ABSTRACT

This study examines the effect of residents’ event attendance and involvement on sense of place from the perspective of social sustainability. Specifically, this study investigates the impact of residents’ frequency of visits to and active involvement in local events on their perceived sense of place by adopting a quantitative method. The survey results show that frequent visits to local events as event attendees have a significant effect on all three dimensions of sense of place, namely place attachment, place identity and place dependence. However, involvement in local events as volunteers, organisers or co-workers was found to contribute only to place identity. This study aids in enhancing our comprehension of events as a crucial aspect of neighbourhoods that contributes to broader social sustainability of communities. The findings provide quantitative empirical evidence to key stakeholders that validate the importance of events not only as economic tools but also as integral components of the social structure within local communities. The study highlights the significance of exploring the complex association between events, places, and host communities, to better understand how events can potentially strengthen the social sustainability of local communities.

Introduction

The concept of social sustainability has gained increasing attention in event studies (Black, Citation2016; Mair & Smith, Citation2021; Pernecky & Lück, Citation2012; Smith, Citation2009; Stevenson, Citation2021). This trend reflects the growing maturity of the field and highlights the recognition of the complexity of events and their societal significance. Regarding events and sustainability, Mair and Smith (Citation2021, p. 1739) called for the examination of the potential contributions of events to sustainable development, instead of solely focusing on improving the sustainability of individual events. Similarly, Pernecky (Citation2012, p. 23) argued for ‘approaching sustainability not only critically, but seeing it in a broader context of society, and not only as a management initiative’. These calls highlight the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the role of events in social sustainability, as well as the ways in which they interact with the places and communities in which they occur.

Social sustainability is an integral part of the broader concept of sustainability, which has been evolving in the past few decades, largely through the initiatives of the United Nations. In 1987, the Brundtland Report positioned sustainability as ‘development that meets the current needs without jeopardising the capability of future generations to fulfill their own needs’ (Brundtland Commission, Citation1987, p. 43). A balance between society's economic, environmental and social needs was seen as the foundation of achieving sustainability (Walker, Citation2019).

With increasing interest from governments at different levels in utilising events for community development, understanding how events can aid in building socially sustainable communities becomes crucial in justifying government investment in such events. Specifically, the sense of place among local residents has received increasing attention from governments, as residents with a strong sense of place play a key role in building strong, socially sustainable and connected communities (Nanzer, Citation2004). Understanding the role of events in establishing a sense of place and their contribution to bolstering the social sustainability of communities gains significance, particularly in times of crises such as the recent case of the COVID-19 pandemic. Events can serve as integral tools for bringing community back together (Davies, Citation2021; Son et al., Citation2023; Takeda, Citation2022).

This study aims to investigate the effect of residents’ event attendance and involvement in local events on their sense of place toward neighbourhoods using a quantitative method. More specifically, this research examines the frequency of local event attendance and involvement in the event in relation to perceived sense of place. The frequency of visit to local events and involvement in local events are conceptualised as two separate processes in this study and both assessed in terms of whether the events facilitate social sustainability outcomes (Stevenson, Citation2021). The focus of this study is on any type of local event held in a particular council area to examine the effects of an event portfolio, rather than assessing the effect of a single local event.

Literature review

When exploring the topic of the sustainability of events, Mair and Smith (Citation2021) point out the inherent contradiction that exists between sustainability and events. Whereas events are transient occurrences that do not always entail ongoing benefits to the host community, any discussion about sustainability usually considers the holistic and long-term integration of the economic, social, and environmental dimensions. The fact that events are unique highlights the need to consider their long-term social impact, complementing the economic and environmental perspectives. Yet, conceptualising social sustainability in the context of events can be problematic and ‘messy’ (Pernecky, Citation2012, p. 20) as it involves a range of scales, lenses and perspectives that impact the interpretation of this phenomenon (ibid). Smith (Citation2009), through the lens of distinctive theoretical perspectives, discusses the multitude of both positive and negative effects of events on social sustainability. The discussion exposes the very complex effect of events on people and places (Kraff & Jernsand, Citation2023), one which is often difficult to disentangle from the broader economic and environment dimensions of sustainability.

The Western Australia Council of Social Services (Citation2002), conceptualises social sustainability as

the state where processes, systems, structures and relationships support to the capacity of current and forthcoming generations to build livable and healthy communities (p. 6). Such socially sustainable communities are characterised by diversity, equity, democracy, connectivity and a high quality of life. (p. 6)

Outcomes of events for Social sustainability

Firstly, community social capital building which includes the sense of community belonging, social bonding, social connections and social cohesion, can be forged through events (Arcodia & Whitford, Citation2007). McClinchey (Citation2021) found that the preparation of multi-ethnic festivals and experiences during festival performances fostered a sense of belonging. Stevenson (Citation2016) and Black (Citation2016) argue that local festivals contribute to enhancing the social sustainability of a community by enabling networks of connectivity and strengthening community networks. Schulenkorf et al. (Citation2011) also found that while differences in attitudes amongst stakeholders and managerial tensions could prohibit social capital building, an intercommunity sport event hosted in a divided community was found to positively contribute to social capital building. The event provided positive experiences to participants through socialising, increased trust, and opportunities for fostering networks, establishing contacts and promoting intercultural learning and development. Such opportunities for intercultural learning and development offered by events were identified as a major contributor to cultural sustainability, and therefore for social sustainability of communities (Lee & Huang, Citation2015). These events can help in breaking down prejudices and promoting social harmony through promoting other cultures and generating community acceptance of diversity.

Secondly, a stronger sense of place can be achieved through events. A sense of place is about a perception of a place (Nanzer, Citation2004). Local residents’ sense of place toward their neighbourhood frequently receives attention from the local government, measured in terms of their affiliation with the local area. The connection between social sustainability and sense of place can thus be seen through the lens of creating robust, socially sustainable, and interconnected communities (Nanzer, Citation2004). This important dimension of events which encourages the creation of better places to live has gained increasing attention as events have been increasingly used by local governments as a means of creating a sense of place. They have become integral to community development strategies and placemaking (Son et al., Citation2022), aimed at enhancing the overall ‘liveability’ of neighbourhoods (Coghlan et al., Citation2017).

In event studies, previous research examined the sense of place through the lens of enhanced community pride, place attachment and identity (Derrett, Citation2003; Duffy, Citation2000; McClinchey, Citation2017). For example, Vink and Varró (Citation2019) found that those who directly participated in running events showed an increased sense of place, in particular place attachment, through experiencing the physical and social environment of the event. In the study of ethnic festivals in Canada, McClinchey (Citation2008) claimed that festivals can contribute to a sense of place and can create strong meaning of place for community members as well as reminding visitors of positive emotions, feelings and attachments.

Although some empirical studies have asserted that events have the potential to enrich the sense of place within a community (Coghlan et al., Citation2017; Duffy, Citation2000; Mair & Duffy, Citation2018; Whitford & Ruhanen, Citation2013), many of these studies have employed a case study methodology, utilising a specific qualitative approach that predominantly examines how individual events contribute to cultivating a sense of place (Mair & Smith, Citation2021). Thus, previous studies have mainly investigated the effect of particular events to building a sense of place in a specific context, but there is limited research investigating the role of events for enhancing the sense of place among residents.

Thirdly, community equity and social justice with the goals of inclusion and access have been discussed in event studies as a social sustainability outcome. It has been argued that events can be used to provide an equitable opportunity for all community members, including the most vulnerable, for social inclusion and well-being (Mair & Duffy, Citation2015; Smith, Citation2009). For instance, multicultural festivals have the potential to enhance the social inclusion of ethnic minority groups within multicultural societies. These festivals offer a dedicated space for cultural celebrations, enabling ethnic minority communities to safeguard their cultural heritage and ensure its preservation for future generations (Lee et al., Citation2012; McClinchey, Citation2021). In that context, events can be argued to provide an important public forum for diverse members of the community to meet and interact with each other, and form a psychological sense of community (Hassanli et al., Citation2021). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community events have also been discussed as a catalysts for social change, facilitating recognition of the LGBT community and promoting wider social acceptance (Ong & Goh, Citation2018).

Lastly, community well-being and quality of life is another social sustainability topic which is increasingly discussed in event impact studies (Filep et al., Citation2015; Packer & Ballantyne, Citation2011), and a number of researchers claim that events play a role in supporting community and individual well-being. Brownett (Citation2018) looked at how community arts festivals contribute to enhancing well-being among communities and found that festivals can amplify health and well-being benefits as such events can foster active participation and support community acceptance of difference. Similarly, Wood et al. (Citation2018) argue that social interaction and creativity/artistic activities at participatory arts events can create a synergy that increases not only immediate enjoyment but also longer-lasting benefits such as inclusion, belonging, reduced loneliness and isolation for event attendees, particularly in the over 70s. Kitchen et al. (Citation2023) also found that unlike virtual event attendance, the frequency of face-to-face event attendance has a positive influence on fostering feeling of social connectedness which can contribute to both individual and community social well-being.

Although these four social sustainability outcomes of events are evident in previous studies, many of these studies (Hassanli et al., Citation2021; Lee & Huang, Citation2015; Schulenkorf et al., Citation2011) adopted a qualitative method to understand how individual events play a role in achieving social sustainability of communities. Only a few studies (Gibson et al., Citation2014; Wood & Thomas, Citation2006) used a quantitative method to test the relationship between social sustainability outcomes and events, and their findings were sometimes different to those of the qualitative studies. For example, Gibson et al. (Citation2014) assessed residents’ perceived psychic income and social capital before and after the FIFA 2010 World Cup, and their quantitative study suggests that while psychic income increased, the dimensions of social capital either decreased or showed no change. Wood and Thomas (Citation2006) also conducted a quantitative study to investigate the influence of a cultural festival on local civic pride. Their findings revealed a minimal impact of the festival on civic pride. This discrepancy between the quantitative and qualitative results regarding the contribution of events to social sustainability of communities, along with the lack of generalisable and conclusive findings from any studies, highlight the need for additional research that can provide a more generalisable and broader understanding of the role of events in social sustainability of communities.

The past research (Mair & Duffy, Citation2015; McClinchey, Citation2008; Ong & Goh, Citation2018; Wood & Thomas, Citation2006) also mainly used a case study approach focusing on one particular event and its contributions, and this might explain the discrepancies in findings mentioned above. Getz (Citation2005) and Ziakas (Citation2010) point out the importance of adopting a holistic approach for planning and managing events and evaluating event outcomes. They argue for the adoption of an event portfolio approach which could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the impacts, moving beyond evaluating the influence of a single local event to a broader perspective on the collective effects of multiple events within a community.

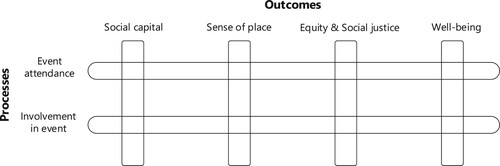

Processes of events for Social sustainability

In addition to the four main social sustainability outcomes of events, the previous literature identifies two processes which events facilitate to achieve social sustainability outcomes (Stevenson, Citation2021): (1) social interaction; and (2) community participation. As Stevenson (Citation2021) points out, events possess the potential to generate occasions for social interaction and active community participation, factors that are closely linked to the advancement of social sustainability within communities. Based on the contact theory (Allport, Citation1954), previous studies argue that social interaction and encounters enable people to establish significant connections (Askins, Citation2016) and enhance their relationship with diverse groups by developing better understanding of one another (Lee et al., Citation2012; Stevenson, Citation2021). This arguably can contribute to social sustainability of communities through improving inclusion and interconnectedness.

Event studies, for instance Lee and Huang’s (Citation2015) study on multicultural festivals, claim that individuals attending festivals are presented with valuable opportunities to acquire knowledge about diverse cultures, engage with various cultural groups, and develop a deeper comprehension of different cultures and the concept of multiculturalism in general. Furthermore, the authors noted that while this understanding may be temporary in nature, it can serve as an initial step towards fostering acceptance of other cultures and nurturing the values of multiculturalism. Stevenson (Citation2019) also argues that community events, such as a street party, present fresh opportunities for neighbours from diverse backgrounds to come together, and facilitate pleasurable and friendly interactions. As such, the effect of social interactions that event visitors have at events on the social sustainability of communities has been explored in previous event studies (Lee & Huang, Citation2015; Stevenson, Citation2019). However, these studies mainly used qualitative methods with findings which are difficult to generalise to wider contexts. Moreover, the impact of the frequency of visits to local events on the development of social sustainability outcomes has not been investigated.

As participatory process is identified as one of the five features of social sustainability, participating in community initiatives has been considered important for developing social sustainability within neighbourhoods (Partridge, Citation2014). Previous event studies have also emphasised the significance of community involvement in events for attaining improved and sustainable event outcomes, including social sustainability. For example, McClinchey's studies (Citation2017, Citation2021) on multicultural festivals found that the involvement of performers in the preparation stage of events in particular, allows them to develop and experience a sense of pride, identity and belonging. Similarly, Son et al. (Citation2022) claim that organising events with active involvement from community members offers a valuable opportunity to foster community engagement and cultivate networks of relationships. This, in turn, helps build social capital and a sense of place, and create better placemaking outcomes. While these studies have revealed the significance of community involvement and active participation in events as a process for social sustainability, the understanding of their effect on social sustainability outcomes is limited. For instance, it is unclear whether involvement in events is essential to achieve social sustainability outcomes or if attending events and engaging in social interactions alone can make a significant contribution to social sustainability, considering that attending events would be the more common activity for most residents.

Sense of place

Among other social sustainability outcomes of events, this study focuses on residents’ sense of place, and aims to examine the effect of residents’ event attendance and involvement in local events, which are the two processes by which events facilitate social sustainability, on their sense of place.

While previous studies show a positive impact of events on a community's sense of place, as discussed above (Derrett, Citation2003; Duffy, Citation2000; McClinchey, Citation2008, Citation2017), Smith (Citation2009, p. 113) exposes a more negative effect of staging major events on the community and perceived sense of place. Events may spatially and socially alter the community due to urban development and regeneration. Similarly, Misener and Mason (Citation2006) argue that host communities are often left struggling to find meaning and sense of place, particularly place identity, in neighbourhoods which hosted major events. Smith (Citation2009) also questions whether events in fact deliver social sustainability, particularly to those who may not have the means to attend or those that are not interested in them. These studies highlight the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the role of events in enhancing residents’ sense of place, particularly with an event portfolio approach which includes small and major events and various types of events.

The notion of sense of place pertains to the way in which individuals establish a connection with and experience their living environments (Nanzer, Citation2004, p. 363). The concept of sense of place includes various interconnected dimensions (Jin et al., Citation2023; Jorgensen & Stedman, Citation2006) leading to a lack of consensus on the structure of these dimensions and their measurements, particularly due to their somewhat abstract nature (Qian & Zhu, Citation2014). For instance, Ispas et al. (Citation2021) delineate place identity and place dependence as two sub-dimensions under the construct of place attachment, while Deutsch et al. (Citation2013) introduce two additional constructs – place satisfaction and place physical/aesthetic surroundings. These ideas stretch the three common constructs regularly discussed of place identity, place attachment and place dependence to explore the significance of physical, cultural and social attributes in shaping a sense of place.

The challenge in establishing a widely accepted structure for these dimensions indicates that intricate internal dynamics are shaped by specific social conditions and research contexts. Each dimension operates in diverse relationships with others, contingent on varying contextual constellations and social connections (Gibson et al., Citation2014; Qian & Zhu, Citation2014). However, many discussions on sense of place are focused mainly on the constructs of place attachment, place identity, and place dependence (Deutsch et al., Citation2013; Jin et al., Citation2023; Jorgensen & Stedman, Citation2006; Nanzer, Citation2004; Qian & Zhu, Citation2014): (1) place attachment, which reflects a bond that exists between the place and the residents; (2) place identity, which is about the meaning and significance of the place to the residents; and (3) place dependence, which refers to the degree to which a place fulfills the functional needs of its residents. Based on these dimensions of sense of place, six hypotheses were generated to investigate the influences of the two processes of events for social sustainability, (1) the involvement in any local events as a volunteer, organiser or performer and (2) the number of visits to any local events as an event attendee, on sense of place.

H1: Involvement in local events is a significant predictor of place attachment.

H2: Involvement in local events is a significant predictor of place identity.

H3: Involvement in local events is a significant predictor of place dependence.

H4: Number of visits to local events is a significant predictor of place attachment.

H5: Number of visits to local events is a significant predictor of place identity.

H6: Number of visits to local events is a significant predictor of place dependence.

This study also examined the potential impact of other variables that may be associated with a sense of place and introduces an endogeneity issue. Factors such as length of residence and home ownership were included as control variables, considering their influence on place attachment, identity and dependence as indicated by previous studies (Lalli, Citation1992; Nanzer, Citation2004; L. Wood et al., Citation2010).

Methodology

This study used a quantitative approach to develop a broad understanding of the relationship between local events and residents’ sense of place. City of Holdfast Bay, situated in South Australia (SA), Australia, is considered SA's favourite coastal destination, attracting numerous events and event attendees. The area has been chosen as a focus of the study because of its well-developed event scene and the strategic commitment of the council to promoting events. Hosting more than 300 events each year within the council area provides the residents with multiple opportunities to become involved in events, which was an important consideration when selecting the location for the study. Furthermore, the City of Holdfast Bay has a well-established positive destination image which is associated with a diverse range of events, spanning local to international events and from sports to community events. In 2019 the council was home to roughly 356,000 residents.

The survey contained three main sections. The first section asked about respondents’ involvement in events and social interactions. Social interaction experienced at events was measured with a question asking about the frequency of visits to any type of local events in the last three years pre-COVID-19, given that social interaction can be made and facilitated at events through event attendance and experience. Previous involvement in events was assessed with a question that queried whether they have been involved in a local event in various capacities: event volunteer, event participant (i.e. exhibitor, performer), event organiser or other role in the last three years, or they had not been involved beyond attending as an attendee. The chosen time frame attempted to capture the pre-COVID community involvement in local events.

In the second section, sense of place was measured through three dimensions, (1) place attachment; (2) place identity; and (3) place dependence, drawn from Nanzer (Citation2004), but revised to align with the study's context following consultations with the council. The items were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The last section of the survey asked demographic questions covering age, gender, household type, occupation, length of residence within the council area, and home ownership (own or rent/other). A pilot test involving 140 residents from a different city was carried out to ensure the reliability and validity of the measurement, which were confirmed.

Before data collection began, ethics committee approval was obtained through the university. A questionnaire was administered to residents in this council between October and November 2020 and distributed in multiple ways. The survey was distributed to 3000 households within the city council via mailbox drops. A prepaid envelope was provided to return the completed questionnaire. The online survey link was also made accessible through the council's official social media platform. Additionally, printed copies of the questionnaire, along with prepaid return envelopes, were made available at two local libraries.

The data underwent analysis utilising the SPSS 25.0 software. To establish factor groups related to the sense of place, factor analysis was conducted using the Principal Component Analysis technique with a Varimax rotation method. Standard multiple regression analyses were performed to evaluate the significance of previous involvement in local events and the frequency of visits to local events as predictors of place attachment, place identity, and place dependence. Additionally, hierarchical multiple regressions were carried out to assess the predictive capacity of the model, which includes previous involvement in local events and the number of visits to local events, to predict place attachment, place identity and place dependence, taking into account various additional variables (length of residency and home ownership in the council area). Given that this study focuses on one level of relationship between event involvement and sense of place, and the number of visits to events and sense of place, multiple regressions were deemed more suitable than utilising Structural Equation Modelling.

Results

A total of 397 valid questionnaires were collected; 24 online survey responses and 373 hard copy surveys returned. provides the respondent profiles. More than half of the respondents were from the age group of 60 and over. While this is certainly a high percentage for this age group, it is believed that the sample represents the population of the city given that the number of people in their 60s and 70s is twice the number of people in their 20s or 30s. Also, there is an increasing number of older residents (between 65 and 74 years old) in the City of Holdfast Bay (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017). More broadly, many developed nations are currently experiencing aging of their societies, and the survey results reflect this process. While the obtained sample does over-represent older residents, it also offers important insights about this specific demographic and their perception of events, which can inform the understanding of events and their role in many similar locations.

Table 1. The profile of respondents.

Nearly a third (32.0%) of the respondents attended local events six to ten times in the three years between 2017 and 2019, and 28.8% attended local events 1–5 times. Only 6.6% of the respondents did not attend any local events in the three years. Only 17.2% of the respondents had been involved in local events as an event volunteer, event participant (i.e. exhibitor, performer) or event organiser, whereas the majority (82.8%) had not been involved in a local event within the three years. All those who had been involved in these roles at events also attended events in the three years. For data analysis, respondents who indicated involvement in any of the aforementioned roles were classified as ‘involved in events’ (coded as 1), while those who only attended events without any other involvement were coded as 2.

An exploratory factor analysis was performed to identify an appropriate factor structure – item communalities above .40, item loading above .30 without cross-loadings (Costello & Osborne, Citation2019). During this process, one item, ‘I like living close to the coast’, was removed due to cross-loading, displaying higher loadings than .32 on two factors (Costello & Osborne, Citation2019). presents the outcomes of the final factor structure, displaying mean scores of items for three factor groups for sense of place, generated through Principal Component Analysis using a Varimax rotation method. These factors were labelled as ‘place dependence’, ‘place attachment’, and ‘place identity’. The three factors explained 54.20%, 14.11%, and 10.00% of the variance respectively. Together, these three factor groupings explained 78.31% of the variance. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity confirmed the suitability of the nine items for factor analysis (KMO: .827; Bartlett's test, p < .000). Additionally, Cronbach's alpha was employed to assess the reliability of the three factors. The reliability of factors 1, 2 and 3 were .844, .884 and .735 respectively, indicating satisfactory levels (Pallant, Citation2011).

Table 2. Principal Component Analysis of sense of place.

A series of standard regression analyses were conducted to examine the impact of previous involvement in local events and number of visits to local events on place dependence, place identity and place attachment. Each independent variable demonstrated tolerance values exceeding .10, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) values remained below the threshold of 10.0, as recommended by Pallant (Citation2011), confirming that the multi-collinearity assumption was not violated.

The multiple regression tests results displayed in show that number of visits to local events was a significant predictor for all dependent variables, place dependence (β = .213, R2 = .051, F (2, 352) = 9.474, p < .0005), place attachment (β = .167, R2 = .031, F (2, 353) = 5.573, p < .005), and place identity (β = .146, R2 = .043, F (2, 351) = 7.804, p < .0005), whereas involvement in local events was found to be a significant factor only on place identity (β = -.130, R2 = .043, F (2, 351) = 7.804, p < .0005). That is, local residents who attend local events more frequently are more likely to have a stronger place dependence, attachment and identity towards the City. Also, those who have been involved in local events as an event volunteer, event participant (i.e. exhibitor, performer) or event organiser are more likely to have a stronger identity than those who have not been involved in local events. The results also indicate that number of visits to local events (β = .146) had a greater influence on place identity than involvement in local events (β = -.130). The negative β value of involvement in local events was obtained as involvement in local events was coded as yes = 1 and no = 2.

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis.

Moreover, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were carried out to evaluate the predictive capacity of two control measures (previous involvement in local events, and number of visits to local events) to predict levels of place dependence, attachment and identity, after controlling for the influence of the length of residency and home ownership. presents the results of the hierarchical multiple regression analyses with dummy variables for the length of residency in the City (over 15 years of residency in the City = 1, less than 15 years = 0), and home ownership (own = 1, rent or other = 0). Over 15 years of residency (n = 175) for the dummy variable of the length of residency and owning (n = 314) for the dummy variable of home ownership were chosen as the reference category based on the largest number of respondents in each group among the alternatives.

Table 4. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis.

In Model 1, length of residency and home ownership were included for each dependent variable, and subsequently, in Model 2, the introduction of previous involvement in local events and the number of visits to local events were evaluated by comparing total variance. The hierarchical multiple regression analyses () revealed that even when considering other variables such as length of residency and home ownership, the frequency of attending local events remained a significant predictor for place dependence (β = .221, R2 change = .070, F change (4, 337) = 9.922, p < .05), place attachment (β = .186, R2 change = .047, F change (4, 338) = 6.717, p < .05), and place identity (β = .173, R2 change = .050, F change (4, 336) = 9.000, p < .05). Involvement in local events (β = -.124, p < .05) was found to still have a significant effect on place identity after controlling for the influence of other variables. The results also indicate that number of visits to local events (β = .186, p < .05) had a greater influence on place attachment than other variables such as length of residency (β = .114, p < .05) and home ownership (β = .126, p < .05). The analysis revealed that neither length of residency nor home ownership were identified as significant factors affecting place dependence and place identity. Based on these results, hypotheses 1 and 3 were not supported by the data, but hypotheses 2, 4, 5, and 6 were supported.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, the impact of attending local events and participating in community activities on residents’ sense of place were investigated. The study findings indicate that local events serve as a valuable means of fostering stronger connections between residents and their neighbourhoods, ultimately enhancing the sense of place within the community. This effect holds true regardless of the duration of residency or home ownership status. Specifically, this study revealed a notable correlation between the frequency of attending local events and all three dimensions of sense of place. This means that residents who participated in local events more frequently exhibited a heightened sense of place. This implies that individuals who attended a higher number of local events were more prone to experiencing satisfaction with their neighbourhood, demonstrate a greater inclination to reside in the area for an extended period, and feel a stronger connection to the place. Moreover, they were more inclined to perceive their residential area as an ideal location for engaging in activities they enjoy, offering diverse opportunities to partake in their favoured pursuits. This finding appears to confirm previous qualitative research (Derrett, Citation2003; Duffy, Citation2000; Vink & Varró, Citation2019) which claims that events can develop a sense of place in a community. The quantitative data obtained in this study confirms the relationship between local events and the development of a sense of place.

It is also interesting to note that event attendance was found to have a greater effect on sense of place, particularly on place attachment, than the effect of the two control variables, length of residency and home ownership, which are well recognised in previous studies as influential variables to sense of place (Lalli, Citation1992; Nanzer, Citation2004; Wood et al., Citation2010). Particularly, this finding demonstrates the effectiveness of local events as a tool for enhancing residents’ sense of place towards their neighbourhood.

On the contrary to event attendance, involvement in local events as volunteers, organisers or co-workers (i.e. exhibitor, performer) was found to be significantly associated with only one sense of place dimension, place identity. It means that residents who have been involved in local events were more inclined to possess a stronger place identity than those who have not been involved in events. However, their level of place dependence or place attachment may not necessarily be stronger. That is, residents who have been involved in local events are more likely to feel their neighbourhood is important to them and feel connected to the area. These results indicate that while getting involved in local events is helpful in strengthening a sense of place by enhancing a sense of place identity, having more frequent visits to local events as event attendees is more effective at increasing residents’ sense of place.

This finding contradicts certain assertions made by previous studies on events which found that involvement in events rather than as an event visitor can develop a deep sense of place (McClinchey, Citation2017, Citation2021). This could be because of the level of interactions that the event participants have with other participants in pre- or post-event stages which was not captured in this study. McClinchey’s (Citation2017, Citation2021) studies explore how sense of place evolves by examining the opportunities provided by events for event participants (e.g. event co-workers) to interact with others in a meaningful way in the pre-event stage. Future research on the effect of the level of interactions in pre- or post-event stages on sense of place could provide other perspectives to better understand this aspect.

The findings from this study hold valuable practical implications for leveraging local events for community development. As the findings show that local event attendance is effective for enhancing a sense of place in the community, events can be particularly useful for loosely connected communities or newly developed communities to build a strong, socially sustainable and connected community. For example, this finding can be particularly meaningful for multicultural societies such as in Australia where events can provide an important means of engaging all residents including those more established as well as newcomers who may seek stronger connections with the new place (Hassanli et al., Citation2021; McClinchey, Citation2021) regardless of the length of residency and home ownership. Also, the investment in events by governments, which is usually justified by its economic impacts, can be justified with the social outcomes demonstrated by this study.

This study contributes to the current understanding of the social impacts of events by focusing on how local events influence residents’ sense of place. Notably, it expands upon prior research by offering empirical quantitative evidence that highlights the effectiveness of local events in fostering a stronger sense of place within the community. By conceptualising the process and outcomes of events for social sustainability and comparing event attendance and involvement in events as the process of events for social sustainability outcomes, this study offers a more comprehensive understanding of the role of events in fostering social sustainability within communities to advance the current state of knowledge in the field. Further research could centre on examining the influence of events on the remaining outcomes related to social sustainability; namely, social capital, equity & social justice, and well-being of the host community.

Although this study offers various practical and theoretical contributions, it is not without its limitations. Firstly, the sample size within the older age group may impact the representativeness of the findings. While this may align with the population distribution within this council as discussed in the methodology section, this limitation is acknowledged. However, the data obtained from the sample can be seen as valuable to understanding the perceptions of this important and growing demographic. As the aging of developed societies accelerates, it will become even more important to understand, through further research, the role events can play in connecting older citizens to their place and other community members. Secondly, this study adopts an event portfolio approach to examine the aggregate role played by various size and type of events in a community in relation to sense of place. However, mega events were not included in the study as they were not held in the research area during the research timeframe. Mega events may have different effects on residents’ sense of place (Smith, Citation2009; Misener & Mason, Citation2006). Future research endeavours could investigate and compare the effect of small community events and international mega events on residents’ sense of place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Insun Sunny Son

Insun Sunny Son is Senior Lecturer in Event and Tourism Management at UniSA Business, University of South Australia in Adelaide, Australia. She holds a PhD from the University of Queensland, Australia. Her research interests focus on event management and strategic use of events for destination development, community development, placemaking, well-being, and public diplomacy.

Chris Krolikowski

Chris Krolikowski is a Lecturer in Tourism, Hospitality & Event Management at the University of South Australia and an expert in the field of urban tourist. His research interests include the impact of tourism, events, and culture on placemaking and sustainability of urban destinations, including the phenomenon of ‘overtourism'. In his teaching, he applies cutting edge digital tools to foster students’ engagement and effective learning.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Arcodia, C., & Whitford, M. (2007). Festival attendance and the development of social capital. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 8(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J452v08n02_01

- Askins, K. (2016). Emotional citizenry: Everyday geographies of befriending, belonging and intercultural encounter. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(4), 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12135

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017). 2016 census QuickStats. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA42600.

- Black, N. (2016). Festival connections: How consistent and innovative connections enable small-scale rural festivals to contribute to socially sustainable communities. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 7(3), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-04-2016-0026

- Brownett, T. (2018). Social capital and participation: The role of community arts festivals for generating well-being. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 9(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah.9.1.71_1

- Brundtland Commission. (1987). Our common future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf.

- Coghlan, A., Sparks, B., Liu, W., & Winlaw, M. (2017). Reconnecting with place through events. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 8(1), 66–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-06-2016-0042

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2019). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

- Davies, K. (2021). Festivals post Covid-19. Leisure Sciences, 43(1–2), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774000

- Derrett, R. (2003). Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a communitys sense of place. Event Management, 8(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599503108751694

- Deutsch, K., Yoon, S. Y., & Goulias, K. (2013). Modeling travel behavior and sense of place using a structural equation model. Journal of Transport Geography, 28, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.12.001

- Duffy, M. (2000). Lines of drift: Festival participation and performing - A sense of place. Popular Music, 19(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143000000027

- Filep, S., Volic, I., & Lee, I. S. (2015). On positive psychology of events. Event Management, 19(4), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599515X14465748512687

- Getz, D. (2005). Event management and event tourism (2nd ed.). Cognizant Communication Corporation.

- Gibson, H. J., Walker, M., Thapa, B., Kaplanidou, K., Geldenhuys, S., & Coetzee, W. (2014). Psychic income and social capital among host nation residents: A pre–post analysis of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. Tourism Management, 44(0), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.013

- Hassanli, N., Walters, T., & Williamson, J. (2021). ‘You feel you're not alone': How multicultural festivals foster social sustainability through multiple psychological sense of community. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11-12), 1792–1809. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1797756

- Ispas, A., Untaru, E.-N., Candrea, A.-N., & Han, H. (2021). Impact of place identity and place dependence on satisfaction and loyalty toward black sea coastal destinations: The role of visitation frequency. Coastal Management, 49(3), 250–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2021.1899914

- Jin, W., Yoon, H., & Lee, S. (2023). A model of leisure involvement, residential satisfaction, and place attachment in passive older migrants. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 64(1), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12356

- Jorgensen, B. S., & Stedman, R. C. (2006). A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: Attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. Journal of Environmental Management, 79(3), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.08.003

- Kitchen, E., Son, I. S., & Jones, J. J. (2023). Can events impact on social connectedness and loneliness? An analysis of face-to-face and virtual events attended in South Australia. Event Management, 27(7), 1011–1024. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599523X16896548396734

- Kraff, H., & Jernsand, E. M. (2023). Multicultural food events – Opportunities for intercultural exchange and risks of stereotypification. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(6), 844–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2126922

- Lalli, M. (1992). Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement, and empirical findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(4), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80078-7

- Lee, I., Arcodia, C., & Lee, T. J. (2012). Benefits of visiting a multicultural festival: The case of South Korea. Tourism Management, 33(2), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.04.001

- Lee, I. S., & Huang, S. (2015). Understanding motivations and benefits of attending a multicultural festival. Tourism Analysis, 20(2), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354215X14265319207470

- Mair, J., Chien, P. M., Kelly, S. J., & Derrington, S. (2023). Social impacts of mega-events: A systematic narrative review and research agenda. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 538–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1870989

- Mair, J., & Duffy, M. (2015). Community events and social justice in urban growth areas. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(3), 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.997438

- Mair, J., & Duffy, M. (2018). The role of festivals in strengthening social capital in rural communities. Event Management, 22(6), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599518X15346132863229

- Mair, J., & Smith, A. (2021). Events and sustainability: Why making events more sustainable is not enough. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11–12), 1739–1755. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1942480

- McClinchey, K. A. (2008). Urban ethnic festivals, neighbourhoods, and the multiple realities of marketing place. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400802508309

- McClinchey, K. A. (2017). Social sustainability and a sense of place: Harnessing the emotional and sensuous experiences of urban multicultural leisure festivals. Leisure/Loisir, 41(3), 391–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2017.1366278

- McClinchey, K. A. (2021). Contributions to social sustainability through the sensuous multiculturalism and everyday place-making of multi-ethnic festivals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11-12), 2025–2043. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1853760

- McKenzie, S. (2004). Social sustainability: Towards some definitions. Hawke Research Institute Working Paper Series No 27. University of South Australia. Magill, SA. https://www.unisa.edu.au/siteassets/episerver-6-files/documents/eass/hri/working-papers/wp27.pdf.

- Misener, L., & Mason, D. S. (2006). Creating community networks: Can sporting events offer meaningful sources of social capital? Managing Leisure, 11(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606710500445676

- Nanzer, B. (2004). Measuring sense of place: A Scale for Michigan. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 26(3), 362–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2004.11029457

- Ong, F., & Goh, S. (2018). Pink is the new gray: Events as agents of social change. Event Management, 22(6), 965–979. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599518X15346132863292

- Packer, J., & Ballantyne, J. (2011). The impact of music festival attendance on young people's psychological and social well-being. Psychology of Music, 39(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735610372611

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual (4th ed). Allen & Unwin.

- Partridge, E. (2014). Social sustainability. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 6178–6186). Springer.

- Pernecky, T. (2012). Events, society, and sustainability: Five propositions. In T. Pernecky, & M. Lück (Eds.), Events, society and sustainability: Critical and contemporary approaches (pp. 15–29). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Pernecky, T., & Lück, M. (2012). Events, society and sustainability: Critical and contemporary approaches. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Qian, J., & Zhu, H. (2014). Chinese urban migrants’ sense of place: Emotional attachment, identity formation, and place dependence in the city and community of Guangzhou. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 55(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12039

- Schulenkorf, N., Thomson, A., & Schlenker, K. (2011). Intercommunity sport events: Vehicles and catalysts for social capital in divided societies. Event Management, 15(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599511X13082349958316

- Smith, A. (2009). Theorising the relationship between major sport events and social sustainability. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 14(2–3), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080902965033

- Son, I. S., Krolikowski, C., & Fleming, E. (2023). Intention to attend local events in the time of COVID-19: The case of Australia. Event Management, 27(5), 729–743. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599523X16817925582104

- Son, I. S., Krolikowski, C., Rentschler, R., & Huang, S. (2022). Utilizing events for placemaking of precincts and main streets: Current state and critical success factors. Event Management, 26(2), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599521X16106577965044

- Stevenson, N. (2016). Local festivals, social capital and sustainable destination development: Experiences in East London. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(7), 990–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1128943

- Stevenson, N. (2019). The street party: Pleasurable community practices and placemaking. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 10(3), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-02-2019-0014

- Stevenson, N. (2021). The contribution of community events to social sustainability in local neighbourhoods. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11-12), 1776–1791. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1808664

- Takeda, S. (2022). Continuation of festivals and community resilience during COVID-19: The case of Nagahama Hikiyama Festival in Shiga Prefecture. Japanese Journal of Sociology, 31(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijjs.12132

- Vink, R., & Varró, K. (2019). Running Rotterdam: On how locals’ participation in running events fosters their sense of place. GeoJournal, 86(2), 963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-10104-3

- Walker, T. B. (2019). Sustainable tourism and the role of festivals in the Caribbean – Case of the St. Lucia Jazz (& Arts) Festival. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(2), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1602314

- Western Australia Council of Social Services. (2002). Submission to the state sustainability strategy consultation paper. http://st1.asflib.net/MEDIA/ASF-CD/ASF-M-00173/submissions/WACOSS.pdf.

- Whitford, M., & Ruhanen, L. (2013). Indigenous festivals and community development: A sociocultural analysis of an Australian indigenous festival. Event Management, 17(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599513X13623342048149

- Wood, E. H., Jepson, A., & Stadler, R. (2018). Understanding the well-being potential of participatory arts events for the over 70s: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Event Management, 22(6), 1083–1101. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599518X15346132863283

- Wood, E. H., & Thomas, R. (2006). Measuring cultural values: The case of residents’ attitudes at the Saltaire Festival. Tourism Economics, 12(1), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000006776387187

- Wood, L., Frank, L. D., & Giles-Corti, B. (2010). Sense of community and its relationship with walking and neighborhood design. Social Science & Medicine, 70(9), 1381–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.021

- Ziakas, V. (2010). Understanding an event portfolio: The uncovering of interrelationships, synergies, and leveraging opportunities. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 2(2), 144–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2010.482274