Tāmaki Makaurau.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed). SAGE Publications.

- Pearce, F. (2016). The new wild: Why invasive species will be nature's salvation. Beacon Press.

- Pejchar, L., & Mooney, H. A. (2009). Invasive species, ecosystem services and human well-being. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24(9), 497–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.016

- Pickering, C., & Mount, A. (2010). Do tourists disperse weed seed? A global review of unintentional human-mediated terrestrial seed dispersal on clothing, vehicles and horses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(2), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903406613

- Pollock, A. (2020). Regenerative tourism – Taking sustainable tourism to the next level in paladini, G. Tomahawk Impact Hub. Retrieved June 6, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4YE54zPI2pE&t=898s.

- Reaser, D. (2001). Invasive alien species prevention and control: The art and science of managing people. In J. A. McNeely (Ed.), The great reshuffling: Human dimensions of invasive alien species (pp. 89–104). IUCN Publishers.

- Robinson, C. J., Smyth, D., & Whitehead, P. J. (2005). Bush tucker, bush pets, and bush threats: Cooperative management of feral animals in Australia's Kakadu National Park. Conservation Biology, 19(5), 1385–1391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00196.x

- Russell, J. C., & Blackburn, T. M. (2017). The rise of invasive species denialism. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.10.012

- Russell, J. C., Innes, J. G., Brown, P. H., & Byrom, A. E. (2015). Predator-free New Zealand: Conservation country. BioScience, 65(5), 520–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biv012

- Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

- Schori, J., Gale, S., Hines, C., & Nelson, D. (2021). Project River Recovery Annual Report. Department of Conservation. Retrieved from https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/land-and-freshwater/freshwater/prr/annual-report-2020-21.pdf

- Schneider, I. E., & Qian, X. (2014). Minnesota tourism industry perceptions of invasive species and their control. University of Minnesota Tourism Center.

- Scott, D., Maunsell, A., Pollock, K., Laliberte, E., Jenkins, T., Covacevich, N., & Simpson, S. (2018). Thirty-six years (1981–2017) of Mt John pasture trials. Journal of New Zealand Grasslands, 269–275. https://doi.org/10.33584/jnzg.2018.80.362

- Selge, S., Fischer, A., & van der Wal, R. (2011). Public and professional views on invasive non-native species – A qualitative social scientific investigation. Biological Conservation, 144(12), 3089–3097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.09.014

- Shackleton, R. T., Richardson, D. M., Shackleton, C. M., Bennett, B., Crowley, S. L., Dehnen-Schmutz, K., Estévez. R. A., Fisher, A., Kueffer, C., Kull, C. A., Marchante, E., Novoa, A., Potgieter, L. J., Vaas, J., Vaz, A. S., & Larson, B. M. H. (2019a). Explaining people's perceptions of invasive alien species: A conceptual framework. Journal of Environmental Management, 229, 10–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.045

- Shackleton, R. T., Shackleton, C. M., & Kull, C. A. (2019b). The role of invasive alien species in shaping local livelihoods and human well-being: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 229, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.05.007

- Small, E. (2012). 38. Lupins – Benefit and harm potentials. Biodiversity, 13(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2012.658327

- Smith, V. L., & Font, X. (2014). Volunteer tourism, greenwashing and understanding responsible marketing using market signalling theory. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(6), 942–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.871021

- Statista. (2022). Most popular social networks worldwide as of January 2022, ranked by number of monthly active users. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/.

- Styles, D., Schönberger, H., & Galvez-Martos, J. L. (2013). Best environmental management practice in the tourism sector. European Commission Joint Research Centre.

- Sullivan, C. J. (2019). Too many American icons: Conflicting ideologies of wild horse management in the American west [doctoral dissertation]. Retrieved from North Dakota State University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2305944731?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true.

- Thomson, A. (2019). Little Englanders should welcome alien trees. The Times, Retrieved May 22, 2019, from https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/little-englanders-should-welcome-alien-trees.

- Tonellotto, M., Fehr, V., Conedera, M., Hunziker, M., & Pezzatti, G. B. (2022). Iconic but invasive: The public perception of the Chinese windmill palm (Trachycarpus fortunei) in Switzerland. Environmental Management, 70, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-022-01646-3

- van Wilgen, B. W. (2012). Evidence, perceptions, and trade-offs associated with invasive alien plant control in the Table Mountain National Park, South Africa. Ecology and Society, 17(2), https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04590-170223