ABSTRACT

Amidst the captivating realm of the coffee shop experience, this study contributes to its significance across various literature streams and diverse forms. More specifically, the study focuses on the concept of the ‘ideal coffee shop experience’ from the perspectives of consumers and coffee shop owners/managers in Vietnam, drawing upon the experience economy and experience co-creation literature. The investigation takes place in Vietnam, a country renowned for its coffee exports and thriving coffee shop industry. Through qualitative data collected via interviews and an online questionnaire, the study uncovers divergent preferences between the supply and demand sides regarding the coffee shop's physical environment, product quality and variety, service staff performance/traits, and location or parking availability. Building on these findings, the study proposes the ‘supplier and consumer coffee shop experience’ model, which offers a comprehensive understanding of coffee shop experiences and provides valuable insights for practitioners and researchers in the relevant fields.

Introduction

Experiences, the coffee product, and coffee-related leisure activities

Experiences are at the heart of various industries, including hospitality and tourism (Mody et al., Citation2017). The conceptualisation of an experience encompasses an ongoing, personal, and subjective response to an event, setting, or activity outside an individual’s usual environment (Packer & Ballantyne, Citation2016). An experience is also referred to as encountering a reality, where a subject learns about such reality ‘doing the experience’ and is trained in the reality, or ‘having the experience’ (Carù & Cova, Citation2007).

These conceptualisations fit within hospitality and tourism settings and associated experiences, specifically within this study’s central theme. Being one of the world’s most consumed drinks (Setiyorini et al., Citation2023) and offered in hospitality environments (Jolliffe, Citation2010), the coffee product encompasses many experiential elements that lend themselves to enhancing coffee’s appeal, contributing to its wider consumption and enjoyment. Apart from its lifestyle-related significance in supporting social activities (Priatmoko & Lóránt, Citation2021), tactile, auditory, or visual aspects related to the environment where coffee is consumed can significantly influence drinking or tasting (Spence & Carvalho, Citation2020).

The coffee product and the venue where it is consumed combine to create a captivating appeal to expand into tourism. Indeed, coffee has experienced an evolving journey with gains along the way in quality through roasting, brewing, sourcing innovations, and the coffee shop experience (Morland, Citation2017). Moreover, a ‘third wave’ of coffee shops, also known as ‘specialty coffee’ (Morland, Citation2017), has emerged in the twenty-first century together with ‘allies’ such as coffee roasters and equipment providers (Manzo, Citation2014; Morland, Citation2017). Specialty coffee is grounded on the principles of organisational values and how business is conducted, including a focus on traceable supply, roasting style, expert brewing among trained baristas, and communication of coffee’s story, for instance, through tasting notes, menu boards, or service (Morland, Citation2017). Indeed, the service element is crucial in delivering the captivating appeal of coffee and coffee establishments and has implications for the development of tourism offerings and themes. As Rashid et al. (Citation2021) learned among coffee shop patrons, the service encounter has close links with experiential value and customer loyalty.

As the world’s second-largest coffee producer and exporter by volume (Statista, Citation2023a, Citation2023b), Vietnam has the potential to become an iconic coffee tourism (CT) and coffee shop tourism (CST) destination. Both intangible and tangible elements, such as an existing strong coffee culture or the uniqueness of the local coffee (Vu et al., Citation2022) and the links between gastronomy and coffee (Vu et al., Citation2023), strengthen such potential. As research conducted in different coffee-producing nations suggests (e.g. Bowen, Citation2021; Chen et al., Citation2021), a movement is growing towards the development of tourism products around the coffee industry, including coffee shops. In addition, the highest per capita coffee consumers in the world are from countries that do not produce coffee (Statista, Citation2020). Thus, there are important implications for the development of tourism-related activities in those nations where coffee is produced. Yet, as in other coffee-producing countries (e.g. Degarege & Lovelock, Citation2021), Vietnam’s position as a leading coffee producer has not been maximised.

CT has been defined as a type of commodity tourism, affording visitors’ involvement in experiential aspects of coffee, where this product relates to a place’s culture and nature (Wang et al., Citation2019). Moreover, CT provides a platform to consume the coffee product, culture, tradition, and history of a coffee-producing destination (Jolliffe & Bui, Citation2006). Whether the coffee shop is located in a coffee region or an urban area, CST can revolve around these aspects while additionally emphasising attributes of the venue where the coffee experience occurs, including its setting (infrastructure), ambience/vibe, and décor.

Extant research gaps

Existing research highlights the potential and benefits of CT and CST (e.g. Anbalagan & Lovelock, Citation2014; Chen et al., Citation2021). At the same time, both lines of inquiry present knowledge and research gaps. First, and most importantly, there is a dearth of conceptual development regarding CT and CST experiences that could contribute to a more rigorous understanding from the demand or supply sides. These extant weak links between the two groups prevent them from identifying whether or not they perceive the highlights and key attributes of such experiences similarly or differently. Identifying similarities or differences will inform providers of coffee experiences of factors that render these experiences more fulfilling.

Second, and similarly, the links between the impact of memorable CT experiences on the behaviour of travellers remain under-researched (Chen et al., Citation2021). Here again, coffee consumption and education could provide practical insights to product/service providers.

Third, few empirical investigations have focused on brand equity from the perspective of coffee shops operating in emerging markets (Bui et al., Citation2017). Thus, extending empirical and conceptual knowledge on experiential aspects of coffee consumption could have significant impacts and spill over the further development of CT and CST, where CT (Setiyorini et al., Citation2023) and CST are in their initial developmental stages.

The study’s objectives

This exploratory research extends practical and conceptual knowledge in various ways. Firstly, by examining the following overarching research questions (RQs), the study will develop a deeper understanding of the coffee shop experience from the supply and demand sides. Moreover, the questions are verbalised as follows:

RQ1) How is the ‘ideal coffee shop experience’ in Vietnam defined by:

The demand side of the experience (consumers)?

The supply side of the experience (owners/managers)?

RQ2) How similar/different is the perceived ideal coffee shop experience within the context of Vietnam?

Between consumers and owners/managers?

Within consumer group members (e.g. genders, age groups)?

Apart from addressing extant research gaps, the findings will guide coffee shop operations in maintaining or improving the consistency of the consumption experience. Thus, there are direct and indirect implications for the future development of CT and CST, particularly in coffee-producing nations, where the readily available raw product, added value, and existing coffee shop infrastructure could cater to the palate and interests of coffee consumers. High-quality firm-consumer interactions in co-creating distinctive experiences can add value for both parties while unlocking new forms of competitive advantage for firms (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). Similarly, enhancing coffee shop customers’ experiential interactions can also improve a coffee shop’s brand prestige (Choi et al., Citation2017).

Secondly, by embracing key underpinnings associated with the experience economy (e.g. Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998, Citation2011), and the co-creation of experiences (e.g. Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004) and through the data analysis, the study will afford more conceptual understanding. This understanding will be more specifically reflected through the development of a conceptual framework.

Literature review

Experience and the experience economy

The consumer and visitor experience literature has grown exponentially, from the seminal work of leading authors (e.g. Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998, Citation1999) to subsequent contributions (e.g. Carvalho et al., Citation2023; Pine & Gilmore, Citation2011; Sfandla & Björk, Citation2013). The context of visitor experiences, as outlined by Packer and Ballantyne (Citation2016), possesses four defining characteristics. First, they are subjective and unique to each individual. Second, these experiences are subject to external influences like settings, events, or activities and are susceptible to individual interpretation. Thirdly, they are time- and space-limited, occurring either at specific times or over some time. Finally, visitor experiences have significance, resulting in noticeable impacts that distinguish them from everyday life. These impacts can range from positive to negative and can vary in intensity (Packer & Ballantyne, Citation2016). Therefore, ‘getting it right’ or maintaining consistency and high standards can go a long way.

An additional conceptual underpinning is the experience economy, proposed by Pine and Gilmore (Citation1998, Citation1999), which highlights the role of consumer experiences in driving economic growth. The ‘experience realms’ model highlights different experiences:

Absorption refers to capturing individuals’ attention and drawing the experience into their minds from a distance; it involves creating a compelling and engaging encounter that occupies their thoughts (Pine & Gilmore, Citation2011). Conversely, immersion entails individuals becoming an integral part of the experience, physically or virtually (Pine & Gilmore, Citation2011). This immersion can occur in tourism, where visitors absorb educational and entertaining offerings related to a destination while immersing themselves in the setting, resulting in escapist or aesthetic experiences (Oh et al., Citation2007).

Escapism represents a deeper level of immersion, involving complete immersion in activities that allow individuals to escape their ordinary lives. This immersive phenomenon can be seen in the desire to travel to exotic cultures or settings, seeking novel experiences and a break from routine (Pine & Gilmore, Citation2011; Wei et al., Citation2023). On the other hand, aesthetic experiences emphasise significant immersion with limited impact on the immediate activity or environment. Curiosity and a desire for knowledge and entertainment are the driving forces behind participants in aesthetic experiences (Wei et al., Citation2023).

Active participation, another dimension of the experience realms model, highlights the role of customers or guests in shaping and co-creating the experience (Pine & Gilmore, Citation1999). Here, participants are able to influence an event or performance, fostering a deeper immersion and engagement (Baron & Warnaby, Citation2011; Pine & Gilmore, Citation1999). This active involvement extends to the tourism domain, where tourists actively take responsibility for every step of the experience, enhancing their sense of immersion and satisfaction (Mathis et al., Citation2016). In coffee shop settings, active participation through interactions with service providers and fellow customers has positively affected happiness (Silanoi et al., Citation2022).

In contrast, in passive experiences, there is less intensity and more distance between the audience and the performer (Carù & Cova, Citation2007); as a result, the audience cannot significantly influence or affect the performance (Pine & Gilmore, Citation1999). In the field of tourism, passive involvement can take the form of interactions that are usually controlled by the setting; nevertheless, as in the case of visiting a theme park, opportunities exist for tourists to provide some level of input to their overall experience (Mathis et al., Citation2016).

According to Williams (Citation2006), a significant proportion of tourism activities are aesthetic, and although tourists immerse themselves in the experiences, their participation in them is negligible. Coffee shop experiences lean towards passive encounters. For instance, although baristas play an essential role in co-creating memorable and positive coffee shop experiences through coffee products, customers remain passive recipients (Kwame Opoku et al., Citation2023).

While potentially useful to provide insights into the coffee shop experience, the notions of Pine and Gilmore (e.g. Citation1998) have yet to be fully embraced in this emerging literature. Moreover, Branco and Kobakova (Citation2018) are among the few authors to incorporate the model within the coffee shop experience based on data from 40 consumers. Their findings suggest alignments with the four realms, with noticeable overlaps. For instance, music was categorised under the entertainment, educational, and aesthetic realms; additionally, socialisation is associated with both entertainment and education and comfort with education and aesthetics (Branco & Kobakova, Citation2018). Nevertheless, the research by Branco and Kobakova (Citation2018) was carried out in a non-producing coffee nation (Spain), at two well-established international coffee shop brands, and from the perspective of 40 consumers.

Therefore, investigating these dimensions from the perspectives of other coffee shop stakeholders, including patrons and owners/managers of both chain and independent coffee shops, could provide new and valuable practical and conceptual insights.

Co-creation of experiences

The co-creation concept predicates the joint creation of value by customers and companies (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). In the service domain, co-creation is perceived as a process that incorporates the actions of service providers, consumers, and potentially other actors (Grönroos & Voima, Citation2013). Part of the literature’s emphasis concerns the control firms exert in value creation, with the customer joining as a co-creator (Grönroos & Voima, Citation2013). Furthermore, and as suggested by its conceptualisation, the co-creation process entails a number of critical steps, including those presented by Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004):

The co-construction of service experiences and personalised experiences by customers to suit their context,

Jointly defining and solving problems,

Engaging in continuous dialogue,

Experiencing variety,

Experiencing the business in real time.

Scholars have embraced the conceptual value of the co-creation framework to examine coffee consumption experiences (e.g. Shulga et al., Citation2021; Yen et al., Citation2020). Silanoi et al. (Citation2022) integrated this literature to examine specialty coffee consumers’ positive experiences shared through social media platforms. Silanoi et al.’s (Citation2022) findings ascertain the importance of active participation with service providers and other consumers, where the perceived benefits from co-creating customer experiences motivate their engagement. Jeon et al. (Citation2016) examined the application and co-creation of background music in coffee shop environments, thereby unveiling key benefits for coffee shop operators. Indeed, by facilitating opportunities for coffee shop patrons to be involved in background music co-creation, operators could entice customers to stay longer and incur more expenditures (Jeon et al., Citation2016).

Research on festival evaluation by Zhang et al. (Citation2019) illuminates conceptual aspects related to the co-creation of experiences. Zhang et al.’s (Citation2019) analysis included the presentation of a framework illustrating the links between co-creating experiences with festival performers and other festival attendees, resulting in satisfaction levels in co-creating experiences, with implications for festival satisfaction and revisit intentions. Buhalis and Sinarta (Citation2019) explored social media usage by hospitality and tourism brands to enhance real-time consumers’ experiences. Their findings highlighted the importance of real-time service in helping co-create value and contributed to a real-time service ecosystem framework, underscoring critical implications for the supply and demand sides. Moreover, because firm-consumer interactions occur in real time, this type of big data can be utilised to add value and increase the firms’ brand competitiveness (Buhalis & Sinarta, Citation2019).

The experience economy and co-creation of services literature provide useful angles to delve into consumption experiences in different domains. Nevertheless, to date, no major study on coffee shop consumption has firmly considered these notions to afford a deeper understanding of what patrons and operators in Vietnam perceive as an ideal experience. Moreover, to the authors’ knowledge, studies examining these two key groups simultaneously within environments of leading coffee-growing/producing nations have yet to be conducted. In line with the extant literature utilising these conceptual frameworks, this study will adopt the above insights to examine the ideal coffee shop experience from the supply and demand sides of coffee shops in Vietnam.

Methodology

Methods and approaches

This study will contribute to a deeper understanding of how two key hospitality industry stakeholders, coffee shop operators and consumers, perceive the ideal coffee shop experience within Vietnam’s context, with important practical and conceptual implications. Given the dearth of research investigating and contrasting both groups, together with the study’s focus on a global and growing phenomenon (coffee consumption), an exploratory approach is chosen. Exploratory research entails the search for new meaning, knowledge, insights, and understanding; it views the world in ways that align with those of participants (Brink & Wood, Citation1998).

The nature of the research also influenced the type of data to be gathered. Sofaer (Citation1999) posits that qualitative methods afford rich accounts of complex phenomena and help illuminate the interpretation and experience of events by actors. Qualitative methods are also valuable in ‘moving toward explanations’ (Sofaer, Citation1999, p. 1101) and in carrying out initial investigations to develop theory while ‘giving voice to those whose views are rarely heard’ (p. 1101). Thus, collecting qualitative data was perceived as a more fulfilling option, especially given the goal to address and deepen the insights regarding relatively unexplored coffee shop research from both sides (supply and demand).

To further fulfil the study’s objectives, a decision was made to collect data from coffee shop operators and consumers. Regarding the first group, the availability of hundreds of coffee shops in large Vietnamese cities provided abundant opportunities to gather qualitative data; whenever applicable, on-site visits complemented this effort. In addition, coffee shop website information helped complement the collected data. Concerning consumers, in addition to a wealth of coffee shop houses, the availability of social media pages (e.g. Zalo) with a food and beverage thematic background, together with restaurant associations, coffee fan websites, and gastronomy blogs highlighted numerous avenues for consumer data collection. A convenience sample of both consumers and coffee shop operators was therefore used. In the case of the latter group, purposeful sampling (Patton, Citation2015) was perceived appropriate, provided the potential participants fulfilled several essential criteria, which included:

Having at least three years of experience in their industry,

Working in an existing business (the coffee shop was still operating) at the time of the study,

Performing an ownership/managerial role,

Managing full-time staff.

An inductive approach was also selected in this study, where, through data interpretations, themes, concepts, or a model can be derived (Thomas, Citation2006). Interviews were planned with potential participants from the supply side; the value of this preliminary project was perceived to serve as a foundation to collect initial thoughts and continue by exploring the consumer side at a later stage.

The questionnaires

The questionnaires for the coffee shop operators and consumers were each divided into two sections, with the first eliciting basic information from participants (both groups) and their businesses (owners/managers); illustrates this breakdown and key demographic characteristics. Similarly, the second section sought to elicit extended comments from participants concerning their perceived ideal coffee shop experience in Vietnam. In the process of developing the questionnaire, samples of the extant literature on coffee shops and other leisure-related experiences were considered (e.g. Bui et al., Citation2017; Carvalho & Spence, Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2021; Jeon et al., Citation2016; Mathis et al., Citation2016; Mody et al., Citation2017; Spence & Carvalho, Citation2020). This open-ended question asked both operators and consumers:

How would you define the ideal coffee shop experience?

The question aimed at exploring experiences specific to Vietnam was posed to operators during the interviews. Additionally, when the question was directed at coffee shop patrons, it included additional phrasing focused on consumer needs/wants:

How would you define the ideal coffee shop experience regarding:

Intrinsic aspects associated with consumer needs/wants?

Extrinsic aspects associated with consumer needs/wants?

Table 1. Main characteristics of coffee shop consumers, owners/managers, and their businesses.

While semi-structured interviews were conducted with the coffee shop operators, the online questionnaire was designed for coffee consumers including comment boxes for the open-ended question. Participants were encouraged to provide extended comments, including anecdotes and perceptions of tangible/intangible elements of coffee shops. These comments allowed for analysis to identify similarities and differences between the two groups or within consumers (e.g. based on gender or age group). The questionnaires were presented in Vietnamese and followed collaborative and iterative translation principles. They were administered to both mono/bilingual individuals who provided feedback concerning clarity and comprehension (Douglas & Craig, Citation2007).

Data collection

Once university ethics was granted, a first round of data collection was completed among coffee shop operators between June and October of 2021, with 100 coffee shop addresses being identified through desk research (e.g. businesses’ websites). Vietnam’s capital and second-most populated city, which is also home to thousands of coffee shops, was a preferred key location for this study. A total of 60 Hanoi coffee shops were targeted followed by 30 in Ho Chi Minh and 10 in other smaller cities. Electronic messages to the attention of the owner/manager were sent to these establishments before June 2021. The message described the study’s goals and formally asked recipients to participate in the research through face-to-face and/or online interviews. Given existing anti-COVID-19 regulations, the semi-structured interviews among coffee shop operators were split into 25 on-site, face-to-face, and 22 online. Thus, 47 interviews with coffee shops were conducted.

The protocol designed to collect data from consumers differed significantly. In this case, potential respondents were recruited through invitations sent to social media outlets and 45 coffee shops that showcased a community on their social media and/or websites. The data collection among coffee shop consumers took place between May and July of 2022; during this time, 1211 responses were gathered. Thirty-three responses were incomplete and deemed unusable; hence, 1178 valid responses were gathered from consumers.

Data analysis

The qualitative data gathered through the interviews and online questionnaire were first transcribed and translated into English by members of the research team, where, again, the involvement of mono/bilingual individuals was valuable. Conducting qualitative content analysis (e.g. Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) helped identify patterns, themes, and categories through the coding of raw data. While different forms of coding exist, in line with Locke et al. (Citation2022), this study mainly engaged ‘with the data directly as a source of ideas and labels to make codes’ (p. 266) and positioned ‘patterns together across the data’ (p. 266). In this process, the study adheres to coding procedures discussed by Auerbach and Silverstein (Citation2003). These principles relate to the focus on relevant text, the emergence of repeating ideas, organising these ideas into themes, organising themes into theoretical constructs, and finally, developing a theoretical narrative (Auerbach & Silverstein, Citation2003).

An iterative process was undertaken, where researchers repeatedly revisited the data (Kekeya, Citation2016), allowing thoroughness throughout the analysis. Several members of the research team were involved in the data coding. This strategy enabled the further refinement and consistency of the analysis; overall, only minor differences in interpretation were revealed between the researchers’ analyses. In addition, the study aligns with O’Connor and Joffe (Citation2020) in that numerous research teams conduct comparisons of members’ perceptions of the qualitative data. However, these comparisons do not include quantifying individual team members’ level of consensus (O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020).

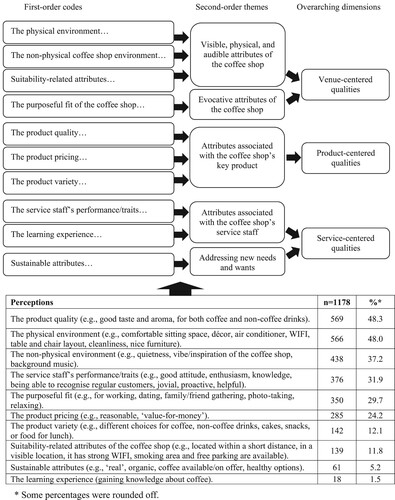

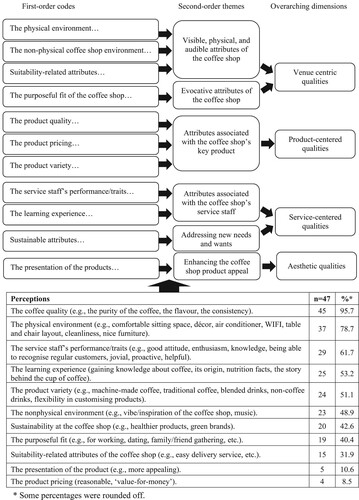

Associated with the coding protocols Auerbach and Silverstein (Citation2003) prescribed, the use of a data structure template (Gioia et al., Citation2012) assisted in distilling conceptual dimensions that led to the development of this study’s proposed framework. For instance, the data structure analysis begins with first-order data analysis, which is based on informants’ voices, or ‘informant-centric’ (Gioia, Citation2021). This step is followed by a second-order analysis, referred to as ‘theory centric’ (Gioia, Citation2021) or ‘researcher-centric’ (Gioia et al., Citation2012). This second step is part of the theoretical realm of the research, where the concepts or themes help explain or describe phenomena (Gioia et al., Citation2012) and extend into aggregate dimensions. As and illustrate, the data structure provides a roadmap illustrating the progression between raw data, themes, terms, and dimensions, as well as their relationship (Gioia, Citation2021).

Trustworthiness in qualitative research

Ensuing from many disciplines and paradigms, qualitative research embraces a variety of standards of quality, also called trustworthiness, which is associated with credibility, validity, and rigour (Morrow, Citation2005). The work of Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985), together with earlier contributions (Guba, Citation1981; Guba & Lincoln, Citation1981), identify four conventional terms, complemented by a fifth in subsequent research (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1994); these are presented as alternatives to address trustworthiness issues:

Credibility underscores the importance of activities that will result in credible findings (Treharne & Riggs, Citation2014). In this study, investigator, data, and environmental triangulation were used to enhance the study’s credibility and add to the elaboration and richer understanding of the phenomenon under inquiry (Amin et al., Citation2020). In addition, and as Shenton (Citation2004) suggested, the study adopts well-established research methods.

Transferability underlines the event that the findings can be applicable to other contexts (Treharne & Riggs, Citation2014). Transferability is, therefore, challenging to document (Shenton, Citation2004), including in the present exploratory study, which has yet to be replicated in other contexts. Nevertheless, harmony between those evaluating the research and the findings could contribute to these appearing ‘transferable in the eyes of the reader’ (Treharne & Riggs, Citation2014).

Dependability refers to the potential for the findings to be generated if another research team undertook the study (Treharne & Riggs, Citation2014). One way to address dependability is to report a study’s processes in detail to enable researchers to repeat the study in the future (Shenton, Citation2004), which is followed in the present research.

Confirmability stresses the importance of steps to ensure that a study’s results are based upon the participants’ ideas and experiences and not the investigator’s biases (preferences, characteristics) (Shenton, Citation2004). Being transparent in reporting a study’s findings enhances the potential to evaluate its confirmability (Treharne & Riggs, Citation2014). This aspect is demonstrated in the following sections (e.g. and ). In addition, the study provides numerous participants’ verbatim comments that emphasise their views and perceptions as opposed to the researcher’s subjective points of view (e.g. Shenton, Citation2004).

Authenticity underscores the representativeness of a wide range of viewpoints on a topic (Treharne & Riggs, Citation2014), fairness in such representativeness, and rendering the different inquiry procedures transparent (Amin et al., Citation2020). Both the representativeness and transparency of the study’s procedures were addressed in the present research, for instance, through the participation of actors from the coffee shop supply and demand sides, including different groups (gender- and age-wise).

Demographic information: participants and firms

As illustrated (), balanced gender participation was achieved among coffee shop consumers. Just over half of these participants were between 18–25 years old, and almost 60 percent were employed full-time. A similar percentage indicated patronising coffee shops less than and more than six times per month, respectively, whereas almost two-thirds usually visited independently-owned establishments and typically (81.5%) consumed one coffee drink only. The largest group of participants (54.1%) patronised coffee shops in Hanoi.

Concerning coffee shop operators, more than two-thirds have worked for six or more years in the hospitality industry, and 70.2 percent were owners or co-founders at the time of the study. Almost half of the operations employ 10 or fewer full-time staff. Finally, the majority of consumers’ visited chain-owned establishments; these were predominantly located in the city of Hanoi.

Results

The ideal coffee shop experience in Vietnam from the demand- and supply-side actors

points to 10 key experiential factors coffee shop patrons are associated with; furthermore, two factors are most prevalent, accounting for almost half of the participants. The product quality (48.3%), which encompasses the coffee’s aroma and taste, as well as other beverages’ quality, was the most frequently indicated factor, followed by the physical environment of the coffee shop (48%). As selected consumer comments demonstrate:

Consumer82: The coffee product quality is high; other beverage options are at least of average quality.

Consumer738: … when the drinks are of high quality, suitable to your own taste …

Consumer781: Good coffee, properly prepared.

Consumer1114: High-quality coffee and other products.

Consumer3: Delicious drinks, variety, affordable prices, nice view …

Consumer71: Quality drinks, proper practices, and quality service staff.

Consumer83: Sipping a cup of coffee while running a deadline in a peaceful space.

Consumer99: Good product quality, variety, and eye-catching decoration space.

Consumer116: Quiet space, friendly staff, and skilled bartenders.

Consumer681: Friendly staff, affordable prices suitable to many audiences.

Consumer713: Service quality and the space of the coffee shop.

Consumer1159: The coffee shop’s peaceful, spacious, relaxed ambience.

Differences were revealed when contrasting the perceptions of owners/managers gathered during the interviews to those of the consumer side. In fact, shows that while similar factors underscore participants’ preferred attributes related to their ideal coffee shop experience, differences exist in how they prioritise or order these attributes.

emphasises the differences between the two groups regarding elements associated with the ideal coffee shop experience in Vietnam ( and ). For example, a higher percentage (95.7%) of owners/managers than consumers (48.3%) selected product quality. Various comments underscore the significant emphasis placed upon this attribute:

Supplier27: The customer experience at the coffee shops has to be well-rounded. How baristas tell the story or explain about coffee and whether they feel satisfied…The service quality could be more important, [and should] include responses to customers' complaints/ unhappiness with a drink…

Supplier41: Coffee quality is the main point. Nowadays, people not only care about the flavour but also the source, [and] the pureness of coffee. Coffee nowadays is becoming the favourite and daily consumed beverage in Vietnam … consumers have higher requirements for the origin or flavour of coffee.

Supplier30: Coffee quality is important. However, what also significantly contributes to their experience is the store’s ambience and quality of service.

Supplier36: Customers will always have different ‘values’ depending on their needs. Some people come to the café because it is close to home, because of the lovely staff, the décor, or for personal reasons (recall memories). For coffee shop owners, it is also necessary to integrate all these values to give customers the best experience.

Table 2. The ideal coffee shop experience from the supply and demand sides.

Differences within the consumer cohort

Numerous differences were also noticed within the consumer contingent. First, comparisons between the first eight attributes participants chose () yielded two statistically significant differences under Pearson Chi-Square tests. A higher percentage of female patrons (51.9%) selected product quality and variety than did male patrons (45%) (). Second, differences also emerged among different age groups. Here, the 26–35-year-old group selected the physical environment, the non-physical environment, the product pricing, the product variety, and the coffee shop’s suitability notably more than other age groups.

Table 3. The ideal coffee shop experience – Inter-group differences (1).

Further analysis indicates that the group aged below 26 years (25.1%) indicated consuming more coffee drinks than the group aged between 26–35 years (13.7%) and that aged 36 years and above (7.6%); this difference was statistically significant (p < .001). In contrast, the group aged 36 years and above (65%) indicated patronising coffee shops at a much higher level (p < .001) than the group aged between 26–35 (51.8%) and the one aged below 26 years (33.3%).

Third, the student group () indicated the coffee shop’s product quality, variety, and physical environment, whereas the group representing part-time employees selected the product pricing more highly; these differences were also statistically significant. Fourth, coffee shop visitation frequency also influenced how consumers perceived their ideal experience. Indeed, as the revealed statistically significant differences highlight (), those indicating less visitation (less than six times per month) indicated product quality, pricing, and variety more highly.

Table 4. The ideal coffee shop experience – Inter-group differences (2).

A similar outcome was perceived when comparing coffee consumption levels and experiential attributes. Those patrons consuming an average of one coffee drink per visit selected more highly the product quality, the physical and non-physical environment, the purposeful fit of the coffee shop, and suitability-related aspects. In contrast, those indicating higher coffee consumption also selected the product pricing more highly. These findings suggest that consumers who exhibit higher patronage and higher consumption place fewer demands upon key coffee shop experiential attributes. Finally, differences within these two attributes were noticed when comparing patrons of chain versus independently-owned coffee shops, with members of the first group selecting the product quality and variety more highly than their counterparts.

Discussion

The study contributes to the extant literature in various ways. First and foremost, by juxtaposing two key stakeholder groups, the study affords an alternative way to learn about the coffee shop experience in the context of Vietnam. To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first of its kind in bringing these two groups to the forefront of the coffee shop experience, especially in a leading coffee producer where a dynamic coffee shop culture has evolved. Illuminating the ideal coffee shop experience among Vietnamese consumers and coffee shop owners/managers is particularly important to learn about this industry, which could become an additional drawing factor for domestic and international tourism in Vietnam. Moreover, learning more about such potential is particularly useful given the socioeconomic (e.g. Hung Anh et al., Citation2019; Nghiem et al., Citation2020;) and cultural importance (e.g. Grant, Citation2019; Vu et al., Citation2022) of coffee production and consumption in Vietnam, respectively.

Various fundamental priorities within each group were revealed by contrasting the supply and demand sides. Moreover, while the study demonstrates that similar attributes conform to the perceptions of consumers and suppliers of what the ideal coffee shop experience in Vietnam entails, there are also differences. For instance, the two groups’ priorities differ concerning non-physical attributes, the coffee shop’s purposeful fit to address patrons’ needs and wants, and product pricing. Consequently, there is a need for more robust alignments with consumers’ priorities, as doing so could directly address those identified priorities and enhance patrons’ experience. Ultimately, customers’ satisfaction is fundamental for businesses’ survival (Kau & Wan-Yiun Loh, Citation2006).

From a CT perspective, recent research has identified the need to educate and inform visitors about coffee traditions, culture, or heritage (Casalegno et al., Citation2020). In referring to the competitiveness of the restaurant industry, Cherro Osorio et al. (Citation2022) highlight the value of creating experiences based on the uniqueness of a culture’s traits as a differentiation tool. In the present research’s context, owners/managers rank gaining knowledge about coffee also as part of the ideal coffee shop experience in Vietnam. However, consumers only perceived this attribute as last on their list of priorities. A similar outcome was noticed regarding the presentation of the coffee shop’s products or sustainable product provision/demand. Thus, the study offers new insights to guide practitioners in developing an appealing CST and CT product and industry. The results could also be considered when developing these activities in other coffee-producing nations.

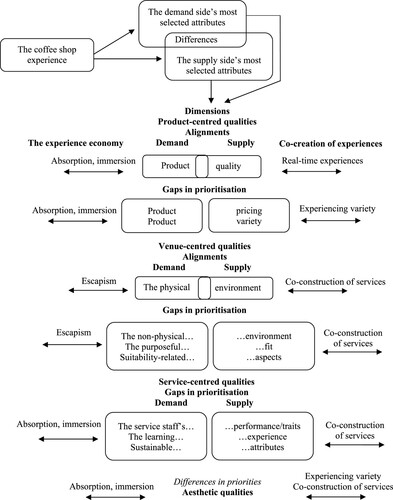

Conceptually, the study also contributes to new insights. Indeed, the second-order themes identified and the developed dimensions ( and ) afford a deeper understanding of how the supply and demand sides of coffee shops perceive the central or most valuable experiential pillars. Moreover, the two figures contribute to a sounder understanding of what the two groups prioritise, and the differences between the two, with three dimensions encompassing consumers’ perceptions and four among owners/managers. Within the second-order themes and dimensions, various relationships with the experience literature, and the underpinnings of the experience economy and co-creation of experiences are revealed.

First, the results align with various points made by Packer and Ballantyne (Citation2016). Indeed, the verbalisations of the RQs addressed in this research illuminate the personal and subjective nature of experiences, their interpretation, the fact that they are time or space-bound, and the significance that such experiences have for the visitor, in this case, the coffee shop patron. The differences concerning the selected attributes ( and ) further support the points raised by Packer and Ballantyne (Citation2016), thus suggesting the significance for hospitality or tourism operators to understand consumers’ behaviour more thoroughly.

Second, and in line with Pine and Gilmore (Citation1999), although the coffee shop experience entails limited influence of the audience (patrons) on the performance (the coffee shop experience), elements of absorption and immersion are present. For instance, consumers’ preferences for physical and non-physical attributes, the purposeful fit of the coffee shop, or suitability-related attributes not only occupy individuals’ attention but also become part of the experience (Pine & Gilmore, Citation2011).

Third, the results also align with the underpinnings of the co-creation of experiences (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). The mere fact that consumers engage with the supply side during the initial transaction (e.g. ordering beverages) suggests consumers’ influence in the experiential process. Additionally, by engaging with tangible or intangible features and encountering the quality of a product or service, individuals can have real-time experiences and encounter a variety of experiences. Finally, choosing a particular venue or place within the coffee shop also points to the importance of personalised experience and the potential for co-constructing these.

Theoretical implications

Following the rationale of an inductive approach (Thomas, Citation2006) and that of data structure development (Gioia et al., Citation2012), the study’s findings contributed to developing a conceptual model (). This model, which depicts various dimensions revealed through the data analysis, suggests various theoretical implications that have the potential to illuminate hospitality, tourism, and leisure-related consumption experiences. First, there are implications for understanding these experiences through the lens of product-centred qualities, where product quality is a common denominator for both the supply and demand sides of the coffee shop experience. Second, and similarly, this experience can be observed, interpreted, and understood through the venue-centred qualities dimension, which emphasises the role of the establishment’s physical environment.

Figure 3. The ideal coffee shop experience model. Sources: Pine and Gilmore (Citation1998, Citation1999, Citation2011); Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004).

Nevertheless, while conceptually these two dimensions have the explanatory power to illuminate the coffee shop experience, several gaps exist regarding how the two groups of coffee shop stakeholders perceive such experiences. Furthermore, a third dimension highlighting the role of the service side of the business helps understand what key attributes the two groups are prioritising. Finally, the coffee shop experience could also be understood through the aesthetic qualities dimension, which is only identified by the supply side in this study. Notwithstanding these scenarios, the model’s conceptual value resides in its flexibility to include the two critical cohorts of the coffee shop experience, enabling a deeper understanding of experiential elements that could guide researchers in their pursuits to uncover these in other coffee shop environments or extend the model to examine other offerings or hospitality settings (e.g. a-la-carte restaurants, bars, clubs, spas, and accommodation).

Another theoretical implication of the proposed model concerns its flexibility to be used in tandem with the underpinnings of other theoretical constructs. Here, various relationships emerge between the tenets of the experience economy and the co-creation of experience. Importantly, these relationships emanate from the point of view of two key stakeholder cohorts; moreover, while the relationships apply to consumers experiencing the coffee shop environment, they are developed from two perspectives. Moreover, by identifying these relationships () based on the two groups, the study extends the notions of these two conceptual underpinnings and contributes to a sounder understanding of experiential attributes.

The contributions of various authors (Dubin, Citation1978; Reay & Whetten, Citation2011; Whetten, Citation1989) provide guidance as to what constitutes a theoretical contribution. Reay and Whetten (Citation2011) posit that a ‘good’ theory should explain a phenomenon reliably. Several questions must, therefore, be answered, with the first focusing on the key factors that can explain a phenomenon of interest, and the second ascertaining how these factors relate to one another. A third question concerns ‘why’ the representation of a phenomenon merits ‘to be considered credible’ (Reay & Whetten, Citation2011, p. 107). The three prominent dimensions emerging from the analysis helped explain coffee shop consumers’ experiential attributes and the supply side’s perceptions. Despite the identified differences in prioritisation between the demand and supply groups, clear relationships exist between the different dimensions, as well as between their attributes (second-order themes) and participants’ views. In line with Reay and Whetten (Citation2011), the dimensions that contribute to explaining the phenomenon, together with their alignments with the underpinnings of the experience economy and co-creation of experiences, merit being deemed credible. Thus, together with the above-presented theoretical implications, the study also makes a theoretical contribution beyond developing dimensions from raw data.

Practical implications

The study’s findings also have implications for practitioners. One first implication concerns prioritising attributes between the consumer and supply sides. Here, for instance, aligning with consumers’ main needs or wants, including with regard to product quality and the physical environment, could provide consistency and enhance the coffee shop experience, with ramifications for the industry’s development into an international drawcard. Progressing through this process demands investments, for instance, in the establishment’s interior and exterior designs of work/meeting spaces, furniture, and training staff.

With the advent of new trends in the coffee world, including a growing interest among younger consumers (e.g. Islam et al., Citation2019) or that of specialty coffee (Urwin et al., Citation2019), adapting and keeping up with such developments could prove vital. Contact and on-site observations at different coffee shops also revealed that some businesses are actively diversifying their product base, even by importing other coffee flavours, roasting styles, or Arabica coffee. Similarly, observations around the cities of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh ascertain the strength of coffee shops’ appeal among international visitors. Thus, the consolidation of standards and diversity of products, together with the physical attributes of the coffee shop industry, could benefit the industry and different forms of tourism and leisure activities. While there is a need for educational institutions to provide graduates with the necessary skills (e.g. Eusébio et al., Citation2022), it is equally important for businesses to create and offer learning and practical work opportunities to develop talent.

Another practical implication refers to the consumer side. While consumers do not perceive the significance or value of the educational component within the coffee shop industry, the intention of owners/managers to prioritise this attribute could go hand-in-hand with enhancing the industry. Indeed, educating local residents interested in coffee flavours, aromas, mixtures, bi-products, roasting types, or heritage can raise awareness of Vietnam’s coffee industry nationally and internationally. This increased awareness could form a continuous process where consumers’ renewed expectations for higher standards, uniqueness, and diversity of coffee or other products demand constant innovation and upgrades from the supply side.

These developments could have important implications for future patronage and for drawing interested visitors by providing alternative leisure, hospitality, and tourism activities, including barista and coffee-food workshops, tours, or even travel to those regions where coffee is grown. While this last activity is also in place at various destinations, elevating the image of coffee shops’ experiential attributes could trigger further interest in delving into more intrinsic aspects of coffee production. Casalegno et al. (Citation2020) agree that a more profound knowledge of the coffee world contributes to higher tourism perceptions and coffee visits.

Additional aspects identified by owners/managers but not among consumers concern a) the presentation of beverages and/or foods at the coffee shop and b) the sustainable elements of the beverages/foods on sale, such as healthier options. Earlier research has uncovered the importance of the presentation of foods and their standards or quality (Nield et al., Citation2000).

Van Doorn et al. (Citation2015) have demonstrated that the artistic presentation of food, including coffee, influences consumers’ perception and willingness to pay for the product. Hence, while marginal in this study, the presentation attribute could be considered or tested progressively within the consumer experience. A similar argument can be made of the sustainable characteristics of the beverages/foods, including their organic or healthier nature. While promoting healthier product options can be challenging in restaurants (e.g. Economos et al., Citation2009), implementing this strategy could widen the scope and diversity of the product portfolio and the attractiveness of the establishment. Moreover, the success of various Vietnamese companies currently focusing on organic coffee or healthier beverage choices/options could inspire the coffee shop industry to offer these.

Conclusion

This study fulfilled various objectives, including the development of a conceptual understanding of experiential attributes within the coffee shop industry (). A unique feature of this study is the involvement of two key stakeholder groups: the demand and supply sides. Specifically, in considering the tenets of the experience economy (Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998) and co-creation of experiences (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004), the study examines how the demand and supply sides perceive the ideal coffee shop experience in Vietnam. In addition, the study investigates potential differences between these two groups and within the consumer cohort.

A survey conducted among 1178 consumers, coupled with 47 semi-structured interviews carried out among coffee shop owners/managers, provides essential insights, including a set of dimensions associated with the coffee shop experience. While both participating groups align regarding the central attributes within the coffee shop experience, their prioritisation differs significantly. Further analysis revealed variations in agreement among participants regarding the importance of these attributes. Additionally, the analysis identified several differences within the consumer group, highlighting inter-group variations. The study's findings illuminate various aspects, such as branding equity in coffee shops (Bui et al., Citation2017) and consumer behaviour, CST, and their implications for understanding consumer behaviour in coffee tourism (Chen et al., Citation2021).

Limitations and future research

The study has limitations that could be addressed in future research. Firstly, there is an imbalance between consumer and supply-side responses, highlighting the need for more input from coffee shop owners/managers to understand attributes comprehensively. Secondly, the study mainly focuses on data from Vietnam's largest cities, suggesting the potential for including diverse viewpoints from consumers and owners/managers in different cities. Thirdly, while the present research qualitatively uncovered important attributes associated with the coffee shop experience within the Vietnamese consumer context, adding a quantitative element could also be useful. For instance, consumers could be asked to assess their perceived relative importance of all highlighted attributes by presenting these together in a questionnaire tool.

Additionally, further research is needed to operationalise and assess the developed framework. Doing so could lead to a deeper understanding and potential expansion of dimensions and attributes relevant to the ideal coffee shop experience. These improvements in knowledge and understanding would enhance the development and offerings of CST and CT.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Oanh Thi Kim Vu

Oanh Thi Kim Vu, Ph.D. Lecturer. Research interests include tourism, hospitality, international business, entrepreneurship.

Abel Duarte Alonso

Abel Duarte Alonso, Ph.D. Research interests include international business, micro, small and medium enterprises, family enterprises, innovation, and community development.

Thanh Duc Tran

Thanh Duc Tran, MTM. Research interests include tourism, hospitality, community-based tourism, women entrepreneurs, and entrepreneurship.

Wil Martens

Wil Martens, Ph.D. Research interests include Resource efficiency, earning management, and intellectual capital.

Lan Do

Lan Do, PhD. Lecturer. Research interests include international business, strategic management, innovation, and sustainability.

Trung Thanh Nguyen

Trung Thanh Nguyen, MBA. Research interests include tourism, hospitality, community-based tourism, culture, and local entrepreneurship.

Erhan Atay

Erhan Atay, Ph.D. Research interests include international management, strategic management and global mobility.

Mohammadreza Akbari

Mohammadreza Akbari, DBA. Research Interests include supply chain, logistics, operations management, emerging technology, and sustainable development.

References

- Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16(10), 1472–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.005

- Anbalagan, K., & Lovelock, B. (2014). The potential for coffee tourism development in Rwanda–Neither black nor white. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1–2), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358414529579

- Auerbach, C. F., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data – An introduction to coding and analysis. New York University Press.

- Baron, S., & Warnaby, G. (2011). Value co-creation from the consumer perspective. In H. Demirkan, J. C. Spohrer, & V. Krishna (Eds.), Service systems implementation (pp. 199–210). Springer.

- Bowen, R. (2021). Cultivating coffee experiences in the Eje Cafetero, Colombia. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(3), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-08-2020-0184

- Branco, M., & Kobakova, D. (2018). Turning a commodity into an experience: The “sweetest spot” in the coffee shop. Innovative Marketing, 14(4), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.21511/im.14(4).2018.04

- Brink, P. J., & Wood, M. J. (1998). Advanced design in nursing research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Buhalis, D., & Sinarta, Y. (2019). Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 563–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1592059

- Bui, T. Q., Nguyen, H. V., & Pham, N. T. (2017). The effects of selected marketing mix elements on customer-based brand equity: The case of coffee chains in Vietnam. PRIMA: Practices and Research in Marketing, 8(1), 38–47.

- Carù, A., & Cova, B. (2007). Consuming experience. Routledge.

- Carvalho, F. M., & Spence, C. (2018). The shape of the cup influences aroma, taste, and hedonic judgements of specialty coffee. Food Quality and Preference, 68, 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.04.003

- Carvalho, M., Kastenholz, E., & Carneiro, M. J. (2023). Co-creative tourism experiences–a conceptual framework and its application to food and wine tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(5), 668–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1948719

- Casalegno, C., Candelo, E., Santoro, G., & Kitchen, P. (2020). The perception of tourism in coffee-producing equatorial countries: An empirical analysis. Psychology and Marketing, 37(1), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21291

- Chen, L. H., Wang, M. J. S., & Morrison, A. M. (2021). Extending the memorable tourism experience model: A study of coffee tourism in Vietnam. British Food Journal, 123(6), 2235–2257. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2020-0748

- Cherro Osorio, S., Frew, E., Lade, C., & Williams, K. M. (2022). Blending tradition and modernity: Gastronomic experiences in High Peruvian cuisine. Tourism Recreation Research, 47(3), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1940462

- Choi, Y. G., Ok, C. M., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Relationships between brand experiences, personality traits, prestige, relationship quality, and loyalty: An empirical analysis of coffeehouse brands. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(4), 1185–1202. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0601

- Dávid, L., Remenyik, B., & Adol, G. F. C. (2021). Geographic features and environmental consequences of coffee tourism and coffee consumption in Budapest. Acta Geographica Debrecina Landscape and Environment Series, 15(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.21120/LE/15/1/2

- Degarege, G. A., & Lovelock, B. (2021). Institutional barriers to coffee tourism development: Insights from Ethiopia–the birthplace of coffee. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(3), 428–442.

- Douglas, S. P., & Craig, C. S. (2007). Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation. Journal of International Marketing, 15(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.1.030

- Dubin, R. (1978). Theory building. Free Press.

- Economos, C. D., Folta, S. C., Goldberg, J., Hudson, D., Collins, J., Baker, Z., Lawson, E., & Nelson, M. A. (2009). Community-based restaurant initiative to increase availability of healthy menu options in Somerville, Massachusetts. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6(3), 1–8.

- Eusébio, C., Alves, J. P., Rosa, M. J., & Teixeira, L. (2022). Are higher education institutions preparing future tourism professionals for tourism for all? An overview from Portuguese higher education tourism programmes. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 31, 100395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2022.100395

- Gioia, D. (2021). A systematic methodology for doing qualitative research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320982715

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2012). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Grant, S. G. (2019). Café creatives – Coffee entrepreneurs in Việt Nam. Education about Asia, 24(2), 46–49.

- Grönroos, C., & Voima, P. (2013). Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0308-3

- Guba, E. G. (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology Journal, 29(2), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02766777

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1981). Effective evaluation. Jossey-Bass.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). SAGE Inc.

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hung Anh, N., Bokelmann, W., Thi Thuan, N., Thi Nga, D., & Van Minh, N. (2019). Smallholders’ preferences for different contract farming models: Empirical evidence from sustainable certified coffee production in Vietnam. Sustainability, 11(14), 3799–3825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143799

- Islam, T., Ahmed, I., Ali, G., & Ahmer, Z. (2019). Emerging trend of coffee cafe in Pakistan: Factors affecting revisit intention. British Food Journal, 121(9), 2132–2147. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2018-0805

- Jeon, S., Park, C., & Yi, Y. (2016). Co-creation of background music: A key to innovating coffee shop management. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 58, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.07.006

- Jolliffe, L. (2010). Common grounds of coffee and tourism. In L. Jolliffe (Ed.), Coffee culture, destination and tourism (pp. 3–20). Channel View Publications.

- Jolliffe, L., & Bui, T. H. (2006). Coffee and tourism in Vietnam: a niche tourism product? Paper presented at the Travel and Tourism Research Association – Canada, Chapter Conference, 15–17 October 2006, Montebello, Quebec, Canada.

- Kau, A. K., & Wan-Yiun Loh, E. (2006). The effects of service recovery on consumer satisfaction: A comparison between complainants and non-complainants. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040610657039

- Kekeya, J. (2016). Analysing qualitative data using an iterative process. Contemporary PNG Studies, 24(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2015.1038226

- Kim, K., Choi, H. J., & Hyun, S. S. (2020). Coffee house consumers’ value perception and its consequences: Multi-dimensional approach. Sustainability, 12(4), 1663–1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041663

- Kwame Opoku, E., Tham, A., Morrison, A. M., & Wang, M. J. S. (2023). An exploratory study of the experiencescape dimensions and customer revisit intentions for specialty urban coffee shops. British Food Journal, 125(5), 1613–1630. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2022-0361

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Inc.

- Locke, K., Feldman, M., & Golden-Biddle, K. (2022). Coding practices and iterativity: Beyond templates for analyzing qualitative data. Organizational Research Methods, 25(2), 262–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120948600

- Manzo, J. (2014). Machines, people, and social interaction in “third-wave” coffeehouses. Journal of Arts and Humanities, 3(8), 1–12.

- Mathis, E. F., Kim, H. L., Uysal, M., Sirgy, J. M., & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.023

- Mody, M. A., Suess, C., & Lehto, X. (2017). The accommodation experiencescape: A comparative assessment of hotels and Airbnb. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(9), 2377–2404. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0501

- Morland, L. (2017). Rounton Coffee and Bedford Street Coffee Shop: From rural coffee roaster to urban coffee shop. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 18(4), 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750317742325

- Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

- Nghiem, T., Kono, Y., & Leisz, S. J. (2020). Crop boom as a trigger of smallholder livelihood and land use transformations: The case of coffee production in the northern mountain region of Vietnam. Land, 9(2), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9020056

- Nield, K., Kozak, M., & LeGrys, G. (2000). The role of food service in tourist satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19(4), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4319(00)00037-2

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Oh, H., Fiore, A. M., & Jeoung, M. (2007). Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507304039

- Packer, J., & Ballantyne, R. (2016). Conceptualizing the visitor experience: A review of literature and development of a multifaceted model. Visitor Studies, 19(2), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2016.1144023

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97–105.

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre and every business a stage. Harvard Business Press.

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (2011). The experience economy – updated edition. Harvard Business Press.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

- Priatmoko, S., & Lóránt, D. (2021). A story of a cup of coffee review of Google local guide review. Atlantis Highlights in Social Sciences, Education and Humanities, 1, 50–55.

- Rashid, N., Nika, F. A., & Thomas, G. (2021). Impact of service encounter elements on experiential value and customer loyalty: An empirical investigation in the coffee shop context. Sage Open, 11(4), 21582440211061385. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211061385

- Reay, T., & Whetten, D. A. (2011). What constitutes a theoretical contribution in family business? Family Business Review, 24(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511406427

- Setiyorini, H., Chen, T., & Pryce, J. (2023). Seeing coffee tourism through the lens of coffee consumption: A critical review. European Journal of Tourism Research, 34, 3401–3401. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v34i.2799

- Sfandla, C., & Björk, P. (2013). Tourism experience network: Co-creation of experiences in interactive processes. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(5), 495–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1892

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

- Shulga, L. V., Busser, J. A., Bai, B., & Kim, H. (2021). The reciprocal role of trust in customer value co-creation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 45(4), 672–696. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020967068

- Silanoi, T., Meeprom, S., & Jaratmetakul, P. (2022). Consumer experience co-creation in speciality coffee through social media sharing: Its antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 14(4), 576–594. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-11-2021-0162

- Sofaer, S. (1999). Qualitative methods: What are they and why use them? Health Services Research, 34(5, Part 2), 1101–1118.

- Spence, C., & Carvalho, F. M. (2020). The coffee drinking experience: Product extrinsic (atmospheric) influences on taste and choice. Food Quality and Preference, 80, 103802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103802

- Statista. (2020). The countries most addicted to coffee. Available at: https://www.statista.com/chart/8602/top-coffee-drinking-nations/#:~:text=This%20year%2C%20people%20in%20the,hot%20brown%20in%20the%20world.

- Statista. (2023a). Coffee production worldwide in 2020, by leading country. Available at:https://www.statista.com/statistics/277137/world-coffee-production-by-leading-countries/.

- Statista. (2023b). Coffee export volumes worldwide in January 2022, by leading countries. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/268135/ranking-of-coffee-exporting-countries/.

- Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

- Treharne, G. J., & Riggs, D. W. (2014). Ensuring quality in qualitative research. In P. Rohleder & A. Lyons (Eds.), Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology (pp. 57–73). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Urwin, R., Kesa, H., & Joao, E. S. (2019). The rise of specialty coffee: An investigation into the consumers of specialty coffee in Gauteng. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(5), 1–17.

- Van Doorn, G., Colonna-Dashwood, M., Hudd-Baillie, R., & Spence, C. (2015). Latté art influences both the expected and rated value of milk-based coffee drinks. Journal of Sensory Studies, 30(4), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/joss.12159

- Vu, O. T. K., Duarte Alonso, A., Martens, W., Do, L., Tran, L. N., Tran, T. D., & Nguyen, T. T. (2023). Coffee and gastronomy: A potential ‘marriage’? The case of Vietnam. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(6), 1943–1965. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2022-0440

- Vu, O. T. K., Duarte Alonso, A., Martens, W., Ha, L. D. T., Tran, T. D., & Nguyen, T. T. (2022). Hospitality and tourism development through coffee shop experiences in a leading coffee-producing nation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 106, 103300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103300

- Wang, M. J., Chen, L. H., Su, P. A., & Morrison, A. M. (2019). The right brew? An analysis of the tourism experiences in rural Taiwan's coffee estates. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.02.009

- Wei, W., Baker, M. A., & Onder, I. (2023). All without leaving home: Building a conceptual model of virtual tourism experiences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(4), 1284–1303. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2021-1560

- Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.2307/258554

- Williams, A. (2006). Tourism and hospitality marketing: Fantasy, feeling and fun. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 18(6), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110610681520

- Yen, C. H., Teng, H. Y., & Tzeng, J. C. (2020). Innovativeness and customer value co-creation behaviors: Mediating role of customer engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102514

- Zhang, C. X., Fong, L. H. N., & Li, S. (2019). Co-creation experience and place attachment: Festival evaluation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.04.013