ABSTRACT

The accelerating climate crisis demands action by governments, sectors, organisations and individuals. This research aims to inform sectoral approaches, which catalyse decarbonisation within one particular part of the global economy, but whose success is shaped by country-specific contexts. To appraise each country’s enabling environment for climate change mitigation in the tourism sector, data are drawn from the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Development Index for 2019 and 2021. Focusing on three central areas of tourism mitigation, namely public transport, green energy, and nature protection, a Mitigation Context Index is created by averaging normalised (1–7 scale) scores across six variables. The results reveal that some countries provide favourable conditions for tourism emissions reduction, whilst others might impede mitigation progress. Understanding the opportunities or constraints of tourism’s mitigation context can guide policy priorities, target setting and investment decisions. Where tourism is a significant part of the national economy, there is an important opportunity for sectoral leadership. Tourism could help unlock green investment and nudge the country towards more ambitious climate action. Whilst more work is required to fully capture tourism’s mitigation context, this note intends to trigger integrated thinking on how to optimise sectorial contributions within evolving climate governance arrangements.

Introduction

The year 2023 was by far the hottest on record with 1.48 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures (Copernicus, Citation2024). Collaboration and collective commitment to climate action at all levels is more urgent than ever. International climate policy focuses on government leadership, for example through processes such as those reflected in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (Bernstein & Hoffmann, Citation2018). However, it is increasingly clear that more diverse governance arrangements are required to maximise stakeholder contributions (Harichandan et al., Citation2022) to achieve the commonly agreed goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions whilst adapting to current and future climate risks. This means that tailored initiatives that advance low carbon futures of particular industries or sectors need to complement higher order frameworks.

Sectoral decarbonisation – as opposed to that led by state actors – enables participants of a similar background to exchange knowledge on new climate technologies, innovative business models, measurement and benchmarks. It has been catalysed by global programmes such as the United Nations’ Race to Zero (with different alliances or groupings for sectors such as universities, banks, insurers, the fashion industry and so forth) (UN, Citation2023) and the Science Based Targets Initiative (e.g. to support the power sector, pulp and paper, aviation, rail and service buildings, etc.) (Schweitzer et al., Citation2023). The ‘net zero’ imperative (Allen et al., Citation2022) is now pursued by a wide range of sectors, including tourism. Leadership in mitigating sectorial climate impacts is crucial, but the ability to decarbonise remains interlinked with wider system parameters.

This research note contributes to both knowledge and practice by conceptualising ‘tourism mitigation context’ as a construct that deserves further attention in climate governance more widely. Determining whether the mitigation context is conducive for decarbonisation or inhibiting progress will help optimise sector-specific climate strategies and policies.

Background

Research found that non-government actors can play an important role in accelerating climate action through initiatives that ‘disrupt carbon lock-in’ (Bernstein & Hoffmann, Citation2018, p. 190). By trialling new approaches, challenging existing norms or institutions, building new capacity and coalitions, sectoral climate governance and action has the potential to catalyse new dynamics that extend beyond the initial ‘space of experimentation’ (Bernstein & Hoffmann, Citation2018). In an ideal scenario, climate actions undertaken by a sector and the national government are mutually reinforcing. Alternatively, there could be a policy conflict, or sector and state are in a leader-followership situation where one nudges the other towards more ambitious action towards low-carbon transformation (Weaver et al., Citation2022).

This research draws on the tourism sector as a case study where climate action was found to depend on complex governance arrangement (Becken & Loehr, Citation2022). Both tourism and climate in themselves are nested systems covering the global-local spectrum. The tourism sector has sought to advance decarbonisation at multiple levels; globally through initiatives such as the Glasgow Declaration on Climate Action in Tourism (One Planet, Citation2021), nationally through a range of climate-related policies (OECD, Citation2022), and at the sub-sector level through the provision of tools, training and advocacy (e.g. net positive path by the Sustainable Hospitality Alliance, Citation2023). The focus here, however, is on understanding the national mitigation context in which tourism stakeholders pursue their decarbonisation agendas. For example, hotels are key users of electricity; yet the resulting carbon footprint is determined by the carbon intensity of the national power sector or providers of local green electricity (Luo et al., Citation2023). Thus, whilst a hotel should focus on reducing energy consumption, the overall climate impact depends on the national energy system (unless the hotel becomes entirely self-sufficient through its own renewable energy installations).

Existing research on tourism’s carbon footprint (e.g. Lenzen et al., Citation2018) highlights that the single largest contributor is transport (49% of all emissions). Thus, shifting tourism from high-carbon modes (air and car transport) to lower-carbon public alternatives is an important mitigation strategy (Peeters et al., Citation2019). Second, activities related to food, lodging and other services contribute 24% of tourism emissions (Lenzen et al., Citation2018). To decarbonise these, the current and future extent of clean energy availability is critical (Harichandan et al., Citation2022). At present, over 84% of global primary energy supply are from fossil fuels, but this will have to shift towards renewable sources, namely clean electricity and biomass (IEA, Citation2021), and this transition is central to tourism mitigation. Third, and given tourism’s intricate relationship with nature (Becken & Kaur, Citation2021), national commitments to protect biodiversity and carbon sinks are linked to mitigation potential for tourism. Future residual emissions will have to be balanced by permanent sinks, of which ecosystems are part of (Allen et al., Citation2022) and to which tourism could potentially contribute financially.

The objective of this research is to introduce the construct of mitigation context and shed light on the particular situation for tourism in different countries. The analysis focuses on three key areas that are particularly relevant to the tourism sector, namely public transport, energy and nature protection. Moreover, the research will identify different political positions that the tourism sector can take to either reinforce, catalyse or nudge wider climate action in their country. Conceptually, the notion of tourism sectoral climate policy and action corresponds to the archetype of hybrid or network governance as identified by Hall (Citation2009) in his reflections on tourism policy implementation.

Method

The data for this research stem from the Travel & Tourism Development Index (TTDI) developed by the World Economic Forum (Citation2022) as a ‘strategic benchmarking tool for policymakers, companies and complementary sectors to advance the future development of the Travel and Tourism (T&T) sector’ (p. 4). It is noted here that the notions of tourism development or tourism as a development tool are contested and have changed over time (Jenkins, Citation2015). The TTDI includes 117 countries, covering 96% of global direct tourism Gross Domestic Product. Data compiled for the index represent a unique dataset that draws on a wide range of primary data, a global survey of tourism experts, and established methods for imputing missing data and normalising scales. While there were major disruptions to global tourism in 2020 and 2021, it is still useful to compare the two available datasets of 2019 and 2021 (for methodological details, see WEF, Citation2022, Appendices A, B). Earlier versions of the index exist, but significant changes were made between 2017 and 2019 when the focus shifted from competitiveness to development potential.

The TTDI is made up of 17 pillars with a total of 112 indicators; most of these focus on business aspects of tourism. To specifically capture the enabling environment for climate mitigation, it was necessary to extract a sub-set of indicators that directly connect to measures identified as being central to tourism mitigation (e.g. Becken, Citation2019; Gössling et al., Citation2023; OnePlanet, Citation2023). The recent stocktake by the Tourism Panel on Climate Change (TPCC, Citation2023) highlighted transport as the key contributor to tourism emissions. Rail was identified as the most effective mode for low carbon mobility. The TPCC report also emphasised the role of renewable electricity to decarbonise aviation, individual mobility, and tourist accommodation. Thus, indicators related to public transport and clean energy were selected for this research. In addition, and due to its relevance to both tourism and carbon removal (Becken et al., Citation2024; Gössling et al., Citation2023), indicators related to protected areas were included.

Each of the three areas (public transport, clean energy, protected areas) was represented through one continuous metric and one ordinal variable. The latter came in the form of a Likert score (1–7) derived from the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey. For the ordinal variable related to transport, three survey-based public transport questions were used to derive an average score (). Thus, a total of 8 original TTDI indicators were used to create six variables. This research uses similar terminology as the WEF (e.g. developing countries rather than countries of the Global South), acknowledging that deeper and more critical reflections of these concepts are beyond the scope of this article.

Table 1. Indicators extracted from the World Economic Forum’s TTDI (Citation2022).

The WEF (Citation2022) open access database provides values for the continuous variables but also converts these into (ordinal) scores (1–7) for the calculation of their TTDI. The normalisation and imputation for missing values methods provided by WEF were reviewed and deemed robust. Thus, the ordinal scores were used in this present research to derive an integrated Mitigation Context Index (MCI) for each country. This was achieved by calculating the average score of the six indicators shown in . A weighting procedure was not undertaken but could be explored in the future.

Finally, the newly created index was contrasted with the relative importance of tourism employment in each country to identify the economic and policy space within which the sector operates. Employment was selected over economic contribution (% of Gross Domestic Product) because the number of people involved in tourism is an important representation of ‘touch points’ for change.

Results

The Mitigation Context Index (MCI) reveals great variability across countries. Four out of the top five countries with the most favourable context are in Europe; the exception being Hong Kong with the second highest score. The lowest scoring country is Lebanon, followed by Yemen. All countries in the lowest five show some improvements between 2019 and 2021. The largest improvement in Mitigation Context Index was achieved by Jordan, followed by Panama, whereas the biggest reduction in favourable mitigation context was observed for Morocco and the United States of America (, see supplementary table for full list).

Table 2. Top and bottom five countries in terms of Mitigation Context Index and improvement/decline between 2021 and 2019.

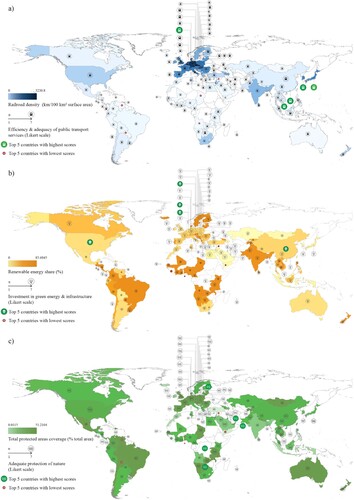

Some countries stand out for a favourable context on individual indicators ((a–c)). For example, in 2021 Singapore displayed the highest density of rail network per land area (32.3 km/100 km2), and efficiency and access to public transport are scored highly (6.3 out of 7). Other countries with public transport scores over six are Japan (6.6), Hong Kong SAR (6.6), Switzerland (6.5), Korea (6.3), and the Netherlands (6.1). The clean energy context is a more nuanced in that some of the high shares of renewable energy in developing countries are due to high reliance on solid biofuel (e.g. firewood), for example as seen in Zambia (85.1%) or Tanzania (83.7%). This contrasts with Iceland where the 78.2% of renewable energy is largely in the form of hydroelectricity. The highest survey scores for clean energy investment were found in the USA (6.0), Luxembourg (5.7), China (5.6), Netherlands (5.4), Finland (5.3) and Portugal (5.3). In terms of nature protection, the largest shares of protected area are found in Luxembourg (51.2%) and Hong Kong SAR (41.9%), both very small countries. Zambia (41.3%), the United Kingdom (40.3%) and Slovenia (40.0%) all have protected area shares over 40%. In terms of assessed quality of environmental and nature protection the highest scoring country in 2021 was Rwanda (6.0), followed by Qatar (6.0), Botswana (5.9) and the United Arab Emirates (5.8).

Figure 1. Maps of three tourism-relevant mitigation areas and six variables: (a) Railroad density and Efficiency and adequacy of public transport services, (b) Renewable energy share and investment in green energy; (c) Total protected areas and adequate protection of nature.

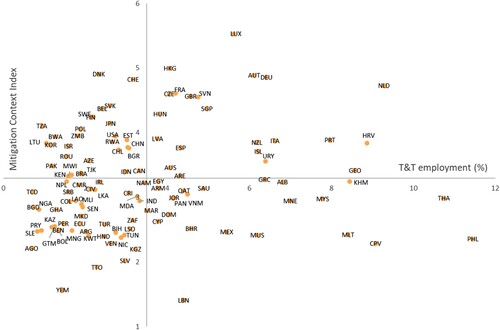

When combining the Mitigation Context Index with tourism employment as a measure of tourism’s relative importance, it becomes evident that some tourism-intensive countries are benefiting from climate action ‘tailwinds’ whereas others are suffering from ‘headwinds’. Countries in the top-right quadrant of with sizable tourism industries that operate in a favourable mitigation environment face the best conditions for tourism decarbonisation. Sectoral climate action and wider government policy in well-established destinations such as Austria, Portugal, New Zealand and Singapore should be mutually reinforcing.

Figure 2. Grouping of countries according to their Mitigation Context Index and the relative importance of travel and tourism to national employment. The axes cross at the variables’ average, respectively.

In contrast, tourism stakeholders in countries where tourism plays a major role but the mitigation context is not enabling might find decarbonisation challenging. Thailand, the Philippines, Cape Verde and Malta, for example, will have to play a leadership role to nudge the country towards greater climate action. For example, Ministries of Tourism can introduce incentives for the accommodation sector to increase the uptake of solar panels (e.g. import tax breaks, installation support, see Hotel Energy Solutions, Citation2011), or they can drive the change towards electric vehicle transport systems by establishing links between the tourism industry and transport agencies (Digital Tourism Think Tank, Citation2024). Colombia presents a useful example of tourism stakeholders actively working with other parts of government to advance tourism decarbonisation and nature conservation (OECD, Citation2022).

Thirdly, the quadrant to the top left shows countries where tourism is not a major sector, but it operates in a favourable mitigaiton envionment. Here, further tourism growth could ‘leap frog’ high carbon models and instead invest into new infrastructure and systems that meet net zero goals. China, Rwanda and the Slovak Republic are emerging destinations, where green tourism investment could play a key role, wheras other countries in this quadrant (e.g. Scandinavian countries) may continue to deliver smaller scale (relative to the economy) tourism without intentions for the sector to become dominant, either economically or in terms of leading the climate action agenda. The bottom left quadrant is characterised by low levels of tourism and an unfavourable mitigation context; it is unlikely that tourism will play a role in improving wider climate action.

Discussion

This research introduces the construct of ‘mitigation context’ to inform tourism decarbonisation. The underlying premise is that rapid progress on climate action requires engagement from both state and non-state actors (Bernstein & Hoffmann, Citation2018). Initiatives such as the Glasgow Declaration (One Planet, Citation2021) are indicative of the global tourism sector taking ownership of the challenge, but implementation ultimately depends on the conditions in each country. Understanding the context can inform sectoral strategies and policies and the role that tourism could play within national economies.

The Mitigation Context Index is based on indicators covering public transport, clean energy, and nature conservation. Combined with tourism employment data, MCI helps identify those countries where tourism is a sizable economic contributor, and at the same time operates in a favourable decarbonisation context (e.g. Netherlands and Germany). Structural ‘tailwind’ alone, however, is no guarantee for success. Even with supporting context, for example through excellent public transport networks (e.g. Singapore or Hong Kong) or solid investment into clean energy (e.g. Denmark or Portugal), it remains important that tourism stakeholders advance their low carbon transition. Tourism ministries can encourage businesses to apply for government clean energy grants, or they may work with (local) marketing bodies to specifically promote public transport-based itineraries (e.g. NelsonTasmanNZ, Citation2022). Thus, structural drivers of decarbonisation need to be combined with individual behaviour changes to maximise impact (Brownstein et al., Citation2022).

Another group of countries has been identified where tourism is a major employment contributor but the overall mitigation environment is below average (often developing countries, see Jenkins, Citation2015). Here, tourism stakeholders have an opportunity to provide leadership in driving structural change for more effective climate mitigation (see also Becken & Loehr, Citation2022). Particularly for developing countries, there is an opportunity to work with international organisations that provide technical expertise and/or finance (e.g. decarbonisation roadmap for Indonesia, WiseSteps Consulting, Citation2023). A prominent example is the One Planet (Citation2023) ‘Transforming tourism value chains’ programme that developed specific decarbonisation roadmaps for the Dominican Republic, Mauritius, the Philippines and Saint Lucia. Green investment may only come directly from tourism, thanks to the injection of funds through the visitor economy. For example, revenue raised from natural-area tourism can be significant in ensuring adequate conservation (Balmford et al., Citation2015).

Regardless of where tourism takes place, the existential need to rapidly reduce emissions to net zero remains (Allen et al., Citation2022). The six variables introduced in this research provide a starting point, but the perspective needs to be both broadened and deepened. The broadening would have to include additional areas, for example quality of governance in each country (Hall, Citation2009), and the deepening would involve developing more specific indicators for the three identified areas. For example, a high share of protected areas itself (e.g. Venezuela, Tanzania or Australia) provides limited information on the representativeness of biodiversity covered in these areas, extent of ecosystem connectedness (Mammides et al., Citation2021), and specific links between tourism and conservation. Further, the existence of a rail network tells little about the uptake of rail travel, as opposed to more carbon intense forms of transport. Thus, one limitation of the choice of variables in this note is that they focus on positive mitigation context, but do not address ‘headwinds’, for example government investment into high-carbon airport infrastructure (TPCC, Citation2023). An extended index could form the basis of a (predictive) decarbonisation model, and this could be ground proofed with tourism stakeholders to empirically identify policy positions and strategies for different countries.

It is hoped that this research encourages future analyses of mitigation context to inform sectoral climate action and target setting that is in line with international requirements but reflective of national circumstances. The tourism sector provides a pertinent example in that it would benefit substantially from mitigation success in other sectors. Overall, however, as long as tourism depends on fossil-fuel based international transport, which has not been covered in this research note, a low carbon future may remain an aspiration (Peeters et al., Citation2019). Climate action in tourism therefore might have to go further than decomposing individual decarbonisation factors. Instead, transforming the governance of tourism (including moving from a global to a more local model) and enabling creativity, innovation and system change to happen might be necessary avenues that are not currently explored (Weaver et al., Citation2022). Less and different travel might be part of the answer (Becken, Citation2019) for genuinely long-term sustainable tourism development (Jenkins, Citation2015). Discussions about degrowth (Higgins-Desbiolles & Everingham, Citation2022) will likely become more integral as policymakers seek to harness the benefits from tourism whilst minimising carbon liability.

Conclusion

This research highlighted that sectoral tourism climate action is unlikely to occur at the same scale and speed in different countries. The context in which tourism operates is crucial, and it also shapes the relative position the sector may take in relation to wider government climate policy. Future research should extend the construct of the Mitigation Context Index to consider the addition of (i) more thematic areas relevant for tourism decarbonisation; (ii) additional variables within each of the current areas (public transport, clean energy, nature protection), (iii) inclusion of counter-productive variables to also capture mitigation barriers. Opportunities to increase synergies between national climate policy and sectorial approaches exist for tourism as well as other sectors. Irrespective of whether mitigation context is favourable or constraining for tourism in a country – climate action is an imperative and must be advanced as much and as urgently as possible.

Supplementary_Table_Mitigation_Context_Index.docx

Download MS Word (36.1 KB)Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Ting Ren for her technical assistance in producing .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susanne Becken

Susanne Becken is a Professor of Sustainable Tourism at Griffith University in Australia with a research focus on the tourism-environment nexus. Susanne is a member of the Air New Zealand Sustainability Advisory Panel, the Travalyst Independent Advisory Group and the New Zealand Government Tourism Data Leadership Group. She is an elected Fellow of the International Academy of the Study of Tourism. In 2019, she was awarded the prestigious UNWTO Ulysses Award for her contribution to tourism knowledge.

References

- Allen, M. R., Friedlingstein, P., Girardin, C. A. J., Jenkins, S., Malhi, Y., Mitchell-Larson, E., Peters, G. P., & Rajamani, L. (2022). Net zero: Science, origins, and implications. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 47(1), 849–887. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-112320-105050

- Balmford, A., Green, J. M. H., Anderson, M., Beresford, J., Huang, C., Naidoo, R., Walpole, M., & Manica, A. (2015). Walk on the wild side: Estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLOS Biology, 13(2), e1002074. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002074

- Becken, S. (2019). Decarbonising tourism: Mission impossible? Tourism Recreation Research, 44(4), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1598042

- Becken, S., & Kaur, J. (2021). Anchoring ‘tourism value’ within a regenerative tourism paradigm – a government perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1990305

- Becken, S., & Loehr, J. (2022). Tourism governance and enabling drivers for intensifying climate action. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2032099

- Becken, S., Miller, G., Lee, D. S., & Mackey, B. (2024). The scientific basis of ‘net zero emissions’ and its diverging sociopolitical representation. Science of the Total Environment, 170725.

- Bernstein, S., & Hoffmann, M. (2018). The politics of decarbonization and the catalytic impact of subnational climate experiments. Policy Sciences, 51(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9314-8

- Brownstein, M., Kelly, D., & Madva, A. (2022). Individualism, structuralism, and climate change. Environmental Communication, 16(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.1982745

- Copernicus. (2024). 2023 is the hottest year on record, with global temperatures close to the 1.5°C limit. https://climate.copernicus.eu/8opernicus-2023-hottest-year-record#:~:text=Global%20surface%20air%20temperature%20highlights%3A&text=2023%20marks%20the%20first%20time,than%202%C2%B0C%20warmer.

- Digital Tourism Think Tank. (2024). Electric cars and the tourism industry. https://www.thinkdigital.travel/opinion/electric-cars-and-the-tourism-industry.

- Gössling, S., Balas, M., Mayer, M., & Sun, Y. Y. (2023). A review of tourism and climate change mitigation: The scales, scopes, stakeholders and strategies of carbon management. Tourism Management, 95, 104681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104681

- Hall, C. M. (2009). Archetypal approaches to implementation and their implications for tourism policy. Tourism Recreation Research, 34(3), 235–245. doi:10.1080/02508281.2009.11081599

- Harichandan, S., Kar, S. K., Bansal, R., Mishra, S. K., Balathanigaimani, M. S., & Dash, M. (2022). Energy transition research: A bibliometric mapping of current findings and direction for future research. Cleaner Production Letters, 3, 100026.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Everingham, P. (2022). Degrowth in tourism: Advocacy for thriving not diminishment. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2079841

- Hotel Energy Solutions. (2011). Factors and initiatives affecting renewable energy technologies use in the hotel industry. UNWTO.

- IEA. (2021). Net zero by 2050. A roadmap for the global energy sector. Accessed 14 August 2022. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/deebef5d-0c34-4539-9d0c-10b13d840027/NetZeroby2050-AroadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector_CORR.pdf.

- Jenkins, C. L. (2015). Tourism policy and planning for developing countries: Some critical issues. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(2), 144–156. doi:10.1080/02508281.2015.1045363

- Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

- Luo, J., Zhuang, C., Liu, J., & Lai, K. H. (2023). A comprehensive assessment approach to quantify the energy and economic performance of small-scale solar homestay hotel systems. Energy and Buildings, 279, 112675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.112675

- Mammides, C., Goodale, E., Elleason, M., & Corlett, R. T. (2021). Designing an ecologically representative global network of protected areas requires coordination between countries. Environmental Research Letters, 16(12), 121001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac3534

- NelsonTasmanNZ. (2022). Zero carbon itinerary. Accessed 24 November 2023. https://www.nelsontasman.nz/visit-nelson-tasman/light-footprint-holidays/zero-carbon-itinerary/.

- OECD. (2022). OECD tourism trends and policies 2022. Accessed 20 July 2023. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/tourism/oecd-tourism-trends-and-policies-20767773.htm.

- One Planet. (2021). Glasgow declaration. Accessed 8 May 2023. https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/sustainable-tourism/glasgow-declaration.

- One Planet. (2023). Transforming tourism value chains. Accessed 24 July 2023. https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/value-chains/transforming-tourism.

- Peeters, P., Higham, J., Cohen, S., Eijgelaar, E., & Gössling, S. (2019). Desirable tourism transport futures. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1477785

- Schweitzer, V., Bach, V., Holzapfel, P. K., & Finkbeiner, M. (2023). Differences in science-based target approaches and implications for carbon emission reductions at a sectoral level in Germany. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 38, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.04.009

- Sustainable Hospitality Alliance. (2023). Pathway to net positive. Accessed 8 May 2023. https://sustainablehospitalityalliance.org/our-work/pathway/.

- Tourism Panel on Climate Change [TPCC]. (2023). Tourism and climate change stocktake 2023. https://tpcc.info/stocktake-report/.

- UN. (2023). Net zero coalition. Accessed 12 May 2023. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/net-zero-coalition.

- Weaver, D., Moyle, B. D., Casali, L., & McLennan, C. L. (2022). Pragmatic engagement with the wicked tourism problem of climate change through ‘soft’ transformative governance. Tourism Management, 93, 104573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104573

- WiseSteps Consulting. (2023). Indonesia’s tourism decarbonization roadmap. https://wisestepsconsulting.id/publication/indonesias-tourism-decarbonization-roadmap.

- World Economic Forum. (2022). Travel & tourism development index 2021. Rebuilding for a Sustainable and Resilient Future, May 2022. Accessed 21 July 2023. https://www.weforum.org/publications/travel-and-tourism-development-index-2021/.