ABSTRACT

Different community groups and members hold varying power positions in tourism development discussions and decision-making. From the sustainable development perspective, tourism planning and management should involve a diversity of voices, including also those with limited political or economic power. This article focuses on relatively little studied young people’s views on tourism development. The article uses the concept of social innovation for analysing local youths’ needs and propositions for transforming tourism towards sustainability. Empirical data is derived from ethnographic research and a design anthropology-oriented workshop for young adults in Kemi, northern Finland. At the workshop, social innovations were used to imagine alternative futures for local life and the role of tourism in development. The participants co-created three social innovation propositions for enhancing the flow of information regarding tourism, developing activities, liveliness and spaces to hang out, and attracting passing-by visitors. These propositions reflect sustainability transformations that recognise young adults’ inclusion in tourism planning, create more inclusive services for locals, and enhance diverse, locally grounded, and socially valuable tourism. Even though the propositions are dependent on existing power structures, they challenge the status quo of tourism planning and development.

Introduction

For a relatively long time, community aspects have been considered crucial in tourism development and planning (Han et al., Citation2019; Murphy, Citation1985; Okazaki, Citation2008). However, community participation, in general, or specific community-based tourism (CBT) development, has been criticised for aiming to facilitate (selected) local views in business-oriented means instead of empowering wider groups of residents and stakeholders (Blackstock, Citation2005; Higgins-Desbiolles & Bigby, Citation2022; Saarinen, Citation2019). Such development can be exclusive for local people and host communities (Wearing & Darcy, Citation2011). This poses a challenge for enhancing sustainability through tourism development.

Canosa et al. (Citation2016, p. 327) have indicated that although community approaches and CBT research have reached a certain level of maturity, ‘the ‘voices’ of marginal members of host communities such as children and young people remain unheard’ (see also Koščak et al., Citation2021). Although young people are often considered as potential future drivers of change in tourism and local development (Seraphin et al., Citation2020), their possibilities to participate in decision-making are often limited and their competences can be questioned (Canosa et al., Citation2017; Canosa & Graham, Citation2016). However, the inclusion of young people’s perspectives can open up important matters to consider in sustainable tourism management beyond the traditional business and political decision-making structures (see Giampiccoli & Saayman, Citation2014; Jourdan & Wertin, Citation2020; Mayaka et al., Citation2019). This needed better involvement and empowerment of local young people in tourism development calls for in-depth research (see Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2020; Seraphin et al., Citation2020).

Conventional development and planning do not often take into account the possibilities of tourism to act as a transformative force for locals. While it is acknowledged that tourism can create positive transformative experiences for tourists (see Chhabra, Citation2021), little is known about tourism’s transformative possibilities to local people. Majority of transformative tourism research focuses on the tourist perspective or other stakeholders, which can exclude local perspectives and needs. In this respect, Rus et al. (Citation2022) have found that only a small fraction touches upon the host perspective. Therefore, as Rus et al. (Citation2022) note, studying the relationship between transformative tourism and sustainability is highly needed.

The article studies young people’s perspectives on how to make tourism more sustainable and a positively transformative force also for locals. This is done by utilising the idea of social innovations that can be regarded as collaborative processes and outcomes transforming the status quo by crossing and challenging the existing organisational relationships, rules, and boundaries (Mosedale & Voll, Citation2017; Voorberg et al., Citation2015). The social innovation framework includes identifying social needs and contextually novel ideas for changing the status quo (in tourism development), as well as studying co-operation for realising such ideas and processes. Ultimately, such transformative processes are hoped to create social value. In this article, the approach is used for identifying social needs for change as well as studying collaborative and co-creative ways aiming towards sustainability in tourism. The transformative nature of social innovations is used to examine potential propositions and ideas beyond the traditional tourism innovations and development processes that are often in the hands of private and formal public sectors (see Ilie & During, Citation2012).

Specifically, the article develops further an understanding of tourism development towards the inside (Nogués-Pedregal et al., Citation2017) of a community from the perspective of young people. However, this is not to indicate that they should dominate tourism decision-making. Rather, the interest lies in understanding power relations in tourism in a constructivist and relational sense (Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2020) by paying attention both to the lack of power and the opportunities of empowerment on a community level. This also requires understanding local young people as more than hosts directly involved in tourism and also approaching the place in which tourism takes place both as a destination and a place of residence (also Higgins-Desbiolles & Bigby, Citation2022). By doing so, the article aims at widening the perspectives for imagining sustainable ways of conducting tourism based on the developed social innovation approach.

The article is based on ethnographic research that was conducted in 2019–2020 in Kemi, northern Finland. Kemi offers an example of a city developing tourism yet simultaneously undergoing transformations with regard to economic struggles, changes in livelihood structure, aging population, and decline in number of habitants (see e.g. Hörnström et al., Citation2015). These socio-economic changes are framing young people’s possibilities to find employment and improve wellbeing in their hometown. The main data used in this article was collected in a design anthropology-oriented workshop for local young adults. At the workshop, the current state of tourism was analysed, and the idea of social innovation was used to identify desired changes and imagine alternative futures. As a result, the participants were asked to co-create social innovation propositions for making tourism more relevant in their everyday environment.

The aim is to study the role of local young people in relation to the sustainability of tourism development. This is done by exploring what kind of social innovation propositions local young people suggest for transforming tourism in their surroundings. The research questions are:

What is the role of young people in relation to the sustainability of tourism in a community context?

What kind of social innovation propositions do local young people suggest for transforming tourism and how do these propositions contribute to sustainability?

The next section discusses the role of young people in relation to the sustainability of tourism presents the social innovation framework for studying the issue. The article then introduces the research site of Kemi, as well as the methodological approaches of ethnographic research and the designing of anthropology-oriented social innovation workshop followed by presentation and discussion of findings. The conclusion involves synthesizing the findings and discussing the implications.

Widening the viewpoints

Young people’s perspectives and sustainability of community inclusion in tourism

Tourism is widely considered as having a capacity to enhance sustainable development through, for instance, social inclusion and local employment (Han et al., Citation2019; Saarinen, Citation2020). Previous studies have well demonstrated the potential downsides and risks of tourism becoming a locally exclusive rather than an inclusive social force contributing to sustainability and local wellbeing. Despite the fact that community involvement in tourism aims to contribute to sustainability (Han et al., Citation2019), related initiatives and development processes are usually dominated by the private and formal public sectors. Moreover, sustainable tourism development is often based on economic and industry-oriented targets (see Burns, Citation1999; Hall, Citation2010; Saarinen, Citation2021).

Overemphasising the economic needs and the targets for maximising growth (Gössling et al., Citation2016) can lead to a situation where the tourism-based environments and benefits are almost solely directed towards the outside rather than towards the inside. In other words, tourism development aims more at pleasing visitors instead of directing the development actions for local communities (Nogués-Pedregal et al., Citation2017). This can lead to the formation of enclavic tourism spaces (Saarinen, Citation2017), which are not open for local people and their recreational needs, for example.

At the same time, however, a growing tourism industry has become a habitually used strategy for local and regional development with hopes of bringing more vitality and employment opportunities, especially in peripheral regions (Saarinen, Citation2019). Employment opportunities in tourism are often expected to attract young adults to stay or migrate to areas with ageing and declining populations (see Duncan et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, it is not self-evident that the growing tourism industry employs local people or offers young people meaningful working life opportunities (see Bianchi, Citation2009; Partanen & Sarkki, Citation2021).

Tourism can also contribute to place-making that attracts young people by offering more abundant leisure time activities and amenities as well as social relationships (Möller, Citation2016) and encourage the local young people to stay in the area. Although young people are often considered a key group whose perspectives should be taken into consideration in order to advance social sustainability, young people’s perspectives are a relatively little studied area in sustainable tourism in general, and in tourism development in particular (Canosa et al., Citation2016). There are, however, some recent studies on young people as hosts have highlighted their perceptions and attitudes towards tourism (Koščak et al., Citation2021) or experiences of how it is to grow up in a popular tourist destination (Canosa et al., Citation2018).

Social innovations for challenging the status quo in (Sustainable) tourism development

Both in tourism and beyond, there has been increasing interest in social innovations in research (see Booyens & Rogerson, Citation2016; Mosedale & Voll, Citation2017; Mumford, Citation2002). In general, social innovations can be characterised as collaborative processes and outcomes, which cross and challenge organisational boundaries, rules, and relationships by emphasising multi-stakeholder perspectives (Voorberg et al., Citation2015). Neumeier (Citation2012, p. 65) has defined social innovations ‘as a change in the attitudes, behaviour or perceptions of a group of people joined in a network of aligned interests that, in relation to the group’s horizon of experiences, leads to new and improved ways of collaborative action in the group and beyond.’

In the tourism context, Mosedale and Voll (Citation2017) have considered social innovations as social outcomes or processes of collaborative innovation, which benefit from co-operation and co-production creating changes in social processes, relations, and practices. Therefore, co-creation and sharing that guide tourism planning, development, and management are crucial in social innovations (see Mumford & Moertl, Citation2003) that lead to ‘novel, community-produced solutions to social problems’, which do not primarily aim for economic profit but rather for social value creation (Jungsberg et al., Citation2020, p. 279). Yet, in some instances business-originating innovations, which are created for example in collaboration with non-business partners, can also be defined as social innovations if their aim is to respond to societal needs (see Mirvis et al., Citation2016).

In a similar fashion as a community approach in tourism (Knight & Cottrell, Citation2016; Murphy, Citation1985), social innovations are bottom-up oriented. In addition, social innovations can highlight the needs and initiatives of those traditionally excluded in local development and decision-making. In a tourism context, social innovations can be seen as a potential for transforming and challenging traditional power structures and unsustainable conditions linked with tourism. Moreover, social innovations can also be considered as a way of creating social value for local communities (Kettunen, Citation2021), suggesting that the transformative nature of social innovations can challenge organisational boundaries and industry-oriented innovations (see Ilie & During, Citation2012). This can help in widening the perspectives to consider in tourism development by shedding light on the community members beyond the public and private sectors and identifying more diverse needs on a local level.

Here, social innovations are utilised as a tool to foster transformative tourism and promote young people’s perspectives; to understand the needs for change on a community level and to study propositions, which aim at collaboratively challenging the status quo of tourism and local life in general. Studying social innovations in tourism from the perspectives of young people presents a novel perspective in sustainable tourism research and development. Despite their often marginalised position, this article builds on approaches that consider young people as active drivers of change (Horton et al., Citation2013; Partanen & Sarkki, Citation2021) and capable of expressing their views (Canosa, Wilson, & Graham Citation2018) and creating more positive narratives and development processes for localities (Kamuf & Weck, Citation2021; see Soini & Birkeland, Citation2014).

Materials and methodology

For understanding tourism from a local perspective, ethnographic research was conducted in Kemi in 2019–2020 by the first author (Partanen, Citation2022; Partanen & Sarkki, Citation2021). Kemi is a city of 21,000 habitants in northern Finland, in a region called as Sea-Lapland, mostly known economically for its pulp and paper industry tradition. Like many sparsely populated areas in the Nordic countries (Jungsberg et al., Citation2020), Kemi has struggled with an ageing population, limited access to services, and out-migration, especially of young people. Since the 1980s, tourism development has been utilised as a strategy to diversify Kemi’s economic base and livelihood structure, and it is expected to bring new vitality and employment to the city. Today, there are two city-owned main attractions, the SnowCastle resort area and icebreaker Sampo that are both directed to mostly international tourists, and several small tourism-affiliated companies in services, dining, accommodation, and activities. In 2019, tourism employed 840 person in Kemi-Tornio area (Lapin luotsi, Citation2023).

In Kemi-Tornio area, international tourism has been growing fast especially in 2017–2019, right before the Covid-19 pandemic (Lapin luotsi, Citation2023). The city has purposefully aimed for growth by reconstructing a SnowCastle resort area and renovating the icebreaker Sampo. In 2020, overnight stays in Kemi were 43,749, of which domestic tourism represented 22,086 stays and international tourism 21,663 stays. The year 2021 represents a clear drop in international travel, whereas domestic tourism has continued rather strong despite – or perhaps, also due to – the pandemic. In 2022, overnight stays in Kemi were 39,186, of which 28,841 stays represented domestic tourists and international 10,345. (Statistics Service Rudolf, Citation2023.) In general, tourism has become a rather approved and supported livelihood in Kemi. Yet, there are certain issues the locals criticise, such as using public funds for tourism development and constructing services that do not appear welcoming or that are financially inaccessible for local visitors.

This article is interested in both understanding unsustainable conditions and studying ways forward. The purpose is to be ‘critical and rooted, explanatory and actionable’ (Refstie, Citation2018, p. 201). The ethnographic finding that tourism in Kemi has initiated varying opinions among the locals, and the fact that tourism is mainly planned and developed by the private and public sectors, highlights the need to study tourism from an alternative perspective, in this case, that of the youth. To study rooted and actionable ways forward, the article derives from participatory action research (Kindon, Citation2021). This is done by using design anthropology, which integrates and develops the traditional qualities of anthropology and ethnography into ‘new modes of research and collaboration, working towards transformation without sacrificing empathy and depth of understanding’ (Gunn et al., Citation2013, p. 4).

Methods in design anthropology vary among different forms of intervention for creating contextual knowledge and developing solutions (Gunn et al., Citation2013). The workshop approach was chosen as a method as it enabled thinking about and co-creating transformation ideas in tourism development and management. The ethnographic research prior to the workshop formed a basis for heading towards the actionable (Refstie, Citation2018) as it helped to contextualise and design the workshop agenda as well as to facilitate discussions. Moreover, holding a tourism-related workshop in an unconventional space, a national guidance centre for young people called Ohjaamo (Ohjaamo, Citation2023), itself challenges the power relations in terms of who to include in tourism development and in which spaces the planning is carried out.

During ethnographic research conducted before the workshop, three city employees working with young people in Kemi were interviewed to gain a better understanding of the position of the city’s young people. With their help, the workshop was organised in October 2020.Footnote1 The employees commented on the researchers’ plans for the content of the workshop and attended part of the workshop near the end to discuss outcomes. They also helped in recruiting the workshop participants by sharing a poster made by the researchers in their information channels. For instance, they informed about the event at the Ohjaamo space, which was later used for organising the workshop. Seven young adults, aged 17–29, participated. Some of the participants were studying tourism in the local vocational school, while others found the topic interesting in other ways. The workshop participants lived in Kemi or studied in Kemi yet lived in a nearby town.

The researchers aimed to study tourism and the views of young people with a certain sensitivity, reflexivity (see Ateljevic et al., Citation2005), and wider cultural understanding of the lives of local young people. Ethical aspects were addressed by obtaining informed consent from the participants. This was done by providing participants with written documents explaining how the data shall be processed and archived and letting them decide how their personal data shall be used. Overall, the research complies with the guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK, Citation2019). All the participants were over the age of 15 and able to independently decide on their participation in the research. However, as the participants were of young age, the researchers found it especially important to protect their identities. Any identifying details shall not be published anywhere. Moreover, it was central to reflect on the researchers’ positions as facilitators of the workshop. The researchers made every effort to provide a safe space for the participants to express their ideas and to keep their views at the very core of the discussion.

The workshop

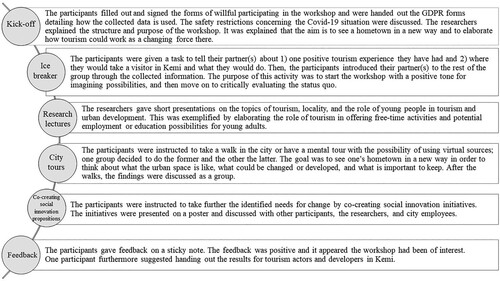

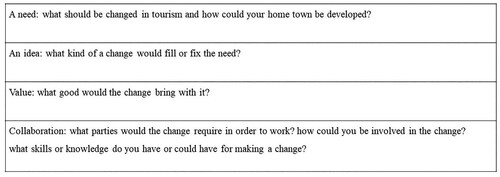

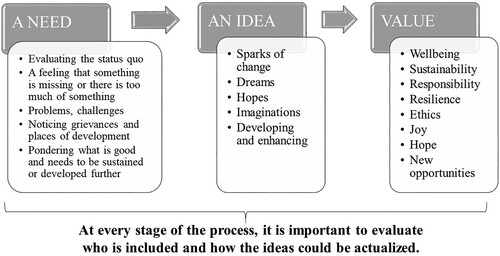

A detailed structure of the workshop is demonstrated in . The task of ‘co-creating social innovation propositions’ will be explained in further detail as it is the most central part of the workshop related to the scope of this article. There, the researchers aimed to popularise the academic conceptualisations of social innovations by using a generalising slide (). It was explained that social innovations are usually based on a need, which requires change. After the need has been identified, a proposition of how to change the status quo is formed. Once the idea has been realised, it creates positive social value. It was furthermore noted that social innovations are social in a sense that they are often formed collaboratively. Thus, it is important to think about who to involve in the process and what it takes to realise the ideas.

Figure 2. The popularisation of social innovations (translated from the original version in Finnish).

Next, the participants were instructed to convert their tentative ideas into a more structured form in order to create social innovation propositions. The participants divided into two groups and were instructed to make a poster for visualising their propositions. The following sheet with the headings of need, idea, value, and collaboration assisted in this task (). The participants were responsible for organising their work, and the researchers were available, assisted when needed, and encouraged to express their views.

Many needs were identified in the previous group discussion, and both groups mostly chose to refine and develop their ideas by imagining alternative ways of doing things. Finally, the participants co-created three social innovation propositions, which were discussed among the participants, researchers, and the invited city employees with an emphasis on thinking about the role of young people in making changes.

Analysing the data

The workshop discussions were recorded and transcribed. The data were examined through the social innovation framework by analysing the participants’ expressed needs behind the social innovation propositions and their transformative ideas as well as the identified potential values the propositions could bring, if actualised. The relevance of tourism for local communities was analysed by examining approaches of current tourism towards the inside and towards the outside and its development in Kemi from the young people’s points of view. In addition, the barriers and pathways to young people’s participation and inclusion in tourism development were interpreted in relation to research literature. On a general level, the results were analysed and discussed against the sustainability of community involvement in tourism.

Young people imagining more sustainable tourism within their communities

The workshop discussions and social innovation propositions analysed here are considered as manifesting young people’s agency in imagining alternative development paths and taking part in developing tourism. Moreover, the discussions along with the propositions show that young people are willing to initiate community-driven social innovations that would contribute to enhancing their hometown as a simultaneous place of residence and tourism. Yet, there are many barriers to participation and the realisation of the propositions.

Social innovation propositions

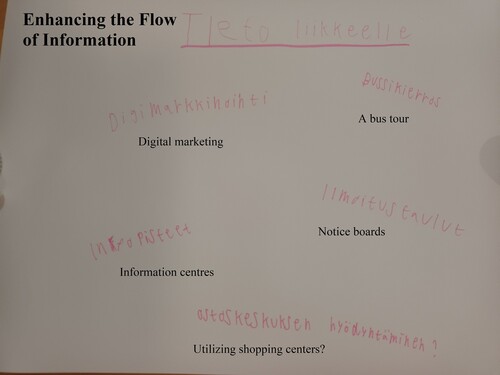

In the workshop, young people’s ideas revolved around questions about the position of youth groups in tourism and local development and the relationship between locals and tourism. Numerous ideas and opinions were shared and, in the end, three social innovation propositions were further developed. Young people’s propositions and the context in which they emerge are briefly presented below.

Group A identified the lack of information as a need that requires solutions that would benefit both the locals and tourists. During the discussions, the participants often mentioned that one of the biggest issues is the lack of information about what is happening in the city.

All this information – those who work for the city and those who are interested know about that. But we who just live here are not that connected, we know nothing.

—

To everything I suggested, someone said ‘Isn’t there already something like that?’ We just don’t know about it.

Young people stated that the information channels used by the city and tourism operators do not necessarily reach different age groups like young people. For instance, youths criticised that most of the advertising is done through platforms such as a local newspaper or Facebook, which they nor the visitors necessarily use or follow. On the other hand, they stated that more traditional notice boards might be important for elderly people, for instance. Moreover, a small tourism information centre that exists in Kemi did not seem to respond to the needs expressed by the participants. Group A went on to suggest an idea for a social innovation proposition: a platform where it is easy to find information about local events, services, opening hours, maps, and so on.

The group suggested that enhancing the flow of information within the city, whether via a more traditional tourist information centre, notice board, a smartphone app, or a combination of these, could be of use for tourists and local people alike. (.)

Continuing the discussions about their everyday lives and experiences in Kemi, some of the participants described Kemi as a great place to live and work whereas others were more sceptical. Young people pointed out that the lack of activities and events does not inspire staying in Kemi. The participants stated that there are not enough places for young people to hang out or for meeting friends in the evenings. One participant pointed out that finding friends besides at school or work can be difficult without such places. Moreover, it was stated that staying in public places is often restricted and young people do not feel like they are welcome there.

There is no place for young people to hang out, they are always told to go away.

—

That’s the situation in Kemi, now that we don’t have such a place, it’s like every time you go somewhere, you upset someone.

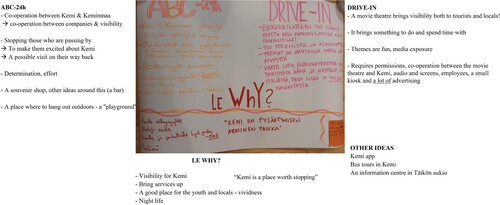

Group B identified the interrelated needs to provide more leisure time activities for both locals and tourists and to create spaces to hang out. They co-created two social innovation propositions to tackle these needs ().

First, the group came up with the idea of a drive-in theatre to boost the liveliness of the city centre and provide activities for locals and tourists.

Isn’t it, like, this drive-in represents developing the city?

—

Participant: ‘What good would the idea bring?’

Participant: Something to do. – Spending time together. You see a drive-in, the price would be like 5 euros, well that’s not bad, shall we go to check it out?

When asking more about the proposition, it appeared that opening a petrol station as such was not necessarily the main point of the proposition. Young people said that a meeting place with services for visitors and locals is needed.

It is not that they just pass by, but rather that (Kemi) is the destination. Something like that needs to be made. But at the same time, it could benefit locals’ lives. We do basically the same stuff as travelers would like to do. It would benefit everyone.

Participant: Could we add to this ABC (the petrol station) something like a living room or something where one could play board games and stuff?

Participant: Well this was another idea, that young people don’t have places where they are permitted to hang out. If it was a café, they could also hang out there.

Propositions as developing tourism towards and with the inside

As can be seen from the developed social innovation propositions, young people came up with ideas that they considered enhancing both tourists’ interests and local communities’ wellbeing through developing tourism-related activities and ways to inform about the activities. This is central, since also previous research on established tourism destinations has pointed out how tourism can contribute to increasing the availability of not only economic but also social and cultural opportunities available for young people (Duncan et al., Citation2020; Möller, Citation2016).

As the developed social innovation propositions demonstrate, young people’s propositions can contribute to developing locally grounded tourism that better fits local people’s hopes and needs in a place that is simultaneously a tourism destination and their home. Here, drawing on Nogués-Pedregal et al. (Citation2017), tourism should be developed towards the inside of the community rather than towards the outside. Towards the outside refers to planning tourism to please customers, which can result in tourism products that can feel distant or unconvincing for local people. The previously collected data from city employees and tourism actors in Kemi has also brought up that tourism development has been rather distant for citizens. The provided services, especially the main attractions and tourist sites, are not directed for local people (Partanen, Citation2022; Partanen & Sarkki, Citation2021). The young people’s insights are in line with these findings, and avoiding tourism branding towards the outside appeared important to the young workshop participants, too.

So that it [tourism] is not stereotypical, rather it is really brought up that hey, this is Sea-Lapland.

Maybe, if one wants to make the city livelier, they could start by making sure that the locals are happy and like it. Then, tourists are automatically taken into consideration. – And if you make developments to benefit everyone, this city will grow.

—

So that it (tourism) would be something special of Kemi. To kind of make Kemi a place that people like to visit. So that it is not only for passing-by but that Kemi is the destination. It should be made that way. At the same time, it would benefit locals’ lives. Like, we do basically the same things as the tourists would like to do. So it would be only good for everyone.

As the social innovation propositions for creating liveliness, activities, and places to hang out and for attracting passing-by visitors demonstrate, there is a need for, on the one hand, more diverse tourism services and, on the other, more inclusive tourism. This links to the idea of developing tourism with the inside by acknowledging more diverse perspectives and for the inside via creating services that better fulfil the needs of the local population (see Nogués-Pedregal et al., Citation2017). For instance, it was noted that cultural tourism activities are needed especially because the current emphasis lies on nature tourism.

Then, you kind of miss the whole city and the people there.

Young people often brought to the fore the need to diversify the image of Kemi with respect to tourism, and this appeared to be an underlying idea in several discussions and suggestions for change. The participants quite unanimously agreed that Kemi could take better advantage of alternative, locally-oriented ideas, which can be seen as a hope to make Kemi an interesting destination by enhancing tourism towards the inside by creating ‘something that is special for Kemi’. In this regard, it was brought up that city officials have their own ideas about the branding of Kemi that might differ from local people’s perceptions.

It could be that the decision-makers in Kemi have their own view of Kemi as a brand but the residents have a different view of Kemi and how it should be branded. And if those don’t match, then everything the city tries to do is seen by us as like, ‘Yeah right, something like this again.’

Young people’s propositions towards the inside can be seen to link with potential yet marginal new types of tourism mentioned in a tourism development plan drawn up by the city of Kemi (Pakarinen, Citation2022). In the plan, tourism is linked with degrowth through concepts such as ‘Nearcation, Staycation, Workation, Bleasure’ (Pakarinen, Citation2022, p. 6). These types of tourism can be seen to open up a discussion about locals as tourists. Hoogendoorn and Hammett (Citation2021) state that approaches like proximity tourism and resident tourism widen the definition of a tourist as someone who travels distances to visit a place. Such approaches acknowledge the varying roles local people can have in their places and how they can become tourists or visitors in social or psychological terms. These modes of tourism have emerged especially after the COVID-19 pandemic when travelling far has been restricted. The concepts at the masterplan can be seen to link with this kind of resident tourism (similarly as the propositions by young people) that could eventually strengthen tourism towards the inside, if realised.

Overall, young people’s discussions bring to the fore that if there is a mismatch between the experienced Kemi and the marketed Kemi, approval of tourism might be hard to achieve. The participants stated that some local people may even undervalue or oppose the official campaigns and development plans if they do not think they fit with their experience of Kemi. This can be interpreted as criticism for tourism towards the outside. Indeed, as one participant concluded, accepting and embracing what Kemi is could make it a more interesting site for tourists and also enhance local residents’ contentment, sense of belonging to their place of residence and encourage taking part in development.

Taking the propositions into action: pathways and barriers for young people’s participation and inclusion in tourism

When we moved on to discuss young people’s role in tourism development and how the propositions could be taken into action, young people considered that being a tourism industry insider would be the most probable way to participate although young people’s social innovation propositions were not explicitly linked to their own employment in tourism. As the young people reflected on their possibilities for taking their transformative ideas into reality, one possible pathway was to find employment in the field of tourism, and some workshop participants were in fact studying tourism in the local vocational school. Also, the interviewed city representatives often emphasised the potential of tourism as an employment opportunity for the youth (Partanen & Sarkki, Citation2021). This highlights the role of tourism employment as a pathway of making a change in local communities through one’s personal livelihood (also Kulusjärvi, Citation2017).

The young people did not consider working in tourism in Kemi especially interesting; young people stated that Kemi appears as ‘a probable option for employment but not appealing at all.’ The experts interviewed before the workshop also expressed the worry over youth unemployment in the region. They pointed out that Kemi has suffered from outmigration due to lack of employment and education possibilities. Moreover, although tourism has been expected to bring new jobs for example in creative industries, simultaneously, city employees working with employment issues stated that young adults cannot find a job in tourism despite several applications. For example, one expert noted that the requirements for employees seem sometimes surprisingly hard or even unrealistic to fill. At the same time, some interviewed representatives of the tourism industry noted that they cannot find skilled workforce in Kemi. Also at the policy level, the lack of workforce with suitable skills and training is often considered as one of the key aspects that hinders tourism development (see e.g. Booyens, Citation2020), also in Lapland (Elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskus, Citation2022).

On one hand, young people’s insights regarding their own participation in tourism are especially interesting because in peripheral areas, tourism is often considered as an important regional development strategy with the idea that tourism would provide employment opportunities in the region (e.g. Saarinen, Citation2003), attracting young people to stay or move to these regions. Hence, it is important to discuss how tourism work could become more inclusive for those interested in or currently working in the sector, for instance by evaluating what kind of opportunities are provided for (local) young adults seeking employment and how their skills and knowledge could diversify and supplement the industry. On the other hand, young people’s insights also highlight the difficulty of taking part in tourism planning as an outsider of the private or public sectors.

Simultaneously, young people’s insights also exemplify that imagining something new is often linked to pre-existing systems of traditional power and traditional actors in tourism planning. Indeed, realising social innovations often requires support from the public and private sectors in order for them to sustain (Ilie & During, Citation2012). Imagining how to take the propositions forward to realisation seemed challenging for the young people in this study. Mostly, young people were uncertain of funding issues and the fluency of regional and local co-operation among tourism developers and city officials; they also wondered how bureaucratic the process would be and what kind of permits would be needed. Notions such as ‘that idea would never pass’ or ‘that is too expensive’ reflected doubts of actualising the propositions. It was, for instance, stated that even though there are pressing needs as well as plenty of ideas for developing the city and tourism, actualising them ‘is a whole different story’ for young adults especially.

Like, we tried to think today at some point how we could make a difference. It always comes down to the fact that we can give ideas to companies and also the municipality of Kemi. But then, even if you give ideas to the municipality, it is always the one with power who makes the decisions. We cannot do anything but give ideas.

Participant: If you want to suggest something, you go to the Facebook groups. You go there to complain or to share something. Then people might start to talk. But at least I don’t know where to suggest something if I had an idea.

Participant: Yeah, I’ve no clue either.

Participant: It’s also that not everyone wants to make suggestions publicly. It would be better to have a private way to make suggestions.

Here the atmosphere is a bit like, ‘We could try out something new!’; ‘It’s not going to succeed. It will go bankrupt eventually.’ That way of thinking needs to be changed.

These notions demonstrate that the general atmosphere of how new and possibly transformative ideas proposed by young people are welcomed and discussed can itself work as an exclusive or inclusive force. Although the workshop participants had ideas and opinions, they expressed that they did not to possess the required knowledge or skills to enact change in their local community. It was suggested that it usually requires a certain kind of an active, determined, patient, and stubborn citizen to take the lead and start organising things. Furthermore, Jungsberg et al. (Citation2020, p. 276) distinguish the phases of initiating and implementing community-driven social innovations. Whereas community members, civil society organisations, and the local public sector are often central at the initiating phase, civil society organisations, play a key role in implementation. Initiating and sustaining community-driven projects requires ‘the capacity of local actors to develop ideas, to find resources and to manage decision-making.’

Yet, as Jungsberg et al. (Citation2020) note, it might not be desirable for single community members to be solely responsible of taking new propositions forward and pushing them towards realisation if multi-scalar networks could support creating local social innovations. Hence, finding a balance between local initiatives and internal or external expertise and resources is important. For instance, external funding bodies and local experts working with young people can work as potential supporters in bringing propositions into reality. Furthermore, providing safe spaces (such as the Ohjaamo space in Kemi) for locals to express their views regarding fair decision-making and planning of tourism (Rastegar & Ruhanen, Citation2021) could improve the general atmosphere of suggesting and developing new propositions outside the traditional structures and spaces for decision-making.

Discussion and conclusions

This article analysed community approaches in tourism with an aim to widen the understanding and involvement of the local population beyond the usual stakeholders in tourism development. This was processed by focusing on the opinions and perceptions of local young people, whose role in tourism planning and development has often been marginalised. Nevertheless, youth and tourism are often co-dependent in terms of employment, questions in workforce, citizenship, and needs for free-time activities, for instance (see e.g. Duncan et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2019), as this article has also demonstrated. As Duncan et al. (Citation2020) point out, tourism may contribute to providing amenities and social atmosphere that make the area more desirable for young people to stay or in-migrate. Hence, for them, tourism development can play a key role in future possibilities in terms of employment as well as everyday life.

Furthermore, young people should not be regarded solely in terms of their position as future workers (also Horton et al., Citation2013). At the workshop, young people were encouraged to bring to the fore their perspectives, opinions, and hopes regarding local tourism development. Moreover, arranging the workshop itself represented a way to challenge the power relations by discussing tourism in an alternative space, which has not been typically used for tourism planning. Whereas young people’s role as potential workers in tourism can be highlighted in regional development plans, for instance, young people themselves brought to the fore a more diverse range of ways in which tourism intersects with the local community. Considering young people’s perspectives would therefore enable the developing of both the tourism industry and Kemi as a simultaneous place of tourist destination and a place of residence.

Young adults’ social innovation propositions manifested in practice as different communication channels for providing information about activities and as a petrol station and a drive-in movie theatre. The propositions are aimed at enhancing the flow of information in the city, bringing more activities and liveliness, creating spaces to hang out, and attracting passing-by visitors to stop in Kemi. The propositions reflect desired transformations towards better recognition of young adults’ inclusion in tourism planning, creating more inclusive services for locals, and enhancing more diverse, locally grounded, and socially valuable tourism. These can be interpreted as links to the idea of widening the understanding of community approaches in tourism development, both in terms of who to include in planning and how to do and manage tourism. This, again, contributes to the questions of enhancing sustainability through tourism but also with respect to responding to unsustainable conditions created by tourism.

The finding that young people suggested mainly market-linked solutions demonstrates that combining market logic and social needs can in certain circumstances be perceived as a realistic way to provide local vitality through tourism. For instance, petrol stations – which are dependent on visitors’ mobilities – are often important places for locals for socialising and hanging out in sparsely habited regions and smaller towns (also Stammler et al., Citation2022). Even though young people’s propositions involved industry-oriented characteristics, the participants emphasised the social values that the transformative propositions would bring and the social needs the propositions would address. Indeed, combining market logic and social needs has been noted as one way to create social innovations (Mirvis et al., Citation2016). In this respect, the participants discussed the wider need to transform the tourism industry to make it locally more relevant and, thus, socially innovative. This resonates well with the idea of transformative tourism, which aims to provide visitors ‘a feel for the visited place, but also forms a deep sense of identification with the place and experiences oneself as belonging to this place’ (Reisinger, Citation2013, p. 30). As such, transformative tourism calls for acknowledging the local perspectives, views, and place identities in tourism planning, products, and activities (see Higgins-Desbiolles & Monga, Citation2021; Reisinger, Citation2015; Soulard et al., Citation2019).

Young adults’ social innovation propositions and their notions about developing tourism in Kemi by relying on locally unique and relevant characteristics can be considered to follow the logic of towards the inside tourism (Nogués-Pedregal et al., Citation2017). The fact that the workshop participants found developing and diversifying tourism as a way to develop the city for community members follows the approach. Furthermore, this kind of transformative tourism could be reframed as regenerative tourism that, according to Bellato et al. (Citation2022, p. 1) positions ‘tourism activities as interventions that develop the capacities of places, communities and their guests to operate in harmony with interconnected social-ecological systems.’

Whereas local views and perspectives are highly important for socially innovative and sustainable, regenerative tourism, the workshop participants brought up the barriers to the realisation of their propositions. The young people considered that their possibilities to act without sufficient funding, knowledge, and power in the decision-making system is limited. This, as well as the market-linked nature of the propositions, underlines the power relations and the role of the public and private sectors in developing tourism. The identified obstacles can be considered as an embodiment of exclusive tourism development, which leaves certain community members outside the planning processes (Wearing and Darcy, Citation2011). Then, locals are outsiders to tourism development despite their insider status as local person.

Furthermore, locals are much more than hosts, and places are more than destinations. Higgins-Desbiolles and Bigby (Citation2022) call for widening the understanding of the local beyond the host perspective, which sees places as destinations instead of social and ecological contexts of living. In ideal situations, tourism is grounded in local contexts in order to foster sustainability. As mentioned, the findings of this article demonstrate that when the viewpoint is switched through, for instance, socially innovative openings, tourism holds the potential in bringing versatile, novel value for local communities. Nevertheless, as Higgins-Desbiolles and Monga (Citation2021) note, a lot of potential in resident tourism is wasted because often, locals are not seen as people using tourism services.

Overall, tourism development that takes into account the local tourism potential can be seen as a way to enhance sustainability. For this purpose, the findings of this article underline the need for development both with the inside and for the inside (also Nogués-Pedregal et al., Citation2017). Understanding the nuances of community approaches in tourism is crucial for finding ways to develop and plan tourism with diverse groups of locals as well as creating social value through activities for diverse groups of locals. In this way, tourism can act as a socially inclusive force. Going beyond tourism towards the outside could also bring value for tourism business operators. Hearing diverse views on tourism development can help in diversifying products, services, and experiences. Yet, providing safe spaces (Rastegar & Ruhanen, Citation2021) for expressing such views is required.

Finally, the article argues that as social innovations emphasise creating not only economic value for local communities, they can also be seen as a way to contribute to discussing the sustainability of tourism through enhancing towards the inside logic. Furthermore, actualised social innovations can be regarded as concrete drivers of change. Yet, the sustainability of actualised social innovations needs to be evaluated case by case. For instance, from a holistic sustainability perspective, the current study has focused on social sustainability, and further research would be needed on the environmental sustainability of social innovations. Interestingly, the social innovation propositions of local young adults mostly focused on domestic or local tourism and travel by land, which opens up interesting questions for future research on the role of environmental sustainability in such propositions of younger generations.

At a general level, social innovations, which are based on understanding the social needs for change and emphasising collaborative bottom-up perspectives, can help in making visible the power relations in planning tourism and challenging the traditions of community-based tourism. Hence, social innovations hold the potential in revealing transformative ideas and agencies on the sustainability of tourism development. Therefore, social innovations can be used as a tool for imagining alternative ways of conducting tourism. The very processes through which social innovations are co-created can enlighten the different ways and phases of making change and help in identifying possible obstacles. Importantly, examining the perspectives of those with less power can reveal both exclusions and inclusions in tourism planning and development. In this respect, locally informed social innovation processes can create change towards sustainability and socially inclusive local development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mari Partanen

Mari Partanen is a Doctoral Researcher at the Geography Research Unit, University of Oulu, Finland, and a researcher at the School of Business, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, Finland. She is a tourism geographer and a cultural anthropologist whose research interests include sustainability, social innovations, inclusion, places in change, and ethnographic research.

Marika Kettunen

Marika Kettunen is a Doctoral Researcher at the Geography Research Unit, University of Oulu, Finland. Her research revolves around the geographies of young people, education, and citizenship formation.

Jarkko Saarinen

Jarkko Saarinen is a Professor of Human Geography at the University of Oulu, Finland, and Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He also serves as Visiting Professor at the Uppsala University, Sweden. His research interests include tourism and development, sustainability, adaptation and resilience, tourism-community relations, and nature conservation. He is currently Editor for Tourism Geographies and Associate Editor for Journal of Ecotourism and Annals of Tourism Research.

Notes

1 The workshop was arranged by the first and second author in October 2020 when the COVID-19 situation was considered good in Kemi. The restrictions at the Ohjaamo space allowed meetings for max. 15 people. After careful consideration with the city employees, it was decided to arrange the workshop face to face.

References

- Ateljevic, I., Harris, C., Wilson, E., & Collins, F. L. (2005). Getting ‘entangled’: Reflexivity and the ‘critical turn’ in tourism studies. Tourism Recreation Research, 30(2), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2005.11081469

- Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Nygaard, C. A. (2022). Regenerative tourism: A conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tourism Geographies, 25(4), 1026–1046. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2022.204437

- Bianchi, R. V. (2009). The ‘critical turn’ in tourism studies: A radical critique. Tourism Geographies, 11(4), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903262653

- Blackstock, K. (2005). A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal, 40(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsi005

- Booyens, I. (2020). Education and skills in tourism: Implications for youth employment in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 37(5), 825–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2020.1725447

- Booyens, I., & Rogerson, C. M. (2016). Tourism innovation in the global south: Evidence from the western cape, South Africa. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(5), 515–524. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2071

- Burns, P. (1999). Paradoxes in planning tourism elitism or brutalism? Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00099-1

- Canosa, A., & Graham, A. (2016). Ethical tourism research involving children. Annals of Tourism Research, 61(15), 1–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.07.00

- Canosa, A., Graham, A., & Wilson, E. (2018). Growing up in a tourist destination: Negotiating space, identity and belonging. Children's Geographies, 16(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2017.1334115

- Canosa, A., Moyle, B. D., & Wray, M. (2016). Can anybody hear me? A critical analysis of young residents’ voices in tourism studies. Tourism Analysis, 21(2–3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354216X14559233985097

- Canosa, A., Wilson, E., & Graham, A. (2017). Empowering young people through participatory film: A postmethodological approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(8), 894–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1179270

- Chhabra, D. (2021). Transformative perspectives of tourism: Dialogical perceptiveness. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(8), 759–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1986197

- Dolezal, C., & Novelli, M. (2020). Power in community-based tourism: Empowerment and partnership in bali. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(10), 2352–2370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1838527

- Duncan, T., Thulemark, M., & Möller, P. (2020). Tourism, seasonality and the attraction of youth. In L. Lundmark, D. B. Carson, & M. Eimermann (Eds.), Dipping in to the north (pp. 373–393). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskus. (2022). Lapin osaavan työvoiman saatavuuden toimenpidesuunnitelma. Tausta-aineisto. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://www.ely-keskus.fi/-/osaavan-ty%C3%B6voiman-saatavuuden-toimenpidesuunnitelma-vastaa-ty%C3%B6voimahaasteisiin-lappi-.

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK. (2019). The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland. Publications of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK, 3/201: Helsinki.

- Giampiccoli, A., & Saayman, M. (2014). A conceptualisation of alternative forms of tourism in relation to community development. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(27), 1667–1667. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p1667

- Gössling, S., Ring, A., Dwyer, L., Andersson, A. C., & Hall, C. M. (2016). Optimizing or maximizing growth? A challenge for sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(4), 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1085869

- Gunn, W., Otto, T., & Smith, R. C. (2013). Design anthropology: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- Hall, C. M. (2010). Changing paradigms and global change: From sustainable to steady-state tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(2), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081629

- Han, H., Eom, T., Al-Ansi, A., Ryu, H. B., & Kim, W. (2019). Community-based tourism as a sustainable direction in destination development: An empirical examination of visitor behaviors. Sustainability, 11(10), 2864. 1–14. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/10/2864?type=check_update&version=2

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Bigby, B. C. (2022). A local turn in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research, 92(C), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103291

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Monga, M. (2021). Transformative change through events business: A feminist ethic of care analysis of building the purpose economy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11-12), 1989–2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1856857

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Hammett, D. (2021). Resident tourists and the local ‘other’. Tourism Geographies, 23(5–6), 1021–1039. 9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1713882

- Horton, J., Hadfield-Hill, S., Christensen, P., & Kraftl, P. (2013). Children, young people and sustainability: Introduction to special issue. Local Environment, 18(3), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.760766

- Hörnström, L., Perjo, L., Johnsen, I. H., & Karlsdóttir, A. (2015). Adapting to, or mitigating demographic change? National Policies Addressing Demographic Challenges in the Nordic Countries. Nordregio Working paper.

- Ilie, E. G., & During, R. (2012). An analysis of social innovation discourses in Europe – concepts and strategies of social innovation. Report, Wageningen University and Research. Retrieved September 14, 2021, from https://edepot.wur.nl/197565.

- Jourdan, D., & Wertin, J. (2020). Intergenerational rights to a sustainable future: Insights for climate justice and tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(8), 1245–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1732992

- Jungsberg, L., Copus, A., Herslund, L. B., Nilsson, K., Perjo, L., Randall, L., & Berlina, A. (2020). Key actors in community-driven social innovation in rural areas in the nordic countries. Journal of Rural Studies, 79, 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.08.004

- Kamuf, V., & Weck, S. (2021). Having a voice and a place: Local youth driving urban development in an east German town under transformation. European Planning Studies, 30(5), 935–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1928055

- Kettunen, D. (2021). We need to make our voices heard: Claiming space for young people's everyday environmental politics in Northern Finland. Nordia Geographical Publications, 49(5), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.30671/nordia.98115

- Kindon, S. (2021). Participatory action research: Collaboration and empowerment. In I. Hay, & M. Cope (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (pp. 307–329). Oxford University Press.

- Knight, D. W., & Cottrell, S. P. (2016). Evaluating tourism-linked empowerment in cuzco, Peru. Annals of Tourism Research, 56, 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.007

- Koščak, M., Knežević, M., Binder, D., Pelaez-Verdet, A., Işik, C., Mićić, V., Borisavljević, K., & Šegota, T. (2021). Exploring the neglected voices of children in sustainable tourism development: A comparative study in six European tourist destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 561–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1898623

- Kulusjärvi, O. (2017). Sustainable destination development in northern peripheries: A focus on alternative tourism paths. The Journal of Rural and Community Development, 12(2/3), 41–58.

- Lapin luotsi. (2023). Matkailun aluetalousselvitys - Kemi-Tornion seutukunta [Tourism regional economic report - Kemi-Tornio region]. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://lapinluotsi.fi/elinkeinojen-nakymia/elinkeinot/lapin-matkailun-kumulatiivinen-aluetalousselvitys/matkailun-aluetalousselvitys-kemi-tornion-seutukunta/.

- Mayaka, M., Croy, W. G., & Cox, J. W. (2019). A dimensional approach to community-based tourism: Recognising and differentiating form and context. Annals of Tourism Research, 74, 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.002

- Mirvis, P., Herrera, M. E. B., Googins, B., & Albareda, L. (2016). Corporate social innovation: How firms learn to innovate for the greater good. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5014–5021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.073

- Mosedale, J., & Voll, F. (2017). Social innovations in tourism: Social practices contributing to social development. In P. J. Sheldon, & R. Daniele (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship and tourism: Philosophy and practice (pp. 1–13). Springer.

- Möller, P. (2016). Young adults’ perceptions of and affective bonds to a rural tourism community. Fennia, 194(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.11143/4630

- Mumford, M. D. (2002). Social innovation: Ten cases from benjamin franklin. Creativity Research Journal, 14(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1402_11

- Mumford, M. D., & Moertl, P. (2003). Cases of social innovation: Lessons from two innovations in the 20th century. Creativity Research Journal, 15(2-3), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ152&3_16

- Murphy, P. (1985). Tourism: A community approach. London.

- Neumeier, S. (2012). Why do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural development research? – proposal for a stronger focus on social innovations in rural development research. Sociologia Ruralis, 52(1), 48–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2011.00553.x

- Nogués-Pedregal, A. M., Travé-Molero, R., & Carmona-Zubiri, D. (2017). Thinking against "empty shells" in tourism development projects. Etnološka Tribina, 47(40), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.15378/1848-9540.2017.40.02

- Ohjaamo. (2023). What is Ohjaamo? Retrieved January 23, 2021, from https://ohjaamot.fi/en/mika-on-ohjaamo.

- Okazaki, E. (2008). A community-based tourism model: Its conception and Use. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(5), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159594

- Pakarinen. (2022). Master plan Kemi 2030 – TP1. Matkailun ja palveluiden elpymissuunnitelma, Nykytila-analyysi ja Mahdollisuuksien tunnistaminen [Tourism and services recovery plan, current state analysis and Identifying opportunities]. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.kemi.fi/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/MasterPlan-TP1-10022022.pdf.

- Partanen, M., & Sarkki, S. (2021). Social innovations and sustainability of tourism: Insights from public sector in Kemi, Finland. Tourist Studies, 21(4), 550–571.

- Partanen, M. (2022). Social innovations for resilience — local tourism actor perspectives in Kemi, Finland. Tourism Planning & Development, 19(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.2001037

- Rastegar, R., & Ruhanen, L. (2021). A safe space for local knowledge sharing in sustainable tourism: An organisational justice perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1929261.

- Refstie, H. (2018). Action research in critical scholarship: Negotiating multiple imperatives. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 17(1), 201–227.

- Reisinger, Y. (2013). Connection between travel, tourism and transformation. In Y. Reisinger (Ed.), Transformational tourism: Tourist perspectives (pp. 27–32). CABI.

- Reisinger, Y. (2015). Transformational tourism: Host perspectives. CABI.

- Robinson, R. N., Baum, T., Golubovskaya, M., Solnet, D. J., & Callan, V. (2019). Applying endosymbiosis theory: Tourism and its young workers. Annals of Tourism Research, 78, 102751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102751

- Rus, K. A., Dezsi, Ș, Ciascai, O. R., & Pop, F. (2022). Calibrating evolution of transformative tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 14(17), 11027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711027

- Saarinen, J. (2003). The regional economics of tourism in northern Finland: The socio-economic implications of recent tourism development and future possibilities for regional development. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 3(2), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250310001927

- Saarinen, J. (2017). Enclavic tourism spaces: Territorialization and bordering in tourism destination development and planning. Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1258433

- Saarinen, J. (2019). Communities and sustainable tourism development: Community impacts and local benefit creation tourism. In S. F. McCool, & K. Bosak (Eds.), A research agenda for sustainable tourism (pp. 206–222). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Saarinen, J. (2020). Tourism and sustainable development goals: Research on sustainable tourism geographies. In J. Saarinen (Ed.), Tourism and sustainable development goals: Research on sustainable tourism geographies (pp. 1–10). Routledge.

- Saarinen, J. (2021). Is being responsible sustainable in tourism? Connections and critical differences. Sustainability, 13(12), 6599. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126599

- Seraphin, H., Yallop, A. C., Seyfi, S., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Responsible tourism: The ‘why’ and ‘how’ of empowering children. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1819109

- Soini, K., & Birkeland, I. (2014). Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 51, 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.12.001

- Soulard, J., McGehee, N. G., & Stern, M. (2019). Transformative tourism organizations and glocalization. Annals of Tourism Research, 76, 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.03.007

- Stammler, F., Adams, R.-A., & Ivanova, A. (2022). Rewiring remote urban futures? Youth well-being in northern industry towns. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2081493

- Statistics Service Rudolf. (2023). Nights spent and arrivals by tourism season and country of residence, 1996–2022. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://visitfinland.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/VisitFinland/VisitFinland__Majoitustilastot/visitfinland_matk_pxt_116u.px/.

- Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J. J. M., & Tummers, L. G. (2015). A systematic review of Co-creation and Co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1333–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.930505

- Wearing, S., & Darcy, S. (2011). Inclusiveness of the ‘othered’ in tourism. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 3(2), 55–71. doi:10.5130/ccs.v3i2.1585